Anti-Racism Data Standards - Order in Council 897/2018

Data Standards for the Identification and Monitoring of Systemic Racism

Introduction

The Data Standards for the Identification and Monitoring of Systemic Racism, also known as Ontario’s Anti-Racism Data Standards (Standards) were established to help identify and monitor systemic racism and racial disparities within the public sector.

The Standards establish consistent, effective practices for producing reliable information to support evidence-based decision-making and public accountability to help eliminate systemic racism and promote racial equity.

The Government of Ontario is committed to helping to create an inclusive and equitable society for all Ontarians. By identifying and monitoring systemic racial disparities, public sector organizations will be better able to close gaps, eliminate barriers, and advance the fair treatment of everyone.

Purpose

The purpose of the Standards is to set out requirements for the collection, use, disclosure, de-identification, management, publication and reporting of information, including personal information. They help enable public sector organizations (PSOs) to fulfil their obligations under the Anti-Racism Act, 2017 (ARA) to identify and monitor racial disparities in order to eliminate systemic racism and advance racial equity.

Legal Authority

The Standards have been made by the Minister Responsible for Anti-Racism under the authority of s. 6(1) of the ARA and have been established by approval of the Lieutenant Governor in Council. The Information and Privacy Commissioner (IPC) and the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) were consulted in developing them.

The Standards should be read alongside the ARA and its associated regulations.

Application

The Standards apply to PSOs, as defined in the ARA, that are required or authorized by the regulations to collect personal information related to specific programs, services, and functions. This includes personal information related to Indigenous identity, race, religion, ethnic origin, and other personal information listed in the regulations.

PSOs listed in regulations must comply with the ARA, and all or part of the Standards. The particular standards each organization must follow are specified within the ARA itself, and in the regulations.

The Standards do not replace, limit or diminish any responsibilities or obligations owed to persons under the Ontario Human Rights Code, 1990 (the Code).

Organizations that are not authorized or required to collect personal information in regulations made under the ARA may also be authorized to collect, use and disclose personal information for the purpose of identifying and monitoring systemic racism and racial disparities under other Acts, including the Code.

In such cases, organizations must follow the requirements of relevant legislation, such as the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) or the Municipal Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (MFIPPA). Organizations may consider the Standards and the related guidance in developing and implementing any program to identify, monitor, and eliminate systemic racism and advance racial equity.

Scope

The Standards govern how organizations manage information, including personal information that is collected under the authority of the ARA. The purpose of collecting this information is to understand how systemic racism impacts Indigenous, Black, and racialized groups, and to identify potential racial inequalities.

The Standards set out requirements, rationale, and guidance at every stage from planning and preparation to analysis and reporting. This includes, collecting, using, disclosing, de-identifying, and managing information, including personal information.

The Standards do not provide guidance on how to mitigate, eliminate, or prevent adverse racial impacts and inequitable outcomes of policies and programs.

The IPC may review the information handling practices of any organization subject to the ARA to determine if the requirements under the ARA, the regulations and the Standards have been met. If the Commissioner determines that a practice contravenes the ARA or regulations, the Commissioner may order a PSO to stop the practice, destroy personal information collected or retained under the practice, change the practice, or implement a new practice.

How to use this document

In addition to specific Standards, this document offers rationales and guidance:

- Standards

- are requirements that apply to PSOs regulated under the ARA.

- Rationales

- provide reasons behind the Standards.

- Guidance

- describes exemplary practices and important considerations to take into account in complying with the Standards.

The Standards reflect consideration of the diverse functions, needs and operational realities of PSOs in Ontario.

Principles

These principles should be followed by organizations in interpreting and applying the Standards:

- Principle 1: Privacy, Confidentiality, and Dignity

- Protect the confidentiality of personal information, and respect the privacy and dignity of individuals, groups, and communities.

- Principle 2: Commitment and Accountability

- Be accountable for using the Standards to help eliminate systemic racism and advance racial equity.

- Principle 3: Impartiality and Integrity

- Apply the Standards impartially and promote public confidence in efforts to eliminate systemic racism and advance racial equity.

- Principle 4: Quality Assurance

- Make continuous efforts to ensure the quality of the personal information collected, to conduct analysis in a careful and thorough manner, and to verify the accuracy of reported findings.

- Principle 5: Organizational Resources

- Use resources in ways that fulfill the requirements of the Standards.

- Principle 6: Transparency, Timeliness and Accessibility

- Collect and report on information in a timely manner, making the information available to the public in a way that is clear, transparent, and accessible.

Overview of the Standards

- Assess, Plan and Prepare

- Identify need and establish specific organizational objectives for personal information collection based on stakeholder and community input.

- Determine organizational priorities and resources and conduct a privacy impact assessment.

- Identify meaningful policy, program, or service delivery outcomes, and establish an analysis plan.

- Establish data governance processes and develop and plan collection policies and procedures, including measures related to quality assurance and security of personal information.

- Identify training needs and develop and deliver appropriate training and other resources to support compliance with the ARA, the regulations and the Standards, and relevant privacy legislation.

- Collect Personal Information

- Communicate the purpose and manner of personal information collection to clients and communities.

- Implement the collection of personal information based on voluntary express consent.

- Manage and Protect Personal Information

- Implement processes for quality assurance and the security of personal information.

- Maintain and promote secure systems and processes for retaining, storing, and disposing of personal information.

- Limit access to and use of personal information

- Analyse the Information Collected

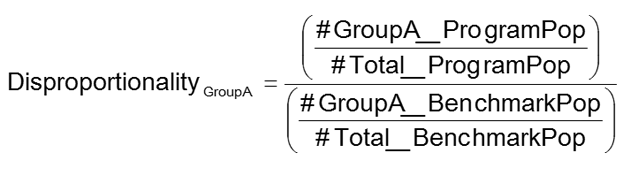

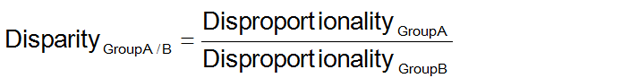

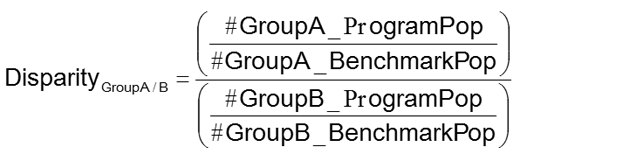

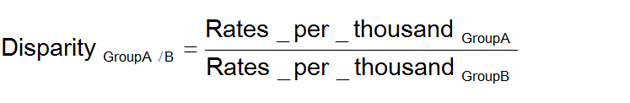

- Calculate and interpret racial disproportionality or disparity statistics.

- Apply thresholds and interpret whether notable differences exist that require further analysis and/or remedial action.

- Release of Data and Results of Analysis to the Public

- De-identify data sets and results of analyses before making information public, consistent with Open Government principles.

- Include results of racial disproportionalities or disparities in the reports to the public, along with thresholds used.

- Support and Promote Anti-Racism Organizational Change

- Use information to better understand racial inequities, and to inform evidence-based decisions to remove systemic barriers and advance racial equity.

- Continue to monitor and evaluate progress and outcomes.

- Promote public education and engagement about anti-racism.

- Participant Observer Information (POI)

- Plan to collect, manage and use POI with input from affected communities and stakeholders.

- Implement the collection of POI according to requirements for indirect collection.

- Have measures in place to ensure the accuracy of POI before use.

Periodic review

With involvement of affected communities, the Government of Ontario will review the Standards periodically to ensure that they continue to fulfill the purpose set out under s. 6(1) of the ARA.

The Minister Responsible for Anti-Racism will oversee the periodic review. The OHRC and IPC will be consulted before any amendments are made to the Standards.

Context

Understanding racism

These Standards are designed to address racism at a systemic level, through the collection and analysis of personal information in connection with specific functions, programs and services of PSOs to identify and monitor potential racial inequities.

Racism consists of ideas, beliefs or practices that establish, maintain or perpetuate the superiority or dominance of one racial group over another. The OHRC notes that racism differs from prejudice in that it is tied to the social, political, economic, and institutional power that is held by the dominant group in society (OHRC, Policy and guidelines of racism and racial discrimination).

Systemic racism occurs when institutions or systems create or maintain racial inequity often as a result of hidden institutional biases in policies, practices, and procedures that privilege some groups and disadvantage others. In Ontario, systemic racism can take many forms, such as:

- Officials who single out members of Indigenous, Black, and racialized groups for greater scrutiny or different treatment;

- Opportunities shared through informal networks that exclude Indigenous, Black, and racialized individuals; and

- Lack of public attention and policy concern regarding social, health and economic problems that disproportionately affect Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities.

Throughout Canada’s history including prior to Confederation, colonial practices, including the oppression of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of people of African descent, have entrenched public attitudes, beliefs, and practices that continue to negatively impact Indigenous, Black, and racialized individuals and communities in social, economic, and political life. The exclusion and devaluing of different groups is also evident in Canada’s history of discriminatory immigration and citizenship policies, including restricted admission for Jewish people at the height of the Holocaust; the Head Tax on Chinese immigrants; and the internment of Japanese Canadians during World War II, among many other examples.

The legacy of this history impacts Indigenous, Black, and racialized groups by perpetuating the advantages and institutional power of the historically dominant group (White individuals with higher socio-economic status). The negative consequences of this legacy are compounded over time and transmitted intergenerationally. Systemic racism continues to result in racially inequitable outcomes across public sectors such as education, child welfare and justice. Racist ideas and practices persist in a variety of forms, including anti-Black racism, anti-Indigenous racism, Islamophobia and antisemitism (see glossary for definitions of these terms).

Understanding Anti-Racism

Anti-racism is a proactive course of action to identify, remove, prevent, and mitigate the racially inequitable outcomes and power imbalances between dominant and disadvantaged groups and the structures that sustain these inequities. It recognizes the historic nature and cultural contexts of racism, and focuses critically on systemic racism.

Anti-racism aims to ensure the absence of unfair treatment, which includes exclusionary or discriminatory practices. The Standards set out requirements to collect, analyze and report information to help assess whether there is fair treatment and equitable access to public services and programs, such as:

- policing services;

- bail processes;

- high quality education and healthcare; and

- supports and services for the well-being of children and families.

Anti-racism for Indigenous peoples is distinct from anti-colonialism

Anti-racism for Indigenous people must be understood in light of the ongoing impact of assimilative policies and laws on Indigenous people, and the prevalence of anti-Indigenous racism in Ontario. However, it is important to recognize that anti-racism is a distinct component of the larger struggle of anti-colonialism for Indigenous peoples. One reason that anti-racism does not fully capture the experiences of many Indigenous communities is that it tells only one part of the story.

The other part of the story is based on the fact that Indigenous peoples were here long before the coming of Europeans. This reality grounds their claims for self-determination and for recognition of Indigenous sovereignty, laws, and governance structures. Indigenous peoples have a unique legal status recognized constitutionally.

Anti-colonialism, therefore, is broader than anti-racism because it includes recognition of Indigenous peoples’ inherent rights and sovereignty, constitutionally protected Aboriginal and Treaty rights, and right to self-determination in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Understanding Canada’s colonial history and its ongoing impacts

Throughout Canada’s history, successive governments have implemented laws and policies aimed at devaluing and destroying Indigenous identities and cultures within Canada. The federal Indian Act and the Indian Residential Schools

Without an understanding of the historical context and current realities facing Indigenous communities, there is a danger that these socioeconomic indicators could be misunderstood as a reflection of Indigenous peoples’ own choices rather than as a direct consequence of assimilative policies and laws aimed at cultural genocide.

This means that in some cases there are different considerations that must be taken into account when decisions are being made about an Indigenous person’s liberty (i.e. consideration of the Gladue principles)

The impact of research and data collection on Indigenous communities

Within this colonial history, Indigenous communities have had an extremely difficult history associated with research and data collection. Indigenous people have been the subject of non-consensual medical and social experiments without regard for their human rights. In addition, the government of Canada assigned names and identification numbers, and collected data to control the movement of Indigenous peoples, limit access to services, and monitor Indigenous populations.

Many Indigenous people and communities are understandably suspicious of government data-collection efforts. There may be an unwillingness to disclose Indigenous identity, especially in cases where particular groups of government or law enforcement workers have had a significant role in enforcing assimilation and other punitive laws and policies.

Care must be taken to ensure that Indigenous-related information is collected according to appropriate policies and protocols, and that the information is managed and used in ways that benefit Indigenous communities. Anyone responsible for collecting information must also be trained to understand the causes of the deep mistrust that Indigenous people and communities have of government systems, personnel, and information collection efforts.

Respecting Indigenous identity and self-identification

Customarily, Indigenous communities across what is currently known as Canada may not self-identify as belonging to one pan-Indigenous group. Instead, Indigenous identity may be tied to an individual’s clan, community, nationhood, or language family.

This is an important consideration when collecting information about Indigenous identity. The Standards contain a specific question and allow for flexibility in the way Indigenous people choose to self-identify. This question is distinct from the question about race, which is designed to collect information about how Indigenous people may be racialized by society.

Applying research and data collection as anti-racism tools

For centuries, government-led data collection, analysis and measurement processes in Canada has been centred in Eurocentric perspectives. Properly applied, the Standards provide a way to use data for anti-racism purposes, grounded in an understanding of the historical context and the current realities facing Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities. Public accountability and community involvement are core aspects of the Standards and will help to ensure that the information gathered serves the racial equity intentions of the ARA.

Standards and guidance

1. Assess, plan and prepare

Reasons to Collect Information

PSOs should collect information if there are observed unequal outcomes for Indigenous, Black, and racialized persons, persistent complaints of systemic racial barriers, and/or widespread public perception of systemic racial barriers or bias within the organization.

Guidance in the OHRC policy and guidelines on racism and racial discrimination states that “data collection and analysis should be undertaken where an organization or institution has or ought to have reason to believe that discrimination, systemic barriers or the perpetuation of historical disadvantage may potentially exist.”

Assess and Plan

Standard 1. Assess and Plan for Compliance with the ARA, the Regulations and the Standards

PSOs must assess their objectives and priorities for the collection and use of personal information for the purpose of conducting analyses to identify and monitor systemic racism and racial disparities.

PSOs must sufficiently plan and prepare for complying with, and implementing the ARA, the regulations and the Standards with input from affected communities, stakeholders, and partners.

Rationale

Planning and preparation is an integral part of understanding the requirements of and ensuring compliance with the ARA, the regulations and the Standards.

Guidance

Assess what personal information is required, for the purpose of the ARA, to identify and monitor racial inequalities in outcomes and help promote racial equity and fair treatment in programs, services, and functions.

Before collecting, using or disclosing any personal information, organizations should consider the following (generally in the order given):

Community input:

Regularly engage with Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities, stakeholders, clients, and partners to understand their priorities, concerns, needs, and interests in collection, management, use and analysis of information.

Organizational objectives and priorities:

Identify clear organizational objectives for the collection and use of personal information under the ARA. In relation to matters required or authorized in the regulations, PSOs should scan the specific policies, practices, services, and/or programs to prioritize how to track and monitor potential systemic racial inequalities. (See OHRC Count me in! Guide).

The race-based personal information will always need to be combined with other information in order to determine the impact of race on outcomes. Organizations should consider the personal information they need to collect, or already lawfully collect for program purposes, that may also be used for the purpose of identifying and monitoring systemic racial inequalities.

Identifying organizational objectives should also include determining which performance measures should be tracked for the purposes of identifying and monitoring systemic racism and racial disparities, and/or measuring progress in advancing racial equity. PSOs should consider monitoring the outcomes of key decisions in a client’s interaction with a service or system (see Appendix A for an example).

Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA):

Conduct a PIA to identify privacy implications, risks and mitigation strategies. A useful resource is Planning for Success: Privacy Impact Assessment Guide, developed by the IPC.

Resources and Training:

Assess and review organizational resources, capacities, and competencies needed to collect, use, manage, de-identify, analyze, publish, and report information. This includes reviewing existing processes, information technology, and software capabilities, as well as assessing the expertise and skills needed to comply with the Standards. In most cases, training the employees, officers, consultants, and agents of the organization will be necessary to ensure the proper implementation of the Standards (see Standard 4).

Public Communication and Outreach:

Communicate the organization’s information-related objectives and plans to the public, affected communities, and clients. This includes external communications and processes for informing individuals of their privacy rights and the PSO’s policies and protocols.

Indigenous Interests in Data Governance

PSOs should consider the interests of Indigenous communities and organizations in exercising authority, control, and shared decision making in the collection, management, use and disclosure of information regarding Indigenous people and communities, consistent with relevant privacy legislation.

Indigenous data governance considerations vary between First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities and organizations. There are common goals, including emphasis on the importance of engagement, transparency, and Indigenous ownership and control of information (including how it is collected, used, managed, analyzed, interpreted, and reported publicly).

Indigenous data governance principles aim to ensure that information collected from Indigenous communities is used to empower communities with knowledge and tools to work towards positive community outcomes.

Transparency is the focus in relationship building, proactive engagement, and strategic data governance partnerships with the government and/or other broader public service bodies, institutions, and agencies.

Data sharing agreements between PSOs and Indigenous communities and their representatives and partners can be an effective way to respect Indigenous interests in data governance, but such agreements must be undertaken in accordance with the requirements of the ARA and applicable privacy legislation.

Governance and Accountability

Standard 2. Establish Organizational Roles and Responsibilities

PSOs must establish clear accountability mechanisms and rules, with organizational roles and responsibilities, for all aspects of collection, management, use (including analysis), disclosure, and de-identification of personal information, and the public release and reporting of information. There must be at least one manager who is accountable for oversight and ensuring compliance with the ARA, the regulations and the Standards.

Rationale

Clear organizational roles and responsibilities help PSOs comply with the ARA, support transparency, and promote accountability for the proper management of personal information, as well as reporting for the purpose set out in the ARA, the regulations and the Standards.

Guidance

PSOs should work with their records and information management (RIM), privacy, and security professionals to ensure that the collection, use, disclosure, management, security, de-identification, and disposition of records containing personal information is done in accordance with the Standards, applicable privacy legislation, and the Archives and Recordkeeping Act, 2006, if applicable.

PSOs should implement governance and accountability practices such as:

- Appoint a privacy point-person, such as a Privacy Officer or a senior official who has been delegated privacy responsibilities of the “Head” under FIPPA/MFIPPA, to ensure senior management commitment to privacy protection;

- Establish reporting mechanisms for overall compliance activities, as well as for reporting privacy and security breaches;

- Maintain a personal information inventory (know what personal information is held, its sensitivity, where it is held, and why it is collected, used, and disclosed); and

- Implement a privacy management plan to comply with the Standards, including measures for monitoring, assessing and reviewing privacy and security policies, practices, and controls.

Standard 3. Third Party Service Providers Acting on Behalf of PSOs

PSOs are accountable for ARA-related activities undertaken by a third party service provider acting on their behalf. PSOs must ensure that third parties understand and comply with all requirements under the ARA, the regulations and the Standards.

Rationale

When a service or activity is outsourced, a PSO continues to be accountable for complying with the ARA and applicable privacy legislation. Ensuring that third parties understand and abide by all ARA requirements when acting on behalf of a PSO is necessary to protect privacy.

Guidance

Agreements with third parties should require compliance with privacy obligations in the ARA and any other applicable legislation, including the FIPPA and MFIPPA.

The agreements should require that third party service providers be familiar with the requirements of the ARA and the Standards, applicable privacy legislation, and other legislative obligations relating to collecting, using, disclosing, de-identifying, managing, disposing, and reporting information, as well as the PSO’s protocols for privacy breaches and management response to security incidents.

When contracting third party service providers that will have access to personal information or will be involved in collection, use (including analysis), and disclosure, consult with legal, procurement, records and information management, and privacy professionals to:

- Assess the privacy and security risks and the sensitivity of the information involved;

- Develop an information protection plan to ensure protection of access and privacy rights are key considerations in developing third-party agreements;

- Carefully vet potential service providers to assess their knowledge and capabilities to meet the PSO’s defined privacy requirements in procurement and contracting; and

- Audit and monitor the service provider’s activities for the duration of the agreement to ensure compliance.

Training and Supporting Resources

Standard 4. Training for Employees, Officers, Consultants and Agents to Perform their Duties

PSOs must provide relevant and effective training and supporting resources to their employees and officers who collect or have any access to personal information so that they clearly understand how to comply with the requirements of the ARA, the regulations and the Standards.

PSOs must ensure that their consultants and agents who collect or have any access to personal information have relevant and effective training and supporting resources so that they clearly understand how to comply with the requirements of the ARA, the regulations and the Standards.

Rationale

Training and supporting resources are essential for the proper application of the Standards.

Guidance

Employees, officers, consultants and agents of organizations should complete any necessary training before they begin their duties and should receive training regularly thereafter, as needed, to ensure ongoing compliance. In addition to establishing knowledge of how to protect personal information, training objectives should include building competencies and capacities in anti-racism and cultural safety.

Resources should reinforce learning and maintain knowledge, and should include relevant tools for applying skills and techniques.

Training and support resources should be periodically reviewed and evaluated so that they are relevant, effective, and delivered efficiently to relevant employees, officers, consultants, and agents.

2. Collection of personal information

The purpose of collecting personal information under subsection 7(2) of the ARA is to eliminate systemic racism and advance racial equity.

Manner of Collection

Subsection 7(3) of the ARA requires that personal information be collected directly from the individual to whom the information relates, unless the Standards authorize another (indirect) manner of collection.

Standard 5. Direct Collection

PSOs must collect personal information directly from the individual to whom it relates unless otherwise authorized by Standard 6.

Rationale

Collecting personal information directly from the individual to whom it pertains is critical to ensuring that voluntary express consent is sought and obtained. It also respects individual dignity.

Guidance

In addition to collecting personal information from the individual to whom it relates, direct collection can include collecting personal information from an individual who is legally authorized to act on behalf of another individual. This could be a parent with custody of a minor, a legal guardian, or an individual working under a power of attorney.

Prior to collection, PSOs should verify the individual’s legal authority to act on behalf of the other individual. They should also document the verification (see Standards 8 and 9 for consent and notice requirements).

Standard 6. Indirect Collection

PSOs are authorized to collect personal information indirectly in the following circumstances:

- The individual to whom the information relates authorizes another person to provide their personal information

- The individual to whom the information relates is deceased

- Collection of participant observer information (POI) about another individual’s race is undertaken in accordance with Standards 38-43 (see Section 7: Standards for POI)

Rationale

Indirect collection of personal information may be necessary in the circumstances described above because direct collection is not possible or because collecting POI is appropriate in the circumstances.

Guidance

At the time of collection, an individual may wish to authorize another person to provide their personal information. This could be a neighbor, friend, roommate, co-worker, support worker or interpreter. Such authorization can be given by the individual orally to the PSO (in person or over the telephone) or by written consent signed by the individual to whom the information relates. In both cases, the authorization should be recorded and retained by the PSO.

In the case of deceased persons, indirect collection should only take place where there is no apparent trustee for the estate of the deceased person. In this case, PSOs should collect the information from someone close to the deceased individual, like the individual’s next of kin.

In specific circumstances, PSOs may collect POI about an individual’s race only for the purpose of identifying and monitoring racial profiling or racial bias within a specific service, program, or function. Individuals providing POI are limited to employees, officers, consultants, and agents of the PSOs. Further standards and guidance on this form of indirect collection can be found in Section 7.

Consent

Personal information collected directly from the individual to whom it relates must be based on voluntary express consent that is freely given. Subsection 6(8) of the ARA states that no program, service or benefit shall be withheld because an individual does not provide, or refuses to provide, the personal information requested by the PSO. In obtaining consent, PSOs should be careful to make the request in a manner that does not pressure the individual.

Standard 7. Obtain Express Consent

PSOs collecting personal information directly (as set out under Standard 5) must obtain express consent in a way that respects the privacy and dignity of individuals.

Express consent must be knowledgeable and obtained after the individual has been directly provided the information set out in Part 1 of Standard 8 (direct collection).

The required information must be provided in an accessible manner, whether orally, or in writing, or both.

The individual may withdraw consent at any time by providing notice to the PSO, but the withdrawal of the consent does not have retroactive effect where the personal information has already been used by the organization to conduct analysis.

Rationale

Voluntary express consent is an essential part of respecting an individual’s privacy and dignity. Every individual, at any time, has the right to give, deny or withdraw their consent for the collection, and use of their personal information.

Guidance

Express consent is permission for or agreement to the collection and use of personal information. It is given orally, in writing, or by some other positive action specifically by the individual to whom the personal information relates.

Under this form of consent, an organization needs to provide the individual with an opportunity to actively communicate positive agreement to the collection of their personal information. This is in contrast to implied consent, which is an assumption of permission inferred from silence or inaction, such as requiring individuals to “opt out” of the collection. Express consent is less likely to result in misunderstandings or complaints.

Openness, transparency, and accessibility are essential to obtaining meaningful consent. PSOs should clearly explain the voluntary nature of consent, how the requested personal information will be used and disclosed (where relevant), and how the information will be protected. This enables individuals to make informed decisions about what they are consenting to and ensures that they understand that they have the right to withhold or revoke their consent at any time.

When obtaining express consent, PSOs should give special consideration to the capacity of the individual to provide consent. When a PSO determines that an individual does not have the capacity to consent, consent may be obtained from a person legally authorized to act on the individual’s behalf, such as a family member or legal guardian.

PSOs should maintain records of consent provided, withheld, or withdrawn and include the dates of consent. If the personal information is collected online, PSOs should provide a click-through notice that requires respondents to consent to the collection and use of personal information before they proceed.

Withdrawal of consent

Individuals should be informed that they may withdraw their consent to the continued use of their personal information at any time during the collection and over the period during which their personal information is held by the PSO.

Individuals may withdraw consent, and request that the organization delete or stop using their personal information (see Standard 23 Removal of Personal Information for required action after consent is withdrawn). An individual can withdraw their consent by oral or written request to the organization. A withdrawal of consent does not require the PSO to re-conduct analyses that may have used the personal information (the withdrawal does not have retroactive effect).

Notices

The ARA requires PSOs to provide different types of notice for direct (s. 7(4)) and indirect (s. 7(5)) collection, and before they use personal information already in their possession that was collected for another lawful purpose (s. 9(5)).

Standard 8. Notices

Prior to collecting personal information, PSOs must provide notice, either orally or in writing, in a way that is inclusive, accessible, and respects individual privacy.

Part 1 - Notice to Individual - Direct Collection

The ARA (s. 7(4)) requires that when personal information is collected directly, the PSO must inform the individuals providing the information of the following:

- That the collection is authorized under the ARA

- The purpose for which the personal information is intended to be used, including whether it will be combined with other information, including personal information;

- That no program, service or benefit may be withheld because the individual does not provide, or refuses to provide, the personal information; and

- The title and contact information, including an email address, of an employee who can answer the individual’s questions about the collection.

Part 2 - Notice – Indirect Collection

The ARA (s. 7(5)) requires that when personal information is collected indirectly, before collecting the information, the PSO must first publish the following information on a website:

- That the collection is authorized under the ARA;

- The types of personal information that may be collected indirectly and the circumstances in which personal information may be collected in that manner;

- The purpose for which the personal information collected indirectly is intended to be used, including whether it will be combined with other information, including personal information; and

- The title and contact information, including an email address, of an employee who can answer an individual’s questions about the collection.

Part 3 - Notice - Personal Information Already Collected Under Another Act

If the PSO is required or authorized to collect personal information under regulation, the organization may use for an ARA purpose other personal information it has lawfully collected. Before using the other personal information, the ARAs. 9(5) requires that PSOs provide public notice on a website stating that the use is authorized under the ARA, and:

- The types of information that may be used and the circumstances it would be used, including whether it will be combined with other information, including personal information;

- That the purpose for which personal information may be used; and

- The title and contact information, including an email address, of an employee who can answer an individual’s questions about the use of the personal information.

Part 4 - Notice - Individual Authorizes Another Person to Provide Their Personal Information

If an individual authorizes a PSO to indirectly collect their personal information from another person, the PSO must provide notice to the authorized individual in the same manner as in the case of direct collection (Part 1, above).

Part 5 – Notice of Rights to Access, Correct and Withdraw Consent

When giving notice, PSOs must also provide notice that individuals may access and correct their personal information, or withdraw their consent.

In the case of POI, notice must be provided that individuals may access the POI that relates to them and may request that a statement of disagreement be attached to the POI.

Rationale

In both direct and indirect collection, notice informs individuals about why their information is being collected and how it will be used. It also enables those individuals to contact PSOs to get answers to any questions they may have about the collection and subsequent use of the information.

In addition, notice is an essential part of obtaining express consent from the individual to collect and use personal information. It ensures that individuals understand the purpose of the collection and use and know that providing their personal information is voluntary.

Guidance

Notice may be given orally, in written form, or both. PSOs collecting POI (indirect collection) must give notice on their websites.

PSOs should provide individuals with supporting materials, such as informative pamphlets or responses to frequently asked questions, particularly if notice is given orally.

PSOs should provide notice in a way that is inclusive and responsive to the individual’s needs and respects individual dignity. Notices should be:

- Concise and accessible, in accordance with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 (AODA) and its regulations;

- In plain language and readily understandable; and

- Available in alternative formats and translations, as necessary.

Notices should inform individuals about what they are consenting to and why. PSOs should clearly explain the following:

- What information is being collected under the ARA;

- Why it is being collected;

- How it will be used, and whether it will be combined with other personal information; and

- Who will have access and how privacy will be protected.

Forms used to collect personal information, if separate from the notice, should also state clearly that the collection is voluntary, and that no program, service, or benefit will be withheld if the individual does not provide or refuses to provide the information requested.

Where a PSO’s interaction with Indigenous peoples requires the application of a distinct legal analysis or process, PSOs should ensure that the client is also informed of the applicable provisions.

The ARA provides that nothing in the ARA limits the right of an individual to access and correct personal information held by the PSO in accordance with the access and correction provisions of another Act (e.g. FIPPA or MFIPPA ). In providing notice with respect to both direct and indirect collections, PSOs should inform individuals about any limitations to accessing or correcting their personal information or withdrawing their consent, if such limitations exist under another Act. Similarly, individuals should be informed of their ability to access and request a statement of disagreement to POI information held by a PSO. Individuals should be informed that the correction and removal of personal information does not have retroactive effect.

How to Collect Personal Information

Standard 9. Collection Methods

PSOs must collect personal information using methods and processes that are accessible in accordance with the AODA and its regulations, and that protect individual confidentiality and privacy, and respect individual dignity.

Rationale

Appropriate collection methods and processes that are accessible, protect confidentiality and privacy, and respect individual dignity help to promote the quality of the information collected.

Guidance

Methods for collecting personal information may include online forms, paper or telephone surveys, registration forms, and oral interviews. Personal information collected through oral interview or telephone survey should be accurately recorded in an appropriate and secure manner.

Collection methods should be responsive to the needs of individuals and communities, which may include administering the collection in other languages. PSOs that are subject to the French Language Services Act, 1990 (FLSA) should ensure that notices and methods used to collect personal information are available in French.

It is important that employees, officers, consultants, and agents of PSOs are trained to collect personal information in a respectful, culturally safe, accessible way that ensures individual privacy and confidentiality. This is especially important when personal information is collected by interview.

A culturally safe and respectful method of collection means that individuals feel physically, socially, emotionally and spiritually safe. There is no challenge or denial of a person’s identity and the experience does not diminish, demean, or disempower the cultural identity or well-being of the individual. In addition, this consideration recognizes that, due to the ongoing impacts and legacies of colonization and systemic racism, Indigenous, Black, and racialized people may be uncomfortable with giving personal information about Indigenous identity and race.

Employees, officers, consultants, and agents of PSOs collecting personal information should be prepared to address basic questions or concerns about the collection, including the purpose for the collection, how the information will be used when it can and cannot be disclosed, and how privacy will be protected.

Designing surveys to enhance data quality

PSOs should design their collection processes to support the accuracy and completeness of personal information collected. This includes careful consideration of response options that have been shown to negatively impact the quality and rate of responses.

Survey methodology research has shown that providing non-response options (such as “don’t know” and “prefer not to answer”) to socio-demographic questions tends to decrease data quality and response rates. It is generally not recommended to include these options unless they help to provide useful or valid information. PSOs should consider whether the non-response options can be used and analyzed if collected. For example, consider whether “don’t know” is a valid response and whether that response would be used in analyzes or simply treated as a non-response (treated as missing data).

The potential usefulness of non-response options should be balanced against any compromise to data quality. In some contexts, such as when personal information is collected during an oral interview, “prefer not to answer” can be useful to distinguish between a client who declined to answer the question and a client who was not asked the question by the interviewer.

Prior to asking questions that may be considered sensitive, PSOs should remind clients that the collection is voluntary. To promote higher response rates, they should make sure that all clients understand the purpose of the collection and how their information will be used and protected.

Particularly in the context of longer surveys, it is good practice to remind individuals that they are providing information voluntarily and remind them of the purpose and benefits of providing information.

PSOs using online collection methods should avoid forcing responses (for example, where a respondent must select a response in order to advance to the next question). If a forced-response design is used, then “prefer not to answer” is necessary to ensure that individuals can choose not to provide the information requested.

When to Collect Personal Information

Standard 10. Identifying an Appropriate Time to Collect Personal Information

PSOs must collect personal information at the earliest appropriate time in an individual’s interaction with a program, service, or function.

The collection process must respect the dignity of the individual from whom personal information is collected and minimize repeated requests for the same personal information.

Rationale

Collecting personal information at the earliest appropriate opportunity helps to identify and monitor an individual’s outcomes throughout their participation in a program, service, or function.

Guidance

When feasible and appropriate, it is best to collect personal information at an individual’s first interaction with the program, service, or function, such as at recruitment, registration, or enrolment.

There may be circumstances when direct collection from the individual at the earliest opportunity is overly intrusive or could injure a person’s privacy and dignity. For example, accident victims still at the scene of the accident or individuals being booked into a detention centre may be in crisis, which may make it an inappropriate time to collect personal information. In such cases, the earliest appropriate opportunity should be found.

In other instances, for example in the case of Indigenous accused persons, it may be necessary to gather personal information at the earliest possible stage to ensure that the individual receives relevant services and supports. Federal and provincial legislation, including the Criminal Code of Canada, the Youth Criminal Justice Act, and the Child, Youth and Family Services Act distinguish Indigenous people and require judges and various justice personnel to apply distinct principles, provisions, and processes. Training is essential to ensure that an Indigenous person has the opportunity to self-identify as soon as possible and that the relevant justice personnel are informed.

Order of Questions

Standard 11. Sequence of Indigenous Identity and Race-Related Questions

Where personal information about Indigenous identity, ethnic origin and race are collected, PSOs must sequence the questions so that Indigenous identity and ethnic origin are asked immediately prior to race.

Rationale

The order in which questions are asked helps to promote the accuracy of responses.

Guidance

Research on survey methods shows that the order of questions affects how people respond. Questions that come first provide a frame of reference that influences how respondents interpret and answer later questions.

The sequence of questions can help to improve response rates and the accuracy of the race information provided. When individuals are asked to provide information about more specific identities (such as Indigenous identity and ethnic origin) before they are asked about race, they are more likely to select a race category and less likely to write in a unique response or refuse to answer.

The question about religion can be placed either before the Indigenous identity question or after the race question.

Collection of Personal Information

In accordance with subsection 6(6) of the ARA, the Standards specify the personal information that PSOs may be required or authorized to collect under a regulation made under s. 7(1) of the ARA.

Standard 12. Collecting Personal Information to Better Understand Systemic Racism

The regulations under the ARA may require or authorize PSOs to collect the following personal information:

- Indigenous Identity

- Race

- Ethnic origin

- Religion

- Age

- Sex

- Education

- Geospatial information, such as postal code for place of residence, or place of work

- Socio-economic information, such as educational level, annual income, employment status, occupation, or housing status

- Citizenship

- Immigration status

- Gender identity and gender expression

- Sexual orientation

- Place of birth

- Languages

- Marital status

- Family status

- (Dis)abilities

Rationale

The types of personal information listed above may be relevant for analyzing systemic racial inequalities in outcomes by considering the intersection of race with other social identities. It also supports a better understanding of the factors that potentially contribute to, reinforce, or underlie systemic racial inequalities in outcomes.

Guidance

Collecting personal information about Indigenous identity, race, religion and ethnic origin is essential to the purpose of the ARA. However, additional types of personal information may be necessary to understand the nuances of systemic racial barriers. This means recognizing the ways in which people’s experiences of racism or privilege, including within any one racialized group, may vary depending on the individual’s or group’s additional overlapping or intersecting social identities.

For example, a race-based intersectional analysis could explore whether systemic racial barriers are different for men and women, or for different age groups. Indigenous, Black and racialized individuals may experience unique and distinct systemic barriers shaped by multiple and overlapping identities and social locations such as disabilities, low income, language barriers, etc. The use and analyses of additional personal information can help identify other factors that impact group outcomes.

PSOs should seek to limit the personal information requested to the minimum necessary to fulfill the purposes of collecting the information. For example, if annual household income is relevant but the analysis will not require narrow brackets or exact amounts, consider using the broadest meaningful income brackets.

Collection of Personal Information about Indigenous Identity

Standard 13. Collecting Personal Information about Indigenous Identity

PSOs must collect personal information about Indigenous identity (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) to assist in the identification and monitoring of Indigenous people’s unique experiences of systemic racism and marginalization.

The collection of personal information about Indigenous identity must follow the question and response rules set out below.

The question and response values may deviate from the below at the request of Indigenous communities, or if data sharing agreements are in place between PSOs and Indigenous communities or organizations. However, responses have to map to “First Nations,” “Métis,” and “Inuit” for the purpose of analyses and reporting under the ARA.

Indigenous Identity Question and Categories

Question: Do you identify as First Nations, Métis, and/or Inuit? If yes, select all that apply.

Values (valid code list):

- No

- Yes, First Nations

- Yes, Métis

- Yes, Inuit

Optional Value: Prefer not to answer (permitted only in oral interview processes to record that the question was asked and the respondent chose not to answer).

Response rules: If yes, respondents may select multiple options – First Nations, Métis, and/or Inuit. Respondents may not select both no and yes.

Rationale

Collecting personal information about Indigenous identity in the manner described above (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) is consistent with the approach undertaken by Statistics Canada, in which “First Nations” includes status and non-status Indians. Collecting this information helps to identify and understand Indigenous peoples’ unique experiences of systemic racism resulting from a history of colonialism and the impacts of intergenerational trauma. This contributes to the Ontario government’s commitment to identify and eliminate anti-Indigenous racism in programs, services, and functions.

Flexibility in collecting information about Indigenous identity respects Indigenous interests in determining cultural expression and identification.

The option “prefer not to answer” is allowed when information is collected through oral interview (in person or by telephone). The purpose is to differentiate a client who decides not to answer from a client who was not asked the question.

Guidance

PSOs should work with Indigenous communities and partners to help determine best practices for collecting personal information about Indigenous identity. At the community’s request, or as part of data sharing agreements, a PSO may change how it collects information about Indigenous identity so that Indigenous peoples can self-identify in other, more specific ways, such as:

- Allowing an additional level of response (e.g. provide an open text or drop-down list option for individuals who select “First Nations,” “Métis,” or “Inuit”); or

- Adding “Another Indigenous identity” as a fourth option and allowing open text (write in response option); or

- Including a separate question allowing for individuals to identify a specific First Nations band or community.

It is important to train all employees, officers, consultants, and agents of PSOs to collect personal information about Indigenous identity in a respectful, culturally safe, accessible way that ensures individual privacy and confidentiality and is responsive to the needs of individuals and communities. They should be prepared to address questions or concerns about the collection of Indigenous identity information, including the purpose and benefits of the collection, and how the information will be collected, used, when it can and cannot be disclosed and protected.

Collecting personal information about specific Indigenous cultures, communities, and nationhood

Collecting personal information about Indigenous identity can inform more effective delivery of programs and services that support Indigenous cultural expression and self-determination. It is important that collection processes respect Indigenous culture and nationhood and capture the diversity of Indigenous people who access public services. This supports the advancement of racial equity, and respects Indigenous peoples’ constitutional status.

Indigenous identity categories limited to “First Nations, Métis and Inuit” may not be enough to capture information relevant to policy implementation and service and program delivery or to meet the needs of Indigenous individuals and communities across the province. In frontline service settings, requesting more specific cultural information may be necessary to ensure culturally appropriate services, including language of service, spiritual accommodations, and other required supports. For example, the questions may help identify need for increased access to services in an Indigenous language, or offering basic spiritual supports appropriate to a specific community.

Collection of Personal Information about Race

Standard 14. Race Question

PSOs must collect personal information about race using a preamble and question that enables individuals to self-report race as a social description or category. The following preamble and question are consistent with this approach:

Pre-amble: In our society, people are often described by their race or racial background. For example, some people are considered “White” or “Black” or “East/Southeast Asian,” etc.

Question: “Which race category best describes you? Select all that apply.”

Rationale

Systemic racism is shaped by how society categorizes individuals into racial groups. Race is a social construct, not a reflection of personal identity (as distinct from individual, ethnic or cultural identity). The approach to “race” reflected in the Standards best serves the purpose of identifying and monitoring systemic racism.

Guidance

PSOs should use the preamble and question provided in this Standard unless there is strong evidence that a more plain language version is appropriate and improves the collection of race information.

Wherever feasible, a preamble should be placed immediately before the race question to help respondents understand what the question will be asking. If collecting information online, PSOs may choose to provide the preamble and category descriptions or examples as an “info tip” or “tool tip” (text that appears when a curser hovers over the item without clicking) to make the question clearer.

For the purposes of identifying and monitoring systemic racism barriers and disadvantages, it is important to recognize race as a social construct. Ideas about race are often ascribed to or imposed on people, and individuals and groups can be racialized by others in ways that affect their experiences and how they are treated. Race as a social category is distinct from but may overlap with how people identify themselves, which can be much more varied and complex.

The race question provided in this Standard aligns with how researchers and organizations in other jurisdictions ask questions about race. Using race categories that measure and reflect how an individual may be described by others helps to better identify Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities’ experiences and treatment in society.

Standard 15. Race Categories

PSOs must collect personal information about race using the race categories and applying the response rule set out in the table below.

PSO must present the categories in alphabetical order unless there is evidence that a different order might increase response rates, such as most to least frequent responses to reflect local demographics or individuals most likely to access a program, service, or function.

Wherever feasible, online surveys, forms, and interviews must include the examples or descriptions provided to help individuals select the appropriate responses. Organizations must not introduce subcategories under the required race categories, except where noted in Table 1.

Table 1. Valid values for race categories

| Race categories* | Description/examples |

|---|---|

| Black | African, Afro-Caribbean, African-Canadian descent |

| East/Southeast Asian (Optional**: may collect as two separate categories - East Asian and Southeast Asian) | Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Taiwanese descent; Filipino, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Thai, Indonesian, other Southeast Asian descent |

| Indigenous*** (First Nations, Métis, Inuk/Inuit) | First Nations, Métis, Inuit descent |

| Latino | Latin American, Hispanic descent |

| Middle Eastern | Arab, Persian, West Asian descent, e.g. Afghan, Egyptian, Iranian, Lebanese, Turkish, Kurdish, etc. |

| South Asian | South Asian descent, e.g. East Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, Indo-Caribbean, etc. |

| White | European descent |

| Another race category | Another race category (Optional: allow write-in response) |

| Prefer not to answer (Optional value) | Permitted only in oral interview processes to record that the question was asked and the respondent chose not to answer. |

Response rule: Respondents may select all that apply.

Notes:

* A separate standard for race categories applies for POI data (Section 7 Standards for Participant Observer Information).

** Organizations may collect ‘East/Southeast Asian’ as two separate categories, with appropriate examples provided, where there is evidence this would improve data quality.

*** If providing examples on the form, then “First Nations, Métis, Inuit” need only be included once.

Rationale

The race categories reflect how people generally understand and use race as a social descriptor in Ontario. These are considered commonly used categories, but individuals may describe their racial backgrounds in ways that are not equivalent to the categories above. Therefore, the open text or “Another race category” option is included.

Some people have more than one racial background. Allowing multiple selection instead of a generic “mixed race” option provides more accurate information.

Guidance

Race categories are used to identify and track the impacts of potential systemic racism, including how individuals may be racialized and may experience inequitable treatment or access to programs, services, and functions as a result.

PSOs choosing to provide an open text response option for “another race category,” should give additional instructions to respondents that they should not to write in “mixed” or “bi-racial” but rather select as many categories as apply.

East Asian and Southeast Asian may be separated into two response options instead of one. This should only be done if the PSO has evidence that presenting them separately is more responsive to clients’ needs and would improve the accuracy of responses.

“Indigenous” refers to people who are indigenous to North America (First Nations, Métis, Inuit), and is included to help with understanding how Indigenous peoples may be racialized as a group. This is distinct from the question about whether an individual self-identifies as First Nations, Métis, and/or Inuit, which is collected separately.

Identifying race categories used in Ontario

The categories in this Standard are the main race categories commonly used as social descriptors in Ontario. They are not based on science or biology but on differences that society has created (i.e. is “socially constructed”). Over time, stereotypes and biases associated with racial categories can function to produce and maintain unequal levels of power between social groups on the basis of perceived differences, often based on physical appearance, with unfair advantages for some and disadvantages for others.

Race is distinct from ethnic origin and religion. For example, “Black” is a racial category that includes people of diverse cultures and histories. “Jamaican,” on the other hand, is an ethnic group with a widely shared heritage, ancestry, historical experience, and nationality. Some Ontarians with Jamaican origins may self-report as White, South Asian, or East/Southeast Asian. Similarly, people from many different racial backgrounds can share the same or similar religion, and people can share a racial background but hold different religious beliefs.

Race categories are distinct from geographic regions. Names of geographic regions are used in this Standard (East/Southeast Asian, Middle Eastern, and South Asian) to refer to groups of people perceived to belong to a racial group with common ancestral origins in that particular region of the world.

Individuals described by some categories, such as “Black,” “East/Southeast Asian,” “South Asian” and “White” may currently live anywhere in the world.

Collection of Race-Related Personal Information

Standard 16. Collecting Personal Information about Religion

PSOs must collect personal information about religion using the question and response rules below to identify and monitor systemic racism and racial disparities in outcomes that people may experience on the basis of religion.

Religion refers to an individual’s self-identification or affiliation with any religious denomination, group, or other religiously defined community or system of belief and/or spiritual faith practices.

PSOs may include examples for the values below, or subcategories as needed, to be responsive and inclusive and help individuals select the appropriate response. However, responses must be mapped to the nine categories below for analyses and reporting under the ARA.

Religion Question and Categories

Question: What is your religion and/or spiritual affiliation? Select all that apply.

Values (valid code list):

- Buddhist

- Christian

- Hindu

- Jewish

- Muslim

- Sikh

- Indigenous Spirituality

- No religion

- Another religion or spiritual affiliation (option to provide open text response)

Optional Value: Prefer not to answer (permitted only in oral interview processes to record that the question was asked and the respondent chose not to answer).

Response Rule: Respondents may select all that apply.

Rationale

People can experience racism based on their religion, or perceived religion, which may lead to unique adverse impacts and unequal outcomes. In addition, there may be differences in experiences of systemic racism within and between religious groups.

Guidance

Where authorized under the regulations, PSOs should consider collecting personal information about religion where there have been human rights complaints or cases involving religious grounds, particularly where racism is an alleged factor.

The OHRC’s Policy on Preventing Discrimination Based on Creed states that religious differences are racialized when they are:

- Ascribed to people based on appearances or outward signs (e.g. visible markers of religion, race, place of origin, language or culture, or dress or comportment);

- Linked to, or associated with, racial difference;

- Treated as fixed and unchanging (naturalized) or in ways that permanently define religious or ethnic groups as the “other” in Ontario;

- Ascribed characteristics or negative stereotypes as uniformly shared by all members of a faith tradition; or

- Presumed to be the sole or primary determinant of a person’s thinking or behaviour.

Islamophobia and antisemitism are examples of how religion can be racialized. People can experience racism not only based on skin colour but also other apparent differences based on perceived characteristics associated with religion.

Islamophobia includes racism, stereotypes, prejudice, fear, or acts of hostility directed at individual Muslims or followers of Islam in general. In addition to individual acts of intolerance and racial profiling, Islamophobia can lead to viewing and treating Muslims as a greater security threat on an institutional, systemic, and societal level. This may result in Muslims being treated unequally, evaluated negatively, and excluded from positions, rights, and opportunities in society and its institutions (see OHRC Policy on Preventing Discrimination Based on Creed).

Antisemitism includes latent or overt hostility, hatred towards, or discrimination directed at individual Jews or the Jewish people for reasons connected to their religion, ethnicity, and cultural, historical, intellectual and religious heritage. Antisemitism can take many forms, ranging from individual acts of discrimination, physical violence, vandalism and hatred, to more organized and systematic efforts, including genocide, to destroy entire communities (see OHRC Policy on Preventing Discrimination Based on Creed).

It is important to understand the complexities and differences in experiences of systemic racism. This may mean examining intersections between race and religion; for example to identify whether Middle Eastern Muslims experience unique barriers compared with non-Muslims, or Muslims who are described as White.

Standard 17. Collecting Personal Information about Ethnic Origin

PSOs must collect personal information about ethnic origin using the question and response rules below to identify and monitor systemic racism and racial disparities in outcomes that people may experience based on ethnic origin.

Ethnic origin refers to a person’s ethnic or cultural origins. Ethnic groups have a common identity, heritage, ancestry, or historical past, often with identifiable cultural, linguistic, and/or religious characteristics.

Ethnic Origin Question and Categories

Question: What is your ethnic or cultural origin(s)?

For example, Canadian, Chinese, East Indian, English, Italian, Filipino, Scottish, Irish, Anishnaabe, Ojibway, Mi'kmaq, Cree, Haudenosaunee, Métis, Inuit, Portuguese, German, Polish, Dutch, French, Jamaican, Pakistani, Iranian, Sri Lankan, Korean, Ukrainian, Lebanese, Guyanese, Somali, Colombian, Jewish, etc.

Values (valid code list): Open text box (specify as many ethnic or cultural origins as applicable) or provide drop-down list of values as reported in Ontario, Census 2016.

Optional Value: Prefer not to answer (permitted only in oral interview processes to record that the question was asked and the respondent chose not to answer).

Response Rule: Respondents may select or write-in more than one ethnic origins.

Rationale

Perceived differences based on ethnic origin may be racialized and lead to adverse impacts and unequal outcomes. In addition, there may be ethnic differences in experiences of systemic racism within and between racial groups.

The examples of ethnic origin set out in the question are provided in order of most commonly reported single ethnic origins in Ontario in the 2016 Census. They include five examples of Indigenous origins, and one from each world region.

Guidance

Personal information collected about ethnic origin is used for the purpose of identifying and monitoring systemic racism and advancing racial equity. Individuals may experience systemic barriers in unique ways on the basis of ethnic origin. Collecting and analyzing this information can help to identify and evaluate the underlying systemic racial barriers more precisely. For example, an accent associated with a particular ethnic origin can be racialized.

Personal information about ethnic origin lawfully collected by PSOs for other purposes may also be used to help identify distinct ethno-cultural needs and to support the development and delivery of culturally responsive programs and services.

3. Protection and management of personal information

Securing Personal Information

Subsection 7(11) of the ARA requires PSOs to take reasonable steps to secure personal information throughout its life cycle; for example, during transmission, storage and disposal (transportation, handling and destruction or transfer to an archive).

Standard 18. Secure Personal Information and Manage Privacy Breaches

PSOs must document and have in place reasonable measures to ensure that:

- Personal information is protected against theft, loss, unauthorized access or use, tampering, disclosure, or destruction; and

- Records (hard copy and electronic) containing personal information are protected against unauthorized copying, modification, or disposal.

PSOs must have in place a privacy breach management and response protocol that documents:

- The steps needed to identify, assess, contain, manage and respond to known or suspected privacy breaches;

- Requirements for third party service providers;

- When it is appropriate to notify affected individuals; and

- When it is appropriate to report a breach to the IPC .

Rationale

Maintaining the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of personal information is necessary to carry out requirements of the ARA , the regulations and the Standards.

This includes protecting against privacy breaches resulting from theft, loss, unauthorized access, use, or disclosure, and unauthorized copying, modification, or disposal. Having clear privacy breach management and response protocols is essential for mitigating harm arising from such incidents.

Guidance

PSOs should develop, document, implement, and maintain security policies and procedures that address obligations under the ARA , the regulations and the Standards, and other relevant legislation, including FIPPA /MFIPPA . This should be done in consultation with the organization’s privacy officer or FIPPA /MFIPPA coordinator and security professionals.

PSOs' security measures should include administrative, technical and physical safeguards (see Appendix B). These measures should cover people, processes and technology and protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of information. In addition, PSOs should identify and address security risks presented by remote access (e.g. use of mobile devices), internet/web applications, and electronic transmission of personal information.

PSOs should also make sure that security measures are appropriate and proportional to the nature of the personal information to be protected by considering the following:

- Sensitivity and amount of personal information;

- Number and nature of people with access to the personal information; and

- Threats and risks associated with the personal information.

Organizations should have protocols for employees, officers, consultants and agents of organizations to identify and report security issues to an accountable manager. They should also implement routine maintenance and updates of database management systems used to store, retrieve, and manage records.

Detailed guidance on security safeguards may be found in the Government of Ontario Information Technology Standards (GO-ITS) related to security.

Privacy breaches can have significant impacts on the individual to whom the information relates. Upon learning about a privacy breach, PSOs should take the following immediate action:

- Implement the organization’s privacy breach protocols;

- Identify the scope of the breach and take action to contain it;

- Identify the individuals whose privacy was breached, and when appropriate, notify them accordingly;

- Inform the IPC of the breach when appropriate, including information about the circumstances; and

- Investigate the causes and take steps to address deficiencies and avoid breaches in the future.

The IPC's guidelines on Preventing and Managing Breaches is a helpful resource.

Secure Storage in Databases

Standard 19. Storage of Personal Information in Electronic Format

PSOs must maintain all personal information collected under the ARA in a secure database that is part of, or can be linked to administrative records.

If the personal information is collected for both the purpose of the ARA and another lawful purpose, it must be maintained in accordance with the privacy and security requirements under applicable legislation (e.g. FIPPA or MFIPPA ).

Rationale

Storage of personal information in a secure database enables the analysis of individual outcomes and long-term trends in order to identify potential systemic racial inequalities.

Guidance

PSOs should make sure that their security measures related to the storage of personal information (including hard copy and electronic, on-site and off-site, third-party service providers) are appropriate and proportional to the nature and sensitivity of the personal information and records to be protected.

If personal information collected under the ARA is kept in a data set that is separate from the administrative data set, a unique pseudonym or identification number can be assigned to each record so that only a designated manager is able to link the data sets as necessary to facilitate analyses.

Limiting Access to Personal Information

Subsection 7(13) of the ARA requires organizations to limit access to personal information to only those individuals who need it in the performance of their duties, in connection with requirements under the ARA , the regulations and the Standards. The ARA prohibits the use of personal information if other information could meet the purpose, and requires that no more personal information be used than is reasonably necessary to meet that purpose (s. 7(8)).

Standard 20. Limit Access on a Need-to-Know Basis

PSOs must determine the level of access to personal information that their employees, officers, consultants, and agents require in the performance of their duties under the ARA , the regulations and the Standards. Access to personal information must be limited according to the determination.

Rationale