Greenwater Provincial Park Management Plan

This document provides policy direction for the protection, development and management of Greenwater Provincial Park and its resources.

Minister’s approval statement

Greenwater Provincial Park, located in the Great Clay Belt of Northeastern Ontario, is an area of high natural and recreational value. Established in 1957, Greenwater has served as a popular recreation area by providing a variety of opportunities to both tourists and local residents. The park serves as a stopover campground for visitors taking the Polar Bear Express to Moosonee on James Bay and as a destination campground for those who enjoy the tranquil setting for which the park is known.

While ensuring the provision for year-round recreational activities, the master plan emphasizes the protection of significant natural features. At this time, would like to extend my gratitude for the valuable commentary provided by individuals and groups during the public participation program and look forward to your continued interest inthe planning of other provincial parks throughout Ontario.

In accordance with The Provincial Parks Act, Sections 1d and 7a, I am pleased to approve Greenwater Provincial Park Master Plan as the official policy for the future development and management of the park.

Honourable James A.C. Auld

Minister

January, 1979

Planning participants

Team members

A. Currie - Park Planner, Northern Regional Office

B. Hutchinson - Field Services Supervisor, Cochrane District

L. Ladoucer - Park Superintendent, Greenwater Provincial Park, Cochrane District

R. Macnaughton - Unit Forester Cochrane District

R. W. Stewart - Biologist, Cochrane District

B. Therriault - Outdoor Recreation Supervisor, Cochrane District

Consultants

Diane Culm - Biologist, Cochrane District

Ed Frey - Geologist, Northern Regional Office

G. O’Reilly - Visitor Services Programmer, Northern Regional Office

Master plan highlights

Greenwater Provincial Park, located 34 km northwest of Cochrane has been open to the public for the past 21 years and has served as a popular recreation area for local and Ontario residents.

Established in 1957 and classified as a natural environment park, Greenwater… named for the peculiar green colour of one of its 26 lakes…provides good opportunities for brook trout, rainbow trout, lake trout, northern pike, yellow pickerel and yellow perch fishing.

All types of outboard motors are not presently allowed on park lakes except electric motors of 5 hp or less. This latter exemption is still pending regulation.

Although hunting has been prohibited in the park, hunters use the park as a stopover or for hunting adjacent to the park.

The 5,350 ha park is centered on a long 61 m high ridge. This ridge, or esker, was once the bed of a river which flowed within glacial ice less than 10,000 years ago during the melting period.

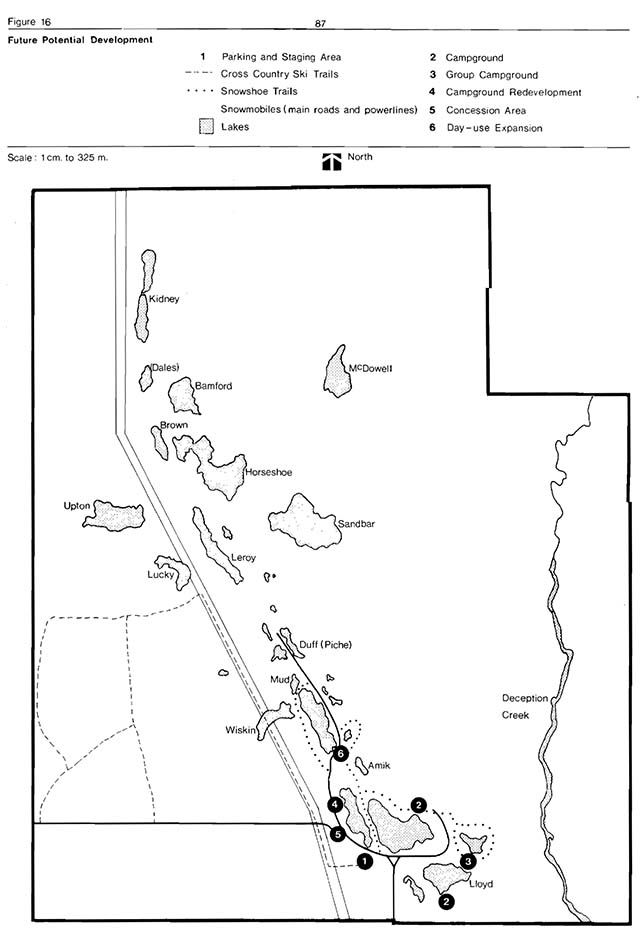

Greenwater presently has 104 campsites and a potential for double the capacity as demands increase and funds permit. The recent addition of the Deception Creek area to the park has increased opportunities for canoeing, wildlife viewing, as well as the other facilities offered i.e. scenic hiking, interpretive trails and outdoor education programs.

Maintenance of the environmental integrity of the park is a major objective of this plan and is reflected in the zoning, policies and management strategies outlined in this plan.

Preface

Glaciers and man have been two of the most significant forces to shape the landscape of Northeastern Ontario.

Glacial and postglacial events, approximately 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, left prominent esker systems, clay till, and lacustrine clay plains throughout the north.

In more recent times, particularly within the last 75 years, man entered the Northeastern Ontario scene as a settler and entrepreneur. These pioneers came from many parts of Canada and the world; many to stay, some to die and others to leave, leaving behind only an imprint of their occupation.

Today, in Northern Ontario, it is not uncommon to find a provincial park occupying and reserving an area of glacial disposition and/or an area of past human occupation. Greenwater Provincial Park is a case where a park includes an esker system and remnants of past agricultural and logging activities.

1.0 Introduction

The Greenwater Provincial Park Master Plan describes the biophysical, cultural and recreational resources and identifies the goal and objectives for the park. It also establishes comprehensive policies for the planning, preservation, development and management of park resources. Resource management plans for the parkare also included in this plan.

2.0 Regional setting

2.1 Location

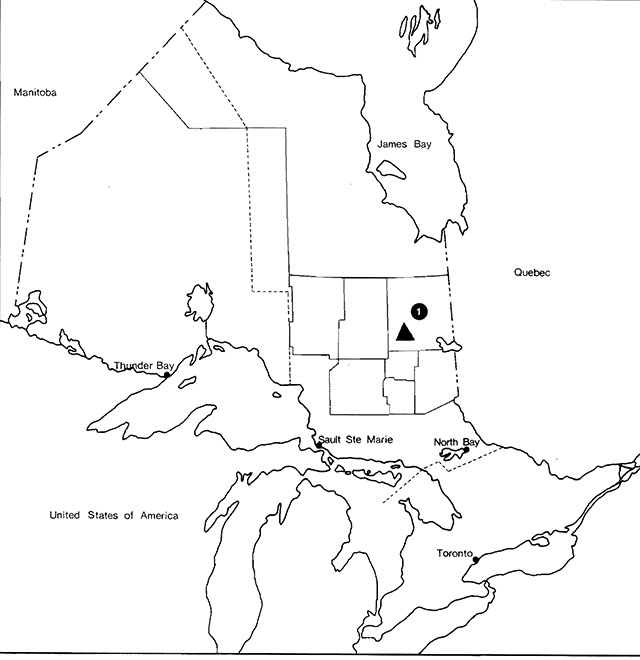

Greenwater Provincial Park (49°11’N - 49°15’N and 81°15’W - 81°20’W) is located in the Cochrane District (Figure 1) of the Northern Administrative Region, Ministry of Natural Resources and the Northeastern Planning Region as defined by the Strategic Land Use Plan for Northeastern Ontario (S.L.U.P., 1977). The park is located in the Great Clay Belt of Northern Ontario, 33.8 km northwest of Cochrane and 802 km northwest of Toronto. Greenwater Provincial Park encompasses an area of 5,350 ha.

2.2 Regional climate

Greenwater is situated in the Northern Clay Belt climatic region (Chapman and Thomas, 1968). This climatic region has been identified as modified continental. The Great Lakes and Hudson Bay modify weather conditions slightly. In summer, warm humid air masses from the south alternate with cooler drier air from the north to produce periods of clear, dry weather followed by warmer humid weather. In winter, there are often days of snow squalls and high winds alternating with clear, cold, dry weather. On the average, summer days in this region receive one hour more of daylight than those of Southern Ontario.

Enlarge Figure 1: Northern administrative and northeastern planning regions (PDF)

2.3 Regional physiography

The southern half of the Northern Administrative Region is underlain by the Precambrian igneous rock of the Canadian Shield, and the northern half by the Paleozoic sedimentary bedrock of the Hudson Bay Lowlands. Greenwater Provincial Park is located on the northern edge of the shield in the Great Clay Belt. The clay belt itself demarks an area once covered by pro-glacial Lake Barlow-Ojibway. Unconsolidated Quaternary deposits can be found overlying much of the region including most of the park area. These deposits range from clay to till cover. Prominent in a few locations throughout the north are glaciofluvial features. One such feature, an esker complex, bisects the parks.

2.4 Regional vegetation

The major forest region found in the Ministry of Natural Resources Northern Administrative Region, including Greenwater Provincial Park, is the Boreal Forest (Rowe, 1972). Black spruce, tamarack, aspen, jack pine and white birch are the dominant species within this area. Black spruce is the predominant species in the low-lying areas. Mixed-wood stands of aspen, white birch, balsam fir and white spruce occupy glacial ridges and associated uplands. Jack pine predominates on the sand plains.

2.5 Crown land recreation

The role of Crown land in the north cannot be under-estimated. It is from Crown land that most of the north’s timber resources come and it is on Crown land that 47.1 percent of all outdoor recreation occasions take place (Crown Land Recreation Study, 1977). In the Northern Administrative Region, there are 29,986,310 ha of Crown land which constitutes approximately 82 percent of the land base. In the Cochrane District there are 3,107,574 ha of Crown land and approximately 29,940 ha are park reserves and provincial parks.

2.6 Population

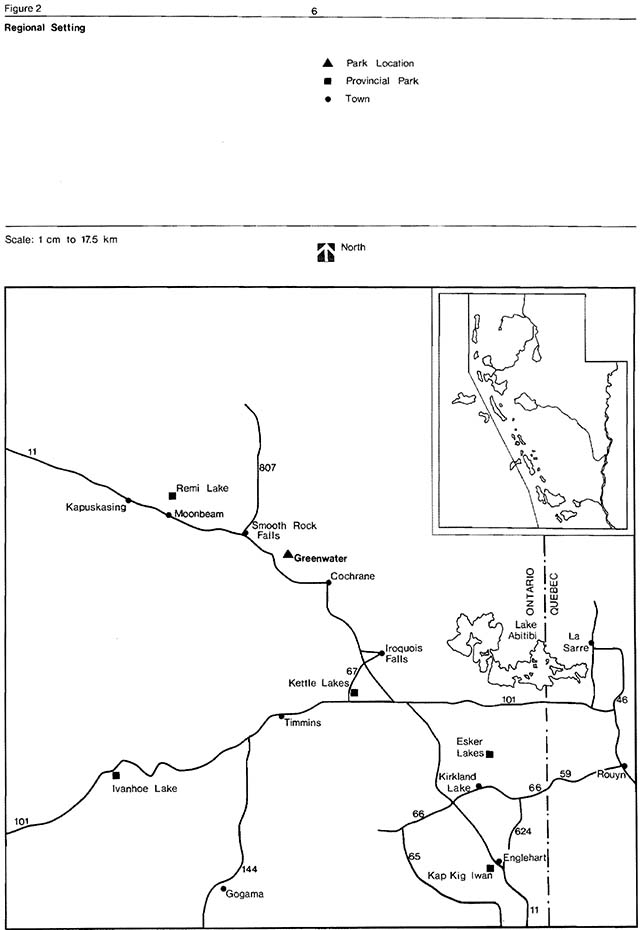

In 1976, the total population of the Cochrane Census Division was 96,825 (1976, Census of Canada). The Ministry of Natural Resources Northern Region has a slow growing economy and few non-resource oriented manufacturing industries. The major sources of employment in the region are forest and forest-based industries, mining and mine-based activities, tourism and agriculture. Commercial fishing and trapping provide employment on a seasonal or part-time basis. Secondary industries dependent on the mining and forestry industries include transportation and construction. Government services also play an important role in the economic base of the region. Major population centres in the vicinity of Greenwater include Cochrane, population 4,862; Iroquois Falls, 6,726; Smooth Rock Falls, 2,433; Kapuskasing, 12,694; and Timmins, 42,981. Approximately 1,300 people occupy the rural areas within 100 km of the park (Figure 2).

Enlarge Figure 2: Regional setting (PDF)

2.7 Access

Most of the small and some of the major transportation arteries in the North have been aligned according to major mineral deposits and forest production areas. The major traffic artery leading into the region is Highway 11 running north from Toronto through North Bay to Cochrane then west to Thunder Bay. Secondary traffic arteries include Highways 129 and 144 leading north from Thessalon and Sudbury respectively to Highway 101 linking Chapleau and Timmins to Highway 11.

Highway 66 and Highway 101 link the region to Quebec highways which in turn lead to most northern and southern population centres within that province. Highway 807 runs north from Smooth Rock Falls 65 km to Fraserdale.

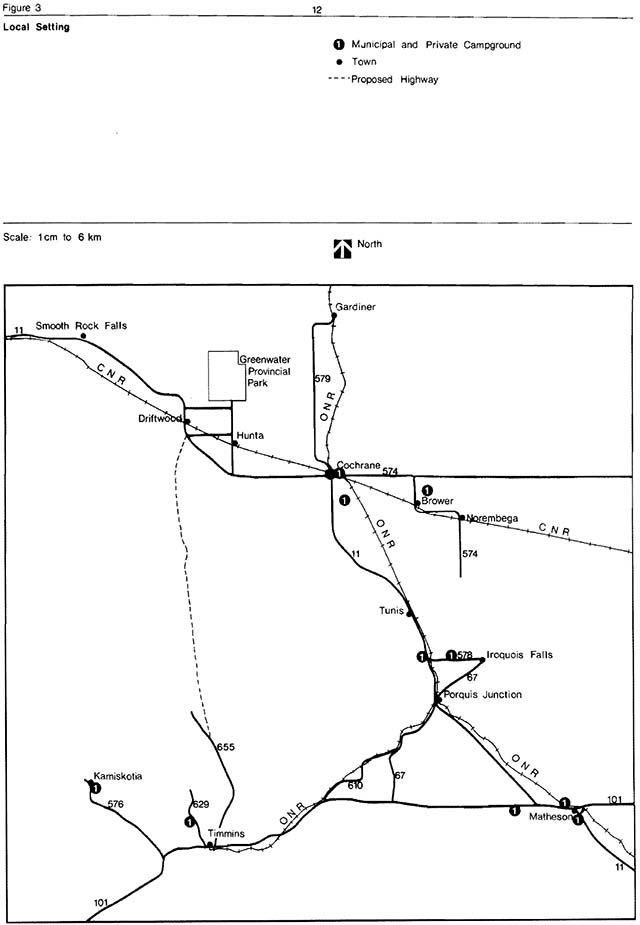

The main access to Greenwater Provincial Park is Highway 11 west from Cochrane for 19.3 km and then 14.5 km north along the Clute and Calder township boundary road. A new highway is presently under construction from Timmins which will intersect Highway 11 at Driftwood (24 km west of Cochrane). This highway will provide easier access to the park from Timmins and should result in a substantial increase in the utilization of Greenwater Provincial Park. The nearest railway station is located in Cochrane. The Canadian National Railway runs from Quebec City through LaSarre and Cochrane west to Nakina. The Ontario Northland runs north from Toronto through Cochrane to Moosonee. Ontario Northland bus services also link Cochrane with most Northern and Southern Ontario centres. A small municipal airstrip is located 3.2 km northeast of Cochrane.

3.0 Market analysis

3.1 Regional

The trends in recreation demand for the Northern Administrative Region, reveal a changing picture (Crown Land Recreation Study, 1978). Several factors which are contributing to these changes are:

- lower fertility rates;

- migration from Ontario;

- changes in the attractivity of Ontario as a tourist destination;

- increases in winter vacation trips; and

- increased energy costs.

Recent survey data

Another factor which appears to be affecting tourism in the north is the decrease in the average length of vacation trips taken by car. Since the Northern Region requires a long trip from the main market sources, the effects have been noticeable. Further trends have occurred particularly in the purpose of the vacation trips and types of experiences sought. In the latter case, it seems that vacationers are interested in spending time at vacation spots. The north has an additional factor which may affect tourism in the north is the age/sex factor. One could assume that older persons tend to travel south for recreation rather than north. If this is true, the older segment of the future population may adversely affect the growth of tourism in the Northern Region.

Given all of the above trends, tourism still remains a major industry in the north. The Northern Administrative Region offers a large number of both public and private campgrounds, private tourist establishments and vast amounts of Crown land. Approximately 327 commercial tourist establishments are located in the region. Most are located adjacent to major traffic arteries. Twenty licenced fly-in tourist outfitters operate within the region. For the touring public, 37 commercial tent and trailer campgrounds are available.

Currently, 17 provincial parks are situated in the Northern Administrative Region providing approximately 1,200 developed campsites. Five of these parks are situated along Highway 11. In addition to provincial parks there are 8 park reserves with an unestimated total development potential. As well, 123 access points and 46 designated canoe routes provide additional recreation opportunities in the Region.

Private recreation facilities also contribute to the total recreation supply. There are approximately 3,595 private cottages and 673 hunt and fish camps in the Northern Region.

3.2 Local

Thirteen municipal and private campgrounds are located within a 100 km radius of Greenwater Provincial Park (Table 1). Drury Park, a municipal park located in the Town of Cochrane, has a substantial influence on the visitation at Greenwater. Both Greenwater and Drury cater to the stopover tourist interested in taking the Polar Bear Express to Moosonee. However, a transient camper preference for Drury exists because of its proximity to train facilities. The actual influence on Greenwater of the remaining 12 camping areas is unknown (Figure 3).

Table 1: Municipal and private campgrounds within 100 km of Greenwater Provincial Park

| Highway Access | Name and Location | Area (Hectares) | Number of Campsites |

|---|---|---|---|

| #11 | Drury Park, Cochrane | 30 | 140 |

| #11 | Terry’s Campgrounds, 11.2 km south of Cochrane | 220 | 20 |

| #574 | Birchill Park Cabins | 4 | 10 |

| #101 | Perry Lake Hunt and Fish Lodge | 32 | 10 |

| #11 | Pull in Campground, 1.6 km south of Matheson | 11 | 5 |

| #101 | Reid Lake Campgrounds, 24 km west of Matheson | 2 | 25 |

| #11 | Vi-Mar Campgrounds, 3.2 km north of Matheson | 1 | 7 |

| #581 | Chalet Brunelle, 4.8 km north of Moonbeam 20 | 20 | 20 |

| #11 | Highway Beach, 8 km north of Porquis Junction | 121 | 90 |

| #629 | All Seasons Park, 8 km north of Highway 629 | 32 | 56 |

| #576 | Horseshoe Lake Park, Kamiskotia | 8 | 15 |

| #655 | Bigwater Park,Timmins | N/A | N/A |

| #11 | Pender’s Campground, Tunis | 1 | 10 |

Two provincial parks are located within a 100 km radius of Greenwater Provincial Park: Kettle Lakes and Remi Lake provincial parks. Both are classed as recreation parks according to the 1978 Classification of Provincial Parks in Ontario. Kettle Lakes is located on Highway 67, 40 km east of Timmins and 100 km from Greenwater. The main role of the park is to provide intensive recreation facilities for the local population of Timmins. Remi Lake Provincial Park is located 12.9 km north of Moonbeam off Highway 11. Remi Lake has assumed the role of serving local Kapuskasing residents. Greenwater is located midway between Kettle Lakes and Remi Lake provincial parks. Neither park attracts substantial visitors away from Greenwater. If anything, visitors from both Timmins and Kapuskasing are attracted to Greenwater because of its natural conditions and less intensive development.

Pierre-Montreuil Park Reserve is located 100 km northeast of Greenwater Provincial Park. This 16,211 ha reserve has a moderate potential for camping and water-based activities such as fishing, swimming and canoe-tripping. If Pierre-Montreuil becomes established as a provincial park, it may attract part of Greenwater’s local and nonlocal destination camper market.

Within a 100 km radius of Greenwater are situated six official access points: Sangster Lake, Deception Creek, Mistango Lake, Redsucker River, Departure Lake and Gardiner Ferry. These provide access to water and are, in many instances, heavily used by local fishermen and canoeists. All official access points are maintained by the Ministry of Natural Resources.

Enlarge figure 3: Local setting (PDF)

Two designated provincial canoe routes exist within the district: the Abitibi and Mattagami rivers. Both offer good backcountry travel opportunities.

Fishing opportunities in the Cochrane District are available for brook, lake and rainbow trout, yellow pickerel, sturgeon, whitefish and northern pike. Fly-in fishing is rated good to excellent.

Moose and bear hunting in the District is fair. The success of fly-in moose hunters is higher than in the more accessible areas. Waterfowl hunting is considered poor to fair in the area. Ruffed, spruce and occasionally sharp-tailed grouse are also available. A commercial pheasant farm approximately 6.4 km west of Cochrane offers fall hunting.

3.3 Other recreational opportunities

The Town of Cochrane offers a variety of interpretive opportunities for visitors. The Cochrane Railway and Pioneer museum and the Ministry of Natural Resources’ Interpretive Car, located east of the Ontario Northland Station, contain exhibits on trapping, mining, railways, wildfire, forestry, agriculture, human history of the frontier and an audio-visual program about Cochrane and the Moosonee area. The Cochrane plywood mill (Cochrane Enterprises Limited) offers guided tours of their plant.

The Polar Bear Express operated by Ontario Northland Railway runs from Cochrane to Moosonee. It is a popular train excursion with summer visitors. Points of interest along the route include: the Island Falls and Otter Rapids dams, native and historic settlements, the Abitibi and Moose rivers, the “Upside Down” bridge, and Moosonee and Moose Factory.

Many historical sites are found in the Cochrane area and some are marked with appropriate plaques (e.g. commemorating the founding of Cochrane, marking the 49th parallel, indicating the Niven survey line cut 70 years ago).

Iroquois Falls, located 48 km southeast of Cochrane, offers the Iroquois Falls Railway Museum and the Abitibi Paper Company’s Iroquois Falls Mill. The company has guided tours of a logging operation which show clear-cut and regenerated stands, forestry harvesting techniques and equipment, and the mill operation.

In the Timmins area, there are two mining tours offered: Pamour Mines and Texas Gulf concentrator and refineries.

3.4 Recreational needs

In 1973, the Northeastern Ontario Recreation Survey was conducted to determine the recreational needs of the 489,795 residents of Northeastern Ontario. To conduct this survey, Northeastern Ontario was subdivided into 40 service areas. From each service area, a representative sample was drawn. Most of the Cochrane District was included in service area 5. The survey found that 52.7 percent of the total participation in Northeastern Ontario was accounted for by outdoor recreation activities (i.e. hunting, fishing, bathing and picnicking). Structured recreation activities (i.e. team sports, cultural activities) accounted for 47.5 percent. It was found that 67.2 percent of outdoor recreation activities occurred on a daily basis instead of an extended period of one or more nights. Table 2 identifies the percent participation for Northeastern Ontario, the Northern Region, and the Cochrane service area for each of the 8 outdoor activities examined by the survey.

The most popular activities in Northeastern Ontario are nature appreciation, swimming, picnicking and fishing. Hunting, fishing, snowmobiling and bathing are the preferred activities in the Cochrane Service area. The high participation in hunting and fishing in the Cochrane area may reflect the high use of Crown land. Table 3 presents the percentage outdoor recreation participation by land use type for Northeastern Ontario, the Northern Region and the Cochrane service area.

While private land appears to accommodate the highest proportion of participation in Northeastern Ontario and the Northern Region (42.4 and 38.5 percent respectively), it is Crown land which receives the most use in the Cochrane area. Other service areas adjacent to Cochrane display a similar high use of Crown land.

The United States is the major non-resident tourist market for Northeastern Ontario (U.S. Auto Exit Study, 1969) followed by residents of Quebec. In 1969, it was estimated that 14 percent of all American visits to Ontario, greater than one day in duration, were destined for Northeastern Ontario. Of all the possible Ontario destination points, Northeastern Ontario ranked second. These American visitors identified hunting, fishing, camping and tenting as the reasons for their visit.

Table 2: Percent participation in outdoor recreation activities by regions and area

| Outdoor recreational activity | Northeastern Ontario | Northern Region | Cochrane Service Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hunting | 6.8 | 10.8 | 18.5 |

| Fishing | 14.3 | 17.0 | 17.7 |

| Boating | 9.7 | 10.8 | 7.3 |

| Nature Appreciation | 24.8 | 13.7 | 9.8 |

| Picnicking | 16.1 | 19.7 | 17.5 |

| Skiing | 3.4 | 2.4 | 0.7 |

| Snowmobiling | 7.7 | 10.2 | 17.1 |

| Bathing | 17.2 | 15.4 | 11.4 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Source: Northeastern Ontario Recreation Participation Survey, 1975

Table 3: Percent outdoor recreation participation by land use type

| Land use type | Northeastern Ontario | Northern Region | Cochrane Service Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private Land | 42.4 | 38.5 | 24.6 |

| Crown Land | 35.5 | 33.7 | 40.1 |

| Provincial Parks | 6.4 | 7.8 | 7.3 |

| Other Parks | 5.4 | 5.5 | - |

| Access Points | 10.2 | 14.6 | 28.0 |

| Total | 99.9 | 100.1 | 100.1 |

Source: Northeastern Ontario Recreation Participation Survey, 1975

4.0 The park

The Ontario provincial parks system, of which Greenwater Provincial Park is a component, makes a very distinctive contribution to recreation and conservation in Ontario.

The goal and objectives of the provincial parks system are:

Goals

To provide a variety of outdoor recreation opportunities, and to preserve provincially significant natural, cultural and recreation environments in a system of provincial parks.

Objectives

Protection: To protect provincially significant elements of the natural and cultural landscape of Ontario.

Recreation: To provide provincial park outdoor recreation opportunities ranging from high intensity day-use to low intensity wilderness experiences.

Heritage appreciation: To provide opportunities for exploration and appreciation of the outdoor natural and cultural heritage. of Ontario.

Tourism: To facilitate travel by residents of and visitors to Ontario who are discovering and experiencing the distinctive regions of the Province.

Greenwater Provincial Park contributes to all 4 objectives by providing a variety of recreational opportunities to both the local and non-local resident. Further, the boundaries of Greenwater provide. protection to a number of locally and regionally significant plant communities and geomorphological features. Greenwater also contributes to the heritage appreciation objective through interpretation of historical farming remnants located in the southwest corner of the park.

4.1 Legal status

Greenwater was officially designated a provincial park in 1957 by Ontario Regulation 144. It is classified as a Natural Environment Park under the 1967 Ontario Provincial Parks Classification System. In 1977, an additional 910 ha of the Deception Creek area was added to the east boundary of the park.

4.2 Park boundaries

The park encompasses parts of four townships. It includes the southeast section of Colquhoun Township, Concession -VI, Lots 1 to 8; the southwest corner of Leitch Township, Concession to IV, Lots 24 to 28 and Concession V and VI, Lots 27 and 28; the northeast corner of Calder Township, Concession XII, Lots 1 to 8; and the northwest corner of Clute Township, Concession XII, Lots 24 to 28. The total park area is 5,350 ha of which 210 ha is water.

4.3 Mineral exploration

Prior to the establishment of Greenwater, no prospecting or claims staking occurred within the park. A recent airborne geophysical survey by Shell Canada has delineated some anomalies adjacent to and within Greenwater Provincial Park. These anomalies appear to indicate the presence of base metal sulphide. The bedrock mineral potential of the Greenwater area is rated as medium to high.

An unsuccessful search for aggregate sources was conducted in 1955 in the southeast corner of the park. The esker within Greenwater has good gravel deposits, the remainder of the park is considered to have low aggregate potential.

4.4 Land disposition

No leased land or unauthorized buildings exist within the present park boundaries with the exception of one summer cottage under Land Use Permit, located on Deception Creek (Lot 24, Concession XII, Clute Township). Two patents exist which cover the southern section of the hydro lines belonging to Ontario Hydro (76.6 ha) and Abitibi Paper Company (5.7 ha). These lines parallel each other. The remainder of the power lines are established on Crown land covered by licence of occupation. Both lines predate the establishment of Greenwater Provincial Park. Greenwater abuts private land on most of its south boundary. The north, east and west boundaries abut Crown land.

4.5 Forest management

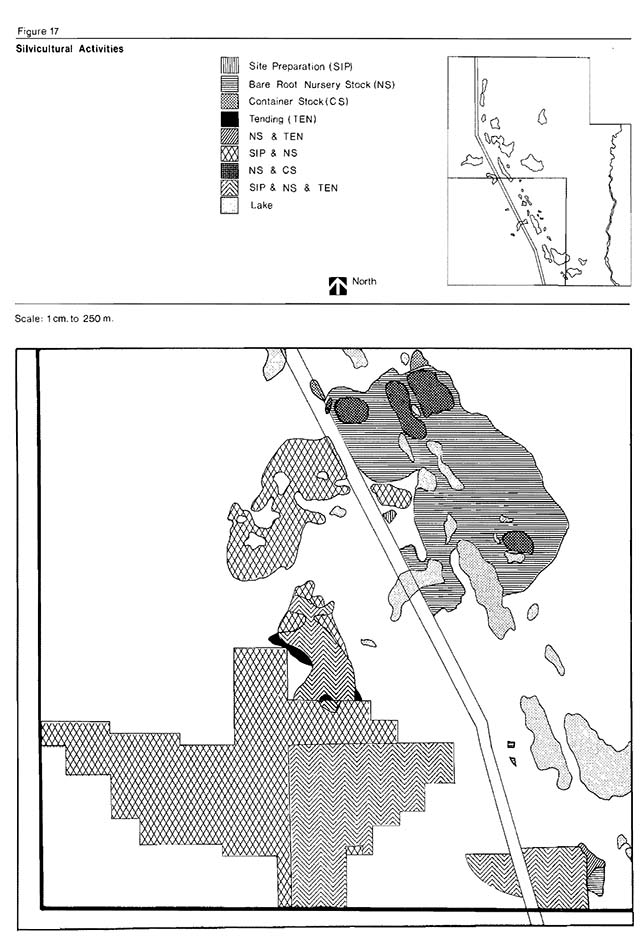

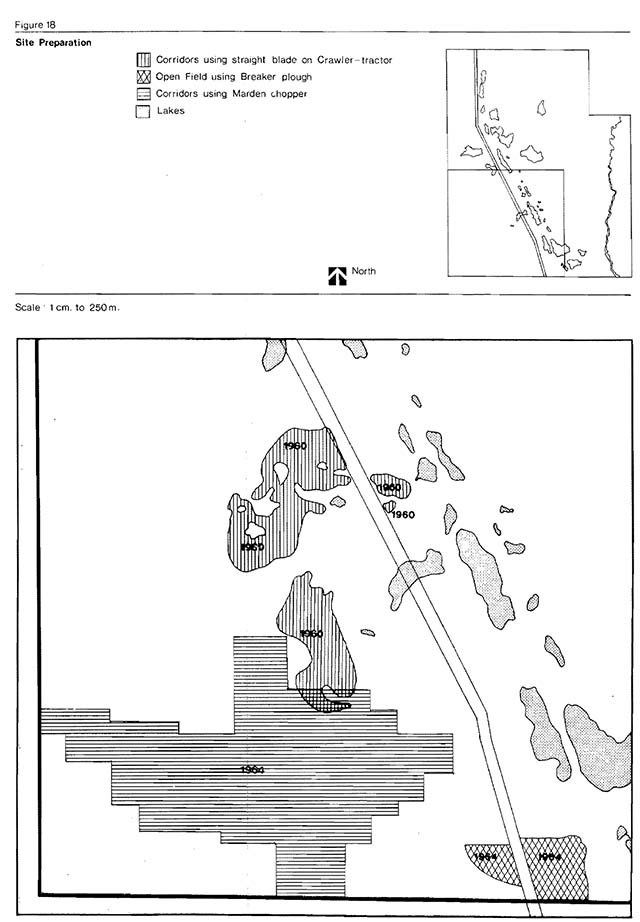

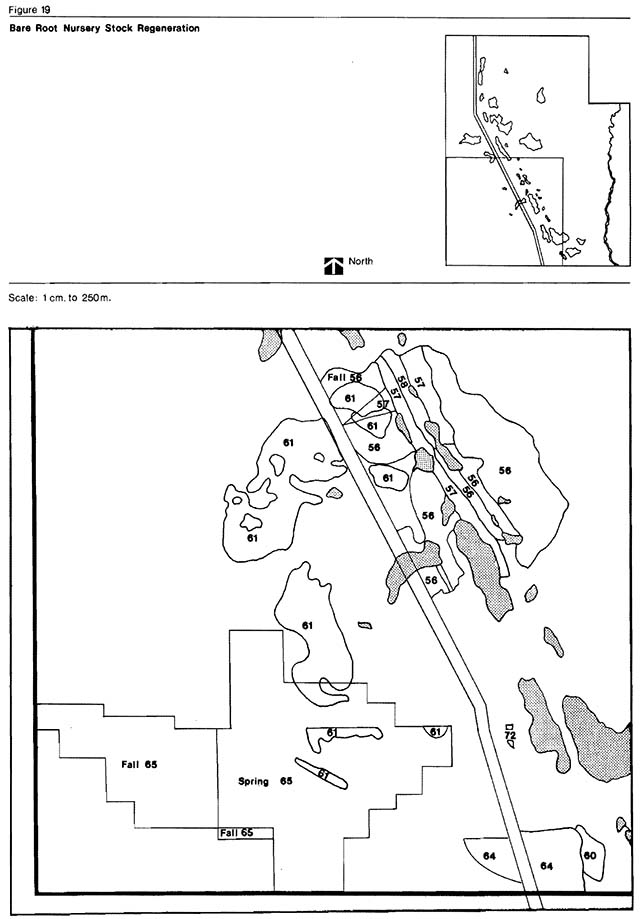

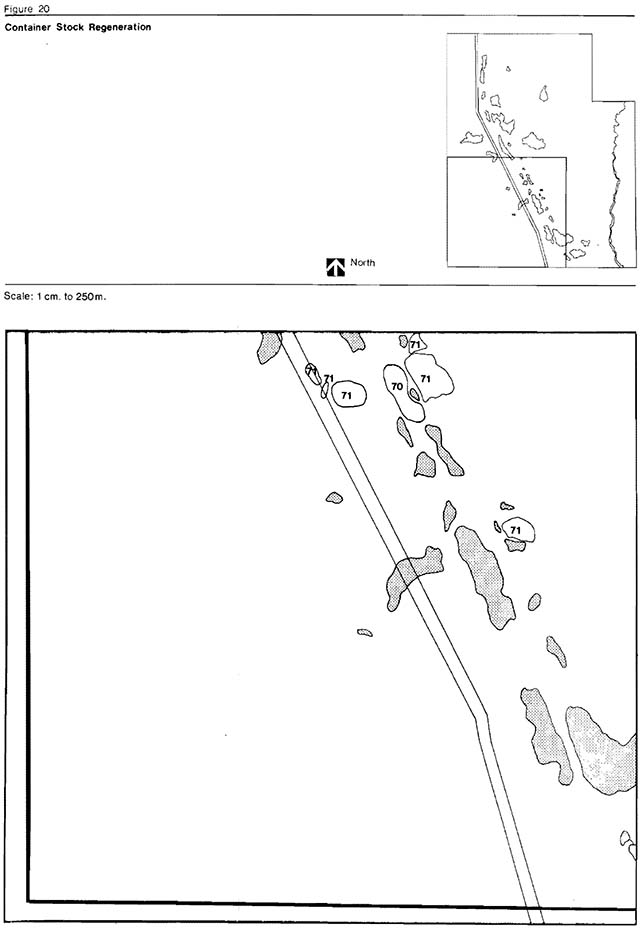

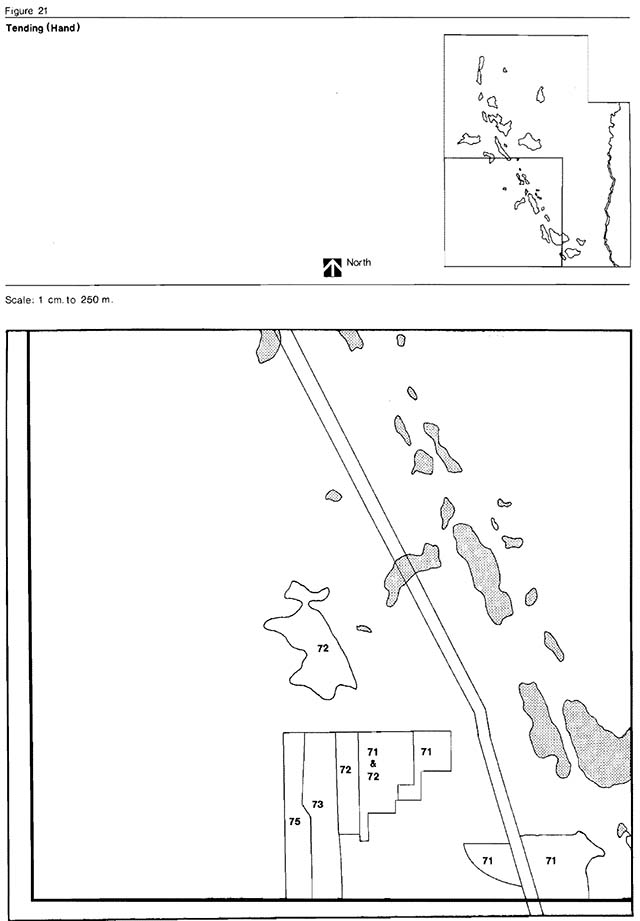

Before 1960, logging by clear-cut and selective-cut methods had a major influence affecting 50 to 60 percent of the park. An active silvicultural program has taken place in the park for the last 20 years. This program included tending of plantations which were planted in cut over, burned and agriculturally cleared land. Active timber harvesting is taking place immediately adjacent to the north, northwest and northeast boundaries of the park.

4.6 Wildlife management

Park policy has been to allow hunting north of the development zone (campgrounds and day-use areas) or one mile from any travelled road within the park. This was permitted because there was little or no conflict with the park users. Presently, 181 user-days are consumed annually by hunters.

A small captive flock of Giant Canada and Blue geese are located on Lloyd and Pike lakes each summer.

One registered trapline (PE-85) includes the park area. This trapline has been operated since 1936 with beaver as the major fur bearing species. An aerial survey of the trapline in 1972 located 64 live beaver colonies. From this count, an annual quota of 96 beaver was established.

4.7 Fish management

Most of the brook, lake and rainbow trout fishing is provided by a “put and delayed take” program. Native species include northern pike, yellow pickerel, yellow perch and a small population of native brook trout in Deception Creek.

Park and Green lakes were reclaimed to eliminate undesirable fish species in 1969 and 1975 respectively. A voluntary creel census was conducted on all of the park lakes from May 31 to December 31, 1976.

The park lakes have been a part of the Fish and Wildlife management program of the Cochrane District since 1950. At present, lake, brook and rainbow trout are planted on a rotational basis in seven of the park lakes. In 1976, two small experimental plantings of northern pike were introduced into Upton and Lucky lakes. The fisheries management plan for Greenwater emphasizes a put and delayed take trout fishery for several reasons: 1) the absence of natural trout spawning areas, 2) the good water qualities which are available for maintaining trout populations, 3) the lack of trout lakes in the Cochrane District, and 4) the need to provide a good recreational sports fishery for local residents and tourists.

4.8 Visitor services

A seasonal park naturalist conducts an interpretive program for the park visitors. Activities include young people’s programs, wilderness cook-out demonstrations and evening programs. The six hiking trails and one self-guiding interpretive trail (Green Trail) are popular with the park visitors. During 1977, 985 personal contacts and 2,456 facility contacts were made.

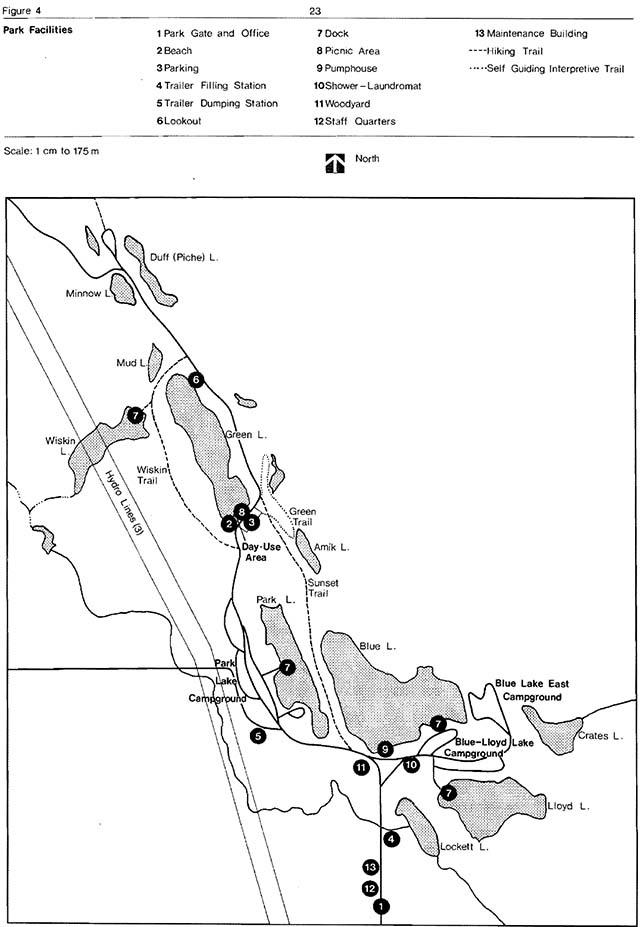

4.9 Park development

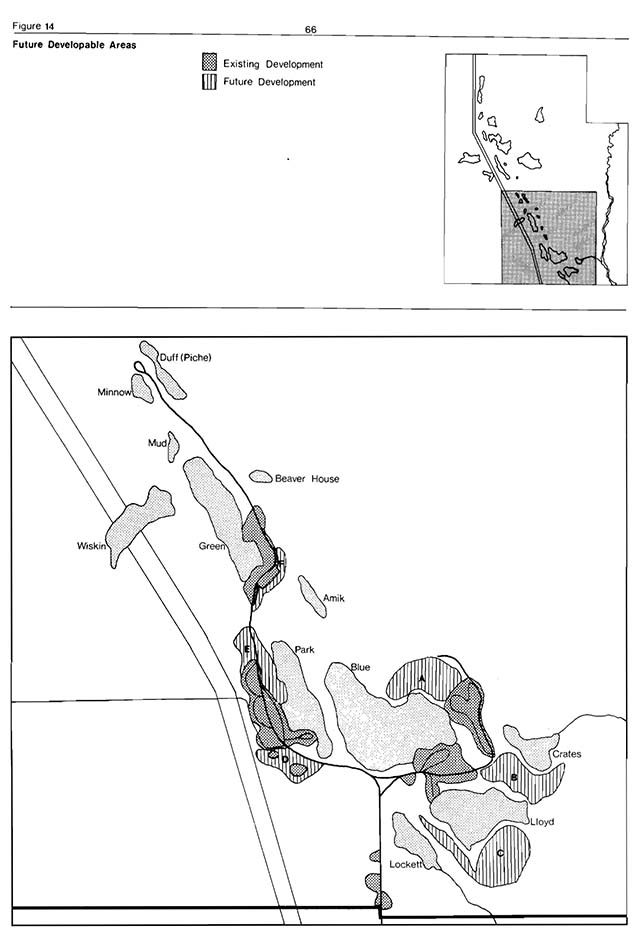

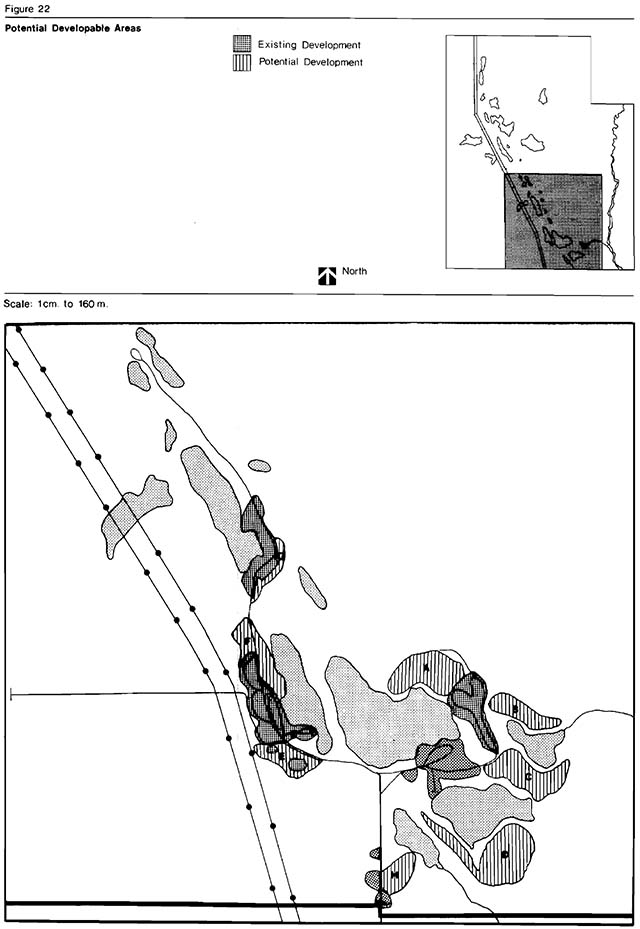

Table 4 provides a complete inventory of the current park facilities (Figure 4). Existing and potential developable areas are presented in Appendix 6.

Camping

There are three organized campgrounds in the park: Blue-Lloyd Lake (37 sites), Park Lake (40 sites), and Blue Lake East (30 sites). These areas offer such facilities as vault toilets, chlorinated water systems, a central woodyard, fireplaces, picnic tables and a central garbage system. No interior campsites have been developed.

Day-use

The main day-use area is located at the south end of Green Lake and offers 1,115 m2 of wet and dry beach area, 11,520 m2 of picnic area, parking area for 106 cars, a diving raft, fireplace grills, two change houses and three sets of vault toilets.

There are 9 km of interior park roads. Six hiking trails (11.8 km) and one self-guiding trail (1.2 km) are available. There are no established snowmobile, cross-country skor snowshoe trails within the park. The access roads, the hydro corridor, and the developed trails; however, are frequently used for winter recreation activities. There is 5.5 km of good canoeing on Deception Creek. Most of the park lakes provide good canoeing potential.

Table 4: Present park facility inventory

| Facility | Area |

|---|---|

| Day-use beach (dry) | 558 m2 |

| Day-use beach (wet) | 558 m2 |

| Day-use beach - Picnic Area | 1.15 ha |

| Park Area (vehicles) | 106 |

| Campgrounds - Campsite Units | 107 |

| Utilities - Water Pressure System | 1 |

| Utilities - Water Lines | 4.8 km |

| Utilities - Trailer Filling Station | 1 |

| Utilities - Trailer Filling and Dumping Station | 1 |

| Utilities - Transmission Lines - overhead | 1.2 km |

| Utilities - Transmission Lines - underground | 0.4 km |

| Utilities - Centralized Garbage | 3 |

| Buildings - Entrance Control Booth | 1 |

| Buildings - Summer Staff Quarters | 1 |

| Buildings - Maintenance Building | 1 |

| Buildings - Change House | 2 |

| Buildings - Type 2 Vault Privy | 11 |

| Buildings - Type 2 Vault Privy (basin) | 1 |

| Buildings - Vault Privy (Centennial + 1) | 1 |

| Buildings - Pumphouse | 1 |

| Buildings - Shower-Laundromat Complex | 1 |

| Roads and Trails- Paved - two way | .96 km |

| Roads and Trails- Gravel - one way | 3.22 km |

| Roads and Trails - two way | 4.83 km |

| Trails - Interpretive (self guiding) | 1.2 km |

| Trails - Hiking | 11.8 km |

| Trails - Snowmobile | 12.87 km |

| Structures - Lookouts | 1 |

| Structures - Docks | 6 |

Enlarge figure 4: Park facilities (PDF)

4.10 Park capacity

With 107 campsites, Greenwater can provide an optimum carrying capacity of 13,135 camper-days based on a 60 percent occupancy rate and a 62-day season (July and August) (Table 5). Optimum capacity is defined as a level of use which is environmentally sound and which is normally less than the maximum level of use.

The park’s interior (i.e. Deception Creek and the esker system) has good potential for about 15 interior campsites with an annual capacity of 3,000 camper-days.

The existing intensive day-use facilities have an annual capacity of 19,065 user-days. Frequently, heavy use and overuse occur on weekends when large groups are admitted to the day-use area. With the present level of development, the day-use area can accommodate approximately 201 users at any one time (theoretical daily capacity) (Appendix 5).

Table 5: Carrying capacity of existing recreation facilities (1977)

| Facility type | Existing Development | User-Day Potential | User-Day Consumption | Surplus user-days |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campground | 107 campsites | 13,135 (July-August) |

13,318 (July-August) |

0 |

| Green Lake picnic area |

1.15 ha | 8,005 | 5,536 | + 3,469 |

| Green Lake day-use wet beach |

558 m2 | 8,005 | 5,536 | + 3,469 |

| Green Lake day-use dry beach |

558 m2 | 8,005 | 5,536 | + 3,469 |

| Access and Hiking Trails | 11.8 km | 6,000 | 4,112 | + 3,544 |

| Self-guiding Nature Trail (Green Trail) |

1.2 km | 6,000 | 4,112 | + 3,544 |

| Canoe Route (Deception Creek) | 5.5 km | 600 | 100 | + 500 |

The Deception Creek area offers 5.5 km of excellent canoeing. Park, Blue, Lloyd, Green and Bear lakes all have easy access for canoeing and fishing. These lakes have a capacity to provide 1,600 fishing days annually. All park lakes have an annual fishing capacity of 11,320 user-days. This capacity was calculated on the basis of creel census returns and field observations.

The 11.8 km of hiking trails in the park have a seasonal capacity of 6,000 user-days. This was calculated on the basis of interpretive statistics and estimates by park personnel.

4.11 Current recreation capacity

Camper-use characteristics

Both destination and stopover campers stay in Greenwater Provincial Park. A 1976 survey showed that 34 percent of the campers were stopover and 66 percent were destination. The average party size is 3.3 persons. The average length of stay has increased from 1.4 days in 1968 to 3.1 days in 1977 (Table 6). The high percentage of stopover campers, who stay only one or two nights, may be influenced by the schedule for the Polar Bear Express to Moosonee. Approximately 83 percent of the campers originate in Ontario, 11 percent in the United States and 6 percent in the other provinces.

Percentage occupancy of the park’s campgrounds during July and August increased from 41 percent in 1967 to 62 percent in 1970 to a maximum of 81 percent in 1971 (Table 6). The occupancy rate decreased to 48 percent in 1976 when 30 new campsites were developed. If the present utilization trends continue, the campgrounds will reach optimum capacity by 1979-80 (60 percent capacity).

Park data sheets show that in 1977, 13,318 camper-days were consumed.

Table 6: User statistics record -Greenwater Provincial Park (for the period June/Sept.)

| Year | Number sites | Total Visitation*1 vehicles |

Total Visitation*1 visitors |

Day-Use*2 vehicles |

Day-Use*2 visitors |

Camping campers |

Camping camper days |

Camping |

Camping occupancy rate*3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 | 107 | 13,494 | 42,139 | 1,345 | 4,136 | 5,215 | 13,318 | 3.1 | 49% |

| 1976 | 107 | 13,414 | 49,607 | 1,490 | 5,313 | 5,347 | 12,760 | 2.3 | 48% |

| 1975 | 107 | 15,330 | 55,344 | 1,451 | 5,369 | 5,227 | 11,656 | 2.2 | 41% |

| 1974 | 80 | 6,103 | 21,477 | 1,088 | 3,699 | 5,026 | 10,932 | 2.2 | 52% |

| 1973 | 78 | 9,051 | 32,996 | 1,348 | 4,886 | 5,745 | 11,269 | 2.2 | 55% |

| 1972 | 50 | 7,296 | 28,278 | 759 | 2,581 | 4,564 | 9,346 | 2.1 | 47% |

| 1971 | 50 | 6,478 | 25,937 | 1,073 | 3,648 | 4,949 | 10,340 | 2.1 | 81% |

| 1970 | 52 | 5,177 | 22,862 | N/A | N/A | 4,138 | 8,658 | 2.1 | 62% |

| 1969 | 52 | 2,456 | 15,327 | N/A | N/A | 4,095 | 6,401 | 1.6 | 45% |

| 1968 | 51 | 4,620 | 20,465 | N/A | N/A | 3,034 | 4,324 | 1.4 | 41% |

| 1967 | 45 | 4,762 | 21,158 | N/A | N/A | 2,624 | 4,786 | 1.8 | 41% |

*1based on traffic count

*2based on permit sales

*3July August campsite occupancy rate, based on 60% optimum use × (5)

Day-use characteristics

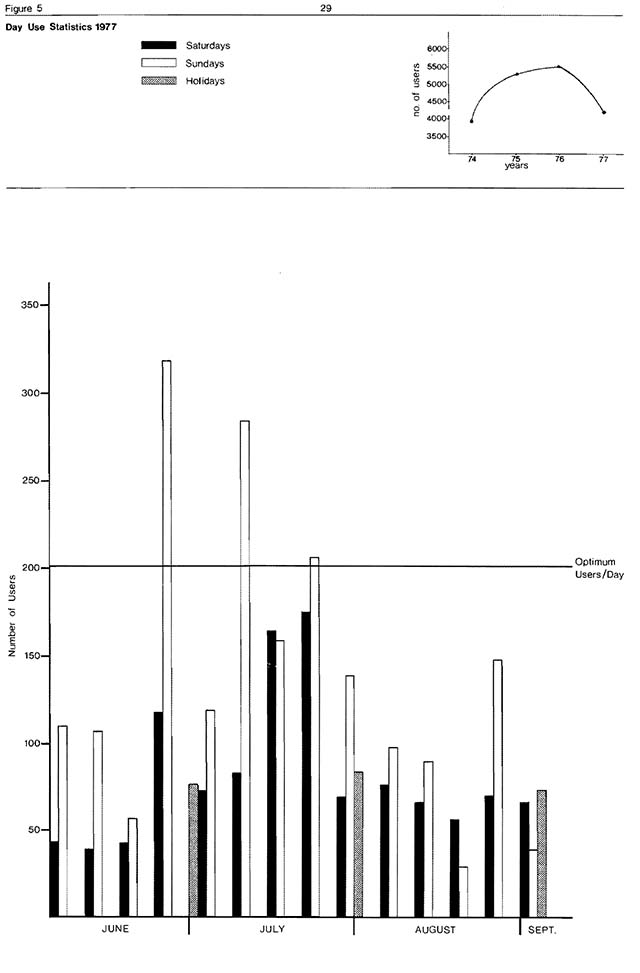

After 16 years of operation (1961-1977), the statistics indicate a higher percentage of day-use visitors to the park than campers (based on traffic-counter estimates). If the present trend is projected, there w11 be an increase from 6,000 day-users in 1975 to 8,800 in 1980. A four year comparison (1974-1977) based on permit returns and day-use statistics for the 1977 park season is presented in Figure 5.

Summer recreation activities

Recreation canoeing is a popular summer activity in the park. Estimated seasonal use is 1,500 user-days. Fishing during the 1977 summer season resulted in the consumption of 2,300 user-days of fishing opportunities. In 1977 1,121 user-days were consumed by park visitors using the self-guiding interpretive trail. In the same year, 1,335 people hiked along the 11.8 km of trails.

Winter recreation activites

Snowmobiles are permitted on the main park roads. The number of visitors engaging in cross-country skiing and snowshoeing is relatively low (200 user days annually), while ice fishing activity is moderate to light (750 user-days annually). No parking facilities are provtded during the winter season.

Group visitors (Non-paying)

The park facilities were not used extensively for camping or day-use by organized groups. In 1977, 5 camping groups (229 campers) and 8 day-use groups (445 people) utilized the park facilities.

Seniour citizens (Non-paying)

In 1977, senior citizens utilized 98 user-days and 448 camper-days (1977 Park Statsties).

5.0 Biophysical resources

5.1 Climate

In general, the climate of the park area is marked by warm summers with long hours of daylight and cold winters with heavy snowfall. Mean monthly maximum and minimum temperatures are -12°C and -24°C for January and 24°C and 11°C for July respectively. Mean annual precipitation is 79 cm (Chapman and Thomas, 1968). The average rainfall is 54.0 cm. The maximum average accumulated snowfall is 91.4 cm and is reached by March. The prevailing winds are westerly. Freeze-up dates range from October 30 to November 24 (average November 14). Major leaf fall occurs during the second week of October (Harrison, 1973).

5.2 Geology and geomorphology

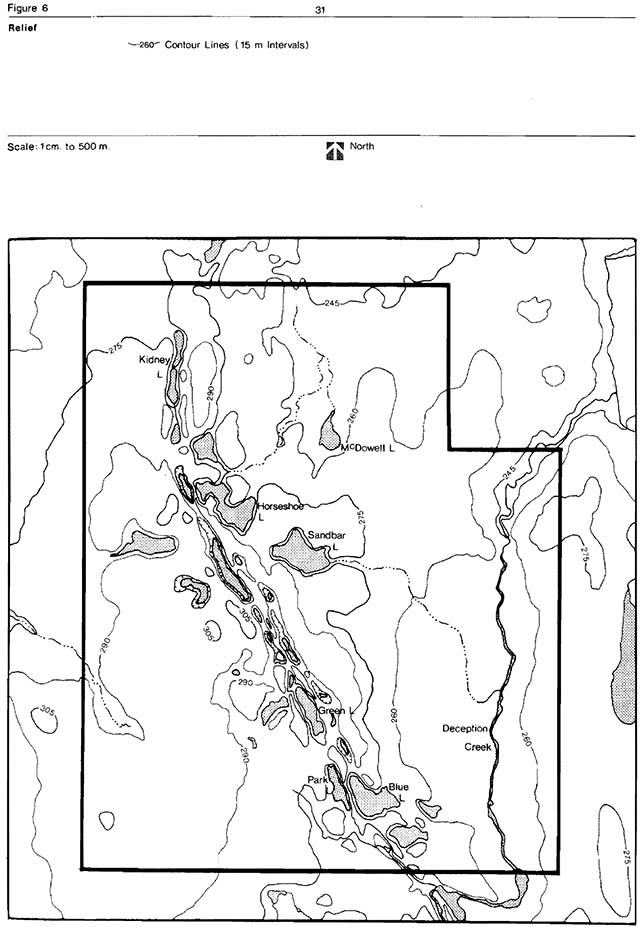

Early Precambrian (Archean) granitic plutonic rocks (more than 2.5 billion years old) with pegmatitic phases comprise the few documented bedrock outcrops in the park. Approximately 200 m2 of bedrock is exposed. The bedrock topography is unknown but its variability is suggested by the more than 50 m elevation difference between the outcrop surface in the southwestern part of the park and the bottom of Park Lake (Figure 6).

Enlarge figure 6: Regional setting (PDF)

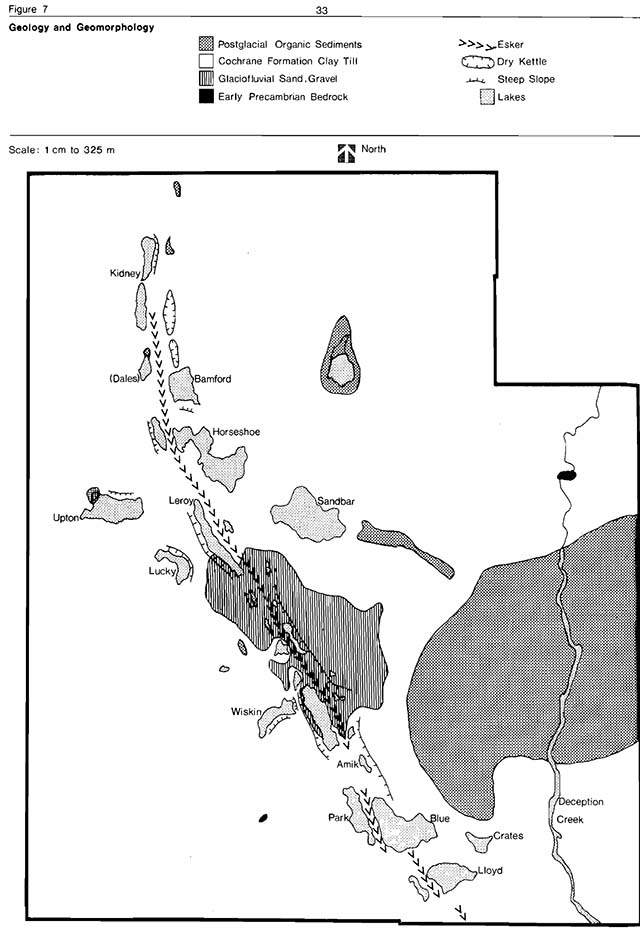

The Precambrian erosion surface is buried by a variety of unconsolidated sediments deposited by Quaternary continental glaciers and their meltwaters. The most prominent landforms are the central esker and the numerous water-filled kettles that parallel its base. Observed lithologies and their stratigraphic relationships indicate that only Late Wisconsinan and Recent sediments are present in the park. The sediments record (1) the recession (about 9,200 years ago) of the last major continental glacier that covered central Canada, (2) a local readvance (about 8,200 years ago) and a recession (about 8,100 years ago) of the minor ice sheet (the Cochrane lobe, whose southern margin reached a point approximately 10 km north of Timmins), and (3) the recent filling of bogs, depressions, and stream channels with organic, colluvial and fluvial sediments (Figure 7).

The northward recession of the last Laurentide ice sheet flooded a vast area of northeastern Ontario and northwestern Quebec. The meltwaters formed Lake Barlow-Ojibway approximately bounded to the south, in its later stages, by the present St. Lawrence River - Hudson Bay drainage divide and to the north by the front of the ice sheet. Numerous eskers were formed by subglacial streams depositing debris into the proglacial lake as the ice margin receded.

Glaciolacustrine varved clays and silts of Lake Barlow-Ojibway are commonly exposed in the park vicinity. Their presence within Greenwater Provincial Park has not yet been established.

Glaciofluvial sediments, that accumulated within and beyond the ice margin, form the esker and adjacent buried outwash deposits. They consist of stratified sand and gravel and are exposed on the eroded upper slope of the esker, the surface of the esker road, and in the small excavation adjacent to the park entrance road.

The Cochrane lobe overrode these deposits and landforms blanketing them with clay till, often more than 1 m thick. Cochrane till forms the present surface material of most of the park including segments of the esker crest. It is well exposed in the vertica1 wall of the excavation near the park entrance. The till’s surface of contact with the underlying glaciofluvial sand and gravel is also visible.

Enlarge figure 7: Geology and geomorphology (PDF)

The rapid melting of the Cochrane lobe formed shallow lakes on the land surface. Their sediments (fine sand and silt) overlie the Cochrane till in many of the topographically low areas and on the steep slopes of kettles and the esker. Colluvial sand and gravel, eroded from the slopes also contribute to the partial burial of Cochrane till in the depressions. In the park vicinity, the oldest radiocarbon date measured on wood found in peat overlying post-Cochrane lacustrine deposits is 6,380 ± 350 years ago. This provides a minimum date for the drainage of the post-Cochrane lakes and the beginning of bog formation.

The soils of the park are developed from parent materials transported by glaciation. A significant component is calcium carbonate derived from Paleozoic sediments in the James Bay Lowlands. Weak podzols have developed on the upland sands, gray luvisols on the calcareous upland clays, peaty. gleysols in the low areas and organic soils in the bogs.

5.3 Hydrology

Greenwater Provincial Park is contained within the 4MD1 and 4MD2 watershed units (Watershed Divisions Map 25WD Cochrane, 1974) which is part of the much larger Hudson Bay watershed system. Those lakes having perennial outlets drain eastward via Deception Creek (6 km of which lies within the park boundaries) into the Frederick House River, then northward into the Abitibi and Moose rivers and eventually into James and Hudson bays.

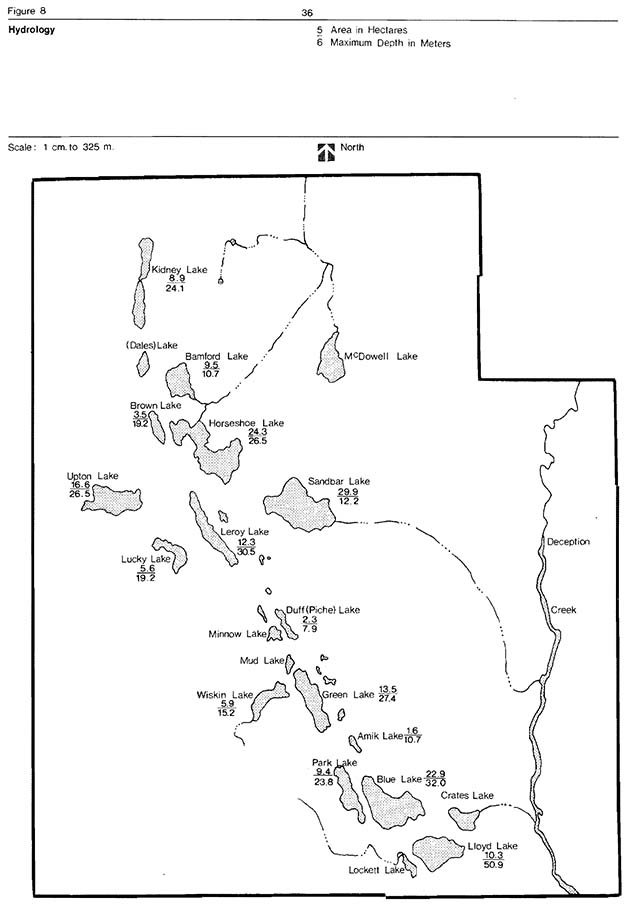

The park has twenty-six small lakes covering 200.7 ha and creek systems covering 24.2 ha (Figure 8). The lakes vary in area from 0.4 ha to 29.9 ha (Table 7). The remaining bodies of water consist of shallow pot holes and beaver ponds.

Both mesotrophic and oligotrophic lakes are present in the park. These lake types are classified according to the amount of nutrients present, the soil characteristics and the depth of the lakes. Park, Bamford, Crates, Lockett and McDowell lakes are examples of mesotrophic lakes with moderate amounts of dissolved nutrients and aquatic plant growth along the lake margins. Sandbar, Lloyd, Kidney, Blue, Leroy and Green lakes are representatives of oligotrophic lakes which are nutrient-poor and have little aquatic vegetation. The pH range of the park lakes is 7.0 to 8.5. Those lakes with pHs above 7.0 indicate the presence of calcareous (alkaline) materials (Table 7).

At present, Deception Creek has not been monitored or surveyed sufficiently to give a complete analysis of its hydrology.

5.4 Fisheries

In addition to the introduced trout species, there are natural populations of yellow perch in Horseshoe, Lucky, Upton, Sandbar and Brown lakes and northern pike in Horseshoe Lake (Table 8). Deception Creek contains natural populations of northern pike, white sucker, yellow pickerel, brook trout, yellow perch, lake whitefish and numerous minnow species. A more detailed inventory of fish species and aquatic invertebrates is recorded in the park’s Fisheries Management Plan.

Enlarge figure 8: Hydrology (PDF)

Table 7: Water Statistics of the Major Lakes in Greenwater Provincial Park

| Lake Names | Area (hectares) | Depth (metres) mean | Depth (metres) max | Secchi Disc - Diss. O2 (ppm - Reading taken at 1.5 meter level) | Secchi Disc- reading (metres) | Secchi Disc pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | 22.9 | 8.6 | 32.0 | 8.0 | 10.3 | 8.0 |

| Lloyd | 10.3 | 12.5 | 50.9 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 8.0 |

| Green | 13.5 | 11.2 | 27.4 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 8.5 |

| Park | 9.4 | 5.8 | 23.8 | 8.0 | 6.4 | 8.1 |

| Wiskin | 5.9 | 4.6 | 15.2 | 6.0 | 2.9 | 8.1 |

| Duff (Piche) | 2.3 | 3.8 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 6.3 | 8.2 |

| Kidney | 8.9 | 5.5 | 24.1 | 10.0 | 5.8 | 8.0 |

| Leroy | 12.3 | 9.5 | 30.5 | 11.0 | 5.6 | 7.0 |

| Horseshoe | 24.3 | 6.6 | 26.5 | 9.0 | 3.4 | 8.5 |

| Lucky | 5.6 | 4.9 | 19.2 | 9.0 | 2.6 | 7.0 |

| Upton | 16.6 | 5.4 | 26.5 | 10.0 | 2.9 | 7.5 |

| Sandbar | 29.9 | 3.9 | 12.2 | 8.0 | 3.4 | 7.0 |

| Brown | 3.5 | 5.3 | 19.2 | 8.0 | 4.4 | 7.0 |

| (Dales) | 2.4 | 4.1 | 16. 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Amik | 1.6 | 2.5 | 13.7 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Bamford | 9.6 | 1.6 | 10.7 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

N.B. The remaining 10 small lakes and pot holes have not been surveyed since they exhibit limited potential for stocking with salmonid species

Table 8: Fish species distribution in the surveyed lakes and Deception Creek within Greenwater Provincial Park

| Lake Name | Lake Trout | Rainbow Trout | Brook Trout | Northern Pike | Yellow Pickerel | Yellow Perch | White Sucker |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blue | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N |

| Lloyd | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N |

| Park | N/A | N/A | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| Green | N/A | N/A | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Wiskin | S | N/A | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Duff (Piche) | N/A | N/A | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kidney | N/A | N/A | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Leroy | N/A | S | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| Upton | N/A | N/A | N/A | S | N/A | N | N/A |

| Lucky | N/A | N/A | N/A | S | N/A | N | N/A |

| Sandbar | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N |

| Horseshoe | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A | N | N |

| (Dales)* | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Amik** | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Brown | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N | N/A |

| Bamford* | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Deception Creek*** | N/A | N | N | N | N | N | N |

*contains only small fish species

**not known to support any fish species

***supports a natural population of lake whitefish and small fish species

5.5 Vegetation

Greenwater Provincial Park is located in the B.4 Northern Clay Section of the Boreal Forest Region (Rowe, 1972). Forest growth and species composition in this section are influenced by widespread surface deposits of water-worked tills and lacustrine materials, a nearly level topography and local climatic conditions.

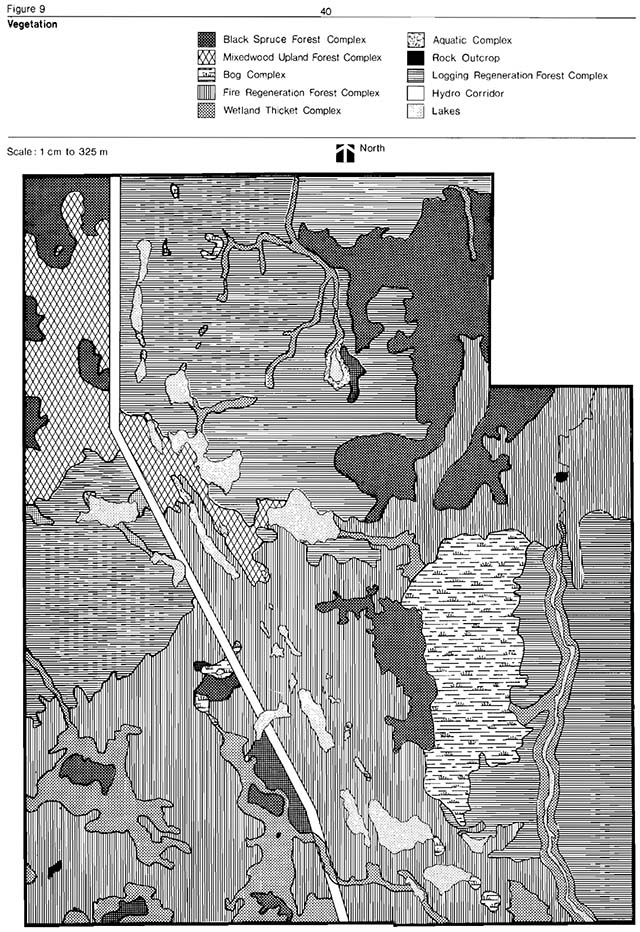

Past clear-cut and high grading logging operations have affected 50 to 60 percent of the park’s vegetational cover. Frequent and extensive fires between 1900 and 1940 have influenced another 15 to 20 percent of the park’s vegetation. These areas have been designated as fire and logging regeneration forest complexes. The wetland thicket and rock outcrop complexes have also been subjected to various degrees of human disturbance. Four areas of the park which have remained in a relatively undisturbed state in recent times are a lowland black spruce forest complex, a bog complex (Figure 9).

The “Fire Regeneration Forest Complex” occupies a large area of the southwestern section and a portion of the northeastern and southeastern parts of the park. Four associations: pioneer blueberry- lichen barren, young birch regeneration, young aspen- birch regeneration and mature aspen regeneration forest associations have been identified. They represent typica1 post fire serai1 stages.

The “Logging Regeneration Forest Complex” occupies most of the northwestern section of the park and the area surrounding Deception Creek (Figure 9). These areas are in various stages of regeneration and include both lowland and upland sites.

The “Well and Thicket Complex” occupies low wet sites along the shores of the lakes and creeks which have been disturbed by beaver damming, past logging operations and/or seasonal flooding.

Enlarge figure 9: Vegetation (PDF)

The “Rock Outcrops” occurs in two areas in the southwest corner of the park and one at the Deception Creek Falls. The land adjacent to these outcrops has been disturbed by fire and agricultural land clearing operations. No unusual plant species were recorded.

The “Black Spruce Forest Complex” is located in the northeast corner of the park. It can be divided into three associations: a black spruce swamp forest, a cedar-black spruce swamp forest and a black spruce-balsam fir forest.

The black spruce swamp forest is the dominant association within the complex. It represents a typical boreal forest in the Northern Clay Belt Region. Within this community, three orchid species, which are considered rare to the clay belt, were recorded (i.e. yellow lady’s slipper, Hooder’s orchis and one-leaf rein-orchis). The seasonal association, the cedar-black spruce swamp forest, occupies small islands or pockets within the black spruce swamp forest. Two plants of biogeographical interest were found: white mandarin (a member of the lily family) and black ash. The black spruce-balsam fir forest association occupies low marginal sites where the black spruce swamp forest graded into a drier mixed-wood upland forest association.

The second vegetation complex, that remained relatively undisturbed is the “Bog Complex”. Four associations comprise this complex; an immature open floating bog mat, an infilled low shrub bog, a lagg zone of speckled alder-sedge-buckbean and a mature black spruce-tamarack treed bog.

The immature floating bog mat association is confined to several localized depressions (i.e. northwest of Wiskin Lake and southeast of Lloyd Lake). The association is characterized by a semi-floating sphagnum moss mat adjacent to open water. The second association is an infilled low shrub bog located southeast of Lloyd Lake. Here the veg tation consists of an outer ring of mature black spruce and the occasional tamarack surrounding a closed thicket of low ericaceous shrubs (i.e. leatherleaf, bog rosemary and swamp laurel). The speckled alder-sedge-buckbean association occupies specialized sites, termed lagg zones, within the bog complex. In these areas, a continuous flow or seepage of fresh water from surrounding higher ground provides a nutrient-rich habitat for the growth of marsh plants which do not normally survive in the harsh acidic bog environments. The mature black spruce-tamarack treed bog association occupies an extensive low-lying area east of Green Lake. The vegetation is characterized by an open stand of co-dominant black spruce and tamarack. Orchids considered rare and scarce to the clay belt region were recorded in this treed bog (i.e. yellow lady’s slipper, leafy white orchis, one-leaf rein-orchis, Hooker’s orchis, small round-leaved orchis and heartleaf twayblade).

A “Mature Mixechwood Upland Forest Complex” is located in the northwest corner of the park on gently sloping west facing sites north of Upton Lake. The complex has remained relative undisturbed for approximately 140 years. The dominant association is a mature mixedwood stand of white spruce-white birch-balsam poplar-black spruce complex. The ground flora contains mesic plant species typical of the clay belt (i.e. wild sarsaparilla, large-leaved aster, bunchberry, clintonia and dwarf raspberry).

The “Aquatia Complex” (Figure 9) is closely associated with the wetland thicket complex. It consists of emergent, floating and submerged vegetation growing in communities that integrate with each other. Four representative areas are located along the shores of Lockett, McDowell and Crates lakes and Deception Creek. A plant checklist for the park is found in Appendix 1.

5.6 Fauna

Mammals

Many fur-bearing marrmals inhabit the park area. These include beaver, muskrat, lynx, river otter, marten red fox, mink ermine, fisher and possibly least weasel.

Several timber wolves are known to frequent the park and surrounding area.

Moose and white-tailed deer are the only representatives of the ungulate family which inhabit the area. There are approximately 4 to 6 moose in the park. A small population of white-tailed deer are present in the park area. These deer are at the extreme northern limit of their species distribution. Bear have been sighted in the Park Lake and Blue Lake East campgrounds.

Trapping grids were used in five representative communities to sample the numbers and species of small mammals which inhabit these areas of the park. The results of this inventory, the fur return printouts of trapline PE-85, and the official sightings are presented in Appendix 2.

Birds

The avian community of the park is both diverse and numerous. Spring migration provides excellent bird watching opportunities. Approximately 161 different bird species (including migrants) have been sighted and recorded in the park’s bird checklist (Appendix 3).

Amphibians and reptiles

Amphibians which inhabit the park, include Jefferson salamander, spotted salamander, American toad, wood frog, leopard frog, spring peeper and mink frog.

The only reptile known to inhabit the park is the eastern garter snake.

6.0 Cultural resources

The agricultural history of the park area as it relates to farming in the Cochrane Clay Belt (1910-1945) will be documented during the 1978 park season. Very little archaeological data exists for Greenwater as compared to that recorded for the Cochrane District.

6.1 Prehistory

Cochrane District was first inhabited (approximately 5,000 years ago) by the Abitibi Narrows peoples along the Abitibi and Frederick House rivers. Later (2,000 years ago), the district was occupied by another river oriented culture, the Laurel peoples.

Since 800 A.D. the area has been occupied by Northern Algonkians. Algonkian sites, which date to 1,400 A.D., have been discovered in the vicinity of the park.

No archaeological survey has been conducted within the park’s boundaries, but the area could have been utilized on a seasonal basis by prehistoric peoples (J. Pollock, 1976).

6.2 History

In 1867, an inland Hudson Bay Company post was established at Newpost, north of Fraserdale on the Abitibi River. Indians who traded at the post had a large system of hunting territories in the vicinity of the Abitibi River which included the present park boundary.

Early settlement general (1869-1931)

The growth of government information concerning the development potential of the Great Clay Belt of the Moose River Basin, can be divided into two periods.

Initially there was a slow accurnmulation of knowledge of the area’s resources by the provincial and federal governments. The land (Rupert’s Land) was vested to the Hudson’s Bay Company until 1869 when it carne under the jurisdiction of the Dominion of Canada. For the next 20 years the area remained in Federal hands - terra incognita. Then in 1889 it was ceded to Ontario (The Ontario Boundary Act of 1889).

In the second period, 1889-1905, a flurry of surveys were conducted. Aspirations from these reports were varied, Since the majority of these papers had yielded optimistic results, a second revived interest and intensive exploration followed. The vast agricultural, mining, pulp and hydroelectric potential implied that a whole new growth area could be developed. Government involvement provided the stimulus, the proposed railroad to James Bay, the catalyst. What transpired, was the last major colonization attempt in Ontario’s history.

The railroad, the main link in the settlement’s growth, was built as far as New Liskeard in January, 1905 and Cochrane in 1909. The sale of lots preceeded, or was in conjunction with the spread of the railway. The basis for land development was the Public Lands Act. It provided for the sale of designated public lands at 50 cents per acre, provided certain terms were fulfilled. For example: during the first three years, the land was to be occupied six months a year a house of at least 16“ × 20” dimension; land cleared at the rate of 2 acres per year; etcetera. The exploitation of the lots for timber soon became an alarming problem. The government reacted by, reducing the lots from 160 acres to 80 appointment of homestead inspectors to oversee the land clearing and insuring the lots were suitable for agricultural purposes.

The expansion of the settlement in the Clay Belt was of remarkable proportions. In less than 30 years, 200 or anized townships were created. By 1931, their population reached 81,000 of which 48 percent were located on farms.

Land settlment in the southwestern section of Greenwater Provincial Park

The major settlement by families of Eastern European origin, occurred in the early 1930s and lasted for about a decade. Evidence of an earlier influx of settlers between 1913 and 1921 was possibly obliterated by the forest fires of 1910 and 1916.

Availability and market for pulpwood and sawlogsprovided incentive to the settlers to clear land. Portable sawmills were located on Park and Upton lakes, and a highway right-of-way was cut during the 1930s across the present southern boundary of Greenwater Provincial Park. The tentative proposal was a bonus for landholders and speculators. However, the political climate changed as well as the road location.

By 1936, about 2,000 acres were under application for settlement. Of that amount, only 5 percent was cleared.

A combination of factors contributed to the gradual abandonment of the land:

- Withdrawal of the highway corridor;

- The recruitment of able-bodied men for World War (some never returned);

- The misleading concepts of the north, combined with a few lean years, caused many disenchanted settlers to leave;

- Many landholders sold or extracted the timber, having no inclinations towards agriculture;

- The depression posed many financial constraints that limited development;

- The extreme climatic conditions, short growing season, frequent frost and poor drainage; and

- A forest fire in the late 1930s that accented the dangers from the previous fire catastrophies from the early part of the century.

As the settlers departed, the land reverted to shrubs and trees.

Today, the Cochrane Clay Belt, Ontario’s last agricultural frontier, includes areas of total depopulation. Yet the Clay Belts were one of Ontario’s major agricultural frontiers after 1900. They provided an interesting, though flawed, example of the publicity assisted agricultural settlement of an adverse northern frontier.

Greenwater’s important historical theme combines the theme segments (as outlined in Topical Organization of Ontario History) of “Clay Belts”, “North Central Ontario Pulp and Paper” and “Modern Ontario” (particularly the rural depopulation and Great Depression aspects of this subject). These three segments are all closely related. No other park in the province exemplifies as well this locally important historical theme. While some limited “homesteading“ was done within the park boundaries (notably to the west of Park Lake), a complete development of this theme would also make visitors aware of resources outside of Greenwater such as the Kapuskasing Experimental Farm and abandoned farmland in the Cochrane area, and the paper mill tours at Smooth Rock Falls and Iroquois Falls.

The historical area west of Park Lake may qualify as a “low level” historical zone, but research planned for the summer of 1978 will verify this.

Hydro development

In 1925, the Abitibi Power and Paper Company acquired a generating station at Island Falls on the Abitibi River.

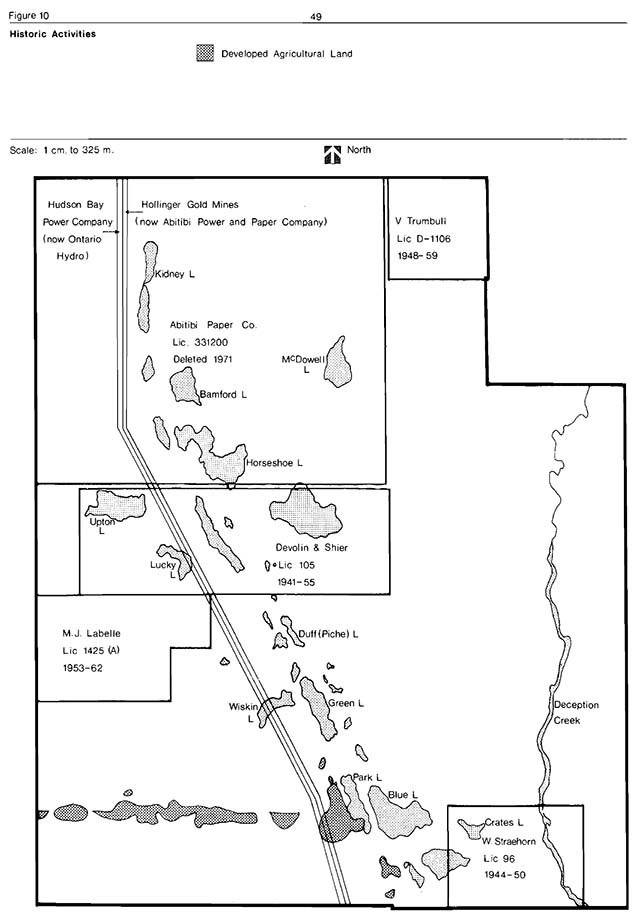

This station was originally owned by Hollihger Gold tines. Power lines fromsland Falls were constructed south through the area nowestablished as a park to Hunta then along the Canadian National Railway line to Stimson and ontoroquois Falls. Five years later, in 1930, the Hudson Bay Power Company initiated the Abitibi Canyon Development. The Company experienced financial difficulties and the project was taken over by Ontario Hydro. A double tower transmission line was constructed parallel to the Abitibi line. Combined, these transmission lines occupy 91 ha of the park (Figure 10).

Forest fires

No accurate records have been kept of the early fire history for the park area. A fire burned the forests of the southeast and southwest sections of the park and esker ridge as far north as Leroy Lake in the early 1900s. In 1937, the ridge was burned again east of Green Lak and nort and east of Bear Lake.

Logging history

During the 1940s the Department of Lands and Forests issued licences to cut the Crown timber in the area of the park. All the licences that were granted have not been specifically located. However, those that have are recorded below and located on Figure 10.

- Devolin and Shier - issued 1941/42, expired mid 1950s

- W. Straehorn - issued 1944/45, abandoned 1950

- W. Trumbull - issued 1948, expired 1959

- M. J. Labelle Co. Ltd. - issued 1953, expired 1962

- Abitibi Paper Co. Ltd. - issued circa 1920, the park area was removed from the licence in 1971

Logging and scaling records previous to 1920 are unavailable.

Additional forest resources information can be obtained from the Forest Management Plan for Greenwater.

Enlarge figure 10: Historic activities (PDF)

Logging and issuance of licences, with the exception of Abitibi Paper Company’s licence (Concession IV - VI, Lots 1-8 of Colquhoun Township) was phased out of the park around 1963. In 1971, a new Crown timber licence was granted to Abitibi Paper Company with the park area removed. Abitibi never cut on their licenced area within the park, but did sub-contract.

A silvicultural program has been ongoing in the park since 1956 (Appendix 4). Areas, cut over or burned, were planted in order to provide a satisfactorily stocked forest. Areas treated since 1961 have been site prepared by scarification prior to planting. These plantations have been hand cleared to remove unwanted shrubs around each tree.

7.0 Environmental analysis

Greenwater Provincial Park provides quality camping, fishing, canoeing and backcountry recreation opportunities in a natural environment setting. Greenwater also contains several significant plant communities (life science features) and geomorphological landscapes (earth science features) which merit preservation. Recreational and environmental quality standards limit the level of development that is permissible in these areas of the park.

7.1 Sensitive features

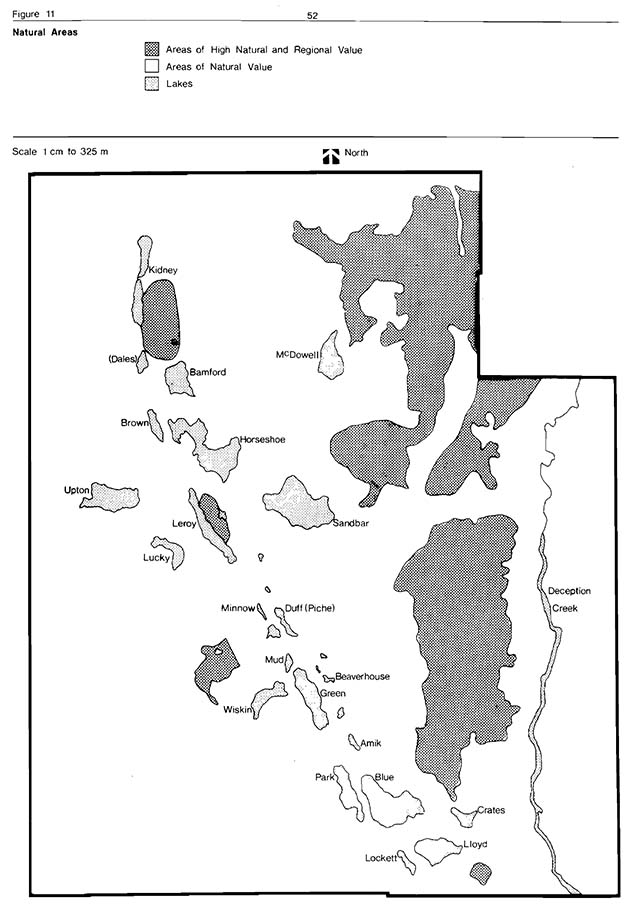

The following is a summary of the important sensitive and/or significant botanical and geomorphological features in Greenwater (Figure 11).

Lakes

The park lakes are fragile and susceptible to pollution due to their small size, lack of drainage outlets and relatively steep backshores. mproper disposal of soap, motor oil, litter, gasoline and sewage could easily affect water quality. None of the lakes have the capacity to support the activities of large numbers of people.

Major development areas are located adjacent to Blue, Park, Lloyd and Green lakes. The present campgrounds and picnic sites were developed in areas of moderate sensitivity surrounding these lakes. However, these areas are not able to withstand intensive use. Any 51 proposed contsruction programs should take into consideration the factors of erosion on the lakeshores, potential pollution effects and general site sensitivity.

Enlarge figure 11: Natural areas (PDF)

Esket complex

The sand and clay soils of the esker ridge and its associated outwash plain are highly susceptible to erosion. Jack pine, red pine, white pine and spruce were planted along the esker complex after recent fires to prevent any sheet erosion. The main park road was constructed along the top of the esker ridge with a minimum of land alteration.

Bog complex

The park bogs are sensitive and regionally significant sites. These areas cannot withstand abrupt changes in drainage or heavy use by park visitors. The bogs contain fragile plant communities which contain insectivorous pitcher plants and sundews and other acid-site plant species. As well, rare or disjunct orchid colonies are located on these sites.

Development area

The birch trees of the campgrounds and day-use areas have suffered surficial damage from visitors stripping the bark and removing branches for kindling wood. The heavily used campsites and picnic areas also exhibit soil compaction, loss of ground vegetation and erosion around the tree roots. Dieback of the trees in these areas continues to be a problem insects (i.e. birchleaf skeletonizer, birch leaf miner, spruce budworm and white pine weevil) have infected the trees of Blue-Lloyd campgrounds, the Green Lake day-use area, and the spruce plantations near Park Lake and adjacent to the staff house.

7.2 Significant floral associations

The floral affinities of Greenwater Provincial Park are primarily boreal and representative of the Northern Clay Belt Region. According to the plant distributions described by Baldwin (1958) and Soper (1976) the park contains 9 species which are scarce and 25 which are rare in the clay belt.

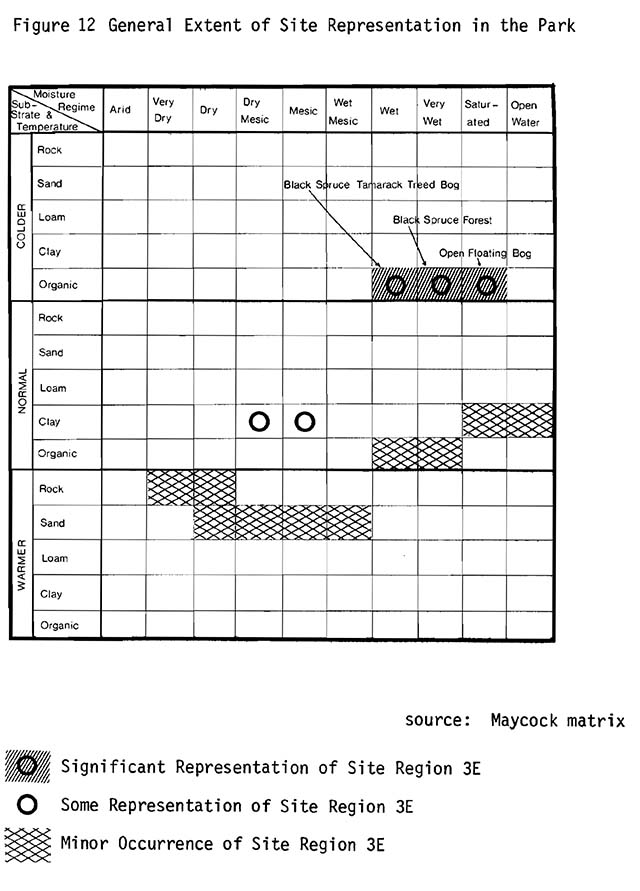

The primary significance of the park’s vegetation lies in its representative values. The park area contains representatives of the three broad site-types which exhibit normal, warmer-than-normal and colder-than-normal microclimates (Culm, 1977). The park contains four regionlly significant bog associations and several floral features of local significance (Figure 12).

Black spruce-tamarak treed bog

This mature bog association east of Green Lake (Figure 11) is regionally significant in the provincial nature reserves system. The site has substantial interpretive, scientific and educational value as an example of a late stage bog succession which illustrates vegetation dynamics and adaptive specialization of bog plant specis. The bog also provides a habitat for six orchid species (yellow lady’s slipper, leafy white orchis, one-leaf rein-orchis, Hooker’s orchis, small round-leaved orchis and heartleaf twayblade) considered rare and scarce to the clay belt.

Open floating bog mats

The two regionally significant bog mat communities (Figure 11) are located northwest of Wiskin Lake and southeast of Lloyd Lake. Swamp pink orchid and linear-leaved sundew are two plant species rare to the clay belt that inhabit the Wiskin Lake bog site. Four orchid species (heartleaf twayblade, one-leaf rein-orchis, green woodland orchis and rose pogonia) considered scarce to the clay belt were also recorded in this bog. Grass-pink, a rare orchid species, was found in the Lloyd Lake bog site. To date, swamp-pink orchid, grass-pink orchid and linear-leaved sundew have never been recorded this far north. These bogs represent significant northern stations for these species.

Enlarge figure 12: General extent of site representation in the park (PDF)

Black spruce forest complex

This mature black spruce forest complex, located in the northeast corner of the park (Figure 11), is similar to the one in the Pierre Montreuil Park Reserve and is of regional significance. It represents a relatively undisturbed (within the past 100-110 years) typical boreal forest of the clay belt. The complex exhibits high natural, interpretive and scientific values including a representative area of boreal forest, typical clay belt ground flora, mature to over-mature black spruce and several isolated orchid species considered rare or scarce to the clay belt.

7.3 Signficant geomorphical features

The geological significance of the park is its scientific value as a preserve of several aspects of glacial geomorphology that evolved from Late Wisconsinan ice recession and the deposition of the Cochrane Till of the North Driftwood Formation during the Driftwood Stadial re-advance. In addition, the park provides sufficient opportunity to illustrate the various deposits and landforms typical of the deglaciation history of a lafge part of the Northern Region (Figure 11). Several features are qualitatively better represented (as scientifically valuable examples as well as in terms of their interpretive potential) elsewhere in the Northern Region, particularly in the Pierre-Montreuil Park Reserve and in Ivanhoe Lake Provincial Park. Some features may also be well represented in the yet unevaluated Remi Lake and Fushimi Lake Provincial Parks.

Palimpest esker-kettle topography

The central esker-kettle lakes complex is a regionally representative example of palimpsest topography associated with the events of the Driftwood Stadial. The nearly completely buried esker morphology is perfectly preserved by the overlying Cochrane Till This puzzling phenomenon has received only speculative attention (Hughes, 1956) and the relatively easy access of the examples in the park could promote further scientific study and also be used in the geologica] interpretive program. The kettles ar also represented as dry, elongate troughs, particularly well developed east of the esker segment adjacent to the south part of Kidney Lake, extending south to the north end of Bamford Lake.

Illustrations of delegation history

In spite of an overall lack of vertical exposure of subsurface sediments, and visual perspectives for viewing large morphologies, the park and its immediate vicinity does offer a regionally representative set of observation sites to examine the record of Late Wisconsinan deglaciation. The only exposure in the park of glaciofluvial sediments in contact with the overlying Cochrane Till is a small excavation into a hillside immediately east of the trailer filling station. A four meter thick section is exposed and clearly illustrates the differences in lithology and bedding of the two deposits. The shallowly northward dipping outwash sands and gravels are truncated by the massive, pebbly clay of the Cochrane Till.

The esker lookout platform overlooking the north end of Green Lake provides one of the few vantage points in the park for observation of the relationship of the esker to its adjacent landforms. The higher topography west of the Green Lake and east of the nearly dry kettle trough on the east side of the esker are clearly visible, particularly in the autumn. The absence of Cochrane Till on the esker crest is also obvious at this location. The combination of these factors could become a useful focal point for interpretive discussions or self-guiding trail literature.

Numerous sand and gravel excavations within five km southeast of the park provide the most recent elements in the post-glacial history of the park area. Finely bedded lacustrine or fluvial sands overlie thin sequences of Cochrane Till at several sites (Figure 11). Casual examination of these unconsolidated sands is usually rewarded with several species of small fossil shells of pelecypods and gastropods that inhabited shallow lakes and streams that formed on the Cochrane till surface after deglaciation was completed, approximately 8,100 years before present.

7.4 Environmental planning issues

Lake management

In general most of Greenwater’s lakes are fragile and susceptible to pollution. Use, development and management of the lakes must be geared to the preservation and possibly improvement in the existing water quality.

A major issue in the past has been the detrimental effects of outboard motors on the park lakes. This includes noise (which is especially important in the high intensity day-use areas), water pollution (which affects the aquatic life and reduces water quality for fishing and swimming) and disturbance of the bottom sediments (which reduces the aesthetic qualities and affects the aquatic flora and fauna). Until recently, the use of outboard motors was restricted to 7.5 kW (10 horsepower) or less 1978, a regulation was passed by legislation which prohibits the use of all outboard motors on the lakes of Greenwater Provincial Park (Revised Ontario Regulation #258/78). More recently, public concern has been expressed about the inclusion of electric motors in the ban. Electric motors cause minimal noise and water pollution.

Trapping

In accordance with provincial park policy, trapping is not permitted in Natural Environment Parks. More specifically the policy states that where trapping is required for management purposes, it will be carried out by the Ministry of Natural Resources. Further, it states that existing commercial trapping rights will be phased out in a manner least harmful to the well being of the existing trappers indigenous to the area. To date there has been unrestricted trapping in Greenwater which is contrary to provincial park policy.

Hunting

In the past, hunting has been permitted in the park except within the Development Zone. The policy states that low intensity sport hunting may be permitted within all or part of a Natural Environment Park, except in Nature Reserve Zones, and in a manner compatible with preservation objectives and other recreational uses. At Greenwater Provincial Park, hunting is considered incompatible with other recreational uses of the park (i.e. viewing and hiking) and therefore will be discontinued.

Transmission lines

Two parallel transmission lines occupy a common 9.6 km by 107 m right-of-way. The lines follow a sub-esker ridge which bisects the western half of the park in a northwest direction. The presence of transmission lines is incompatible in a Natural Environment Park but they existed prior to the establishment of Greenwater Provincial Park. Two patents exist which cover the southern section of the hydro line. The rest of the hydro line is established on Crown land covered by license of occupation.

Ontario Hydro and Abitibi have used Tordon 101 to control all vegetation in proximity to these lines. Spraying with Tordon 101 is permitted in the park as agreed upon by the Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Hydro and Abitibi Power and Paper Company Limited. The chemical is a mixture of picloram and 2-4-D which is retained in the soil for a maximum of two years. Tordon 101 controls woody plants and broad leaf weeds, but has no effect on grasses. A model M Muskeg Tractor was the supply vehicle utilized to transport water (only) to the spray unit thus avoiding lake pollution with the herbicide. All empty herbicide containers were collected and taken to proper disposal sites outside the park area. The spraying was done from the edge of the right-of-way. To minimize aesthetic damage, the 1975 spraying took place in late August. The sprayed areas will have a reduced growth of woody vegetation for 6 to 8 years.

Prior to the 1975 treatment, Ontario Hydro, Abitibi and the Cochrane District settled on guidelines to be followed when spraying Tordon 101 on their right-of-way in the park. One section of the transmission line was set aside as a holding area for park tree planting programs. No chemical treatment was permitted in or near established sensitive areas. A 200 m non spray reserve and/or any backslope, depending on the site evaluation was recommended for Lucky and Wiskin Lakes and the area east of Park Lake. This reserve should reduce the possibility of chemicals leaching into these sensitive waters. Similar restrictions may have to be placed on other park waters adjacent to or on the hydro line.

Land use permits

Provincial Park policy states that all alienated lands and waters within the boundaries of Natural Environment Parks will be acquired. One private hunt and fish camp, under land use permit, is located on Deception Creek (Lot 24, Concession XII, Clute Township) and is included in the Deception Creek extension area. The presence of this camp violates provincial park policy.

7.5 Environmental carrying capacity

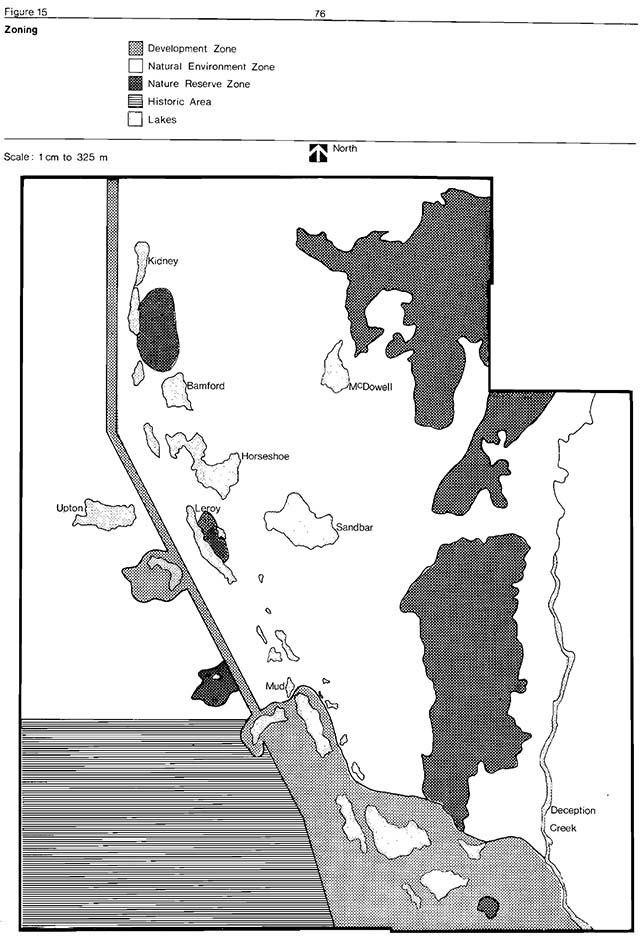

Optimum resource capacities must be identified for the park which will ensure protection of the existing high resource qualities and recreational experiences. An optimum resource capacity must be identified for both camping and day-use (Table 9). However, prior to the establishment of these capacities, sensitive and natural areas must be delineated from areas displaying development potential. Figure 11 identifies areas of high natural and regional value and areas of natural value. Areas of high natural value qualify as candidate nature reserves. They include the black spruce-tamarack treed bog, open floating bog mats, black spruce forest complex and the palimsest esker-kettle topography. The remaining park area is classed as having natural value.

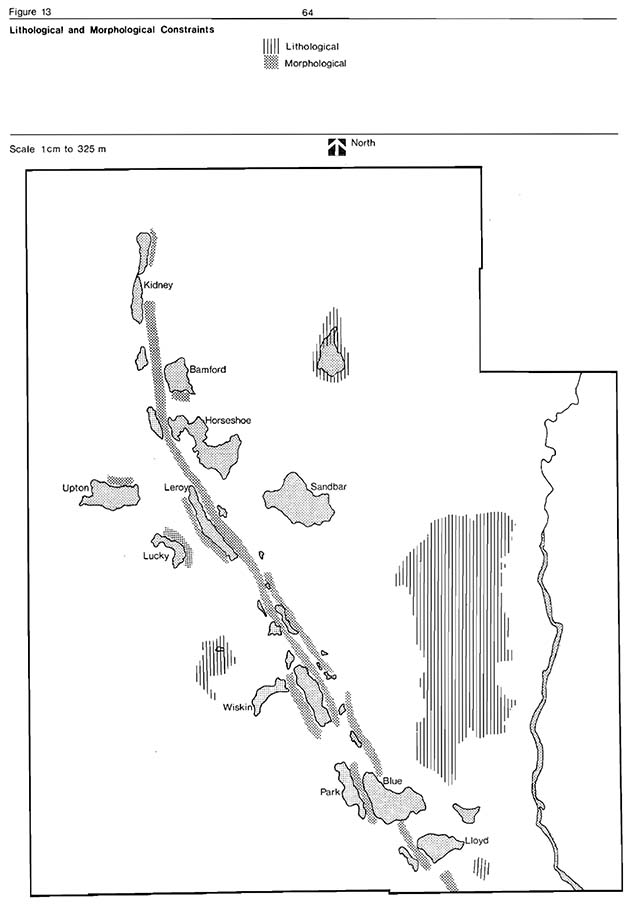

The unsuccessful maintenance of present park developments, i.e. roads, campgrounds and their expansion in the future is greatly dependent on land (lithological and morphological) and water base capabilities and limitations. Lithological and morphological constraints are outl-ined below and mapped in Figure 13.

Table 9: Environmental capacity

| Lake | Land based capacity - Season | Land based capacity - July August | Water Based capacity - Annually |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Lake — Existing day-use capacity | 19,065 | 12,710 | 12,395 |

| Green Lake — Maximum day-use potential capacity | 45,570 | 30,380 | Nil |

| Blue Lake — Existing camping capacity | 9,207 | 6,138 | 29,000 |

| Blue Lake — Maximum potential camping capacity | 27,621 | 12,276 | Nil |

| Park lake — Existing camping capacity | 7,366 | 4,910 | 17,009 |

| Park lake — Maximum potential camping capacity | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Lloyd Lake — Existing camping capacity | 3,069 | 2,046 | 12,700 |

| Lloyd Lake — Maximum potential camping capacity | 12,276 | 8,184 | – |

| Total (camping only) existing capacity | 19,642 | 13,135 | – |

| Total (camping only) maximum potential capacity | 47,263 | 25,370 | – |

Water quality constraints

Maintenance of existing water quality levels is of utmost importance in Greenwater. Because their physical limitations will not permit Greenwater’s lakes to sustain heavy use, particular care must be taken in identifying optimum levels of use.

Lithological constraints

The extensive surficial cover of Cochrane Till (Figure 7) generally imposes a severe limitation to the construction and maintenance of roads, trails and campgrounds. Removal of vegetation would lead to rapid erosion and gullying of the clay-rich till as it is exposed to rain and snowmelt. Successful construction requires almost immediate stabilization or exposed soil or unweathered till with a covering of coarse aggregate or sod. Till surfaces should not be left exposed longer than necessary to complete the covering or filling of an excavation.

Figure 13 emphasizes the occurrence of postglacial organic sediments. These areas are poorly drained and probably exceed several meters in depth. Their high moisture content creates n unpredictable and difficult medium for construction activities.

Morphoplogical constraints