American Badger Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the American badger, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA, 2007 outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA, 2007. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Ontario American Badger Recovery Team. 2010. Recovery strategy for the American Badger (Taxidea taxus) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 27 pp.

Cover illustration: iStockPhoto.com

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2010

ISBN 978-1-4435-0905-3 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Authors

Bernt Solymár, EarthTramper Consulting Inc.

Ron Gould, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Acknowledgements

A badger working group was initiated in Norfolk County in 2001. Members of that group, including Ron Gould (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources), Mary Gartshore and Peter Carson (Norfolk Field Naturalists) and Bernt Solymár (EarthTramper Consulting Inc.), had significant input into the drafting of this strategy. The Ontario American Badger Recovery Team was formalized in 2003 and has been a significant contributor of information to badger study and development of this recovery strategy.

Thanks also go to the following: the American Badger (Taxidea taxus jeffersonii) Recovery Team in British Columbia for technical comments and background information on their projects; Donald Sutherland of the Natural Heritage Information Centre for supplying a historical database of badger records in Ontario; Jeff Bowman, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, for collecting DNA samples for analysis and providing sampling equipment for hair and tissue samples; Sarah Weber for her thorough copy edit of the strategy; and the rural landowners, trappers and members of the public who have contributed to the conservation and recovery of the species by providing information on badger sightings. Funding for initial public outreach, press releases, "Information Wanted!" posters and the drafting of this paper was made possible through the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk Program (2002–04).

Declaration

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has led the development of this recovery strategy for the American Badger in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario

Executive summary

The American Badger (Taxidea taxus jacksoni), a subspecies associated with tallgrass prairie and mixed grassland habitat of the Great Lakes region, is one of three badger subspecies found in Canada. It is present in southwestern Ontario, mainly along the north shore of Lake Erie, and a second, presumably smaller, population occurs in the very northwestern portion of the province, adjacent to the Minnesota border. The Ontario breeding population is thought to consist of fewer than 200 individuals.

In 1979, the American Badger was listed as not at risk in Canada. In 2000, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) redefined the Canadian badger population to include three subspecies: T. t. taxus in the Prairie provinces, T. t. jeffersonii in the southern interior of British Columbia and T. t. jacksoni in Ontario. Additionally, COSEWIC upgraded the status of the jeffersonii and jacksoni subspecies of the American Badger to endangered. In 2004, T. t. jacksoni was added to the Species at Risk in Ontario List as endangered – not regulated. When this list was regulated in 2008, the subspecies was removed from the species name.

Little research or monitoring has been conducted on the Ontario populations of the American Badger. As a result, many knowledge gaps exist with regard to the abundance, distribution and population trends of this species, as well as its behaviour, habitat requirements, prey species, mortality factors and ecological role. In response, a badger working group was formed in 2001 to look at collecting some preliminary data on the badger in Norfolk County, an area of concentrated activity for the species in the province. A public awareness campaign and request for information led to several dozen new sighting records and specimens. This campaign helped lay the foundation for the formation of the Ontario American Badger Recovery Team.

The goal of this recovery strategy is to achieve reproductively sustainable and secure populations of the American Badger throughout its current range in southern and northwestern Ontario over the next 20 years. To accomplish this, several recovery objectives must be met:

- Fill knowledge gaps on American Badger ecology, behaviour, distribution, movement, dispersal, population dynamics, mortality factors and habitat use in the species' Ontario range.

- Increase public awareness of and appreciation for the badger and its ecological role in grassland and agricultural ecosystems.

- Reduce human-related threats.

- Quantify habitat suitability for the application of habitat modelling and protection mechanisms.

This recovery strategy recommends that specific research, monitoring and habitat stewardship activities, as well as public outreach and education activities, be conducted over the next five years to gain a better understanding of the American Badger and its requirements so as to be able to recover the species in Ontario. Owing to the persistence of reproductive individuals in suitable but fragmented habitat within Ontario and demonstrated habitat restoration techniques, it has been determined that recovery of the American Badger in Ontario is feasible.

Considering the functions and significance of dens to badgers as residences, as well as the importance of available prey in proximity to them, this recovery strategy recommends that American Badger dens and areas identified as foraging habitat in proximity to a den be considered for protection in a habitat regulation.

1. Background information

1.1 Species Assessment and Classification

Common name: American Badger

Scientific name: Taxidea taxus

SARO List Classification: Endangered

SARO List History: Taxidea taxus – Endangered (2008)

t. jacksoni – Endangered – Not Regulated (2004)

COSEWIC Assessment History: T. t. jacksoni – Endangered (2000)

SARA Schedule 1: T. t. jacksoni – Endangered (June 5, 2003)

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5

NRANK: N4

SRANK: S2

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

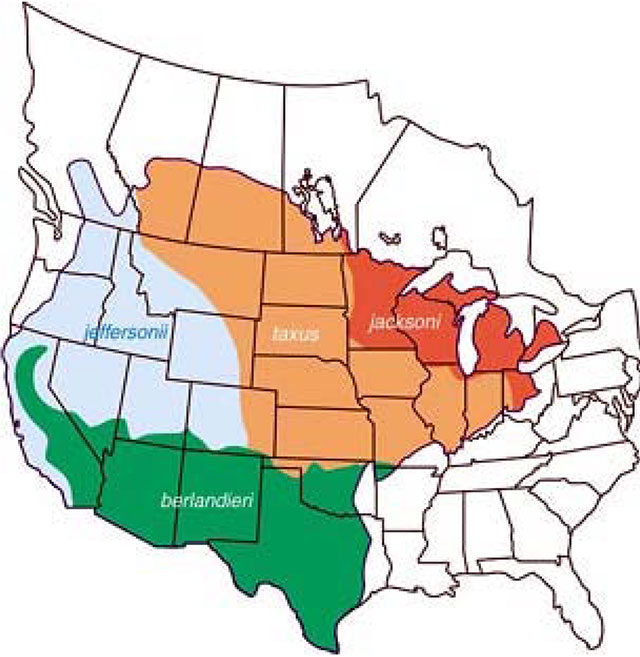

1.2 Species description

The American Badger (Taxidea taxus) is a mid-sized carnivorous mammal in the Mustelidae, or weasel, family. Badgers are grey with black and white stripes on the face and head. They are very muscular and have powerful jaws for killing and consuming prey. The badger uses its long claws, which are easily visible on the front feet, for digging and moving soil. The four recognized subspecies differ mainly in their fur colour, size and geographical range (Newhouse and Kinley 1999, adapted from Hall 1981 and Long 1972) (see figure 1). Individuals of the jacksoni subspecies are typically smaller (body weight of 7–11 kilograms) than the taxus subspecies known from the Prairie provinces (Shantz 1953). Aside from being slightly smaller and having a tawny underside, the jacksoni subspecies looks very similar to other subspecies of badger in North America (Long 1972). Geographic range and resultant differences in prey species are the most significant differences observed among the American Badger subspecies.

American Badger jacksoni is the only subspecies of badger found in Ontario. Throughout the remainder of the recovery strategy, "American Badger" refers to the jacksoni subspecies, unless stated otherwise.

1.3 Distribution, population size and trends

The four subspecies of American Badger are widely distributed in North America. Collectively, their range extends from southern Alberta south to Mexico and from the Pacific coast to Ontario and the Great Lakes states. The range of each subspecies is depicted in figure 1 and described below:

- T. t. taxus occurs from western Ohio, Indiana and Missouri to eastern Colorado, Wyoming and Montana and north to the Prairie provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba).

- T. t. jeffersonii occurs in Colorado, Wyoming and Montana to southern British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and parts of California.

- T. t. jacksoni occurs from Ohio and western Ontario to Michigan, northern Illinois and Indiana, Wisconsin and Minnesota.

- T. t. berlandieri occurs from Oklahoma and Texas to the northern Sierra Nevada and south into Mexico.

There is thought to be significant overlap in the ranges of subspecies, with intermediate forms occurring in the areas of overlap.

Figure 1. Approximate ranges of the four American Badger subspecies in North America

Source: Newhouse and Kinley 1999

The range of the endangered American Badger jacksoni subspecies includes the geographic area around southern and western Lake Superior, Lake Huron and Lake Erie, on both sides of the Canada–United States border. The subspecies is present throughout the states of Minnesota (J. Erb, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, pers. comm. 2004) and Wisconsin (Rigney 1999) and parts of Illinois (Warner and Ver Steeg 1995) and Indiana, where expansions have been facilitated by forest clearcutting for agriculture and mining (Gremillion-Smith 1985). Badgers have been recorded in all northern counties and in 52 of 68 southern counties of Michigan (Baker 1983) and in the western 23 counties of Ohio (Ohio Historical Society 2005). The range of the American Badger jacksoni subspecies is believed to be closely associated with the pre-settlement range of tallgrass prairie habitats surrounding the Great Lakes region. The American Badger has a provincial rank of S2 (imperilled) in Ontario and a global rank of G5 (secure), as determined by NatureServe (2009); however, specific ranks have not been developed for the jacksoni subspecies.

The jacksoni subspecies of the American Badger is at its northern range limit in Ontario and is isolated from neighbouring populations by the Great Lakes, by the St. Clair and Detroit rivers, and possibly by intensive development and habitat loss along potential corridors. Peripheral populations at the range limit for the subspecies are believed to exhibit lower genetic diversity. This is due in part to the smaller size and density of the population and to isolation from the core population (Lesica and Allendorf 1995). Lower genetic diversity can result in greater risks to population viability and greater fluctuations in population numbers.

Accurate assessments of the abundance of the jacksoni subspecies population are not available. Newhouse and Kinley (1999), however, estimated that fewer than 200 individuals are present in Ontario. In southern Indiana and Illinois, badger populations have expanded their range, and numbers seem to be slowly increasing. The jacksoni subspecies is probably present in the northern parts of these states, and the taxus subspecies is distributed in the southern portions, where most expansion seems to be occurring. In northern Illinois, jacksoni populations are declining (Warner and Ver Steeg 1995). In Wisconsin and Michigan, numbers are thought to be low (Baker 1983), and in Ohio, the jacksoni subspecies is considered rare and its current number of individuals is unknown (Ohio Historical Society 2005). In Wisconsin, Jackson (1961) estimated the badger population to be 5,000 to 20,000 individuals, but he did not identify the subspecies.

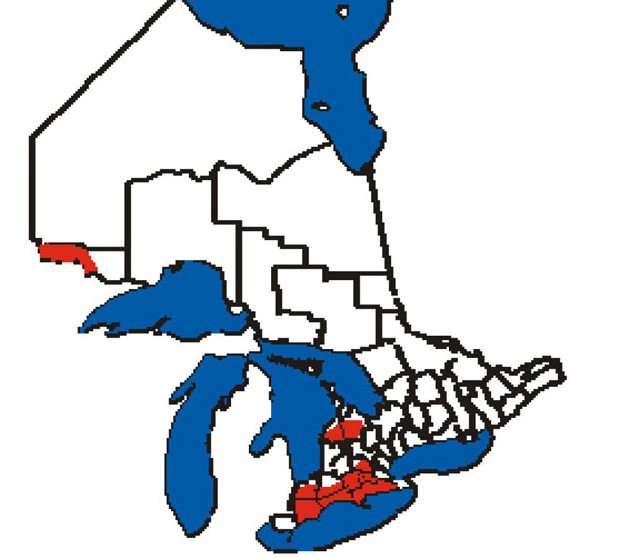

The American Badger jacksoni subspecies is present in Canada in southwestern Ontario, primarily along the north shore of Lake Erie, and a second, presumably smaller population is present in northwestern Ontario, adjacent to the Minnesota border (Stardom 1979, Dobbyn 1994) (see figure 2). There is evidence of reproduction among both regional populations (Ontario American Badger Recovery Team 2008, Skitt and Van den Broeck 2004). Records are sparse at best throughout the range of this species. Jacksoni individuals may occasionally disperse into Manitoba, but no reports or literature indicate that the subspecies is extant there.

Figure 2. Range of the American Badger in Ontario

Source: Royal Ontario Museum 2006 (modified from Newhouse and Kinley 1999)

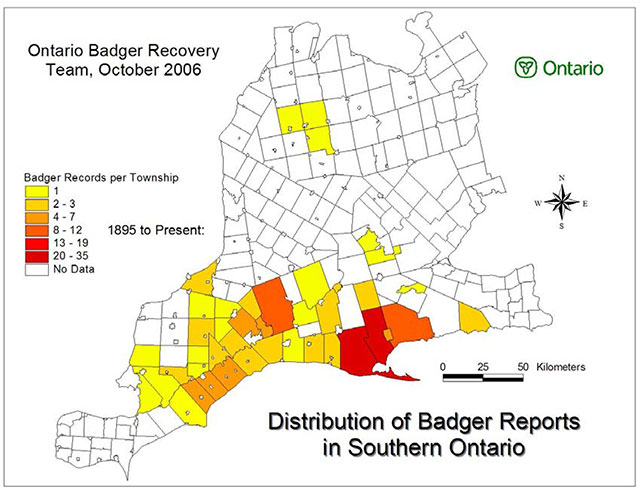

Knowledge of historical patterns in the distribution and abundance of the American Badger in Ontario is limited and based on a relatively small number of confirmed reports across a large geographic range. The first known account was from near Grand Bend in north Lambton County in 1895 (NatureServe 2009). From 1980 to the present, there have been nearly 60 reports from both Norfolk and Middlesex counties, with occasional (fewer than six) reports of sightings in the following counties: Kent, Lambton, Oxford, Haldimand, Grey, Bruce, and Rainy River (see figure 3). Table 1 provides a summary of confirmed sightings up to 2008.

Lintack and Voigt (1983) suggested that extralimital records of male badgers found in Waterloo and Grey counties may be of badgers that have dispersed from more southern areas of Ontario. Messick and Hornocker (1981) reported that young badgers in Idaho can disperse for distances of up to 110 kilometres in their first summer, so it is possible that some outlier records found in Ontario could be a result of dispersing juveniles. Newhouse and Kinley (1999) suggested that the southern Ontario population is disjunct from other Canadian and U.S. populations and "almost certainly exists as an 'island' population." More study is needed to determine whether the only Canadian range of this species is in Ontario and, if several populations do exist, to determine the genetic relationship among them to ascertain the presence of a functional metapopulation.

Changes to the range of the species in Ontario are not well understood. The recovery team has compiled a list of 144 confirmed reports in Ontario between 1895 and 2008. Information available in Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) database indicates that the American Badger was historically present in some counties in Ontario where the species has not since been confirmed. These include Bruce, Huron, Kent and Elgin counties (NatureServe 2009). More recent outreach and monitoring, however, have indicated that the species occurs in other areas such as Thunder Bay in northwestern Ontario and Wentworth, Brant and Oxford counties in the south. It is not yet known whether this represents a change in distribution of the species or whether these differences are a result of variability of monitoring and reporting.

Figure 3. Distribution of American Badger observations in southern Ontario to 2006

Table 1. Summary of confirmed sighting records of the American Badger in Ontario

| County | Number of sightings pre-1970 | Number of sightings 1970–1979 | Number of sightings 1980–1989 | Number of sightings 1990–1999 | Number of sightings 2000–2008 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenora/ Dryden | 1 | 1 | |||

| Rainy River to Fort Frances | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Thunder Bay | 1 | ||||

| Grey | 1 | 1 | |||

| Bruce | 1 | ||||

| Huron | 1 | 1 | |||

| Lambton | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Middlesex | 1 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Kent | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| Elgin | 4 | 6 | |||

| Oxford | 2 | 3 | |||

| Norfolk | 2 | 10 | 17 | 10 | 17 |

| Haldimand | 1 | 1 | |||

| Waterloo | 1 | 1 | |||

| Brant | 4 | ||||

| Wentworth | 1 | ||||

| Northumberland | 1 |

In Ontario, the American Badger seems, on the basis of recent sightings, to be concentrated in several counties. A small population in northwestern Ontario has produced consistent reports, mostly occurring between Rainy River and Fort Frances (Skitt and Van den Broeck 2004), with a probable source being adjacent northern Minnesota, which seems to exhibit a healthy, sustainable population.

COSEWIC has estimated that there are probably fewer than 200 individual American Badgers in Ontario. They are most numerous in the Great Lakes forest region (southwestern Ontario), with small outlier populations possible in northwestern Ontario and the very southeastern corner of Manitoba (Newhouse and Kinley 1999), although researchers from Manitoba have indicated that a population of the jacksoni subspecies is unlikely to be present in that province. Since 2001, a number of confirmed live sightings and roadkilled specimens in southern Ontario, including adults and young, suggest that a small but reproducing population is present in the province.

Given existing information, the Ontario populations of the American Badger probably constitute less than 5 percent of the total jacksoni distribution.

1.4 Needs of the American Badger

1.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

The American Badger requires areas of habitat large enough to sustain sufficiently large prey populations. Preferred areas include natural and undisturbed grasslands, shrubby areas and woodlots (Baker 1983). Historically, the jacksoni subspecies probably inhabited large tracts of tallgrass prairie and oak savanna across its range in the northern midwestern United States and around the Great Lakes. Today, it is also associated with old fields, pastureland, the edges of agricultural fields and orchards, scrubland, wooded ravines and woodlots (Baker 1983, Messick 1987).

In Ontario, it is believed that the Woodchuck (Marmota monax), also known regionally as the Groundhog, and the Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) are the major prey items of badgers (Dobbyn 1994). From investigation of badger diggings in southern Ontario, there is also evidence that badgers occasionally prey on Meadow Vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and mice (Peromyscus spp.) Ontario American Badger Recovery Team 2008). Anecdotal observations by farmers, naturalists and hunters suggest that populations of groundhogs have declined dramatically in southwestern Ontario over the last decade. If substantiated, this trend could have negative effects on badger population densities in the province. In northwestern Ontario, badgers may also prey on Franklin’s Ground Squirrel (Spermophilus franklinii), where the ranges of both species overlap west of the Fort Frances area (Skitt and Van den Broeck 2004).

Being fossorial or burrowing mammals, badgers require sandy or other friable soils in which to create dens for resting, rearing young and overwintering. Soils should be coarse enough to resist collapse when wet (Apps et al. 2001) but contain enough organic matter and be sufficiently adhesive to prevent collapse under dry conditions (such as would be the case with pure sands).

Badgers are not true hibernators but overwinter in a state of torpor, remaining largely inactive through much of the winter, but becoming active and foraging during suitable weather. Badgers are promiscuous breeders; males often breed with multiple females within a home range. Home range sizes can vary widely, probably due to variations in habitat (Newhouse and Kinley 1999). Owing to fragmentation of habitats in southern Ontario, old fields, hedgerows and woodland edges appear to be important habitats for maternal and other den sites and as migration corridors for the dispersal of young

1.4.2 Ecological role

As an upper trophic carnivore in its Ontario range, the badger’s ecological role in the landscape is still not well understood. The fossorial habits of badgers may have important local ecological functions. Badgers create patch disturbances in tallgrass prairie and other grassland habitats, which can alter plant communities and loosen soil (Collins and Gibson 1990). Badger diggings help to aerate soil, promote the formation of humus and allow water to reach deeper soil levels quickly (Messick 1987, Newhouse and Kinley 1999). Other fossorial mammals use badger holes for shelter and nesting. For example, in Alberta, Burrowing Owls (Athene cunicularia), Pocket Gophers (Thomomys spp.) and snakes sometimes use badger holes (Scobie 2002). To what extent other fossorial species use or rely on badger burrows in Ontario is not known.

1.5 Limiting factors

Low population density and large home range

Home ranges for badgers are generally large, ranging in size from 240 to 850 hectares (ha) (Sargeant and Warner 1972, Long 1973, Messick and Hornocker 1981, Lindzey 1982), and are largely dependent on food density, season and social structure (Lindzey 1987). Other literature indicates that home ranges may be up to 500 square kilometres (i.e., 50,000 ha) in size in areas where habitat or prey availability is poor (Lindzey 1987). Minta (1993) showed that the number of females influences male home range size – where female numbers are high, males need not range far for breeding opportunities – and that female home range size is limited exclusively by food availability. Low prey densities and/or low population densities may lead to increased foraging distance (particularly for females) and consequently may result in an elevated risk of road mortality. This risk is especially high in southwestern Ontario, where rural road density and traffic volumes are high.

Another conservation implication of these large home ranges is that multiple observations of one individual over a large area may be mistakenly assumed to be observations of many badgers. This could easily lead to overestimates of population size (Newhouse and Kinley 1999).

Biological and behavioural factors

The B.C. recovery team (Jeffersonii Badger Recovery Team 2008) lists the following reproductive capacity factors as possibly limiting population recovery:

- Badgers may be prone to factors limiting the population recovery of other mustelids, such as low reproductive capacity (Ruggiero et al. 1994, Rahme et al. 1995,Weaver et al. 1996). Females can start breeding in their first season; the proportion that does so is estimated to be between 30 and 50 percent (Messick and Hornocker 1981). Males do not mature sexually until they are over one year old (Messick 1987). The extent to which younger males contribute to successful reproduction at the population level is not known, but it is thought to be limited.

- Female badgers are capable of producing a litter annually, but data from British Columbia suggest that this is rare.

- Female badgers are believed to be induced ovulators and successful fertilization may require multiple copulations (Messick and Hornocker 1981, Minta 1993). Females also exhibit delayed implantation, which is probably influenced by prey availability. During periods of depressed prey availability, female badgers may not breed or implantation may be suspended. If breeding opportunities are limited by low densities (and hence reduced encounters) and food sources are unreliable, overall reproductive output at the population level will be limited.

In Ontario, the recovery team believes that the nomadic behaviour of badgers in search of prey and mates, and their affinity for nocturnal migration within large home ranges also represent limiting factors, by increasing the risk of road mortality. Owing to the fossorial nature of badgers and their related dependence on suitable soils to provide burrowing opportunities, the presence of sandy deposits is also an important consideration that may limit the range of the species. The presence of deep, sandy soils is probably of significant importance for the creation of larger dens used for rearing of young. The majority of reported badger occurrences in Ontario have been from the sand plains of Norfolk, Middlesex, Kent, Elgin and Brant counties.

1.6 Threats

Table 2. Threat classification for American Badger in Ontario

1 Habitat Loss: Threat and threat information

| Threat Category | General Threat | Specific Threat | Stress | Extent | Local Occurrence | Range Wide Occurrence | Local Frequency | Range Wide Frequency | Local Causal Certainty | Range-wide Causal Certainty | Local Severity | Range-wide Severity | Local Level of Concern | Range-wide Level of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat loss or degradation | Loss of grasslands, related soils and prey availability to agriculture or other development | Fragmentation of habitat; habitat conversion; behavioural disruption; isolation | Reduced population size or viability | Widespread | Current | Current | Continuous | Continuous | High | High | High | High | High | High |

2 Road mortality: Threat and threat information

| Threat Category | General Threat | Specific Threat | Stress | Extent | Local Occurrence | Range Wide Occurrence | Local Frequency | Range Wide Frequency | Local Causal Certainty | Range-wide Causal Certainty | Local Severity | Range-wide Severity | Local Level of Concern | Range-wide Level of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accidental mortality | Road mortality | Vehicles colliding with badgers | Reduced population | Widespread | Current | Current | Continuous | Continuous | Medium | Medium | Moderate-High | Moderate-High | Medium-High | Medium-High |

3 Predation: Threat and threat information

| Threat Category | General Threat | Specific Threat | Stress | Extent | Local Occurrence | Range Wide Occurrence | Local Frequency | Range Wide Frequency | Local Causal Certainty | Range-wide Causal Certainty | Local Severity | Range-wide Severity | Local Level of Concern | Range-wide Level of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural processes or activities | Predation | Predation by coyotes and domestic dogs | Reduced population size; increased mortality | Widespread | Current | Current | Recurring | Recurring | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low | Low |

4 Killing and persecution: Threat and threat information

| Threat Category | General Threat | Specific Threat | Stress | Extent | Local Occurrence | Range Wide Occurrence | Local Frequency | Range Wide Frequency | Local Causal Certainty | Range-wide Causal Certainty | Local Severity | Range-wide Severity | Local Level of Concern | Range-wide Level of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disturbance or persecution | Discriminate killing | Reduced population size; increased mortality | Widespread | Current | Anticipated | Recurring | Recurring | Moderate | Moderate | Low | Low | Low–Medium | Low–Medium |

5 Incidental trapping: Threat and threat information

| Threat Category | General Threat | Specific Threat | Stress | Extent | Local Occurrence | Range Wide Occurrence | Local Frequency | Range Wide Frequency | Local Causal Certainty | Range-wide Causal Certainty | Local Severity | Range-wide Severity | Local Level of Concern | Range-wide Level of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accidental mortality | Discriminate killing | Capture as nontarget species | Reduced population size; increased mortality | Local | Current | Anticipated | Recurring | Moderate | Low | Low–Medium | Low–Medium |

6 Disease: Threat and threat information

| Threat Category | General Threat | Specific Threat | Stress | Extent | Local Occurrence | Range Wide Occurrence | Local Frequency | Range Wide Frequency | Local Causal Certainty | Range-wide Causal Certainty | Local Severity | Range-wide Severity | Local Level of Concern | Range-wide Level of Concern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural processes or activities | Disease | Canine distemper and tularemia | Reduced population size; increased mortality | Local | Current | Anticipated | Recurring | Unknown–Low | Low | Low | Low |

Loss of native and human-maintained grassland habitats has been extensive throughout the historical range of the American Badger in Ontario. It is estimated that less than 1 percent of Canada’s pre-settlement tallgrass prairie and savannah remain; some of the most significant declines have occurred in Ontario, which once supported more than a thousand square kilometres of tallgrass communities (Delaney et al. 2000). Most remaining grassland habitats are also highly fragmented, a factor that probably forces badgers to maintain larger home ranges in search of prey.

The killing of badgers on roads as they forage and migrate throughout home ranges is a major mortality factor in British Columbia (Jeffersonii Badger Recovery Team 2008). This may be the case in this province as well, given records of vehicular collisions with badgers and reported roadkilled specimens in Ontario. Over 25 percent of badger reports received in Ontario since the mid-1990s have been of roadkilled animals, which suggests that road mortality is a significant threat that could limit badger survival and recovery.

Although badgers are considered upper trophic predators in their southwestern Ontario range, predation of badgers by dogs, although not often documented in Ontario, does occur. Two instances of mortality caused by domestic dogs in southern Ontario have been confirmed, so it is likely that coyote predation also occurs, particularly on young badgers. A study by Ver Steeg and Warner (1999) indicated that predation by coyotes and domestic dogs in Illinois significantly affects juvenile badgers, and that fewer than 70 percent of juveniles survive to dispersal.

Disease is probably another threat to badgers in Ontario, specifically canine distemper, which is known to affect other mustelids, and tularemia, which was found in two necropsied individuals in 2007 (Sadowski and Bowman 2007).

Since 2000, the American Badger is no longer on Ontario’s Furbearers List as a legally targeted species for harvesting, but some incidental trapping of badgers, sometimes in traps set for groundhogs, is still reported. Farmer landowners may also persecute badgers, particularly in areas of livestock forage, where burrowing badgers are not welcome.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Specific research on the American Badger has recently been initiated in Ontario, where records generally are sparse. To implement a sound recovery strategy, current gaps in our knowledge of the species in the province must be addressed:

- What are the current population sizes and distributions of the American Badger in Ontario? Are populations declining, increasing or remaining stable? How many individuals constitute a viable population of this species? Are the current populations genetically sustainable? How does the historical population size and distribution of the American Badger in Ontario compare to the species' current population size and distribution?

- What is the range of individual animals, and how does this relate to the landscape ecology of Ontario and related protection requirements?

- What is the impact of continued habitat loss, including loss through habitat degradation and fragmentation, on badger populations, and what is its potential effect on reproduction and genetic isolation?

- What is the diet of badgers in Ontario, and how adaptable are badgers to changes in prey type or availability? What population density and abundance relationships exist between predator and prey?

- How significantly are threats of road mortality and predation affecting badger populations in the province?

- What is the general attitude of farmers and rural landowners to badgers, and what effect may these attitudes have on recovery efforts?

- How can we best monitor individual badgers? What are the best protocols for observing active dens/burrows and analyzing carcasses, hair and fecal samples?

- What opportunities exist for working with partner organizations to conserve, protect and restore recovery habitat for this species?

1.8 Recovery actions completed or under way

In 1995, the NHIC initiated the task of assembling historical records of the American Badger in Ontario from museum collections, published and unpublished literature, and correspondence with naturalists and members of the general public. The Fur Program (Wildlife Branch, OMNR) has maintained records of badger trappings in the province since 1981. In 2000/01, OMNR implemented a "no quota" approach provincially, which means that there is no allocation for harvesting this species. In 2008, the season was officially closed for American Badger, prohibiting the harvesting of this species.

A badger working group was formed in Norfolk County in 2001. The following January, the working group issued a press release to local media on the status of the badger in the county. The press release included information on the biology of the American Badger and a request for the public to report any historical or recent sightings to the badger working group. Concurrently, it sent a letter and an "Information Wanted!" poster to local taxidermists, veterinarians, trappers, fish and game clubs, naturalist groups and the Norfolk County road works department, asking them to report any sightings or specimens. As a result, over 20 reports (approximately half were sightings within the previous 10 years) and some photographs of dead badgers were submitted, two mounted specimens were located and a pelt was donated. A separate database that the Aylmer District OMNR maintains was initiated to track both confirmed and unconfirmed reports of badgers. This database is periodically integrated with that of the NHIC.

After the demonstrated success of the Norfolk County poster, OMNR developed and distributed an American Badger information and reporting fact sheet across southern Ontario in 2005, which resulted in additional reports of historical and recent sightings. Concurrently, a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation titled "The Status and Significance of American Badgers in Ontario" was developed for outreach use. It has been presented to naturalist, stewardship and conservation groups across southern Ontario and has elicited additional sighting reports. Several local media interviews and a province-wide OMNR news release have helped to keep the badger monitoring efforts in the public eye. Media attention will continue to be an important asset to badger reporting initiatives and resulting population data for status estimates. Over two-thirds of the reports from Norfolk and Middlesex counties received between 1990 and 2003 followed press releases in the local news media asking for information on sightings or specimens, and a presentation to the Woodstock Field Naturalists resulted in additional reports. All reports have been screened to assess their accuracy.

The badger working group evolved into a provincial recovery team for the species in 2003. The Ontario American Badger Recovery Team and OMNR biologists have followed up on recent badger sighting reports to attempt to verify the presence of the animals. At suspected badger burrowing sites, guard hairs have been collected and submitted to OMNR for analysis. OMNR purchased five Camtrakker® wildlife cameras and has placed them at several suspected badger diggings to attempt to attain photographic evidence of badger presence. These camera units have successfully taken photos of badgers in Norfolk and Middlesex counties. One maternal den site, located in Norfolk County in 2006, has been discovered and studied to date.

In 2004, the Fort Frances District OMNR completed a comprehensive rare mammal survey of the area. This survey included distribution of public outreach materials, which resulted in the reporting of an additional six badger observations in the region (Skitt and Van den Broeck 2004).

Necropsy of 10 collected badgers was conducted in partnership with OMNR Wildlife Section in 2007. A variety of biological factors were studied, including general condition, stomach contents and age. The average age of individual badgers sampled was only 1.2 years; one adult male badger from Norfolk County was 7 years old (Sadowski and Bowman 2007).

Aerial surveys were conducted in 2006 and 2007 in areas of Norfolk and Brant counties in an effort to locate and groundtruth potential badger diggings in areas of recent badger reports. The understanding of methodologies for aerial surveys for American Badger and groundtruthing was significantly improved as a result of these efforts and summarized in a report by Sadowski et al. (2007).

Trent University has initiated a badger reporting and research project across the range of the species in Ontario. These efforts have added to local outreach and monitoring, which include a website for public information (Ontario Badgers) and a badger sightings reporting hotline (

2. Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The goal of this recovery strategy is to achieve reproductively sustainable and secure populations of the American Badger throughout its current range in southern and northwestern Ontario over the next 20 years.

Current knowledge gaps prevent a quantitative assessment of what constitutes sustainable and secure populations of this species in Ontario, but studies to fill these gaps and prescribe actions in support of the recovery goal are under way.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 3. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Fill knowledge gaps on American Badger ecology, behaviour, distribution, movement, dispersal, population dynamics, mortality factors and habitat use in the species' Ontario range. |

| 2 | Increase public awareness of and appreciation for the badger and its ecological role in grassland and agricultural ecosystems. |

| 3 | Reduce human-related threats. |

| 4 | Quantify habitat suitability for the application of habitat modelling and protection mechanisms. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 4. Specific approaches to recovery of the American Badger in Ontario

| Priority | Objective Number | Threats Addressed | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Anticipated Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | 1, 2, 3, 4 | All | Document distribution, abundance and movement |

|

|

| Urgent | 1, 4 | All | Research |

Investigate connectivity and relatedness among populations of badgers:

|

|

| Urgent | 1 | All | Research |

Investigate diet and prey ecology:

|

|

Table 4. Specific approaches to recovery of the American Badger in Ontario

| Priority | Objective Number | Threats Addressed | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Anticipated Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgent | 1, 2, 3, 4 | All | Document distribution, abundance and movement | Collate all NHIC historical sighting records and OMNR records, and ensure that all partners report sightings to the recovery team Map all confirmed records Develop reporting and monitoring protocols Collect and analyze roadkilled and trapped specimens, as well as scat and hair samples Monitor badger movements through radio-telemetry studies | Improved understanding of badger distribution and abundance (historical and current) Improved understanding of badger movements and diet Establishment of working partnerships Better targeting of recovery actions |

| Urgent | 1, 4 | All | Research |

Investigate connectivity and relatedness among populations of badgers:

|

Improved knowledge of populations and barriers to animal movement and gene flow Refinement of recovery efforts |

| Urgent | 1 | All | Research |

Investigate diet and prey ecology:

|

|

| Recommended | 2, 3 | Grassland habitat loss, persecution, incidental trapping | Public awareness and outreach |

|

|

2.4 Performance measures

Table 5. Performance measures

| Broad Approach/Strategy | Performance Measures |

|---|---|

| Documentation of distribution and abundance |

|

| Habitat mapping |

|

| Research |

|

| Rehabilitation |

|

| Development of partnerships |

|

| Public awareness and outreach |

|

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA 2007, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Although information on badger ecology in Ontario is limited, there is considerable literature from across North America that indicates that American Badgers consistently depend on the shelter of dens and fossorial rodent prey for survival. Considering these requirements, the recovery team recommends that American Badger dens and areas determined to support available prey within foraging range of active badger dens be considered in developing a habitat regulation.

Badger dens

For the purposes of this recovery strategy, burrows that American Badgers actively or regularly occupy as a residence or use in rearing young are referred to as "dens." Burrows that badgers create for foraging and capture of prey are not considered to be dens unless they are also used as a residence.

Dens have been determined to be a central component in the life of badgers (Newhouse and Kinley 1999). Between periods of foraging activity, badgers use and reuse dens as temporary residences (Lindzey 1978, Newhouse 1999). Dens can also be larger, more complex burrows used for the rearing of young (natal dens) (Lindzey 1976) or for overwintering (Newhouse 1997). In all of these instances, dens provide shelter from climatic conditions (Newhouse and Kinley 1999) and protection from potential predators such as coyotes (Ontario American Badger Recovery Team 2008). Since dens are underground excavations that can extend several metres laterally from the entrance (Newhouse and Davis 2002, Eldridge 2004), a corresponding area surrounding the entrance should be included in the identification of a den feature. Badgers are known to reuse dens more frequently than creating new ones (Lindzey 1987 Newhouse 1999), so the protection of existing, periodically occupied burrows may be important to the survival and recovery of the species in Ontario. The recovery team considers any occupied den or den that monitoring indicates is habitually occupied to be an important residence feature that should be considered for inclusion within the habitat regulation. Since badgers have been found to reuse dens, it is recommended that any identified den feature be protected for at least one year after the last use by an American Badger.

Foraging habitat

Badger dens have been determined to occur in areas of available prey (Messick 1987), and prey availability is believed to be a determining factor in both the location of den sites and the size of badger home ranges (Newhouse 1999). In Ontario, badgers are therefore likely to select den locations near available populations of groundhogs, cottontails, mice and meadow voles, which are believed to be important prey (Dobbyn 1994, Ontario American Badger Recovery Team 2008). Therefore, it is recommended that any areas that are identified to support available prey species within a determined foraging distance of an occupied American Badger den and that the species is using for foraging or feeding should be considered for inclusion within a habitat regulation. Foraging habitat areas may include specific prey burrows or complexes of burrows, as well as the extent or portion of a vegetation community or other spatial area where the prey have been identified to occur.

2.6 Existing and recommended approaches to habitat protection

Most of the lands in southwestern Ontario where the American Badger is found are privately owned (a large portion of them are actively farmed), near urban and rural areas, and dissected by transportation corridors. This, and the badger’s large range size, will pose significant challenges in establishing habitat restoration and protection. Similar challenges are likely to exist in northwestern Ontario, where most documented badger occurrences are in areas already subject to intensive agricultural use and aggregate extraction. However, forest edge habitat (where badger dens have been occasionally observed in southwestern Ontario) is fairly stable. As well, in some parts of Ontario nature reserves, conservation areas and provincial parks also offer good opportunities for both habitat protection (under the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act) and stewardship. New environmental programs being developed for agriculture (e.g., within the federal government’s Agricultural Policy Framework; the Keystone Agricultural Producers' Alternate Land Use Program; buffer-related programs through Ducks Unlimited, the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association and local conservation authorities) will also add and enhance wildlife habitat in Ontario in the next decade.

Currently, "significant habitat" of the American Badger in Ontario is protected from development under Ontario’s Planning Act through application of the Provincial Policy Statement. The American Badger receives species protection throughout the province under the ESA 2007. The Act also provides the means to protect American Badger habitat through a regulation. If a habitat regulation is not developed for the species, then its habitat will be protected under the general habitat provisions of the ESA 2007 as of June 30,2013. These habitat provisions would protect habitat of both southern and northwestern populations of the American Badger under the ESA 2007 and apply on both public and private lands. A small number of historical badger observations on federal lands (First Nations reserves) in southern Ontario are known, so if more recent occurrences of this species and its habitat are identified in these areas, they will also be protected under the federal SARA.

2.7 Effects on other species

Owing to a lack of research on badgers in Ontario, little is known about the influences of the American Badger on prey populations. Because of the overall rarity of the species in relation to other common predators such as coyotes and feral cats, any impact that enhanced badger numbers have on groundhog, rabbit and small rodent populations is likely to be insignificant.

Any recovery efforts for the population and habitat of the American Badger, which is primarily a grassland species, could have positive impacts on other grassland species, including prey species and several species at risk, such as Barn Owl (Tyto alba), Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), Henslow’s Sparrow (Ammodramus henslowii) and Karner Blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis). Partnerships with organizations such as Tallgrass Ontario and the Carolinian Canada Coalition will benefit badger recovery efforts and increase public awareness of and appreciation for the species, as well as other grassland species and habitat. The recovery implementation groups will play a beneficial role in increasing public appreciation of badgers through outreach efforts.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Apps, C.D., N.J. Newhouse, and T.A. Kinley. 2001. Habitat associations of American badgers in southeast British Columbia. Technical report to Columbia Basin Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, Nelson, B.C.; East Kootenay Environmental Society, Kimberley, B.C.; Tembec Industries, B.C. Division, Cranbrook, B.C.; and Parks Canada Agency, Radium Hot Springs, B.C.

Baker, R.H. 1983. Michigan Mammals, Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Michigan. 642 pp.

Collins, S.L., and D.J. Gibson. 1990. Effects of fire on community structure in tallgrass and mixed-grass prairie. pp.81-98, in S.L. Collins and L.L. Wallace (eds.). Fire in North American Tallgrass Prairies, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Delaney, K., L. Rodger, A. Woodliffe, G. Rhynard, and P. Morris. 2000. Planting the Seed.

A Guide to Establishing Prairie and Meadow Communities in Southern Ontario. Environment Canada.

Dobbyn, J. 1994. Atlas of the Mammals of Ontario. Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Toronto, Ontario. p. 92.

Eldridge, D.J. 2004. Mounds of the American Badger (Taxidea taxus): significant features of North American shrub-steppe ecosystems. Journal of Mammology 85(6):1060-1067.

Gremillion-Smith, C. 1985. Range extension of the badger (Taxidea taxus) in southern Illinois. Transactions of the Illinois Academy of Science 78:111-114.

Hall, E.R. 1981. The Mammals of North America. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Harris, R. 1994. Fur harvest and other records of badger, bobcat, grey fox, and opossum in Ontario. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (unpublished).

Jackson, H.H.T. 1961. Mammals of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin. 504 pp.

Jeffersonii Badger Recovery Team. 2008. Recovery strategy for the Badger (Taxidea taxus) in British Columbia. Prepared for the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, B.C. 45 pp.

Lesica, P., and F.W. Allendorf. 1995. When are peripheral populations valuable for conservation? Conservation Biology 9:753-760.

Lindzey, F.G. 1976. Characteristics of the natal den of a badger. Northwest Science 50:178-180.

Lindzey, F.G. 1978. Movement patterns of badgers in northwestern Utah. Journal of Wildlife Management 42:418-422.

Lindzey, F.G. 1982. The North American badger. Pp. 653-663, in J.A. Chapman and G.A. Feldhamer (eds.). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management and Economics, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

Lindzey, F.G. 1987. Badger Taxidea taxus. Pp. 653-663, in M. Novak, J.A. Baker, M.E. Obbard, and M. Malloch (eds.). Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America, Ontario Fur Managers Federation and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Queen’s Printer, Toronto, Ontario.

Lintack, W.M., and D.R. Voigt. 1983. Distribution of the badger, Taxidea taxus, in southwestern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 97:107-109.

Long, C.A. 1972. Taxonomic revision of the North American Badger, Taxidea taxus. Journal of Mammology 53:725-759.

Long, C.A. 1973. Taxidea taxus. Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogy 26:1-4

Messick, J.P. 1987. North American badger. Pp. 587-597, in M. Novak, J.A. Baker, M.E.

Obbard, and M. Malloch (eds.). Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America, Ontario Fur Managers Federation and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Queen’s Printer, Toronto, Ontario.

Messick, J.P., and M.G. Hornocker. 1981. Ecology of the badger in southwestern Idaho. Wildlife Monographs 76:1-53.

Minta, S.C. 1993. Sexual differences in spatio-temporal interaction among badgers. Oecologia 96:402-409.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life (web application). Version 6.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. NatureServe explorer (accessed February 4, 2009).

Newhouse, N. J. 1997. East Kootenay badger project 1996/97 year end summary report. Forest Renewal British Columbia, Cranbrook, B.C.; Columbia Basin Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, Nelson, B.C.; and Kootenay National Park, Radium Hot Springs, B.C.

Newhouse, N.J. 1999. East Kootenay badger project 1998/99 year end summary report.

East Kootenay Environmental Society, Kimberly, B.C.; Forest Renewal British Columbia, Cranbrook, B.C.; Columbia Basin Fish and Wildlife Compensation Program, Nelson, B.C.; and Canadian Parks Service, Radium Hot Springs, B.C.

Newhouse, N.J., and T.A. Kinley. 1999. Update COSEWIC status report on the American badger Taxidea taxus in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American badger Taxidea taxus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario. 26 pp.

Novak, M., M.E. Obbard, J.G. Jones, R. Newman, A. Booth, A.J. Satterthwaite, and G. Linscombe. 1987. Furbearer harvests in North America 1600–1984. In Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America, Ontario Trappers Association, Toronto, Ontario. 270 pp.

Ohio Historical Society. 2005. Badger. Ohio History Central: An online encyclopedia of Ohio history. Ontario American Badger Recovery Team. 2008. Unpublished data.

Rahme, A.H., A.S. Harestad, and F.L. Bunnell. 1995. Status of the badger in British Columbia. Wildlife Working Report No. WR-72, B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Victoria, B.C.

Rigney, H. 1999. Still at home in the Badger State. Wisconsin Natural Resources Magazine, December issue. 6 pp.

Royal Ontario Museum, 2006. Ontario’s Biodiversity: Species at Risk. http://www.rom.on.ca/ontario/risk.php?region=5 [link inactive].

Ruggiero, L.F., K.B. Aubry, S.W. Buskirk, L.J. Lyon, and W.J. Zielinski (eds.). 1994. The scientific basis for conserving forest carnivores: American marten, fisher, lynx and wolverine in the western United States. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service General Technical Report RM-254.

Sadowski, C., and J. Bowman. 2007. Necropsy of American Badgers from southern Ontario. Unpublished data.

Sadowski, C., J. Bowman, M. Gartshore, and R. Gould. 2007. An aerial track survey for endangered badgers in southern Ontario. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Unpublished report.

Sargeant, A.B., and D.W. Warner. 1972. Movements and denning habits of a badger. Journal of Mammalogy 53:207-210.

Scobie, D. 2002. Status of the American badger (Taxidea taxus) in Alberta. Wildlife Status Report No. 43, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Sustainable Resources Development, and Alberta Conservation Association, Edmonton, Alberta. 17 pp.

Shantz, V.S. 1953. Additional information on distribution and variation of eastern badgers. Journal of Mammology. 34:338-389.

Skitt, L., and J. Van den Broeck. 2004. Distribution and preliminary landscape analysis of contributing factors for two rare and one endangered mammal of Fort Frances district: Franklin’s ground squirrel, white-tailed jackrabbit, American badger. Fort Frances District Report series No. 62. 61 pp.

Stardom, R.P. 1979. Status report on the American badger Taxidea taxus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

Stewart, W.G. 1982. Mammals of Elgin County. St. Thomas Field Naturalists, Impressions Printing, St. Thomas, Ontario.

Warner, R., and B. Ver Steeg. 1995. Illinois badger studies. Final Report, Federal Aid Project No. W-103-R-1-6.

Ver Steeg, B., and R.E. Warner. 1999. The distribution of badgers (Taxidea taxus) in Illinois. Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science 93(2):151-163.

Weaver, J.L., P.C. Paquet, and L.F. Ruggiero. 1996. Resilience and conservation of large carnivores in the Rocky Mountains. Conservation Biology 10:964-976.

Recovery strategy development team members

| Name | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Ron Gould (Chair) | OMNR, Aylmer District |

| Jeff Bowman | OMNR, Wildlife Research and Development Section |

| Peter Carson | Norfolk Field Naturalists, Tallgrass Ontario |

| Jenn Chikoski | OMNR, Thunder Bay District |

| Todd Farrell | Nature Conservancy of Canada |

| Mary Gartshore | Norfolk Field Naturalists |

| Cathy Quinlan | Upper Thames River Conservation Authority |

| Bernt Solymár | EarthTramper Consulting Inc. |

| John Vandenbroeck | OMNR, Fort Frances District |

Advisors to recovery team

| Name | Affiliation |

|---|---|

| Maria Franke | Toronto Zoo |

| Hilary Gignac | OMNR, Northwest Region |

| Chris Heydon | OMNR, Wildlife Section |

| Chris Risley | OMNR, Species at Risk Branch |

| Carrie Sadowski | OMNR, Wildlife Research and Development Section |

| Don Sutherland | OMNR, NHIC |

| Allen Woodliffe | OMNR, Aylmer District |