Hoptree Borer Recovery Strategy

Read the recovery strategy for the Hoptree Borer, an insect species at risk in Ontario.

Cover photo by Jean-Francois Landry

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Harris, A.G. 2018. Recovery Strategy for the Hoptree Borer (Prays atomocella) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, Peterborough, Ontario. iv + 19 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2018

ISBN 978-1-4868-2776-3 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4868-2777-0 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Authors

Allan Harris - Northern Bioscience

Acknowledgments

David Beadle, Tammy Dobbie (Parks Canada) and Chris Schmidt (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) provided background information. Jay Cossey supplied details on a Point Pelee sighting. Jason J. Dombroskie (Cornell University), Mike Burrell (NHIC) and Don Sutherland (NHIC) provided details on their 2016 survey at Pelee Island. Jean-François Landry (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) supplied the cover photograph.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Hoptree Borer was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The recommended goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Parks Canada Agency

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service

Executive summary

Hoptree Borer (Prays atomocella) is a small but distinctively patterned moth. Its known Ontario range is confined to Point Pelee National Park and Pelee Island, in association with its larval host plant, Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata). Hoptree Borer is classified as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007. Common Hoptree, the host species, is classified as special concern in Ontario and as threatened under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

Little is known of the life history of Hoptree Borer. Larvae bore into the twigs of Common Hoptree, creating a cavity in the woody stem. Larvae feed on leaves and other plant tissue until late summer or fall and probably overwinter in the cavity. The following spring, larvae resume feeding until they are ready to pupate when they leave the stem to pupate in a distinctive mesh-like cocoon. Adults emerge shortly thereafter and lay eggs on Common Hoptree shoots. It is unknown if the adults feed.

The most significant threats to Hoptree Borer are those that affect Common Hoptree including shoreline erosion, vegetation succession, invasive non-native plant species and problematic native species.

The recommended recovery goal for Hoptree Borer is to maintain the current distribution of all Ontario populations by (1) protecting, maintaining and restoring habitat, (2) filling knowledge gaps related to threats, species biology and population abundance and (3) mitigating threats.

Proposed recovery activities focus on filling knowledge gaps on Hoptree Borer distribution, abundance and life history and protecting Common Hoptree and its habitat.

Based on the Common Hoptree critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy (Parks Canada Agency 2012) it is recommended that areas for consideration for a habitat regulation for Hoptree Borer include all mapped polygons identified as critical habitat for Common Hoptree where Hoptree Borer are known to be present. For newly identified occurrences of Hoptree Borer (e.g., Burrell and Sutherland, pers. comm. 2018) where critical habitat for Common Hoptree has not been identified, a similar approach is recommended.

The locations and attributes of critical habitat were identified using the best available information on Common Hoptree distribution including observation data on the presence of a single tree or cluster of trees. Where specific point locations were unavailable, the vegetation communities (Ecological Land Classification vegetation types or ecosite polygons) surrounding the Common Hoptree occurrences were identified. Existing infrastructure (including roads, trails, parking lots, utility corridors and buildings), cultivated areas and unnatural vegetation types (e.g., baseball fields, grassed areas and septic beds) are excluded from these areas. Utility corridors and road rights-of-way are also excluded from critical habitat.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

| Assessment | Status |

|---|---|

| SARO List classification | Endangered |

| SARO List history | Endangered (2017) |

| COSEWIC assessment history | Endangered (2015) |

| SARA schedule 1 | No schedule, no status |

| Conservation status rankings |

|

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

The Hoptree Borer is a small, but distinctly patterned moth. The forewings and thorax are white with black dots and the hindwing and abdomen are pinkish or rust coloured. Both wings are fringed with hairs. No other Canadian moths have this distinctive combination of colours. The wingspan is 17 to 20 mm. The larvae are a nondescript pale-green or yellow but have the distinctive habit of boring in Common Hoptree shoots. Mature larvae are 20 mm long (COSEWIC 2015a).

A DNA barcode is publicly available for this species from a Canadian specimen (bold sequence ID: LPSOD1057-09.COI-5P) (Ratnasingham and Hebert 2007).

Species biology

Hoptree Borer is dependent on its host plant, Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata), but its life cycle is poorly known. The duration of the egg, larval and adult stage are not precisely known, nor has the egg and egg-laying behaviour been described (COSEWIC 2015a). The following is largely inferred from observations of Hoptree Borer and other closely related species in the United States (US).

In the US, adults are active from mid- to late June, and lay their eggs on the leaves or shoots of Common Hoptree (COSEWIC 2015a). The eggs hatch shortly thereafter and the larvae bore into a young shoot, creating a cavity in the woody stem. Inside the cavity they construct a silk tube as a protection from predators and parasites. Larvae feed on leaves and other plant tissue until late summer or fall and probably overwinter in the cavity (COSEWIC 2015a). The following spring, larvae resume feeding until they are ready to pupate when they leave the stem to pupate in a distinctive mesh-like cocoon, often among the host plant flower clusters. There is one generation per year (COSEWIC 2015a).

Adult feeding has not been documented, but females of related species, Apple Ermine Moth (Yponomeuta malinellus) require nectar feeding for a week or more before they are sexually mature (Carter 1984).

Dispersal and migration in Hoptree Borer has not been documented but is probably limited by the sporadic distribution of Common Hoptree subpopulations in Ontario (Schmidt pers. comm. 2015).

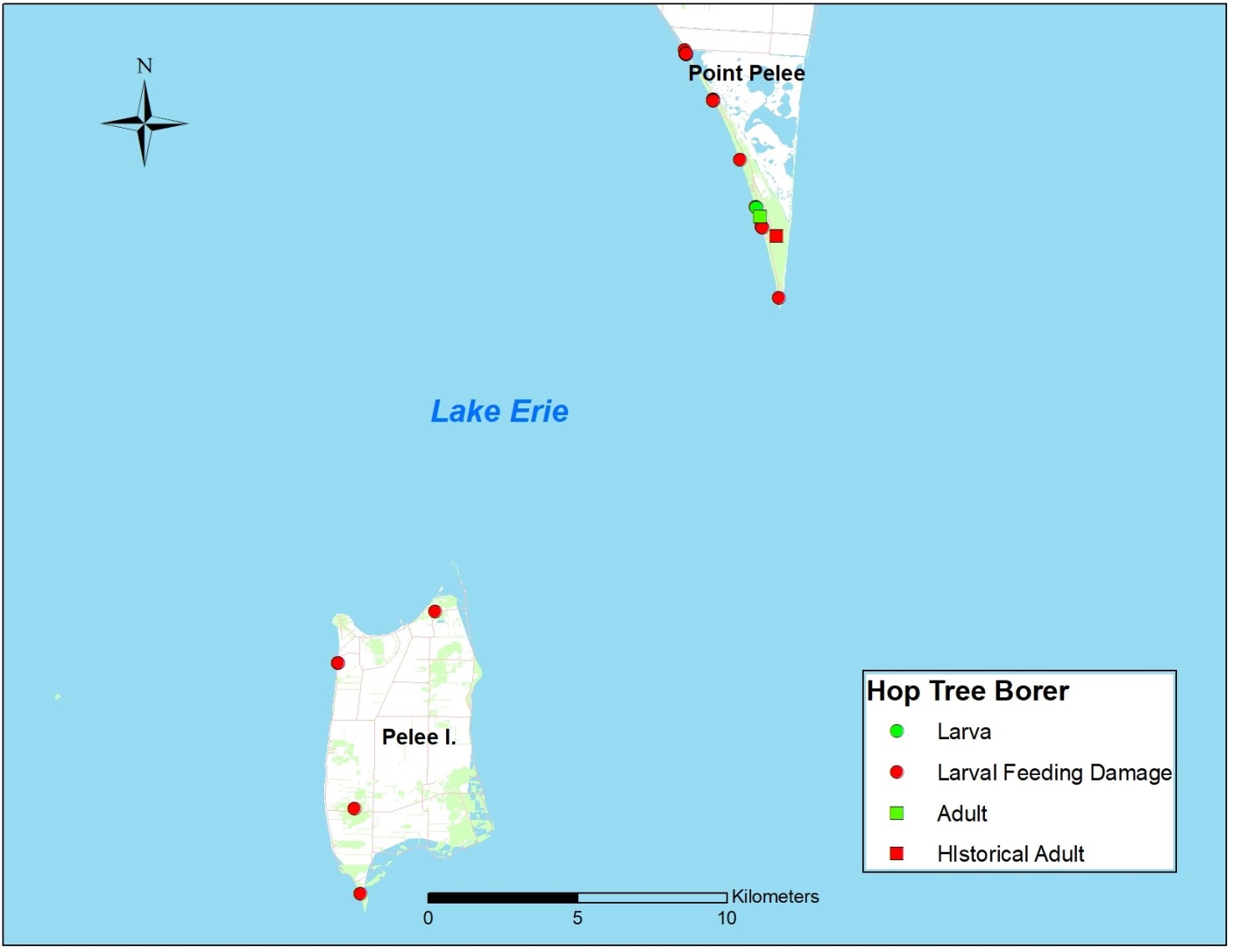

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

The known Canadian range of Hoptree Borer consists of seven confirmed records of adults on the west side of Point Pelee National Park on Lake Erie and of larvae on Pelee Island, about 20 km south of Point Pelee (Figure 1, Table 2) (COSEWIC 2015a). Point Pelee National Park supports over 10,000 mature Common Hoptrees and Pelee Island has over 900 (COSEWIC 2015b). The recent records from Point Pelee are from the West Beach area, but precise locations of older collections are unknown (Table 2). On Pelee Island, Hoptree Borer larvae were found on a shoreline next to a road right-of-way on the west side of the island, on a road right-of-way near the north end of the island, and in Fish Point Nature Reserve on May 31 - June 3 2016 (COSEWIC 2015a, Burrell and Sutherland pers. comm. 2018). Several hundred twigs with feeding damage were observed in 2016 surveys and several larvae were collected. Undiscovered populations may also exist elsewhere in the Ontario range of Common Hoptree, particularly Middle Island in Lake Erie, which is part of Point Pelee National Park. Other scattered sites along the north shore of Lake Erie, and a few inland sites have fewer trees (<100 mature individuals) and are less likely to support the moth (COSEWIC 2015b). Most of the Common Hoptree sites northwest of Point Pelee and in Essex County contain fewer than 10 mature trees (COSEWIC 2015b), and are unlikely to support Hoptree Borer populations.

No abundance or population trend data are available for Hoptree Borer in Ontario. It is known from seven confirmed records at Point Pelee between 1927 and 2013. These include three between 1927 and 1931, and one each from 1981, 2008, 2010 and 2013 (COSEWIC 2015a). In 2010, probable evidence consisting of 84 damaged Common Hoptree shoots was observed at Point Pelee (62) and at Pelee Island (22) (COSEWIC 2015a). More evidence of feeding damage was observed on Pelee Island in 2016 (Burrell and Sutherland pers. comm. 2018).

Although Hoptree Borer population trends are unknown, Common Hoptree populations in Ontario apparently increased between 2002 and 2014 (COSEWIC 2015b). However, it is also known that three small Common Hoptree sites outside Point Pelee National Park were extirpated during that period due to development.

In the US, the species is poorly known, but generally considered to be rare throughout its range (COSEWIC 2015a).

| Date | Location | Life stage | Collector | Depository |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 27 1927 | Point Pelee, ON | Adult, male | F.P. Ide | CNC |

| June 29 1927 | Point Pelee, ON | Adult, female | W.J. Brown | CNC |

| June 23 1931 | Point Pelee, ON | Adult | D.H. Pengelly | DEBU |

| June 11 1981 |

Point Pelee, ON | Adult | D.H. Pengelly | DEBU |

| June 8 2008 | Point Pelee, ON | Adult, DNA barcode voucher #08MZPP-142 | M. Zhang | BIO |

| June 6 2010 | Point Pelee N.P. west shore. Multiple locations | Larval feeding damage | A. Harris and R. Foster | photograph |

| June 6 2010 | Point Pelee N.P., West Beach, ON 41.934 N 82.517 W | Larva [dead], DNA barcode voucher # CNCLEP00076535 | A. Harris and R. Foster | CNC |

| June 21 2013 | Point Pelee N.P., West Beach trail | Adult | J. Cossey | photograph |

| June 5 2010 | Pelee I. NW corner | Larval feeding damage | A. Harris and R. Foster | photograph |

| June 5 2010 | Pelee I. Fish Point | Larval feeding damage | A. Harris and R. Foster | photograph |

| May – June 2016 | Pelee Island, 22 m stretch of Harris-Garno Rd; | Larval feeding damage | M. Burrell and D. Sutherland | NHIC |

| May – June 2016 | NCC property on north side of East West Road | Larval feeding damage | M. Burrell and D. Sutherland | NHIC |

1.4 Habitat needs

Hoptree Borer depends on Common Hoptree, which is intolerant of deep shade and most commonly occurs on the edge of sand beaches adjacent to the forest (COSEWIC 2015b). On Pelee Island, Hoptree Borer larvae occur on Common Hoptrees growing along roadsides as well as on beaches and along a track through a deciduous forest where there were scattered Common Hoptrees (Burrell and Sutherland pers. comm. 2018). Common Hoptree also grows on thin soil over limestone in alvars (COSEWIC 2015b), but Hoptree Borer has not yet been discovered in this habitat.

Common Hoptree habitat at Point Pelee, consists predominantly of three community types: Hoptree Shrub Sand Dune (SBS1-2), Red Cedar Treed Sand Dune (SBTD1-3) and Dry - Fresh Hackberry Deciduous Woodland (WODM4) (Lee et al. 1998; Dougan and Associates 2007). It occasionally occurs in a wide variety of other vegetation types at Point Pelee. Elsewhere in its range, Hoptree Borer occurs on shoreline dunes of Lake Michigan, in cedar glades in Tennessee and Arkansas and along stream banks and shaded slopes in central Texas (Knudson pers. comm. 2009).

The Canadian range of Common Hoptree is largely confined to the Lake Erie shoreline where there is a long growing season and a moderate climate (Crins et al. 2009).

1.5 Limiting factors

Hoptree Borer is dependent on a single host plant, which itself is at risk (special concern) in Ontario with a very limited geographical range and small number of occurrences.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Direct threats to Hoptree Borer are poorly understood given the lack of information on the species’ life history, population size and trends. Threats were organized and evaluated using the IUCN-CMP (World Conservation Union-Conservation Measures Partnership) unified threats classification system (Master et al. 2009) in the COSEWIC status reports for Hoptree Borer and Common Hoptree (COSEWIC 2015a, 2015b). The most significant threats to Hoptree Borer are those that affect Common Hoptree including shoreline erosion, vegetation succession, invasive non-native plant species and problematic native species (COSEWIC 2015a, 2015b, Parks Canada Agency 2012).

Shoreline Erosion

The primary threat to Common Hoptree is loss of beach and dune habitat caused by changes in sand deposition and erosion. Shoreline development on the Lake Erie shore both east and west of the park is trapping sand that formerly would be transported to replenish that lost by erosion. The mineral shoreline shrank by 30.8 ha between 1931 and 2015 and sand barren/dune habitat shrank by 40.4 ha during the same period (S1 Table in Markle et al. 2018). In the next 50 years, up to 126 ha of habitat could be lost from the west side of the park, and this is the area that should be naturally accreting new beach habitat (Parks Canada Agency 2012). Common Hoptree depends on colonizing newly created beach habitat, and under current conditions habitat is not being created fast enough to counter losses due to erosion (COSEWIC 2015b).

Succession

Common Hoptree requires periodic disturbance to maintain early successional habitats in sand dunes, savannas and roadsides. Without disturbance, trees and tall shrubs invade these habitats, which increases shading, suppresses flowering and limits recruitment (COSEWIC 2015b).

Suppression of fire in savanna and alvar habitats has allowed trees to invade some sites, but prescribed burns and other vegetation management at Point Pelee National Park and Stone Road Alvar on Pelee Island are maintaining dune and savanna habitats (COSEWIC 2015b). Vegetation clearing on road rights-of-way on Pelee Island has also maintained open conditions suitable for Common Hoptree.

Ice-scour (shoreline erosions caused by ice movements) along Lake Erie shores also maintains open conditions, but climate change may be reducing the amount of ice cover and resultant scour (Parks Canada Agency 2012).

Storms

Shifts in the timing and severity of storms could have a significant impact on Hoptree Borer adults and larvae. Climate change leads to changes in the frequency, intensity, spatial extent, duration and timing of weather and climate extremes (Seneviratne et al. 2012). Recent severe storms have damaged Common Hoptrees and increased erosion of beach habitat at some sites (COSEWIC 2015a, Parks Canada Agency 2012).

Invasive Non-native Plant Species

Competition with invasive non-native plants is a potential threat to Common Hoptree. Invasive plants are present in nearly all populations of Common Hoptree in Point Pelee National Park. They impair establishment of seedlings but do not kill mature trees (COSEWIC 2015b). The most invasive plants in Common Hoptree habitat at Point Pelee include White Mulberry (Morus alba), Japanese Knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum), White Poplar (Populus alba), Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea maculosa), English Ivy (Hedera helix), Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolaris) and Orange Daylily (Hemerocallis fulva) (Dougan and Associates 2007).

Problematic Native Species

Two native insect species are potential threats to Hoptree Borer through competition and by causing leaf and shoot dieback (death of twigs and branches). Hoptree Leaf-roller Moth (Agonopterix pteleae) outbreaks caused extensive defoliation of Common Hoptree at Point Pelee in 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 (Parks Canada Agency 2012). Extensive feeding damage was observed on Pelee Island in 2014, where smaller trees were frequently completely defoliated (COSEWIC 2015a). Hoptree Barkbeetle (Phloeotribus scabricollis) was observed on several of the Common Hoptree populations in 2000-2002 (COSEWIC 2002), causing dieback, reduced growth and loss of flowers.

While surveys for Hoptree Borer have not been conducted on Middle Island, habitat destruction caused by overabundant Double-crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus) on Middle Island is a potential threat to Common Hoptree (Boutin et al. 2011; Koh et al. 2012; Parks Canada Agency 2012). Cormorants increased from three nests on Middle Island in 1987 to 3,809 in 2009 (Boutin et al. 2011). The accumulation of guano caused tree death, reduced plant species richness, altered soil chemistry and increased the proportion of non-native plants (Boutin et al. 2011, Hebert et al. 2014).

Pesticides

The use of Btk (Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki), a bacteria used to control Gypsy Moth (Lymantria dispar) is a potential threat to Hoptree Borer (COSEWIC 2015a). Btk kills many non-target butterfly and moth larvae and is typically applied in early April to early May, coinciding with the larval stage of Hoptree Borer. Btk is applied by aircraft or by hand-held sprayer on Gypsy Moth infected trees. It is also used on agricultural crops and on gardens (Surgeoner and Farkas 1990). Parks Canada currently does not control Gypsy Moth within Point Pelee National Park (COSEWIC 2015a), but its potential use at Pelee Island could negatively impact this species.

Other Threats

Recreational activities and shoreline development are additional threats to Common Hoptree, but not known to be a factor in Hoptree Borer range (except in the reduction of sand deposition; see Shoreline Erosion). Prescribed burning to maintain alvar and savanna habitat is likely a minor threat to Hoptree Borer, as shoreline plant communities where Common Hoptree subpopulations are concentrated would only be marginally affected (COSEWIC 2015a). Prescribed burning has the potential to improve habitat for Hoptree Borer by maintaining early successional vegetation and better conditons for Common Hoptree (see Succession). Selective trimming of Common Hoptrees occurs along roadsides in Point Pelee National Park. This practice is unlikely to harm Hoptree Borer populations since all known occurrences of larvae are along beaches rather than roads. Trimming competing vegetation helps to maintain Common Hoptree habitat (COSEWIC 2015a).

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Very little is known about the life cycle and basic biology of Hoptree Borer including adult feeding habits, predators, parasites and dispersal capability. The size and trend of Ontario’s population are unknown. No surveys for Hoptree Borer have been completed at Middle Island where there are approximately 550 mature Common Hoptrees (COSEWIC 2015b).

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Since the release of the COSEWIC status report for Hoptree Borer in 2015, additional population surveys were conducted on Pelee Island in 2016 (Burrell and Sutherland pers. comm. 2018).

A federal recovery strategy for Common Hoptree was released in 2012 (Parks Canada Agency 2012). The Ontario recovery strategy (adoption of the federal strategy) was completed in 2013 (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources 2013). Actions already completed include surveys to update Common Hoptree population size and distribution at Point Pelee National Park (and Middle Island and other sites where Hoptree Borer has not been discovered) and communication efforts with property owners and park staff and visitors (Parks Canada Agency 2012). At Point Pelee National Park and Stone Road Alvar on Pelee Island, succession is being actively addressed by prescribed burns and physical removal of encroaching vegetation from savanna and dune habitats to improve growing conditions for Common Hoptree (Parks Canada Agency 2012, 2016). Active management by Parks Canada is taking place to reduce the impacts of hyper-abundant nesting Double-crested Cormorants on Middle Island and over-browsing by White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) at Point Pelee National Park (Parks Canada Agency 2012, 2016). Common Hoptree population enhancement efforts and ecosystem protection have also been implemented at the Walpole Island First Nation since 2007 (Parks Canada Agency 2012).

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recommended recovery goal

The recommended recovery goal for Hoptree Borer is to maintain the current distribution of all Ontario populations by maintaining and protecting habitat, filling knowledge gaps and mitigating threats.

2.2 Recommended protection and recovery objectives

| Number | Protection or recovery objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Protect, maintain and where feasible restore habitat. |

| 2 | Fill knowledge gaps related to threats, species biology and population abundance. |

| 3 | Mitigate threats including pesticide use. |

2.3 Recommended approaches to recovery

Table 4. Recommended approaches to recovery of the Hoptree Borer in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, Management |

1.0 Support Common Hoptree (host species) recovery objectives such as:

|

Threats:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection, Management |

1.1 Work with key partners to coordinate Hoptree Borer recovery with Common Hoptree recovery planning

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Short-term | Protection, Management | 1.2 Develop a habitat regulation to define the area protected as habitat for the Hoptree Borer in Ontario. |

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

2.1 Initiate a monitoring program to assess population size and trends

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

2.2 Conduct surveys in suitable habitat to improve knowledge of Ontario range of Hoptree Borer

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

2.3 Conduct research on known and potential threats:

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

2.4 Conduct research on life history and basic biology:

|

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Short-term | Protection, Management | 3.1 Restrict use of Btk and other insecticides in and near Hoptree Borer habitat. |

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Protection, Management | 3.2 Promote practices that encourage growth and survival of Common Hoptree on road rights-of-way and transmission lines. |

Threats:

|

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of the Environment, Conservation and Parks on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Hoptree Borer is a habitat specialist dependent on Common Hoptree. Although the biology of Hoptree Borer is poorly understood, Common Hoptree distribution and habitat requirements are well known in Ontario. Ontario adopted the Common Hoptree federal recovery strategy in 2013 and the approach used to identify critical habitat is to be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Based on the Common Hoptree critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy (Parks Canada Agency 2012), it is recommended that areas for consideration for a habitat regulation for Hoptree Borer include all mapped polygons identified as critical habitat for Common Hoptree where Hoptree Borer are known to be present. For newly identified occurrences of Hoptree Borer (e.g., Burrell and Sutherland, pers. comm. 2018) where critical habitat for Common Hoptree has not been identified, a similar approach is recommended.

The biophysical attributes of Common Hoptree critical habitat include open to moderately vegetated areas, often with a relatively high level of natural disturbance or harsh environmental conditions. These attributes occur in the following locations and situations (Parks Canada Agency 2012):

- Open shoreline; graminoid (grass like plant) tallgrass prairie; graminoid, shrub and treed sand dune and thicket Ecological Land Classification (ELC) vegetation types and ecosites (where vegetation types have not been identified); as well as the open forest edges that occur in sandy, well-drained, often xeric soils along the highly disturbed beaches and sand dunes of Lake Erie.

- Other droughty substrates such as thin soil over limestone (i.e., the open, shrub and treed alvar and thicket vegetation types and ecosites [where vegetation types have not been identified] of Pelee Island).

- Forest and thicket edge interfacing with the bedrock/open beach/bar shoreline of Middle Island and Pelee Island.

- Lake-bottom clays and clay-loams of Pelee Island drainage ditches.

- A circle with a radius of 9 m surrounding the trunk of each known, live, individual, naturally occurring Common Hoptree at identified locations (i.e., where data points currently exist), based on a critical root zone definition, used as a zone of protection for trees, of up to 36 times the diameter at breast height (dbh) of a tree (Johnson 1997).

Critical habitat for Common Hoptree is currently identified and mapped in the federal recovery strategy (Parks Canada Agency 2012). The locations and attributes of critical habitat were identified using the best available information on Common Hoptree distribution including observation data on the presence of a single tree or cluster of trees. Where specific point locations were unavailable, the vegetation communities (ELC vegetation types or ecosite polygons) surrounding the Common Hoptree occurrences were identified. Existing infrastructure (including roads, trails, parking lots, utility corridors and buildings), cultivated areas and unnatural vegetation types (e.g., baseball fields, grassed areas and septic beds) are excluded from these areas. Utility corridors and road rights-of-way are also excluded from critical habitat.

Approach based on ELC Vegetation Type and Ecosite:

Where data were available to identify Common Hoptree within one or more ELC units (vegetation type or ecosite, where vegetation types were not available), critical habitat was identified as the boundaries of the occupied ELC unit(s), provided that they were considered suitable for survival and recovery of the species. The areas recommended for a habitat regulation for Hoptree Borer include:

- NCC Richard and Beryl Ivey property on the north side of East West Road, across from the winery, Pelee Island (+/- 25 m of 41o 45’ 24.8” N, 82o 40’ 37.5” W)

- Point Pelee National Park, Leamington, Essex County: the occupied Sea Rocket Sand Open Shoreline (SHOM1-2

footnote 1 ), Beach Grass – Wormwood Open Graminoid Sand Dune (SBOD1-3), Little Bluestem – Switchgrass– Beachgrass Open Graminoid Sand Dune (SBOD1-1), Hoptree Shrub Sand Dune (SBSD1-2), Red Cedar Treed Sand Dune (SBTD1-3), Dry – Fresh Drummond’s Dogwood Deciduous Shrub Thicket and Fresh – Moist Cottonwood Deciduous Forest (FODM8-3) Vegetation Types adjacent to the shores of Lake Erie (Lee 2004, Dougan and Associates 2007, Jalava et al. 2008). - The north portion of Fish Point Provincial Nature Reserve, Pelee Island: all occupied ELC vegetation types and ecosites (where no vegetation types are defined).

Approach based on the observation of trees:

Where no vegetation community mapping is available and if the area cannot be mapped, an occupancy approach, based on the observation of trees, is recommended. Critical habitat was based on UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system) locations of individual trees or clusters of trees, obtained using a GPS (geographic positioning system) unit. Coordinates obtained using this technology are expected to be accurate to at least 10 m.

In these situations, the area within which critical habitat (based on biophysical attributes) is found is identified as a rectangle that stretches 150 m perpendicular to the water’s edge to encompass the tree(s) and extends along and parallel to the shoreline 150 m on either side of the Common Hoptree(s). The 150 m value was chosen as surveyors in the Niagara Region indicated that most populations seemed to be a maximum of 150 m long (Brant pers. comm. 2009).

As some data points represent multiple trees and it is unclear where within the tree cluster the coordinates were taken, the 150 m distance has been applied in either direction parallel to the shoreline to ensure critical habitat protection along a 300 m stretch of shoreline. The area recommended for considering a habitat regulation for Hoptree Borer includes:

- The vicinity of West Shore Pump Station on the west shore of Pelee Island: bordered by the following coordinates: 41o 47’ 41” N, 82o 41’ 8” W; 41o 47’ 40” N, 82 o 41’ 2” W; 41o 46’ 50” N, 82o 41’ 15” W; 41o 46’ 49” N, 82 o 41’ 9” W.

Critical habitat is not mapped for Common Hoptree at the following location where Hoptree Borer is known to be present (Burrell and Sutherland, pers comm. 2018). A similar approach (identified above) to identify habitat is recommended.

- Harris-Garno Road at quarry, Pelee Island (+/- 100 m in either direction of 41o 48’ 59.6” N, 82o 38’ 46.3” W).

Glossary

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC):

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO):

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank:

- A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

- 1 = critically imperilled

- 2 = imperilled

- 3 = vulnerable

- 4 = apparently secure

- 5 = secure

- NR = not yet ranked

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA):

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List:

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Boutin, C., T. Dobbie, D. Carpenter and C.E. Hebert. 2011. Effects of Double-crested Cormorants (Phalacrocorax auritus Less.) on island vegetation, seedbank, and soil chemistry: evaluating island restoration potential. Restoration Ecology 19:720-727.

Burrell, M. and D. Sutherland 2018. pers. comm. Email correspondence to A. Harris. February 2018. Zoologists, Natural Heritage Information Centre, Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario.

Carter D.J. 1984. Pest Lepidoptera of Europe with Special Reference to the British Isles. W. Junk, Publ. Series Entomoligica Vol. 31. 431 pp.

COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Common Hoptree Ptelea trifoliata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 14 pp.

COSEWIC. 2015a. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Hoptree Borer Prays atomocella in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 41 pp.

COSEWIC. 2015b. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Common Hoptree Ptelea trifoliata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xi + 33 pp.

Crins, W.J., P.A. Gray, P.W.C. Uhlig and M.C. Wester. 2009. The Ecosystems of Ontario, Part I: Ecozones and Ecoregions. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough Ontario, Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment, SIB TER IMA TR-616 01. 71 pp.

Dougan and Associates. 2007. Point Pelee National Park Ecological Land Classification and Plant Species at Risk Mapping and Status. Prepared for Parks Canada Agency, Point Pelee National Park, Leamington, Ontario. 109 pp. + Appendices A-H + maps.

Hebert, C.E., J. Pasher, D.V. Weseloh, T. Dobbie, S. Dobbyn, D. Moore, V. Minelga and J. Duffe . 2014. Nesting cormorants and temporal changes in island habitat. Journal of Wildlife Management 78(2):307–313.

Jalava, J.V., P.L. Wilson and R.A. Jones. 2008. COSEWIC-designated Plant Species at Risk Inventories, Point Pelee National Park, including Sturgeon Creek Administrative Centre and Middle Island, 2007. Volume 1: Summary Report. Prepared for Point Pelee National Park, Parks Canada Agency, Leamington, Ontario. vii + 126 pp.

Johnson, G.R. 1997. Tree preservation during construction: a guide to estimating costs. Minnesota Extension Service, University of Minnesota, Minnesota.

Koh S., A.J. Tanentzap, G. Mouland, T. Dobbie, L. Carr, J. Keitel, K. Hogsden, G. Harvey, J. Hudson and R. Thorndyke. 2012. Double-crested Cormorants Alter Forest Structure and Increase Damage Indices of Individual Trees on Island Habitats in Lake Erie. Waterbirds 35(1):13-22.

Knudson E. pers. comm. 2009. Email correspondence to A. Harris. December 2009. Texas.

Lee H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and its Application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide.

Lee, H.T. 2004. Provincial ELC Catalogue Version 8. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch, London, Ontario. Microsoft Excel File.

Markle, C.E., G. Chow-Fraser and P. Chow-Fraser. 2018. Long-term habitat changes in a protected area: Implications for herpetofauna habitat management and restoration. PLoS ONE 13(2): e0192134. Link to full journal article.

Marshall, S.A. pers. comm. 2010. Email correspondence to A. Harris. May 2010. Professor, Department of Environmental Biology. University of Guelph.

Master, L., D. Faber-Langendoen, R. Bittman, G.A. Hammerson, B. Heidel, J. Nichols, L. Ramsay and A. Tomaino. 2009. NatureServe conservation status assessments: factors for assessing extinction risk. NatureServe, Arlington, VA.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. iii + 5 pp + Appendix vi + 61 pp. Adoption of Recovery Strategy for the Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata) in Canada (Parks Canada Agency 2012).

Parks Canada Agency. 2016. Multi-species Action Plan for Point Pelee National Park of Canada and Niagara National Historic Sites of Canada. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Parks Canada Agency, Ottawa. iv + 39 pp.

Parks Canada Agency. 2012. Recovery Strategy for the Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Parks Canada Agency. Ottawa. vi + 61 pp.

Ratnasingham, S. and P.D.N. Hebert. 2007. BOLD: The Barcode of Life Data System (Barcode of Life Website). Molecular Ecology Notes 7, 355–364. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01678.x.

Seneviratne, S. I., Nicholls, N., Easterling, D., Goodess, C. M., Kanae, S., Kossin, J., . . . Zhang, X. 2012. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In C. B. Field, V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, . . . P. M. Midgley, A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) ( pp. 109-230). Cambridge, UK and New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

Surgeoner, G.A. and M.J. Farkas. 1990. Review of Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki (btk) for use in forest pest management programs in Ontario - with special emphasis on the aquatic environment. Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Toronto.