Advisory group report on protecting the Muskoka River Watershed

Read the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group’s interim report on issues and priorities for protecting the watershed and supporting the local economy.

June 29 2020

The Honourable Jeff Yurek

Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

777 Bay Street, 5th floor

Toronto, Ontario M7A 2J3

Re: 2020 Report of the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group

The Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group is pleased to provide you with its report containing interim advice and recommendations in support of the development of the Muskoka Watershed Initiative. We celebrate the opportunity this Initiative offers to ensure the ecological health and sustainable future of the Muskoka River Watershed. We believe the advice and recommendations contained in this report may be used to inform work being done in other jurisdictions to help protect the province's water resources and pass on a cleaner environment to future generations.

The recommendations of the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group are comprised of 19 distinct projects that fall into three broad categories:

- Integrated Watershed Management: The Primary Recommendation

- Flood Mitigation to Address Spring Flood Risk: The Most Pressing Need

- Specific Projects for Enhanced Watershed Health

The Advisory Group views the implementation of Integrated Watershed Management (IWM) as its most important recommendation. IWM presents the best approach for management of the complex and interrelated issues facing the Muskoka River Watershed, including spring flood risk as a specific concern. We recommend the Province take a leadership role in supporting the implementation of IWM and the collaborative approach it will require.

The Advisory Group notes the high level of interest expressed by the public in having the opportunity to read the advice and recommendations contained in this report and encourages the Minister to consider its timely release. During its outreach the Advisory Group received feedback from many entities, organizations and individuals, that there is great interest in seeing this report released in full to the public.

The Advisory Group would be pleased to offer a call or meeting with the Minister to walk through the report and answer any specific questions. We appreciate the opportunity to have contributed to the development of the Muskoka Watershed Initiative, and have recommended for your consideration a continuing role for our work including; support of the scoping, definition and implementation of any projects at the request of the Minister, assistance in identifying municipal, federal and private funding opportunities and the fulfillment of any community engagement requests at the request of the Minister.

Sincerely,

Mardi Witzel

Chair, Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group

Members of the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group: All members served as co-authors

- Mardi Witzel, Chair

- Don Smith, Vice-Chair

- Patricia Arney

- John Beaucage

- Julie Cayley

- Chris Cragg

- John Miller

- Kevin Trimble

- Norman Yan

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support received from Ling Mark, Madhu Malhotra, Neil Levesque and Tahseen Chowdhury of the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, and for the contributions provided by Dr. Andrew Paterson, Erin Cotnam, Chris Near and Dr. Barb Veale in assisting us with our work over the past ten months and in the preparation of this report.

In addition we would like to acknowledge the efforts and interest of the many local municipal representatives, First Nations, community organizations and members of the public who took the time to attend our listening sessions and provide valuable input to our process.

A special word of thanks is extended to the Honourable Jeff Yurek, Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, for recognizing the importance of long-term watershed health, and inviting the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group to provide advice and recommendations in support of the development of the Muskoka Watershed Initiative.

Disclaimer

This report has been completed in accordance with the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group terms of reference as established by the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks. This report represents the input and advice of a diverse group of individuals, and the recommendations contained within represent a consensus perspective, where consensus refers to general agreement which may not be entirely unanimous.

Executive summary

In August 2018, the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks ("Ministry" or "MECP") announced the creation of the Muskoka Watershed Conservation and Management Initiative ("Muskoka Watershed Initiative" or "Initiative"). The purpose of the Initiative is to better identify risks and issues facing the Muskoka region, allowing the community and the Province to work together to protect the environment and support economic growth. The Muskoka Watershed Initiative will help to protect the province's water resources and pass on a cleaner environment to future generations.

To assist the government in delivering the Muskoka Watershed Initiative, the Ministry created the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group ("Advisory Group"), comprised of nine volunteers representing a cross-section of education and experience backgrounds and with deep roots in the Muskoka community. The Advisory Group is charged with providing advice and recommendations to the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks regarding the Muskoka Watershed Initiative, specifically a strategic assessment of priority issues and the types of projects that could be undertaken in the Watershed.

The advice and recommendations of the Advisory Group, contained in this report, have been prepared following an extensive period of community outreach with over 60 distinct entities including municipal governments, First Nations, lake associations, stewardship organizations, economic stakeholders, waterpower producers, local planners and consultants, local educators, representatives from the local agricultural industry and members of the general public. The Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group has chosen to focus its efforts on the Muskoka River Watershed (the "Watershed") and its 15 sub-watersheds, but highlights here the belief that many of the recommended projects can be leveraged into other watersheds across the province.

The Advisory Group was announced in August 2019, on the heels of a devastating "100 year" spring flood in Muskoka. During outreach, the Initiative's aspiration for a 'broader, more comprehensive approach to watershed management in Ontario' was reinforced. The message got through. While the community had lots to say about flooding, what is striking is the number and breadth of issues raised – over 200 raw issues. These were examined and distilled into a smaller number of issue categories for discussion.

Following from the Advisory Group's terms of reference, the identification of issues and threats is understood to be for the purpose of protecting the environment while supporting economic growth. On this basis, it was determined that the group would focus on the identification of environmental and/or ecological issues, then discuss and prioritize them according to environmental, economic and social impacts.

Issues of the Muskoka River Watershed

The Muskoka River Watershed environment is changing. Evidence of this is seen in changed patterns of weather and precipitation, increases in the incidence of flooding and major storms, the presence of invasive species and diseases affecting our forests and wildlife and the challenge of new and poorly understood threats to the quality of our water. These changes are largely the result of climate change and/or human development projects that have altered the natural environment. In this sense, climate change and land use practices are viewed as causal factors or issues that create and then interact with other issues.

Four environmental issues top the list facing the Muskoka River Watershed:

- Increased incidence, severity and risk of flooding

The 2019 Watershed flood event represented the second '100 year flood' in Muskoka, and the third flood, in six years (2013, 2016 and 2019). In order to develop flood mitigation strategies to protect the existing high-value built infrastructure, there needs to be a clear understanding of the root causes of fluctuating water levels in the Muskoka River. This is important due to the extensive environmental and socio-economic costs of flooding. - Increased incidence of erosion and siltation

Erosion and siltation occur due to fluctuating water levels throughout the Watershed, and in some cases become severe enough to damage infrastructure, impede navigation, potentially harm water quality and devalue property. The root causes of erosion and siltation are not constant but reflect the varying geological conditions and patterns of water level fluctuations experienced. There is a need for both remediation and further study. - Existing and emerging threats to water quality

Both expert opinion and community input suggests water quality is generally very good in the Muskoka River Watershed, but there are existing and emerging threats. There was considerable overlap from multiple sources, highlighting five specific threats to water quality in the Watershed; widespread calcium decline, sometimes called 'ecological osteoporosis,' increasing levels of road salt in our waters, emerging contaminants, phosphorus from septic systems and hazardous algal blooms (HABs), especially blue-green algae blooms. - Existing and emerging threats to biodiversity and natural habitat

The Muskoka River Watershed is rich in natural resources and biodiversity which are key to ensuring a healthy environment, strong communities and a thriving economy. Habitat and biodiversity are interconnected with virtually all other issues facing the Watershed. After discussion and analysis of the issues, the Advisory Group identified the following existing and emerging threats: erosion, fragmentation/loss of corridors, invading species, loss of biodiversity, loss of forest health, loss of stream networks, threatened species and wetland loss.

In addition to environmental concerns, two management issues top the list:

- Watershed governance

- Land use policy

The work of the Advisory Group suggests the existing set of land use policies has contributed to the rise of environmental issues in the Watershed today. In terms of governance, the Advisory Group finds that the current fragmented approach to analysis, decision-making, programming and communications in the Watershed does not serve it optimally. There is variance in the extent to which these issues generate impacts on environmental, ecological, economic and/or social grounds, but in all cases the impact is significant.

Types of projects for the Muskoka River Watershed

The recommendations of the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group fall into three broad categories:

- The most important recommendation: integrated watershed management

- The most pressing need: flood mitigation to address spring flood risk

- Specific projects for enhanced watershed health

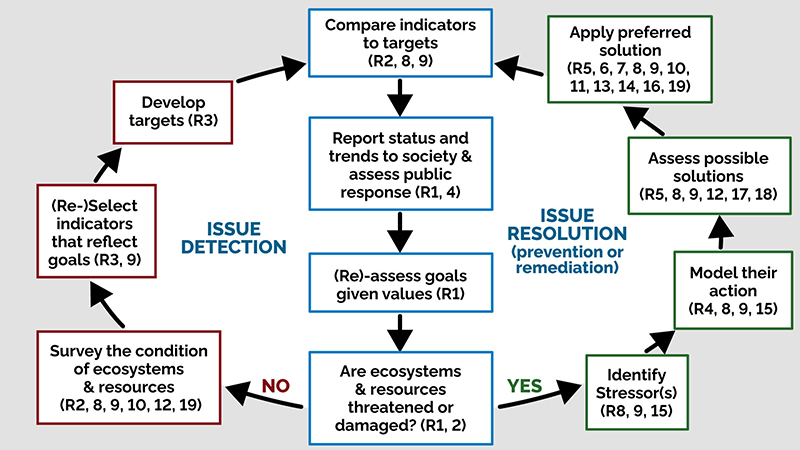

Reflecting the complex and interrelated nature of issues, the Advisory Group recommends a fundamental and overarching solution is needed for the Muskoka River Watershed and this can best be provided through Integrated Watershed Management (IWM). IWM is needed to fully address the interconnected causes of our most urgent and critical issues today. IWM also offers an approach for long-term resolution, incorporating future land use practices and the ongoing effects of climate change through a coordinated watershed-wide approach.

IWM is the most important overall "project type" to initiate in order to achieve the province's goals of better identifying risks and issues facing the Muskoka River Watershed, and ultimately providing solutions. Because this is a relatively longer-term, large-scale process, and recognizing the presence of a number of urgent and pressing concerns today, in developing its advice and recommendations, the Advisory Group has taken the approach that some project types will initiate the large-scale, long-term IWM approach while other high priority project types will be geared toward more specific issues with two interrelated objectives: a) contributing to key steps in the IWM planning process and b) providing shorter-term solutions to specific issues.

Integrated watershed management: evidence-based decision-making

According to an IWM White Paper prepared by the Muskoka Watershed Council (MWC), "Typical environmental management proceeds as a set of separate, siloed tasks undertaken by different tiers of, and departments within government, and different sectors of society. Integrated Watershed Management (IWM) is organizationally more complex; introducing IWM requires significant commitment from participating levels of government, ministries, agencies, and all community sectors, if it is to be successful. At its simplest, IWM brings a science-based, ecological perspective to environmental and land use management, recognizing that the broad range of ecological processes operates across landscapes, and that management is best done on the same scales and using natural boundaries without regard to municipal boundaries."

Ultimately, IWM provides an evidence-based approach by which land use decisions, environmental projects, infrastructure projects and broader public policy options can be assessed in terms of their impacts. In this sense, IWM provides a tool by which policymakers and watershed managers can evaluate the merits of proposed interventions in both environmental and economic terms. IWM provides a best-in-class approach to facilitating management decisions that are effective at sustaining natural capital and supporting current economies and lifestyles.

Flood mitigation: the most pressing need

The Advisory Group recognizes the significant costs of flooding in the Muskoka River Watershed in recent years, and the sense of urgency around developing approaches to flood mitigation. Flooding exerts environmental, social as well as economic costs, and flood mitigation is the most pressing current need facing the Muskoka River Watershed. A set of short-term and medium-term recommendations for flood mitigation that reflect the work of the Ontario Flood Advisor are presented here.

These flood mitigation strategies build upon the plans set out in the Ontario Flood Strategy, offering recommendations specific to the Muskoka River Watershed. In particular the recommendations in this report around flood mitigation address three priorities outlined in the Ontario Flood Strategy – Understand Flood Risks, Strengthen Governance of Flood Risks and Invest in Flood Risk Reduction. Building upon these strategic provincial plans, the project types recommended in this report call for the creation of a Flood Mitigation Mandate to be assumed by a newly formed technical Water Quantity Task Force in the Muskoka River Watershed. The strategies for flood mitigation are captured in recommendation 8.

Specific projects for enhanced watershed health

A number of specific projects are recommended to enhance watershed health on a wide range of watershed issues. The Advisory Group recommends these specific types of projects be started in parallel with the large-scale undertaking of IWM, both because these issues should be addressed, and because their results will improve the ability of IWM to recommend more effective watershed management decisions. Recommendations 9 through 19 lay out the specific projects designed to enhance watershed health.

Concluding comments

The Muskoka Watershed retains many natural features, and its forests and 2000+ lakes make it a highly-valued environment, and according to National Geographic, one of the world's premier recreational destinations. Approximately 82% of the Watershed retains natural cover, with high biodiversity and functional ecological systems that support a number of species at risk. The MWC Report Card from 2018 reports that 18% of the watershed has been extensively modified for human uses. Nonetheless, it speaks to the general health of the Watershed that town residents sometimes have to sidestep deer, bear and the occasional moose in their communities.

Past scientific research on Muskoka lakes has changed the ways problems in lakes are understood and managed around the world. Without the scientific services provided by Muskoka lake scientists, our lakes and our use and appreciation of them would have suffered, dragging down our economy in consort. This is going to be even more true going forward with the pressures of climate change and development.

There's an Anishinabek teaching that speaks to the place that human beings hold in creation:

All of creation was in place before humans were put on the earth. Everything that we see walking, flying, swimming or crawling was here before us. All of creation can exist and thrive without human beings. One of the gifts that we were given was the ability to exert control over our immediate surroundings, to make life easier and more comfortable for us. In exerting that control, it is essential that we remind ourselves that if we throw our immediate environment out of balance, we may also make life impossible for ourselves and for those creatures weaker than ourselves. So as we develop, build things, change our environment to suit ourselves, we must take heed to look after the little creatures. If our actions destroy them, we are in a way destroying ourselves. If we think about how to preserve life no matter how small and insignificant, we are looking after ourselves and our descendants. All of our decisions must take into consideration how it will affect events seven generations from now.

The Advisory Group has been honoured and inspired to volunteer through this phase in support of the development of the Muskoka Watershed Initiative.

Recommendations

Integrated watershed management

Flood mitigation

Specific projects

Beyond the overarching project type aimed at streamlining the existing water quality programs, the following sub-projects are recommended for program enhancement:

Introduction

The Muskoka Watershed Initiative

In August 2018 the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks ("Ministry" or "MECP") announced the creation of the $5 million Muskoka Watershed Initiative (MWI). The purpose of the MWI is to better identify risks and issues facing the Muskoka region, allowing the community and the Province to work together to protect the environment and support economic growth. The MWI will help to protect the province's water resources and pass on a cleaner environment to future generations.

In addition to the $5 million, the Province will also match tax-deductible donations to the MWI, from individuals, businesses, and/or other levels of government up to an additional $5 million for a potential total fund of $15 million.

To assist the government in delivering the MWI, the Ministry created the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group ("Advisory Group"). The purpose of the Advisory Group is to collaborate with and support the Ministry in the development and implementation of the Initiative.

The Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group has chosen to focus its efforts on the Muskoka River Watershed (the "Watershed"), which consists of 15 sub-watersheds located primarily within the District of Muskoka. The Watershed measures about 62 km by 120 km, and discharges into Georgian Bay via the Moon River. In conceiving the MWI, the Ministry recognized the Watershed is facing pressures due to increased development, severe weather events resulting from the changing climate, increasing contaminants such as nutrients and chloride, management of species at risk and invasive species, and shoreline erosion. There is acknowledgement that local residents are concerned about water quality and water quantity management and the impacts of flooding.

The advice and recommendations of the Advisory Group have been prepared following an extensive period of community outreach. With this report, we advance actionable recommendations that may offer short-term relief from pressures, but as importantly, we make specific recommendations toward a proactive longer-term solution – the development of a comprehensive approach to watershed management in Muskoka. The recommended approach is Integrated Watershed Management, which recognizes the Muskoka River Watershed has extensive natural infrastructure as well as man-made control systems, and that both play a critical role in the Watershed's health and functioning.

Terms of reference

The Advisory Group was established in August 2019 to provide advice and make recommendations to the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks regarding implementation of the Muskoka Watershed Initiative.

Specifically, the mandate of the Advisory Group includes the following:

- Provide advice and make recommendations to the Minister regarding: priority areas, priority issues to be addressed and the types of projects that could be undertaken in the watershed

- Assist in identifying municipal, federal and private funding opportunities

- Participate with the Ministry in public and indigenous engagement efforts regarding the Muskoka Watershed Initiative, upon request from the Minister

- Communicate with local organizations and communities represented by the Advisory Group and bring these perspectives forward during Advisory Group meetings (subject to confidentiality provisions of the terms of reference)

In this report, the Advisory Group addresses the first and last of these tasks.

Background

Muskoka River Watershed

The Muskoka River Watershed retains many natural features, and its forests and 2000+ lakes make it a highly valued environment. According to National Geographic, Muskoka is one of the world's premier recreational destinations.

The Muskoka River Watershed is located in Ontario Shield Ecozone Ecoregion 5E (Georgian Bay Ecoregion). Its headwaters originate in Algonquin Park and flow southwesterly for approximately 210 km, into the southeast corner of Georgian Bay. The Watershed measures approximately 62 km in width by 120 km in length, and encompasses an area of approximately 5,100 sq km. Three main drainage areas exist within the Watershed; the North Branch, the South Branch and Lower Muskoka. The combined flow for all three drainage areas passes through Lake Muskoka at Bala, then down the Moon and Musquash Rivers and ultimately discharges into Georgian Bay.

The list below captures key development and use characteristics of the Muskoka River Watershed:

- Approximate permanent population: 61,200

- Approximate seasonal population: 82,300

- Number of municipalities (part or whole):

- 13 area municipalities

- District of Muskoka

- County of Haliburton

- Number of major towns: 3 (Bracebridge, Gravenhurst, Huntsville)

- Number of villages and hamlets: 11

- Number of municipal wastewater systems: 8

- Number of water control structures: 42

- Number of navigation locks: 3

- Number of hydro generating stations: 11

The paragraphs below provide characteristic highlights of the Muskoka River Watershed, referencing the work and reporting of the Muskoka Watershed Council.

Physiography and topography: The Muskoka River Watershed lies on the Canadian Shield and has as key features ancient, weathered, sparingly-soluble granitic bedrock, overlain by thin glacial tills. The topography is varied, ranging from the rugged highlands of the Algonquin region, to rocky knolls and ridges throughout the middle and lower portions of the Watershed, and small areas of flat, open farmland. While soils are typically sandy and shallow (typically only 10 to 30 cm) atop the bedrock foundation, smaller areas of deeper deposits of sand, silt and clay can be found in the valleys in the centre of the watershed. The Watershed is heavily forested, with second or third growth mixed hardwood and coniferous species. A few patches of old growth forest remain in inaccessible areas of Algonquin Park.

All of Canada was under ice 20,000 years ago, and glaciers receded from Muskoka about 10,000 years ago, leaving a very altered landscape. All the forests and much of the soil were removed exposing the pot-holed bedrock. This coupled with the fact that Muskoka receives about 1 metre (water equivalent) of rain and snow a year, only half of which is lost to evaporation and transpiration, meant that all the depressions filled with flowing water that supported a few arctic imports, including the lake trout. It is this glacial history and climate that gave Muskoka the lakes that have made it so popular.

Climate: The Watershed experiences cool to moderate temperatures and is one of the wetter areas in the province. The average annual precipitation is roughly 1,000 mm of water equivalent, including nearly 3,000 mm of snowfall. But these past averages may not last. Global climate change is likely to alter Muskoka climate by mid-century making it warmer and slightly wetter than at present, with the prospect of more extreme precipitation events.

Fisheries: Roughly 30 species of fish inhabit the Muskoka River Watershed, mainly cool and cold-water fish species such as Lake and Brook Trout, Yellow Perch, and the predators Smallmouth Bass, Walleye, Northern Pike, Muskellunge. Bass populations are predicted to increase with a warming climate, and pike introductions are a concern for some that prefer native fish assemblies. Many of the important fish spawning areas in the system are located below the many rapids and dams, and along lake shorelines. These critical habitats can be affected by fluctuating water levels and flows and by erosion and siltation associated with removal of riparian vegetation.

Wildlife: The Muskoka River Watershed is home to a diversity of mammal, reptile, amphibian and bird species. According to the Vital Signs Report, 250 species of birds, 50 species of mammals and 35 species of reptiles and amphibians call Muskoka home. The life cycle, health and abundance of these species is influenced by how we treat land cover in forests in riparian zones and nearshore waters. The lakes, rivers, wetlands, forests and soils comprise a linked complex on which native species are dependent for habitat and food.

Settlement: With the retreat of the last glaciers, the Muskoka region would have been cold, forbidding, and difficult to populate for quite some time. By about 5,000 years ago, before the building of the pyramids in Egypt, the Watershed was inhabited by First Nations; first the Algonquin, then Iroquois, and by the mid 18th century, the Ojibway. European settlers were drawn to the area by the timber industry in the mid-to-late 1800s, and the first sawmill was built in 1865. The first tanneries came to Muskoka at roughly the same time, and by the late 1800s, Muskoka supported some of the largest tanneries in Canada.

Settlers were also drawn to Muskoka by land grants under the 1860 Public Lands Act. Many intended to farm until they were deterred by the poor soils, abundance of rock and many swamps. They then turned to renting rooms to visiting hunters and fishermen. This led to construction of many seasonal hotels between 1880 and 1900, to accommodate the "tourists", several of which still operate today.

Muskoka is also distinguished by its many islands and – thanks to the water regulation by its many dams – by stable water levels during the summer "navigation season". This encouraged many cottagers to acquire wooden boats for personal transport and to construct boathouses for summer and winter storage of these boats. Muskoka's wooden boatbuilders are internationally famous and its boathouses make the region unique. Today Muskoka is home to approximately 60,000 permanent residents and slightly over 80,000 seasonal residents.

Hydroelectric power generation: Hydroelectric power production has been and continues to be an important part of the local economy. Today, there are eleven hydroelectric generating stations in the Muskoka River Watershed; four owned by Ontario Power Generation (OPG), three by Bracebridge Generation, two by Orillia Power and one by Swift River Energy Limited (SREL). These facilities cooperate with the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forests (MNRF) in the control and management of water levels and flows in the Muskoka River and operate under the Muskoka River Water Management Plan 2006 (MRWMP).

Economic and social: Cottaging and tourism are the two largest economic drivers in the Watershed today. Tourists, seasonal and permanent residents contribute to the economic base through the consumption of goods and services. Commercial and business operations within the Watershed are concentrated along transportation corridors, in the three town centres of Bracebridge, Gravenhurst and Huntsville and in proximity to the lakes and their shorelines. The scale of the economic impact of seasonal residents in the Muskoka Watershed is huge. The District of Muskoka acknowledges the role of seasonal residents as a significant component of the District's economic backbone, and in 2016 the economic impact of seasonal resident expenditures was estimated to be $421 million.

The Vital Signs Report reveals a study in contrasts, opportunity and challenges. A strong but mainly seasonal tourist economy is evidenced by the three million person visits to Muskoka which occurred in 2016, two-thirds of which took place between July and September. In that year total visitor spending exceeded $500 million in the District of Muskoka. The 2016 report also underscored the socio-economic challenges in Muskoka; median employment income was 21% below the provincial average, 13% of Muskoka residents were living in poverty, 25% of households were spending more than 30% of their income on shelter costs and 43% of all jobs were in sectors where the work is largely seasonal.

In addition to the two key economic drivers of tourism and cottaging, Muskoka has a long tradition of other industries and adapting to develop new opportunities. In its earliest days, Muskoka was home to a significant lumbering and wood processing industry that depended on the Watershed for harvesting logs, generating power and shipping product. Today, locally-developed industries serve not only the local population but supply other markets. Significantly, Muskoka is located just north of almost 9.25 million people – over 68% of Ontario's population – living in the Greater Golden Horseshoe region. Muskoka manufacturers ship everything from electronics products to refined aggregates throughout the country and to international markets. From 1-Gigabit fibre-optic internet to a Canada Customs Airport of Entry, Muskoka is connected to the world.

Muskoka also has a growing public service sector, strong real estate and construction sectors

In 2011 and 2012, National Geographic rated Muskoka as one of the top destinations in the world to visit. The beauty of Muskoka's physical environment and its 'over 1000 lakes' was noted, with the area being characterized as a 'natural playground' that was both accessible and capable of offering an 'unplugged pace.'

Community outreach

The Advisory Group is comprised of nine volunteers representing a cross-section of educational and experience backgrounds, all with deep roots in the Muskoka community. A first meeting was held in September 2019 in Bracebridge, Ontario. By early October 2019, a preliminary project plan had been developed including a list of community outreach targets, and initial outreach sessions were being scheduled. The Advisory Group's first outreach meeting was held on October 28, 2019.

Early-on, the Advisory Group determined it would seek to augment members' understanding and knowledge of the issues and opportunities facing the Muskoka River Watershed with those from a wide range of local organizations. Therefore, input was solicited from anyone in the community who chose to provide it. From October 2019 through April 2020, the Advisory Group held one-on-one sessions, small meetings and larger listening sessions. Outreach included meetings with representatives from municipal government, First Nations, lake associations, local stewardship organizations, economic stakeholders, waterpower producers, local planners and consultants, local educators, representatives from the local agricultural industry and members of the general public. In addition to hosting a community listening session where over 100 members of the public attended, Advisory Group members met with over 60 distinct organizations/entities.

Several listening sessions were noteworthy in this phase of our process:

Municipal listening session, November 2019

The Advisory Group held a Listening Session in Bracebridge, Ontario, where the chair of the District of Muskoka and all thirteen of the municipalities (Mayor, Chair, Reeve) that touch the Muskoka River Watershed were invited. Representatives from the District and seven municipalities attended.

Community listening session, January 2020

The Advisory Group held an open Community Listening Session in Port Carling, Ontario, where the general public was invited to attend. The event was promoted in the weeks prior through a press release to media outlets, via the District of Muskoka's 'Bang the Table' social media channel and through the efforts of two larger community organizations: the Muskoka Lakes Association (MLA) and the Federation of Ontario Cottager's Associations (FOCA). Over one hundred people attended.

First Nations listening sessions April 2020

A First Nations Listening Session arranged for March 2020 was cancelled due to COVID-19 restrictions on travel and social distancing. The Advisory Group held teleconference listening sessions with First Nations and the Metis Nations of Ontario in April 2020. Participating representatives also carried information on the work and mandate of the Advisory Group back to their communities and invited broader input.

In order to facilitate submissions from the community the email account muskokawatershed.ag@gmail.com was set-up, and subsequently promoted through a press release and social media. Local organizations and members of the public were encouraged to attend the January 2020 Community Listening Session and/or submit questions, comments or full submissions to the Advisory Group using the Gmail account.

All input received from local organizations, including emails from the general public, was made available to the Advisory Group as a whole, and one member maintained a spreadsheet cataloguing this input according to a range of analytic criteria established by the group.

A list of the organizations with whom the Advisory Group met with and/or from whom input was collected is captured in Appendix B. A summary of input received is captured in Appendix C.

Issue identification and prioritization

Issue identification

In January 2020, a working sub-group was formed to address the question of how to prioritize issues. As a starting point, it was agreed that issues should be qualified according to our terms of reference, prior to any attempt to prioritize them.

In the context of the Muskoka Watershed Advisory Group terms of reference, the identification of issues and threats is understood to be for the purpose of protecting the environment while supporting economic growth. On this basis, it was determined the group would focus on the identification of environmental and/or ecological issues and prioritizing them according to environmental, economic and social impacts.

Therefore, it was determined that a problem or threat may constitute a "qualified issue" if the issue relates to health and/or management of the Muskoka Watershed and any one of the following is true:

- The issue presents a known risk or threat to Muskoka River Watershed environmental and/or ecological health

- The issue presents a suspected risk or threat to Muskoka River Watershed environmental and/or ecological health

- The issue presents a significant departure from historical and/or desired environmental or ecological behavior such that it is deemed a "prospective threat" to the Muskoka River Watershed

- The issue presents a risk or threat to effective management of the Muskoka River Watershed

Of the many issues surfaced during outreach, most were found to be relevant to the group's mandate, but a few were determined to fall outside the terms of reference. In addition, a considerable number of issues that were raised through our outreach were eventually determined to be projects or potential solutions to problems, rather than the problems themselves. Lastly, a smaller number of issues were decreed to be true issues but were determined to be significant also as underlying causes to other issues. The work of the Advisory Group distinguishes between these two types of issues – symptoms and underlying causes – in the interest of treating both where possible.

Issue prioritization process

The working sub-group on issue prioritization developed a screening tool incorporating environmental, economic and social impact measures for review by the Advisory Group as a whole. Beginning in late February 2020 and continuing into April 2020, the Advisory Group undertook a review of all input received. Over 200 individual 'raw unqualified issues' had been raised through the outreach process. In this phase, the Advisory Group reviewed the input received, brought the perspectives of the community forward into discussions and began to identify, evaluate and prioritize the issues facing the Muskoka River Watershed.

Ultimately, issues were prioritized by qualitative methods, considering input from the community and a consideration of environmental/ecological, economic and social impacts informing the discussion of the Advisory Group.

Issues in the Muskoka River Watershed

While the Muskoka Watershed Initiative was announced by the Province in August 2018, the real activity from the public's perspective didn't start until August 2019 with the introduction of the Advisory Group. Getting to work in September 2019, on the heels of the devastating spring 2019 flood in Muskoka, the Advisory Group was mindful of the full range of emotions and frustrations around water levels and water levels management. Despite the terms of reference for the Muskoka Watershed Initiative citing the need for a "broader, more comprehensive approach to watershed management in Ontario," it was recognized many people would see the group as a flooding task force. Over the course of many months of outreach, Advisory Group members were careful to explain the mandate and solicit input reflecting its breadth. Repeatedly, it was explained issues relating to water levels and flows were an important element of the work, but not the sole focus, and matters related to water quantity would be considered as part of the Watershed's ecological system in totality.

The cumulative input from these outreach efforts indicates this message really got through. While the community had lots to say about flooding, what is striking about the input received, is the number and breadth of issues raised. Over 200 raw issues were raised by the public, by community organizations, civic leaders and First Nations and Metis Nations. The raw list of issues was examined and distilled into a smaller number of issue categories and discrete issues.

Table 1 captures the list of issues and issue categories upon which prioritization discussions were founded:

| Category | Issue |

|---|---|

| Water quantity-related |

|

| Water quality-related |

|

| Loss of natural assets |

|

| Climate change |

|

| Watershed management |

|

| Land use policy |

|

The changing Muskoka environment

The Muskoka River Watershed environment is changing. Evidence of this is seen in changed patterns of weather and precipitation, increases in the incidence of flooding and major storms, the presence of invasive species and diseases affecting our forests and wildlife and the challenge of new and poorly understood threats to the quality of our water. These changes are largely the result of climate change and human development projects that have altered the natural environment. In this sense, climate change and land use practices are Muskoka River Watershed issues of a distinct type; they are underlying causal factors, or issues that create and then interact with other issues.

A 2016 Muskoka Watershed Council (MWC) study took data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to make predictions for mid-century temperature and precipitation patterns in Muskoka. The predictions suggest Muskoka will experience warmer temperatures overall, with wetter winter/springs and drier summer/falls. The impacts of these shifts on the environment in the Watershed could be significant; greater risks of spring flooding, summer drought and fire, drier soil and wetland loss, changing zones of optimal growth of key forest tree species, increased probability of water quality issues, including algal blooms, and threats to the delicate balance of native species. The prospect of these changes is a beacon call for sound science, data and the tools to monitor, diagnose and manage the Watershed.

The topic of land use policy and development arose frequently in discussions of Muskoka River Watershed issues and health. The oft-cited tension between economy and environment was typically flipped on its head, with arguments the best way to grow the Muskoka economy and grow the tax base is by doing a better job of preserving and protecting the Watershed. A prevailing theme is the community's desire for future land use decisions to be subjected to a more rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of environmental and ecological impacts, including cumulative impacts. This is not to suggest an anti-development sentiment, but rather a zealous desire to avoid doing irreversible harm to the Watershed through over-development and irresponsible development.

To the extent the changes taking place in Muskoka's natural environment are attributable to climate change and land use policy, these have been viewed as underlying or causal factors. The Advisory Group recognizes climate change as an issue for Muskoka, and in this vein acknowledges a pressing need to plan for the development of greater watershed resiliency going forward.

Four environmental issues top the list of issues facing the Muskoka River Watershed; increased incidence, severity and risk of flooding, increased incidence of erosion and siltation, existing and emerging threats to water quality, and existing and emerging threats to biodiversity and natural habitat. In all cases, both climate change and land use policy play a significant role. In addition, two management issues top the list – governance and land use policy. The work of the Advisory Group suggests the existing set of land use policies has contributed to the rise of environmental issues in the Watershed, today. The current fragmented approach to analysis, decision-making, programming and communications in the Watershed does not serve it well. There is variance in the extent to which these issues generate impacts on environmental, ecological, economic and/or social grounds, but in all cases the impact is significant. Each issue and its associated impacts are discussed below.

Priority issues in the Muskoka River Watershed

Increased incidence, severity and risk of flooding

The Muskoka Watershed Initiative and the Advisory Group were announced in August 2018 and August 2019, respectively. In the interim, the major floods of 2019 struck the Province and the Province took significant action by commissioning a Special Flooding Study by an Independent Advisor

Water levels, water level management and flooding continue to be a sensitive topic to shoreline residents of Muskoka through the spring of 2020. Despite an early and benign resolution to the 2020 year’s freshet by April 14th, considerable ire and angst were generated by the subsequent raising of water levels by 0.2 m among Lake Muskoka residents, particularly those in Bala Bay. Residents were angry because this water level rise was unexpected by them (even though levels were within the upper Normal Operating Zone (NOZ) of the MRWMP), because water levels approached those of the recent floods, and seasonal residents were unable to access their properties due to travel restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the spring of 2019, a series of heavy rains combined with rapidly melting snow from a near record snowpack to generate severe flooding conditions across much of Ontario. There was devastating flooding in Muskoka. In addition to record high water levels, sheets of ice remained on the lakes during the flood and high winds blew these into lakeside structures, intensifying the level of damage. The District of Muskoka and three local municipalities declared states of emergency as rising water levels resulted in damage to docks, shorelines, homes, boathouses and significant economic impacts to property owners and businesses. In 2013 the flooding was called the worst in a century, but the water levels in 2019 surpassed those from six years before. The 2019 flood event represented the third flood in six years.

Following a flood in 2016, the Muskoka Lakes Association conducted a survey which found hundreds of lakeshore property owners experienced damage, ranging from minor decking issues to major structural building impacts. The survey found $4M in estimated damages from 414 responses that provided damage repair estimates and projected that direct lakeside damages exceeded the $50M estimate for 2013.

An issue the Advisory Group heard repeatedly during outreach, is the lack of a "quarterback" for flooding. The Report of the Ontario Flood Advisor acknowledges this saying; 'while the MNRF generally takes the position that municipalities are exclusively responsible for identifying hazardous areas, provincial policy is unclear and at times contradictory, and has created some confusion over who is responsible for identifying hazardous areas.'

In Muskoka, there is no one entity or framework that brings together the role of hazard area identification with the liability for land use decisions. By extension, in Muskoka it is unclear who has the responsibility for investigating, developing and recommending flood mitigation strategies to protect existing infrastructure and the authority to implement such recommendations.

Understanding and addressing the root causes of flooding is important due to the extensive environmental and socio-economic costs of flooding. Flood damage to public infrastructure in urban areas – roads, bridges, buildings etc. – is costly for the municipalities. Boathouses and waterfront structures of significant value are not insured but bear the brunt of the flood damage either from water or ice or floating debris. Businesses from Huntsville to Bala were submerged, forcing closure and extensive renovations with the resultant loss of revenue and cost of repair and/or increased insurance rates.

Excellent water quality is one of the most valued natural assets of Muskoka and it is environmentally costly to have it repeatedly threatened by flooding which impacts too many septic systems, particularly older ones built closer to the shoreline than would be permitted today. Additionally, shoreline erosion and siltation caused by flooding has been identified as a significant 'issue' for this report.

In conclusion, flooding in the Muskoka River system has become more frequent and more severe in recent years. The economic and social impacts for residents and business owners are negative and profound. There are also environmental consequences to flooding in terms of shoreline erosion, siltation, disturbance of pollutants, septic system overflows and more. With the influence of a changing climate, people in Ontario can expect to see more floods and more droughts. This will be a major issue for Muskoka. Relatedly, the lack of clear leadership on the issue of flooding has resulted in growing skepticism of government agencies and other organizations involved and the communication of information about policies that may or may not be correct.

Increased incidence of erosion and siltation

The erosion of shoreline throughout the Muskoka River Watershed is a naturally occurring process, but human activity has compounded the significance of erosion in many areas, particularly on the open lakes. The recent flooding events of 2013, 2016 and 2019 have manifest new areas of concern from a perspective of erosion and siltation. In the area of the Muskoka River Delta at Bracebridge, exceptionally high water levels and flow volumes resulted in substantial erosion, damage to built infrastructure and silt deposits. The silt deposit has created navigational concerns for both recreational and commercial operators on the Muskoka River.

Since the earliest settlement of Muskoka, the Muskoka River has been a major waterway and transportation corridor. Steamships from Gravenhurst regularly travelled the river as settlement pushed northward. Today, pleasure boats are the dominant traffic on the Muskoka River from Lake Muskoka to Bracebridge Falls. However, commercial craft and tour boats also navigate the river. The shores of the Muskoka River have become well-developed and are occupied by numerous permanent homes, seasonal residences, boathouses, docks and several commercial endeavours.

In a 2019 submission to the Province of Ontario, the Town of Bracebridge advised: "As a first step in understanding the siltation problem and to assist in the development of an action plan to address issues of the Muskoka River from Bracebridge Bay Falls to Lake Muskoka, the Town held two (2) public open house events in 2015 to permit property owners, commercial operators, and others who utilize the Muskoka River to provide background information to the Town regarding its long-term future and need for potential remediation to ensure safe navigation. Approximately 81 individuals attended the meetings, and 41 questionnaires were collected at the end of the meetings."

Attendees noted substantial damage to properties during flooding of the river and the need for dredging of the river. This input was received following the 2013 flood event but prior to more severe flooding that occurred in 2019.

It is anticipated that future flooding events will continue to create erosion along the Muskoka River from Bracebridge Falls on the North Branch and South Falls on the South Branch to the mouth of the Muskoka River. This erosion will devalue property, create damage to built infrastructure, impact water quality and leave growing silt deposits.

Relatedly, while the Advisory Group finds the siltation in the Muskoka River Delta to be one of the most urgent and aggravating examples of its kind in the Watershed, feedback from the community also highlighted other situations. Interestingly, the root causes of erosion and siltation are not constant, but rather reflect the varying geological conditions and patterns of water level fluctuations experienced. Mary Lake Association, for example, reports significant shoreline erosion and associated economic and environmental costs. This is attributed to Mary Lake's 'soft shoreline' which leaves it vulnerable to long duration high water.

Existing and emerging threats to water quality

The Advisory Group used several approaches to identify priority water quality issues in the Watershed including engagement with local experts, a scan of recent scientific literature for overviews on emerging threats to global freshwater ecosystems and broad consultation with the local community. There was substantial overlap in the feedback from these sources of information. Science and technical staff from the MECP noted water quality is generally very good in Muskoka, but identified calcium decline, road salt, climate change, novel algal blooms, and their potential cumulative effects as key emerging issues for Muskoka lakes. Secondly, Reid and colleagues' (2018)

- Widespread calcium decline

- Increasing levels of road salt in our waters

- Emerging contaminants

- Phosphorus from septic systems

- Hazardous Algal Blooms (HABs), especially blue-green algae blooms

Each issue is described in brief, below. Logical linkages to climate or land use change are highlighted, along with interactions with other issues the Advisory Group is considering. Additionally, examples of the possible broader environmental, economic and social implications of the water quality issues are provided, where reasonable guesses are possible.

The five water quality issues

Calcium (Ca) Decline: Acid rain stripped roughly half a tonne of Ca per hectare from Muskoka soils over the last 50 to 100 years. Given that Ca levels in the thin, base-poor soils of Muskoka were low to begin with, this acid-induced loss means the growth of many trees in the Watershed is now limited by Ca availability. Because streams, lakes and their biota get the vast majority of their Ca from watershed soils, Ca levels in remote Muskoka waters have fallen by roughly 25% over the last forty years, and levels in about half of Muskoka lakes are now low enough that calcium-rich animals such as crayfish and Daphnia are suffering population losses. The Muskoka Watershed Council (MWC) indicated ecosystems of half of Muskoka's lakes are now suffering from Ca decline, and levels won't recover any time soon, perhaps not in centuries, according to biogeochemists, without some sort of intervention.

The link between Ca decline and climate change is also a concern in the Watershed. Calcium-limitation increases the susceptibility of trees to wind and pathogen damage. Because Ca-limitation reduces photosynthesis, tree growth slows and carbon capture is reduced, lowering the ability of Muskoka's natural landscapes to mitigate climate change. There may also be a link to flood risk, as transpiration rates of Ca-limited trees are dramatically reduced. Soils and wetlands in the Watershed may be holding more water at freeze up than they did prior to acid rain, and thus may be less able to absorb melt waters in the spring now, in comparison to a century ago.

Among tree species, sugar maple has a particularly high Ca demand, so is among the first trees to suffer from Ca-depletion of forest soils. Local sugar bush operators are very aware of this problem, having seen the health of their forests decline, and their livelihoods potentially threatened. Two local bush owners have spent tens of thousands of dollars to supplement sections of their sugar bushes with Ca. The economic threat to these residents is real.

Road Salt: Ca decline affects half of Muskoka's lakes, but its geographic distribution is completely different from the second most widespread water quality threat – chloride pollution from road salt. Road salt is currently damaging about 20% of lakes in Muskoka, and unlike Ca decline, this issue is found only in lakes near winter-maintained highways, roads, parking lots and sidewalks. The clearest example may be the iconic Muskoka Bay of Lake Muskoka. There, while Ca levels are the same as they were 40 years ago, chloride (Cl) levels are climbing yearly and now average about 15 mg/L, roughly 30 times higher than background levels. Animal plankton are damaged at between 5 and 40 mg/L of Cl in the lab, according to new research from Queen's University, and there is growing evidence from Jevins Lake, near Gravenhurst, road salt can damage entire open water food webs at a Cl level below the current Canadian Water Quality Guideline.

The cause of Cl pollution across Muskoka is clear. Almost perfect balance of sodium with chloride levels indicates it is road salt. The source is also clear – winter maintenance of roads, highways and parking lots. In addition to damaging lakes, excessive use of road salt also damages vehicles and buildings, concrete, bridges, clothing and our pets, adding enormous expenses to individuals, families and municipalities. As the total use of salt in watersheds generally increases with road density, it is up to government to reverse the trend of rising chloride pollution as Muskoka's population grows. Climate change may also worsen the problem in two ways. First, the changing climate has resulted in more lake-effect snow in Muskoka, and as winter temperatures warm, there will be more freeze/thaw cycles and more days with temperatures within a range where sodium chloride (NaCl) works as a de-icer. Therefore, both ongoing development and climate change may increase the pressure to use salt in winter road maintenance.

Contaminants: Calcium decline and road salt are quite straightforward issues is many ways, but the same cannot be said for contaminants. The European Chemicals Agency estimates there are more than 144,000 manmade chemicals, the majority of which are unregulated, and a few thousands new ones are introduced every year. Industrial chemicals are now routinely present everywhere - in food and in water, and in every habitat on earth and in the plants and animals that populate them, including us. It isn't a surprise to the Advisory Group the issue of contaminants was raised by Muskoka residents. The challenge is grappling with it.

While it did not come up during community outreach, mercury pollution does remain a sport fish contaminant of concern in Muskoka; however, dramatic reductions in coal combustion, and in reduced disposal of mercury in batteries, electronic switches, paint and other commercial products has lowered the mercury supply to the environment. However, because mercury moves very slowly through watersheds, it will take a long time before societal efforts to reduce mercury use pay major environmental dividends. The Advisory Group does not recommend including mercury pollution as a priority issue but does recommend MECP continue to track levels in fish tissue, and in the fur of fish-eating mammals such as otters.

There is a growing body of literature on water pollution from pharmaceuticals. In populated areas of the world, levels of common antibiotics, cardiovascular drugs, painkillers, contrast media and antiepileptic drugs are now found in receiving waters at levels toxic to aquatic biota, because of large rates of consumption of these drugs and their disposal via sewage in rivers.

The recent banning of the cosmetic use of several herbicides rapidly reduced their levels in Ontario streams – a clear environmental win. One herbicide that does warrant ongoing scrutiny in Muskoka is glyphosate. Glyphosate is used in Ontario to "manage" trees along hydro corridors to reduce power outages linked to storm-downed trees, and by the MNRF to select for preferred trees by killing less desired species. It would be worth reviewing what aquatic and soil concentrations of glyphosate would accompany treatment of forest blocks or power corridors, the fate and transport of glyphosate in ecosystems, its toxicity to aquatic biota, and the relevance of the toxicology methods employed in these studies to Muskoka-type lakes.

There are many other specific contaminants which could be dumped into the contaminant "bin" for consideration. Much in the news in the last few years has been reported on fluoride, engineered nano-materials, micro-plastics, and neonicotinoid pesticides. At the moment, we have little to no evidence these pose current problems in Muskoka, but some could in the near future. We should keep watch, and potentially encourage the MECP to gather some baseline data on current levels of these potential future threats.

Phosphorus (P): Canadian research has been critical to proving the primary cause for lake eutrophication is phosphorus (P), not carbon or nitrogen supply. It is P supply that limits the growth of algae in our lakes. Dramatic increases of P lead to excessive offshore and nearshore algal growth, and subsequent decreases in P inputs also rapidly lead to water quality improvements. Locally, Muskoka Bay of Lake Muskoka witnessed this sequence. This knowledge of the main cause and proven solution to lake eutrophication resulted in diverse ongoing efforts around the world to reduce anthropogenic inputs of P to lakes. Efforts have included banning phosphates from detergents, better management of diffuse loading from agricultural sources, the addition of tertiary treatment to remove P from waste water during sewage treatment, and, in Muskoka, better maintenance and inspections of septic systems around the lakes, plus limiting development pressures on them. These efforts have largely been successful, evidenced by stable or declining P levels in the majority of Muskoka lakes.

Despite these successes, there are four current concerns about P. The steps that have worked must be continued, as P inputs would rise again if management of septic systems and maintenance of tertiary treatment processes wasn't ongoing. Secondly, as more people move to Muskoka, land use planning and wastewater treatment infrastructure must ensure P inputs rates to lakes do not again increase. Thirdly, the capacity of natural infrastructure that captures and retains P should be considered when planning for development (e.g., healthy forests and vegetated riparian zones "clean" phosphorus from precipitation before it enters streams or lakes). And finally, it appears that climate change is producing conditions in lakes that might lead to hazardous algal blooms (HABs) at concentrations of P that would not historically have produced blooms (see next section).

Several local residents argued continued or perhaps improved oversight of development and land use plans was needed to ensure the low-nutrient character of our lakes. Those concerns do appear justified to the Advisory Group.

Hazardous Algal Blooms (HABs): HABs are common in both oceans and some freshwater systems. In oceans, excessive nutrient inputs commonly produce toxic red tides of marine algae called dinoflagellates. In lakes, the primary culprits are certain strains of Cyanobacteria, commonly called blue-green algae, that plague lakes around the world when supplies of phosphorus are excessive. Phosphorus is the element in shortest supply in the water, so increasing its availability increases the biomass of algae. When enough P is present, nitrogen (N) becomes limiting to further algal growth, then the blue-greens rise to dominance as only they can literally suck N out of the air. The science behind this understanding was pretty well settled a few decades ago, and it has stood the test of time on many occasions as reducing P inputs to lakes has reduced symptoms of eutrophication and dramatically reduced the incidence of blue-green blooms in lakes, including in Muskoka. However, something odd is happening in Ontario's lakes and inland waters. Despite stable or falling concentrations of P, the incidence and frequency of algal blooms has been increasing again, and blooms are now cropping up not just in more P-rich lakes, but in nutrient-poor lakes that scientists would not have deemed vulnerable to algal blooms. Blooms have appeared in completely undeveloped lakes, such in Dickson Lake in Algonquin Park.

While the underlying mechanisms of HAB formation may be unclear, the impacts are well known. Lake waters may be undrinkable during HABs and there is clear evidence property values are depressed in lakes during HABs, or in lakes known to be vulnerable to such blooms. The Advisory Group thinks research is needed to clearly identify the mechanism of HAB production in low-P waters during a time of climate change, perhaps culminating in research on mitigative interventions that could prevent the initiation of the blooms.

Concluding thoughts on water quality issues in Muskoka: Past scientific research on Muskoka lakes has changed the ways problems in lakes are understood and managed around the world. Muskoka science has contributed to the documentation and diagnosis of the causes of lake eutrophication and lake acidification, respectively, excessive phosphorus input and SO2 from fossil fuel combustion. This understanding contributed directly to the successful management of these lake problems in Ontario, and subsequent monitoring in Muskoka has proven the efficacy of management interventions suggested by the research. Muskoka-based research has also made contributions of international significance to the understanding of diverse lake problems, including mercury pollution, climate change, the invading spiny water flea, climate change, calcium decline and excessive use of road salt. Thus, what has been learned in Muskoka has benefited other freshwater resources in the Muskoka River Watershed, and has been of use around the province and the world. Without four scientific services provided by Muskoka lake scientists – ongoing monitoring to detect problems or threats, diagnosis of their causes, evaluation of possible remedial interventions, and tests of their efficacy – the use and appreciation of many lakes would have suffered, dragging down our economy in the process. The MWI provides a unique opportunity to continue learning how to best protect water resources and, hopefully even improving on the strategies that have been followed in the past.

Existing and emerging threats to natural habitat and biodiversity

The Muskoka Watershed is in Ontario Shield Ecozone, Ecoregion 5E (Georgian Bay Ecoregion)(MNR 2009). This region is rich in natural resources and biodiversity which are key to ensuring a healthy environment, strong communities and a thriving economy.

Habitat and biodiversity were prominent in all outreach and research of the Advisory Group. They are also inter-connected with virtually all other issues facing the Muskoka River Watershed. As identified in the Water Quality Issues section of this report, current threats to freshwater ecosystems include changes to habitat and biodiversity, climate change, invading species and cumulative stressors. After extensive discussion and analysis of the issues, the Advisory Group identified the following existing and emerging threats to natural habitat and biodiversity issues, the loss of natural assets:

- Erosion

- Climate change

- Fragmentation, loss of corridors

- Invading species

- Land use

- Loss of biodiversity

- Loss of forest health

- Threatened species

- Wetland loss

This list is inclusive of the input from the community and subject matter experts but the Advisory Group understands it is not comprehensive and restoration and protection efforts as well as new and emerging threats will impact the issues and priorities.

Natural habitat, the land, forest, wetland, rock barrens, grassland, and water (lakes and streams) make up Muskoka's ecosystem. These features are part of the region's critical natural infrastructure and our natural capital. They not only provide multiple benefits to the birds, fish, plants and animals that depend on them, they are individually and in combination intrinsically linked to many of the issues and opportunities facing the Muskoka Watershed.

Biodiversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth, from the tiniest microbe to the vast northern forests. Biodiversity is essential to sustaining the living systems we depend on for our health, economy, food and other vital services.

All of the features associated with natural habitat and biodiversity provide extensive and complex ecosystem services, at no cost to society.

The eight issues of watershed habitat and biodiversity

While climate change and land use (housing, infrastructure, recreation, dams, etc.) are key factors influencing habitat and biodiversity, major threats in Muskoka are wetland loss, loss of forest health, presence of invading species, threatened species, erosion, fragmentation and loss of corridors, loss of stream networks and loss of biodiversity.

The 2015 State of Ontario's Biodiversity report

Invasive Species: Invasive species can be any kind of living organism that is not native to an ecosystem and causes harm. They can be terrestrial or aquatic, include insects and algae, and harm the environment, the economy, or even human health. When combined with other issues and threats such as habitat loss and climate change, invasive species accelerate the loss of biodiversity. Their spread can negatively impact property values, the ability for people to access and safely use waterways and trails, and some pose significant human health concerns (e.g. Giant Hogweed).

According to the Ontario Invasive Species Centre the potential costs to agriculture, fisheries, forests, healthcare, tourism, and the recreation industry from invasive species are estimated to be $3.6 billion per year in Ontario. Species currently causing the most significant impact around the province include emerald ash borer, zebra and quagga mussels, round goby, gypsy moth, and invasive plants such as Phragmites and wild parsnip, which combined cost almost $20M to manage. These expenses will continue to increase if more invasive species are able to establish and spread in Ontario and Muskoka. Proactive measures to prevent the introduction of invasive species to a new area and controlling them when they are at manageable levels are the best options both financially and ecologically.

Forest Health: Forests, the "Earth's Lungs," are critical to providing and maintaining clean air and water and to the hydrological cycle, erosion control and moderating temperature. Impacts on forests include loss from harvesting, removal for development, storm and drought impacts (climate change) and the impact of calcium loss.

Species at Risk: The Muskoka River Watershed provides habitat for a relatively large number of species that are becoming rare, partially due to habitat loss. Management of habitat for threatened and endangered species has become important across Ontario and is being included in considerations of habitat protection and management.

Wetland Loss: Wetlands, the "Earth's Kidneys," filter water, absorbing nutrients and contaminants, store carbon and play a role in climate change mitigation and adaptation. Wetlands are also critical in managing flooding and drought and their loss contributes to greater floods and risks to water quality in the Muskoka lakes. Wetlands are the "gems" of green infrastructure.

Wetlands in Ontario are under threat and being lost or severely degraded and the health of those that remain is threatened.

Fragmentation, loss of corridors: Large blocks of contiguous forest, major corridors and connections are all critical to the health of forests, provision of wildlife habitat, and the maintenance of critical ecological services. Ongoing land use change is threatening habitat and biodiversity through fragmentation and loss of connections and corridors through the Watershed.

Loss of biodiversity: Loss of biodiversity will be driven by habitat loss, climate change, invasive species, and water quality and quantity change. The Muskoka River Watershed is blessed with biodiversity but continued anthropogenic pressure can erode its healthy state. During outreach, the agriculture community raised a concern around competing land pressure. They felt part of the issue is the outdated agriculture land classification mapping for Muskoka. Many types of agriculture production including pasture and forage production are critical to local biodiversity, providing habitat for many species including species at risk (e.g. Bobolink). Producers are not able to compete with development land prices including green energy projects like solar energy.

Erosion: Erosion is a natural process as climate influences the ways in which streams and landscapes evolve through time. However, as a result of climate change and ongoing land use practices (including water management, shoreline development, etc.), erosion is degrading habitats (primarily lakeshore and riverbanks) in key locations throughout the Watershed. If not mitigated and included in new land use practices, erosion will likely lead to significant property damage in certain areas (e.g. Muskoka River downstream of Bracebridge, the shoreline of Mary Lake).

Concluding thoughts on habitat and biodiversity

It is important to set targets, to know what currently exists and what extent of landscape cover by natural assets like wetlands and forests is ideal for a healthy, vital, sustainable biodiversity. For example, identifying local and regional "habitat mosaics" is referred to as critical in 'How Much Disturbance is too Much?: Habitat Conservation Guidance for the Southern Canadian Shield' (Environment Canada).

Natural capital refers to the stocks of water, land, air, and renewable and non-renewable resources (such as plant and animal species, forests, air, water, soils and minerals) which alone or combined yield or provide a flow of goods and services, benefits to humans and other species. The collective benefits provided by the resources and processes supplied by natural capital are referred to as ecosystem goods and services, or ecosystem services. These services are imperative for human health and well-being, as well as the health of Ontario's economy. The opportunity is now in the Muskoka River Watershed to show leadership in protecting the critical natural habitat and biodiversity and the associated ecosystem upon which the health of the community and economy rely.

Governance and communications

Watershed governance in Muskoka is not an issue of a lack of governance but rather one of too many governors. There is not one body providing comprehensive oversight. The Muskoka River Watershed does not have a conservation authority and does not even lie entirely within the District Municipality of Muskoka. The fragmented nature of governance in the Watershed has repercussions for both management and communications. Water, natural assets and species don't "see" municipal or political boundaries, they exist within the watershed context. A frequent comment heard by the Advisory Group centred on inadequacy of communication about how and why watershed management decisions are made and a lack of information about what is being done to address concerns of the public. Plans need to be made and implemented at the Watershed-level and include the requisite coordination between agencies and communications with the public.

Within Muskoka, the Province, the District and area municipalities each have some responsibility for the most important key elements of the region: the environment, infrastructure, natural resources and land use planning. The federal government also has overlapping responsibilities in related areas.

At the municipal level, there are considerable differences in the interpretation and application of the broad Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) which offers direction at the provincial level and provides the framework for municipal planning. Within the Watershed, in addition to the District Municipality of Muskoka, there are 13 lower tier municipalities plus the County of Haliburton.

MNRF is responsible for flood monitoring, control and warning. The municipalities are responsible for hazardous areas but the 13 lower tier municipalities, each with a different Official Plan, control what is acceptable construction within a hazardous area. Flood plain mapping was updated in 2019 within a portion of the Watershed that lies within the District of Muskoka and municipal Official Plans have yet to be updated accordingly to determine the future of development or redevelopment in identified flood plains. There is no coordinating body addressing the need for prevention and mitigation of future floods and ensuring risk to infrastructure and human safety is minimized.

Governance issues in the Watershed are not limited to flooding. Stormwater management, wetland protection, agricultural land protection, shoreline and infill development, invasive species, endangered species, forest health, economic development and infrastructure are all governed by different silos of responsibility and accountability with no overarching plan to address the issues on a watershed basis which is the way in which the ecosystem operates.

Wetlands are and will be increasingly important to the Watershed as potential attenuators of flood waters, ongoing purifiers of fresh water, and habitat for the protection of the biodiversity. The protection, or seeming lack thereof, of wetlands and biodiversity was brought forward in many listening sessions. The PPS does restrict development in or near Provincially significant wetlands but nothing triggers the prevention of infilling prior to a development proposal. Levels of acceptability of practices vary according to the lower tier municipality whether within or outside the District of Muskoka.

Agricultural community representatives identified the need for a watershed focus for the Muskoka Watershed Initiative. The lack of comprehensive soil mapping used to designate agriculture land classification was highlighted. There is no governance body to either finance or undertake such mapping, even District-wide much less Watershed-wide.

As part of creating an awareness of watershed issues, informing the general public and providing a source of information, there is a need for a clear communication strategy. As an example, during flood events MNRF issues the watch and warning messages for the general area, but it is up to the municipalities to ensure they are interpreted and communicated to residents. There is an urgent need for coordinated messaging, which a singular governance body could better manage.

In addition to the municipalities, these issues of concern are made even more complex by the number of responsible authorities – MECP over environmental assessments, MNRF over Crown Land and the land under the waterways as well as fish habitat and flood reports, the Ministry of Transportation (MTO) over major highways crossing, Environment Canada providing weather reports on which the airport and others rely, the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (MMAH) over municipal management affairs, and the Ministry of Infrastructure (MOI) over infrastructure requirements. All operate independently and communicate on a geopolitical basis, not a watershed basis.