Mottled Duskywing Recovery Strategy

This document is the recovery strategy for a species at risk – the Mottled Duskywing.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Linton, Jessica. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Mottled Duskywing (Erynnis martialis) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 38 pp.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2015

ISBN 978-1-4606-5720-1

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n’est disponible qu’en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l’application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l’aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Authors

Jessica Linton, Natural Resource Solutions Inc., Waterloo, Ontario.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jay Fitzsimmons, Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, for his assistance with the preparation of this document as well as David Stephenson, Natural Resource Solutions Inc. for his critical review and input on the various drafts. Thanks are also extended to Emily Damstra, Natural Science Illustration Inc., Bob Yukich, Naturalist, and Jung Oh and Gerry Schaus, Natural Resource Solutions Inc. for contributing their beautiful illustration, photo, and maps (respectively).

The author also gratefully acknowledges the individuals who provided information on distribution and/or their knowledge of local threats to the species: Colin Jones, Natural Heritage Information Centre; Jenny Wu, COSEWIC Secretariat; Rick Beaver and Janine McLeod, Alderville First Nations; Tanya Berkers, Pinery Provincial Park; Graham Buck, Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry; Paul Catling and Peter Hall, Agriculture and Agri-Foods Canada; Rick Cavasin, Naturalist; Nigel Finney and Brenda Van Ryswyk, Conservation Halton; Ron Gould, Ontario Parks; Ross Layberry, Lepidopterist; Alan MacNaughton, Coordinator of the Ontario Butterfly Atlas Project; Taylor Scarr, Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry; Dale Schweitzer, NatureServe; Ken Stead, Naturalist; Brenda Kulon, Naturalist; Tom Hanrahan, Naturalist; and Bob Yukich, Naturalist. Thank you to Wasyl Bakowsky and Paul Catling for sharing their insights on larval food plant distribution, threats, and abundance which greatly informed this recovery strategy. Lastly, the author would like to thank the following individuals for providing comments on the draft recovery strategy during the jurisdictional review: Colin Jones, Amelia Argue, Aileen Wheeldon, Issac Hébert, Jay Fitzsimmons, Jim Saunders and Dr. Brian Naylor (Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry); Lauren Strybos, Krista Holmes, Rachel deCatanzaro (Canadian Wildlife Service); Nigel Finney and Brenda Van Ryswyk (Conservation Halton); and Peter Hall (Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada).

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Mottled Duskywing was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions, and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

- Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

- Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

The Mottled Duskywing (Erynnis martialis) is a medium-sized dark grey/brown skipper butterfly with a very mottled appearance. It occurs in small, isolated colonies in southern Ontario where suitable habitat occurs. Although never documented as abundant in Ontario, recent observations have only noted single individuals or a small number of individuals. The species was classified as endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2012. Following this assessment, the Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO) assessed and designated Mottled Duskywing as Endangered in 2013, affording it protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), 2007.

Threats to the Mottled Duskywing are worsened by their high degree of habitat specificity combined with limited dispersal ability. Threats in Ontario are related to habitat and include: habitat fragmentation; habitat destruction; succession and canopy closure; deer browsing of larval food plants; pesticide use; and competition between larval food plants and aggressive invasive and/or exotic species. The species also has a complex relationship with fire which is not well understood. Frequent and intense fires may lead to direct mortality of individuals and to supressed larval food plant availability. However, the Mottled Duskywing is also dependent on fire (or other disturbances) to maintain suitable habitat conditions.

The recovery goal for Mottled Duskywing is to ensure that existing threats to metapopulations and habitat are sufficiently mitigated to allow for the long-term persistence and expansion of the species into unoccupied suitable habitats. The protection and recovery objectives to meet the goal are to: 1. inventory, protect and manage extant metapopulations and their habitats; 2. establish reliable population estimates for all metapopulations and assess their viability under current conditions; 3. conduct research on the species’ response to disturbance and climate change to ensure proper management of the habitat; 4. enhance and/or create habitat, where feasible, to increase habitat availability for extant metapopulations; and 5. augment existing populations, assist colonization to re-establish historical populations at suitable sites, and/or assist colonization in previously unoccupied suitable habitats.

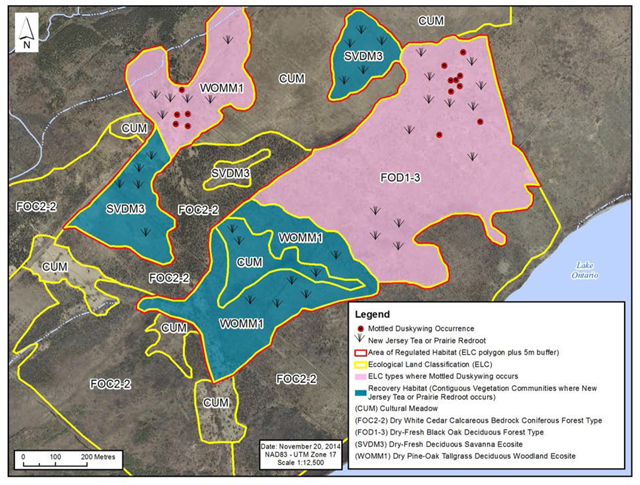

It is recommended that areas where populations of Mottled Duskywing occur be prescribed as habitat within a habitat regulation under the ESA. The boundaries of this area should be identified as a buffered Ecological Land Classification (ELC) vegetation type which contain suitable habitat (i.e. Ceanothus plant colonies) and where Mottled Duskywing occurs. It is recommended that potential recovery habitat for the species also be prescribed within the habitat regulation. These areas are identified as buffered ELC vegetation community types containing suitable habitat, which are contiguous to habitat supporting extant populations.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name: Mottled Duskywing

- Scientific name: Erynnis martialis

- SARO List Classification: Endangered

- SARO List History: Endangered (2014)

- COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2012)

- SARA Schedule 1: No Schedule, No Status

- Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G3

NRANK: N2N3

SRANK: S2

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above and for other technical terms in this document.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

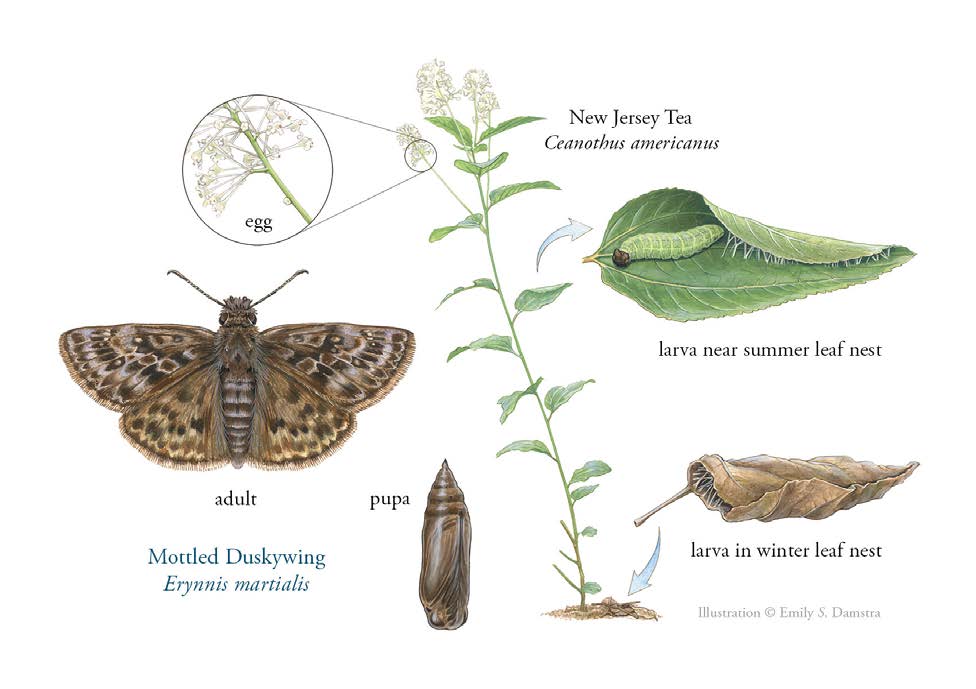

The Mottled Duskywing (Erynnis martialis) is a medium-sized (wingspan: 25-33 mm) dark grey/brown skipper butterfly with a very mottled appearance and in freshly- emerged adults, a purplish hue. Both males and females have yellow-brown spots creating the mottled hindwing pattern (Figure 1). This degree of mottling distinguishes the Mottled Duskywing from other duskywing species (genus Erynnis). Males have a fold in the leading edge of the forewing that contains yellow “scent scales” that harbour pheromones for attracting females (Olson 2002). Females have scent scales on the sides of their abdomens, which are used to attract males (Olson 2002).

Larvae are stout, light green in colour with a dark head (Layberry et al. 1998). They are approximately 25 mm in length at maturity with a narrow constriction (or neck) between the head capsule and the rest of the body (Olson 2002). Larvae can be most easily identified by association with their food plant, which is not shared by any other skippers (family Hesperiidae) in Ontario.

Duskywing skippers are a particularly challenging group to identify, and the Mottled Duskywing has sometimes been misidentified in literature (Schweitzer et al. 2011). Compared to other duskywing species, Mottled Duskywing has very contrasting dark markings. It can be easily misidentified in the field, particularly if an individual’s wings are worn (i.e. tattered or faded), as it commonly is observed drinking from moist soil in the company of other duskywing species (Linton unpub. data 2014). It is most similar in appearance to Horace’s Duskywing (Erynnis horatius), however this species is a rare migrant in Ontario (Layberry et al. 1998). In Ontario, it is most likely to be confused with the female Juvenal’s Duskywing (Erynnis juvenalis), which is larger (wingspan: 30-37 mm) and lacks the same degree of hindwing mottling. On the underside of Juvenal’s Duskywing, the two round pale spots near the apex of the hindwing are diagnostic. Mottled Duskywing may also be mistaken for Wild Indigo Duskywing (Erynnis baptisiae). Wild Indigo Duskywing’s flight period overlaps with Mottled Duskywing and it has recently become much more common throughout southern Ontario. The inner third of Wild Indigo Duskywing’s forewing are much darker becoming lighter toward the tip of the wing. They have a diagnostic light orange or light brown coloured patch in the centre of their forewing.

Species biology

The Mottled Duskywing is not a migratory species, and therefore occupies its habitat throughout the year in its various life stages (Figure 2). It is generally a local species, tending not to stray too far from suitable habitat containing its larval food plants [Prairie Redroot (Ceanothus herbaceus) and New Jersey Tea (C. americanus)]. Adults are on the wing mating and laying eggs from mid-May to late June throughout most of their range, and in extreme southern Ontario, a second brood is on the wing from mid-July to late August (Layberry et al. 1998).

Males are often seen patrolling hilltops for mates, an activity commonly referred to as ‘hilltopping’ (Scott 1986; Opler and Krizek 1984). Adult females lay eggs on the leaves of their larval food plant shortly after fertilization has taken place. Larvae emerge from these eggs only days after they are laid and feed on Ceanothus plants. Larvae form a shelter in which they live by sewing Ceanothus leaves together with silk. Feeding occurs at night, with the larvae making short trips out of the shelter to feed on leaves or to cut sections for later consumption in the shelter (Olson 2002). When mature, the larva spins a cocoon in the leaf litter near the base of the food plant where it either pupates (i.e. forms a chrysalis) and emerges in a few weeks (where a second brood occurs) or overwinters as a larva until spring (Schweitzer et al. 2011). These overwintering nests are usually no more than a centimeter or two beneath the leaf litter allowing exposure to early spring warmth from the sun (Olson 2002).

The Mottled Duskywing is not migratory, however little additional information exists on the movements or dispersal of the species. In one study which focused on generating a mobility index for Canadian butterfly species based on naturalists’ knowledge, the Mottled Duskywing was rated as fairly sedentary and less mobile than other duskywings based on anecdotal information from six respondents (Burke et al. 2011). Extirpated sites do not appear to become recolonized, suggesting that even moderate and incremental dispersal over 10 or more years is unlikely (COSEWIC 2012a).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Historically, Mottled Duskywing existed throughout the eastern and central United States and parts of south-central Canada. Severe population declines have been observed in many U.S. states, and it may no longer occur in some states within its core range (NatureServe 2014). It is generally thought to be extant in most of the states from which it has been historically reported west of the Mississippi River (NatureServe 2014). In Canada, populations of Mottled Duskywing historically extended into southeastern Manitoba, southern Ontario, and southwestern Quebec. This species has not been observed in Quebec since the 1950s, and is thought to be extirpated from the province (COSEWIC 2012a). In southeastern Manitoba, populations are still present but also reported as declining, however habitat is considered more widespread and contiguous than in Ontario (COSEWIC 2012a).

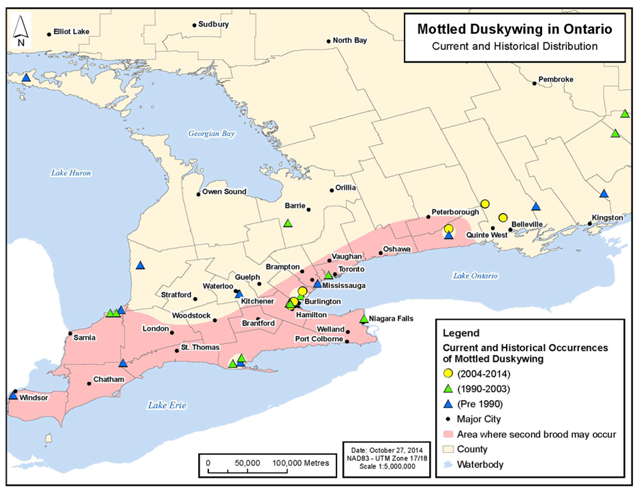

The Mottled Duskywing is extant in southern Ontario, occurring in small, isolated metapopulations where its larval food plant(s) occurs (COSEWIC 2012a). According to the Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) there are 27 element occurrences in Ontario (Figure 3). It has always been observed in small numbers and is rarely considered abundant. The most recent observations (within the past 10 years) have been of single or a small number of individuals. There are thought to be nine metapopulations in Ontario comprised of one to several sites in Alderville, Burlington/Hamilton, Borden, Marmora, Niagara, Ottawa, Oakville, Grand Bend, and Stirling (COSEWIC 2012a).

In 2013 and 2014, individuals were confirmed to persist at sites in Alderville, Burlington/Hamilton, Marmora, and Oakville. It is unknown if Mottled Duskywing is extant in Niagara (last observed in 1991), Borden (last looked for and observed in in 2007), Grand Bend (last confirmed observation 1990, unsubstantiated reports in last 10 years), or Stirling (last observed in 2006) (Figure 3). At several of these sites, search effort has likely not been sufficient to confirm absence. Despite annual search efforts of historically known sites in the Ottawa area, Mottled Duskywing has not been observed since 2008 and it may be extirpated from the area (P. Hall, pers. comm. 2012).

Historically there are records from the St. Williams/Walsingham area, but the species has not been reported in this area since 1994 despite considerable search effort (COSEWIC 2012a). There are also historical records from a number of isolated sites throughout southern Ontario including Chaffey’s Locks, Ipperwash, Kitchener, Manitoulin Island, Northumberland Forest, Skunk’s Misery, Port Credit, Silver Water, Toronto (High Park), Niagara, Bobcaygeon, and Windsor (Figure 3). It is likely that several of these records are misidentifications. Regardless, habitat at the majority of these locations is not considered suitable for Mottled Duskywing (COSEWIC 2012a).

Enlarge Figure 3: Historical and current distribution of Mottled Duskywing in Ontario (PDF)

1.4 Habitat needs

Mottled Duskywing are closely associated with their larval food plants, which in Ontario are Prairie Redroot and New Jersey Tea. Adults seem to prefer partially shaded sites with abundant nectar sources and an ample supply of larval food plants (Olson 2002). Food plant colonies of Prairie Redroot and New Jersey Tea are most often associated with dry, sandy soils within oak woodland, pine woodland, roadsides, hydro corridors, river banks, oak savannahs, shady hillsides, tallgrass prairies and alvars (Soper and Heimburger 1982, Layberry et al. 1998). In Halton Region, New Jersey Tea is found in abundance in clay soils within oak woodland and bluff ecosites (N. Finney pers. comm. 2014). New Jersey Tea is quite common, although rarely abundant, in the deciduous forest region and the Ottawa and St. Lawrence valleys (Soper and Heimburger 1982). It is a low, upright, deciduous shrub with white flowers that grow in oval clusters (Soper and Heimburger 1982). Prairie Redroot is found less commonly in southern Ontario. It is similar in appearance to New Jersey Tea but presents smaller, more narrowly elliptic leaves. Both species are members of the Buckthorn Family (Rhamnaceae) and native to eastern North America (Soper and Heimburger 1982). Species of Ceanothus can tolerate some shading but are not tolerant of closed canopies.

It is generally understood that nectar provides nourishment to butterflies and increases lifespan and reproductive success. There is no scientific research specific to Mottled Duskywing and its associated nectar sources, however it is reasonable to assume that nectar is an essential adult resource and they are often observed nectaring on Ceanothus plants (J. Linton unpub. data 2014). Availability of nectar sources is therefore an important consideration for habitat suitability. Lack of nectar sources is one factor that has been attributed to the decline and subsequent extirpation of Karner Blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) in Ontario (Packer 1994).

Although rich in sugar, nectar lacks some important nutrients Mottled Duskywing need for reproduction. Similar to other species of duskywing, male Mottled Duskywings are often seen sipping water from moist soil, which provides salt and essential minerals (Schweitzer et al. 2011). This behavior is called ‘puddling’ and is mostly seen in male butterflies which incorporate the salts and minerals into their sperm. Following mating, the nutrients males get from the soil are transferred to the female through the sperm. These salts and minerals improve the viability of the female’s eggs.

As indicated previously, Mottled Duskywing is not a migratory species and therefore occupies its habitat throughout the year in its various life stages. This species’ biology ties it closely to its habitat and pre-adult stages of the Mottled Duskywing are almost exclusively associated with its larval food plant. Similarly, adults are closely associated with larval food plants which they use for nectaring, basking, and oviposition (J. Linton unpub. data 2014). Landscape-level topography may also represent an important component of the habitat as males patrol hill tops or high points in the landscape in an effort to find potential mates (Scott 1986; Opler and Krizek 1984).

More research is required, however a key feature of the habitat may be the occurrence of multiple patches of the food plant, as well as scattered individual plants between these, over an area of at least 100 ha (Schweitzer et al. 2011).

1.5 Limiting factors

Limiting factors for the Mottled Duskywing are strongly linked to their high degree of habitat specificity, combined with their assumed limited dispersal ability. They are closely tied to their habitat which provides larval food plants and adult nectar sources. These habitat types are vulnerable to succession in the absence of disturbance, and the geographic isolation and limited availability of suitable habitat to existing metapopulations discourages dispersal and colonization. Each isolated site is therefore vulnerable to habitat damage or the wrong type or extent of disturbance (COSEWIC 2012a), discussed in greater detail in Section 1.6.

These limiting factors may be worsened by climate change. Recent studies suggest that through the processes of altering seasonality, temperature, and rainfall, climate change may uncouple the relationships between host-dependent species by interfering with interactions essential for the survival of one or both species (Foden et al. 2008; Singer and Parmesan 2010; Kingsford and Watson 2011).

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Habitat fragmentation

The threats habitat fragmentation has on biodiversity are often oversimplified in the literature. Generally, it is understood that some species benefit from created edge habitats. In fact, some research suggests that when edges are created in natural ecosystems there is a significant increase in insect richness and insect abundance, particularly Lepidoptera (De Carvalho Guimarães et al. 2014). Despite this trend for other species of Lepidoptera, habitat fragmentation is considered a threat to Mottled Duskywing due to its limiting factors (e.g. limited dispersal ability, host and habitat specificity, etc.).

Habitat fragmentation, brought about by various anthropogenic factors (e.g. urban sprawl, land conversion, intensive vegetation clearing, etc.), reduces the species’ ability to move among suitable sites and is likely the most important long-term threat to the species (COSEWIC 2012a). As with other rare butterflies in Ontario, Mottled Duskywing may have survived in the past through a metapopulation structure with individual populations living in close enough proximity to recolonize (COSEWIC 2012a). This is no longer the case, and Ontario populations are completely isolated from each other.

In the past, the early successional habitats Mottled Duskywing was associated with were continually changing through natural succession and wildfires. In this scenario, Mottled Duskywing would have been dependent on moving from one suitable habitat patch to another as fires or canopy succession made habitat patches unsuitable. The current fragmentation of suitable habitat patches within the landscape prevents this essential colonization.

Because of habitat fragmentation, small isolated metapopulations are also at risk of extinction for genetic reasons. Fragmentation of the landscape results in reduced genetic variation through a combination of fewer immigrants from existing populations and increases the probability of inbreeding among butterflies in isolated patches. The risk of extinction significantly increases with decreasing genetic diversity while inbreeding adversely effects larval survival, adult longevity, and the rate of egg-hatching success (Saccheri et al. 1998).

Habitat destruction

Many Mottled Duskywing metapopulations are within or near populated areas and are therefore vulnerable to disturbances that may reduce habitat quality. Habitat destruction associated with various types of urban development is an ongoing threat and has been directly linked to the loss of some colonies in Ontario including a new camping area in Halton Region (B. Yukich pers. comm. 2007) and a cottage development in Constance Bay (P. Hall pers. comm. 2007). Known sites in Marmora are currently undergoing development which will likely result in the loss of suitable habitat for Mottled Duskywing in the near future (COSEWIC 2012a). The local MNRF office is currently examining the implications of the ESA to habitat destruction at these sites (C. Lewis pers. comm. 2014).

The distribution of larval food plants has decreased over the last 25 years, and the present day extent of these species is not accurately known (COSEWIC 2012a). At many sites where the food plants occur, the quality of the habitat is poor due to competition with other plant species, fire suppression, and development pressures. Distribution of Ceanothus plants was previously documented and mapped by Soper and Heimburger (1982) and indicates that these plants were historically widespread and abundant in southern Ontario. These distribution maps are now considered overestimates of current conditions (P. Catling, pers. comm. 2014). Large colonies of both Ceanothus species are now mostly restricted to habitats documented as being special, rare and declining in Ontario such as savannas, alvars, granite barrens and sand barrens (Catling and Catling 1993; Bakowsky and Riley 1994; Catling and Brownell 1995; Carbyn and Catling 1995; Catling and Brownell 1999a-c; Brownell and Riley 2000; Catling 2008; Catling and Brunton 2010; Catling et al. 2010). At many sites where Ceanothus plants were once abundant, their populations have been diminished to small patches, individual scattered plants, or have disappeared entirely (P. Catling pers. comm. 2014). Factors which have contributed to this decline, and implications of this decline for Mottled Duskywing, are discussed as separate threats in the following sections.

Succession, disturbance, and canopy closure

The Mottled Duskywing relies on a disturbance regime that maintains habitats in an intermediate successional stage suitable for growth of its larval food plant. Consequently, both lack of disturbance and disturbances themselves are detrimental over different geographic and spatial scales (COSEWIC 2012a).

New Jersey Tea is found in greatest abundance at high light intensities and can rapidly colonize disturbed sites where its nitrogen-fixing ability gives it a competitive edge over other species (Delwiche et al. 1965). However, it will decline as successional communities’ mature (Shirley 1932; Hardin 1988). New Jersey Tea and Prairie Redroot are well adapted to fire and after being top-killed by fire, they re-sprout from rootstocks (Swan 1970; Abrams and Dickmann 1982; Throop and Fay 1999). In one study of

Black Oak woodlands of northwestern Indiana, New Jersey Tea was present in two areas with slightly different fire regimes. They found more plants at the site with frequent, low-intensity fires (every five years on average) than the site with less frequent, but more severe fires (Henderson and Long 1984).

The direct effects of fire on the overall persistence of the Mottled Duskywing are unknown, although such events may temporarily eliminate suitable habitat through destruction of the larval food plant or directly eliminate eggs, larvae, and pupae. It is possible that even after the re-establishment of suitable habitat following a large or high- intensity fire, small colonies may be permanently eliminated due to limited dispersal ability. However, some disturbance is required to maintain the early successional habitat in which their food plants thrive, and fire may be a key process in some habitats for achieving this. There is evidence to suggest that fire can have a substantial positive indirect effect on butterflies by increasing both nectar sources and larval food plants (Taylor and Catling 2011).

Taylor and Catling (2011) examined the apparent importance of successional habitat to pollinating insects through a comparison of burned and unburned alvar in an area of the Ottawa Valley (known to have supported colonies of Mottled Duskywing). They found that both bee and butterfly diversity were higher in the post-fire burned alvar woodland compared to the adjacent unburned woodland based on species richness and number of individuals.

Natural succession indirectly affects Mottled Duskywing by shading out larval food plants and reducing areas for basking. Possibly more detrimental is the combination of fire suppression and extensive planting of trees which accelerates these habitat alterations. During the “over-afforestation period” between 1950 and 1970, extensive tree planting led to widespread loss of native open habitat in Ontario (Catling 2013). During this era, sandy open lands were viewed as wasteland which could be improved through planting pine trees (Catling 2013). Many areas which supported colonies of Mottled Duskywing, such as the oak savannahs of Pinery Provincial Park, were planted extensively with pines (Catling 2013). Although the value of open habitats is now recognized, the desire to plant trees still persists (Catling 2013).

Disturbances that reduce tree cover and allow food plants to persist, including fire, are therefore an important factor in habitat maintenance.

Deer browsing

Excessive herbivory by deer has been reported as a factor contributing to this species’ decline in the U.S. (Schweitzer et al. 2011). New Jersey Tea was once a very common shrub in the eastern United States, but has been drastically reduced in abundance by deer and habitat changes, especially from Pennsylvania to New England (Schweitzer et al. 2011). As a result, all three known lepidopteran (i.e. butterfly or moth) species in these areas dependent on New Jersey Tea as a larval food source [Mottled Duskywing, Broad-lined Erastria Moth (Erastria coloraria), and a species of geometrid moth (Apodrepanulatrix liberaria)] are imperiled or extirpated throughout their former range in northeastern U.S.

A recent study which examined changes in Lepidoptera composition over time across host plant feeding guilds (i.e. tree, fern, and understorey herbaceous plants) found Ceanothus plants to be very rare after being considered frequent in previous years along with species which are dependent on them including Mottled Duskywing (Schweitzer et al. 2014). This study highlights the difference in trends between observations of understory Lepidoptera that eat ferns (which deer avoid) and herbaceous plants (which deer prefer) which lends support to the theory that excessive deer browsing may be contributing to the decline of the species in the U.S.

In Ontario, food plant reduction due to White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) browsing has been reported at several sites as a contributing factor to habitat loss. Schweitzer et al. (2011) noted that when Pinery Provincial Park was visited in the late 1980s the extent of deer browsing was greater than anywhere else they had seen (although it should be noted that a deer management plan since greatly reduced the impact of deer browsing in the park). This threat has been reported in Burlington, Oakville, Ottawa, and Grand Bend (COSEWIC 2012a). Deer browsing may also directly eliminate individuals if larvae or eggs are inadvertently consumed.

Pesticides

Insecticide spraying is another factor that is anticipated to have had negative impacts on the Mottled Duskywing populations in the past (Schweitzer et al. 2011). Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is a broad-spectrum insecticide that has been used to control invasive Gypsy Moths (Lymantria dispar dispar) in Ontario. Bt is not species-specific, and is known to affect many types of arthropods and is particularly lethal to lepidopteran larvae (Butler 1998). In Ontario, spraying of Bt to control Gypsy Moths began shortly after this species’ introduction in 1969 (T. Scarr pers. comm. 2014). By the early 1980s, large outbreaks and associated defoliation of oak woodlands was being documented, particularly in the Ottawa and Kaladar areas. In 1986, a private land program resulted in aerial Bt spraying of areas in Ontario on private land as well as several Ontario Provincial Parks and Crown Lands (T. Scarr pers. comm. 2014).

In several areas where Mottled Duskywing historically occurred in small colonies, the disappearance of the species may be correlated with these aerial spraying events to control Gypsy Moths as the timing of these applications likely corresponded with the larval stage of the Mottled Duskywing. Insecticide spraying for Gypsy Moths is thought to have contributed to the decline of several species of butterfly in Ontario known to historically occupy the same areas as the Mottled Duskywing including the Eastern Persius Duskywing (Erynnis p. persius) and Karner Blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) (COSEWIC 2006).

The last Bt spraying by the province occurred in 1991, and the program was cancelled in 1992. Aerial spraying using Bt is no longer directed by the province although private land owners and some municipalities treat forested areas, particularly urban forests and oak woodlands, to reduce the chance of defoliation by Gypsy Moth in outbreak years (T. Scarr pers. comm. 2014). Conservation Halton, in conjunction with neighbouring municipalities, conducted aerial spray programs within the areas of Waterdown Woods, Glenorchy Conservation Area, and Clappison Woods as recently as May 2008 (Conservation Halton 2009). Currently Gypsy Moth populations are considered to be under control due to a number of factors including a fungus native to Japan (Entomophaga maimaiga) which killed off a large portion of the population in the early 1990s, the development and application of a microbial pest-control product (Disparvirus), and natural predation which has become established over the years (T. Scarr pers. comm. 2014).

Herbicide application has been reported at some sites in Burlington and Stirling as contributing to the destruction of larval food plants. Timing and location of herbicide application is likely to affect Mottled Duskywing by killing or suppressing food plants and/or nectar resources.

Invasive species

Competition with aggressive invasive species such as Dog-strangling Vine (Cynanchum rossicum) has been reported from some sites in Burlington as possibly contributing to the decline of larval food plants (B. Van Ryswyk pers. comm. 2014). This threat is also directly related to succession, as recently disturbed communities present an opportunity for invasive species to colonize areas rapidly.

Weather and climate change

Recent studies have characterized the traits that will disadvantage species and populations subject to a rapidly changing climate, many of which are demonstrated by the Mottled Duskywing and include: (1) specialized habitat or microhabitat requirements; (2) narrow environmental tolerances or thresholds; (3) dependence on environmental or specific cues/triggers that are disrupted by climate change; (4) dependence on interactions with particular species; (5) poor ability to disperse to or colonize suitable new habitats; and (6) small population size, area of occupancy or extent of occurrence (Foden et al. 2008; Thomas et al. 2011). Mounting evidence suggests that a changing climate has the potential to directly alter the development or overwintering survival of individuals as well as indirectly affect survival by altering the range, development, and/or nutritional value of larval food plants (Moir et al. 2014). An increase in the number and severity of severe weather events related to climate change may also result in direct mortalities.

| Location | Last observed | Potential or known threats | Owner or manager |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alderville | 2014 | Habitat fragmentation (genetic isolation); habitat destruction (frequency and intensity of prescribed fires). | Alderville First Nations |

| Burlington/ Hamilton | 2014 | Habitat destruction; habitat fragmentation; succession, disturbance, and canopy closure; deer browsing; pesticides; invasive species. | Conservation Halton, Hydro One, Canadian Pacific Railway, private, and an unopened City of Hamilton Road Allowance |

| Borden | 2007 | Habitat fragmentation (genetic isolation); habitat destruction (military operations). | Government of Canada (Canadian Forces Base Borden) |

| Marmora | 2014 | Habitat destruction (ongoing housing development). | Private |

| Niagara | 1991 | Habitat fragmentation (genetic isolation). | Niagara Parks |

| Ottawa | 2008 | Habitat destruction (cottage development); habitat fragmentation; succession, disturbance, and canopy closure; deer browsing. | OMNRF, Ontario Parks |

| Oakville | 2014 | Habitat fragmentation; succession, disturbance, and canopy closure; deer browsing; pesticides; invasive species. | Infrastructure Ontario, Ontario Parks, and private lands to be dedicated to public ownership (Town of Oakville) in the future |

| Grand Bend | 1990 | Succession, disturbance, and canopy closure; deer browsing. | Ontario Parks |

| Stirling | 2006 | Habitat destruction; pesticides (associated with hydro corridor maintenance). | Unknown (possibly Hydro One) |

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Distribution

Due to the efforts of several individuals there is generally good information on the known metapopulations of Mottled Duskywing. Sites where the species is known to occur are visited annually and individuals are often counted and photographed. Several sites where the species historically occurred, particularly in the Ottawa area, are also visited annually by qualified observers to document re-occurrences. However, the total number of metapopulations may not be known and this species would benefit from additional targeted survey work to inform conservation and recovery goals. Similarly, the present day extent of larval food plants is undocumented and mapping their range would be informative for the recovery process. Undocumented reports of Mottled Duskywing also require confirmation, particularly given the possibility of misidentification. Recent census information is lacking for several sites where historical records exist.

Habitat management

There is no published information on how different habitat management activities affect Mottled Duskywing, although it is generally understood that fire, canopy closure, and natural succession can result in habitat alterations which negatively influence the species and/or its habitat. Fire, however, can also be an important process for maintaining the early successional habitat on which the Mottled Duskywing depends. The critical piece of information missing is determining exactly what type and degree of disturbance is most desirable to maintain habitat and allow for the persistence of a viable population of both larval food plants and Mottled Duskywing. Several sites where the Mottled Duskywing occurs, or was historically known to occur, are actively managed by conservation authorities, provincial bodies, or other groups such as the Nature Conservancy of Canada. Further study is required to determine the risk to populations of Mottled Duskywing from the extent of different types of disturbance, particularly prescribed and wild fires, deer browsing, and the resulting habitat alteration. Consideration should also be given to ongoing habitat management activities in specific types of rare or declining habitats in Ontario (e.g. tallgrass prairie, oak woodland, etc.) which may have relevant implications for Mottled Duskywing (e.g. Stringer 2006).

Population viability

The viability of isolated metapopulations is not known. A Mottled Duskywing population viability analysis would greatly inform the recovery process by determining minimum annual population growth rates, identifying the susceptibility of specific metapopulations, and identifying where recovery efforts should focus.

Throughout southern Ontario, New Jersey Tea and Prairie Redroot populations are considered secure, but both species are declining throughout much of the eastern portion of their ranges (NatureServe 2014). Many populations now contain only a few overgrown plants (P. Catling pers. comm. 2014). One report by Schweitzer et al. (2011), which appears to be anecdotal, indicates that a key feature of the required habitat for Mottled Duskywing may be the occurrence of multiple patches of the food plant, as well as scattered individual plants between these, over an area of generally at least 100 ha. However no scientific information currently exists on habitat patch size required to support a viable population of Mottled Duskywing. This information would greatly contribute to conservation and recovery goals.

Dispersal ability

There is currently no published or unpublished data on dispersal of Mottled Duskywing between or within suitable habitats. Gathering information on dispersal between sites, potential barriers to dispersal, and movement of individuals away from their natal sites to find suitable habitats is an important knowledge gap that needs to be addressed and would be beneficial in informing a habitat regulation for the species. Identifying the likelihood and rate of colonization events would also inform where restoration and/or population reestablishment would be most appropriate.

Biology

No literature exists on natural factors likely to influence the survivorship of the Mottled Duskywing including parasitoids or predators. There have been some reports that numbers can fluctuate considerably from year to year, however there is no scientific research to indicate the frequency and/or extent of fluctuations (Olson 2002, COSEWIC 2012a).

As indicated previously, there is no scientific research specific to the types and abundance of nectar (or other food) sources required to sustain Mottled Duskywing adults.

Response to climate change

The species-specific response Mottled Duskywing will have to climate change is not known. As discussed under threats to the species, the Mottled Duskywing displays some characteristic traits which may put it at a great disadvantage subject to a rapidly changing climate. During hibernation mature larvae enter a period of diapause. It is unknown if they are dependent on environmental cues such as warmth, day length, rainfall, etc. to trigger emergence or they are genetically programmed to begin emergence after some period of time. The importance of snow depth and cover to overwintering larvae is also unknown. For some species, such as the Karner Blue butterfly which overwinters in diapausing eggs, snow cover is extremely important to winter survival (USFWS 2003). This basic knowledge would provide important information on the general biology of the species and also inform management and recovery activities.

It is also unknown if the Mottled Duskywing and the larval host plants on which they are dependent will respond differently to climate change. It has been suggested that some lepidopterans could experience micro-habitat cooling if their larval foodplants use temperature cues to leaf-out earlier in warmer springs (WallisDe Vries and Van Swaay 2006). This may result in larvae breaking diapause later because of the cooling/shading effect of overhead leaves. Similarly, if larvae break diapause too early because of changing environmental cues, there may not be adequate larval food plants and/or nectar plants available at the right time to nourish individuals.

It is also possible that climate change may provide a mechanism for habitat creation and/or maintenance in some areas if there is an increase in the frequency and severity of droughts in Ontario. In the Burnt Lands Alvar, where a population of Mottled Duskywing was known to occur up until 2008, drought has been observed to prevent the encroachment of woody plants and maintain open habitats (Catling 2014). Therefore drought may prevent forest succession by directly eliminating woody vegetation and indirectly by promoting fire through creating drier conditions (Catling 2014).

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

The Mottled Duskywing is listed as endangered in Ontario and therefore their ‘general habitat’ is automatically protected by the ESA. General habitat is an area on which a species depends, directly or indirectly, to carry out its life processes (Government of Ontario 2014). In accordance with the ESA, the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry is required to propose a habitat regulation for Mottled Duskywing by June 27th, 2016. This habitat regulation will then replace the general habitat protection.

The Alderville First Nation actively protects and manages the Black Oak savanna habitat in which Mottled Duskywing occurs (R. Beaver pers. comm. 2014). This includes wildfire suppression/management and habitat monitoring to document canopy cover and the health of New Jersey Tea plants. The site is on a five year prescribed burn plan which targets suppression of competing plants such as Grey Dogwood (Cornus racemosa), sumac (Rhus spp.), and poplars (Populus spp.) which have the potential to shade out New Jersey Tea. The Alderville First Nation has identified that no more than one quarter of the 45 hectare habitat where Mottled Duskywing occurs shall be burned at one time as a management target (R. Beaver pers. comm. 2014). At this time there are no specific monitoring programs for Mottled Duskywing to determine if this approach is appropriate for maintaining a viable population of the species. The Alderville First Nation is also currently undertaking a species at risk study for the entire Alderville First Nation area to identify specific management objectives for individual species. It is anticipated that the final species at risk report (due in late 2015/early 2016) will incorporate Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge and recommendations outlined in the final Ontario Recovery strategy for the species (R. Beaver pers. comm. 2014).

In addition to the Alderville First Nations site, several other properties in the Rice Lake Plains area which are owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada are part of ongoing tallgrass prairie and Black Oak Savanna restoration projects (V. Deziel pers. comm. 2014). Activities at these sites include prescribed burns, invasive species removal, tree removal to prevent forest succession, and tallgrass plantings (V. Deziel pers. comm. 2014). New Jersey Tea is present throughout these sites and efforts are being made to educate volunteers about identification of Mottled Duskywing.

The Karner Blue Recovery Team has conducted habitat restoration and management in Pinery Provincial Park, Karner Blue Sanctuary, St. Williams, and the Alderville First Nation for Karner Blue and Frosted Elfin. Many of these recovery efforts are mutually beneficial to Mottled Duskywing and include actions such as planting New Jersey Tea and other wildflowers, as well as suppression of canopy closure through prescribed burning and control of woody vegetation. The Pinery also started a Deer Management Program in 1998 which has led to the recovery of an increased diversity of wildflower species which provide butterfly nectar sources (T. Berkers pers. comm. 2014).

There are also other parks and protected areas within southern Ontario that could provide habitat for Mottled Duskywing and in which active oak savanna habitat protection and restoration activities occur. These include Long Point and Turkey Point Provincial Parks where prescribed burning and/or dune management programs directly benefit the availability of New Jersey Tea as well as the overall size and stability of related habitat areas (R. Gould pers. comm. 2014). As such activities continue the relative availability of food plants should increase at these locations. These sites, however, will continue to occur in a highly fragmented landscape with a lack of suitable linkages so natural dispersal and colonization to and from these areas is unlikely. A significant amount of tallgrass prairie planting has occurred within Bronte Creek Provincial Park in recent years but oak savanna communities remain limited in this area where habitat loss from urban development is an ongoing threat (R. Gould pers. comm. 2014).

Conservation Halton has completed a draft management plan for the Halton area which contains specific recommendations with regard to habitat management, improvements and Mottled Duskywing population monitoring (B. Van Ryswyk pers. comm. 2014). In this region, the largest threats to Mottled Duskywing and their habitat are thought to be habitat fragmentation and destruction as well as natural succession (N. Finney pers. comm. 2014). Pesticide use may also be a threat however there is no direct evidence to support this. The management plan will address these specific threats as well as make specific recommendations for Mottled Duskywing habitat restoration and creation.

Conservation Halton also started a large grassland and oak woodland restoration project within Glenorchy Conservation Area in 2012, a project which is ongoing (N. Finney pers. comm. 2014). This includes conversion of agricultural lands and habitat restoration to establish a wide range of habitats including successional forest and oak woodland. Restoration efforts which may assist in recovery of Mottled Duskywing include planting New Jersey Tea as well as seeding and planting of nectar sources for butterflies. The Oakville metapopulation of Mottled Duskywing occurs at sites located in close proximity (approximately 0.75 to 1.2 km) to the restoration area. Conservation Halton has developed a long-term annual butterfly monitoring program to document changes in species’ abundance and diversity which occur as the restoration area becomes established. Potential colonization of the area by Mottled Duskywing has been identified as a key component of the monitoring program (N. Finney pers. comm. 2014). The author has provided comments and recommendations to Conservation Halton on how the monitoring program can be enhanced and the restoration of Glenorchy can be optimized to provide a habitat for Mottled Duskywing.

The active management of the St. Williams Conservation Reserve (including the former Manestar Tract property) has resulted in a large core area of suitable habitat in the area (R. Gould pers. comm. 2014). These lands also abut Turkey Point Provincial Park where suitable habitat occurs for Mottled Duskywing. Management and operating plans have been developed for the St. Williams Conservation Reserve which include a focus on restoring significant areas of oak savanna and sand barren habitat that currently support populations of New Jersey Tea and a variety of other nectaring plants (R. Gould pers. comm. 2014). Several prescribed burn projects have already taken place in the reserve since 2005, as well as some targeted mechanical thinning and conifer harvest which should also increase habitat availability.

The recent purchases of significant tracts of land by the Nature Conservancy of Canada in the Long Point/Norfolk Sand Plains area have also provided some very important habitat restoration opportunities in the heart of the species’ range. Many of these have already been converted from agricultural use to oak savanna and prairie restoration sites, providing additional habitat within close range of other protected areas in the Long Point-Turkey Point vicinity (R. Gould pers. comm. 2014).

As noted under threats to the species, competition with aggressive Dog-strangling Vine has been identified as contributing to the decline of larval food plants in some jurisdictions. This species was recently added to Ontario’s Weed Control Act. Adding this weed to the noxious weed list provides a tool for resource managers to control these non-native plants to minimize interference with the natural environment.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal for Mottled Duskywing is to ensure that existing threats to metapopulations and habitat are sufficiently mitigated to allow for the long-term persistence and expansion of the species into unoccupied suitable habitats.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

The priority of the short-term recovery objectives, and the overall recovery goal, is the protection of viable, self-sustaining extant metapopulations of Mottled Duskywing by ensuring that no further loss or degradation of known habitat occurs. Long-term objectives focus on recovery of non-viable existing populations, assisted colonization to re-establish historical populations at suitable sites, and/or assisted colonization in previously unoccupied, suitable habitats.

Table 2. Protection and recovery objectives

Table 2 converted to a list

- Inventory, protect and manage extant metapopulations and their habitats.

- Establish reliable population estimates for all metapopulations and assess viability under current conditions.

- Conduct research on the species’ response to disturbance and climate change to ensure proper management of the habitat.

- Enhance and/or create habitat, where feasible, to increase habitat availability for extant metapopulations.

- Augment existing populations, assist colonization to re-establish historical populations at suitable sites, and/or assist colonization in previously unoccupied, suitable habitats.

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 3. Approaches to recovery of the Mottled Duskywing in Ontario

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Inventory and Protection |

1.1 Map the extent of each extant metapopulation and its associated habitat.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Protection, Communication and Stewardship |

1.2 Work collaboratively with stakeholders including landowners, conservation authorities, MNRF, and First Nations to protect and manage habitat.

|

Threats:

|

| Necessary | Short-term | Monitoring and Inventory | 1.3 Develop and implement a standardized survey protocol for Mottled Duskywing. – Include an approach for confirming presence/absence as well as documenting annual population fluctuations. |

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Research |

2.1 Conduct population viability analyses of extant metapopulations.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research |

2.2 Conduct research on dispersal within and between habitat patches to determine potential for gene flow and colonization of new sites.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Research and Management | 3.1 Conduct research on how different management activities including prescribed fire, wildfire suppression, and deer management, affect the species and its habitat. |

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Short-term | Research and Management | 3.2 Conduct research on triggers/cues Mottled Duskywing larvae use to break diapause and implications of larval food plant responses to climate change which have implications for the species. |

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Critical | Long-term | Research and Management | 3.3 Apply research findings (as described in 3.1 and 3.2) to current and future management practices. |

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Stewardship | 3.4 Integrate management and restoration planning with property management plans and conservation initiatives where they exist. |

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Research and Management |

4.1 Map suitable habitat for species.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Restoration | 4.2 Consider planting wildflower nectar sources and appropriate Ceanothus species at select locations where Mottled Duskywing occurs. |

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management Restoration | 4.3 Control deer browsing at sites with extant metapopulations of Mottled Duskywing if necessary and monitor effectiveness of the program. |

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management Restoration |

4.4 Consider selective removal of shade trees and shrubs to improve habitat for food plants.

|

Threats:

|

| Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management |

5.1 Consider augmenting existing populations where feasible and appropriate based on a population viability analysis.

|

Threats:

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management |

5.2 Consider re-establishing the species at historical sites where suitable habitat remains and/or assisting colonization at previously unoccupied sites within suitable habitat.

|

Threats:

Knowledge gaps:

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

The recovery objectives and specific recovery approaches outlined in Table 3 focus on maintaining extant populations through protection, management, and research. Augmenting existing populations and considering assisted colonization at historic and new sites are also identified, but are considered a lower priority as there are research activities that need to occur first to inform this approach to recovery.

The most important first steps to recovering Mottled Duskywing are identifying and protecting all extant populations, conducting population viability analyses of these populations, and determining their requirements for dispersal and persistence (e.g. minimum habitat patch, responses to disturbance, etc.). After these actions have been completed, the focus on recovery shifts to restoring/enhancing habitat and augmenting or establishing populations.

Section 1.8 identifies recovery actions completed or currently underway. The locations and activities identified in this section provide important insights into where specific approaches to recovery may be appropriate, feasible (given current human and financial resource commitments), and easily incorporated into ongoing initiatives. This includes:

- habitat management and ongoing monitoring at the Alderville First Nation Black Oak Savanna and Conservation Halton lands which presents an opportunity to study how Mottled Duskywing respond to specific disturbances including fire, deer browsing, and food plant competition;

- monitoring of extant populations at the Alderville First Nation Black Oak Savanna and in Halton, where opportunities may exist to conduct initial population viability analyses;

- habitat restoration and monitoring occurring in Halton Region near extant colonies which may allow for research on Mottled Duskywing dispersal;

- habitat restoration and management in Burnt Lands Provincial Park, the Rice Lake Plains, and the Grand Bend areas where opportunities exist for population augmentation and/or re-introduction of Mottled Duskywing (dependent on the populations current status); and

- oak savanna and prairie restoration in the Long Point/Turkey Point/Norfolk Sand Plains area. This complex of protected sites and expanding habitat availability in one general location may provide the best opportunity for a large, restored core area with metapopulation functions compared to other more fragmented sites in Ontario (R. Gould pers. comm. 2014).

There are many other locations where Mottled Duskywing was known to occur previously, including areas on publically-owned lands, which could provide opportunities for habitat improvements and/or population re-establishment, including Bronte Creek Provincial Park, Niagara Glen Nature Reserve, Northumberland Forest, and privately owned properties in Halton Region. Similarly, there are a number of properties owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada in the Rice Lake Plains area which provide suitable habitat for Mottled Duskywing, are actively managed, and are in close proximity to known populations.

The well-known population in Marmora is currently threatened by ongoing residential development. This site provides an opportunity to examine methods to avoid direct impacts to the species through transplanting food plants (adhering to strategic timing windows), educating future residents about the species and its habitat requirements, encouraging the planting of food plants and nectar sources, and habitat restoration in appropriate places such as planned open spaces.

Consideration should also be given to the implications a changing climate may have on Mottled Duskywing and its habitat. The geographic area in which suitable climate and habitat exists for Mottled Duskywing may be shifting northward. In the future, it is anticipated that many butterfly species will have to shift their ranges northward to track their climatic niche (Buckley et al. 2013) and an inability to spread into new areas may result in large reductions in many species’ ranges in the future (Willis et al. 2009). This is particularly the case for habitat specialists and species with poor dispersal ability (Warren et al. 2001).

The range of Ceanothus species in Ontario may extend further north than known occurrence for the Mottled Duskywing (Soper and Heimburger 1982) and suitable habitats may be present in previously unoccupied geographic areas for this species. Assisted colonization of butterflies to suitable habitats farther north than their current and/or historically known ranges has been successful in Europe (Willis et al. 2009). There are a number of biological (Regan et al. 2012; Chauvenet et al. 2013), socio- economic and regulatory considerations for assisted colonization (Klenk & Larson 2013; Schwartz et al. 2012; Schwartz and Martin 2013). One of the main impediments to the success of this type of translocation is inadequate planning (Chauvenet et al. 2013). Therefore, the overall approach to this type of recovery must consider not only the benefits to Mottled Duskywing but the ecological risk to the recipient ecosystem (Schwartz and Martin 2013).

2.4 Performance measures

Table 4. Performance measures

| Objective | Performance measure |

|---|---|

| Inventory, protect and manage extant metapopulations and their habitats. |

|

| Establish reliable population estimates for all metapopulations and assess viability under current conditions. |

|

| Conduct research on the species’ response to disturbance and climate change to ensure proper management of the habitat. |

|

| Enhance and/or create habitat, where feasible, to increase habitat availability for extant metapopulations. |

|

| Augmenting existing populations, assist colonization to re-establish historical populations at suitable sites, and/or assist colonization in previously unoccupied, suitable habitats. |

|

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Mottled Duskywing is dependent on its larval food plants for breeding and overwintering, thus it will only be found where its larval food plants occur. In Ontario, Mottled Duskywing will only use New Jersey Tea or Prairie Redroot as larval food plants therefore the area of the habitat that should be included in the habitat regulation is dependent on the extent of the plant. It may consist of large colonies of New Jersey Tea or Prairie Redroot or only a few individual plants. This habitat encompasses the area where adult males will seek out females with whom to mate, females will lay their eggs, larvae will live and feed until pupation, and the species will overwinter.

The minimum area that should be prescribed in a habitat regulation for Mottled Duskywing should include the area of suitable habitat (i.e. Ceanothus plant colonies) occupied by all extant populations. For consistency, it is recommended that vegetation types should be described based on the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) methods for southern Ontario (Lee et al. 1998). To ensure protection of Ceanothus plant colonies that occur along edge habitats, an additional 5 m buffer around the ELC polygon should also be protected. This buffer provides adequate root protection for Ceanothus shrubs and allows for additional plant dispersal and/or crown radius growth beyond the actual ELC polygon.

At this time there is no research to support the identification and protection of habitats which may become occupied by the species in the future. However, based on the best information available, it is reasonable to assume that habitat with suitable vegetation types, and that is contiguous to the habitat identified as supporting extant populations, could provide future dispersal habitat for the species. It is therefore recommended that all contiguous suitable habitats (i.e. vegetation types containing Ceanothus plant colonies) to a community in which an extant population occurs be considered for inclusion in the habitat regulation along with a 5 m buffer. Narrow gaps (e.g. 20 m) between vegetation types, for example a road right-of-way, should not be considered a barrier. An example of how habitat is recommended to be mapped under the habitat regulation is provided in Figure 4.

Research on Mottled Duskywing dispersal, as recommended in this recovery strategy, may inform a larger (or smaller) extent of recovery habitat protection that is required (e.g. if research indicates that Mottled Duskywing can disperse up to, but not more than, 500 m from a natal site, it may be more appropriate to take a different approach to delineating the regulated habitat). Therefore, the habitat regulation should allow for incorporation of this information in the future.

The persistence of suitable habitat for Mottled Duskywing at several sites is dependent on periodic disturbance to prohibit canopy closure. Therefore it is recommended that the habitat regulation be flexible to accommodate management of sites, including deliberate disturbance, to ensure persistence of larval food plants. As new information on appropriate approaches to habitat management for the species become available these should also be considered. There are areas of apparently suitable but unoccupied habitat within southern Ontario. Therefore, the habitat regulation should be flexible to accommodate newly discovered sites and those where recovery efforts are planned or ongoing.

Glossary

- Alvar

- Alvars are open, usually treeless or sparsely treed ecosystems, that occur on level limestone or dolostone bedrock with very shallow soils. Alvar vegetation is usually dominated by grasses and sedges or low, creeping shrubs. There are different types of alvars just as there are different types of forests.

- Assisted colonization

- The act of deliberately helping plant and animal species colonize new habitats.

- Colony

- A group of organisms of the same species living in close proximity to each other.

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC)

- The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO)

- The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank

-

A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure - Diapause

- A physiological state of dormancy in response to adverse environmental conditions such as winter.

- Element Occurrence

- An area of land and/or water on/in which an element is or was present. An Element Occurrence may be comprised of one or more observation(s) and is a location important to the conservation of the species or community.

- Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)

- The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Extant

- Still in existence.

- Extirpated

- A wildlife species that no longer exists in the wild in a particular geographic area, but exists elsewhere.

- Hilltopping

- A behavior in which males patrol hill tops or high points in the landscape in an effort to find potential mates.

- Lepidoptera

- The taxonomic order of insects that includes butterflies and moths.

- Metamorphosis:

- A biological process by which a larva (caterpillar) physically changes its body structure through cell growth and differentiation into an adult butterfly.

- Metapopulation

- A group of spatially separated populations of the same species, along with areas of suitable habitat, which interact at some level.

- Nectaring

- The process of drinking nectar from a flower.

- Oviposition:

- The process of depositing or laying eggs.

- Pheremone

- A chemical excreted by an adult butterfly to trigger a response, for example to attract mates.

- Puddling

- The behaviour in which butterflies gather on moist soils or around mudpuddles to drink fluids.

- Scent scale

- A scale which emits an odor attractive to the opposite sex of the species. Also called androconia when on the forewing of males.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA)

- The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List

- The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

- Succession

- The observed process of changes in species composition in an ecological community over time.

References

Abrams, M.D. and D.I. Dickmann. 1982. Early revegetation of clear-cut and burned jack pine sites in northern lower Michigan. Canadian Journal of Botany 60:946-954.

Bakowsky, W. and J. Riley. 1994. A survey of the prairies and savannas of Southern Ontario (pages 7-16). In P. Wickett, D. Lewis, A. Woodliffe and P. Pratt (eds.). Proceedings of the Thirteenth North American Prairie Conference: Spirit of the Land, a Prairie Legacy. Windsor, ON.

Beaver, Rick, pers. comm. 2014. Email and telephone correspondence to J. Linton. July 2014. Land Manager, Alderville First Nation. Alderville, Ontario.

Berkers, Tanya, pers. comm. 2014. Telephone correspondence to J. Linton. June 2014. Pinery Provincial Park. Grandbend, Ontario.

Brownell, V.R. and J.L. Riley. 2000. The alvars of Ontario: significant alvar natural areas in the Ontario Great Lakes Region. Federation of Ontario Naturalists. 269 pp.

Buckley, L.B., S.A. Waaser, H. J. MacLean, and R. Fox. 2013. Does including physiology improve species distribution model predictions of responses to recent climate change? Ecology 92:2214–2221.

Burke, R.J., J.M. Fitzsimmons, and J.T. Kerr. 2011. A mobility index for Canadian butterfly species based on naturalists’ knowledge. Biodiversity and Conservation 20:2273-2295.

Butler, L. 1998. Non target impact of Gypsy Moth insecticides. University of West Virginia. Website: http://www.wvu.edu/~agexten//ipm/insects/nigmi.htm (accessed July 2014). [link inactive].

Carbyn, S.E. and P.M. Catling. 1995. Vascular flora of sand barrens in the middle Ottawa Valley. Canadian Field-Naturalist 109(2):242-250.

Catling, P.M. 2014. Impact of the 2012 Drought on Woody Vegetation Invading Alvar Grasslands in the Burnt Lands Alvar, Eastern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 128(3):243-249.

Catling, Paul M., pers. comm. 2014. Email and telephone correspondence to J. Linton. June and July 2014. Research Scientist, Agriculture and Agri-Foods Canada. Ottawa, Ontario.

Catling, P.M. 2013. The cult of the Red Pine- a useful reference for the over- afforestation period of Ontario. Canadian Field Naturalist 127(2):198-199.

Catling, P.M. 2008. The extent and floristic composition of the Rice Lake Plains based on remnants. Canadian Field-Naturalist 122(1):1-20.

Catling, P.M. and V.R. Brownell. 1995. A review of the alvars of the Great Lakes region: distribution, floristic composition, phytogeography and protection. Canadian Field- Naturalist 109(2):143-171.

Catling, P.M. and V.R. Brownell. 1999a. The granite rock barrens of southern Ontario. Pp. 392-405 in Savanna, barren and rock outcrop communities of North America. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish and J.M. Baskin (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. CB2 2RU. 470 pp.

Catling, P.M. and V.R. Brownell. 1999b. The alvars of the Great Lakes region. Pp. 375- 391 in Savanna, barren and rock outcrop communities of North America. R.C. Anderson, J.S. Fralish and J.M. Baskin (eds.). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. CB2 2RU. 470 pp.

Catling, P.M. and V.R. Brownell. 1999c. An objective classification of Ontario Plateau alvars in the northern portion of the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone and a consideration of protection frameworks. Canadian Field-Naturalist 113(4):569-575.

Catling, P.M. and D.F. Brunton. 2010. Some notes on the biodiversity of the Constance Bay Sandhills. Trail and Landscape 44(3):123-130.

Catling, P.M. and V.R. Catling. 1993. Floristic composition, phytogeography and relationships of prairies, savannas and sand barrens along the Trent River, eastern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 107:24-45.

Catling, P.M., K.W. Spicer and D.F. Brunton. 2010. The history of the Constance Bay Sandhills – decline of a biodiversity gem in the Ottawa valley. Trail and Landscape 44(3):106-122.

Chauvenet, A.L.M., J.G. Ewen, D.P. Armstrong, T.M. Blackburn, and N. Pettorelli. 2013. Maximizing the success of assisted colonizations. Animal Conservation 16(2):161- 169.

Conservation Halton. 2009. Urban creeks and supplemental monitoring: long term environmental monitoring program. October 2009. 86 pp.

COSEWIC. 2006. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing in Canada. Endangered, 2006. Government of Canada. 2007. Species at Risk Public Registry. Website: http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_eastern_persius_duskywing_e.pdf (accessed September 2014).

COSEWIC. 2012a. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Mottled Duskywing Erynnis martialis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiv + 35 pp. (https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/species-risk-public-registry.html.

COSEWIC. 2012b. COSEWIC Excel database of occurrences for Mottled Duskywing. Provided by J. Wu Co-coordinator, Atlas Project, Toronto Entomologists’ Association to J. Linton.

De Carvalho Guimarães, C.D., J.P. Rodrigues Viana, and T. Cornelissen. 2014. A meta-analysis of the effects of fragmentation on herbivorous insects. Environmental Entomology 43(3):537-545.

Delwiche, C.C., P.J., Zinke and C.M. Johnson. 1965. Nitrogen fixation by Ceanothus. Plant Pathology 40:1045-1047.

Deziel, Val, pers. comm. 2014. Email correspondence to J. Linton. July 18, 2014. Assistant Conservation Biologist, Nature Conservancy of Canada, Rice Lake Plains, Ontario.

Finney, Nigel, pers. comm. 2014. Email and telephone correspondence to J. Linton. June 2014. Terrestrial Ecologist, Conservation Halton. Burlington, Ontario.

Foden, W., G.M. Mace, J.C. Vié, A. Angulo, S.H. Butchart, and L. DeVantier. 2008. Species susceptibility to climate change impacts. In: V. Jean-Christophe, C. Hilton-Taylor, and S.N. Stuart (eds.). Wildlife in a changing world–an analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of threatened species. Gland, Switzerland.

Gould, Ron, pers. comm. 2014. Email correspondence to J. Linton. July 3, 2014. Ontario Parks, Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Aylmer, Ontario.

Government of Ontario. 2014. How species at risk are protected. How Ontario Protects Species at Risk (accessed October 23, 2014).