Report of the Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry

On July 17, 2018, the government announced the creation of an Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry. The Commission’s report looks at Ontario's current finances and past accounting practices to provide advice and recommendations for the current fiscal year (2018-19) and beyond.

Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry

7 Queen’s Park Crescent

Room FS-162, Frost Building South

Toronto, ON M7A 1Y7

Commission d’enquête indépendante sur les finances

7 Queen’s Park Crescent

Édifice Frost Sud, bureau FS-162

Toronto, ON M7A 1Y7

August 30, 2018

The Honourable Victor Fedeli

Minister of Finance and Chair of Cabinet

Ministry of Finance

7 Queen’s Park Crescent, 7th Floor

Toronto, Ontario

M7A 1Y7

The Honourable Caroline Mulroney

Attorney General and Minister Responsible for Francophone Affairs

Ministry of the Attorney General

720 Bay Street, 11th Floor

Toronto, Ontario

M7A 2S9

Dear Ministers:

Pursuant to our appointment as Commissioners of the Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry established by Order in Council 1005/2018 and in accordance with the mandate assigned therein, we are pleased to deliver the Commission’s report in both English and French.

It has been a privilege to serve on the Commission.

Sincerely,

Original signed by

Gordon M. Campbell

Chair

Original signed by

Michael Horgan

Commissioner

Original signed by

L.S. (Al) Rosen

Commissioner

Enclosure

Executive summary

The Commission’s intention is to establish a budgetary baseline for the new government as it sets its future plans.

Clear government publications, including the Public Accounts of Ontario, support the public’s right to understand the financial obligations of taxpayers and residents. The government and the Auditor General of Ontario have a mutual interest in assuring the Public Accounts fairly reflect the Province’s financial situation.

Unresolved disputes between the former government and the Auditor General over accounting practices can erode people’s faith in their public institutions. The Commission’s recommendations are intended to reduce uncertainty and enhance transparency.

A budgetary baseline is required for the current government to establish its own forward-looking fiscal policy. The Commission’s recommendations provide a starting point that reflects the most current information and highlights potential risks.

The Commission makes the following recommendations to government:

- Establish transparency for the taxpayer and general public as the top priority in preparing the Budget, Public Accounts and other financial reports. Ensure that accounting practices of the government are in accordance with the letter and spirit of Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards.

- Take an active role in the standards-setting process led by the Public Sector Accounting Board to identify and address accounting matters of particular importance to the Province.

- Restore a constructive, professional relationship between the government and the Auditor General in a manner that respects the Auditor General’s legislated independence.

- Require that the Auditor General is given advance notification and is asked for comment when a ministry or an agency consolidated in the financial statements of the Province proposes to engage a private-sector firm to provide accounting advice. In addition, require that the Province approve, after consultation with the Auditor General, the retention of the same private-sector firm for both accounting advice and auditing services.

- Engage the Auditor General in an effort to reach agreement on the accounting treatment of any net pension assets of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union Pension Plan.

- Adopt the Auditor General’s proposed accounting treatment for any net pension assets of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union Pension Plan on a provisional basis, until an agreement is reached between the government and the Auditor General. For the Public Accounts of Ontario 2017–2018, this would include restatement of the prior year’s figures for comparative purposes.

- Review the methodology for establishing fair market values for plan assets and the management assumptions used to determine long-term liabilities for the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union Pension Plan. Begin this work following the release of the Public Accounts of Ontario 2017–2018, and establish periodic reviews in the future.

- Adopt the Auditor General’s proposed accounting treatment for global adjustment refinancing, which is a major component of the Fair Hydro Plan.

- Revise the budget plan for 2018–19 to reflect the Commission’s proposed accounting adjustments, adjust revenue and expense projections based on the latest available information, and restore the reserve to at least the historical level of $1 billion.

| Item | Budget Plan 2018–19 | Revised Baseline 2018–19 | Impact on Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 152.5 | 150.9 | (1.5) |

| Total Expense | 158.5 | 164.9 | (6.4) |

| Surplus / (Deficit) Before Reserve | (6.0) | (14.0) | (8.0) |

| Reserve | 0.7 | 1.0 | (0.3) |

| Surplus / (Deficit) | (6.7) | (15.0) | (8.3) |

Table footnotes:

Note: Numbers do not add due to rounding.

Sources: Commission’s assessment based on 2018 Ontario Budget and internal data from the Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat.

- Establish a fiscal plan that includes near- and medium-term deficit targets and clearly describes how the government will achieve and report on these targets.

- Undertake a review of the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004 to improve its effectiveness in guiding government fiscal planning and reporting.

- Conduct analysis to determine and set an appropriate target and timeline to reduce the Province’s ratio of net debt to GDP.

- Set a long-term goal of restoring the Province’s AAA credit rating.

- Expand Ontario’s Long-Term Report on the Economy, published two years into each mandate, to include additional analysis on fiscal sustainability and set out the fiscal implications of current trends and future risks.

Defining the mandate

On July 17, 2018, the Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry (the Commission) was established by Order in Council 1005/2018 made under the Public Inquiries Act, 2009.

The Commission was directed to:

- perform a retrospective assessment of government accounting practices, including pensions, electricity refinancing and any other matters deemed relevant to inform the finalization of the 2017–18 consolidated financial statements of the Province; and

- review, assess and provide an opinion on the Province’s budgetary position as compared to the position presented in the 2018 Budget, in order to establish the baseline for future fiscal planning.

The Commission was directed to report on these matters to the Attorney General and the Minister of Finance by August 30, 2018.

The scope

The Commission:

- assessed whether the government’s past accounting practices provide an accurate picture of the Province’s finances;

- assessed whether the budget plan for 2018–19 is prudent and complete based on the latest information on revenues, expenses and risks, and government decisions to June 28, 2018;

- assessed whether the current fiscal planning framework supports the development of a practical fiscal recovery and sustainability plan; and

- identified opportunities to improve the fiscal planning process in the future.

The Commission’s advice is intended to inform the finalization of the Public Accounts of Ontario 2017–2018 and future fiscal planning. This report is not an audit.

The approach

The Commission asked the question: Do the government’s accounting policies, historical reporting and forward-looking plans properly illuminate taxpayers’ current and future obligations?

The Commission reviewed publicly available reports and information requested from ministries of the provincial government. The Commission also met with senior officials of the Ontario Public Service, the Auditor General of Ontario, the Financial Accountability Officer and others. All participants offered valuable perspectives to the Commission.

The content of this report is the independent view and advice of the Commission.

The work in context

The Province’s finances impact everyone who lives in Ontario. Government financial reports, including the Budget and the Public Accounts, should be reliable, comprehensive and understandable to taxpayers, government and elected representatives.

The impact of debt and borrowing

All government services and investments have corresponding costs to taxpayers. To pay for programs and services, the Province collects taxes and other revenues, and receives transfers from the federal government. When the Province runs a deficit, it is spending more than it collects and effectively it must borrow to make up the difference.

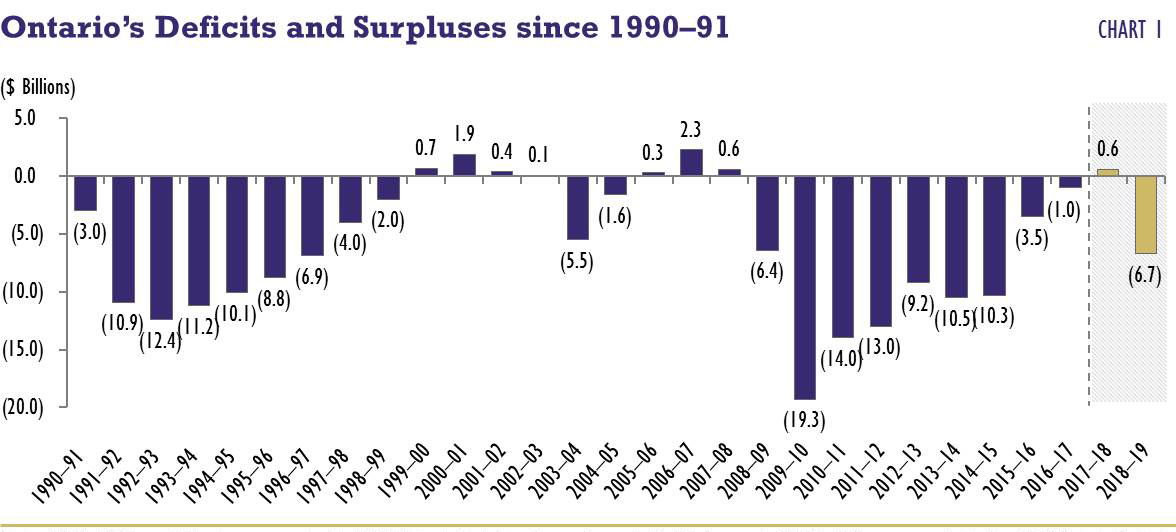

The 2018 Budget

Sources: 2018 Ontario Budget and Public Accounts data.

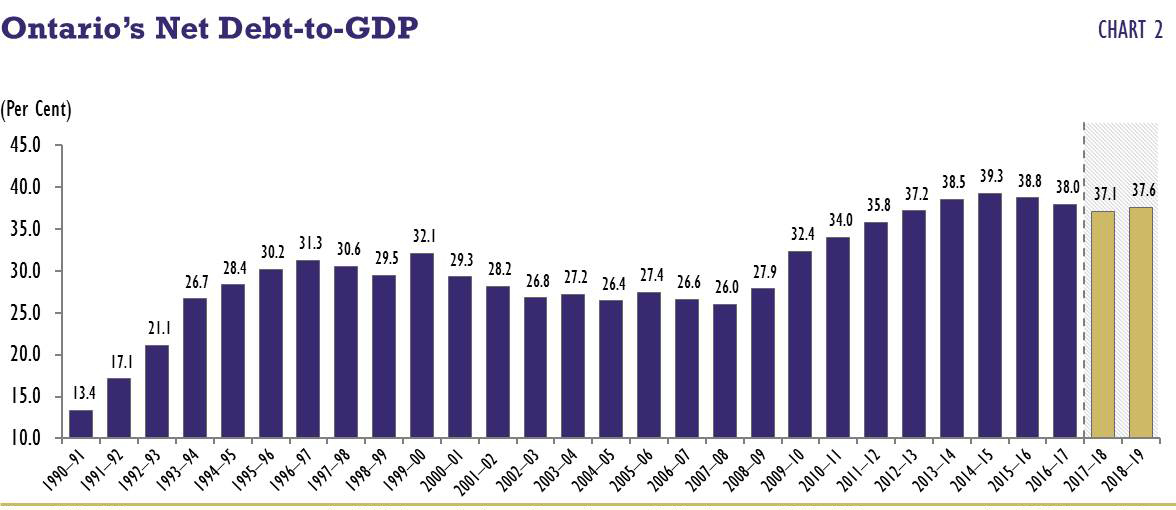

Why does the ratio of net debt to GDP matter?

The net debt-to-GDP ratio measures the government’s debt relative to the size of Ontario’s economy. It is a key indicator of the fiscal health of the Province and the government’s ability to meet its obligations. Credit rating agencies and investors place considerable emphasis on net debt when assessing the Province’s fiscal position.

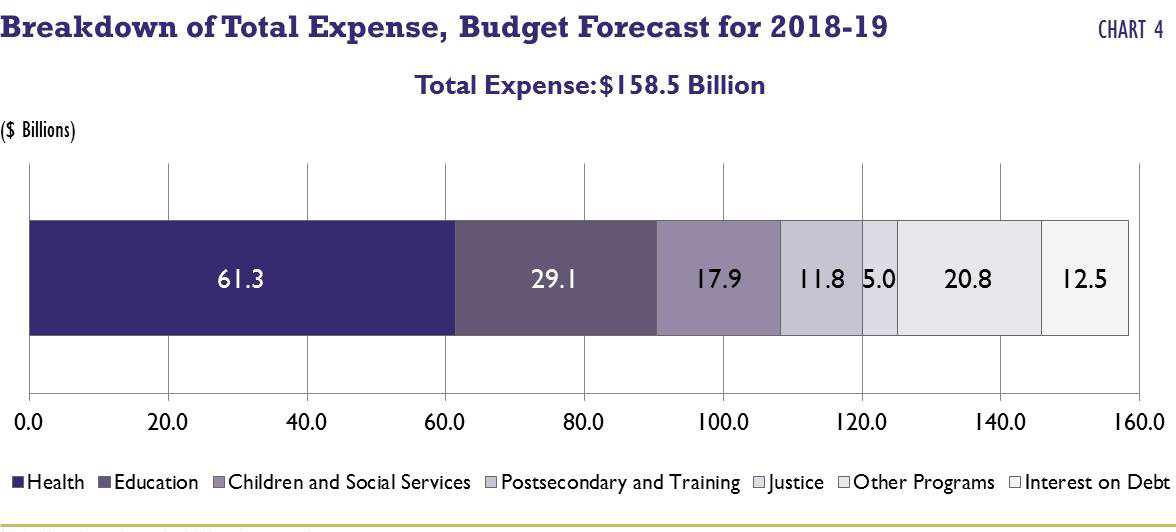

The cost of Ontario’s debt will increase if borrowing rates rise as expected. To manage its cost of borrowing, Ontario has issued approximately $10 billion per year of bonds with maturity terms of 30 years or longer since 2010–11, effectively locking in low interest rates. The 2018 Budget anticipated incurring $12.5 billion in interest costs in 2018–19. This means that 7.9 per cent of the Province’s total expenses would go to servicing the debt rather than paying it down, investing in new or enhanced services, or reducing taxes. These interest costs are more than twice the planned spending allocated to the former Ministry of Children and Youth Services in 2018–19, and are greater than the City of Toronto’s entire operating budget for 2018.

Interest rates are expected to rise in Canada in the years ahead, returning to levels closer to those of the past. Borrowing costs may also rise as the perceived risk of the government not meeting its obligations increases. All other things being equal, rising interest rates and borrowing costs reduce funding available for other priorities.

High levels of debt limit the government’s flexibility in responding to future economic downturns like the one in 2008–09. Net debt increased significantly during that downturn when automatic stabilizers, such as increased social assistance expenditures and decreased tax remittances, kicked in. In addition, the government took discretionary measures to stimulate the economy. Over the period of subsequent economic recovery, the ratio of net debt to GDP continued to rise and did not stabilize until 2015–16, when it fell modestly. The ratio remains significantly higher than its pre-recession level.

While predicting the next recession is difficult, planning for it is essential. Expecting the unexpected is prudent in today’s turbulent world. The Province should strengthen its fiscal position during periods of prosperity to ensure it has the flexibility to take action in response to any future downturn.

Borrowing gives rise to intergenerational equity concerns. Paying for programs and services Ontarians enjoy today through debt imposes costs on future generations for services they may never receive. However, borrowing to invest in hospitals, schools and highways spreads the costs over longer periods and aligns them with long-term benefits. Intergenerational inequities inherent in government decisions should be identified and made public, in part through transparent reporting.

Fiscal planning and financial reporting

The annual fiscal planning and reporting cycle starts with a Budget that sets out the plan for the year. It culminates in the Public Accounts of Ontario that compare actual results against the budget plan and prior fiscal year. The Public Accounts and other financial reporting documents should provide the people of Ontario with an understanding of the complete costs of government programs, how they are funded, who must pay for them, and the overall fiscal health of the Province.

The Auditor General and Financial Accountability Officer provide independent scrutiny of the quality and thoroughness of the government’s public disclosures. Their assurances and analyses are critical services provided to elected officials and the public.

In 2015–16 and 2016–17, the Auditor General issued qualified, or reserved, audit opinions on the government’s consolidated financial statements. This raised questions on the reliability of the government’s financial reporting. Confidence in the reliability of fiscal planning and financial reports prepared by the government is critical. Only a properly informed electorate can hold the government accountable for the decisions it makes. The recommendations in this report are intended to enhance public confidence and establish a baseline understanding of the current fiscal situation.

Assessing past accounting practices

Accounting frameworks guiding financial reporting differ depending on the types of entities involved and their jurisdictions. Each framework is designed to meet the needs of a specific set of users. For example, in Canada, governments and most government organizations prepare financial statements and reports using Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards (PSAS). In contrast, many publicly traded companies prepare their financial statements using International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (US GAAP), whereas privately held companies may use Accounting Standards for Private Enterprises (ASPE). Applying different standards, the same transaction can be reported in different ways. This can create significant problems in interpreting and comparing financial statements.

Canadian accounting frameworks are judgment-based, meaning standards are interpreted by practitioners. No standard is exhaustive. Where further guidance is needed, PSAS and other frameworks require and expect practitioners to exercise professional judgment, including consulting other sources, when determining how to fairly report financial transactions.

These accounting frameworks also leave room for accountants to interpret and apply standards differently, sometimes to the detriment of transparency. This can lead to confusion for users of financial statements.

The Commission believes that transparency is paramount. The question is not whether a particular accounting treatment can be justified, but whether it helps the public to fully understand the financial position of the Province.

The Commission considered the accounting arguments underpinning how the Province’s financial statements have been prepared over the last two years. The perspective and recommendations that follow are anchored in ensuring a faithful representation of the government’s finances to the public and applying a prudent approach to the treatment of uncertainty.

Guiding principles

The Commission believes that improvements in transparency are achievable and provides examples later in this document. It considers its advice to be consistent with the concept of “Reliability” as set out in the Chartered Professional Accountants Canada Public Sector Accounting Handbook.

Representational faithfulness, achieved when transactions and events […] are accounted for and presented in a manner that conveys their substance rather than necessarily their legal or other form;

and

Conservatism, when uncertainty exists, estimates of a conservative nature attempt to ensure that assets, revenues and gains are not overstated and […] that liabilities, expenses and losses are not understated.

Recommendation

Establish transparency for the taxpayer and general public as the top priority in preparing the Budget, Public Accounts and other financial reports. Ensure that accounting practices of the government are in accordance with the letter and spirit of Canadian Public Sector Accounting Standards.

The Province of Ontario has chosen to present its financial statements using PSAS. These standards are tailored to the users of government financial statements, including the general public, members of the Legislative Assembly, investors and bond raters.

The Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) oversees the development of PSAS and periodically reviews the standards to improve the quality of financial information available to the public. This ongoing review process helps ensure PSAS guidance is sufficiently clear on key issues. In the development of this report, it became apparent that further guidance from PSAB on a number of accounting standards would be beneficial, and the Commission encourages the government to seek such clarity.

Recommendation

Take an active role in the standards-setting process led by the Public Sector Accounting Board to identify and address accounting matters of particular importance to the Province.

The Public Accounts are key accountability and transparency documents, measuring actual financial results against annual budget plans. They include high-level summaries of the government’s activities, consolidated financial statements, financial information describing the results of individual ministries and financial statements of related organizations.

The Auditor General is an independent officer of the Legislative Assembly, governed by the Auditor General Act. The Auditor General scrutinizes government spending and reports to the Legislative Assembly to help its members assess the accuracy of the accounts and how effectively public resources are being used. This is an essential accountability mechanism for taxpayers and government alike. The Auditor General’s activities include an annual audit of the Province’s consolidated financial statements on which she provides an independent audit opinion. The Auditor General also conducts value-for-money audits throughout the year.

In the course of the Commission’s work, it became clear that, over time, there was a deterioration in the relationship between the government and the Auditor General. A constructive and professional relationship must be restored. Engaging in substantive discussions on significant accounting issues, sharing information while providing sufficient time for due consideration, and setting protocols on the engagement of third parties for accounting advice are key steps towards accomplishing this goal.

Recommendation

Restore a constructive, professional relationship between the government and the Auditor General in a manner that respects the Auditor General’s legislated independence.

Recommendation

Require that the Auditor General is given advance notification and is asked for comment when a ministry or an agency consolidated in the financial statements of the Province proposes to engage a private-sector firm to provide accounting advice. In addition, require that the Province approve, after consultation with the Auditor General, the retention of the same private-sector firm for both accounting advice and auditing services.

Recognition of net pension assets

One disagreement between the previous government and Auditor General concerns the treatment of certain assets related to two jointly sponsored pension plans. This section:

- provides a brief, non-technical overview of the issue;

- summarizes the positions of the former government and Auditor General; and

- sets out the Commission’s perspective and specific recommendations.

The Commission strongly believes that it is in the public interest that the government and Auditor General build a constructive working relationship and that they jointly work to resolve the professional disagreement over the interpretation of PSAS. Appreciating that these discussions will take time, the Commission recommends the government provisionally adopt the Auditor General’s accounting treatment until an agreement is reached.

Certain assets held by pension plans reflected in the Province’s financial statements are difficult to value (i.e., fair market values often do not exist). The government should review the processes by which the values of these pension assets are determined.

Background

The government sponsors several pension plans. Its obligations to these pension plans are reflected in the Province’s financial statements. Some of these plans, including the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and the Ontario Public Sector Employees’ Union Pension Plan, are jointly sponsored, where plan governance, contribution obligations and financial risks are shared equally between the government as employer and plan members or their representatives.

Net pension assets exist when estimated contributions to the plans — and investment income earned by the plans — exceed the estimated obligations to pay future retirement benefits. In accounting terms, these assets, when fairly valued, may provide a future economic benefit to the plan sponsors. For example, the sponsors may have effectively over-contributed to the plan, and provided appropriate mutually agreeable conditions are met, may be able to reduce their contributions in the future.

In 2015–16, a disagreement arose between the government and the Auditor General over whether the calculated net pension assets of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and the Ontario Public Sector Employees’ Union Pension Plan should continue to be recognized in the Province’s financial statements. The disagreement centred on whether the government is required to have unilateral control over its portion of the net pension assets. The government filed a time-limited regulation in fall 2016 to enable financial statements to be prepared in accordance with the Auditor General’s recommended treatment for 2015–16 and to allow time to research the issue further. The Auditor General subsequently issued a qualified audit opinion on the 2015–16 consolidated financial statements, citing the government’s failure to restate figures from 2014–15, which precluded a year-over-year comparison of financial results.

Subsequently, the government appointed a Pension Asset Expert Advisory Panel to provide advice on an accounting treatment for any net pension assets. On the basis of the panel’s advice

The Auditor General issued a qualified audit opinion on the 2016–17 consolidated financial statements. The opinion cited the government’s lack of unilateral control over these assets and failure to record a valuation allowance recognizing the uncertainty of its ability to unilaterally access net assets for the Province’s economic benefit. The Auditor General also expressed a view that the panel was not an authoritative source on the application of PSAS.

Why does the treatment of net pension assets matter?

Net pension assets reported in the government’s financial statements have an impact on the annual deficit and net debt of the Province. Adopting the Auditor General’s accounting treatment would have resulted in an annual deficit $1.4 billion greater and net debt $12.4 billion greater than the figures reported in the Public Accounts of Ontario 2016–2017.

The Commission’s perspective

To interested observers, it would seem reasonable that the government should be able to recognize a portion of an asset it jointly controls with another party. Given the risks and uncertainties involved, they may not feel it appropriate for the government to recognize its full 50 per cent share of the surplus. By the same token, however, it seems unlikely they would conclude the value to be zero.

The Commission notes the accounting guidance on the recognition of pension assets and recognition of pension liabilities is different. For pension assets, PSAS requires an assessment of any constraints on the government’s ability to reduce its future pension contributions. In practical terms, the actual value of any net pension asset is contingent on the government’s ability to take a full or partial contribution holiday. Funding considerations, including the liquidity of the assets in a given plan and the maturity of its membership, may limit the government’s ability to realize a benefit in the future. For the reasons described above, it seems possible that the portion that should be recognized may fall somewhere between the two extremes of 50 per cent and 0 per cent.

It is critical that the government and the Auditor General jointly seek to resolve these issues related to both control and measurement. The government’s decision to recognize its portion of the net pension assets did not resolve the issues raised by the Auditor General and resulted in a qualification.

Recommendation

Engage the Auditor General in an effort to reach agreement on the accounting treatment of any net pension assets of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union Pension Plan.

The Commission expects the proposed engagement with the Auditor General will take time. This raises the question of what to do in the immediate term, especially with the upcoming release of the Public Accounts of Ontario 2017–2018. The Commission believes such an agreement is possible and is in the public interest, but recommends the adoption of the Auditor General’s preferred accounting treatment as a provisional measure, similar to the approach that was taken in 2015–16.

Recommendation

Adopt the Auditor General’s proposed accounting treatment for any net pension assets of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union Pension Plan on a provisional basis, until an agreement is reached between the government and the Auditor General. For the Public Accounts of Ontario 2017–2018, this would include restatement of the prior year’s figures for comparative purposes.

The government and Auditor General generally rely on inputs from external auditors and actuaries for the calculations of pension expense and net pension assets. Asset valuations are inputs into these calculations and require specialized skills.

Many asset valuations rely on estimation because market values are not available.

In light of the ongoing disagreement over the recognition of any net pension assets and the significant dollars involved, the basis for the valuation of assets and liabilities of these plans needs to be examined more closely. While there was some discussion within the public service and the Office of the Auditor General on the valuation of pension liabilities, it would be prudent to also validate the valuations that underpin calculations of pension expense and net pension assets.

Pension expense calculations are complex and based on accounting valuations which use different assumptions than funding valuations. As a result, pension expense figures will not align with the required cash contributions to a pension plan, and net pension assets do not necessarily reflect the funded status of a plan. These actuarial calculations are performed using long-term economic assumptions on rates of inflation, return on investment and salary escalation. Pension expense and the value of any net pension assets can change dramatically depending on assumptions.

These considerations suggest the government should question and evaluate whether net pension assets are appropriately valued.

Recommendation

Review the methodology for establishing fair market values for plan assets and the management assumptions used to determine long-term liabilities for the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and Ontario Public Service Employees’ Union Pension Plan. Begin this work following the release of the Public Accounts of Ontario 2017–2018, and establish periodic reviews in the future.

Informed by any findings from the proposed review, the government may wish to consider extending the validation exercise to other pension plans that affect the Province’s consolidated financial statements (e.g., Public Service Pension Plan and the Ontario Power Generation pension plans).

In the course of its work, the Commission became aware of questions over whether the Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan is appropriately consolidated on the Province’s financial statements given its legal independence from government. The Commission acknowledges but does not express a view on this issue.

The Fair Hydro Plan and global adjustment refinancing

The Auditor General has articulated significant concerns with the government’s proposed accounting treatment for a major component of the Fair Hydro Plan, referred to as global adjustment refinancing. This section:

- provides a brief, non-technical overview of the issue;

- summarizes the positions of the former government and Auditor General; and

- sets out the Commission’s rationale in coming to its recommendation.

Evidence clearly shows the former government pursued a costly and convoluted implementation model. This arrangement was intended to provide a significant short-term reduction in residential electricity rates, while preserving the government’s ability to publish a balanced budget. The accounting issues are relevant but secondary to the lack of transparency, and the significant costs and risks inherent in the policy decision. The Commission recommends the government adopt the Auditor General’s preferred accounting treatment for global adjustment refinancing.

Background

Electricity prices in Ontario have increased steadily, outpacing the rate of inflation over the last decade. This trend reflects investments in generation, transmission and distribution infrastructure, and efforts to achieve environmental objectives through energy policy.

A typical residential electricity bill in Ontario comprises electricity, delivery and regulatory charges, and sales tax. The electricity charge includes both the wholesale price of electricity and the global adjustment, which for residential consumers is a flat rate applied to their consumption. The global adjustment covers the fixed costs of building and maintaining infrastructure, in addition to conservation and demand management programs.

In early 2017, the former government announced the Fair Hydro Plan, a suite of measures to provide electricity rate relief for today’s consumers. A key component of the plan was global adjustment refinancing: a time-limited, 16 per cent reduction on the average residential electricity bill, starting in July 2017.

This refinancing plan was intended to reduce rates today and pass the costs forward to future ratepayers. Under the plan, electricity prices are expected to be held to the rate of inflation through to 2021, after which rates are expected to increase more dramatically. The temporary reduction is financed through long-term debt, with the deferred global adjustment amounts, plus total financing costs, to be recovered from ratepayers in future years. Implementation of the plan was effected through the Independent Electricity System Operator (IESO) and Ontario Power Generation.

Under the Ontario Fair Hydro Plan Act, 2017 and its regulations, the IESO, which manages the electricity system, continues to pay generators at contracted rates. To provide rate relief to residential consumers, it collects a reduced global adjustment from Local Distribution Companies. The IESO records this shortfall as a regulatory asset on its financial statements as the legislation establishes a right to collect this shortfall from ratepayers in the future. The IESO then sells this regulatory asset to a financing entity created by Ontario Power Generation in exchange for cash. The transaction is financed through an equity injection into Ontario Power Generation from the government (44 per cent), a loan from Ontario Power Generation (5 per cent), and direct borrowing from capital markets (51 per cent), all of which is ultimately guaranteed by the Ontario government.

The Fair Hydro Plan was discussed in separate reports issued by the Financial Accountability Officer and the Auditor General. The Financial Accountability Officer

What is a regulatory asset?

A regulatory asset is reflected on a balance sheet. It represents a current cost of service that an organization is entitled to recover from future customers. Over time, the asset is reduced as payments are received. This entitlement is permitted by the regulatory body that oversees the prices the organization can charge for its services. In the absence of regulatory permission, the entity would be required to report the cost of service on its income statement as a current period expense.

The Auditor General also reiterated the view that the Province inappropriately recognized the IESO market accounts (i.e., amounts payable to suppliers that provide electricity to the market and amounts owing from users who consume electricity). This was one reason the Auditor General issued an overall qualified audit opinion on the Province’s 2016–17 consolidated financial statements. While not a basis for qualification, the audit opinion also noted that the IESO inappropriately adopted rate-regulated accounting, which was not in accordance with PSAS.

The Commission’s Perspective

While the Commission’s mandate is to review the accounting practices related to the refinancing proposal, it is not possible to divorce the discussion of accounting practices from the policy decision taken. The accounting and related financing arrangements were essential features of the proposal, meant to meet two objectives: reduce electricity rates and balance the budget.

The government’s desired outcome was that the electricity subsidy would be funded by ratepayers and therefore have no impact on the deficit or net debt. This requirement led the government to pursue a risky, complex and ultimately opaque implementation model.

At the time the 2017 Budget was released, Ontario already offered numerous programs providing electricity rate relief, funded by a combination of taxpayers and ratepayers. The implementation of global adjustment refinancing reduced transparency by preventing the costs of the planned electricity subsidies from being reported as expenses when they were incurred. In pursuing the appearance of a balanced budget, the government compromised the ability of its financial publications to support an informed debate over policy priorities and how best to spend limited dollars.

Global adjustment refinancing was designed using forecasts that reflect assumptions about future electricity demand and borrowing costs, especially over the long term. Unanticipated reductions in electricity demand (e.g., due to technological change or conservation), or increased interest rates, would lead to higher costs for future consumers. This could lead to pressure to transfer these costs to taxpayers rather than impose them on future ratepayers.

Even if the long-term modelling assumptions prove accurate, global adjustment refinancing is purposely structured to recover costs from ratepayers through Clean Energy Adjustments starting in 2021. From 2028 to 2047, repayment of deferred amounts and refinancing costs could result in electricity prices rising by as much as 9 per cent annually when compared against the forecast bill for a typical residential consumer without global adjustment refinancing. Ex post, these assumptions seem particularly implausible given that in the last election campaign all three major parties committed to significant electricity price relief for consumers over the next number of years.

Global adjustment refinancing also presents a risk that the global adjustment itself may be struck down as unconstitutional. The global adjustment is a regulatory charge, and one of the requirements of a valid charge is that individuals paying it benefit from the regulatory scheme. There is a risk that a court may find the global adjustment is not a valid regulatory charge if shifting costs over a longer period of time inadvertently results in future ratepayers cross-subsidizing today’s ratepayers.

The high degree of risk presented a significant challenge to raising financing from capital markets to pay for the regulatory asset. To ensure the debt being raised was financeable at commercial rates of interest, the Province was required to provide a limited guarantee to insulate investors against legislative, judicial and organizational risks. As a result, a number of credit rating agencies already treat this debt as Provincial debt. The guarantee is a good deal for bondholders, but not for future ratepayers.

The former government’s preferred presentation for global adjustment refinancing required recognition of the regulatory assets receivable, which it justified, in part, on the basis that PSAS is silent on the use of rate-regulated accounting. Rate-regulated accounting is applied by certain qualifying Government Business Enterprises (e.g., Ontario Power Generation and Hydro One) whose results are reflected in the Province’s financial statements based on IFRS, and who are subject to a rate-setting and approval process overseen by an independent regulator. However, the power contracts held by the IESO and the deferral mechanism established by the Ontario Fair Hydro Plan Act, 2017 are not subject to such processes, and the legislation does not grant the IESO its own rate-setting powers in this area.

As currently designed, there are significant risks to the government’s fiscal plan and a risk that the deferred amounts may not be collectible from future ratepayers. While including the complete costs of the Fair Hydro Plan as expenses on the Province’s books would not address these risks, it would increase transparency.

Recommendation

Adopt the Auditor General’s proposed accounting treatment for global adjustment refinancing, which is a major component of the Fair Hydro Plan.

With the presentation and reporting issues resolved, the government will need to determine how best to address the risks described above in a transparent and cost-effective manner as it sets its own electricity policies.

The Commission notes that global adjustment refinancing would result in financing costs up to $4 billion greater than if the government had financed the plan directly.

A note on the partial divestment of Hydro One

In its research into the electricity sector, the Commission became aware that the gain on the sale of Hydro One shares — the selling price less the carrying value recorded in the Province’s books — significantly reduces reported Provincial deficits in each of 2015–16, 2016–17 and 2017–18. These impacts were,

Government Business Enterprises such as Hydro One, Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation and the Liquor Control Board of Ontario are treated as financial assets under PSAS. The standards also require that gains or losses must be recognized on the sale of part of a Government Business Enterprise. As a result, time-limited gains or losses from sales of assets impact reported deficits and can compromise the usefulness of deficit figures as critical indicators of trends in the Province’s overall fiscal health.

The public deserves to know the long-term fiscal implications of these transactions for two reasons: they can mask underlying deficits, and they require the government to forgo future revenue from investments that have been built up over long periods of time. The above observations reinforce the importance of transparency in financial reporting.

Assessing the province’s budgetary position

The Ontario Budget outlines the government’s policy priorities and forecasts revenues and expenditures over the medium term (i.e., three fiscal years). When a deficit is forecast, the Province is required to include a recovery plan to return to balanced budgets.

The fiscal plan in any Budget is effectively the sum of a revenue forecast, minus a program expense forecast and an interest on debt forecast. As required by legislation, the Province’s fiscal plan must include additional prudence in the form of a reserve.

Components of the Budget

The 2018 Budget projected a deficit of $6.7 billion in 2018–19 and continued deficits over the medium term, from 2018–19 to 2020–21.

| Item | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 152.5 | 157.6 | 163.8 |

| Total Expense | 158.5 | 163.5 | 169.6 |

| Total Expense — Program | 145.9 | 150.4 | 155.8 |

| Total Expense — Interest on Debt | 12.5 | 13.1 | 13.8 |

| Surplus / (Deficit) Before Reserve | (6.0) | (5.9) | (5.8) |

| Reserve | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Surplus / (Deficit) | (6.7) | (6.6) | (6.5) |

Table 1 footnotes:

Note: Numbers do not add due to rounding.

Source: 2018 Ontario Budget.

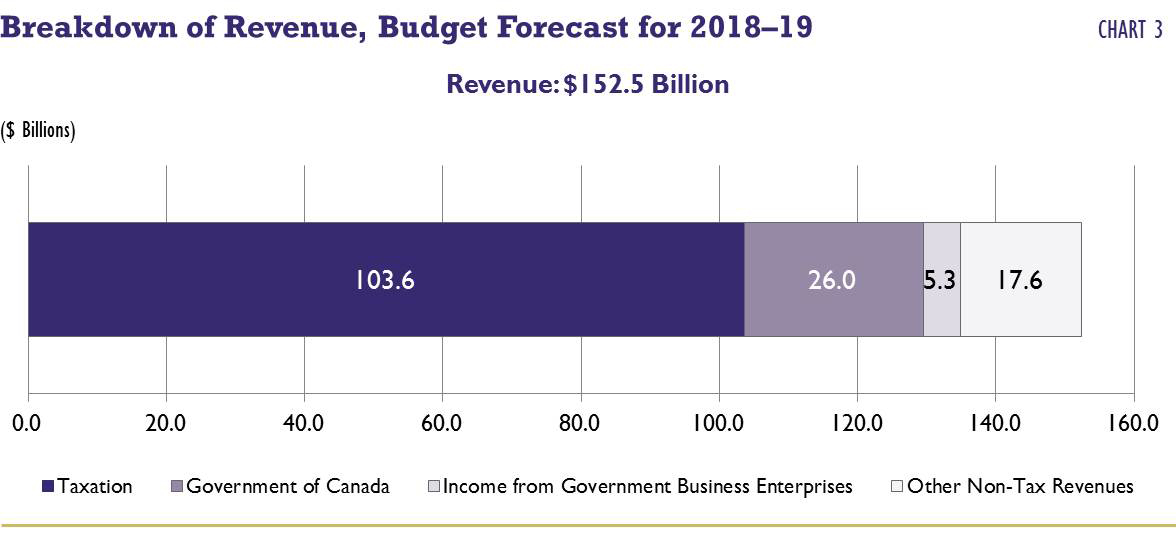

The revenue outlook is sensitive to the level and pace of economic activity.

The largest share of Ontario’s revenue is derived from taxation. The majority of tax revenue comes from personal income tax, sales taxes and corporations tax — all of which are subject to more volatility than other revenue sources. Other, relatively stable sources of revenue include transfers from the federal government for health and social services, non-tax revenue such as fees, licences and royalties, and revenues from Government Business Enterprises (e.g., the Liquor Control Board of Ontario).

The expense outlook consists of two main components, program expense and interest on debt. The program expense outlook reflects the Province’s plan to invest in government services and its policy priorities. It also includes a contingency fund for unexpected expenses that may arise during the fiscal year. The 2018–19 program expense outlook was adjusted downwards by two savings targets: a year-end savings target, reflecting anticipated efficiencies from managing project costs and implementation timelines; and an additional program review savings target to be met by implementing transformational initiatives within the fiscal year.

Interest on debt reflects the cost of borrowing to fund investments in capital infrastructure (e.g., highways and hospitals) and budget deficits. The interest on debt forecast includes separate prudence to mitigate the effects of marginal changes in borrowing rates.

Source: 2018 Ontario Budget.

Independent reviews of the 2018 Budget

As required under the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004, the 2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances was released on March 28, 2018.

On April 25, 2018 the Auditor General’s review stated that the Pre-Election Report was not a reasonable presentation of Ontario’s finances.

On May 2, 2018, the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario released a semi-annual Economic and Budget Outlook

Adjustments to the Budget Plan for 2018–19

If the government agrees with the Commission’s recommendations on accounting issues, there will be an impact on the deficit projected in the 2018 Budget. In addition, new information has become available that should be factored into a revised budgetary baseline for 2018–19. A description of these changes is detailed below.

| Item | Budget Plan 2018–19 | Revised Baseline 2018–19 | Impact on Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 152.5 | 150.9 | (1.5) |

| Total Expense | 158.5 | 164.9 | (6.4) |

| Surplus / (Deficit) Before Reserve | (6.0) | (14.0) | (8.0) |

| Reserve | 0.7 | 1.0 | (0.3) |

| Surplus / (Deficit) | (6.7) | (15.0) | (8.3) |

Table 2 footnotes:

Note: Numbers do not add due to rounding.

Sources: Commission’s assessment based on 2018 Ontario Budget and internal data from the Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat.

With these changes, Ontario’s net debt-to-GDP ratio in 2018–19 would be expected to grow from the 37.6 per cent reported in the 2018 Budget to 40.5 per cent. This estimate does not account for any incremental interest on debt costs resulting from the proposed revenue and expense adjustments.

Revised Revenue Outlook for 2018–19

Since publication of the 2018 Budget, updated economic and tax information became available and new risks have emerged that may impact revenues in 2018–19.

While 2018 Budget projections for real GDP growth were held below the average of those of private-sector forecasters, economic growth has been weaker than expected. As a result of the slow start to the year, the average of real GDP growth projections for 2018 by private-sector economists has declined from 2.3 per cent at the time of the 2018 Budget to 2.0 per cent.

Furthermore, the housing market was significantly impacted by federal mortgage rules that came into effect on January 1, 2018. Over the first half of 2018, both the quantity and prices of home resales were notably lower than previously anticipated and expected to impact land transfer tax revenues.

Personal and corporate tax revenue estimates have been adjusted to reflect updated forecasts of the impact of the recent increase in the minimum wage and the risk of businesses shifting income and investments to the United States due to lower tax rates. These changes are offset somewhat by updated information on 2017 personal income tax and corporations tax assessments.

These developments have led the Commission to recommend a modest reduction in the revenue forecast compared with the budget plan for 2018–19, as outlined in the table below.

| Item | 2018–19 |

|---|---|

| Revise Economic Growth Forecast | (0.4) |

| Revise Impact of Housing Market | (0.4) |

| Revise Impact of Minimum Wage Increase | (0.1) |

| Revise Impact of U.S. Tax Reform | (0.8) |

| Reflect Updated 2017 Tax Assessment Information | 0.2 |

| Projected Revenue Shortfall Relative to 2018 Budget | (1.5) |

Table 3 footnotes:

Source: Commission’s assessment based on internal data from the Ministry of Finance.

Potential risks to the revenue outlook

A risk to the Province’s revenue projections from the 2018 Budget is the impact of the outcome of the appeal of Ontario Energy Board’s recent decision on Hydro One Limited’s deferred tax asset

Additionally, economic uncertainty arising from ongoing trade negotiations and disputes outside of Ontario’s direct control may impact the Province’s revenue position in 2018–19 and beyond, given the importance of trade to Ontario’s economy, and the large proportion of its industries affected by tariffs and retaliatory measures, compared to the rest of Canada.

Neither of the above risks have been included in the proposed revisions to the revenue outlook due to the uncertainty of them materializing.

Revised expense outlook for 2018–19

As discussed earlier in this report, adopting the Auditor General’s proposed accounting treatment increases the expense outlook relative to the budget plan for 2018–19.

As of the end of the first quarter of 2018–19, the government had not yet identified specific measures to meet the year-end savings and program review savings targets built into the 2018 Budget. For the purpose of establishing a revised baseline for future fiscal planning, these targets have been reversed, increasing program expense. Any savings targets the government chooses to establish should be set based on their reasonableness in relation to the strategies government decides to employ.

| Item | 2018–19 |

|---|---|

| Provisionally adopt Auditor General’s accounting treatment of pension expenses | 2.7 |

| Adopt Auditor General’s accounting treatment of global adjustment refinancing | 2.4 |

| Reverse Year-End Savings and Program Review Savings Targets | 1.4 |

| Projected Expense Increase Relative to 2018 Budget | 6.4 |

Table 4 footnotes:

Note: Numbers do not add due to rounding.

Sources: Commission’s assessment based on 2018 Ontario Budget and internal data from the Ministry of Finance and Treasury Board Secretariat.

The proposed revisions to the expense outlook do not include any adjustments to the new initiatives announced in the 2018 Budget. The previous government’s budget increased total program expenses by $5.7 billion in 2018–19 and $20.3 billion over the medium term, reflecting new initiatives and updated forecasts for existing base spending. The government will need to decide whether these investments should be pursued, recalibrated, or cancelled as it undertakes its own fiscal planning process.

Potential risks to the expense outlook

The Commission reviewed information on financial approvals granted after the 2018 Budget was released and in the first quarter of 2018–19 where ministries were not directed to manage the associated costs from within their existing funding allocations. Furthermore, the Commission obtained updates to the expected costs of demand-driven programs such as the Ontario Student Assistance Program that are not reflected in the 2018 Budget.

The Commission has not included any of this information in the revised baseline for 2018–19 as it is reasonable to assume that expenditure management strategies and established prudence measures such as the contingency fund could be employed to mitigate the impact of these risks on the government’s expense outlook. Furthermore, first quarter expenditures were reduced due to the slowdown in government activities during the period leading up to and immediately following the provincial election. Therefore, the contingency fund, which was set significantly higher in 2018–19 than in the preceding eight years, is likely sufficient to cover expense risks for the remainder of the 2018–19 fiscal year.

Other emergent expense risks that cannot be quantified at this time include:

- outcomes of ongoing negotiations with respect to First Nation land claims;

- costs of environmental remediation;

- compensation for broader public sector employees; and

- cost-sharing arrangements with the City of Toronto for major transit investments.

These risks will have multi-year fiscal impacts on the Province, and therefore the Commission recommends that future planning efforts quantify them and prepare for expected incremental costs to the fiscal plan. Additionally, the revised expense outlook may not fully capture the impact of interest on debt costs resulting from the proposed adjustments to the budget plan for 2018–19.

Revised reserve for 2018–19

Reserve levels in five of the last seven years have been set at $1 billion. As part of a broader review of long-term fiscal planning practices, the Province should establish an appropriate level of the reserve and a methodology to account for risks related to economic uncertainty, and prepare for the next economic downturn. Uncertainty surrounding existing trade relationships such as the North America Free Trade Agreement should factor into the government’s decision-making around the amount of prudence it builds into its fiscal plan.

Recommendation

Revise the budget plan for 2018–19 to reflect the Commission’s proposed accounting adjustments, adjust revenue and expense projections based on the latest available information, and restore the reserve to at least the historical level of $1 billion.

While the Commission provides a baseline for fiscal planning in 2018–19, the government will need to clearly articulate its own medium-term fiscal plan and the specific actions required to achieve the fiscal targets it sets.

Recommendation

Establish a fiscal plan that includes near- and medium-term deficit targets and clearly describes how the government will achieve and report on these targets.

Long-term fiscal planning

The Province should carefully consider its approach to long-term fiscal planning. Sound fiscal planning extends beyond what is published in a Budget and recognizes how the financial decisions of today impact the long term. A key goal of fiscal planning should be to transparently articulate the objectives and the trade-offs implied in government decisions.

Recovery plan

The Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004 was intended to provide a framework for sustainable fiscal policy development and regular reporting, anchored on the objective of achieving balanced budgets. When the government decides a deficit is appropriate in a given fiscal year, the Act requires the development of a recovery plan for achieving a balanced budget in the future. The recovery plan published in the 2018 Budget projected a return to balance in 2024–25.

| Item | Medium-Term Plan 2018–19 | Medium-Term Plan 2019–20 | Medium-Term Plan 2020–21 | Recovery Plan 2021–22 | Recovery Plan 2022–23 | Recovery Plan 2023–24 | Recovery Plan 2024–25 | Recovery Plan 2025–26 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 152.5 | 157.6 | 163.8 | 169.5 | 174.9 | 180.4 | 186.5 | 192.9 |

| Total Expense | 158.5 | 163.5 | 169.6 | 174.4 | 178.2 | 182.2 | 185.8 | 189.6 |

| Total Expense — Program | 145.9 | 150.4 | 155.8 | 159.5 | 162.7 | 166.0 | 169.3 | 172.7 |

| Total Expense — Interest on Debt | 12.5 | 13.1 | 13.8 | 14.9 | 15.5 | 16.3 | 16.5 | 16.9 |

| Surplus / (Deficit) Before Reserve | (6.0) | (5.9) | (5.8) | (4.9) | (3.3) | (1.8) | 0.7 | 3.3 |

| Reserve | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Surplus / (Deficit) | (6.7) | (6.6) | (6.5) | (5.6) | (4.0) | (2.5) | 0.0 | 2.6 |

| Revenue Growth Rate | 1.5% | 3.4% | 4.0% | 3.5% | 3.2% | 3.1% | 3.4% | 3.4% |

| Program Expense Growth Rate | 6.1% | 3.1% | 3.5% | 2.4% | 2.0% | 2.0% | 2.0% | 2.0% |

Table 5 footnotes:

Note: Numbers do not add due to rounding.

Source: 2018 Ontario Budget.

The recovery plan in the 2018 Budget was constructed by applying an average annual growth rate for program spending of 2.0 per cent between 2021–22 and 2024–25, or about half of the average growth rate of program spending over the last 25 years. The question is whether this is credible with no specific plan of action or an understanding of how dramatically constrained program spending would affect individuals or programs and services.

While the recovery plan in the 2018 Budget met the base requirements set out in the Act, it did not provide Ontarians with an understanding of the policy implications of achieving a balanced budget. Without details of the policy choices that must be exercised to balance the budget, Ontarians cannot know what specific transformational changes, service reductions, or new revenue-raising capacity might be required to achieve it.

The recovery plan in the 2018 Budget calls into question whether the current legislative requirement to have a recovery plan is meaningful.

Recommendation

Undertake a review of the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004 to improve its effectiveness in guiding government fiscal planning and reporting.

Fiscal sustainability

Fiscal sustainability ensures the government is able to fund programs and services in a manner that is responsible, prudent and disciplined. In addition to the need for a recovery plan, the Act requires that government fiscal policy seek to maintain a prudent ratio of provincial debt to GDP. When the Act came into force, the net debt-to-GDP ratio was about 27.2 per cent.

The net debt-to-GDP ratio increased 4.5 percentage points within a single year after the onset of the 2008 financial crisis and over the subsequent recession, as the government acted to stimulate the economy and soften impact of the downturn. Currently, the ratio is more than 10 percentage points greater than the pre-recession ratio, despite sustained economic growth. The Province should aim to reduce its ratio of net debt to GDP during times of economic expansion so that it is prepared for any future economic downturn. This objective is consistent with the analysis of the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario.

While a zero deficit fiscal target is easier to communicate publicly, the Commission believes that the net debt-to-GDP ratio is a more meaningful measure of long-term fiscal sustainability. The Commission recognizes that significantly reducing the net debt-to-GDP ratio will likely require running budget surpluses which would be challenging in the near term. Nevertheless, the government should take immediate steps towards this goal. It should also report on its progress in all government fiscal and financial publications, including the Public Accounts.

Recommendation

Conduct analysis to determine and set an appropriate target and timeline to reduce the Province’s ratio of net debt to GDP.

As the government considers its fiscal policy objectives, the Commission encourages it to aspire to re-establish Ontario’s AAA credit rating as a long-term goal. Such a target would be broadly understood and would require the government to set achievable fiscal targets, establish plans to meet those targets and ultimately reduce the Province’s net debt-to-GDP ratio, reinforcing the Commission’s earlier recommendations.

Recommendation

Set a long-term goal of restoring the Province’s AAA credit rating.

Prudent decision-making requires an awareness of long-term trends and potential challenges on the horizon. The government should enhance its existing reporting

Recommendation

Expand Ontario’s Long-Term Report on the Economy, published two years into each mandate, to include additional analysis on fiscal sustainability and set out the fiscal implications of current trends and future risks.

Setting a path forward

Ontario faces significant challenges in the years ahead that will impact economic growth and the Province’s revenues and expenses.

In the near term, interest rates are expected to rise, which will put further pressure on Ontario’s housing market and constrain consumer spending, especially given elevated levels of household debt. Over the longer term, an ageing population will place additional pressure on already strained government resources. These are just two of the significant risks outside the government’s control. Others include:

- the rapid pace of globalization and technological change;

- recent tax reforms and protectionist trade policies in the United States;

- cybersecurity threats; and

- climate change.

In addition to these longer term challenges, the public will look to the government to help mitigate the impact of any short-term economic downturn. However, continuing deficits during periods of relative prosperity may reduce the scope of traditional fiscal stimulus to respond to changes in the business cycle.

While an economic downturn may not be imminent, the provincial government can demonstrate leadership today by creating the flexibility needed to respond effectively tomorrow. This requires setting fiscal targets and taking action to achieve them, whether by increasing taxes, decreasing spending or improving value for money.

These actions will also require a candid conversation with the public about priorities, and who will bear the costs for services that Ontarians enjoy today. Transparent public reporting that fairly represents the current and future obligations of taxpayers is critical in this context.

The Commission believes that Canada’s largest province can lead by example. While the Commission’s advice on accounting practices and a revised budgetary baseline provides a starting point, it now falls to the government to take action.

Order in Council

Executive Council of Ontario Order in Council

On the recommendation of the undersigned, the Lieutenant Governor of Ontario, by and with the advice and concurrence of the Executive Council of Ontario, orders that:

Conseil exécutif de l’Ontario Décret

Sur la recommandation de la personne soussignée, la lieutenante-gouverneure de l’Ontario, sur l’avis et avec le consentement du Conseil exécutif de l’Ontario, décrète ce qui suit:

Whereas under the Public Inquiries Act, 2009, the Lieutenant Governor in Council may appoint a Commission to inquire into any matter of public interest;

And whereas on April 25, 2018 the independent Ontario Auditor General released the "Review of the 2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances" (the Auditor’s Report);

And whereas the Auditor’s Report alleged that the government’s 2018 Pre-Election Report on Ontario’s Finances released on March 28, 2018, as required by the Fiscal Transparency and Accountability Act, 2004 and Ontario Regulation 41/18, was inaccurate in that expense estimates were understated for two items which would result in larger annual deficits than shown in the government’s report;

And whereas it was determined that it would be desirable and in the public interest to authorize under the Public Inquiries Act, 2009, and in the discharge of the government’s executive functions, a panel to conduct an independent assessment of the current state of the province’s finances and provide recommendations regarding prudent fiscal/budgetary and accounting practices;

and whereas it is considered advisable to set out the terms of reference for such an appointment and recommendations;

Therefore, pursuant to the Public Inquiries Act, 2009 it is ordered as follows:

Commission

- A commission is established to be known as the Independent Financial Commission of Inquiry (the "Commission"), effective the date of this Order in Council.

- Gordon Campbell, Al Rosen, and Michael Horgan are appointed as commissioners under section 3 of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009.

- Gordon Campbell is appointed as the Chair of the Commission. All Commissioners are jointly responsible for carrying out the mandate and producing the report.

Mandate

- Having regard to section 5 of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009, the Commission shall provide analysis and advice to inform the 2017–18 Public Accounts and an assessment of the Province’s budgetary position, and, in particular:

- Shall perform a retrospective assessment of government accounting practices, including pensions, electricity refinancing and any other matters deemed relevant to inform the finalization of the 2017–18 consolidated financial statements of the Province;

- Review, assess and provide an opinion on the Province’s budgetary position as compared to the position presented in the 2018 Ontario Budget, in order to establish the baseline for future fiscal planning; and,

- Shall report to the Attorney General and to the Minister of Finance on these matters by August 30, 2018.

- The Commission shall perform its duties without expressing any conclusion or recommendations regarding the potential civil or criminal liability of any person or organization. The Commission shall further ensure that the conduct of the inquiry does not in any way interfere or conflict with any ongoing investigation or legal proceeding related to these matters.

- Where the Commission considers it essential and at its discretion, the Commission may engage in any activity appropriate to fulfilling its duties, including:

- Conducting research and collecting information, including conducting interviews, as needed to fulfill its mandate, pursuant to clause 6(a) of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009; and,

- Consulting, with persons or groups, including the Auditor General and the Financial Accountability Officer, as needed to fulfill its mandate, pursuant to clause 6(b) of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009.

- The Commission shall, as much as practicable and appropriate, refer to and rely on the matters set out in section 9 of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009, and, in particular, pursuant to clause 9(1)(c) of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009, shall rely on any existing records or reports relevant to the subject matter of the Commission’s mandate as set out in this order.

- In accordance with the Public Inquiries Act, 2009, the Commission shall obtain all records necessary to perform its duties and, for that purpose, may require the provision or production of information that is confidential or inadmissible under any Act or regulation, other than confidential information which is described in sections 19 and 27.1 of the Auditor General Act. Where the Commission considers it necessary, it may impose conditions on the disclosure of information in order to protect the confidentiality of that information.

- The Commission shall follow Treasury Board/Management Board of Cabinet directives and guidelines and other applicable government policies unless in the Commission’s view and having regard to its mandate, it is not possible to follow them.

- The Minister of Finance is designated as the minister responsible for the Commission under clause 3(3)(f) of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009.

Report

- The Commission shall conclude its mandate and deliver a final report to the Attorney General and the Minister of Finance including any recommendations no later than August 30, 2018.

- In delivering its final report to the Attorney General and the Minister of Finance, the Commission shall ensure, in so far as practicable, that it is in a form appropriate for public release, free of any information that the Minister of Finance has identified as being confidential or privileged and consistent with the requirements of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act and other applicable legislation.

- The Commission shall be responsible for translation and printing and shall ensure that its final report is delivered in English and in French, at the same time, in electronic and printed versions.

Financial and Administrative Matters

- The financial and administrative support necessary to enable the Commission to fulfill its mandate shall be provided in accordance with sections 25, 26 and 27 of the Public Inquiries Act, 2009.

- All ministries and all boards, agencies and commissions of the Government of Ontario shall, subject to any privilege or other legal restrictions, assist the Commission to the fullest extent possible, including producing documents in a timely manner, so that the Commission may carry out its duties.

- The Minister of Finance shall make the Commission’s final report available to the public as soon as practicable after receiving it.

Attendu qu’en vertu de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques, le lieutenant-gouverneur en conseil peut nommer une Commission pour effectuer une enquête sur toute question d’intérêt public;

attendu que, le 25 avril 2018, la vérificatrice générale de l’Ontario a publié son « Examen du Rapport préélectoral sur les finances de l’Ontario 2018 » (le rapport de la vérificatrice);

attendu que le rapport de la vérificatrice indique que le Rapport préélectoral sur les finances de l’Ontario 2018 publié le 28 mars 2018 par le gouvernement, comme l’exige la Loi de 2004 sur la transparence et la responsabilité financières et le Règlement de l’Ontario 41/18, était inexact en raison de la sous-estimation de deux points des prévisions de dépenses, donnant lieu à des déficits annuels plus importants que ce que présente le rapport du gouvernement;

Attendu qu’il a été jugé qu’il était souhaitable et dans l’intérêt public d’autoriser, en vertu de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques et dans le cadre des fonctions exécutives du gouvernement, une formation à effectuer une évaluation indépendante de l’état actuel des finances de la province et à formuler des recommandations relativement aux pratiques fiscales/budgétaires et comptables prudentes;

Attendu qu’il est jugé utile d’énoncer le cadre de référence de cette nomination et de ces recommandations;

Par conséquent, en vertu de la Loi de 2009 sur /es enquêtes publiques, il est ordonné ce qui suit:

Commission

- Est constituée, à la date du présent décret, une Commission appelée Commission d’enquête indépendante sur les finances.

- Gordon Campbell, Al Rosen, et Michael Horgan sont nommés commissaires en vertu de l’article 3 de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques.

- Gordon Campbell est nommé président de la Commission. Tous les commissaires sont également responsables de l’exécution de leur mandat et de la production du rapport.

Mandat

- Compte tenu de l’article 5 de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques, le commissaire présentera des analyses et des conseils en vue d’éclairer les Comptes publics 2017-2018, fournira une évaluation de la situation financière de la province et, notamment:

- effectuera une évaluation rétrospective des pratiques comptables du gouvernement, notamment quant aux retraites, au refinancement du secteur de l’électricité et à tout autre secteur jugé pertinent pour étayer la finalisation des états financiers consolidés 2017-2018 de la province;

- examinera et évaluera la situation financière de la province, à l’aune de la situation présentée dans le budget de l’Ontario de 2018, et formulera un avis à cet égard, en vue d’établir une base pour la planification budgétaire à venir; et

- fera rapport au procureur général et au ministre des Finances quant à ces questions au plus tard le 30 août 2018.

- La commission s’acquittera de ses fonctions sans formuler de conclusions ou de recommandations quant à l’éventuelle responsabilité civile ou criminelle de toute personne ou de tout organisme. La commission veillera par ailleurs à ce que la conduite de l’enquête n’interfère ou n’entre en conflit d’aucune façon avec toute enquête ou toute instance en cours ayant trait à ces questions.

- S’il l’estime nécessaire, et à sa discrétion, la Commission pourra exercer les activités qui lui permettent de s’acquitter de ses fonctions, notamment :

- effectuer des recherches et recueillir des renseignements, y compris mener des entrevues, au besoin pour s’acquitter de son mandat, conformément à l’alinéa 6 a) de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques;

- consulter des personnes ou des groupes, y compris la vérificatrice générale et le directeur de la responsabilité financière, au besoin pour s’acquitter de son mandat, conformément à l’alinéa 6 b) de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques.

- La Commission se reporte aux documents énoncés à l’article 9 de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques et se fonde sur eux, lorsqu’il est possible et approprié de le faire, et en particulier, conformément à l’alinéa 9 (1) c) de cette loi, se fonde sur les dossiers ou rapports existants se rapportant à l’objet du mandat de la Commission établi dans le présent décret.

- Conformément à la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques, la Commission obtiendra tous les dossiers nécessaires à l’exécution de ses fonctions et, à cette fin, elle peut demander la communication ou production de renseignements qui sont considérés comme confidentiels ou non admissibles en preuve en vertu d’une loi ou d’un réglement, à l’exception des renseignements confidentiels décrits aux articles 19 et 27.1 de la Loi sur le vérificateur général. Si elle l’estime nécessaire, la Commission peut assortir de conditions la divulgation de renseignements, afin de protéger le caractère confidentiel de ces renseignements.

- La Commission suit les directives et lignes directrices du Conseil du Trésor/Conseil de gestion du gouvernement ainsi que les autres politiques gouvernementales applicables, sauf si, de l’avis de la Commission et à la lumière de son mandat, il est impossible de les suivre.

- Le ministre des Finances est désigné ministre responsable au regard de la Commission en vertu de l’alinéa 3 (3) f) de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques.

Rapport

- La Commission doit mener à bien son mandat et remettre son rapport final au procureur général et au ministre des Finances, y compris ses recommandations le cas échéant, au plus tard le 30 août 2018.

- Dans la mesure du possible, la Commission veillera à remettre son rapport final au procureur général et au ministre des Finances sous une forme appropriée pour sa diffusion publique, exempte de renseignements que le ministre des Finances juge comme étant confidentiels ou privilégiés, conformément aux exigences de la Loi sur l’accès à l’information et la protection de la vie privée et de toute autre loi applicable.

- La Commission assumera la responsabilité de la traduction et de l’impression de son rapport final et veillera à ce que ses versions française et anglaise soient présentées en même temps, en format électronique et sur papier.

Questions financières et administratives

- Le soutien financier et administratif nécessaire pour permettre à la Commission de s’acquitter de son mandat sera prévu conformément aux articles 25, 26 et 27 de la Loi de 2009 sur les enquêtes publiques.

- Sous réserve de tout privilège ou de toute autre restriction légale, tous les ministères, ainsi que tous les organismes, conseils et commissions du gouvernement de l’Ontario, prêteront leur concours à la Commission dans leur pleine mesure de façon que cette dernière puisse s’acquitter de ses fonctions.

- Le ministre des Finances rendra pulic le rapport final de la Commission dès que possible après l’avoir reçu.

[Signed]

Recommended: Attorney General

Recommandé par : La procureure générale

[Signed]

Recommended: Minister of Finance

Recommandé par : Le ministre des Finances

[Signed]

Concurred: Chair of Cabinet

Appuyé par : Le président/ du Conseil des ministres

Approved and Ordered:

Approuvé et décrété le : JUL 17 2018

[Signed]

Lieutenant Governor

La lieutenante-gouverneure

O.C./Décret: 1005 / 2018

Commissioners’ Biographies

Gordon M. Campbell, OC OBC

Chair of the Commission, Mr. Campbell is currently the Chief Executive Officer of Hawksmuir International Partners Limited and is Senior Counsel, Corporate Affairs, Edelman Public Relations Worldwide Canada Inc. He previously served as the High Commissioner for Canada to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from 2011 to 2016, and as Canada’s special envoy to the Ismaili Imamat from 2014 to 2016. Mr. Campbell was Premier of British Columbia for three terms, from 2001 to 2011, Chair of the Greater Vancouver regional District (now Metro Vancouver) from 1990 to 1993, and Mayor of Vancouver from 1986 to 1993.

Mr. Campbell was appointed Officer of the Order of Canada in May 2018 for his contributions to the province of British Columbia and for his distinguished public service. He was appointed to the Order of British Columbia in 2011. He is a recipient of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee (2003) and Diamond Jubilee (2013) medals. Mr. Campbell has two sons, two stepsons and five grandchildren.

Michael Horgan

Following a 36-year career in public service, Mr. Horgan is currently a senior business advisor at law firm Bennett Jones LLP. Mr. Horgan previously served as the Deputy Minister of four departments of the Government of Canada, most recently at the Department of Finance between 2009 and 2014. He has also served as the Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund for the Canadian, Irish and Caribbean Constituency, and as a director for a number of Crown corporations including the Bank of Canada, the Canadian Deposit Insurance Corporation and Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Mr. Horgan received the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal in 2013 and was awarded the Prime Minister’s Outstanding Achievement Award for Public Service in 2007. He was appointed a Mentor by the Pierre Elliot Trudeau Foundation in 2016 and served as Chair of the Principal’s Commission on the Future of Public Policy at Queen’s University in 2017–2018.

L.S. (AL) Rosen

Dr. Rosen is a founder and principal of Rosen & Associates Limited, an independent litigation and investigative accounting firm, and Accountability Research Corporation, an independent equity research firm. A member of the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants since 1960, Dr. Rosen is a fellow of the Chartered Accountants of Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia (FCA), a fellow of the Society of Management Accountants (FCMA) and a Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE).

Dr. Rosen is Professor Emeritus of Accounting at the Schulich School of Business at York University and has been an instructor and advisor at several other universities in Canada and the United States. He was also instrumental in founding the Canadian Academic Accounting Association. In addition to authoring numerous articles and columns, Dr. Rosen has written two books with his son Mark Rosen: Swindlers: Cons & Cheats and How to Protect your Investments from Them (2014) and Easy Prey Investors: Why Broken Safety Nets Threaten Your Wealth (2017).

ISBN 978-1-4868-2542-4 (PRINT)

ISBN 978-1-4868-2543-1 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4868-2544-8 (PDF)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2018

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph 2018 Ontario Budget, (2018), http://budget.ontario.ca/2018/index.html

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph City of Toronto, (2018), www.toronto.ca/city-government/budget-finances/city-budget/

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, CPA Canada Public Sector Accounting Handbook, Section PS 1000 Financial Statement Concepts, (2018).

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph Pension Asset Expert Advisory Panel Report, (2017), https://www.ontario.ca/page/pension-asset-expert-advisory-panel-report

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph Pension plans hold a variety of assets. Where there is an active market for these assets (e.g., publicly traded stocks or corporate bonds), the fair value can be easily determined. Where an active market does not exist (e.g., private equity investments), experts must rely on other valuation methods, estimates and assumptions.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph When combined with the Ontario Rebate for Electricity Consumers and the shifting of other programs to the tax-base from the ratebase, eligible consumers receive an average reduction of about 25 per cent.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, “Fair Hydro Plan: An Assessment of the Fiscal Impact of the Province’s Fair Hydro Plan,” (2017), http://www.fao-on.org/en/Blog/Publications/Fair_hydro