Lake Nipissing fisheries management plan: valuing a diverse fishery

A management plan for the sustainable management of Lake Nipissing’s fisheries and lake ecosystem, including strategies to protect, preserve and recover the walleye population.

Titles and approval

Encompassing a portion of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Administrative District of North Bay.

I certify that this plan has been prepared using the best available science and is consistent with accepted fisheries management principles. I further certify that this plan is consistent with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s strategic direction, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s Statement of Environmental Values and direction from other sources. Thus, I recommend this fisheries management plan be approved for implementation.

Recommended and original signed by

Mitch Baldwin, District Manager, North Bay District

Date: August 21, 2014

Approved and original signed by:

Corrinne Nelson, Regional Director, Northeast Region

Date: September 9, 2014

Executive summary

Fisheries management planning is a key component of the Ecological Framework for Fisheries Management (EFFM) in Ontario. The EFFM is an operational framework that provides the building blocks for improving the way recreational fisheries are managed in Ontario. Fisheries Management Planning is consistent with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s (MNRF) current strategic directions outlined in Our Sustainable Future (OSF) and the goals and objectives of the Ontario Biodiversity Strategy (OBS). It is also aligned with the fisheries policy principles stated in the Strategic Plan for Ontario Fisheries (SPOF II).

The Fisheries Management Plan (FMP) is designed to highlight the value of the diversity of the lake and to be flexible and adaptable to a wide range of future conditions. The planning process considered the lake in a holistic manner and included a range of management options to ensure a healthy lake environment, conserve the diversity of the fish community and provide opportunities to contribute to the social and economic well-being of the surrounding area.

The final FMP is intended to be a dynamic document that may be amended as circumstances require. An adaptive management approach will be taken with periodic internal review (5 year review periods) to evaluate the progress towards targets and continued appropriateness of plan objectives. Management actions including fishing regulation changes may be required throughout plan implementation to ensure the sustainability of Lake Nipissing’s fisheries.

Purpose and scope

The Lake Nipissing FMP has been developed by the MNRF with input and advice from the Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Advisory Council (LNFMPAC) along with input received from the broader public at key stages of the plan development process. The planning area lies within the geographic boundaries of Lake Nipissing, a Specially Designated Water (SDW) within the broader Fisheries Management Zone (FMZ 11). The Lake Nipissing FMP will be integrated into the broader FMZ 11 management plan.

Lake Nipissing supports a diverse fish community and offers a wide variety of angling opportunities (e.g. walleye, yellow perch, northern pike, bass, muskellunge, lake herring (cisco) and lake whitefish). The Lake Nipissing recreational fishery is an important economic and social engine within FMZ 11 contributing to a significant local tourism industry. The lake also provides aboriginal subsistence and commercial fisheries that are primarily focused on walleye, but also on whitefish and northern pike.

Goals and objectives are identified herein that address challenges as well as identify opportunities associated with the management of Lake Nipissing’s fisheries. The plan identifies actions to assist MNRF in balancing the demands for the use of the resource with the biological capacity of the lake. This balance is based on an analysis of fisheries data and collaborative discussions with members of the public, stakeholders, First Nations and aboriginal communities, and local governments.

The plan focuses on enhancing, promoting and maintaining open communication between government, stakeholders and First Nations by providing a framework for the cooperative management of the fishery. The goals of the plan are to:

- Recognize and understand the natural capacities of Lake Nipissing and to develop and sustain a diverse fishery within those limits within an adaptive management framework.

- Move towards an ecosystem-based approach which recognizes values and manages all components of the lake’s fishery and ecosystem.

- Enhance Lake Nipissing as a desirable fishing destination.

- Manage the lake sustainably to provide social, cultural, recreational and economic benefits while respecting Aboriginal and Treaty rights.

- Proactively share all information on the fishery leading to informed use and recognition of its value.

- Increase public understanding of fisheries information to achieve a positive state of stewardship and advocacy for the resource.

- Actively develop/establish partnerships with stakeholders to leverage other resources to achieve plan objectives.

The Lake Nipissing FMP moves towards an ecosystem-based approach that emphasizes the importance of several components of a healthy lake and addresses the significant sustainability issues facing the fishery (i.e. decline in the walleye population) while promoting the diverse angling opportunities the lake has to offer. The MNRF plans to actively develop/establish partnerships with First Nations and stakeholders to leverage other resources to achieve plan objectives via a series of strategies that reflect management priorities within the lake. Each strategy identifies the management challenges or opportunities and associated objectives and management actions. Specifically, these strategies include:

Recreational fishery management strategies

- Walleye Management

- Northern Pike Management

- Yellow Perch Management

- Smallmouth and Largemouth Bass Management

- Muskellunge Management

- Lake Herring Management

- Lake Whitefish Management

Management strategies for ecosystem health

- Water quality and quantity

- Water quality

- Water levels

- Fish habitat

- Biological changes

- Fish community

- Species at risk

- Invasive species

- Cormorants

- Fish disease

- Climate Change

Other management strategies

- Enforcement

- Commercial Ice Huts

Recreational fishery management strategies

Walleye management

Key highlights include the implementation of a new minimum size limit that allows anglers to harvest fish 46 cm in length or greater, while maintaining the current catch limit of two fish for sport licence holders and one fish for conservation licence holders. The regulation is intended to provide increased protection for the remaining strong year classes of juvenile walleye, enabling them to reach spawning age and contribute to restoring the population; to increase the abundance of spawning females, to increase the overall abundance and biomass of walleye, and to promote a low risk and short-term recovery period for walleye in the lake.

The plan identifies opportunities to improve collaboration with First Nations to better understand the demand for walleye by their communities for food, cultural, spiritual and commercial purposes. The plan also identifies opportunities to continue collaborative research efforts and expand the scope of studies to enhance existing information. It will increase public awareness of walleye biology and the limitations of some management tools (e.g. stocking within the current Lake Nipissing context).

The new regulation for walleye was implemented on May 17, 2014.

Northern Pike management

Recent studies indicate the northern pike population is showing signs of stress with a decline in the overall abundance of northern pike in the lake. A more thorough data review of the pike population dynamics and status in the lake is required in order to properly inform future management actions for the species. The pike regulation for the lake will remain unchanged until this data review is complete.

Yellow Perch management

Highlights of the yellow perch strategy include doubling the daily catch limit to promote increased harvest. Daily catch and possession limits for sport licence holders have changed from 25 fish per day to 50 fish per day. This is an attempt to decrease abundance of yellow perch to historical levels while taking a cautionary approach. This may also facilitate the recovery of walleye in the lake by reducing potential competition for resources from perch and to re-stabilize the fish community.

The new regulation for yellow perch was implemented on January 1, 2014.

Smallmouth and Largemouth Bass management

Key highlights include the implementation of a new bass regulation that promotes angling for bass focussing on their sporting qualities and providing additional angling opportunities by opening the season one week earlier than in previous years.

The new regulation for bass was implemented on June 21, 2014.

Muskellunge management

The muskellunge fishery on the lake is primarily a trophy fishery that is sustainable at this time. The existing regulations are being carried forward under this plan.

Lake Herring and Whitefish management

There is currently very little demand for these species by the recreational fishery. As such, they have both received very limited management effort to date. Although the whitefish population appears to be relatively stable, there is evidence that the herring population is declining in the lake. At this time, the plan maintains existing regulations for both species with the intention of enhancing assessment efforts to acquire a better understanding of the status of these populations.

Fishing regulations for all recreational sportfish species may be adjusted throughout plan implementation based on relevant and updated science and management objectives.

| Species | Current Regulation | New Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Yellow Perch (Implementation date: January 1, 2014) | Season: January 1 to March 15 Catch / Possession Limits:

| Season: January 1 - March 15 Catch / Possession Limits:

|

| Walleye (Implementation date: Open water season opener: May 17, 2014) | Season: January 1 to March 15 Catch Limits:

Size Limit: None between 40 to 60 cm (15.7 to 23.6 inches) | Season: January 1 to March 15 Catch Limits:

Size Limit: None less than 46 cm (18 inches) |

| Smallmouth and Largemouth Bass (Implementation date: Season opener: June 21, 2014) | Season: 4th Saturday in June to November 30 Catch Limits:

| Season: 3rd Saturday in June to November 30 Catch Limits:

|

Management strategies for ecosystem health

Ecosystems are naturally complex. Key characteristics of healthy integrated ecosystems include structural elements (e.g. species composition, native biodiversity and a variety of habitats) and functional processes (e.g. energy flow, material transport and hydrological processes). A healthy aquatic ecosystem operates within a range of natural variation providing a benchmark for understanding and measuring ecosystem health. This informs planning decisions by describing the current state of the ecosystem.

Each characteristic was considered along with input on other environmental, social and economic requirements when the management strategies for a healthy Lake Nipissing ecosystem were developed. The plan identifies management strategies within three broad categories of impacts that can affect the Lake Nipissing ecosystem, including water quality and quantity, biological changes, and climate change.

Water quality and quantity management

Water quality and quantity in aquatic ecosystems strongly influence lake productivity, biodiversity and structural elements (e.g. fish habitat). A number of water quality, lake level and fish habitat indicators have been identified to be assessed and monitored over time. Collaborating with key partners on the collection and assessment of these indicators will aid resource managers in determining whether changes in water quality will alter fish populations, whether current water level operations are providing for the needs of fish and whether a variety of habitat types are being maintained.

Biological change management

Aquatic ecosystem monitoring generally involves measuring and observing indicators of biological change. These indicators can provide information on changing climates, water quality and quantity and respond to changing patterns of fish resource use. For Lake Nipissing, the biological indicators selected were fish community, including species at risk and invasive species, cormorants and fish disease. Key management actions include assessment and monitoring to improve our understanding of fish community dynamics, anticipate and mitigate impacts from cormorants and prevent the expansion of fish diseases.

Climate change management

Ontario’s climate is warming and becoming increasingly variable. Projected climate change impacts could include higher water temperatures, fluctuating ice on and off dates, changes in lake productivity and creation of favourable or less favourable conditions for species. A key management action for climate change is to conduct a vulnerability assessment on the watershed to assist in identifying adaptation needs, developing adaptation strategies, developing or expanding on existing monitoring programs and understanding if vulnerabilities have increased, decreased, or been eliminated.

Other management strategies

Enforcement

Enforcement is important to ensure successful implementation of management actions intended to safeguard the public interest. Key highlights include actions to annually review enforcement issues in order to establish annual enforcement priorities for the lake, continuing to collaborate with First Nations to build enforcement capacity and helping to educate users on plan management strategies.

Commercial ice huts

Commercial ice huts are now commonplace on the lake with 90 per cent offering overnight accommodation. Growing concern from the public over the impact of overnight ice huts led to the creation of a commercial ice hut licence. A review of winter angler surveys indicates that very few walleye are caught overnight and it has not measurably increased overall angling effort. The plan proposes to continue to implement the commercial ice hut program as per the status quo.

1.0 Introduction

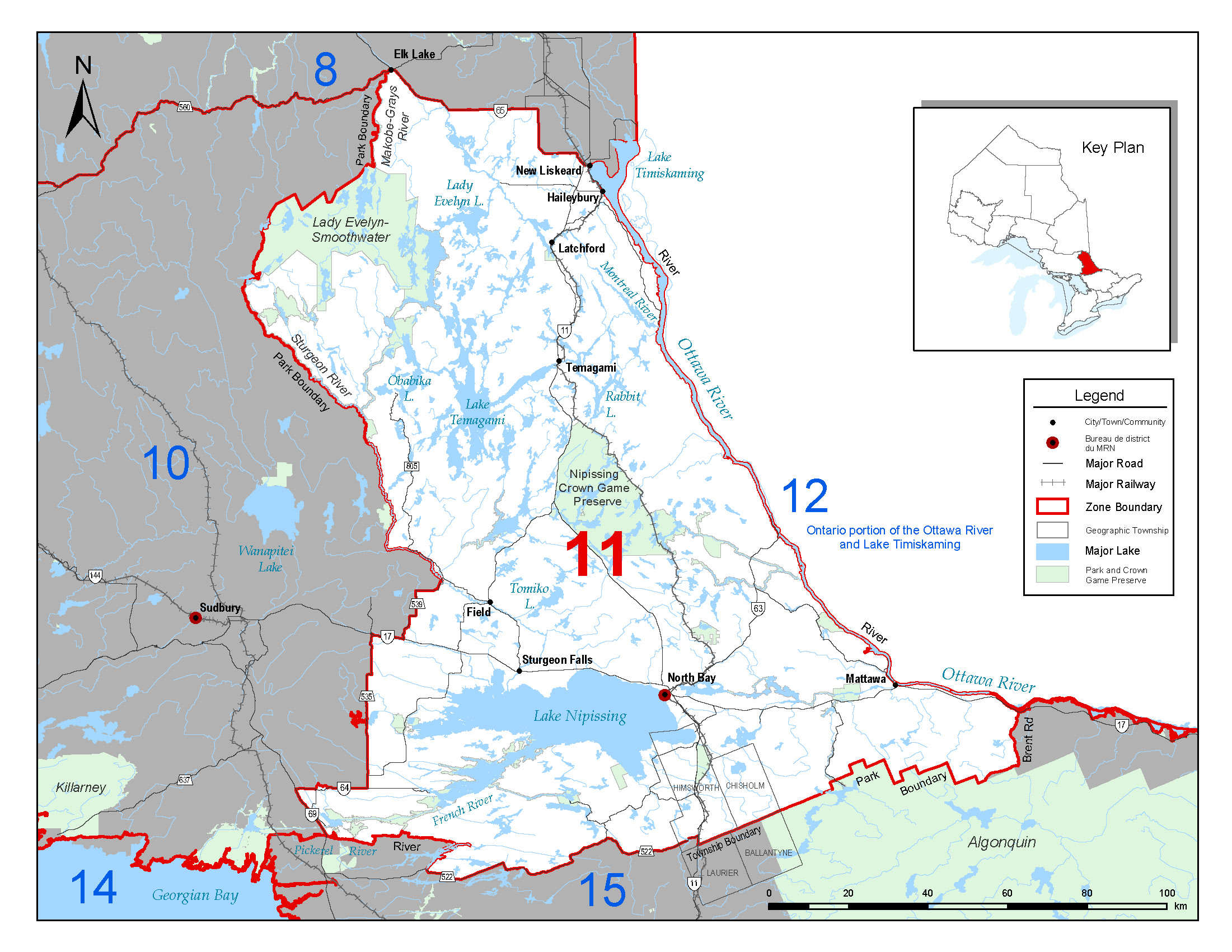

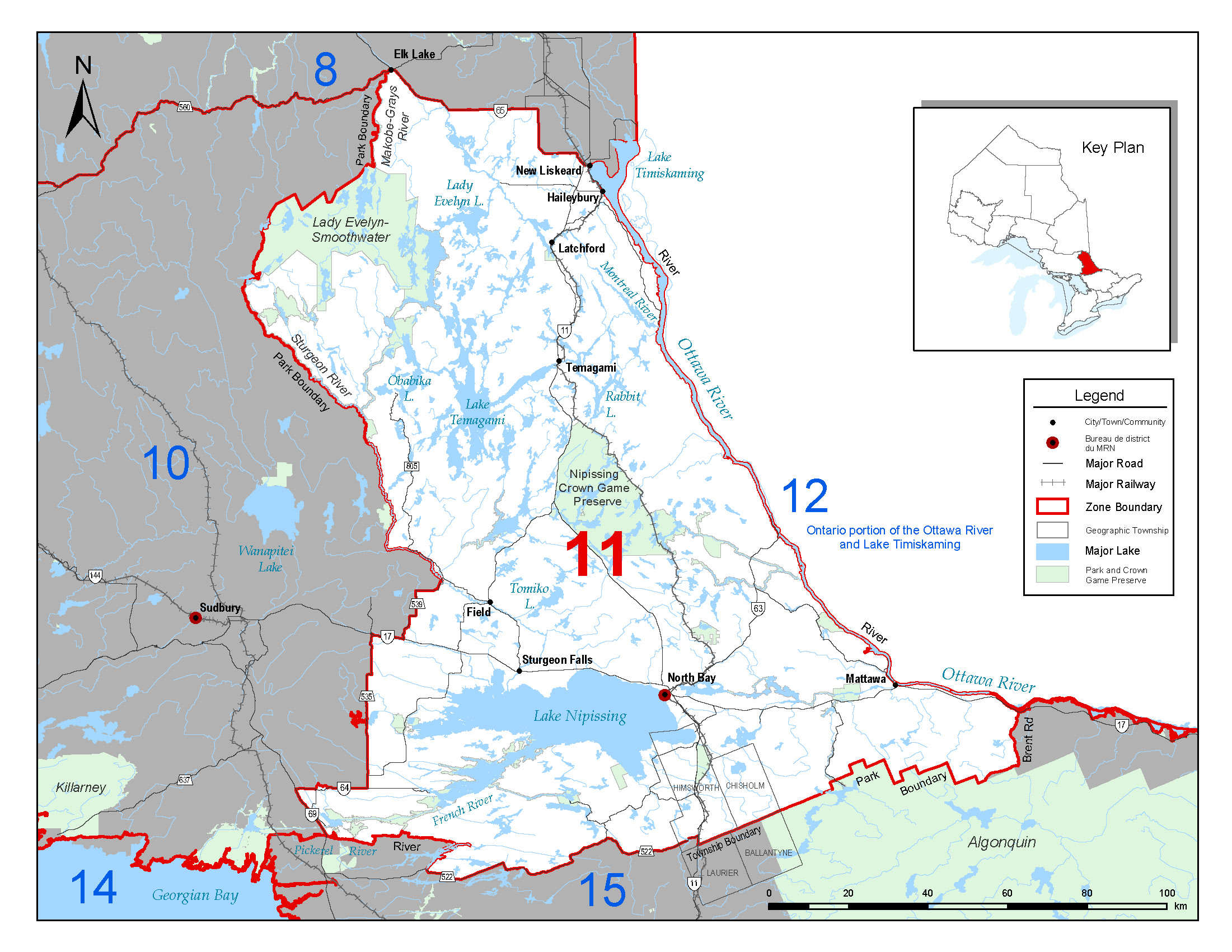

At 87,325 hectares, Lake Nipissing is the largest lake in FMZ 11 (Figure 1) and the fifth largest inland lake wholly within the province of Ontario. Despite its size, Lake Nipissing was referred to by early Natives as ‘N’bisiing’ or ‘little water’ because of the size of this lake in comparison to the Great Lakes. In Algonquin, (the linguistic group of the Ojibwe), ‘N’bisiing’ comes from ‘Nbi’ meaning ‘water’ and ‘siing’ meaning ‘little’ (Norm Dokis, MNRF, personal communication).

Lake Nipissing is surrounded by a population of approximately 75,000, including the larger municipalities of North Bay, West Nipissing and Callander, in addition to two First Nation communities; Nipissing No. 10 and Dokis No. 9. It is accessed from the south via Highway 69 & 11, from the north via Highway 11, and from the east and west via Hwy 17 (Figure 2). It is currently the seventh most fished lake (including the Great Lakes) in the province with the fisheries being an important economic and social engine within FMZ 11 and the local communities. A detailed economic evaluation associated with the present day fishery is required.

The fisheries also provide cultural, social and economic benefits to both the Nipissing First Nation (NFN) and Dokis First Nation (DFN). Both First Nations rely on the lake for subsistence fishing, while NFN also has a court-recognized treaty right to commercially fish the lake. Currently, NFN undertakes the commercial fisheries on Lake Nipissing (i.e. walleye, whitefish and northern pike) and provides statistical information to MNRF; while MNRF manages the recreational fisheries. The focus of this plan is to address the recreational fisheries management strategies; this plan does not directly address commercial fisheries management strategies. It will, however, incorporate strategies or actions where the two fisheries overlap and it will highlight key areas of collaboration and cooperation between the First Nations and MNRF.

Background

Lake Nipissing is classified as a Specially Designated Water (SDW) within Fisheries Management Zone 11. SDW’s are designated to recognize the importance of specific water bodies to the broader region or Province of Ontario. These waters may have unique challenges requiring more intensive monitoring and planning separate from that of the broader FMZ.

Lake Nipissing’s fisheries have a long history of human use, beginning with First Nation’s historical use of the lake for subsistence fishing and later for commercial purposes which continues today. In addition to subsistence and commercial fishing use by the local First Nations, the lake has also supported a recreational fishery since at least the early 1900s.

The fish community in the lake is dominated by walleye (Sander vitreus), yellow perch (Perca flavescens), northern pike (Esox lucius), and white sucker (Catostomus commersoni), with a significant coregonid component consisting of lake herring (cisco; Coregonus artedi) and lake whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis). Other significant species include smallmouth bass (Micropterus dolomieu), largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) and lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens). A total of 42 fish species have been documented in Lake Nipissing (Appendix 1). The lake sturgeon (Acipenser fulvescens; threatened) and the silver lamprey (Ichthyomyzon unicuspis) (special concern) both of Great Lakes-Upper St. Lawrence populations are the two fish species at risk in the lake. Rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax), common carp (Cyprinus carpio), and black crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus) are introduced species. This plan identified specific objectives and strategies regarding the management of walleye, northern pike, yellow perch, bass, muskie, whitefish and herring, however it is expected that non-species specific strategies including those identified for water quality, quantity, habitat and others will be beneficial for the sustainability of the broader aquatic community.

The fisheries management plan for Lake Nipissing considers a broader management approach emphasizing the importance of all components of the fishery and managing them appropriately, rather than focussing solely on walleye. Ecosystem-based fishery management aims to conserve the structure and function of aquatic ecosystems in addition to conserving the fishery resources. It moves away from single species, static population management strategies and recognizes and governs under the principle that diversity is important to ecosystem function and resilience.

The purpose of the planning process is to develop management strategies and objectives with specific targets and timelines that will assist with and guide the management of the recreational fisheries for the lake. This was done by compiling and analysing relevant data, reviewing the best available science, referencing provincial policies, management guidelines and direction, as well as gathering input from multiple stakeholders and First Nations with a particular interest or concern with Lake Nipissing (Appendix 2).

2.0 Strategic direction and guiding principles

As stewards of Ontario’s fisheries resources MNRF governs the strategic direction and guidance documents that are intended to support the fisheries management planning process. This management plan seeks to incorporate strategic direction and guiding principles specific to the needs of Lake Nipissing’s fisheries.

2.1 Overview of fisheries management in Ontario

Fisheries Management falls within the direct mandates of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (federal) and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (provincial). In some instances other governments or agencies are also involved (e.g. local First Nations and conservation authorities). The mandate for fisheries management prescribed by federal legislation falls under the Fisheries Act (FA) and the Species at Risk Act (SARA), and provincial legislation falls under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act (FWCA) and the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

The MNRF also has authority for fisheries management under a number of provincial statutes including: the Natural Resources Act (NRA); Crown Forest Sustainability Act (CFSA); Public Lands Act (PLA); Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act (LRIA); and the Environmental Assessment Act (EA Act). All of these contain provisions for the protection and perpetuation of the province’s fisheries resources.

The MNRF and all other Ontario Ministries must comply with federal legislation to protect fish and fish habitat in all integrated resource management and planning activities (e.g. forestry, waterpower, renewable energy, municipal planning, resource stewardship and development projects, and transportation facilities).

As the lead planning agency for fisheries management in Ontario, the MNRF is responsible for policy, planning and program development; the allocation of sport, commercial, tourist and baitfish fisheries via regulations and licensing; fish culture and stocking programs; species at risk and invasive species management.

MNRF also considers the potential impacts of climate change on fisheries resources and how fisheries management activities need to adapt to these potential changes when deliberating on the sustainable distribution and use of these resources.

2.2 Strategic direction

The MNRF’s mission (from the Statement of Environmental Values) is to manage Ontario’s natural resources in an ecologically sustainable way to ensure that they are available for the enjoyment and use of future generations. The MNRF is committed to the conservation of biodiversity and the use of natural resources in a sustainable manner.

At the provincial level, four documents provide strategic direction for managing fisheries resources in Ontario:

- Our Sustainable Future: A Renewed Call to Action (PDF)

- Government Response to Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy (PDF)

- The Strategic Plan for Ontario Fisheries (SPOF II)

- MNRF's Statement of Environmental Values

Historically, District Fisheries Management Plans (DFMPs) were developed by the MNRF to guide fisheries management in the late 1980’s, but these have since expired. As part of MNRF's Ecological Framework for Fisheries Management (EFFM) (OMNR 2005), new Fisheries Management Zones (FMZs) are now the main spatial unit for planning and management of fisheries in Ontario. This framework outlines the process for the MNRF, in consultation with FMZ Advisory Councils, to define objectives and strategies for the management of fisheries in each FMZ.

In Ontario there are currently 22 water bodies or groups of waters, including Lake Nipissing, with significant biological, social and economic local, regional or provincial value that are identified as Specially Designated Waters

. These bodies of water may require a more intensive management approach. Lake Nipissing has a long history of being managed individually, including being managed previously as its own fishing division. The lake has been managed in the past under the direction of two lake-specific management plans (1999 – 2003; 2007 – 2010) and will continue to be managed individually under the direction contained herein.

Although Lake Nipissing is being managed as an individual waterbody, the broader landscape scale was considered during the planning process. While management planning decisions were made specifically for Lake Nipissing, the effect of these management actions on adjacent fisheries management zones (FMZ 10, 11 and 15) were also considered, including the implications on adjacent SDW’s (French River and Lake Temagami). It is estimated that Lake Nipissing accounts for over a third of all angling effort directed at walleye in FMZ 11 (OMNR 2010a and b). Displacement of effort from Lake Nipissing would likely result in a significant impact to surrounding waters both within and outside of the zone. Management actions, particularly those related to walleye have considered the potential impacts of diverting fishing pressure elsewhere across the landscape.

2.3 Provincial guiding principles

The following principles of ecology and conduct will be used to guide fisheries management planning and decision making, and are considered fundamental in achieving the desired future state of the fisheries resource in Lake Nipissing. They are derived from broader MNRF strategic direction such as Our Sustainable Future: A Renewed Call to Action (OMNR 2011b), the Ontario Biodiversity Strategy (OMNR 2011a), and MNRF’s Statement of Environmental Values.

Ecological principles

- Ecosystem approach

- Fisheries will be managed using a holistic approach where all ecosystem components including humans and their interactions will be considered at appropriate scales.

- Natural capacity

- There is a limit to the natural capacity of aquatic ecosystems and hence the benefits that can be derived from them.

- Naturally reproducing fish communities

- Self-sustaining fish communities based on naturally occurring fish populations will be the priority for management. Where introduced or invasive fish species have become naturalized, and where consistent with management objectives, they will be managed as part of the fish community.

- Protect, restore, rehabilitate

- Fisheries management will place a priority on protecting fish, fisheries and supporting ecosystems and will restore or rehabilitate degraded systems (habitat) when necessary.

- Fish and aquatic ecosystems are valued

- Fisheries, fish communities, and their supporting ecosystems provide important ecological, social, cultural, and economic services that will be considered when making resource management decisions.

Principles of conduct

- Aboriginal and treaty rights

- Aboriginal rights and interests in fisheries resources will be recognized and considered in MNRF’s plans and activities. MNRF is committed to meeting any existing and future legal obligations in respect of Aboriginal peoples.

- Informed decision making

- Resource management decisions will be made using the best available science and knowledge. The sharing of scientific, technical, cultural, and traditional knowledge will be fostered to support the management of fish, fisheries and their supporting ecosystems.

- Collaboration

- While the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry has a clear mandate for the management of fisheries in Ontario, successful delivery of this mandate requires collaboration with other responsible management agencies and those who have a shared interest in the stewardship of natural resources.

2.4 FMZ 11 guiding principles

The following broad objectives were developed by the FMZ 11 Advisory Council and were considered where appropriate during the development of this plan:

- Fish populations:

- Manage for the improvement of fisheries, including healthy natural fish populations beyond a minimally sustainable condition, enhance urban angling opportunities and provide a safe food source while employing the precautionary principle.

- Aquatic ecosystems:

- Maintain healthy aquatic ecosystems and restore impacted aquatic ecosystems by affecting positive change to habitat and water quality while minimizing the risk of invasive/invader species.

- Education:

- Improve public knowledge of regulatory principles, respect for the resource and awareness of ethical practices around aquatic ecosystems.

- Socio-economic:

- Promote a fair valuation of the fisheries resource to recognize its impact on socio-economic benefits and provide a varied experience for all resource users.

2.5 Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Advisory Council (LNFMPAC) guiding principles

The following broad objectives were developed by the LNFMPAC and were considered where appropriate during the development of this plan:

- Ecological approach

- An ecological approach to fisheries management will be followed to ensure conservation and use of the resource in a sustainable manner.

- Landscape level management

- In general, fisheries are managed at a landscape scale. Lake Nipissing, however, is a major component of the fishery resources within FMZ 11 and it has its own unique use patterns and consequential effects, partly rooted in the history of resource development. It is understood that there may be major differences in the resource or objectives between Lake Nipissing and the broader FMZ which may require different approaches to management within the Zone.

- Balanced resource management

- Strategies and actions will consider the ecological, economic, social and cultural benefits and costs to society, both present and future.

- Sustainable development

- The finite capacity of the resource is recognized in planning strategies and actions for the lake. Only natural resources over and above those essential to long-term sustainability are available for use and development. Only those which exceed the requirements of subsistence fishing are available for other uses such as commercial fishing, recreational fishing or tourism development.

- Biodiversity

- Fisheries management will ensure the conservation of biodiversity by committing to healthy ecosystems, protecting and preferring native, natural fish populations and sustaining their genetic diversity. All of the lake’s species, including non-sport fish and Species-at-Risk, must be considered.

- Natural reproduction

- Priority will be placed on native, naturally reproducing fish populations that provide predictable and sustainable benefits with minimal long-term cost to society.

- Habitat protection

- The natural productive capacity of the habitats of fish and of the organisms upon which fish depend will be protected and habitat will be enhanced where possible.

- Valuing the resource

- Stakeholders and other users will be invited to understand and appreciate the value of fisheries resources and to participate in decisions to be made by MNRF that may directly or indirectly affect the lake’s aquatic ecosystem health.

- Responsibility

- Effective fish management is a cooperative venture with responsibility being shared by local, regional, provincial and federal governments, by First Nations and by citizens generally. Through cooperation and the sharing of knowledge, solutions to challenges will be sought so fisheries can attain and remain at levels from which all parties can derive a sustainable level of benefits.

- Multi-party Involvement

- A wide range of stakeholders, Aboriginal peoples, and interested parties will provide fisheries management advice to ensure an open and transparent process that acknowledges their valuable role in the process.

- Aboriginal interests

- Ontario is committed to building better relationships with Aboriginal peoples and in involving them in decisions that affect them. It is the responsibility of the government to ensure that the subsistence needs of Aboriginal peoples are met, within the constraints of a sustainable resource base.

- Direct action

- Before acting upon the resource, the broadest possible constellation of options will be considered and the feasibility of implementing actions will be carefully evaluated. It is expected that our actions may have to evolve as situations change and our knowledge improves.

- Knowledge

- The best available information will be used when objective setting, in strategy development and in implementation. Monitoring and assessment needs and the sufficiency thereof will be re-evaluated as knowledge improves.

- Adaptive management

- Lake Nipissing will be managed using an adaptive management approach. Objectives will be set, actions implemented and monitoring will occur so that results can be continually compared against objectives. In this way, our management can be adjusted as necessary and as possible to ensure attainment of objectives.

- Precautionary principle

- When an activity raises threats to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. Every effort will be made to ensure our systems are robust and fault-tolerant. We should expect that the future is inherently unpredictable and, thus, be cautious in our manipulations of the natural system.

3.0 Plan development and consultation process

3.1 Plan development process

The purpose of the planning process is to gather all relevant pieces of information related to the resource and to develop a document that clearly identifies the management objectives and strategies. These must identify specific targets and timelines that will assist with and guide the management of the recreational fisheries in an open and transparent way that solicits input from the general public and stakeholders. The end result will be a plan that is comprehensive, provides clear direction with measureable and achievable goals that support the long term sustainability of the fisheries in the lake.

Once the plan has been completed and approved, monitoring and reporting as per the management strategies will be completed. The plan will be reviewed periodically (e.g. in 5 year intervals) to track the progress against predicted targets and to allow resource managers to adapt and take action as needed to address emerging management issues on the lake, and to ensure plan objectives are met.

Amendments to the plan can occur when a significant management issue is identified requiring immediate action. This would include any considerable deviation from the strategic direction or management actions outlined in the approved plan. Public consultation may or may not be required for amendments depending on the significance of the change to the original strategic direction or management actions. The nature and scope of consultation efforts will be determined by the MNRF District Manager at that time. Changes to management actions such as fishing regulation changes may be considered and undertaken at any time during plan implementation in the event of threats to the sustainability of Lake Nipissing’s fisheries.

The planning process was comprised of several key stages (Figure 3).

Figure 3: fisheries management plan development process

- 1.0 Invitation to Participate: MNRF Requests Stakeholder Participation on Advisory Council and Commences Advisory Council Deliberations

MNRF sent invitations to stakeholders and advisors requesting their participation on the Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Advisory Council (LNFMPAC)

MNRF formed Council and commenced deliberations on the fisheries management plan seeking input from LNFMPAC- 2.0 Public Invitation to Participate: Notice of Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Development and Status of the Resource Report (First Nations Meetings and Public Open Houses)

MNRF met with interested local First Nations and invited public to participate in open houses. MNRF provided an update on the status of the fishery and sought input on components of the Fisheries Management Plan- 3.0 Development of Draft Fisheries Management Plan

MNRF compiled a draft plan using strategic direction, best available science, resource assessment data and input from LNFMPAC, First Nations and the public.- 4.0 Invitation to Participate: Draft Plan Review and Environmental Registry Posting

MNRF invited public participation in the draft plan review

MNRF ER Proposal posting for draft plan review sought public input (30 day review and comment period)- 5.0 Development of Final Plan

MNRF completed final plan based on input from LNFMPAC, First Nations and the public.- 6.0 Plan Approval and Implementation

Final plan approved and is implemented- 7.0 Public Notice of Final Plan : Final Plan (Plan Approval and Implementation)

MNRF ER Decision Notice providing the opportunity for public viewing of the final plan.- 8.0 Plan Reviews and Revisions

MNRF carries out plan reviews, in order to assess achievement of objectives and management strategies and respond accordingly.

- 8.0 Plan Reviews and Revisions

- 7.0 Public Notice of Final Plan : Final Plan (Plan Approval and Implementation)

- 6.0 Plan Approval and Implementation

- 5.0 Development of Final Plan

- 4.0 Invitation to Participate: Draft Plan Review and Environmental Registry Posting

- 3.0 Development of Draft Fisheries Management Plan

- 2.0 Public Invitation to Participate: Notice of Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Development and Status of the Resource Report (First Nations Meetings and Public Open Houses)

Proposed management objectives and strategies process:

As indicated above, the LNFMPAC, a group of a wide variety of stakeholders, was the initial point of contact for the MNRF to seek stakeholder input into the development of the plan and to commence drafting the objectives and management strategies for the plan. Plan development was based on the current status of the resource, known management issues, challenges and opportunities on the lake.

Once the proposed management objectives were identified, MNRF staff with input from the LNFMPAC developed specific indicators, benchmarks, targets, timelines, and management actions that supported achievement of the objectives for each species or topic in the plan (Figure 4). These can be found in the summary table for each species or topic in the appendices. Appendix 3 provides the definitions that were used in the development of the indicators, benchmarks, targets, timelines, and management actions.

Figure 4: management objective and management strategy development process

- Description of Fishery

Status of the Resource

Management Issues, Challenges, Opportunities

Desired Fishery- Management objectives

- Indicators

Benchmarks

Targets

Timelines- Management actions

- Monitoring strategies

- Management actions

- Indicators

- Management objectives

3.2 Public consultation process

Under the Ecological Framework for Fisheries Management, public input is one of the key pillars of the planning process. Public involvement in fisheries management on Lake Nipissing has had historical significance and grounding in the provincial fisheries management direction utilized today in the province.

There are various ways in which public consultation is incorporated into the plan. The LNFMPAC was intended to represent the public at large as well as to be the initial point of contact for the MNRF to seek stakeholder input. Stakeholder input is important in the development of the objectives and management strategies for the plan and to be presented to the broader public for review and input.

After each stage of public consultation MNRF compiled and reviewed the comments received and where appropriate, changes were made to the plan (Figure 5).

The following section highlights how the LNFMPAC, First Nations, and the public were consulted during the development of the Fisheries Management Plan. Appendices 4 and 5 provide a summary of consultation comments received to date.

The following illustrates the key stages of the broader public consultation process:

Figure 5: fisheries management planning consultation process

- Formation of Advisory Council and Commencement of deliberations of plan

- MNRF Compiles data and input from LNFMPAC deliberations

- Invitation to Participate: Notification of Plan Start and Request for Public Input*

- MNRF compiles Draft Plan with best available science, input from LNFMPAC, First Nations and the public

- Invitation to Participate: Notification of Draft Plan, Seeking Public Review and Input (ER Posting – 30 day review and comment period)*

- MNRF compiles, reviews, and considers comments and modifies Final Plan accordingly based on second round of public consultation

- Decision Notice: Notification of Inspection of Final Plan (ER posting – 45 day period)*

- MNRF compiles, reviews, and considers comments and modifies Final Plan accordingly based on second round of public consultation

- Invitation to Participate: Notification of Draft Plan, Seeking Public Review and Input (ER Posting – 30 day review and comment period)*

- MNRF compiles Draft Plan with best available science, input from LNFMPAC, First Nations and the public

- Invitation to Participate: Notification of Plan Start and Request for Public Input*

- MNRF Compiles data and input from LNFMPAC deliberations

* Indicates public actions.

3.3 Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Advisory Council (LNFMPAC)

The core membership of the LNFMPAC is the result of an Advisory Committee established in the summer of 2012, brought together to advise MNRF on the socio-economic impacts of regulation changes being proposed to address concerns with the walleye population. With the decision to proceed towards drafting the fisheries management plan, MNRF enhanced the group’s membership to include other relevant stakeholders or organizations that had known or expressed concerns or interests in the lake.

The current advisory council is a standing committee consisting of 10-15 volunteers representing a broad array of stakeholder groups, advisors and representatives from other governmental agencies that have a shared interest in the management of Lake Nipissing including: Nipissing First Nation, Dokis First Nation, FMZ 11 Advisory Council, tourist operators, anglers-at-large, fish and game clubs, Lake Nipissing Partners in Conservation, Greater Nipissing Stewardship Council, Nature and Outdoor Tourism Outfitters (NOTO), North Bay Hunters and Anglers, local municipalities along with the Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport, Ministry of Northern Development and Mines, and the North Bay Mattawa Conservation Authority. A complete list of those that chose to participate on the council can be found in Appendix 2.

The purpose of the LNFMPAC is to provide advice to the MNRF to assist with the development of the management objectives and strategies for the lake’s fisheries. A Terms of Reference (TOR) was developed to describe the purpose, principles, organizational details, roles, responsibilities and operating costs for the Council that can be found in Appendix 2.

3.4 Aboriginal community involvement

Within the geographic scope of the FMP, the following Aboriginal communities were identified by MNRF and were consulted as follows:

- MNRF consulted directly with the Nipissing First Nation community.

- MNRF consulted directly with the Dokis First Nation community.

- MNRF notified Antoine Algonquins and Mattawa-North Bay through the Algonquin Consultation Coordination Office (Algonquin Nation of Ontario). MNRF notified North Bay Métis Council directly with information copied to the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) as per the Ontario interim direction on Métis consultation direction at key stages of plan development and plan implementation.

- Other Robinson-Huron Treaty First Nations were notified through the Anishinabek Nation (Union of Ontario Indians (UOI)) and not each individual First Nation community for key stages of plan development and plan implementation.

The Lake Nipissing fisheries provide cultural, social and economic benefits to both the NFN and DFN. The MNRF recognizes the Aboriginal and Treaty right of both Dokis and Nipissing First Nation’s to fish Lake Nipissing for sustenance. In addition, R. v. Commanda 1990 has recognized Nipissing First Nation’s right to commercially fish Lake Nipissing.

Over the duration of the previous management plan, MNRF and NFN have collaborated on a number of assessment projects, including the lake sturgeon tagging program, the 2012 Fall Walleye Index Netting (FWIN), the 2013 Creel survey as well as the development of the Lake Nipissing Walleye Management Risk Assessment Model. This model was designed to help fisheries resource managers set safe annual harvest levels for both the commercial and recreational fisheries.

MNRF intends to continue collaborative efforts with First Nations on resource monitoring and allocation planning in a proactive, flexible management framework that balances the subsistence, commercial and recreational demand for fisheries resources on the lake. A collaborative approach will foster an understanding and respect between the fisheries resource managers and their objectives. In addition to this, open, transparent data collection and sharing among parties will contribute to an overall understanding of use patterns and aid in management solutions for the betterment of the fisheries and the lake ecosystem as a whole.

In recognizing the importance of aligning the recreational and commercial fisheries and collaborating with allocation planning, First Nations involvement was strongly encouraged and sought at all stages of development of the plan. Letters requesting participation to local First Nation partners were initially sent inviting their participation on the LNFMPAC which resulted in three members involved on the Advisory Council as council members; two Nipissing First Nation members and one Dokis First Nation member.

Aboriginal perspectives were incorporated into the plan via both Nipissing First Nation and Dokis First Nation involvement on the Advisory Council and through other discussions.

Appendix 4 provides a summary of Aboriginal Consultation during the planning process.

3.5 Broader public involvement

Reaching a broader public audience is an important part of the planning process. It assures the MNRF that input received from the LNFMPAC reflects that of the broader public opinion; it informs the advice from the LNFMPAC; provides the MNRF the opportunity to communicate the proposed management strategies to the broader public and seek input; and allows MNRF to communicate the rationale for the proposed management strategies which facilitates public understanding and participation.

Comments received on the draft plan were considered and incorporated into the final plan where appropriate (Appendix 5).

There were several stages during the plan development process that sought broader public input into the development of the plan including:

Public invitation to participate: notice of Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan development and status of the resource report

An invitation to participate was released in May 2013 via a series of news releases and open houses that were held to present the background information on the FMP, a status of the resource report for the lake and to seek input from the broader public on the key topics to be included in the plan. These comments were reviewed and considered during the development of the draft plan.

Public invitation to participate: draft plan review and comment period (Environmental Registry Posting – 30 day comment period closed April 24, 2014)

This stage of consultation provided the public with an opportunity to review the proposed plan and provide comments on the proposed direction therein.

The draft plan was made available at the district office, on the MNRF website for Specially Designated Waters - Lake Nipissing, and on the Environmental Registry for public review.

Public notice of final plan approval (ER Posting – 45 days)

The final plan was made available at the North Bay MNRF district office, on the MNRF Fisheries Management Zone website and on the Environmental Registry for public viewing and future reference.

4.0 Plan implementation and ongoing commitment to monitoring

An important component of Ontario’s Ecological Framework for Fisheries Management is the implementation of the commitments outlined in fisheries management plans.

Without a commitment to monitoring there is no way to assess the achievement of objectives or the effectiveness of management strategies (e.g. regulations). In a worst case scenario, lack of monitoring could result in a significant negative impact to the resource.

Many components of the FMP outlined herein acknowledge MNRF’s intention to implement effective and meaningful monitoring and adaptive management.

4.1 Monitoring strategy

The monitoring strategy for the plan is intended to improve fisheries management in two ways. First, trends in the abundance and population structure of currently favoured sport fish species will be assessed and will provide information upon which to manage key fisheries in the short term. In the longer term the program will allow the development of improved yield models which will integrate fish harvest and ecosystem factors to predict changes in the sustainability of the fishery relative to long term environmental change.

Several indicators have been identified in the plan to measure the state of the fishery and ecosystem, and/or show progress toward achieving the objectives for management of the recreational fishery and the lake’s ecosystem health. The benchmarks identified for each indicator provide a means to interpret the response of indicators relative to each indicator’s benchmark or reference condition where they exist.

To assess progress toward achieving the goals of the plan, indicators may be assessed individually or combined. Fishery responses can then be tracked over time and compared against management actions and ecosystem influences. Sets of indicators may also track the influence of fishing on ecosystem responses; for example, to explain changes in the fish community.

Unfortunately, there is no single tool that can be utilized to assess the entire fishery and lake ecosystem health; however, there are a number of tools that can be used in combination to monitor the state of the lake and its fishery. For each set of plan objectives, individualized monitoring approaches have been described (Appendices 6-24).

Monitoring of Lake Nipissing will be primarily conducted by the MNRF North Bay District Office. Nipissing First Nation is also currently active in collecting information on the fisheries resource. Partner agencies such as the local Conservation Authority, Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and Nipissing University are also active participants in collecting information on the lake ecosystem.

5.0 Recreational fisheries management strategies

5.1 Walleye

Walleye are the most sought species on Lake Nipissing. Each year more than 70% of recreational angling effort and approximately 90% of commercial angling effort targets walleye. The lake historically experienced over 1 million hours of fishing pressure and harvest levels at or above 100,000 kg of walleye annually. Walleye have been, and remain the most economically and socially important species in the lake, and are considered the most influential top-predator in the Lake Nipissing fish community.

Assessing the Lake Nipissing walleye fishery

Fall Walleye Index Netting (FWIN) and Spring Walleye Spawning Assessment are the two assessment tools used to collect fishery independent data for walleye. These provide measures of relative abundance and biomass, as well as information on their growth rates and other life history characteristics.

Creel surveys, conducted during both the open water and winter seasons involve counting and interviewing anglers about their daily catches and provide us with fishery-dependent data used to estimate the recreational fishing harvest (size and number of fish) and effort (hours).

Commercial fishermen complete daily catch reports which provide commercial harvest levels (species and number). Together, these surveys help determine the overall health and sustainability of the population and whether current regulations are directing sustainable harvest levels of the fishery.

Status of walleye fishery in Lake Nipissing

During the 1960s and early 1970s, Lake Nipissing became an important destination for walleye anglers.

This trend has continued to the present, with ice and open water anglers spending half a million hours each year pursuing walleye on the lake.

Trends in Walleye harvest and abundance by decade

In the 1970s and 1980s, harvest of walleye was very high, exceeding 100,000 kilograms per year for the recreational fishery.

In the 1990s, management reports identified that annual combined recreational and commercial walleye harvests should not exceed 100,000 kilograms. As such, walleye harvests were reduced slightly through the 1990s to 100,000 kilograms per year on average. Despite the harvest reduction, the population declined in the 1990s, likely due in part to high exploitation in earlier decades. Concerns over this decline led to management actions in the mid-2000s to reduce the harvest to 66,000 kilograms per year.

Despite the more recent reduction in combined harvest, the walleye population is continuing to decline in the lake, with the current biomass at half of what it was in the 1980s (Figure 6).

Walleye population health

The Lake Nipissing walleye population continues to exhibit many signs of a stressed fishery. Current walleye abundance is estimated to be too low to support the previous estimated sustainable harvest of 66,000 kilograms per year. Although there have been other ecosystem changes such as the colonization of Lake Nipissing by double-crested cormorants (Phalocrocorax auritus) and the spiny water flea (Bythotrephes longimanus), overharvest from fishing has placed the walleye population in a vulnerable state.

FWIN data from 2013 has shown a significant decline in walleye biomass in the lake, and more specifically, abundance and biomass of sexually mature fish (Figure 7). The majority of the population is currently two to three years old and their condition is showing signs of decline.

The 2013 FWIN results indicated that it was a poor year for recruitment and numbers of young of the year were below average when compared to historical averages and the previous four years (2009-12). An overall reduction in the number of spawning females detected in the 2013 Spring Walleye Wasi Falls Spawning Assessment may have been the cause for low observed abundance of young of the year walleye. The spawning assessment data also observed that the average age of spawning females has shifted from 6 years to 10 years. Fewer younger females were observed in the spawning population than previous years; with the majority of the spawning population comprised of older females.

In 2012, an extensive walleye data review clearly identified human exploitation as the cause of the walleye population decline. The review also identified a fish community shift resulting from the decline in the walleye population. This resulted in the yellow perch population increasing dramatically with the relative absence of historically higher densities of walleye as the top predator in the lake.

The loss of adult walleye more than five years old has varied between 30 and 55 per cent over the last five decades (Figure 8). The recent reduction in adult mortality can be attributed to management actions that have been implemented on the lake in recent years. For example, the decrease in adult mortality from the 1970s to the 1980s appears to be related to a delayed spring angling opening, and a similar decline in the 2000s has been attributed to reduced limits and the protected slot size.

Between 2004 and 2008 marginal improvements in the spawning stock were realized as a result of the implementation of the later season and protected slot. Unfortunately, despite these ameliorations, growth over- fishing had started to occur on the lake (Morgan 2013).

Growth over-fishing occurs when the young fish that become available to the fishery (the recruits

), typically fish 35 cm and larger in length, are caught before they can grow to a reasonable size, or more importantly before they reach spawning status (Figures 9 & 10). This is the result of the fishery (anglers) now keying in on and targeting the most abundant size class in the fishery, the fish less than 40 cm.

While the recreational harvest was targeting the more abundant juvenile fish, the walleye population was also experiencing increasing growth rates by these immature walleye. Juvenile walleye were found to be growing faster and becoming vulnerable to the fishery (recreational and commercial) earlier (prior to reaching spawning status) than ever before. This is a response to the stressed population condition, with low densities of walleye.

This resulted in an increasing proportion of the harvest (recreational and commercial) targeting juvenile fish that had yet to spawn at least once in their lifetime.

Examination of historical data revealed that a 35 cm walleye in the 1970’s, 80’s and most of the 90’s was approximately 4 years old. The age of a fish this size had rapidly decreased to approximately 1.5 years old by 2011 (Figure 10). Of more importance, is that the increase in size, occurred without an appropriate shift in the age at first spawning (i.e. 50% maturity remained 4 to 5 years old for females). This early entry to a vulnerable size resulted in juvenile mortality rates that increased beyond 60% per year and was effectively limiting recruitment to the spawning stock.

In 2009, having exhausted its capacity for a growth response, the spawning stock declined suddenly and slipped into a recruitment over-fishing situation. Recruitment over-fishing occurs when the adult spawning stock population is depleted to a level where without appropriate measures being taken it no longer has the reproductive capacity to replenish itself (i.e. there are not enough adults to produce offspring). This is generally addressed by placing moratoriums, quotas and minimum size limits on a fish population that serves to increase the abundance of the adult spawning stock in the fishery. There may be an opportunity to increase the adult spawning population on Lake Nipissing by protecting strong year classes of walleye until they are able to spawn.

With noted increased juvenile mortality and an abundance of exploitable walleye (walleye of the size targeted by either the recreational or commercial fishery) that has declined to its lowest level yet, the MNRF recognized a need to take interim action prior to the completion of the new fisheries management plan. As such, a group of stakeholders was brought together to gather advice on preferred and acceptable immediate and interim actions that could be taken to reduce the fishing mortality of walleye. The 2012 walleye regulation was an interim measure developed by MNRF with input from the Lake Nipissing Fisheries Management Plan Advisory Council (LNFMPAC). On January 1, 2013, the daily angling catch limits for walleye were reduced to 2 fish (from 4) for a sport licence and 1 fish (from 2) for a conservation licence, while maintaining the protected slot size regulation.

Over the fall of 2012 and winter of 2013, MNRF science and field staff worked in collaboration with Nipissing First Nation’s fisheries department staff to develop a surplus production model for Lake Nipissing’s walleye population (Zhao and Lester 2013). The purpose of the surplus production model was to determine the optimum walleye harvest level the lake could support. This is the harvest level that produces the maximum number of walleye that can be sustained without affecting the long-term productivity of the walleye stock, otherwise known as the maximum sustainable yield (MSY).

As a result of this analysis, it was revealed that the walleye stock has been overfished and unhealthy for the entire duration of the data collection period (since 1976). In turn, the model provided a new set of reference points that suggest that the lake’s ability to produce walleye is about 85% of the previous estimate from the 2007 - 2010 Fisheries Management Plan (i.e. maximum sustainable yield = 76,746 kg/yr (current) vs. 90,000 kg/yr (2007-2010 FMP)). The ability of this model to project into the future and provide estimates of safe annual harvest specific to the Lake Nipissing walleye biomass represents a significant progression in the management of the lake.

This new analysis was used to develop a model that identifies a range of harvest options based on the status (health) of the fishery for resource managers to use to make informed decisions on setting annual harvest levels for Lake Nipissing’s fisheries. The Lake Nipissing Walleye Risk Assessment Model for Joint Adaptive Management developed by Rowe et al., 2013 characterizes the risk associated with the status of a given population (based on walleye biomass and harvest levels) relative to their respective reference points (safe levels of fishing mortality), and current levels of fishing mortality. The model identifies the level of risk (high, medium or low) associated with specific management actions (regulations) in addition to providing the risk associated with a range of annual harvest levels for the lake.

Modelling results were presented to the LNFMPAC to seek their input on the preferred option to be implemented to facilitate the recovery of walleye. Results from the model indicate that the current Lake Nipissing walleye population is at a high risk of a large decline. The majority of the advisory council agreed that a low risk, short-term recovery period was the preferred option moving forward with the walleye recovery plan.

The model was used to project recommended 2013 combined (recreation and commercial) harvest levels. It suggested that safe harvest levels, those that are low risk and support a shorter recovery period (10 years) would be ≤ 29,690 kg. Harvest levels that pose a higher risk and are associated with a longer-term (20 years) recovery period, would be ≤ 46,562 kg.

To support the recommended reduction in harvest and to expedite walleye recovery actions, the 2012 walleye regulation was implemented on January 1, 2013 with a reduced creel limit from 4(2) to 2(1) fish while maintaining the 40-60 cm protected slot. However, harvest in the recreational fishery continues to increase due to angler success and increased participation resulting directly from the recruitment and availability of four very strong year classes to the angling fishery. Should the regulation change not have been implemented however, the recreational fishery would have observed much higher harvest levels and more specifically, would have been significantly over the recommended harvest levels versus being only slightly over for the 2013 season.

Thus, moving forward with the refinement of the risk assessment model and current data, MNRF developed new regulations that considered the current status of the fishery, the root causes of the decline, and support the recovery of the walleye population. The risk assessment model will continue to be used to support management decisions to determine real time trajectories for the population towards recovery or collapse.

Walleye stocking

Supplemental walleye stocking has a long history on Lake Nipissing, with earliest known records dating back to 1920. While periodic in nature for the first 50 years, annual volunteer community based stocking began with the establishment of a community-run hatchery in 1984 which continues operations to this day.

The licensed community hatchery has been permitted to collect and fertilize two million eggs from spawning walleye within Lake Nipissing annually. Assessment of the local spawning site, where collection occurs, determined that this quantity was within safe limits to retain genetic diversity within the natural population based on characteristics of spawning populations at that time and these levels were supported by scientifically accepted genetic principles (Ryman and Laikre 1991). Spawning assessments will continue to inform safe quantities permitted for collection by community hatchery programs.

The 2007–2010 Interim Fisheries Management Plan recommended a study on the effectiveness of the community hatchery stocking program on the lake to determine how the current program should move forward. The study examined the relationship between walleye summer fingerling stocking rates and young-of-the-year catches in the Fall Walleye Index Netting assessment. No relationship was found. Similarly, there was no significant relationship between the number of walleyes stocked and the contribution of these fish to the population or adjacent year classes. Finally, there was no relationship between the number of walleye stocked and angler catch rates either 2 or 3 years later when those fish would have been recruited to the angling fishery. The study concluded that this low-intensity stocking program was not providing a measureable benefit to the walleye population or the fishery of Lake Nipissing, (Kaufman 2007) which was to be expected by a small scale stocking program.

Lake Nipissing stocking efforts are a means of collaborating with stakeholders to promote an understanding of the need to manage the Lake Nipissing fishery and to engage partners in the stewardship of the lake. It is understood that stocking will not address the cause of Lake Nipissing’s walleye decline (overharvest).

Based on the fact that Lake Nipissing is a large lake with a viable naturally reproducing walleye population and a complex fish community, it does not meet the criteria for supplemental stocking and was determined that it would not be appropriate to enhance the existing stocking efforts beyond the status quo at this time. Assessment of the donor spawning population and rearing success will occur annually to minimize impacts to natural populations and maximize hatchery success. The number of eggs licensed for collection each year may vary as a result of this assessment.

Stocking is currently permitted on Lake Nipissing, primarily as an educational and partnership development tool since the lake contains a walleye population with the capacity to naturally produce young fish. Opportunities exist to expand collaborative efforts with various stakeholders, such as Nipissing University and others to fill information/assessment gaps on stocking effectiveness and alternate techniques. This research could be used to enhance rearing success and survival and pilot alternative non-stocking techniques.

Management issues, challenges and opportunities

Issues and challenges:

- Expectations about the collective demand for walleye in comparison to past harvests and the productivity of the stock

- Controlling the magnitude of recreational harvest in an open-access fishery

- Current shift in compliance levels on the lake, with perception that non-compliance has increased

- Lack of understanding of unmeasured harvest (e.g. both recreational and commercial non- compliance)

- Expectations around the effectiveness of supplemental stocking to recover the population and maintain high harvest rates by local interest groups

- Continued pressure from local interest groups to increase existing supplemental stocking efforts over a naturally producing population which conflicts with current science, stocking management principles, and general and species-specific stocking guidelines.

- Management of the walleye population in the absence of an agreed upon allocation mechanism between commercial and recreational interests that facilitates the alignment of both fisheries management objectives and management actions

- The disconnect between very high angling catch rates and messages about the walleye population being under stress and reductions in recreational fishing limits

- The unknown level of First Nation subsistence harvest

Opportunities:

- The integration of the Risk Assessment Model as the basis for a more adaptive, proactive management system that provides a range of safe annual harvest levels based on the stock status and common reference points for walleye recovery and population health

- Four strong year classes were realized from 2009-2012; 2014 implementation of the regulation change was required to protect the last (2012) of these strong year classes with hopes of rebuilding the population; all four year classes were vulnerable to both fisheries as of January 1, 2014

- Improving the collaboration between MNRF and Nipissing First Nation’s commercial and recreational fisheries

- Expanding the collaborative approach to include Dokis First Nation, surrounding municipalities and key stakeholders

- Increase public awareness to the productive capacity of the walleye population and the rationale for various management actions

- Increase the transparency of monitoring results to foster greater public understanding and acceptance of management actions

- Use the existing volunteer efforts to enhance social awareness of issues related to walleye and ecosystem health of Lake Nipissing

Objectives for walleye management

Biological objectives

- Rebuild the walleye biomass in Lake Nipissing to healthy levels (4.6 kg/ha) in 10 years

- Rebuild the age structure of the population to include healthy levels of spawning sized walleye

- Decrease juvenile (30-45 cm) mortality and increase recruitment into the spawning stock

- MNRF, in collaboration with partners to examine previously recommended alternatives to current stocking practices in addition to any new science-based options to traditional stocking of walleye in the lake.

Socio-economic objectives

- Reduce total harvest to a low/moderate risk level over 10 years to initiate recovery of the population

- To balance the effects of managing a sustainable fishery with cultural, social and economic interests

- To provide sustenance for local First Nations

- To balance the needs of commercial and recreational fisheries

- Provide opportunities to fish and to harvest fish for consumption

Ecosystem objectives

- To determine the changes to Lake Nipissing ecosystem and its impacts on walleye recovery rates and endpoints

- To minimize the risk of new environmental stressors such as species introductions

- To provide input on, and mitigation measures for activities that impact walleye productivity

Educational objectives

- To educate all users on walleye biology, status, resulting management actions and the appropriate use of stocking as a management tool on Lake Nipissing.

- To promote awareness about the natural limitations of the walleye population in Lake Nipissing

- To annually report on the state of the walleye population

- To promote safe fish handling techniques to improve post-release survival

Management actions to meet walleye objectives

Appendix 7 provides a more detailed summary of the objectives, indices, targets and timelines associated with each management objective and action for walleye.

1) Change the previous angling regulation to facilitate the recovery of walleye and sustain the fishery into the future.

Appendix 6 provides the rationale for the alternate management options that were considered as part of the development of this plan.

Comparison of previous regulation to the current regulation for Walleye

Previous regulation

- Season: Open January 1- March 15, 3rd Saturday in May to October 15

- Catch Limits:

- Sport – 2

Conservation – 1

- Sport – 2

- Size Limit: none between 40-60 cm

Current regulation

- Season: Open January 1- March 15, 3rd Saturday in May to October 15

- Catch Limits:

- Sport – 2

Conservation – 1

- Sport – 2

- Size Limit: none less than 46 cm

The intent of the new regulation is to:

- Increase recruitment of juvenile walleye into the spawning stock to ensure at least one reproductive event per fish per lifetime

- Increase the abundance of spawning females (>400 mm, age 4.2)

- Increase the abundance and biomass of walleye in the lake and remove from stressed population status

- Select an option with low risk and a short-term recovery period (10 year versus 20 year)

The detailed data review and subsequent FWIN and creel surveys in 2012 and early 2013 identified juvenile mortality as the factor preventing the entry of juvenile fish into the spawning stock in the lake. This was identified as the greatest barrier to the recovery of the walleye population on the lake today. Given the current state of the walleye population, and MNRF’s stated intent of returning the walleye population to a healthy self-sustaining condition, the Advisory Council was nearly unanimous in advocating for a strategy that had the least risk and that fully addressed excessive juvenile mortality rates in the short term (10 year period). The current regulation protects approximately 100% of the male walleye spawning stock and approximately 50% of the female walleye spawning stock with the intention of ensuring that individuals have at least one reproductive event/opportunity in their lifetime prior to being harvested by the recreational fishery. For the walleye recovery strategy to be successful, the harvest of walleye in Lake Nipissing below 46 cm needs to cease.

The minimum size limit set above the size at first maturation for a significant portion of the female population. This helps ensure that each individual has at least one reproductive event during their lifetime.

Public feedback received following the implementation of the recent walleye regulation change (reduction in creel limit from 4 to 2) and during the 2013 open house, indicated that a 2(1) fish limit was not supported by both the recreational anglers and the tourist industry. Despite this, the MNRF has maintained the two fish limit to manage risk to the fishery. This is important to protect a higher proportion of the reproductive potential of the population from recreational harvest, and thereby increasing the chances creating a more robust population for short and long term success.

It should be understood that with the implementation of the new walleye regulation, over the short term, despite potential high catch rates, harvest rates in the recreational fishery will be low until the recruits (2009 on) reach 46 cm in length. It is felt that this is a necessary compromise so the fishery can remain sustainable into the future and recover sooner.

2) Maintain the current fish sanctuaries associated with Lake Nipissing that are designed to protect spawning adult walleye and ensure continued recruitment into the fishery.

- Iron Island: No fishing from March 16 to Friday before 3rd Saturday in May

- Wasi Falls: No fishing from March 16 to Friday before 3rd Saturday in May & October 1 to November 30

- South River (Chapman Chutes): No fishing from March 16 to Friday before 3rd Saturday in May & October 1 to November 30

3) Continue the annual monitoring and assessment program to track walleye recovery through time; to continue to inform sustainable harvest levels for not only the recreational fishery but also the commercial fishery; and continue to monitor and evaluate regulations impacts and harvest levels using the risk assessment model and adaptive management approach.

One of the key components to the success of the recovery of the walleye population, and attaining the objectives of this fisheries management plan, is the MNRF’s commitment to carry out our annual monitoring and assessment program on the lake.

Lake Nipissing will continue to be managed on an individual lake basis due to its significance as a specially designated waterbody. Assessments will continue to be implemented at the lake level as per the frequency outlined herein or the applicable standardized protocol.

The following monitoring activities are key components of the monitoring and assessment program. These will continue to be implemented on an annual basis, or as specified, to assess the status of the resource, the effectiveness of the management objectives and strategies identified herein, and inform any future management actions to be implemented.

- Annual FWIN Surveys

- Annual Creel Surveys

- Annual Walleye Spawning Assessments at major spawning sites (spawning stock assessment and mark recapture program)

- Annual supplemental research to support status of the resource reports, management issues and challenges, and future management actions as they relate to walleye

4) Continue collaborative efforts with First Nations on resource monitoring in a proactive, flexible manner that addresses the subsistence, commercial and recreational demand for the walleye resource.

The MNRF recognizes the Aboriginal and Treaty rights of both Dokis and Nipissing First Nation’s to fish Lake Nipissing for sustenance. In addition, R. v. Commanda 1991 recognized Nipissing First Nation’s right to commercially fish Lake Nipissing. A collaborative approach will foster an understanding and respect between the fisheries resource managers and their objectives. Open and transparent data collection and sharing among parties will contribute to an overall understanding of the use patterns from each fishery for the betterment of the walleye population, the fisheries, and the lake ecosystem as a whole.

Over the duration of the previous management plan, MNRF and NFN collaborated on a number of assessment projects, including the 2012 FWIN and 2013 Creel survey. The Lake Nipissing Walleye Management Risk Assessment Model was also collaboratively developed to help inform fisheries resource managers on setting appropriate annual harvest levels for both the commercial and recreational fisheries.

Collaboration is very important amongst Lake Nipissing fisheries managers, and should continue into the future. This includes increasing the participation of Dokis First Nation in the resource management activities occurring on the lake.