This page was published under a previous government and is available for archival and research purposes.

Chapter 3: Improving infrastructure delivery

Ontario is a global leader in infrastructure financing and delivery. A cornerstone of good government is the strong, effective long-term management and stewardship of provincial assets. This includes responsible fiscal planning for infrastructure projects.

The Government of Ontario is committed to investing about $190 billion over 13 years, starting in 2014–15, but this will not satisfy all of Ontario’s infrastructure needs. There is a gap between the number of investments that local, provincial and federal governments can make and the number of projects that are requested. This challenge needs to be tackled by all orders of government working together.

Saving money by managing demand

In considering how best to pay for infrastructure investments, one thing the government can explore is how to manage demand for infrastructure in the first place. Demand management is one strategy among others that can help to meet Ontario’s infrastructure needs. Demand management strategies, such as user fees, will have an impact on demand, which will change the government’s future infrastructure needs. These strategies can also help offset the cost of infrastructure investments. For this reason, infrastructure needs and infrastructure funding sources should be considered simultaneously, rather than independently.

A number of examples of demand management tools are explored in the following table:

Cost savings from managing demand

According to a study by the Conference Board of Canada, there is a strong relationship between municipal water consumption and pricing. Municipalities, in Ontario and elsewhere that use metered pricing see lower levels of water consumption on a per-capita basis than those that do not.

By managing demand for water per capita, infrastructure needs, particularly the need for more and larger water-treatment plants, decrease. Through a conservative calculation, the Conference Board’s report estimates that Canada could reduce its municipal water infrastructure gap by $4 billion by revisiting water pricing policies and approaching per-capita municipal water-usage rates seen in peer countries, such as the UK.

Cost savings from shifting demand

The implementation of user pricing can also affect infrastructure needs by shifting, as opposed to reducing, demand. For example, electricity prices that vary by time of day, as they do in Ontario, can shift demand to off-peak periods.

Paying for infrastructure

After identifying cost savings through demand management tools, there may still be a gap between the funding available and the funding needed. In this case, the government will need to identify other funding sources to fill this gap.

Typically, all major infrastructure projects require both financing and funding.

Financing is the source of money to pay up front for the construction of an infrastructure project. Usually, this involves borrowing “tools,” such as government bonds, that are used to bridge the time gap between the building of infrastructure and when infrastructure funding becomes available.

Funding is the source of money that will be used to pay for building and maintaining infrastructure.

To illustrate the difference between funding and financing, using a household analogy, consider a typical home purchase. When purchasing a new home, a household will usually borrow money from a bank through a mortgage to finance a portion of the home purchase. In this case, the mortgage is the source of financing. The mortgage is then repaid over time through income generated by the household. The household’s income is the source of funding.

There are a number of potential sources of funding, some of which are discussed in more detail below and some that are already in use in Ontario:

Financing tools

- Debt Financing (general borrowing)

- Alternative Financing & Procurement (AFP or Public-Private Partnerships / P3s)

- Direct Institutional / Private Investment (e.g., from Pension Funds)

- Tax-Increment Financing

- Social Finance (Social / Green bonds)

- Infrastructure Banks

- Infrastructure Ontario Loan Program

Funding tools

- Taxes (income, property, sales, gas)

- Special Taxes & Levies (e.g., congestion charges)

- User Fees (e.g., transit fares, recreation activity fees, road tolls, licensing fees, facility rental rates)

- Concession Arrangements

- Asset Recycling

- Joint Development

- Land Value Capture

Funding infrastructure: Unlocking the value of government assets

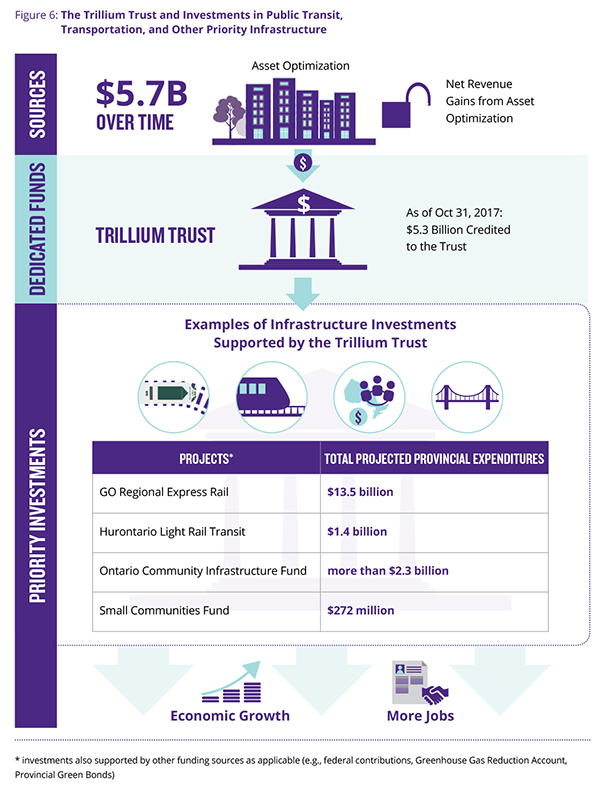

Dedicated revenues can help to ensure a transparent source of infrastructure funding. In addition to the traditional method of funding public infrastructure through the tax base, the government’s asset-optimization strategy is repurposing the value of certain non-core public assets, and dedicating net revenue gains to the Province’s Trillium Trust to help support investments in transit, transportation and other priority infrastructure assets.

Net revenue gains from the sale of qualifying provincial assets are credited to the Trillium Trust, created under the Trillium Trust Act, 2014. Ontario has set a target of dedicating $5.7 billion to the Trillium Trust and is on track to meet its target. This includes net revenue gains from broadening Hydro One ownership, and other sales of qualifying assets, such as the LCBO head office lands.

The government will be allocating up to $400 million this year from the Trillium Trust to support investments in public transit, transportation and other priority infrastructure projects, based on planned expenditures in the 2017 Budget. This builds on last year’s allocation of $262 million to support key investments across the province, such as GO Regional Express Rail, Hurontario Light Rail Transit, the Ontario Community Infrastructure Fund and the Small Communities Fund.

Funding infrastructure: Land value capture

The Province is continuing to look for innovative methods to pay for infrastructure, beyond traditional taxes and user fees. One method is land value capture (LVC).

LVC is a method of funding infrastructure improvements by recovering all or some of the increase in property value generated by public infrastructure investment. This can include partially financing infrastructure by selling development rights near an infrastructure project, such as the “air rights” above a transit station.

Understanding the best practices for LVC implementation is key to putting conditions in place for LVC to succeed. It’s important to keep in mind that, even when used in the most optimal situations, LVC generates only a maximum of 20 to 30 per cent of the funds necessary for new infrastructure.

Funding infrastructure: Other tools

There are other tools for funding infrastructure. For example, Ontario provides support for municipal transit systems through a portion of the provincial gas tax. Two cents per litre of the gas tax is distributed to municipal transit systems, helping them improve and expand services, including, for example, increasing hours of service, expanding routes and upgrading transit infrastructure. Ontario will increase funding to municipal transit systems across the province through an enhancement to the existing gas-tax program, doubling the municipal share from two cents per litre to four cents by 2021. There will be no increase in the tax that people in Ontario pay on gasoline as a result of the enhancement to the program.

User fees are a common tool to raise funding for infrastructure investment and for influencing demand. Common examples of user fees are transit fares, recreation activity fees, road tolls and licensing fees. For example, municipal transit systems are supported by transit fares. Other jurisdictions use a range of user fees and revenue tools. One user-fee challenge to consider in infrastructure planning is that the public is often not willing to pay for things they have used for free for decades, unless there is an alternative in place.

Other tools include special taxes and levies, such as congestion charges.

Procuring infrastructure: Traditional procurement and project delivery

Ontario has a robust infrastructure procurement system that delivers value for Ontarians. Infrastructure projects can be delivered in a number of ways, including directly by the government. In delivering infrastructure projects, the owners of assets, such as ministries or agencies, manage and deliver the projects themselves, through the traditional public-sector competitive procurement process: formally setting out the government’s requirements in a design and inviting vendors to respond with how they would meet the design requirements and how much it would cost; then selecting the successful bidder, entering a contract, and paying on a regular basis as the work proceeds. When the government is delivering and managing a project itself, the Province assumes most of the risks throughout the construction of the asset. The Province also assumes responsibility for operating and maintaining the asset when it is complete.

This approach can work well in many circumstances, such as when a ministry has significant experience in delivering major infrastructure investments, and on smaller, less-complex infrastructure projects. However, in traditional procurement for large, complex infrastructure projects, the government assumes significant risk. This is because it has limited leverage to ensure that on-time and on-budget delivery and specifications are met. Also, bidders have limited opportunities to suggest cost-saving innovations by looking at the project over its whole life cycle.

The Province continues to use the traditional procurement approach for many of its infrastructure projects. However, for the government’s very large and complex projects, it has developed another approach: Alternative Financing and Procurement (AFP).

Procuring infrastructure: Alternative Financing and Procurement

A key infrastructure delivery tool is the Province’s made-in-Ontario AFP approach.

The traditional model often requires companies to perform work for a stipulated sum. Contractors get paid as they go, and thus there may be less incentive for them to finish the job in a timely fashion. This can cause problems in jurisdictions that use the approach — not only in Ontario, but in countries around the world.

A major difference between the AFP delivery model and the traditional procurement model is that builders are required to finance the construction phase, and sometimes the maintenance phase, of projects with their own means of financing. The government provides no compensation until the project has been independently verified to have reached substantial completion or a key milestone. Under the AFP model, a single entity is accountable for multiple aspects of the overall project. Being responsible for both design and construction encourages builders to create smart and innovative designs that reduce challenges in implementing the design during the construction phase. The AFP model also promotes an increased sense of project ownership on the part of the contractor.

All public infrastructure projects, including AFPs and traditional projects, have five key governing principles: transparency, accountability, value for money, public ownership and control and protection of the public interest. The Province will also ensure that procurement is carried out in an open, non-discriminatory way, to respect Ontario’s trade obligations.

Unlike the traditional infrastructure-procurement process, in which the Province assumes most of the risks associated with delivering a project, the AFP delivery model transfers some of the risk inherent to the project to the party best able to manage and mitigate that risk. An example of risks that are transferred to the private sector could include increased construction costs and/or schedule delays as the project develops. Ontario has been successfully implementing the AFP delivery model for over a decade.

AFP involves a competitive process to select a private-sector proponent, which is generally an integrated group of companies. The proponent designs and builds the asset, finances it, often maintains it and sometimes operates it. Combining more aspects — such as design, maintenance and operations — into the bidding requirements gives proponents more opportunities to innovate and find savings. The Province, or public entities, always retain ownership of the asset.

The Province pays for performance when the proponent achieves certain milestones and meets pre-set quality and performance standards. The delay in compensation provides the necessary incentive for the proponent to complete the project on time, on budget and to specifications. The Province or a government body signs a contract with the selected vendor to undertake the project.

As part of developing an infrastructure project, the appropriate delivery model must be identified. Delivery-options analysis considers numerous factors, such as technical complexity; the potential to integrate design, construction and/or maintenance; and the potential to transfer risk to the private sector. If it has been determined that there is potential for the project to be delivered as an AFP, the project goes through a quantitative value-for-money (VFM) analysis to help determine the preferred procurement model. VFM is a comparison between the risk-adjusted costs for the entirety of the project. If the risk-adjusted costs for the AFP approach are lower than the risk-adjusted costs for the traditional approach, there is positive value for money. Positive value for money is an important principle for determining whether to deliver projects using the AFP delivery model. As of March 2017, the 74 AFPs that have reached financial close are expected to produce a net benefit to government of over $9.5 billion.

AFP: The potential to achieve more

The Province is continuing to look for ways to strengthen the successful AFP delivery model. The government has added new considerations to the infrastructure-procurement process, such as the evaluation of a proponent’s knowledge of local circumstances, the specification of health and safety requirements and the employment of apprentices. Infrastructure Ontario has also recently launched a Vendor Performance Program to ensure high-performing vendors are selected for AFP projects. The program is currently being phased in. Other potential approaches being considered to increase the effectiveness of AFP are described below.

Improved AFP evaluation and analysis

To ensure that the AFP model continues to provide value, the government has developed an evaluation framework to track the success of this delivery model. This framework aims to assess the AFP delivery model’s ability to (a) deliver projects on-budget, on-time and on-specification, (b) ensure proper risk transfer to the private sector was achieved at final completion, and (c) ensure timely procurement. The government will start by evaluating a selection of completed AFPs and traditionally delivered projects of a similar size to assess the performance of each model against these criteria. Ultimately, over time, this framework will provide a stronger evidence base for the AFP delivery model, which will help decision-makers choose the right delivery model for future projects.

Complementing the performance assessment, the government is also refining its delivery-options analysis process. An improved delivery-options analysis process will ensure the government has the evidence it needs to recommend to decision-makers which delivery model to use on each project. It will help ensure that the recommended delivery model matches the characteristics of the major public infrastructure project and is the best for designing, building, operating and maintaining that particular project.

These assessments will support the government in addressing recommendations from the 2014 Auditor General’s Report — including measuring risk transfer to the private sector and having a stronger evidence basis for the AFP delivery model.

Maintenance

Maintenance is a necessary cost that has to be incorporated into total project cost. It is important to ensure that Ontario’s assets continue to operate for years to come, and to have a plan to fund proper maintenance of infrastructure.

The Province currently has two primary approaches to ensuring good maintenance:

- For most projects, the Province contracts with the private sector to undertake regular maintenance on an existing asset. Separate private-sector entities provide life-cycle maintenance, such as boiler refurbishment, when required.

- For some AFP projects, the same private-sector entity that constructs the asset also offers regular and life-cycle maintenance, so the Province can ensure that the maintenance of newly constructed infrastructure assets meets specific standards throughout the life of the asset.

Infrastructure Ontario helps asset owners, sponsoring ministries and private-sector companies with the transition of newly completed AFP projects into their 30-year operations and maintenance phase. Regarding the government’s general real-estate portfolio — essentially the portfolio of government buildings, such as courts, correctional facilities and office buildings — Infrastructure Ontario provides contract management and administrative and advisory services. Asset owners (e.g., ministries, agencies) can also ask Infrastructure Ontario to provide these services on AFP projects.

The Province is studying different approaches for infrastructure maintenance, including how to better help asset owners meet proper maintenance standards.

Municipal AFPs

With the success of the AFP program regarding provincially owned infrastructure assets, municipalities have expressed interest in using the AFP model. The AFP delivery model could provide benefits, such as discipline and transparency, to municipalities’ infrastructure-procurement processes and construction-contract-management practices. But there are considerations in adapting the AFP model for use by a municipality. They include:

- the scope, size and complexity of most municipal projects

- the municipality’s access to capital

- legislative restrictions (e.g., restrictions on borrowing)

- challenges in adopting new procurement methods

Infrastructure Ontario has provided advice and counsel to a few municipalities on delivering AFP projects, particularly in the transit sector. The Government of Ontario is committed to supporting municipalities to successfully deliver key infrastructure projects. For example, it is exploring how it can encourage and support municipalities in leveraging the AFP delivery model more frequently to achieve their infrastructure priorities, and what support and advice Infrastructure Ontario can potentially provide to municipalities.

Bundling

The AFP program has served the province well since being introduced. At the same time, the Province is continuing to look at innovative methods to address existing challenges and to allow for more private-sector involvement. For example, AFPs are more appropriate for large projects, meaning smaller projects may not quality for an AFP model.

Instead of considering small projects individually, bundling similar small projects by either sector or geographic region could help open opportunities for financing through the AFP model and attract more private investment. However, seeking a balanced approach will be key to ensuring that, while there may be an increase in scale and cost when bundling projects, smaller contractors can still participate.

Bundling is different from an Integrated Systems Approach, where different types of infrastructure assets are procured together and managed under a single AFP contract. Projects that may have the potential to be bundled include bridges, roads and other facilities. For example, a recent study conducted in the County of Wellington by the Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario (RCCAO) and Ontario Good Roads Association (OGRA), with MMM Group Limited, found that there was potential for municipalities to bundle bridge projects through an AFP model. The study recommended that the Province champion a demonstration of a bundled AFP project with a willing municipality to rehabilitate bridges.

Ensuring inclusive growth and accessibility

Ontario envisions its economic growth as inclusive growth that will deliver real benefits to everyone, whether that is in employment, education or health. Ontario strives to ensure that all Ontarians have the opportunity to contribute to and benefit from the economy through meaningful participation. Women, Indigenous People, immigrants, people with disabilities and from marginalized neighbourhoods are often people who are not sharing in the dividends of economic growth, and they often become further marginalized by economic activities that make land and public resources scarcer.

The government is taking steps to reform Ontario’s labour legislation to support the province’s most vulnerable workers by increasing the minimum hourly wage from $11.60 in 2017 to $15 in 2019. The change also emphasizes increased vacation entitlements and expanded personal emergency leave.

It is important that all people have the skills and resources to participate in inclusive growth, and infrastructure is a key tool that can be used to achieve that goal. Ontario is also working with its Indigenous partners to support training and employment in these communities. For example, the government is providing more support for Aboriginal Institutes to help expand their capacity as a distinct and complementary pillar of Ontario’s postsecondary education system.

The benefits of infrastructure investment do not stop at employment and economic activity. Infrastructure also supports inclusive growth and can improve Ontarians’ quality of life by providing:

- accessible spaces, where all Ontarians can realize their potential, receive needed services, contribute to their communities and enjoy rewarding cultural, recreational and outdoor activities

- better places to learn, teach and carry out research

- more comfortable and seamless experiences for those receiving health and community services

The government will ensure these opportunities are available in all regions of the province, fostering an environment of inclusive growth, in which everyone will benefit from, and contribute to, Ontario’s prosperity.

Supporting community benefits

The government wants to ensure that communities benefit from new infrastructure projects during development. The Government of Ontario is the first Canadian jurisdiction to pass legislation (IJPA) to enable consideration of community benefits in infrastructure planning and investment.

Community benefits are be defined in the IJPA as the “supplementary social and economic benefits” arising from an infrastructure project, such as local job creation and training opportunities, improvement of public space or other benefits the community identifies. This concept can help advance a range of goals, including reducing poverty and developing the local economy with input from under-represented groups.

Three kinds of initiatives can benefit communities:

- Workforce Development Initiatives provide employment and training opportunities (including apprenticeships) to members of traditionally disadvantaged communities, under-represented workers and local residents. This work complements the government’s broader workforce development initiatives.

- Social Procurement Initiatives include the purchase of goods and services from local businesses or social enterprises (organizations that use business processes to achieve social or environmental impacts).

- Supplementary Benefit Initiatives make a neighbourhood a better place to live, work and play — these are benefits that a community affected by a major infrastructure project asks for. It could be the creation of more physical public assets (e.g., child care facilities, a park) and/or getting more or better use from existing public assets (e.g., design features to reduce noise pollution or traffic congestion during and after construction).

Community benefits are one way for the government to pursue multiple policy goals, including poverty reduction, employment and training, especially for under-represented groups and support of small business. Ontario is a leader across Canada in successfully implementing community benefits on many types of projects through a variety of initiatives.

In the 2017 Budget, the Government of Ontario committed to consulting on the creation of a Community Benefits Framework.This consultation will continue to be guided by the principle that public-sector infrastructure procurement can create lasting community benefits that go far beyond the completion of a new building or asset. The Province is particularly interested in laying strong, evidence-based groundwork to decide on the best approach to achieve community benefits in Ontario. The identification and implementation of several community-benefits pilot projects will be the first step.

The experiences of Ontario and other jurisidictions have demonstrated that there are many different ways to incorporate community benefits into infrastructure projects. Specific design features can be incorporated into infrastructure-procurement processes for the private sector to deliver as part of the contract. Broader goals or desired outcomes can be included in a procurement, so that the proponents can propose an innovative solution or approach to achieve that desired outcome. Community benefits can be negotiated after a contract is signed, as part of the detailed design and construction preparation work. The role of the community, asset owner and private-sector partner can also vary. It will be important to select the right combination of pilot projects to ensure that Ontario can test a number of different ways to leverage infrastructure investments to achieve community benefits.

To that end, Ontario will continue to work with stakeholders, including the construction sector, social services, and community groups, to inform the selection of pilot projects by early 2018. Ontario will select a number of Community Benefits Pilot Projects that collectively cover a range of options across five important considerations:

- Pilot projects should include the full range of community-benefits initiatives.

- Pilot projects should be early enough in the development stage to allow for the option of including specific community-benefits requirements in requests for proposals (RFPs).

- Both AFP and traditional-delivery-model projects should be part of the pilot phase.

- Pilot projects should be restricted to provincially owned assets and be delivered by ministries that have pre-established relations with a target community.

- Pilot projects should be in different regions of the province and in a mix of urban and rural locations.

Over the course of 2018, the government will develop these pilot projects, so that lessons learned can be documented and the right approach for Ontario identified. There will continue to be ongoing dialogue and discussions with communities and the construction sector throughout the development and implementation of these pilot projects.

As the Community Benefits Pilot Projects progress, the government will begin work on the Community Benefits Framework by:

- gathering lessons learned from the variety of pilot projects, including the Metrolinx Community Benefit program for the Eglinton Crosstown LRT

- looking at what other jurisdictions are doing, and developing made-in-Ontario approaches

- finding innovative ways to achieve broader benefits to local communities

- monitoring infrastructure projects with a view to their achieving community benefits

Following the launch and initial implementation of the pilot projects, the Community Benefits Framework will be developed in partnership with stakeholders, including the construction sector, social services, and community groups, in 2019. The Framework will:

- set the principles for promoting community benefits on all major public infrastructure projects

- establish roles and responsibilities of sponsoring ministries, the private sector and the community

- provide guidance to all participants on how to identify the affected community and to achieve community benefits

- encourage other orders of government, especially municipal and regional, to promote community benefits on their infrastructure investments.

- set reporting requirements

The government will ensure that all major public infrastructure projects comply with the Community Benefits Framework by 2020.

Modernizing apprenticeships and monitoring labour force needs

Ontario is working to modernize the province’s apprenticeship system. Ontario’s large-scale infrastructure investments provide an opportunity to support implementation of this strategy.

The Apprenticeship Modernization Strategy will aim to increase participation and completion rates for under-represented groups, while creating clearer pathways for all learners. This will help to ensure that Ontario has sufficient numbers of workers in the skilled trades to meet long-term demand in each sector and in related construction work. This includes a better understanding of what the construction sector of the future will look like, to ensure that apprentices learn about the technologies and approaches they will need to master as part of their training. Ontario’s new apprenticeship strategy will address these vital issues in partnership with labour, construction-sector employers and other stakeholders, including under-represented groups.

The Apprenticeship Modernization Strategy will propose concrete steps that the Province can take with its labour and construction partners to ensure apprentices have the skills to participate in Ontario’s infrastructure labour market over the next 10 years and further into the future. As part of the strategy, the Province will be supporting initiatives to ensure the infrastructure sector is reflective of Ontario, focusing on under-represented groups in the apprenticeship trades, such as Indigenous Peoples, newcomers, women, visible minorities and people with disabilities.

Ontario is also helping employers in the booming construction and agriculture sectors to find and retain the workers they need, through a new In-Demand Skills Stream of the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program (OINP). This enhancement to the OINP is a pilot project based on labour-market needs and input from trade unions, employers and other key stakeholders. The Province will closely monitor the pilot and make adjustments as necessary to ensure it meets the needs of employers.

The Province continues to modernize the OINP application process with paperless online systems, which speed up the application process and improve customer service. All applications for the In-Demand Skills Stream must be submitted online.

Attracting newcomers to help employers meet their labour-market needs is part of the Province’s plan to create jobs, grow the economy and help people in their everyday lives.

Ontario is committed to ensuring that its infrastructure investments support apprentices in building their skills and achieving their certifications. To complement the broader Apprenticeship Modernization Strategy, the government will consider an approach to ensure that implementation plans for major public infrastructure projects include apprenticeship positions, as is now the case for the Eglinton Crosstown LRT.

Infrastructure Ontario retained KPMG earlier this year to assess the capacity of the labour market to meet the pipeline of infrastructure projects in Ontario, Canada and the United States. Ontario will undertake future analysis, such as on a regional or sectoral basis, as needed, to understand the capacity of the labour market in Ontario, including for under-represented groups.

New housing construction has risen steadily over the last five years, adding more than 26,000 jobs since 2011. As Ontario continues to invest in major regional infrastructure, transportation and energy projects, low rates of unemployment in construction sectors are anticipated. Over the next decade, 86,000 are expected to retire, while 80,600 new entrants are expected to replace those leaving the workforce.

Footnotes

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph From Conference Board of Canada.

- footnote[12] Back to paragraph From Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission.

- footnote[13] Back to paragraph From Terrill, Marion.

- footnote[14] Back to paragraph From Government of Ontario.

- footnote[15] Back to paragraph From Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario.

- footnote[16] Back to paragraph From Yalnizyan, Armine.

- footnote[17] Back to paragraph From Build Force Canada.