Independent reviewer’s final report on the Jahn Settlement Agreement

Read the final report on the Ministry of the Solicitor General’s compliance with the 2013 Jahn Settlement Agreement. Learn about the terms of the consent order of January 16, 2018 issued by the Ontario Human Rights Tribunal.

February 25, 2020

Justice David P. Cole, Independent Reviewer

Background to this report

I’ve worked in hospital emergency departments. I’ve worked in mental hospitals. But this correctional population contains the most multi-problem people I’ve ever seen in my entire nursing career.

- Senior mental health nurse

By Order in Council O.C. 371/2018 I am appointed by Cabinet to provide “independent progress reports with respect to compliance with the 2013 Jahn settlement of the terms of the order entered as a consent order with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario dated January 16, 2018”. Each of these terms requires some further explanation.

Ms. Christina Jahn was incarcerated at the Ottawa Carleton Detention Centre (OCDC), an adult correctional facility operated by what was then called

- May 25-August 15, 2011. She was initially remanded into custody on charges of assault, obstruct police, assault with a weapon, causing a disturbance and mischief. After some time spent on custodial remand

footnote 2 , she entered pleas of guilty to charges of assault, obstruct police, causing a disturbance and mischief, whereupon she was sentenced to a total of 100 days in custody. - October 3, 2011-February 5, 2012. She was initially remanded into custody on charges of theft under $5,000, assault peace officer and utter threat of death or serious bodily harm. After some time spent on custodial remand, she entered pleas of guilty to charges of theft under $5,000 and assault peace officer, whereupon she was sentenced to a total of 167 days in custody.

footnote 3

Ms. Jahn alleged in a complaint to the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario that she “was immediately placed in segregation and remained there for the duration of both incarcerations, spending 210 days in total isolation…in a 10 by 12-foot cell, with blocked out windows.” Though the MCSCS disputed Ms. Jahn’s assertions as to why she was placed in segregation, the ministry conceded that she “spent some time in segregation during these two periods of incarceration.”

After a period of negotiation between Ms. Jahn’s counsel, MCSCS and the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC)

- PIR#1 required that the ministry complete a report on how best to serve female inmates with major mental illness – this report was to include various options for female inmates with major mental illness, including the viability of building a secure treatment facility for women; special attention would be paid to the development of a variety of mental health assessment, placement and housing components

- development of mental health screening tools and follow up assessment by a physician (if necessary)

- improvements in access to mental health services for incarcerated inmates

- reforms to policies and practices regarding the placement and management of inmates in ”administrative” and ”disciplinary” segregation

- development of ”treatment plans” and ”individualized mental health services” for inmates ”with mental health issues” placed in either form of segregation, as well as the participation of physicians/psychiatrists as part of ”5-day segregation reviews”

- improved mental health training for ministry front line staff and managers

- revisions to its Inmate Handbook ”to reflect the rights and responsibilities of inmates”

- statistical reports to be provided to the OHRC ”concerning the number of female inmates at the Ottawa Carleton Detention Centre placed in segregation…” annually for a period of three years

Given the size of the ministry and the need for substantial revisions to its policies and procedures, various time frames by which the ministry was expected to comply with each of these ”Public Interest Remedies” were agreed to by the parties.

In April 2017 the Ombudsman of Ontario released a Report on segregation in Ontario corrections which was critical of MCSCS’ implementation of its obligations under the Jahn Settlement.

After some negotiation back and forth with the ministry about its responses to these two reports, in September 2017 the OHRC initiated another Contravention Application with the HRTO, alleging

”Four years ago, the Government of Ontario made a legally binding commitment to a vulnerable group of people – prisoners with mental health disabilities. Ontario explicitly recognized that segregation was harmful for this group and agreed, as part of a binding settlement agreement, to prohibit segregation for individuals with mental illness unless it would cause undue hardship. Four years later, two independent reviews have revealed that Ontario has not lived up to that commitment.”

MCSCS responded by claiming that it had in fact “substantially complied” with the ”Jahn Public Interest Remedies” and that these are “complex issues that are not amenable to a quick resolution”.

Following more negotiations a further settlement was reached in January 2018.

”Ontario is engaging in a multi-year process to implement new overarching principles relating to living conditions in correctional institutions which will include creating alternative placements, supporting infrastructure, new staff and staff training.”

Against this backdrop the ministry agreed to “comply operationally with the 2013 Jahn v. MCSCS settlement Public Interest Remedies (PIRs) #2, #4, #5, #6, and #7” as well as to conduct a much broader system-wide comprehensive review of policies and their implementation.

The first element of this new settlement relevant to this background description was the creation of the position of an Independent Expert on human rights and corrections “to assist in implementing the terms of this consent order”.

The second aspect of this new settlement was that MCSCS was required to “establish internal compliance mechanisms to monitor the implementation of and ongoing compliance with the terms of the Jahn consent order and the terms of [the January 2018] consent order”.

- the Jahn settlement remedies and terms of [the January 2018] consent order that have been complied with

- the Jahn settlement remedies and terms of [the January 2018] consent order that remain outstanding

- any non-compliance with the Jahn settlement remedies and terms of [the January 2018] consent order, and if so, recommended steps with associated timelines for promoting compliance

- the effectiveness of the accountability and oversight mechanisms put in place by Ontario, including the mechanisms for assessing undue hardship before placing individuals with mental health disabilities (including those at risk of suicide or self-harm) in segregation

- whether further changes are necessary to address the use of segregation for individuals with mental health disabilities (including those at risk of suicide or self-harm), and whether the ongoing use of segregation for this population is still necessary

- whether any changes are necessary to address the use of alternative housing or restrictive confinement for individuals with mental health disabilities (including those at risk of suicide or self-harm)

- measurable changes to the treatment and experiences of individuals with mental health disabilities (including those at risk of suicide or self-harm) supported by human rights-based data and statistics

footnote 18

The Consent Order specifies that “[t]he content of the final report is not limited to the above, and additional content can be included based on the discretion of the Independent Reviewer”

The original date scheduled in the consent order for production of this progress report was “in the Fall of 2018”. Because of considerable hurdles encountered at various stages of this project, principally stemming from 1. delays in the appointment of the Independent Expert, 2. delays in the production of data sets which could be properly analyzed by Prof. Hannah-Moffat and her team (discussed at length in section 4 of this Report), 3. MCSCS policy changes that continue to the present, the date for production of this Report was delayed until February 28, 2019 on the consent of both MCSCS and the OHRC

The “knock on” effect of these delays has unfortunately resulted in neither the Independent Expert nor myself being able to complete our investigations and analysis by September 30, 2019. Our respective Reports were delivered to the ministry on January 31, 2020, with public release currently scheduled to occur in the Spring of 2020, once stakeholder consultations, translation and formatting of the content to enable posting on the ministry’s website have been completed.

For purposes of completeness I need to add that my Interim Report, which contained an Executive Summary of the Independent Expert’s interim findings and recommendations, was delivered to the ministry on February 28, 2019. As it was entitled to do, the ministry elected not to publicly release my Interim Report. At some later point the OHRC decided to post the Interim Report on its website. Whenever substantive references to my Interim Report are made in this Final Report, a hyperlink is provided that will take the interested reader to the OHRC website.

The contents of this Report are as follows:

- Section 2 contains data on Basic Facts and Figures about Ontario Corrections, including recent data on the numbers of persons in provincial custody (both remand and sentenced) detained in conditions that constitute segregation.

- Section 3 contains my evaluation – as advised by the Independent Expert – of the ministry’s current compliance with the various “Jahn” settlements. It also contains commentary and recommendations by both the Independent Expert and myself about what we jointly consider to be important aspects of the ministry’s ongoing efforts at future compliance with the “Jahn” settlements.

- At my request, Section 4 contains the Independent Expert’s detailed assessment of the ministry’s efforts and progress pertaining to segregation and restrictive confinement tracking, data releases and meaningfulness of their analyses, alternatives to segregation, management or treatment of those who are marginalized due to their mental health concerns and/or sex/gender. It also includes Prof. Hannah-Moffat’s comments and recommendations relating to non-compliance with other “Jahn” settlement remedies and terms of the Consent Order.

- Section 5 evaluates and makes recommendations regarding the responses of both the Ministry of the Solicitor General and the Ministry of the Attorney General to my February 2019 Interim Report.

- Section 6 proposes a series of procedural reforms to the processes by which persons in custody considered to be mentally ill can be placed (and maintained) in conditions that constitute segregation.

- Section 7 describes a series of issues that were necessarily carried over from my February 2019 Interim Report.

- Section 8 describes and recommends the adoption of a new program currently being piloted in Alberta provincial corrections which aims to increase the speed and number of bail releases of mentally ill (and severely addicted) accused persons, with particular attention to issues of stable housing.

- Section 9 contains a list of all recommendations made by the Independent Expert and myself.

Basic facts and figures about Ontario Corrections

Data sources

| All institutions | Average daily count - males | Average daily count - females | Average daily count - total | Days stay - males | Days stay - females | Days stay - total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity/days x capacity | 8,002 | 681 | 8,683 | 2,903,124 | 247,249 | 3,150,373 |

| Remand | 4,857 | 422 | 5,279 | 1,772,860 | 153,882 | 1,926,742 |

| Provincial sentence | 1,612 | 146 | 1,758 | 588,384 | 53,379 | 641,763 |

| Intermittent sentence* | 352 | 16 | 368 | 55,243 | 2,501 | 57,744 |

| Federal sentence | 125 | 8 | 133 | 45,665 | 2,838 | 48,503 |

| Immigration | 91 | 4 | 95 | 33,119 | 1,526 | 34,645 |

| Other | 21 | 1 | 22 | 7,806 | 236 | 8,042 |

| Institutional total | 6,858 | 587 | 7,445 | 2,503,077 | 214,362 | 2,717,439 |

* Intermittent sentence average count is the average weekend count, based on 157 "weekend" days rather than 365 days.

| Supervision status | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probation | 31,766 | 6,465 | 38,231 |

| Conditional sentence | 1,619 | 425 | 2,044 |

| Parole | 362 | 37 | 399 |

| Total community caseload | 33,747 | 6,927 | 40,674 |

Totals may differ from the sum of the components due to rounding.

From these two tables it may be seen that approximately 7,445 persons over whom the provincial ministry has jurisdiction were incarcerated in a provincial adult institution on an average day in fiscal 2018/19. This amounts to about 15.5% of all persons being supervised by the ministry.

| Location | Total male admissions | Total female admissions | Total admissions | Total male sentenced admissions | Total female sentenced admissions | Total sentenced* admissions | Total male remand admissions | Total female remand admissions | Total remand admissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algoma Treatment and Remand Centre | 554 | 139 | 693 | 270 | 47 | 317 | 472 | 119 | 591 |

| Brockville Jail | 617 | 0 | 617 | 254 | 0 | 254 | 487 | 0 | 487 |

| Central East Correctional Centre | 3,990 | 577 | 4,567 | 1,787 | 177 | 1,964 | 3,091 | 510 | 3,601 |

| Central North Correctional Centre | 1,999 | 313 | 2,312 | 1,037 | 115 | 1,152 | 1,507 | 267 | 1,774 |

| Elgin-Middlesex Detention Centre | 2,369 | 426 | 2,795 | 934 | 108 | 1,042 | 2,069 | 397 | 2,466 |

| Fort Frances Jail | 153 | 61 | 214 | 28 | 4 | 32 | 144 | 58 | 202 |

| Hamilton-Wentworth Detention Centre | 2,675 | 702 | 3,377 | 1,292 | 158 | 1,450 | 2,339 | 637 | 2,976 |

| Kenora Jail | 1,301 | 334 | 1,635 | 318 | 76 | 394 | 1,295 | 329 | 1,624 |

| Maplehurst Correctional Complex | 6,824 | 6 | 6,830 | 2,502 | 4 | 2,506 | 5,081 | 5 | 5,086 |

| Monteith Correctional Complex | 585 | 115 | 700 | 287 | 42 | 329 | 504 | 111 | 615 |

| Niagara Detention Centre | 1,829 | 1 | 1,830 | 548 | 0 | 548 | 1,616 | 1 | 1,617 |

| North Bay Jail | 530 | 101 | 631 | 233 | 35 | 268 | 431 | 90 | 521 |

| Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre | 3,376 | 599 | 3,975 | 1,587 | 229 | 1,816 | 2,470 | 512 | 2,982 |

| Quinte Detention Centre | 1,710 | 381 | 2,091 | 845 | 141 | 986 | 1,393 | 322 | 1,715 |

| Sarnia Jail | 525 | 114 | 639 | 179 | 21 | 200 | 477 | 102 | 579 |

| South West Detention Centre | 2,067 | 329 | 2,396 | 1,006 | 125 | 1,131 | 1,851 | 312 | 2,163 |

| Stratford Jail | 206 | 0 | 206 | 140 | 0 | 140 | 141 | 0 | 141 |

| Sudbury Jail | 783 | 99 | 882 | 351 | 27 | 378 | 570 | 84 | 654 |

| Thunder Bay Correctional Centre | 1 | 300 | 301 | 6 | 90 | 96 | 3 | 276 | 279 |

| Thunder Bay Jail | 1,269 | 0 | 1,269 | 376 | 0 | 376 | 1,162 | 0 | 1,162 |

| Toronto East Detention Centre | 2,133 | 0 | 2,133 | 757 | 0 | 757 | 1,731 | 0 | 1,731 |

| Toronto South Detention Centre | 8,159 | 17 | 8,176 | 2,244 | 4 | 2,248 | 7,112 | 10 | 7,122 |

| Vanier Centre for Women - Milton | 3 | 2,670 | 2,673 | 2 | 615 | 617 | 3 | 2,363 | 2,366 |

| Total | 43,658 | 7,284 | 50,942 | 16,983 | 2,018 | 19,001 | 35,949 | 6,505 | 42,454 |

* Sentenced admissions are actually sentences to incarceration imposed during the year. The offender may have been in custody on remand at the time of sentencing, so it is not a physical admission. Because there is overlap between remand admissions and sentences imposed (sentenced admissions), they total more than the total institutional admissions. Sentenced admissions also include federally sentenced offenders.

Note: where female admission exists in an all male institution, it is the result of a transgender alert.

| Length category | Males | Females | Total | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 3 days | 7,786 | 1,766 | 9,552 | 22.9 |

| 4 to 7 days | 6,316 | 1,343 | 7,659 | 18.4 |

| 8 to 14 days | 4,514 | 1,009 | 5,523 | 13.3 |

| 15 to 21 days | 2,756 | 561 | 3,317 | 8.0 |

| 22 to 31 days | 2,633 | 481 | 3,114 | 7.5 |

| >1 to 3 months | 6,770 | 889 | 7,659 | 18.4 |

| >3 to 6 months | 2,680 | 225 | 2,905 | 7.0 |

| >6 to 12 months | 1,202 | 71 | 1,273 | 3.1 |

| >1 year | 612 | 26 | 638 | 1.5 |

| Total | 35,269 | 6,371 | 41,640 | 100.0 |

| Average length of remand | 46.0 | 24.0 | 42.7 | n/a |

| Median length of remand | 13.0 | 8.0 | 12.0 | n/a |

Remands ending does not necessarily indicate a release from custody.

| Length category | Males | Females | Total | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 7 days | 3,080 | 510 | 3,590 | 25.6 |

| 8 to 14 days | 1,531 | 255 | 1,786 | 12.7 |

| 15 to 29 days | 2,005 | 311 | 2,316 | 16.5 |

| 1 month | 302 | 39 | 341 | 2.4 |

| >1 to <3 months | 2,876 | 329 | 3,205 | 22.8 |

| 3 months | 69 | 5 | 74 | 0.5 |

| >3 to <6 months | 1,334 | 132 | 1,466 | 10.5 |

| 6 months | 89 | 12 | 101 | 0.7 |

| >6 to <12 months | 790 | 44 | 834 | 5.9 |

| 12 months | 28 | 0 | 28 | 0.2 |

| >12 to <18 months | 280 | 6 | 286 | 2.0 |

| 18 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| >18 to <24 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| >2 years | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 12,384 | 1,643 | 14,027 | 100 |

| Average provincial sentence | 61.3 | 37.5 | 58.5 | n/a |

| Median provincial sentence | 25.0 | 18.0 | 23.0 | n/a |

From this table it may be seen that over 91% of sentenced prisoners served less than six months on a provincial sentence, and 57.3% served sentences of less than one month in 2018/19.

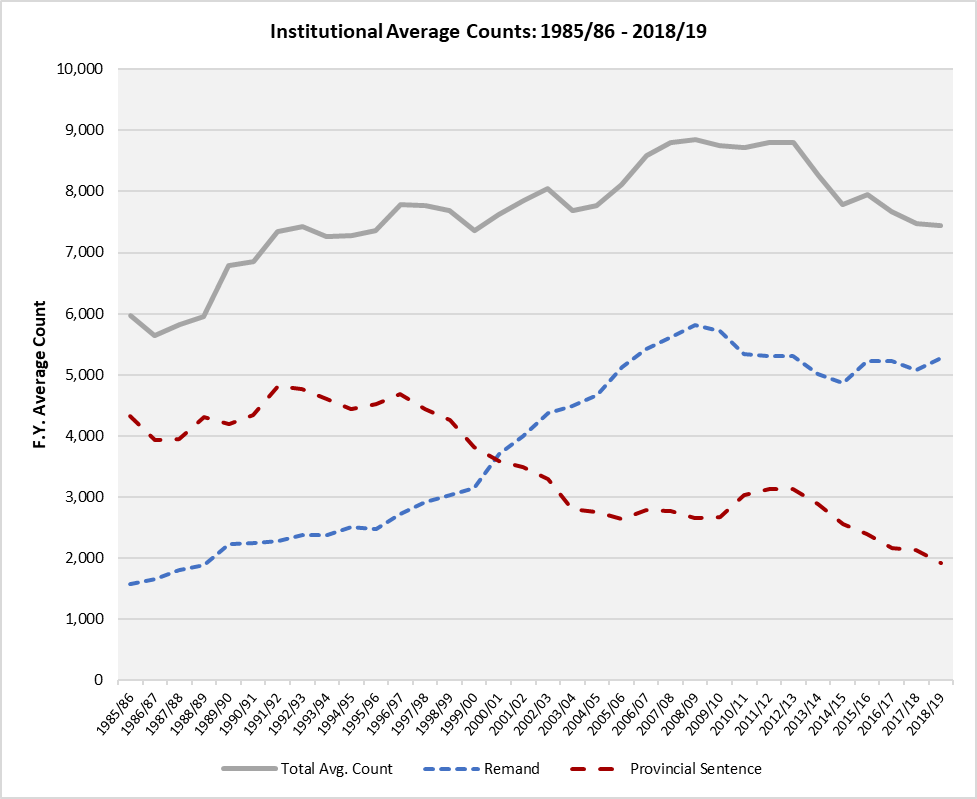

Table 6: Institutional average counts: 1985/86 – 2018/19

Tables 4-6 reflect the changing nature of Ontario’s adult custodial population over time. Though the figure varies slightly over the last few years (and can even vary from month to month

| Year | Total custodial population | Segregated population | Percentage of custodial population in segregation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 8,851 | 453 | 5% |

| 2009-10 | 8,755 | 441 | 5% |

| 2010-11 | 8,723 | 466 | 5% |

| 2011-12 | 8,802 | 478 | 5% |

| 2012-13 | 8,806 | 470 | 5% |

| 2013-14 | 8,262 | 472 | 6% |

| 2014-15 | 7,785 | 499 | 6% |

| 2015-16 | 7,952 | 538 | 7% |

| 2016-17 | 7,673 | 577 | 8% |

| 2017-18 | 7,474 | 628 | 8% |

| 2018-19 | 7,445 | 678 | 9% |

| 2019-20 YTD | 8,161 | 603 | 7% |

Due to rounding, totals of male and female from the tables below may not add to the totals in the above table.

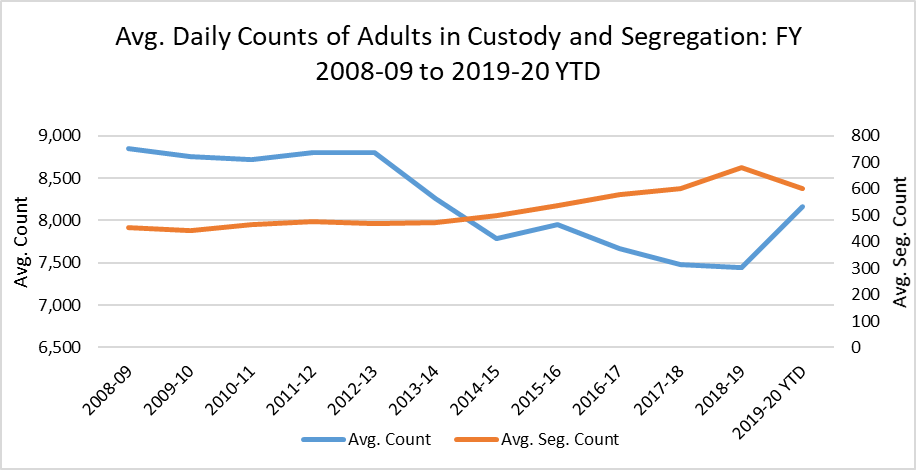

Although the average count in 2018/19 appears similar to the average count in 2017/18, the increase in the adult population began in 2018/19 rising 10.8% between April 2018 (7,171) and March 2019 (7,943) and this trend continues into the current fiscal year.

Source: Ministry of the Solicitor General

| Year | Total male custodial population | Male segregated population | Percent of men in custody in segregation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 8,235 | 430 | 5% |

| 2009-10 | 8,160 | 418 | 5% |

| 2010-11 | 8,137 | 441 | 5% |

| 2011-12 | 8,182 | 448 | 5% |

| 2012-13 | 8,161 | 441 | 5% |

| 2013-14 | 7,634 | 444 | 6% |

| 2014-15 | 7,204 | 469 | 7% |

| 2015-16 | 7,320 | 503 | 7% |

| 2016-17 | 7,080 | 543 | 8% |

| 2017-18 | 6,904 | 579 | 8% |

| 2018-19 | 6,858 | 622 | 9% |

| 2019-20 YTD | 7,462 | 559 | 7% |

2019/20 YTD includes from April 1 to October 31, 2019

| Year | Total female custodial population | Female segregated population | Percent of women in custody in segregation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 615 | 22 | 4% |

| 2009-10 | 595 | 24 | 4% |

| 2010-11 | 586 | 25 | 4% |

| 2011-12 | 620 | 30 | 5% |

| 2012-13 | 645 | 28 | 4% |

| 2013-14 | 629 | 28 | 4% |

| 2014-15 | 581 | 30 | 5% |

| 2015-16 | 632 | 35 | 6% |

| 2016-17 | 593 | 34 | 6% |

| 2017-18 | 570 | 50 | 9% |

| 2018-19 | 587 | 56 | 10% |

| 2019-20 YTD | 699 | 44 | 6% |

2019/20 YTD includes from April 1 to October 31, 2019

Source: Ministry of the Solicitor General

Figure 1 - Yearly averages of daily counts of adults in custody and segregation in Ontario correctional institutions, 2008/09-2019/20 YTD

2019/20 YTD includes from April 1 to October 31, 2019

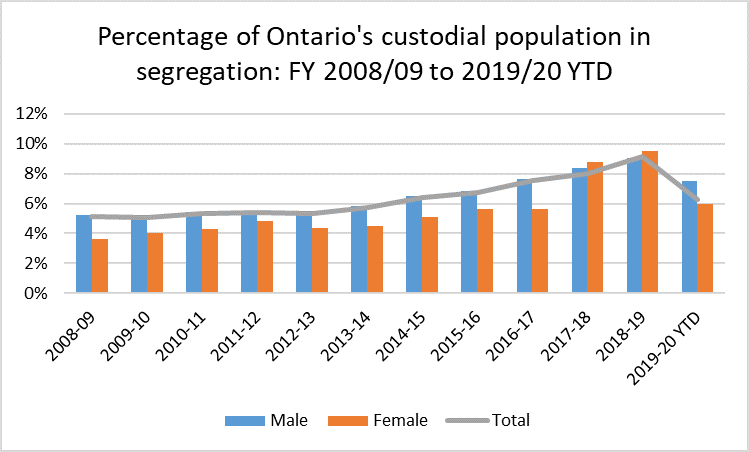

Figure 2 - Percentage of Ontario’s male, female and total custodial populations in segregation, 2008/9-2019/20 YTD. Calculations based on yearly averages of daily counts of adults in custody and segregation.

2019/20 YTD includes from April 1 to October 31, 2019

By way of comparison, figures recently provided by British Columbia provincial corrections indicate that “for fiscal year 2017/18, the average daily count of individuals housed in a segregation unit was 125, which represents approximately 4.8% of the total inmate population”.

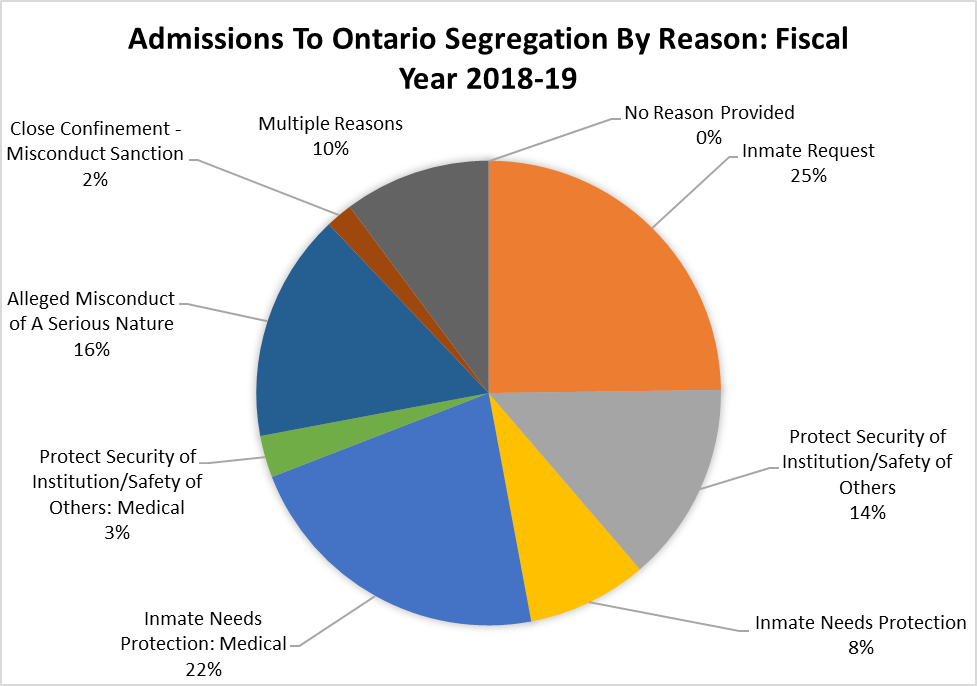

Figure 3 - Admissions to segregation in Ontario correctional facilities in 2018/19, broken down by reason for admission to segregation. “Multiple reasons provided” refers to inmates who were admitted and/or continuously held in segregation for multiple reasons.

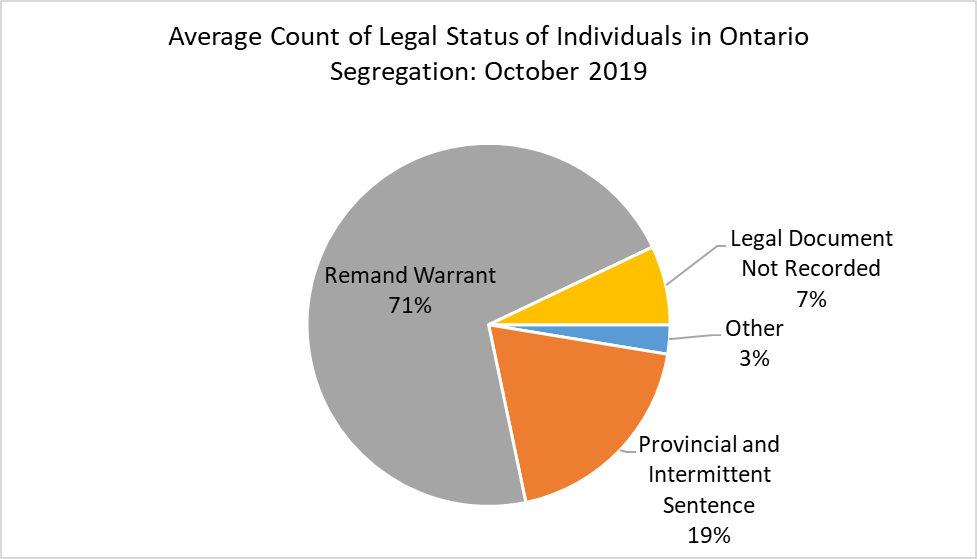

Figure 4 - Legal status of individuals in segregation in October 2019. (The category “Other” includes immigration holds, extradition holds, federal sentences, national parole violations, remand & immigration holds, and remand and national parole violations).

| Institution | 2017-18 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Maplehurst Correctional Complex (Central region) | 9% | 12% |

| Ontario Correctional Institute (Central region) | 1% | 0% |

| Toronto East Detention Centre (Central region) | 12% | 13% |

| Toronto Intermittent Centre (Central region) | 5% | 10% |

| Toronto South Detention Centre (Central region) | 4% | 5% |

| Vanier Centre for Women (Central region) | 12% | 18% |

| Brockville Jail (Eastern region) | 9% | 15% |

| Central East Correctional Centre (Eastern region) | 11% | 12% |

| Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre (Eastern region) | 14% | 15% |

| Quinte Detention Centre (Eastern region) | 11% | 19% |

| St. Lawrence Valley Centre (Eastern region) | 1% | 2% |

| Algoma Treatment & Remand Complex (Northern region) | 9% | 11% |

| Central North Correctional Centre (Northern region) | 10% | 14% |

| Fort Frances Jail (Northern region) | 9% | 11% |

| Kenora Jail (Northern region) | 4% | 4% |

| Monteith Correctional Complex (Northern region) | 8% | 8% |

| North Bay Jail (Northern region) | 10% | 12% |

| Sudbury Jail (Northern region) | 13% | 12% |

| Thunder Bay Correctional Centre (Northern region) | 5% | 2% |

| Thunder Bay Jail (Northern region) | 2% | 4% |

| Brantford Jail (Western region) | 5% | … |

| Elgin-Middlesex Detention Centre (Western region) | 7% | 9% |

| Elgin-Middlesex Detention Centre - Regional Intermittent Centre (Western region) | 3% | 13% |

| Hamilton-Wentworth Detention Centre (Western region) | 5% | 6% |

| Niagara Detention Centre (Western region) | 14% | 17% |

| Sarnia Jail (Western region) (Western region) | 13% | 11% |

| South West Detention Centre (Western region) | 7% | 10% |

| Stratford Jail (Western region) | 3% | 4% |

Only fiscal year 2017 onward are presented here as by April 2017, segregation was being reported through the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS) and Care in Placement Screen. This allowed segregation to be reported as a status and not only a place. Prior to this, segregation was reported through the manual midnight counts and was only based on unit.

Source: Ministry of the Solicitor General

| Institution | Year constructed | Age in 2019 | Operational capacity (as of November 3, 2019) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brockville Jail | 1842 | 177 | 48 |

| Brantford Jail | 1850 | 169 | … |

| Stratford Jail | 1901 | 118 | 50 |

| Fort Frances Jail | 1908 | 111 | 22 |

| Thunder Bay Jail | 1928 | 91 | 142 |

| Sudbury Jail | 1928 | 91 | 163 |

| Kenora Jail | 1929 | 90 | 159 |

| North Bay Jail | 1929 | 90 | 100 |

| Monteith Correctional Complex | 1960 | 59 | 210 |

| Sarnia Jail | 1961 | 58 | 76 |

| Thunder Bay Correctional Centre | 1965 | 54 | 124 |

| Quinte Detention Centre | 1970 | 49 | 237 |

| Ottawa-Carleton Detention Centre | 1972 | 47 | 456 |

| Ontario Correctional Institute | 1973 | 46 | 186 |

| Niagara Detention Centre | 1973 | 46 | 228 |

| Maplehurst Correctional Complex | 1976 | 43 | 888 |

| Toronto East Detention Centre | 1977 | 42 | 368 |

| Elgin-Middlesex Detention Centre | 1977 | 42 | 426 |

| Regional Intermittent Centre | 2016 | 3 | 102 |

| Hamilton-Wentworth Detention Centre | 1978 | 41 | 524 |

| Algoma Treatment and Remand Centre | 1990 | 29 | 133 |

| Central North Correctional Centre | 2001 | 18 | 980 |

| Vanier Centre for Women (Milton) | 2001 | 18 | 312 |

| Central East Correctional Centre | 2001 | 18 | 864 |

| St. Lawrence Valley Correctional & Treatment Centre | 2003 | 16 | 100 |

| Toronto Intermittent Centre | 2011 | 8 | 250 |

| Toronto South Detention Centre | 2012 | 7 | 1,272 |

| South West Detention Centre | 2013 | 6 | 282 |

* Note that this table only reflects original construction dates, and does not capture major projects that were undertaken to retrofit or add capacity to an existing institution.

Report on ministry compliance with Jahn deliverables

Every 18 months or so, this ministry makes some big ‘splash’ promising ‘reforms’ to policies or practices. But once public attention has died down, budgetary constraints soon take over, so these promises never amount to anything. In reality, nothing ever changes in this ministry.

- GTA probation officer with 35 years experience

1. Formal report on ministry compliance with “Jahn” deliverables

Pursuant to the 2013 and 2018 Jahn settlements, MCSCS (since renamed Ministry of the Solicitor General) is responsible for implementing 31 time-specific deliverables. These focus on five key themes:

- data collection

footnote 32 - redefining segregation

footnote 33 - segregation reporting and tracking

footnote 34 - enhanced mental health screening

footnote 35 - compliance and implementation

footnote 36

At the time of my Interim Report (PDF, 2 MB) (February 2019), the ministry reported that 26 deliverables had been completed and reported to the Ontario Human Rights Commission, the Independent Expert and the Independent Reviewer. The remaining deliverables were due to be initially completed between April 19 and October 31, 2019

I am satisfied that Ontario has now met the deadlines to submit data for all 31 deliverables specified in the consent orders in a timely manner. I am also satisfied that the ministry is in the process of making substantial improvements in tracking segregation and restrictive confinement, as well as undertaking a variety of reforms to some of its policies and procedures. For these efforts, which have involved (and will no doubt continue to involve) significant commitments of institutional and corporate staff time and energy, as well as some considerable reorganization of ministry corporate structures, the ministry should be commended.

Having said this, I join with the Independent Expert when she concludes (in section 4 of this Report):

…As of this date (January 31, 2020), it is my expert opinion that the ministry is not yet in full compliance with the requirements outlined in the Jahn settlement…. The ministry’s future plans for compliance with Jahn compliance are important and laudable, but do not replace the requirement for the schedule items to be implemented…in a timeframe that allows the Independent Reviewer and me to assess, which did not occur.

In order to highlight what we jointly consider to be some of the most significant outstanding deficiencies, the following are outlined here:

Establishing a mental health screening tool: The Independent Expert’s Interim Executive Summary, which is included in her Final Report, recommended that the ministry undertake a culturally informed and gender-based evaluation of the tools being used in its institutions in order to meet the PIR#2 requirements. As of November 2019, the Independent Expert reminded the ministry that it needed to undertake such an evaluation in order to satisfy the PIR#2 requirements.

As of February 19, 2020, we have been made aware that the ministry has agreed to consider completing a study to determine whether the Brief Jail Mental Health Screening tool (BJMHS) is sufficiently gender-responsive and culturally informed to meet the needs of Ontario’s population. The ministry advises that it is still in the process of determining which of its many tools and forms may need to be assessed.

Mental health reassessments: The Jahn settlement and Consent Order require that the ministry conduct mental health reassessments at least once every six months (PIR#2, A1, B11(d)).

Based on the materials and data from the compliance review, it appears that Ontario has yet to institute a consistent practice whereby individuals are reassessed at least once every six months. Thus, I join with the Independent Expert when she concludes that the ministry has not complied with this requirement.

Defining segregation: The various Jahn settlements and Consent Order terms (B1, B3) a) require the ministry to develop and apply a revised definition of segregation to all of the various settlement and Order terms, and b) to set out the revised definition in policy (B2).

Based on discrepancies between policy and practice (see especially the Independent Expert’s concerns regarding ‘segregation tracking’ and the ‘gray zone’ discussed in detail in section 4), Ontario has not yet produced clear and consistent policies, procedures, and working definitions of segregation, restrictive confinement, mental health, and associated alerts during the reporting period. Thus, the requirement that Ontario consistently apply the revised definition of segregation has not yet been achieved

Five-day segregation reviews: The various settlements and Orders require that the ministry review the circumstances of individuals with mental health disabilities in segregation at least once every five days, and that these reviews document that all alternatives have been considered to the point of undue hardship, including whether a Treatment Plan is in place (PIR#6, A1).

The Independent Expert notes numerous issues with these reviews. In her report she writes: “Since Ontario has not instituted a break in segregation that is qualitatively different from segregation itself, the segregation clock and timing of these reviews may not occur at the intended five, 10 and 14-day markers”. I fully adopt both this summary of her findings on point and her detailed analysis of this issue (in section 4). She also cautions that “without sufficient resources for restructuring, alternatives and associated front-line supports, these regional-level reviews will likely remain pro-forma exercises”. I again accept her views.

I appreciate that Ontario has laid out new policies providing timely reviews. However, at various portions in my Report (see particularly section 6), I caution – and reiterate here – that in the absence of policies establishing truly independent reviews of such decisions, even if Ontario is able to address the Independent Expert’s concerns about timeliness, the possibility of Capay-type cases arising again is entirely possible.

I thus conclude that Ontario is not adequately in compliance on this subject of five-day segregation reviews.

Identifying and defining all housing placements other than general population: The Consent Order requires that the ministry identify and categorize all alternative housing placements (B6), set these out in policy by June 2018 (B7), and apply these alternative housing strategies across the correctional system by December 2018 (B7).

As described in section 6, the ministry has substantially revised its PSMI policy to designate four alternative housing placement categories. In our respective reports, both the Independent Expert and I agree that, if properly applied, these new categories have the capacity to transform the frequency and longevity of placement in “conditions that constitute segregation”. However, I agree with the Independent Expert when she has proposed revisions to the PSMI policy “to ensure clearer parameters and standards to facilitate Ontario’s operational compliance with the requirements of the Order”. As previously indicated, though the ministry accepted in December 2018 that some of the Independent Expert’s recommendations should be included in a revised policy document, we have not yet seen it, and we are told that it will not likely be implemented until “some time in 2020”.

Furthermore, we both remain very concerned that some of these specialized care categories have the potential to amount to segregation by another name. The Independent Expert puts this in terms of “Ontario has not yet set hard time-out-of-cell parameters for specialized care that exceed the two-hour threshold marking segregation”. I agree with that, but I also base my concern on various reports from the Office of the Correctional Investigator and Prof. Michael Jackson’s writings about their many years of experience with federal corrections, where, until very recently, despite voluminous written policies about the rules surrounding “administrative segregation”, there is clear evidence that such policies have been frequently ignored.

Thus, because we have not yet been provided with clear evidence indicating that Ontario, despite updating its PSMI policy to define alternative housing strategies, has met its requirements to apply these consistently and/or as alternatives to segregation in a meaningful way, we are unable to say whether Ontario is in compliance.

Human rights data — The Consent Order requires that the ministry annually release data on: (a) its use of segregation and restrictive confinement (B15, B17), and (b) the proportion of individuals in the overall correctional population with mental health difficulties and breakdown of the correctional population based on sex/gender (B16).

Much of the Independent Expert’s report sets out and exhaustively discusses numerous issues regarding the ministry’s data collection and release, especially in regards to restrictive confinement. Beyond agreeing with what she says, it is unnecessary to repeat what she says in section 4.

I thus join with the Independent Expert when she concludes that the ministry remains non-compliant with the human rights data collection and reporting requirements.

Our respective Orders in Council are scheduled to lapse at the end of February 2020. In light of the need to address these various continuing deficiencies in a timely and consistent manner, the Independent Expert and I have jointly decided to recommend: (a) the immediate establishment of a Committee of Experts on Data, Best Practices and Policy Compliance (b) the immediate establishment of a Ministerial Advisory Committee on the Treatment of Mentally Ill Inmates, and (c) the immediate proclamation of those portions of the Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, already passed by the legislature, that establish an office of Inspector General of Correctional Services. Our rationales for each of these are discussed in the remainder of this section.

2. Observations of the ministry’s commitment to research and related issues – joint statement of the Independent Expert and the Independent Reviewer

We find it necessary to make some overall comments about the ministry’s responses to the various Jahn settlements. While we have been in our respective roles for about two years, it cannot be ignored that the ministry’s failure to commit itself fully to and implement the various Jahn remedies has now been going on for nearly 6 1/2 years. For numerous senior officials (corporate and field) to continually rationalize the ministry’s lack of substantive response to the Jahn litigation with phrases such as “it takes a lot of effort to turn a big ship around”, or “things are different now as we have new managers and structures in place”, or “we have to await political direction, which takes time” is simply inadequate, given the gravity of the issues involved. We are particularly concerned that the commentary by a very experienced ministry staffer quoted at the beginning of this section may well reflect what will happen if substantial external oversight is not immediately instituted across the ministry.

We attribute much of this to the ministry’s observed “insularity” in relation to (a) its overall commitment to cross-jurisdictional research, and (b) its approach to its role as part of Ontario’s criminal justice system, and it is to these subjects that we now feel compelled to turn.

a. Ministry research into cross-jurisdictional developments:

When Prof. Hannah-Moffat and I took up our respective Terms of Reference in early 2018 we presumed that, as a normal and routine part of the background for the [then] recently introduced Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, 2018

When we eventually did receive some documentation, it appeared to us that, on the basis of what was shared over time, little sustained work had been put into any serious comparative canvas of what was happening in other parts of Canada (and elsewhere) as part of the preparation for the new legislative regime. Further, many of the research papers we eventually read tended to be “aspirational” rather than being comprised of detailed analyses of how policies in other jurisdictions might be applied in Ontario. This pattern of two-way communication was by no means unique. On numerous other occasions throughout our mandates we requested to see ministry-developed documents explaining the evidence-based rationales for both existing and proposed policy changes. It is our firm conclusion that too many of these documents shared were neither well-researched nor particularly well-reasoned.

Though it must be said that over time much has changed in a positive direction in terms of facilitating our access to documents, on the basis of what was shared over time, it seemed clear that insufficient effort was being expended towards routinely surveying comparative developments in other provinces, in federal corrections and in other countries. Consequently, our inferences based on these experiences were that ministry background papers and studies all too often seem to randomly reference only one or two other provincial correctional systems. They were not reflective of comprehensive canvasses of other jurisdictions – Canadian and offshore - facing many of the same problems as Ontario.

Having received little or no ministry-developed comprehensive canvasses of cross-jurisdictional studies and other materials, we deemed it necessary to instruct our research assistants to spend considerable parts of the summer and fall of 2018 collecting and analyzing these materials, many of which are readily accessible on public websites or in easily researchable academic journals.

Once again, when Prof. Hannah-Moffat and I shared studies and materials we had come across in our reviews of interprovincial and international developments, it is obvious that in some quarters these offers have been either ignored or have been greeted with little or no follow through. Similarly, where we offered to share examples of research reports from other jurisdictions

A draft of this portion of our joint Report was delivered to the ministry on February 4, 2020. On February 19 the ministry responded that: “…extensive work was completed as part of the development of the CSRA, including literature reviews of segregation and independent oversight. The ministry is providing examples of some of the reviews and scans for the IR’s consideration”. This was of course entirely new to both the IE and myself. When these were sent to us on February 21, the accompanying emails referred to us being given “a few documents” and “some examples of literature reviews and jurisdictional scans”. This communication, which was received one week before the scheduled termination of our mandates, references ministry documents dating from 2015-2017.

From this narrative, we derive the following:

- It is clear that the ministry has been in possession of numerous comprehensive scans prior to, and throughout the entire duration of our respective mandates.

- It is obvious that these have only been disclosed in anticipation of what we might be documenting in the Final Report.

- Since we have only been given “a few” or “some” of these materials, we are unable to discern exactly what other materials are in the ministry’s possession.

- No explanation has been offered at any point to explain or offer a rationale why these (and any other) jurisdictional scans have not been previously shared with us.

- The ministry has made no admission of wrongdoing, nor has any apology been offered. This takes on particular salience when we recall how much of our research assistants’ time (as well as taxpayer fiscal contribution) was wasted by having to duplicate that which was already in the ministry’s possession - materials that could so easily have been disclosed in a timely fashion.

- This inevitably makes us somewhat dubious about other areas identified where the ministry has claimed not to have materials which we sought.

This experience reinforces our conclusion that several types of external oversight – none of which currently exist within the ministry - are essential to ensure that, inadvertently or otherwise, ministry-generated cross-jurisdictional studies are readily available to those who need to examine them, including academic researchers. This is discussed later in this section.

At one point during our mandates, we were informed that the ministry was working toward the development of what was to be called a “Knowledge Development/Dissemination Hub”, where it was intended that, inter alia, cross-jurisdictional materials would be routinely posted (electronically or otherwise) for the benefit of ministry staff, OPS researchers and policy developers

- a comprehensive, searchable inventory of all justice sector research the ministry is affiliated with, available to RAIB to all ministry partners

- publication of a periodic research newsletter, where updates on current ministry-affiliated research can be provided

- when and where appropriate hosting of research symposia, which would provide a spotlight for ministry-affiliated research to be showcased, as well as networking opportunities for researchers, SolGen, and relevant partners”

footnote 44

While the ministry is to be commended for this initiative, our continuing concern is that none of these “channels and platforms” appear to have an articulated mandate to specifically focus on cross-jurisdictional research. In our joint view, this is simply inadequate. On the basis of our experience, there is currently no place where ministry staff, other OPS (and academic) researchers and policy developers can readily and routinely find out what other (Canadian and offshore) jurisdictions have developed policies and procedures designed to improve conditions for the mentally ill in custody. In our joint view, this is simply inadequate. Ontarians have a right to expect that the ministry will conduct itself accordingly. It goes without saying that this may in turn contribute to public safety.

3.1 It is jointly recommended ongoing research and knowledge dissemination being conducted by the ministry should be staffed by professionals knowledgeable about how to conduct and compile cross-jurisdictional research studies. It is further recommended that descriptions of the evolution and availability of such studies should be regularly shared with the proposed Committee of Independent Experts on Data, Best Practices and Policy Compliance (described

This will hopefully link the promotion of operational modernized policies to the viability and utility of the ministry’s goals and mandates.

b. Ministry data sources:

Prof. Hannah-Moffat’s Independent Expert Report (section 4 of this Report) separately details her findings regarding the ministry’s commitment to sound data and best practices. Here, we wish to highlight our concern about the absence of external oversight into ministry data collection and analysis, and best practices, particularly given that our respective mandates are set to expire at the end of February 2020.

As Independent Reviewer, with input from the Independent Expert, I am expressly required by my Terms of Reference to report and comment on the “effectiveness of the accountability and oversight mechanisms put in place by Ontario, including the mechanisms for assessing undue hardship before placing individuals with mental health disabilities…in segregation”. Thus, Ontario is required to establish internal mechanisms for monitoring of their ongoing compliance with the terms of the Order. An effective accountability and oversight system should promote systemic changes so that segregation is at least minimized, if not completely phased out in the long-term. In the short-term, this system must ensure that segregation is not used for those with identified mental health conditions, nor that its use is discriminatory on the basis of Code-related factors. An effective oversight system can then be premised on an in-depth examination of patterns and drivers of segregation.

As part of the ministry’s response to the various Jahn initiatives, the ministry has recently created an “Oversight and Accountability Unit” within the “External

While we applaud the establishment of this Unit (and Branch), it is our joint view that the current reporting structure of the Unit (i.e., reporting to a branch under the assistant deputy minister of Operational Support) significantly limits cross-divisional alignment with the requirements of the Order. Furthermore, its oversight role is constrained to conducting baseline and compliance audits, with little ability to address the systemic or institutional-based concerns, which we see as vitally important given the ever-increasing centrality of mental health in contemporary corrections. In our view these bodies should report directly to the deputy minister, rather than reporting more indirectly through the assistant deputy minister of Operational Support.

More broadly, we have concluded that, relevant to policy change overall, Ontario’s effort to satisfy the requirements of the Order have largely occurred in a policy vacuum. In our joint view, many of the requirements of the Order have been neglected because the development of new and necessary policy has been constrained by concerns about what institutions could (and could not) comply with in practice, rather than focusing on what is required by the Order and recent court decisions clearly limiting how and when administrative segregation can be used.

3.2 It is jointly recommended that the ministry establish a unit or branch under the deputy solicitor general’s office that is exclusively focused on compliance with the various Jahn settlements and Consent Orders. This unit or branch must have an on-going and direct line of communication with frontline staff and individuals (anonymous or otherwise) so that institution-specific concerns can be identified, and province-wide operational compliance can be reached. This unit or branch’s audit strategy and outcomes must be publicly posted for increased transparency.

3.3 It is jointly recommended that for all recent policy changes that relate to the Order, Ontario should establish firm time limits for when full operational compliance must be reached. It is further recommended that compliance audit plans and results be shared with the OHRC.

More significantly, we note that these various structures do not envisage any role for review of the work done by this Unit and Branch to be assessed by independent experts separate from government. In our view, particularly given the very considerable difficulties that the Independent Expert has continually encountered in accessing and addressing ministerial data deficiencies, there needs to be an external Committee of Experts expressly mandated to review, evaluate and, if necessary, comment upon the ministry’s various data collection and analysis efforts, its adherence to “best practices”, and both operational and substantive compliance with laws and policies.

In coming to this conclusion, we have consulted on this precise issue with both the Office of the Ombudsman and the Ontario Human Rights Commission, given these organizations’ respective experience over time in detecting and monitoring the treatment of mentally ill persons in custody in Ontario corrections. Both advise that while they envisage themselves as having indirect roles in evaluating ministry compliance, they acknowledge that they lack technical expertise in how best to understand and evaluate the data presented. An external Committee of Experts appears to be the best way to proceed.

3.4 It is jointly recommended that a Committee of Independent Experts be immediately established, mandated to review, evaluate and comment on the ministry’s research capabilities, its data collection and analysis practices, its commitment to evidence-based “best practices”, and its operational and substantive compliance with both laws and policies. This committee should be expressly authorized to have unencumbered access not only to ministry data collection methods, but also to any ministry initiatives and documents that may assist in ensuring that this committee’s mandate can be properly fulfilled. The ministry’s External Oversight and Compliance Branch should be required to report to this committee quarterly, and the committee should regularly report directly to the deputy minister. Wherever possible, the committee’s findings should be publicly reported on the ministry website. This committee should have a mandate to act in this capacity for a three-year period.

c. The ministry’s perception of its role in Ontario’s justice system:

After nearly two years of study and consultation, we are both firmly of the view that the ministry is far too “insular” in its approach and analysis of some of the policy areas it is required to address, especially in the glaring lack of field experience of many of those who are charged with developing policy at the corporate level. This unfortunately manifests itself in several ways:

First, we have been continually troubled that many of those charged with developing and drafting policies in the ministry’s corporate offices have never experienced the realities of institutional corrections for adults in any sustained way. Some of these officials bring experiences from other ministries which do not deal with adult offenders (or, indeed, come from postings entirely outside the criminal justice system). Even more striking is that many officials have little or no knowledge of legislation and case law from other provinces, nor about relevant practices and procedures in other parts of Ontario’s criminal justice system. Our experience is that all too many draft policy documents we have seen reflect piecemeal “policies that can be complied with” rather than policies that are consistent with federal and provincial legislation and case law.

Second, in our opinion this lack of knowledge of “corrections on the ground” all too often seems to be compounded by the fact that within the ministry’s corporate offices, advisors who are, by virtue of their “field experience”, presumed to have particular “expertise” are simply outdated in some of their understandings of criminal law and Ontario’s privacy legislation. Though some of the “field experts” we have encountered are most knowledgeable about the complex issues of managing persons in custody, it must be said that on several occasions we have experienced graphic examples where advice provided by such “experts” is simply wrong or substantially outdated.

No doubt ministry officials will point to extensive processes of consultation with superintendents and other “field” personnel before policies are adopted. While these are no doubt undertaken in good faith, and sometimes result in entirely appropriate amendments to policy proposals, it seems to us that too much energy is unnecessarily expended before this consultation stage is reached. Unfortunately, we have both experienced too many recurrent examples where “field experts” seem quite unwilling to “think outside the box” and pursue evidence-based practices that have been shown to work in other jurisdictions. This is sometimes compounded by a basic lack of empirical knowledge of the problems they are trying to solve. As discussed in the Independent Expert’s Report, one glaring example of this is disclosed in “field” responses to the Independent Expert’s emphasis on “tracking” of segregation and restrictive confinement.

Without necessarily adopting OPSEU’s oft-expressed view that “frequently consultation is merely for show”, we can certainly understand that sentiment. As discussed above, at the very least, there should be greater attention paid to routinely incorporating research reports from Canadian and offshore jurisdictions into policy proposals and ministry background papers.

Finally, we wish to stress that meaningful consultation earlier in policy development processes that are informed by evidence-based research and practices in other jurisdictions will be more cost effective in the long run. Also, timely planning will be economically more in line with competing budgetary domains and will help to enhance and apply the ministry’s strategic goals of modernization.

d. External oversight of the treatment of mentally ill prisoners:

For many years there has been no opportunity for any external province-wide scrutiny of both the efficacy of existing provincial correctional policies and policy development initiatives. Historically, for over a century the Grand Jury in Ontario exercised a kind of rough “oversight” of provincial corrections. When the office of the Grand Jury was abolished (sometime in the 1960s), it was replaced for a time by the Minister’s Advisory Committee on the Treatment of Offenders (MACTO), which existed until some way through the 1980s, when the Committee ceased to function, by virtue of its members’ terms simply not being renewed. Since that time, other than Community Advisory Boards

In order to further communications in line with the ministry’s modernization efforts currently in process of implementation, we would generally support the establishment of one or more properly funded and mandated external advisory bodies to oversee provincial corrections, such as those for First Nations, Inuit and Metis communities envisaged in ss. 23-25 of the Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, 2018. However, given our specific mandate to examine and report on the treatment of mentally ill persons involved in Ontario’s justice and correctional system:

3.5 It is jointly recommended that a properly mandated and adequately funded Ministerial Advisory Committee on the Treatment of Mentally Ill Inmates (MACTMII) be immediately established. One of this committee’s mandates should be to receive regular relevant reports from the ministry’s Research, Analytics and Innovation Branch regarding its various “knowledge dissemination channels and platforms”, as well as from the ministry’s Oversight and Accountability Unit.

We also wish to comment on who might be invited to sit on this advisory body. In July and November, 2017 the ministry convened two “correctional stakeholder roundtables” to discuss issues regarding the treatment of mentally ill offenders in provincial correctional institutions. While the organizations that were invited and the names of those who attended no doubt had many useful contributions to offer, it needs to be said that some of these were not at all representative of those who regularly work on the front lines with mentally ill prisoners (remand or sentenced) and probationers. Without wishing to diminish the excellent work of organizations and individuals who participated, it is noteworthy that a number of important service delivery organizations do not appear to have been invited. For example, several very experienced and knowledgeable service delivery groups that operate at the critical interface between custody and community were not specifically consulted at any stage of these “roundtables”.

e. An inspector general of Correctional Services:

To complement the creation of this proposed ministerial advisory committee, we consider that there is an important lesson to be learned from Canadian federal corrections. At the federal level scrutiny over various national correctional issues has mostly devolved over the past 40 years to the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI), whose occasional special studies and Annual Reports – many of which deal with the treatment of mentally ill offenders in penitentiaries and on conditional release - provide the closest alternative to a significant level of external oversight of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), and related organizations. Following on from several public complaints about Ontario provincial corrections – including the Jahn and Capay cases and findings by the Office of the Ombudsman - Mr. Howard Sapers (who had just retired as the federal Correctional Investigator) was asked by the ministry to investigate and report on various aspects of provincial corrections. Under the title of Independent Reviewer of Ontario Corrections, he and his team produced several significant reports

For reasons that have never been made clear to either of us, there seems to be reluctance to proclaim in force those portions of the CSRA that relate to the establishment and adequate staffing of this new IG office

The main reason MACTO seems to have foundered was because it proved quite impossible for its volunteer members to adequately “keep up” with province-wide developments. Much the same problem appears to exist in other provinces and at the federal level. From what we have discerned from our brief canvas of other jurisdictions, it seems that, as in Ontario, such “advisory” bodies as may exist are usually confined to individual institutions, and opportunities for regional or province-wide consultations with senior correctional officials are few and far between; even those which do exist tend not to be ongoing in any substantial way. Given the lack of any existing external correctional oversight bodies of any kind in Ontario corrections, the need for a provincial correctional IG to provide ongoing oversight becomes even more compelling. Simply put, only an official charged with continuing professional oversight of provincial corrections is going to be in any position “to hold the ministry’s feet to the fire”, especially, as we have regrettably found, a ministry that seems very resistant to change. As previously stated, 6 1/2 years have now elapsed since the initial Jahn settlement, and, as the contents of both the Interim Report and these Final Reports repeatedly disclose, SolGen is still far from complying with the need for fundamental changes revealed by the Capay case and the various Jahn settlements.

3.6 It is jointly recommended that Royal Assent to proclaim Part IX of the Correctional Services and Reintegration Act, 2018, creating the Office of Inspector General (IG) of Correctional Services, should be immediately sought.

We are mindful that the joint comments in this part of the Report are sharply critical of some ministry personnel, attitudes and practices. Nonetheless, since our respective appointments we have certainly noted a considerable “sea change” in approaches towards the tasks we have undertaken. Where once there was ample evidence of resentment about and resistance towards the inquiries, requests and demands that our Terms of Reference require us to investigate, it is clear that many senior ministry officials – both corporate and institutional staff - now accept that “Jahn should not be seen as an obligation, but rather as an opportunity to improve treatment of mentally ill inmates and probationers”

As Independent Reviewer I wish to “flag” in this part of the Report that there is one other significant area where there is insufficient external scrutiny, that being Ontario’s proposed new procedures in relation to decisions to place and maintain a person in “conditions constituting segregation”. As discussed in more detail in section 6 of this Report, through the enactment of a new Regulation on point, the ministry considers that so long as certain procedural limitations are adhered to, it is both appropriate and constitutionally acceptable for senior correctional administrators to review the decisions of other correctional officials. While I accept that, at least until the views of the Supreme Court of Canada are known

Independent Expert's Report

Summary of findings on the Jahn Consent Order

For the Independent Reviewer

Kelly Hannah-Moffat, PhD, Independent Expert on Human Rights and Corrections

Jihyun Kwon, PhD candidate and Kelly Struthers Montford, PhD

February 24, 2020

Table of contents

- Overview

- Impeding reform: ‘voluntary' segregation

- Consent Order deliverables and post-interim assessment of Ontario's compliance

- B11 and B13: Health care reassessment baseline and compliance review

- B15, B16 and B17: Human rights data collection and release

- B5: Tracking continuous and aggregate segregation

- B8 and B9: Defining and tracking continuous and aggregate restrictive confinement

- B-14: Oversight of prolonged segregation

- A9 and B10: Awareness of individuals with mental health disabilities

- PIR4 and B11: Inter-professional teams and care plans

- A11 and B20: Policy and oversight

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix I: Overview of documented negative effects of segregation

- Appendix II: Select materials shared with Ontario

- Appendix III: Reproduction of Interim Executive Summary

I. Overview

The Jahn Consent Order is an agreement between the Ontario Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services (now the Ministry of the Solicitor General), and the Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) regarding Ontario’s commitment to reforming their use of segregation, with specific attention to Code-related needs, namely mental health disability and sex/gender. The Order is the outcome of a human rights application filed by Christina Jahn in 2012 that alleged discriminatory treatment on the basis of gender and disability. Ms. Jahn, who experienced mental health disabilities, addictions, and cancer, was held in prolonged segregation (approximately 210 days) at the Ottawa Carleton Detention Centre. In 2013, Ontario and the OHRC reached an initial order, containing 10 Public Interest Remedies (PIRs).

I was appointed as the Independent Expert on Human Rights and Corrections to provide the ministry with impartial expertise and assistance in implementing the terms of the Consent Order per Order in Council 356/2017. Also per my Terms of Reference, I am required “to provide the ministry with independent advice and expertise on human rights and corrections, and to assist in implementing the terms set out in the Consent Order. This includes providing feedback on the ministry’s efforts and assessing whether the Jahn settlement remedies and terms of the Consent Order have been complied with.”

In January of 2019, I submitted an Interim Report to the Independent Reviewer, Justice David Cole. This Interim Report was written at the request of the Independent Reviewer to assist him in his evaluation of compliance. It was inclusive of ministry materials and actions until December 31, 2018, and included 35 recommendations (see Appendix III). As of today, all recommendations remain in progress and/or pending, some of which include that the ministry undertake a culturally informed and gender-based evaluation of the tools being used in its institutions to satisfy the PIR#2 requirements.

This is my final report, which is also being provided to Justice Cole for consideration in his assessment of compliance in the Final Report that is expected to be publicly released in the first quarter of 2020. As requested by Justice Cole, this report includes my assessment of the ministry’s efforts and progress pertaining to segregation and restrictive confinement tracking, data releases and meaningfulness of analyses, alternatives to segregation, management or treatment of those who are marginalized due to their mental health concerns and/or sex/gender. As requested by Justice Cole, it also includes comments and recommendations relating to compliance with other Jahn settlement remedies and terms of the Consent Order. This report is based on all information I have been provided by the ministry as of February 24, 2020.

Successful implementation of the Consent Order requires the collection of meaningful data and both policy and operational compliance accompanied by sufficient resourcing and proper oversight measures. I agree with the Independent Reviewer, who notes that Ontario has made good efforts to meet various deadlines attached to the deliverables of the Consent Order. Notwithstanding the commendable efforts of ministry staff, it is my conclusion that to date, Ontario is not yet in full compliance with the terms of the Order, including the requirements set out in the initial Jahn settlement.

This conclusion is principally based on Ontario not being able to produce a cohesive policy framework required to operationalize and implement the terms of the Consent Order, nor the incumbent PIRs. I note that the work on Jahn has been impeded by multiple transitions in ministry leadership and staff, as well as an election. Additionally, the recently passed correctional legislation that has not yet been proclaimed into force,

Overall, the ministry’s timelines for policy reform and operational implementation remain unclear. There are significant compliance issues spanning unresolved tracking, data integrity and implementation issues, as well as an absence of evidence demonstrating operational change. Operational context rather than a commitment to an overall legal human rights framework appears to have shaped and limited policy development. However, the empirical evidence supporting many concerns about compliance has not been provided. That said, there is evidence that some local institutions and correctional staff—in the absence of clear policy—are creatively trying to accommodate individuals. These local best practices, however, are not being captured or effectively used by Ontario.

Segregation remains a common practice in Ontario provincial prisons. Administrative segregation continues to be used for male, female, and transgender individuals, as well as for those with mental health concerns who may show signs of or have disclosed thoughts of self-harm or suicide. The data disclosed in this report includes remanded and sentenced individuals. Because the harms of segregation do not discriminate based on custodial status and are not predictable, my comments throughout this report apply to both populations of individuals. Furthermore for those in remand detention, being in segregation likely further contributes to a decision to plead guilty in advance of a trial date, and for this reason, should be used, as stipulated by international law and provincial legislation, as a measure of absolute last resort. More importantly, it should be prohibited for those with serious and/or identified mental

The human rights-based data collected for schedule B-15 (the requirements are discussed below) show that Ontario has not substantially reduced its use of segregation to date. Between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, there were 24,220 segregation placements. Of the 12,059 individuals included in the review, 1,900 identified as female and 10,159 identified as male.

| Presence of an alert | Individual - female | Column % - female | Individual - male | Column % - male | Individual - total | Column % - total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total individuals | 1,900 | 100.0% | 10,159 | 100.0% | 12,059 | 100.0% |

| MH alert1 | 1,099 | 57.8% | 4,459 | 43.9% | 5,558 | 46.1% |

| Suicide risk alert**,2 | 729 | 38.4% | 3,549 | 34.9% | 4,278 | 35.5% |

| Suicide watch alert3 | 317 | 16.7% | 1,648 | 16.2% | 1,965 | 16.3% |

*Excludes intermittent sentences.

**Suicide Risk Alert includes Suicide Watch Alerts, Enhanced Supervision, and Previous Suicide Attempt.

1 Yates' chi-square = 297.345, df = 1, p < .001

2 Yates' chi-square = 61.275, df = 1, p < .001

3 Yates' chi-square = 12.113, df = 1, p < .001

Of the 12,059 individuals covered in the review, 4,278 (36%) had a suicide risk alert recorded in their file. There were 729 women (38%) and 3,549 men (35%) in segregation who had a suicide risk alert, which is disproportionate to those in the general prison population, who in comparison have lower rates of suicidality. Specifically, 1,308 women (27%) and 6,292 men (20%) in the overall custody population had a suicide risk alert on file (Table 1).

Mental health, suicide risk and the use of segregation.footnote 66

Importantly, of the 24,220 placements that occurred between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019, there were 1,969 (8.1%) placements of 30 continuous days or longer. Of these, 1,259 placements (63.9%) were of individuals with mental health alerts on file; whereas 938 placements (47.6%) were of individuals with suicide alerts.

| Continuous days in segregation | Mental health alert on file - placement | Mental health alert on file - % row total | No mental health alert on file - placement | No mental health alert on file - % row total | Total - placement | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 30 days | 11,576 | 52.0% | 10,675 | 48.0% | 22,251 | 91.9% |

| 30 to 59 days | 730 | 65.0% | 394 | 35.1% | 1,124 | 4.6% |

| 60 to 89 days | 245 | 61.3% | 155 | 38.8% | 400 | 1.7% |

| 90 to 119 days | 104 | 57. 8% | 76 | 42.2% | 180 | 0.7% |

| 120 to 179 days | 88 | 68.2% | 41 | 31.8% | 129 | 0.5% |

| 180 to 239 days | 39 | 63.9% | 22 | 36.1% | 61 | 0.3% |

| 240 to 364 days | 39 | 69.5% | 17 | 30.4% | 56 | 0.2% |

| 365 or more days | 14 | 73.7% | 5 | 26.3% | 19 | 0.1% |

| Total | 12,835 | 53.0% | 11,385 | 47.0% | 24,220 | 100.0% |

*Excludes intermittent sentences.

**Chi-square = 109.884, df = 7, p < .001

| Continuous days in segregation | Suicide risk alert on file - placement | Suicide risk alert on file - % row total | No suicide risk alert on file - placement | No suicide risk alert on file - % row total | Total - placement | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 30 days | 9,285 | 41.7% | 12,966 | 58.3% | 22,251 | 91.9% |

| 30 to 59 days | 551 | 49.0% | 573 | 51.0% | 1,124 | 4.6% |

| 60 to 89 days | 179 | 44.8% | 221 | 55.3% | 400 | 1.7% |

| 90 to 119 days | 80 | 44.4% | 100 | 55.6% | 180 | 0.7% |

| 120 to 179 days | 61 | 47.3% | 68 | 52.7% | 129 | 0.5% |

| 180 to 239 days | 28 | 45.9% | 33 | 54.1% | 61 | 0.3% |

| 240 to 364 days | 29 | 51.8% | 27 | 48.2% | 56 | 0.2% |

| 365 or more days | 10 | 52.6% | 9 | 47.4% | 19 | 0.1% |

| Total | 10,223 | 42.2% | 13,997 | 57.8% | 24,220 | 100.0% |

*Excludes intermittent sentences.

**Chi-square = 29.574, df = 7, p < .001

| Aggregate days in segregation | Mental health alert on file - individual | Mental health alert on file - % row total | No mental health alert on file - individual | No mental health alert on file - % row total | Total - individual | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 60 days | 4,844 | 44.2% | 6,124 | 55.8% | 10,968 | 91.0% |

| 60 to 119 days | 453 | 64.1% | 254 | 35.9% | 707 | 5.9% |

| 120 to 179 days | 138 | 67.6% | 66 | 32.4% | 204 | 1.7% |

| 180 to 365 days | 123 | 68.3% | 57 | 31.7% | 180 | 1.5% |

| Total | 5,558 | 46.1% | 6,501 | 53.9% | 12,059 | 100.0% |

*Aggregate days are calculated based on the total number of days in segregation during the 365-day reporting period. The total number of aggregate days in segregation were counted to June 30, 2019.

**Excludes intermittent sentences.

***Chi-square = 182.375, df = 3, p < .001

| Aggregate days in segregation | Suicide risk alert on file - individual | Suicide risk alert on file - % row total | No suicide risk alert on file - individual | No suicide risk alert on file - % row total | Total - individual | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 60 days | 3,742 | 34.1% | 7,226 | 65.9% | 10,968 | 91.0% |

| 60 to 119 days | 341 | 48.2% | 366 | 51.8% | 707 | 5.9% |

| 120 to 179 days | 98 | 48.0% | 106 | 52.0% | 204 | 1.7% |

| 180 to 365 days | 97 | 53.9% | 83 | 46.1% | 180 | 1.5% |

| Total | 4,278 | 35.5% | 7,781 | 64.5% | 12,059 | 100.0% |

*Aggregate days are calculated based on the total number of days in segregation during the 365-day reporting period. The total number of aggregate days in segregation were counted to June 30, 2019.

**Excludes intermittent sentences.

***Chi-square = 99.827, df = 3, p < .001

Many of these individuals were admitted to segregation more than once during the same reporting period. While there were 6,994 individuals (58.0%) who experienced a single segregation admission, 5,065 (42.0%) of individuals had been placed in segregation two or more times. As well, 569 individuals (4.7%) experienced more than five segregation placements, and 90 individuals (0.75%) experienced more than 10 placements over the year of the reporting period, with 37 being the maximum number of placements per individual (Tables 6, 7 and 8).

| Number of placements | MH risk alert on file - individual | MH risk alert on file - % row total | No MH risk alert on file - individual | No MH risk alert on file - % row total | Total - individual | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 placement | 2,783 | 39.8% | 4,211 | 60.2% | 6,994 | 58.0% |

| 2 placements | 1,220 | 50.9% | 1,176 | 49.1% | 2,396 | 19.9% |

| 3 placements | 594 | 53.4% | 519 | 46.6% | 1,113 | 9.2% |

| 4 placements | 366 | 57.7% | 268 | 42.3% | 634 | 5.3% |

| 5 placements | 215 | 60.9% | 138 | 39.1% | 353 | 2.9% |

| 6 to 10 placements | 311 | 64.9% | 168 | 35.1% | 479 | 4.0% |

| 11 placements or more | 69 | 76.7% | 21 | 23.3% | 90 | 0.7% |

| Total | 5,558 | 46.1% | 6,501 | 53.9% | 12,059 | 100.0% |

*Excludes intermittent sentences.

**Chi-square = 325.911, df = 6, p < .001

| Number of placements | Suicide risk alert on file - individual | Suicide risk alert on file - % row total | No suicide risk alert on file - individual | No suicide risk alert on file - % row total | Total - individual | Total - % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 placement | 2,095 | 30.0% | 4,899 | 70.0% | 6,994 | 58.0% |

| 2 placements | 902 | 37.6% | 1,494 | 62.4% | 2,396 | 19.9% |

| 3 placements | 481 | 43.2% | 632 | 56.8% | 1,113 | 9.2% |

| 4 placements | 287 | 45.3% | 347 | 54.7% | 634 | 5.3% |

| 5 placements | 186 | 52.7% | 167 | 47.3% | 353 | 2.9% |

| 6 to 10 placements | 269 | 56.2% | 210 | 43.8% | 479 | 4.0% |

| 11 placements or more | 58 | 64.4% | 32 | 35.6% | 90 | 0.7% |

| Total | 4,278 | 35.5% | 7,781 | 64.5% | 12,059 | 100.0% |

*Excludes intermittent sentences.

** Chi-square = 321.991, df = 6, p < .001

| Number of placements | Individual - female | % - female | Individual - male | % - male | Individual - total | % - total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 placement | 1,109 | 58.4% | 5,885 | 57.9% | 6,994 | 58.0% |

| 2 placements | 391 | 20.6% | 2,005 | 19.7% | 2,396 | 19.9% |

| 3 placements | 184 | 9.7% | 929 | 9.1% | 1,113 | 9.2% |

| 4 placements | 83 | 4.4% | 551 | 5.4% | 634 | 5.3% |

| 5 placements | 43 | 2.3% | 310 | 3.1% | 353 | 2.9% |

| 6 to 10 placements | 73 | 3.8% | 406 | 4.0% | 479 | 4.0% |

| 11 placements or more | 17 | 0.9% | 73 | 0.7% | 90 | 0.7% |

| Total | 1,900 | 100.0% | 10,159 | 100.0% | 12,059 | 100.0% |

*Excludes intermittent sentences.

** Chi-square = 8.681, df = 6, p = .192

Overall, this data shows that prolonged segregation (15 days or longer) remains a routine practice for individuals with mental health and/or suicide risk alerts on file. These individuals also tend to have a high number of aggregate segregation days, and repeated segregation placements. At the very least, the above-mentioned findings reinforce the need for clarity in policies and procedures, meaningful review processes, and independent external oversight. The data above show that segregation practices function in a discriminatory manner:

- Table 1 demonstrates that, of those in segregation, women had a higher incidence of mental health alert, suicide risk alert, and suicide watch alerts than did their male counterparts.

- Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 indicate that, while most individuals are segregated for less than 30 continuous days and less than 60 aggregate days, the proportion of individuals with mental health alerts and suicide risk alerts are higher amongst those in prolonged segregation.

- Tables 6 and 7 show that, as the number of placements increased per individual, the likelihood of these individuals having a mental health and/or suicide alert on file also increased.

footnote 68

Reasons for segregation

The three most frequent reasons for segregation placement included: 7,627 (32%) occurrences where individuals requested to be placed in segregation; 6,631 (27%) placements as a result of medical reasons such as observation, isolation, and safety; and 5,332 (22%) placements as a result of an alleged or adjudicated misconduct.