Building the evidence base: the foundation for a strong community hub

The evidence reviewed by the Premier’s Community Hubs Framework Advisory Group.

Community hubs are an idea that both community and policy-makers agree make sense. Reports, conferences and symposiums have all addressed some of the many reasons that they do. This appendix will review some of the evidence for this.

With the tight timelines set out for this work, WoodGreen Community Services did a rapid evidence review analysis on community hubs case examples and best practices. This approach was appropriate (1) given the general consensus that hubs are a community benefit and (2) the short timelines for the development of the framework. As evidence was collected, it was summarized and fed to the Special Advisor, Cabinet Office and the Advisory Group.

The definition used for “Community hub” was broadly inclusive, crossing government, the non-profit and private sectors, including neighbourhood centres, business incubators and community schools, where multiple services were offered in a single location with the intention of serving multiple or complex needs. Each case example studied incorporated some form of co-ordinated programming and open community access (although some hubs targeted specific populations). Broader public sector organizations, such as libraries and recreation centres, were not included unless they explicitly described a hub model.

The evidence review involved collating examples of hubs already in operation across the province and other jurisdictions through web-based searches and key informant interviews. The compiled evidence was fed back, on key topics such as the elements of successful hubs or their social return on investment in the form of document reviews, report summaries, case studies, and presentations of thematic conclusions.

The focus of this review was guided by the questions set out at the start by the Special Advisor:

- What works?

- What are the barriers?

- And what can do the Province do to support this work more systematically?

This appendix provides a summary overview of these findings.

What works

Across the province and around the world, community hubs have emerged as a policy solution and as an important way to meet critical local needs and preserve community assets. Community hubs are one of those rare interventions driven both by the grassroots and by the “grasstops.”

Current hub initiatives

A rapid scan of community hubs within the province revealed close to 60 examples in communities across Ontario, in rural, suburban and urban neighbourhoods which are already established or in the planning stages. A preliminary mapping follows:

| Hub | City | Location | Community | Sector | Building form |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common Roof | Barrie | Central Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| David Busby Centre | Barrie | Central Ontario | Urban | Community | |

| W & M Edelbrock Centre | Dufferin County | Central Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| Bronson Centre | Ottawa | Eastern Ontario | Urban | Other | Rebuild |

| George Street Hub | Peterborough | Eastern Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| Hintonberg Hub | Hintonberg | Eastern Ontario | Rural | Health | Rebuild |

| Hub Ottawa | Ottawa | Eastern Ontario | Urban | Employment/ Entrepreneur | |

| Petawawa Civic Centre & Renfrew District facilities co-sharing agreement | Petawawa | Eastern Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Government | New Build |

| Prince of Wales Public School | Peterborough | Eastern Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | |

| Shannon Park & Rideau Heights Community Centre | Kingston | Eastern Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Recreation | Rebuild |

| The Mount | Peterborough | Eastern Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| 10 Carden | Guelph | GTA large | Low density (town, suburb) | Employment/ Entrepreneur | |

| Acton Hub – Our Kids Network | Acton (Halton) | GTA large | Low density (town, suburb) | Other | Rebuild |

| Aldershot Hub – Our Kids Network | Burlington | GTA large | Urban | Other | Rebuild |

| Eva Rothwell Centre | Hamilton | GTA large | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| Durham Hub | Durham Region | GTA large | Urban | Education | |

| Helping Unite Belmont (HUB) | Belmont (Elgin County) | GTA large | Rural | Community | |

| McQuesten | Hamilton | GTA large | Urban | ||

| Milton Hub – Our Kids Network | Milton | GTA large | Low density (town, suburb) | Other | Rebuild |

| Social Services Network | Markham | GTA large | Urban | Other | Rebuild |

| The Link | Georgina | GTA large | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| Wever Community Hub | Hamilton | GTA large | Urban | Recreation | Rebuild |

| Centre de Santé Communitaire (CHC) | Sudbury | Northern Ontario | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

| Community Corner | Sault Ste. Marie | Northern Ontario | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

| Etienne Brule Public School | Sault Ste. Marie | Northern Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Education | Rebuild |

| Evergreen a United Neighbourhood | Thunder Bay | Northern Ontario | Urban | Children & Youth | Rebuild |

| Gateway Hub | North Bay | Northern Ontario | Urban | Other | Virtual |

| Bluewater Health | Sarnia Lambton | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Health | New Build |

| Centre Communitaire Francophone Windsor-Essex-Kent | Windsor | SW Ontario | Urban | Other | Rebuild |

| Chatham Kent Hub | Chatham | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | New Build | |

| Eagle Place | Brantford | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Education | Rebuild |

| East Ward (Major Ballachey School) | Brantford | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Education | Rebuild |

| Fiddlesticks | Cambridge | SW Ontario | Urban | ||

| Fusion Youth Activity and Training Centre | Ingersoll | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Children & Youth | Rebuild |

| Langs | Cambridge | SW Ontario | Urban | Community | New Build |

| Northbrae Community Hub | London | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Education | New Build |

| Northside Neighbourhood hub | St. Thomas | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Community | Rebuild |

| Shelldale | Guelph | SW Ontario | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

| Strathroy-Caradoc Library | Town of Strathroy-Caradoc | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Other | New Build |

| The LDMH (Leamington District Memorial Hospital) Neighbourhood of Care | Leamington (Essex County) | SW Ontario | Low density (town, suburb) | Health | Rebuild |

| SiG MaRS Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Employment/ Entrepreneur | |

| AccessPoint on Danforth | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

| Artscape Young Place (formerly Givens-Shaw school) | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Arts | Rebuild |

| Bathurst-Finch Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | New Build |

| Bridletowne Neighbourhood Centre | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | New Build |

| Centre for Social Innovation | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Employment/ Entrepreneur | |

| Dorset Park Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

| George Street Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | New Build |

| Jane Street Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Health | |

| Junction Commons | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

| Mid-Scarborough Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Health | Rebuild |

| Rexdale Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Health | Rebuild |

| Victoria Park Hub | Toronto | Toronto | Urban | Community | Rebuild |

Leaders from multiple sectors have led these initiatives, including municipalities, school boards, health centres and planners, non-profit, neighbourhood-based agencies and local residents.

Benefits of hubs

Where community hubs operate, they demonstrate:

- Improved health, social and economic outcomes for individuals

- Demonstrated collective impact at the community level and integrated service delivery at the individual level

- Better social investment

- Protection of public assets

- Stronger communities across Ontario

From the health sector perspective, the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network worked with the Ryerson University-based Canadian Network for Care in the Community to identify the design features and benefits of a hub-based model for service delivery. These were:

- Shared space using a hoteling concept, with scheduling of various programs offered by different providers to maximize the use of space and to provide extended hours of service

- Provision of Primary Health Care and community based services on-site

- Flexible design, multi-purpose, multi-size areas for programs

- Space designed for current community needs and readily adaptable as community needs change, warranting corresponding program and service changes

- Reduces stigmatization associated with some single-purpose facilities (e.g., mental health or addiction services) through provision of services in a multiple program setting

- Improves patient and client experience through a seamless front-end that:

- supports coordinated access to on-site services through centralized intake and scheduling

- reduces the risk of multiple and duplicative assessments

- improves hand-offs of clients across programs and providers

- improves access to multiple services in one location

- reduces the need for multiple visits to access services

In the education sector, schools which co-located with community services also demonstrate improved outcomes for students and families. The Inner City Model Schools within the Toronto District School Board1 have tracked and demonstrated some of the strongest outcomes, including dimensions of academic achievement and health.

Social Return on Investment

One of the emerging areas of impact analysis is Social Return on Investment (SROI). SROI is cost benefit analysis with a social purpose. Looking over the lifetime of an investment, it identifies a monetary value for the cost and benefits of the provision of human services. This form of analysis creates a strong case proof for the value of many of the elements of community hubs.

Examples from multiservice, place-based delivery of services demonstrate the following investment ratios:

| Examples | Jurisdiction | Social Return per $1 investment |

|---|---|---|

| Craft Café (Seniors)2 | Scotland | 8.27 |

| Community Champions3 | Scotland | 5.05 |

| Beltline Aquatic & Fitness Centre4 | Calgary, Alberta | 4.84 |

| Minnesota Public Libraries’ ROI5 | United States | 4.62 |

| Schools as Community Hubs6 | Edmonton, Alberta | 4.60 |

| Peter Bedford Housing Association7 | London, England | 4.06 |

| Centrepointe ERC8 | Ottawa | 2.39 |

Completed SROI also demonstrated a range of other significant and specific impacts on local residents and communities in the social and health realms. These included lowered crime rates, avoidance of involvement with the youth justice system, higher school completion among youth, fewer falls for seniors, decreased diabetes rates, and higher levels of community trust.

2 socialvaluelab.org.uk/2012/03/craft-cafe-sroi-report-launch

4 simpactstrategies.com/LiteratureRetrieve.aspx?ID=171987

5 melsa.org/melsa/assets/File/Library_final.pdf

6 Mapsab.ca/downloads/events/april/2014/SchoolsAsHUBS.pdf

8 Burrett, John. Social Return on Investment: Centerpointe Early Childhood Resource Centre. Unpublished. Haiku Analytics. Ontario (February 2013).

Integrated Service Delivery

If hubs are examined from the program-side, they are most closely aligned with current discussions of Integrated Service Delivery (ISD)9. Community hubs provide the opportunity to enhance, coordinate and integrate service delivery to people and communities. ISD provides a sort of wraparound that allows concurrent needs to be met, thereby leading to more effective interventions and impacts.

Reviewed reports refer to an “integrated model of service delivery that looks like an inter-connected web of social services and supports at the community level that are supported by enabling policy frameworks at the systemic level that encourage and support formal planning, and integration activity between organizations” (A Report of the Community Social Planning Council of Greater Victoria, Albert, Marika, May 2013)10

The following themes are useful when examining community hubs:

- “No wrong door” must be a baseline approach

- A regional integrated hub model for a specific geographic area

- Non-linear with multiple entry and exit points, but with a single point of contact for client (i.e., to either provide service or to help client navigate to appropriate one)

- Continuum of care

- Words used to describe power of ISD in reports include: seamless, one-stop shop, wraparound, client-centred, accessible, responsive, “right care, at the right place, at the right time” etc.

Accountability within ISD governance and authorities:

- Cabinet level responsibility

- Clear single line of accountability within each ministry reporting through cabinet level structure (Nova Scotia Schools Plus)

- Lead agency at local or municipal level with partners mandated to be at tables (mentioned in an interview with Simcoe Community and Children’s Services that this was highly effective in creation of Best Start Hubs in the region)

- Single funding envelope and/or core funding (George Hull, Centre de santé Communitaire in Sudbury, OHA report)

Key Staff for ISD hub models:

- Right staff in the right places (How District and Community Leaders are Building Effective, Sustainable Relationships, IEL, 2012)

- Coordinators at both regional and local hub levels which are fully funded and recognize coordinators as ‘lynchpins’ of hub and key to hubs’ success

- Centre de santé communitaire in Sudbury has two co-ordinators: Coordinator of Health Promotion identifies and brings in partner agencies, catalyst for synergy in hub; and Co-ordinator of Community Development partnerships, outreach, capacity building

- “Back office” support staff (reception, website updates, appointment scheduling, system navigator, etc.); has broad system knowledge of all services available

- “Key players strategically placed….understanding that if no one is specifically designated and paid to organize/plan/communicate/outreach, etc., the work will not get done” (How District and Community Leaders are Building Effective, Sustainable Relationships, IEL, 2012)

Place-making & Community Building

Community hubs also demonstrate benefits with regards to “place-making” or community revitalization:

- Many community hubs purposefully set out to reinvigorate their local areas; foci can include local economic development, poverty reduction, supports for children and youth and/or seniors, mental health and health services, etc.

- Some hubs aspire to revitalize a particularly underserved community through a “social development lens” (Daniels Corporation and Regent Park project, Artscape Wychwood Barns, etc.)11

- This process can unleash a ‘dynamic synergy’ which helps build community capacity, ultimately strengthening the local community and fostering a sense of ownership and pride of place

Leveraging Partnerships

- Without exception, every report studied identified the critical importance of strong, collaborative partnerships that were leveraged to benefit the target populations of hubs

- Some partnerships involved service delivery (e.g.., public health, mental health programs, etc.), while others included private partnerships, proving “private sector can play a pivotal role in addressing social infrastructure deficits in these communities” (Daniels Corporation)

- An imperative to collaborate: Partnerships and collaborations are an effective way to move a project forward, especially when resources are scarce” (Daniels Corp)

- “In times of declining fiscal resources and greater demand for public services, districts have learned that forming partnerships can be fiscally prudent: on average, three dollars from community partners for every dollar they allocate (partners can contribute dollars or in-kind support in the form of access to family programs, health services and more).” (How District and Community Leaders are Building Effective, Sustainable Relationships, IEL, 2012)

- “Community Learning Centres (CLCs) have made great strides in assembling a wide array of partnerships. It has to be acknowledged that this is a major component of success for the initiative given that only a few of these partnerships existed prior to the establishment of the CLCs…CLC schools have generated over $10.5 million in contributions (human, material and financial resources) over the last four years (2010-2014) for an estimated 2.13 return on investment.” (Fostering Engagement and Student Perseverance Community Learning Centres – Changing Lives and Communities, September 2014, Quebec)

The Value of being Local

- Many reports identified the importance of hubs being ‘local,’ i.e., in and of the community and as close to the client/population they serve as possible

- “Improved client access based on a ‘care close to home’ philosophy” (Local Health Hubs for Rural and Northern Communities An Integrated Service Delivery Model Whose Time Has Come, OHA, 2012)

- Hubs should take into account accessibility (both in terms of public transport and ability), and ensure hubs are located where community and data has clearly identified a gap/need

- Local neighbourhood audits or scans (some referred to them as a “needs assessment”) are a ‘must’ and an excellent tool for identifying gaps in services, as well as broader demographic research data allowing hubs to then identify and clearly define their goals collaboratively based on evidence

- Audits/needs assessments can look at both social and physical infrastructure in community using a variety of tools (surveys, consultations, etc.) but must include involvement of key community players, especially in minority communities (e.g., Aboriginal, francophone, etc.) according to both the reports surveyed and several interviews (Simcoe County, Sudbury)

- Locally responsive: Hubs which deliver programs that “respond to, and are shaped by, the unique circumstances and needs and assets of their community” is a key characteristic cited in hub studies and interviews (Study of Community Hubs, Parramatta, Australia)

- Shared vision from the ground up: “A shared vision, set of principles and organizational strategies are a must for any place-based strategies” (Community Hubs Report, Parramatta, Australia; SPT Report, Victoria, B.C.; Artscape, etc.)

9 In Ontario, housing, employment and mental health practitioners all use this concept.

10 Reports reviewed here which include this element and which are cited in this section are: George Hull Centre (Mental Health Hub), Local Health Hubs for Rural and Northern Communities (OHA 2012), Schools as Centres of Community (US, see example of PS 5 The Ellen Lurie School, New York), SchoolPLUS (Saskatchewan), SchoolsPlus (Nova Scotia)

11 “Artscape Wychwood Barns is a community cultural hub that opened in 2008 where a dynamic mix of arts, culture, food security, urban agriculture, environmental and other community activities and initiatives come together to provide a new lease on life for a century-old former streetcar repair facility.” (p. 1 of Hub Report Overview)

Common Elements for Community Building in successful hubs

In many reports, the value of hubs which are designed by the community for the community, and are therefore responsive to the needs of the community, could not be emphasized enough. As mentioned above, local communities and their inhabitants across Ontario are all unique, so a top down (policy and funding) and bottom up (local input and involvement from the very beginning) are a good way to approach hub development, i.e., “common tools, local design.”

- Community connections matter – no matter the focus of the hub: “Community connections ground children and give a sense of belonging that can help counteract challenges in their lives” (Exploring Schools as Community Hubs, Regina, 2011, p. 21)

- “A school might be thought of as a two-way hub when children’s learning activities within the school contribute to community development and when community activities contribute to and enrich children’s learning within the school.” (Ibid, D. Clandfield)

- “…the importance of having clear and focused goals when working with communities, the recognition of the importance of working from the beginning with the whole school community if trying to effect change, and again, the unquantifiable energy that can take place when school, community and partners come together in a common space to achieve a common goal.” (OPHEA, The Living School Success Stories, 2004-2008)

- “Successful hubs include a variety of uses and services (including community services, health care, leisure and retail that attract different groups of people at different times of the day and meet a wide range of community needs and support community strengths” (Feasibility Study of Community Hubs, Parramatta, Australia)

- Centre Santé in Sudbury is community inspired and driven; 450 card-carrying members (cards have no value, but reflect community support for Centre), 13,000 volunteer hours per year and a Board of Directors which is “embedded in community” (not hospital-style governance as per many CHCs); “important to recognize that each community and therefore each hub is unique, if you create right conditions and allow hub to evolve with the community, then each site will be a reflection of the unique community in which it is situated” (Executive Director Denis Constantineau)

- “Have a civic quality, sense of stability and level of amenity that marks them [hubs] as an important place in the community…include an inviting public domain that encourages people to interact in the public realm” (Parramatta)

Evaluation

Theories of Change

Although hub advocates often describe hubs’ benefits using an ingrained sense of their worth, evaluation tools such as Theories of Change and logic models allow more detailed descriptions to emerge. A theory of change should describe why an intervention is being used. A review of hub providers who had developed a theory of change showed common elements are service and space, which lead to community synergy.

A graphic from the Centre for Social Innovation (CSI) depicts this most simply, with the synergy depicted as a wide series of swoops at the top of the theory of change. It is labeled “Innovation.” CSI is so committed to this idea of what emerges when community and space are combined that it has also incorporated this pictorially into its organizational logo.

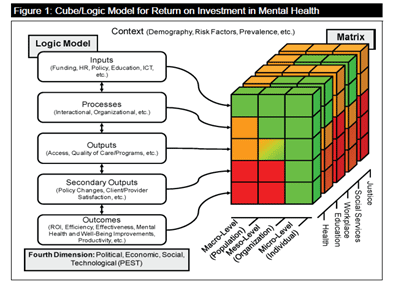

Transecting a number of fields, hubs are expected to facilitate integrated service delivery and build collective impact. So, other theories of change attempt to capture and enumerate the multiple dimensions across which hubs cut. One mental health model12 illustrated this complex matrix almost as a Rubik’s cube.

12 Canadian Institute for Health Information, Return on Investment: Mental Health Promotion and Mental Illness Prevention, 2011, p. 4.

The 2005 Strong Neighbourhoods Taskforce also identified the complex interplay and importance of a place-based approach to community services and to communities. Subsequently, United Way Toronto developed community hubs in its Strong Neighbourhood Strategy. These are seen as important levers to bring programs to underserviced areas, increasing access to community space.

Virtual hub models, which aim to co-ordinate and increase access to local services, have also emerged in places as wide ranging as North Bay, Ontario and Chicago13. These places are using a hub model to co-ordinate service interventions and develop common evaluation standards.

13 Chicago Peace Hub: peacehubchicago.org/about-us/the-peace-hubs-four-levers-of-change

What doesn’t work

Despite the good work that is being done in the development and operation of hubs, a number of barriers were also identified.

Costs are long-term and broad, but funding is project-driven and siloed

What community hubs do not do is reduce costs. Some cases show, in fact, increased costs in the short term. But what they do instead is increase the efficiency of current program funding, reducing duplication and leveraging new opportunities, and reduce longer-term societal costs, demonstrating a “social return on investment” which makes the economic case for their creation and support.

Hubs also struggle with funding.

- Funding is siloed, so that a single entity reports to several provincial ministries, each with their own accountabilities.

- Funding cycles often do not align, creating additional administrative burdens for organizations.

- Three separate funding streams are necessary to create and operate hubs:

- Capital dollars for development, often raised through fundraising

- Capital dollars for sustaining operations, which are scarce

- Ongoing operating funding for programs, staff and core services.

Examples of tight funding restrictions, put in place by funders’ narrow mandates, led in one case review to long-winded negotiations about which program clients might be using a bathroom in the hub.

Complex legislative and regulatory environment

The review identified a range of large-bucket areas where hubs development and operations need to negotiate regulatory boundaries which affect their creation and operation. These include:

- Zoning and Planning

- Building codes, including AODA compliance

- Privacy

- Occupational Health and Safety

- Compliance with local by-laws

Issues of privacy and confidentiality have received some focus as service providers strive to provide wraparound services, meeting the needs of their clients, while respecting their rights under Ontario legislation. Health care service providers carry an additional burden of protections so that cooperation with non-health care providers can be difficult to negotiate. Some hub models have managed this by walling the two service sides off from each other. Compliance is critical but complex.

Things to consider in community hub development

| Condition | Issue | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Funding Sources | Precedence of reinvesting city fees/charges and cash-in-lieu of parkland arising from a development locally | Approve funding strategy due to need to revitalize priority neighbourhood. |

| Construction Costs | Limited cost overrun protection | Report back to Council on whether to proceed with Proposal if fixed priced term cannot be met, and if so, with funding sources for any cost overruns. |

| Securing the Community Benefits | Proposed LC terms inadequate in relation to project cost | More substantial LC be retained until project delivery. Mortgage value in favour of City on 33 King Street to be co-ordinated with LC to provide greater security. |

| Real Estate Processes | No issues | Sale of 22 John Street and expropriation of 14 John Street to proceed. |

| Municipal Capital Facilities Designation | Need to determine that use meets bylaw requirements | Confirm that use meets bylaw requirements and secure in Capital Facilities Agreement. |

| Development Charges Credit | No issues | Council approve DC credit. |

Affordable Rental Housing Live/Work Units Community/ | Building condition will be studied in next phase of development | Council approve Investment in Affordable Housing funding. Ensure that Building Condition Assessment is completed for 33 King Street. |

| Open Space Area | City to retain ownership of Open Space Area | Ensure environmental and jurisdictional issues addressed. |

| Ownership and Tenure | Lease between Artscape and Woodbourne Capital, the owners of 33 King Street; in event of default, City recourse includes assuming lease or foregoing community benefit | Protect community benefit with conditions of lease reviewed and approved by City. |

| Tax Arrears | Artscape’s Wychwood Barns hub in tax arrears due to MPAC assessment delay | Ensure arrears resolved prior to entering into agreements with Artscape. |

| City Planning | Securing of access easements and determination of Section 37 benefits | Planning review to be expedited once Rockport has made the necessary applications, following Council-approved Section 37 Implementation Guidelines and process. |

| Social Return on Investment | No issues | Approve funding strategy to support social, economic and cultural returns for the City and neighbourhood. |

The Weston Community/Cultural Hub: Next Steps

Site development and property management

The expertise required to develop a community hub is often outside the experience of community service providers and local residents who have responded to the challenge.

One 2011 report, for the ICE Committee, described the long list of demands required during the development of community hubs:

- Partnership-building

- Feasibility studies

- Lease agreements

- Cost-sharing

- Program space design and allocation/hours

- Outreach and communication

- Itinerant partnering

- Protocol development

- Source funding

- Capital dollars fundraising

- Location identification

- Community consultations/needs assessments

- Zoning/permits, design and space allocation

- Visioning

- Service planning

- Governance and administration

Another case reviewed included a list of considerations which had to be worked through before further progress could be made (see figure 2). Hub providers made jokes about the needed heroics to move their projects forward and bewilderment at the extent of them.

Re-built, re-purposed and renovated spaces have also been shown to be more complex and more expensive than new builds.

What can the province do

The work of local heroes

Most of the hubs already established within Ontario are the result of ‘local heroes,’ individuals, organizations, networks and sectors that have seen a need – or an opportunity – in their community and who have responded to it.

In Hamilton, both the Wever Hub, named after a local community police officer, and the Eva Rothwell Centre at Robert Land, named after the mother of a benefactor, were established in low-income neighbourhoods when local community members recognized a need. They built partnerships with public and private sector organizations and local government over a number of years to create a safe, shared space and set of programs the community could enjoy.

Social purpose real estate has emerged as a new model for self-organizing non-profit enterprises. Common Roof in Barrie and some of Artscape’s hubs in Toronto emerged with the recognition of the effectiveness of shared space.

The most important support the province can provide to community hubs is to develop a system which is responsive to local demand, providing it is technical, regulatory and funding supports where needed, and stepping out of the way where not.

Next steps

The provincial government has a number of policy, regulatory and funding levers with which it can support the continued development of hubs.

One of the more comprehensive summaries of how the province might respond was captured at the May 2014 Community Assets for Everyone Symposium on community hubs. Invited stakeholders identified key components in the development and creation of community hubs at a system (provincial) level.

These included:

- A citizen-focused vision of service delivery

- Provincial leadership and collaboration from the various government partners

- A cohesive legislative framework and mandate to foster co-location and coordination

- Appropriate structures, policies, incentives and resources to sustain the approach and people who will make this work

- Flexibility to support and enable community-driven solutions

- Start with co-location and build towards integration

This review was also able to identify the following areas for potential action by the province:

- Mapping: No province-wide mapping has been done, partly because of definitional breath and partly because of service silos. The Ministry of Education has mapped Best Start hubs across the province, while also providing local demographics and service features. The Intergovernmental Committee on Labour Force and Economic Development commissioned a 2011 study of the numerous initiatives underway in Toronto, mapping those.

- Funding: Hub operators have identified the numerous funding streams they access and the administrative burden this places on organizations and partnerships which offer multiple services. A common funding portal would ease some of this. Qualifications for capital funding loans, currently offered through Infrastructure Ontario, might also be reviewed in terms of their accessibility for hub developers.

- Co-ordination Planning and Funding of Hubs: Hub developers identified a range of overlapping jurisdictions, clashing planning definitions, program priorities, and funding deadlines which they must negotiate in order to create a hub with multiple stakeholder. The province can demonstrate leadership in coordinating these to ease the burden of developing and administering place-based delivery of services.

Some emergent solutions will be low-investment, quick start options. Others will require more consideration and commitment, using a ‘whole government’ approach. Change at this order will require a change management process with input from all involved stakeholders.

The development of a community hub framework is a strong step towards making the changes needed.