Loggerhead Shrike General Habitat Description

This document is a technical, science-based description of the area of habitat protected for the Loggerhead Shrike.

A general habitat description is a technical document that provides greater clarity on the area of habitat protected for a species based on the general habitat definition found in the Endangered Species Act, 2007. General habitat protection does not include an area where the species formerly occurred or has the potential to be reintroduced unless existing members of the species depend on that area to carry out their life processes. A general habitat description also indicates how the species' habitat has been categorized, as per the policy "Categorizing and Protecting Habitat Under the Endangered Species Act", and is based on the best scientific information available.

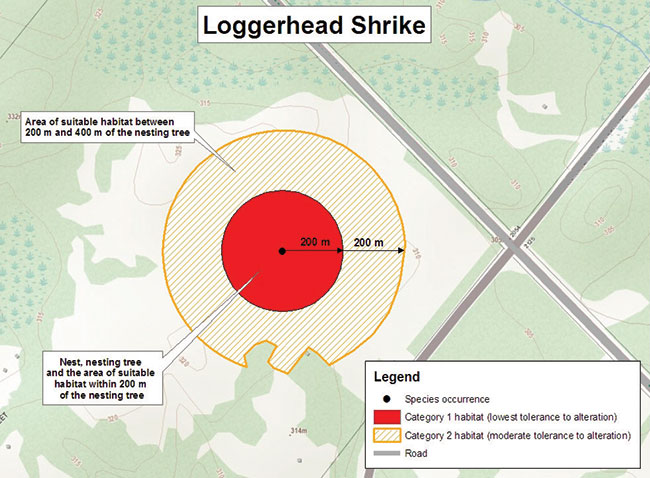

Habitat categorization

- Nest, nesting tree and the area of suitable habitat within 200 m of the nesting tree

- The area of suitable habitat between 200 m and 400 m of the nesting tree

- Not applicable to this species

Category 1

The nest, nesting tree, and the area of suitable habitat within 200 m of the nesting tree is included in Category 1 and is considered to have the lowest level of tolerance to alteration. The area included in Category 1 is highly sensitive because the species depends on it for courting, egg laying, incubation, feeding, resting and rearing of young (Yosef 1996, Collister and Wilson 2007, Environment Canada 2010, Glynn-Morris 2010). Loggerhead Shrikes and available suitable habitat to support them are rare in Ontario.

Suitable habitat for nesting Loggerhead Shrikes generally includes large, open, frequently-grazed grasslands situated on limestone bedrock with shallow soil or other substrates. In Ontario, Loggerhead Shrikes predominately use two types of trees to nest: hawthorns in the Carden Plain and Red Cedar in the Napanee Plain (Chabotet et al. 2001, Glynn-Morris 2010). This species is highly territorial and exhibits site fidelity. Successful nesting sites are most likely to be occupied again the following year, either by the same pair or a different pair (Collister and De Smet 1987, Glynn-Morris 2010, Wildlife Preservation Canada unpublished data). Loggerhead Shrike nests are occasionally reused (Yosef 1996).

In Ontario, the mean defended Loggerhead Shrike breeding territory size during nesting is 12.6 ha (i.e., the area within 200 m of a nesting tree) (Glynn-Morris 2010). The breeding territory usually contains suitable nesting sites, perches (natural or human-made), and foraging areas, including areas for impalement of prey (Environment Canada 2010). Perches are very important features within the species' habitat (Yosef and Grubb 1994, Pruitt 2000, Glynn-Morris 2010). In Ontario, both man-made and natural perches are used by Loggerhead Shrikes, including utility wires, fences/posts, trees, brush piles, and rocks (Chalbot et al. 2001, Glynn-Morris 2010).

They area identified within this category may also be important for additional nesting opportunities. Kridelbaugh (1983) reported that pairs who renested, either after successfully nesting or after a nest failure, had done so within the original breeding territory.

Category 2

The area of suitable habitat between 200 m and 400 m of the nesting tree is included in Category 2 and is considered to have a medium level of tolerance to alteration. These are areas the species depends on for rearing of young, resting, and foraging (Yosef 1996, Glynn-Morris 2010), encompassing nearly all the areas likely to be used by nesting pairs during a breeding season (Luukkonen 1987, Collister 1994, Glynn-Morris 2010). Suitable habitat generally includes large, open, frequently-grazed grasslands situated on limestone bedrock with shallow soil or other substrates.

Category 3

Not applicable to this species.

Activities in Loggerhead Shrike habitat

Activities in general habitat can continue as long as the function of these areas for the species is maintained and individuals of the species are not killed, harmed, or harassed.

Generally compatible:

- Continuation of existing agricultural practices and planned management activities such as annual harvest, mowing, and rotational cattle grazing.

- Activities that help to maintain semi-open or open habitats which provide an abundance of food resources (e.g. thinning of dense shrub thickets).

- Use of existing roadways including access roads.

Generally not compatible

- Large scale development activities that result in significant alteration or clearing of vegetation.

- Indiscriminate application of pesticides within habitat.

Sample application of the general habitat protection for Loggerhead Shrike

References

Chabot, A., R.D. Titman, and D.M. Bird. 2001. Habitat use by Loggerhead Shrikes in Ontario and Quebec. Canadian Journal of Zoology 79:916–925.

Collister, D.M. 1994. Breeding ecology and habitat preservation of the Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus) in southeastern Alberta. M.Sc. thesis, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alta.

Collister, D.M. and De Smet, K. 1997. Breeding and natal dispersal in the Loggerhead Shrike. Journal of Field Ornithology. 68(2):273-282.

Collister, D.M. and S. Wilson. 2007. Territory size and foraging habitat of Loggerhead Shrikes (Lanius ludovicianus) in southeastern Alberta. Journal of Raptor Research 41: 130-132.

Environment Canada. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the Loggerhead Shrike, migrans subspecies (Laniusludovicianus migrans), in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. viii + 35 pp.

Glynn-Morris, M. 2010. Breeding Habitat Selection by the Loggerhead Shrike in Ontario: A Hierarchical Analysis. B.Sc. thesis, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario.

Luukkonen, D. R. 1987. Status and breeding ecology of the loggerhead shrike in Virginia. M.S, Thesis.Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia.

Kridelbaugh, A. 1983.Nesting ecology of the Loggerhead Shrike in central Missouri. The Wilson Bulletin 95(2): 303-308.

Pruitt, L. 2000. Loggerhead Shrike Status Assessment. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, MN, USA.

Wildlife Preservation Canada. 2011. unpublished data.

Yosef, R. and T. Grubb, Jr. 1994. Resource dependence and territory size in Loggerhead Shrikes (Laniusludovicianus). Auk 111: 465-469.

Yosef, R. 1996. Loggerhead Shrike (Laniusludovicianus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/231

Footnotes

- footnote[*] Back to paragraph If you are considering an activity that may not be compatible with general habitat, please contact your local abbr title="Ministry of Natural Resoources">MNR office for more information.