Dense Blazing Star Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for Dense Blazing Star, a species of plant at risk in Ontario.

Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

Photo: Wasyl Bakowsky

2016

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information:

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage at: www.Ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata>) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. iv + 8 pp. + Appendix vii + 28 pp. Adoption of Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) in Canada (Environment Canada 2014).

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016

ISBN 978-1-4606-7412-3 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4606-6935-8 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée «Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007», n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@Ontario.ca.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Dense Blazing Star was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

The Endangered Species Act, (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The species is also listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) in Canada in 2014 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

There has been extensive transplantation, monitoring, and research on Dense Blazing Star in the Windsor area, in association with construction projects such as that of the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway. New information on this species’ population abundance and habitat associations are provided.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Adoption of federal recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The species is also listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) in Canada in 2014 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Common name: Dense Blazing Star

Scientific name: Liatris spicata

SARO list classification: Threatened

SARO list history: Threatened (2008), Threatened – Not Regulated (2004)

COSEWIC assessment history: Threatened (2010), Threatened (2001), Special Concern (1988)

SARA Schedule 1: Threatened (2003)

Conservation status rankings: GRANK: G5, NRANK: N2, SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for technical terms, including the abbreviations above.

Distribution, abundance and population trends

In association with construction activities in Windsor, Ontario, extensive transplantation and monitoring work has been conducted on Dense Blazing Star. Monitoring during 2014 estimated 13,009 flowering plants and 63,516 vegetative (non-flowering) plants for a total of 76,525 Dense Blazing Star on restoration sites associated with the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway, many of which are planted or transplanted from native local origins (Amec Foster Wheeler 2015). Population estimates are derived from sub-sampling the Dense Blazing Star population using transect lines and sampling quadrats placed throughout each of the transplanted areas (i.e., planting sites). The number, health and reproduction (i.e. flowering) of plants that fall within the sample quadrats is evaluated as a representation of the entire population in the planting site. The average density of plants in the sample quadrats is then used to estimate the population within each respective planting site, as well as the general health and flowering of that local population of plants.

There are currently 25 tallgrass prairie restoration sites in Windsor containing transplanted Dense Blazing Star. These populations are monitored annually. Since monitoring began in 2011, the health of transplanted individuals has always been considered very good (based on a standardized scoring protocol). Other than wildlife browsing, there has been no other disturbance observed that would impact the health and reproduction of the plants. Every year a majority of plants observed exist in a vegetative or rosette form. Only up to 30 percent of the population produces flowering stalks, averaging one to two stalks per plant depending on the year. Prior estimates of population numbers based on flowering stalks only (i.e. reproductive plants only) may have underestimated the total number of individuals in a Dense Blazing Star population. The most recent population estimates reported for Essex Region which consider both flowering and vegetative plants represents a much larger population than that in the federal recovery strategy.

Habitat needs

Based on personal observation in the Ojibway Prairie Complex (Windsor, Ontario) and floral surveys in the Spring Garden Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI; Windsor, Ontario), Dense Blazing Star populations have been observed in the following vegetation communities beyond the community types listed in Section the Section on Suitable habitat of the federal recovery strategy (Barcza pers. comm. 2015).

- Deciduous Swamp: Oak Mineral Deciduous Swamp (SWD1); Swamp White Oak Deciduous Swamp (SWD1-1); and Pin Oak Deciduous Swamp (SWD1-3).

- Deciduous Forest: Fresh-Moist Poplar-Sassafras Deciduous Forest (FOD8).

In 2010, a study of existing site conditions of Dense Blazing Star populations was conducted within the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway highway footprint (LGL Limited and URS 2010). This was completed to determine which suitable Dense Blazing Star habitat would be required in the final restoration site selection. The following site conditions were found in the high quality Windsor Dense Blazing Star populations:

- Soils with a relatively deep, coarse A horizon (e.g., loamy medium sand, loamy fine sand, or silty fine sand), followed by a relatively deep, fine-textured B (B1/B2) horizon (e.g., silt loam, silty clay, clay, clay loam, and sandy clay).

- Dense Blazing Star growing within a range of soil moisture conditions between Moderately Fresh to Very Moist (1-6). Dense Blazing Star grows more abundantly in slightly higher soil moisture conditions from Moderately Moist to Very Moist (4-6).

- An absence of tree, shrub, tall forb, and grass competition. This includes non-native shrubs and native species such as Grey Dogwood (Cornus racemosa), which can quickly fill open remnant prairie to the detriment of Dense Blazing Star.

- Open exposure (full access to sun and lack of cover).

- Connectivity to other Dense Blazing Star habitat.

- An abundance of Dense Blazing Star-associated plant species, which include the following plant species encountered in close proximity to Dense Blazing Star within the study area:

- Arrow-leaved Aster (Symphyotrichum urophyllum)

- Arrow-leaved Violet (Viola sagittata)

- Biennial Gaura (Gaura biennis)

- Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii)

- Blood-red Milkwort (Polygala sanguinea)

- Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa)

- Clammy Ground-cherry (Physalis heterophylla)

- Colicroot (Aletris farinose)

- Common Scouring-rush (Equisetum hyemale)

- Early Goldenrod (Solidago juncea)

- Field Pussytoes (Antennaria neglecta)

- Flowering Spurge (Euphorbia corollata)

- Golden Ragwort (Packera aurea)

- Grass-leaved Goldenrod (Euthamia graminifolia)

- Gray Goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis)

- Gray-headed Coneflower (Ratibida pinnata)

- Groundnut (Apios americana)

- Heath Aster (Symphyotrichum ericoides)

- Indian Grass (Sorghastrum nutans)

- Large Purple Agalinis (Agalinis purpurea)

- Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium)

- Missouri Ironweed (Vernonia missurica)

- Northern Dewberry (Rubus flagellaris)

- Ohio Spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis)

- Pale-spiked Lobelia (Lobelia spicata)

- Pasture Thistle (Cirsium discolor)

- Pendulous Bulrush (Scirpus pendulus)

- Prairie Dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum)

- Prairie Rose (Rosa setigera)

- Riddell’s Goldenrod (Solidago riddellii)

- Rough Goldenrod (Solidago rugosa)

- Round-headed Bush-clover (Lespedeza capitata)

- Seed-box (Ludwigia alternifolia)

- Short-fruited Rush (Juncus brachycarpus)

- Showy Tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense)

- Skyblue Aster (Symphyotrichum oolentangiense)

- Slender-leaved Agalinis (Agalinis tenuifolia)

- Smooth Aster (Aster laevis)

- Stiff Goldenrod (Solidago rigida)

- Sullivant’s Milkweed (Asclepias sullivantii)

- Switch Grass (Panicum virgatum)

- Tall Tickseed (Coreopsis tripteris)

- Tall Wild Sunflower (Helianthus giganteus)

- Two-flowered Rush (Juncus biglumis)

- Virginia Broom-sedge (Andropogon virginicus)

- Virginia Culver’s-root (Veronicastrum virginicum)

- Virginia Mountain-mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum)

- Viscid Bushy Goldenrod (Euthamia gymnospermoides)

- Whorled Milkwort (Polygala verticillata)

- Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa)

- Winged Loosestrife (Lythrum alatum)

In Windsor’s shaded vegetation communities, Dense Blazing Star populations are confined to openings/gaps in the canopy, to human trails, or to edge habitat (Barcza pers. comm. 2015). Windsor populations have also responded well to vegetation removal, prescribed burns (Amec Foster Wheeler 2015), and the cessation of mowing (Barcza pers. comm. 2015). For example, in the footprint of the highway, an old orchard field was regularly mown at Todd Lane and Huron Church Road in Windsor. After mowing was halted in 2006, a few Dense Blazing Star individuals were visible. By 2008 there were 404 individuals, by 2009 there were 716 individuals, and by 2012 there were approximately 15,115 Dense Blazing Star individuals, the majority of which were vegetative (i.e., non-flowering) plants (Amec Foster Wheeler 2012). Although the population sampling techniques differed from 2008/2009 to 2012, this increase in abundance indicates how well a Dense Blazing Star population can recover once mowing was halted (Barcza pers. comm. 2015).

Recovery actions completed or underway

The recovery strategy states that restoration of several historical location of tallgrass habitat is being undertaken by the Rural Lambton Stewardship Network. Ontario Nativescape, a division of the Rural Lambton Stewardship Network, is an incorporated, not-for-profit organization that has been assisting in restoration projects since 2013.

Transplantation, monitoring, and research of Dense Blazing Star has proceeded as part of Windsor’s International Bridge Crossing and Plaza Project and construction of the Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway. The monitoring reports for the Parkway document Ontario’s most comprehensive study on Dense Blazing Star (Amec Foster Wheeler 2015). For example, approximately 21,909 plants were transplanted from construction areas using a variety of techniques, from prairie sod transplantation from higher quality sites to the removal and planting of corms from lower quality sites (i.e., to eliminate the risk of transferring invasive species with Dense Blazing Star to restoration habitats). In addition to field transplantation, 68,957 Dense Blazing Star plugs were produced at St. Williams Nursery and Ecology Centre, from seed collected from the Parkway population. Field transplantations primarily occurred during the dormancy period (i.e., late October to April) in 2011 and 2012, and plugs were planted in early June 2012. To date, there have been healthy, reproducing individuals of these plants noted in each of the transplant sites. The most recent population estimates represent between one percent to over 100 percent of the original baseline transplanted/planted population, indicating varying survivorship and in some cases, high recruitment, depending on the site. It is also important to note that population estimates fluctuate from year to year, but overall, have increased since 2011.

The Dense Blazing Star populations in Windsor are subject to vegetation management to maintain open tallgrass prairie habitat. There are 25 tallgrass prairie restoration sites containing transplanted Dense Blazing Star. Extensive brush cutting was conducted in the winter of 2010 to open sites for subsequent transplanting. Since 2012, all but two of these sites have been subject to at least one prescribed burn. Targeted invasive species control has also occurred annually and includes brush cutting (e.g. Autumn Olive, Black Locust and Tree-of-heaven), herbicide application (e.g., European Common Reed, Garlic Mustard and Canada Thistle) and hand pulling (e.g., Purple Loosestrife and Garlic Mustard). Appropriately timed applications of herbicide (i.e., early spring and fall) and the use of hand picking have proven successful in controlling the spread of invasive shrubs and forbs while mitigating the risk to Dense Blazing Star and other sensitive plant species. Monitoring results also indicate that without regular woody species management, the tallgrass prairie habitat in Windsor is threatened by encroachment of both native and exotic shrubs within three to four years.

Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below will be one of many sources considered by the Minister, including information that may become newly available following completion of the recovery strategy, when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Findings from monitoring and restoration activities associated with Windsor construction projects (Habitat Needs section above) should be considered when developing a habitat regulation.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

NR = not yet ranked

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Amec Foster Wheeler Environmental and Infrastructure, environmental consultants on behalf of the Parkway Infrastructure Constructors and Windsor Essex Mobility Group. 2015. Plant species at risk 2014 annual monitoring report Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkwaycreated to meet the conditions of permits No. AY-B-004-09; AY-C-001-09; AY-D-001-09; and AY- C-004-11 Issued under authority of clause 17(c)(d) of the Endangered Species Act (2007).173 pp.

Amec Foster Wheeler Environmental and Infrastructure, environmental consultants on behalf of the Parkway Infrastructure Constructors and Windsor Essex Mobility Group. 2012. Dense Blazing Star 2012 annual monitoring report Rt. Hon. Herb Gray Parkway created to meet conditions of permits No. AY-B-004-09; AY-C-001-09; AY-D-001-09; and AY- C-004-11 Issued under authority of clause 17(2)(d) of the Endangered Species Act, 2007. 158 pp.

Barcza, Dan. pers. comm. 2015. Email correspondence with Ontario Ministry of Transporation and Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, July 2015. Terrestrial and Restoration Ecologist, Sage Earth Environmental and Restoration Services, Palgrave, Ontario.

LGL Limited and URS. 2010. Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) management, monitoring and habitat restoration plan created to meet conditions of permit number: AY-D-001-09, issued under s. 17 (2) (d) of the Endangered Species Act, 2007. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Transportation. 184 pp.

Appendix 1. Recovery strategy for the Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) in Canada - 2014

Species at Risk Act

Recovery Strategy Series

Dense Blazing Star

2014

Document information

Recommended citation:

Environment Canada. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) in Canada - 2014. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vi + 28 pp.

Additional copies:

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry 1

Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement du liatris à épi (Liatris spicata) au Canada - 2014 »

Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-100-25397-8

Catalogue no. En3-4/193-2015F-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996)2 agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years.

The Minister of the Environment is the competent minister for the recovery of the Dense Blazing Star and has prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. It has been prepared in cooperation with the Province of Ontario.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Dense Blazing Star and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Acknowledgments

This version of the recovery strategy was prepared by Judith Jones, Winter Spider Eco-Consulting. The Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) Aylmer District provided records of Dense Blazing Star. Thanks are extended to Ron Ludolph for data from the Rural Lambton Stewardship Network and to Nature Conservancy Canada for data on the Port Franks population. The original draft of this recovery strategy was developed by the Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Team, Al Harris (Northern Bioscience), Gerry Waldron (consulting ecologist), and Carl Rothfels (Duke University) with input from John Ambrose (Cercis Consulting), Jane Bowles (University of Western Ontario), Allen Woodliffe (OMNR), Peter Carson (Pterophylla), Graham Buck (Brant Resource Stewardship Network), and Ken Tuininga (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario). Ken Tuininga, Angela Darwin, and Rachel deCatanzaro (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) provided further revisions to the recovery strategy. Contributions from Susan Humphrey, Lesley Dunn, Barbara Slezak, Madeline Austen and Marie Archambault (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) are also gratefully acknowledged.Acknowledgment and thanks is given to all other parties that provided advice and input used to help inform the development of this recovery strategy including various Aboriginal organizations and individuals, individual citizens, and stakeholders who provided input and/or participated in consultation meetings.

Executive summary

Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) is an herbaceous perennial reaching up to 2 m in height with a dense, showy spike of purple (occasionally white) flowers. Flowering occurs from mid-July to mid-September. Cultivated strains of the species have been bred for use in the floral trade and as ornamentals in gardens.

There are at least 10 extant native populations of Dense Blazing Star in Canada, comprised of over 70 000 plants in total, and a number of additional populations have been planted from native seed stock. All populations are in southwestern Ontario. At least 13 additional populations are considered historical or are presumed to be extirpated. There are also at least seven populations that have originated from human-influenced dispersal mechanisms and/or that are of introduced origin in Ontario and Quebec. Introduced populations cannot be considered for recovery if the seed source is unknown because, without genetic analysis, it is unknown whether the individuals carry the native genotype adapted to Ontario habitats or if they carry traits that could weaken the survival of the species in Canada. The species is listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). It is also listed as Threatened in Ontario under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007).

Loss of habitat due to development and agriculture and a decline in habitat quality resulting from fire suppression and alteration of the hydrologic regime are primary threats to Dense Blazing Star. Other threats include invasive plants, fenced exclosures, herbicide use, maintenance activities (mowing and vegetation clearing), picking, trampling, off-road vehicle use, and hybridization with other species of Blazing Star. Given that the species is found at the northern edge of its range and has a naturally limited distribution in Canada, it will likely always be vulnerable to human-induced and natural stressors.

There are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of Dense Blazing Star. In keeping with the precautionary principle, this recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA, as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible. The population and distribution objective is to maintain, or to increase to the extent that it is biologically and technically feasible, the current overall abundance of Dense Blazing Star (of native genotype) in Canada across at least 10 populations within its native range. Broad strategies to be taken to address the threats to the survival and recovery of Dense Blazing Star are presented in the section on Strategic Direction for Recovery.

Critical habitat for Dense Blazing Star is partially identified in this recovery strategy, based on the best available data. Critical habitat for Dense Blazing Star is located entirely on non-federal land. As more information becomes available, additional critical habitat may be identified and may be described within an area-based, multi-species at risk action plan developed in collaboration with the Walpole Island First Nation.

One or more such action plans for Dense Blazing Star will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by December 2021.

Recovery feasibility summary

Based on the following four criteria outlined in the draft SARA policies (Government of Canada 2009), there are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Dense Blazing Star. In keeping with the precautionary principle, this recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA, as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the uncertainties surrounding the feasibility of recovery.

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance

Yes. There are at least 10 extant native populations of Dense Blazing Star in Canada, comprised of over 70 000 plants in total, and a number of additional populations have been planted from native seed stock. As well, native sourced seed is available for restoration from several growers, and the species appears capable of establishment and reproduction.

- Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Unknown. While Dense Blazing Star can sometimes become established in meadows, interdunal areas, roadside ditches, utility corridors, railways, and other habitats with periodic disturbance, it primarily inhabits tallgrass prairie, which is extremely limited within the Canadian range of this species. Restoration of historical tallgrass prairie sites may be possible, or it may be feasible to establish the species in suitable habitat in proximity to historical tallgrass prairie sites; however, it is unclear whether sufficient tallgrass prairie habitat is or can be made available to support recovery of Dense Blazing Star in Canada.

- The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Unknown. The primary threats to this species include land development (residential, commercial, and agricultural), alteration of the fire and hydrologic regimes, and invasive plants. Outreach and stewardship activities may help to avoid or mitigate threats such as land development and alteration of the hydrologic regime on private or corporate land. Management actions may also help to mitigate the threat of habitat succession due to fire suppression. Some populations have a controlled burning regime in place, but this is not yet set up for all populations and assessing the feasibility of using controlled burns is proposed as a recovery approach. It is unknown if other significant threats such as invasive species can be mitigated to the extent required to ensure the long-term persistence of the species in Canada.

- Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

Yes. Dense Blazing Star can be direct-seeded successfully, either into cultivated ground or established turf. It may also be possible to undertake vegetative propagation from bulblets formed at the base of the stems and from stem cuttings (Waldron pers. comm. 2010). The species responds favorably to prescribed burns, with the peak in flowering occurring in the first or second year following a burn.

In Canada, Dense Blazing Star occurs at the northern edge of its North American range; the species has likely always been rare in Ontario. Due to Dense Blazing Star’s naturally limited distribution in Canada, it will likely always be vulnerable to human-induced and natural stressors.

COSEWIC species assessment information

Date of Assessment: April 2010

Common Name (population): Dense Blazing Star

Scientific Name: Liatris spicata

COSEWIC Status: Threatened

Reason for Designation: This showy perennial herb is restricted in Canada to a few remnant tallgrass prairie habitats in southwestern Ontario. A variety of threats, including lack of consistent application of fire to control the spread of woody species, spread of invasive plants, loss of habitat to agriculture and development and various management practices, including mowing, have placed the species at continued risk.

Canadian Occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Special Concern in April 1988. Status re-examined and designated Threatened in May 2001. Status re- examined and confirmed in April 2010.

Species status information

Globally, Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) is regarded as Secure 3 (G5) (NatureServe 2011). In the United States it is ranked nationally as Apparently Secure 4 (N4). It is ranked Presumed Extirpated 5 (SX) in District of Columbia and Missouri; Critically Imperilled 6 (S1) in Delaware and Maryland; Vulnerable 7 (S3) in Wisconsin, West Virginia, and North Carolina (S3?); and Apparently Secure, Secure, or Unranked 8 (S4, S5, SNR) in 19 additional states (Appendix B).

In Canada, Dense Blazing Star is ranked Imperilled 9 both nationally (N2) and provincially in Ontario (S2). The species is not listed in Quebec where it is considered adventive 10 or introduced and a rank is not applicable 11 (SNA). Dense Blazing Star is listed as Threatened 12 on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). It is also listed as Threatened 13 under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007).

The percentage of the global range found in Canada is estimated to be less than 1% (NatureServe 2011). The distribution of Dense Blazing Star is very restricted in Canada, where it occurs at the northern edge of its North American range.

Species information

Species description

Dense Blazing Star is an herbaceous perennial reaching up to 2 m in height with a dense spike of compound heads of 4 to 18 purple (occasionally white) flowers. The species blooms from mid-July to mid-September. The stems 14 emerge singly or in clusters from a woody bulb-like structure. The leaves are spirally arranged. The lower leaves are 10 to 40 cm long and 0.5 to 2.0 cm wide, and they become smaller toward the flower spike. The fruit is brown or black, somewhat cylindrical, ribbed, 4 to 6 mm long with barbed bristles at the summit (Cronquist 1991). Native Canadian plants are of the variety spicata. Another variety, resinosa, occurs in the southeastern United States (NatureServe 2011). Cultivated strains have been bred for use in the floral trade and as ornamentals in gardens.

Populations and distribution

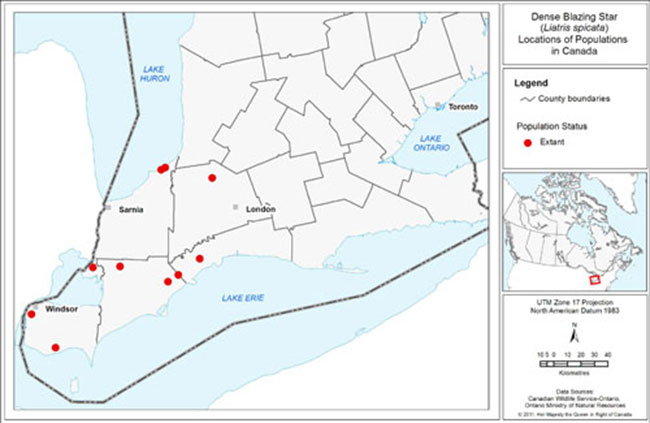

Globally, Dense Blazing Star is restricted to eastern North America. In the United States, its range extends from Massachusetts to Florida, west to Wisconsin and Louisiana (Figure 1). The Canadian range of Dense Blazing Star (extant native populations) is shown in Figure 2.

COSEWIC (2010) documented 10 extant native populations of Dense Blazing Star in Canada (Table 1), all in southwestern Ontario. Together, they consist of upwards of 140 000 flowering stems (or roughly 70 000 plants). Most plants (>80% of the individuals in the Canadian population) have been found on Walpole Island First Nation (WIFN), where abundance was estimated at >120 000 flowering stems in 2008 (COSEWIC 2010). Four of the populations consisted of fewer than 10 flowering stems in 2008 and are probably not viable in the long-term (COSEWIC 2010). Thirteen additional populations are now presumed or known to be extirpated (Appendix C). Additional plants have been reported at a non-historical site in 2011 that have not been confirmed to be native (Haggeman pers. comm. 2011). The Canadian Index of Area of Occupancy (IAO) 15 was estimated to be 172 km2 in 2008 calculated on the basis of extant native populations only (COSEWIC 2010).

Figure 1. North American Distribution of Dense Blazing Star (range distribution based on Royal Ontario Museum (2011), and subnational (state or province) status ranks based on NatureServe (2011)).

Figure 2. The Canadian range of Dense Blazing Star showing known extant native populations only. For a full list of populations, including those that are introduced or of unknown origin or status, see Table 1. For a list of extirpated and historic populations, see Appendix C.

In addition to native populations, there are several populations of Dense Blazing Star that may have originated from human-influenced dispersal mechanisms and/or that were introduced outside the species' native range in Canada. Some of these populations may have resulted from seeds that dispersed along railway tracks, and some populations may have been intentionally planted. In Ontario, populations at East Point Conservation Area (Scarborough), Kingston, and in the Kenora District west of Dryden (Harris pers. comm. 2010), may have originated from garden escapes or garden refuse, as may also be the case at Oka, Quebec. The actual seed source of these populations is unknown, so without genetic analysis it is impossible to say whether these individuals carry the native genotype adapted to natural Ontario habitats or whether they could be a source of unsuitable traits that could weaken the survival of the species in Canada (see Threats). Without genetic information, these populations cannot be considered targets for recovery.

The origin and status of the population located at Bronte Creek Provincial Park (Halton Region) are unknown. There are no historical botanical records for the population, but the population was found in natural prairie habitat and is considered native by the Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) (Oldham pers. comm. 2007 cited in COSEWIC 2010). It consisted of a single plant in 1998, and while it was not searched in 2008 its persistence is doubtful (COSEWIC 2010).

Restoration of several historical locations of tallgrass habitat is being undertaken by the Rural Lambton Stewardship Network (RLSN). Up until 2008, many seed mixes included Dense Blazing Star from a known native seed source, and the restorations can therefore be considered to contribute to the recovery of the species. As of 2008, native-sourced Dense Blazing Star had been planted at more than 105 sites 16 in Lambton County (Ludolph pers. comm. 2010). Data from all the sites have not been compiled, and although observations at some sites indicate that Dense Blazing Star has successfully established (Lozon 2012), monitoring is needed to determine the extent to which the species has become established and how many separate populations have resulted; therefore, populations are not listed individually in Table 1. Within the Ojibway Prairie Complex and surrounding areas the portions of several subpopulations that were formerly located in the federal Plaza site, part of the Detroit International Crossing (DRIC), and in the corridor being developed for the Right Honourable Herb Gray Parkway (HGP) were removed and transplanted to restoration sites under SARA and ESA 2007 permits respectively. During implementation of mitigation measures for the HGP actual stem abundance was found to be higher than previous estimates and mitigation required under ESA 2007 and SARA permits for both the HGP and the federal Plaza site required additional plants be propagated and planted at their respective restoration sites.With this in mind, the abundance information in Table 1 is quickly dated and subject to change and the restoration sites will require further surveys once the transplanted plants have had time to establish.

Table1. List of dense blazing star populations in Canada

| Population type | Canadian populations | County or regional municipality | Last observed | Abundancea at last observation | Statusb | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extant native populations | 1. Port Franks ANSI c | Lambton | 2008 | 54 stems | Extant | |

| Extant native populations | 2. Walpole Island First Nation | Lambton | 2008 | >120 000 stems | Extant | |

| Extant native populations | 3. Pinery Provincial Park | Lambton | 2011 | ~2 100 stems (in 2008) |

Extant | |

| Extant native populations | 4. Dutton Prairie | Elgin | 2008 | ~400 stems | Extant | |

| Extant native populations | 5. Ojibway Prairie Complex and surrounding areasd | Essex | 2010 | 14000 to 20000 stems in >13 subpopulations |

Extant | |

| Extant native populations | 6. Cedar Creek | Essex | 2008 | 67 stems | Extant | |

| Extant native populations | 7.Tupperville | Chatham-Kent | 2008 | 1 stem | Extant | Presumed native; Along a railway |

| Extant native populations | 8. Highgate | Chatham-Kent | 2008 | 6 stems | Extant | Presumed native; Along a railway |

| Extant native populations | 9. Muirkurk northeast of Highgate | Chatham-Kent | 2008 | 3 stems | Extant | Presumed native; Along a railway |

| Extant native populations | 10. Lucan | Middlesex | 2008 | 6 stems | Extant | Presumed native, although thought by some to be introduced; Along a railway |

| Planted populations at restoration sites (native seed source) | Rural Lambton Stewardship Network restoration sites | Lambton | 2010 | More than 105 sites | To be confirmed | Known native seed source |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Edwards Lake, Ontario | Kenora District | 2003 | 20 stems | Extant | Derived from garden escapes but occurs in natural habitat |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Westhill | York Region | 2001 | "thriving" | Presumed extant | "Introduced outside natural range" (COSEWIC 2010). |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Oka, Quebec | Deux-Montagnes | Unknown | No information | Presumed extant | Listed as SNA (introduced)(NatureServe 2010) |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Fort Erie | Niagara Region | 2000 | ~200 plants | Unknown | May be an introduced population; Along a railway |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Cofell Line Prairie | Chatham-Kent | 2000 | 1 plant | Unknown | Not seen in 2008 but some areas not searched; Along a railway |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Bronte Creek Provincial Park | Halton Region | 1998 | 1 plant; 5 rosettese | Unknown | Origin unknown (possibly adventive) but occurs in prairie habitat; Not searched in 2008 |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | Highland Hotel, Kingston | Frontenac County | 1976 | No information | Unknown | Introduced population derived from garden escapes |

| Introduced populations and populations of unknown origin or status | East Point Park, Scarborough | Toronto Metropolitan | Unknown | No information | Unknown | May be an introduced population; Along a railway |

Sources: (Allen 2001; COSEWIC 2010; Ludolph pers. comm. 2010; NatureServe 2010; NHIC 2011).

aAbundance information is reported using either the number of individuals (number of plants) or the stem count, depending on the source of the data. Both measures are not available for all sites.

bSubject to change

cArea of Natural and Scientific Interest

dPortions of several subpopulations were on the federal Plaza site and within the Endangered Species Act, 2007 permit boundary for the HGP and transplanted to restoration sites. Estimated abundance and extent of occurrence may be subject to change.

eA rosette consists of leaflets with no flowering stalk

Needs of the dense blazing star

In Canada, Dense Blazing Star primarily inhabits tallgrass prairie, although some plants occur in wetlands, meadows, thickets, interdunal areas, roadside ditches, and along utility corridors and railways (COSEWIC 2010). It occurs on moist to wet sandy soil with neutral to basic pH. Unlike the other two native Liatris species (L. asperaand L. cylindracea), Dense Blazing Star rarely grows in dry conditions (Voss 1996). The species may also be found in the openings of savannas or open woodlands dominated by oaks (Quercus palustris, Q. macrocarpa, Q. bicolor, Q. rubra,and Q. alba) and hickories (Carya ovata, C. glabraand C. laciniosa).In its greater global range, Dense Blazing Star has been known to inhabit fields, road banks, fencerows, lakesides, wet to moist prairies and meadows, bogs, seepages, dunes, limestone and granite outcrops, sandy clays, sandy loams, moist woods, oak, oak-pine, and sweetgum flats, and tamarack swamps (Nesom 2006).

Dense Blazing Star is intolerant of shading and cannot compete with dense growths of other forbs or with woody species. It is dependent on disturbance to maintain the open habitat. The number of flowering stems can vary from year to year, sometimes in response to fire. When the habitat becomes too shady, the stems may become spindly and crooked, and the plants eventually may not flower at all, but may persist (above ground) in a non-flowering/vegetative state for quite some time until the light conditions become more favourable. In the Windsor area, when shrubby thickets have been opened up, flowering stems have re-appeared (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2010).

In areas that are burned, the peak number of flowering stems generally occurs in the first or second year following a burn. After a few years, if the vegetation or thatch gets too thick, flowering may diminish until after the next burn. It has been suggested that burning every 3 to 4years would be ideal, but that if the prairie becomes very overgrown, more frequent fires may be needed to return the prairie to conditions optimal for Dense Blazing Star (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2010). High numbers of plants are found in areas that have been burned (i.e., Windsor, Ojibway Prairie, and Walpole Island First Nation) (Allen 1988). However, some other areas that remain open due to human disturbance also provide suitable habitat.

The existence of populations that were introduced far outside the range of tallgrass prairie, such as the Oka, Quebec population (Table 1), shows the species is able to tolerate a range of climatic conditions. Bees, butterflies and beetles are known to pollinate the flowers. The plants are self-compatible but self-pollination rarely takes place. The seeds are wind-dispersed (Molano-Flores 2002).

Threats

Threat assessment

Table 2. Threat assessment table

Habitat loss or degradationd

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residential, commercial, and industrial development | High | Widespread | Historical / Anticipated | Recurrents | High | High |

| Agricultural development | High | Localized | Historical / Current | Recurrent | High | High |

| Shoreline erosion | Medium | Localized | Current | Recurrent | Medium | Medium |

Changes in ecological dynamics or natural processd

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alteration of the fire regime | High | Widespread | Current | Continuous | High | Medium |

| Alteration of the hydrologic regime | High | Localized | Current | Continuous | High | Medium |

Exotic, invasive, or introduced species/genomed

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive plants | High | Widespread | Current | Continuous | High | High |

| Fenced exclosures | Medium | Localized | Current | Continuous | Medium | High |

| Hybridization and genetic erosion17 | Medium | Widespread | Current | Continuous | Medium | Medium |

Accidental mortalityd

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Herbicide use | Medium | Localized | Historical / Anticipated | Recurrent | Unknown | Medium |

| Maintenance activities (Mowing and vegetation clearing) | Medium | Localized | Current | Continuous | Medium | Medium |

Disturbance or harmd

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Off-road vehicle use and other recreational activitiess | Medium | Widespread | Current | Unknown | Medium | Medium |

| Trampling and picking | Medium | Localized | Current | Recurrent | Medium | High |

Sources: (COSEWIC (2010), Woodliffe (pers. comm. 2010); Pratt (pers. comm. 2010); Jacobs (pers. comm. 2010), and direct observations by members of the Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Team).

aLevel of Concern: signifies that managing the threat is of (high, medium or low) concern for the recovery of the species, consistent with the population and distribution objectives. This criterion considers the assessment of all the information in the table.

bSeverity: reflects the population-level effect (High: very large population-level effect, Moderate, Low, Unknown).

cCausal certainty: reflects the degree of evidence that is known for the threat (High: available evidence strongly links the threat to stresses on population viability; Medium: there is a correlation between the threat and population viability e.g. expert opinion; Low: the threat is assumed or plausible).

dThreat categories are listed in order of decreasing significance.

Description of threats

Residential, commercial, and industrial development

Tallgrass communities (including prairie and savanna) once covered between 800 km2 and 2000 km2 of southern Ontario (Rodger 1998). Today, approximately 21 km 2 remains due to urbanization and conversion for agricultural use (Bakowsky and Riley 1994; Rodger and Woodliffe 2001); this represents less than 3% of its original extent.

Most populations of Dense Blazing Star in Canada are in open areas that are vulnerable to residential, commercial, and industrial development. The threat of residential, commercial and industrial development is high in southwestern Ontario (e.g., the LaSalle and West Windsor area). On Walpole Island First Nation, increased housing construction, in response to critical housing shortages, has resulted in the loss of suitable habitat for Dense Blazing Star (COSEWIC 2010).

Agricultural development

Several populations of Dense Blazing Star have been extirpated as a result of habitat loss due to conversion to agricultural fields, and this continues to be an ongoing threat (COSEWIC 2010). This is especially true at Walpole Island First Nation, where agricultural development has occurred at several sites in the last 10 years, and continues to be a potential threat on many land parcels (COSEWIC 2010).

Alteration of the fire regime

Dense Blazing Star requires open habitat, and all populations are vulnerable to shading resulting from growth of trees and shrubs. The natural wildfires that once controlled woody growth and maintained open prairie habitat are now generally suppressed. Thus, natural succession is a potential threat at all sites and is implicated in the extirpation of at least three populations (COSEWIC 2010). Prescribed burning is conducted at the Ojibway Prairie complex, parts of Walpole Island First Nation, and Pinery Provincial Park, but would be needed at other sites to arrest succession to woody vegetation species.

Alteration of the hydrologic regime

Some populations are threatened by habitat degradation from changes in drainage that alter soil properties. Installation of drainage tiles and ditches for agriculture has altered the hydrologic regime at some sites and was possibly the cause of extirpation of several populations between the St. Clair River and the mouth of the Thames River.

Invasive plants

Invasive species are a widespread threat to Dense Blazing Star. European Common Reed (Phragmites australisssp. australis) invasion is believed to be the primary cause of extirpation of three populations and is a current threat to the Windsor, Port Franks and Walpole Island First Nation populations, where it is invading meadow marshes and moist prairies (Allen 2001; COSEWIC 2010). Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and White Sweet Clover (Melilotus alba) are also implicated in several extirpations (COSEWIC 2010).

Fenced exclosures

Several fenced exclosures were established at Pinery Provincial Park in the 1980s to protect Dense Blazing Star, Bluehearts (Buchnera americana), and the wet meadows from trampling and herbivory by White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus). Although additional deer control measures have since been put in place, the exclosures remain. Currently, browsing by deer outside the exclosures may help to maintain open conditions, while within the fenced areas Dense Blazing Star is declining due to encroachment by woody species (COSEWIC 2010).

Shoreline erosion

One Dense Blazing Star site on the Walpole Island First Nation may be threatened by shoreline erosion due to wave action along the St. Clair River. (COSEWIC 2010; C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2012).

Hybridization and genetic erosion

Hybridization of Dense Blazing Star with native Rough Blazing Star (Liatris aspera) and non-native Prairie Blazing Star (L. pycnostachya) as well as cultivated varieties of L. spicatahas been documented. L. spicata x L. aspera hybrids have been recorded on Walpole Island First Nation (COSEWIC 2010). Furthermore, nursery stock of uncertain genetic origin is sometimes used by some organizations during prairie restoration work. Hybridization may introduce contamination into the gene pool. For example, traits bred into ornamental strains to improve suitability for the floral trade, such as earlier blooming, larger flowers, etc. may reduce the ability of the species to survive and reproduce in its natural Canadian habitats.

Herbicide use

Herbicide spraying, often to control invasive species (e.g., those listed above) is likely a threat to some populations of Dense Blazing Star. The extirpation of the Patrick Cove population was likely related to the heavy herbicide use in Dover Township, which had lead to loss of prairie forbs18 and many leafy herbs in the area (Allen 1998). It also threatens other populations that are on roadsides and railway embankments that are sprayed as part of right-of-way maintenance.

Maintenance activities (mowing and vegetation clearing)

Regular (or poorly-timed) mowing and seeding is another threat that may be associated with both development and agriculture, and was the cause of the extirpation of the Rumble Prairie population. At Dutton Prairie, vegetation clearing and soil scarification under a hydro right-of-way is believed to be the cause of the large decline in the Dense Blazing Star population that has occurred since the 1980s (COSEWIC 2010).

Off-road vehicle use and other recreational activities

Because most populations of Dense Blazing Star in Canada occupy open ground that is vulnerable to residential and commercial development, this species is also vulnerable to impacts from recreational activities such as off-road vehicle use and hiking that result from proximity to developed landscapes.

Trampling and picking

At Pinery Provincial Park, while some Dense Blazing Star plants occur in nature reserves, others occur within an active campground and suffer from trampling and plant collection. Trampling is also a concern to a lesser extent on Walpole Island First Nation (COSEWIC 2010).

Population and distribution objectives

In the wild in Canada, most Dense Blazing Star plants occur in areas with tallgrass prairie associates (COSEWIC 2010), suggesting that maintaining and restoring tallgrass prairie habitat is key to successful recovery. Given the widespread, possibly irreversible loss of tallgrass prairie habitat in southern Ontario, in combination with threats such as invasive species, and its naturally restricted range, it is unknown whether it is feasible to fully recover Dense Blazing Star in Canada. The population and distribution objective is therefore to maintain, or to increase to the extent that it is biologically and technically feasible, the current overall abundance of Dense Blazing Star (of native genotype) in Canada across at least 10 populations within its native range.

Achieving the objective may involve population augmentation at some known extant locations where population viability is believed to be low, provided sufficient suitable habitat is available or can be made available to support long-term persistence, or alternatively, it may involve re-establishing populations at historic sites, and/or introducing new populations to sites with suitable habitat within the native range of the species.

Broad strategies and general approaches to meet objectives

Actions already completed or currently underway

Population inventory and habitat descriptions for most locations were completed in 2008 for an update COSEWIC status report (COSEWIC 2010). The Walpole Island Heritage Centre has monitored populations of Dense Blazing Star on Walpole Island First Nation. A census of the population was performed in 2003 and 2008 (COSEWIC 2010).

The provincially and municipally protected areas of Ojibway Prairie Provincial Nature Reserve, Tallgrass Prairie Heritage Park, Spring Garden Natural Area, and Pinery Provincial Park have active burn programs. Burns have also occasionally been undertaken at Dutton Prairie. Some prairie and savannah habitat is burned every year by Walpole Island First Nation community members.

Efforts by the Walpole Island Heritage Centre to lease lands for conservation have resulted in a reduction in the rate of conversion of prairie and savannah habitat to agriculture (COSEWIC 2009) during the tenure of the 5-year leases.The Walpole Island Land Trust was established in 2008 to conserve land on the Walpole Island First Nation (Jones 2013). Over 300 acres of land with tallgrass prairie, oak savannah and forest habitats have been acquired since 2001 for conservation (Jacobs 2011), benefitting species at risk such as Dense Blazing Star.

Recovery actions described in the Draft Walpole Island Ecosystem Recovery Strategy (Bowles 2005) included raising awareness in the community about species at risk, including Dense Blazing Star. Pamphlets, calendars, newsletter articles, posters and other promotional material have been used to raise awareness of species at risk in the Walpole Island First Nation community.

The Walpole Island First Nation is currently developing an ecosystem protection plan based on the community’s traditional ecological knowledge (TEK).

In the Windsor area, the development of the DRIC and the HGP involves the construction of a divided multi-lane highway with on-ramps, overpasses, Plaza site, and ditches that affected a portion of a Dense Blazing Star population (Ojibway Prairie and surrounding areas population). As part of the mitigation for the HGP all impacted Dense Blazing Star plants have been transplanted to restoration sites established in appropriate habitat adjacent to the HGP footprint under an Endangered Species Act, 2007 permit. Seed collected from Dense Blazing Star plants within the HGP footprint has also been propagated and planted into the restoration sites. Under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 permit, all planted and transplanted individuals are being monitored from the time of planting until five years after construction is completed (LGL Ltd and URS 2010). A management plan has been developed that includes invasive species management techniques at the restoration sites and adaptive management strategies. Mitigation measures for Dense Blazing Star occurring at the DRIC Plaza site (federal land) have been implemented under Species at Risk Act and Canada Wildlife Act permits. All Dense Blazing Star plants in addition to approximately 3,200 m2 of prairie sod within the DRIC footprint have been removed from the Plaza site and transplanted to the St.Clair National Wildlife Area. The transplants will be monitored and managed under permit for five years.

Strategic Direction for Recovery

Table 3. Recovery planning table

| Threat or limitation | Priority | Broad strategy to recovery | General description of research and management approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| All threats | High | Monitor populations and habitat |

|

| Residential commercial, and industrial development; Agricultural development; and Off-road vehicle use | High | Protection and stewardship |

|

| Invasive plants; Alteration of the fire regime | High | Habitat management |

|

| All threats | Medium | Outreach and education |

|

| Hybridization and genetic erosion; Knowledge gaps | Medium | Conduct research |

|

| Shoreline Erosion; Alteration of the hydrologic regime | Medium | Habitat Management |

|

| Small population size and distribution | Low | Assess the feasibility of reintroduction, introduction, and population augmentation |

|

Critical habitat

Identification of the species' critical habitat

Critical habitat for Dense Blazing Star is identified in this recovery strategy to the extent possible based on the best available information. It is recognized that the critical habitat identified below is insufficient to achieve the population and distribution objectives for the species. The Schedule of Studies (Table 4) outlines the activities required for identification of additional critical habitat necessary to support the population and distribution objectives.

Sites where Dense Blazing Star has been planted or transplanted using a native seed source and as part of a restoration program will not be considered for critical habitat identification until it can be determined that the plantings are successful. Determination of restoration success will be measured through plant vigour and fitness, and successful sexual reproduction. Critical habitat may be identified at restoration sites following long-term monitoring to determine success, extent of suitable habitat and suitable habitat occupancy.

Suitable Habitat

Dense Blazing Star habitat is found on moist to wet sandy soil usually associated with tallgrass prairie habitat, but also in other open mesic (moderately moist) habitats. Suitable habitat for Dense Blazing Star is identified using the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) framework for Ontario (from Lee et al. 1998). This habitat has been documented (Woodliffe pers. comm. 2010; McFarlane pers. comm. 2010) to occur within the following ELC ecosite designations:

- Fresh-Moist Tallgrass Prairie (TPO2)

- Fresh-Moist Tallgrass Savannah (TPS2)

- Fresh-Moist Tallgrass Woodland (TPW2)

- Dry-Moist Cultural Meadow (CUM1)

- Mineral Cultural Thicket (CUT1)

- Mineral Cultural Savannah (CUS1)

- Mineral Cultural Woodland (CUW1)

- Ash Mineral Deciduous Swamp (SWD2)

- Maple Mineral Deciduous Swamp (SWD3)

- Mineral Thicket Swamp (SWT2)

- Mineral Meadow Marsh (MAM2)

- Organic Meadow Marsh (MAM3)

- Tallgrass Meadow Marsh (MAM6)

The ELC framework provides a standardized approach to the interpretation and delineation of dynamic ecosystem boundaries. The ELC approach classifies habitats not only by vegetation community but also considers hydrology and topography, and as such provides a basis for describing the ecosystem requirements of the natural habitat for Dense Blazing Star.

Within these habitat types, the vegetation immediately adjacent to Dense Blazing Star consists predominantly of herbaceous plants, especially grasses and sedges. Suitable habitat may be a large open area or a smaller opening within a woodland, forest, thicket, swamp, or meadow marsh. There may also be a history of fire or other disturbance that maintains the openness of the habitat.

Although only a small portion of the ELC ecosite polygon may be occupied, unoccupied area is required for dispersal, establishment, and expansion of the species to meet population and distribution objectives. Since the seeds of Dense Blazing Star are wind-dispersed, the species is capable of dispersing relatively long distances, and it frequently colonizes newly available habitat adjacent to a seed source (COSEWIC 2010). In addition, suitable habitat requires periodic disturbance, so the entire polygon is required to provide space for ecological processes that maintain habitat (such as fire, periodic flooding, etc.) to take place.

Suitable habitat occupancy

Suitable Habitat Occupancy Criterion: Suitable habitat is considered occupied when native Dense Blazing Star has been observed in any single year since 2006.

The boundary of occupied suitable habitat is defined by the extent of the ELC ecosite polygon (identified as suitable in the Section on Suitable habitat) in which the species occurs. Where two or more ELC ecosite polygons meeting the Suitable Habitat Occupancy Criterion are continuous (connected), they are combined and considered one site. In situations where Dense Blazing Star is observedin small openings not well defined by ELC (e.g. a small opening in a forest), a radial distance of up to 50 m from the Dense Blazing Star observations will be applied as the occupancy criterion.

Information from 2006-2010 (which represents the time period of information currently available to Environment Canada) is used in this document to determine habitat meeting the suitable habitat occupancy criterion. During this time period (2006-2010), adequate surveys were conducted for many known extant populations to provide the information necessary to identify critical habitat. Furthermore, the five-year period will protect sites where plants have not been seen recently but are highly likely to still be present. For reports prior to 2006, it cannot be assumed that the species is still present due to the high level of threats to open, tallgrass prairie habitats and to the high level of human activity in disturbed areas.

Any sites containing plants that are considered horticultural specimens, and those clearly planted in landscaped settings such as urban gardens, are not considered to be occupied for the purposes of identifying critical habitat.

Application of dense blazing star critical habitat criteria

Critical habitat for Dense Blazing Star is identified as the entire ELC ecosite polygon described as suitable in the Section on Suitable habitat that meets the suitable habitat occupancy criterion described in the Section on Suitable habitat occupancy. In addition, in order to maintain moisture regimes, allow natural processes to occur, and to protect the plants from impacts such as the encroachment of weeds or the use of herbicides, the habitat within a radial distance of up to 50 m from a Dense Blazing Star plant occurring in suitable habitat (including small opening not well defined by ELC) is also included as critical habitat. If a hard edge (e.g., paved road, building) occurs prior to the 50 m distance, critical habitat ends at the hard edge. At present, it is not clear at what distance physical and/or biological processes begin to negatively affect Dense Blazing Star. Studies on micro-environmental gradients at habitat edges, ed., light, temperature, litter moisture (Matlack 1993), and of edge effects on plants, as evidenced by changes in plant community structure and composition (Fraver 1994), have shown that edge effects could be detected up to 50 m into habitat fragments. As such, a 50 m distance from any Dense Blazing Star plant is appropriate to ensure microhabitat properties for rare plant species occurrences are incorporated in the identification of critical habitat. These additional areas identified as critical habitat (ed., those up to a radial distance of 50 m) may include habitat that is not considered suitable (as described in the section on Suitable habitat), such as forests, because Dense Blazing Star may be found along woodland edges or near the transition from suitable into unsuitable habitat. Maintained roadways or built-up features such as buildings do not assist in the maintenance of natural processes and are therefore not critical habitat.

Application of the critical habitat criteria to available information identifies 28 sites for five populations as critical habitat for Dense Blazing Star (Appendix D). It is important to note that the coordinates provided are a cartographic representation of where critical habitat sites can be found, presented at the level of a 1 km x 1 km grid and do not represent the extent or boundaries of the critical habitat itself. More detailed information on the location of critical habitat, to support protection of the species and its habitat, may be requested on a need-to-know basis by contacting Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service.

The identification of critical habitat in this recovery strategy is applied based on the information currently available to Environment Canada for the period of 2006-2010 (more recent data is not currently available) and is insufficient to meet the population and distribution objectives. As additional information becomes available, critical habitat identification may be refined or more sites meeting critical habitat criteria may be added.

Critical habitat is not identified for the following four extant populations: Tupperville, Highgate, Murkirk NE of Highgate, and Lucan. These populations occur on existing or old railway lines with very limited suitable habitat available and although the individuals are presumed to be of native source, they were likely transported to those locations by the railway. In addition, for each of these populations, there are fewer than 10 Dense Blazing Star stems and their viability in the long-term is doubtful (COSEWIC 2010). Additionally, although the Lucan population is presumed native some have suggested it may be introduced (COSEWIC 2010). Similarly, critical habitat is not identified for the Windsor railway site which is currently considered part of the Ojibway Prairie and surrounding areas population. It is approximately 4 km away from the other locations in this population and may have been transported to this location given it is along the railway. Although, critical habitat is not identified for these populations or specific sites, the individual plants may contain important genetic material for recovery and, depending on where they occur, are either protected under the prohibitions listed in the Species at Risk Act (on federal lands) or the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (on non-federal lands).

In addition, the information required to identify critical habitat for the population of Dense Blazing Star at Walpole Island First Nation is not available for use by Environment Canada. Although the continued presence of Dense Blazing Star has been confirmed (as in COSEWIC, 2010), the data required to satisfy the critical habitat criteria (i.e., location and extent of populations, biophysical habitat attributes), are not yet available to Environment Canada. Given the known historic and current threats to the species, confirmation of the location and extent of the Dense Blazing Star population on Walpole Island First Nation is required. Location data available for use by Environment Canada predates 2005, and evidence exists that indicates that certain threats may have impacted portions of the population (see the Section on Threat assessment) after that date. Confirming the biophysical habitat attributes (i.e., extent and amount of the ELC ecosite of suitable habitat (as listed in the Section on suitable habitat)) is also required for this population. Once adequate information is available for use, additional critical habitat may be identified and may be described within an area-based multi-species at risk action plan developed in collaboration with the Walpole Island First Nation.

The restoration areas for the DRIC Plaza site created under a Species at Risk Act permit and for the HGP created under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 permit, are not currently identified as critical habitat. All plants previously occurring inside the HGP footprint have been transplanted into existing suitable habitat (in some cases with existing, naturally occurring Dense Blazing Star) or restored habitat. The majority of these restoration sites occur within the Ojibway Prairie complex and surrounding areas. Additional plants were propagated and planted in the restoration sites. All Dense Blazing Star plants inside the DRIC Plaza site footprint were transplanted to the St. Clair National Wildlife Area’s Corsini Cell. Additional plants were propagated from seed and planted at this location as well. Once the restoration plantings have established both the DRIC and HGP restoration areas will be reviewed and additional critical habitat may be identified.

Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

Table 4: Schedule of studies

| Description of activity | Rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| In co-operation with Walpole Island First Nation confirm/obtain population information and conduct Ecological Land Classification for the Walpole Island population. | Location of population becomes known and habitat associations, biophysical habitat attributes and extent of suitable habitat are confirmed. | 2014-2019 |

| Confirm/obtain population and ELC information for Rural Lambton Stewardship Network, DRIC and HGP projects and any other restoration planting sites and determine the location and extent of the plantings and identify any additional critical habitat. | Locations of successful new or re-established populations becomes known and habitat associations, biophysical habitat attributes and extent of suitable habitat are confirmed and critical habitat is fully identified. | 2014-2019 |

Activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat were degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time (Government of Canada 2009). Activities described in Table 5 are examples of those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for the species, however, destructive activities are not necessarily limited to those listed.

Table 5. Activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

Measuring progress

The performance indicators presented below provide a means to define and measure progress toward achieving the population and distribution objectives. Every five years, the success of recovery strategy implementation will be measured against the following performance indicators:

- The abundance of Dense Blazing Star (of native genotype) in Canada has been maintained at its current level or has increased;

- There are at least 10 extant populations of Dense Blazing Star with the native genotype across its native range in Canada.

Statement on action plans

One or more action plans will be completed for Dense Blazing Star by December 2021.

References

Allen, G.M., 1988. Status report on the Dense Blazing Star Liatris spicata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 50pp.

Allen, G.M. 2001. Update COSEWIC status report on the dense blazing star Liatris spicata in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report of the dense blazing star in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa Pp 1-21.

Ambrose, J. and G. Waldron,in prep. Recovery Strategy for Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario. Draft prepared for the Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Team.

Bakowsky, W.D. and J.L. Riley. 1994. A survey of the prairies and savannas of southern Ontario,in R.G. Wickett, P.D. Lewis, A. Woodliffe, and P. Pratt (eds.) Proceedings of the Thirteenth North America Prairie Conference: pp. 7-16.