European crane fly

Learn about identification, biology, monitoring, damage and management of European crane fly.

Introduction

The European crane fly, Tipula paludosa Meigen, is a native of Eurasia. It has traditionally been a pest of turf in areas with a maritime climate in North America.

The first reported appearance of this insect in Canada was in 1955 on Cape Breton Island. The first reports from western Canada were from Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1965.

North American distribution of the European crane fly was limited to the eastern maritime and western provinces of Canada (Nova Scotia and British Columbia) and the western coast of the U.S. (Washington State and Oregon), but in 1996 and 1997, there were several reports of the larvae (leatherjackets) causing damage in turf in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton areas.

The first report of their presence in Ontario came in 1998, when they were identified as European crane fly (Tipula paludosa Meigen). They are now found throughout southwestern, central and parts of eastern Ontario, as well as in areas of New York State bordering Ontario, since 2004, and areas of Michigan bordering Ontario, since 2005.

Leatherjackets cause damage in turf and pasture grasses and some damage in fruit, vegetables and field crops.

Description

European crane fly adults resemble large mosquitoes (Figure 1). They range in length from 1.5–2.5 cm and have a greyish-brown body. Adult crane flies have two narrow wings and very long, slender brown legs. Unlike mosquitoes, they do not bite and are relatively weak flyers.

Eggs are laid near the soil surface to a depth of 1 cm and are black, shiny and oval in shape, roughly 1 mm long.

The larvae of the European crane fly are known as leatherjackets. They are light grey to greenish-brown with irregular black specks. Leatherjackets are cylindrical but taper slightly at both ends and are legless. Larvae mature through four developmental instars. They range in size from 0.5 cm in length in the first instar to 3–4 cm at maturity (Figure 2).

The pupa is formed inside the last instar cuticle, which is called a puparium. They are brown and spiny and 3–4 cm in length (Figure 3). The adult emerges, leaving the puparium behind, visible on closely mown turf.

Biology

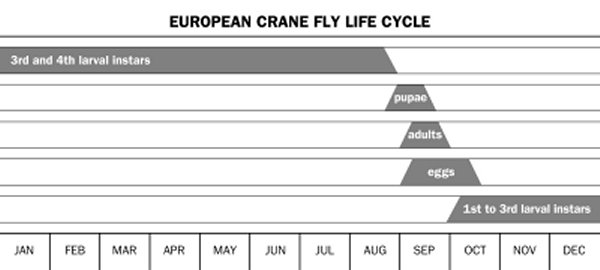

European crane flies complete one generation per year in Ontario (Figure 5). Adults emerge throughout September, depending on the location within Ontario. Adult females will mate and lay their eggs within 24 hours of emerging. Eggs can be present in the soil from the beginning of September until the middle of October, laid on the surface and down to 1 cm deep in the soil. One female can lay 200–300 eggs. Eggs are very susceptible to drying out and require moisture to hatch. Egg hatch occurs in 10–14 days.

Larvae are present from the beginning of October until the end of August the following year. They pass through 3–4 instar moults in the fall and generally overwinter as third or fourth instars. In the fall and early spring, larvae feed in the top of the thatch and on the leaf blades. Later in the spring, the larger instars reside in the soil (1–3 cm deep) during the day and feed on the grass blades at night.

Feeding by the fourth instar larvae causes the majority of the damage in the spring. Heavy spring rains often force the larvae to the surface of the turf and onto hard surfaces such as driveways and sidewalks (Figure 4).

By mid-June, the larvae cease feeding, move down in the soil (3–5 cm) and remain in a non-feeding stage until pupation. Pupation occurs from late August through early-to-mid-September, when the pupae wriggle to the top of the soil in the late night to early morning and the adults emerge. The empty pupal cases look like small twigs protruding from closely mowed turf (Figure 6).

Damage

Leatherjackets feed primarily on turf on home lawns, golf courses, sod farms and pasture grasses. They feed during the day at or below the surface of the turf on root hairs, roots and crowns. On damp warm nights, they come up to the surface of the turf and eat stems and grass blades. Damage to turf shows as yellow spots, thinning to bare patches. Peak damage in Ontario occurs in May (Figure 7). Secondary pests such as skunks and starlings can also damage the turf: skunks dig up small patches of turf in search of leatherjackets, and birds peck them out of turf during May and June (Figure 8).

Monitoring

Adults

Adults congregate on the sides of buildings, sliding doors, screens and fences, where they can be counted. Larval infestations are likely to occur where there are adult populations.

Empty pupal cases seen on closely mown turf in the morning are evidence of the presence of pupae. Note where crows are foraging to help pinpoint areas with high pupae populations.

Larvae

If signs of bird predation or turf injury suggest leatherjacket presence, the best method for detecting leatherjackets is to take a cup changer-sized plug of turf and tear it apart, looking through the leaf blades, thatch and soil for leatherjackets. Larval thresholds have not been determined for Ontario.

Management

There are several cultural methods that help minimize leatherjacket damage.

The first is to maintain a healthy turf stand, through proper mowing and fertility.

Secondly, adult crane flies prefer to lay their eggs in moist soils. Improving drainage will help dry out soils and deter females from laying eggs. Newly hatched larvae also have poor survival in dry soils.

Many leatherjackets die in the spring when heavy rains force them from the turf onto hard surfaces, where they will dry out and perish.

Leatherjackets also suffer high mortality from bird predation in the spring.

Control products are available for excepted uses on golf courses and sod farms; direct these toward the leatherjacket stage. Make preventive applications in the fall after peak egglaying. Make early curative insecticide applications for leatherjackets in October before the soil freezes up, when the larvae are feeding close to the surface, are small and have not yet caused significant damage. Make curative applications in the spring based on scouting or direct observations of damage.

If preventative applications are applied in the fall, applications in the spring may not be necessary. However, applications can be made in the spring when damage from feeding first starts to appear. Insecticide applications against adults are typically ineffective, as the adults do not feed.

See OMAFRA Publication 384, Turfgrass Management Recommendations, for information on control products and rates. For home lawns and other non-excepted uses, applying the entomopathogenic nematode species Steinernema carpocapsae in the spring or a 50/50 mixture of Steinerenema feltieae and Heterorhabditis bacteriophora in the fall can reduce leatherjacket populations in Ontario.