Euthanasia of horses

Learn about best practices for euthanasia in horses, including when they should be considered, appropriate methods and proper deadstock disposal.

Introduction

Some horses die of natural causes, but others need to be euthanized. The word “euthanasia” is derived from “eu” (meaning good), and “thanatos” (meaning death). A good death would be one that occurs with minimal pain and at an appropriate time in the horse's life to prevent pain and suffering

Euthanasia can take place to prevent suffering caused by:

- a medical condition

- an injury, such as a fractured leg

- disease, such as severe heaves or incurable colic

- age-related conditions affecting quality of life

Appropriate circumstances for euthanasia

The American Association of Equine Practitioners provides some criteria for the appropriate time for euthanasia

- the horse's condition is chronic, incurable and resulting in unnecessary pain and suffering. Some conditions, such as chronic laminitis with the pedal (coffin) bone protruding through the sole, are easier to assess than others. There is often no doubt as to the pain and suffering and the need for humane euthanasia to relieve current and future suffering.

- the horse's condition presents a hopeless prognosis for life. Foals born with severely deformed limbs often have a hopeless prognosis for quality of life.

- the horse is a hazard to itself, other horses or humans. Some horses can handle being blind and can get along within their own personal space but, in a herd situation, they may be savaged or injured by other horses or run into a fence or other physical hazard.

- the horse constantly and in the foreseeable future is unable to:

- move unassisted

- interact with other horses

- exhibit behaviours that may be considered essential for a decent quality of life

- the horse will require continuous medication for the relief of pain and suffering for the rest of its life.

Before reaching a final decision, consult with your veterinarian and your insurance agent. Many companies providing insurance coverage for a horse will require notification and perhaps a second opinion before honouring a policy.

Alternatives to euthanasia

When the American Association of Equine Practitioners’ criteria are not met, there may be other reasonable options to consider. By changing the way the horse is managed, it may be possible to improve the horse's quality of life.

Moving a horse with severe equine asthma to a place that has 24-hour-a-day, 7-day-a-week outdoor housing can drastically improve its condition.

Well-mannered horses, which are lame with mild navicular disease, may not be able to campaign in shows. However, they may be suitable as lead horses in a riding-for-the-disabled program if their condition can be controlled with medication and/or farrier care.

Talk to your veterinarian about the possibility of these opportunities in your area.

Location for euthanasia

Horses should be euthanized in a location that is free from obstacles, provides enough room for a falling horse and be easily accessible for removal and disposal of the body. Avoid unnecessary pain or suffering when moving injured animals.

Euthanasia methods

Before the need for euthanasia arises, speak with your veterinarian to determine the most appropriate method.

Lethal injection

For a lethal injection, a veterinarian will often administer an overdose of a barbiturate. Before lethal injection, many veterinarians will sedate the horse, while others may lay the horse down using general anesthesia. This method of euthanasia is fast, pain-free and usually less emotionally traumatic to the owner than other methods. However, the euthanized horse will contain significant levels of barbiturate, so the carcass must not be scavenged prior to disposal. It is your responsibility to ensure that birds, coyotes and dogs do not eat from a contaminated carcass. There is sufficient barbiturate in a euthanized horse to be a danger to a scavenger's health.

Lethal injection may not be feasible in some areas since a veterinarian may not always be available for an emergency euthanasia. When scheduling a veterinary-assisted euthanasia, ensure that you schedule your veterinarian as well as a backhoe operator (or other means of disposal) on the same day.

Other acceptable chemical methods of euthanasia

Due to the environmental concerns of phenobarbital and the occasional lack of availability of pentobarbital, veterinarians may prefer to euthanize using other methods.

T-61

T-61 is an injectable product that contains 3 different drugs capable of respiratory depression and paralysis. It must be given by trained personnel and only by intravenous injection. Since this drug can cause unpleasant reactions or behaviour in some animals, it is highly recommended that the horse be placed under general anesthesia before administration.

Intrathecal lidocaine

After the horse has been anesthetized and is laying on the ground on its side, the veterinarian will administer 2% lidocaine hydrochloride into the subarachnoid space, which is located between the brain and the surrounding membrane. This is done by placing a spinal needle in a specific space between vertebrae behind the poll. When in the correct place, clear cerebrospinal fluid will exit the needle or be removed manually using a syringe, and the veterinarian will quickly administer the lidocaine.

Intravenous potassium chloride or magnesium sulfate

Saturated solutions of potassium chloride or magnesium sulfate may be administered intravenously by the veterinarian after the horse is in a deep plane of anesthesia and laying on the ground on its side.

Gunshot

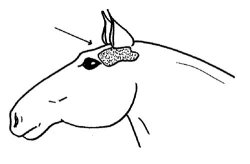

The use of a firearm is an efficient method of euthanizing a horse when administered by an experienced person. The weapon should be fired with the muzzle close to the head (but not against the skull) at the correct location and in the required direction to ensure that the shot penetrates the brain and does significant damage

A number of calibers can be used, including:

- a rifled slug fired by a shotgun (410 gauge or larger)

- rifles (including .308 and .223), when placed 1-2 in. from the skull

The smaller caliber .38 police service revolver or .22 calibre long rifle may render the horse unconscious but may not be lethal and may require exsanguination (bleeding out) subsequent to shooting.

While being fast and readily available in most rural communities, aesthetically, the use of a firearm may be unpleasant to the owner. In addition, the release of a projectile(s) by a rifle or shotgun poses a potential danger to animals and humans in the vicinity.

Captive bolt

A captive bolt pistol discharges a blank rifle cartridge (no bullet). It drives a piston-like bolt forward. When placed on the skull of an animal, the bolt is projected forward and delivers a lethal blow to the brain. The location on the skull and angle of the bolt is the same as recommended for euthanasia by a firearm.

A captive bolt pistol should only be used by an experienced operator. The horse must be appropriately restrained to prevent movement of the head. It does have the advantage that no permits or licences are required and it can be legally transported in a vehicle. For safety reasons, the captive bolt should only be used in a location, such as a knocking box, that provides protection from a horse falling on the operator.

Donation to a teaching facility

In areas where veterinary schools are nearby, horses can be donated to the teaching facility. Horses will be examined and humanely treated while in the care of the teaching hospitals. Subsequently, they will be euthanized using the veterinarian’s preferred method.

Disposal options

Confirm that the horse is dead within 1 minute of euthanasia and again at 5 minutes or more. This can be achieved by monitoring the heart rate and, subsequently, the corneal reflex. The pupils of the eyes should be dilated. A blinking response to touching the cornea of the eye indicates brain activity and will necessitate the application of an alternate euthanasia method.

In Ontario, on-farm management and disposal of deadstock is covered under the Nutrient Management Act (NMA). Owners are required to properly dispose of mortalities in a safe, environmentally friendly manner within 48 hours of death. When euthanizing an animal, choose a location where you can easily access the euthanized animal with heavy equipment to make disposal easier.

Scavenging must be prevented at all times. If mortalities are not disposed of or stored properly, wild animals, dogs or birds could exhume them and spread diseases. Partially decayed mortalities are odorous, unsightly and are breeding spot for flies.

O. Reg. 106/09: Disposal of Dead Farm Animals under the NMA establishes requirements to minimize negative impacts to the environment from on-farm disposal.

Owners may also take deadstock to:

- waste disposal sites approved under the Environmental Protection Act, such as a landfill. Not all landfills will except deadstock, so call ahead to confirm.

- disposal facilities licensed under the Food Safety and Quality Act, such as a renderer

- a licensed veterinarian for post-mortem and subsequent disposal

Burial

The standards for deadstock burial pits were established to protect ground and surface water and prevent scavenging. The deadstock located in a burial pit must have at least 0.6 m of soil cover at all times. These sites must be monitored regularly for 1 year for any signs of depression in the soil surface. Depressions may result in the collection of water in the pit, slowing decomposition and increasing the risk of runoff.

Burial pits may receive up to 2500 kg of deadstock weight per pit. This may pose challenges for producers that, unfortunately, have multiple mortalities at the farm. Multiple burial pits may be established on the same property, provided there is adequate separation distance of at least 60 m between them to reduce the risk of groundwater contamination through leaching.

The regulation also specifies setback distances for burial pits from wells, subsurface tile drainage and neighbouring properties.

Areas of the province where bedrock or groundwater is close to the surface are unsuitable. Burial of mortalities in areas susceptible to groundwater contamination could result in adverse effects in nearby wells. The potential for groundwater contamination and subsequent well-water contamination is a function of the soil type, bedrock depth, and groundwater depth. Coarse soils (sands and gravel) may increase groundwater contamination risks because they allow rapid movement of liquids away from the burial site with minimal filtration or treatment. Shallow bedrock is a concern since open fractures in bedrock permit rapid movement of contaminated water with minimal filtration or treatment.

Winter conditions with frozen soils can make burial difficult.

Composting

On-farm composting of a carcass is readily available but not aesthetically acceptable to everyone. However, it does offer an option for immediate disposal of livestock mortalities of all sizes, as well as afterbirths, which can be done year-round.

On-farm composting can provide an excellent source of organic matter and nutrients to farms. If done properly, composting will kill pathogens and stabilize the organic and nutrient content of the finished compost. If done improperly, composting may result in odours, scavenging and potential environmental impacts.

The availability and price of substrate for carcasses to be placed in may impact the choice to compost deadstock. Only use:

- sawdust, shavings or chips from clean, uncontaminated, untreated wood

- straw from grain, corn or beans

- livestock bedding with at least 30% dry matter and containing only allowable composting materials

- hay or silage

- poultry litter

A 300-mm base of substrate is laid on the ground. The carcass is then placed and covered with at least 600 mm of substrate. Mixture should be 75% substrate to 25% carcass on a volume basis.

The volume and size of the deadstock to be composted will impact the location and construction of the compost pile. The regulation specifies site setbacks to sensitive features like neighbours, wells and subsurface drainage tiles.

The larger the deadstock, the longer it will take to compost fully. A 1000-lb horse carcass may require 6 months or more to fully break down. The pile will need to be turned/disturbed with a front-end loader tractor during the process at regular intervals (every 2 months) to re-blend the material and introduce oxygen into the pile as composting is an aerobic process.

Composting is considered complete when there is no:

- remaining soft animal tissue

- bone fragments larger than 15 cm

- other animal matter larger than 25 mm

- offensive odours

Incineration

While the on-farm incineration of horses is permitted in Ontario, the cost of an incinerator unit capable of receiving a horse is not justifiable for occasional deadstock disposal.

Disposal vessels

Disposal vessels were developed in response to predation problems on sheep farms. They are an inexpensive and non-labour intensive method of disposing of smaller-sized deadstock, placentas and aborted fetuses, but may not be a practical method for dealing with much larger horse carcasses.

Collection

Deadstock may be picked up on the farm by a licensed collector or the owner can deliver the carcass to the collector.

Deadstock awaiting pick-up must be stored so that it is concealed from public view, and any liquids from the animal must be prevented from escaping onto the ground. Improper storage of deadstock result in complaints from the public and it may attract scavengers and predators, posing biosecurity problems for the farm.

There are areas of the province where no collection service is offered, and there are some species of livestock that are not picked up. The costs of collection should be compared to the operational and management costs of disposal on-farm.

When an owner transports their own deadstock, the deadstock must be kept out of public view at all times. The vehicle or container must be constructed to prevent the spillage of liquids and materials that may be cleaned and disinfected after transport.

Dragging into the bush

Dragging a dead animal into the bush and leaving it to be scavenged is illegal in Ontario.

Euthanasia plan

Many of the difficult decisions associated with the euthanasia of a horse can be made prior to the event. The development of a euthanasia plan with your veterinarian will ensure your wishes will be honoured in the event you or your veterinarian are absent in the case of an emergency.

Euthanasia plans outline the preferred method to be used, alternate methods, options for carcass disposal and contact information for veterinarians. The euthanasia plan should be dated and posted in a central place in the stable. All employees should be aware of the plan.

Dealing with the death of a horse

Grieving the death of a horse is normal, and may cause you to feel:

- sad

- angry

- guilty

- alone

Expressing your emotions is part of the healing process. The Ontario Veterinary College Pet Trust provides resources to assist you in managing your loss you feel.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) Euthanasia Guidelines 2021

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Equines, National Farm Animal Care Council