The content on this page is no longer up to date. It will remain on ontario.ca for a limited time before it moves to the Archives of Ontario.

Background

Origins of the AFC Concept

The roots of the AFC movement can be traced back to the beginnings of the environmental gerontology discipline, which suggests that the ongoing relationship between people and their physical and social environment affects human development and quality of life.

The Benefits of Age-Friendly Communities

Communities that provide the services, social environments and physical environments to create age-friendly communities reap the dividends that older adults can bring to their communities, benefiting all residents. Accessible spaces that accommodate those who are older or have disabilities also help others who encounter functional obstacles in their daily lives — mothers, parents with infants and strollers and people with chronic health ailments.

Economic Benefits

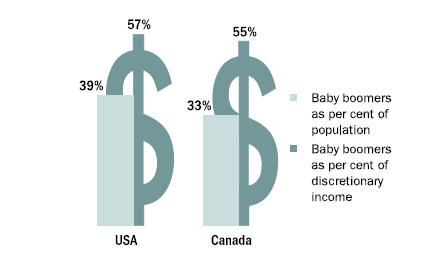

The demographic reality is that the younger generations no longer represent the biggest growth market.

Age-Friendly Characteristics

How do we characterize an ‘Age-friendly community’?

Age-friendly communities create supportive social and physical environments that enable older people to live active, safe and meaningful lives and continue to contribute in all areas of community life:

Measurable characteristics: residential density, land-use mix, street connectivity and access to green spaces.

Subjective measures: concerns about crime, personal safety and environmental variables such as noise and neighbourhood aesthetics.

Social factors: the stability of a neighbourhood’s residents, the presence of relatives or close friends, and the degree of social interaction among neighbours.

Accessibility: in the home environment and in the larger neighbourhood context.

Support: for older adults’ continuing participation in the social, economic, cultural and civic affairs of a community.

Person-Environment Fit

Person-environment fit (p-e fit) means the relationship between a person’s physical and mental capacity and the demands of his or her environment.

Most people experience some decline in capacity as they age. Age-friendly communities aim to decrease the environmental demands on an individual, maintain a desirable p-e fit and enhance quality of life.

People with higher ability levels living in environments with lower demand levels create a desirable p e fit and appropriate conditions for aging in place. Lower levels of ability in conditions of high environmental demand create an undesirable p-e fit, which contributes to poorer quality of life.

Assessing individual needs can help identify tangible opportunities for improving a community’s age-friendliness by highlighting gaps in the community resources that should be supporting older adults’ needs. To do this, you have to collect information about:

The person: Older adults’ ability to complete activities of daily living and their perceptions of what is relevant for achieving a high Quality of Life (QoL) (for example, personal relationships, walkable neighbourhoods, etc.).

The environment: The extent to which your community’s physical and social environments support older adults’ ability to live independently, and whether these resources and the way we treat older adults fosters a high QoL.

A needs assessment based on p-e fit can help you accurately and clearly define existing gaps that threaten your community’s age-friendliness and that present opportunities for improvement.

Community Stories

Acknowledging and learning from the successes of AFC initiatives is key to the continued success of the movement. To achieve this, the guide highlights ten case studies (pages 18, 26, 36, 44, 49, 55, 56, 59, 64 and 66) that explore different approaches communities have taken to improve their age-friendliness. Besides these, many community stories on the Murray Alzheimer Research and Education Program (MAREP) website discuss the positive effects that AFC planning is having across Ontario.

Footnotes

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph Carp, F. (1966). A Future for the Aged: The Residents of Victoria Plaza. Austin: University of Texas Press; Kahana, E. (1982). A congruence model of person-environment interaction, in: M-P. Lawton, P. Windley and T. Byerts (Eds.), Aging and the Environment: Theoretical Approaches, pp. 97–121. New York: Springer; Kleemeier, R. (1956). Environmental settings and the aging process, in: J. Anderson (Ed.), Psychological Aspects of Aging, pp. 105–116. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; Lawton, M-P., and Nahemow, L. (1973). Ecology of the aging process, in: C. Eisdorfer and M-P. Lawton (Eds.), Psychology of Adult Development and Aging, pp. 619–624. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- footnote[8] Back to paragraph Gunter, B. (2012). Understanding the Older Consumer: The Grey Market. London: Routledge.

- footnote[9] Back to paragraph Alley, D., Liebig, P., Pynoos, J., Banerjee, T., and Choi, I. (2007). Creating elder friendly communities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 49(1): pp. 1–18; Landorf, C., Brewer, G., and Sheppard, L. (2008). The urban environment and sustainable aging: Critical issues and assessment indicators. Local Environment 13(6): pp. 497–514; Lui, C-W. Everingham, J-A., Warburton, J., Cuthill, M., and Bartlett, H. (2009). What makes a community age-friendly: A review of international literature. Australian Journal on Ageing 28(3): pp. 116–121; Marshall, V., and Bengston, V. (2011). Theoretical perspectives on the sociology of aging, in: R. Settersten and J. Angel (Eds.), Handbook of Sociology of Aging, pp. 17–34. New York, : Springer; Wahl H-W., and Oswald, F. (2010). Environmental perspectives on aging, in: D. Dannefer and C. Phillipson (Eds.), International Handbook of Social Gerontology, pp. 111–124. London: Sage Publications.

- footnote[10] Back to paragraph Hodge, G. (2008). The Geography of Aging: Preparing Communities for the Surge in Seniors. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press; Teaff, J., Lawton, M., Nahemow, L., and Carlson, D. (1973). Impact of age segregation on the well-being of elderly tenants in public housing. Journal of Gerontology 33: pp. 130–133; Thomas, W., and Blanchard, J. (2009). Moving beyond place: Aging in community. Generations 33(2): pp. 12–17.

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph Lawton, M-P., and Nahemow, L. (1973). Ecology of the aging process, in: C. Eisdorfer and M-P. Lawton (Eds.), Psychology of Adult Development and Aging, pp. 619–624. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; Lawton, M-P. (1982). Competence, environmental press, and the adaptation of older people, in: M-P. Lawton, P. Windley and T. Byerts (Eds.), Aging and the Environment, pp. 33–59. New York: Springer; Schiedt R., and NorrisBaker C. (2004). The general ecological model re-visited: Evolution, current status and continuing challenges, in: H-W. Wahl, R. Schiedt and P. Windley (Eds.), Aging in Context: Socio-Physical Environments, pp. 34–58. New York: Springer.