Far North Land Use Strategy: Discussion paper

This discussion paper initiates a topic-by-topic discussion of how the Far North Land Use Strategy will guide planning teams as they prepare individual community-based land use plans.

Foreword

The Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) is moving forward to prepare a Far North Land Use Strategy. The Strategy will guide community based land use planning in the Far North of Ontario. This discussion paper suggests planning-related topics and guidance that could be included in the Strategy. It builds on a foundational document, An Introduction to the Far North Land Use Strategy

, that was posted on the Environmental Registry in December 2013. The ministry is seeking input on the ideas presented in this discussion paper. Working with First Nations in the Far North and engaging stakeholders and the public, the ministry will consider the comments on this discussion paper in preparing a Draft Far North Land Use Strategy for further discussion. The Strategy will provide guidance on how to apply existing policy and legislation in a land use planning context in the Far North. It will consider economic, environmental and social interests. Once the Strategy is in place, it will be taken into account as community based land use plans are developed, approved and amended.

Part A: introduction

Ontario is working jointly with First Nations to prepare community based land use plans as part of the Far North Land Use Planning Initiative. The Far North Act, 2010 (the Act) is the legislative foundation for planning at the community level in the Far North of Ontario and for a Far North Land Use Strategy (Strategy) to help guide that planning.

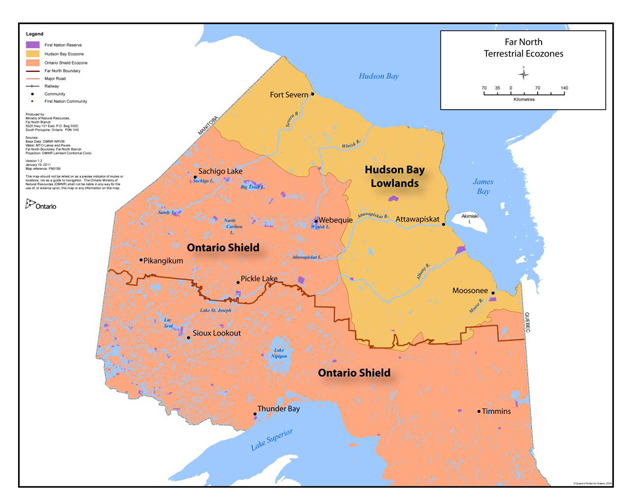

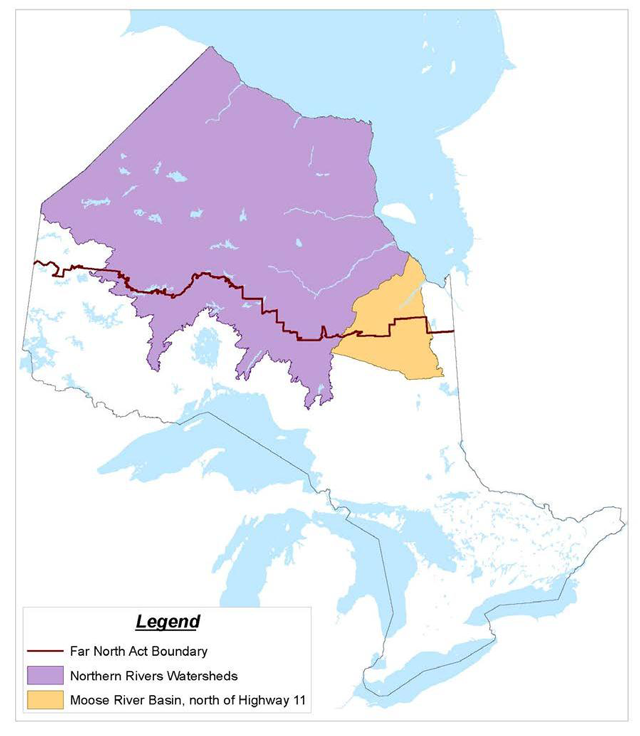

The Far North Act, 2010 applies to public lands in the area shown in the map below. The Act does not direct planning on First Nation reserve lands and other federal lands, nor does it apply to municipal lands or parcels of private land.

Community based land use planning with each First Nation establishes which areas will be set aside for long-term protection and which areas will be open for sustainable economic development, while emphasizing the importance of continuing to care for all of the land and water. The Far North Land Use Strategy will assist joint planning teams in the preparation of land use plans and guide the integration of matters that are beyond the scope of individual planning areas.

Ontario began the preparation of the Strategy by posting An Introduction to the Far North Land Use Strategy

(Introduction) on the Environmental Registry in December 2013. The Introduction provided an overview of the Strategy’s contents and a description of how it will guide and support planning. The Introduction and Environmental Registry notice are available on the Environmental Registry; enter EBR Registry Number 012-0598.

This discussion paper is the second stage of preparing the Strategy. Through this paper, Ontario is seeking input from First Nations, stakeholders and the public, on the proposed land use planning topics and potential guidance on those topics that could be included in the Strategy. All input received will be considered in drafting the Strategy.

Further opportunities for discussion and engagement will be provided on the Draft Strategy.

Figure 2: stages in the development of the Far North Land Use Strategy

[Figure 2 converted to text for accessibility]

Process to develop the strategy

Stage 1: An introduction to the Far North Land Use Strategy

- Completed

- Provided an overview of the Strategy’s contents and how it will guide/support planning

- Posted on environment registry December 2013

Stage 2: Discussion paper

- Current stage.

- Includes a discussion of proposed land use planning topics and potential duidance to be included in the strategy

- Being posted on the Environmental Registry for 60 day comment period

Stage 3: Draft strategy

- Anticipated Spring 2015

- Draft Far North Land Use Strategy.

- Will be posted to the Envrionmental Registry for comment.

Stage 4: Final Far North Land Use Strategy

- Anticipated Fall 2015

- Strategy must be taken into account as community based land use plans are developed, prepared and amended.

Background

Far North context

The Far North represents 42 per cent of the province, spanning the width of Northern Ontario, from Manitoba in the west, to James Bay and Quebec in the east. It encompasses two distinct ecological regions: to the east are the bogs and fens of the Hudson Bay Lowlands; to the west and south is the boreal forest of the Canadian Shield. Neighbouring provinces and territories include Manitoba to the west, Quebec to the east and Nunavut to the north.

Enlarge Figure 3 Map of Northern Ontario (PDF)

Lakes, rivers and wetlands cover almost half of the surface area of the Far North

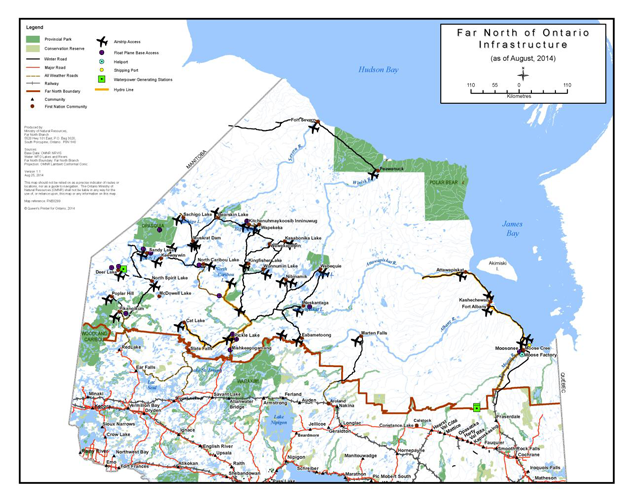

The Far North is home to 24,000 people living in 34 communities, 31 of which are First Nation communities. The two municipalities in the Far North are Moosonee and Pickle Lake while Moose Factory has a Local Services Board established under the Northern Services Board Act. Living mainly in remote communities, First Nation people make up more than 90 per cent of the region’s population. Traditional languages spoken include Ojibway, Cree and Oji-Cree. Many First Nation people in the Far North live close to the land; they know and rely on it. Many continue to pursue traditional activities, such as hunting, fishing and trapping.

While there is currently limited development in the Far North, there is vast natural resource potential. There are two operating mines in the Far North (Victor Mine operated by De Beers and Musselwhite Mine operated by Goldcorp), and ongoing mineral exploration indicates significant mineral potential particularly in the area known as the Ring of Fire. Forestry, renewable energy and tourism may also provide economic opportunities. Pressures for development also include all-weather roads, electricity transmission, broadband telecommunications and other infrastructure. It is important to guide and plan for this development.

The majority of the communities in the Far North rely on generators powered by diesel fuel for electricity. Expansion of transmission lines is being considered to reduce communities’ reliance on diesel fuel.

Road infrastructure in the Far North is limited. In the western section of the Far North there are two all-weather roads (one north of Red Lake and the other north of Pickle Lake). Otherwise, access to most of the First Nation communities is via air or seasonal winter roads. These roads are vulnerable to shorter operating seasons, load restrictions and closures due to storms, as a result of climate change.

Rail infrastructure is also limited. The Far North’s only railway is the Ontario Northland line which connects Moosonee to Cochrane and Highway 11.

Far North Act, 2010

The purpose of the Far North Act, 2010 is to provide for community based land use planning in the Far North that:

- sets out a joint planning process between the First Nations and Ontario;

- supports the environmental, social, and economic objectives for land use planning for the peoples of Ontario; and

- is done in a manner that is consistent with the recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, including the duty to consult.

The Act sets out four objectives for land use planning:

- A significant role for First Nations in the planning.

- The protection of areas of cultural value in the Far North and the protection of ecological systems in the Far North by including at least 225,000 square kilometres of the Far North in an interconnected network of protected areas designated in community based land use plans.

- The maintenance of biological diversity, ecological processes and ecological functions, including the storage and sequestration of carbon in the Far North.

- Enabling sustainable economic development that benefits First Nations.

Community Based Land Use Planning

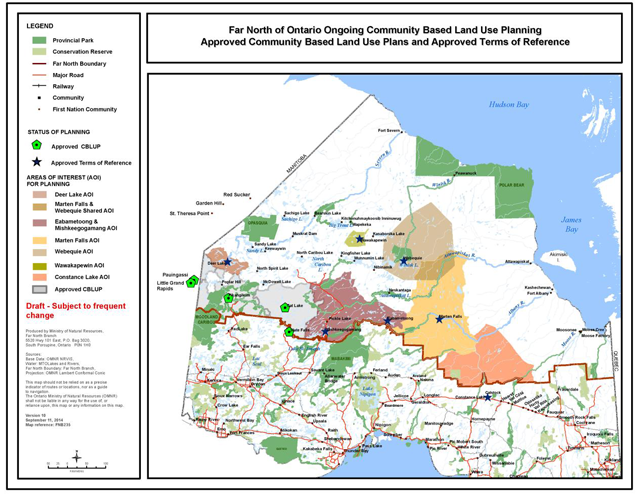

Across the Far North, many First Nation communities are engaged with Ontario

Enlarge Figure 4 map of ongoing community based land use planning (PDF)

Community based land use planning is initiated by First Nations and plans are jointly developed and approved by First Nations and Ontario. Land use planning describes how land and water will be used while sustaining the people and the resources into the future. Land use designations in the plans provide the broad direction on what land uses will be permitted in which areas. Further approvals (e.g. under the Environmental Assessment Act) are typically required for specific proposed projects.

Most major development cannot proceed in the Far North until a community based land use plan is in place. Activities that can proceed include mineral claim staking and exploration, environmental clean-up and feasibility studies. Some other development can proceed before a plan is in place if an exception or exemption applies (as set out in section 12 of the Far North Act, 2010).

The community based land use planning approach builds upon a respectful working relationship between First Nations and Ontario, using consensus-based decision- making. Public consultation occurs throughout the planning process.

Further information on how plans are developed is provided in Part B.

Far North Land Use Strategy

Under the Far North Act, 2010, the Minister of Natural Resources must ensure that a Far North Land Use Strategy is prepared. The Strategy will assist joint planning teams to prepare community based land use plans and will guide the integration of matters that are beyond the geographic scope of the individual plans.

Once the Far North Land Use Strategy is in place, joint Ontario-First Nation planning teams must take it into account as they prepare community based land use plans. The diagram below shows the relationship between the Strategy and individual community based land use plans, and sets out the content of the Strategy.

Figure 5: The Far North Land Use Strategy and community based land use plans

Figure 5 converted to text for accessibility

- Far North Land Use Strategy

- Supports community based land use plans

- Has a Far North wide scope

- Joint planning teams will use the guidance to consider these matters when creating a land use plan.

- Will contain topics suggested in this discussion paper:

- Cultural and heritage values

- Biological diversity

- Water

- Cumulative effects

- Climate change

- Areas of natural resources value for economic development

- Infrastructure

- Tourism

- Protected area design

- Will contain policies on:

- Categories of land use designations

- Categories of protected area designations

- Amending community based land use plans

- Community Based Land Use Plans

- Must take into account Far North Land Use Strategy

- Have a community level scope

- Are First Nation initiated and led

- Individual community level

- Joint planning team with Ontario

- Determine land use designations

- Development shall be consistent with land use designations of the plan

Guidance on land use planning topics

The Far North Land Use Strategy will contain guidance on topics of relevance to land use planning in the Far North (see suggested list of topics in Figure 5 above.) The Strategy will provide guidance to joint planning teams on how to consider these topics when they are preparing individual community based land use plans. This discussion paper suggests topics to be addressed in the Strategy and invites discussion on suggested guidance.

The Strategy will support a community focused, consensus-based, comprehensive and long-term approach to planning in the Far North, and recognizes the need for linkages and consideration of cultural, environmental, economic and social topics.

The Far North Land Use Strategy will be more than a set of individual topics. When more than one topic is relevant to a situation or area, joint planning teams consider all of the applicable topics and information to understand how they may work together.

The principles and guidance for each topic will assist joint planning teams in understanding how the topics should be considered together in developing plan direction.

The Strategy will help joint planning teams to understand and consider existing provincial policies and legislation, and how they apply to land use planning in the Far North.

Policies on designations and amendments

The Strategy will also include policies on:

- categories of land use designations;

- categories of protected area designations; and

- the process and requirements for amending community based land use plans.

A joint body and Far North policy statements

Under the Act the Minister may establish a joint body

to advise on the development, implementation and coordination of land use planning in the Far North. If a joint body is established, it may recommend policy statements to the Minister who would issue the statement with the approval of Cabinet. The Far North Land Use Strategy will contain all Far North Policy Statements that may be issued from time to time. Section 7(7) of the Act contains a list of topics to which a Far North policy statement may relate:

- Cultural and heritage values

- Ecological systems, processes and functions, including considerations for cumulative effects and for climate change adaptation and mitigation

- The interconnectedness of protected areas

- Biological diversity

- Areas of natural resource value for potential economic development

- Electricity transmission, roads and other infrastructure

- Tourism

- Other matters if the Minister and the joint body agree

The joint body will be established if First Nations and the Minister agree. It will have equal numbers of First Nation community members and Ontario officials. While there have been discussions with First Nations in the Far North, there has not yet been agreement on moving forward with establishing a joint body.

Until such time as a joint body is established, the Strategy will include guidance for planning teams on land use planning topics. If in the future a joint body is established, and Policy Statements are recommended and approved by Cabinet, the Strategy would be amended to include those Policy Statements which would then replace any guidance contained on the same topic(s).

What will inform the preparation of the Strategy?

First Nations knowledge, perspectives and advice will inform the development of the Strategy. Discussions between the ministry and First Nation communities have begun and will continue, to build a shared understanding of views and interests as the Strategy is developed. Input from the public and stakeholders is also important and comments and input are welcomed at each stage.

The following will also inform the preparation of the Strategy:

- Community based land use plans that have already been completed, and the experience that First Nations and Ontario have gained from over 15 years of working together on planning;

- The objectives for land use planning set out in the Far North Act, 2010 (the objectives are listed here); and

- Existing provincial policy and legislation in areas such as biodiversity, climate change, protected areas and natural resource development.

- Further information about how completed plans and existing provincial policy are being used to develop guidance for the Strategy is provided in Part B and Part C.

Our First Nations (Cat Lake and Slate Falls) have worked together with the ministry to prepare a land use plan. Now we need to continue work to understand each other and build guidance to support planning. Sharing to bridge cultural understandings will help us and will help other communities with their planning. In this way, we will have a say in planning now and in the future.

Our cultures have different understandings of the earth. Let’s work with our differences as they are strengths.

Wilfred Wesley, Land Use Planning Coordinator, Cat Lake First Nation

Part B: understanding community based land use planning

It is important to understand the community based land use planning process in order to think about what guidance and policies are needed to support planning. This section of the paper provides information on the planning process and a description of plans that have been developed to date.

The planning process

Plans are developed through a respectful, consensus-based process which is described below:

Early dialogue and preparation for planning:

- Interested First Nation initiates the planning process with the ministry.

- A joint planning team is established (First Nation and the ministry

footnote 3 ). - First Nation community elders and members that know the land guide planning and contribute their understandings and perspectives. This includes documenting and interpreting Aboriginal traditional knowledge (for example on cultural values and ecological information such as plant, fish and animal biodiversity and changes over time).

- The best available information from all sources, including Aboriginal traditional knowledge and scientific information, is assembled early in the planning process. Additional information may be contributed during the planning process to support decision-making.

- All values significant to the First Nation and/or Ontario are considered.

Terms of Reference:

- A Terms of Reference is developed and jointly approved by the First Nation and Ontario. Terms of Reference set out the process to complete a plan and provide guidance for establishing a planning area.

- The First Nation leading a planning process extends invitations to neighbouring First Nations to discuss areas where they share interests and to ultimately confirm a planning area for the land use plan. This may include discussions with communities outside Ontario who have indicated they have an interest in planning activities underway in Ontario.

- The approved Terms of Reference is posted on the Environmental Registry, and open houses are held to invite early input to the planning process from community members, stakeholders and the public.

Building a draft and final plan:

- Community and provincial objectives are described, leading to a description of shared objectives for the plan.

- The planning team draws upon the community and provincial subject matter experts to support wise decision-making. For example, provincial advisors from the Ministry of Northern Development and Mines (MNDM) work with the planning team and community to build an understanding of geology.

- A draft plan is developed setting out land use areas and permitted activities. Plans also may offer guidance or principles on the manner in which activities take place.

- Plans are developed with an understanding that existing uses and tenure must be respected4 4

footnote 4 . Information on current mining claims from MNDM CLAIMaps internet site is an important part of the planning process. - Plans address land uses and features in areas adjacent to the planning area that the joint planning team has identified. This requires conversations with neighbouring communities, whether inside or outside Ontario, that may have an interest in the planning area or whose activities may affect the planning area.

- When a new protected area is being recommended in a draft plan, the ministry typically requests that MNDM withdraw the area from mineral claim staking. This will provide ongoing protection until a final decision is made about the area.

- Opportunities for input are provided during the development of the plan. Draft plans are posted on the Environmental Registry and open houses are held to invite comment. All input received is considered as the community based land use plan is prepared and finalized.

- The community based land use plan must be approved by the First Nation and the Minister of Natural Resources. Once approved, activities on the land must be consistent with the plan. Plans include direction to keep them current, including an implementation approach and a timeframe for review.

Plan implementation:

- The First Nation and Ontario continue to work together to guide the implementation of the plan to pursue opportunities. For example, a First Nation may seek Environmental Assessment Act coverage in order to prepare a forest management plan.

- The community based land use plan is kept current through scheduled reviews and amendments as required.

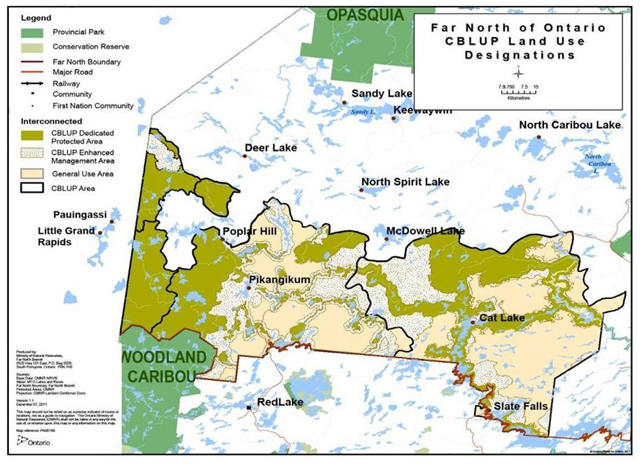

Overview of existing community based land use plans

In June 2006, Pikangikum First Nation and Ontario jointly approved the first community based land use plan, called Keeping the Land, A Land Use Strategy for the Whitefeather Forest and Adjacent Areas

. Since that time, three more community based land use plans have been jointly prepared and approved: the Cat Lake-Slate Falls Community Based Land Use Plan Niigaan Bimaadiziwin – A Future Life

; the Pauingassi Community Based Land Use Plan and the Little Grand Rapids Community Based Land Use Plan

The completed plans are pictured together in Figure 6 below.

Enlarge Figure 6 map of land use designations (PDF)

The plans set out land use areas; specify the land use designation for each area; and identify land uses and activities that are permitted or not permitted in each area. To date, planning teams have been relying largely on the designations used by the ministry south of the Far North boundary, as set out in the Guide for Crown Land Use Planning. Section C-3 of this paper includes further discussion of use of these categories and a discussion of whether these or other/additional designations will be developed for use in the Far North, as part of the Far North Land Use Strategy. The three designations used to date are described below:

- The General Use Area (GUA) designation (yellow colour on map) is applied in two of the four completed plans. A full range of resource uses can be permitted in GUAs. Policies for GUAs guide the manner in which activities will take place (e.g. new access can be subject to restrictions). This designation enables development opportunities that are both desirable and compatible with the First Nation-Ontario goals and objectives. Within the GUA, cultural and ecological features are afforded further protection through future resource management planning (e.g. forest management guidelines) and through project level environmental assessments and conditions on various permits and licences.

- The Enhanced Management Area (EMA) designation (speckled area on map) is applied in three of the four plans. This designation can be used to provide more detailed land use direction in areas having special features or values. A wide range of uses can occur in EMA. In some areas, specific uses may be subject to conditions, in order to maintain the features or values that make the area special. EMA designations can be divided into sub-categories based on the land use intent for the area. Far North planning teams to date have applied the sub-categories of Remote Access, Recreation, Fish and Wildlife, and Cultural Heritage.

- The Dedicated Protected Area (DPA) designation (green area on map) is applied in all four plans. This designation is applied where there is an interest in keeping areas free from industrial development, and/or where there are sensitive ecological or cultural features and landscapes. Traditional uses of the land, such as hunting and fishing, continue in all designations including Dedicated Protected Areas. DPAs identify land uses and activities that are permitted and those that are not-permitted, including the activities set out as not-permitted in the Far North Act, 2010. This broad land use category was initially used during the Whitefeather Forest planning project with the intent that further discussion about types of protected areas and potential options for regulatory mechanisms would continue. All completed plans indicate that long-term direction for the DPA is to be determined through additional First Nation-MNR dialogue.

The Far North is a landscape largely undisturbed by industrial development, containing healthy ecological systems. It is home to First Nations who know and rely on the land and who have protected it over time. It is essential to care for all lands and waters into the future. Land use planning can contribute to healthy ecosystems for the future in several ways. Protected areas are an important tool in the conservation of natural systems, but how activities are planned and carried out elsewhere is just as important.

Plans can apply tools in legislation and policy that provide for protection of lands, waters, and cultural and ecological values in all land use designations, while enabling development in appropriate areas.

The suggested guidance included in this discussion paper builds on the approach and process that has been used to develop plans to date. Joint planning teams and the Minister must take into account the Far North Land Use Strategy as it exists at the time. As existing community based land use plans are reviewed and amended in the future, the Strategy will need to be taken into account.

Part C: developing guidance to support planning

The discussion topics are presented in three parts:

- C-1 - Developing a vision for the Far North that will set context for individual community based land use plans.

- C-2 - Guidance on land use planning topics; and

- C-3 - Policies on Designations and Amendments.

This paper conveys early thinking on potential guidance to encourage discussion. Input on the discussion paper will be considered in preparing the Draft Strategy, and there will be opportunity for additional review and comment.

This discussion paper has been drafted respecting that the dialogue between Ontario and First Nations on the Far North Land Use Strategy is just beginning: First Nations’ knowledge, perspectives and advice, including Aboriginal traditional knowledge, will be critical to the development of the Strategy. The Far North Act, 2010 recognizes in particular that First Nations may contribute their traditional knowledge and perspectives on protection and conservation for the purposes of land use planning under this Act

.

This paper reflects our evolving understandings through land use planning and related initiatives. Preliminary suggestions for guidance on land use planning topics draw upon the experience and direction set out in the first four community based land use plans completed since 2006. (Description of completed plans starts on the Overview of existing community based land use plans section).

C-1: A vision for the outcome of land use planning in the Far North

Land use planning and decision-making in the Far North supports the achievement of long-term goals and objectives identified by First Nation communities and Ontario.

A vision can provide a clear expression of long-term desired future outcomes that the goals and objectives of a land use plan are working towards. This sets the tone for decision-making, conveying priorities and expectations. Cultural, social, environmental and economic interests can be woven together in vision statements. This helps planning teams prepare direction that is strategic and connected.

In individual community based land use plans completed to date, vision statements have been prepared by First Nation communities, including expressions of future desires such as: the well-being of future generations; protection of lands and waters; and enabling potential for resource-based opportunities.

In Ontario, vision statements have been included in other planning and policy documents, including the Growth Plan for Northern Ontario (2011), the ministry’s Our Sustainable Future (April 2011), and Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy (2011).

In this discussion paper, it is proposed that land use planning and decision-making in the Far North would benefit from an overarching vision for the long-term outcome of land use planning in the Far North. This vision would be included in the Far North Land Use Strategy. If a vision statement for the outcome of community based land use planning is included in the Strategy it should reflect the desired outcomes of First Nations people who live in the Far North, and all Ontarians. A shared vision statement might speak to working together in a positive relationship for the benefit and health of people, land and waters.

Input and ideas on a vision statement to guide land use planning in the Far North are being welcomed through this discussion paper.

C-2: guidance on land use planning topics

The Far North Land Use Strategy will provide guidance to help joint planning teams consider broad-scale planning matters when developing community based land use plans.

This section of the discussion paper presents initial thinking on possible guidance related to a number of land use planning topics. The suggested list of planning topics set out below is based on the policy matters identified in the Far North Act, 2010, section 7(7). Additional topics (such as water) have emerged as important and relevant topics addressed in community based land use plans to date. Additional or different planning topics may also be considered based on input received.

Land Use Planning topics suggested in this paper are:

- Cultural and heritage values

- Biological diversity

- Water

- Cumulative effects

- Climate change

- Areas of natural resource value for economic development

- Infrastructure

- Tourism

- Protected Area Design

While the topics are discussed separately, they are clearly related to one another. Guidance on planning topics will reflect an integrated approach to planning that recognizes connections among policy areas. The order of planning topics does not imply priority.

As noted previously, suggested guidance on each topic draws upon the experience and direction from plans already completed. Existing provincial policy and legislation on these planning matters is also a foundation for the suggested guidance.

Provincial policies and strategies express broad outcomes to be achieved through land use planning and related decision-making processes. Some examples of provincial and the ministry strategic-level policies that influence community based land use planning are:

- Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy (2011);

- Ontario’s Mineral Development Strategy (2006);

- the Strategic Plan for Ontario’s Fisheries;

- MNR and other ministries’ Statements of Environmental Values under the Environmental Bill of Rights;

- The ministry’s strategic directions document, Our Sustainable Future (2011); and

- The ministry’s Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (2011-14).

The Provincial Policy Statement, 2014 under the Planning Act is another example of provincial strategic-level policy. Although it does not apply to lands subject to the Far North Act, it does provide important insight into policy direction in place for municipal land use planning.

Provincial plans that provide general direction for the Far North include the Growth Plan for Northern Ontario and the 2013 Long-Term Energy Plan. The Far North Land Use Strategy can provide guidance on how to apply relevant policies and plans like these to community based land use planning in the Far North.

In this section, the discussion of each planning topic includes:

- A brief description of the topic generally and in the context of the Far North, including how the topic relates to land use planning;

- Possible principles to support decision-making in planning; and

- Suggested guidance for planning teams.

Topic 1: cultural and heritage values

Cultural and heritage values are places, structures, or objects on the land that are important to the culture and traditions of a group, or that help us understand the history of an area. Such values may include specific locations such as archeological sites and important buildings and structures, and also broader landscapes that have cultural or historic importance. Much of the knowledge of cultural and heritage values in the Far North rests with the First Nations and is based on their past and current relationship with the land. Values important to First Nation communities may include burial and other individual places of importance, or land and water associated with areas of traditional use (e.g. travel routes, hunting and trapping areas). Often, First Nations will express that their entire traditional territory is of cultural importance, and that the land provides the foundation for their culture and way of life.

Community based land use planning provides an opportunity to protect values through land use designations. For example, a planning team could apply a protected area designation that permits little or no development. Alternatively, a more open designation (such as an Enhanced Management Area) could be applied that allows development but also provides for enhanced protection of the area’s values through conditions or restrictions placed on those developments. These land use designations provide the broad direction on what land uses will be permitted in which areas. A variety of other provincial legislation and policies, including the Ontario Heritage Act, Mining Act and Environmental Assessment Act can also protect these values. Community based land use planning can complement these other tools and processes, several of which apply when developments are being proposed.

Documenting cultural and heritage values is a key early step in the planning process. The ministry provides funding and support for First Nation communities to gather Aboriginal traditional knowledge. This information is typically brought forward to the joint planning team and is interpreted by the community members. The information itself is considered sensitive and remains with the community. Ontario may have information such as archaeological reports or archival records that may be helpful in identifying cultural and heritage values in a planning area. The ministry can facilitate access to this information.

Information collected for land use planning may also be brought forward to other decision-making processes such as Environmental Assessment processes.

In addition to planning for known values, planning can also consider areas that have archaeological potential, and provide direction to protect these areas. The Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport has developed provincial criteria for determining areas of archaeological potential. Examples of these criteria include:

- Properties within 300 m of a water course;

- Elevated topography (e.g. eskers);

- Proximity to a resource-rich area (concentrations of animal, vegetable or mineral resources);

- Proximity to a known archaeological site; and

- Proximity to historic transportation routes (e.g. road, trail, portage).

The Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport has checklists which may help in identifying potential archaeological sites and other cultural heritage resources.

One of the objectives of the Far North Act, 2010 is the protection of areas of cultural value…in an interconnected network of protected areas

. In the four completed community based land use plans in the Far North, areas of cultural and heritage value are often included in Dedicated Protected Areas. In other land use areas, plans provide guiding direction to ensure these values are protected. Through planning, protection of cultural and heritage values can also lead to the development of related tourism opportunities, where communities believe it is appropriate.

Preliminary discussion – guidance on this topic:

Principles guiding decision-making on this topic will be suggested in the Draft Strategy. For discussion, suggestions for principles on this topic are:

- First Nations’ Aboriginal traditional knowledge, together with data and information brought forward by Ontario, will be applied to identify cultural and heritage values.

Guidance for planning teams will be proposed in the Draft Strategy. Building upon experience from completed and ongoing planning, suggestions for guidance include:

- Provide protection to cultural and heritage values throughout the planning area by assigning appropriate land use designations and direction in the plan:

- Consider where important cultural and heritage values can be included in a Dedicated Protected Area.

- Include direction in plans to protect cultural and heritage values in other land use designations (i.e. general use and enhanced management designations). In these areas, where there are potentially multiple interests, planning teams can provide protection by specifying what land uses are desired and compatible and how those land uses should take place. For example, eskers may be a valuable source of aggregate and therefore can be a potential location for aggregate extraction or a road corridor. They are also often the location of travel routes that are culturally important, and may also have archaeological potential and ecological value. Plans may direct that roads be developed in a manner that retains the integrity of the cultural and heritage features, and that culturally significant sites are to be avoided. Planning teams could apply a land use designation such as an Enhanced Management Area to emphasize that as development proceeds, impact to cultural and heritage values will be minimized.

- Consider the interests of other First Nation communities with respect to cultural and heritage values in the planning area. In many cases in the Far North, areas may be planned by one community, but are used and valued by other neighbouring communities. It will be important for communities developing plans to consider the cultural values held by other communities.

- Where suitable, apply tools that are available within the existing framework of legislation to protect areas of cultural and heritage value. For example, a plan could indicate that site-specific values will be considered for withdrawal from staking through the Sites of Aboriginal Cultural Significance process under the Mining Act.

- Where appropriate, provide for interconnections of culturally significant waterways in the design of protected areas.

For discussion: are the suggestions for principles and guidance appropriate for this subject? Are there other principles and/or guidance that should be included in the Draft Strategy?

Topic 2: biological diversity

Biological diversity, also called ‘biodiversity’, is the variety of life on Earth.

Biodiversity is essential to our quality of life, our economic prosperity and our health and well-being. All living creatures ultimately depend on biodiversity to survive. Maintaining levels of biodiversity is important for clean air and water, flood control, carbon storage, productive soils, fish and wildlife and it also provides opportunities for outdoor recreation and an abundant source of renewable resources.

Conserving biodiversity is important because healthy ecosystems sustain healthy people and support a healthy economy. Pressures on the conservation of biodiversity can be local to global in scale and include habitat loss, invasive species, air and water pollution, unsustainable use of resources, development pressures and climate change. The topic of biodiversity relates closely to many other topics in this paper including protected areas, water, climate change and cumulative effects. Some of these connections are explored below.

The Far North of Ontario has a natural wealth of ecosystem, species and genetic diversity. It provides essential habitat for species at risk like forest-dwelling woodland caribou, wolverine and lake sturgeon, as well as habitat for Ontario’s only populations of polar bears, beluga whales and snow geese. It also provides nesting habitat for millions of North American migrating birds and internationally important habitat for a wide variety of shorebirds.

Ontario’s framework for conserving biodiversity for present and future generations is set out in Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy (2011) and Biodiversity: It’s in Our Nature (2012). This framework sets out strategies to protect biodiversity (genetic, species and ecosystem diversity), reduce pressures that lead to loss of biodiversity and improve knowledge. It highlights the importance of considering biodiversity in land use decision- making. The framework also supports protecting biodiversity and ecosystem functions to maintain resilience (i.e. the ability to adapt, survive and recover from changes and disturbances such as climate change and pollution). Other actions in this framework include promoting landscape-level conservation planning - and protecting species diversity, including protecting species at risk, through the Endangered Species Act, 2007.

First Nations describe a holistic view of biodiversity. Their close relationship with the land has helped shape the ecosystems that now exist in the Far North and provides an important observational record of changes that have occurred across the landscape over generations. This symbiotic relationship with the land is a strong foundation for taking care of biodiversity in planning across the Far North.

The Whitefeather Forest Planning Area is a holistic network of both natural and cultural features that results from the relationship between Pikangikum people and our ancestral lands (Ahneesheenahbay ohtahkeem). This relationship (kahsheemeenoweecheetahmahnk) expresses a closeness that comes from our knowledge of the land, but also from a spiritual and emotional connection to the land. We refer to our ancestral lands as Ahneesheenahbay ohtahkeem with the understanding that the landscape has been physically modified and given cultural meaning by Beekahncheekahmeeng paymahteeseewahch. Pikangikum people have cleared and maintained waterway channels and portages, planted mahnohmin (

wild rice) throughout our traditional lands, and have used indigenous pyrotechnology to enhance the abundance of waterway and wetland vegetation which supports ducks and muskrats. Pikangikum people have also been formed by this land.For us, land and people are inseparable. Our Ahneesheenahbay ohtahkeem is not merely a landscape modified by human activity but a way of relating to the land, a way of being (on the land).

Excerpt from: Keeping the Land: A Land Use Strategy, June 2006, page 24

The Far North Act, 2010 sets out … the protection of ecological systems…

and the maintenance of biological diversity, ecological processes and ecological functions… including the storage and sequestration of carbon

as planning objectives. These objectives provide direction for biodiversity conservation that community based land use plans will take into account. Understanding the natural environment requires one to recognize the role of natural processes on the landscape such as, wind and fire and the complex interactions between animals, insects, and the surrounding natural environment. Furthermore, scientists advise that climate change may impact biodiversity in the Far North more than other parts of Ontario. Climate change could result in the loss of the southern limit of habitat for some species, while other species could see their ranges expand northward. Invasive and non-native species are likely to spread northward. There may also be a reduction in the extent and duration of ice cover on James and Hudson Bays upon which ice-dependent ecosystems rely.

Information on biodiversity in the Far North has many sources, including Aboriginal traditional knowledge. This knowledge can be instrumental in identifying changes in biodiversity, including the pace of change, and potential impacts of change on traditional uses of the environment. Independent and government-led information and science can also add knowledge that supports land use planning and subsequent decision-making processes. Information and data regarding biodiversity (e.g. areas with known values/habitat for species) should be collected and assessed early on in the planning process. Documenting the biodiversity in the Far North will be an ongoing task.

Land use planning can play an important role in maintaining biodiversity by assembling information, establishing an interconnected network of protected areas and providing direction for development on the intervening landscape that minimizes impacts on biodiversity. The needs of species at risk or species with unique or limited ranges should be assessed to ensure they are carefully considered. Land use plans inform and support the protection of biodiversity through other decision-making processes. To date, completed community based land use plans emphasize the importance of biodiversity to sustain culture and the environment, and as a foundation for economic opportunities.

Plans address both local and landscape-scale considerations.

Preliminary discussion – guidance on this topic:

Principles guiding decision-making on this topic will be suggested in the Draft Strategy. Suggested principles for consideration are:

- Planning will contribute to protecting biodiversity for a healthy environment that will sustain communities, provide for First Nation culture and traditional activities and support ecologically sustainable economic pursuits.

- In planning, landscape-level considerations, ecological processes and ecosystem-connectivity are fundamental considerations for maintaining biodiversity. Aboriginal traditional knowledge and scientific information should be considered in developing land use direction that will maintain biodiversity

- Careful consideration and continued use of new and emerging information on biodiversity will be critical to support good decision-making in the Far North. The Far North is a unique geography that we continue to learn more about.

Guidance for planning teams will be proposed in the Draft Strategy. Building upon experience from completed and ongoing planning, suggestions for guidance include:

- Design protected areas that will contribute to the conservation of biodiversity; for example promote expansive and connected, rather than small, isolated areas.

- Plan to maintain the full diversity of species and ecosystems that are representative of the planning area.

- Give special consideration to the protection of habitats at appropriate biological scales that support the life processes of species at risk such as woodland caribou, wolverine, polar bear, sturgeon and other valued species in the Far North such as brook trout.

- Consider how land uses may allow for or constrain ecological processes, like fire and other natural events, which are important in sustaining species and ecosystems. For example, fire may continue to be a desirable process in a large protected area, while it may not be desirable in areas close to communities, infrastructure or resource developments such as working mines.

- Provide direction to maintain biodiversity in all land use areas. For example, Enhanced Management Areas can be effective in promoting protection for values while sustainable development takes place.

- Carefully consider both short and long-term impacts to biodiversity in planning for potential future infrastructure development.

- Provide flexibility in plans to address new information about biodiversity as it becomes available.

For discussion: are the suggestions for principles and guidance appropriate for this subject? Are there other principles and/or guidance that should be included in the Draft Strategy?

Topic 3: water

Rivers, lakes and wetlands are major landscape features across the Far North. These features account for more than half of the total surface area. (reference: Aquatic Ecosystems of the Far North, page 5).

Far North water systems are largely free flowing and unchanged by development ( Go here for further information on current development). They provide important ecological connections across the landscape. Protection of water systems and water quality including sources of drinking water for communities is a high priority to First Nations and Ontario.

First Nation communities often describe water and water systems as vital to all life, and inseparable from their spiritual and cultural existence. First Nations’ settlement patterns were historically associated with waterways; as a result, many cultural, spiritual and burial sites are near waterways. Keeping waterways healthy is important for First Nations today for many reasons, including the continuation of traditional activities such as the harvest of waterfowl and fish, collection of traditional medicines, and for travel.

Water is the dominant, sensitive feature that supports all living things during various phases of life. Water to the land, is life…like blood in our veins that supports all functions of our existence and well-being. Cat Lake-Slate Falls Community Based Land Use Plan, page 8

The Far North Science Advisory Panel Report (2010) describes that water and associated aquatic systems perform a variety of ecological functions

. Healthy water systems support ecosystem processes, functions and biodiversity. Many wildlife populations, including species at risk, have specific habitat requirements related to water quality and water quantity. The report emphasizes the importance of headwaters in particular, noting that headwaters play a critical role in maintaining the integrity of downstream ecosystems.

The ministry is working together with First Nations and with other partners to assemble information and describe how watersheds, lakes, rivers and wetlands are connected across the Far North. Recent mapping of watersheds and water flows by the ministry is helping joint planning teams understand how land uses in one area can impact downstream areas, and can also assist in identifying natural water boundaries that can be used in planning (e.g. for delineating land use areas).

Information on water quality is also being collected in some areas where development is being planned (e.g. the Ring of Fire), and can help inform land use planning decisions in those areas.

Land use planning can provide direction for protecting water features. For example, planning can include sensitive and/or culturally important water features within protected area designations. It can also include direction on which land use activities should be limited or restricted to protect water, including protecting sources of drinking water.

Once development is proposed, further protection for water features is provided through other legislation such as the Environmental Assessment Act, the Ontario Water Resources Act, and the Environmental Protection Act.

Water and waterways have been a key focus in community based land use plans to date. The land use plans have used Dedicated Protected Area designations to provide for protection of water, headwater areas, associated traditional use, recreation and tourism. In many cases, Enhanced Management Areas are used in combination with Dedicated Protected Areas to complement protection efforts and reduce development pressures near waterways. For example, in the Cat Lake-Slate Falls plan, Dedicated Protected Areas were developed around significant lakes and rivers using a 500 metre buffer from the edge of the water feature. Adjacent Enhanced Management Areas were also established to provide some protection to areas that contribute water from the land base.

Infrastructure related to waste water, drinking water and floodwater management on Federal Reserve, municipal and private lands are outside the scope of Far North land use planning. However as noted above, community based land use planning can play a role in protecting lakes and rivers that are sources of water for communities.

Preliminary discussion – guidance on this topic:

Principles guiding decision-making on this topic will be suggested in the Draft Far North Land Use Strategy. Suggested principles for consideration are:

- Provide a high level of protection for water features that are necessary to maintain health and safety of drinking water and ecological and hydrological processes and functions.

- Protecting water systems will contribute to multiple objectives including establishing interconnections between protected areas, and protecting cultural values.

- Watersheds provide a meaningful landscape-scale for consideration of water in land use planning.

- Monitoring for changes in water quality or quantity over time can help inform future decisions.

- Consider opportunities for hydroelectric development in the context of other planning objectives.

Guidance for planning teams will be proposed in the Draft Strategy. Building upon experience from completed and ongoing planning, suggestions for guidance include:

- Identify culturally and spiritually important aspects of the water and waterways and provide direction supporting protection where appropriate

- Identify sensitive water, waterways and water features (including drinking water sources, shoreline and headwater areas), and identify land uses compatible with protection of hydrologic functions. Consider placing sensitive water features in a protected area designation, while less sensitive areas could be placed in an Enhanced Management Area with measures in place to ensure hydrologic functions are protected as any development is planned.

- Where appropriate, consider applying a protected area designation along a waterway, combined with an Enhanced Management Area to provide additional protection while allowing a range of resource activities.

- Use existing and emerging tools, such as watershed and subwatershed mapping tools, to understand the potential influences and impacts of decisions, and to help establish boundaries of land use areas using natural features

- Respectfully consider the potential impacts of planning decisions within the broader watershed. For example, a decision to permit a certain land use could (if the development proceeds) have impacts on downstream and potentially upstream areas and communities. As part of the planning process, planning teams should therefore engage and build consensus with other potentially affected communities in the watershed.

- Consider existing and proposed activities in areas upstream of the community, and what impacts those activities may have on water, when combined with new proposed land uses.

For discussion: are the suggestions for principles and guidance appropriate for this subject? Are there other principles and/or guidance that should be included in the Draft Strategy?

Topic 4: cumulative effects

Cumulative effects are changes to the environment over time as the result of combined effects from multiple activities and events (e.g. building roads, forestry activities, wildfires, etc.). Predicting cumulative effects requires considering human actions and natural events in combination with past, present and reasonably foreseeable future activities and events.

In the Far North, where new development is being proposed, our evolving understanding of cumulative effects and cumulative effects assessment will be important in making decisions that can ensure the maintenance of ecological integrity (i.e. self-sustaining natural ecological processes). An understanding of how changes to the land may affect species, key ecological processes, and ecosystems is needed.

Some species that live in the Far North, such as woodland caribou and wolverine, require large areas of land. Cumulative effects on species such as these need to be assessed at the appropriate scale. Both Aboriginal traditional knowledge and scientific knowledge are important sources of information about current conditions and changes to the land that have been observed. Aboriginal traditional knowledge can also contribute teachings on traditional approaches to using land and waters sustainably.

As the former Far North Science Advisory Panel (2010) stated, cumulative effects require careful attention as development progresses. Cumulative effects often cannot be predicted because the ways these interactions occur often are not well understood. Advice on scientific methods to assess cumulative effects is emerging. For example, setting limits on the extent of development may be a future consideration, but the understanding of what or how to set those levels is incomplete. Cumulative Effects Assessment is the name given to the process for assessing the combined effects of multiple activities. This assessment is best done across larger landscapes rather than small areas, and is also best applied together with an adaptive management approach. Cumulative effects are sometimes assessed as part of an environmental assessment process or through permitting and approvals for a development project.

At the land use planning stage, broad decisions are made about what activities may take place in the future. Land use plans play a role in reducing the potential for negative cumulative effects by guiding development to appropriate locations and ensuring protection for key ecological features and functions. As well, plans contribute to protection of features and functions at a landscape-scale, thereby enhancing the resilience of ecosystems. Plans can also provide guidance to support decision-making in subsequent planning processes such as environmental assessments. For example, existing plans provide guidance for minimizing roads, which will help reduce the potential for cumulative effects. Information and knowledge, including Aboriginal traditional knowledge, assembled to support planning can also contribute to future cumulative effects assessments.

Planning and policy tools to help in assessing cumulative effects continue to be developed. It will be important for Ontario and First Nations to draw upon the best available advice and tools.

Preliminary discussion – guidance on this topic:

Principles guiding decision-making on this topic will be suggested in the Draft Far North Land Use Strategy. For discussion, suggestions for principles on this topic are:

- Protecting ecological systems and directing development to appropriate locations will help to reduce or avoid cumulative effects. Aboriginal traditional knowledge and scientific information should be considered in developing land use direction that will reduce or avoid negative cumulative effects.

- Recognize that particularly vulnerable areas (e.g. headwater areas, coastal wetlands and permafrost areas) may require a high level of protection (e.g. through a protected area designation) to reduce or avoid the negative cumulative effects of development activities. (see Far North Science Advisory Panel Report, 2010, page 90).

- Long-term monitoring which includes First Nation involvement, and adaptive management, are important to allow for continuous learning and flexibility as knowledge of cumulative effects advances.

- Consider matters at both the local and landscape-scales (e.g. consider water- related impacts of land uses at the watershed scale; consider implications for caribou at the range-scale).

Guidance for planning teams will be proposed in the Draft Far North Land Use Strategy. Building upon experience from completed and ongoing planning, suggestions for guidance include:

- Consider applying available decision-support tools to assess the potential effects of different land use scenarios.

- Consider the extent of existing and planned developments and activities within and beyond the planning area when developing land use direction. Engage with neighbouring communities to discuss goals and objectives regarding desired types, locations and levels of development.

- Provide direction to minimize negative cumulative effects during subsequent processes such as environmental assessment. For example, plans could provide direction that, where remoteness is desired, road corridors and road density are to be minimized and/or that temporary, seasonal (winter) roads are preferred.

- Apply an adaptive management approach to planning. For example, plans could indicate that as new information on cumulative effects becomes available, necessary amendments to the plan will be considered.

For discussion: are the suggestions for principles and guidance appropriate for this subject? Are there other principles and/or guidance that should be included in the Draft Strategy?

Topic 5: climate change

Climate is the average weather (e.g. temperature, rainfall, and wind) in a region over many years. Climate affects most aspects of our society and is a major force in Earth’s water cycle (e.g. lake levels and river flows). Climate can also influence the distribution, abundance, and behaviour of plants and animals

Current scientific information on anticipated changes in the Far North is available on the ministry’s Climate Change webpage. As well, the Report of the Far North Science Advisory Panel (2010) offers a summary of information on climate change in the Far North along with a discussion of the implications for planning. Local knowledge about changes that are being observed is another important source of information.

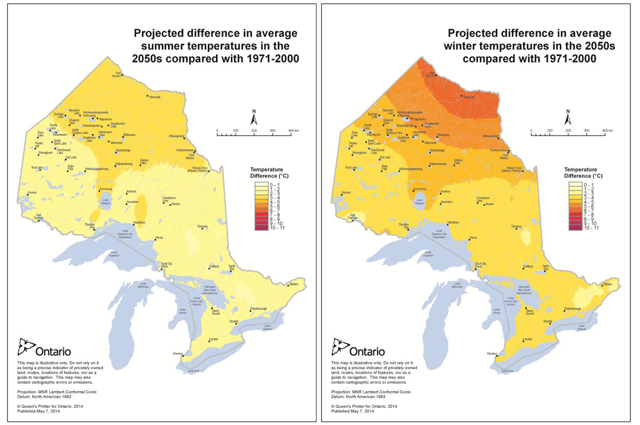

Climate change impacts are expected to vary across the Far North. It is likely that some of the most dramatic changes will occur in the most northern extent of the Far North, near the coast of Hudson Bay and James Bay

Enlarge Figure 7 projected difference in average summer and winter temperatures (PDF)

Much of the Far North consists of peatlandsFor further information on peatlands, which are particularly sensitive to changes in climate. As the world’s second largest peatland, it is estimated that peatlands in the Far North annually store an amount of carbon equal to about a third of Ontario’s total carbon emissions and act as a net carbon sink. Changes in peatland water levels will change the carbon storage, methane emissions and cooling roles of these systems. Similarly, warmer and longer summers combined with warmer and shorter winters may lead to the loss of permafrost ecosystems. In more forested areas, wildland fires are expected to increase. Research is underway to improve our understanding of how peatlands and forests may change under different future climate scenarios.

Responses by animal species to a changing climate are complex. Generally, the effects of climate change on species in the Far North will depend on the location of their range boundaries. Species that require a narrow range of temperature and precipitation conditions, or that are unable to migrate quickly as conditions change, will be at greater risk. Climate change will also affect fisheries, through changes in food web structure and the timing and success of fish reproduction; habitat disruption due to more extreme weather events; more invasive species, and; greater susceptibility to native and non- native pathogens.

Ontario has developed plans

Far North land use planning can play a role in helping to address climate change. Through the planning process, information about climate change can be shared to build awareness and understanding. Planning teams can then consider how to reduce the impact of and adapt to climate change. By incorporating review timelines and amendment provisions, land use plans can be updated to reflect new knowledge and conditions. The ministry and First Nations participate in climate change workshops and discussions to stay informed about changing climate and possible impacts. Vulnerability assessments (i.e. studies that examine a community’s vulnerability to climate change) can be included in the information used for planning. Climate change impacts are also typically considered in subsequent decision-making processes for specific development proposals.

Preliminary discussion – guidance on this topic:

Principles guiding decision-making on this topic will be suggested in the Draft Far North Land Use Strategy. For discussion, suggestions for principles on this topic are:

- Address climate change in planning by:

- building an understanding of potential impacts;

- contributing to mitigation efforts;

- providing for adaptation, keeping in mind that a range of actions may be required, and;

- considering climate variability.

- Long-term, local and regional climate change monitoring efforts are important to build information that can be considered in planning.

- Provide flexibility in plans to consider new climate change information or impacts.

- Design for the protection of biodiversity and natural heritage, including vulnerable areas and important natural systems, to help make species and ecosystems more resilient in the face of a changing climate.

Guidance for planning teams will be proposed in the Draft Strategy. Building upon experience from completed and ongoing planning, suggestions for guidance include:

- Increase awareness and understanding by:

- Assembling and considering available information such as historical weather and regional climate change projections and local knowledge to help understand the implications of a changing climate. For example, this information may highlight increased risk of flooding and forest fires, and this could in turn have implications for land use and planning for infrastructure.

- Exploring options for undertaking a climate change vulnerability assessment either to inform planning (if possible) and/or to inform the future review of the plan and development proposals.

- Explore options for mitigating climate change (i.e. reducing emissions of greenhouse gases) through land use planning by:

- Considering opportunities for renewable energy development, where such development would be desirable and consistent with other planning objectives.

- Identifying and providing appropriate protection for areas such as peatlands that are important sources for carbon storage.

- Provide direction for adapting to a changing climate by:

- Providing flexibility in plans to address new climate information or impacts.

- Providing direction for developments that may be proposed as a result of a changing climate. For example, a plan could anticipate the need to realign winter roads in future and provide direction for possible acceptable locations for such a road.

- Considering protection measures that could help reduce effects of a changing climate. For example, protecting waterways, headwater and shoreline areas could help mitigate against flooding due to increases in rainfall. Establishing large, interconnected protected areas will help species to move and adapt in response to a changing climate.

- Providing direction to guide development away from areas that may become unsuitable as the climate changes. For example, if it is expected that flooding or slope failure may increase in future, include direction in plans that any development (e.g. tourism operation, mine facilities) be set well back from areas of potential flooding or related erosion.

For discussion: are the suggestions for principles and guidance appropriate for this subject? Are there other principles and/or guidance that should be included in the Draft Strategy?

Topic 6: areas of natural resource value for economic development

Areas of natural resource value for economic development are areas that have renewable and/or non-renewable resources capable of supporting economic development. Natural resources in the Far North that could provide economic development opportunities include forests, sources of renewable energy (i.e. water, onshore wind, solar and bioenergy), fish and wildlife, minerals, aggregates, and potentially non-renewable energy including oil, natural gas and peat. Natural resource development in the Far North is relatively limited, but interest in further harvesting, extraction or use of these resources is growing.

One of the objectives for planning in the Far North Act, 2010 is: Enabling sustainable economic development that benefits First Nations

. The role of community based land use plans is to identify areas of natural resource value for potential economic development and to determine which activities are to be permitted and where by establishing land use designations. In this process, economic development is considered along with the objectives for protection and sustainability of culture and the environment. Plans are prepared recognizing that additional requirements will in most cases need to be addressed before development activities begin (e.g. environmental assessment, resource management planning, other permitting or licencing). These additional requirements help ensure that lands and waters are protected even in land use designations where development is permitted.

To date, completed plans in the Far North provide direction that respects existing economic development (e.g. mineral sector activities) and identifies where new opportunities can be pursued (e.g. commercial forestry, renewable energy, mineral exploration and mining). Plans also include strategic direction to inform subsequent processes such as environmental assessments. Plans ensure that local planning decisions do not prevent planning for interests such as access to potential mineral and other opportunities beyond the planning area. Enhanced Management Areas are used in plans to permit economic development while emphasizing remoteness and protection, for example by limiting or placing restrictions on access.

Information on natural resources found in the Far North is provided below.

Mineral development

The mineral potential of the Far North is largely untested. However, there are currently two mines in the Far North: The De Beers Canada Victor diamond mine is located in the Hudson Bay Lowlands west of the Attawapiskat First Nation, while the Goldcorp Musselwhite gold mine is located in the northwest on the Boreal Shield, south of North Caribou Lake First Nation.

In addition to these active mines, there are known deposits of gold, nickel, copper, diamonds, chromite and other minerals in the Far North. Recently identified deposits of chromite, nickel and other minerals in the area east of Webequie First Nation known as the Ring of Fire

are considered one of the most promising economic development opportunities in Ontario in a century.

Currently there is incomplete geological mapping and mineral exploration data in the Far North, largely due to limited, costly access. The location, extent and significance of the mineral potential of the Far North will be refined as access improves, and new mapping and exploration provide additional information.

The entire process of exploring and mining occurs over a number of stages called the mining sequence. It includes looking for minerals (exploration), finding them in sufficient quantities to make it economically worthwhile to extract (evaluation), removing those minerals (mining) and, once they have been removed, restoring all lands used to an acceptable state (closure).

Each stage of the mining sequence has an increasing environmental impact, but each stage affects a progressively smaller area. Through the sequence, an early exploration project may take place over hundreds of square kilometres, at the evaluation stage tens of square kilometres may be impacted, and if mining occurs the disturbed area is often less than five square kilometres. From start to finish, the mining sequence can take a very long time; exploration may take up to 20 years, mining activity can last 10 to 50 years, and closure typically takes 2 to 10 years.

Most efforts to find minerals in quantity, concentration and other conditions suitable to building a mine are unsuccessful. The odds of a mineral exploration project ever becoming a mine are estimated to be about one in 10,000. Nevertheless, prospective areas can be explored time and time again, when new knowledge and changing market conditions renew their appeal.

Mineral exploration is an on-going activity in the Far North. Currently there are approximately 50,000 16-hectare mining claim units and 118 mining leases in the area, with many exploration projects focussed in the Ring of Fire area. The locations of current and past mining claims and leases provide direct guidance of where mineral exploration and development may occur in the future. Mineral exploration can provide on-going employment, economic and social benefits to Far North First Nation communities and across Ontario. If a mine is developed, the mining stage can provide additional significant benefits.

The Ministry of Northern Development and Mines has a lead role in managing Ontario’s mineral resources under the Mining Act. The purpose of the Mining Act is to encourage prospecting, staking and exploration for the development of mineral resources in a manner that: minimizes the impact of these activities on public health and safety and the environment; and is consistent with the recognition and affirmation of existing Aboriginal and treaty rights in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, including the duty to consult. The Mining Act provides for access to lands for mineral exploration and staking except where lands have been designated as protected or have been withdrawn from staking.

Oil and gas

Currently there is no oil or gas development in the Far North of Ontario. Oil and gas resources occur in sedimentary basins, and there are two such basins in the Far North (the Hudson Bay and Moose River Basins) that could yield oil and gas. Oil and gas exploration and development are managed by the ministry under the authority of the Oil, Gas and Salt Resources Act and Part VI of the Mining Act.

Aggregates

Aggregate resources, such as sand, gravel and bedrock aggregate are an important component of roads, airports and other infrastructure. In parts of the Far North these aggregate resources are scarce, or may be part of natural features such as eskers that also contain important natural or cultural values. The limited available aggregate resources will be increasingly in demand for road construction and other infrastructure to access mineral deposits and communities. Planning ahead to ensure the long-term availability of aggregate resources to support the development and maintenance of infrastructure in the Far North will be important. Available surficial geology and bedrock geology mapping will assist with identifying locations where suitable aggregate resources may be found. Aggregate operations (pits and quarries) are regulated by the ministry under the authority of the Aggregate Resources Act.

Forestry

The area in the Far North with potential for commercial forestry has been estimated at 6 to 7% of the total area

Non-timber forest products

Forests also contain other materials with commercial potential, described as Non- Timber Forest Products, such as blueberries and other foods, and plants having medicinal properties. Areas having suitable resources are most often identified through local First Nation knowledge. There is limited engagement in this sector presently, but there is growing interest in the potential of Non-Timber Forest Products as a future economic opportunity. Factors affecting economic viability may include the abundance of the materials, product interest, production cost, and distance to markets.

Renewable energy generation

Limited commercial electricity generation exists at the present time in the Far North. Several hydroelectric generation facilities are located on the Moose River and its tributaries (within or close to the Far North southern limit). No large developments exist on the other large northern river systems – the Severn, Winisk, Attawapiskat, and Albany. Further waterpower development in the Moose River Basin north of highway 11 must proceed by way of co-planning with certain First Nations according to current policy. Individual sites within the Northern Rivers watersheds (see map below) are limited to 25 megawatts per the ministry’s 2014 Renewable Energy on Crown Land policy (PL 4.10.06), however the community based land use planning process provides the opportunity to review the 25 megawatt limit. A recent study commissioned by the Ontario Waterpower Association (2013) provides updated information on waterpower potential in the Far North and identifies waterpower opportunities close to various First Nation communities. Ontario’s 2013 Long-Term Energy Plan includes a commitment to identify hydro potential in northern Ontario, including potential sites close to off-grid First Nation communities. Waterpower development may have environmental, economic and social impacts that require consideration, both at the land use planning stage and during subsequent project review and decision-making processes (e.g. environmental assessment and other environmental approvals).

A lack of proximity to transmission and distance to markets limits the feasibility of commercial renewable energy generation in the Far North. However, investments in transmission, water, wind, solar and bioenergy resources could support industrial development such as mining and could also provide local alternatives to help reduce the dependency of Ontario´s off grid northern communities on diesel power generation.

The Long-Term Energy Plan indicates that Ontario is continuing to support and encourage participation by both First Nation and Métis communities in new generation and transmission projects. As set out in the ministry’s Renewable Energy on Crown Land policy (2014), access to public land in the Far North for on-shore wind, solar and waterpower development opportunities will only be granted to local Ontario First Nation communities and/or their partners.

Peat extraction