Requirements and guidelines for standards of care for dogs kept outdoors

Learn about the legal requirements and best practices for dogs kept outdoors to ensure they are safe and healthy.

Acknowledgements

This document benefitted greatly from feedback from a group of experts, including:

- veterinarians

- academics

- industry members

- agricultural organizations

- enforcement officers

- animal sheltering organizations

- animal advocates

The Government of Ontario recognizes the time and dedication of the members of its Outdoor Dogs Technical Table and Provincial Animal Welfare Services Advisory Table, as well as other organizations that provided their knowledge and expertise to help inform this guidance. These individuals committed their time and expertise to help positively impact the lives of dogs kept outdoors across the province. Thank you.

Background

Ontario’s animal welfare legislation and enforcement model

Ontario’s animal welfare legislation, the Provincial Animal Welfare Services Act, 2019 (PAWS Act) came into force on January 1, 2020. The PAWS Act enabled a new, fully provincial government-based animal welfare enforcement system and a modernized legislative framework for animal welfare in Ontario. Prior to the implementation of the PAWS Act, animal welfare laws were enforced by the Ontario Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (OSPCA), a registered charity focused on animal protection and advocacy, under the former Ontario Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1990 (OSPCA Act).

Ontario’s new animal welfare legislation is enforced by Animal Welfare Services (AWS) in the Ministry of the Solicitor General, which consists of a Chief Animal Welfare Inspector and locally deployed animal welfare inspectors who conduct inspections and investigations to help animals who are in distress or receiving inadequate care.

To facilitate implementation of the new legislation on January 1, 2020, regulations were carried over from the former OSPCA Act to the PAWS Act to ensure animals remained protected. One such regulation is Ontario Regulation (O. Reg.) 444/19, the Standards of Care and Administrative Requirements regulation.

The Standards of Care and Administrative Requirements regulation establishes minimum care requirements to help ensure that animals maintain good health and welfare. Currently, O. Reg. 444/19 sets out basic standards of care that apply to all animals that fall under the PAWS Act, including requirements for adequate and appropriate food, water, and medical attention and care. The regulation also establishes additional, more specific standards of care that apply to wildlife in captivity, primates in captivity, marine mammals and dogs that are kept outdoors.

Exceptions

The PAWS Act imposes a general requirement to comply with the standards of care set out in regulations under the act. There are two exceptions. The first exception is for agricultural activities, but only if those activities comply with reasonable and generally accepted practices for agricultural animal care, management, or husbandry. The second exception is for veterinarians providing veterinarian care or boarding an animal in accordance with the standards of practice established under the Veterinarians Act, 1990.

Purpose and context

This guidance document provides animal owners with information to help:

- understand the legally binding standards of care under the PAWS Act for dogs that are kept outdoors and for dogs tethered outdoors

- gain knowledge of best practices and guidance that can help owners apply the standards of care and take additional steps to help ensure the welfare of their dog(s). These best practices are recommendations only

Legally, under the PAWS Act, any person who owns, has custody of or cares for a dog that is kept outdoors or tethered outdoors must follow the requirements set out under O. Reg. 444/19.

Standards of care for dogs tethered outdoors

- Requirements are set out in section 4 of O. Reg. 444/19.

- Apply to a dog that is tethered for 23 hours in a 24-hour period, whether those 23 hours are consecutive or not, with limited exceptions.

Standards of care for dogs that are kept outdoors

- Requirements are set out in sections 4.1 to 4.5 of O. Reg. 444/19.

- Apply to a dog that is that is kept outdoors continuously for 60 or more minutes without being in the physical presence of its owner or custodian.

These requirements apply in addition to the basic standards of care that apply to all animals set out in section 3 of O. Reg. 444/19.

Requirements under the Standards of Care for Dogs Tethered Outdoors and the Standards of Care for Dogs that are Kept Outdoors are legally binding, meaning that penalties can be imposed for non-compliance.

Following the guidance and best practices in this document is not legally required but implementing the guidance and best practices may help owners to meet the requirements of O. Reg. 444/19 to help ensure the health and welfare of outdoor dogs.

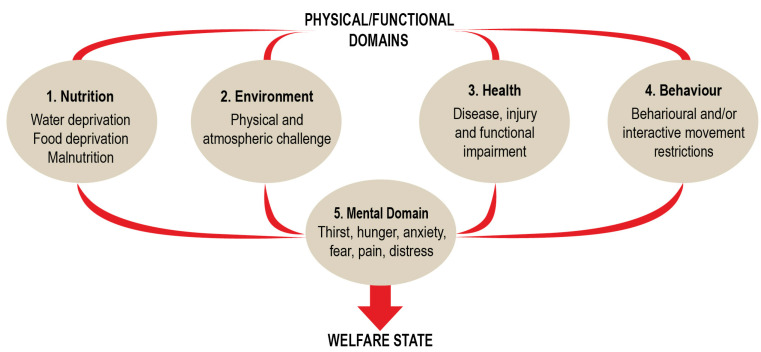

These requirements, guidance and best practices were informed by feedback from Ontario’s Provincial Animal Welfare Services Advisory Table and expert technical advice from veterinarian care, animal sheltering, industry, animal advocacy, enforcement and subject matter experts. They were also informed by jurisdictional reviews, academic literature and other best practice information, including the ‘Five Domains’ model (Mellor et al., 2020). The ‘Five Domains’ model is a framework for assessing animal welfare which recognizes that an animal’s experiences – including their nutrition, physical environment, health and behavioural interactions – can create negative or positive mental states. Good animal welfare should include both an animal’s physical and mental state of well-being and provide opportunities for animals to thrive, not simply survive. See Appendix A for additional information.

Application of the standards of care for dogs that are kept outdoors and dogs tethered outdoors

Ontario is home to many different types of dogs that are kept outdoors in both urban and rural areas. Dogs kept outdoors may be:

- companion dogs

- farm dogs

- sporting dogs

- working dogs

Owners may choose to keep their dog outdoors all the time or may only keep their dog outdoors for a period and then bring them in indoors (for example, choosing to keep their dog outdoors in the backyard for a portion of the day).

A dog is “kept outdoors” for the purpose of O. Reg. 444/19 if the dog is kept outdoors continuously for 60 or more minutes without being in the physical presence of its owner or custodian.

Summary of legal requirements

Any time that a dog is “kept outdoors”, owners must comply with the applicable standards of care for dogs that are kept outdoors. The standards of care can be organized into the following categories:

- general care of dogs kept outdoors

- shelter

- tethers

- housing pens

- tether and housing pen area

Owners must also meet the standards of care for dogs tethered outdoors any time they tether a dog for 23 hours in a 24-hour period, regardless of whether those 23 hours are consecutive or not, and regardless of whether the owner is physically present while the dog is being tethered.

1. General care of dogs kept outdoors

1.1 Shade and protection from the elements

Sun, rain, wind, snow and other elements can cause a dog to experience discomfort or even distress without adequate protections.

A dog regulates its body temperature differently than humans. Too much heat from the sun can cause a dog to become rapidly unwell. A dog may experience heat stroke, fatigue, or dehydration, which can result in injury or death.

Providing a dog with access to shade and shelter positively contributes to its welfare by allowing it to choose to roam, play or rest comfortably and seek shade to help regulate its temperature when needed.

Legal requirements

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (1) A dog kept outdoors must be provided with:

- sufficient protection from the elements to prevent the dog from experiencing heat or cold-related distress

- access to sufficient shade as may be required by the weather conditions, including sufficient shade to protect the dog from direct sunlight

Guidance and best practices

Heat and cold-related distress

Extreme temperatures can cause a dog distress even if the dog is at rest and not performing strenuous activities.

Dogs that are pregnant, whelping or nursing, or are puppies, geriatric, or ill may be more vulnerable to both heat and cold.

- Certain types of dogs, including Northern breeds and flat-faced (brachycephalic) dogs may have a more difficult time in the heat.

- When the temperature drops below freezing, some dogs may not be able to tolerate being kept outdoors for long periods of time and may experience frostbite or hypothermia.

- Short-coated dogs and small breeds are especially vulnerable in cold temperatures.

- Signs of heat and cold-related distress in dogs include:

Heat-related distress

- excessive panting

- increased drooling

- weakness

- muscle twitching

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- anxious or dazed look

- restlessness

- blue/purple or bright red gums

- stumbling, incoordination

- collapse

- seizure

- lethargy

- listlessness

Cold-related distress

- shivering

- rapid breathing that could progress to slow, shallow breathing

- increased urination

- the dog’s hair is standing on end (the equivalent of goosebumps)

- lifting paw off the ground

- listlessness

- disorientation

- pale gums, nose, ears, paws, or tail

- lethargy

Access to cool spaces and shade

Pavement, cement and sand surfaces can absorb sunlight and become a hot surface in the summer. Providing the dog with access to other, cooler surface options such as grass may assist in preventing heat-related distress.

Ideally, a dog should have the choice to access both areas of sun and shade. Winter sun can be a source of warmth and can have a positive welfare impact on dogs.

Access to shade can help protect a dog from:

- exposure to excessive heat

- direct sunlight to help prevent chance of sunburn and sun-related skin problems or skin diseases

Shade is particularly important during periods of warm weather.

A natural source of shade can consist of a tree or other greenery that provides an area of shade large enough to allow the dog to lie down with its legs extended to its full extent and stand up to its full height (with its head held at normal height) while being protected from the sun.

In the absence of a natural source of shade, the following can provide sufficient shade:

- installing a tarp

- covered platform

- awning

- canopy

- sun sail

Alternatively, strategically placing a housing pen beside a structure like a barn or building may provide shade for most of the day. These options could supplement the shade provided by the dog shelter, providing a more open and spacious shaded area.

Emergency management plan

Having an emergency and disaster management plan in the event of extreme weather can also help ensure that protection from the elements is available to dogs and can assist in preventing heat or cold-related distress. An emergency and disaster management plan may be particularly important for owners with multiple dogs.

1.2 Food and water containers

When selecting food and water containers for a dog kept outdoors, it is important to make sure containers are not susceptible to tipping and spilling of water or food, impacting the dog’s ability to access its food and water sources.

A dog’s behaviour can be a good indicator of what food and water containers will work for successful feeding and watering. If a dog exhibits behaviours that are destructive, clumsy or messy, research the different types of containers available, including different heights and materials, how they are insulated, and to ensure they are made of non-toxic materials.

Legal requirement:

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (2) Food and water containers used for a dog kept outdoors must be constructed to avoid injury to the dog and to avoid difficulty in accessing food or water.

Guidance and best practices

Regularly cleaning containers can help avoid contamination from food waste, debris, feces (also known as excrement) and urine.

Consider the size, breed, and abilities of the dog when selecting food and water containers to ensure the dog can access its food and water. For example, flat-faced (brachycephalic) dog breeds, such as bulldogs, sometimes have difficulty drinking and eating because of the shape of the dog’s face.

Consider safe ways to secure the container to the ground to prevent tipping and spilling. If a bowl is secured, ensure that there are no protruding screws or dangerous materials that can cause harm to the dog. Select a container that can be easily cleaned, repaired and replaced.

Consider the location of the container, and ensure that it is on a flat, level surface. If appropriate, consider placing the container along the edge of the housing pen or tether area so the dog is less likely to knock it over during activities like walking, stretching, or playing.

Consider the material and design of the container. Weighted containers with high edges are less likely to tip over and spill. Choosing a durable material is equally as important: rubber, stainless steel, and plastic are non-toxic, cost-effective solutions.

If puppies are accessing water containers, the container should not be so large or deep that puppies can fall in and drown.

1.3 Food

Food is a basic need that all dogs require daily to ensure good health. Daily nutrient requirements vary from dog to dog and can be based on the advice of a licensed veterinarian. Requirements can be impacted by the dog’s:

- age

- breed

- reproductive status

- environment

- physical fitness level

- daily routine

Insufficient food, or food that is poor quality, can result in negative health consequences, including malnourishment, exhaustion, frail bones, illness, and even death.

Factors, such as quantity of food, frequency of feeding, and composition of food and type of food storage containers used can have a significant impact on a dog’s overall health and welfare.

Legal requirement

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (3) A dog kept outdoors must be fed food that:

- reflects the dog’s daily caloric and other nutritional requirements

- is fit for consumption

- is not spoiled

- does not contain dirt, feces, urine or toxic substances

Guidance and best practices

Consult a licensed veterinarian to discuss which feeding schedule best supports a dog in each of its life stages. A good diet maintains an ideal body condition.

Body condition

Body condition can be a good indicator of whether a dog is eating a diet that meets its needs, or underlying issues with a dog’s health, such as lack of appetite due to illness.

Monitor for changes and ensure the dog maintains a healthy and balanced diet that meets its needs and nutritional requirements to maintain ideal body condition. See section 1.5 of this guidance document for more information on body condition scores.

Storing food

Consider storing food in a dry environment with a controlled temperature, and where pests and rodents cannot access the food. Improper food storage can cause spoilage of the contents with mould or other microbes. If a dog consumes spoiled food, it may result in serious illness or death. Regularly washing food storage containers reduces the likelihood of bacteria and mould build up.

1.4 Water

Continuous access to clean, fresh water is vital for the health and well-being of a dog. Having sufficient clean, fresh drinking water is crucial for:

- muscle retention

- lubricating joints

- supporting proper organ function

- aiding digestion

- minimizing the effects of overheating

- avoiding the symptoms of excessive thirst and dehydration

Dehydration is an extreme result of lack of access to water. It is important for a dog to have continuous access to water to avoid dehydration. In severe cases, dehydration can result in death. Lack of access to enough water can also contribute to heat stroke.

Legal requirement

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (4) A dog kept outdoors must have continuous access to water that:

- is replaced at least once every 24 hours

- is not frozen

- does not contain dirt, feces, urine or toxic substances

Guidance and best practices

Snow must not be used as a primary source of water. Consuming snow or licking ice may help relieve the sensation of thirst but does not provide the dog enough water to maintain good hydration. Consuming snow also reduces a dog’s body temperature and may lead to it consuming more calories to maintain its body condition.

Dehydration

Signs of dehydration in dogs include:

- loss of skin elasticity

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- increased fatigue

- panting

- fever

- dry eyes, nose, gums or mouth

Puppies, geriatric dogs, nursing mothers, and small breed dogs may be at increased risk of dehydrating more quickly due to the dog’s small size and metabolism. A licensed veterinarian can offer advice about how best to ensure a dog consumes enough fluids, based on the dog’s:

- age

- weight

- activity level

- health condition

Increasing the amount of water

While it is important that dogs have continuous access to water year-round, consider increasing the amount of water available when temperatures increase, particularly in hot weather as dogs expend more energy and experience greater water loss through panting and sweating.

If a dog is not drinking enough, try offering warm, flavour-enhanced water to help increase its water intake. Water can be flavour-enhanced by placing food or treats into it to encourage a dog to drink more.

Multiple dogs drinking from the same water station

If dogs are housed together and one dog is repeatedly showing symptoms of dehydration, an owner should consider more closely monitoring water intake and consulting a licensed veterinarian as may be necessary. Some dogs might drink excessive amounts of water or hover around or guard the water station, reducing the amount that other dogs are able to drink. Monitoring intake will help identify timid dogs that may not be getting enough water.

Preventing water from freezing

There are various tools or methods to maintain unfrozen water even in cold winter temperatures, including:

- corded heated water bowls

- rechargeable, cordless heated water bowls

- solar-heated water bowl

- heat blankets

- de-icers

- in-tank heaters

- building insulated boxes around water bowls

- providing larger, deeper containers of water

Owners should research products and tools prior to purchase to ensure safe and appropriate use for their dog based on the dog’s habits, temperament, and behaviour.

If the tool used to maintain unfrozen water contains electrical cords, ensure the cords are covered (for example, steel wrapped) to help prevent cord chewing that may lead to electrocution. Owners should research and seek out products or tools that meet electrical safety standards.

Preventing water from getting too hot

There are also strategies to help ensure water is an appropriate temperature in the summer months. For example, aim to keep water containers out of direct sunlight. Owners may also use an insulated bowl that does not conduct heat or add ice blocks to cool the water.

1.5 Health and welfare checks

A daily inventory of a dog’s body condition and behaviour and reporting any health changes to a licensed veterinarian is a vital part of overall health maintenance. It is particularly important for dogs kept outdoors since they can be exposed to extreme temperatures, weather changes and are at risk of being injured by predators.

There are several forms of preventative care that can help promote a healthy life:

- accessing veterinarian care

- maintaining up-to-date vaccinations and administering oral medications as needed to prevent parasites and infections

- monitoring the dog for changes in behaviour, injuries, or changes in body condition

Regular health assessments by a dog’s owner can help ensure a better quality of life and help avoid pain, sickness, and discomfort. Inspecting a dog’s health does not need to be a time-consuming task as it can occur each day during the times an owner provides water, food, exercise or play time.

Legal requirement

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (5) An owner or custodian of a dog kept outdoors must ensure that the health and welfare of the dog is checked daily

Guidance and best practices

Daily health checks

Daily health checks can be performed visually, as well as physically. Daily checks help ensure dogs kept outdoors maintain good health and avoid the impacts of long-term injuries or illnesses left unattended.

If there is a change in a dog’s behaviour, owners should conduct a physical examination of the dog’s legs, paws, teeth and body to ensure there are no underlying health concerns. Limping, a lack of appetite, or an unwillingness to engage in regular activities are examples of a change in a dog’s behaviour that might indicate an underlying health issue.

Individuals can physically assess a dog’s health by using open palms to gently pat its body down, slowly working around each joint to check for any injuries. Be aware that dogs may experience seasonal coat, appetite or physical changes.

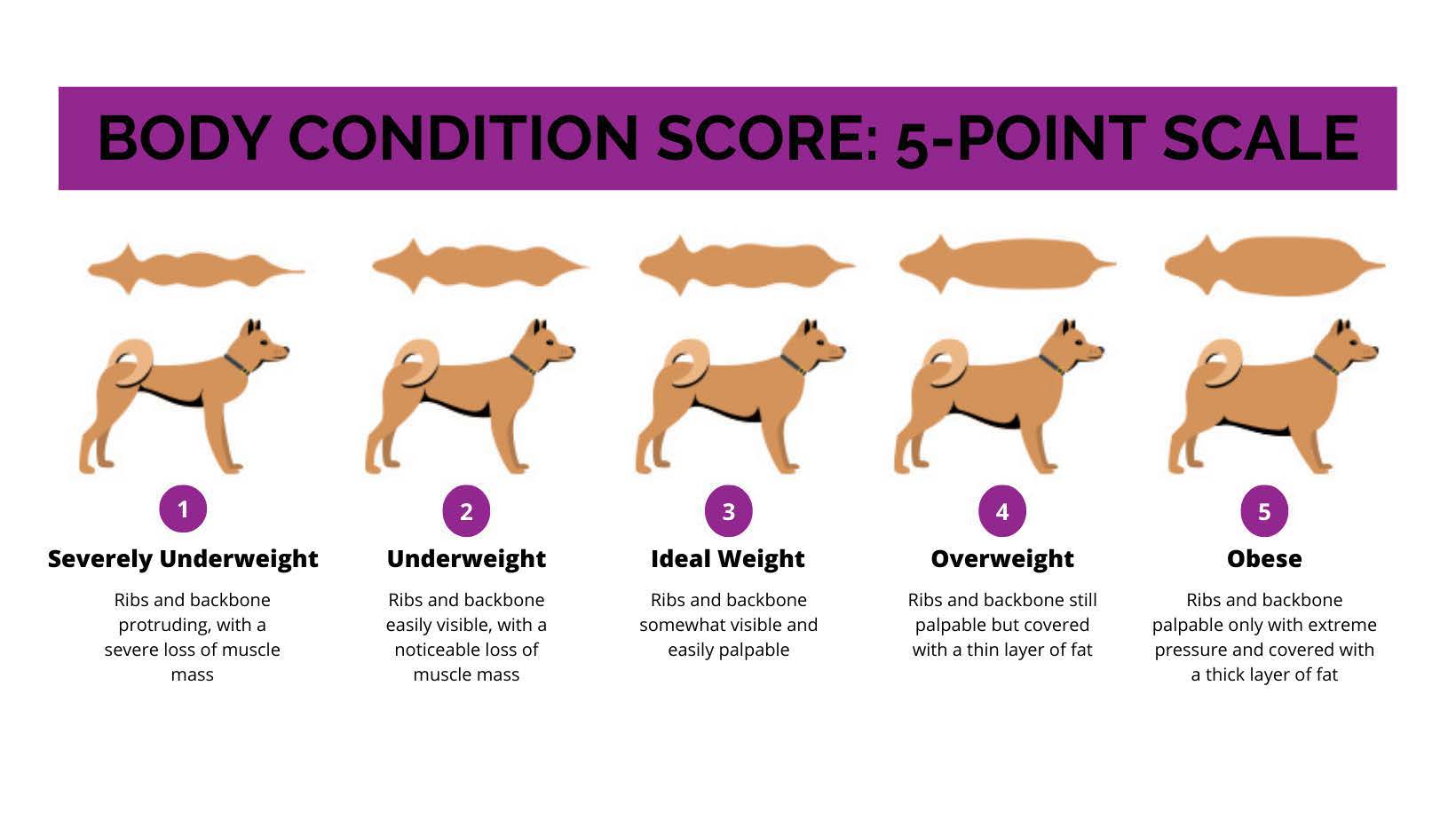

Body condition scoring

Body condition scoring is one tool that can help to assess a dog’s general welfare based on its fat and muscle coverage. Body condition can vary with a dog’s breed, activity level and age. Body condition scoring is a hands-on examination that measures how thick the fat and muscle covering are on a dog by using a pre-determined scale (see Appendix B).

Body condition is measured by a body condition score (BCS) system. There are several types of BCS measurement systems including a 5-point scale and a 9-point scale. For reference, the following is based off the 5-point scale:

- A BCS of 1 indicates that an animal is severely underweight, which poses negative health risks (for example, starvation, malnutrition, or frail bones).

- On the opposite side of the scale, a BCS of 5 indicates an animal is severely overweight, which also poses negative health risks (for example, arthritis, diabetes, cancer, heart disease or limited mobility and ability to engage in natural behaviours).

- An ideal BCS is 3 out of 5.

- A dog with a BCS of 3 will have ribs and a backbone that are somewhat visible and easily felt, and a waistline with gradual curves.

- A consultation with a licensed veterinarian is recommended if a dog has a body condition score of less than 2 or greater than 4, as it may signal health concerns and may require a specific plan to achieve an ideal BCS.

Other health factors and signs of illness

Weight and body condition are not the only factors in assessing a dog’s welfare. Owners should also monitor for other changes in the dog’s general condition (for example, skin, ears, eyes, coat and nail condition), behaviour and whether it is eating, drinking, urinating and defecating normally.

For owners that have multiple dogs, consider the benefits of keeping records of findings during daily health checks to help differentiate each dog’s medical history.

Prompt veterinary care should be sought for all dogs showing signs of injury, illness or pain. Signs of illness include:

- lack of appetite or decreased activity

- vomiting

- diarrhea

- urinating more or less frequently

- coughing

- sneezing

- discharge from the eyes, ears or nose

Vaccines and mediations

Vaccinations and anti-parasitic medications are a safe and effective way to protect dogs kept outdoors from contracting specific, preventable illnesses, or diseases caused by viruses or bacteria. Ontario has a range of different climates and geographies. Owners may want to ask a licensed veterinarian about the risk of viral and bacterial diseases in their area, and what type of vaccines or preventative medications may be necessary particularly if the dog is kept outdoors regularly.

Annual veterinarian examinations

Annual physical examinations by a licensed veterinarian are a best practice. By performing an annual exam, a veterinarian can detect early signs of injury or illness (for example, organ dysfunction, dental disease, tumors, or arthritis). With early diagnosis can mean early treatment, prevention of pain and distress, and improved chances for a long and healthy life.

1.6 Grooming and nail care

Dogs can have varying grooming needs based on the dog’s type of coat. Neglecting to provide proper grooming can cause adverse health effects, such as:

- increased risk of skin sores

- infections

- dermatitis

- hair loss

- pain that limits a dog’s mobility or prevents the detection of parasites

Monitoring the length of the dog’s nails and dewclaws regularly can avoid discomfort, injury and protect them from potential infections. Overgrown nails can penetrate the skin which can put extra pressure on the digits resulting in pain and stress on the dog’s paw pads. In severe circumstances, the nail can grow to the point where it curls and implants itself into the dog’s paw pad, causing severe discomfort and potential infection.

A dog’s paw and pad help protect its body as it stands, walks, runs or jumps by absorbing shock and pressure to protect bones and joints from rough terrain or trauma. A dog’s paws also help maintain its core body temperature due to a heat exchange system located in its paws. If a dog’s paw is injured, this ability to regulate temperature is less effective which can cause discomfort or distress.

Legal requirements

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (6) A dog kept outdoors must be groomed as necessary to avoid matting of the dog’s coat and the accumulation of ice or mud on the dog’s coat or under the dog’s paws.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (7) The nails of a dog kept outdoors must be checked regularly and groomed as necessary for the health of the dog.

Guidance and best practices

It is important to inspect and maintain a dog’s coat regularly to ensure it is clean and unmatted and does not cause other issues such as blocking the dog’s vision. Brushing a dog’s coat frequently will help reduce shedding and matting.

Seasonal grooming

Owners may wish to adjust grooming routines to suit the seasons. Grooming is particularly important in the winter months for long-haired dogs as ice can accumulate on the fur, including in between the paw pads, and cause infections that may be painful and difficult to see. In other seasons, burrs (for example, small spikes that are found on many weeds) can be caught on a dog’s coat and should be removed through regular grooming.

Certain body parts require additional grooming during certain seasons. For example, in the winter it is important to pay extra attention to a dog’s paws for salt, snow, or dirt build up. In the spring and summer, it is important to examine a dog’s skin (particularly under a dog’s legs) as humidity and friction can cause sores, known as hot spots, that can lead to skin infections. Maintaining clean, groomed limbs will reduce the likelihood of sores and infection.

Groom around the anus and tail year-round to avoid common parasites (for example, flystrike).

Nails and pads

When a dog’s nails are so long that they touch or drag on the ground most or all the time, it may cause the toes (digits) to move from their normal alignment. A dog should be able to stand relaxed on a hard, flat surface with its toenails not quite touching the surface. The dewclaw should also be checked regularly, as it is prone to cracks, breaking or tearing that could lead to infection.

Signs of paw or nail injuries include limping, paw lifting, lack of use of the paw, excessive licking or discolouring of the hair on the paw.

1.7 Keeping ill and injured dogs outdoors

It may be inappropriate to keep sick or injured dogs outdoors because outdoor conditions can:

- worsen an injured or ill dog’s health and recovery

- increase the chance of infection

- heighten the likelihood of being approached by a predator or exposure to other stressors

Legal requirement

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (8) A dog shall not be kept outdoors if it has an illness or injury that affects the dog’s ability to regulate its temperature or restricts its mobility, unless a veterinarian advises, in writing, that it may be kept outdoors.

Guidance and best practices

Owners should seek prompt medical care from a licensed veterinarian if they suspect the dog is:

- injured

- ill

- suffering from a contagious disease

- exhibiting other signs of distress, such as being in pain or suffering

A licensed veterinarian can help advise on whether a dog’s illness or injury may restrict its mobility or impact its ability to regulate its temperature.

If a dog has an illness capable of spreading to humans (known as a “zoonotic” illness), consider whether that dog should be quarantined indoors away from people, particularly children and immunocompromised people who may be at greater risk.

Consider the physical environment where a dog is being kept and whether there are potential predators that can enter its pen or tethering area and attack it while it is ill or injured and unable to properly defend itself.

Extreme weather conditions (for example, based on a weather warning or watch by Environment Canada) may negatively affect a dog kept outdoors that is already ill or injured.

1.8 Quarantine

Quarantine can prevent the spread of contagious diseases. A quarantine is the act of separating individual animal(s) to prevent the spread of disease for a specified period of time until the animal is no longer contagious, and to observe for signs of illness.

Legal requirements

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.1 (9) to s. 4.1 (12) If the owner or custodian of a dog kept outdoors has grounds to believe that the dog is suffering from a contagious disease or is at high risk of developing a contagious disease, the dog must be kept completely isolated from other dogs and must not have contact with objects, including food and water containers, that are used by other dogs or animals.

- A dog does not have to be isolated to the extent that a veterinarian advises, in writing, that compliance with these requirements is unnecessary.

- Puppies do not need to be isolated from their mother or substitute mother if they are less than 12 weeks old.

- A dog does not have to be isolated from other dogs that either suffer from the same contagious disease or are at high risk of developing the same contagious disease, and the dog does not have to be prevented from having contact with objects used by those other dogs.

Guidance and best practices

Dogs kept outdoors may be exposed to various contagious diseases that may spread through virus particles in the air, contaminated objects, or direct bodily contact between dogs. Owners may wish to consult a licensed veterinarian for more information about contagious diseases in their area and how they can spread to dogs.

Designated materials

Where an outdoor dog is quarantined, separate cleaning materials and equipment should be designated solely for the quarantine area.

Food and water bowls should be designated for use solely in the quarantine area and should be cleaned in a sink that is disinfected after use.

Cleaning and sanitation

Disinfectants should be non-toxic so they cannot harm a dog and be used in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations. If potentially toxic cleaning products are used, ensure the products are thoroughly rinsed or removed off the object or surface by performing a second cleaning using soap and water.

Sanitation and hygiene protocols should be strictly applied to the quarantine area, including all reusable bedding and clothing.

Caring for sick dogs

When caring for a sick dog, owners should wash their hands immediately after touching the dog, cleaning dishes, toys, or removing waste material or bedding to limit potential spread of disease.

When caring for two groups of dogs, one that is healthy (or has not been exposed to illness) and one that is ill, consider entering the quarantine area(s) containing ill dogs last to minimize the chance of contaminating other housing areas or dogs.

2. Shelter

An outdoor dog shelter, commonly known as a doghouse, offers protections from changing weather conditions and unwanted stimuli. A doghouse is also a quiet and comfortable place for a dog or multiple dogs to rest and seek privacy. Multiple dogs may share one dog shelter, if the legal requirements set out below are met.

A properly constructed doghouse promotes a comfortable temperature and creates conditions that allow for rest, relaxation and sleep. There are various aspects to consider when building or selecting the appropriate doghouse because a doghouse is such an important resource for dogs kept outdoors.

Livestock guardian dogs

Livestock guardian dogs who live with the flock or herd they are protecting do not require a doghouse as they receive protection from the elements and shelter from living along- side the livestock. For example, livestock guardian dogs will burrow into the centre of the flock to block out wind. A “livestock guardian dog” under the regulation is a dog that is identifiably of a breed generally recognized as suitable for protecting livestock from predators and who lives with a flock or herd of livestock. Examples of common livestock guardian dog breeds include, but are not limited to:

- Great Pyrenees

- Maremma

- Komondor

- Akbash

Additionally, dogs that have access to a building that is actively housing livestock, such as a barn, have an available shelter that provides warmth and protection and do not require a doghouse.

Legal requirements

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.2 (1) Every dog that is kept outdoors must, at all times, have ready access to a shelter that:

- is waterproof and provides protection from the elements

- is structurally sound, stable and free of features that might cause injury to the dog

- has an insulated roof

- has a floor that is level, elevated from the ground, and dry

- has a means of providing ventilation, which may include an open doorway

- is of a size and design that permits all of the dogs that regularly use the shelter to turn around, lie down with their legs extended to their full extent and stand with their heads held at normal height when all of the dogs are occupying the shelter at the same time

- has a doorway that is free from obstructions

- contains bedding that

- is at least three inches thick, and

- is changed as frequently as necessary to ensure that the bedding remains comfortable and substantially clean, dry and unsoiled

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.2 (2) The requirement that every dog that is kept outdoors must, at all times, have ready access to a shelter that meets the specifications above does not apply to a livestock guardian dog or to a dog that has ready access to a structurally sound building that, at the time, is being used to house livestock.

Guidance and best practices

Protection from the elements

Consider the position of the doghouse and how it interacts with the elements including the sun, shade and wind. For example, to reduce drafts in the doghouse, consider positioning the door in the opposite direction of the prevailing wind. The direction of prevailing wind can change throughout the year, but local weather networks can identify trends in prevailing winds that can help owners decide how to best position the door.

For example, in 2020, the wind in Thunder Bay came from the north for over seven months, and the west for 2.5 months. In these conditions, facing the door towards the south or east in this example would best protect the dog from wind.

Doors and doorway coverings

Doors and doorway coverings for a doghouse can be used to provide additional weather protection in the winter and can be removed in the summer. There are several styles of doghouse doors or doorway coverings, including:

- single-flap barn doors

- saloon doors

- soft-flap entry doors

- curtain doors

- mechanically controlled door

Each style of door has different limitations regarding:

- usability

- insulation and temperature control

- outdoor visibility

- durability

It is recommended that the owner do appropriate research before installing a door or doorway covering. Another option to help protect from wind and the elements is to use a doghouse that contains a hallway.

Be aware that snow build-up at the entrance of a doghouse may prevent a dog from accessing its shelter.

Insulation

Insulation in the roof of a doghouse can benefit a dog in all seasons. In winter, insulation will help to keep a dog’s body-generated heat in the doghouse, helping to maintain a comfortable temperature. In the summer, insulation helps to maintain cool air within the doghouse by acting as a barrier to reduce the amount of heat that is able to enter the doghouse.

There are several tactics to deter a dog from chewing insulation that may be appropriate including covering the insulation with a durable panel (for example, wood or rubber). Other options include non-toxic taste deterrents, such as a bitter apple anti-chew spray that can be applied to the insulation.

Pregnant, geriatric, small or short-coated dogs, and puppies may have a more difficult time regulating their body temperature. Consider providing additional insulation in the doghouse in the winter such as when the temperature is below 0°C for these vulnerable dogs.

Placement of shelter

Select a level area when building or positioning a doghouse. Avoid soft ground and areas that are prone to flooding such as grass near a water source, or a location that is at the bottom of a hill.

Consider the placement of the doghouse relative to the containment area. For example, if a doghouse is placed too close to a fence, a dog may climb onto the roof of the doghouse and use it to jump over the fence and escape.

Elevation

Elevating the doghouse can help:

- reduce the impact of flooding

- reduce the risk of rotting floors

- provide additional insulation

One option is to use concrete, bricks or cinder blocks to elevate the doghouse and help keep the floor dry.

Ventilation

Ventilation and air flow in a doghouse are important in all types of weather. In hot weather, proper air flow can prevent a dog from overheating. In cold weather, air flow can prevent moisture accumulation and the formation of mould.

Shelter size

It is important to be aware that a dog’s body will continue to change as they age, so research and consider the dog’s breed and expected growth in height, width, and weight to build or select a properly sized doghouse.

A doghouse that is too small can restrict animal movement and comfort, which may cause risk of cramping, a lack of airflow. A doghouse that is too large can fail to provide sufficient warmth. Consider the different ways to adjust a doghouse to suit the age, size, and growth of the dog(s).

For example, adding additional bedding while the dog is a puppy can help to reduce space, allowing the dog to better regulate its temperature in a structure that suits its current and future growth.

Bedding

Unless cleaned or replaced regularly, avoid the use of blankets, towels, or cushions as bedding within the doghouse as they can:

- attract pests

- grow mould

- freeze if they are damp or remain wet from rain or snow

Instead, consider using straw, wood shavings, wood pellets, moisture-proof foam or rubber pads as bedding. Wood shavings and pellets are known to repel fleas and ticks.

Providing additional bedding when temperatures drop below 0°C will better insulate the doghouse and can be easily removed in warmer temperatures.

If a dog is reluctant to use a doghouse, an owner should consider investigating to determine why (for example, there may be a smell causing the dog to avoid the shelter, or anxiety associated with using the shelter triggered by a specific stressor) and should take steps to address these issues.

3. Tethers

It is important to consider the material used to tether a dog, including the collar or harness used with a tether. Dogs that are tethered outdoors may experience irritation or injury if the tether and collar or harness used are not of a proper size, type, design, weight and fit. For example, a dog’s neck can become raw and sore, and collars may even penetrate its skin if the collar is too tight causing painful injuries. Certain collars are not appropriate for use with tethers because of the increased risk of injury.

To help ensure safe tethering, it is also important to take steps to:

- prevent entanglement of the tether

- ensure the dog has sufficient space and can move freely

- prevent the dog from escaping

- prevent the dog from reaching objects or hazards that may cause distress

It is inappropriate to tether a dog in certain stages of its life. For example, puppies under six months of age are unable to properly protect themselves and are at a higher risk of becoming entangled and tethering without appropriate social contact may interfere with critical socialization needs. Tethering a dog that is whelping or nursing may limit its ability to protect itself and its puppies and provide proper care. Tethering a dog that is in heat may pose increased risk of injury from a male dog who may try to forcibly mate with the female dog.

Legal requirements

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.3 (1) A tether that is used on a dog that is kept outdoors must,

- allow the dog to move about safely

- be of a size, type and weight that will not cause the dog discomfort or injury;

- have a swivel that can turn 360° at both

- the point where the tether is attached to the dog’s collar or harness

- the point at which the tether is attached to the fixed object

- be of sufficient length to permit the dog to move at least three metres measured in a horizontal direction from the point at which the tether is attached to the fixed object

- be of sufficient condition, and be sufficiently well-attached to the dog and to the fixed object, to prevent the dog from escaping

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.3 (2) A collar or harness used with a tether on a dog kept outdoors must be of a size, type, design and fit that will not cause the dog discomfort or injury

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.3 (3) A choke collar, pinch collar, prong collar, slip collar, head halter collar or martingale collar must not be used with a tether on a dog kept outdoors

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.3 (4) A dog kept outdoors must not be tethered in a manner that creates an undue risk of distress to the dog, including

- distress related to the age, health or reproductive status of the dog

- distress caused by objects or hazards that a dog is able to reach while tethered

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.3 (5) A dog kept outdoors must not be tethered if the dog is,

- under six months of age

- whelping

- nursing

- in heat

General guidance on tethering

Research suggests that tethering is not a universal solution for all dogs. An owner must evaluate whether their dog is compatible with a tether system to avoid negative outcomes and behavioural issues.

For example, tethering a dog for long periods in isolation can lead to insufficient socialization and result in the dog displaying fear-based aggression like biting.

If owners are looking for alternate ways to contain a dog that provides greater opportunity for exercise and socialization, they can consider the following methods that provide more space for natural behaviours like stretching or walking:

- keeping a dog within a large, fenced yard, large pen

- using a “running tether” method, such as a cable, pulley or trolley run

Best practices

Tether design

Ensure the tether is made of a durable material that will prevent the tether from cutting into the skin and becoming tangled around a dog’s legs and that is chew-proof to prevent a dog from escaping. For example, use a lightweight chain or coated cable instead of using a rope.

A tether should not weigh down a dog when it attempts to move. As a best practice, the tether should not weigh more than 10% of a dog’s body weight.

Collar or harness design

Dog collars constructed of nylon, polyester or leather material may be preferable for use with a tether as they are strong, flexible and non-toxic. The size and width:

- should fit properly around the neck of the do

- should not constrict its ability to breathe or perform natural behaviours,

- should not allow it to escape or pose a risk that the collar or harness may get caught on objects.

Using a harness instead of a collar for the purpose of attaching a dog to a tether can reduce the possibility of injury to the neck.

Collars and harnesses should be checked regularly for wear and tear, and to ensure they fit properly, particularly for younger dogs that are growing.

Preventing entanglement

There are risks associated with connecting a tether to an im-moveable object. Risks include an inability to escape predators and an increased risk of entanglement which can lead to choking or strangulation.

Owners are encouraged to check on tethered dogs frequently due to the risk of injury and strangulation that tethering may pose.

Tether length

Consider factors like the breed, size, energy level and social requirements of the dog when estimating the space and social opportunities that different tethering systems offer.

Preventing escape

To ensure safe conditions, tether dogs within a larger containment area (for example, a fenced area) in case of escape and to avoid entry or predation by another animal.

Preventing accidents and injuries from tethering

Consider what a dog can reach while on the tether, whether it be:

- objects, for example:

- sharp tools

- other animals

- toxic materials

- potentially dangerous environments that could pose a hazard, for example:

- tethering on a platform

- tethering on the edge of a deck

- tethering beside a fence that may allow the dog to jump over the fence and potentially strangle themselves or may result in the tether getting caught on the fence

Geriatric dogs kept outdoors are at a greater risk of mobility issues, injuries and anxiety as a result of vision and hearing loss or cognitive decline. Tethering a dog can exacerbate sensory issues and result in negative welfare consequences such as injury or excessive fear and anxiety.

Adapting dogs to tethering

Dogs should be trained to be tethered before being left alone on a tether, to help minimize the risk of distress. Training, which can begin once a puppy reaches six months of age or earlier if the owner is physically present to provide supervision, requires a gradual increase in the amount of time that the dog is left alone on the tether combined with careful monitoring for adverse effects.

3.1 Time off tether

Dogs tethered outdoors for long periods of time without an opportunity for exercise and enrichment can experience physical and psychological distress.

Dogs are social animals and require appropriate social contact with humans or other dogs, as well as the opportunity to perform natural behaviours such as running and playing to sustain positive welfare. Appropriate enrichment can also help to entertain a dog, encourage learning and prevent boredom and negative mental states.

Prolonged confinement on a tether can prevent a dog from getting adequate, daily exercise and enrichment. Insufficient exercise can trigger distress, injury, illness, malaise, anxiety and fear within a dog and affect its ability to socialize and interact with both humans and other dogs.

Consequences of inadequate exercise may include the dog becoming withdrawn or becoming hyperactive, exhibiting aggression and performing repetitive behaviours such as excessive pacing, barking, circling and digging.

Legal requirements:

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4 (1) A dog tethered outdoors for 23 hours in a 24-hour period, whether those 23 hours are consecutive or not, must be taken off the tether for at least 60 continuous minutes to allow for exercise and enrichment.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4 (2) The 60 continuous untethered minutes required by subsection (1) must be provided before the dog can be tethered outdoors again.

This requirement applies any time a dog is tethered outdoors for 23 hours in a 24-hour period, regardless of whether those 23 hours are consecutive, and regardless of whether the owner is physically present while the dog is being tethered.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4 (3) This requirement does not apply if

- The dog has, within the previous 24-hour period, participated in a racing event, hunting event, field trial event or comparable event and requires rest as a result of participating in the event.

- Extreme weather conditions identified by a weather warning or watch from Environment and Climate Change Canada, such as a heat warning, would make it unsafe for the dog to exercise or receive enrichment.

- A veterinarian advises, in writing, that the dog should not be taken off the tether for health reasons.

Guidance and best practices

Time off tether can consist of letting the dog into an activity pen (or a housing pen if it is large enough to enable exercise) where it can freely run. It can also consist of taking the dog for a walk using a leash (which is not a tether).

Be aware of a dog’s breed, age, level of fitness and physical condition as it may impact the amount of exercise they require. For example, higher-energy breeds may require more than 60 minutes of exercise or enrichment.

Enrichment

Types of enrichment for dogs fall into two broad categories:

- social enrichment through interactions with other dogs or people including play, petting and affection

- enrichment of the dog’s environment by exposing them to various outdoor and indoor settings, toys, training, food-based and sensory enrichments

The type of enrichment tools and length of exposure will vary greatly depending on the age, breed and temperament of the dog.

Examples of enrichment methods that help promote good animal welfare include:

- exposing dogs to different scents

- playing with safe toys or providing play structures

- food-based enrichments such as food dispensing toys

- providing opportunities to dig

- water-based enrichments such as sprinklers and buckets (floating toys, balls, or ice cube treats can be added to increase enrichment value)

4. Housing pens

The regulation defines a “housing pen” as an enclosed yard, caged area, kennel or other outdoor enclosed area in which a dog is contained and which is not large enough to provide sufficient space for the dog to run at its top speed. A housing pen may be used to house a dog, meaning where it may eat, rest, urinate and defecate. Owners may also wish to have a second pen used for the purpose of exercise and play (an “activity pen” or “exercise pen”).

When a dog is kept in a housing pen, it is important to make sure the dog:

- has sufficient space to move freely

- can’t escape

- is protected from predators,

- has a safe environment if multiple dogs are housed together in the same pen

A housing pen that is too small and does not allow a dog sufficient space to express natural behaviours can negatively impact its physical and psychological well-being. For example, the dog may develop negative behaviours towards humans or other dogs, such as fear-based aggression.

Additionally, when female dogs come into heat, a male dog (including both a neutered and non-neutered male dog) can become forceful in its attempts to reach the female dog and mate. This can be difficult to monitor and can lead to injury or, in the case of non-neutered males, unintended breeding.

Legal requirements

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (1) A dog that is kept outdoors must not be kept in a housing pen if doing so would create an undue risk of distress to the dog.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (2) A dog that is kept outdoors may only be kept in a housing pen if the housing pen is constructed so that it prevents the dog from escaping and provides reasonable protection from predatory animals or other animals that may harm the dog.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (3) The size of a housing pen for a dog that is kept outdoors must meet the following minimum requirements:

Minimum housing requirements Height of the dog - measured at its shoulder)cm Area of housing pen (m²) 70 or greater 15 >= 40 and <70 10 >= 20 and <40 6 less than 20 4 - O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (4) For the purposes of determining the required minimum size of a housing pen, a dog’s height shall be determined by measuring the height of the dog at its shoulder when it is standing at full height.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (5) If more than one dog is kept in a housing pen, the housing pen must provide at least the space required by the chart above for the tallest dog kept in the housing pen, plus a minimum of at least 1.5 additional square metres of space for every additional dog that is kept in the housing pen.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (6) 1.5 additional square metres of space is not required for every additional dog that is less than 12 weeks old and that is kept with its mother or substitute mother.

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (7) If more than one dog that is kept outdoors is kept in the same housing pen, the owner or custodian of the dogs must ensure that:

- dogs exhibiting aggression to other dogs are not placed with incompatible dogs

- a female dog that is in heat or coming into heat is not placed with a male dog

- O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.4 (8) A female dog that is in heat or coming into heat may be placed in a housing pen with a male dog solely for the time required for them to mate if the dogs are in the physical presence of the owner or custodian of one or more of the dogs and that person is monitoring the safety of the dogs.

Guidance and best practices

Preventing escape and protection from predators

Aim to ensure that the height of a housing pen is tall enough so that the dog is not able to easily jump over it to escape the pen.

If the environment surrounding the dog is known to have predatory animals (for example, wolves or coyotes), consider:

- bringing the dog indoors

- taking additional safety measures to protect the dog, including using electronic fences, covered pens, or motion detectors that can trigger lights or sound devices that release harmless ultrasonic frequencies that can act as a deterrent to predators

Minimum size of a housing pen

Note that a doghouse can be placed inside the housing pen. This does not impact the minimum housing pen size requirements.

Group housing in a pen

There are benefits to group housing multiple dogs together in a pen. These include positive interactions, such as:

- play

- companionship

- physical connection

- increased socialization and enrichment

When using a pen to house several dogs together, use a consistent approach of leaving all dogs within the pen either tethered or untethered. There are risks associated with tethering some dogs in the same pen while leaving other dogs free to roam, such as aggression, anxiety or fighting resulting in potential injury.

If group housing is carried out improperly (for example, if dogs that have shown aggression towards each other are group housed together, or if a dog with a contagious disease is group housed with healthy dogs), risks can include:

- increased infectious disease exposure

- fear

- anxiety

- injury

- death

Consider using separate food and water bowls for each dog if necessary to prevent competition and minimize resource-based conflict and aggression while group housing.

Female dogs in heat and pen housing

If possible, keep any isolation pen where a female dog in heat is housed close to other familiar dogs to promote continued social contact while protecting the female dog.

If other familiar dogs are housed closely to the female dog in heat, close monitoring of the male dogs is recommended to ensure they are not reacting aggressively and potentially causing injury to each other. A barrier or walkway that runs between the female dog in heat and male dogs is recommended to prevent unintended breeding that can occur through permeable fences.

Consult with a licensed veterinarian as soon as possible if unintended breeding is suspected or is found to have occurred.

5. Tether and housing pen area

It is important to ensure the containment area, whether a dog is on a tether or in a housing pen, provides sufficient and separate spaces for the dog to eat, drink, access a dog shelter, urinate and defecate. It is also important to maintain a clean, sanitary environment with appropriate drainage to ensure a dog is not living in contaminants or at risk of becoming injured or ill.

Legal requirements:

O. Reg. 444/19, s. 4.5 The area available to a dog kept outdoors that is placed on a tether or in a housing pen must:

- be sufficient to ensure that the dog can move freely and engage in natural behaviours

- be sufficient to ensure that the dog is not required to stand, sit or lie down in excrement, urine, mud or water

- have distinct areas for both

- feeding and drinking

- urinating and defecating

- be cleaned as frequently as necessary to prevent an accumulation of excrement, urine or other waste that would pose a risk to the dog’s health, maintain a sanitary environment, minimize the presence of parasites and ensure the health of the dog, using cleaning products that do not pose a risk to the dog

Guidance and best practices

When designing the containment area, consider several factors, including the dog’s:

- breed

- size

- behavioural habits (for example, digging, chewing, resting)

The dog’s size and personality can inform how to best to design a containment area, including what types of materials to use (for example, durable rubber, which is easy to clean and sanitize, or straw bedding which is easy to replace).

Avoid risk of infection, injury, and irritation by installing appropriate drainage where a dog is contained, to help ensure they do not live in wet, muddy or damp conditions. In many instances, build-up of moisture and bacteria can result in paw injuries to dogs, including splits or fissures.

Removing waste

Removing waste products helps to protect the owner as well as the dog.

Waste products may include:

- dog feces

- urine

- soiled litter

- soiled bedding

- vomit

- food waste

It may be more difficult to remove certain waste products depending on the location of the containment area (for example, cleaning urine from grass).

Allowing a build-up of urine or feces to accumulate can be unsanitary, host bacteria, and transmit viruses and internal parasites that may be harmful to both owners and their dogs.

Cleaning schedule

Consider removing waste products daily, or more frequently based on the number of dogs kept in one housing pen.

Maintaining a proper cleaning schedule for a dog’s containment area:

- reduces the likelihood of odours and high ammonia levels

- allows the dog to maximize use of the enclosure space for natural behaviours, such as rest or play

Cleaning frequency may need to increase with multiple dogs housed in one pen.

A neglected pen can create unsanitary and unhealthy conditions. For example, if dogs play and eat in an area that has accumulated feces, they can accidentally consume feces resulting in parasites and infections.

Waste products should be collected and disposed of promptly in a hygienic manner.

Cleaning products

Cleaning products should be non-toxic and environmentally friendly, so they do not cause illness or injury to the dog. Use products that contain natural compounds like:

- diluted vinegar

- hydrogen peroxide

- baking soda

- soda water and similar products

Avoid using cleaners that contain ammonia or bleach.

Disclaimer

The Ministry of the Solicitor General recognizes animal welfare is a complex topic, and that research on animal welfare and care practices continues to evolve. This information is current as of July 2022. The ministry may provide updates to this document in the future.

This guidance document has no legal effect. It does not create legal rights, obligations, immunities or privileges. This guidance document is not legal advice. This guidance document should be read together with the Provincial Animal Welfare Services Act, 2019 (PAWS Act) and Ontario Regulation 444/19: Standards of Care and Administrative Requirements. If there is any conflict between this guidance document, the PAWS Act or the regulation, the PAWS Act and the regulation prevail.

Glossary of terms

Activity pen: Also known as an exercise pen, a fenced (including invisible or electric fence) or otherwise enclosed area that is large enough for a dog to run at its top speed and is used for exercise, play or enrichment.

Aggression: Antagonistic behaviours exhibited by a dog toward other dogs or humans (for example, mounting, resource guarding, barking).

Animal Welfare Services: Animal Welfare Services is responsible for enforcing the Provincial Animal Welfare Services Act, 2019. Provincial inspectors respond to concerns and carry out inspections and investigations. They also conduct outreach and education on animal care best practices.

Body condition: Body condition refers to a dog’s relative proportions of muscle and fat across its body that affect its day-to-day activities and health. Body condition is generally measured through a Body Condition Score, which is a tool that assigns a score based on a visual, hands-on assessment of the dog’s levels of lean muscle and fat.

Chief Animal Welfare Inspector: Appointed by the Solicitor General of Ontario, the Chief Animal Welfare Inspector is responsible for appointing animal welfare inspectors and overseeing Animal Welfare Services.

Choke collar: A restraint device that tightens around a dog’s neck without limitation.

Contagious disease: A disease that spreads from animal to animal, person to animal or person to person (also known as an infectious, communicable, or transmissible disease).

Contamination: The unwanted presence of a material that is potentially harmful. For example, the presence of dirt, urine, feces, or toxic substances.

Disinfect: Using a substance to kill microorganisms (such as bacteria) left on a surface after cleaning the surface.

Distress: Defined under subsection 1(1) of the Provincial Animal Welfare Services Act, 2019 as the state of being a) in need of proper care, water, food or shelter, b) injured, sick, in pain or suffering, or c) abused or subject to undue physical or psychological hardship, privation or neglect.

Doghouse: A structure that offers shelter and protection against the elements (for example, sun, rain, wind, snow).

Geriatric dog: An older dog experiencing gradual decline in its body’s ability to repair itself, maintain normal body functions, and adapt to stresses and changes in its environment. The “geriatric stage” can vary depending on dog size, breed, and quality of life.

Head halter collar: A collar that has one loop that slips over the dog’s snout and another loop that clips around the back of its neck. The throat-clip style then has a ring situated at the throat that attaches to the leash.

Housing pen: An enclosed yard, caged area, kennel, or other outdoor enclosed area in which a dog is contained, and which is not large enough to provide sufficient space for the dog to run at its top speed.

In heat: Also known as “estrus”, the stage at which a female dog is physically capable of and receptive to mating and can become pregnant.

Kennel: An outdoor enclosed area used to contain a dog. For the purposes of this document, a kennel does not refer to a facility in which dogs are bred, trained, or boarded.

Livestock: For the purposes of this document, livestock means sheep, pigs, goats, cattle, horses, mules, ponies, donkeys or poultry.

Livestock guardian dog: A dog that is identifiably of a breed that is generally recognized as suitable for the purposes of protection of livestock from predation and lives with a flock or herd of livestock.

Martingale collar: A collar made with two loops. The larger loop is slipped onto the dog’s neck and a lead is then clipped to the smaller loop. When the dog tries to pull, the tension on the lead pulls the small loop taut, which makes the large loop smaller and tighter on the neck.

Natural behaviours: Behaviour is the action, reaction or functioning of an animal in various circumstances. Natural behaviours are behaviours that animals tend to exhibit under natural conditions, because these behaviors are pleasurable and promote biological functioning (for example, stretching, barking, socializing).

Pinch or prong collar: A collar with a series of blunted points that pinch the skin of a dog’s neck when pulled. When the control loop is pulled, the prongs pinch the loose skin of the dog’s neck.

Racing and hunting/field trial events: Events designed to focus on racing (for example, sled dog racing) or hunting abilities in dogs.

Standard of care: A minimum requirement for the care of an animal. All owners and custodians must comply with the standards of care and administrative requirements set out under the Provincial Animal Welfare Services Act, 2019 as they apply.

Tether: A rope, chain or similar restraining device that is attached at one end to a fixed object and, for greater certainty, does not include a leash or restraining device that is held by a person.

Ticks: Small parasites that can carry viruses and/or bacteria that are harmful to both dogs and humans. Ticks have mouthparts that attach to skin. During this period of attachment, they can transfer harmful viruses and/or bacteria into the dog’s bloodstream and cause disease.

Veterinarian: A person licensed as a veterinarian by the College of Veterinarians of Ontario.

Whelping: The act of birthing puppies.

Appendices

Appendix A: The Five Domains Model

Reference of chart: The Five Domains Model

Appendix B

Reference of chart: Underdog Pet Foods | AAFCO Fresh Dog Food Singapore

References

American Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). Cold weather animal safety. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/pet-owners/petcare/cold-weather-animal-safety

American Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). Disease risks for dogs in social settings. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/pet-owners/petcare/disease-risks- dogs-social-settings

American Kennel Club. (n.d.). Kennel emergency and disaster planning for breeders: Keeping your dogs and facility safe. Retrieved May 2022 from https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/dog-breeding/kennel-emergency-disaster-planning-keeping-dogs-facility-safe/

Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. (2018). A Code of Practice for Canadian Kennel Operations (3rd Edition). Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.canadianveterinarians.net/media/xgel- 3jhp/code-of-practice-for-canadian-kennel-operations.pdf

Canadian Veterinary Medical Association. (2014). Eco-friendly Pet Care Tips. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.canadianveterinarians.net/related-resources/eco-friendly-pet-care-tips/

Carter, A., McNally, D., & Roshier, A. (2020). Canine collars: an investigation of collar type and the forces applied to a simulated neck model. Veterinary Record, 187(7), e52-e52.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Healthy Pets, Healthy People: Dogs. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.cdc.gov/healthypets/pets/dogs.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Proper hygiene when around animals. Retrieved May 2022 from https://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/hygiene/etiquette/around_ani- mals.html

Chapagain, D., Virányi, Z., Wallis, L.J., Huber, L., Serra, J., & Range, F. (2017). Aging of attentiveness in border collies and other pet dog breeds: The protective benefits of lifelong training. Frontiers in aging neuroscience, 9, 100.

Dev, R. (2016). The Ekistics of Animal and Human Conflict. Copal Publishing Group.

Freeman, L.M. (2020). The scoop on storing pet food. Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved April 2022 from https://vetnutrition.tufts.edu/2020/10/the-scoop-on-storing-pet- food/

Gershman, K.A., Sacks, J.J, & Wright, J.C. (1994). Which dogs bite? A case-control study of risk factors. Pediatrics, 93(6), 913-917.

Ghasemzadeh, I. & Namazi, S. H. (2015). Review of bacterial and viral zoonotic infections transmitted by dogs. Journal of Medicine and Life, 8(Spec Iss 4), 1-5.

Government of British Columbia, Ministry of Agriculture. (2012). Sled Dog Code of Practice. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resourc-

es-and-industry/agriculture-and-seafood/animal-and-crops/animal-welfare/sled_dog_code_ of_practice.pdf#:~:text=The%20Sled%20Dog%20Code%20of%20Practice%20is%20a,in%20 the%20Sled%20Dog%20Standard%20of%20Care%20Regulation

Hastings Veterinary Hospital. (2018). Signs of hypothermia in dogs and what to do about it. Retrieved April 2022 from https://hastingsvet.com/signs-hypothermia-dogs/

Houpt, K.A. (2018). Domestic Animal Behavior for Veterinarians and Animal Scientists (6th edition). John Wiley & Sons.

Mellor, D.J. (2016). Moving beyond the “Five Freedoms” by updating the “Five Provisions” and introducing aligned “Animal Welfare Aims”. Animals, 6(10), 59. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5082305/

Mellor, D.J., Beausoleil, N.J., Littlewood, K.E., McLean, A.N., McGreevy, P.D., Jones, B., & Wilkins, C. (2020). The 2020 five domains model: Including human–animal interactions in assessments of animal welfare. Animals, 10(10), 1-24. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/10/10/1870

Milgram, N.W., Head, E., Zicker, S.C., Ikeda-Douglas, C.J., Murphey, H., Muggenburg, B., Siwak, C., Tapp, D., & Cotman, C.W. (2005). Learning ability in aged beagle dogs is preserved by behavioral enrichment and dietary fortification: A two-year longitudinal study. Neurobiology of aging, 26(1), 77-90.

Moesta, A., McCune, S., Deacon, L., & Kruger, K.A. (2015). Animal Behaviour for Shelter Veterinarians and Staff, Chapter 8: Canine Enrichment.

Mood, A. (2019). How to tell if your dog is stressed. American Kennel Club. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/advice/how-to-tell-if-your-dog-is-stressed/

Morris, Amy. (2013). Policies to promote socialization and welfare in dog breeding. Retrieved April 2022 from https://spca.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/Morris-A-2008-policies-to-Promote-Social- ization-and-Welfare-in-dog-breeding .pdf

Mush with PRIDE. (2021). Sled Dog Care Guidelines 4th Edition. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.mushwithpride.org/downloads

Ontario SPCA. (n.d.). Ideal doghouse for outdoor use in Ontario. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.oshawa.ca/residents/resources/Ideal_Doghouse_Accessible.pdf

Ontario SPCA and Humane Society. (2020). Cold weather pet safety tips. Retrieved April 2022 from https://ontariospca.ca/blog/cold-weather-pet-safety-tips/

Ontario SPCA and Humane Society. (n.d.). Group housing. Retrieved April 2022 from https://ontariospca.ca/spca-professional/shelter-health-pro/environmental-needs-and-be- havioural-health/facility-assessment/housing/dog/group-housing/

Ontario SPCA and Humane Society. (2020). Hot weather pet safety. Retrieved April 2022 from https://ontariospca.ca/blog/hot-weather-pet-safety/#:~:text=It’s%20important%20to%20 watch%20for,cool%20water%2C%20not%20cold%20water

Ontario SPCA and Humane Society. (n.d.). Shelter house pro: Enrichment and socialization for dogs and puppies. Retrieved April 2022 from https://ontariospca.ca/spca-professional/shelter-health- pro/environmental-needs-and-behavioural-health/enrichment-and-socialization-dog/

Ontario Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). Pet Health 101. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.ovma.org/pet-owners/basic-pet-care/pet-health-101/

Ontario Veterinary Medical Association. (n.d.). Pet safety tips. Retrieved April 2022 from https:// www.ovma.org/pet-owners/basic-pet-care/pet-safety-tips/

Reisen, J. (2021). Warning signs of dehydration in dogs. American Kennel Club. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.akc.org/expert-advice/health/warning-signs-dehydration-dogs/

Romaniuk, A., Flint, H., & Croney, C. (2020). Does long-term tethering of dogs negatively impact their well-being? Purdue College of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/VA/VA-23-W.pdf

Shortsleeve, C. (2020). 7 mistakes to avoid when storing dog food. Great Pet Care. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.greatpetcare.com/dog-nutrition/7-mistakes-to-avoid-when-storing- dog-food/

Stewart, M. J., Barker, P., Boissonneault, M.-F., Clarke, N., Kirby, D., Kislock, L., Long, R., Morgan, C., Moriarty, M., Tedford, T., Turner, F., & Wepruk, J., Sled Dog Code of Practice 7–41 (2012). Victoria, B.C; Ministry of Agriculture.

The Humane Society of the United States. (n.d.). Chewing: How to stop your dog’s biting problem. Retrieved May 2022 from https://www.humanesociety.org/resources/stop-your-dogs-chewing

Weir, M. & Buzhardt, L. (n.d.). Signs your dog is stressed and how to relieve it. VCA Animal Hospitals. Retrieved April 2022 from https://vcacanada.com/know-your-pet/signs-your-dog-is- stressed-and-how-to-relieve-it

Wells, D. L. (2009). Sensory stimulation as environmental enrichment for captive animals: a review. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 118(1-2), 1-11.

Williams, K. & Buzhardt, L. (n.d.). Body Condition Scores. VCA Animal Hospitals. Retrieved April 2022 from https://vcacanada.com/know-your-pet/body-condition-scores.