Bait management review

(MNR 62713)

(ISBN 978-1-4435-9695-4)

Preface

This document has been prepared to assemble information on the live bait industry in Ontario prior to a policy review of live bait management in the province. Various types of live bait are described and the feasibility of aquaculture for different bait species is investigated. Licence sales, reported harvests, and economics are provided for the Ontario bait industry. Management of the Ontario bait industry is reviewed. Results of a North American jurisdictional scan on bait policies and management practices are presented. Finally, problems and issues currently facing the bait industry are identified. An emphasis has been placed on ecological issues associated with the use of live bait. More than 370 citations have been provided as additional reference material.

It is hoped that this report will serve as a useful reference document for both internal and external committees who will be involved in the development of a new provincial bait policy.

Steven J. Kerr

Fisheries Policy Section

Biodiversity Branch

June 2012

Background

Angler use of bait

Bait may generally be defined as any substance used to attract and catch fish. The use of live organisms as bait has traditionally been popular among anglers. The type of bait used often varies with the species of fish being sought (Lowry et al. 2006). Surveys indicate that nearly 80% of Ontario anglers use live bait, mostly worms and baitfish, with a small percentage using frogs and crayfish (OMNR 2006). Leeches are used by approximately 20% of anglers.

In Ontario, anglers have the option of either harvesting their own bait or purchasing bait from a retailer. Prior to the implementation of a resident angling licence in 1987, resident anglers could use bait traps and dip nets without a permit but were required to obtain a permit to use a seine net. Currently, under authority of an angling licence, resident anglers can use one bait trap or dip net to harvest baitfish for personal use. It is illegal for anglers to sell their baitfish. In the 2005 recreational angler survey, the second-most popular bait/tackle was found to be live baitfish (54% of anglers) (OMNR 2009a). The survey also indicated that approximately 3% of anglers harvest bait for their personal use. Anglers are restricted to a limit of 120 baitfish in their possession at any time.

Figure 1. In Ontario, licensed resident anglers are allowed to either capture their own bait or purchase bait from a commercial bait dealer (Brenda Koenig photo).

Types of bait

Types of bait used for recreational angling includes species of crayfish, fish, frogs, leeches, and earthworms. The regulated bait industry in Ontario applies only to fish and leeches however.

Crayfish

There are 9 species of crayfish in Ontario (BAO and OMNR 2005b). Seven of these species are native and two have been introduced from the United States (Hamr 1997).

Anglers may harvest their own crayfish and the limit is 36 per person. When compared to baitfish, crayfish comprised only a small portion of the Ontario live bait industry (Brousseau 2002). The commercial harvest and sale of crayfish was prohibited in 2007. At that time, crayfish represented only a small (<0.03%) proportion of the live bait industry.

In Ontario, crayfish are harvested almost exclusively by baited minnow traps using cut fish parts or commercial pet food. Crayfish are most active at temperatures between 15-20°C. Momot (1991) concluded that, as long as habitat remained intact, removal of up to 50% of the population was possible without any danger of growth or recruitment over- fishing. As long as their body and gill chambers are kept damp, crayfish can live out of the water for extended periods of time and can survive transport over long distances (Huner 1997). In Ontario, however, crayfish can only be used in the waterbody from which they were captured. Crayfish, whether dead or alive, cannot be moved overland.

Fish

Although many species of fish may be suitable as live bait for angling, there are only 48 species designated as baitfish for the purpose of harvest and sale in Ontario (see Appendix 1). This listing is based on species which are native to Ontario. In actuality, the bulk of the baitfish harvest and sales consists primarily of only 10-11 different species.

Figure 2. Baitfish are the most common type of live bait used by anglers in Ontario. (Brenda Koenig photo).

A number of factors ultimately determine the capability of a waterbody to produce baitfish (Table 1).

Table 1 [reproduced as a list]. Characteristics of a good baitfish lake or pond (from Hildebrand-Young Associates Ltd. 1981 and Eddy 2000).

- Simple fish community with an absence of predatory game fish species.

- Relatively shallow and constant depth of water with some deeper (e.g., 3-4 m) overwintering areas.

- High levels of dissolved oxygen throughout the year.

- Small surface area .

- Brushy shoreline with deadfalls and beaver lodges.

- Presence of inlet and outlet streams which may serve as spawning habitat.

- Soft substrate (e.g., mud).

- Abundance of submerged aquatic vegetation.

- Presence of broken rock substrate along lake shoreline

Harvest equipment for baitfish includes traps, dip nets, and seine nets. Traps are usually baited except perhaps during spring runs in creeks (Winterton 2005). Fish are often sorted (by species) and graded (by size) before being moved to some form of holding tank. Seining is another preferred means of capture for species such as shiners which are a schooling fish. The use of seine nets is usually restricted to areas which have substrate free of obstructions. Since seine nets usually capture more fish than a baited minnow trap, there is often more time and effort required to sort and grade fish at the site.

Sales of baitfish in the winter are usually comprised of species such as emerald shiner (Notropis atherinoides), common shiner (Luxilus cornutus), and spottail shiner (Notropis hudsonius), which are captured in large numbers during their fall movements. During the summer, the most common baitfish are species of dace (Rhinichthys, Phoxinus and Margariscus spp.), fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas), common shiner, suckers (Catostomus spp.), and chubs (Semotilus, Nocomis and Couesius spp.). Emerald shiners are seldom available in the summer since they do not survive well in warmer water.

There has been some experimentation with alternate gear types for harvesting baitfish. Mohr (1985) experimented with the use of small mesh trap nets and found them to be a viable alternative to minnow traps under certain conditions and in certain lakes.

Historically, large volumes of baitfish (primarily emerald shiners), harvested from Lakes Erie and Simcoe, were transported long distances to markets as far away as Cochrane and Thunder Bay.

Frogs

There are thirteen species of frogs which are native to Ontario. Frogs are widely used as bait predominantly by bass anglers.

Both active and passive techniques are used to harvest frogs. Frogs are often subject to stress during transport (Winterton 2005). At all times they need to be kept cool and moist.

Prior to 2001, anyone could harvest and sell frogs without a licence. In 2001, regulations were introduced which:

- Allowed commercial bait licence holders to harvest and sell only northern leopard frogs (Rana pipiens).

- Restricted the harvest of frogs to several designated counties in southeastern Ontario.

- Permitted an individual harvesting frogs under authority of a sport fishing licence to catch and possess up to 12 northern leopard frogs and one specimen of any other frog species that was not specially protected.

Based on a 2002 survey (Brousseau et al. 2003), almost 7,000 dozen frogs, valued at over $46,000, were harvested from southern Ontario.

The commercialization of bull frogs (Rana catesbeiana) was stopped in Ontario based on concerns about their population status. In response to concerns about the decline in other Ontario frog populations (Shirose 2000), the commercial harvest and sale of frogs was prohibited in 2007. At that time, frogs accounted for only a small portion (< 0.02%) of the live bait industry. Anglers are still allowed to harvest northern leopard frogs for personal use. The limit is 12 frogs per person.

Leeches

There are believed to be 35 species of leeches in Ontario (Walther-Landon 1986). The primary species used as bait is the ribbon leech (Nephelopsis obscura). Due to the difficulty in identification, most anglers and bait dealers are unable to identify the species of leech being used or sold.

Figure 3. Leeches are a bait preferred by many walleye anglers (Brenda Koenig photo).

Leeches are found in a diversity of habitats and can tolerate a wide range of water quality parameters (Walther-Landon 1986). Peterson (1982) found that productive ponds for leeches were situated near agricultural lands, supported green algae blooms, and contained few fish species. Until the early 1980s, leeches were seldom used for angling (Winterton 1998a). Today, leeches are a bait especially preferred by many walleye anglers. Leeches are sensitive to temperature and are most effective when angling in cool (i.e., 15° C) waters. The demand for leeches increased greatly in the late 1980s and 1990s. The increased demand for leeches resulted in increased importation.

Leeches are harvested with baited traps set in warm, shallow areas of ponds and lakes. Since leeches are nocturnal, traps are set in the evening and checked in early morning. Leeches can be held for periods of 8-10 weeks while being transported to market. Proper handling techniques and maintenance of good water quality are required to minimize holding mortality (Friesen 2000). They can be sold either by the dozen or by the pound. Anglers may harvest their own leeches but are restricted to a maximum of 120 leeches per person regardless of whether they were harvested or purchased from a commercial dealer.

Historically, many American anglers brought leeches into Ontario from the United States (Walther-Landon 1986). It has been estimated that 50-60% of the leeches used by anglers in Ontario originated from outside the province (Friesen 2000). This practice was discontinued in 1999 when anglers were banned from importing leeches into Ontario. By 2005 the ban had been extended to commercial operators.

Earthworms

Records of anglers using earthworms to catch fish date back to the 15th century (Anonymous 1962). Although no native earthworms exist in Ontario, there are a total of at least 19 species which are currently found in the province (Evers et al. 2012). Earthworms are a very popular and widely-used bait. They are marketed under a variety of names including angle worms, leaf worms, night crawlers, dilly worms, and wigglers (Keller et al. 2007). The dew worm or night crawler (Lumbricus terrestris) is probably one of the most widely used earthworms sold commercially. Other species of earthworms may be used by anglers who collect their own bait. There are currently no restrictions regarding the harvest or sale of earthworms in Ontario.

Other types of bait

Several other invertebrates are less commonly used as bait by anglers. This includes caterpillars, crickets, garden slugs, grasshoppers, grubs, maggots, and wax worms. None of these products are currently regulated in Ontario. Salamanders cannot be used as bait in Ontario.

Some trout and salmon anglers utilize salted roe (spawn) as bait. The sale of roe is regulated under the provincial Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act. Roe may not be sold under authority of a commercial bait licence or by an angler.

Propagation of bait

As a general rule, propagation is considered to be the artificial rearing of gametes obtained either from a wild or domesticated source. Propagation may either be intensive or extensive in nature. Intensive propagation occurs when fish are reared at high densities under controlled environmental conditions. Conversely, extensive propagation is when fish are reared at lower densities when environmental conditions cannot be controlled.

In Michigan and Wisconsin, cultured baitfish accounts for approximately one-third of all baitfish sales (Busiahn 1996), Although the culture of bait species is a well developed industry in the United States, there are few operations in Canada. Golden shiners (Notropis crysoleucas), white suckers (Catastomus commersonii), creek chub (Semotilus atromaculatus) and fathead minnows are the most common baitfish species which have been cultured in the United States (Hedges and Ball 1953, Stone et al. 1997).

Suckers are often reared intensively in a hatchery environment after wild egg collections. Fry are then subsequently transferred to ponds. Conversely, the propagation of fathead minnows and golden shiners usually involves the release of adult brood fish into ponds where they are allowed to spawn naturally. In some instances the brood fish are removed after spawning so as not to compete with their progeny (Davis 1993). Fish are harvested from the ponds once they have achieved the desired size.

Brubacher (1962) concluded that competition from wild supplies, high capital investments, and a relatively short growing season, made the commercial propagation of baitfish in Ontario difficult. As a result, there have only been a few attempts to culture baitfish in Ontario over the years. In 1967, an experimental project was conducted in the Kenora District to rear suckers to meet baitfish supply shortfalls in the summer (Saunders 1967). A wild spawn collection was conducted in the spring. Eighty percent of the eggs hatched and approximately 104,000 fry were introduced into a rearing pond within 48 hours after hatching. The rearing pond was drained and seined in early November to determine sucker production. It was estimated that 30% of the sucker were of marketable size in early August and the remainder would have been marketable in late August or early September. In 1969, a total of 130,000 eggs were collected, hatched and the sac fry were placed in two artificially constructed ponds on the Matachewan Indian Reserve (Atkinson 1969). The goal of the project was to raise baitfish to sell to retailers. Unfortunately, the results of the project were not reported.

Probably the most intensive experimentation with regard to baitfish culture in Ontario occurred at the provincial Westport Fish Culture Station in the late 1960s. The project was designed to evaluate the feasibility and economics of rearing golden shiners. Over a three year (1968-1970) period, various ponds were used as spawning and rearing areas. Problems which were encountered included heavy mortality when moving shiner fry, unwanted algae and aquatic vegetation, predation, parasite infestation, and a short growing season. It was concluded that the profit margin was too low for the propagation of golden shiners (McNee 1971).

Leeches can be cultured in hatcheries or in ponds. Ponds need to be fertile and relatively free of fish. Under good conditions, leeches can be grown to market size in 9-10 weeks. In Minnesota, Collins et al. (1983) concluded that commercial leech production was cost competitive with natural harvest costs. Stocking juvenile leeches into commercial harvested ponds or lakes to supplement natural populations has not been found to be a practical management tool (Peterson and Hennagir 1980a, Peterson 1982).

It is possible to propagate some species of frogs. Propagation techniques can range from stocking ponds with tadpoles (extensive culture) to intensive culture in outdoor pens. Sanitation problems have frequently been encountered in frog propagation operations.

Crayfish are cultured in the southern United States (e.g., Louisiana). They are usually reared in small ponds (Forney 1957). Ponds are stocked in the fall or the spring with mature (fall) or egg carrying (spring) crayfish that mate and expel their eggs. Young crayfish reach bait size by July and are removed by seining (Brown and Gunderson 1997) or the use of baited traps (Bardach et al. 1972). The expense and length of harvest period are problems which are commonly experienced in crayfish culture (de la Bretonne and Romair 1990). In northern climates, crayfish display slow growth, reduced juvenile survival rates and a long lifespan. Momot (1991) concluded that these characteristics were counterproductive for commercial aquaculture.

Earthworms can be reared relatively easily in large containers filled with peat, sawdust, sand and other organic material. Moisture content of the bed is a critical factor. High fibre content food is often used to promote growth. Worms can first be harvested from new beds after 3 months and then harvested every 2-4 weeks thereafter (Masson et al. 1992).

There are several advantages for the propagation of bait to supplement wild harvest (Markus 1934, Burtle undated). Under controlled rearing conditions the possibility of transferring disease or exotic species is minimized (Goodwin 2012). Potential overharvest of wild bait stocks could be avoided. Finally, artificial propagation could serve to provide a stable source of bait throughout the year. If wild stocks of bait decrease and wholesale prices increase, the economic feasibility of bait culture in Ontario becomes more attractive (Winterton 2005).

Managing Ontario’s bait industry

Some of the earliest baitfish records date back to 1925 when a total of 99 licences were issued provincially (Goodchild 1997). At that time the capture and sale of live bait was generally considered to be a means of supplementary income for children and others (Brubacher 1962). Initially, the harvest and sale of bait was a localized affair since holding and transporting facilities were inadequate (McNee 1966). The baitfish industry in southern Ontario expanded considerably between 1930 and 1960 (Appendix 2).

The live bait industry in northern Ontario developed later than in the south. The baitfish industry in northwestern Ontario commenced in the 1950s (Hilldebrand-Young Associates Ltd. 1981). Licensed areas on Crown land were poorly defined resulting in many conflicts among harvesters. A licence was required to harvest baitfish but there was no annual reporting requirement.

Historically, the live bait industry was comprised of harvesters, dealers, preservers and importers. A harvester was an individual who was licensed to harvest live bait from a designated area using harvest equipment specified on the licence. Most harvesters sold the majority of their bait to retailers. A bait dealer was an individual who was licensed to sell bait to anglers. They were required to have a baitfish dealers licence to possess, transport, and sell. A preserver licence allowed for the preserving of bait by freezing, salting, or pickling. Surplus supplies of bait which could not be held were often processed in that fashion. The maximum weight of bait which could be processed annually was limited by regulation. Importers were individuals who could import bait from aquaculturists in the United States in order to alleviate bait shortages during the summer months.

In the early 1960s an angler was allowed to catch (by trap or dip net) and hold up to 50 baitfish without a licence (Brubacher 1962). By the mid 1960s, two different licensing systems were in use. In much of southern Ontario, harvesters were assigned specific waters for their use. Conversely, in northern Ontario, bait harvesters were assigned a defined “block” containing multiple waters. For the most part, only one harvester was allowed in any block. There are some exceptions to the block system. For example, in Lake Erie the baitfish resources are allocated to multiple users fishing the same areas.

In 1965, Payne (1965) reviewed the status of the baitfish industry and called for regulations which would meet market demands while preventing wild stocks from being overexploited.

By the 1970s, concerns were emerging about potential overexploitation of baitfish, particularly in southern Ontario. This prompted the formation of a Central Region baitfish subcommittee within OMNR and implementation of several policies intended to prevent overharvest. These policies included:

- Only one licence would be issued to the harvester – the licence was required to be on his person – no duplicate licenses were allowed.

- The amount of gear licensed was limited to one seine net, one dip net and an unlimited number of minnow traps.

- A harvesters licence was only issued to the holder of a licence from the previous year. Licensees who had not fished the previous two years were not renewed.

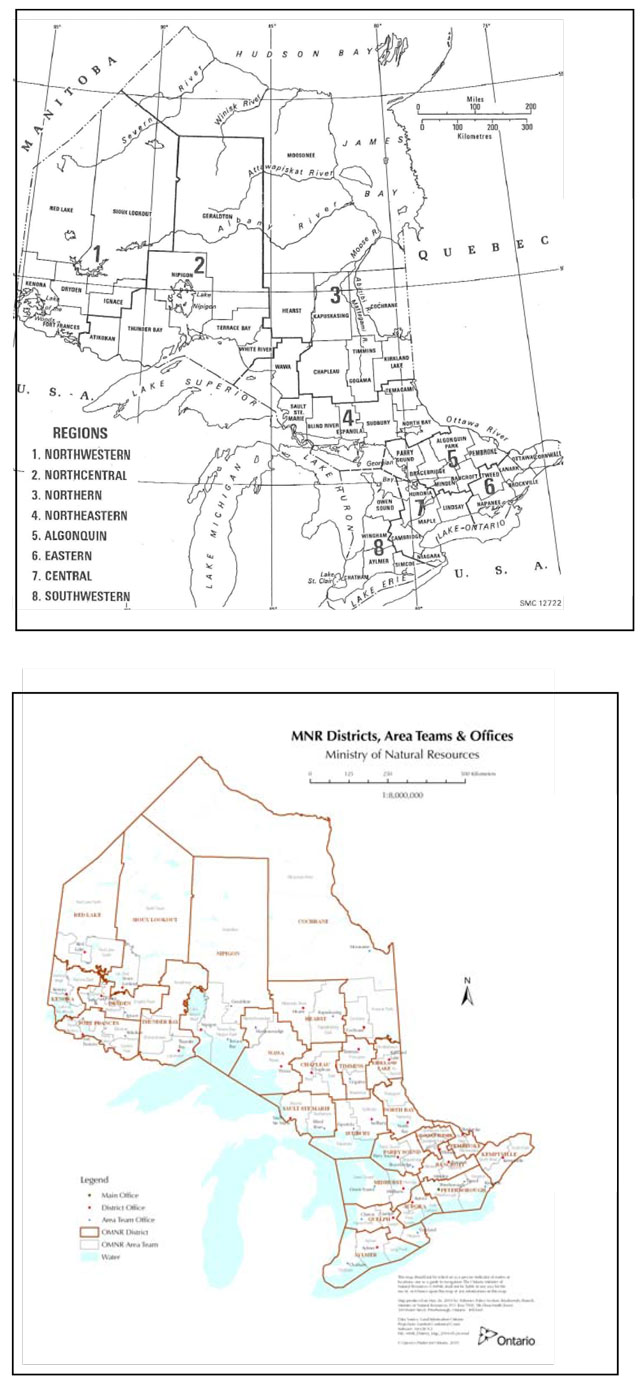

In 1973, the Ontario Department of Lands and Forests was reorganized to form the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. The new organizational structure included eight administrative regions and 47 districts (Figure 4). Bait licences and harvest areas were assigned by local work centres across the province.

A series of new provincial baitfish policies was implemented in 1978. These included:

- Baitfish harvest licences would only be issued to Ontario residents.

- Harvest licences would not be renewed for inactive operators.

- Licence fees would not be less than $20.

- Licensees would be assigned exclusive fishing grounds.

Figure 4. Organizational structure of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources in 1973 (top) and today (bottom).

As part of the provincial Strategic Planning for Ontario Fisheries (SPOF) initiative, a working group was established to review the bait industry. They released a report containing several proposals for baitfish harvest policies in Ontario (OMNR 1983). Highlights from that report included the following recommendations:

- Expand research activities to develop a baitfish productivity model.

- Encourage the establishment of local baitfish management councils.

- Retain the exclusive block system as a provincial standard for allocating baitfish resources.

- Amend legislation to separate the baitfish and commercial food fish industries.

- Retain the baitfish dealer’s licence.

- Develop new regulations to promote the husbandry of baitfish.

In the late 1990s, MNR initiated a process to create a new business partnership with the bait industry. It was recognized that the commercial bait industry was undervalued and minimally managed. Further, there was the need for more consistent policy and enforcement direction as well as more accurate reporting. A discussion paper (OMNR 1998) was prepared which outlined proposals for consideration. After extensive consultation with the bait industry, the plan was approved in 1998. The plan included increased licence fees to improve bait management, created the Bait Association of Ontario (BAO) as a new industry partner, developed a plan to modernize Ontario’s baitfish industry, and began to address many of the ecological issues affecting the industry at that time. The BAO assumed much of the administrative responsibility of bait management including education, training, and reporting.

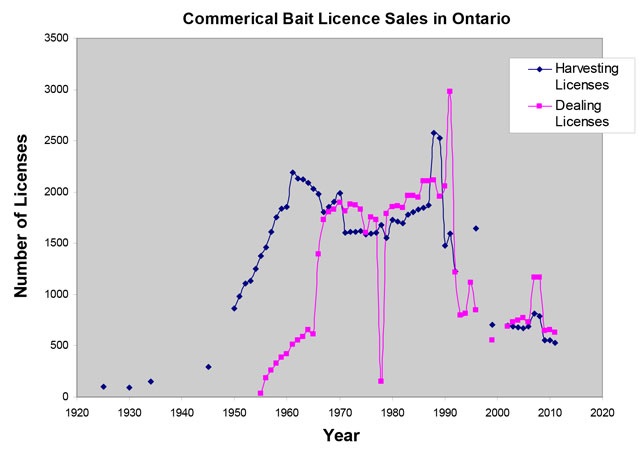

The number of bait licences, both harvester and dealer, issued in Ontario peaked in the late 1980s-early 1990s (Figure 5). Licence fees were increased in 1999. The basic fee for a bait harvest licence increased to $300 (from $30) with an additional $32.50 for each bait harvest area. Fees for a dealer licence increased from $17.50 in 1998 to $150.00. This fee increase was at least partially responsible for a 28% decrease in the total number of commercial baitfish licences issued in 1999 (Anonymous 2000). Licence fees were directed to a Special Purpose Account and used, in part, to finance administration of the BAO.

Shortly after the formation of the BAO-MNR partnership, action was taken on a number of outstanding issues. This occurred when the new provincial Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act replaced the former Game and Fish Act. A ban was placed on the use of salted (preserved) minnows by commercial dealers. A ban on the import of leeches occurred in two steps: anglers were banned from importation in 1999 and a complete ban (including commercial dealers) on import was instituted in 2005. Finally, the use of traps and dip nets by non residents was prohibited. Leeches were added to bait harvest licences to recognize their increasing importance. Shortly thereafter, the commercial bait frog industry was regulated.

Figure 5. Sales of bait harvest licences and bait dealers licences in Ontario.

An increasing demand for the ability to catch and sell lake herring as bait led to a northwestern Ontario initiative in 2002. A proposal (OMNR 2004a) was developed to allow bait harvesters to use small mesh gill nets on designated lakes, provided incidental catches of non-target species was low. The proposal was posted twice on the Environmental Registry and a decision notice to allow this practice was posted in February 2012.

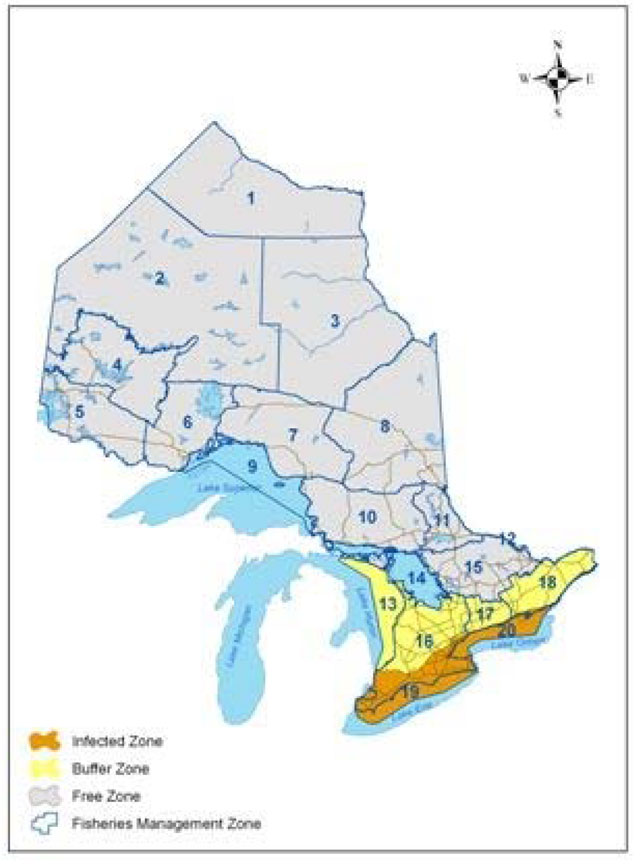

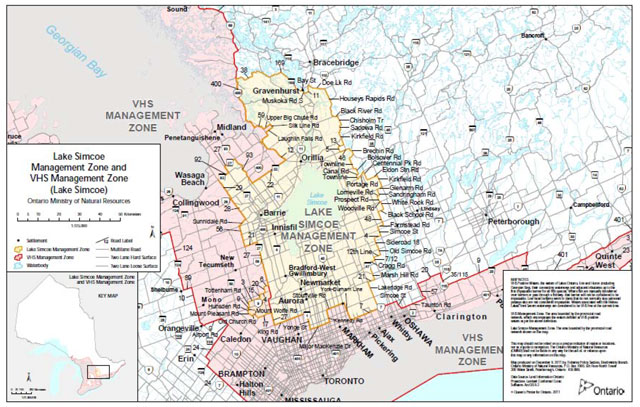

The discovery of Viral Hemorraghic Septicemia (VHS) in Ontario had major impacts on the bait industry. VHS is a virus that can weaken and kill fish. Although discovered from an archived sample in 2003, VHS was first detected in Ontario waters of the Great Lakes in 2005 and, subsequently, inland in 2011. The pathogen resulted in numerous fish mortalities. In October, 2006, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service placed a ban on all imports and interjurisdictional transport of 37 listed species of fish from eight Great Lakes states and two Canadian provinces. Within Ontario, actions were taken to slow the spread of VHS to inland waters. For the live bait industry this involved harvest and movement restrictions through the establishment of “virus-free”, “buffer” and “VHS positive” zones (Figure 6):

- A harvest moratorium was implemented in the VHS positive zone

- Stored bait, harvested prior to the prohibition, could be sold in the VHS positive zone but not in either the buffer or virus free zones,

- Live baitfish which were harvested from the buffer zone could not be moved into the virus-free zone

- Live bait harvested from either the buffer or virus-free zones could be sold in the infected zone

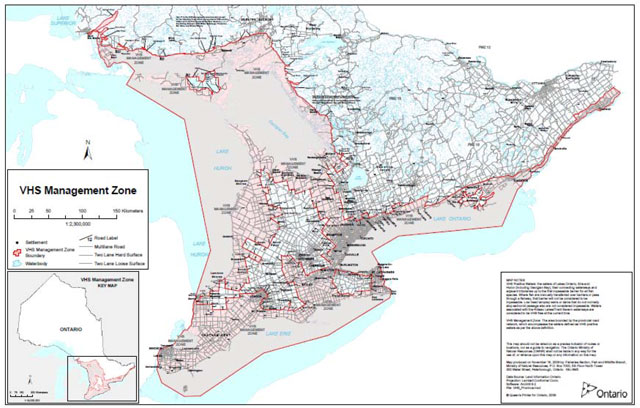

These measures were effective from January to March, 2007. Upon review, some boundary changes were made and the buffer zone was eliminated effective April 2007 (Figure 7).

Figure 6. VHS management zones implemented in January 2007.

In response to increasing concerns about the spread of non-native species and pathogens, the Ministry of Natural Resources in conjunction with the Bait Association of Ontario implemented a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) plan requirement for commercial bait licensees and a training program for commercial bait harvesters. The HACCP training program was originally developed for the bait industry in the United States to reduce the spread of invasive species. To ensure uncontaminated fish, water and equipment, the HACCP system is designed to identify invasive species hazards, establish controls and monitor these controls. HACCP is a preventive system to help ensure that fish, water and equipment are free of invasive species.

Figure 7. VHS management zone which was implemented in April, 2007.

The HACCP concept focuses on the part of the operation that is most likely to spread invasive species and minimize risk (Gunderson and Kinnunen 2002). Due to the more complex nature of bait harvesting operations, mandatory HACCP training was implemented over a multi-year period for bait harvesters while all commercial bait dealers were required to complete a simplified HACCP plan before their licences would be issued. Over a seven (2004-2011) year period, a total of almost 800 harvesters received HACCP training (Table 2).

Table 2. Ontario bait harvesters receiving HACCP training, 2004-2010.

| Year | # Training Sessions | # People Trained |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 (voluntary) | 6 | 30 |

| 2005 | 0 | 0 |

| 2006 | 6 | 122 |

| 2007 | 14 | 184 |

| 2008 | 19 | 180 |

| 2009 | 15 | 247 |

| 2010-11 | 9 | 32 |

Since 2010 all commercial bait harvesting licensees must complete (and have approved) a HACCP plan before their licence is issued. This requirement has been in place for commercial bait dealers since 2007.

A study was initiated by OMNR in 2011 to evaluate the effectiveness of HACCP training and to determine the frequency of non-target fish in the retail baitfish industry. This likelihood of human-mediated movement of aquatic species and pathogens using the baitfish pathway in Ontario. From this study there generally was a low occurrence of non-target species in retail products.

Despite measures designed to slow the spread of VHS, the virus was discovered in fish from Lake Simcoe in 2011. As a result, commercial bait operators were prohibited from moving commercial baitfish into or out of a new Lake Simcoe Management Zone (Figure 8) effective January 1, 2012. Anglers were advised to buy baitfish when they arrived to fish in the Lake Simcoe area and not take baitfish into or out of the area.

Figure 8. Lake Simcoe Management Zone which was implemented in 2012.

Currently, there are approximately 5,800 bait harvest areas in twenty-five different MNR districts in the province of Ontario (Note: There is no bait harvest allowed in Algonquin Provincial Park). Bait harvest activities are regulated through legislation and conditions of licence. Licence conditions address various issues including the movement of bait, travel corridors, types of gear utilized, and the timing of harvest. Mandatory reporting of fishing effort and harvest is a stipulation and an approved HACCP plan is required before a bait harvest licence is issued.

Current regulations involving live bait

Over the years, Ontario has established a number of regulations pertaining to the possession, transport and use of live bait (Table 3 and Appendix 3). Most regulations are designed to ensure the sustainability of wild live bait as well as prevent the transfer and introduction of non-native species.

Table 3. A summary of current regulations regarding the harvest and use of live bait in Ontario.

| Topic | Regulation |

|---|---|

| Angler Harvest |

|

| Commercial Harvest |

|

| Import of Bait |

|

| Personal Possession Limits |

|

| Prohibited Species |

|

| Release of Bait |

|

| Holding Facilities |

|

| Transport |

|

Bait harvest from Ontario waters

Ontario has the largest industry in Canada for the harvest and sale of baitfish (Table 4).

Table 4. An overview of the Canadian baitfish industry (based on a survey conducted by Canadian Aquaculture Systems Inc. 2007).

| Province/Territory | Year(s) | # Harvest Licences Issued | # Bait Dealers1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 2007 | 0 | 8 |

| British Columbia | 2007 | 0 | 16 |

| Manitoba | 2007 | 100 | 45 |

| New Brunswick | 2007 | 0 | 3 |

| Newfoundland/Labrador | 2007 | 0 | 1 |

| Northwest Territories | 2007 | 0 | 0 |

| Nova Scotia | 2007 | 0 | 10 |

| Nunavut | 2007 | 0 | 0 |

| Ontario | 2002-2005 | 1,384 – 1,439 | 261 |

| Prince Edward Island | 2007 | 0 | 3 |

| Québec | 1985 - 2004 | 53-66 | 33 |

| Saskatchewan | 1997-2004 | 2-160 | 27 |

1Value based on number of dealers listed in the Yellow Pages under “bait”.

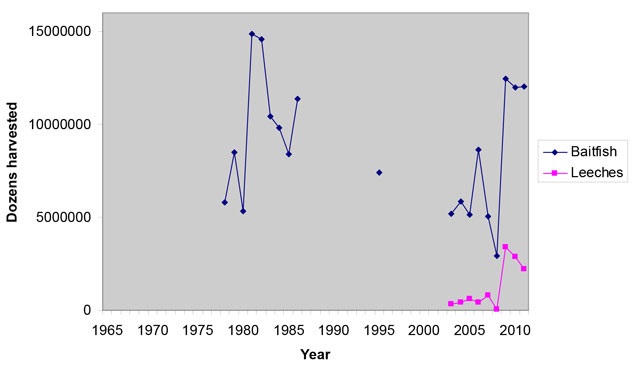

Reported bait harvests are illustrated in Figure 9. Unfortunately, data is unavailable for much of the period between 1986 and 2002. Harvests declined considerably in 2007 coincident with the implementation of measures to control the spread of VHS.

Figure 9. Reported harvests of leeches and baitfish in Ontario, 1970-2011.

Over the past nine years (2002-2010), provincial bait harvests in Ontario have averaged almost 4.7 million dozen baitfish. Comparatively, between 2004-2008, there was an average of 52 baitfish harvest licences issued in Manitoba and a mean annual harvest of 199,282 dozen baitfish (live and frozen) reported (Manitoba Water Stewardship 2009). In 2003, 117 licensees harvested approximately 5,100 kg of baitfish in the province of Saskatchewan (Ashcroft et al. 2006). Between 1985 and 2001, an average of 7.2 million dozen baitfish were harvested annually in South Dakota (Broughton and Potter 2003). The three year (1976-78) average harvest of baitfish in Minnesota was 14.6 million dozen.

Economics of the commercial bait industry

Ontario is believed to have the largest live bait industry in Canada (Goodchild 1997) but estimates of its value vary considerably. Sales of baitfish in Ontario totalled $1.5 million in 1963 (Payne 1965). In 1980, the commercial baitfish industry was valued at $12.4 million (Goodchild 1997). By the mid 1980s the retail value of Ontario’s bait industry was conservatively estimated at $29 million (US) (Litvak and Mandrak 1993). In the late 1990s, the value of the commercial bait industry was estimated at between $40-60 million (OMNR 1998). More recently (2005) the commercial bait industry in Ontario was valued at $17 million in direct sales and $23 million when other related sales were considered (OMNR 2009a). In comparison, the 2009 live bait industry in Manitoba had gross sales of $1.04 million (Manitoba Water Stewardship 2009). Maine’s winter baitfish industry has been valued at $4.7 million (Kircheis 1998). The value of the 2001 baitfish harvest in South Dakota was estimated at $3.8 million (Broughton and Potter 2003). The direct sales of bait in Wisconsin during 1992 was estimated at $35.2 million (Manwell 1997). Minnesota’s baitfish harvest and sale industry has been valued at $50 million (Dickson 2012). In the United States, the freshwater baitfish industry has sales over $170 million annually (Goodwin et al. 2004). In the mid 1990s, Rosen (2005) estimated the value of the baitfish industry in Canada and the United States was approximately $1 billion.

Although prices vary considerably across Ontario, the prices charged for live baitfish have increased steadily over the years. In the mid 1960s the price for one dozen baitfish ranged from 22-39¢. By 1982, the price ranged from 50¢ to $1.50 per dozen. Table 5 illustrates the value of various sizes of baitfishes in 2000. In 2003, retail prices per dozen for various bait species was $3.50 for baitfish, $4.00 for leeches, $7.00 for frogs, $3.00 for crayfish, and $8.00 for lake herring. In a survey of selected bait dealers during the winter of 2012 bait prices varied based on the size of fish (e.g., “small” ranged from $2.5-$6.00 per dozen, “medium” ranged from $4.00 - $8.00 per dozen, and “large” ranged from $4.50 to $12.00 per dozen) (Lauretta Dunford, OMNR, personal communication).

Table 5. Baitfish values in 2000.

| Grader Size | Bait used for | Wholesale Value ($) in Gallons | Retail Value ($) in Dozens |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | Fish returned to water | N/A | N/A |

| 17 | Crappies and perch | $50 | $1 |

| 23 | Bass | $50 | $2 |

| 33 | Walleye | $50 | $4 |

| 44 | Small pike | $50 | $6 |

| 51 | Large pike | $45 | $13 |

| 63 | Large pike and musky | 25-35¢ each | $1-1.25 each |

| Lake herring | Pike and lake trout | $4 per dozen | $8 per dozen |

Note: A grader is a screen or sieve used to sort fish based on their size.

Problems and issues

Supply and demand

In a 1980 survey in northwestern Ontario (Hildebrand-Young Associates Inc. 1981), anglers indicated that they placed a high value on the availability of baitfish. A large portion of live baitfish, such as emerald shiners (Notropis atherinoides), are harvested during the autumn. Unfortunately, bait of a desired size is a perishable commodity which cannot be stockpiled for long periods of time (Davis 1993). Shortage of bait during certain periods of the year is a common problem in many North American jurisdictions (Noel and Hubert 1988, Meronek et al. 1997, Eddy 2000, Gunderson and Tucker 2000). In Ontario it is not uncommon for bait shortages to occur in mid summer (Anonymous 1956, Hughson 1968, Sandilands 1976) as well as some periods in the winter (Mulligan 1960, Brubacher 1962, Winterton 2005). Shortages may be attributed to the periods of heaviest angling pressure as well as the fact that it becomes more difficult to catch baitfish under ice cover during the winter or as the water warms up in mid summer.

Recently, management actions, such as emergency responses to the detection of VHS, have also served to alter supply and demand.

Capture/harvest of species at risk

Anglers or licensed harvesters capturing bait from waters that contain species at risk (see Table 6) may inadvertently capture a federally or provincially listed species. Under both the provincial Endangered Species Act (ESA) (2007) and federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) legislation, it is illegal to fish (whether angling, commercial or bait harvesting) for or possess species listed as Threatened, Endangered, or Extirpated.

Species designated as Special Concern are prohibited from being used as bait under the Ontario Fishery Regulations Under both the ESA and SARA, there is provision for incidental catch of species at risk as long as they are caught in accordance with the terms and condition of their licence and due diligence is exercised to avoid capture and possession. However, some fish species at risk are difficult to identify and may be missed during the initial sorting at the capture site and, if the harvester can’t return them immediately to the original capture site unharmed, the fish must be destroyed as per the conditions of their licence.

Table 6 [reproduced below]. Small fishes designated as Species at Risk in Ontario.

- Black Redhorse (Moxostoma duquesnei)

- Blackstripe Topminnow (Fundulus notatus)

- Bridle Shiner (Notropis bifrenatus)

- Channel Darter (Percina copelandi) Cutlip Minnow (Exoglossum maxillingua)

- Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida)

- Gravel Chub (Erimyustax x-punctatus)

- Lake Chubsucker (Erimyzon sucetta)

- Redside Dace (Clinostomus elongates)

- Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emillae)

- Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus)

- River Redhorse (Moxostoma carinatum)

- Silver Chub (Macrhybopsis storeriana)

- Silver Shiner (Notropis photogenis)

- Spotted Sucker (Minytrema melanops)

Incidental capture by Ontario bait harvesters, particularly by those using seine nets, was identified as a potential threat to many of the species identified in Table 6 including redside dace (Redside Dace Recovery Team 2010), cutlip minnow (Crossman and Holm 1996), lake chubsucker (COSEWIC 2008, Vlasman et al. 2008), pugnose shiner (DFO 2011) silver chub (DFO 2010), spotted sucker (DFO 2009), bridle shiner (DFO 2010), and eastern sand darter (Campbell 2009).

Spread of disease, parasites, and exotic organisms

The collection and sale of non-bait species, whether accidental or intentional, is not uncommon. Litvak and Mandrak (1993) reported finding six illegal baitfish species in four Toronto, Ontario, bait shops. Ludwig and Leitch (1996) found non-bait species in 28.5% of bait samples purchased from 21 bait dealers in North Dakota and Minnesota. Kircheis (1998) found ten illegal species in a survey of Maine bait dealers.

“Bait bucket” releases related to the live bait industry are regarded as the primary cause for the introduction and spread of many non-native aquatic organisms (DiStefano et al. 2009). Studies have shown that 41-46% of anglers empty their bait buckets at the end of their fishing trip (Litvak and Mandrak 1993, Dextrase and MacKay 1999). There are currently no restrictions on angler movement of live bait within Ontario. Historically, a large proportion of live baitfish were harvested from the Great Lakes and shipped inland for sale. This provided the opportunity to introduce many non-native species and fellow travellers to inland waters.

The improper disposal of live baitfish has been attributed as the source of introduction for at least 14 species in Ontario (Litvak and Mandrak 2000). In a two year study in Ohio, Snyder (2000) found that between 17-39% of baitfish purchased from retail outlets contained non-target fishes. Similarly, in a Pennsylvania survey, LoVello and Stauffer (1993) found seven different species of unapproved fish in bait dealer’s holding tanks. A three day inspection of southcentral Ontario bait dealers in 2012 recovered seven non- bait species (44 specimens) (Mark Robbins, OMNR, personal communication). It is believed that the rudd (Scardinus erythrophthalmus) was introduced into Ontario via a bait bucket release (Crossman et al. 1992, Kapuscinski et al. 2012). The dispersal of rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax) in Ontario has been attributed to the release of live bait (Litvak and Mandrak 1993). Goodchild and Tilt (1976) attributed the introduction of river chub (Nocomis micropogon) to eastern Ontario as the result of release of baitfish. The non-native rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) is believed to have been spread through Ontario and the northern United States by anglers using them as bait (Kerr et al. 2005, Berube and Kraft 2010, Hamr 2010). Frogs being sold as bait have been identified as a vector in the spread of the infectious disease Ranavirus (Kidd 2004). Reader (undated) concluded that the risk of spreading VHS, by movements of emerald shiners being sold as bait, was high. Similarly, Ludwig and Leitch (1996) concluded that angler use of live baitfish had a high potential of moving non-native species into new waterbodies and drainage basins.

Lodge et al. (2000) stated that the release of live bait was the most important vector for introductions of non-indigenous crayfish and advocated for a ban on the use of crayfish as bait. Rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) were first introduced into Ontario from Ohio by anglers using them as bait (Hamr 2000, Jansen et al. 2009). The introduction of the aggressive rusty crayfish has led to declines of native crayfish species (Taylor et al. 1996). Berrill (1978) concluded that anglers persist in moving crayfish and are likely to promote extension of non-native species. Lodge et al. (2000) advocated making the use of live crayfish illegal in the United States in order to halt the introduction of non- indigenous crayfish.

There are some concerns about the introduction of non-native earthworms to various areas of North America (Hendrix and Bohlen 2002, Hendrix et al. 2008, Evers et al. 2012). Unused worms discarded by anglers is believed to be an important vector in their spread (Cameron et al. 2008, Hale 2008). Keller et al. (2007) concluded that the bait trade and subsequent disposal of nonindigenous worms by anglers constituted a major vector for earthworm introductions.

There are also concerns about the spread of viruses and diseases by anglers using live baitfish (Goodwin et al. 2004, Good 2007). The transfer and release of holding water can also serve to introduce harmful species (“fellow travellers”). A fellow traveller is an organism which inadvertently accompanies the intended or desired species. The spiny water flea (Bythotrephes longimanus) is an example of an invasive species which was spread as a fellow traveller through the use of live bait (Kerfoot et al. 2011).

Finally, the gear used for harvesting wild bait can also serve as a pathway for the spread of an invasive species. Organisms may adhere and accumulate on gear (e.g., nets, traps, etc) which is used in a variety of different waterbodies. Sometimes, non-target species and plant fragments can be collected with baitfish and transported to other waters.

To prevent the introduction, transfer or spread of aquatic invasive species, a number of best management practices have been developed for the live bait industry (Table 7).

Table 7 [reproduced as a list]. Best management practices and regulatory requirements for preventing the introduction or transfer of aquatic invasive species in the live bait industry.

- Inspect and remove non-target fish and plant species.

- Separate new and old shipments /catches of fish.

- Dispose of unwanted live bait on dry land – never into a waterbody.

- Never release bait or aquatic plants into different waters from where they came.

- Clean boats, trailers, and equipment on shore before leaving the access point.

- Hand clean and dry nets before reuse.

- Drain water from boats and equipment before leaving the waterbody access.

- Avoid storing live baitfish in holding facilities that are linked through an inflow or outflow to natural waters.

- Do not use water known to contain nuisance species to transport live bait.

- When in areas known to have aquatic invasive species do not use the same equipment in other waters.

- Rinse and dry equipment, boats and trailers for five days. Before reuse, roll out, hand clean and dry nets for ten days.

Figure 10. Extension projects are designed to educate anglers about the negative impacts of unauthorized bait bucket releases (Wil Wegman photo).

Baitfish are known to host several types of parasite. Even dead bait can carry diseases or parasites. In 2011 survey, Purdy (2011) recovered 248 parasites (38 species) from baitfish sampled at a number of collection sites in Wisconsin. The baitfish industry and human movements of baitfish may serve to extend the ranges of some parasites (Peeler and Feist 2011, Passarelli 2010). A recent example was the discovery of the Asian fish tapeworm (Bothriocephalus acheilognathi) which was found in a bluntnose minnow (Pimephales notatus) captured from the Detroit River in 2002 (Marcogliese 2008). This was the first report of the Asian tapeworm in the Great Lakes.

Management of the bait industry has become increasingly complex as the risks of aquatic invasive species are realized.

Reporting accuracy

Some bait harvesters and dealers are reluctant or unwilling to provide accurate records of their activities to government (Hildebrand-Young and Associates 1981, Kircheis 1998). Reporting inaccuracy and a low rate of voluntary reporting has historically been a problem resulting in underestimates of harvest and sales (Adair 1970, Sandilands 1976, Buckingham et al. 1978, Busiahn 1996, Goodchild 1997). Lack of knowledge regarding numbers of baitfish harvested and the value of the baitfish industry is a problem common in many North American jurisdictions (Canadian Aquaculture Systems Inc. 2007).

Mulligan (1962) reported that, between 1959 and 1961, the number of bait harvesters submitting annual returns ranged from 36-68% in the Sudbury area. In the Lake Simcoe watershed, Pugsley (1983) found that reporting forms were completed correctly by only 38% of respondents and that return data was inconsistent in 46% of cases. Many harvesters did not report their catch in standard measures (e.g., pounds, gallons, dozens, etc) or used size (e.g., small, medium, large) instead of identifying different fish species (Sandilands 1976).

One of the potential reasons for inaccuracy is the disconnection between how baitfish are measured when harvested compared to when they are sold. In the field, enumeration of the catch is often done by crude measurements or bulk estimates involving volume or weight. When sold by a retailer, measurements are more accurate often involving numbers of individual fish. In other instances, small fishes are sold by the scoopful thereby making enumeration difficult.

Despite efforts in recent years to improve the accuracy of returns, problems still exist (OMNR and BAO 2004). Undoubtedly, estimates of bait harvested are underestimates (Canada Aquaculture Systems Inc. 2007).

Differential treatment of bait harvesters and anglers

The bait industry has complained that a potentially unlimited number of anglers can trap the same water as the bait harvester and compete for the same resource at no charge other than the cost of an angling licence.

Anglers are also known to be a vector with regard to the movement and spread of non- native organisms (Kerr et al. 2005, Drake 2011). Members of the live bait industry often cite differential treatment when compared to anglers. A recent example involved restrictions imposed on the movement of live baitfish between VHS management zones by the baitfish industry yet no restrictions were placed on the movement of live bait by anglers. Currently there are no requirements for anglers to inspect their bait traps on a regular basis. There have been complaints that traps are often left unattended for extended periods of time and that captured fish die and are wasted. In a survey of selected North American jurisdictions, Murray and Lodge (2007) found that few governments had crayfish transport regulations which were consistent for both anglers and bait harvesters.

Compliance

There have been problems of non-compliance with commercial bait regulations. Problems have included not adhering to conditions on the licence, non-reporting, illegal transfers of fish, and unlicenced harvest and sale. Another common problem is that annual bait reports are not completed properly or not submitted at all. The penalty for failure to report is usually a fine. Anglers are known to move and release live bait in waters other than where they were caught. There have also been reports of anglers selling the bait they catch to dealers despite the law prohibiting the sale of baitfish caught under the authority of a sport fishing licence.

In 2006, MNR adopted a risk-based approach to compliance and enforcement operational planning. This process focuses compliance and enforcement efforts to incidents that pose the greatest risk to human health and safety, natural resources protection, and risks to the economy. Since 2006 two of the provincial priorities have had a direct relationship to bait policy. These two priorities fall under the categories of:

- Biodiversity – preventing the movement and spread of aquatic invasive species, and

- Commercial fisheries - unregulated or illegal harvest and sales of fisheries resources.

While these issues are broader than bait compliance monitoring, over the past five years, approximately 3,200 enforcement hours and 1,800 enforcement hours, respectively, have been dedicated to these priorities.

Resource tenure

Although bait harvest areas are designated primarily to individual harvesters, there have been some issues with regard to resource tenure. The issues include harvest by anglers and non-authorized individuals, damage to baitfish waters by competing enterprises (e.g., mining, forestry, etc), and the absence of any tenure guarantee necessary to encourage investment by the bait harvester.

Ecological impacts of overharvest

There have been long standing concerns regarding the lack of knowledge about baitfish productivity and sustainable levels of harvest. There is little biological knowledge on the productivity of bait species which can be used to establish quotas to prevent overharvest (Portt 1985). Currently, there are no quotas or royalties established for bait harvesters.

There is some evidence to suggest that many baitfish species are relatively resilient to harvest by traditional techniques. Duffy (1998) found that moderate levels of harvest had little influence on the dynamics of fathead minnows in prairie wetlands. Topolski et al. (2002) concluded that the current rate of harvest of mummichogs (Fundulus heteroclitus) and banded killifish (Fundulus diaphanous) for baitfish was not having a significant effect on the abundance, availability, or reproductive potential of either species. Larimore (1954) removed 76,217 minnows from a 1.5 km stretch of a small Illinois stream over a multi-year (1950-1953) period. He found that removal did not reduce population abundance for longer than a few months. Brandt and Schreck (1975) conducted experimental harvest of baitfish at varying degrees of intensity but found that differing harvest pressure did not appear to affect densities of either bait or game fish species. Conversely, Portt (1985) concluded that, in several Ontario streams, the abundance of baitfish decreased with successive harvests and that the effects of harvest extended beyond the sample site.

There is also a great degree of variance in productivity among waterbodies. For example, harvests of fathead minnows from various South Dakota waters ranged from 1.2 - 246.4 kg/ha (Broughton and Potter 2003). Duffy (1998) reported that densities of fathead minnows varied from 52,000 to 241,000 fish/ha in four prairie wetlands. In three small southern Ontario lakes, Fraser (1981) reported densities of golden shiners ranged from 481 – 2,111 fish/ha. Similarly, Jackson and Harvey (1997) estimated densities of creek chub ranged from 7 – 36 fish/ha in four small southern Ontario lakes.

Some concerns have been expressed about the potential overharvest of bait species including leeches (Friesen 2000, Pennuto undated), baitfishes (D’Agostini 1957, Weir 1957, Sandilands 1976, Noble 1981, Frost and Trial 1993), frogs, and crayfish (Roell and Orth 1988). Resource conservation concerns regarding the potential overharvest of some baitfishes (primarily emerald shiner) in Lakes Simcoe and Erie, was the rationale for banning the commercial harvest and sale of minnows as salted bait in 1999.

In Ontario, the management approach taken to date is to allocate exclusive use of designated areas to active bait harvesters. It is obviously in the harvester’s best interest not to overexploit the resource which they have been allocated. The determination of sustainable harvest and yields of various bait species is an area where more research is required.

Transfer and sale of bait harvest areas

When a bait harvester wishes to discontinue their activities, their bait harvest area(s) (BHA) reverts back to the Crown and MNR must determine if the licence will be reallocated or transferred. Under no conditions can a harvester sell their bait harvest area to another operator. This is believed to occur, however, under the guise that the purchaser is paying for improvements (e.g., dock, trails, boat slips, etc) to the BHA.

Alteration of fish habitat

Some bait harvesting techniques may result in harmful alterations to fish habitat. For example, the use of a seine net can uproot aquatic vegetation, remove woody debris, and disrupt the substrate (Fisheries and Oceans et al. 2011). Walking over spawning and nursery areas may also cause mortality to some non-target species including species at risk. It could also dislodge some species at risk such as mussels and turtles.

Areas where bait harvest is prohibited

One of the concerns which has been expressed by the bait industry is of declining access to waters, particularly on the Great Lakes, for the harvest of wild baitfish (Busiahn 1996). Increasingly, there are more areas of the province in which the practice of harvesting live bait is prohibited. One example is the restriction of commercial bait harvest in protected areas (OMNR 20010). Commercial bait harvest is not permitted in some provincial parks. Existing baitfish operations in park classes and zones where commercial bait harvest is not permitted are planned to be phased out. This will affect activities in 32 provincial parks and approximately 100 bait harvest areas (OMNR 2009).

There are no specific restrictions on commercial bait harvest in conservation reserves. There is the need for a broad review on the commercial harvest of bait on protected areas of Crown land. Concerns over bait harvest and use in protected areas include the risk of invasive species introductions, ecological sustainability of activities, and consistency with protected area and park class objectives.

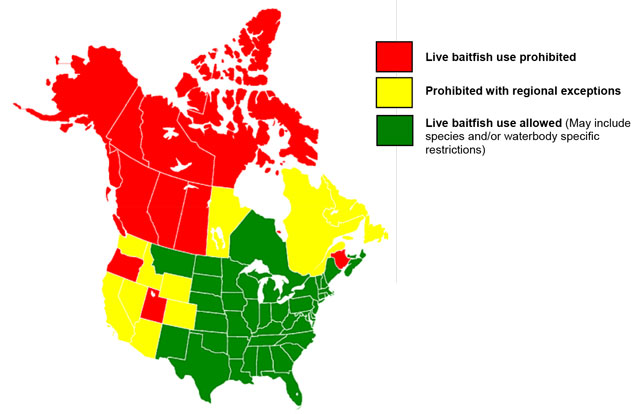

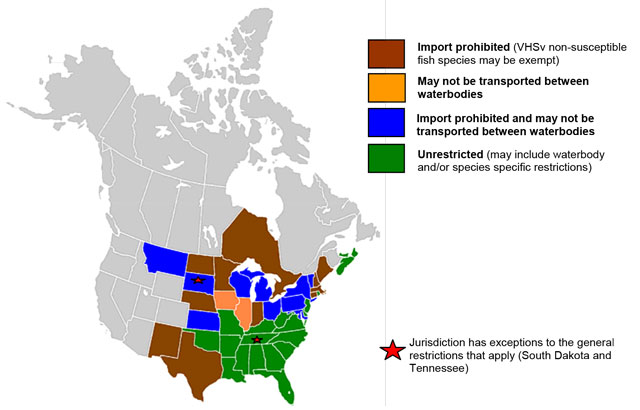

Bait policies and regulations in adjacent jurisdictions

There have been several comparative reviews of bait regulations in North America (Stanley et al. 1991, Meronek et al. 1995, Goodchild 1997, Dunford 2012). Regulations and policies with regard to live bait vary considerably among North American jurisdictions (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11. Use of live bait for recreational angling in North America (from Dunford 2012)

Figure 12. Import and movement restrictions on live bait in North America (from Dunford 2012).

In North American jurisdictions where the use of live bait is allowed, Ontario is one of the least restrictive in terms of regulations. Many Canadian jurisdictions have banned the use of live bait. The province of Québec plans to eliminate the use of live and dead baitfish during the open water season by 2017 (Nadeau 2012). Most jurisdictions in the Great Lakes basin have controls on the transport and use of live bait. Only the southern U.S. states allow the relatively unrestricted use of live bait.

Litvak and Mandrak (1993) found that, in a comparative survey from 1956 and the 1990s, most North American jurisdictions had become more restrictive with regard to live bait regulations.

Acknowledgements

Matt Garvin and Lauretta Dunford provided information on bait policies and regulations from other North American jurisdictions. Julie Formsma provided information on bait licence sales. Brenda Koenig provided details on provincial bait policy and legislation. Bob Bergmann, Larissa Mathewson-Brake, Lauretta Dunford, Scott Gibson, Karen Hartley, Brenda Koenig, and Mark Robbins provided an editorial review of an earlier version of this background report.

Literature cited

Adair, T. 1970. 1969 baitfish report, Sioux Lookout District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sioux Lookout, Ontario. 4 p.

Anonymous. 1956. Lake Erie District baitfish report. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. 3 p.

Anonymous. 1962. Earthworms for bait. Leaflet FL-23. Fish and Wildlife Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D. C.

Anonymous. 1966. 1965 baitfish report for the Lake Huron District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. 3 p.

Anonymous. 1969. Kenora District baitfish report, 1968. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kenora, Ontario. 8 p.

Anonymous. 1970a. Kenora District baitfish report, 1969. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kenora, Ontario. 10 p.

Anonymous. 1970b. 1969 commercial baitfish industry, Lake Huron District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Hespeler, Ontario. 4 p.

Anonymous. 2000. Ontario commercial bait licences statistical report, 1999. Fisheries Section, Fish and Wildlife Branch. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 8 p.

Ashcroft, P., M. Duffy, C. Dunn, T. Johnston, M. Koob, J. Merkowsky, K. Murphy, K. Scott, and B. Senik. 2006. The Saskatchewan fishery: history and current status. Technical Report 2006-02. Saskatchewan Environment. Regina, Saskatchewan. 61 p.

Atkinson, D. G. 1969. Experimental sucker hatchery at the Matachewan Indian Reserve. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kirkland Lake, Ontario. 6 p.

Bailey, R. G. 1965. 1964 baitfish report for the North Bay District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. North Bay, Ontario. 4 p.

Bait Association of Ontario (BAO) and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2004. The commercial bait industry in Ontario. 2003 statistical report. Peterborough, Ontario. 4 p.

Bait Association of Ontario (BAO) and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) 2005. The essential bait field guide for eastern Canada, the Great Lakes region and northeastern United States. University of Toronto Press. Toronto, Ontario. 193 p.

Bait Association of Ontario (BAO) and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2006a. The commercial bait industry in Ontario. 2004 statistical report. Peterborough, Ontario. 6 p.

Bait Association of Ontario (BAO) and the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2006b. The commercial bait industry in Ontario. 2005 statistical report. Peterborough, Ontario. 7 p.

Bardach, J. E., J. H. Ryther, and W. O. McLarney. 1972. Culture of freshwater crayfish: the farming and husbandry of freshwater and marine organisms. John Wiley and Sons Inc. Toronto, Ontario. 868 p.

Baxter, R. A. 1967.Sioux Lookout District annual fish and wildlife management report, 1966-67. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sioux Lookout, Ontario.

Berrill, M. 1978. Distribution and ecology of crayfish in the Kawartha lakes region of southern Ontario. Canadian Journal of Zoology 56:166-177,

Berube, D. and L. Kraft. 2010. Invasion of rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) into Whitefish Lake, Ontario. Aquatic Update 2010-3. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Thunder Bay, Ontario. 8 p.

Brandt, T. M. and B. Schreck. 1975. Effects of harvesting aquatic bait species from a small West Virginia stream. Transactions of the America Fisheries Society 104:446-453.

Brooks, D. M. 1966. 1965 baitfish report for the Lake Erie District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. 11 p.

Broughton, J. and K. Potter. 2003. 2001 summary of South Dakota baitfish harvest. Annual Report 03-03. South Dakota Department of Fish and Game. Pierre, South Dakota. 10 p.

Brousseau, C. 2002. Results of a BAO/MNR crayfish survey. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 8 p.

Brousseau, C., P. Sullivan, and L. Shirose. 2003. The commercial bait frog industry in Ontario. Fisheries Section. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 9 p.

Brown, P. and J. Gunderson. 1997. Culture potential of selected crayfishes in the Northcentral Region. Technical Bulletin Series #112. Purdue University and the University of Minnesota-Duluth. West Lafayette, Indiana. 26 p.

Brubacher, M. J. 1962. The baitfish industry in Ontario. Ontario Fish and Wildlife Review 1(7):15-21.

Buckingham, N. L., R. Mulholland, and D. Dubois. 1978. Niagara District baitfish study, summer Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Fonthill, Ontario. 21 p.

Burtle, G. J. undated. Baitfish production in the United States. Aquaculture Technical Series. University of Georgia. Athens, Georgia. 15 p.

Busiahn, T. R. 1996. Ruffe control program. Report to the Aquatic Nuisance Species Task Force of the Ruffe Control Committee. Ashland, Wisconsin.

Buss, M. E. 1967. 1966 baitfish report, North Bay District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. North Bay, Ontario. 5 p.

Caldwell, B. J. 1965. Fort Frances District annual baitfish report, 1964. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Fort Frances, Ontario.

Caldwell, B. J. 1969. Fort Frances District baitfish report, 1968. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Fort Frances, Ontario. 5 p.

Cameron, E. K., E. M. Bayne, and D. W. Coltman. 2008. Genetic structure of invasive earthworms in Alberta: insights into introduction mechanisms. Molecular Ecology 17:1189-1198.

Campbell, R. 2009. Assessment and status update on the eastern sand darter (Ammocrypta pellucida). Draft report prepared for the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario. 61 p.

Canadian Aquaculture Systems Inc. 2007. Overview of the Canadian baitfish industry. Final Report prepared for the Canada Food Inspection Agency. Ottawa, Ontario. 85 p.

Carlson, E. 1979. Baitfish in the West Patricia planning area. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Red Lake, Ontario. 5 p.

Chappel, J. A. 1967. The 1966 commercial baitfish report for the Geraldton District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Geraldton, Ontario. 3 p.

Chappel, J. A. 1968. The 1967 commercial baitfish report for the Geraldton District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Geraldton, Ontario. 5 p.

Collins, H. L., L. L. Holmstrand, and W. Jesswein. 1983, Bait leech (Nephelopsis obscura) culture and economic feasibility. Research Report No. 9. Minnesota Sea Grant. Duluth, Minnesota. 20 p.

Crossman, E. J., E. Holm, R. Cholmondeley, and K. Tuininga. 1992. First record for Canada of the rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus) and notes on the introduced round goby (neogobius melanostomus). Canadian Field Naturalist 101:584-586.

D’Agostini, D. 1957. Future policy for baitfish management in the Port Arthur District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Thunder Bay, Ontario. 2 p.

Davis, J. T. 1993. Baitfish. p. 307-322 In R. R. Stickling [ed.]. Culture of nonsalmonid freshwater fishes. CRC Press. Ann Arbor, Michigan. 331 p.

de la Brotonne, L. W., and R. P. Romaire. 1990. Crawfish culture – site selection, pond construction, and water quality. Publication No. 240. Southern Region Aquaculture Center. College Station, Texas.

Dextrase, A. J. 1997. Proposal to prohibit the import of leeches for use as bait – summary of public consultation. Lands and Natural Heritage Branch. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 20 p.

Dextrase, A. J. and B. MacKay. 1999. Evaluating the effectiveness of aquatic nuisance species outreach materials in Ontario. p. 103 In Abstracts from the 9th International Zebra Mussel and Aquatic Nuisance Species Conference. April 26-30 1999, Duluth, Minnesota.

Dickson, T. 2012. The scoop on minnows. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. St. Paul, Minnesota.

Dore, D. E. 1970. 1969 baitfishery report, White River District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. White River, Ontario. 4 p.

Drake, D. A. R. 2011. Quantifying the likelihood of human mediated movements of species and pathogens: the baitfish pathway in Ontario as a model system. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Toronto. Toronto, Ontario. 273 p.

Duffy, W. G. 1998. Population dynamics, production, and prey consumption of fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) in prairie wetlands: a bioenergetics approach. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 54:15-27.

Dunford, L. 2012. 2012 survey of North American recreational baitfish regulations. Fisheries Policy Section, Biodiversity Branch. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 34 p.

Eddy, J. B. 2000. Estimation of the abundance, biomass, and growth of a northwestern Ontario population of finescale dace (Phoxinus neogaeus) with comments on the sustainability of local baitfish harvests. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Manitoba. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 85 p. + appendices.

Evers, A. K., A. M. Gordon, P. A. Gray, and W. I. Dunlop. 2012. Implications of a potential range expansion of invasive earthworms in Ontario’s forested ecosystems: a preliminary vulnerability analysis. Climate Change Research Report 23. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and the University of Guelph. 31 p.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Bait Association of Ontario, and the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters, 2011. The baitfish primer. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 40 p.

Forney, J. L. 1957. Raising baitfish and crayfish in New York ponds. Extension Bulletin 986:3- Cornell University. Ithaca, New York.

Fraser, J. M. 1958. The minnow situation in the Kenora District. Fish and Wildlife Management Report No. 39. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Toronto, Ontario.

Fraser, J. M. 1981. Estimates of the standing stocks of fishes in four small Precambrian Shield lakes. Canadian Field Naturalist 95:137-143.

Frost, F. O. and J. G. Trial. 1993. Factors affecting baitfish supply and retail prices paid by Maine anglers. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 13:586-593.

Friesen, T. 2000. The biology and use of leeches as commercial bait in Ontario. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 49 p.

Good, S. 2007. Viral hemorrhagic septicaemia and baitfish use and movement in Vermont. Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife. Waterbury, Vermont. 7 p.

Goodchild, C. D. 1997. Live baitfish – An analysis of the value of the industry, ecological risks, and current management strategies in Canada and selected American states with emphasis in Canada. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 92 p.

Goodchild, G. A. and J. C. Tilt. 1976. A range extension of Nocomis micropogon, the river chub, into eastern Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 90:491-492.

Goodwin, A. E. 2012. Baitfish certified free if aquatic nuisance species and important diseases: the future is now. Fisheries 37(6):267.

Goodwin, A. E., J. E. Peterson, T. R. Meyers, and D. J. Money. 2004. Transmission of exotic fish viruses: the relative risks of wild and cultured bait. Fisheries 29:19-23.

Gostlin, G. A. 1968. The commercial baitfish fishery in the Pembroke District, 1967. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Pembroke, Ontario. 3 p.

Gostlin, G. A. 1969. The commercial baitfish industry in the Pembroke District, 1968. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Pembroke, Ontario. 3 p.

Gostlin, G. A. 1970. The commercial baitfish fishery in the Pembroke District, 1969. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Pembroke, Ontario. 3 p.

Gow, J. 1963. The commercial baitfish fishery in the Geraldton District, 1962. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Geraldton, Ontario. 2 p.

Gow, J. 1965. The commercial baitfish fishery in the Geraldton District, 1964. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Geraldton, Ontario. 2 p.

Gunderson, J. L. and P. Tucker. 2000. A white paper on the status and needs of baitfish aquaculture in the northcentral region. University of Minnesota. Duluth, Minnesota. 24 p.

Gunderson, J. L. and R. E. Kinnunen. 2002. The HACCP approach to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species by aquaculture and baitfish operations. Michigan and Minnesota Sea Grant Programs. Duluth, Minnesota. 25 p.

Hale, C. M. 2008. Evidence for human-mediated dispersal of exotic earthworms: support for exploring strategies to limit further spread. Molecular Ecology 17:1165-1169.

Hamr, P. 1997. The potential for commercial harvest of the exotic rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus): a feasibility study. ow Crayfish Enterprises. Keene, Ontario. 17 p.

Hamr, P. 2000. The impact of introduced freshwater crayfishes in Canada. p. 113-120 In Proceedings of the 2000 International Aquatic Nuisance Species and Zebra Mussel Conference. Toronto, Ontario.

Hamr, P. 2010. The biology, distribution and management of the introduced rusty crayfish (Orconectes rusticus) in Ontario, Canada. Freshwater Crayfish 17:85-90.

Hendrix, P. F. and P. J. Bohlen. 2002. Exotic earthworm invasions in North America: ecological and policy implications. Bioscience 52:801-811.

Hedges, S. B. and R. C. Ball. 1953. Production and harvest of bait fishes in Michigan. Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Ann Arbor, Michigan. 30 p.

Hendrix, P. F., M. A. Callahan, J. M. Drake, C. Y. Huang, S. W. James, B. A. Zinder, and W. Zhang. 2008. Pandora’s box contained bait: the global problem of introduced earthworms. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 39:593-613.

Hendry, G. M. 1965. Commercial baitfish statistics for the Kapuskasing District, fiscal year 1964 - Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kapuskasing, Ontario. 2 p.

Hildebrandt-Young and Associates. 1981. Profile of the baitfish industry in northwestern Ontario. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Kenora, Ontario. 145 p.

Holder, A. S. 1964. Report on the commercial baitfish industry for the Lake Simcoe District in Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sutton, Ontario. 4 p.

Hughson, D. R. 1965. The 1964 Sudbury District baitfish industry. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sudbury, Ontario. 8 p.

Hughson, D. R. 1967. The Sudbury District baitfish industry, 1966. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sudbury, Ontario. 8 p.

Hughson, D. R. 1968. The Sudbury District baitfish industry, 1967. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sudbury, Ontario. 6 p.

Hughson, D. R. 1970. The Sudbury District baitfish industry, 1969. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sudbury, Ontario. 7 p.

Hughson, D. R. 1971. The Sudbury District baitfish report, 1970. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sudbury, Ontario. 7 p.

Huner, J. V. 1997. The crayfish industry in North America. Fisheries 22:28-31.

Irvine, R. L. 1965. 1964 annual baitfish report for the Kemptville District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kemptville, Ontario. 2 p.

Irvine, R. L. 1966. 1965 annual baitfish report for the Kemptville District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kemptville, Ontario 1 p.

Jackson, D. A. and H. H. Harvey. 1977. Qualitative and quantitative sampling of lake fish communities. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 54:2807-2813.

Jansen, W., N. Geard, T. Mosindy, G. Olson, and M. Turner. 2009. Relative abundance and habitat association of three crayfish (Orconectes virilise, O. rusticus, and O. immunis) near an invasion front of O. rusticus, and long term changes in their distribution in Lake of the Woods, Canada. Aquatic Invasions 4:627-649.

Kapuscinski, K. L., J. M. Farrell, and M. A. Wilkinson. 2012. First report of abundant rudd populations in North America. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 32:82- 86.

Keller, R. P., A. N. Cox, C. Van Loon, D. M. Lodge, L. Herborg, and J. Rothlisberger. 2007. From bait shops to the forest floor: earthworm use and disposal by anglers. American Midland Naturalist 158:321-328.

Kerfoot, W. C., F. Yousef, M. M. Holmeier, R. P. Maki, S. T. Jarnagin and J. H. Churchill. 2011. Temperature, recreational fishing and dipause egg collections: dispersal of spiny water flea (Bythotrephes longimnanus). Biological Invasions 13:2513-2531.

Kerr, S. J., C. S. Brousseau, and M. Muschett. 2005. Invasive aquatic species in Ontario: a review and analysis of potential pathways for introduction. Fisheries 30:21-30.

Kidd, A. 2004. Bait frogs as vectors: a look at the potential spread of an infectious disease, Ranavirus, through the bait industry. Honours Thesis. Trent University. Peterborough, Ontario.

Kircheis, F. W. 1998. Species composition and economic value of Maine’s winter baitfish industry. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 18:175-180.

Lambert, R. S. and P. Pross. 1967. Renewing nature’s wealth – a centennial history of the public management of lands, forests, and wildlife in Ontario, 1763-1967. Hunter Rose Company. Toronto, Ontario. 630 p.

Larimore, R. W. 1954. Minnow productivity in a small Illinois stream. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 84:110-116.

Lewis, S. E. 2012. Status report of the commercial bait industry in Ontario, 206-2010. Fisheries Policy Section, Biodiversity Branch. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 68 p.

Litvak, M. K. and N. E. Mandrak. 1993. Ecology of freshwater baitfish use in Canada and the United States. Fisheries 18:6-13.

Litvak, M. K. and N. E. Mandrak. 2000. Baitfish trade as a vector of aquatic introductions. p. 163-180 In R. Claudi and J. H. Leach [eds.]. Nonindigenous freshwater organisms: vectors, biology and impacts. Lewis Publishers. Boca Raton, Florida.

Lodge, D. M., C. A. Taylor, D. M. Holdich, and J. Skurtal. 2000. Reducing impacts of exotic crayfish introductions. Fisheries 25:21-23.

Love, G. F. 1969. Baitfish report for the 1968 season in the North Bay District. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. North Bay, Ontario. 7 p.

Lovello, T. J. and J. R. Stauffer. 1993. The retail baitfish industry in Pennsylvania: a source of introduced species. Journal of the Pennsylvania Academy of Science 67:13-15.

Lowry, M., A. Steffe, and D. Williams. 2006. Relationships between bait collection, bait type, and catch: a comparison of the NSW trailer-boat and gamefish-tournament fisheries. Fisheries Research 78:266-275.

Ludwig, H. R. and J. A. Leitch. 1996. Interbasin transfer of aquatic biota via anglers’ bait buckets. Fisheries 21:14-18.

Manitoba Water Stewardship. 2009. 2008-09 Annual Report. Winnipeg, Manitoba. 113 p. Manwell, R. 1997. Angling for wigglers, worms, and hoppers. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Madison, Wisconsin.

Marcogliese, D. J. 2008. First report of the Asian fish tapeworm in the Great Lakes. Journal of Great Lakes Research 34:566-569.

Marcus, H. C. 1934. The fate of our forage fish. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 64:93-96.

Masson, W. T., R. W. Rottmann, and J. F. Dequine. 1992. Culture of earthworms for bait or fish food. Circular 1053. Department of Fisheries and Agricultural Science. University of Florida. Gainesville, Florida. 4 p.

McNee, J. D. 1966. Report on eastern Ontario baitfish industry, 1966. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Westport, Ontario.

McNee, J. D. 1971. Culture of golden shiner minnows at Westport Pond Station. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Westport, Ontario.

Meronek, T. G., F. A. Copes, and D. W. Coble. 1995. A summary of bait regulations in the north central United States. Fisheries 20(11):16-23.

Meronek, T. G., F. A. Copes, and D. W. Coble. 1997. A survey of the bait industry in the northcentral region of the United States. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 17:703-711.

Miller, J. 1970. Experimental use of baitfish traps in the St. Lawrence River. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Kemptville, Ontario. 4 p.

Mohr, L. C. 1985. Experimental trap nets for commercial baitfish. Northwestern Ontario Commercial Baitfishermen’s Association. Thunder Bay, Ontario. 20 p.

Mohr, L. C. 1986. Experimental enhancement of the commercial baitfish industry in northwestern Ontario. Northwestern Ontario Commercial Baitfisherman’s Association. Thunder Bay, Ontario. 84 p.

Momot, W. T. 1991. Potential for exploitation of freshwater crayfish in coolwater systems: management guidelines and issues. Fisheries 16:14-21.

Mulligan, D. A. 1960. the Sudbury commercial baitfish industry in 1959. p. 17-22 In Resource Management Report No. 61. Fish and Wildlife Branch. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Toronto, Ontario.

Mulligan, D. A.. 1962. A review of Sudbury’s baitfish industry, 1959-1961. Ontario Department of Lands and Forests. Sudbury, Ontario. 8 p.

Murray, J. A. and D. M. Lodge. 2007. As strong as the weakest link: state and provincial policy on invasive species. Presentation at the 50th Annual Conference of the International Association of Great Lakes Research. University Park, Pennsylvania.

Nadeau, D. 2012. Use of baitfish in Québec. Presentation to the Ottawa River Management Group. April 3, 2012. Pembroke, Ontario.