Invasive species strategic plan (2012)

A strategic plan to prevent new invaders from arriving and surviving in the province, to slow or reverse the spread of existing invasive species and to reduce the harmful impacts of existing invasive species.

MNR 62788

ISBN 978-1-4435-9401-1 (Print)

ISBN 978-1-4435-9402-8 (PDF)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2012

Printed in Ontario, Canada

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec le ministère au

How to cite this manual:

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. July 2012. Ontario invasive Species Strategic Plan. Toronto: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. 58 pp.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

300 Water Street,

Peterborough, ON.

K9H 8M5

Photo: Ontario Tourism

Executive summary

Invasive species are a growing environmental and economic threat to Ontario. Invasive species are defined as harmful alien species whose introduction or spread threatens the environment, the economy, or society, including human health. Once established, invasive species are extremely difficult and costly to control and eradicate, and their ecological effects are often irreversible.

The current threats posed by invasive species in Ontario are significant. In response to these threats, Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources (LEAD), Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Ministry of the Environment, and Ministry of transportation developed the Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan. The objectives of this Strategic Plan are to prevent new invaders from arriving and surviving in Ontario, to slow and where possible reverse the spread of existing invasive species, and to reduce the harmful impacts of existing invasive species. This plan highlights work that has been undertaken, identifies gaps in current programs and policies, and outlines future actions necessary to meet the objectives of the Strategic Plan.

This Strategic Plan also emphasizes the need for collaboration and coordination with neighbouring jurisdictions (other Canadian provinces and U.S. states) and the federal government, especially in research, monitoring, and enforcement. To be successful in preventing the introduction and spread of invasive species, non-government organizations, stakeholders, municipal level government agencies, and members of the general public must also be involved. The Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan highlights some of the important work that has been undertaken by stakeholders and members of the public, and suggests further ways these partners can help fight invasive species.

Photo: Will Byman, MNR

A message from Minister Gravelle

Ontario is blessed with a spectacular natural environment. From the boreal forest and Hudson Bay tundra in the north to tallgrass prairie and carolinian forest in the south, our province has an amazing abundance and variety of natural wealth and beauty.

Within our borders are a quarter million lakes, untold rivers and more than 30,000 species of plants and wildlife. Vast forests cover two thirds of Ontario’s land mass.

This rich and diverse variety of life – our biodiversity – sustains us and our economy by providing clean air and water, productive soils, healthy food and renewable resources. These resources are the basis for industries like forestry, agriculture and recreation.

In Ontario, and elsewhere in the world, invasive species are an increasingly serious threat to biodiversity and the benefits that healthy ecosystems provide to us. Ontario’s diverse economy, growing population, and geographic location put us at the highest risk of species invasions compared to any other Canadian province or territory. We need to take decisive action now to address this serious situation.

The Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan provides us with specific actions and tactics to help prevent invasive species, detect and respond rapidly to the presence of new invaders, and effectively manage those that are already established in the province.

The Ministry of Natural Resources leads this provincial initiative, with support from the ministries of agriculture, Food and rural affairs; environment; and transportation. We will also be working with many other partners, including the federal government. Invasive species cross provincial and national borders, so it is important that we share information with our neighbours, and collaborate with them in research, monitoring, and enforcement.

We were pleased to work with our federal partners on the creation of the Invasive Species Centre in Sault Ste. Marie. This is the first centre in Canada to focus on the full spectrum of forest, plant and aquatic invasive species. It will improve collaboration and achieve efficiencies in the science, prevention, management and control of invasive species.

We will also work with municipalities, conservation authorities, aboriginal communities, and non–government organizations (such as farming, horticulture, recreational boating, and cottager) to build on the important work they are doing to control invasive species.

We’re fortunate in Ontario to have such an abundance and variety of natural wealth. The Ontario invasive Species Strategic Plan will help us keep it that way – for our own well-being and for the benefit of future generations.

Michael Gravelle, Minister of Natural Resources

A message from Deputy Minister David O’Toole

The Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan is an important step forward in Ontario’s efforts to confront the challenge of invasive species. The plan provides a comprehensive and integrated framework for the province to work with other government agencies and external partners, building on a foundation of sound scientific knowledge.

Invasive species are among the most serious threats to Ontario’s biodiversity and the wide range of goods and services that ecosystems provide for our communities and industries. Invasive species are not a new problem in Ontario, but many of the actions and tactics in this strategic plan reflect new approaches to this longstanding issue. For example, we will use risk analysis and risk assessment to focus the resources and actions of the ministry and its partners on the highest priority invasive species, pathways, and geographic areas.

While the Ministry of Natural Resources has been designated as Ontario’s lead agency for invasive species, this strategic plan reflects the broad network necessary to manage this issue, within the Ontario government, as well as nationally and internationally.

I am particularly proud of our commitment to build strong linkages for information sharing and collaborative action with a range of external partners, including municipalities, conservation authorities, aboriginal communities, and environmental organizations. We consulted broadly with stakeholders in preparing this plan, and we are confident it reflects broad consensus on the need for action.

I invite you to read the strategy presented in this document and to visit the Ministry of Natural Resources’ website regularly for updates.

Photo: Malcolm Storey

Photo: Matt Smith

Photo: Philip Thomas

Photo: USDA

Photo: George Schroeder

Photo: Matt Engel

Photo: Francine MacDonald, MNR

Photo credit: Laura Assinck

1.0 Introduction

Invasive species

The ecological effects of invasive species are often irreversible and, once established, they are extremely difficult and costly to control and eradicate. Significant threats are now posed by invasive species, and it is critical that Ontario take measures to address them. This Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan describes a wide range of actions and tactics designed to help the province prevent, respond to, and manage invasive species.

2.0 The need for a strategic plan

Water Soldier

Photo: Francine MacDonald, MNR

Canada’s national strategy

Invasive species affect every province and territory in Canada, and also cross international borders. Ontario, along with other provincial and territorial governments and the federal government, contributed to the development of "An Invasive Alien Species Strategy for Canada"

Ontario has also participated in the development of national action plans related to the management of certain specialized categories of invasive species, including the Canadian Action Plan to Address the Threat of Aquatic Invasive Species (DFO

The need for an Ontario perspective

The actions laid out in the national Strategy are at a strategic level and address concerns with invasive species across Canada. This Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan provides details on how Ontario will meet the goals set out in the national Strategy and national action plans. It also helps to inform priorities in provincial strategies aimed at control of particular species. Ontario’s commitments to address invasive species are reflected in documents such as, the proposed Ontario Government Plan to Conserve Biodiversity 2012 and Ontario’s Draft Great Lakes Strategy 2012. In addition to these, the renewed Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy, 2011 acknowledges that invasive species are a leading cause of biodiversity loss. Figure 1 illustrates the linkages between this Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan and other provincial, and national reports and initiatives. Section 3 describes the goals and objectives of this Strategic Plan; Section 4 describes its scope. Figure 2 provides a graphical overview of the goals and key actions in the Strategic Plan.

Why Ontario is at higher risk of new invasive species

Ontario has a higher risk of new invasive species entering and becoming established, compared to other regions in Canada. Historical data shows that Ontario has had more non-native species establish within its borders than other provinces and territories (see section above). Ontario has been and will continue to be susceptible to invasive species arriving and surviving due to the favourable environmental conditions and nature of our society (industrialized, urbanized, locally and globally mobile (and high population density) our economy (large quantities of imports, significant goods-producing industry sector), our geographic location (proximity to a major international shipping channel, the Great Lakes St. Lawrence Seaway, and multiple land and water entry points on Ontario’s borders), and the degraded habitat and ecosystems in many of Ontario’s ecological regions.

Ontario’s economy

Ontario’s high population supports an active, growing economy. Ontario imports more goods, from more places in the world, than any other province or territory, and ships many goods onward to other parts of Canada. This economic activity brings both benefits and risks. More trade increases the chances of invasive species arriving inadvertently, for example in packaging, in containers on ships, or in ballast water. In fact, approximately 64% of the overseas containers that arrive in Canada are opened in the Ontario portion of the Great Lakes basin.

Figure 1: Links to the Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan

- Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy 2011: Renewing Our Commitment

- Ontario Government Plan to Conserve Biodiversity

- Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan

- Environmental Commissoner of Ontario Annual reports

- Canada-Ontario Agreement Respecting Great Lakes Basin Ecosystem

- Ontario’s Draft Great Lakes Strategy 2012

- An Invasive Alien Species Strategy for Canada

Ontario’s society

A number of Ontario’s invasive species populations were first established where people have settled. In many cases these introductions have been the result of deliberate introductions. As our human population has grown over the last 200 years, so has the number of invasive species, a direct consequence of increasing urbanization, movement of people and goods around the globe, and improved transportation routes.

Ontario’s population is larger and has a higher density in some locations than any other province or territory. A high urban and suburban population can promote the arrival and spread of invasive species because of greater ecosystem disturbance and proximity to shipping and other transportation corridors. Because of its high population density, southern Ontario is at greater risk for invasive species introductions.

The introduction of invasive species has also been linked to global movement of people. For example, new invasive species may be stowed away with the personal belongings of visitors, and travelers. Some species which might end up establishing populations in Ontario may be legally imported for cultural purposes.

Transportation routes can also contribute to the spread of invasive species. In southern Ontario, high road density may be associated with increasing invasive species movements. Roads alter the landscape and act as pathways for the spread of invasive species.

Asian Soybean Rust

Photo: OMAFRA

Ontario’s ecosystems

Ecosystem resilience describes the ability of an ecosystem to cope with change. A strong and resilient ecosystem can better withstand, and recover from, stresses such as invasive species. Many ecosystems near urban areas are now degraded, and therefore have a higher probability of species invasions and associated negative impacts. Invasive species have had a profound impact on Ontario’s most fragile and threatened natural ecosystems.

Ontario’s geography also contributes to the spread of invasive species. The province has over 250,000 lakes, many of which are connected through natural streams and artificial canals. These connected waterways allow aquatic invasive species to spread to new water bodies, making it extremely difficult to control those species.

The invasive species problem in Ontario is the result of a complex combination of economic, social, geographic and environmental factors. An approach tailored to Ontario’s ecosystems and cultures is therefore needed to ensure these threats are effectively addressed.

The economic costs of invasive species in Ontario

Invasive species have had significant economic costs, both within Ontario, and nationally and internationally. At an international conference on invasive species held in Montreal in april, 2009, the trinational (Canada, U.S., and Mexico) commission for environmental cooperation confirmed that economic losses, and the costs of environmental impacts caused by invasive species, exceed $100 billion annually in the U.S. alone. There has been no analysis of net costs to Ontario for invasive species prevention, management, mitigation and associated research. However, there are several examples that illustrate the economic impacts in the province and the benefits of management action.

- The total impact of Zebra Mussels in Ontario is estimated to be between $75–91 million per year (Marbek, 2010).

- The city of Windsor has spent between $400,000 to $450,000 per year for activated charcoal treatment to eliminate taste and odour problems from municipal water supplies after Zebra Mussels invaded Lake St. Clair, upstream of the city’s water intake line (Colautti et al., 2006).

Zebra Mussels

Photo: Dave Britton, U.S. Fish & Wildlife

Emerald Ash Borer

Photo: Ed Czerwinski, MNR

- The Emerald Ash Borer has killed over one million trees in southwestern Ontario. The City of Toronto estimates it will cost $37 million over five years to cut and replace the city-owned trees that are killed by the emerald ash Borer (City of Toronto unpublished data). The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) has spent over $30 million and cut over 130,000 trees to slow the spread of the beetle (Canadian Food Inspection Agency unpublished data).

- Zebra Mussels have cost Ontario power producers $6.4 million per year in increased control/operating costs and about $1 million per year in research costs (Colautti et al., 2006).

- In 2004, the ministry and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) commissioned a study to examine the potential social and economic impacts of Chronic Wasting Disease, should the disease enter Ontario. The study concluded that the total economic costs of this disease to the agricultural and conservation community could be in excess of $22 million (OMAFRA unpublished data).

Eurasian Water Milfoil

Photo: OFAH

Phragmites

Photo: Janice Gilbert, MNR

- Invasive species can also have an economic impact on individual landowners. A recent study shows that property values were depressed by as much as 16.4% for shoreline residences in Vermont affected with eurasian Water Milfoil (Zhang and Boyle, 2010).

- the ministry has been involved in invasive Phragmites control pilot projects since 2007. This work focuses on the investigation of effective and efficient control options within sensitive coastal habitats such as wetlands and dunes. Projects are ongoing and some progress has been made within small, targeted, dry sites. Work to date demonstrates that control costs range between $865 and $1,112 per hectare (Gilbert et al., 2009a, Gilbert et al., 2009b).

- Invasive species also have significant potential to affect crops grown in Ontario. Examples of emerging agricultural pests include:

- The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug is an invasive alien species that was introduced to Pennsylvania in the mid 1990s and has since spread to over 35 states in cargo and vehicles. In Canada, the Brown Marmorated Stink Bug has not yet been found in any crops, although it has been intercepted in shipments of imported goods coming into several provinces, including Ontario. There have been over a dozen confirmed homeowner finds from 2010 to 2012 in the city of Hamilton, Ontario. It is likely only a matter of time before this insect shows up in Ontario’s farm fields. The Brown Marmorated Stink Bug has a very large host range that includes over 100 plant species, such as stone and pome fruit, berries, grapes, vegetables (corn, tomatoes, peppers), soybeans and edible beans, hardwood and ornamental trees, and woody shrubs. Extensive damage has been reported in commercial tree fruit in areas where this pest has reached high population levels.

- Spotted Wing Drosophila is a pest that can attack most temperate fresh fruits, including economically important fruits such as cherries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, and strawberries. This pest was first reported in california during the summer of 2008, and by 2009 was already causing serious economic damage in cherry trees and other stone fruit trees in that state. Spotted Wing Drosophila is readily spread through the fresh fruit for consumption pathway. It now appears to be well-established in the major fruit growing areas of the Western, Mid-atlantic and Great Lakes region of the United States, as well as the provinces of British Columbia, Ontario and Nova Scotia.

The ecological costs of invasive species in Ontario

Invasive species have a significant impact on Ontario’s natural biodiversity and its species at risk. An analysis of the factors affecting species at risk suggests that invasive species are a very significant threat, second only to habitat loss. Invasive species have been shown to affect about 20% of Ontario’s listed species

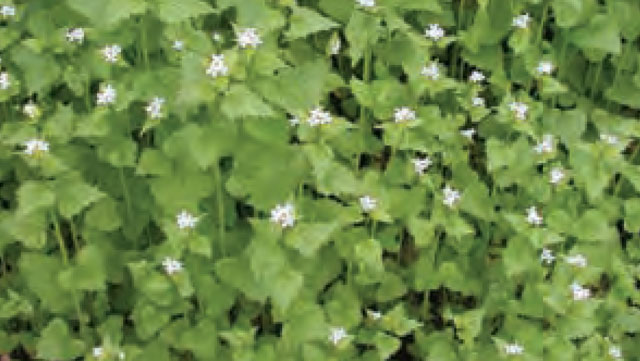

- Competition from garlic Mustard threatens several plant species at risk in Ontario’s carolinian forests, including american ginseng, Drooping trillium, False rue-anemone, Hoary Mountain Mint, White Wood aster, Wild Hyacinth and Wood Poppy. Garlic Mustard produces allelochemicals (chemicals produced by one plant that are toxic to another) that harm the growth of native plants, contributing to its ability to outcompete native species. In addition, garlic Mustard provides poor forage for wildlife, putting other plants at risk. For example, deer do not normally eat garlic Mustard, and will seek out other plants like american ginseng when the rest of the forest floor is covered by garlic Mustard.

- Currently eight freshwater mussel species in Ontario are listed as endangered and one as threatened (ministry website). In southern Ontario’s rivers, streams and lakes, Zebra and Quagga Mussels directly threaten these native mussels by colonizing their shells and smothering them. The impacts are particularly pronounced in the lower Great Lakes. Zebra and Quagga Mussels have virtually eliminated native mussels from Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River, leaving only small populations in a few refuges.

- Butternut canker is an invasive fungus that infects and kills healthy Butternut trees. The fungus quickly kills most trees it infects. The Butternut tree is now at risk in much of eastern North America. It is listed as an endangered species in Ontario under the Endangered Species Act.

- Invasive Phragmites has resulted in significant habitat losses for several species of wetland–dependent wildlife. Without effective control programs, declines are expected to continue to occur at an exponential rate (Bolton and Brooks 2010; Gilbert, MNR unpublished data).

- Significant changes to aquatic ecosystems have been documented as a result of the introduction of zebra and quagga mussels. These mussels filter out large amounts of phytoplankton. This filtering causes the water to become clearer allowing more sunlight to penetrate the water column. Changes in weed growth patterns occur and force some fish, such as walleye that are light sensitive, to find new habitat. In addition, when these mussels die and decompose, they add nutrients to the nearshore areas and this can cause nuisance algae blooms.these ecosystem alterations have caused problems for those who live in the coastal communities as well as industries and businesses that depend on these ecosystems.

Garlic Mustard

Photo: Wasyl Bakowsky, MNR

Success stories

Several examples drawn from monitoring, management, education, and regulatory initiatives show that action against invasive species can be successful. They demonstrate the importance of four factors: prevention, detection, rapid response, and effective management of invasive species. These factors are articulated as the strategic goals of the national Strategy, and also form the core goals of this Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan, as described in Section 3.0.

Cooperative research and monitoring

In 1992, the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre (CCWHC) was established through the support of the federal, provincial, and territorial governments. By implementing cooperative monitoring programs, CCWHC represents Canada’s best chance of detecting wildlife diseases that may have significant social, economic, and environmental implications, such as highly pathogenic avian influenza, White nose Syndrome (in bats) and Chronic Wasting Disease (in White-tailed Deer, elk, Moose, and caribou). The CCWHC works with the federal government, provinces, and territories to ensure that Canada’s wildlife disease and health monitoring and surveillance program is effective and efficient. The centre assists with disease risk assessment, surveillance and monitoring, diagnosing and investigating outbreaks, providing expertise, maintaining a central wildlife health database, and training wildlife management personnel in wildlife health management. The cooperative is an excellent example of a model where federal-provincial-territorial pooling of resources toward a common need has resulted in a highly cost effective program that addresses provincial, territorial and national interests.

White Nose Syndrome

Photo: Lesley Hale, MNR

Successful control and eradication

Galerucella beetles were approved for continent–wide release in 1992 by both the Canadian and U.S. governments to control Purple Loosestrife. With partner support from the University of guelph and the Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH) the first beetles were released in Ontario in 1993. To date, they have been released in over 400 locations across Ontario. Within ten years of the initial releases, the beetles had reduced the abundance of Purple Loosestrife in over 80% of the sites where they were released. The beetles continue to spread to other areas where Purple Loosestrife is established. The technique of collecting insects on sites where they were established for release at other sites, coupled with the beetles’ ability to spread naturally to nearby sites, has resulted in an extremely economical biological control for this invasive plant in Ontario.

The asian longhorned Beetle is a forest pest native to several asian countries that attacks and kills a wide range of hardwood trees. This invasive insect was found in an industrial park bordering toronto and the city of Vaughan in 2003. Upon discovery of the beetle, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency immediately initiated efforts to eradicate the insect, in partnership with the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Canadian Forest Service (CFS), City of Toronto, city of Vaughan, York region, toronto and region conservation authority, and the U.S. Department of agriculture. To date surveys show these efforts have been successful.

Education to change public attitudes and behaviours

Since 1992, the ministry has partnered with the OFAH to deliver the province-wide invading Species awareness Program, focusing on education and outreach, and programs designed to monitor the occurrence and distribution of invasive species. One of the program’s key activities is to communicate to anglers the importance of not dumping bait into lakes and rivers. The ministry and OFAH have conducted angler surveys every five years since the program was initiated, to determine whether it is having the desired impact. The results of the 2009 survey demonstrated a decline in the number of anglers that dump their bait and an increase in the number of boaters that clean their boat and equipment.

Education and awareness are particularly important because knowledgeable landowners, hunters, anglers, and outdoor enthusiasts play a critical role in the reporting and early detection of new invasive species. The detection and reporting of round goby in Pefferlaw Brook by a knowledgeable angler and the report of Kudzu by a local botanist illustrate success in this area. Another success story is the early detection of Water Soldier, an invasive aquatic plant species, in the trent-Severn system.

Eradication and control efforts are most successful when invasive species are detected early. The early detection of a few colonies of Water Soldier, in a relatively contained area, has been critically important in the Province’s efforts to eradicate this species. Similarly, early detection of asian longhorned Beetle was one of the factors that assisted agency efforts to eradicate this insect, before it spread to new geographic areas.

Yellow Floating Heart

Photos: Greg Bales, MNR

Effective regulation and enforcement

Ballast water has long been known to be one of the main sources for the introduction and spread of aquatic invasive species in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. In response, Canada and the United States have put in place stringent regulations governing ocean-going vessels and their ballast water. The 2006 regulations enacted by transport Canada, and the 2008 regulations enacted by the St. Lawrence Seaway Development corporation, require ocean-going vessels to flush their tanks with salt water before entering the St. Lawrence Seaway and the Great Lakes. All vessels entering the seaway are checked through a joint U.S./Canadian inspection program and compliance rates in 2009 were recorded at 97.9% (Great Lakes Ballast Water Working group, 2010). Any non-compliant vessels are dealt with on a case-by-case basis to ensure that unmanaged foreign ballast water is not released in the Great Lakes. Collectively, the Canadian and U.S. St. Lawrence Seaway regulations, along with monitoring, have significantly reduced the risk of aquatic invasive species entering via ship ballast tanks. If these regulations had been enacted earlier, they might have prevented many aquatic invasive species from entering the Great Lakes basin.

Red Mysid

Photo: GLERL

Sea Lamprey

Photo: OFAH

Spiny Waterflea

Photo: Scott Mcaughey, MNR

Northern Snakehead

3.0 Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan: Creating a framework

Dog Strangling Vine

Photo: Hayley Anderson, OIPC

A coordinated approach

To help meet the goals identified in the national Strategy, Ontario needs to establish provincial interests and clear objectives that will be supported with strong cooperation at all levels of government and with a wide variety of partners (e.g., OFAH and the Ontario Invasive Plant Council (OIPC), landscape Ontario), and which engage stakeholders and the public.

The ministry and OMAFRA have programs in place designed specifically to combat invasive species; MOE and MTO play a supporting role. Recognizing there was a need for coordinated action, the ministry took the lead and worked with OMAFRA, MOE, and MTO to develop this Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan. The plan highlights the work of these ministries, identifies gaps in current programs and policies, and outlines future actions necessary to address priority areas consistent with the goals of the national Strategy.

To be successful in preventing the introduction and spread of invasive species, non-government organizations (NGOS), stakeholders, industry, municipal governments, conservation authorities, aboriginal communities, and members of the general public must also be involved. The Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan highlights some of the work that has been undertaken by stakeholders and members of the public, and suggests further ways these groups can help fight invasive species.

Collaboration and coordination are themes that flow throughout this Strategic Plan. Recognizing the importance of this, Ontario and Canada have established the Canada-Ontario Invasive Species Centre (ISC) in Sault Ste. Marie. The ISC will provide an efficient and effective means for the governments of Ontario and Canada to work collaboratively on management and research of invasive forest, plant and aquatic species. It is envisioned that the Invasive Species Centre will assist in the delivery of many of the tactics that are identified in this Strategic Plan.

Goals and objectives of the Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan

The objectives of this Strategic Plan are to prevent new invaders from arriving and surviving in Ontario, to slow, and where possible reverse, the spread of existing invasive species, and to reduce the harmful impacts of existing invasive species. Ontario’s Invasive Species Strategic Plan is guided by four strategic goals (Figure 2), which are also articulated in the national Strategy:

Goals

Prevent

Prevent harmful introductions before they occur.

Respond

Respond rapidly to invasive species before they become established or spread.

Detect

Detect and identify invasive species before or immediately after they become established.

Manage and adapt

Implement innovative management actions and take practical steps to protect against impacts of invasive species.

Activities

To develop this Strategic Plan, the lead ministries identified existing programs and compared them to the needs identified in the national Strategy. Key actions and tactics for Ontario were developed to address gaps and strengthen current programs (Figure 2).

These are grouped under six activities:

- Leadership and Coordination

Effective leadership and intergovernmental coordination are essential for the prevention, detection, rapid response, and long-term management of invasive species, especially for invaders that cross or border on jurisdictional boundaries. - Legislation, Regulation and Policy

Laws and policies are the framework of rules that support invasive species management, setting out societal expectations for appropriate behavior, and sanctions to be imposed when laws are broken. - Risk Analysis

Risk analysis uses the best available scientific information to make sound decisions about how to prevent possible invaders, and manage those that have already arrived. - Monitoring and Science

Effective monitoring is essential for the detection of new invaders and to track the spread of existing invasive species. Research – the creation of new science knowledge – improves understanding of invasive species biology and supports. - Management Measures

Management measures include the development and implementation of best management plans and techniques to prevent, track, and manage invasive species in a given region. - Communication and Outreach

Communication and outreach are critical components of invasive species management. Ontario and its partners have worked hard to communicate the impacts of invasive species, and to educate Ontarians on what they can do to prevent invaders.

How this strategic plan will be used

This Strategic Plan will be used to assist in setting priorities for action by the lead ministries. Figure 2 illustrates the three desired outcomes of this plan:

- The impacts of existing invaders are reduced.

- new invaders are prevented from arriving and surviving.

- Where possible, the spread of existing invaders is halted.

The complexity of Ontario’s invasive species problem demands a significant number of actions and tactics, with implementation extending over a period of years. Each year, Ontario ministries will use the Strategic Plan to work with partners and stakeholders as appropriate to make decisions on key priorities for action.

This Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan will also provide a starting point for discussions with other key partners about priorities for implementation. The federal government in particular plays a key role in the prevention, control, and management of invasive species, so it is imperative that Ontario continues to work collaboratively with federal agencies. The Invasive Species Centre will play a significant role in the delivery of key actions in this Strategic Plan (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Delivery of the Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan

An invasive alien species strategy for Canada

Environment Canada (Lead)

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA)

- Parks Canada

- Natural Resources Canada’s Canadian Forest Services (NRCAN-CFS)

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO)

- Agriculture and Agri-food Canada (AAFC)

- Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA)

Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan 2012

Provincial ministries

- Ministry of Natural Resources (Lead)

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

- Ministry of the Environment

- Ministry of Transportation

Key partners

- Invading Species Awareness Program

- Ontario Invasive Plant Council

- Municipalities

- Conservation Authorities

- Universities

- Biodiversity Education and Awareness Network

- Other partners

The invasive species center

A Canada and Ontario partnership

The invasive species centre

In 2011, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the Canadian Forest Service and the Ministry of Natural Resources formally agreed to coordinate their efforts to deal with invasive species. A key mechanism for this coordination is the Invasive Species Centre, a not-for-profit entity established in Sault Ste. Marie by Canada and Ontario. The ISC is a regional centre focusing on Ontario and the Great Lakes, with linkages to adjacent provinces and Great Lakes states. Federal, provincial and local governments currently spend billions of dollars responding to invasive species outbreaks. The role of the ISC is to facilitate and improve coordination, collaboration and decision-making on invasive species issues, so available resources can be used in the most effective and efficient manner.

This Ontario Invasive Species Strategic Plan will also provide a starting point for discussions with other key partners about priorities for research and response. The federal government in particular plays a key role in the prevention, control, and management of invasive species, so it is imperative that Ontario continues to work collaboratively with federal agencies. The Invasive Species Centre will also play a significant role in the delivery of key actions in this Strategic Plan (Figure 3).

4.0 Ontario invasive species strategic plan: Scope

European Water Chestnut

Photo: Francine MacDonald, MNR

The national Strategy defines "invasive species" as "harmful alien organisms whose introduction or spread threatens the environment, the economy, or society." accordingly, the scope of this Strategic Plan is broad, and includes all groups of invasive organisms that are potentially harmful to Ontario. Invasive species that primarily impact human health will not be dealt with in this strategic plan as they are largely covered under existing human health programs. An example is West Nile Virus which is an invasive virus impacting human health. Due to its substantial impacts on human health, control and outreach programs to help address West Nile Virus are led by the Ministry of Health Promotion, and as such are out of scope of this Strategic Plan.

It is important to note that addressing the fundamental causes of invasions can sometimes prevent some future health problems. For example, it is possible that the source of the West Nile Virus strain detected in new York city in 1999, originated from an infected bird(s) from the Middle East

Some additional points of clarification may be helpful. First, a species can be considered invasive even if it is native to Ontario, provided it has been introduced by human activities into areas in Ontario beyond its natural range, and poses a threat to Ontario’s environment, the economy, or society including human health. A species may be considered invasive if its introduction or spread can be linked to our changing climate. On the other hand, a species whose range has expanded naturally (i.e., the range expansion cannot be attributed to human action) is not considered invasive in this Strategic Plan.

Many invasive species have become naturalized species in parts of Ontario; examples include Zebra Mussels, Quagga Mussels, and round goby. Naturalized invasive species are introduced species with self-sustaining populations unlikely to be eradicated that continue to pose a threat to our environment, economy or society. Managing naturalized invasive species involves measures to prevent their spread beyond existing ranges, developing techniques to adapt to their presence, and finding ways to reduce their impacts.

Examples of the types of invasive species that will be the focus of the strategic plan:

- a wide range of plants and animals (e.g., Zebra Mussels, Quagga Mussels, round goby, Phragmites, Purple Loosestrife, Japanese Knotweed, giant Hogweed, and Kudzu).

- invasive fungi and forest pathogens such as Butternut canker, Dutch elm Disease, White Pine Blister rust, Dogwood anthracnose, and thousand canker Disease of Black Walnut.

- animal diseases such as Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) in White-tailed Deer, elk, Moose and caribou, and White nose Syndrome in bats.

- Fish diseases such as Koi Herpesvirus (KHV). (note that the strategies to control invasive aquatic species will also help to address the spread of aquatic pathogens.)

- Forest insects such as the emerald ash Borer and Sirex Woodwasp.

- aquatic plant species such as Water chestnut and Water Soldier, which the province is working to eradicate.

- invasive species that may be found in bait buckets and live holding wells (e.g., pathogens, invasive fish, and aquatic plants) and released into natural areas.

Emerald Ash Borer

Photo: Patrick Hodge, MNR

White Pine Blister Rust

Photo credit: Patrick Hodge, MNR

Some examples of invasive species that are native to Ontario:

- Smallmouth Bass if introduced into lakes in the arctic watersheds through unauthorized releases to create fishing opportunities.

- Manitoba Maple, which is native to southwestern Ontario but has now spread to other parts of the province.

Purple Loosestrife

Photo: Jay Callaghan, OFAH

Status of some Ontario invasive species

- Control

Purple Loosestrife arrived in Canada in the early 19th century. It is considered invasive as it forms dense monocultural stands over very large areas, threatening wetland habitat and communities. In 1992 the Canadian and U.S. governments approved the release of leaf-feeding beetles, galerucella calmariensis and g. pusilla, to control this invasive plant. Although Purple Loosestrife will never be eradicated, these insects have been effective in reducing loosestrife populations and enabling native vegetation to become reestablished. Despite this successful control program, Purple Loosestrife is still considered invasive. - Adapt

The Zebra Mussel was first collected in Lake St. Clair in 1988. Since then it has spread to all the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River and to many inland lakes and streams. The Zebra Mussel is considered invasive since it harms the native fish community, causes significant costs to industrial and municipal water users, and affects shoreline property owners and recreational boating. Although there are ongoing efforts to find a mechanism to control Zebra Mussels, it is unlikely that this species will be completely eradicated from Ontario’s waters due to its wide distribution. - Prevent

Smallmouth Bass are considered to be a popular recreational fish species in Ontario. Native to central North America, in Ontario the species was originally restricted to the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence system. Smallmouth Bass are valued as sport fish, and as early as 1901, efforts were made to extend its range into more northerly lakes to improve angling opportunities there. Today, there are 2,421 Ontario lakes and numerous streams and rivers known to contain Smallmouth Bass. Recent research demonstrates that the introduction of Smallmouth Bass to a new lake causes negative impacts on other sport fish such as lake trout. Smallmouth Bass are not native to Ontario’s arctic watersheds and the ministry is now working to prevent the species from invading those regions, for example by better communicating rules prohibiting the unauthorized release of any live fish into Ontario lakes or rivers. - Control and Prevent

White Mulberry was introduced to North America in the late 1800s from asia for its edible fruit and to provide leaves for the silkworm industry. White Mulberry hybridizes with the native red Mulberry and is contributing to the decline of red Mulberry. This is of particular concern because the red Mulberry is an endangered species in Canada, found only in the few remaining fragments of carolinian forest in southern Ontario (Environment Canada, 2006). - Control and Prevent

Invasive fungi and forest pathogens (e.g., Butternut canker, Dutch elm Disease, and White Pine Blister rust) can severely impact native species by damaging or killing their hosts, damaging major forest ecosystems, and eliminating populations of native species. Of the six tree species listed as endangered in Ontario, three (Butternut, Dogwood, and chestnut) are endangered due to invasive forest diseases: Butternut canker, Dogwood anthracnose and chestnut Blight. It was recently determined that 100% of the Butternut trees found in charleston lake Provincial Park are infected with Butternut canker (Barkley, 2005). Similarly, White Pine Blister rust is a concern in protected natural areas such as Quetico Provincial Park (the Quetico Foundation, 2006).

Geographic scope

The geographic scope of this Strategic Plan is provincial. However, given the geographic distribution of invasive species and pathways, some of the identified actions will take place at a local scale. For example, certain areas of the province, such as those adjacent to identified ports of entry, may require different actions than those located much farther away from these key ports.

Pathways for introduction

Humans have been responsible for the movement of a large number of species over great distances. This Strategic Plan will address only those invasive species that have been transported outside their natural range as a result of human actions.

Humans move invasive species both intentionally and unintentionally. The following are some examples of these pathways:

- Unintentional – e.g., ballast water; species attached to recreational boats; movement of forest pests in firewood; spread of an invasive horticultural plant from an urban garden into a natural area; pallets and wood packaging material; escape of fish from the aquaculture trade; creation of stream connection channels; movement of equipment (e.g., all-terrain vehicles, forestry equipment, tractors used in agriculture, roadside maintenance, etc.) from a site with invasive species such as the Bulb and Stem nematode and Soybean cyst nematode to a new site, without cleaning the equipment; movement of gravel/sediment/topsoil without decontamination; escape of non-native wildlife in captivity (zoos, game farms); movement of diseased wildlife parts as a source of introduction of wildlife diseases.

- Intentional – e.g., dumping of bait buckets; pond owners deliberately releasing their stock into public waters; anglers deliberately releasing fish into public waters to create new fisheries; deliberately releasing invasive species obtained through the horticultural and pet trades. Intentional introductions can be either authorized or unauthorized.

- Authorized – e.g., introduction of Mosquito Fish to control mosquitoes; lawful stocking of grass carp in the U.S. to control nuisance aquatic vegetation and as a food fish; release of aquatic invasive plants into waterways; and planting terrestrial invasive plants into areas where they can spread.

- Unauthorized but intentional – e.g., illegal introduction of White Perch to create an angling opportunity.

Range expansion due to climate change

Climate change is likely to increase the rate of new invasions into Ontario and promote the spread of already-established species (rahel and Olden 2008). The introduction or spread of a species which can be linked to our changing climate may be considered invasive under this Strategic Plan.

A warming climate will increase environmental stresses, and may result in less resilient ecosystems that are unable to combat invasive species. This Strategic Plan presents specific actions that can help Ontario manage and control invasive species in the context of a changing climate. For example, monitoring, eradication and control efforts must consider not only current conditions, but also how the future climate of a region could affect the spread and management of invasive species. Similarly, risk assessments may need to include analyses of our changing climate. Ontario has released the report Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan, which contains many references to the impacts of climate change on invasive species, and actions that support the goals of this Strategic Plan.

5.0 Strategic plan: Actions and tactics

Silver Carp

Photo: Ted Lawrence, GLFC

This section analyzes existing activities related to invasive species prevention, detection, rapid response, and management. It identifies gaps, and proposes strategic actions to achieve the goals of this Strategy. As mentioned in Section 3, strategic actions are described under six main categories:

- Leadership and coordination

- Legislation, regulation and Policy

- Monitoring and Science

- Risk analysis

- Management Measures

- Communication and education

Each action lays out one or more tactics – activities that can be undertaken immediately or over time, to achieve the goals of this Strategic Plan.

Emerald Ash Borer

Prevent

Preventing harmful introductions before they occur is the most effective means to avoid the risk of invasive species arriving in Ontario. Investments in prevention are cost effective as they avoid the economic, environmental and social costs of invaders.

Detect

When prevention measures are not effective and invasive species enter Ontario, it is essential to detect and identify them before or immediately after they become established.

Respond

When invasive species circumvent prevention measures and become established in Ontario, it is essential that we respond rapidly before they become established or spread and cause harm to the economy, environment, or society.

Manage and adapt

In those cases where invasive species have established self sustaining populations such that control and eradication efforts are not feasible, it is essential that we implement innovative management actions which minimize their impacts and long-term costs. Adaptation means taking practical steps to protect communities from the disruptive and damaging impacts that invasive species may have on society.

5.1 Leadership and coordination

Effective leadership and intergovernmental coordination are essential for the prevention, detection, rapid response, and long-term management of invasive species. This is especially important for invaders that cross or border on jurisdictional boundaries. For example, coordination between Canada Border Services agency (CBSA) and the ministry played an important role in recent enforcement actions that prevented the shipments of live asian carp into Canada. Provincial ministries currently work collaboratively with federal departments, other provincial ministries, and a variety of other partners. The strategic actions listed below are intended to enhance the present level of coordination and leadership.

Leadership and coordination are required at all levels of government. This section begins with actions and tactics intended to clarify the roles and responsibility of federal and provincial agencies. The Great Lakes, which are shared by Canada and the United States, present special challenges and opportunities in the management of invasive species. This section contains describes activities centered on that system. Communication networks and existing committee structures should also be reviewed and strengthened; additional actions and tactics set out how that should be accomplished.

5.1.1 Clarify roles and responsibilities of federal and provincial agencies

Action 1: Identify federal lead departments and agencies and clarify roles and responsibilities for invasive species issues

The national Strategy recognizes the Ministers of Fisheries and Oceans, agriculture and agri-Food, natural resources, and environment as the key leaders at the federal level on invasive species. While Environment Canada has been assigned the overall lead role, each agency has a variety of activities underway to prevent and manage invasive species. There is therefore a need for Ontario to clarify the roles and responsibilities of federal departments and agencies, and establish clear leadership for invasive species at the federal level.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

Action 2: Clarify roles and responsibilities of provincial ministries for invasive species issues

As noted in Section 3.0, four Ontario ministries (MNR, OMAFRA, MTO, and MOE; see table 1) have roles in the management of invasive species, but in the past there has been little coordination of activities among these agencies. This Strategic Plan confirms the ministry as the lead and proposes the establishment of formal communication and coordination mechanisms designed to clarify roles and responsibilities and improve the Province’s ability to prevent and respond to invading species (see table 1).

Table 1: Areas requiring clarification among provincial ministries

| Invasive species | Lead ministries | Areas requiring clarification |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial invasive species issues | All | Establish program leads within each ministry |

| Invasive agricultural animals, animal and plant pests and diseases | OMAFRA and MNR | Establish clear responsibilities for the ministry and OMAFRA for dealing with invasive animals and plant pests and diseases that affect animals and plants in agricultural and non-agricultural ecosystems. |

| Invasive non-forest and Non-agricultural plants and plant pests (e.g., Purple Loosestrife) | MNR and OMAFRA | Clarify respective roles of ministries with parallel responsibilities that relate to non-agricultural and non-forest plants and plant pests. |

The ministry has been identified as the lead ministry in Ontario, and has primary responsibility for establishing these mechanisms. Within the ministry, Biodiversity Branch has lead responsibility, many branches and regions are also either actively engaged in work related to invasive species or have varying interests in addressing threats posed by invasive species. Increased awareness and engagement across a broad array of program areas is required in the ministry. This is especially important to facilitate rapid response once an invasive species has been detected and reported.

| Ministry tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

| OMAFRA tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

Dog Strangling Vine and flower

Photo: Ken Towle

5.1.2 Improve communication and coordination

A number of committees, conferences, and workshops currently provide informal ways for agencies and individuals in Canada, the U.S., and Mexico to work together on invasive species. Some of these include the Great Lakes Panel on aquatic nuisance Species (see section 5.1.1), and the North American Plant Protection Organization (NAPPO), whose meetings OMAFRA regularly attends. Some of these groups are regional in perspective, while others are national or international. For example, the ministry participates in the northeastern Forest Pest council, an annual meeting of forest pathologists, entomologists, foresters and scientists interested in forest health of north eastern North America, and the northcentral Forest Pest Workshop, an annual workshop of forest pathologists, entomologists, foresters and scientists interested in forest health of north central North America.

While these forums serve an important purpose, they are informal and often limited in geographic or topical scope. More formal, structured communication mechanisms would ensure more consistent communication across a wider range of issues and geographic areas.

Action 3: Establish formal mechanisms to ensure effective communication and coordination across jurisdictions and levels of government

Establishing an effective communication network among Ontario ministries, the federal government, and neighbouring states and provinces would be a powerful way to share new science and management techniques, including notification of the arrival of new invasive species, or changes in the range of existing species.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|  |

|     |

|     |

Action 4: Build an effective communication network with municipalities, conservation authorities, Aboriginal communities, NGOs, and other key stakeholders

Municipalities, conservation authorities, aboriginal communities, and many private and non-government organizations are also active in the management of invasive species, and have many relevant programs in place. There is a need to build stronger linkages to these groups, to improve coordination and communication, avoid duplication of effort, and ensure the most effective use of available resources for early detection, rapid response, and effective management of invasive species.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

The Ministry, working with OMAFRA and MOE, will propose mechanisms to:

|     |

|     |

|     |

|     |

Photo: Francine MacDonald, MNR

5.1.3 Improve the effectiveness of existing committees

Invasive species issues are complex and, as mentioned previously, many committees have already been established to work on particular aspects or activities. The challenge is to coordinate the work of these committees, and ensure that available resources are used to the best possible advantage. The national Strategy recommends the establishment of an inter-jurisdictional coordination mechanism with representatives from provinces, territories and responsible federal departments and agencies. Some inter-jurisdictional coordination mechanisms are already in place and serve as a forum for the discussion of invasive species issues. Examples include the Canadian Wildlife Directors committee, the national aquatic invasive Species committee, the International Joint commission (IJC), the Canadian Council of Fisheries and aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM), and the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers (CCFM).

Action 5: Improve the effectiveness of existing committees through clear mandates, regular meetings, and a focus on invasive species

Wildlife committees

The Canadian Wildlife Directors committee provides a forum for the discussion and resolution of issues affecting Canada’s wildlife. However, the committee’s mandate extends across many issues, not just invasive species, and its scope is national. The committee should be encouraged to include invasive species in its regular discussions, and should consider establishing a subcommittee focused on invasive species in our region.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

Forest and plant pests committees

The Canadian Council of Forest Ministers’ (CCFM) Forest Pests Working group provides a forum for ongoing discussion and collaboration between federal, provincial and territorial forest pest management agencies in Canada. The ministry is a member of this committee and participates regularly in its activities. The development and implementation of a National Forest Pest Strategy (NFPS) is central to the role of this CCFM Working group. The NFPS, which is based on a risk analysis framework, provides for a coordinated approach to forest pest prevention, detection, control and mitigation of impacts. The NFPS focuses on both native and invasive alien forest pests.

The critical Plant Pest Management committee provides a forum for the ministry, OMAFRA, CFS, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and CFIA to discuss plant pests, including those affecting agriculture, at a strategic level. Meetings are held pursuant to a Memorandum of Understanding for the Prevention, Eradication, Control and Management of Critical Plant Pests.

Gypsy Moth

Photo credit: Patrick Hodge, MNR

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

Aquatic invasive species committees

The interconnectedness of lakes and streams can allow aquatic invasive species to move freely from one body of water to another, and the Great Lakes system is no exception. Canada shares the Great Lakes and their connecting channels with the United States, so many Ontario activities targeted at managing aquatic invasive species are undertaken in partnership with the federal government and/or binational committees and forums.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

|     |

|     |

Goldfish

Photo credit: Emily Funnel, Ontario Streams.

Great lakes – leadership and coordination

Inter-jurisdictional discussions on Great Lakes issues, including invasive species, occur in a number of ways. The International Joint Commission (IJC) provides a forum for Canada, the United States and their respective Great Lakes provinces and states to discuss concerns about water quality and quantity in the "boundary waters" – the lakes and rivers shared by Canada and the United States. The IJC has established a number of advisory Working groups. One of those groups has produced a report entitled "Binational aquatic invasive Species rapid-response Policy Framework".

The Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA), first signed in 1972, commits Canada and the United States to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes Basin ecosystem. It includes a number of objectives.

The Great Lakes Protection Act is proposed legislation that, if passed, would help restore and protect the Great Lakes so they stay drinkable, swimmable, fishable, for present and future generations. Ontario’s Draft Great Lakes Strategy is intended to describe how Ontario will focus a variety of tools to take action to achieve Great Lakes goals – through existing laws and programs, the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2012 (if passed), the Canada–Ontario agreement respecting the Great Lakes Basin ecosystem (COA), and other partnership and collaboration with many partners across Ontario and across the Great Lakes.

The Canada-Ontario Agreement respecting the Great Lakes Basin ecosystem (COA) is an agreement between the governments of Canada and Ontario to restore and protect the Great Lakes Basin ecosystem. COA is the primary mechanism through which Canada meets its obligations and commitments under the GLWQA. Reducing the threat of aquatic invasive species to the Great Lakes is a goal of the current COA.

The Great Lakes Fishery commission, provides a binational forum for fisheries management in the lakes. Its five lake committees contribute to the development of management plans for their respective lakes. Some of these have aquatic invasive species on their agenda; some have aquatic invasive species forums. The lake Superior lakewide Management Plan incorporates the Lake Superior Aquatic Invasive Species Complete Prevention Plan. It outlines the actions, beyond those already underway in Canada and the U.S., necessary to prevent new aquatic invasive species from entering and becoming established in the lake Superior ecosystem.

A variety of other committees support discussions on Great Lakes issues, including invasive species. These include the Great Lakes Fish Health committee, the council of lake committees, the council of Great Lakes Fisheries agencies and the law enforcement committee. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, through the Great Lakes commission (GLC), supports a Great Lakes Panel on aquatic nuisance Species, a forum to discuss activities (legislation, education, outreach, etc.) regarding aquatic nuisance species by Great Lakes states. Canada, Ontario and Quebec participate on this panel.

Finally, Ontario works actively with the federal government through forums such as the Canada–Ontario Fisheries advisory Board (CONFAB) and national bodies such as the Canadian Council of Fisheries and aquaculture Ministers (CCFAM) to address aquatic invasive species issues.

Rusty Crayfish

Photo: Doug Watkinson, DFO

Action 6: Identify gaps with respect to existing inter-jurisdictional committees and work with the federal government to establish additional committees as required

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

5.2 Legislation, regulation and policy

Ontario and Canada have several laws addressing issues associated with invasive species. For example, regulations controlling the use of cosmetic pesticides provide for application of pesticides where a plant is "poisonous to the touch", for example the invasive species giant Hogweed. Another example would be the Provincial Weed Control Act, where the definition of "weed" can be interpreted as including invasive plant species impacting agriculture.

While there is no single federal or provincial piece of legislation that deals comprehensively with the prevention and management of invasive species, federal and provincial agencies use a range of regulatory tools to address threats posed by invasive species. As part of good management practice, ministries need to review existing legislation periodically to ensure the legislative and policy framework for invasive species is effective and provides for sound management of current and emerging issues.

Action 7: Examine provincial legislative and policy framework for invasive species management

A number of initiatives have involved reviews of federal and provincial legislation. These reviews should be compiled and analyzed to determine where information needs to be added or updated. Based on the outcome of that analysis, the ministry and OMAFRA should examine ways of addressing any identified gaps. Solutions should evaluate options from a variety of perspectives (e.g., environmental, socio-economic), reduce duplication of effort, and avoid regulatory conflict, while also distributing effort across interested agencies and levels of government.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

Action 8: Support and strengthen existing legislation

It will take some time to complete the above analyses. In the interim, provincial ministries will continue with a number of key activities related to the implementation and strengthening of existing legislation. As an example, the provincial Animal Health Act, proclaimed on January 21, 2010, enables OMAFRA to develop regulations concerning the biosecurity of farmed animals, including measures to prevent disease transmission between farmed animals and wild animals. In addition, the federal government, provinces, neighbouring states, and the United States government have collaborated for some time on the development of measures for the treatment of ballast water from ocean-going vessels. Ballast water can be a major vector for the introduction of aquatic invasive species into the Great Lakes and other major water bodies.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

|  |

Mute Swans

Photo: Istock

Action 9: Review and enhance invasive species policies

Ontario currently has a number of policies and guidance documents targeted at specific activities through which invasive species may be introduced or spread. For example, the Stand and Site Guide provides specific direction to forest managers on preventing the spread of invasive species. Similarly, the Ontario Tree Marking Guide provides guidance on the removal of trees infected by introduced diseases such as White Pine Blister rust and Beech Bark Disease. Additional policies or guidance may however be necessary to support the management of particular species, pathways, or programs. As one example, it would be helpful to supplement existing guidance documents with new rules requiring the planting of native tree species for government projects. The breadth of invasive species issues means that a number of Ontario ministries may be able to contribute to the identification of these kinds of gaps and needs.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

|     |

Action 10: Enhance enforcement of invasive species legislation, regulations, and policy

Existing invasive species legislation must be enforced to be effective. Invasive species extend across political borders, so inter-jurisdictional and interagency collaboration is especially important in this regard. Federal agencies such as Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) play a central role in enforcement at border crossings, which are potential entry points for the introduction of banned species. Enforcement is however much more difficult in the case of new pathways such as mail order via the internet. It is not clear how internet sales of potential invaders could be monitored, or associated invasive species regulations enforced.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|   |

|   |

Action 11: Develop rapid response protocols that respond to new infestations

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|   |

|   |

|  |

|  |

Giant Hogweed rash

Photo: King County Noxious Weed Control Program, Seattle.

Ontario ministries are already working with provincial, federal, and international partners to develop rapid response protocols for use when a new invasive species is detected in a given area. This work should continue, ensuring that rapid response plans clearly outline roles of all parties and designate a lead to carry out each plan. Rapid response protocols should be developed with an understanding of the social, economic and environmental impacts associated with invasive species. The lead ministry/agency would be responsible for coordination with its counterpart ministries, federal agencies and partners.

Action 12: Identify legislative and policy obstacles to effective prevention, rapid response and management

Occasionally, existing legislation or policies may present obstacles to effective prevention, rapid response, and management of invasive species. For example:

- Restrictions on certain pesticides may limit our ability to eradicate invasive aquatic plants such as Phragmites.

- Obtaining permits to apply pesticides can make it challenging for individuals to respond promptly to invasive species infestations.

- Federal Pest Management regulatory agency labeling requirements stipulate that invasive species must be listed on pest control product labels before the chemical can be applied to those species.

The Pest Management regulatory agency has an emergency registration process where products can be registered for up to one year to address emergency issues. Although Ontario has successfully used this process, there are hundreds of invasive species already present in Ontario, and the listing process can be time consuming.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

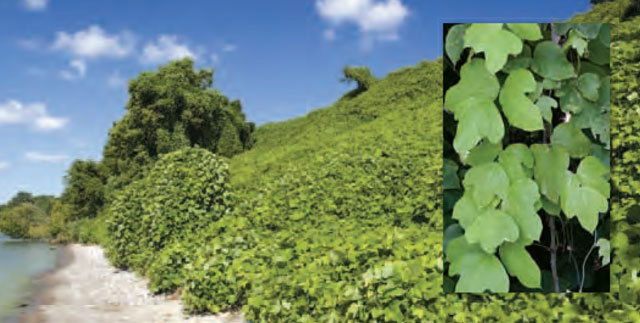

Invasion of Kudzu

Photo credit: Sam Brinker; inset: Rachel Gagnon, OIPC

5.3 Risk analysis

With so many invasive species and pathways to consider, it makes sense to establish priorities. This is done through a scientifically-based process called risk analysis. Risk analysis includes:

- Risk assessment, which uses the best available scientific information to estimate the likelihood of an invasive species being introduced and evaluate the potential consequences of introduction. The likelihood of a potential introduction may be determined based on species biology, environmental conditions, and pathways used for pest movement. The consequences can be measured in biological and socio-economic terms.

- Risk management refers to the management approaches taken to lower invasive species risk to an acceptable level. Risk analysis involves evaluating different risk management options, and determining which is the most appropriate for a given species and pathway.

- Risk communication means working with the public and other stakeholders to convey the results of risk assessment and help people make more informed decisions about the products they use and the ways they behave.

Risk analysis is a way of making scientifically sound decisions about how to prevent possible invaders, and manage those that have already arrived. Yet because scientific information is never complete, it is important to identify sources of uncertainty in the analysis – to consider the quality and quantity of data available to estimate the probability and magnitude of risk. Evaluating uncertainty provides managers with an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the risk analysis. Uncertainty will always be higher for poorly known, poorly studied species.

Ontario and its partners are engaged in a variety of risk analysis activities related to invasive species, for example:

- Ontario is preparing a Provincial animal Health Strategy, which includes standards for risk assessment.

- Ontario has an introductions and transfers committee, which conducts risk assessments for the planned introduction and transfer of new aquatic species through aquaculture and fish stocking.

- The federal government has conducted a number of formal risk analyses on species of concern to Ontario (e.g., asian carp, Sudden Oak Death, emerald ash Borer, asian longhorned Beetle, Pine Shoot Beetle, and Soybean rust).

Dogwood Anthracnose

Photo: Eric Cleland, MNR

Action 13: Increase capacity to develop and implement risk assessment and risk analysis tools

Risk assessment is a fairly new tool in the management of invasive species. Ontario needs to build its capacity to develop tools for risk assessment and analysis, and apply them in the prevention and management of invasive species. Much of this work will be done in partnership with other levels of government, especially the federal government. Nevertheless, there is a need to build tools and approaches tailored for Ontario’s ecosystems.

| Tactics for consideration by the federal government | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

|     |

|     |

|

| Tactics for the Ontario Government | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

|     |

5.4 Monitoring and science

Effective monitoring is essential for the detection of new invaders and to track the spread and impact of existing invasive species. Ontario’s monitoring programs extend across a wide variety of activities and several Ontario ministries. Ontario’s monitoring activities need to be better coordinated with neighbouring jurisdictions as well as the federal government.

Research – the creation of new scientific knowledge – is also important in the prevention and management of invasive species. Research is currently underway to identify species that may become invasive, to develop rapid response protocols, and to understand the conditions governing the spread of invasive species.

Rainbow Smelt

Photo: Mark Gautreau

5.4.1 Monitoring

Ontario has a number of programs in place to monitor the spread of existing invasive species and detect new invaders. Some examples of these programs include:

- The ministry has a partnership with OFAH to deliver the province-wide invading Species awareness Program. Through this partnership, the invading Species awareness Program staff monitor and track the spread of invading species through reports to the invading Species Hotline.

- Ontario’s forest health monitoring program conducts on-the-ground and in-the-air monitoring of Ontario’s forests to assess pest infestations including native and introduced insects and diseases.

- Conservation authorities and municipalities play a significant role in the monitoring and tracking of aquatic and terrestrial invasive species.

- The Ministry of Natural Resources has implemented an inland lakes broadscale monitoring program. Through this program, the ministry is monitoring inland lakes for invasive fish species, as well as Zebra Mussels and Spiny Waterflea.

- In partnership with federal and all provincial and territorial governments, Ontario supports the work of the Canadian Cooperative Wildlife Health Centre to monitor for significant wildlife diseases.

Monitoring programs must be designed to make the best possible use of available resources, avoid duplication of effort, and focus available resources on areas and species of highest risk.

Action 14: Undertake surveillance activities in geographic areas at high risk of invasive species introductions

A high priority action identified in the national Strategy is to undertake surveillance in high-risk geographic areas and points of entry. The national Strategy also emphasized monitoring of authorized introductions to ensure that no unpredicted impacts occur. Many high-risk areas are at border locations or in transboundary waters, so the federal government has a central role, especially in surveillance activities that cross jurisdictional borders.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|     |

|     |

|     |

Action 15: Improve existing invasive species monitoring programs and develop a network of experts to identify species

While many monitoring programs are already in place to track the arrival and spread of invasive species, our understanding of vectors and pathways is always evolving. It is important to build the strongest possible monitoring network, using the most current knowledge and tools, to protect Ontario against invasive species. Technical expertise and laboratory capacity for the identification of invasive species must also be developed.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

Action 16: Strengthen data management and reporting for invasive species

Monitoring programs generate large quantities of data, often covering a wide geographic area, multiple species, and lengthy time periods. Invasive species cross jurisdictional boundaries, so it is also important to be able to share monitoring information with neighbouring provinces and states, and with the federal government. Effective data management avoids waste and improves our ability to detect and respond to invasive species.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|    |

|    |

|    |

|    |

Action 17: Engage science support to design appropriate surveillance protocols

Section 5.4.2 describes how scientific research can support the prevention, detection, rapid response, and effective management of invasive species. One of the most important ways research can be applied is in the development of surveillance protocols that are appropriate for particular species, geographic regions, or pathways.

| Tactics | |

|---|---|

|  |

Spiny Waterfleas

Photo: Andrea Miehls, Michigan State University

5.4.2 Science

Ontario has a number of research programs and partnerships in place to assess the impact of invasive species on the biodiversity of ecosystems and assist in the development of management tools. Some examples of these programs include:

- Through Invasive Species Centre funding contributions, university researchers are looking at management tools for invasive species (e.g., round goby and Kudzu).

- OMAFRA is a member of the North American Soybean aphid research committee, established to address key research and outreach issues on this invasive species in soybeans.

- OMAFRA is a member of the north American Pest information Platform for extension (IPMPIPE) which was established to monitor field crop invasive pests as well as coordinate research, management and communication across North America.