Pruning fruit trees

Information on proper pruning and training techniques to maximize fruit tree production.

Introduction

While the principles of pruning fruit trees do not change, the actual practices used in modern production systems vary. The higher density-supported training systems now used by commercial growers are managed by the same principles of pruning used in the past. Before embarking on a specific training system for high-density plantings, investigate specific techniques required for training and pruning that system.

Principles

Pruning dwarfs trees

Numerous experiments show that pruning is a dwarfing process, that is, it reduces the total size of the tree. Leaves are the food-manufacturing organs of the tree. Cutting away a live branch, which if left would have borne leaves, reduces the output of the "factory", and the final result is a reduced bearing area. Summer pruning has the greatest dwarfing effect.

Pruning appears to invigorate trees

There is a certain deception in the effects of pruning, in that strong shoots with large leaves tend to rise just at the back of pruning cuts. This gives the impression of increased growth. Pruning reduces the number of growing points, thus stimulating an increase of growth at the remaining points. However, pruning, in proportion to its severity, reduces the total growth and the total leaf surface of the tree. (Invigorate trees when necessary with appropriate fertilizer use.)

Pruning effect is localized

The removal or cutting-back of the laterals of a branch reduces the growth of that branch. Pruning has the direct effect of producing growth response in the immediate area in which the cut is made.

Pruning too heavily has several ill effects

Excessive pruning, by over-stimulating growth, causes loss of fruit colour, delayed fruit maturity, and growth of suckers and watersprouts. Excessive succulent growth increases the hazard of fire blight in apple and pear, canker in peach, and winter injury in all species.

Pruning the young tree delays fruit bearing

Because pruning tends to force the growth of long, succulent shoots that grow late in the season, manufactured food is not allowed to accumulate in sufficient quantities to cause the formation of fruit buds. Consequently, the tree is kept in a juvenile or nonfruiting condition for a greater number of years. Young trees often grow very upright, and become so dense that the grower is tempted to thin-out the branches. It has been shown, however, that early fruit bearing will open out a tree much more effectively than pruning. With the young tree, remember: light pruning, early bearing, a spreading tree (Figure 1).

Clean, flush cuts heal more quickly

Make pruning wounds flush with the limbs to which the unwanted branches are attached. The exception to this rule is with peach. With peach use a collar cut rather than flush cuts. Wood healing is more rapid when the bark ridge at the base of larger limbs is not removed during a pruning cut. Where one-year-old wood is being pruned, make the cut as close as possible to a bud to facilitate healing. A stub and/or ragged edges at these points greatly delays the healing of the wound and increases the probability of drying out and infection. This is particularly important with peach because canker may enter where healing is delayed.

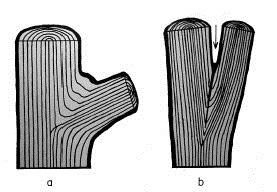

Narrowed-angled crotches are weak

Where the crotch angle is less than 35 degrees the attachment will be weak because of the inclusion of bark. The tissues in narrow crotches (Figure 2) are slower to mature in the fall and may be injured by low temperatures, especially in test winters. Narrow crotches are usually further weakened by water, ice, rot organisms and canker. Thus, remove limbs that make sharp angles early. This avoids possible loss of a large part of the tree later on due to breakage from weight of fruit.

Pruning and training at planting time

When new fruit trees are dug in the nursery, a large percentage of the finer root system is left behind during the process. The new tree that once had a balance of leaves to roots now develops more leaves than there is root system to sustain. The resulting tree will be out of balance, resulting in poor growth.

To overcome this problem, heavily prune all fruit trees at planting time before growth starts. Remove at least a quarter of the potential leaf area. Eliminate all branches below 60 cm. If the tree is tall enough, cut back the leader to about 80–90 cm, and remove all shoots. With well developed trees or older trees having some limbs you wish to retain, you can cut these limbs back to 2 or 3 buds and retain growth in that area. Totally remove limbs:

- with poor crotch angles

- that are too low to the ground or

- large limbs approaching the calliper of the central leader.

Consider the pruning at planting time and over the next 2 or 3 years as a training process. The final strength of the tree depends upon the wise selection of branches and your ability to maintain the proper balance between these branches. Mistakes made in this formative period may mean weak trees and, in addition, the correction of errors may call for severe pruning in later years - the removal of considerable portions of the bearing area and the creation of large wounds subject to infection. It is critically important that you build a strong framework in the early years.

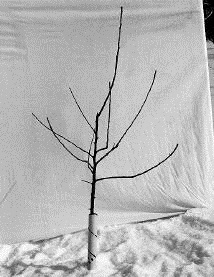

The central leader training system is recommended for all fruit trees. This tree "Christmas tree" form is conical in shape, with a wide base and a narrow top. During the early life of the fruit tree, keep this tree with judicious pruning. Some trees, particularly sour cherry, peach and Japanese plum, do not retain a dominant central leader for long. This is not a problem. The central leader tree at maturity consists of 6–8 main scaffold branches distributed vertically and spirally around the trunk (Figure 3), and with the topmost branch (leader) well in the lead of the lower ones.

The vertical distance between limbs occupying the same quadrant of the tree will vary from 10–80 cm depending on the ultimate size of the tree. Limbs too close together will result in excessive shading. This weakens the limb and leads to poor fruit quality, reduced productivity and ultimately failure of the shaded limb.

If the branch angles at the main trunk are sufficiently wide (over 35 degrees), there will be no bark inclusions in the crotches, resulting in a strong tree.

With many cultivars the central leader will slow in growth, making removal or heading unnecessary. Keeping the central leader in the early years encourages wider angles on the framework branches below it. The central leader of dwarfed trees will be lost prematurely if allowed to fruit too soon.

Training the young nonbearing tree

The less pruning during this period, the more quickly the tree comes into bearing. Consequently, once the main branches are selected, do minimal pruning until the tree is bearing. An early crop of fruit, besides bringing early financial returns, slows down vegetative growth and bends down the branches. This aids in controlling the height of the tree, and opens up the tree to permit more light and better spray coverage. Guard against too-early fruiting of the central leader.

Prune lightly in the third and fourth years, chiefly by thinning-out rather than heading-back. Generally avoid heading-back from the second year, until the trees are in heavy bearing.

Remove branches that form narrow crotches (less than 35 degrees) with the trunk. Eliminate branches that grow straight up or into the tree, those that are weak and drooping, and those that tend to cross or otherwise interfere with others.

Six or 8 main branches are usually sufficient to build a good tree. With pear varieties susceptible to fire blight, and where fire blight is likely to be serious, prune especially lightly and leave more framework and secondary branches.

Pruning the mature fruit tree

Dormant oruning

Most pruning is done when the trees are dormant, between the time when the leaves drop in late fall and when the buds begin to swell in early spring. The safest and best time is just before the buds swell. The most risky time is very late fall and early winter. Dormant pruning of peach and nectarine increases the risk of winter injury; prune during the bloom period.

In the orchard, start spring pruning early enough to be completed before the leaves appear. The risk of winter injury increases if pruning is begun too early. Pruning followed by low temperatures means winter injury — not always seen but almost sure to be present. The amount of injury is directly related to the length of time between the pruning operation and the temperature drop; the shorter the time, the greater the injury.

All pruning has a dwarfing effect, but dormant pruning produces the most new growth. If you want new vegetative growth, dormant pruning is the way to get it. The harder the cutting, the greater is the response in new shoot growth. The response takes place in the area of the tree where the cuts are made.

Pruning during bloom

Most growers prefer not to prune peach and nectarine trees until the flower buds have advanced sufficiently to assess the flower winter survival. Delaying pruning much beyond shuck split may cause a serious loss of tree vigour.

Early summer pruning

Pruning has the greatest dwarfing effect in June and early July. If you wish to reduce vegetative growth and prevent shoots developing, this is the time to prune. But remember that early-summer pruning has a very dwarfing effect. It first dwarfs the root system, and then the whole tree.

Midsummer pruning

Pruning at this time of year has little or no effect on stimulating new vegetative growth. At the same time, it is not nearly so dwarfing as early-summer pruning. The root system is dwarfed somewhat but only moderately, as compared with the results of early-summer pruning.

This may be the time to reduce the height and width of your trees by cutting back the new growth. The amount of cutback would depend on the growth, vigour and age of the tree. A well-grown tree with a good crop could have new growth reduced by 1/2 to 2/3. This will let in more direct sunlight to colour the fruit. It will also reduce vegetative growth, which makes more sugars available to the developing fruit, and results in improved flavour, although fruit size may be reduced.

Fall pruning

Pruning cuts will not heal at this time of year, but in order to spread the work load over more time, some pruning might be started in early fall. Start with the oldest trees, and cease all pruning operations well before any chance of a severe temperature drop. Do not prune peach and nectarine trees in the fall because of the ever-present threat of canker.

Summary of rules for pruning bearing trees

- Cut out broken, dead, or diseased branches.

- Where 2 branches closely parallel or overhang each other, remove the least desirable, taking into account horizontal and vertical spacing.

- Where possible, prune on the horizontal plane; that is leave those laterals on the main branches that grow horizontally or nearly so, and remove those that hang down or grow upward.

- Thin all varieties to permit thorough spraying and the entrance of sunlight and air.

- Where it is desired to reduce the height of tall trees, cut the leader branches back moderately to a well-developed horizontal lateral.

- Prune the lower branches of broadheaded or drooping varieties to ascending laterals.

- Varieties that tend to produce numerous twiggy, lateral growth should have some of this growth removed to prevent overcrowding.

- Make close, clean cuts. Stubs encourage decay and canker, thus forming a source of injury to the parent branch or trunk.

- Prune moderately. Very heavy pruning is likely to upset the balance between wood growth and fruitfulness, and generally should be avoided.

- Prune regularly. Trees that are given some attention each spring are more easily kept in good condition than trees that are pruned irregularly.

- Prune that part of the tree where more growth is required. This is particularly important with old trees. New growth will be stimulated only in those parts of the tree that were pruned. Reduce pruning to an absolute minimum where growth is already excessive.

- Do not remove a branch unless there is a very good reason for doing so. Leaves are the food-manufacturing organs, and if the leaf area is reduced unnecessarily, the tree will be reduced in growth or fruitfulness or both.