2016-2017 Chief Drinking Water Inspector Annual Report

Get information on the performance of our regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, and enforcement activities and programs.

Message from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector

I am pleased to present the 2016-2017 annual drinking water report for Ontario. It highlights efforts to keep our drinking water clean and among the best protected in the world.

Ontario uses a multi-barrier approach of strong legislation, stringent health-based standards, regular and reliable testing, highly trained operators, regular inspections and a source water protection program to protect the province’s drinking water.

In 2016-2017:

- 99.84% of 517,601 drinking water test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards.

- 99.4% of 661 municipal residential drinking water systems received an inspection rating indicating compliance of over 80% with Ontario’s strict regulations. 465 systems or 70% of systems inspected had a perfect rating of compliance.

- 96.14% of 15,380 test results met our standard for lead in drinking water at schools and child care centres. When looking at flushed samples only, this number rises to 98%. This is up from 94% when the program began in 2007.

We continue to have strong working relationships with partners in the ongoing enhancement of our drinking water protection system. One of our key partners, Dr. David C. Williams, the Chief Medical Officer of Health for Ontario, provides an update in this report on the performance of regulated small drinking water systems.

Along with our efforts to ensure that our drinking water is among the best protected in the world, we are also striving to make sure that our protection of it is among the best communicated. Since 2006, we have transparently summarized data related to drinking water quality through this report and, since 2015, on the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page of the Open Data Catalogue. This year, we have also expanded the data available on the Open Data Catalogue and are committed to regularly updating this data. We look forward to continuing to deliver safe, high quality drinking water.

Orna Salamon

Chief Drinking Water Inspector (Acting)

Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change

Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Ontario’s drinking water is protected by a comprehensive safety net. The safety net has eight elements, all equally important, that provide a strong framework to safeguard drinking water from source to tap.

Figure 1: Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Ontario’s source water protection plan

The first step in the multi-barrier approach is to safeguard sources of drinking water. To that end, 19 local source protection committees were formed across Ontario with representatives from municipalities, First Nations, industry, the farming community and the general public. These committees have identified local activities that could pose a risk to their municipal water supplies and have developed plans to manage those risks.

All of the source water protection plans are now in effect and contain a series of locally-developed policies that protect existing and future sources of municipal drinking water from becoming contaminated or depleted. Municipalities, source protection authorities, local health boards, the province and others are implementing the policies and reporting on progress on a yearly basis.

Drinking water quality standards

Ontario regulates the quality of drinking water by establishing strict health-based standards for microbiological organisms and chemical and radiological substances, as prescribed under the Safe Drinking Water Act. The Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards are listed in Ontario Regulation 169/03 (O. Reg. 169/03).

A 2016 consultation on the Environmental Registry resulted in amendments to adopt new standards for toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes and revise existing standards for selenium and tetrachloroethylene. One drinking water standard, the sum of nitrate and nitrite, was removed as Ontario already has individual drinking water quality standards for both nitrate and nitrite. These amendments came into force on July 1, 2017.

The subsequent sections of this report provide information on how the drinking water produced by regulated drinking water systems is meeting these standards as well as information on adverse water quality incidents, drinking water advisories, inspection results, orders and convictions. To view the data associated with these sections, please visit the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page on our Open Data Catalogue.

Ontario’s drinking water test results summary

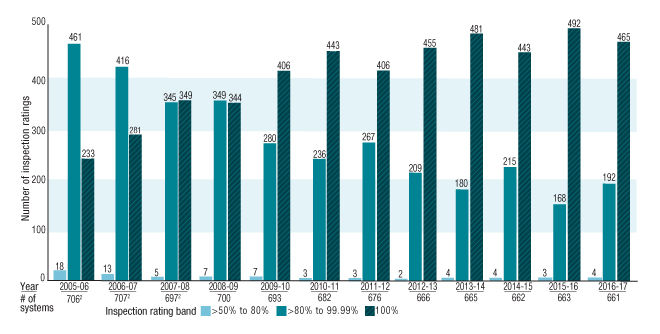

Since 2004-05, more than 99% of Ontario’s drinking water test results from the 3 regulated system types have met the province’s microbiological, chemical and radiological standards.

Figure 2: Trends in percentage of drinking water tests meeting Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards, by type of facility1

A chart showing trends in percentage of drinking water tests meeting standards for municipal residential drinking water systems, non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems and systems serving designated facilities over 13 years. The trend is consistent for all 3 system types showing that over 99% of drinking water test results since 2004-05 have met standards.

For municipal residential drinking water systems, the percentage of drinking water test results meeting standards ranged from 99.74% in 2004-05 to 99.84% in 2016-17.

For non-municipal year-round drinking water systems, the percentage of drinking water test results meeting standards ranged from 99.41% in 2004-05 to 99.4% in 2016-17.

For systems serving designated facilities, the percentage of drinking water test results meeting standards ranged from 99.06% in 2004-05 to 99.69% in 2016-17.

Notes for Figure 2:

1 There were slight variations in the methods used to tabulate the percentages year-over-year due to regulatory changes and different counting methods.

2 Lead results were not included as they were reported separately.

3 Lead distribution results were included but lead plumbing results were reported separately.

4 The total trihalomethanes running annual average calculation changed part way through fiscal year 2015-16.

Municipal residential drinking water systems

Ontario’s municipal residential drinking water systems continue to deliver high quality drinking water, as confirmed by test results. In 2016-17:

- 99.84% of 517,601 drinking water test results from 658

footnote 2 municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards.

For data on these systems, please see Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement on the Open Data Catalogue.

While over 99.84% of test results met Ontario’s standards, adverse water quality incidents may occur when drinking water test results do not meet Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards or an operational malfunction has taken place at a drinking water system. Each incident is taken seriously. The report of an adverse water quality incident does not necessarily mean the drinking water is unsafe. It indicates that an incident has occurred and that corrective action must be taken. Corrective actions may include resampling and retesting and/or adjusting the system or treatment processes. If there is concern that the water may not be safe for public consumption, the local medical officer of health may issue a drinking water advisory.

During 2016-17, 352 systems reported 1,362 adverse water quality incidents.

A drinking water advisory that is in place for 12 consecutive months is known as a long-term drinking water advisory. In 2016-17, the ministry confirmed that there were no new long-standing drinking water advisories.

Treated drinking water from Ontario’s municipal drinking water systems is regularly tested for a number of contaminants, including lead. The treated water leaving these systems would have lead levels within Ontario’s drinking water quality standard. However, as the water moves through the distribution pipes and the plumbing in people’s homes, any corrosion that exists in older distribution pipes, home service lines and plumbing may result in elevated lead levels at the tap.

Test results for lead in drinking water samples taken from taps (i.e. plumbing) indicate that the majority continued to meet the Ontario standard. The percentage remained consistently high at 94.97% in 2016-17. Out of 4,751 test results in 2016-17, 239 exceedances for lead in plumbing occurred.

If these exceedances meet the criteria specified in the Drinking Water Systems Regulation (O. Reg. 170/03), owners/operating authorities must develop a strategy to decrease the lead concentrations. The ministry required 20 municipalities to prepare strategies to control lead in drinking water. Of the 20 municipalities:

-

Seven municipalities have implemented their lead control strategies:

- Six completed implementing their corrosion control plans.

- One has completed replacement of its lead service lines.

-

Thirteen municipalities continue to make significant progress in addressing their lead issues:

- Three completed implementing their corrosion control plans and are replacing lead service lines.

- Two are in the process of implementing their corrosion control plans.

- One is in the process of implementing its corrosion control plan and replacing lead service lines.

- Seven are replacing lead service lines.

In 2016-17, no additional municipal residential drinking water systems have been identified to develop lead control strategies.

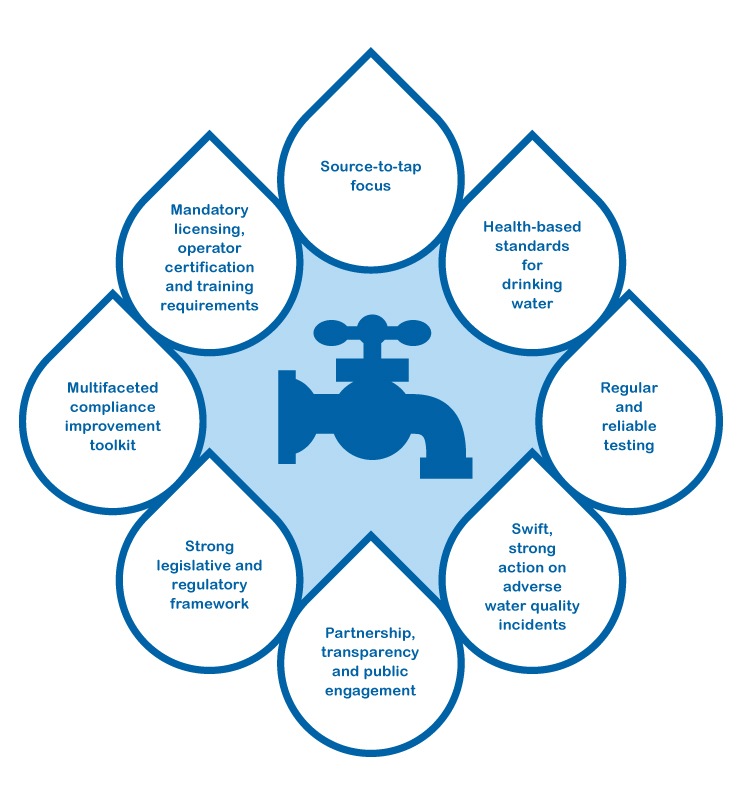

The province inspects all municipal residential drinking water systems at least once a year to verify whether the owners and operators are complying with Ontario’s regulatory requirements in the operation of their systems. Staff inspected all 661 systems in 2016-17. Of these, 465 systems (or 70%) achieved a 100% inspection rating. 657 of the 661 (or 99.4%) inspections received inspection ratings greater than 80%.

Figure 3: Yearly comparison of municipal residential drinking water system inspection ratings1

A chart showing trends in inspection ratings for municipal residential drinking water systems over 12 years. The inspection ratings are grouped into 3 categories. The number of inspections that yielded inspection ratings greater than 50% but less than or equal to 80% decreased from 18 in 2005-06 to 4 in 2016-17. The number of inspections that yielded inspection ratings greater than 80% but less than or equal to 99.99% decreased from 461 in 2005-06 to 192 in 2016-17. The number of inspections that yielded inspection ratings equal to a 100% increased from 233 in 2005-06 to 465 in 2016-17.

Notes for Figure 3:

1 The decline in the total number of systems is due to amalgamations of these systems.

2 Between 2005-06 and 2007-08, the ministry completed its planned annual inspection program of all municipal residential drinking water systems in Ontario generating its annual inspection rating for each system. During this period, for a number of reasons some systems were inspected twice, e.g., a water treatment plant and distribution system were registered as 2 systems but were inspected together as 1 system and vice versa or to ensure equipment had been properly decommissioned.

Ontario can issue contravention or preventative measures orders as a result of non-compliance activities observed during an inspection, incidents occurring outside of the inspection period, and to prevent incidents from happening. During 2016-17, 2 contravention orders were issued to 1 municipal residential drinking water system as a result of an inspection.

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

In 2016-17:

- 99.4% of 41,115 drinking water test results from 445 registered non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards.

These are registered drinking water systems that are privately owned and serve residential developments such as apartment buildings and mobile home parks with 6 or more units.

The majority of test results for lead in plumbing from these systems continued to meet the provincial standard. The percentage remained relatively stable at 98.53% in 2016-17. During 2016-17, there were 19 exceedances for lead in plumbing out of 1,289 test results.

If an adverse water quality incident is reported by the owners and operators of these systems, it does not necessarily mean that the drinking water is unsafe. It does mean that they must take corrective actions to address the incident.

In 2016-17:

- 179 systems reported 408 adverse water quality incidents.

- Ontario inspected 97 of the 461

footnote 3 registered drinking water systems. - 9 contravention and 2 preventative measures orders were issued to 11 systems.

Local services boards

Some northern Ontario communities and their associated drinking water systems are managed by local services boards as municipal governments have not been established.

During 2016-17, the province inspected all 7 systems and did not issue any orders.

Systems serving designated facilities

In 2016-17:

- 99.69% of 72,071 drinking water test results from 1,337 registered systems serving designated facilities met Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards.

These systems supply water to buildings and places such as children’s camps, schools, health care centres and senior care homes that are not connected to municipal systems.

In 2016-17:

- 352 of 1,448

footnote 4 registered systems reported 491 adverse water quality incidents. - 258 systems were inspected.

- 7 contravention orders and 1 preventative measures order were issued to 8 systems.

Schools and child care centres

Since 2007, the Schools, Private Schools and Child Care Centres Regulation (O. Reg. 243/07) has required these regulated facilities to flush their plumbing and sample for lead in drinking water. The purpose of these requirements is to help reduce the likelihood of children attending these facilities from being exposed to excessive levels of lead in drinking water. To ensure that these facilities are complying with the law, Ontario has implemented a multi-faceted program including inspections and audits.

While lead is generally not found in water from municipal drinking water plants, it may be present in certain facilities with older pipes, solder and fixtures, especially buildings built prior to 1990. Flushing of plumbing has been proven to decrease the amount of lead in drinking water in these cases. The flushing process reduces the length of time water resides in the facility’s plumbing, which reduces the potential for any lead to leach into the drinking water from plumbing components that may contain lead. These facilities are also required to take samples of the drinking water from the tap before and after they flush the plumbing. A comparison of the flushed sample results versus the standing sample results consistently shows that flushing significantly reduces lead in drinking water.

The vast majority of schools and child care centres have found no problems with lead in their drinking water. If an exceedance of the lead standard does occur, the facility operator must take immediate corrective actions as may be directed by the local Medical Officer of Health. Examples of corrective actions include resampling, increasing flushing durations and frequency and replacing of pipes or fixtures containing lead. In specific situations it may be necessary to prevent use of drinking water fountains or taps, post “do not drink the water” signage above a drinking water source or provide an alternate source of drinking water.

Facility operators are required to document corrective actions and issue resolution details and submit them to the Ministry of Education, local public health unit as well as the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change’s Spills Action Centre.

Throughout the year and during inspections, ministry staff ensure corrective actions issued by the local Medical Officer of Health to address adverse test results have been followed.

In 2016-17:

- 98% of 7,689 flushed test results from schools and child care centres were found to meet Ontario’s drinking water quality standard whereas 94.28% of 7,691 of standing test results met the standard.

- 6,801 schools and child care centres submitted flushed drinking water samples to licensed and eligible laboratories for testing for lead. Over 98% of these facilities met the standard for lead.

- Ontario carried out 146 inspections and 61 compliance audits of the 11,308 registered facilities and did not issue any contravention or preventative measures orders.

For details on these results, please see Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement Catalogue page on the Open Data Catalogue.

Licensed and eligible laboratories

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, laboratories must be accredited and licensed to test drinking water. The ministry issues drinking water testing licences for laboratories located within Ontario. In addition, there are 2 laboratories which are located outside of Ontario that are eligible to test Ontario’s drinking water. These laboratories must meet specific ministry requirements and must be added to the ministry’s eligibility list. These out-of-province laboratories are affiliated with licensed laboratories within Ontario.

Ontario inspects all laboratories at least twice a year to ascertain whether they are meeting the regulatory requirements. In 2016-17, there were a total of 53 licensed laboratories in the ministry’s Laboratory Licensing Program; however, 52 were inspected as one licensed laboratory departed the program in April 2017.

The ratings from all inspections were greater than 90% in 2016-17. 41% of all inspections resulted in perfect ratings of 100%.

Three contravention orders were issued to three licensed laboratories in 2016-17. One order resulted from non-compliance issues found during a routine inspection. The other 2 orders resulted from non-inspection related compliance issues. For details on these laboratories, please see Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement on the Open Data Catalogue.

Compliance and Enforcement Regulation requirements

Under the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (O. Reg. 242/05) of the Safe Drinking Water Act, Ontario is required to fulfil a number of specific responsibilities with respect to inspecting municipal residential drinking water systems and laboratories that test drinking water. For example:

- Inspecting all municipal residential drinking water systems annually

- Ensuring at least 1 out of every 3 inspections of each municipal residential drinking water system is unannounced

- Inspecting all licensed and eligible laboratories at least twice a year and ensuring that at least 1 inspection is unannounced

In 2016-17, Ontario met all its obligations required under this regulation.

Convictions

Legislation such as the Safe Drinking Water Act and the Ontario Water Resources Act protects communities and the environment. If these laws are broken, Ontario can take strong action.

In 2016-17, 5 regulated systems and 1 non-licensed well contractor were convicted for non-compliance. Together, the convictions resulted in fines of $50,500. The convictions data reflects the year in which the conviction took place and not the year in which the offence was committed. For details on these convictions, please visit Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement on the Open Data Catalogue.

Operator certification and training

Drinking water operators in Ontario must take training suited to the type and class of system they operate. Operators can hold multiple certificates allowing them to work in more than 1 type of drinking water system. As of March 31, 2017, 6,835 drinking water operators held 9,308 certificates.

Operators play an important role in protecting drinking water across the province and safeguarding public health. While incidents of questionable operator actions are rare, the ministry takes them very seriously. The ministry is authorized to revoke or suspend an operator’s certificate or bar an operator from holding future certificates/licences. During 2016-17, the ministry barred 1 operator from writing certification exams for 1 year for contravening the exam code of conduct.

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre is an important partner in the training of operators across the province. In 2016-17, the Centre trained more than 6,500 new and existing professionals.

The Centre also offers a training course for municipal officials to help them understand their role and responsibilities in the delivery of safe drinking water for their community pursuant to Section 19 of the Safe Drinking Water Act (Statutory Standard of Care). As of March 31, 2017, 2,581 municipal officials have received training.

Small Drinking Water Systems Program – Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

Message from the Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ontario’s Small Drinking Water Systems Program continues to demonstrate its value in protecting the health of Ontarians with the release of the 2016-2017 program results.

Since its inception in 2008 by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the success of the Small Drinking Water Systems Program has been realized through a shared commitment to excellence by Ontario’s boards of health, Public Health Ontario Laboratories, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. Owing to the enduring collaboration between these partners, Ontarians and its visitors continue to benefit from a comprehensive safe drinking water program.

The Program has upheld Justice O’Connor’s recommendations by not compromising on rigorous drinking water quality standards established for the province while enabling reduced regulatory burden on small system operators. Comprehensive inspections and risk-based assessments provided by public health inspectors produce a customized site-specific plan for owner/operators of small drinking water systems to keep their drinking water safe. Ongoing monitoring of the Program ensures accountability and supports the Ontario government’s commitment to public transparency.

I want to thank the local boards of health and all of our drinking water partners for their hard work and vigilance to ensure the provision of safe drinking water for Ontarians and their families.

David C. Williams, MD, MHSc, FRCPC

Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

2016-17 Highlights of Ontario’s Small Drinking Water System Results

Ontario has approximately 10,000 small drinking water systems regulated under the Health Protection and Promotion Act and its regulations. These systems are located across the province in semi-rural to remote communities and provide drinking water in restaurants, places of worship, community centres, resorts, rental cabins, motels, bed and breakfasts, campgrounds and other public settings, where there is not a municipal drinking water supply.

The Small Drinking Water Systems Program is a unique and innovative program overseen by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and administered by local boards of health. Public health inspectors conduct detailed inspections and risk assessments of all small drinking water systems in Ontario, and provide owner/operators with a tailored, site-specific plan to keep their drinking water safe. This customized approach has reduced unnecessary burden on small system owner/operators without compromising strict provincial drinking water standards.

Owners and operators of small drinking water systems are responsible for protecting the drinking water that they provide to the public. They are also responsible for meeting Ontario’s regulatory requirements, including regular drinking water sampling and testing, and maintaining up-to-date records.

2016-17 at a glance:

- Over the past 5 years, we have seen progressively positive results including a steady decline in the proportion of high-risk systems (11.59% in 2016-17 down from 16.65% in 2012-13). As of March 31, 2017, over 3 quarters (75.42%) of small drinking water systems are now categorized as low risk.

- A decline of 20.60% in total number of adverse water quality incidents was observed between 2012-13 (1,471) and 2016-17 (1,168); and the number of small drinking water systems that reported an adverse water quality incident for the same period also declined by 18.24% from 1,173 in 2012-13 to 959 in 2016-17.

footnote 5 - 97% of over 99,000 drinking water samples submitted from small drinking water systems during the reporting year have consistently met Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards.

- As of March 31, 2017, 18,942

footnote 6 risk assessments have been completed for the approximately 10,000 small drinking water systems. - Over 88% of systems are categorized as low/moderate risk and subject to regular re-assessment every 4 years; while the remaining systems, categorized as high risk, are re-assessed every 2 years.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph The number of parameters listed in O. Reg. 169/03 has been updated from 145 (as reported in the 2015-2016 Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report) to 150 due to amendments that came into effect on January 1 and July 1, 2017. In summary, 6 new standards were added (i.e. chlorite, chlorate, 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid, ethylbenzene, toluene and xylenes) and one standard for nitrate plus nitrite was removed bringing the total number of standards to 150. The parameters that drinking water systems must test for are given in the Drinking Water Systems Regulation (O. Reg. 170/03).

- footnote[Figure 2 description] Back to paragraph

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph There were 661 registered municipal residential drinking water systems in 2016-17 and of these 658 submitted samples. Three systems that received their water from another municipal residential drinking water system had their samples represented within the samples collected and submitted by the municipal residential drinking water systems that supplied water to them.

- footnote[Figure 3 description] Back to paragraph

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph In 2016-17, there were 461 registered non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, however, only 445 of these systems submitted samples for testing as some ceased to operate and/or data was not provided to the ministry.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph The number of systems serving designated facilities that were registered in 2016-17 was more than those that submitted samples for the following reasons: some systems ceased to operate and/or data was not provided to the ministry, while some received drinking water for their cistern from municipal residential drinking water systems which carried out the required sampling on their behalf. Sampling was not required for those systems that posted notices advising people not to drink the water.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph An adverse test result does not necessarily mean that users are at risk of becoming ill. When an adverse water quality incident is detected, the small drinking water system owner/operator is required to notify the local medical officer of health and to follow up with any action that may be required. The public health unit will perform a risk analysis and determine if the water poses a risk to health if consumed or used and take additional action as required to inform and protect the public. Response to an adverse water quality incident may include issuing a drinking water advisory that will notify potential users whether the water is safe to use and drink or if it requires boiling to render it safe for use. The public health unit may also provide the owners and/or operators of a drinking water system with necessary corrective action(s) to be taken on the affected drinking water system to address the risk.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph The reported number of risk assessments will change as new systems come into use/change in use, and routine re-inspections and risk assessments are completed. Risk categories may also fluctuate (e.g., if recommended improvements are taken to reduce the system’s risk). Similarly, a system may require reassessment to determine if the risk level has changed (e.g., if the water source or system integrity is affected by adverse weather events or system modifications).