Beluga Management Plan

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of Beluga, a species of special concern, return to Ontario.

Management plan prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

June 2013

About the Ontario management plan series

This series presents the collection of management plans that are written for the Province of Ontario and contain possible approaches to manage species of special concern in Ontario. The Province ensures the preparation of the management plans meet its commitments to manage species of special concern under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is a species of special concern?

A species is classified as special concern if it lives in the wild in Ontario, is not endangered or threatened, but may become threatened or endangered due to a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

What is a management plan?

Under the ESA, 2007, a management plan identifies actions that could be taken to ensure, at a minimum, that a species of special concern does not become threatened or endangered. The plan provides detailed information about the current species population and distribution, their habitat requirements and areas of vulnerability. The plan also identifies threats to the species and sets a clear goal, possible strategies, and prioritized activities needed to address the threats.

Management plans are required to be prepared for species of special concern no later than five years of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list as a special concern species.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a management plan a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the plan and the government priorities in taking those actions. The implementation of the management plan depends on the continued cooperation and actions of various sectors, government agencies, communities, conservation organisations, land owners, and individuals.

For more information

To learn more about species of special concern in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Ted (E.R.) Armstrong 2013. Management Plan for the Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) in Ontario. Ontario Management Plan Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 58 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

ISBN 978-1-4606-2028-1(PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Management plans prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec le ministère des Richesses naturelles au 800-667-1940.

Author

Ted (E.R.) Armstrong.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the advice and information generously and graciously provided by many people, including Dr. Ken Abraham (OMNR), Mr. Rod Brook (OMNR), Mr. Chris Chenier (OMNR), Dr. Vince Crichton (formerly with Manitoba Conservation & Water Stewardship), Mr. Chris Debicki (Oceans North Canada), Dr. Steve Ferguson (Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)), Mr. Drikus Gissing (Nunavut Dept. of Environment), Mr. Steve Hookimaw (Attawapiskat), Mr. Mike Hunter (Peawanuck), Ms. Sandra Johnson (OMNR), Ms. Anna Magera (Nunavut Wildlife Management Board), Dr. Martyn Obbard (OMNR), Mr. Dean Phoenix (OMNR), Mr. Gerry Racey (OMNR), Dr. Pierre Richard (formerly with DFO), Mr. Don Sutherland (OMNR), Mr. Bill Watkins (Manitoba Conservation & Water Stewardship), Ms. Kristin Westdal (Oceans North Canada), Ms. Nancy Wilson (OMNR) and the OMNR Library. Ontario Nature provided permission to use a map (Fig. 2), Dr. Rob Foster (Northern Bioscience) assisted with production of a map (Fig. A-2) and Mr. Doug Lowman (OMNR) assisted with geographic name terminology. This plan benefitted substantially from a peer review by OMNR, DFO and the Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board. The assistance of all is gratefully acknowledged and appreciated.

Declaration

The management plan for the Beluga was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This management plan has been prepared for the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and for the many different constituencies that may be involved in managing the species.

The management plan does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and management approaches identified in the plan are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this plan is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the management of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this plan.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario’s Beluga population forms part of the Western Hudson Bay Population and potentially part of the Eastern Hudson Bay Population, which are shared with Manitoba, Nunavut and Quebec. Jurisdictions and co-management agencies1 responsible for the conservation of this species and the management of activities that affect this species include:

- Eeyou Marine Region Wildlife Board

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)2

- Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship

- Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife3

- Nunavut Wildlife Management Board4

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR)

- Ressources naturelles Quebec

Ontario’s formal jurisdictional responsibility is limited to the conservation of Beluga populations and habitat within the jurisdictional boundary of Ontario, which does not include the waters of Hudson Bay or James Bay.

Executive summary

The Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) is a species of small, toothed whale (Odontocete) of Hudson Bay, considered to be a species of special concern under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 in Ontario. This arctic and subarctic species migrates annually from its wintering grounds in the Hudson Strait and elsewhere in eastern Arctic Canada into Hudson Bay. During the summer it is distributed almost continuously along the Hudson Bay and James Bay coasts of Ontario, Manitoba and Quebec. Most of Ontario’s Beluga population is identified as belonging to the Western Hudson Bay Population. This is a large and relatively healthy population that numbers about 50,000 and stretches across the Hudson Bay coast of Ontario, Manitoba and southeastern Nunavut. It is considered by COSEWIC to be a species of special concern. The much smaller Eastern Hudson Bay Population summers along the Quebec coast of eastern Hudson Bay and is considered endangered by COSEWIC. James Bay, which has a healthy and apparently growing Beluga population, appears to be unique in that many of the whales overwinter in the bay. There is some uncertainty as to which population group to assign the James Bay Beluga. None of these populations have been formally listed under the federal Species at Risk Act. For the purposes of this plan, all Beluga in Ontario are assumed to be part of the Western Hudson Bay Population as designated by COSEWIC.

River estuaries are very important summer habitat for Beluga. The whales rely on estuaries for a number of habitat functions which may include foraging, moulting and nursery habitat, thermal advantage and protection from predators. Beluga have high site fidelity to specific estuaries, and return to their place of birth (philopatric). This fidelity appears to be learned and passed down from generation to generation through matrilineal relationships. Because of these characteristics, it may be difficult to recover or re-establish local populations that are severely depleted or extirpated.

While Beluga occur more or less continuously along the Hudson Bay and James Bay coasts of Ontario, there are areas used more consistently and frequented by higher numbers of Beluga. These include the Winisk River and Severn River estuaries, the northwestern shore of James Bay from Cape Henrietta Maria south to the Lakitusaki River, and offshore near Ekwan Point. The Moose River is the only Ontario river for which there are available records of Beluga travelling considerable distances upstream.

Inuit communities have a strong tradition of Beluga harvest. Some Beluga populations outside of Ontario have been seriously depleted by former commercial and ongoing harvest. While no formal indigenous knowledge studies are available, it appears that Ontario’s Cree communities along the Hudson Bay and James Bay coasts do not have the same tradition of Beluga harvest as northern Inuit communities. However, there was some past harvest primarily to feed dog sled teams.

Although still considered healthy, the Western Hudson Bay Population faces a number of potential and growing threats, including harvest elsewhere in its annual range, increased industrial development, natural resource exploration and shipping activity, increases in ambient noise, climate change and pollution.

The management goal of this plan is to ensure that the population status of Beluga in Ontario is maintained or improved to achieve a population state at which natural events and human activities will not threaten the population’s health and persistence.

The Ontario management objectives to achieve this goal are as follows.

- Undertake regular monitoring of the distribution and abundance of the Beluga population in and adjacent to Ontario waters

- Identify and protect high-value Beluga habitat and obtain additional knowledge on Beluga use of Ontario rivers, estuaries and adjacent coastline

- Increase understanding of Indigenous Knowledge on the distribution, abundance, habitat, harvest, trends and status of Beluga in Ontario

- Increase awareness of the presence, conservation status and needs of Beluga in Ontario

1.0 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Beluga

Scientific name: Delphinapterus leucas

SARO List Classification: Special Concern

SARO List History: Special Concern (2004)

COSEWIC Assessment History:

- Western Hudson Bay Population: Special Concern (2004)

- Eastern Hudson Bay Population: Endangered (2004)

SARA Schedule 1: No schedule (no SARA status)

Consultation was conducted on adding these populations to the SARA schedule (DFO 2010a). The Hudson Bay Population of Beluga and 4 other populations were not added to the list of SARA endangered species "in order to further consult with the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board … to ensure that the current decision and future listing decisions are made in full consideration of the views of the Inuit people" (Department of Justice Canada 2012).

Conservation status rankings (NatureServe 2012)

G-rank: G4TNR

N-rank: NNR

S-rank: SNR

The glossary (Section 6.0) provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

2.0 Species information

2.1 Species description and biology

Species description

The Beluga is a medium-sized, highly mobile Odontocete (toothed whale), ranging from 2.6 to 4.5 m in length and weighing up to 1,900 kg (COSEWIC 2004). Adult females are approximately 80% of the adult male’s body length (COSEWIC 2004). Beluga from western Hudson Bay are smaller in comparison to other populations (Richard 1993). The adults are pure white in colour ("Beluga" means "the white one" in Russian), while the calves are grey at birth becoming whiter as they approach sexual maturity (seven years for females, nine for males) (COSEWIC 2004, Culik 2004). Like other arctic cetaceans such as Narwhal (Monodon monoceros) and Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus), Beluga lack a dorsal fin (COSEWIC 2004). This is a possible adaptation to inhabiting ice-covered waters (DFO Canada 2010b). Unlike other cetaceans, the cervical vertebrae of the Beluga are not fused, allowing for movement of the neck and head (Culik 2004). The Beluga and the Narwhal are the sole members of the family Monodontidae.

Species biology

Beluga are social and very gregarious, occurring in small groups and sometimes forming aggregations of several hundred whales. In James Bay, the vast majority of groups contain six or fewer members (Gosselin et al. 2002). This is a migratory species, travelling to different summer aggregation areas and mixing and overlapping in their winter distribution areas in the Hudson Strait, southeast Baffin Island, Ungava Bay and possibly the Labrador coast (COSEWIC 2004). Mating apparently occurs in the wintering area of Hudson Strait in late winter and early spring, followed by a 12.8 to 14.5 month gestation period. Most calving occurs in late spring (mid-June to early July) primarily in offshore areas (COSEWIC 2004). Groups are often segregated by age and sex. Males and females seem to use different migratory routes to summering areas, while mixing and mating during the winter period (Turgeon et al. 2012). Males and females with calves are generally segregated during the summer period.

Being a toothed whale, Beluga are dependent on fish and invertebrates for their diet. Summer feeding is very important to Beluga. They begin the season with very little fat, developing a thick blubber layer by late summer (Huntington 2000, COSEWIC 2004).

2.2 Population and distribution

A circumpolar species, the Beluga is found in the polar regions of Europe, Asia and North America. It is one of at least five species of whale in the Hudson Bay ecosystem (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). It is found throughout the waters of Hudson Bay and James Bay, Nunavut, where it is the most common whale species (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Southern James Bay is the southernmost occurrence of Beluga in the eastern Arctic. Beluga are distributed almost continuously along the Hudson Bay coast in summer, both in Ontario and the adjacent provinces of Manitoba and Quebec (Richard et al. 1990). Richard (1993) describes this as "an unbroken distribution from east to west along the coast of Hudson Bay and James Bay." They appear to be more abundant in July than August (Richard 1993).

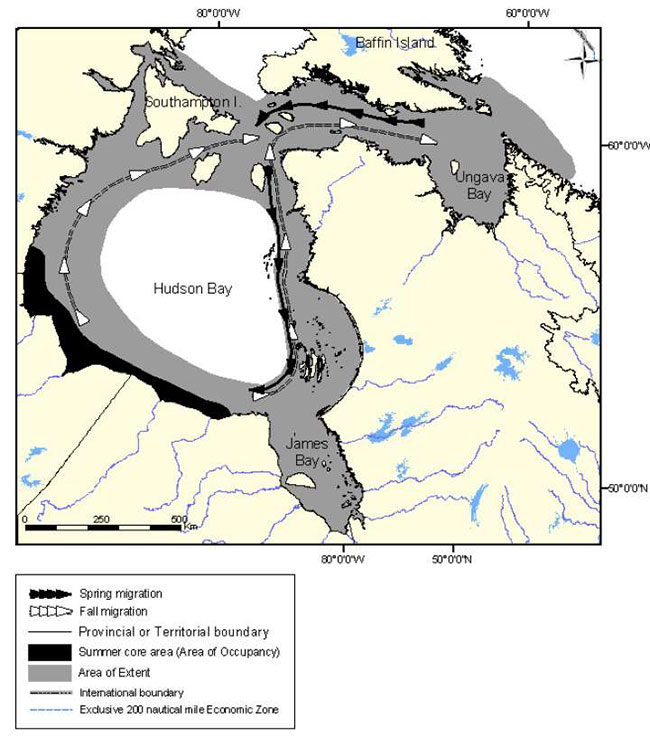

There seems to be distinct populations of Beluga that summer in the Hudson Bay ecosystem, despite their more or less continuous distribution along the coast in the summer and their joint northern wintering area. Beluga along the Ontario coast of both Hudson Bay and James Bay are considered part of the Western Hudson Bay Population (Figure 1), one of seven identified Canadian populations based upon separate (disjunct) summer distributions and genetic differences (COSEWIC 2004). Three of these populations, the Cumberland Sound, Eastern Hudson Bay and Western Hudson Bay (identified as stocks by the author), form a panmictic unit. These populations have a common wintering area, but differing migratory behaviours associated with different summering areas (Colbeck et al. 2012).

There is some uncertainty regarding the relationship between James Bay Beluga and the populations formally recognized by COSEWIC (2004). These animals have been classed differently by different researchers and managers. There may be considerable movement or exchange between the Eastern Hudson Bay Population and the Western Hudson Bay Population in the James Bay area (Bourdages et al. 2002). Until recently it was acknowledged that the relationship between the James Bay Beluga and other populations, their migration route and wintering area were little known (de March and Maiers 2001). For the purposes of harvest management guidance, the Western Hudson Bay Population has been subdivided into western, southern (specific to the Ontario coast of Hudson Bay) and James Bay units (DFO 2009). COSEWIC (2004) considered the James Bay Beluga to be more closely related to the Western Hudson Bay Population than the Eastern Hudson Bay Population. It did not consider the Eastern Hudson Bay Population to extend as far south as James Bay, although the core summer area was identified as coming as far south as the Belcher Islands just north of James Bay. However, in their study of genetic mixture analysis, Turgeon et al. (2009) included the small number of James Bay samples with those from Eastern Hudson Bay. Recent telemetry and genetic studies have indicated that the Beluga of James Bay should be considered a distinct stock and managed separately from other Beluga populations (Gosselin 2005, Postma et al. 2012). The year-round residency of Beluga in James Bay reflects very different migratory behaviour and habitat use patterns than the Eastern Hudson Bay Population, suggesting very little overlap between these groups throughout the year (Bailleul et al. 2012a).

Based upon the populations recognized by COSEWIC (2004), for the purposes of this management plan all of the Beluga of Ontario are assumed to belong to the Western Hudson Bay Population. Because of factors discussed elsewhere in this plan, it is recognized that Beluga residing in James Bay may actually form a distinct population rather than being part of the Western Hudson Bay Population. It is anticipated that this relationship will be clarified by the Designatable Unit evaluation process currently underway (COSEWIC 2013).

The Western Hudson Bay Population has the highest population of any Canadian Beluga population. A 2004 study estimated 50,000 Beluga based upon a correction for animals underwater at the time of the survey (COSEWIC 2004). There were estimated to be 7,074 Beluga distributed along the Ontario coastline of Hudson Bay in 2004 (Richard 2005). This is significantly greater than the minimum count of 1,299 in 1987 (Richard et al. 1990) and the approximately 2,500 animals estimated in the 1990's by Wilson (1994). This may not necessarily reflect a population increase, as these earlier surveys did not account for animals that may have been underwater (Richard 2005). The extent of occurrence and area of occupancy are considered stable for this population (COSEWIC 2004).

Figure 1. Extent of occurrence and summer core area for the Western Hudson Bay population of Beluga (from COSEWIC 2004, as amended).5

Details on the number and distribution of the Western Hudson Bay population is described by COSEWIC (2004) primarily for the Manitoba coastline. Beluga are found continuously along the entire Ontario coastline of Hudson Bay and James Bay during the summer months (Wilson 1994)(Figure 2). Summer core habitat (area of occupancy) for the Western Hudson Bay population has been identified as the Hudson Bay coastal waters from the Winisk River westward, including the entire Manitoba coastline, to the southeastern tip of Nunavut (Figure 1, COSEWIC 2004). Most observations of Beluga are in near-shore areas. During July 1987 reconnaissance surveys of the Hudson Bay coast from the Kaskattama River (just west of the ON-MB border) to Cape Henrietta Maria and back, 1,299 Beluga were seen along a three km in-shore transect while only 20 were seen along a transect 28 km offshore (Richard et al. 1990).

Figure 2. Distribution of Beluga along the Ontario coastline of Hudson Bay and James Bay (from Wilson 1994) (permission courtesy of Ontario Nature).

Ontario Beluga records have not yet been entered into the provincial NHIC database because of other species at risk priorities (D. Sutherland, pers. comm. 2012), and because offshore records are in Nunavut. NatureServe recognizes several types of Element Occurrences (EOs) for Beluga, including moulting areas, nonbreeding areas, foraging, concentration areas and breeding areas (D. Sutherland, pers. comm. 2012). It is anticipated that the main EOs that will eventually be entered in the NHIC database for Ontario will be the estuaries of the Severn, Winisk, Attawapiskat, Albany and Moose rivers, where the species is seen regularly (D. Sutherland, pers. comm. 2012).

Beluga are found in the river mouths, estuaries and lower rivers of the several large rivers flowing into Hudson Bay and James Bay, arriving in early July (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). In Hudson Bay the largest concentrations are found near the major river mouths (Johnston 1961). Obbard and Sutherland (2005) reported "during the ice-free period between mid-July and early September, Beluga occurs regularly in Ontario in the coastal/nearshore waters of Hudson Bay and James Bay. Pods containing males, females and calves congregate regularly in summer in the estuaries of the larger rivers entering Hudson Bay (Severn River, Winisk River and possibly the Sutton River) and James Bay (Moose River, Attawapiskat River and Albany River) primarily to moult."

In an effort to more specifically identify important Beluga habitat in Ontario, site-specific Beluga observations were compiled from OMNR staff observations and published sources. The initial compilation is appended in Table A-1, referencing the geographic locations identified in Figure A-2, and clearly shows the value of compiling even incidental Beluga observations. As has been reported in many sources, Beluga are more or less continuously distributed along the Hudson Bay and James Bay coasts of Ontario in the summer. However, it is also clear that some sites are more important than others to the local Beluga population.

The Winisk River and Severn River estuaries are the Ontario estuaries with the consistently highest densities of Beluga during the summer months (Richard 1993). In excess of 100 Beluga are commonly seen in the estuaries of both rivers throughout the summer, far more than for any other Ontario rivers (Table A-1). However, in comparison these appear to be less significant to the Western Hudson Bay Population than the Seal, Churchill and Nelson rivers of Manitoba (COSEWIC 2004, Stewart and Lockhart 2005, Oceans North Canada 2013).

Other river estuaries are typically frequented by smaller numbers of whales, typically varying from single animals to small groups of up to 5 to 10 and occasionally more. The largest number of Beluga observations has been made at the Moose River, where group size ranges from one to six (Table A-1).

Nearshore and offshore areas are also used, documented primarily for James Bay. There are some shoreline sites, such as Longridge Point, where the species comes close to shore and has been observed in some numbers but may not be as regularly present (D. Sutherland, pers. comm. 2012). The highest and most consistent offshore concentration of Beluga in the summer appears to occur northwest of Akimiski Island and south of Cape Henrietta Maria, along the northwestern coast of James Bay, where the animals are found in shallow turbid water close to the shore (Kingsley 2000, Gosselin et al. 2002, Hammill et al. 2004, Stewart and Lockhart 2005). The tabulated observations also confirmed that near-shore areas along the western shore of James Bay from Cape Henrietta Maria south to the Lakitusaki River and Ekwan Point area are often frequented by larger numbers of Beluga. OMNR (1985) identified a number of coastal areas with "Beluga Whale sightings" as wildlife concentration areas. These include the East Pen Islands and the Severn, Winisk, Sutton/ Kinusheo, Attawapiskat, Kapiskau, Albany and Moose rivers.

It is interesting to note that there are very few reports of Beluga from Hannah Bay or the Harricana River since the 1800s, when Hudson Bay Company staff expressed interest in the possibility of establishing small whaling stations in the vicinity (Reeves and Mitchell 1987). It is not known if such a facility was established, and if it was, what the impact on the local whale population may have been. Field staff who spent considerable time in the area during the 1970s did not observe any Beluga in Hannah Bay, although they were observed elsewhere (R. Stitt, pers. comm. to C. Chenier 2013).

There is a significant knowledge gap about the migration patterns of Eastern and Western Hudson Bay Beluga populations, and how that affects annual fluctuations in number, especially in areas such as James Bay (Bourdages et al. 2002). Beluga are widely distributed in James Bay in the summer, occurring out in the bay and along both the Ontario and Quebec coastlines (Smith and Hammill 1986). However, there are some uncertainties regarding Beluga in northwestern James Bay that may overlap between animals that continue on into James Bay and those that stay along the Hudson Bay coast.

The Beluga population in James Bay appears to have increased significantly in recent decades. Smith and Hammill (1986) estimated that 740 to 1,960 Beluga could be found in James Bay throughout the summer months. The population seems to have increased greatly between 1985 and 2001 (Bourdages et al. 2002, Gosselin et al. 2002), with estimates of 3,141 in 1993 (Kingsley 2000), 7,901 in 2001 (Hammill et al. 2004) and 3,998 in 2004 (Gosselin 2005). This trend has continued in recent years, with a 2011 estimate of 14,967 (DFO 2013a). This compares with a much lower estimate of 3,351 Beluga for the Eastern Hudson Bay Population (DFO 2013a).

Beluga in the Western Hudson Bay Population typically follow a consistent annual clockwise migration movement within Hudson Bay. They arrive in major riverine estuaries in mid-June as soon as open water leads are available, and increase in numbers through late July (see Figure 1)(COSEWIC 2004). Beluga are found along the entire Ontario coastline during the summer (Johnston 1961, Wilson 1994). They begin to move northward away from the Ontario coast near the end of August (Johnston 1961). They then begin a northward and eastward migration in early September, and are thought to move as far as the Hudson Strait and perhaps even the Labrador coast where they winter (COSEWIC 2004).

Not all Beluga appear to follow this typical clockwise northeastward migration to the Hudson Strait. Of 15 Beluga radio-tagged at the Nelson River estuary in Manitoba in the summers of 2002-2005, five were females with a known calf associated with them. Of these three made significant movements eastward along the Ontario coastline.

- One female in the company of both a calf and a juvenile when tagged moved eastward along the Ontario coast as far as the Winisk River area, then retraced its path to the west and subsequently moved north and northeastward to the Hudson Strait (Smith 2007, Smith et al. 2007)

- A second female Beluga with a calf moved eastward along the Ontario coast as far as Cape Henrietta Maria, then continued moving through the northeastern quadrant of James Bay. It continued northward along the east coast of Hudson Bay and the Belcher Islands before moving on to the Hudson Strait (Smith 2007, Smith et al. 2007). The latter part of this route was consistent with the traditional northern fall migration of the Eastern Hudson Bay Population (COSEWIC 2004, Stewart and Lockhart 2005)

- A third female Beluga with a calf moved in late August as far as the mouth of James Bay. It then moved northward through Hudson Bay, west of the Belcher Islands, to the Hudson Strait (Smith 2007, Smith et al. 2007)

A fourth female with a calf made a short journey eastward from the Nelson River estuary, briefly straying into waters adjacent to Ontario before returning to the estuary.

2.3 Habitat requirements

Beluga are found throughout the coastal waters of Hudson Bay and James Bay. They appear to prefer shallow coastal areas and river mouths. Beluga are the only arctic and subarctic cetacean to use river estuaries, arriving shortly after ice break-up and spending summers in coastal and offshore areas (COSEWIC 2004, Culik 2004). Ice leads appear to provide important spring migration routes (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Beluga often appear in ice-free estuaries several weeks before the sea ice in more open areas of the bay has broken up (COSEWIC 2004). All Canadian Beluga populations are centered around estuaries during the summer (open water) months (COSEWIC 2004). Behavioural and telemetry studies of Belugas at estuaries revealed that they are philopatric, returning to the site of their own birth with high site fidelity (COSEWIC 2004, Turgeon et al. 2012).

Large groups of Beluga are often present at Ontario’s river estuaries (OMNR 1985, Wilson 1994, COSEWIC 2004). There are a number of hypothesis as to why estuaries are important to Beluga including feeding, moulting and nursery habitat, thermal advantage particularly for calves, and neonate survival and protection from predators (Richard 1993, North/South Consultants Inc. and Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre 2003, COSEWIC 2004, Oceans North Canada 2013, Stewart and Lockhart 2005, Smith 2007). Beluga may be attracted to the combination of nearshore gravel beds and warm, low-salinity water, which may help moulting (Frost et al. 1993). Estuarine habitat is typically characterized by relatively shallow, brackish water, and sandy or muddy substrates (DFO 2013b). Beluga in Cook Inlet, Alaska select summer estuarine habitats based on fish availability, tidal flats and sandy substrates and few human-caused disturbances (Goetz et al. 2012). Beluga appear to prefer the freshwater-saltwater mixing zone of the estuary over more freshwater areas, remaining further offshore during wet years when the plume extends further out (Smith et al. 2007).

Beluga in the Churchill River estuary spend virtually the entire summer in shallow coastal waters (COSEWIC 2004). It is likely that Beluga summering near Ontario estuaries do the same. Beluga also occur along marine coastal waters and offshore areas surrounding these estuaries for variable periods of time (Smith et al. 2007). Beluga in James Bay are noted for returning persistently from offshore to nearshore areas (Smith and Hammill 1986). Beluga females with calves may be more strongly associated with estuaries than adult males (Lesage and Doidge 2005).

There is limited information on the diet of Beluga in and adjacent to the Ontario waters of Hudson Bay and James Bay, and only a few samples from elsewhere in western Hudson Bay. Three Ontario Beluga specimens examined in 1961 all had empty stomachs (Johnston 1961). Capelin (Mallotus villosus), estuarine fish, squid (Teuthida), decapod crustaceans (Decapoda) and annelid worms (Nereis sp.) have been identified as important prey items for Beluga summering in southern Hudson Bay (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Capelin was considered the primary summer prey of Beluga feeding in the Churchill River area (Doan and Douglas 1953). Squid and Arctic Char (Salvelinus alpinus) were also important prey items. In and adjacent to Ontario waters, Capelin and sea-run Brook Trout (S. fontinalis) were considered likely important prey items that Beluga would enter estuaries of larger rivers to feed on (Johnston 1961). American Sand Lance (Ammodytes americanus) and Lake Whitefish (Coregonus clupeaformis) are also be important prey species in southern Hudson Bay (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Lake Whitefish are more common in the relatively dilute saline waters of the estuaries and coasts of James Bay and southeastern Hudson Bay (Stewart and Lockhart 2005) and whitefish were found in the stomachs of a small sample of four Beluga from the Nelson River estuary in the early 1900s (Richard 1993). Other identified prey items include riverine fish such as Cisco (Leucichthys artedi) and Northern Pike (Esox lucius), marine worms and squid (Culik 2004).

Some reports suggest that Beluga rarely feed on schooling fish while in the estuaries, but rely primarily on invertebrates such as shrimp, squid and marine worms (DFO 2013b). Smith (2007) believed that most Beluga feeding behaviour in estuaries was probably opportunistic, although they may follow prey in and out of the estuary. In Ontario waters, groups of 100 to150 Beluga have been observed entering the estuaries of some of the larger rivers on the rising tide, apparently in pursuit of fish (Johnston 1961). Beluga in the Nelson River estuary tended to enter the river on the rising tide and return during slack tide (Smith et al. 2007).

In the lower Churchill River, at least 200 Beluga were estimated to move at least 1.6 km upriver in July 1949 (Doan and Douglas 1953). There is little documentation on how far upriver Beluga will move in Ontario waters. Small aggregations of Beluga move at least 14 to 25 km upstream in the Moose River on the high tide and are regularly seen most years (Table A-1, Appendix 1; K. Abraham pers. comm. 2013, C. Chenier pers. comm. 2013). There are few reports of Beluga moving upstream beyond the estuary in any other Ontario river, although they do move up the Attawaspikat River at least as far as the community of Attawaspikat (S. Hookimaw, pers. comm. 2013). While this may be partially because of the greater number of potential observers in the area, it may also reflect unique characteristics of the Moose River. Beluga use of rivers in Ontario is likely related to water depth, with Beluga using the estuaries and lower sections of larger, deeper rivers and avoiding the shallower rivers (C. Chenier, pers. comm. 2013).

As an arctic and subarctic marine mammal, winter ice is an important component of the Beluga’s annual habitat. They have several arctic adaptations, including a thick blubber layer, thick skin, no dorsal fin and a dorsal ridge which allows them to break ice up to 20 cm thick to create breathing holes (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Ice conditions (e.g. the quality, timing and extent of sea ice cover) have an important influence on their seasonal distribution and movements. The amount and location of heavy pack ice and landfast ice, as well as the presence and location of open water leads, can affect survival, vulnerability to predators, distribution and reproductive success (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Ice leads can be important in determining early spring migration routes (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Ice edges are considered to be highly productive components of the arctic environment (Asselin et al. 2012). Spring surveys of Beluga along ice edges at Franklin Bay showed directed travel and diving near and under the ice, suggesting that higher prey densities at the ice edge may attract Beluga to these areas (Asselin et al. 2012).

Winter distribution and movements are limited by heavy pack ice or landfast ice where breathing holes cannot be maintained (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). Winter habitat is dependent on the continued availability of areas of shifting ice where open water remains accessible (Stewart and Lockhart 2005). During the winter Beluga are found in loose pack ice or polynya with 40 to 80% ice cover. They are generally not seen in ice-free waters away from the pack ice (Richard 1993, COSEWIC 2004). These polynya are of critical importance to several Arctic cetaceans including Beluga (Elliott and Simmonds 2007). Although most Beluga are believed to move out of Hudson Bay to overwinter in the Hudson Strait area, there are occasional winter reports of Beluga in the bay. Approximately 50 Beluga in groups of 6 to 20, both adults and young, were observed on January 15, 1987, 136 km NNE of Winisk in Hudson Bay along an extensive lead beside open water (OMNR, unpubl. data). Johnston (1961) similarly noted that winter observations of Beluga in Hudson Bay are rare but reportedly do occur along the open water of the flow ridge and pressure ridges, apparently stragglers cut off by the pack ice. Beluga in North Water, Baffin Bay, an arctic area where Beluga do not typically overwinter, were also located in narrow recurrent leads along the edge of land-fast ice (Finley and Renaud 1980).

Overwintering of Beluga occurs in James Bay, where the whales take advantage of small ice-free areas or areas of shifting ice (Jonkel 1969, Hammill et al. 2004, Postma et al. 2012). All 12 eastern James Bay Beluga outfitted with satellite transmitters that lasted beyond the summer months stayed within James Bay throughout the winter (Postma et al. 2012). All but three remained close to their tagging site (Postma et al. 2012). The presence of polynya and abundant food resources may make it possible for Beluga to remain year-round in eastern James Bay. While most reports of overwintering Beluga are from the eastern portion of James Bay, a single Beluga was observed in an ice lead off Northbluff Point on the Ontario side of James Bay in mid-February 1984 (Table A-1). Ten Beluga were sighted off the mouth of the Kapiskau River along the western coast of James Bay in early April 1975 (Table A-1). Beluga have also been reported travelling up the Moose River in early May (Table A-1; C. Chenier, pers. comm. 2013), much earlier than when migrating Beluga regularly appear in Hudson Bay estuaries in mid June (COSEWIC 2004). These observations are consistent with reports of Beluga overwintering in James Bay.

2.4 Characteristics contributing to vulnerability of species

Beluga are long-lived, have delayed sexual maturity, and have a low reproductive rate. All of these factors can limit the ability of a population to recover if depleted (DFO 2012a).

Estuaries are an important feature of summer Beluga habitat (Fraker et al. 1979, Smith 2007). The riverine estuaries of Hudson Bay are an extremely important component of summer Beluga habitat that must be maintained in a healthy condition. Beluga, particularly females with calves, are philopatric to specific estuaries, being "extremely tenacious in their occupation of their traditional centres of aggregation, even in the face of continued disturbance and threat of being killed" (COSEWIC 2004). These distinct summering areas are likely maintained culturally through maternal lines and defined migration routes (Turgeon et al. 2012). Other female relatives also appear to play a role in maintaining the social structure that allows for the learning of migration routes (Colbeck et al. 2012). This strong fidelity to summering habitat has major implications for recovery, as it may impede recolonization extirpated or depleted sites and limiting dispersal among populations (Colbeck et al. 2012, Turgeon et al. 2012). If use of these estuaries were lost due to overharvest or habitat change, "cultural conservation" would likely limit their recolonization because of this fidelity to feeding grounds and the loss of cultural memory of these grounds and the associated migration route (Colbeck et al. 2012, DFO 2011). This philopatry can make Belugas extremely vulnerable to overexploitation, and has led to local extirpations from a combination of past commercial and subsistence harvest (COSEWIC 2004). There are a number of instances of formerly significant areas of summer abundance where Beluga were heavily hunted in the past and have not re-established or no longer exist in significant numbers (COSEWIC 2004, Turgeon et al. 2012). This seems to apply particularly to smaller river estuaries where commercial Hudson’s Bay Company fisheries previously took place (COSEWIC 2004).

The potential for entrapment in the ice is an ongoing concern for Beluga wintering in northern areas. Entrapment typically occurs during periods of cold weather when ice forms quickly; subsequent mortality can occur from predation, hunting or exhaustion (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002, NAMMCO 2005). Beluga that winter in Hudson Bay and James Bay rather than migrating to the more open ice conditions of the Hudson Strait regularly face potential entrapment (Stewart and Lockhart 2005).

Beluga can be very vulnerable to predation under certain environmental conditions. The main predators of Beluga are Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) and Polar Bears (Ursus maritimus) (Smith and Sjare 1990, Ferguson et al. 2012). They are particularly vulnerable to Polar Bear predation when they become entrapped in ice or stranded along shorelines at high tide. Bears will also hunt them along the edges of ice floes (Freeman 1973, Smith and Sjare 1990, COSEWIC 2004). In one documented case approximately 100 of 170 Beluga entrapped in Lancaster Sound in the High Arctic were killed by Polar Bear (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2002). In a recent instance, approximately 20 Beluga were killed by an estimated eight Polar Bears when they became trapped in the ice just south of Sanikiluaq in southeastern Hudson Bay in February 2013 (CBC News North 2013a, CBC News North 2013b). Most of the Beluga killed appeared to be juveniles (S. Ferguson, pers. comm. 2013).

Killer Whales prey upon Beluga throughout most of the eastern Canadian Arctic (COSEWIC 2004). Until recently, much of Hudson Bay was considered inaccessible to Killer Whales because of an ice "choke point" at Hudson Strait (Higdon and Ferguson 2009). Local Inuit have observed Killer Whales attacking Beluga in the Hudson Strait and elsewhere in the Hudson Bay ecosystem (Higdon and Ferguson 2009).

3.0 Threats

Natural ecosystems are continually evolving in response to a variety of forces and factors. But they are limited in their ability to adapt to rapid change, such as that introduced through human activities. Humans sometimes disrupt and degrade biodiversity through habitat loss, introduction of invasive species, population growth, pollution, unsustainable use and climate change. Our growing population combined with our rising levels of resource consumption can threaten biodiversity (OBC, 2011). Recently, an assessment of pressures on Ontario’s biodiversity showed that many threats are increasing (OBC, 2010b).

A number of threats have been identified as currently or potentially facing Beluga in and adjacent to Ontario waters. These include unsustainable use (e.g. excessive harvest, ecotourism disturbance), habitat loss or disturbance (e.g. increased industrial development, natural resource exploration and shipping activity, and related increases in ambient noise), climate change, and environmental contaminants (COSEWIC 2004, Culik 2004). Nunavik community residents have identified a similar threats to the Eastern Hudson Bay Population (DFO 2001).

Unsustainable use

Beluga can be very vulnerable to hunting. The St. Lawrence Estuary Population was drastically reduced by hunting to the point where a genetic bottleneck was apparently reached (DFO 2012a). Northern Beluga populations are heavily harvested by Inuit from an estimated 20 northern communities in Nunavut and northern Quebec (Richard et al. 1990, Lesage and Doidge 2005, Dawson 2012). The Eastern Hudson Bay Population, with its core summering area along the eastern coast of Hudson Bay from the Belcher Islands northward, is considered endangered and continued human harvest is one of its major threats (COSEWIC 2004). This population declined by almost 50% between the early 1990s and early 2000s (Hammill et al. 2004). At the time of writing of the COSEWIC status report this population was thought to have the potential for extirpation within a matter of decades (COSEWIC 2004). With more recent harvest reductions, this population has probably been stable over the past few years (Doniol-Valcroze et al. 2011).

While one of the major threats to the Eastern Hudson Bay Population of Beluga appears to be overharvest (Lesage and Doidge 2005), this does not yet appear to be a major issue for the Western Hudson Bay Population in Ontario. Harvest of Beluga appears to be primarily a tradition of northern Inuit and Nunavik cultures (Stewart and Lockhart 2005), and there is very little indication that Ontario’s coastal Cree currently harvest Beluga to any significant extent, if at all. There was some level of harvest in the past, with accounts of coastal Cree harvesting Beluga by both netting and shooting, primarily to provide food for dog sled teams (Johnston 1961, M. Hunter pers. comm. 2012)(see 5.2).

However the Western Hudson Bay Population is under considerable and increasing hunting pressure elsewhere in its range (COSEWIC 2004). Some consider harvest to be the greatest threat to this population (ECO 2012a). A substantial amount of the harvest of the Western Hudson Bay Population is thought to take place in the area of southeast Baffin Island and the Hudson Strait, where the various populations of Hudson Bay Beluga mix and overlap in winter (COSEWIC 2004, DFO 2011). Guidance for Nunavummiut harvesting of the Western Hudson Bay Population cautions that consideration must also be given to potential Nunavik harvest of this population, however there is no similar mention of potential Cree harvest in Ontario (DFO 2009). The estimated harvest of Beluga from the Western Hudson Bay Population in 2003 was 764, an increase from previous years (COSEWIC 2004).

Because of the depleted population and limited harvest limits within the Eastern Hudson Bay Population, Stewart and Lockhart (2005) note that the Inuit demand for maqtaq cannot be satisfied locally. It is subsequently being imported from the Western Hudson Bay Population, thereby increasing harvest on Beluga summering in that range. DFO (2002) recommends that the status of adjacent populations be considered before they are harvested to replace harvest of Eastern Hudson Bay populations.

There is an allowable harvest quota of 21 Beluga for the northeastern quadrant of James Bay and Long Island just north of James Bay (DFO 2010c), although these are not considered traditional Inuit hunting grounds (Kishigami 2005). Nunavik hunters reported harvesting between one and seven Beluga annually in eastern James Bay (Lesage and Doidge 2005). There may be some harvesting of Beluga during the winter in James Bay by Sanikiluaq hunters, but this has not been confirmed (DFO 2009). Recent media reports indicate a harvest of 70 entrapped Beluga in the winter of 2013 approximately 100 km southeast of the community, in southeastern Hudson Bay just north of James Bay (CBC News North 2013b).

Ecotourism of marine mammals is generally seen as a positive influence. It provides alternate income for indigenous peoples without killing animals, and increases awareness of the importance of conservation. However it is not always a benign activity (Marsh et al. 2011). Inuit observations suggest that Beluga may be displaced by increased noise from motorboat use (Huntington 2000, Kilabuk 1998), while Richard (1993) reported that the Beluga in the Churchill River appeared to have adapted to the boat traffic associated with whale-watching tours. There can be some conflict between nature-based tourism and Beluga hunting in the Canadian western Arctic (Dressler et al. 2001), which is less likely to occur in southern Hudson Bay due to the much lower incidence of harvest. Beluga watching is promoted for the Churchill, Manitoba area (Travel Manitoba 2012), and is increasing (Brennen 2007). It is also offered on a smaller scale for James Bay (i.e. Moosonee). The potential for ecotourism opportunities for Beluga in the Ontario waters of Hudson Bay and James Bay appears to be limited, and it is not thought to be a significant impact. Amendments to the Marine Mammal Regulations have been proposed to provide a regulatory framework to manage marine mammal watching activities (Government of Canada 2012).

Habitat loss

While the Hudson Bay and James Bay ecosystem is relatively remote and undisturbed, it does face a number of increasing developments and threats due to industrial activity and related shipping activity in the north.

Hydro-electric development in Hudson Bay has been identified as a major threat to the Beluga (Jefferson et al. 2012). Future hydroelectric development projects could alter habitat through changes in river flow regimes and subsequent seasonal freshwater plumes, which may affect the summer habitat functions attracting Beluga (Richard 1993, COSEWIC 2004, Obbard and Sutherland 2005). This effect apparently has not yet been seen in northern Manitoba (COSEWIC 2004), but may have been a factor in reducing Beluga habitat quality in northern Quebec (Brennen 2007). It is speculated that the impact from the major hydro-electric developments in eastern James Bay may have been more significant on Beluga if the population had not already been severely depleted by overexploitation (Brennen 2007). Potential impacts of hydro-electric developments include the direct effects of changes in water temperature and river discharge on Beluga habitat use, and the indirect effects of changes in water temperature, sedimentation, river discharge, water chemistry and water flow blockage on forage fish and invertebrates (Lawrence et al. 1992). A qualitative assessment of impacts of hydro-electric development on the Nelson River in Manitoba concluded that changes in physical and chemical conditions of the river would not have a significant impact on Beluga populations, while also recognizing that further research is needed (Lawrence et al. 1992).

In addition to habitat loss or degradation, Beluga may be affected by increased industrial or exploration activity. While not all potential activities can be identified, a few examples help to illustrate the need for caution. Increased shipping activity can impact Beluga in a number of ways, including displacement and stress from ships' traffic and noise, and an elevated risk of fuel spills and other pollution (Brennen 2007). Beluga are also very susceptible to the noise of ocean vessels. Modeling suggests that icebreaker noise may be audible to Beluga 35 to 78 km away, mask Beluga communications within a range of 14 to 71 km and cause temporary hearing damage within 1 to 4 km (Erbe and Farmer 2000). Nunavik communities have expressed concerns that increasing ship noise may affect Beluga, especially in nearshore areas (DFO 2011). Beluga respond more negatively to sudden changes in sound level than continuous sound; most Beluga responded to the noise from oil drilling platforms by moving away (Awbrey and Stewart 1983). Beluga apparently respond to construction noise, such as pile-driving, with a reduction in vocalizations, which can have an effect on social behaviour, group formation and foraging success (Kendall 2010). Underwater seismic exploration has a significant negative impact on Narwhal, potentially leading to delayed winter migration and subsequent ice entrapment (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013. Similar concerns may exist for Beluga (Heide-Jørgensen et al. 2013).

Climate change

Climate change is a concern and potential threat to many marine mammals, and is expected to be most severe at high (i.e. arctic) latitudes. Marine mammal species that have a very limited range are particularly sensitive, including those for which sea ice is an important part of their habitat, such as Beluga (Simmonds and Isaac 2007). Brennen (2007) proposed the use of the Beluga as a biological indicator of a healthy arctic environment through the integration of climatic and ecological information.

Climate change could also have a significant indirect effect through the decline in sea ice, allowing more access for Killer Whales. The Hudson Strait was traditionally considered a sea ice "choke point" that prevented Killer Whale access to Hudson Bay (Higdon and Ferguson 2009). This "choke point" apparently opened up approximately 50 years ago, allowing increased Killer Whale access to the Hudson Bay ecosystem (Higdon and Ferguson 2009). Less sea ice has led to increased Killer Whale sightings, suggesting that Killer Whales are increasing their distribution as more open water appears (Higdon and Ferguson 2009). Predation on Belugas may increase significantly if the Killer Whale becomes a more dominant predator within the Hudson Bay ecosystem in the future. This could lead to Killer Whale replacing Polar Bear as top predator. Ontario’s Environmental Commissioner has recognized climate change, and the resultant potential increases in Killer Whale abundance and distribution, as a potential threat to Ontario’s Beluga population (ECO 2012b).

Climate change could also affect estuarine habitat used by Beluga, as a result of potentially more erratic precipitation patterns and increased river outflows (Smith et al. 2007). Changes in water temperature caused by a warming climate could alter Beluga migration patterns (Bailleul et al. 2012b). Later departures from summering areas may become more typical as surface water temperatures increase (Bailleul et al. 2012b).

Climate change may also lead to increased shipping traffic in both the wintering grounds and summer habitat, resulting in increases in underwater noise and disturbance to Beluga (see previous section).

The Government of Manitoba will be supporting research into the potential impact of climate change on chronic stress levels of Western Hudson Bay Belugas (Government of Manitoba 2011).

Pollution

Pesticide and other chemical contamination is a concern for Beluga, given its trophic position as a top predator. The major organochlorine compounds that have been detected in Beluga blubber are PCBs and DDT and its metabolites (Brennen 2007). Beluga in the Western Hudson Bay population (noted as South Hudson Bay for this source) have been shown to have high levels of both PCBs and DDT but levels are considerably lower than they are for the highly contaminated Beluga of the St. Lawrence estuary (Brennen 2007). While Beluga in the Western Hudson Bay population have average DDT levels that are only 14% of those of St. Lawrence River Beluga, they are the second highest of 10 sampled global locations. The Western Hudson Bay Population had 1.6 times the average DDT levels of the next most contaminated population, and over 8 times the average DDT levels of the least contaminated population from Cook Inlet, Alaska (Brennen 2007).

There may also be a concern with the release of pollutants such as methylmercury resulting from the creation of hydro-electric reservoirs (Richard 1993).

4.0 Management

4.1 Goal and objectives

Management goal

There are many different factors that can be incorporated into a recovery goal for Beluga. Landry and Simon (2005) discussed many elements and approaches that can be considered in establishing a recovery goal for Beluga populations. For depleted populations, a recovered population that is 70% of the historic (pre-commercial exploitation) population size is considered an appropriate recovery goal to reflect the Beluga’s life history characteristics (DFO 2005). The Western Hudson Bay Population, which comprises at least the vast majority of Ontario’s Beluga range, is still relatively healthy and robust, and the James Bay Beluga numbers appear to be healthy and growing. This means the management goal can focus on maintaining the population by eliminating or avoiding threats, rather than on trying to reverse population trends to recover the species.

The management goal of this plan is to ensure that the population status of Beluga in Ontario is maintained or improved to achieve a population state at which natural events and human activities will not threaten the population’s health and persistence.

As this population of this species in Ontario is shared with a number of Canadian jurisdictions, it is recognized that achievement of this goal will require inter-jurisdictional collaboration and cooperation on several fronts.

Management objectives

Achieving this goal depends on the accomplishment of a number of key Ontario management objectives (Table 1). OMNR will involve other jurisdictions and organizations in the implementation of these objectives where feasible.

Table 1. Management objectives for the conservation and recovery of Beluga in Ontario.

| Number | Management Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Undertake regular monitoring of the distribution and abundance of the Beluga population in and adjacent to Ontario waters. |

| 2 | Identify and protect high-value Beluga habitat, and obtain additional knowledge on Beluga use of Ontario rivers, estuaries and adjacent coastline. |

| 3 | Increase understanding of Indigenous Knowledge on the distribution, abundance, habitat, harvest, trends and status of Beluga in Ontario. |

| 4 | Increase awareness of the presence, conservation status and needs of Beluga in Ontario. |

4.2 Management actions completed or underway

Ontario’s Beluga are periodically monitored as part of the broader Western Hudson Bay Population through surveys conducted by DFO. The most recent comprehensive survey was conducted in 2004 (Richard 2005). At times, the Western Hudson Bay and James Bay populations have been surveyed independently (e.g. Gosselin 2005, Kingsley 2000, Richard 2005, Smith and Hammill 1986).

The harvest pressure on the Western Hudson Bay population is considered sustainable but increasing (COSEWIC 2004). No harvest limits or management plans are in place within the summering range (COSEWIC 2004) but harvest does occur in other jurisdictions and harvest guidance is in place (DFO 2009). Harvest management guidance and protocols are in place for more imperilled populations of Beluga within Hudson Bay (e.g. DFO 2010c).

A joint 3-year satellite telemetry study involving Oceans North Canada, DFO and Manitoba Conservation is underway to study the movements and habitat use of Beluga in the major river estuaries of Hudson Bay in Manitoba (Paul 2013). The whales are part of the same population as those in Ontario and although it is taking place in Manitoba, such studies can provide important information on whale habitat use and movements in Ontario (e.g. Smith 2007, Smith et al. 2007).

4.3 Management plan approaches for action

In the consultation on whether or not to list the Western Hudson Bay Population under the federal Species at Risk Act, DFO (2010a) identified a number of measures to be implemented if this population of Beluga was listed federally as a species of Special Concern, including:

- develop a Management Plan with partners

- provide guidance for non-consumptive activities such as tourism and hydro-electric development; and

- create recommendations on protective measures that could include:

- procedures to respond to requests from Nunavik hunters to harvest Beluga from this population

- designation of management zones and/or habitat protection measures if needed; and

- development of guidelines to reduce disturbance from activities such as tourism, shipping, and hydro-electric development if needed

Many of these actions are relevant to Ontario’s Management Plan. Recommended management approaches to support Beluga conservation in Ontario have been identified for respective management objectives (Table 2).

Table 2. Management plan approaches for action for the Beluga in Ontario

1. Undertake regular monitoring of the distribution and abundance of the Beluga population in and adjacent to Ontario waters.

| Management Theme | Management Approach | Relative Priority | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed | Relative Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment | 1.1 Monitor population trends through collaboration with other jurisdictions:

|

Necessary | Knowledge Gaps:

|

Long-term Ongoing |

| Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment Stewardship | 1.2 Ensure that all observations of Beluga are submitted to NHIC to be incorporated into the provincial Beluga database (LIO Provincially Tracked Species Observation layer):

|

Beneficial Necessary | Knowledge Gaps:

|

Short-term initiation, Ongoing |

| Management Stewardship | 1.3 Coordinate Ontario recovery efforts and maintain currency on Beluga management and scientific information:

|

Beneficial | Knowledge Gaps:

|

Short-term initiation, Ongoing |

2. Identify and protect high-value Beluga habitat, and obtain additional knowledge on Beluga use of Ontario rivers, estuaries and adjacent coastline.

| Management Theme | Management Approach | Relative Priority | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed | Relative Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protection | 2.1 Protect significant estuarine summer habitat:

|

Critical Necessary | Threats:

|

Long-term Ongoing |

| Management | 2.2 Monitor projected and actual increases in natural resource development and industrial activity. Ensure that potential implications to Beluga habitat are considered and addressed during the review of these projects. | Beneficial | Threats:

|

Short-term initiation, Ongoing |

| Research | 2.3 Conduct Ontario-specific research in order to evaluate habitat conservation needs:

|

Necessary | Knowledge Gaps:

|

Long-term |

3. Increase understanding of Indigenous Knowledge on the distribution, abundance, habitat, harvest, trends and status of Beluga in Ontario

| Management Theme | Management Approach | Relative Priority | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed | Relative Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stewardship Education and Outreach | 3.1 Conduct an assessment of existing Indigenous Knowledge of Beluga presence, distribution, habitat use, population trend and harvest. Update assessment regularly (10 year intervals). | Necessary | Knowledge Gaps:

|

Short-term initiation, Ongoing |

4. Increase awareness of the presence and conservation status and needs of Beluga in Ontario

| Management Theme | Management Approach | Relative Priority | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed | Relative Timeframe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education and Outreach Stewardship | 4.1 Increase awareness of the presence of Beluga in Ontario, and the identification of conservation needs:

|

Beneficial | Knowledge Gaps:

|

Long-term |

Supporting narrative

The background and rationale for a number of the management approaches which support each objective are addressed in the following section.

1.0 Undertake regular monitoring of the distribution and abundance of the Beluga population in and adjacent to Ontario waters

A number of the identified management approaches relate to improved inventory and monitoring, and the sharing of collected information. This is essential in order to understand the status and trends of the population, and thus the need for further or enhanced recovery actions. Considerable cross-jurisdictional collaboration is essential to complete these tasks. While the Western Hudson Bay Population is considered relatively robust and healthy, it does face a number of threats including increasing harvest. The Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission has recommended that "surveys of White Whale distribution and abundance continue, particularly in areas where there is little recent information on either." (Culik 2004). DFO (2002) recognized that a regular population monitoring program is an important tool to monitor changes in population abundance.

2.0 Identify and protect high-value Beluga habitat, and obtain additional knowledge on Beluga use of Ontario estuaries and adjacent coastline

Other jurisdictions have recognized the potential value of formally recognizing and conserving Beluga habitat. Manitoba has recognized the need to develop management plans to ensure that important summer river estuarine habitat is preserved for the Seal, Churchill and Nelson rivers, although these plans are not yet underway (Manitoba Conservation and Water Stewardship 2012, B. Watkins pers. comm. 2012). Habitat protection measures have been implemented for some nearshore areas of the Beaufort Sea that have been identified as off-limits to development due to their value as Beluga habitat or harvesting areas, including major summer concentration areas for Beluga (Fisheries Joint Management Committee 2001, North/South Consultants Inc and Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre 2003, World Wildlife Fund 2003). National Marine Conservation Area status is also being considered for some important habitats (Storace 1998).

Satellite telemetry studies have been extremely useful in identifying various aspects of Beluga ecology, including movement and habitat use patterns (Culik 2004). The Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Committee has noted that "tagging and telemetry studies of White Whales have provided important new information relevant to stock identity, migrations, habitat use and abundance," and recommended that "such studies are continued to increase sample size and are expanded to other regions" (Culik 2004). Recent telemetry studies on Beluga in the Seal River estuary in Manitoba are providing valuable information on Beluga habitat use in the western portion of the range of the Western Hudson Bay Population (Oceans North Canada 2013; Kives 2012). Some information on Beluga movements and habitat use in Ontario waters resulted from a study of Beluga equipped with satellite transmitters at the Nelson River in Manitoba (Smith et al. 2007), and Beluga from eastern James Bay have also been studied with satellite transmitters (Postma et al. 2012). No similar studies have been undertaken for the Ontario coast and rivers of Hudson Bay and western James Bay.

3.0 Increase understanding of Indigenous Knowledge on the distribution, abundance, habitat, harvest, trends and status of Beluga in Ontario

There is a substantial amount of documented Indigenous Knowledge on Beluga in the Arctic, commensurate with the importance of this species in the life of northern Inuit. As examples, studies of Indigenous Knowledge of Beluga have been conducted for Cook Inlet, Alaska (Huntington 2000), the northern Bering Sea in Russia (Mymrin et al. 1999), northern Quebec (Breton-Honeyman et al. no date) and Baffin Island (Kilabuk 1998). This contrasts with the situation in Ontario, where there is virtually no documented information on the role or significance of Beluga to northern Cree communities. The early report by Johnston (1961) is one of the few to record information on the harvest of Beluga in Ontario, including numbers, methods and uses. Documentation of Indigenous Knowledge on Beluga in Ontario waters is important as First Nations are the predominant group living adjacent to Ontario’s Beluga population.

Johnston (1961) reported that Fort Severn Cree harvested 8 Beluga and Winisk Cree harvested one Beluga during the summer of 1961; of these, 2 were harvested by rifle and 7 by net. Johnston (1961) reported that the meat of the Beluga was not preferred by Ontario Cree. Similar accounts have been reported for the Winisk River and residents of the former community of Winisk. The following information is provided by Mike Hunter (pers. comm. 2012), lifelong resident of Winisk and now Peawunuck:

- Beluga were typically harvested by chasing them into the shallow waters of the river or estuary, harpooning and then shooting them. Harpooning prior to shooting was important to ensure that the animal was not lost. Typically one Beluga was harvested per family. The meat was primarily used to feed dog teams during the summer, although the tender meat along the spine was sometimes eaten. Sometimes fat and oil was retained until the winter, and mixed with other food for the dogs. Local missionaries also harvested Beluga, usually by chasing the whales into a net strung across the river mouth. Efforts were made to avoid harvesting a female with a calf, although where a female with a calf was harvested the calf was generally also taken. Seals, the other locally available marine mammal, were typically not available locally until much later, in September. Although there was a long tradition of Beluga harvest prior to this time, harvesting of Beluga ceased between the mid-1960s and early 1970s, as residents converted from dog sled teams to snowmobiles.

It is interesting to note that 2 of the practices noted by Mr. Hunter (i.e. avoiding the harvest of females with calves, and harpooning a Beluga before shooting it) are among the conditions specified in various Nunavik co-management plans for Beluga (Kishigami 2005; DFO 2010c). It is apparent that even though there is not a major Beluga hunting tradition with the Hudson Bay Cree, recovery planning for Beluga could benefit significantly from a compilation of the traditional knowledge accumulated by coastal Cree First Nations. As noted by Brennen (2007), "The knowledge Beluga hunters have accumulated over generations of hunting and living on the land is an invaluable contribution to improving the understanding of Beluga biology, behaviour, ecology and patterns of movement".

The Beluga hunt is very important to northern Inuit communities from both a cultural and subsistence perspective (Kishigami 2005, DFO 2011). Beluga are an important food source to the Inuit of northern Quebec (DFO 2010b), Nunavut and the Nunavut Wildlife Management Board. There are several examples of co-management, where science and indigenous knowledge are shared in a collaborative manner to support Beluga management and conservation. A study in eastern Hudson Bay illustrated that indigenous knowledge and telemetry studies both shed information on different aspects of Beluga ecology, and both have limitations related to the respective approach (Lewis et al. 2009); for example, telemetry studies were limited by small sample size and short deployment times, while indigenous knowledge was biased by spatial coverage and coastal travel habits. One example of a successful co-management agreement is the Fisheries Joint Management Committee for the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (http://www.fjmc.ca/). Indigenous knowledge on Beluga has often affirmed published science (Huntington 2000). The Inuvialuit of the eastern Beaufort Sea have been active partners in Beluga co-management, providing harvest and biological data, and assisting in Beluga telemetry studies and aerial surveys (Harwood et al. 2000). Nunavik communities of northern Quebec are also involved in Beluga co-management (Kishigami 2005). Co-management is seen as essential to effective management of Beluga stocks, but there are significant challenges that include the large range, difficulties in determining stock status, and the large number of individuals and communities involved (Richard and Pike 1993).

4.0 Increase awareness of the presence and conservation status and needs of Beluga in Ontario

Marine mammal viewing guidelines are available for various jurisdictions (e.g. Watchable Wildlife Incorporated 2004, International Whaling Commission (2012), although there are few guidelines specific to Beluga and none specific to Ontario. Elsewhere, tourism guidelines are in place for the Beaufort Sea as part of the Beaufort Sea Beluga Management Plan, with the objective of facilitating Beluga viewing tourism opportunities while minimizing any impacts on Beluga and Beluga harvesting (Fisheries Joint Management Committee 2001). An IWC workshop report identifies a range of management options to mitigate the impacts of whale watching for various critical response variables (International Whaling Commission 2004). A thorough analysis of whale-watching guidelines and regulations globally identified the range of factors considered and the respective values for these factors (Carlson 2011); this review can provide valuable information for the development of more regional whale viewing guidelines. Voluntary marine mammal guidelines are available for Canada, and while they are generally followed they are not strictly enforceable (Government of Canada 2012). Amendments to the Marine Mammal Regulations have been proposed to provide a regulatory framework which will provide the DFO with "specific measures applicable to marine mammal watching activities without imposing a host of national prohibitions" (Government of Canada 2012). Among other things these amendments would introduce a minimum approach distance of 100 m to marine mammals, and require the reporting of any accidental contact with a marine mammal (Government of Canada 2012).

5.0 Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure.

DFO: Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

ECO: Environmental Commissioner of Ontario.

Eeyou Marine Region: The area covered by the Eeyou Marine Region Land Claims Agreement between the Crees of Eeyou Istchee and the Government of Canada covering an area of approximately 61,270 km2 off the Quebec shore in eastern James Bay and southern Hudson Bay. The Agreement settles the land and resource rights over the islands and marine waters in this area.7

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Element: A standard termed used by NatureServe that expresses a unit of natural biological diversity, which can represent species, natural communities, or other non-taxonomic biological entities such as migratory species aggregation areas or hibernacula (OMNR 2013).

Element Occurrence (EO): "An Element Occurrence (EO) is an area of land and/or water in which an Element is, or was, present. The NHIC stores information on EOs in a database… One can consider an occurrence as being analogous to a population…For many species (particularly those that are rare range-wide) the definition of an occurrence is defined globally by NatureServe so that all data centres define an occurrence for the same species in the same way." (OMNR 2013).

Estuary: A semi-enclosed body of water formed where freshwater from the lower reaches of a river contacts and mixes with seawater from the ocean, the river current is met by the tides and where the seawater is measurably diluted (adapted from Royce 1972).

Genetic Bottleneck: Reduced genetic variation that occurs in a population when a population’s size is reduced for at least one generation, and the population may not be able to adapt to new selection pressures because the genetic variation that selection would act on may have already drifted out of the population.8

Hudson Strait: Body of open water in northeastern Canada, between Baffin Island and northern Quebec that connects Hudson Bay with the Atlantic Ocean.

Inuvialuit: Inuit from the western Canadian Arctic.

IWC: International Whaling Commission.

Maqtaq (maqtaaq, muktuk): Inuit term for traditional food of frozen whale blubber and skin.

NHIC: Natural Heritage Information Centre, an OMNR organization that compiles, maintains tracks and distributes information in a spatial database on natural species, plant communities and species of conservation concern.9

NMRWB: Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board.

Nunavik: The northern territory of Quebec north of the 55th parallel that is the traditional homeland of Quebec Inuit.

Nunavik Marine Region Wildlife Board: The main instrument of wildlife management and the main regulator of access to wildlife under the Nunavik Land Claims Agreement, covering the offshore area of Quebec known as the Nunavik Marine Region.

Nunavimmiut: People living in Nunavik.

Nunavummiut: People living in the Territory of Nunavut.

Nunavut Settlement Area: The area identified in the Nunavut land claims settlement agreement between the Government of Canada and the Tunngavik Federation of Nunavut, representing the Arctic islands, mainland and adjacent marine areas of the eastern Arctic as well as the Belcher Islands and associated islands and adjacent marine areas in Hudson Bay.10

Panmictic: A group of animals where mating within the group is random and not based on genetic or behavioural restrictions in terms of subpopulations

Polynya (polynia): An area of unfrozen sea water surrounded by ice.

Population: A geographically and genetically distinct group of animals, based on largely disjunct summer distributions and genetic differences. Using this scheme of population division, there are seven Canadian Beluga populations recognized by COSEWIC (2004). These populations all have estuarine centres of aggregation during the summer open-water season. In most cases their summer coastal and offshore distribution is separate from other populations.

Sanikiluaq: Inuit community on the Belcher Islands of southeastern Hudson Bay.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Stock: A geographically separated resource unit, as a group of animals that are subject to harvest that can be managed separately from other groups. May or may not be populations according to the biological definition of a reproductively isolated group of animals. Also termed "management stocks".11

6.0 References

Asselin, N.C., D.G. Barber, P.R. Richard and S.H. Ferguson. 2012. Occurrence, distribution and behaviour of Beluga (Delphinapterus leucas) and bowhead (Balaena mysticetus) whales at the Franklin Bay ice edge in June 2008. Arctic 65(2):121-132. Available at http://arctic.synergiesprairies.ca/arctic/index.php/arctic/article/view/4194 (link no longer active) (abstract only).