Darkling beetle control in poultry barns

Learn about the darkling beetle and how to control this pest in poultry barns. This technical information is for Ontario commercial poultry producers.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published November 2016

Introduction

Alphitobius diaperinus, also known as the darkling beetle, is one of the most common pests found in poultry barns. The darkling beetle goes by many other names, including:

- lesser meal worm

- litter beetle

- shining black wheat beetle

- black fungus beetle

This beetle traditionally consumes grain, however, poultry barns have provided an ideal environment for it to flourish, as it can survive on spilled feed and manure underneath feed lines. While inhabiting poultry barns, the darkling beetle poses various economic and biosecurity challenges to farmers across Ontario and most of North America. This factsheet will describe the lifecycle of the darkling beetle and discuss control options.

Biology

The success of this insect's life cycle is dependent on temperature, relative humidity, litter moisture and food availability. The life cycles range anywhere from 2 months to 400 days. During this time, females can lay an average of five eggs per day in their reproductive prime.

Considering many poultry barns are home to tens of millions of darkling beetles at a time, the reproductive potential of this insect is astounding if conditions are optimal. The highest hatchability of darkling beetle eggs is possible when barn conditions are 30°C and 90% relative humidity.

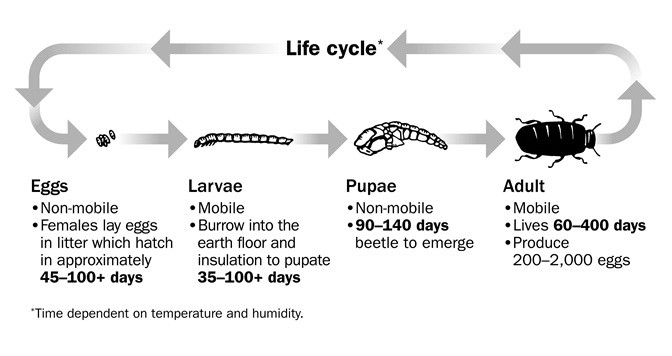

After hatching, the beetles can remain in the larval stage for up to 133 days if conditions are less than ideal. However, in optimal conditions a new adult darkling beetle can be produced as early as 29 days after an egg is laid. The adults can reproduce almost immediately after emerging. The adult beetle emerges from the pupa with a shiny red shell that changes to shiny brown or black in colour. The pupae are approximately 6 mm long. The larvae (also called mealworms or grubs) can grow to 1 cm in length before they pupate. Figure 1 describes the life cycle of the darkling beetle.

At some point during the poultry flock cycle, beetle larvae will begin to seek sites to pupate (including small cracks in walls, dirt floors and even underneath cement floors), and re-emerge at a later point, which could coincide with a succeeding flock. When birds are shipped out and the barn is empty, adult beetles will seek shelter in walls and under the floors. They too will re-emerge.

During cold weather, darkling beetles can undergo "supercooling," where their body fluids resist freezing, allowing this tropical beetle to survive in spite of the cold. Dissolved sugars in the beetle's hemolymph (their blood) allow beetles to survive long winter months as their metabolism runs at a much slower rate. It is common to see the heaviest infestations of darkling beetles in the fall as they seek shelter and warmth as external temperatures fall. If they do not find these conditions, they may survive in a hibernation state.

Economic impact

Darkling beetles cause structural damage to insulation when they burrow into walls to pupate. Such damage can decrease the insulating ability of poultry barns. By burrowing through materials such as styrofoam, the beetles can decrease the effectiveness of insulation by as much as 30%. A US study showed severe insulation deterioration from darkling beetles can result in as much as a 67% increase in energy costs.

Biosecurity impact

Darkling beetles are known vectors of 60 or more diseases that poultry are susceptible to, such as:

- Newcastle disease

- avian influenza

- Marek's disease

- infectious bursal disease

- Salmonella spp.

- 26 pathogenic types of E. coli

- Eimeria spp.

- Aspergillus

- parasites such as coccidiosis and round worm

Both adult and larval darkling beetles can harbour disease, carrying pathogens in their gut and on their bodies. Darkling beetles can also serve as an intermediate host for poultry tapeworms. Darkling beetles can remain positive for E. coli for up to 12 days, and Salmonella for up to 28 days. These time periods are sufficient enough to allow infection of a subsequent flock. Infected larvae can become infected adults.

Transmission of Salmonella from darkling beetles to young chicks has been well documented. These chicks can then spread the bacteria to others. Birds can become infected with Salmonella after consuming a single contaminated beetle.

Flock performance impact

In addition to disease challenges, darkling beetles can decrease flock performance through other means. As these beetles live in and around feed lines and feed pans, chicks and poults may consume them. Often, young birds choose to feed on darkling beetles first and feedstuff second. This fills their gut volume with indigestible beetle shells and can cause distress to the birds when they defecate (Figure 2).

In severe infestations, if these beetles cannot find enough moisture in their environment when humidity in the barn is low, they have been known to bite birds around their vents and feather follicles. This can cause tissue damage and infection. Lesions from darkling beetle attacks can look similar to skin leucosis.

Human impact

People that are continuously exposed to high numbers of darkling beetles can develop allergies. Neighbourhood relations could also be jeopardized in areas with an infestation of darkling beetles, as the beetles can remain in the manure when it is spread onto cropland. Being nocturnal and attracted to both light and heat, these beetles can fly or crawl out of the fields towards adjacent residential areas.

Control methods

There are various chemical, cultural and biological ways to control darkling beetle populations. These insects require a special level of patience, as it can take over a year to bring the population under control. It is unlikely farmers will ever be able to fully eliminate this beetle once it has established itself.

Used appropriately, chemical insecticides are a valuable tool when dealing with darkling beetles. Proper chemical insecticide use requires a thorough understanding of the insect's biology (behaviour, seasonality, life cycle, etc.). The farmer must also follow an effective insecticide rotation program to avoid or delay the development of resistance. Most importantly, farmers must follow application and dosage directions as outlined on the product label. More information about a specific insecticide can be found online at the Pest Management Regulatory Agency's label search service.

Cultural strategies involve conscientious management to minimize the darkling beetle population and limit potential impacts. An example of a cultural strategy is taking steps to minimize litter moisture. This includes eliminating water line leaks and improving ventilation to reduce the success of darkling beetle reproduction in the barn. Removing litter between flocks can also help to reduce beetle build up. Avoid equipment sharing between neighbours and barns to prevent mechanical transmission of beetles.

Biological control methods for darkling beetles generally has limited success, though there are some exceptions. Predatory insects, parasitoids and nematodes are not commercially viable options for most farmers. Diatomaceous earth (silica sand) is made up of tiny, sharp diatoms that, when the insect crawls through, will compromise the beetle's waxy cuticle. This leaves them vulnerable to desiccation and infection. Since the beetles need to crawl through it to be effective, diatomaceous earth should be spread where there is high beetle traffic on the floor along walls and posts, and cracks in the cement. It is important that these areas remain dry for the diatomaceous earth to remain effective.

The biological agent that seems to have the most promise against darkling beetles is the fungal pathogen Beauveria bassiana. This fungus infects both juvenile and adult stages of the beetle. The spore of the fungus will adhere to the insect and germinate, with hyphae extending into the body cavity causing death.

Conclusion

The darkling beetle is a prominent pest in the Ontario poultry industry, with many potentially negative impacts. Farmers must be flexible and adaptable, using a combined approach of chemical and alternative control methods. This approach, supported by a thorough understanding of the insect's behaviour and biology, will provide the highest amount of success when controlling darkling beetle populations.

References

Boozer, W. (2008). Insecticide susceptibility of the adult darkling beetle, Alphitobius diaperinus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): topical treatment with bifenthrin, imidacloprid, and spinosad. University of Georgia.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of:

- Jim Skinner of Terregena

- Dr. Simon Lachance of the University of Guelph, Alfred Campus

- Marc LaLonde and George Jeffery of Vetoquinol

This factsheet was originally written by Al Dam, Provincial Poultry Specialist and Kathleen Taylor, Poultry Research Technician, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Guelph.

Accessible description:

Life Cycle*

Eggs

- non-mobile

- females lay eggs in litter which hatch in approximately, 45-100+ days

Larvae

- mobile

- burrow into the earth floor and insulation to pupate, 35-100+ days

Pupae

- non-mobile

- 90-140 days beetle to emerge

Adult

- mobile

- lives 60-400 days

- produces 200-2,000 eggs

*Time dependant on temperature and humidity.