Forest management: cultural heritage

Provides the direction for preparing and implementing forest management plans.

Acknowledgements

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) thanks the individuals on the revision team for their work to prepare this Guide: Dean Assinewe, RPF (North Shore Tribal Council – Forest Unit), Heather Barns, RPF (Forest Policy Section OMNR), Renée Carrière (Forest Management Planning Section, OMNR), Andrew Hinshelwood (Regional Archaeologist, Ministry of Culture), Susan Collins Lindquist, RPF (Chapleau District, OMNR), and Peter Street, RPF (Ontario Forest Industries Association). The Forest Policy Section and the revision team also sincerely appreciated:

- the Provincial Forest Technical Committee, particularly Dr. John Pollock and former committee member Dr. Jean-Luc Pilon for their time and advice on the review and development process, content, and pilot testing approaches for this forest management guide;

- those who attended and shared their experience at the Aboriginal workshops in June 2004 and Summer 2005;

- the Ontario Ministry of Culture staff who provided input;

- individuals and forest management planning teams who participated in pilot testing and socio–economic impact analysis of the guide to make it a better product for all planning teams;

- Dr. Emmanuel Asinas who did the socio-economic impact analysis;

- archaeologists who provided input based on their experience; and the many others who provided advice for the project and feedback on the drafts.

Preface/executive summary

This Guide replaces the previous guide: Timber Management Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Heritage Resources (1991) (see section entitled Application of Guide). This new Guide gives an overview of what cultural heritage values are, their importance to society, and how they can be protected from potential impacts from forest management operations. For the purpose of this Guide, cultural heritage values have five classes: archaeological sites, archaeological potential areas, cultural heritage landscapes, historical Aboriginal values, and cemeteries. For each of these value classes, the Guide describes where to find information about the values, how to proceed when a value might be in more than one class, classified data awareness, roles in confirmation and verification of the values, and protection from forest management operations. The necessary monitoring to determine the effectiveness of the protection measures described in the Guide are discussed in the final section. The appendices deal with items such as the model used by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources to determine archaeological potential areas, integration of this Guide into forest management planning, and examples of how operational prescriptions might be documented in the applicable table in forest management plans. This Guide must be considered by forest managers when preparing forest management plans and carrying out forest management operations. The Ontario Ministry of Culture, through the Ontario Heritage Act, ensures that values like archaeological sites and archaeological potential areas receive the proper protection. Their legislation and policies must also be followed.

Summary of pilot testing

Condition 38e of the Declaration Order MNR-71 regarding MNR’s Class Environmental Assessment Approval for Forest Management on Crown Lands in Ontario requires new revised forest management guides to be pilot tested to assess their effectiveness and efficiency where feasible, with the advice of the Provincial Forest Technical Committee. Pilot testing of a draft version of this Guide was done on three forest management units: French Severn, Spanish, and Trout Lake Forests. Selected members of the planning teams for those management units received some general training on the draft Guide, read the draft Guide, and responded to scenarios they were given using the draft Guide. Based on this feedback a number of changes were incorporated into the Guide that make it clearer and easier to use. Ideas for training approaches were another important result of the pilot testing. Pilot testing on this Guide benefits all those who will use this Guide in the preparation of their forest management plans.

Summary of socio-economic impact analysis

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources is committed to doing a socio-economic impact analysis of all new forest management guides, as may be appropriate to the content of the guide. Socio-economic impact analysis has been undertaken in support of the draft Forest Management Guide for Cultural Heritage Values (Cultural Heritage Guide). The analysis is intended to quantify the wood supply impacts and give an indication of the wood costs, in order to consider the social and economic impacts of forest management guides.

The same three forest management units were used as for the pilot testing of the guide: French Severn, Spanish, and Trout Lake Forests.

A comparative impact analysis was undertaken to estimate the social and economic benefits and associated costs if the revised Cultural Heritage Guide (revised guide) is implemented in comparison to the current Timber Management Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Heritage Resources (current guide) and to the what-if scenario of not having a guide at all (no guide). Hence, the scenarios of current guide, no guide and revised guide were used to compare and analyze the potential impacts of instituting cultural heritage values in forest management. The no guide scenario is not a realistic undertaking as there are statutory obligations that must be met. However, this scenario does assist in quantifying the basic benchmark of implications of cultural heritage protection measures.

There is no defined way to assess the value of cultural heritage values. Generally they are not considered in a monetary sense, but rather as their worth to the understanding of our history and to those who have an interest in them. Cultural heritage represents the subjective historical experience of the many diverse groups, cultures, institutions, and people of Ontario. It is an important part of cultural identity, and identity, in turn is often closely linked to cultural landmarks, economic interests, and contemporary cultural practice. Although the identification of values is key in providing information to planning teams for protection from forest management operations, the resources (e.g. people, time, money) to do this is often limiting. However there is great benefit in doing this work not only for the protection of the values, but also to the Aboriginal community in terms of capacity building.

Although there are social benefits to protecting values, there is also a cost to the industry using the resource. The provincially-approved Socio-Economic Impact Model was used to simulate the no, current, and revised guide scenarios for each forest management unit to obtain the social and economic impacts. The key difference between the Socio-Economic Impact Model runs and therefore the results, is the wood volume available for each of the three scenarios. The wood volumes are lower for the revised guide compared to the current guide. The annual differences are as follows: French Severn 137m3, Spanish 711 m3, and Trout Lake 306 m3.

With the implementation of the revised guide, the mills that depend on Trout Lake, Spanish and French-Severn forests will tend to lose total provincial sales of approximately $52,000, $70,000 and $18,000, respectively. These losses however, are quite insignificant; representing merely 0.03% (Trout Lake), 0.05% (Spanish) and 0.1% (French-Severn) of gross sales. The reductions for employment and tax revenues are correspondingly small.

These values are the potential net impacts that to anticipate by using the revised guide instead of the current guide. These net impacts represent the opportunity costs of not using the wood in order to maintain the cultural heritage values. These costs also represent the proxy value, in dollar terms that we can attribute to the value or price of cultural heritage values within our forests. Thus, in the perspective of people and entities concerned with cultural heritage preservation (such as Aboriginal communities and cultural institutions) these net impacts are social or cultural benefits rather than costs. Under a scenario of no guide versus current guide, the opposite holds true: the forestry industry will tend to gain in terms of gross sales, employment and tax revenues, while important cultural heritage values will not be preserved. However, the anticipated gains for the forestry industry are quite small and as previously indicated, the no guide scenario is not a viable option. To gather the information for the section regarding the effect of the Guide on wood costs, planning team staff for the three forest management units were asked to provide data on what types of increased costs there were for each of four value types and what those costs were. Briefly their findings were as follows. Archaeological sites and historical Aboriginal values showed little difference in cost between the no, current, and revised guide scenarios. Both of these value types would likely be protected in the same manner regardless of the existence of a guide. Archaeological potential areas did not show much difference between the current and revised guide scenarios, assuming that the area identified as a value is the same. However, there are higher costs for either of the scenarios compared to the no guide. If the no guide scenario was an option, there would still be costs of archaeological assessment, less operational flexibility, and possible relocation of operations. For cultural heritage landscapes Spanish Forest staff felt that the current guide causes larger reserves to be left which also substantially increases road building costs. Therefore their comment was that the new guide would have less cost to implement in this respect and the no guide scenario the least. It should be noted that under the no guide scenario, it is not realistic to assume that archaeological sites, archaeological potential areas, historical Aboriginal values, and cemeteries would not have similar or the same areas of concern prescriptions. There are very small wood supply and wood cost impacts due to this version of the Cultural Heritage Guide. This is due to the low number of cultural heritage values the relatively small size of reserves that protect them.

Based on the socio-economic impact analysis for the three pilot test sites, the implications on wood supply and costs appear negligible (0.03 to 0.1%). The opportunity costs of cultural heritage preservation therefore are miniscule in comparison to societal benefit in preserving these values. In a policy context, pursuing this revised guide is therefore beneficial in meeting our social, economic and ecological sustainability objectives. The complete Socio-Economic Impact Analysis Report for the Forest Management Guide for Cultural Heritage Values, December 2006 is on file with Forest Policy Section, Forests Division, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Application of guide

The application of this Guide is effective as of April 1, 2007. It must be used in the preparation of ten-year forest management plans (Phase I) beginning with plans scheduled for implementation in 2008 and planned operations for the second five- year terms (Phase II) beginning with planned operations scheduled for implementation in 2012 in accordance with the requirements of the Forest Management Planning Manual (2004). For plan amendments categorized by the OMNR district manager beginning April 1, 2007, to the extent reasonably possible, those amendments will be prepared in accordance with this Guide. For contingency plan proposals provided to the Ministry of the Environment for endorsement beginning April 1, 2007, the contingency plan will be prepared in accordance with this Guide. Section 3.8, Non-Compliance Remedies, will be used when dealing with situations of non-compliance found beginning April 1, 2007. The Notice of Decision is posted on the Ontario Environmental Registry.

Forest managers on all forest management units are encouraged to begin to use appropriate parts of the guide (e.g. data practices and non-compliance remedies). Maps of archaeological potential areas will be prepared and provided to planning teams in accordance with the schedule for forest management plan renewal.

OMNR’s strategic directions and statement of environmental values

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) is responsible for managing Ontario’s natural resources in accordance with the statutes it administers. As the province’s lead conservation agency, OMNR is the steward of provincial parks, natural heritage areas, forests, fisheries, wildlife, mineral aggregates, fuel minerals, and Crown lands and waters that make up 87 per cent of Ontario. In 1991, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources released a document entitled OMNR: Direction ‘90s which outlined the ministry’s goal and objectives. They are based on the concept of sustainable development, as expressed by the World Commission on Environment and Development. This document was updated in 1994 with a new publication, Direction ‘90s…Moving Ahead 1995, Beyond 2000, and updated again in 2005 with Our Sustainable Future. Within OMNR, policy and program development take their lead from Direction ‘90s, Direction 90s…Moving Ahead 1995, Beyond 2000, and Our Sustainable Future. Those strategic directions are also considered in ministry land use and resource management planning. In 1994, the OMNR finalized its Statement of Environmental Values under the Environmental Bill of Rights. The ministry’s Statement of Environmental Values describes how the purposes of the Environmental Bill of Rights are to be considered whenever decisions that might significantly affect the environment are made in the Ministry. The Statement of Environmental Values is based on the goals and objectives of the OMNR as described in Direction ‘90s, Direction ‘90s…Moving Ahead 1995 , Beyond 2000 , and Our Sustainable Future since the strategic direction provided in these documents reflects the purpose of the Environmental Bill of Rights.

During the development of Forest Management Guide for Cultural Heritage Values, the ministry has considered Direction ‘90s, Direction ‘90s…Moving Ahead 1995, Beyond 2000, Our Sustainable Future, and its Statement of Environmental Values. This Guide is intended to reflect the directions set out in those documents and to further the objectives of managing our resources on a sustainable basis.

Cultural heritage values overview

Flow chart showing the Cultural Heritage Values Guide The chart is divided into three columns where the last two columns showing examples and information for the question in column one which is titled “Which value class(es) (A cultural heritage value may be more than one class. Section 1.4 describes this in more detail.) does the cultural heritage value belong?

- Archaeological site: A location that is registered with the Ministry of Culture.

- Examples:

- Aboriginal village, pictograph

- For more information in this Guide:

- Description p. 9, data p. 18, and protection p. 28.

- Examples:

- Archaeological potential area: The output of the archaeological potential model, prepared by MNR and provided to planning teams by the provincial cultural heritage specialist.

- Examples:

- Maps provided by OMNR

- For more information in this Guide:

- Description p. 9, data p. 19, and protection p. 31.

- Examples:

- Cultural heritage landscape: A defined geographical area of heritage significance which has been modified by human activities and is valued by a community.

- Examples:

- Point: building or work,

- Linear: trail, portage, road, railway, traditional travel corridor,

- Polygon: fur trade post, logging camp.

- For more information in this Guide:

- Description p. 10, data p. 19, and protection p. 36.

- Examples:

- Historical Aboriginal value: Mapped places with cultural heritage value to an Aboriginal community.

- Example:

- Aboriginal brutal site, pictograph, fur trade post.

- For more information in this Guide:

- Description p. 12, Data p. 20, and Protection p. 42.

- Example:

- Cemetery: Where human remains have been buried and could contain grave markers, fences, mausoleums, or other structures.

- Examples:

- Cemetery, Aboriginal burial site

- For more information in this Guide:

- Description p. 16, data p. 20, and protection p. 44.

- Examples:

1.0 Cultural heritage values

1.1 Legislative framework

Ontario’s forest management planning system for Crown forests is based on a legal and policy framework that has sustainability, public consultation, Aboriginal peoples’ involvement, and adaptive management as key elements.

The Environmental Assessment Act and the Crown Forest Sustainability Act are the primary statutes that provide the legislative framework for forest management on Crown lands in Ontario. The Environmental Assessment Act defines the environment to include, among other things, “the … cultural conditions that influence the life of humans or a community, any building, structure, machine or other device or thing made by humans, … or any … interrelationships between … them”. This Act also has, as its purpose, “the betterment of the people of … Ontario by providing for the protection, conservation and wise management … of the environment.”

The Crown Forest Sustainability Act is Ontario’s key forestry legislation that provides for the sustainability of the Crown forest and governs forest management on Crown land. The Crown Forest Sustainability Act requires a forest management plan (FMP) to be prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Forest Management Planning Manual. The Forest Management Planning Manual, which incorporates the forest management planning requirements of the Crown Forest Sustainability Act and the provisions of the environmental assessment approval under the Environmental Assessment Act, contains the direction for preparing and implementing forest management plans. Consistent with forest management planning, forest managers plan to ensure the long-term health of Ontario’s forests, provide for a sustainable supply of benefits (e.g. timber and other commercial products, recreation opportunities, and wildlife habitat), while minimizing the adverse effects on forest values, including cultural heritage values.

The Forest Management Planning Manual (2004) requires that forest management guides, identified in the Forest Operations and Silviculture Manual (1995), be used in the preparation and implementation of a forest management plan. The Forest Information Manual (2001), currently under revision, prescribes the mandatory information and information products required by the Ontario Minister of Natural Resources and the forest industry.

The Ontario Heritage Act is administered by the Ontario Ministry of Culture. The legislation provides for the protection of properties of cultural heritage value or interest. Part VI of the Act speaks to the conservation of resources of archaeological value. According to the Act, an archaeological site must not be altered unless the work is conducted under the terms of a valid archaeological licence issued by the Ontario Minister of Culture. As permitted by Part VI of the Act, standard terms and conditions are attached to all archaeological licences issued. Among these conditions is a requirement that all archaeological field work conform to Ontario Ministry of Culture’s current standards and guidelines for consultant archaeologists. The Act also states that a detailed report of all archaeological fieldwork undertaken is to be submitted to Ontario Ministry of Culture for review. The Act and archaeological licensing terms and conditions direct matters such as the registration of archaeological sites, recommendations for protection, and mitigation of impacts to archaeological sites in development contexts and disposition of archaeological collections. Part III.1 of the Act states that standards and guidelines for provincial heritage properties will be developed. These standards and guidelines were being written by the Ontario Ministry of Culture at the time of this Guide’s approval. Any Ontario Ministry of Culture standards and guidelines that are developed for Crown land pertaining to the forest management context will need to be followed. This Guide does not supersede any legislation, regulation or order in council developed by the Ontario Ministry of Culture (e.g. Ontario Ministry of Culture Provincial Standards and Guidelines, Part III.1).

The experience with implementing the Timber Management Guidelines for the Protection of Cultural Heritage Resources (1991) and the work by and expertise of the revision team were key in preparing this Guide. This Guide was primarily written for planning teams to use when preparing and implementing forest management plans. However, others who are involved in the protection of culture heritage values in the forest management context (e.g. Aboriginal community members, Ontario Ministry of Culture staff, archaeologists performing archaeological assessments for Crown land forest operations, and Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR)forest management planning specialists) will also find it helpful.

1.2 Cultural heritage values defined

Cultural heritage is defined in relation to the community which derives some sense of its identity from a shared history of beliefs, behaviours, or practices. For the purposes of this guide, the communities defined may be broad, such as the people of Ontario or members of Grand Council Treaty #3, or specific, such as farm pioneers of Jones County. Many communities that express an interest in cultural heritage are actively engaged in practices that are derived from the shared history and the actions of individual members of the community derive their sense of belonging through this practice. However, while cultural heritage is based on activities or beliefs of their forbearers, it is not necessary that the community continue to practice these traditions actively. Many heritage practices continue only in a ritualized form. One example would be an agricultural society which expresses a strong interest in preserving the cultural heritage of farming in a region, but whose members are largely engaged in non-agricultural professions, where the group preserves its identity through an annual “fall fair” or similar event.

Currently, the Ontario Heritage Act and regulations do not define cultural heritage, but in reviewing a number of Ontario Ministry of Culture documents the following definition is provided: cultural heritage is the memory, tradition and evidence for the historical occupation and use of a place, and the consideration of this evidence in contemporary society in developing group identities. Aboriginal people may view cultural heritage as an activity that continues to be practised, but in a different place from the past. This is not part of the definition for this Guide.

This Guide attempts to address the cultural heritage interests of diverse cultural groups. Their history of creating or using a landscape, and the physical features or structures that, through time, are important in the traditions, beliefs or institutions of the group constitute a cultural heritage value. This Guide includes provisions for the protection of cultural heritage values, as defined by this Guide, from potentially adverse impacts by forest management activities, in order that current and future members of the groups or students of cultural heritage might learn from or reflect upon them. Cultural heritage values for the purpose of this Guide are divided into five classes. Section 1.4 describes them.

1.2.1 Cultural heritage resources: Fragile, non-renewable and rare

Cultural heritage values are unique to the people who created them and the time they were created; therefore, they are non-renewable. For example, fur trading activity might be reflected in the archaeological record by the remains of subsoil building foundations and artifacts around them. Similarly, abandoned early community sites might hold significance for the individuals who occupied them or their families, descendants, or communities; abandoned railway towns or Aboriginal villages have fragile, intangible components that might not be recognized by others.

Most cultural heritage sites have experienced some level of deterioration from the time of abandonment. In the case of archaeological sites, cultural context might have become obscured through time, and much of the physical context might also have deteriorated. Nevertheless, the spatial relationships of materials on the site can provide considerable information on both cultural and physical context. It is critical that cultural materials (objects, artifacts, features, and sites) be viewed and valued in context.

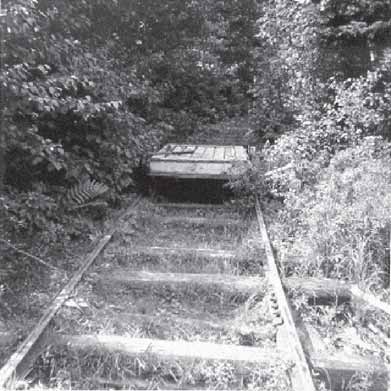

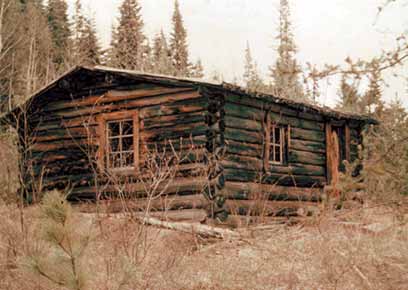

1.2.2 Visibility of values

An important consideration in planning for cultural heritage values protection is the concept of visibility. The visibility of a value is related to how readily an individual could identify traces of the past occupation or activity undertaken at the site. Figure 1 demonstrates this through pictures of two building sites: one visible and the second invisible to most. For most archaeological sites, visibility increases with the abundance of material. Visibility, in terms of the number of objects present, may stand as a measure of archaeological significance, but for many historical Aboriginal values, significant cultural activities might have left limited physical traces. Visibility can also be described in terms of how well it can be seen under normal conditions. As an example, buried archaeological sites are not usually visible, while the visibility of abandoned mine headframes is obvious. For most values, visibility is affected by season of observation and vegetation cover.

Figure 1: Visibility of cultural heritage values

These two pictures demonstrate the range in visibility of values. The top one is a derelict milk house which is a few feet above ground. In the background of the other photo there is a small rise, caused by the foundation of an old building. This is an example of how cultural heritage values can be invisible to the untrained eye.

1.3 Possible effects of forest management activities on cultural heritage values

Forest management activities can be planned and carried out in a manner to prevent or minimize adverse effects on cultural heritage values. Although there may be a monetary cost to the forest industry in doing this, benefits are derived for all the participating parties. These benefits are listed along with possible adverse effects if this Guide did not exist or its standards and guidelines were not followed.

Potential beneficial effects

There are beneficial effects related to careful consideration of cultural heritage values in the planning and implementation of forest management activities.

Forest industry benefits:

- improved protection of cultural heritage values in forest management;

- improved relationship and trust between industry and Aboriginal community; and

- contribution to addressing conditions for most forest certification systems.

Aboriginal benefits:

- improved opportunity for Aboriginal communities to participate in forest management planning;

- information gathered from Elders before more knowledge is lost forever;

- continued development of historical Aboriginal values maps and databases; and

- improved relationship and trust between planning team and Aboriginal communities and individuals.

Public benefits:

- conservation of Ontario’s rich heritage;

- improved communication among forest users;

- increased awareness of local and regional cultural heritage; and

- increased understanding of forest management planning and forest operations.

Potential adverse effects

Forest management activities have the potential to cause a range of adverse impacts to cultural heritage values. Many of these impacts are considered to be long-term, permanent, and irreparable. Use of this Guide will prevent or minimize these effects.

Physical impacts:

- damage or destruction of physical or material features;

- loss of context information by damage to the relative horizontal or vertical location of artifacts with each other or to natural or cultural soil layers;

- changes to physical environment, accelerating natural rates of deterioration; and

- loss of plant, animal or forest cover associated with spiritual or ceremonial locations (e.g. medicinal plants).

Social impacts:

- interference with spiritual or ceremonial activities; and

- increased access to sites for artifact collecting and other inappropriate uses.

1.4 Classes of cultural heritage values

Five classes of cultural heritage values are defined for the purpose of this Guide. The five classes are:

- archaeological sites,

- archaeological potential areas,

- cultural heritage landscapes,

- historical Aboriginal values, and

- cemeteries.

The classes have been designed partially to reflect the group or agency which has the authority for their protection. The Ontario Ministry of Culture has authority over the protection of archaeological sites and archaeological potential areas. Historical Aboriginal values are gathered and protected in cooperation with an Aboriginal community. The Cemeteries Act governs how cemeteries must be registered and protected. For the most part cultural heritage landscapes can be identified by anyone and do not have legislation determining how they will be protected. Built heritage values, which are a component of cultural heritage landscapes, are protected by the Ontario Heritage Act, but at the writing of this Guide, the details are still being developed for Crown land.

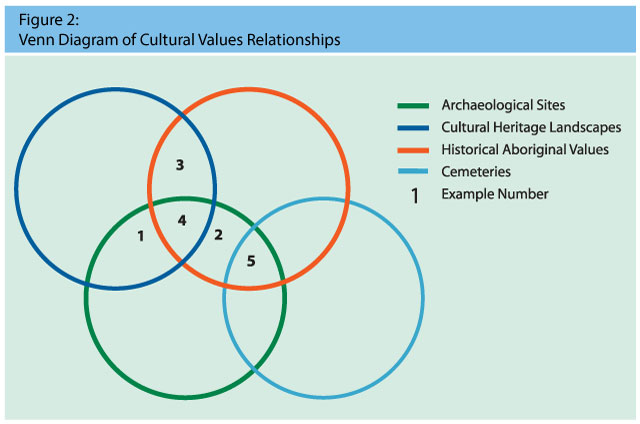

Figure 2: Venn diagram of cultural values relationships

The Venn Diagram in Figure 2 shows how a specific value, for example a fur trade post, could belong to two or three value classes.

This diagram illustrates how individual values may be described as belonging to more than one class. The overlap of values between classes is an important consideration in determining consultation requirements and developing protection measures. Other overlaps are possible (e.g. a cemetery may be part of a cultural heritage landscape.)

Five examples of cultural heritage values are placed within the Venn diagram to illustrate how specific sites may occupy a position within more than one values class.

Example 1: both a cultural heritage landscape, such as a nineteenth century farm community, and associated registered archaeological sites containing the remains of the farm house.

Example 2: a pictograph site might be identified as a historical Aboriginal value, as well as being registered as an archaeological site.

Example 3: a significant spiritual location identified as a historical Aboriginal value, which also appears as a nationally renowned work of art, is therefore a cultural heritage landscape.

Example 4: an early road (i.e. cultural heritage landscape) might follow a traditional Aboriginal peoples’ travel route and be associated with a number of registered archaeological sites.

Example 5: an Aboriginal peoples cemetery that is also a registered archaeological site and also is under the jurisdiction of the Cemeteries Act.

1.4.1 Archaeological sites

Regulations to the Ontario Heritage Act define archaeological sites as: any property that contains an artifact or any other physical evidence of past human use or activity that is of cultural heritage value or interest.

Sites are, therefore, defined on the basis of the presence of physical traces of past occupation. Specifically, artifacts are defined in the regulations as: any object, material or substance that is made, modified, used, deposited or affected by human action and is of cultural heritage value or interest.

Figure 3: Archaeological site

Archaeological sites generally have artifacts found only in the soil.

Figure 3 shows an archaeological site that is being excavated. Archaeological sites are found through the discovery of artifacts either on the surface of disturbed soil (e.g. beaches) or through excavation. For the purpose of this Guide, archaeological sites are defined as archaeological sites or marine archaeological sites registered with the Ontario Ministry of Culture. It is assumed that Ontario Ministry of Culture data is sufficiently accurate to support forest management planning and forest operations. All registered sites have a centre point. Sites that have been investigated in more detail will have established boundaries. The established boundaries will be found in the registration document or the associated report.

1.4.2 Archaeological potential areas

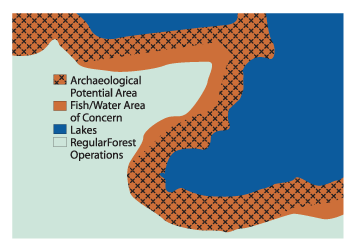

Archaeological potential areas are determined through the use of an archaeological potential area modelling tool. An example of a map showing the tool’s output is found in Figure 4. Archaeological potential area models identify areas that might contain archaeological sites based on the presence of specific landscape features that resemble the location and site conditions of known sites on the forest management unit.

Figure 4: Archaeological potential areas

Archaeological potential areas that meet the data requirements of the Forest Information Manual are treated as known values in forest management planning.

Figure 5: Cultural heritage landscape

It is important to note that areas not shown as having potential might still have an archaeological site contained within them which, when discovered, would become a known value to be protected from forest management operations.

1.4.3 Cultural heritage landscapes

In this Guide, cultural heritage landscapes include both built heritage (i.e. structures) and larger areas of cultural heritage interest. This operational definition excludes individual registered archaeological sites or historical Aboriginal values, but does allow for cultural heritage landscapes that may be identified based on groupings of these values, or combinations of archaeological or historical Aboriginal values with other cultural landscape attributes. A cultural heritage landscape is a defined geographical area which has been modified by human activities and is valued by a community. Individual buildings, structures or travel routes (among other things) represent individual cultural heritage landscape features. Where these also occur in combination and/or along with archaeological sites, historical Aboriginal values, and cemeteries require treatment as one cultural heritage landscape value polygon. It is also common for discrete values to be nested within a cultural heritage landscape. For example, structural remains (e.g. buildings, partial walls or chimneys, stone piles, mining headframes, and wrecks) may be found in association with archaeological values. A cultural heritage landscape is a relatively small polygon area compared to the landscapes referred to in the Forest Management Planning Manual .

Typically, cultural heritage landscape values are grouped according to the cultural mechanism which has brought them into being. Designed landscapes are the result of planned human action, and include town sites, dams, mining sites, and transportation corridors. Evolved landscapes are the result of on-going or past use of the land, and include past forest operations, farm landscapes, and habitations that developed along road or railway corridors. Associate landscapes are those that have not been altered by human use, but have acquired cultural meaning through their connection to a notable person or a nationally renowned work of art. For the purpose of this Guide, cultural heritage landscapes are subdivided by whether they are mapped as points (e.g. buildings and wrecks), lines (e.g. roads and railway beds) or polygons (e.g. logging camp and abandoned townsite). The Ontario Heritage Act, Regulation 9/06 identifies criteria to be used in determining cultural heritage value or interest of built heritage values and cultural heritage landscapes. Under this Guide protection measures are provided for all of cultural heritage landscapes, but these criteria should assist in deciding when an expert is needed to help determine the protection needs. The defined area has design value or physical value because it, is rare, unique, representative or an early example of a style, type, expression, material, or construction method, displays a high degree of craftsmanship or artistic merit, or demonstrates a high degree of technical or scientific achievement.

The defined area has historical value or associative value because it, has direct associations with a theme, event, belief, person, activity, organization, or institution that is significant to a community yields, or has the potential to yield, information that contributes to an understanding of a community or culture, or demonstrates or reflects the work or ideas of an architect, artist, builder, designer, or theorist who is significant to a community. The defined area has contextual value because it is, important in defining, maintaining, or supporting the character of an area, physically, functionally, visually, or historically linked to its surroundings, or a landmark.

Figure 6: Historical Aboriginal value

1.4.4 Historical Aboriginal values

The Forest Management Planning Manual describes the requirement for the collection and consideration of Aboriginal values information to be considered in the preparation of forest management plans. Table 1 has a number of strategies to help OMNR and forest company staff identify and protect Aboriginal values in a manner that should help all parties understand each others concerns better. Members of the planning team and other involved OMNR staff will work in collaboration with participating Aboriginal communities to ensure that the objectives, scope, methodology and end use for data collected are agreed upon and documented. Methods used in gathering and collecting data should be decided with the Aboriginal community’s input. It is also vital that the planning team recognize the importance of working with Aboriginal communities to obtain the best possible data from the correct source and that there may be capacity issues for Aboriginal communities to participate.

Table 1: Best management practices for Aboriginal values identification

The approach for values identification must be established with each of the participating Aboriginal communities. The following strategies might prove effective in the identification and protection of Aboriginal values:

- Determine if there is an existing consultation policy at the local or regional level that will form the basis for this process;

- Remember that the relocation of some Aboriginal communities means that they are now located a distance from their original site. Many Aboriginal communities will be interested in participating in areas where their community was historically;

- Provide advance notice of the planning schedule and interest in Aboriginal values.

- Propose a timeframe for discussion;

- Work towards building long-term and continuous relationships with the community.

- Recognize that good relations will result in more comprehensive values data; this is of benefit to the OMNR, the forest industry, and the Aboriginal community;

- It may be helpful to have agreement with Chief and Council as to how the values collection and protection work will be done (e.g. who, when, and resources available);

- The establishment of an Aboriginal Advisory Committee as a sub-committee of the forest management planning team might be helpful. It would be comprised of members from participating Aboriginal communities;

- Recognize that a number of shorter community visits to discuss a specific item will build better relationships and yield better information than one or two “road show” type community visits. Visits can be timed to coincide with community events where a larger number of members are present;

- Recognize that multiple requests for values information might be made to the communities. MNR should try to coordinate requests from varying program areas;

- Develop strategies with the community to assist them in responding to requests for values data to other government initiatives;

- Develop a data loan or memorandum of understanding with the community. Establish a protocol for ensuring the security of classified data;

- Understand that few communities have the capacity to provide “plan-ready” data, so have a strategy in place to deal with this issue. As with all values, Aboriginal values may be identified at any time;

- Values that were identified during a previous plan term might now have more information available;

- Previous forestry issues and other issues beyond the scope of the Forest Management Plan (FMP) might be brought into the discussion. Discuss with the community whether to gather values at the community, family and/or individual level(s). Often traditional land use within a traditional territory follows clan or family lines; therefore, the local knowledge for many areas might be found within families;

- Skilled interpreters are needed in data collection to ensure that the values presented in the

- Aboriginal language are not lost in translation;

- Values, interests, historic uses, and rights are inseparable to many Aboriginal communities.

- Ensure that issues outside of the scope of forest management are referred to the appropriate

- OMNR staff person to discuss further with the Aboriginal community;

- Due to cultural tradition, some values, for example medicinal plants, may not be identified even to other community members despite their importance;

- Some Aboriginal values might have been lost from the collective memory of an Aboriginal community, for example, if they were not passed on by an Elder. The discovery of an artifact might be the only way that this missing piece of memory is retrieved;

- Remain aware that point values often represent one set of cultural activities nested within a larger area representing a related set of cultural activities. For example, the area surrounding a ceremonial site that is described as supporting the ceremonial action should be considered as part of the value;

- Endeavour to understand the value and all that it entails. This understanding will help in the determination of the appropriate protection requirements for it;

- Levels and approaches to values protection proposed for particular classes of cultural heritage values should be developed in cooperation with the Aboriginal community or individual reporting the value; and

- Field examinations to locate values and establish Aboriginal values site boundaries should be conducted by a person designated by the community (e.g. Elder or person reporting value).

The Aboriginal Background Information Report, as required by the Forest Management Planning Manual, includes an Aboriginal values map which identifies values of importance to the participating community including historical Aboriginal values. These sites might include those of local archaeological, historical, religious, and cultural heritage significance (e.g. Aboriginal cemeteries, spiritual sites, and burial sites.)

Aboriginal values are important. However, only historical Aboriginal values are addressed by this Guide. Other Aboriginal values may be addressed through other guides or even perhaps through the forest management planning process. Some Aboriginal values are best addressed in the forest management planning process when the planning team is deciding on the long term management direction and landscape level matters concerning access and landscape pattern development. Other Aboriginal values may be addressed by other forest management guides such as those dealing with culturally significant species and their habitat (e.g. eagle nests). Therefore, for the purpose of this Guide, historical Aboriginal values are those which can be mapped and fit the cultural heritage definition in Section 1.2. Nevertheless, it is important to recognize from the outset that the range of historical Aboriginal values and interests can be diverse and interconnected and need not contain physical remains (as discussed in the caption for Figure 6). When these values are outside of the scope of this Guide, it is important that they are identified to the appropriate OMNR staff person so that they can further discuss them with the Aboriginal community.

Historical Aboriginal values may be point, line or polygon values. In rare cases, there will be times when historical Aboriginal values will be described in general terms at the start of planning, with the understanding that additional detail about the values will be provided at the annual work schedule stage so that specific protection measures can be determined and amended to the forest management plan for implementation.

Figure 7: Cemetery

The Aboriginal language used in describing the value might convey a level of subtlety or cultural meaning that is absent in an English translation of the terms used. Traditional geographic names within the forest management unit might also provide insight into historical Aboriginal values.

1.4.5 Cemeteries

Burial sites and cemeteries are locations where human remains have been interred, usually accompanied by attendant ritual or ceremony at the time of burial. The Cemeteries Act distinguishes between cemeteries and burial sites. A cemetery is land set aside to be used for the interment of human remains. A registered or approved cemetery is one which has been approved for use by the Registrar of Cemeteries.

A burial site is defined as land containing human remains that has not been approved or consented to as a cemetery in accordance with legislation. As a consequence of the investigation process described in the Cemeteries Act there may be approved cemeteries, unapproved cemeteries, or irregular burials within a forest management unit. For the purpose of this forest management guide cemeteries and burial sites are both referred to as cemeteries.

Not many registered cemeteries are present on Crown lands; however, abandoned cemeteries associated with early settlements, Aboriginal cemeteries, and burial sites should be expected on all forest management units.

Cemeteries may be accompanied by a range of markers (Figure 7 showing two types) that identify the location of individual interments, the boundaries of the site or serve other related functions. According to the Cemeteries Act, “marker means any monument, tombstone, plaque, headstone, cornerstone, or other structure or ornament affixed to or intended to be affixed to a burial lot, mausoleum crypt, columbarium niche or other structure or place intended for the deposit of human remains”, and is integral to the cemetery.

2.0 Cultural heritage values data

The protection of cultural heritage values begins with the development of comprehensive datasets. Developing the necessary datasets will be an on-going task since few complete datasets currently exist. It is expected that there will be more and better quality information for each successive forest management plan.

As data for each of the five classes of cultural heritage values are compiled, it is necessary to review them for completeness and accuracy, identifying gaps in the available data, noting specific issues surrounding classified data, and providing the data for incorporation into the forest management plan (FMP). Since some of this data is provided by agencies other than Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR), it is important that data requirements and FMP timelines are communicated to those agencies providing information (e.g. Ontario Ministry of Culture) at the start of planning. The roles and responsibilities for identifying and confirming the values information by the various parties are described for each values class.

Appendices II and III describe when data are collected and assessed and by who during the forest management planning process.

2.1 Data sources

Sources for data to build a comprehensive cultural heritage values inventory are diverse; however, OMNR is not the principal custodian for much of this data. For example, registered archaeological site records are maintained by Ontario Ministry of Culture and historical Aboriginal values information resides with the Aboriginal community or individuals. Some data can be gathered from primary and secondary historical sources as part of the assembly of background information by OMNR, although developing comprehensive data in this way represents a long-term project. Table 2 identifies sources for data on cultural heritage values.

New values identified during plan implementation will be added to the database.

2.1.1 Archaeological site data

Ontario Ministry of Culture maintains a database of registered archaeological sites. Data for any given management unit is to be provided to the OMNR prior to the start of planning in support of site protection and archaeological potential area modelling.

Table 2: Some sources of cultural heritage values

Converted to list for accessibility

Ontario Ministry of Culture

- Ontario archaeological sites database,

- unverified site files, and

- archaeological fieldwork reports.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources / Sustainable forest licence holders 19

- archaeological potential area mapping,

- FMP related archaeological assessment reports,

- district Sensitive Area files,

- Crown Land Use Atlas,

- old forest management maps, records, and reports,

- district cultural heritage information in the Natural Resource Values Information System;

- Ontario Parks – park management plan background studies, park libraries and archives,

- information from district or company staff and local citizen committee members, and

- old forest inventory and topographic maps, and aerial photos.

Aboriginal communities

- Aboriginal values mapping (e.g. Aboriginal Background Information Report), and

- Aboriginal community consultations, individual or family interviews.

Other sources

- primary and secondary historical sources (e.g. books, journals, maps, and atlases),

- original Crown survey maps and notes,

- Ontario Bureau of Mines Reports,

- Ontario Ministry of Northern Development and Mines

- closed/abandoned mines database,

- community museum societies, historical societies, local historians or residents, Women’s Institutes, etc., and

- internet .

2.1.2 Archaeological potential area data

The archaeological potential area data is provided by OMNR. The archaeological potential area maps are developed using a variety of geospatial map layers as base data for modelling, and includes consideration of both the Ontario Ministry of Culture registered site information and the available cultural heritage landscapes and historical Aboriginal values data as the basis for calibrating the model. The methodology OMNR currently uses in developing the final archaeological potential area maps is described in more detail in Appendix I. There is a role for the FMP team in this process.

2.1.3 Cultural heritage landscapes data

There are few formally defined cultural heritage landscapes in central and northern Ontario, and no comprehensive planning databases for cultural heritage landscapes are available. Some information sources have been assembled under the Ontario

Heritage Properties Database which is available via the Ontario Ministry of Culture’s web site. This database lists properties designated at the municipal level under the Ontario Heritage Act, properties that are owned, protected or recognized by the Ontario Heritage Trust, and other formally recognized properties (e.g. the Ontario Heritage Bridge List and National Historic Sites.) It should not be regarded as a comprehensive list. Additional cultural heritage landscape data might be derived from primary and secondary historical sources: books, journals, maps, and atlases. Forest company and OMNR (including Ontario Parks) records might also contain information on important cultural heritage landscape values, such as early logging camps. Local organizations, such as heritage societies and community museums or individuals, might also have information. Generally, no one owns the data, but it is stored by the OMNR.

2.1.4 Historical Aboriginal values data

Aboriginal Background Information Reports include a values map showing Aboriginal values and therefore is the key source of the historical Aboriginal values data pertinent to this Guide. Historical Aboriginal values that are provided must be considered in the planning process. The OMNR planning team member assigned the role of contact with Aboriginal communities will likely be the primary contact for this data. Although historical Aboriginal values data can be submitted at any time, the earlier that such data are provided in the planning process the better, to ensure consideration during the development of the plan. OMNR can work with Aboriginal communities to ensure the data collection and documentation are in a form easily utilized in the forest management planning process.

2.1.5 Cemetery data

Cemetery data can be compiled from three sources:

- Information on registered cemeteries, including unapproved cemeteries within the forest management unit may be obtained from the Registrar of Cemeteries of the Ministry of Consumer and Business Services. The Cemeteries Regulation Unit maintains a database of registered cemeteries. This information may also include incomplete records or reports of other unapproved cemeteries that are located on Crown land.

- Local information from individuals, Aboriginal communities, historical societies, and other groups with historic connections to areas within the forest management unit.

- Early land records and surveys may provide indications of where cemeteries are located.

2.2 Classified information

OMNR is responsible to ensure that classified data (i.e. sensitive) are protected, secure, and managed in accordance with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources Policy for the Management of Classified Data in the Ontario Land Information Warehouse (in preparation). Classified data are only to be made available for specific purposes to specific people on a need to know basis. OMNR should also determine if additional data loan/sharing agreements are needed to cover information provided from other sources such as an Aboriginal community.

The OMNR district staff person who has access to cultural heritage values data should review all proposed forest management activities during the preparation of the forest management plan and any plan amendments to ensure that the values in areas of operations are protected.

The specific locations of classified values are not to be shown on the public versions of maps used for forest management purposes. Documented protection measures for classified values must be done in such a manner as to not disclose the value.

2.2.1 Archaeological sites

Ontario Ministry of Culture is the custodian for all registered archaeological site data and therefore sets conditions to access this data. Archaeological sites are classified data.

2.2.2 Archaeological potential areas

Archaeological potential areas are not considered classified information even though unknown classified sites might be contained within their boundaries. Archaeological potential areas are required to be shown on values maps and on maps showing proposed forest management activities.

2.2.3 Cultural heritage landscapes

Most cultural heritage landscape data is unclassified, although occasionally a cultural heritage landscape may be classified due to specific classified values found within it. Locations for individual structures, such as buildings or constructed landmarks might be highly susceptible to damage and should be considered classified information. For example, colonization roads might be associated with known classified sites; therefore, sections of the colonization road may also be considered as classified information. Determining whether a cultural heritage landscape should be considered as classified must be done on an individual basis.

2.2.4 Historical Aboriginal values

All historical Aboriginal values information is owned by the Aboriginal community that provides it. The data are considered classified unless indicated otherwise by the Aboriginal community. Therefore, the information will not be shared within anyone other than the persons indicated in a data loan agreement or memorandum of understanding between the Aboriginal community and the OMNR district. These agreements should include:

- term of the agreement;

- description of the data being loaned or shared, its format, etc.;

- contact names for OMNR and the community;

- who has access to the data (e.g. other OMNR program areas to avoid more requests for the same information);

- how data will be protected and used, including specific provisions for

- Aboriginal community participation in the field lay out of areas of concern;

- how to proceed if a value cannot be located in the field; and

- proper instruction of field staff regarding the values.

2.2.5 Cemeteries

Records of registered cemeteries are on file with both the landowner and the Registrar of Cemeteries and therefore are public records. Cemetery locations are not considered classified and should be shown on values maps and maps showing proposed forest operations.

2.3 Data standards

The Forest Information Manual identifies the criteria that values data are required to meet in order to be considered known values for the purposes of forest management planning. For a value to be considered a known value, sufficient information must be available to describe its geographic location and basic features. Data which do not meet the standards of the Forest Information Manual are not considered as known values for the purpose of planning. In such cases, the OMNR will ask the provider for the necessary information. The basic description information required for known values includes: identification of the value by class or category (sub-class), information source, accurate location, description of the physical characteristics of the site, and any other specific information required to decide on the appropriate protection.

2.4 Identifying values and ensuring location accuracy

The Forest Information Manual describes the process for identifying and confirming values. It is expected the current terminology of confirmation and verification will change once the new Forest Information Manual comes into effect (expected spring 2007). The terminology and responsibilities described in the Forest Information Manual take precedence over the explanation included in this Guide.

At the time of preparing this Guide, the term confirm describes the roles and responsibilities of the data provider. The provider of values information must confirm that information provided is accurate and meets the standards described in the Forest Information Manual. Verify describes the roles and responsibilities of the receiver (i.e. generally for this Guide, the sustainable forest licence holder). The receiver of values information must verify that the information received is accurate and conforms to the Forest Information Manual.

2.4.1 Archaeological sites

For archaeological sites, no confirmation or verification is necessary. However, there might be times when the receiver of the information wishes to do more investigation.

2.4.2 Archaeological potential areas

OMNR is responsible for confirming archaeological potential area maps. Confirming archaeological potential areas includes analysis to ensure that the modelling output conforms to the base landscape data and assumptions of the model calibration. Additional information, detailed mapping, photography, and descriptions provided by field staff familiar with the area, can assist in identifying areas that do not conform to the definition of potential. Confirmation does not determine the presence or absence of archaeological site locations within the potential areas, since this is part of the archaeological assessment.

Appendix I provides detailed information on the confirmation of potential modelling results.

Verification, when necessary, is the responsibility of the receiver of the information and must be completed by a licensed archaeologist. Verification may be completed as an archaeological assessment when the objective is to document archaeological sites within the area of concern.

2.4.3 Cultural heritage landscapes

OMNR is responsible for confirming any cultural heritage landscapes data. Cultural heritage landscape values verification does not need to be completed as archaeological assessments. However, certain cultural heritage landscape values could require investigation by a specialist (e.g. buildings and cultural heritage landscape level features that might be associated with archaeological sites).

If a value cannot be located because of insufficient positional accuracy, the OMNR district should be contacted per the Forest Information Manual. If after further checking the site still cannot be found regular operations can proceed, with a provision to stop operations if the value becomes evident.

Where the data provided by OMNR are from an outside party, that party is responsible for confirming and documenting that the data provided meets Forest Information Manual data standards. As cultural heritage landscapes are identified, the information should be reviewed to determine whether they have been described in sufficient detail to meet the data requirements of the Forest Information Manual and can be considered as known values for the purpose of forest management planning. The most effective method for confirming the values is through additional discussion and review of detailed mapping of the value with the provider. In addition, the information received should be reviewed by the planning team to determine whether there is sufficient information to allow specific protection measure(s) for the value to be developed, or, if this information is not immediately available, whether it can be readily obtained.

2.4.4 Historical Aboriginal values

Verification of historical Aboriginal values is usually done as part of the discussions with the participating Aboriginal community and with the active participation of the qualified individual as identified by the Aboriginal community (see Section 3.0). The Aboriginal community may wish to document boundaries or the core areas of the value and/or evaluate the significance and sensitivity of the value to help determine the protection needed. Those involved in the process will decide on a timeline for this that will fit with the schedule for preparing the forest management plan.

2.4.5 Cemeteries

Cemetery data from the Registrar of Cemeteries do not need to be confirmed or verified. If during forest operations it becomes apparent that the cemetery location is incorrect then the proper location must be protected.Where the data provided to OMNR are from a party other than the Registrar of Cemeteries, that party is responsible for confirming and documenting that the data provided meet Forest Information Manual data standards or are sufficient for planning.

3.0 Protection of cultural heritage values

The principal focus for the protection of cultural heritage values should be to prevent or minimize physical damage to values through planning of reserves and modified operations. Indirect impacts, such as changes in visibility or accessibility of values as a result of operations, also need to be considered in the planning of operations. Other forest management guides deal with forest site damage issues, such as mitigating against potential soil erosion and rutting. Besides the negative effects to forest health, site disturbance can also damage or destroy cultural heritage values.

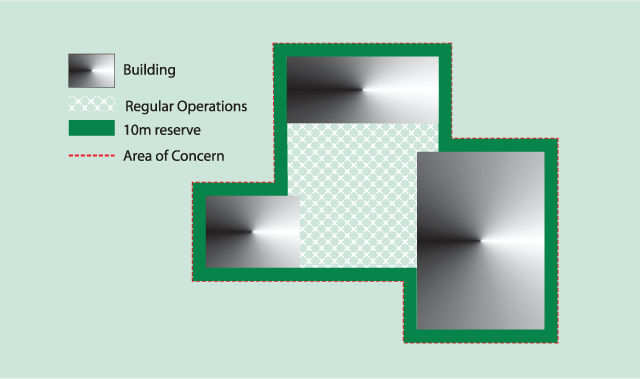

For those values for which specific protection measure(s) are given in this guide and the protection measure(s) are used in the forest management plan, a qualified individual will normally not need to be involved. Archaeological sites and archaeological potential areas must be protected per Ontario Ministry of Culture requirements. Therefore the Guide’s sections that discuss the protection of these areas refer to archaeological assessments. There are four stages of archaeological assessment. Most common for forest management, Stage 2 is conducted to ascertain whether there are any archaeological artifacts within a specific area. A summary of all of the stages can be found in the glossary under Archaeological Assessment. For a full explanation, see the Ontario Ministry of Culture’s current standards and guidelines for consultant archaeologists. Prescriptions for operations in areas of concern are recorded in forest management plans in a table referred to as FMP-14. Appendix IV provides examples of completed

FMP-14 tables based on the standards, guidelines, best management practices, and information presented in this section. Any new cultural heritage values in areas of planned operations identified during plan implementation (e.g. by a member of the public or during forest operations) will be protected as prescribed by this Guide. In the case of a new value being found during forestry operations, work must cease in the area of the find immediately. Section 3.7 gives advice regarding who must be contacted and protection of the value. Usually protection of cultural heritage values is in the form of a reserve or modified operations. There are cases where some values, for example old road beds, do not require an area of concern, but documentation must take place instead. This documentation may be in the form of photographs and notes about the state of the value, what it looks like, what materials make it up, its proximity to other objects in the area, notes of interest, etc. This documentation should be shared with the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) district office and the OMNR provincial cultural heritage specialist.

Standards and guidelines are bolded. Standards are mandatory direction. Guidelines also provide mandatory direction, but require professional judgement to be applied appropriately at the local level. Best management practices, defined as practices at an exemplary level of performance, are also included in this Guide. Forest managers are encouraged to adopt those best management practices that are pertinent to their area.

3.1 Protection –general

The following guidelines and best management practice apply to all five classes of cultural heritage values.

Guidelines

- Marking the area of concern boundaries of classified sites must not draw attention to the purpose for which the area of concern is established (e.g. use the same flagging tape as for other nearby areas of concern).

- In developing protection measures,

- be aware that a value might belong to more than one value class, (e.g. a historical Aboriginal Value that is also an archaeological site as in Figure 8 or the archaeological component of a cultural heritage landscape.) In such cases, the protection strategies for the other value class(es) must also be

- applied and more than one qualified individual might need to be involved.

- There will be consideration of visual aesthetics, which may include the use of viewscape analysis techniques, in the development of the protection measure(s) where mature forest is integral and adds further meaning to the value (e.g. where a view at the location forms a nationally renowned work of art, provides context for the actions of a well known historical figure, or is integral to contemporary use of a traditional spiritual site.)

Figure 8: Value belonging to two value classes

Best management practice

- Sometimes the layout of the harvest area can be altered to avoid a cultural heritage area (e.g. leaving a cultural heritage to meet direction provided in another Guide).

3.2 Archaeological sites

The planning team may choose to accept the Ontario Ministry of Culture’s archaeological site data and apply the reserve dimensions in the standards. Alternately a licensed archaeologist can be hired to:

- review additional information which might be available in the Ontario Ministry of Culture archaeological site registration forms and published and unpublished archaeological reports; and/or

- conduct an archaeological assessment as prescribed by the Ontario Ministry of Culture.

This is outlined in some of the following standards and in Figure 9.

In any case where an archaeologist has made a recommendation for protection of the site, the supporting report must be sent to and reviewed by Ontario Ministry of Culture staff. Archaeologists recommendations will normally be followed, at a minimum, since they are made to ensure their clients’ projects comply with the Ontario Heritage Act.

The following standards, guideline, and best management practice apply to archaeological sites.

Standards

- The reserve must extend at least 200 metres from the defined centre of the site unless:

- the boundary of a site has been delineated through a Ontario Ministry of Culture Stage 3 archaeological assessment, in which case the reserve is a minimum of 10 metres from the boundary; or

- a Stage 4 excavation has been completed to meet Ontario Ministry of Culture standards and a recommendation has been made by a licensed archaeologist that no further archaeological work is required in which case a reserve is no longer required; or

- the sustainable forest licence holder chooses to engage a licensed archaeologist to collect and report on information from the Ontario Ministry of Culture. Then one of the following three situations could occur:

- If the review suggests that the archaeological site is possibly large or has great cultural heritage value or interest, then keeping the 200 metre radius reserve or creating a larger reserve will likely be recommended. An Ontario Ministry of Culture archaeological assessment can be done to establish the boundaries of the site and from this, a 10m buffer can be established from the boundary.

- If the review suggests that the site is small or registers the location of an isolated find (e.g. arrowhead), and this conclusion is supported by documentation such as field notes, a report, or the results of an archaeological assessment, then the archaeologist could make a recommendation to remove the reserve since it does not provide protection of a tangible material resource.

- If the review shows that the site is of another class of cultural heritage value for which direction is provided in this Guide (e.g. cabin), then the archaeologist could make a recommendation to substitute more appropriate protection.

- The following are not permitted within archaeological site reserves:

- harvest, renewal and tending activities,

- new roads, landings, or water crossings.

- Maintenance and use of existing roads is permitted.

Figure 9: Key for alternative protection possibilities for archaeological sites

- Receive registered archaeological site data from Ontario Ministry of Culture.

- Accept data and protect with prescription as required by standards in the Guide.

- Hire an archaeologist to do a Stage 3 and/or Stage 4 archaeolgical assessment.

- Hire a licensed archaeologist to contact Ontario Ministry of Culture for site forms and reports.

- Archaeological Site.

- Established boundary-10m reserve.

- Non-established boundary -200m reserve or larger dependingon site

- Building or other above ground built feature (e.g. retired aircraft land strip).

- If no further investigation, then evaluation by qualified individual.

- If further investigation previously and boundaries determined, then use appropriate protection.

- Isolated archaeological find (e.g. lone arrowhead).

- If no further investigation previously, then a Ministry of Culture Stage 2 is done.

- If nothing found - no protection required. Document work in FMP.

- If more archaeological features found - protect as recommended by licensed archaeologist.

- If further investigation previously, then no protection required. Document.

- If no further investigation previously, then a Ministry of Culture Stage 2 is done.

- Archaeological Site.

Download Figure 9: Key for alternative protection possibilities for archaeological sites (PDF)

When a licensed archaeologist is hired to review additional information which might be available in the Ontario Ministry of Culture’s archaeological site registration forms and reports, then there are several possible outcomes. These possibilities are summarized in this figure and discussed further on pages 29 and 31.

Guideline

- Data that indicate that a site has greater cultural heritage value or interest will require individual protection measure(s) based on specific site features. The protection measure(s) will be determined through discussions among Ontario Ministry of Culture staff and OMNR’s provincial cultural heritage specialist. In those cases where a licensed archaeologist found the site while working for the sustainable forest license holder, they will also be engaged in the discussions.

Best management practice

- Reserve dimensions should be increased if there is an identified risk of:

- archaeological site disturbance resulting from windthrow of residual trees; or

- increased access to the archaeological site.

3.3 Archaeological potential areas

Archaeological potential areas are identified since their characteristics (e.g. soil, topography) indicate there is a higher probability that an archaeological site(s) exists within in them. Therefore, the top 30 cm of mineral soil must be protected since most archaeological sites contain subsurface features lying within this depth. Protection of archeological potential areas centres on the ability to minimize mineral soil disturbance while conducting forest operations.

For the purpose of this Guide, mineral soil disturbance is defined as mineral soil displacement through excavation, rutting, and mixing by equipment used in forest operations. Mineral soil exposure, through the displacement of the organic soil layer, is not considered to be mineral soil disturbance.

Where there will be mineral soil disturbance above the threshold described in the standards and guidelines then an archaeological assessment is required. As described in the Forest Information Manual, archaeological assessment is the responsibility of the sustainable forest licence holder.

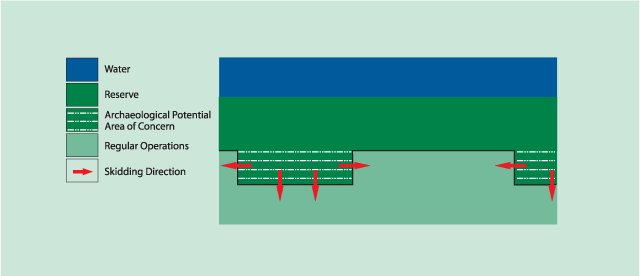

Figure 10: Distinct symbology for archaeological potential areas of concern

It is important that archaeological potential areas of concern are distinct from overlapping areas of concern for other values (e.g. fish habitat and water quality) since the type of operations that can occur will most likely differ.

Assessment reports completed by a licensed archaeologist engaged by a sustainable forest licence holder must meet Ontario Ministry of Culture reporting requirements. Appendix V describes how the Ontario Ministry of Culture reporting requirements should be met in the Crown land forestry context. The Ontario Ministry of Culture has identified that archaeological assessment reports may contain classified information about archaeological site values on Crown land. Therefore, a summary list of completed archaeological assessments should be filed with the forest management plan (FMP). Archaeological assessment reports represent work completed during the preparation of the forest management plan (FMP). Therefore, copies of the reports must be provided to the OMNR district and provincial cultural heritage specialist.

The OMNR determines the archaeological potential area by running a predictive model for the management unit. Appendix I gives background information about the model that is currently used by OMNR . The model was developed to replace the Ontario Ministry of Culture’s Checklist for Determining Archaeological Potential which was developed for smaller parcels of land and therefore is not well suited for the forestry context. Planning teams can choose which they prefer to use. Section 2.4.2 discusses the confirmation and verification process.

The archaeological potential area, as mapped by the archaeological potential model or the Ontario Ministry of Culture’s Checklist for Determining Archaeological Potential, is the area of concern. Areas of concern for archaeological potential areas must be distinguished from other overlapping areas of concern on the areas selected for operations maps, such as through the use of a distinct symbology (e.g. dashes or hatching as shown in Figure 10).

The following standards, guidelines, and best management practices apply to archaeological potential areas.

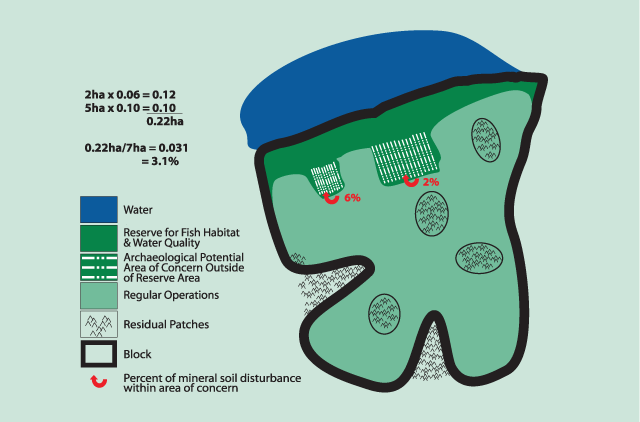

Figure 11: Disturbance of mineral soil within archaeological potential areas of concern

Although there is 6% mineral soil disturbance in one part of the archaeological potential area of concern, the other part of the area of concern (in the same block) only has 2%. As a weighted average this is 3.1%. Since this is less than 5% for this block the block is in compliance.

Standards

Within the archaeological potential area one of the following must occur:

- there is a reserve equivalent to the dimensions of the area of concern;

- regular operations following Ontario Ministry of Culture’s Stage 2 archaeological assessment where nothing has been found, the recommendation is that no further archaeological work is required, and the Ontario Ministry of Culture has reviewed the report;

- operations where the harvest, skidding, and renewal activities do not cause more than 5% mineral soil disturbance (on a weighted average basis) within the harvested portion of the archaeological potential area of concern within the block, as shown in Figure 11; and/or,