2025 Apiculture winter loss report

2025 honey bee colony winter mortality

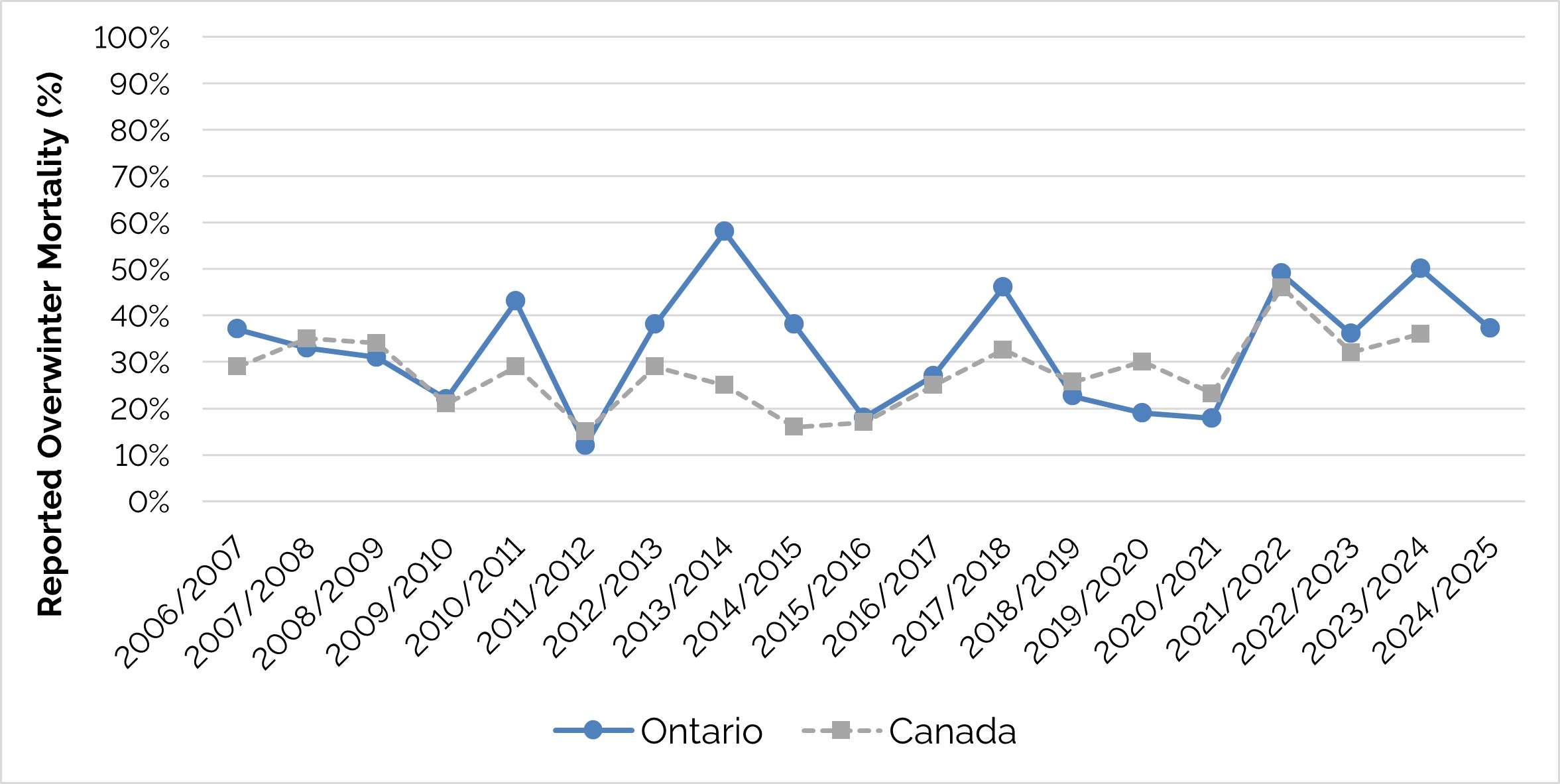

Overwinter mortality for 2024–2025 for commercial beekeepers operating in Ontario was estimated to be 37%, down from the 50% estimated for the winter of 2023–2024.

The estimate for commercial beekeepers in Ontario was approximately 6% less than the estimated loss reported for small-scale beekeepers (43%).

The 2025 estimation for honey bee loss averaged between all of Canada was 39%.

Who we surveyed

In spring 2025, we emailed the survey to:

- 223 registered commercial beekeepers (defined as operating 50 or more colonies)

- 4,008 registered small-scale beekeepers (defined as operating 49 or fewer colonies)

We sent the survey to all registered beekeepers (commercial and small-scale) who provided their email address to the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA).

The survey is voluntary and all responses are self-reported by beekeepers. Data is not verified by OMAFA or any other independent body. The Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists uses a summary of this data along with the data summaries of other provinces for consolidation into a national report.

Responses

Responses were received from:

- 60 commercial beekeepers

- 654 small-scale beekeepers

This represents 16% of beekeepers who received the survey (Table 1). This is a very poor response rate, and the lowest response rate ever received for this survey. The implications of this poor response rate are addressed below.

Of the beekeepers who were registered in Ontario as of December 31, 2024, responses were received from:

- 27% of commercial beekeepers representing 20,019 colonies

- 14% of small-scale beekeepers representing 3,712 colonies

Combined, the responses represent 25% of the total number of colonies registered in 2024 (Table 2).

| Beekeeping regions | # of commercial beekeeper respondents | % of commercial beekeeper respondents | Commercial beekeeper overwinter mortality (%) | # of small-scale beekeeper respondents | % of small-scale beekeeper respondents | Small-scale beekeeper overwinter mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | 17 | 30 | 25.8 | 220 | 34 | 43.3 |

| East | 8 | 14 | 36.1 | 188 | 29 | 47.2 |

| North | 6 | 9 | 40.7 | 80 | 12 | 49.6 |

| South | 21 | 34 | 43.0 | 122 | 19 | 48.0 |

| Southwest | 8 | 12 | 55.1 | 44 | 7 | 47.7 |

| Total | 60 | 27 | 37.2 | 654 | 14 | 43.4 |

| Beekeeper type | # of full-sized colonies put into winter in fall 2024 | # of viable overwintered colonies as of May 15, 2025 | # of non-viable colonies as of May 15, 2025 | Overwinter mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | 20,019 | 12,574 | 7,445 | 37.2 |

| Small-scale | 3,712 | 2,089 | 1,623 | 43.4 |

Only 60 commercial beekeepers responded to this year’s survey.

Since commercial beekeepers make up most of the colonies in Ontario and inform the official statistic for Ontario, a response rate this low means that the results do not accurately reflect the industry. Therefore, conclusions about the health and management practices of the sector should be approached with caution.

While this survey is released at a busy time for beekeepers (spring), beekeepers must make time to take part in this annual survey for the province and industry to have quality data for decision-making. We use this data to:

- design programming

- determine supports

- set priorities

- assess and determine risks, health and economic impacts in the sector

Results

The estimated overwinter honey bee mortality and the number of respondents varied by beekeeping region. Most commercial beekeepers who responded to the survey were from the central and south beekeeping regions. These areas are known to have the greatest number of honey bee colonies in Ontario. Responses from small-scale beekeepers were largely from the central, east and south beekeeping regions (Table 1).

Commercial beekeepers reported the greatest losses in the southwest region while small-scale beekeepers reported the highest losses in the north region (Table 1). Mortality during the 2024–2025 winter differed between the beekeeper groups, with the small-scale beekeepers being 6.2 percentage points higher than commercial beekeepers (Table 2).

When grouped by operation size (number of colonies managed), the honey bee mortality during the winter of 2024–2025 ranged from a low of 32.5% to a high of 50.0% (Table 3).

- Beekeepers operating 201–500 colonies reported fewer honey bee colony losses (32.5%) than all other operation sizes.

- Beekeepers with less than 10 colonies had the highest losses (50.0%).

| # of respondents | # of colonies reported in the fall of 2024 | Overwinter mortality (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 554 | <10 | 50.0 |

| 100 | 10–49 | 41.8 |

| 38 | 50–200 | 39.4 |

| 7 | 201–500 | 32.5 |

| 8 | 501–1,000 | 36.0 |

| 7 | >1,000 | 35.7 |

Although the survey results show that some Ontario beekeepers experienced high losses, there were beekeepers who proved successful in their management practices and reported very low levels of winter mortality. Based on survey results, there were 7 (out of 60, almost 12%) commercial beekeepers who reported winter losses below 15% (estimates ranged from 10.7% to 14.7%).

Consider the scale of loss per operation size when reviewing the overwinter mortality percentages. For example, a loss of 50% in an operation of 1,000 colonies is 500 colonies, whereas a loss of 50% in an operation of 2 colonies is 1 colony. This is not to dismiss the loss experienced by smaller operations, but to flag the impact of loss when operation sizes vary.

Main factors of bee mortality

Beekeepers reported the main factors they believed contributed to their overwinter honey bee mortalities. They could select as many reasons as they felt were applicable. These opinions may be based on observable symptoms, beekeeper experience, judgement or best estimate.

The most commonly reported factors influencing overwinter mortality (Table 4) by commercial beekeepers included:

- varroa (and associated viruses)

- climate/weather

- weak colonies

The most commonly reported factors influencing overwinter mortality (Table 4) by small-scale beekeepers included:

- climate/weather

- weak colonies

- don’t know

Chemicals and pesticide poisoning

11% or 6 commercial beekeepers and 2% or 12 small-scale beekeepers indicated that they observed or confirmed via laboratory testing that chemicals or pesticides killed their bees. There were 2 additional commercial beekeepers who indicated in the “other” option that they suspected pesticide poisoning.

In 2024, OMAFA received 9 in-season honey bee mortality incident reports:

- 3 reports claimed a spraying incident

- 6 reports did not know if a spray incident occurred

Beekeepers should continue to use the online form to report a significant honey bee mortality incident experienced during the active beekeeping season to the Ontario Apiary Program.

If beekeepers suspect the acute mortality of their bees is related to pesticide exposure, they need to report it to the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks’ (MECP) Spills Action Centre at

Learn more about pollution reporting for the public.

| Suspected cause(s) of colony loss | % of commercial beekeepers reporting | % of small-scale beekeepers reporting |

|---|---|---|

| Climate/weather | 47 | 30 |

| Exposure (observed and/or laboratory-confirmed) to environmental chemicals or pesticides | 11 | 2 |

| Poor queens | 18 | 12 |

| Starvation | 15 | 7 |

| Varroa mites and associated viruses | 55 | 20 |

| Weak colonies in the fall | 33 | 24 |

| Not applicable as no-to-minimal colony loss | 0 | 13 |

| Don't know | 15 | 23 |

| Other | 7 | 6 |

| Mammal | 2 | 2 |

Management practices for pests and disease

Varroa mites (Varroa destructor)

Effective monitoring and management practices are essential to combat varroa mites:

- Monitoring, frequent sampling for varroa mites, and timely application of varroa mite treatments are crucial for managing this serious honey bee pest.

- Without proper varroa mite management by beekeepers, colonies are at a high risk of death and spreading varroa mites to other nearby colonies.

- Research has demonstrated that inadequate varroa mite control is the primary cause of winter mortality in honey bee colonies in Ontario

footnote 3 .

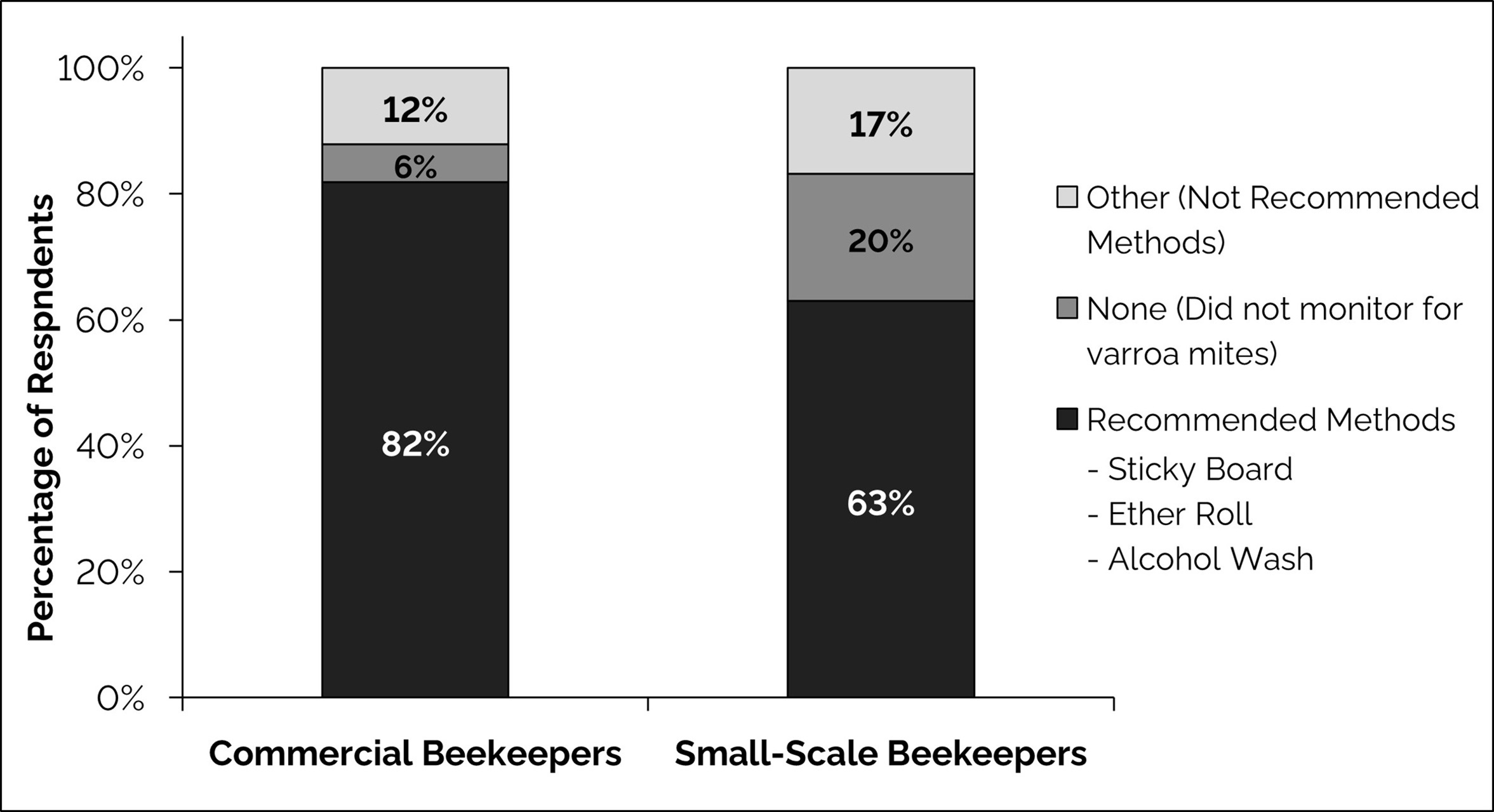

In this survey we asked beekeepers how they monitored for varroa mite infestations (Figure 1) and which treatments they used at the beginning (spring), mid-season and the end (late summer/fall) of the 2024 beekeeping season (Table 5).

Accessible description of Figure 1

Proportion of beekeepers monitoring for varroa mites

Of the beekeepers who responded to the varroa mite monitoring question, 94% of commercial beekeepers and 80% of small-scale beekeepers stated they monitor for varroa mite infestation in their colonies (Figure 1).

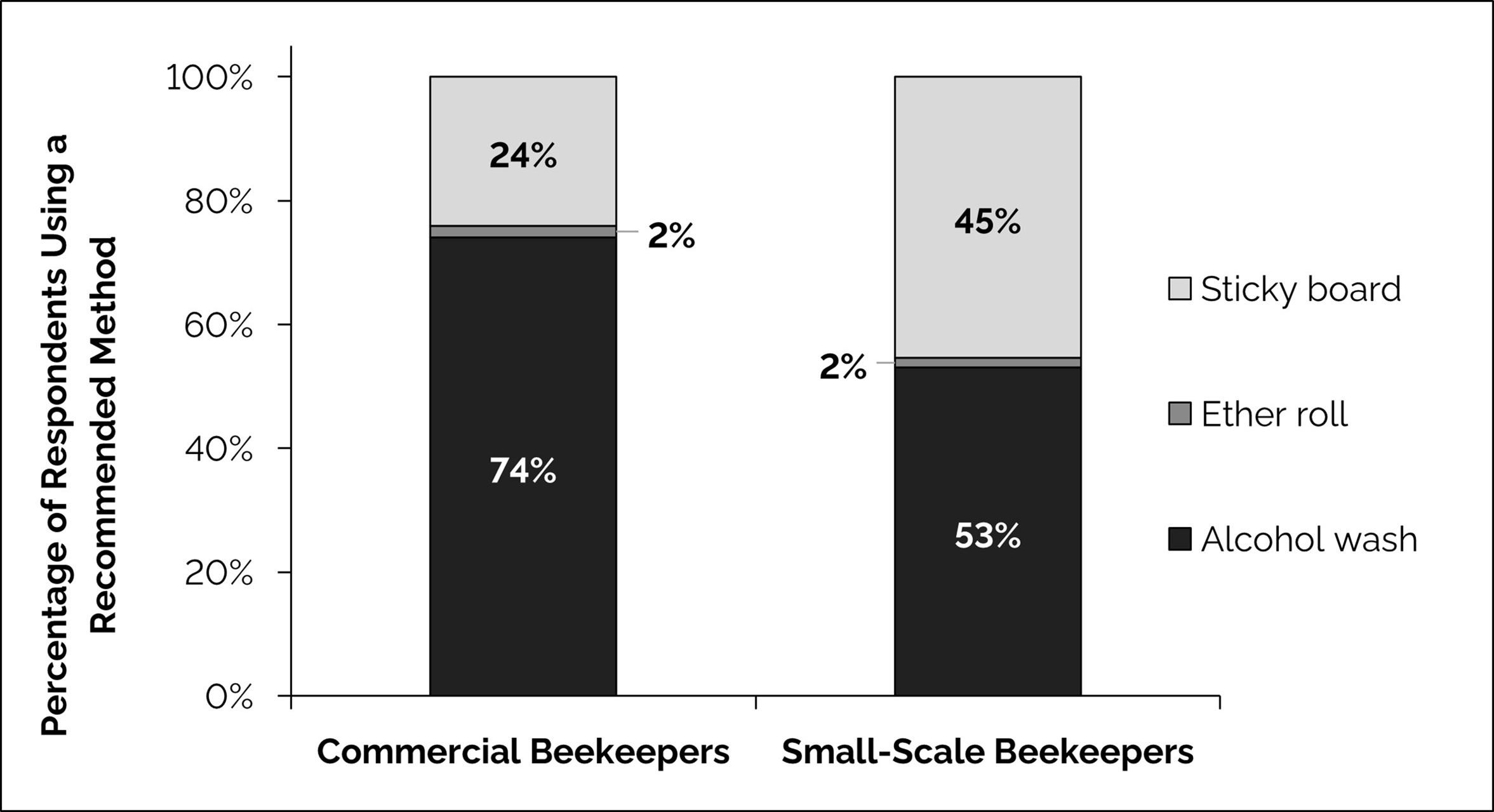

However, out of these overall totals, only 82% of commercial beekeepers and 63% of small-scale beekeepers used a recommended monitoring method (that is, alcohol wash, sticky board or ether roll) to monitor for varroa mite infestation in their colonies (Figure 2).

Accessible description of Figure 2

Concerns with monitoring

12% of commercial beekeepers and 17% of small-scale beekeepers who are monitoring for varroa mites are using methods that are not recommended (Figure 1).

When commercial beekeepers selected the “Other” (non-recommended methods) option, they reported using:

- CO2 roll (2%)

- sugar shake (6%)

- visual inspection of drone brood or for damage (5%)

When small-scale beekeepers selected the “Other” (non-recommended methods) option, they reported using:

- CO2 roll (0.4%)

- sugar shake (8%)

- visual inspection of drone brood or bottom boards (10%)

- other:

- brood assays

- bee scanning app

- soap wash

The sugar shake and CO2 roll methods are not recommended for use as they can be unreliable and are not tied to established treatment thresholds for Ontario.

Visually checking for mites is also not recommended as this method is not proven to yield usable information. In particular, checking for varroa mites visually and without another method of sampling (for example, alcohol wash or sticky board) is not effective as the levels of varroa cannot be quantified in this manner and as varroa mites are not always easy to observe on honey bees or in the colonies leading to unreliable counts. Additionally, if varroa mites can be readily observed on adult bees the infestation is too high and damage has already occurred.

More concerning, 6% of commercial beekeepers and 20% of small-scale beekeepers reported no monitoring for varroa mites at all (Figure 1). Given the significant threat varroa mites pose to the industry, recent high winter loss estimates may be linked to insufficient monitoring and management practices amongst some beekeepers.

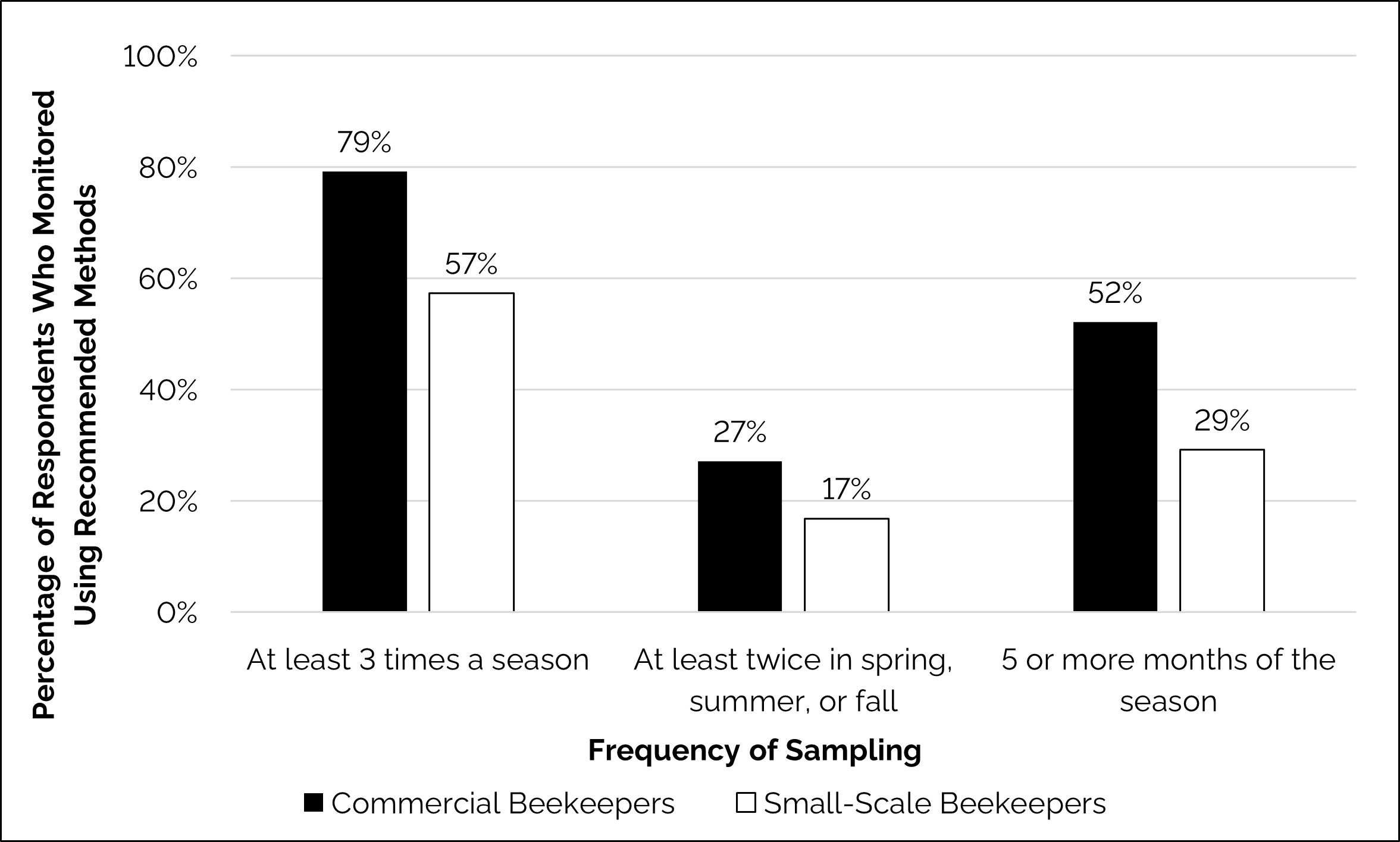

Frequency of monitoring for varroa mites using recommended methods

More than half of beekeepers in each category are using recommended methods to monitor for varroa mites (Figure 1), though the frequency of monitoring varies widely. Frequent sampling is important as it ensures that beekeepers know their varroa mite levels before they get too high and those levels then guide beekeepers on when to treat for varroa (in line with established treatment thresholds).

Figure 3 shows:

- most beekeepers are sampling 3 or more times a year

- the second highest frequency category was beekeepers (52% and 29% of commercial and small-scale beekeepers respectively) sampling 5 or more months throughout the beekeeping season

- a smaller proportion of survey respondents are sampling for varroa mites at least twice per season

Accessible description of Figure 3

Overall, this data is encouraging as it demonstrates that many beekeepers are sampling multiple times throughout the beekeeping season. Whether this is adequate may depend on seasonal dynamics and variation in mite populations. At the same time, survey results show that there must be improvement in the frequency of monitoring for varroa mites for both commercial and small-scale beekeepers. Sampling for varroa every month (in a proportion of colonies and bee yards) is strongly advised to manage this serious pest.

25% of commercial beekeepers and 14% of small-scale beekeepers reported to be sampling before and after every treatment.

Monitoring frequently and after application of treatment, particularly as the beekeeping season progresses, is one of the most important management practices beekeepers can perform. This practice ensures timely application of varroa mite treatments and prevents damaging levels of varroa, especially in the bees going into winter.

Treatments used to control varroa mites

Ontario beekeepers use a variety of treatment options to manage varroa mites (Table 5). The survey asked beekeepers to report their use of varroa mite treatment options during 3 periods in 2024. These periods are defined as:

- spring: from the end of winter to the start of the honey flow

- mid-season: from the start to the end of the honey flow

- late summer/fall: when the last supers were removed for honey production to when colonies were managed for winter

As reported by commercial beekeepers, the most common chemical method of varroa mite treatment was oxalic acid with 40% and 66% of survey respondents using it in the spring and late summer/fall of 2024, respectively (Table 5).

As reported by small-scale beekeepers, the most common chemical methods of varroa mite treatment were Apivar® in spring (18%) and oxalic acid (38%) in late summer/fall of 2024.

Overall, Apivar®, oxalic acid and formic acid are the most widely used treatments for varroa mite control.

| Varroa mite treatment (active ingredient) | Spring 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers | Mid-season with honey supers 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Mid-season with honey supers 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers | Mid-season without honey supers 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Mid-season without honey supers 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers | Late summer/fall 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Late summer/fall 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apivar®(amitraz) | 35 | 18 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 43 | 31 |

| Bayvarol® (flumethrin) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thymovar® (thymol) | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 3 |

| ApiLifeVar® (thymol) | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 2 |

| 65% formic acid – 40 mL multiple applications | 13 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 20 | 4 |

| 65% formic acid – 250 mL single application (mite wipe) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| MAQS® (formic acid) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Formic Pro (formic acid) | 18 | 15 | 30 | 14 | 15 | 8 | 23 | 23 |

| Oxalic acid – drip | 15 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 33 | 15 |

| Oxalic acid – sublimation | 25 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 33 | 23 |

| Hopguard II and III® (hop compounds) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| None/no treatment applied | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 0 | 4 |

| Other | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

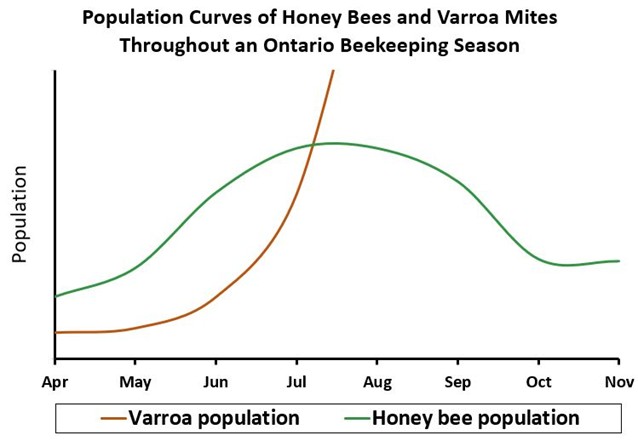

The results showed that 2% of commercial beekeepers and 8% of small-scale beekeepers surveyed are not treating for varroa mites in the spring. Although these percentages are down noticeably from the 2024 survey year, it remains concerning that this many beekeepers are not treating for varroa mites in the spring as spring is a very important time for controlling varroa mite populations to prevent damage and to manage mite population growth at the onset of the beekeeping season (Figure 4). If a beekeeper does not treat in spring, it is unlikely that they will be able to control varroa mite levels for the rest of the season.

Similarly concerning is that 4% of small-scale beekeepers did not use any treatment in late summer/fall. This is another key time to treat as varroa mite levels are peaking (Figure 4). Without reducing varroa mite presence leading up to winter, honey bee colonies are at high risk of mortality leading up to, during, and/or after winter.

During the mid-season of 2024, 8% of both commercial and small-scale beekeepers reported that they did not treat for varroa mites when they had honey supers on. This report further notes that 2% of small-scale beekeepers used Apivar® when honey supers were on the colonies. This is not allowed as this product is not being used in accordance with the label directions.

For those beekeepers that did appropriately apply mid-season treatments, the most common treatment method used by commercial beekeepers was formic acid, and for small-scale beekeepers it was oxalic acid.

The use of mid-season treatments has become an important part of the strategy to prevent varroa mite population growth and damage. The practice of using of mid-season treatments may be relatively new for many beekeepers in Ontario, but this approach is important to incorporate into seasonal management to stay ahead of varroa mite population growth. This becomes crucial as earlier springs, which are becoming more common, can cause varroa levels to peak earlier in the beekeeping season than in previous years.

The least commonly used treatments by both commercial and small-scale beekeepers were:

- Bayvarol®

- MAQS (formic acid)

- ApiLifeVar

- Hopguard II or III

The risk of Varroa mites resistance to amitraz

Varroa mites in Ontario have established resistance (or reduced efficacy) to other compounds, including:

- coumaphos

- fluvalinate

- flumethrin

Apivar® (amitraz) still appears to be an effective option and more efficacious than some other methods of varroa control. Beekeepers must be mindful that any treatment option used against varroa has the potential of developing resistance or having lower efficacy due to environmental conditions where treatments are temperature-dependent.

Beekeepers may also wish to consider using a flash treatment with an organic acid before or after the full use period of Apivar®. As per label instructions, beekeepers should not apply Apivar® with another treatment at the same time as this may degrade the Apivar® and/or impact the bees in ways the manufacturer had not tested for. As amitraz resistance has been documented in varroa mite populations in the United States and other parts of Canada (some prairie provinces), it is important to monitor its status in Ontario. Although amitraz resistant varroa mites have not been confirmed in Ontario at this time, their presence and risk of development cannot be dismissed.

There are numerous, legally registered options for varroa control that are available to Ontario beekeepers. Each of these treatments has its own advantages and disadvantages and beekeepers must make their own decision on what to use balancing:

- efficacy (the proportion or level of kill of the targeted pest)

- temperature thresholds

- cost

- handling time

- application methods

Treatments should not be viewed through the lens of “what is the best treatment”. There is no one treatment that is best as beekeepers must consider the above listed factors. It is likely that multiple treatments will be used in a season. Also, beekeepers may have to consider changing some of their established operational practices to adopt new ways of managing varroa mites including using multiple types of treatments (instead of just one) used in rotation, and likely multiple applications of treatments throughout the beekeeping season, guided by regular sampling for varroa mites and anticipating varroa growth for optimal control of the pest (Figure 4).

New compounds or treatment methods will always be needed for varroa mite control to ensure there is a robust set of options available to beekeepers and to offer the opportunity to rotate treatments. This would allow beekeepers to continue to incorporate effective integrated pest management practices in their beekeeping operation and manage varroa mites for the survival of their colonies. The identification, testing and legal registration of new compounds and treatments can take many years and therefore, beekeepers must seriously consider all currently available treatment options rather than waiting on new ones unless they are imminent.

Beekeeper management practices for varroa mites

The survey results highlight the need for further education and training for beekeepers to improve their integrated pest management practices. While there were encouraging results from the commercial sector, both commercial and small-scale beekeepers need to enhance their monitoring for varroa mites, especially the frequency of sampling. This is a key practice to assess colony health and to improve the survival of colonies going into the winter.

Every beekeeper should regularly monitor a proportion of their honey bee colonies and bee yards for varroa mites including before and after treatment. It is not enough for beekeepers to treat their colonies without knowing their varroa mite levels. Beekeepers who rely solely on treatment without monitoring are at high risk of losing a large proportion of their colonies to varroa mites because without regular monitoring, honey bee colonies may have already reached damaging levels of varroa mites.

Finally, beekeepers should treat at key times of the season, likely a minimum of 3 times, once in spring, mid-season and late summer/fall.

Without monitoring and treating at key times, Ontario beekeepers will continue to lose a high proportion of their colonies, undermining the sustainability of Ontario’s beekeeping industry.

Nosema spp. (N. apis and N. ceranae)

Nosema is a disease that can delay the development of honey bee colonies in spring and reduce the lifespan of individual honey bees. It has not been identified as a factor in colony mortality over winter

In the spring of 2024, 63% of commercial and 52% of small-scale survey respondents indicated that they did not apply nosema treatment. In the fall of 2024, 62% of commercial and 52% small-scale survey respondents did not treat for nosema (Table 6).

| Nosema treatment | Spring 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers | Fall 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Fall 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fumagillin | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 |

| Other | 2 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 |

| None | 63 | 52 | 62 | 52 |

American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae)

More than half of commercial beekeepers who responded to this survey question prophylactically treated healthy-appearing colonies for American foulbrood (AFB) during spring 2024 (57%) and during fall 2024 (55%) with oxytetracycline. By comparison, 12% and 1% of small-scale beekeepers reported prophylactically treating healthy-appearing colonies for AFB with oxytetracycline in the spring and in the fall, respectively (Table 7).

While the prophylactic use of antibiotics can protect bees from the spread of the vegetative (bacterial) stage of AFB, it does not address the spore stage of AFB, which can persist in the wax comb of colonies and equipment for years. Therefore, beekeepers must incorporate frequent examination of colonies for the symptoms of AFB and use biosecurity practices to mitigate the potential spread of AFB spores within and between operations. This year’s version of the survey addresses these different control methods for the first time.

| American foulbrood control method | Spring 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers | Fall 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Fall 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytetracycline, preventatively/prophylactically on healthy appearing colonies | 57 | 12 | 55 | 1 |

| Oxytetracycline, to treat non-infected colonies when AFB confirmed/suspected | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Tylosin, preventatively/prophylactically on healthy appearing colonies | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Tylosin, to treat non-infected colonies when AFB confirmed/suspected | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Licomycin, preventatively/prophylactically on healthy appearing colonies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Licomycin, to treat non-infected colonies when AFB confirmed/suspected | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| No antibiotics used | 32 | 36 | 30 | 36 |

| Other antibiotic treatment | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Burning frames with suspect brood or brood that looks diseased | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Regular replacement of old brood frames (2 or more per year) with new frames | 52 | 15 | 20 | 8 |

| Frequent brood inspection (at least once per month) | 53 | 29 | 47 | 29 |

| No physical or cultural control methods used | 3 | 18 | 3 | 19 |

| Other physical control method | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Regular replacement of old brood frames and frequent brood inspection were more common practices with commercial beekeepers than small-scale beekeepers, perhaps reflecting this group’s experience and training. It was good to see these management techniques practiced by both beekeeper groups, though this survey demonstrates that the proportion of beekeepers using these practices needs to increase. This may be addressed through further training of beekeepers.

European foulbrood (Melissococcus plutonius)

More than half of commercial beekeepers who responded to this survey question prophylactically treated healthy-appearing colonies for European foulbrood (EFB) during spring 2024 (52%) and during fall 2024 (53%) with oxytetracycline. By comparison, 8% and 11% of small-scale beekeepers reported prophylactically treating healthy-appearing colonies for EFB with oxytetracycline in the spring and in the fall respectively (Table 8).

Unlike AFB, EFB is not a spore-forming bacteria. This means that EFB does not have a mechanism (spores) where infective materials can be present for decades in the environment of honey bee colonies and used beekeeping equipment. However, the bacteria may persist in equipment, especially with active infections. Furthermore, EFB may persist in the bodies of honey bees, resulting in future infections. Therefore, while the prophylactic use of antibiotics may protect bees from the spread of EFB, biosecurity practices and removal of infective equipment is important for getting infections under control and ensuring that infections do not persist and/or spread.

There have been reports of antibiotic resistance or lack of response to antibiotics for controlling EFB in British Columbia. Some of this may have to do with nutrition, environmental stressors and even persistence of the bacteria in the bees or environment. Either way, beekeepers cannot rely on antibiotics as a replacement for biosecurity practices and routine management of the brood nest.

| European foulbrood control method | Spring 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Spring 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers | Fall 2024 % of commercial beekeepers | Fall 2024 % of small-scale beekeepers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytetracycline, preventatively/prophylactically on healthy appearing colonies | 52 | 8 | 53 | 10 |

| Oxytetracycline, to treat non-infected colonies when EFB confirmed/suspected | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Oxytetracycline, to treat infected colonies when EFB confirmed/suspected | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| No antibiotics used | 30 | 33 | 25 | 33 |

| Other antibiotic treatments | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Burning frames with suspect brood or brood that looks diseased | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Regular replacement of old brood frames (2 or more per year) with new frames | 47 | 11 | 23 | 8 |

| Frequent brood inspection (at least once per month) | 45 | 22 | 37 | 22 |

| No cultural or physical control methods used | 2 | 19 | 2 | 19 |

| Other physical control methods | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The regular replacement of old brood frames and frequent brood inspection were again more common practices with commercial beekeepers than small-scale beekeepers.

Ontario’s overwinter mortality

The Canadian Association of Professional Apiculturists compiles aggregated overwinter mortality data provided by each province and publishes an annual report on national honey bee colony losses. Figure 5 compares Ontario’s overwinter mortality levels to that of Canada’s. The 2025 estimate for commercial beekeepers in Ontario (37.2%) was approximately 2% less than the estimation for bee loss averaged between all of Canada (39.3%).

Accessible description of Figure 5

Accessible image descriptions

Figure 1. Category of varroa mite monitoring method used by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2024. Survey respondents could select more than 1 method of monitoring when completing the survey.

Figure 1 shows the category of varroa mite monitoring method used by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2024. 82% of commercial beekeepers reported using 1 of the recommended methods, 12% used other/non-recommended methods, and 6% reported no monitoring for varroa mites. 63% of small-scale beekeepers reported using 1 of the recommended methods, 17% used other methods/non-recommended methods, and 20% reported no monitoring for varroa mites.

Figure 2. Breakdown of recommended varroa mite monitoring methods used by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2024. Survey respondents could select more than 1 method of monitoring when completing the survey.

Figure 2 shows the breakdown of recommended varroa mite monitoring methods used by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2024. Among commercial beekeepers who reported using a recommended method, 74% used the alcohol wash, 24% used sticky boards, and 2% used the ether roll. Among small-scale beekeepers, 53% used the alcohol wash, 45% used sticky boards, and 2% used the ether roll.

Figure 3. Frequency of varroa mite monitoring using recommended methods by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2024.

Figure 3 shows the frequency of varroa mite monitoring using recommended methods by commercial and small-scale beekeepers in 2024.

Beekeepers who sampled at least 3 times a season:

- Commercial beekeepers: 79%

- Small-scale beekeepers: 57%

Beekeepers who sampled at least twice a season:

- Commercial beekeepers: 27%

- Small-scale beekeepers: 17%

Beekeepers who sampled at least once in 5 of the 9 months of the entire beekeeping season:

- Commercial beekeepers: 52%

- Small-scale beekeepers: 29%

Figure 5. Overwinter mortality (%) reported by commercial beekeepers in Ontario (blue) and Canada (grey) from 2006–2007 to 2024–2025.

Figure 5 shows the percentage of overwinter mortality reported by beekeepers in both Ontario and Canada from 2007 to 2025. The reported overwinter mortality in Ontario and Canada (respectively) was:

- 2007: 37% and 29%

- 2008: 33% and 35%

- 2009: 31% and 34%

- 2010: 22% and 21%

- 2011: 43% and 29%

- 2012: 12% and 15%

- 2013: 38% and 29%

- 2014: 58% and 25%

- 2015: 38% and 16%

- 2016: 18% and 17%

- 2017: 27% and 25%

- 2018: 46% and 33%

- 2019: 23% and 26%

- 2020: 19% and 30%

- 2021: 18% and 23%

- 2022: 49% and 46%

- 2023: 36% and 32%

- 2024: 50% and 35%

- 2025: 37% and 39%

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Some beekeepers who reported "other" provided multiple suspected causes of death in their response. Each beekeeper who reported "other" is only counted once.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Commercial beekeepers who reported “Mammal” as the main cause of death of their colonies indicted that bears were the mammal 100% responsible, whereas, small-scale beekeepers who reported “Mammal” as the main cause of death of their colonies were evenly split with 50% citing bears and 50% citing mice as the mammals responsible.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Guzmán-Novoa, E., L. Eccles, Y. Calvete, J. McGowan, P. Kelly and A. Correa-Benítez (2010). Varroa destructor is the main culprit for the death and reduced populations of overwintered honey bee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Ontario, Canada. Apidologie 41(4): 443-450.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Emsen, B., E. Guzman-Novoa, M. M. Hamiduzzaman, L. Eccles, B. Lacey, R. A. Ruiz-Pérez and M. Nasr (2016). Higher prevalence and levels of Nosema ceranae than Nosema apis infections in Canadian honey bee colonies. Parasitol Res 115(1): 175-181.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Emsen, B., A. De la Mora, B. Lacey, L. Eccles, P. G. Kelly, C. A. Medina-Flores, T. Petukhova, N. Morfin and E. Guzman-Novoa (2020). Seasonality of Nosema ceranae infections and their relationship with honey bee populations, food stores, and survivorship in a North American region" Veterinary Sciences 7(3): 131.