State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report

The Minister of Natural Resources must report on the protected area system at least once every 10 years. The ministry developed a comprehensive framework to monitor the ecological, social and economic aspects that support sustainable planning and management. This is the basis for the State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report, which describes the state of the province’s protected areas. It covers the period from 2001 to 2009.

Executive summary

Ontario’s system of protected areas includes over 630 provincial parks and conservation reserves covering an area of 9.5 million hectares, or about nine per cent of Ontario. The Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 requires that the Minister of Natural Resources report publicly on the state of the protected area system at least once every five years. To meet this commitment the Ministry of Natural Resources developed a comprehensive framework to monitor ecological, social and economic aspects to support sustainable planning and management of provincial parks and conservation reserves. This information, covering the period 2001-09, forms the basis for this State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report. The report consists of four chapters that collectively describe the state of Ontario’s diverse protected areas.

The first chapter, Background Information, provides context regarding the planning and management of Ontario’s protected areas. Included are a description of the legislative and strategic direction for the protected area system, a brief history of the development of the system and an overview of the planning process for protected areas. Together, these aspects demonstrate an ongoing and evolving commitment to the integrity of the areas that are protected.

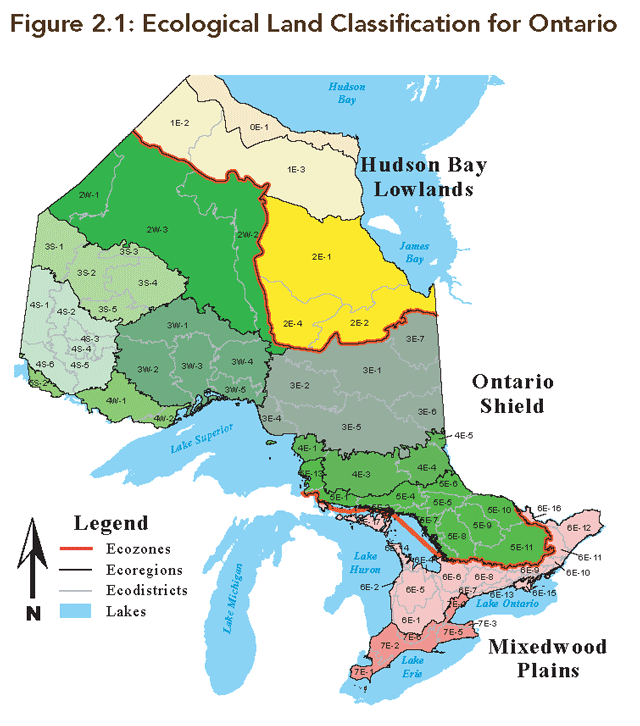

In chapter two, Protecting Ontario’s Natural Diversity, information is provided on the representation of ecological, geological and cultural heritage features within Ontario’s provincial parks and conservation reserves. Ontario has adopted an Ecological Land Classification system as a framework for terrestrial ecosystem representation within the protected areas system. Geological representation is based on environmental themes organized by time, landform evolution and geologic process. Cultural heritage representation is based on a framework that organizes history in relation to aspects of the landscape and physical environment that are basic to human development, including Aboriginal and European settlement.

Chapter three, Ecological Integrity, defines and interprets the term ecological integrity. Factors that contribute to the integrity of protected areas and to the maintenance of ecological integrity over time are discussed. The discussion addresses known pressures, responses to those pressures and the benefits of the protected area system, including the conservation of biodiversity.

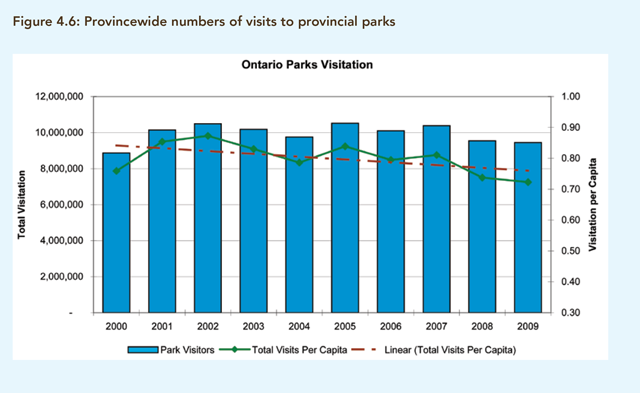

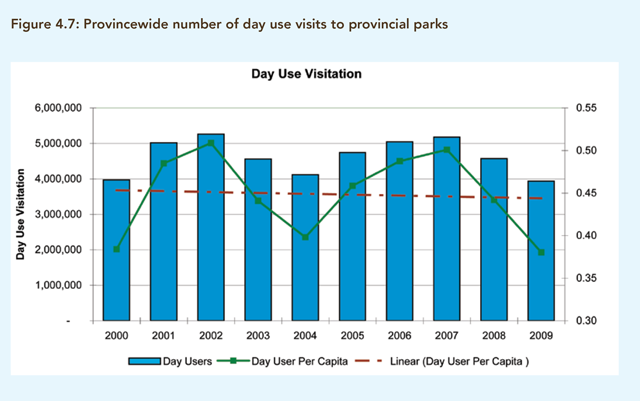

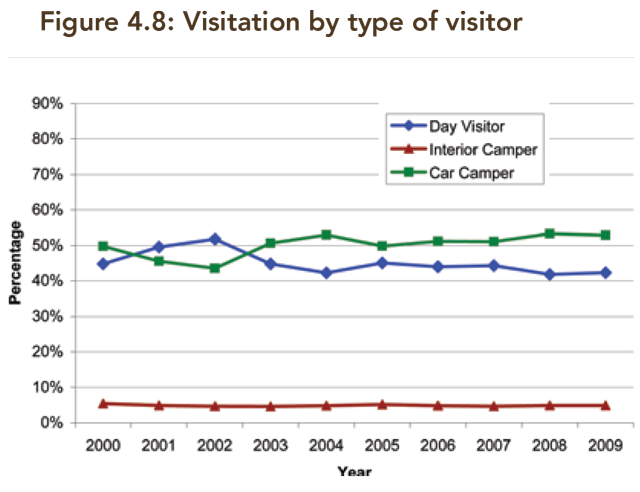

The fourth chapter, Opportunities and Benefits, provides information on the diverse social and economic benefits associated with Ontario’s protected area system. These benefits include opportunities for recreation, traditional uses, research and education, as well as broader ecological and societal benefits. There are about 10 million visits to provincial parks each year, with the majority being day users.

Résumé

Le réseau ontarien de zones protégées comprend plus de 630 parcs provinciaux et réserves de conservation qui couvrent une superficie de 9,5 millions d’hectares au total, soit neuf pour cent du territoire de l’Ontario. En vertu de la Loi de 2006 sur les parcs provinciaux et les réserves de conservation, le ministre des Richesses naturelles est tenu de donner un rapport pbulic sur l’état du réseau de zones protégées au moins tous les cinq ans. Pour satisfaire à cette obligation, le ministère des Richesses naturelles a mis au point un cadre complet de surveillance des aspects écologiques, sociaux et économiques afin de soutenir la planification et la gestion durables des parcs provinciaux et réserves de conservation. Cette information, qui porte sur la période de 2001 à 2009, forme la base du rapport State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report (rapport sur l’état des zones protégées de l’Ontario). Ce rapport (disponible en anglais seulement) est constitué de quatre chapitres qui, ensemble, décrivent l’état des diverses zones protégées de l’Ontario.

Le premier chapitre décrit le contexte dans lequel s’inscrit la planification et la gestion des zones protégées de l’Ontario. Il comprend notamment la description des dispositions législatives et orientations stratégiques qui s’appliquent au réseau de zones protégées, un bref historique de la mise en place de ce réseau et une vue d’ensemble du processus de planification des zones protégées. Ces éléments démontrent un engagement permanent et évolutif à assurer l’intégrité des zones protégées.

Le deuxième chapitre traite de la protection de la diversité naturelle de l’Ontario. Il fournit des renseignements sur la représentation des particularités écologiques, géologiques et de patrimoine culturel dans les parcs provinciaux et les réserves de conservation de l’Ontario. L’Ontario a adopté un système de classification écologique des terres comme cadre pour la représentation des écosystèmes terrestres au sein du réseau de zones protégées. La représentation géologique repose sur des thèmes environnementaux organisés selon l’époque, l’évolution du terrain et le processus géologique. La représentation du patrimoine culturel repose sur une structure qui organise les antécédents historiques en rapport avec les aspects du paysage et du milieu physique qui sont fondamentaux du point de vue du développement humain, notamment l’établissement des communautés autochtones et des Européens.

Le troisième chapitre définit et interprète ce que l’on entend par « intégrité écologique ». Il examine également les facteurs qui contribuent à l’intégrité des zones protégées et à la préservation de l’intégrité écologique au fil du temps. Cet examen traite notamment des pressions connues, des réponses à ces pressions ainsi que des avantages du réseau de zones protégées, dont la préservation de la biodiversité.

Le quatrième chapitre fournit des renseignements sur les divers avantages sociaux et économiques liés au réseau de zones protégées de l’Ontario. Ces avantages incluent les possibilités d’activités de loisirs, d’utilisations traditionnelles, de recherche scientifique et d’éducation, ainsi que des avantages plus larges pour la société et sur le plan de l’écologie. Chaque année, il y a environ 10 millions de visites dans les parcs provinciaux, en majorité pour des visites pendant la journée.

Chapter 1: Background information

1.1 Introduction

The State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report (SOPAR) is the first state of the resource report for Ontario’s provincial parks and conservation reserves. It is based on analysis included in four technical reports.

This report meets a legislative requirement from the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 in which the Minister of Natural Resources must report on the state of Ontario’s provincial park and conservation reserve system.

Ontario’s provincial park and conservation reserve policy is founded on the concept that a naturally diverse and well managed system of protected areas supports a high quality of life for Ontario’s residents and ensures ecological, social and economic benefits now, and into the future.

SOPAR reports on four key program areas.

- It provides context for the planning and management of provincial parks and conservation reserves.

- It outlines the degree to which representative ecosystems, biodiversity and elements of our natural and cultural heritage have been protected.

- It describes the ecological condition, potential pressures and efforts to maintain and enhance the protected areas system.

- It looks at traditional uses, recreational, research and educational opportunities and economic values and impacts at local and provincial scales.

SOPAR details progress made by the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR). It is one of a series of provincial reports produced by MNR such as State of the Forests and other state of resources reporting as well as the State of Ontario’s Biodiversity Report which was produced by the Ontario Biodiversity Council.

SOPAR establishes benchmarks to measure the future progress of the provincial parks and conservation reserves program. It also lets people of Ontario know what’s happening in the province’s parks and conservation reserves.

1.2 Legislative requirements

The Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 (PPCRA) provides direction for provincial parks and conservation reserves in Ontario. The PPCRA came into effect September 4, 2007. The constitutional protection provided under existing Aboriginal and treaty rights for the Aboriginal peoples of Canada is recognized by the act.

To permanently protect a system of provincial parks and conservation reserves that includes ecosystems that are representative of all of Ontario’s natural regions, protects provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage, maintains biodiversity and provides opportunities for compatible, ecologically sustainable recreation.

The PPCRA describes two fundamental principles to guide the planning and management of all provincial parks and conservation reserves: to maintain and restore ecological integrity where possible and to provide opportunities for consultation.

The PPCRA includes the following planning and management principle for ecological integrity:

Maintenance of ecological integrity shall be the first priority and the restoration of ecological integrity shall be considered.

The PPCRA includes balanced objectives for establishing and managing provincial parks and conservation reserves (Table 1.1).

Finally, the PPCRA requires that MNR report on the state of the provincial park and conservation reserve system at least once every five years, and that:

This first State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report is MNR’s response to this mandate.

MNR is also responsible for protected areas established under the Wilderness Areas Act R.S.O. 1990. The Wilderness Areas Act has been used to preserve small areas to protect plants, animals and other values for recreational, research and educational activities. The value and future status of these areas is currently under review.

Table 1.1: Objectives for provincial parks and conservation reserves

[reformatted as a list for accessibility]

Provincial parks

- To permanently protect representative ecosystems, biodiversity and provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage, and to manage these areas to ensure that ecological integrity is maintained.

- To provide opportunities for ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation opportunities and encourage associated economic benefits.

- To provide opportunities for residents of Ontario and visitors to increase their knowledge and appreciation of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage.

- To facilitate scientific research and to provide points of reference to support monitoring of ecological change on the broader landscape.

Conservation reserves

- To permanently protect representative ecosystems, biodiversity and provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage. And to manage these areas to ensure that ecological integrity is maintained.

- To provide opportunities for ecologically sustainable land uses, including traditional outdoor heritage activities and associated economic benefits.

- To facilitate scientific research and to provide points of reference to support monitoring of ecological change on the broader landscape.

1.3 Strategic direction

Strategic direction documents help to guide the Ontario government and its ministries.

Our Sustainable Future outlines MNR’s activities and long-term strategic directions.

- Its vision – sustainable development – requires balancing of social, economic and ecological values. Social and economic benefits depend on sustainable ecological systems.

- Its mission – biodiversity conservation and sustainable use – is the foundation on which sustainable development is based. Sustainability allows us to benefit from ecosystems today, while protecting them for future generations.

- Our Sustainable Future commits MNR to conserve biodiversity, and to undertake state of the resources reporting, such as this State of Ontario’s Protected Areas Report.

1.4 Protected areas – past

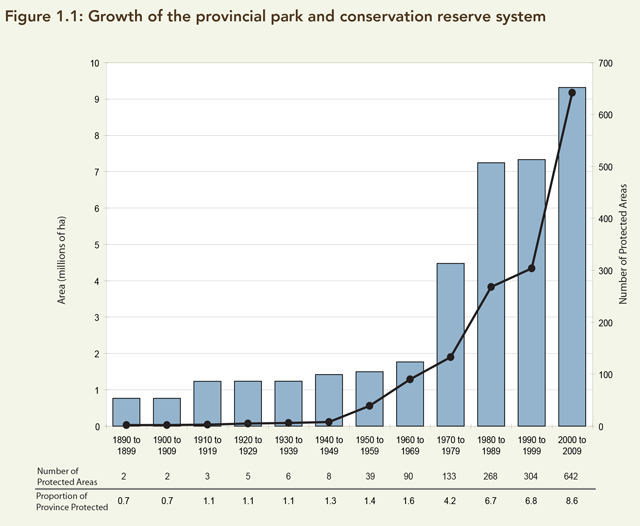

Ontario has established a world class protected area system. It started in 1893 with the creation of Algonquin Park, soon followed by Rondeau in 1894. The first Parks Act was introduced in 1913. By 1950, there were six provincial parks and two national parks in Ontario.

Following World War II, demand for outdoor activities led to the creation of new recreation-based parks. In 1954, the Provincial Parks Act was enacted to guide the development and management of the parks. Increasing awareness and interest in nature led to the creation of the Wilderness Areas Act and the regulation of several small wilderness areas in 1959.

By 1967, Ontario had developed a park classification system and established its first primitive (now called wilderness) and nature reserve class parks. In 1978, Ontario approved a provincial park policy, including a goal, objectives, principles and targets for completing a system of provincial parks. This policy was implemented as part of MNR’s District Land Use Planning program. By 1980, Ontario had established 124 provincial parks with an area of 4.3 million hectares.

In 1983, the Minister of Natural Resources announced 155 new provincial park proposals, including the immediate regulation of six large wilderness parks. In addition, a program to promote the stewardship of Areas of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSIs) on private lands was launched. By 1990, Ontario had established 269 provincial parks with an area of 6.2 million hectares.

A period of expansion in the 1990s was championed by the World Wildlife Fund Canada’s Endangered Spaces campaign. Canada and the provinces signed a Statement of Commitment to Complete Canada’s Network of Protected Areas and the Government of Ontario launched its Keep it Wild Campaign. This led to the creation of conservation reserves under the Public Lands Act and the regulation of nearly a million hectares of land and water as new provincial parks, park additions, and conservation reserves.

By 1997, Ontario had adopted the Nature’s Best Action Plan to complete its network of protected areas. Land use planning and public consultation took place for an area covering more than 45 per cent of the province. This Lands for Life planning process resulted in the release of the Ontario’s Living Legacy: Land Use Strategy in July 1999. The strategy identified 378 new provincial parks, conservation reserves and additions covering approximately 2.4 million additional hectares (Figure 1.1).

Agreements such as Legacy 2000 and more recently Greenlands have helped expand the protected area system through partnerships with private individuals, businesses, Aboriginal peoples and conservation organizations. The Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 took effect in 2007. This new legislation guides the planning, management and operation of these protected areas.

Dedicated protected areas on the Whitefeather Forest were identified and planned with Pikangikum First Nation under MNR’s former Northern Boreal Initiative. The first community based land use plan in the Far North called Keeping the Land – A Land Use Strategy for the Whitefeather Forest was completed in 2006. Regulation of these areas as provincial parks under the PPCRA is ongoing.

In July 2008, the Premier of Ontario announced a land use planning initiative for the province’s Far North, which accounts for 42 per cent of Ontario’s area. The initiative will lead to the protection of at least 225,000 square kilometres of the Far North of Ontario in a network of conservation lands. To achieve this objective, MNR is working jointly with First Nations in the Far North to develop community- based land use plans that will identify areas designated for protection and areas where resources are capable of supporting new economic opportunities.

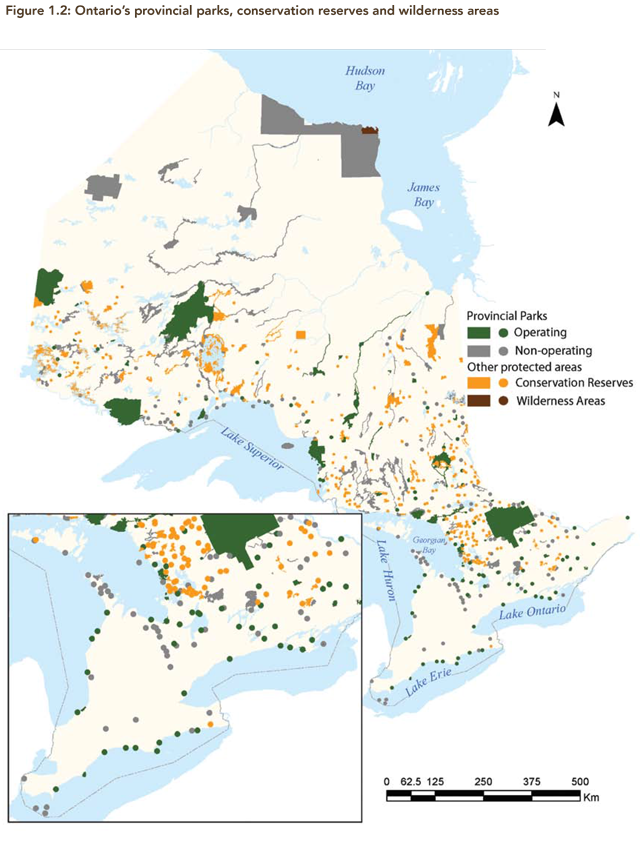

1.5 Protected areas – present

There are currently 330 regulated provincial parks, 294 regulated conservation reserves, 19 recommended new provincial parks and conservation reserves, and 11 wilderness areas, comprising an area of approximately 9.7 million hectares of lands and waters, or about nine per cent of Ontario’s total area (Table 1.2; Figure 1.2).

Regulated provincial parks and conservation reserves have been formally designated by a regulation under the PPCRA. The regulation must be approved by the Lieutenant Governor-in-Council. The regulation process involves detailed mapping and consultation with adjacent landowners.

Recommended protected areas are identified in an approved land use direction, but have not yet been regulated. Recommended protected areas are under interim protection from industrial activities and land dispositions. When the area is regulated the “recommended” label is removed.

| Region | Number | Area (ha) | Percent of ON | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulated Provincial Parks |

330 | 7,897,336 | 7.3 | |

| Regulated Conservation Reserves | 294 | 1,497,040 | 1.4 | |

| Recommended Provincial Parks (new) | 8 | 60,670 | 0.1 | |

| Recommended Provincial Park Additions |

5 | 132,139 | 0.1 | |

| Recommended Conservation Reserves | 11 | 143,705 | 0.1 | |

| Wilderness Areas |

11 | 838 | <0.1 | |

| Total Provincial Protected Areas | 654 | 9,730,286 | 9.0 | |

| National Parks | 5 | 208,160 | 0.2 | |

| Total Provincial and Federal Protected Areas | 659 | 9,938,446 | 9.2 | (including Algonquin R/U Zone) |

| Algonquin Recreation/Utilization Zone | 1 | 594,860 | 0.6 | |

| Total Provincial and Federal Protected Areas | 659 | 9,343,586 | 8.6 | (excluding Algonquin R/U Zone) |

| Provincial park class | Number | Area (ha) | % of Parks | % of ON |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Heritage | 6 | 6,735 | 0.1 | <0.1 |

| Natural Environment | 80 | 1,466,430 | 18.6 | 1.4 |

| Nature Reserve | 109 | 117,935 | 1.5 | 0.1 |

| Recreational | 65 | 37,073 | 0.5 | <0.1 |

| Waterway | 62 | 1,445,416 | 18.3 | 1.3 |

| Wilderness | 8 | 4,823,745 | 61.1 | 4.5 |

| Provincial Park operating status | Number | Area (ha) | % of Parks | % of ON |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-operating | 217 | 4,490,897 | 56.9 | 4.2 |

| Operating | 113 | 3,406,439 | 43.1 | 3.2 |

- All information is current as of August 1, 2009.

- Percentages are based on the official area of Ontario of 107,870,505 hectares.

There are also five national parks in Ontario protected by federal legislation.

In Ontario there are at least 40 additional protected area designations (e.g. ANSI, lands held by Conservation Authorities, the Nature Conservancy, World Heritage sites, etc.). These areas are located on publicly and privately owned lands and waters and provide various levels of protection and use.

National parks

National parks, which are managed by Parks Canada, protect examples of major natural environments that represent Canada’s natural heritage. These parks preserve biodiversity and important wildlife habitat, celebrate the beauty and infinite variety of our land and offer gateways to nature, adventure, discovery and solitude. The five national parks in Ontario also contribute to objectives and targets for provincial protected areas.

Provincial parks

Provincial parks are organized into six classes based upon their purpose. About one third of Ontario’s 330 regulated provincial parks are actively operated to provide recreation opportunities, facilities and services. All provincial parks are planned and managed by MNR to protect natural and cultural values, conserve biodiversity, and support research and monitoring.

Wilderness class parks protect large areas where nature can exist freely. Visitors mostly travel on foot or by canoe and leave little or no impact on the surrounding area. These parks offer unique and challenging wilderness experiences.

Figure 1.2: Ontario’s provincial parks, conservation reserves and wilderness areas (PDF)

Cultural heritage class parks protect elements of Ontario’s distinctive cultural heritage in open space settings. It is important to protect these areas because of their cultural and historical value and to support interpretation, education and research.

Nature reserve class parks protect a variety of ecosystems and provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural heritage including special or rare natural habitats and landforms. These areas are protected for their natural value, to support scientific research and to maintain biodiversity.

Natural environment class parks protect outstanding recreational landscapes, representative ecosystems and provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage. They provide high quality recreational and educational experiences.

Waterway class parks protect recreational water routes and significant terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems with their associated natural and cultural features. These parks provide high quality recreational and educational experiences.

Recreational class parks provide outdoor recreation opportunities in attractive natural surroundings.

Conservation reserves

Conservation reserves protect representative ecosystems, biodiversity and important elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage. They facilitate scientific research and support monitoring of ecological change and provide opportunities for ecologically sustainable, traditional outdoor heritage activities.

Wilderness areas

Wilderness areas preserve land for research and education, protection of plants and animals, and improvement of the area for its historical, aesthetic, scientific or recreational values. There are currently 11 wilderness areas located outside provincial parks and conservation reserves.

International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classification

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has developed a system for classifying protected areas around the world in a consistent manner. Ontario’s provincial parks fall into Categories I, II and III of the IUCN classification system, depending on park class (Table 1.3). An exception is the recreation-utilization portion in Algonquin Park, which does not match any IUCN category.

Conservation reserves are classified as IUCN Category I, II, or III depending upon management prescriptions. Five hundred twenty of Ontario’s 654 protected areas align with IUCN Category II (43 per cent of total land area protected).

| IUCN Category |

Number of areas | Total area (hectares) | Type of protected area | IUCN category1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ia | Strict Nature Reserve | 109 | 117,935 | Nature Reserve Class Park |

| Ib | Wilderness Area | 8 | 4,823,745 | Wilderness Class Park |

| II | National Park | 80 | 871,5702 |

Natural Environment Class Park |

| II | National Park | 62 | 1,445,416 | Waterway Class Park |

| II | National Park | 65 | 37,073 | Recreational Class Park |

| II | National Park | 294 | 1,497,040 | Conservation Reserves |

| II | National Park | 19 | 335,840 | Recommended Protected Areas |

| III | National Monument or Feature | 6 | 6,735 | Cultural Heritage Class Parks |

| III | National Monument or Feature | 11 | 838 | Wilderness Areas |

| IV | Habitat/Species Management Area | |||

| V | Protected Landscape/Seascape | |||

| VI |

Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources Not applicable |

594,860 | Algonquin Provincial Park Recreation/ Utilization Zone |

1.6 Management direction

Planning protected areas is an important role for MNR. Management planning makes sure that legislation and strategic direction are applied to a provincial park or conservation reserve. It also identifies the contribution an individual area makes to the overall protected areas system (Figure 1.3).

Management direction can be a management statement for less complex needs or a management plan for more complex situations. Both documents provide a policy framework for managing issues, natural resources, human activities and capital infrastructure within protected areas.

Management statements and plans provide direction for permitted uses and management activities within a protected area over a 20-year time frame. Management activities include activities to conserve natural and cultural heritage, provide outdoor recreation opportunities, promote heritage appreciation and education, and research and monitoring. Management direction is developed as part of a flexible adaptive management approach that includes planning, implementing, monitoring, evaluating, and adjusting.

| Level number | Planning activities | Level of impact |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 - Direction setting |

|

Broad provincial level |

| Level 2 - Lland use direction |

|

More broad provincial than specific site level |

| Level 3 - Management direction |

|

More specific site level than broad provincial level |

| Level 4 - Implementation & operations |

|

Most specific site level |

The planning process

In 2009, MNR released Ontario’s Protected Areas Planning Manual to guide management planning for provincial parks and conservation reserves.

Two principles guide all aspects of the planning and management of Ontario’s system of protected areas: maintaining ecological integrity and providing meaningful opportunities for consultation. The new manual helps to ensure these principles are integrated into management planning.

The planning and management of provincial parks and conservation reserves must also comply with the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act 1997, Endangered Species Act 2007, Fisheries Act, 1985, Environmental Assessment Act 1990 and other relevant legislation. They are also subject to the Ontario Provincial Park Planning and Management Policies, Conservation Reserve Policy and a variety of other MNR policies, procedures, standards and guidelines.

The management planning process, while it may contain as many as six steps, is really more of a continuous cycle of planning, implementation and improvement (Figure 1.4). For any given process some of the steps may be combined. However, the sequences of steps in the process remain the same. The nature and degree of management documentation and the number of consultation opportunities can change depending on local issues and public concern.

Secondary planning

Secondary plans are prepared for complex issues where more guidance is required. Examples include fire or vegetation management plans, or a more holistic treatment of the environment in an ecosystem management plan. An approved management direction may indicate a secondary plan is needed, or the need might be in response to an unforeseen circumstance. The process of preparing a secondary plan can be coordinated with project evaluation through the Class Environmental Assessment for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves (Class EA-PPCR).

Class environmental assessment

The Class EA-PPCR provides an efficient way to assess management projects based on scale, environmental impacts and level of public concern. Through this process issues, concerns and preferred strategies are identified to ensure that natural, cultural, social and economic values are considered and to reduce negative effects.

Figure 1.4: Protected area planning and management cycle

- Scoping and terms of reference

- Background information

- Management proposals

- Preliminary management direction

- Approved management direction

- Implementation

- Monitoring and assessing management direction

- Adjusting management direction

- Return to scoping and terms of reference

- Adjusting management direction

- Monitoring and assessing management direction

- Implementation

- Approved management direction

- Preliminary management direction

- Management proposals

- Background information

Aboriginal consultation

The Crown has a duty to consult Aboriginal communities where an action or decision could affect established or asserted Aboriginal and treaty rights. This may include development or establishment of new policy, if that policy may affect established or asserted treaty or Aboriginal rights.

Planning for protected areas takes into account the interest and rights of Aboriginal peoples. Aboriginal traditional knowledge is considered in the management direction for protected areas where provided.

Public consultation

Public consultation gives the public the chance to contribute to management planning decisions and MNR the opportunity to communicate its intentions and decisions. Participation ensures that the public’s concerns and aspirations are heard and taken into account. It also helps MNR to show how public input has influenced decisions and to ensure accountability.

The Learning Place interpretive centre at Petroglyphs Provincial Park where First Nations are engaged in park operations.

Chapter 2: Protecting Ontario’s natural diversity

Protected areas are selected and designed based on ecological, geological and cultural heritage features. Areas with the best examples of a feature or condition are rated provincially significant. Areas with next best examples may be considered regionally or locally significant.

Specific targets have been set for representing terrestrial ecosystems, geological features and aspects of Ontario’s cultural heritage. Selecting a site is guided in part by policy commitments based on park class. The selection of park and conservation reserve sites is based on specific criteria, including representation of the best examples of the natural and cultural heritage of the province. A similar framework for representing Ontario’s aquatic ecosystems has yet to be developed.

2.1 Ecological context

Provincial parks and conservation reserves permanently protect ecosystems, biodiversity and important pieces of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage. This is achieved by using an ecosystem approach that sets specific targets for representing natural features and establishing various classes of provincial parks.

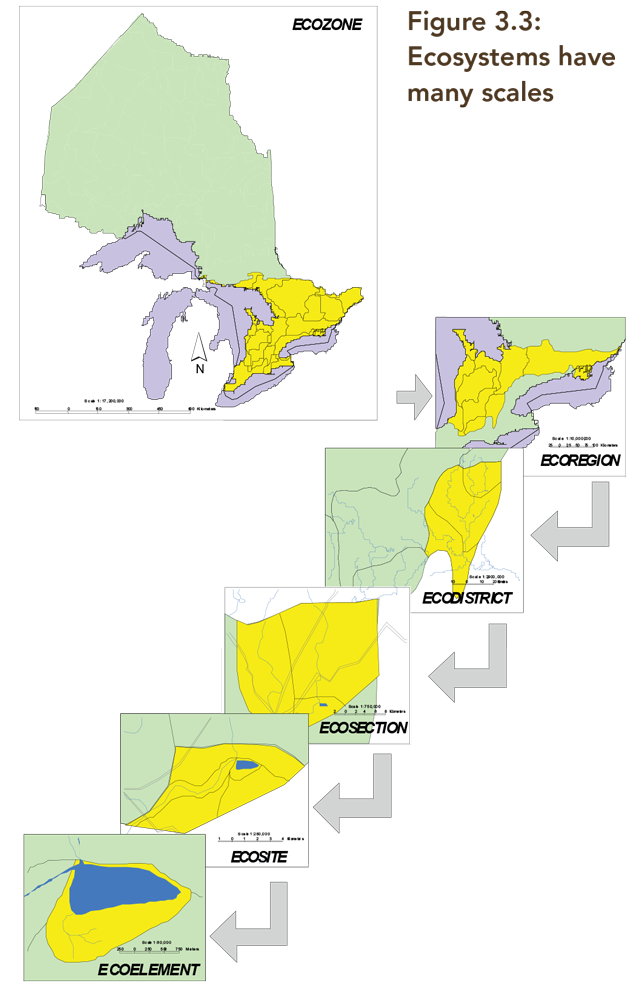

Ontario’s terrestrial ecosystems are organized by a multi- scale ecological land use classification. Factors of this classification system include bedrock geology, climatic variables, surficial geology, physiography and topography. Biological elements (plants and animals) respond to these factors, as well as to soils and microclimate at finer scales.

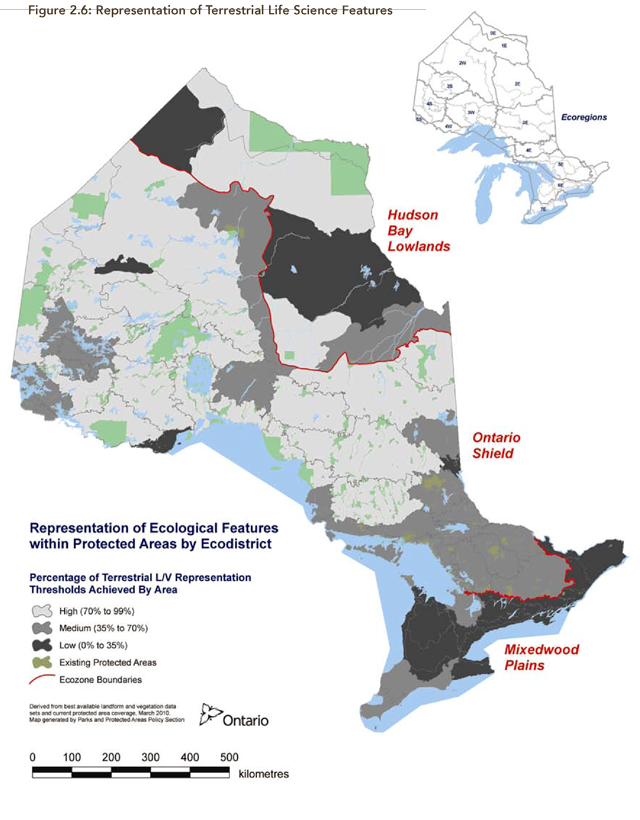

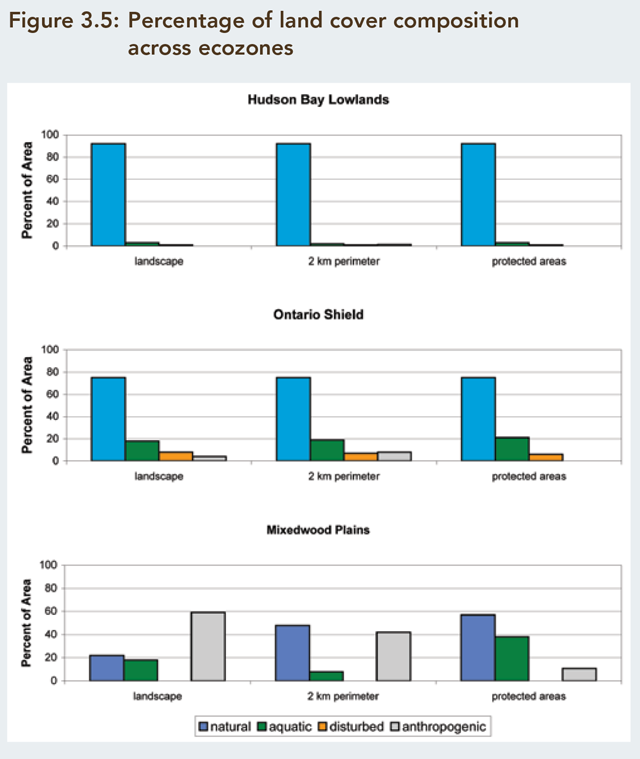

At the broadest level, the ecosystems include the Hudson Bay Lowlands, Ontario Shield, Mixedwood Plains and Great Lakes ecozones (Figure 2.1). These broad ecozones are further divided into 14 ecoregions and 71 ecodistricts.

An individual area’s diversity, integrity, ecological functions and special features also influence its selection as a potential new provincial park, conservation reserve, or ANSI.

Terrestrial ecosystems

Ecozones are large areas of land and water with a distinctive bedrock domain that differs in origin and chemistry from the bedrock domain immediately beside it. The characteristic bedrock, together with long term continental climatic patterns, has a major influence on ecosystem processes and species that live there. Ecozones are resilient to short-term and medium-term change and respond to global or continental cycles operating at thousands to millions of years.

Ecoregions are unique areas of land and water nested within an ecozone that are defined by a characteristic climate range and pattern, including temperature, precipitation and humidity. The climate within an ecoregion has an influence on the vegetation types, soil formations and other ecosystem processes and associated species that live there.

Ecodistricts are areas of land and water contained within an ecoregion that are defined by characteristic physical features, including bedrock and/or surficial geological features and topography. These physical features significantly influence successional pathways, patterns of species associations and habitats. Local climate patterns, such as lake effect snowfall area, characterize ecodistricts.

2.2 Ecozones of Ontario

Hudson Bay Lowlands

Photo: Sam Brinker

The Hudson Bay Lowlands Ecozone encompasses about one quarter the area of Ontario, between the northern edge of the Canadian Shield and the Hudson and James Bay coasts. Existing protected areas make up over 2.4 million hectares, which is about 10 per cent of the total area of the ecozone (Table 2.1).

Sedimentary rocks from the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic eras lie under the Hudson Bay Lowlands. In the last two million years, glaciers laid down sediments and deposited a thin layer of clay and till soils, eskers and lake and marine sediments. More recently, rivers flowing north into Hudson and James Bays have cut deep channels through the bedrock and the surface deposits.

This ecozone includes one of the world’s largest wetlands. Its coastal salt-marshes and mudflats provide important bird nesting areas. Ontario’s only examples of sub-arctic tundra are found near the Hudson Bay coast. The extensive wetlands in the Hudson Bay Lowlands store large amounts of carbon in their soils and provide habitat for several species at risk.

Some of the animals found in this area include woodland caribou, moose, black bear, American marten, sandhill crane, solitary sandpiper, blackpoll warbler, Arctic fox and snow goose. Polar bear inhabit coastal areas during the ice-free period from late spring to early fall. Beluga whale and walrus are often found at the mouths of some rivers and in waters next to the ecozone.

The Hudson Bay Lowlands Ecozone is home to fewer than 5,000 people, most of whom are Aboriginal peoples. Although the coast and waterways are regularly used, most of the landscape is undeveloped. Human activities include hunting, trapping, fishing, tourism, mineral exploration and mining, and some hydro-electric development.

Ontario Shield

Photo: Jake Hojberg

The Ontario Shield Ecozone is located on the Canadian Shield and is Ontario’s largest ecozone. It is bounded by the Hudson Bay Lowlands and the Mixedwood Plains. Protected areas account for 7.1 million hectares, just under 10 per cent of the total area of the ecozone.

This ecozone includes ancient Precambrian rocks and Palaeozoic inliers that have been hardened and shaped by forces of nature for more than a billion years. Glaciers have scraped the Shield’s surface, stripping highlands and filling lowlands with till, silts, sands and gravel. This ecozone is filled with varied landforms including eskers, moraines, abandoned shorelines and aquatic features like countless lakes, rivers, streams, ponds and wetlands.

The Ontario Shield’s vegetation is diverse. Conifer- dominated boreal forests are found in the northern and central part of the ecozone. Mixed and deciduous forests of tolerant hardwoods are found in the southern portion of the ecozone. These forests are interspersed with rivers, lakes, ponds and wetlands, which cover almost one quarter of the ecozone.

Fires occur frequently in some areas of the Canadian Shield. Frequency, intensity and size of burns vary across the ecozone depending on climate, major forest type and local landscape features. Disturbance from wind and insects also determine the composition, structure and dynamics of forest ecosystems.

Woodland caribou, moose, black bear, gray wolf, eastern wolf, Canada lynx, beaver, American marten, red squirrel, barred owl, boreal owl, white-throated sparrow, pileated woodpecker, blue jay and gray jay are just some of the characteristic animals found in the area. Common fish species include walleye, northern pike, smallmouth bass and yellow perch.

The primary work-related and recreational activities in the ecozone are forestry, mining, resource-based tourism, hunting, trapping and angling. There are also many hydro-electric developments.

Mixedwood Plains

Photo: Phil Kor

The Mixedwood Plains Ecozone is Ontario’s smallest and most highly populated. It includes the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Lowlands and the Frontenac Axis, the southernmost extension of the Canadian Shield. Regulated protected areas occupy just over 66,000 hectares, or less than one per cent of the total ecozone area. This figure increases to 3.5 per cent when conservation lands and easements held by Conservation Authorities, Nature Conservancy of Canada, Ducks Unlimited, Ontario Nature and affiliated clubs, Ontario Heritage Trust and member associations of the Ontario Land Trust Alliance are considered.

The ecozone’s underlying bedrock is primarily Palaeozoic age limestone, dolostone, shale and sandstone with outcroppings of Precambrian age granite and marble. The topography includes flat limestone plains, escarpments and deep glacial deposits. The Niagara Escarpment and Oak Ridges Moraine are two of the more well-known landforms in this ecoregion. Other glacial landforms include moraines, spillways, eskers, kames, kettles and drumlins.

The area’s natural vegetation is mostly Great Lakes- St. Lawrence forest characterized by American beech, sugar maple and yellow birch. It also includes the only remnants of Carolinian forests in Canada. The ecozone also supports rare habitats including tallgrass prairies, savannahs and alvars.

This ecozone is the most densely populated area in Canada. Since European contact, many of its natural ecosystems have been converted from forest and wetlands, to human-dominated land uses such as agriculture and settlement.

Despite high rates of conversion of forests and wetlands to agricultural and industrial uses, the Mixedwood Plains is one of the most biologically diverse areas of Canada. Among the characteristic terrestrial species in the ecozone are white-tailed deer, red fox, coyote, raccoon, striped skunk, beaver, eastern gray squirrel, great blue heron, red-tailed hawk, black-capped chickadee, blue jay, American robin, wood thrush, yellow warbler, painted turtle and red-backed salamander. Lakes and rivers here support the highest freshwater fish diversity in Canada. Coastal areas adjacent to the Great Lakes support migrating waterfowl, shorebirds and raptors and provide migration stopover sites for songbirds and monarch butterflies.

About four fifths of Ontario’s species at risk live in the Mixedwood Plains. Invasive species are increasingly problematic, displacing native species and altering structural and functional aspects of natural ecosystems.

| Protected area type/class | Hudson Bay Lowlands No. of protected areas | Hudson Bay Lowlands areas protected (ha) | Ontario Shield No. of protected areas | Ontario Shield areas protected (ha) | Mixedwood plains No. of protected areas | Mixedwood plains areas protected (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural heritage park | 0 | - | 3 | 6,272 | 3 | 463 |

| Natural environment park | 1 | 980 | 63 | 1,441,321 | 19 | 25,391 |

| Nature reserve park | 4 | 74 | 74 | 102,878 | 31 | 11,153 |

| Recreational park | 0 | - | 33 | 31,016 | 32 | 8,465 |

| Waterway park | 5 | 52,360 | 62 | 1,399,909 | 1 | 125 |

| Wilderness park | 2 | 2,358,047 | 7 | 2,466,790 | 0 | - |

| Conservation reserve | 2 | 54,587 | 286 | 1,494,393 | 9 | 2,632 |

| Wilderness area | 2 | 55 | 8 | 744 | 1 | 39 |

| National park | 0 | - | 2 | 190,340 | 3 | 17,820 |

| Total Number/Area Protected |

16 | 2,466,103 | 538 | 7,133,662 | 99 | 66,088 |

| Total Ecozone Area | - | 24,805,210 | - | 68,825,923 | - | 13,926,151 |

| Per cent of Ecozone Protected - 9.9% | - | 9.9% | - | 10.4% | - | 0.5% |

Great Lakes

The Great Lakes are the world’s largest freshwater inland system and hold about 18 per cent of the world’s supply of accessible freshwater.

Geologically, Lakes Huron, Erie and Ontario have a base of glacial till and outwash deposits while Lake Superior flows over volcanic bedrock.

The Great Lakes include about 28,000 km of shoreline (including islands), 5,000 tributaries and 30,000 islands. The islands provide habitat for nesting birds, plants and other land and water species. The variety of depth, climate, location and geological formation all help to sustain a rich diversity of plant and animal species.

The Great Lakes provide a source of water for fisheries, domestic and commercial use. The Great Lakes waterways create a means for transporting commercial goods, recreational opportunities and power for industries.

The Great Lakes were once abundant with native fish species, including deepwater ciscoes, lake herring, lake sturgeon, lake trout and whitefish. Human actions have had an overwhelming impact on the Great Lakes. Aquatic communities have been altered and polluted and now contain many invasive species

In 2007, Canada in co-operation with Ontario, First Nations, local communities and others announced the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area. Once the area is regulated and managed, it will help to conserve natural and cultural values for a significant portion of western Lake Superior and adjacent lands.

Protected areas along the Great Lakes coastline have been assigned to the respective terrestrial ecozones (i.e. Mixedwood Plains or Ontario Shield) for analysis and reporting.

2.3 Provincial park class targets

Ontario’s Provincial Park Policy, which provides the goal, objectives and guiding principles, was approved in 1978. The Ontario Provincial Parks: Planning and Management Policies which guides implementation of Ontario’s Provincial Park Policy was initially approved in 1978 and updated in 1992. That document sets specific targets for the number, size and distribution of wilderness, natural environment and waterway classparks within ecoregions and ecodistricts. Wilderness and natural environment class parks protect large pieces of Ontario’s larger ecosystems. Waterway class parks help to link protected areas.

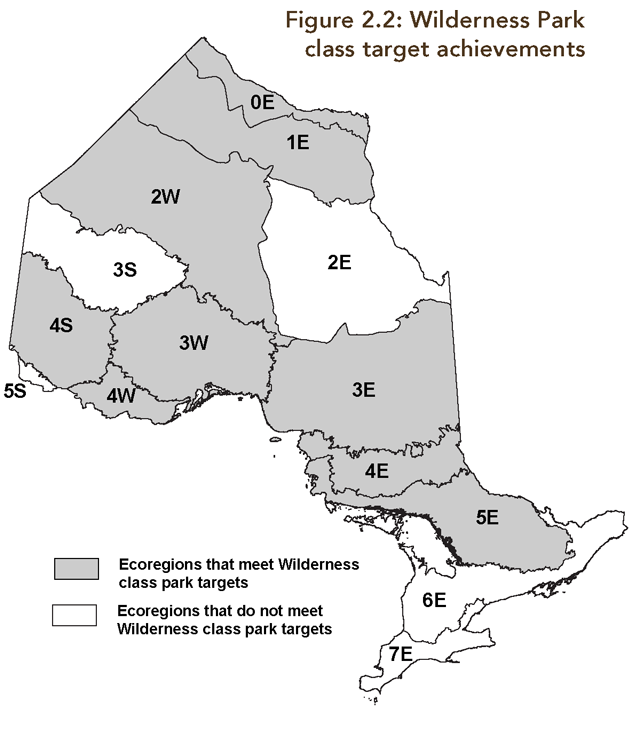

Wilderness class parks

The policy target for wilderness class parks is to establish one park and at least one wilderness zone in each of Ontario’s 14 ecoregions.

In accordance with policy, wilderness parks should average 100,000 hectares and not be less than 50,000 hectares in size. Wilderness zones, in other park classes, should not be less than 2,000 hectares in size and may range up to 50,000 hectares.

Wilderness park class targets have been achieved in nine of 14 ecoregions (Figure 2.2).

Four of 14 ecoregions include wilderness zones established within other classes of park (Figure 2.3).

Opportunities to make new wilderness zones will be looked at while management direction for natural environment and waterway parks is being developed. Since most land in southern Ontario is privately owned and many areas are developed, opportunities to establish wilderness parks are extremely limited. Ontario’s Far North Land Use Planning Initiative may provide additional opportunities to establish wilderness protected areas in northern Ontario.

Natural environment class parks

The policy target for natural environment class parks is to establish one natural environment park, no less than 2,000 hectares, in each of Ontario’s 71 ecodistricts. An equivalent sized natural environment zone within a waterway class park or a wilderness class park containing landscapes representative of the ecodistrict may substitute for a natural environment class park.

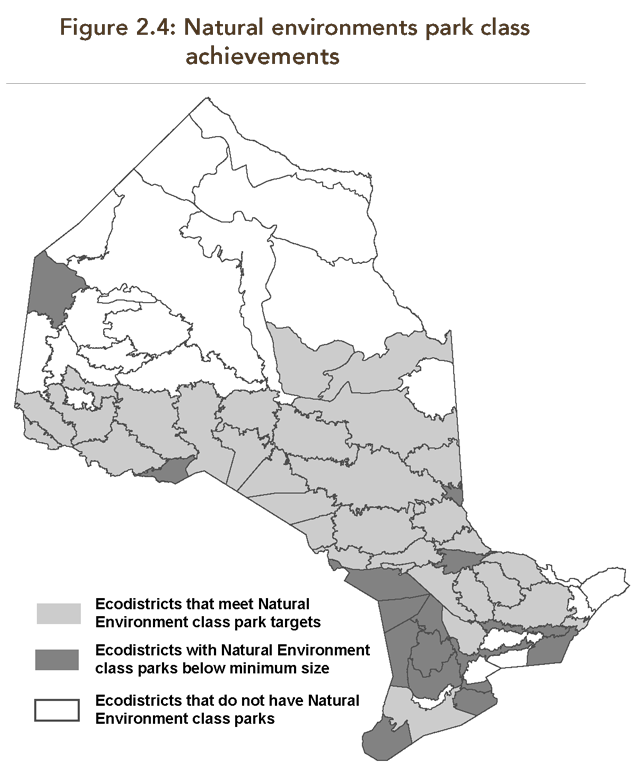

Natural environment class park targets have been achieved in 46 of 71 ecodistricts. Another 13 ecodistricts have natural environment class parks, but fail to meet the minimum size standard. Gaps in target achievement are found in both southern and northern Ontario (Figure 2.4).

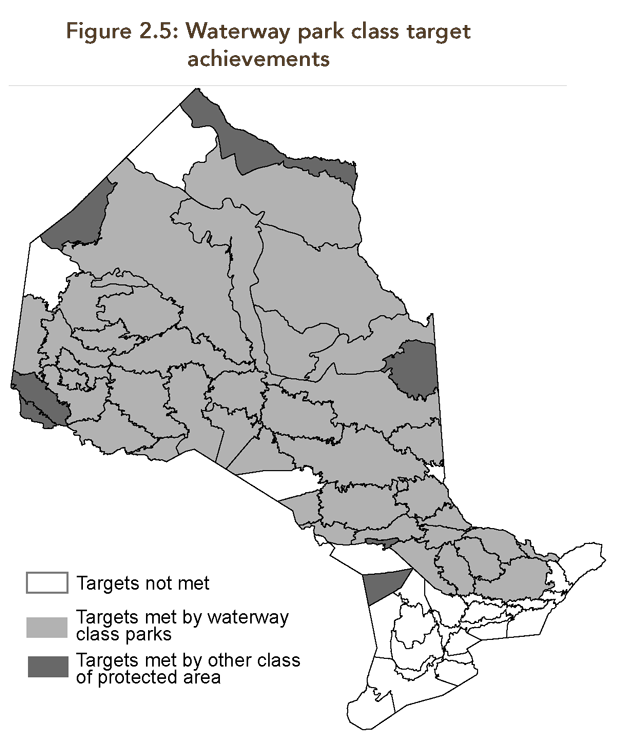

Waterway class parks

The policy target is to establish at least one representative waterway class park, or an equivalent waterway corridor in each of Ontario’s 71 ecodistricts.

Boundaries should be set back at least 200 meters inland from the high-watermarks of the shorelines of lakes and rivers and should take into account lines of sight, proximity of landforms and ecological integrity.

In some cases, it may not be necessary to establish a new waterway park if major waterway corridors are already present within a wilderness or natural environment park.

Waterway class park targets have been achieved in 47 of 71 ecodistricts. Of these, seven ecodistricts are represented by waterway corridors in other park classes (Figure 2.5).

2.4 Representation targets

Representing Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage diversity, as outlined in the PPCRA, is a cornerstone of the protected area system.

Specific selection criteria, which are similar for both life and earth science features (see Sections 2.5 and 2.6, respectively), are used to select protected areas including provincial parks, conservation reserves and ANSI.

Representation targets for provincial parks, conservation reserves and ANSI have been defined by frameworks for geological and biological conservation. These areas are selected to protect Ontario’s most significant natural features, ecosystems and species and to capture representative conditions.

Nature reserve class parks

Nature reserve class provincial parks are particularly focussed on protecting representative geological and biological features. They have the strictest policies of any category of provincial protected areas to ensure the protection of their features.

Cultural heritage class parks

Cultural heritage class parks are selected to protect elements of our cultural heritage. Representation thresholds for cultural heritage class parks are defined by A Topical Organization of Ontario’s History. Cultural heritage parks and historical zones in other classes of parks represent cultural resources. These areas are managed for interpretive, educational and research activities.

Areas of natural and scientific interest (ANSI)

There are two types of ANSI: earth and life science.

Earth science ANSI represent important examples of the bedrock, fossils and landforms in Ontario and include instances of ongoing geological processes.

Life science ANSI represent significant elements of Ontario’s biodiversity and natural landscapes. They contain relatively undisturbed vegetation and landforms and their associated species and communities.

On private lands, MNR informs landowners of the special features on their properties and provides advice and encouragement to help protect and enhance natural values.

MNR encourages other agencies, such as conservation authorities and municipalities to protect ANSI on their lands as well.

The Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program, for example, provides property tax reductions for landowners who voluntarily protect ANSI on their land.

2.5 Life science representation

Ecological selection criteria

Protected areas are chosen because they include examples of the biodiversity of natural regions.

MNR applies five ecological criteria to guide the selection and design of protected areas: representation, condition, diversity, ecological functions and special features (Table 2.2).

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Representation | The full range of Ontario’s natural diversity should be identified and protected. The protected areas system should include representative examples of the biodiversity within ecologically defined regions. Examples of biodiversity that are not adequately represented are identified as a gap in representation. |

| Condition | An underlying principle of the protected area system is to secure the best examples of the full range of the natural heritage of Ontario. The ecological condition of a site helps to determine its significance within the ecodistrict. |

| Diversity | This refers to the heterogeneity of landscapes and species within a proposed site. Sites with a greater variety of physical habitats support a wider array of species and ecosystems. |

| Ecological Function | This addresses the ecological role of a site within the surrounding landscape and watershed, and relates directly to persistence of biodiversity. Hydrologic processes and the size, shape and connectivity among protected areas are of particular importance within this criterion. |

| Special Features | This includes populations of species and vegetation communities known to be rare in Ontario, as well as localized habitat features that are important to their persistence. |

The first two criteria, representation and condition, are applied at a landscape level. They help identify areas that contain features representative of Ontario’s terrestrial biodiversity. The remaining three criteria, diversity, ecological functions and special features, are assessed at a site level. These criteria help to distinguish the best examples of representative features and to design functional protected area boundaries that help protect biodiversity.

Only the two landscape-level criteria are addressed in this report.

Representation thresholds

To represent examples of biodiversity throughout Ontario, MNR has established a minimum threshold of at least one per cent or 50 hectares of each naturally occurring landform/vegetation association within each of the 71 ecodistricts. Natural features that are not adequately represented within protected areas are known as gaps in representation.

Provincial significance

The selection criteria used to choose protected areas, including representation, aims to protect the best examples of Ontario’s nature and biodiversity. This includes natural features, species and ecosystems. These best examples are considered to be provincially significant and may be nationally or internationally significant.

Representation achievement

To analyze representation, MNR uses a tool called GapTool along with current data describing landforms, vegetation, ecodistricts and protected areas. These tools help provide up-to-date reporting on the status of representation and evaluate how potential protected areas contribute to ecological representation.

Minimum thresholds for all naturally-occurring landform/ vegetation associations have not yet been achieved for any ecodistrict in the province (Figure 2.6).

In the Hudson Bay Lowlands Ecozone, nearly all of the area protected is within Polar Bear Provincial Park. As a result, terrestrial biodiversity is well represented in two ecodistricts, but the remaining ecodistricts in that ecozone are almost entirely unrepresented. Additional protected areas in this ecozone (and the northern portion of the Ontario Shield) will be identified through First Nation community-led land use planning as part of the Far North Land Use Planning Initiative.

In the Ontario Shield Ecozone, life science representation in protected areas is better distributed, although some areas are still under-represented. The most commonly under-represented landform/vegetation associations are relatively rare or have potential for high commercial value. Ecodistricts that contain large wilderness or natural environment class parks come closest to meeting minimum representation thresholds.

Almost all landform/vegetation associations in the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone are under-represented in provincial parks and conservation reserves. The highest degree of representation in the Mixedwood Plains has been achieved on Manitoulin Island and the Bruce Peninsula.

Most of the land in the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone is privately owned and therefore could not become regulated protected areas unless purchased or secured by some other method. Including privately owned areas devoted to protection, such as ANSI and those held by the Nature Conservancy of Canada and Ontario Nature, would some- what improve representation, although it would still be very low.

Old growth forest

Old growth is part of a dynamic forest ecosystem. Typically, old growth forest is characterized by:

- A complex forest stand structure (e.g. old trees for the ecosite, large tree size and wide spacing, multiple canopy layers and gaps, and rates of change in species composition),

- Large dead standing trees (snags), accumulations of downed woody material, up-turned stumps, root and soil mounds, and accelerating tree mortality,

- Ecosystem functions (e.g. stand productivity, nutrient cycling and wildlife habitat) that are different from earlier stages of forest development.

The Old Growth Policy for Ontario’s Crown Forests gives two objectives for conserving old growth forest in provincial parks and conservation reserves:

- Identify representative amounts of forest communities that should be present in each ecodistrict within provincial parks and conservation reserves within their natural geographic ranges and allow these protected sites to grow naturally.

- Contribute to the maintenance of red pine and white pine, including old growth stands, by protecting and/ or restoring at least one representative forest stand (ecosite) of old growth red pine and white pine in each ecodistrict in provincial parks and conservation reserves that lie within their natural geographic ranges.

The policy further states that old growth will be assessed as part of the life science gap analysis and that gaps should be filled according to the Ontario’s Living Legacy requirements for the completion of Ontario’s system of natural heritage areas.

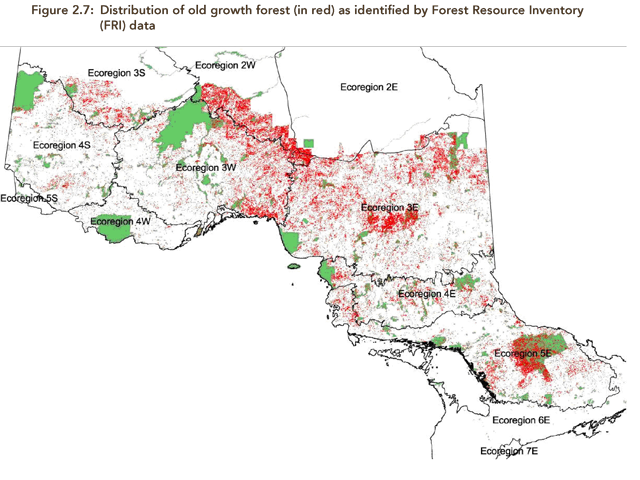

The distribution of old growth forests in Ontario and estimates of old growth conditions in provincial parks and conservation reserves are presented in Table 2.3 and Figure 2.7. These are preliminary estimates based on incomplete Forest Resource Inventory (FRI) data and modelling methodologies.

Very few FRI data are currently available in the Hudson Bay Lowlands Ecozone. In the small area that has FRI data, the dominant forest type is mixed lowland conifers. This area is north of the range for white pine and red pine, and tolerant hardwoods occur only rarely. In this limited area, protected areas have a lower proportion of old growth forest (35 per cent) than the broader landscape (51 per cent).

The Ontario Shield Ecozone contains nearly 99 per cent of the forest that has FRI coverage in the province. Lowland and upland mixed conifer are the dominant forest types. Protected areas contain a greater proportion of old growth forest (20 per cent) than the broader landscape (16 per cent) in every forest type except white birch.

In the small portion of the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone that has FRI data, the dominant forest types are mixed upland conifer and tolerant hardwoods. Overall, 11 per cent of forests in protected areas are in old growth condition, compared to five per cent for the landscape as a whole. Since only a small proportion of protected area forests has FRI data, these conclusions are an estimate.

Table 2.3: Areas of inventoried old growth forest by forest type and ecozone as identified by Forest Resource Inventory (FRI) data

| Forest type | Total forest all (hectares) | Total forest old growth (hectares) | Total forest old growth (%) | Protected area forest all (hectares) | Protected area forest old growth (hectares) | Protected area forest old growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Birch | 146 | 55 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed Lowland Conifers | 131,048 | 71,793 | 55 | 9,780 | 2,486 | 25 |

| Mixed Upland Conifers | 45,661 | 23,116 | 51 | 1,445 | 561 | 39 |

| Mixedwood | 7,468 | 1,281 | 17 | 913 | 208 | 23 |

| Jack Pine | 2,752 | 297 | 11 | 421 | 0 | 0 |

| Poplar and Aspen | 4,769 | 2,071 | 43 | 2,133 | 1,880 | 88 |

| White and Red Pine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tolerant Hardwoods | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 191,858 | 98,613 | 51 | 14,692 | 5,135 | 35 |

| Forest type | Total forest all (hectares) | Total forest old growth (hectares) | Total forest old growth (%) | Protected area forest all (hectares) | Protected area forest old growth (hectares) | Protected area forest old growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Birch | 1,966,690 | 258,682 | 13 | 207,992 | 25,943 | 12 |

| Mixed Lowland Conifers | 6,655,448 | 1,717,706 | 26 | 364,602 | 119,648 | 33 |

| Mixed Upland Conifers | 7,578,056 | 1,672,053 | 22 | 505,988 | 134,165 | 27 |

| Mixedwood | 5,279,177 | 458,475 | 9 | 382,575 | 40,932 | 11 |

| Jack Pine | 4,067,480 | 171,154 | 4 | 257,114 | 17,846 | 7 |

| Poplar and Aspen | 2,836,073 | 368,091 | 13 | 156,140 | 35,481 | 23 |

| White and Red Pine | 1,051,190 | 48,402 | 5 | 148,989 | 14,514 | 10 |

| Tolerant Hardwoods | 2,846,896 | 603,332 | 21 | 207,065 | 54,344 | 26 |

| Total | 32,281,010 | 5,297,895 | 16 | 2,230,465 | 442,873 | 20 |

| Forest type | Total forest all (hectares) | Total forest old growth (hectares) | Total forest old growth (%) | Protected area forest all (hectares) | Protected area forest old growth (hectares) | Protected area forest old growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Birch | 16,256 | 1,422 | 9 | 414 | 92 | 22 |

| Mixed Lowland Conifers | 4,099 | 111 | 3 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed Upland Conifers | 53,969 | 4,535 | 8 | 289 | 29 | 10 |

| Mixedwood | 18,744 | 1,181 | 6 | 122 | 6 | 5 |

| Jack Pine | 447 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 0 | 0 |

| Poplar and Aspen | 11,724 | 536 | 5 | 204 | 0 | 0 |

| White and Red Pine | 12,972 | 49 | 0 | 391 | 0 | 0 |

| Tolerant Hardwoods | 81,690 | 2,949 | 4 | 484 | 39 | 8 |

| Total | 199,901 | 10,783 | 5 | 1,986 | 166 | 8 |

Aquatic representation

Protected areas in Ontario encompass a variety of aquatic habitats. These range from open waters and wetlands on the Great Lakes to inland lakes, rivers, streams and wetlands and finally to tidal marshes, mudflats and open waters of Ontario’s marine coastlines along James and Hudson Bays. These protected aquatic areas account for 6.4 per cent of the aquatic habitat in the province (Table 2.4).

Protected areas can play an important role in maintaining water quality and quantity. The PPCRA has recognized this role by identifying a new aquatic class of provincial parks to be proclaimed at a later date. The objective of this new park class would be to protect representative aquatic ecosystems for their intrinsic and scientific values.

A method of classifying aquatic ecosystems is required to better understand which aquatic values should be protected. An aquatic ecosystem classification system would help us understand and report on freshwater ecosystems. Several aquatic ecosystem classification systems exist, but no system has yet been adopted by the province for planning representation in protected areas.

In 2004, MNR introduced an Ecological Framework for Fisheries Management which takes a landscape, rather than a lake-by-lake approach to fisheries planning, management and monitoring. In 2008, MNR began the Broad-scale Monitoring Program, a long-term effort to monitor the health of lakes and their fisheries across the province, including those within protected areas.

| Aquatic habitat category | Area of habitat category (ha) | Protected area type | Area protected (ha) | % of Habitat category area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water of Hudson – James Bays | 8,667 | Provincial Park | 0 | 0.0 |

| Water of Hudson – James Bays | 8,667 | Conservation Reserve | 0 | 0.0 |

| Water of Hudson – James Bays | 8,667 | Wilderness Area | 2 | <0.1% |

| Water of Hudson – James Bays | 8,667 | All | 2 | <0.1% |

| Intertidal Marsh or Mudflat of Hudson – James Bays | 153,843 | Provincial Park | 31,231 | 20.3 |

| Intertidal Marsh or Mudflat of Hudson – James Bays | 153,843 | Conservation Reserve | 0 | 0.0 |

| Intertidal Marsh or Mudflat of Hudson – James Bays | 153,843 | Wilderness Area | 0 | 0.0 |

| Intertidal Marsh or Mudflat of Hudson – James Bays | 153,843 | All | 31,231 | 20.3 |

| Supertidal Marsh of Hudson- James Bay | 114,939 | Provincial Park | 33,828 | 29.4 |

| Supertidal Marsh of Hudson- James Bay | 114,939 | Conservation Reserve | 0 | 0.0 |

| Supertidal Marsh of Hudson- James Bay | 114,939 | Wilderness Area | 0 | 0.0 |

| Supertidal Marsh of Hudson- James Bay | 114,939 | All | 33,828 | 29.4 |

| Inland Lakes and Rivers | 10,447,311 | Provincial Park | 1,017,626 | 9.7 |

| Inland Lakes and Rivers | 10,447,311 | Conservation Reserve | 91,722 | 0.9 |

| Inland Lakes and Rivers | 10,447,311 | Wilderness Area | 252 | <0.1% |

| Inland Lakes and Rivers | 10,447,311 | National Park | 7,815 | 0.1 |

| Inland Lakes and Rivers | 10,447,311 | All | 1,117,416 | 10.7 |

| Water of Ontario Great Lakes | 8,837,480 | Provincial Park | 68,646 | 0.8 |

| Water of Ontario Great Lakes | 8,837,480 | Conservation Reserve | 3,474 | <0.1% |

| Water of Ontario Great Lakes | 8,837,480 | Wilderness Area | 0 | 0.0 |

| Water of Ontario Great Lakes | 8,837,480 | National Park | 1,563 | <0.1% |

| Water of Ontario Great Lakes | 8,837,480 | All | 73,683 | 0.8 |

| Coastal Wetland of Ontario Great Lakes | 66,896 | Provincial Park | 3,033 | 4.5 |

| Coastal Wetland of Ontario Great Lakes | 66,896 | Conservation Reserve | 1 | <0.1% |

| Coastal Wetland of Ontario Great Lakes | 66,896 | Wilderness Area | 0 | 0.0 |

| Coastal Wetland of Ontario Great Lakes | 66,896 | National Park | 1,325 | 2.0 |

| Coastal Wetland of Ontario Great Lakes | 66,896 | All | 4,359 | 6.5 |

| All Aquatic Components | 19,629,135 | All Protected Areas | 1,260,519 | 6.4 |

Definitions and data sources

- Intertidal Marsh

- Coastal marshes of the Hudson Bay-James Bay Lowlands lying between the coastal mudflats and the supertidal zone. Data Source: MNR Landcover 2000.

- Supertidal Marsh

- Coastal marshes of the Hudson Bay-James Bay Lowlands lying inland of both the coastal mudflats and intertidal marshes, and subject to only exceptionally high tides. Data Source: MNR Landcover 2000.

- Coastal Mudflats

- Unvegetated coastal areas of the Hudson Bay-James Bay Lowlands, partly submerged at high tide. Data Source: MNR Landcover 2000.

- Inland Lakes and Rivers

- Lakes, rivers, streams and creeks within Ontario. All mapped through the Ontario Base Mapping project. Note, this coverage is only comprised of 80 per cent of the province, so hectares are underrepresented. Data Source: MNR Water Segment and Water Line.

- Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands

- A comprehensive Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands Inventory. Built upon the best coastal wetland data currently available and incorporating a standard classification process, the binational inventory provides a standard reference for the Great Lakes wetland community. Data Source: Great Lakes Commission.

2.6 Earth science representation

Some protected areas are selected, designed and managed to conserve earth science features and landscapes for science, education and as a foundation for biodiversity. Identifying representative features helps conserve Ontario’s diverse geological legacy. This has been accomplished by organizing Ontario’s earth science features into 43 distinctive environmental themes related by time, origin and geography.

These 43 themes characterize more than three billion years of geological history. They include the ancient rocks and primitive life forms of the Canadian Shield, the sedimentary rocks and fossils of the Hudson Bay Lowlands and the Great Lakes, and the complex landscapes remaining at the end of the Ice Age glaciation. They also include the dynamic processes that shaped and continue to shape Ontario’s landscapes.

An evaluation called “gap analysis” is used to decide what areas should be protected. This involves describing the earth science diversity of a selected theme, identifying specific protection thresholds and assessing which thresholds have been met within existing protected areas. The resulting “gaps” in representation are then identified and potential protected areas that best illustrate those features are located.

Selection criteria

Earth science gap analysis is guided by five selection criteria: representation, diversity, integrity, special features and life science values (Table 2.5).

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Representation | A feature that best displays its components or make-up and its environments of formation. A representative feature of the geological record can generally be thought of as one that is typical or normal, or one that shows typical elements of the feature. |

| Special Features | Features that include unique aspects of an individual earth science feature or theme or presents exceptional scientific or educational opportunities. Special features may determine the selection of a preferred site. |

| Diversity | This addresses the variability of earth science features at a site. An area is more desirable when it incorporates a variety of features within a relatively small area. |

| Integrity | This refers to the completeness or condition of the feature within the site and the degree of human-induced impacts on them. This is most applicable to landforms. |

| Life Science Values | This is a consideration when comparing sites with similar earth science features and is most relevant to landscape sites large enough to support significant vegetation stands or communities. |

Representation achievement

Our understanding of Ontario’s geological history and diversity continues to evolve. In addition, an inventory of geological features within recent protected areas identified in Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Plan is still underway. Therefore, the current assessment of earth science representation is not entirely complete and the estimates are conservative.

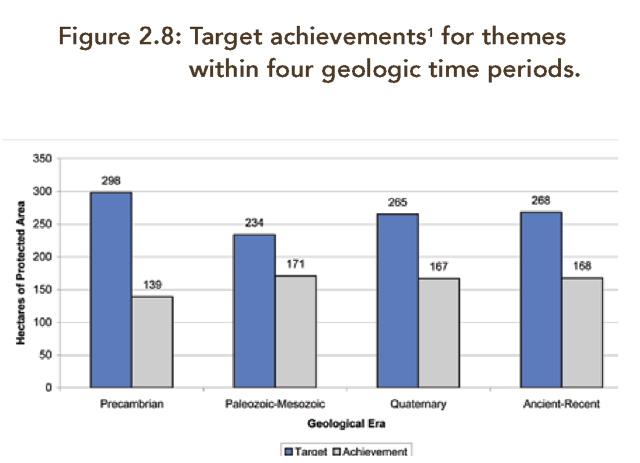

A broad analysis of protected areas using Geology of Ontario maps shows that the identification of Precambrian targets may be close to being complete. Based on this analysis, about 47 per cent of Precambrian earth science representation thresholds have been achieved in protected areas (Figure 2.8). Work is now underway to update Precambrian feature and theme targets, record new information and complete inventories.

About 73 per cent of the representation thresholds for Palaeozoic – Mesozoic geological themes have been achieved. The features associated with these themes include natural outcroppings of bedrock and fossils along rivers, lakes, escarpments and disturbed areas near roads and quarries where they are exposed. ANSI play a significant role in the protection of many of these features.

Overall about 63 per cent of the representation thresholds for Quaternary geological themes have been achieved.

The features of these themes include small outcrops and landforms, large landform complexes and expansive glaciated landscapes. In southern Ontario, ANSI again play a significant role in protecting these features.

There are eight Ancient and Recent Landform themes based upon the classification of geological environments. About 63 per cent of their representation thresholds have been achieved.

2.7 Cultural heritage representation

Ontario’s prehistory reaches back some 13,000 years when the first people migrated northward at the foot of the retreating continental glaciers. A rich archaeological record traces these early settlers, their tools, pottery, trade routes and agricultural achievements. Written history describes the first contact between Aboriginal peoples and Europeans and tells the stories of early fur traders, homesteaders, loggers and miners. It also records the building of railroads, military engagements and provincial politics.

Cultural heritage representation helps identify and protect Ontario’s archaeological and historical features. This is done by organizing historical activities and development, including Aboriginal and European settlement into themes. This topical organization includes 13 themes; each based upon a distinct phase of activity such as mining, logging, fur trading and agriculture and linked to a certain time and place in Ontario’s history (Table 2.6). These themes are further divided into 115 theme segments to reflect the involvement of part of the population in a specific region.

While a comprehensive evaluation has not been completed, more than one third of historical themes and theme segments are found in provincial parks. The Ministry of Culture is developing new standards and guidelines to evaluate provincial properties, including provincial parks and conservation reserves.

| Conceptual area | Historical theme | Theme period | No. of theme segments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic and Social | early post-glacial immigrants | 11,000 BC – 5,500 BC | 2 |

| Economic and Social | environmental frontiersmen | 5,500 BC – 200 BC | 2 |

| Economic and Social | indigenous settlers, traders and potters | 1,000 BC – 500 AD | 4 |

| Economic and Social | indigenous peoples’ farming societies | 500 AD – 1600 AD | 4 |

| Economic and Social | northern hunters and anglers | 800 AD – European contact | 4 |

| Economic and Social | post-contact tribes and bands | 1560 – early 19th Century | 6 |

| Economic and Social | fur trade and fur trading communities | 1615 – 1930s | 16 |

| Economic and Social | agriculture and agricultural communities | 1749 – present | 22 |

| Economic and Social | forest industry and forest industry communities | 1809 – present | 16 |

| Economic and Social | mining and mining communities | 1799 – present | 17 |

| Economic and Social | transportation and integration of economies and communities | 1790s – present | 12 |

| Military | military | 1100 - 1871 | 5 |

| Political | political | 1615 - present | 5 |

2.8 Growing protected areas

Interest in protected areas to help stem the loss of natural heritage and biodiversity continues to grow worldwide. Commitments to protect additional areas have been expressed in the United Nations and Canada’s Conventions on Biodiversity. Public opinion polls repeatedly show that Canadians strongly support the creation of a healthy system of protected areas.

Land use decisions made to create new protected areas are often complex. They can provide economic opportunities, while constraining some traditional uses and future development. Landowners, resource users, Aboriginal peoples and resource sector industries may hold different or conflicting views about protected areas. Conservation planning and Aboriginal traditional knowledge can resolve issues and guide decision making.

The protection of Ontario’s natural diversity and cultural heritage is a great responsibility that cannot be achieved by government alone.

Partnering in science

MNR participates in a variety of scientific efforts to choose the best areas for biodiversity protection. For example, the Great Lakes Conservation Blueprint (2005) undertaken jointly by the Nature Conservancy of Canada and MNR, has provided valuable information to assist systematic conservation planning and to inform a priority listing of areas for future acquisition.

Ontario Parks is a founding member of the Centre for Applied Science in Ontario’s Protected Areas (CASIOPA) and its forerunner, the Parks Research Forum of Ontario. The centre is a research association led by the University of Waterloo, Parks Canada and MNR, with advice from several universities and non-governmental organizations. It provides science-based workshops and networking opportunities. It also facilitates social, natural and physical research in support of protected areas management and land use planning. The transfer of knowledge gained from these activities has been most beneficial to systematic conservation planning.

Partnering in Conservation

Particularly in more populated areas, a variety of creative approaches, including partnerships and private land stewardship, are necessary to help protect Ontario’s biodiversity. It is important for government to work closely with local communities, individuals, businesses, Aboriginal peoples, conservation organizations and others to create a better system of protected areas.

Photo: Phil Kor

Since 1970, MNR and the Nature Conservancy of Canada have worked closely with partners and donors to secure natural areas. In 1996, a formal partnership called Legacy 2000 was established to secure examples of Ontario’s natural diversity. Between 1996 and 2006, this partnership secured more than 17,000 hectares of ecologically significant land valued at more than $20 million.

In 2006, MNR and the Nature Conservancy entered into a new partnership to secure private lands. As part of the Greenlands agreement, MNR, along with other funding sources such as a Canada-Ontario Agreement Respecting the Great Lakes Ecosystem Basin, provides funds to acquire privately owned lands. The Nature Conservancy provides expertise to secure and steward new areas. MNR assesses the natural values of potential properties based on ecological and geological selection criteria and informed by the Great Lakes Conservation Blueprint and other scientific efforts. Under this new partnership agreement, more than 200 hectares of ecologically significant land valued at nearly $0.9 million has been secured and added to the protected area system since 2006.

MNR also secures land through donations and government funding. Since 2006, 17 hectares of high priority conservation lands valued at more than $1.3 million have been added to the protected areas system in this way.

MNR continues to conserve biodiversity and ecologically sensitive lands in the southern landscape, working with others to secure lands through purchase, long-term lease, conservation easements and donations. MNR participates in strategic initiatives such as the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area, Algonquin to Adirondacks, Heart of the Continent and Greenways Strategy. Heart of the Continent, for exam ple, is a partnership between Ontario and Minnesota to improve protected area coordination in the Quetico Provincial Park – Boundary Waters Area.

Photo: Chris Martin

MNR also continues to support the efforts of municipalities and conservation authorities in protecting natural heritage through zoning and land management practices.

In the central part of Ontario licensed for forest management, the 1999 Ontario’s Living Legacy Land Use Strategy and the related Ontario Forest Accord provide a framework to create new provincial parks and conservation reserves. The Ontario Forest Accord is an agreement between government, the forest industry and non-government organizations that supports the growth of the protected area system beyond the 12 per cent level achieved in the land use strategy.

In 2003, Pikangikum First Nation, in partnership with MNR, began a community-based land use planning initiative. Pikangikum Elders provided guidance and indigenous knowledge throughout the process. Keeping the Land – The Whitefeather Forest Land Use Strategy dedicated over 400,000 hectares of spectacular landscape and 400 kilometres of culturally significant waterways to the Ontario protected area system. These areas will be managed through a new partnership arrangement between Pikangikum First Nation and MNR.

In October 2009, the Ontario government and Pikangikum First Nation celebrated their partnership by signing a terms of reference that will support protected areas and forest management planning in the Whitefeather Forest.

| Category | Number of Sites | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| newly regulated conservation reserves | 45 | 450,156 |

| newly regulated provincial parks | 14 | 52,384 |

| additions to existing provincial parks | 16 | 169,677 |

| Totals | 75 | 672,217 |

Except for Keeping the Land – Whitefeather Forest Land Use Strategy, systematic conservation (land use) planning in the Far North of Ontario has not yet occurred. Some ecodistricts in the Hudson Bay Lowlands and northern boreal region have no protected areas. Ontario’s Far North Land Use Planning Initiative represents an opportunity to for First Nations and Ontario to work together to create a new protected area framework that will result in the protection of at least 225,000 square kilometres of the Far North, while allowing for areas of sustainable economic development.

Photo: Lee Gerrish

The Far North Act will enable a community-based land use planning process that provides First Nations a leadership role in determining areas to be protected. Both Aboriginal traditional knowledge and western science will make essential contributions to these plans. MNR is currently conducting surveys of biodiversity including woodland caribou and other natural values in co-operation with Far North First Nations.

Regulating new protected areas

New protected areas that are identified through land use planning or secured for the purposes of protection may be regulated under the PPCRA. The regulation process involves consultation with affected landowners, detailed mapping and public notification. During 2005-2009, MNR regulated 59 new provincial parks and conservation reserves, and also regulated 16 additions to existing provincial parks (Table 2.7).

In the Far North, as new areas are identified for protection through community based land use plans, the protected areas may be designated under the Far North Act or the First Nations and Ontario may decide together to have the areas regulated through the Far North Act or the PPCRA.

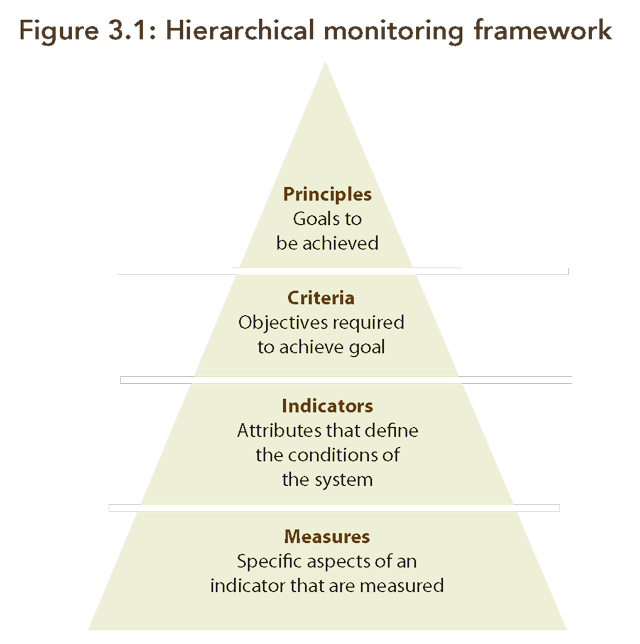

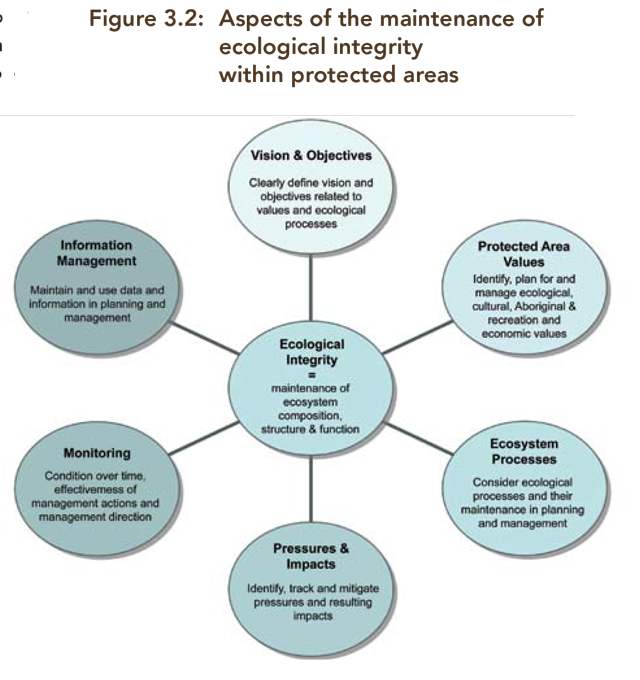

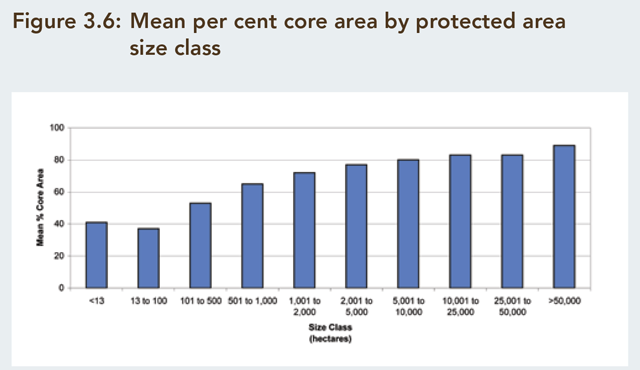

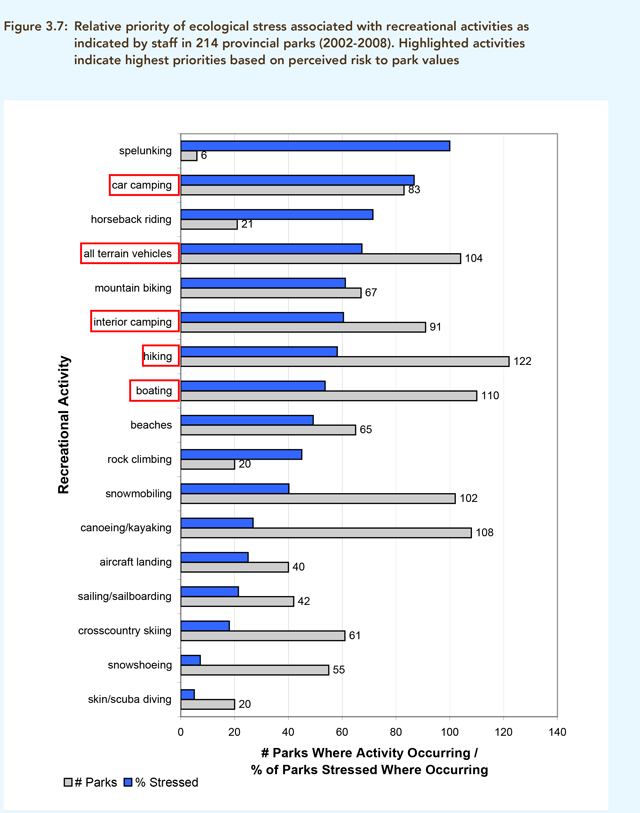

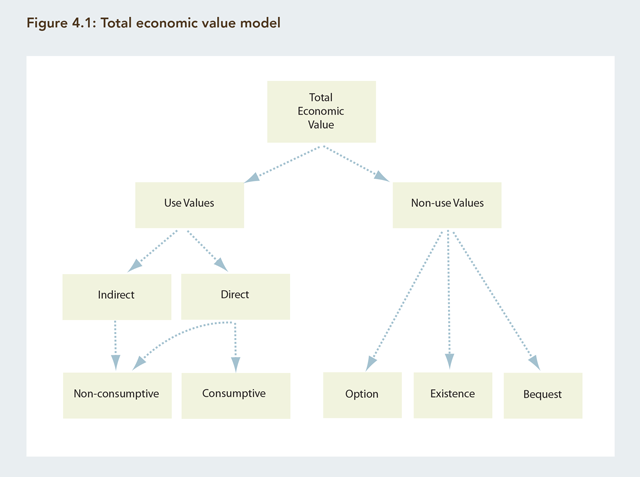

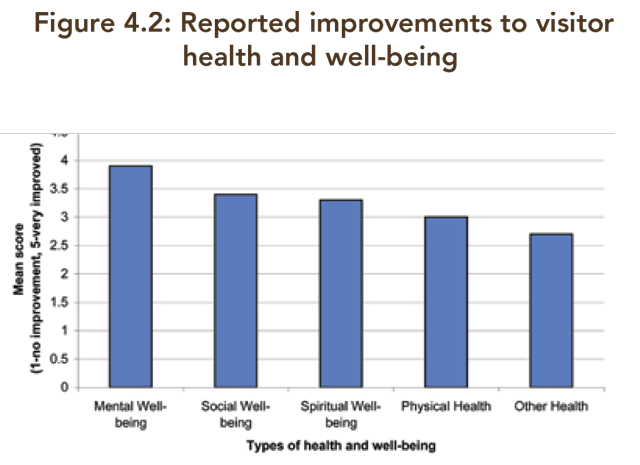

Chapter 3: Ecological integrity