4. Research and site analysis

Understanding the cultural heritage value of a property provides all parties with appropriate information to make decisions about the future of a property. Thorough research is essential in ensuring sufficient information for the evaluation of a property’s cultural heritage value or interest. The results of the research and a description of how it was undertaken will form part of the final written account, such as a designation report. Guidance on the format of a written report to support the identification and evaluation of a heritage property is included in section 6.

The historical research and site analysis needed for including a property on a municipal register is more preliminary in its scope. Properties being proposed for designation under the Ontario Heritage Act often require more in-depth study and should be evaluated by a qualified person or municipal heritage committee. See section 5.4 for further information on who is considered a qualified person. This involves:

- understanding and knowledge of the overall context of a community’s heritage and how the property being evaluated fits within this context

- researching the history and cultural associations of the property being evaluated

- examining the property for any physical evidence of its features or attributes, past use or cultural associations. The physical context and site are also important to examine. For example, other buildings, structures or infrastructure nearby may be associated with the property

This background information is best compiled through extensive historical research and site analysis, which complement each other. For example, the historical research might suggest that a house was built at a certain date. The architectural style, construction techniques and building materials may confirm or deny this as the date of construction.

Research is the process of consulting records and other documents to learn about the history of a property and associations it may have.

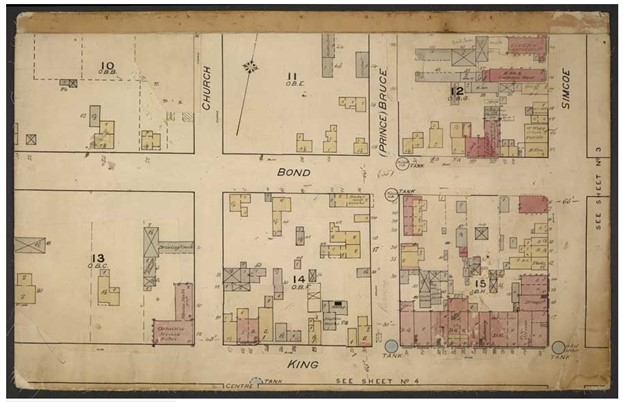

Research is necessary for compiling the specific history and development of a property and to identify any association it has to the broader context of community heritage. This involves the use of land records, maps, photographs, publications, archival materials, local knowledge, oral history, and other documentation.

Research may reveal significant people or events associated with a property, technologies, dates of construction, original and later uses, factors such as natural disasters or fires and other details about the property. This information is useful in the identification and evaluation of the cultural heritage value or interest of the property. It also provides clues for examining and interpreting the physical evidence.

4.1. Researching a property

Researching a heritage property to determine if it is of cultural heritage value or interest means:

Visiting the property

- examining physical evidence (site visits, photos and observations)

Understanding community context

- engage groups and individuals who have a past and/or present interest in or association with the property

- learn about community history and activities that may hold cultural heritage value or interest through research and direct community engagement. This could include focus groups and/or interviews with community elders or knowledge keepers

Undertaking historical research

- Review primary and secondary documentation (both current and archival written accounts, maps, drawings, plans and images)

- Search pre-patent land records for early properties

- Search Land Registry Office property abstracts and registered documents

- Review property tax assessment rolls

Analyzing physical evidence

- develop knowledge of construction, materials, architectural style and other related topics

- analyze and record the physical characteristics of the property

4.2. Site visit

The property itself is a primary source of information. A site visit to the property provides the most accurate information about its present state and may serve as a starting point for archival research. Valuable site visit records can be written and/or visual.

A site visit is a useful way to understand the context of the property. Many municipalities have codes of conduct for site visits or site review. It involves an examination of the grounds, buildings and structures (inside and out) to:

- provide current and accurate information about the property

- record the distinctive features including, but not limited to: obvious alterations, evidence of previous buildings or activities such as foundations or wells, and paths, vegetation, fences or other features

- record any interior features of the buildings or structures that contribute to the cultural heritage value or interest of the property

- photograph vistas and views, especially if the property is a known or potential cultural heritage landscape

Photographs should document the relationship of features of a property to one another, to the property and to the larger context. Photographs provide documentation of location, design, setting, materials, workmanship, character, and associations between present and past. The photographs may also reveal intrusions and/or missing features.

More than a single visit may be necessary, depending on the complexity of the property, documentary research, community input, or additional information acquired through research. Property owner consent would be required for any site visit that requires access to the property. Municipal policies and guidelines for site visits should be followed and use caution to respect rights to privacy and applicable laws.

Ideally, a property being evaluated should be examined at least twice. A preliminary site visit will give some context and raise questions to be addressed by the historical research.

A second site visit is an opportunity to look for physical evidence of these findings. Explanations or inconsistencies may be revealed in the existing features, missing elements or some hint or remnant that can now be examined in more detail. These will assist with further analysis and interpretation.

Recording the property using photographs, measurements and notes will help when applying evaluation criteria and compiling a description of heritage attributes. The evolution of architectural style, construction techniques, materials, technology, associated landscapes, and other factors are important information when analyzing a heritage property.

4.3. Oral history

The Oral History Association defines oral history as a “method of gathering, preserving and interpreting the voices and memories of people, communities, and participants in past events.”

Oral history is usually obtained through community input. This can be undertaken using focus groups or by conducting interviews with community elders or knowledge keepers, to gather information that may not be written down.

Oral histories associated with the property’s past and/or present can:

- reveal new sources of information

- provide information which may have not been previously recorded, but is relevant to understanding the cultural heritage value or interest of the property and

- provide greater context for understanding of documentary evidence

The role of oral history is of utmost importance in building our understanding of the past, particularly in the identification and evaluation of heritage resources from communities that rely on oral history as a form of storytelling, learning and commemorating. Oral histories let communities teach about their own cultures in their own words. Academics, researchers, and museum curators use such sources to highlight diverse and marginalized perspectives.

Once oral history is collected it can be recorded or summarized into the staff report or background research document, along with the source and date and location that the oral history was collected.

4.4. Documentary evidence

Documentary evidence to substantiate the history and cultural associations of the property, is found at local, provincial and/or national archives, libraries, museums, and historical societies. Analysis of documentary evidence should provide the historic context of the property and involve consulting:

- archival records

- results of screening for archaeological potential based on (MCM)’s Criteria for Evaluating Archaeological Potential

- archaeological reports, which will be reviewed for evidence related to the property’s overall evaluation and

- comparative studies or analyses, which explain the importance of the property within a municipal context by comparing it to similar properties locally. Effective comparative studies are based on:

- sound methodology and processes for identifying properties and property characteristic of comparative value and/or

- properties that may or may not be already included on the municipal register or other provincial and/or federal registers

Written records can include information on:

- current location and setting, design, materials, workmanship as well as on character and associations

- features that are either distinctive and/or diminished (i.e., an estimate of intrusions or missing elements based on what remains)

- obvious signs of previous activities (e.g., alterations in foundations, wells) and

- physical context (relations with nearby buildings, structures or associated infrastructure)

Visual records (sketches, measured drawings, photographs) can capture:

- relationship of features to one another, to the property and to the larger context

- views and vistas, which are particularly important if the property is a known or potential cultural heritage landscape

The historical research findings may reveal use of the property, key dates or associations not previously known.

Through historical research, a profile of the ownership, use, history, development, and associations of a property should begin to emerge. For some properties, it is the association with certain people, events or aspects of a community that have value or interest, support that cultural heritage value or interest, which are often only revealed through research. For some properties, the physical features may not be immediately evident, or they have been obscured and therefore there is a need to examine, interpret, and evaluate the physical evidence. When trying to identify and interpret any physical evidence presented by the property, knowledge of the following topics is useful:

- architectural styles

- construction technology

- building materials and hardware

- building types including residential, commercial, institutional, agricultural and industrial

- infrastructure such as bridges, canals, roads, fences, culverts, municipal and other engineering works

- landscaping and gardens

- cemeteries and monuments

- sites of significance to Indigenous community

Key questions

- What is the architectural style? When was it popular in your community? Are there additions or upgrades that can be dated based on style?

- What building materials or decorative features are used in the basic construction and any additions? Is it log, frame, concrete, steel, glass, or some unique material? Are there patterned brick, tiles, ornamental stone? Do they appear to be unique or help define the character of the property?

- Are there any processes and materials in nature that influenced the historical development or use? For example, a human response to geomorphology, geology, hydrology, ecology, climate, or native vegetation.

- Are there any historical activities that influenced development or modification? For example, activities in the landscape that have formed, modified, shaped, or organized the landscape as a result of human interaction.

- Are there any historical systems for human movement? For example, paths, roads, streams, canals, highways, railways, and waterways.

- Are there any historical manifestations of collective cultural identity? For example, features that indicate practices that have influenced the development of a landscape in terms of land use, patterns of land division, building forms, stylistic preferences, and the use of materials.

- Are there any historical, human-created shapes of the ground plane? For example, a three-dimensional configuration of the landscape surface characterized by features, orientation, and elevation such as earthworks, drainage ditches, knolls, and terraces or cultural or traditional adaptations of land use in response to natural topography.

4.5. Context and environment

A heritage property may have a single feature, or it may be in some context or environment that has associative value or interest. These could be, for example, a unique landscape feature, garden, pathways, or outbuildings. An industrial site may have evidence of the flow of the production process. The neighbourhood may have workers' cottages. A former tollbooth or dock may be near a bridge. There may be ruins on the property that represent an earlier or associated use. These elements are also important to examine for clues to the property. There is often evidence of these “lost” landscape features or remnants such as fences, hedgerows, gardens, specimen and commemorative trees, unusual plantings, gazebos, ponds, water features or walkways. These may have made a significant difference to how all components of the property related to each other or to the street.

Consideration should always be given to adjacent properties. This is especially important in an urban or main street setting where properties abut. The front, side and rear yard setbacks may have been prescribed by early zoning regulations within a planned community, or perhaps evolved over time without any plan.

The views to and from a property can also be significant. Views can be considered from an historic perspective, how did views develop or was there a conscious effort to create and/or protect views, and the relevance of views to and from the site today.

4.5.1. Historic context

The historic context of the property refers to an understanding of the property within the broader history of the province and the local community. The historic context is not intended to document the full history of an area or community, but to help inform an understanding of the development and evolution of an area’s built form and landscapes. In order to determine the historic context of the property the research should provide:

- relevant details of the history of the province, the local community, as well as any cultural associations of the property

- details of historical development patterns to help identify common themes

- evidence of historic patterns or trends that explain meaning and significance of a specific occurrence, property, or a site

Understanding the historic context of the property is important to determining the significance of a place, site, person, or event and can help to highlight themes or patterns within a community. Using historic context statements for heritage evaluations (or assessments) is a well-established practice and can help ensure a thorough understanding of the history and heritage of the area to be evaluated. Historic context statements should provide a concise explanation of what geographic, historical, and cultural trends significantly shaped the area’s land use patterns and built environment over time and identify important property types and characteristics that are representative.

Using a historic context statement differs from traditional approaches to history as it allows a focus on key historical and cultural processes, rather than topics or a chronological treatment. It aims to identify the key human activities that have shaped our environment. Themes are not arranged in a hierarchy or chronological order. They are designed to be applied and interlinked regardless of place or period. They can be used flexibly for different periods, places, and regions. This approach suggests a lively and dynamic history, giving a sense of ongoing activities over time rather than a static and vanished past.

4.6. Summarizing research for evaluation

A comprehensive research methodology involves a review of documentary, physical and oral evidence uncovered through investigations and public consultation. Research materials should:

- merge and summarize the oral, documentary and physical evidence to provide a comprehensive history of the property (through written narrative, sketches, drawings, photographs, charts, etc.), and explain:

- the principal physical features associated with the property's history

- its cultural associations/meanings

- changes and the reasons for change over time, including the relationships between the past and present features of the property

- the overall historic context

- be collated in a logical manner that draws connections between the available data and the qualified person’s analysis

- assist with an accurate and full application of the criteria of Ontario Regulation 9/06, i.e., substantiate whether the property is of significance to the community or the province

The results of the research as well as a description of how it was undertaken will form part of the final written account.