Eastern Flowering Dogwood Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the eastern flowering dogwood, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge onwhat is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA, 2007 outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA, 2007. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Bickerton, H. and M. Thompson-Black. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the Eastern Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi+ 21 pp.

Cover illustration: Wasyl Bakowsky

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2010

ISBN 978-1-4435-2089-8 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Authors

Holly Bickerton – Consulting Ecologist, Ottawa

Melinda Thompson-Black – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aurora District

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to John Ambrose, Eric Holzmueller, Barb Boysen, Mary Gartshore and Anita Imrie for providing background information and references.

Declaration

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has led the development of this recovery strategy for the Eastern Flowering Dogwood in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada - Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

Eastern Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida) is a small, showy tree native to the deciduous forest understorey of eastern North America. In Canada, it is found only in southwestern Ontario, where it was documented at 154 sites between 1975 and 2005. Eastern Flowering Dogwood is listed as an endangered species on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List and under Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Across its North American range, Eastern Flowering Dogwood is undergoing a steep population decline due to the dogwood anthracnose fungus (Discula destructiva). In Ontario, the rate of decline has been estimated at 7-8 percent annually. Other threats include forest succession, herbivory by White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), habitat loss, and insects and pests. These probably exacerbate the species' decline, but are relatively minor in comparison with the aggressive anthracnose fungus.

Eastern Flowering Dogwood is a species of the Ontario Carolinian forest. It occurs in a variety of vegetation communities, and is most commonly found in habitats ranging from open dry-mesic oak-hickory woodlands to mesic maple-beech eastern deciduous or mixed forests. Eastern Flowering Dogwood prefers mid-aged to mature forests, and can tolerate some shade. It is also found along fencerows and roadsides. The species prefers lighter, acidic sandy-loam soils with good drainage. Able to resprout profusely from its rootstock following fire, Eastern Flowering Dogwood shows some adaptation to forest fire. Prescribed burning shows promise as a management tool as it opens the forest canopy which results in environmental conditions less favourable to fungal disease.

The goal of this recovery strategy is to conserve and protect extant populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood, to reduce its rate of decline, and where possible, to restore populations of the species across its range in southern Ontario. The recovery objectives are to:

- Identify and protect extant populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood across its native range in southern Ontario

- Undertake monitoring of health, threats and possible resistance to dogwood anthracnose

- Develop, implement and assess management approaches for dogwood anthracnose and other threats in natural stands, and

- Where possible, restore habitat and/or populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood

It is recommended that areas where natural populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood occur be prescribed as habitat within a habitat regulation under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). The boundaries of this area should be identified as the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) ecosite type(s) surrounding Eastern Flowering Dogwood trees. For naturally growing trees in non-forest settings (e.g. roadsides and fencerows), an area extending 25 metres from the stem of each tree is recommended to be included within the habitat regulation.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Eastern Flowering Dogwood

Scientific name:Cornus florida SARO List Classification: Endangered SARO List History: Endangered (2009)

COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2007)

SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (March 18, 2009)

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5 NRANK: N2 SRANK: S2

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Eastern Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida) is a member of the Cornaceae (dogwood) family. Several subspecies or varieties have been recognized in the past, but most of these are no longer accepted (Tirmenstein 1991). Although native to the forests of eastern North America, this showy species has long been popular as an ornamental tree, and many cultivars have been developed by the horticulture industry.

Species description

Eastern Flowering Dogwood is a small tree, growing 3-10 metres, with opposite leaves, very rough bark, and mostly greenish twigs and branchlets. The large, simple, opposite leaves average 5-15 centimetres in length. The most conspicuous character is the presence of 4-6 large, showy, petal-like white bracts that surround the small clusters of flowers (Soper and Heimburger 1982). The fruit is a smooth, red, berrylike drupe about 10-12 millimetres long; these are borne in clusters of two to six. Each drupe contains one or two cream-colored, ellipsoid seeds approximately 7-9 millimetres in length. The fruits mature in August and September (Soper and Heimburger 1982). This species is slow-growing and may live up to 125 years (Strobl and Bland 2000). Detailed species descriptions, taxonomic keys, and technical illustrations can be found in Soper and Heimburger (1982), Gleason and Cronquist (1991), and Holmgren (1998).

Species biology

In Ontario, flowers of this species open between late May and early June (COSEWIC2007). Flowers are pollinated by bees, beetles, butterflies, and flies (Mayor et al. 1999). Seed set appears to be more successful when flowers are cross-pollinated (Reed 2004, cited in COSEWIC 2007). Seeds are dispersed throughout the forest litter by many species of birds, mammals, and through gravity (Rossell et al. 2001). Under natural conditions, seeds overwinter before germination occurs, and some seeds do not germinate until the second spring (Strobl and Bland 2000).

The fruits of Eastern Flowering Dogwood provide food for over 50 species of birds and many small mammals, and these animals disperse its fruits throughout the forest. Individual healthy trees can reportedly produce up to 10 kilograms of fruit in a season (Rossell et al. 2001). In parts of the United States where Eastern Flowering Dogwood can be a common species of the forest understorey, its branches provide an important food for White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) (Tirmenstein 1991).

Eastern Flowering Dogwood is also important in nutrient cycling in the eastern North American forest. Its leaves retain large amounts of calcium during the growing season, and these fall to the forest floor and decompose more rapidly than those of many other forest trees. Calcium is an especially important but mobile element in forest soils, and Eastern Flowering Dogwood keeps calcium available within the biologically active layer of the forest soil (Thomas 1969, Blair 1988 cited in Holzmueller et al. 2006). There is concern that its widespread decline across eastern North America may result in additional negative ecological effects, as forest nutrient cycles are altered. Calcium cycling in oak-hickory forests may be especially affected (Jenkins et al. 2007).

This species has adapted to fire, but is not necessarily fire-tolerant (Tirmenstein 1991). Following damage or destruction of its aboveground vegetation by fire, Eastern Flowering Dogwood may sprout profusely from the root crown. However, many plants may not survive fire. Mortality of individual plants following fire can exceed 50%. Mortality rates appear to vary with fire characteristics, including intensity, frequency, season, and site effects (Tirmenstein 1991).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Distribution

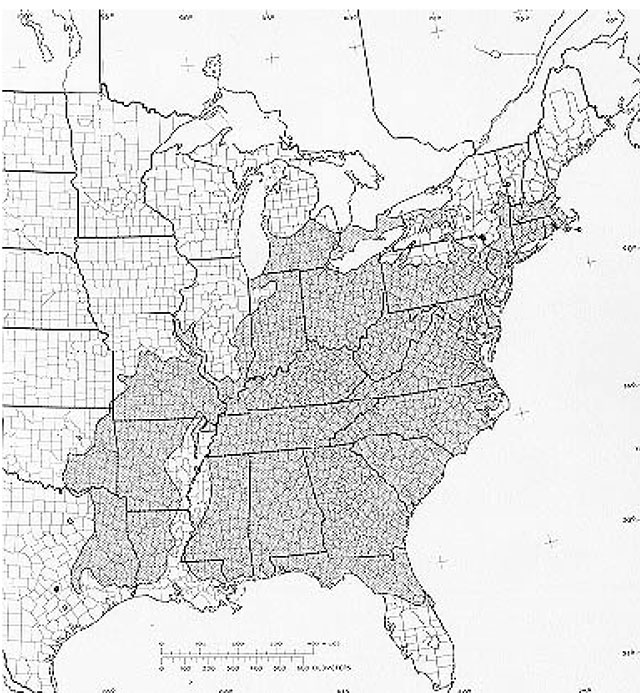

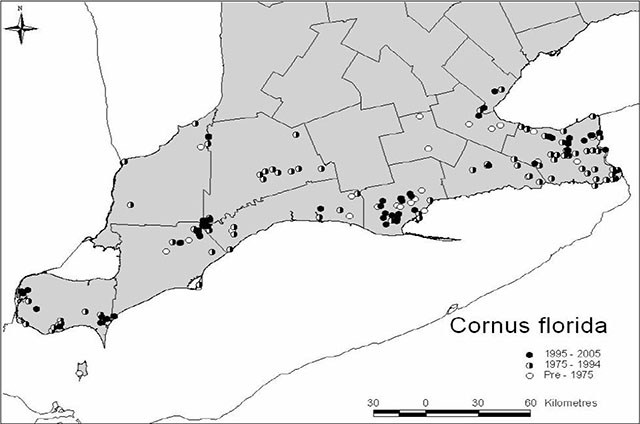

Eastern Flowering Dogwood occurs across eastern North America (Figure 1). It is common in deciduous forests and ranges widely from Michigan and southern Ontario to Maine, and south into eastern Texas and northern Florida. In Canada, the species is restricted to the Carolinian Zone of southern Ontario (Figure 2) (COSEWIC 2007).

Abundance and population trends

Recent records indicate that at least 154 populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood were recorded in Ontario between 1975 and 2005. It is not known how many of these populations are still extant, but it is estimated that there are fewer than 2000 trees occurring in scattered populations across southern Ontario (COSEWIC 2007).

A rapid decline in the health of populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood has been observed since the arrival of the dogwood anthracnose fungus in Ontario in the 1990s (Natural Resources Canada 2001). Field visits to 32 sites across the species' Ontario range has shown that mortality due to anthracnose exists at most sites where Eastern Flowering Dogwood occurs. Through analysis of data collected at Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network (EMAN) plots, it is estimated that there is a 7-8 percent annual decline of Ontario’s populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood (COSEWIC 2007) due to anthracnose. This rapid rate of decline indicates that most of the populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood in Ontario may be lost within a matter of decades (Natural Resources Canada 2001).

1.4 Habitat needs

In Ontario, Eastern Flowering Dogwood commonly grows as an understory species in open dry-mesic oak-hickory to mesic maple-beech eastern deciduous or mixed forests (COSEWIC 2007). The forests where it is found are generally mid-age to mature.

This species shares a similar range in the Ontario Carolinian forest, and may co-occur with species such as Dwarf Chinquapin Oak (Quercus prinoides), Tulip Tree (Liriodendron tulipifera), Winged Sumac (Rhus copallina), Black Oak (Quercus velutina), Pin Oak (Quercus palustris), Black Walnut (Juglans nigra), Pignut Hickory (Carya glabra), American Witch-hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), and Black Gum (Nyssa sylvatica), as well as other species at risk such as American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) and Butternut (Juglans cinerea) (COSEWIC 2007).

Eastern Flowering Dogwood can be found in open woods and forest edges within its southwestern Ontario range (S. Brinker pers. comm. 2009). It can also occur along roadsides and in fencerows (A. Woodliffe pers. comm. 2009). Eastern Flowering Dogwood occurs on soils that range from moist, deep soils to light-textured, well- drained upland soils (McLemore 1990 cited in Tirmenstein 1991). Most commonly, it occurs on coarse to medium-textured acidic soils such as sand and sandy loams, although it can occur on clay loam soils (COSEWIC 2007). Abundance appears to increase with better drainage and lighter soil textures, and the species is not usually found in areas that are periodically flooded, or on poorly drained soils (COSEWIC 2007). Soil pH generally ranges from 6 to 7 (Fowells 1965 cited in Tirmenstein 1991).

1.5 Threats to survival and recovery

Dogwood Anthracnose

The primary threat to the species, and the reason for its precipitous population decline in eastern North America, is the dogwood anthracnose fungus (Natural Resources Canada 2001). The origin of the disease is unknown, but many believe that it was introduced to North America (Holzmueller et al. 2006). The disease kills Eastern Flowering Dogwood plants of all sizes, and has particularly severe effects on seedlings, small trees, and on trees in the forest understorey (Natural Resources Canada 2001, Holzmueller et al. 2006). Infection has not been reported on other dogwood species native to Ontario (Natural Resources Canada 2001). Infected Eastern Flowering Dogwood populations show a high degree of mortality, typically 25-75 percent, although mortality of up to 95 percent has been reported in Illinois (Schwegman et al. 1998 cited in COSEWIC 2007).

Dogwood anthracnose appears to spread during cool, wet seasons (Natural Resources Canada 2001). Tan-coloured spots appear on the lower leaves of the tree, and develop into leaf holes and necrotic leaf tissue, resulting in early leaf drop. Infection spreads up the crown, as shoots and twigs become infected and cankers develop. Trees may respond with epicormic branching on the trunk and main branches. Cankers may girdle the tree and open the cambium to further infection; eventually, the entire tree dies (Natural Resources Canada 2001). Spores are locally dispersed by rain; insects and birds probably assist long-distance spore dispersal (Holzmueller et al. 2006).

The severity of dogwood anthracnose infection is related to levels of light and moisture in the forest understorey. Infection is often more severe in shaded settings and on north-facing slopes than in areas with an exposed aspect or open canopy. Sunlight and improved air circulation probably reduce the spread and severity of the disease (Chellemi and Britton 1992, Daughtrey et al. 1996).

The use of prescribed burning shows promise as a management technique to control the dogwood anthracnose fungus (Discula destructiva). In a US study (Holzmueller et al. 2008) examining forest fire history and the impact of the anthracnose fungus, sites that were burned over a 20-year period had higher stem densities of Eastern Flowering Dogwood, and smaller trees in burned areas also showed reduced crown dieback. It is believed that fire lessens the impacts of dogwood anthracnose by opening up the forest to provide drier conditions unsuitable for fungal growth (Holzmueller et al. 2008).

Forest succession

There is evidence that fire suppression has shifted forest canopy composition throughout the midwestern United States from oak-hickory to sugar maple, and has also resulted in increased shading of Eastern Flowering Dogwood. This may have accelerated its decline due to the anthracnose fungus (Pierce et al. 2008). McEwan et al.(2000) attributed 36 percent of the decline of Eastern Flowering Dogwood in an old growth forest to canopy closure and environmental stresses such as drought. Thus, forest succession may play a role in the decline of Eastern Flowering Dogwood even in stands where anthracnose is not present, and such sites may benefit from management to maintain healthy, stable populations (Pierce et al. 2008).

Herbivory by deer

In the eastern United States where it is a common species of the forest understorey, Eastern Flowering Dogwood twigs provide important browse for White-tailed Deer (Tirmenstein 1991, Rossell et al. 2001). With high densities of White-tailed Deer across southern Ontario, it is likely that herbivory is a threat to some dogwood populations.

Habitat loss and fragmentation

Habitat loss throughout the Carolinian Zone has affected Eastern Flowering Dogwood, especially in southwestern Ontario. Fragmentation and loss of forested land in southern Ontario, particularly in Essex County and in the Chatham–Kent region, reduce the probability that fauna can effectively disperse seeds over long distances from occupied habitats to suitable unoccupied habitats. It is also speculated that habitat loss and fragmentation restrict gene flow and thus could reduce the opportunity for plants to adapt a natural resistance to the anthracnose fungus (COSEWIC 2007).

Insects and pests

Eastern Flowering Dogwood is susceptible to many insects, although these are of much less concern than the anthracnose fungus. Identified pests include the dogwood borer (Synanthedon scitula), flat-headed borers (Chrysobothris azurea and Agrilus cephalicus), dogwood twig borer (Oberea tripunctata), twig girdler (Oncideres cingulata), scurfy scale (Chionaspis lintneri) and dogwood scale (and Chionaspis corni) (McLemore 1990 cited in Tirmenstein 1991). Root knot nematode and defoliators can also reduce survival rates (COSEWIC 2007).

1.6 Knowledge gaps

There is a significant body of research on dogwood anthracnose from the eastern United States, where it was first observed in the late 1970s (Daughtrey et al. 1996). Although research originally addressed the management of horticultural trees and development of resistant cultivars, an increasing focus has been placed on identifying the ecological impacts and developing management recommendations for dogwoods in forested settings (e.g. Holzmueller et al. 2006, Jenkins et al. 2007, Pierce et al. 2008). In general, more research is needed on reducing the severity of the disease in forest settings, and on refining the specific habitat requirements of Eastern Flowering Dogwood in Ontario.

Presence of resistant individuals and/or populations in Ontario

A partial survey of Eastern Flowering Dogwood populations in Ontario was conducted during the development of the COSEWIC status report, in which some populations were identified that are not currently exhibiting signs of decline due to anthracnose (COSEWIC 2007). Ongoing monitoring at selected sites would determine whether any of these populations are resistant over the long term. An evaluation of site conditions would help to determine which natural characteristics (stand composition, structure, etc.) may be contributing to lower levels of mortality.

Management tools for use in Ontario

Monitoring of factors such as mortality, stem density and infection rate of Eastern Flowering Dogwood in burned areas would help to determine whether prescribed burning can be used to slow the decline of Eastern Flowering Dogwood. Prescribed burning has been undertaken in some natural areas where Eastern Flowering Dogwood is present (e.g. St. Williams' Forest, Turkey Point), and monitoring regeneration and disease severity at these sites would provide useful information.

Applied research to determine the success of stand thinning in reducing mortality and promoting regeneration would also be helpful. In studies of previously harvested plots, Britton and Pepper (1994) found that partial thinning may be detrimental to Eastern Flowering Dogwood over the long term. At the Spooky Hollow Nature Sanctuary in Norfolk County, pine plantations on sandy soils have been removed, and Eastern Flowering Dogwood has seeded profusely into the new openings (M. Gartshore pers. comm. 2009).

Research would help to determine whether such manual care of trees is effective or feasible in Ontario. For example, removal of diseased twigs and leaves and application of fungicide have been used successfully to slow the spread of dogwood anthracnose in the United States (Daughtrey et al. 1996). It is possible that these techniques can be modified to provide limited control methods under natural site conditions in Ontario.

Identification of habitat needs in Ontario

A more thorough description of Eastern Flowering Dogwood habitats across the range of Ontario sites using Ecological Land Classification approach wherever possible (Lee et al. 1998) will ensure that the habitat regulation developed for Eastern Flowering Dogwood is both accurate and sufficient to provide protection for existing habitat and recovery habitat for Eastern Flowering Dogwood.

1.7 Recovery actions completed or underway

In Ontario, a few recovery actions are underway. LandCare Niagara, in partnership with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) in Vineland, has conducted inventory and occurrence updates in Haldimand and Niagara regions. The group also developed educational materials aimed at landowners and the general public, to assist landowners in identifying Eastern Flowering Dogwood and the threats facing it.

Monitoring of Eastern Flowering Dogwood has been undertaken at two locations in southwestern Ontario. Two EMAN tree plots in Norfolk County (Backus Woods and Wilson Tract) were first inventoried in 1995 and in subsequent years (2000, 2003, 2005) following the arrival of the anthracnose fungus, to derive an estimate of population decline (COSEWIC 2007).

Prescribed burning is occurring in various blocks at Turkey Point Provincial Park for savannah restoration, which may allow for an assessment of the response to assess the response of Eastern Flowering Dogwood and anthracnose fungus to fire. Monitoring of known trees at these sites is underway (S. Dobbyn pers. comm. 2010).

Eastern Flowering Dogwood seeds were collected by Mary Gartshore from two Norfolk County sites in the mid-late 1990s. The seeds were propagated in a greenhouse and seedlings were planted in the same area. Growing in open conditions and sandy soil, these trees remain in good health and produced large seed crops in 2006 and 2008 (M. Gartshore pers. comm. 2009).

Eastern Flowering Dogwood was also represented in a Gene Bank project at the University of Guelph Arboretum in the 1980s. Focused on a variety of Carolinian species, the Gene Bank was intended to provide surplus populations and open or controlled pollinated seed sources, and to take the seed collecting pressure off natural stands of native species. Losses of some Eastern Flowering Dogwood specimens have occurred due to dogwood anthracnose, climate, and other diseases, but several healthy trees remain at the arboretum (S. Fox pers. comm. 2009).

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The goal of this recovery strategy is to conserve and protect extant populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood, to reduce its rate of decline, and where possible, to restore populations of the species across its range in southern Ontario.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1.0 | Identify and protect extant populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood across its native range in southern Ontario |

| 2.0 | Undertake monitoring of health, threats and possible resistance to dogwood anthracnose |

| 3.0 | Develop, implement and assess management approaches for dogwood anthracnose and other threats in natural stands |

| 4.0 | Where possible, restore habitat and/or populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood |

Restoration is considered an important objective, but it is acknowledged that it may not be successful unless management techniques are in place to control the anthracnose fungus and reduce mortality of Eastern Flowering Dogwood. Related restoration approaches have been accorded a later priority in Table 2.

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery for Eastern Flowering Dogwood in Ontario

1.0 Identify and protect extant populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood across its native range in southern Ontario

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Communications | 1.1 Through a recovery team:

|

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Communications | 1.2 Encourage collaboration among agencies including the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR), Environment Canada (EC), Parks Canada, and the scientific community to develop and implement habitat protection for the species |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research | 1.3 Describe and identify typical vegetation communities in which Eastern Flowering Dogwood occurs across its southern Ontario range in order to inform habitat regulation |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Communications | 1.4 Develop educational materials for landowners and land stewards to aid in the identification of Eastern Flowering Dogwood and the dogwood anthracnose fungus |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Protection | 1.5 Secure habitat on private lands across a representative range of the species through public ownership, especially at larger sites where trees exhibit resistance to dogwood anthracnose (if such sites are found) |

|

2.0 Undertake monitoring of health, threats and possible resistance to dogwood anthracnose

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Long-term | Monitoring and Assessment Research | 2.1 Undertake monitoring of known populations:

|

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Inventory and Monitoring | 2.2 Inventory and continue to document new stands of Eastern Flowering Dogwood including information on their health status; record in Ontario NHIC database |

|

3.0 Develop, implement and assess management approaches for dogwood anthracnose and other threats in natural stands

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Management | 3.1 Undertake prescribed burning at selected locations where Eastern Flowering Dogwood is present (e.g. St. Williams Forest, Turkey Point); assess its success as a management technique

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Management Research | 3.2 Use current research to identify whether any mechanical, chemical, or biological methods of anthracnose control used by the horticultural industry are effective and/or feasible for use in natural forest settings

|

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Management Communication | 3.3 Develop and distribute best management practices for Eastern Flowering Dogwood stands (e.g. methods to slow the spread of dogwood anthracnose, habitat restoration opportunities) for use by land owners and stewards |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management | 3.4 If necessary, control deer population at sites with significant and/or resistant Eastern Flowering Dogwood populations |

|

4.0 Where possible, restore habitat and/or populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood footnote 1

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Communications Stewardship | 4.1 Cooperate with other initiatives to connect and expand forest fragments to increase potential suitable habitat (e.g. Carolinian Canada) |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management | 4.2 Consider management (i.e. removal of conifers) in former conifer plantations within the range of Eastern Flowering Dogwood, in order to promote natural seeding, growth and dispersal of Eastern Flowering Dogwood as well as other native species |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Restoration | 4.3 Coordinate seed collection across the species' range in order to ensure that locally adapted seeds are available for restoration plantings |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Restoration | 4.4 Consider re-establishing Eastern Flowering Dogwood in suitable habitat at previously documented locations (e.g. pre-1975 sites) using local, potentially resistant seeds, and managing habitat to maintain open conditions and limit the spread and infection of dogwood anthracnose |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research | 4.5 Develop a source(s) of seeds and/or seedlings for restoration plantings that are potentially resistant to dogwood anthracnose, and define the maximum distance from the source that seeds may be planted |

|

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA 2007, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the recovery team will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

It is recommended that areas where natural populations of Eastern Flowering Dogwood occur be prescribed as habitat within a habitat regulation. The areas surrounding Eastern Flowering Dogwood trees that are believed to be horticultural specimens (i.e. those clearly planted in landscaped settings such as urban gardens) should not be included in a habitat regulation because these are usually non-native cultivars of Eastern Flowering Dogwood that did not originate in Ontario. However, the areas surrounding trees in restoration plantings or trees of indeterminate origin are recommended for inclusion in a habitat regulation, to help contribute to the recovery of the species.

It is recommended that the habitat regulation include the contiguous ELC ecosite polygon (Lee et al. 1998) within which the species is found. If trees are close to the polygon edge, a minimum distance of 25 metres from the stem of any Eastern Flowering Dogwood tree is recommended for regulation. Regulating habitat based on the vegetation community will help to preserve the ecological function of the area, will help to maintain the ecological conditions required for the persistence of Eastern Flowering Dogwood, and may facilitate dispersal of seeds and species recruitment over a broad area. Protecting a minimum area of 25 metres around each tree represents a precautionary approach to ensure the necessary habitat conditions directly surrounding the tree are maintained and that individual trees are protected from harm.

Because of the wide range of habitats in which Eastern Flowering Dogwood occurs across southern Ontario and the number of ecosites in which it occurs, specific ecosite types are not listed here. Assessment of habitat types across the species' range has been recommended as a recovery approach, which would further inform the development of a habitat regulation.

Where the habitat of naturally growing trees cannot be meaningfully described by an ELC ecosite polygon (e.g. along fencerows and roadsides), a minimum area of 25 metres from the stem of the tree is recommended to be prescribed as habitat within a habitat regulation.

If future scientific studies indicate that additional areas of habitat are necessary to achieve the recovery goals for this species, that information should also be considered in developing the habitat regulation.

Glossary

Bract: A leaf, usually much reduced or modified, which subtends a flower on inflorescences in its axis (Allaby 1992).

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secur

Drupe: A fleshy fruit, such as a plum, containing one or a few seeds, each enclosed in a stony layer that is part of the fruit wall (Allaby 1992).

Ecological Monitoring and Assessment Network (EMAN): This national network has developed a series of standard monitoring protocols, including several plot-based protocols to monitor terrestrial vegetation.

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Epicormic bud: Epicormic buds lie dormant beneath the bark, their growth suppressed by hormones from active shoots higher up the plant. Under certain conditions they develop into active shoots, such as when damage occurs to higher parts of the plant, or light levels are increased following removal of nearby plants.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Allaby, M. (ed.) 1992. The Oxford Concise Dictionary of Botany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 442 pp.

Blair, J.M. 1988. Nutrient release from decomposing foliar litter of three tree species with special reference to calcium, magnesium, and potassium dynamics. Plant and Soil 110: 49–55.

Chellemi, D.O., and K.O. Britton. 1992. Influence of canopy microclimate on incidence and severity of dogwood anthracnose. Canadian Journal of Botany 70: 1093-1096.

COSEWIC 2007. COSEWIC Assessment and status report on the eastern flowering dogwood Cornus florida in Canada. Committee of the Status of Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi+ 22 pp.

Daughtrey, M.L., C.R. Hibben, K.O. Britton, M.T. Windham, and S.C. Redlin. 1996.

Dogwood Anthracnose: understanding a disease new to North America. Plant Disease. 80: 349-358.

Dobbyn, S. 2010. Zone Ecologist, Southwest Zone, Ontario Parks, OMNR. Personal communication.

Fowells, H. A., compiler. 1965. Silvics of forest trees of the United States. Agricultural Handbook 271. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. 762 pp.

Fox, S. 2009. Assistant Arboretum Manager, University of Guelph. Personal communication.

Gartshore, M. 2009. Pterophylla Native Plants and Seeds, R.R.#1, Walsingham, ON. Personal communication.

Gleason, H.A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden. 910 pp.

Holmgren, Noel. 1998. The Illustrated Companion to Gleason and Cronquist’s Manual. Illustrations of the Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York.

Holzmueller, E.J., S. Jose, M. Jenkins, A. Camp, and A. Long. 2006. Dogwood anthracnose in eastern hardwood forests: what is known and what can be done? Journal of Forestry. 104: 21-26.

Holzmueller, E.J., S. Jose, and M.A. Jenkins. 2008. The relationship between fire history and an exotic fungal disease in a deciduous forest. Oecologia. 155: 347-356.

Jenkins, M.A., S. Jose and P.S. White. 2007. Impacts of an exotic disease and vegetation change on foliar calcium cycling in Appalachian forests. Ecological Applications. 17: 869-881

Lee, H., W. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, & S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximations and Its Application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

Mayor, A.J., J.F. Grant, M.T. Windham, and R.N. Trigano. 1999. Insect visitors to Flowering Dogwood, Cornus florida L. in Eastern Tennessee: Potential pollinators. Proceedings of Southern Nurserymen’s Association Research Conference. 44: 192-196.

McEwan R.W., R.N. Muller, M.A. Arthur, and H.H. Housman. 2000. Temporal and ecological patterns of Flowering Dogwood mortality in the mixed mesophytic forest of eastern Kentucky. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127: 221–229.

McLemore, B. F. 1990. Cornus florida L. Flowering Dogwood. Pp 278-283 In Burns, R.M. and B.H. Honkala. Silvics of North America. Vol. 2. Hardwoods. Agric. Handb. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service.

Natural Resources Canada. 2001. Dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva) in Ontario. Frontline Express, Bulletin No. 1, Canadian Forestry Service, Great Lakes Forestry Centre, Sault Ste. Marie, ON.

Pierce, A.R., W.R. Bromer, and K.N. Rabenold. 2008. Decline of Cornus florida and forest succession in a Quercus-Carya forest. Plant Ecology 195: 45-53.

Reed, S.M. 2004. Self-incompatibility in Cornus florida. Horticultural Science 39: 335- 338.

Rossell, I.M., C.R. Rossell, Jr., and K.J. Hining. 2001. Impacts of dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva) on the fruits of Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida L.): implications for wildlife. American Midland Naturalist 146: 379-387.

Schwegman, J.E., W.E. McLean, T.L. Esker and J.E. Ebinger. 1998. Anthracnose- caused mortality of Flowering Dogwood (Cornus florida) at the Dean Hills Nature Preserve, Fayette County, Illinois, USA. Natural Areas Journal 18:3.

Soper, James H. and Margaret L. Heimburger. 1982. Shrubs of Ontario. Life SciencesMisc. Publ. Toronto, ON: Royal Ontario Museum. 495 pp.

Strobl, S. and D. Bland. 2000. A silvicultural guide to managing southern Ontario forests. Version 1.1. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 648 pp.

Thomas, W.A. 1969. Accumulation and cycling of calcium by dogwood trees. Ecological Monographs 39: 101–120.

Tirmenstein, D. A. 1991. Cornus florida. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online].

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Accessed September 4, 2009.

Woodliffe, A. 2009. District Ecologist, Aylmer District OMNR. Personal communication.

Recovery strategy development team members

| Name | Affiliation and location |

|---|---|

| Anita Imrie | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR), Species at Risk Branch |

| Melinda Thompson-Black | OMNR, Aurora District |

| Barb Boysen | OMNR, Forest Gene Conservation Association |

| Karine Beriault | OMNR, Guelph District |

| Amy Brant | OMNR, Guelph District |

| Allan Woodliffe | OMNR, Aylmer District |

| Sandy Dobbyn | OMNR, Ontario Parks (Southwest Zone) |

| Sean Fox | University of Guelph |

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Because dogwood anthracnose particularly affects seeding and small trees and seedlings, restoration plantings are not likely to be successful unless they occur at sites where anthracnose is absent, and/or other management is ongoing to prevent closure of the forest canopy.