Pale-bellied frost lichen recovery strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the pale-bellied frost lichen, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Photo: Chris Lewis

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

February 2011

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA, 2007 outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA, 2007. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Lewis, C.L. 2011. Recovery Strategy for the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (Physconia subpallida) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 24 pp.

Cover illustration:

Chris Lewis, Lichenologist

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2011

ISBN 978-1-4435-4960-8 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Pamela Wesley au ministère des Richesses naturelles au

Authors

Chris Lewis – Lichenologist, Lakefield, Ontario

Acknowledgments

The expertise and insight of a number of lichen experts was appreciated. In particular, Robert E. Lee is thanked for generously sharing his expertise on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen and accompanying Barbara Gaertner and me to the Billa Lake site. Dr. Irwin Brodo, an emeritus scientist at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, Ontario and Natalie Cleavitt, author of the COSEWIC status report, are also thanked for providing their thoughts and insights. As well, thanks to Will Pridham for the creation of the distribution maps.

Declaration

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has led the development of this recovery strategy for the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (Physconia subpallida) is an endangered macrolichen. This foliose lichen is most often found on Eastern Hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) in mature to old-growth, humid forests. Historic locations were recorded by John Macoun 100 years ago near Belleville, Brighton and Ottawa. Currently there are only three known remaining populations in Ontario of which none are considered as one of Macoun’s historic records.

The recovery goal is to maintain the size and distribution of all extant and newly discovered populations of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in Ontario, with hopes of population increases through habitat protection, and to fill in some of the identified knowledge gaps. The objectives of the recovery strategy are to:

- Protect individuals and habitat at all known occurrences of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen.

- Provide communication and outreach materials on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen and its recovery to relevant landowners, land managers, municipalities and planners to restrict habitat destruction at any of the known sites.

- Inventory and map all known Pale-bellied Frost Lichen locations, populations and habitats by 2016 to provide quantitative baseline data for future monitoring, and initiate a monitoring program.

- Conduct surveys for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in suitable habitat.

- Conduct research to address knowledge gaps for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen.

The recovery approaches recommended in this recovery strategy should be carried out in part or in whole by 2016.

These objectives can be achieved through research, inventory and monitoring, protection and management, as well as education and stewardship.

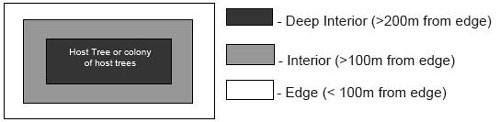

Edge effects, caused by forest disturbance have been shown to impact groups of common forest lichens up to a distance of 50 m. Relatively rare interior forest lichen species, reliant on old-growth forest characteristics and sensitive to microhabitat disturbance, like the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen, would potentially require greater distances to maintain their required habitats. Deep forest-interior species are found in areas that are greater than 200 m from the forest edge. It is recommended that the minimum area that should be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation include a 200 m radius surrounding each host tree, or colony of host trees.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Pale-bellied Frost Lichen

Scientific name: Physconia subpallida

SARO list classification: Endangered

SARO list history: Endangered (2010)

COSEWIC assessment history: Endangered (2009)

SARA Schedule 1: N/A

Conservation status rankings: GRANK: GNR NRANK: N1 SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is a relatively conspicuous circular/rosette-forming foliose macrolichen. A dense covering of white pruina, which looks like frosting, on the upper surface provides a stark contrast to this species when compared to the relatively dark substrate on which it grows (e.g., hardwood bark). Rosettes can be as little as one to two cm in diameter, although thalli are more typically found growing in the three to four cm diameter range but have also been be found as large as 8 to 11 cm (Esslinger 1994).

Two growth forms of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen have been identified. The two forms are separated by the variation in the central portions of the rosette. One form has a densely lobulate center with erect cylindrical lobules (Figures 1a and 1b), and the other is an apothecate form with flattened lobules protruding from the margins or edge of the apothecia (Figure 2). Although these two forms differ in central thalline characteristics they both have flat elongated lobes 1.0 to 2.5 (up to a maximum of 3.0) mm wide extending from the center to the outer edges (Esslinger 1994). Combination apothecate- to lobate- form specimens can also be found.

Figure 1a. Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (centrally lobulate form - arrow)

Figure 1b. Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (centrally lobulate form - arrow)

Figure 2. Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (apothecate form - arrows)

There are several distinctive characters of this species to separate it from other eastern Physconia species: (1) absence of isidia and soredia, (2) presence of lobulate apothecia and/or lobules with pycnidia and (3) the pale undersurface with squarrose rhizines in distinct clusters (COSEWIC in press). A similar species, "Shaggy-fringed Lichen" or Anaptychia palmulata, can also have an entirely pale lower surface, at least in herbarium material, but has simple to bunched rhizines rather than to squarrose rhizines. Anaptychia palmulata also lacks the dense pruinose covering on the apothecia and lobes (Brodo et al. 2001, COSEWIC in press). Other species of Physconia can also be fertile (bearing apothecia) but are not commonly produced.

Species biology

Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is typically found growing on substrates with a high pH, an ability to retain water, and in areas with high humidity levels. In Ontario these substrates have historically included the trunk bark of American Elm (Ulmus americana), and ash (Fraxinus spp.) and old rails. Extant Ontario populations seem to be limited to the trunks of Eastern Hop-hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana) (Figures 3a and 3b and 4a. 4b, and 4c), also known as Hop-hornbeam or Eastern Hop-hornbeam (COSEWIC in press).

Figure 3a. Typical growth location

Figure 3b. Typical growth location - detail

Figure 3b is a close-up of the black box indicated in Figure 3a.

Figure 4a. Typical growth location

Figure 4b. Typical growth location - upper detail

Figure 4c. Typical growth location - lower detail

Figures 4b and 4c are close-ups of the black boxes indicated in Figure 4a.

Lichens are formed by the association of a fungal component and a photosynthesising component, usually alga. The photobiont is responsible for producing food for the organism through photosynthesis (Brodo et al. 2001). Lichens reproduce using a number of strategies including sexual reproduction, which is relatively complicated and risky since the mycobiont (fungus) spore must find the photosynthetic component somewhere in the wide expanses of nature, and fragmentation, where bits of the lichen (e.g., lobules, isidia) containing both symbiotic partners break off the parent thallus. The complexities and challenges of these various strategies are discussed in Nash (1996).

Pale-bellied Frost Lichen reproduces both sexually and asexually, assuming that the lobules can function as a means of asexual reproduction. However, the species lacks soredia or isidia, and it is possible that the larger lobules are not as easily dispersed as these smaller propagules (COSEWIC in press).

No data exist that clearly show how this species disperses but lichen in general have a variety of dispersal vectors including: wind and fauna (e.g., frogs, birds, insects, mammals).

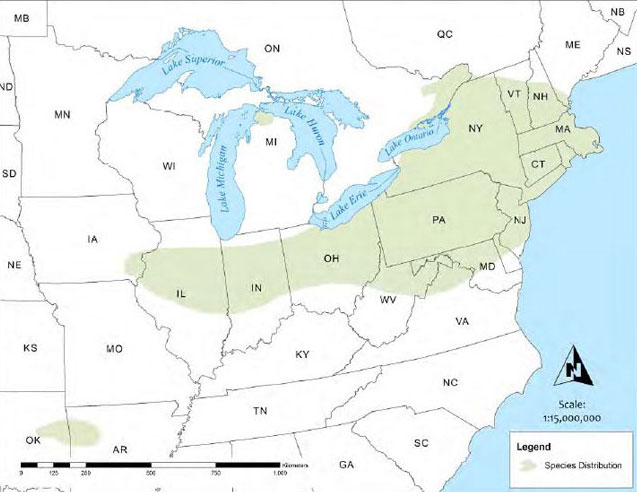

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is currently understood to be a North American endemic species occurring only in the United States and Canada. It is known, at least historically, from Massachusetts and New Hampshire west to southern Ontario, Michigan and eastern Iowa south to central Illinois, Ohio and Virginia. A disjunct population occurs in the Ozarks region of eastern Oklahoma and northwestern Arkansas (Figure 5). Throughout its range it is quite local with large distances between populations. The vast majority of collections are pre-1973 with only four samples collected since 1973 (COSEWIC in press).

Figure 5. Distribution of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in North America

(based on COSEWIC in press)

Enlarge Figure 5. Distribution of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in North America

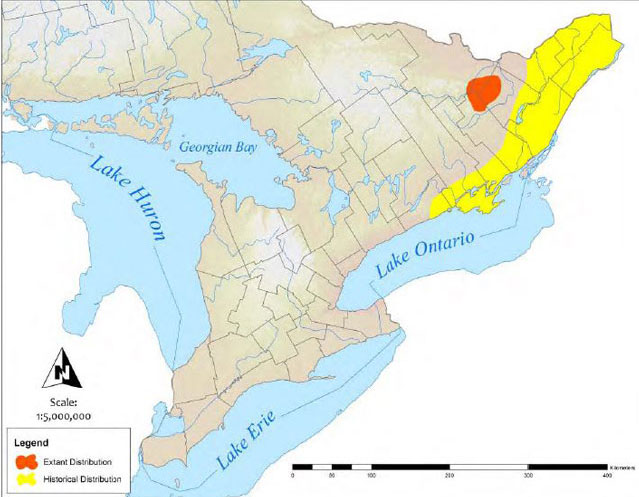

In Canada it is known only from south-eastern Ontario: Four historic locations (Brighton, Belleville, Britannia, Ottawa) and three extant locations (Billa Lake, Lanark County; Arcol Road, Frontenac County; and Calabogie Peak, Renfrew County) (Figure 6). Surveys at historic locations and surrounding areas have not resulted in rediscovery; therefore, the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is considered extirpated from those sites. The Billa Lake site was discovered in 2004 and the Arcol Road site was discovered in 2007.

The Calabogie Peak site was discovered in 2009, after the COSEWIC status report was completed. Even though detailed inventories and thalli counts have not been completed this new population is estimated to be the largest population of the three, with an estimated 71 individuals, 16 of which are fertile, almost doubling the entire population of the previous two localities.

Currently, the extant distribution in Ontario appears to be centered in the east portion of the province in Lanark, Renfrew and Frontenac Counties (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Historical and extant distribution of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in Ontario

(based on COSEWIC in press)

Enlarge Figure 6. Historical and extant distribution of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in Ontario

1.4 Habitat needs

Pale bellied-Frost Lichen requires mature to old-growth deciduous forests with tree species of suitable bark pH, calcium content, and moisture holding capacity, usually thick barked Eastern Hop-hornbeam. The site requires high levels of fog or high relative humidity with moderate to high levels of shade (Figure 7). The three Ontario extant sites appear to have a suppressed or sparsely-vegetated relatively open under story that potentially allows for air circulation (Figure 8). Host trees are most typically found on or just over the crest of a northwest, north or northeast facing forested slope with a moderate (25 to 45 degree) grade (Figures 3a, 4a, and 8) (COSEWIC in press).

High levels of humidity in forest stands are a function of several factors often working in unison. Forests with northern and eastern aspects (NW, N, NE and E) are often cooler and wetter compared to southern and western aspects (SE, S, SW and W) (Oliver and Larson, 1996). Increased levels of shade reduce evaporation rates by shielding the area from the sun’s rays. The relationship of proximity to an available source of water (e.g., creek, river or lake) and required humidity levels is unknown but undoubtedly a close proximity contributes to the intensity and duration of the low altitude humidity (i.e., fog) of the three extant sites (Brodo pers. comm., Author’s personal observations).

Old trees, specifically those species identified as suitable substrates, have thick rough bark allowing for increase water holding capacity and retention. The pH of the substrate is also very important (Brodo 1974).

Figure 7. A typical example of crown/canopy closure at a Pale-bellied Frost Lichen forest stand

Figure 8. A typical example of the understory composition at a Pale-bellied Frost Lichen site

1.5 Threats to survival and recovery

Most of southern Ontario’s old-growth forests were destroyed by logging, forest fire or settlement between the mid 1700's and the early 1900's (Landowner Resource Center 1999). Many of the remaining forest stands in southern Ontario do not provide suitable habitat for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen since they lack interior forest characteristics. Further, many of the remaining stands lack old, thick barked elm, ash or ironwood trees that provide Pale-bellied Frost Lichen with suitable substrates to grown on (Landowner Resource Center 2000). Interior forest characteristics differ from forest edges by being cooler, less windy, humid, and exhibit ecological integrity and stability (Landowner Resource Center 2000). See the supporting narrative for an explanation of ecological integrity and stability.

Since, lichens are poikilohydric organisms (not able to regulate their uptake or loss of water) they are dependant on an atmospheric supply of water and organic nutrients from precipitation, dew, or fog (humidity) and as such, lichens are particularly sensitive to micro-climatic changes (Esseen and Renhorn, 1998, Kivistö and Kuusinen 2000). Well documented edge effects, including changes in microclimates, such as: increased wind speeds, higher radiation, larger variations in temperature, and lower humidity levels have implications to lichen diversity especially those species dependant on interior forest habitats (Esseen and Renhorn 1998, Kivistö and Kuusinen 2000, Rheault et al. 2003). Lichens of old-growth forests are particularly sensitive to forest fragmentation (Kivistö and Kuusinen 2000, Rheault et al. 2003). A study by Jørgensen 1978) showed that an old-growth dependant threatened foiliose lichen Boreal Felt Lichen (Erioderma pedicellatum) or vanished from a single location in Sweden due to alterations to its required microclimatic conditions following a cutting of the surrounding forest.

It is difficult to determine the exact distance required for maintenance of the existing microclimates at each site, because the distance may differ for each site based on factors such as: topography, forest condition, tree age and health, soil properties, such as drainage, texture, and texture, etc. (Environment Canada 2007). That being said, edge effects have been shown to have a measurable impact on common forest lichen species up to a distance of 50m with rarer lichen species especially adapted to humid, shaded microclimates requiring more (Kivistö and Kuusinen 2000, Rheault et al. 2003).

Guidelines for protecting interior forest species in Southern Ontario have recommended 100 to 200 m distances from the forest edge be maintained to protect against alteration to interior microclimate characteristics (Environment Canada 2006).

The loss of interior old-growth forests, with interior microclimates, has undoubtedly resulted in the loss of forest stands available to Pale-bellied Frost Lichen. The elimination of these forests has reduced the number of forest stands that have the required high humidity and old, thick barked elm, ash or Eastern Hop-hornbeam trees.

Loss and degradation of suitable habitat continues to threaten the persistence of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen because of changes to forest structure caused by site alteration (e.g., logging operations, forest fires, urban development and aggregate extraction).

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) deposition has been frequently linked to reduced lichen species diversity and abundance in an ecosystem (LeBlanc and De Sloover 1970, Nash 1996, Brodo et al. 2001). High levels of deposition result in the suppression of photosynthesis and respiration in lichens. Effects of high levels of SO2 are first seen in the loss of SO2 sensitive species from an ecosystem. Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is considered relatively sensitive to SO2 (COSEWIC in press). Although mean annual SO2 deposition levels have decreased in the past 30 years, the elevated deposition levels prior to 1971 have undoubtedly led to the decline of Pale-bellied Frost lichen and other rare and sensitive lichen species, and have left a lasting effect on the ecosystem, resulting in a time-lagged recovery of forest ecosystems and their floral and fauna components (COSEWIC in press).

If the current climate warming trend continues, the resulting elevation of mean seasonal temperatures could result in changes to evaporation rates, relative humidity levels, and the frequency and duration of fog events that are expected to have negative impacts on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen. It has been suggested that humidity levels lower than 50 percent may have a negative impact on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (COSEWIC in press).

Historically Pale-bellied Frost Lichen was most often recorded growing on elm bark. The loss of American Elm trees as a result of the Dutch Elm Disease (Leadbitter et al. 2002) has reduced the amount of available substrate for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen colonization, and may provide one explanation for why the extant populations of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen now appear to be limited to growing on Eastern Hop-hornbeam bark in remnant old-growth forests.

A number of lichen species are subject to herbivory by snails and slugs (Gastropods). While no evidence has been given of snail and slug herbivory on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen, it has been documented for other lichen species in Norway, on Lungwort (Lobaria pulmonaria) (Vatne et al. 2010) and in Ontario on Flooded Jellyskin (Leptogium rivulare) (Rob Lee pers. comm. 2010). Gastropod herbivory has been shown to increase over calcareous soils (Vatne et al. 2010). Research being conducted by the lichenologist Rob Lee in the Ottawa area, studying the effects of the feeding habits of relatively recent invasions and population boom, of non-native slugs (Arion sp.), has concluded that the impacts of these slug species are a legitimate cause for concern to lichen populations where these slugs are known to exist.

The outer bark of Eastern Hop-hornbeam is loosely attached and easily sloughs off as the tree ages. Physical removal of the bark, during forestry operations or recreational activities (e.g., hiking, skiing, and/or biking), could result in the removal of bark with Pale-bellied Frost Lichen growing on it. Repetitive bark removal, with the lichen directly on it at any of the sites, could severely reduce or eliminate the population. Repetitive removal of lichenized or non-lichenized bark from the host trees, or suitable habitat trees, could result in the trees becoming susceptible to disease; reduce the likelihood of colonization/population expansion, or potentially resulting in tree mortality.

Alterations to hydrological regimes may also have an impact to Pale-bellied Frost Lichen sites. A reduction in duration or intensity of hydrological periods could result in reduced humidity levels rendering the site unsuitable for retention or colonization.

1.6 Knowledge gaps

Given the small and inconspicuous nature of the species, the knowledge required in finding and identifying it, and the relatively small (but growing) number of persons in Ontario who make a practice of recording lichen occurrences, it is not surprising that there are major gaps in our knowledge of the distribution of the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen, even within the three forests where it is known to be extant.

Historical accounts of Pale-bellied Frost lichen, especially in Ontario, provide little specific information. Vague collection labels make relocating historic sites and inferring historical habitat needs a challenge (e.g., "Brighton" or "Belleville", "on trunks and rocks" or "on old rails and trees"). Therefore, the habitat requirements have been determined by examining the three extant locations, although they represent a relatively small sample size.

Even though historic information is not clear, a relatively large amount of suitable habitat has been surveyed over the past century by qualified lichenologists, yielding only a few new locations. The complete distribution pattern of the species in Ontario, and the reasons for this pattern, are therefore important knowledge gaps. Additional inventory work might find more locations, but the species is clearly not widespread in Ontario, suggesting a habitat specialization that is not clearly understood.

Thus, the specific biology and ecology of the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is not well understood. Knowledge gaps include: detailed information on its lifespan, growth rate, life history, physiology, dispersal, genetic diversity, population dynamics, minimum viable population size, reaction to translocation in suitable habitats, reaction to ecological disturbance (e.g., various timber harvest methods and intensity), and sensitivity to air pollutants and acid deposition. Dispersal is of particular interest as the species is found in a limited number of locations. The potential role of succession, competition from mosses and other lichens, and susceptibility to herbivores (i.e., snails and slugs) are also knowledge gaps.

1.7 Recovery actions completed or underway

To date several recovery activities specifically related to Pale-bellied Frost Lichen have been undertaken; all of which have focused on inventory, monitoring and outreach.

Several species-at-risk biologists working for the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) have been given presentations on rare lichens found in their district, or adjacent districts, with an emphasis on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen. The biologists were provided with photographs of the species and descriptions of the locations and habitat (by Lewis and Lee in 2009-2010 - Bancroft, Kemptville and Pembroke Districts).

The Calabogie Mountain site is on private land. The landowners were notified, by a private consultant in 2009, that Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is located on their property.

Since the preparation of the COSEWIC status report (In press) in 2007, additional surveys in southern Ontario have been completed by qualified lichenologists (i.e., Rob Lee, Irwin Brodo and Chris Lewis).

In 2010, Lewis and Lee provided the MNR Natural Heritage Information Center (NHIC) with updated (i.e., 2007-2010) element occurrence (EO) data of all three extant sites in Ontario.

A few websites featuring Pale-bellied Frost Lichen are now available on the Internet, including national and provincial species at risk websites and a few private websites providing education to the general public (2009).

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

Pale-bellied Frost Lichen has never been overly abundant in Ontario. The recovery goal is to maintain the size and distribution of all extant and newly discovered populations of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in Ontario, with hopes of population increases through habitat protection, and to fill in some of the identified knowledge gaps.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

The protection and recovery objectives are listed in order of priority in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or recovery objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Protect individuals and habitat at all known occurrences of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen. Incorporate specific protection into relevant municipal Official Plans, forestry management plans, and/or future development plans. |

| 2 | Provide communication and outreach to the landowners, municipalities, and planners. |

| 3 | Inventory and map all known Pale-bellied Frost Lichen locations, populations and habitats by 2015 to provide a quantitative baseline for future monitoring and initiate a monitoring program. |

| 4 | Conduct additional inventory for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in suitable habitats. |

| 5 | Conduct research to address knowledge gaps for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 2. Approaches to recovery of the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in Ontario

| Action | Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Critical | Short-term | Protection |

|

|

|

Critical | Short-term | Protection |

|

|

|

Critical | Short-term | Protection |

|

|

|

Beneficial | Long-term | Protection, Outreach, Stewardship |

|

|

|

Necessary | Short-term | Communications and or Stewardship |

|

|

|

Critical | Short-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

|

|

|

Beneficial | Short-term | Monitoring and Assessment |

|

|

|

Necessary | Ongoing | Inventory |

|

|

|

Critical | Long-term | Research |

|

|

|

Necessary | Long-term | Research |

|

|

|

Necessary | Long-term | Research |

|

|

Supporting narrative

The proposed approaches to recovery procedures emphasize habitat protection. Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is largely dependant on forest stands that have maintained ecological integrity and continuity (both temporal and spatial). In this instance maintenance of ecological integrity and stability refers to a forest ecosystem that is not subject to anthropogenic disturbances; with anthropogenic disturbances being identified as a human-induced discrete events in time or space that unnaturally change the physical (biotic or abiotic) conditions of that ecosystem. While some forest organisms are resilient to forest disturbance, and some natural disturbances are normal (e.g., wind throws, forest fires), Pale-bellied Frost Lichen is reliant on established stable ecosystems and is sensitive to disturbance. As such, it is recommended that the protection of suitable forest stands, by prohibiting anthropogenic disturbance, is implemented to maintain suitable habitat for this species.

Other species that could benefit from the habitat protection for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen habitat protection under the ESA could include: American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius), Butternut (Juglans cinerea), interior forest birds and other flora and fauna dependant on interior forests.

The recommended measures should permit natural forest succession processes to proceed unimpeded by human activity. Implementation of the recovery strategy could yield positive environmental benefits due to retention of remnant old-growth forests, improved understanding of the ecology of lichens and lichen communities in southern Ontario, and the recovery of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen.

Recovery of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen would depend upon appropriate habitat management at both the site and landscape level. The required habitat would first have to be identified and mapped at the site level and protected by a combination of management actions, stewardship initiatives and legal tools. Any shortcomings would need to be addressed appropriately.

All Ontario landowners and land managers with extant populations of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen are aware of the presence of the species due to previous survey efforts. Continued cooperation of landowners and land managers of existing, expanding or newly discovered populations is essential to this species' recovery. Stewardship efforts could include developing voluntary stewardship agreements, increasing landowner awareness of the federal government’s Ecological Gifts Program (EGP) and Habitat Stewardship Program (HSP), conservation easements and other stewardship programs.

A reliable, repeatable and long-term monitoring protocol should be developed and implemented to measure the abundance and distribution of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen at extant sites. Baseline data should be established for accurate comparisons and trend establishment. A protocol is also required for monitoring anthropogenic and natural threats to Pale-bellied Frost Lichen populations and habitat in order to assess the effectiveness of management actions. Landscape and site-level habitat variables, such as the stand age, humidity levels, canopy closure, etc. should be monitored to help understand the species' biology and guide recovery.

Surveys in suitable habitat adjacent to known sites should be conducted in conjunction with monitoring of existing populations to determine if there is any successful dispersal.

Education should raise the profile of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen and its old-growth habitat to garner support for its protection on public lands. Training workshops should teach landowners, managers and other interested stakeholders survey techniques for identifying Pale-bellied Frost Lichen and potential habitat that will support its protection and potentially the identification of new populations. Public education should also be used to increase awareness of very broad-scale threats such as acid rain and climate change that may indirectly affect Pale-bellied Frost Lichen.

A research program should be developed, prioritized and initiated to address information gaps in order to guide recovery actions, particularly with respect to dispersal, population dynamics and habitat requirements. Once more is known about its ecology, the potential for translocation of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen into unoccupied suitable habitat should be evaluated. Even though attempts to translocate the Golden hair lichen (Teloschistes flavicans), a threatened lichen species in the United Kingdom, into what was thought to be suitable habitat, have not been very successful research into translocation of Pale-bellied Frost lichen may prove to be a viable option.

2.4 Performance measures

Success of the recovery goal and objectives should be measured through demographic data on Pale-bellied Frost Lichen populations, habitat attributes and involvement of landowners and land managers in recovery efforts. Recovery can be considered successful if the following performance measures have been met:

Recovery objective 1:

- Protection of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen and its habitat at known sites is incorporated into all relevant planning documents and management plans.

- Stewardship agreements are in place for all known sites on private lands.

- All occupied habitat is identified, mapped and protected.

Recovery objective 2:

- Education materials, a communication strategy and training have been developed and delivered to landowners, land managers, the public and other stakeholders for all known sites.

Recovery objective 3:

- Establishment of a qualitative population census baseline.

- Surveys at any newly discovered and historical sites have been conducted, with any new populations incorporated into recovery efforts, and all surveyed areas documented. All new distribution data submitted to the Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre in a timely manner.

- Using knowledge of habitat requirements implement targeted surveys for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen.

- GIS modelling could be implemented to focus the search effort

Recovery objective 4:

- Using knowledge of habitat requirements implement targeted surveys for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen.

Recovery objective 5:

- Research into Pale-bellied Frost Lichen biology and ecology, particularly relating to dispersal, population dynamics and habitat requirements, has been initiated and results have been incorporated into recovery efforts.

- Based upon the findings of other research, the feasibility of introduction of Pale-bellied Frost Lichen into unoccupied suitable habitat has been evaluated.

- A prioritized list of outstanding research topics has been developed.

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Due to the limited known distribution of the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen in Ontario, and until such time as it can be determined if, in fact, the species is restricted to just the three known forest stands, it is recommended that the area prescribed as habitat in the habitat regulation include only the locations where the species is known to occur.

Each location is described below:

- "Billa Lake"/Darling Long Lake: Old-growth forests located at the east end of Darling Long Lake on the south shore Lot 18, 19 Con 7 Darling Township;

- Arcol Road: Forest on Arcol Road, 1.5 to 2.7 km north from intersection of North Shore Estates Lane on the north shore of Canonto Lake Lot 19, 20 South Canonto Township; and

- "Calabogie Peak" 5.4 km West of the Town of Calabogie: Old-growth forest 40 m southwest of the terminus/cul-de-sac of Mary Joanne Drive extending 1000 m southeast along the slope ridge to a point 130 m northwest of the intersection of Beaches Lane and Barrett Chutes Road. Con 3 Lots 16, 17, 18, 19 and Con 2 Lots 17, 18, 19 Blithfield Township.

Edge effects caused by forest disturbance have been shown to impact groups of common forest lichens up to a distance of 50 m (Esseen and Renhorn 1998, Rheault et al. 2003). Relatively rare interior forest lichen species that are reliant on old-growth forest characteristics and sensitive to microhabitat disturbance, like the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen, would potentially require greater distances to maintain their required habitats (Environment Canada 2007).

The Canadian Wildlife Service (2006) has shown that deep forest-interior species, species that are most sensitive to edge effects, are only found to inhabit areas that are at least 200 m from the forest edge. An initial buffer of 100 m could be used to protect the habitat from edge effects while a second 100 m buffer would maintain deep interior forest suitable for edge intolerant species.

Figure 9. Schematic of habitat regulation recommendation for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen

Based on these findings it is recommended that the minimum area that should be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation for Pale-bellied Frost Lichen, include a 200 m radius surrounding each host tree, or colony of host trees.

Glossary*

Anthropogenic: effects, processes, or materials are those that are derived from human activities, as opposed to those occurring in biophysical environments without human influence.

Apothecium (pl. Apothecia): Disk shape or cup-shaped fruiting bodies of a lichen containing spore-filled sacs (asci)

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

| Number | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 1 | critically imperilled |

| 2 | imperilled |

| 3 | vulnerable |

| 4 | apparently secure |

| 5 | secure |

| NR | not yet ranked |

Ecological unit: Populations of organisms considered together with their physical environment and the interacting process amongst them.

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Foliose Lichen: A type of lichen characterised by a dorsiventral leaf-like thallus with the lower surface largely free from the substrate, at least in part, and the upper surface different in some way from the lower surface.

Isidia: small growths on the upper cortex functioning as vegetative propagules, always covered with a cortex, can take on several forms (i.e. cylindrical, granular, globose, etc.).

Lobule (Lobulate): In reference to isidia resembling small lobes, or in reference to foliose lichen that have small lobes.

Macrolichen: Lichen species that are not crustose.

Propagule: a structure for reproductive dispersal, either sexual (e.g. ascospore) or asexual (vegetative; e.g. soredium).

Pruina: A fine, white, powder-like covering on the upper cortex or on the disk of apothecia.

Squarrose: branching at right angles (e.g. the short side branches of certain rhizines).

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) list: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Soradium (pl. soredia): a vegetative dispersal unit consisting of a few algal cells surrounded by hyphae but not covered with a cortex.

Thallus (Thalli): the vegetative body of a lichen, consisting of both fungus and an alga.

References

Brodo, I.M. 1974. Substrate ecology. In V. Ahmadjian and M.E. Hale (Eds.) The Lichens, Academic Press, New York. Pp. 401-441.

Brodo, I.M., Sharnoff, S.D. and Sharnoff, S. 2001. Lichens of North America. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

COSEWIC. In press. COSEWIC and status report on the Pale-bellied Frost Lichen (Physconia subpallida) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. viii + 42 pp.

Environment Canada, 2007. Recovery Strategy for the Boreal Felt Lichen (Erioderma pedicellatum), Atlantic Population, in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. viii + 31 p.

Environment Canada, 2006. How much habitat is enough? A framework for guiding habitat rehabilitation in the Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Second Edition. Minister of the Environment. 80pp.

Esseen, P. and Renhorn, K. 1998. Edge effects on an epiphytic lichen in fragmented forests. Conservation Biology 12(6): 1307-1317.

Esslinger, T.L. 1994. New species and new combinations in the lichen genus Physconia in North America. Mycotaxon 51: 91-99.

Jørgensen, 1978. The lichen family Pannariaceae in Europe. Opera Botanica 45:1-124.

Kivistö, L. and Kuusinen, M., 2000. Edge effects on the epiphytic lichen flora of Picea abies in the middle boreal Finland. Lichenologist 32(4): 387-398.

Landowner Resource Center. 1999. Extension Notes – The Old-Growth Forests of Southern Ontario. Landowner Resource Center, Queen’s Printer for Ontario. 8 pps.

Landowner Resource Center. 2000. Extension Notes – Conserving the Forest Interior: A Threatened Wildlife Habitat. Landowner Resource Center, Queen’s Printer for Ontario. 12 pps.

Leadbitter, P., Euler, D. and Naylor, B. 2002. A comparison of historical and current forest cover in selected areas of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence forest of central Ontario. The Forest Chronical 78:522-529.

LeBlanc, F. and J. De Sloover. 1970. Relation between industrialization and the distribution and growth of epiphytic lichens and mosses in Montreal. Canadian Journal of Botany. 48:1485-1496.

Lee, Rob. 2010. Lichenologist. Personal Communication.

Nash, T. 1996. Lichen Biology. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 496 pp.

Oliver, C.D. and Larson, B.C. 1996. Forest Stand Dynamics – Updated Edition. John Wiley and Sons, New York, New York. 520 pps.

Rheault, H., Drapeau, P., Bergeron, Y., and Esseen, P. 2003. Edge effects on epiphytic lichens in managed black forests of eastern North America. Canadian Journal of Forestry Research 33: 23-32.

Vatne, S., Solhøy, T., Asplund, J., and Gauslaa, Y. 2010. Grazing in the forest lichen Lobaria pulmonaria increase with gastropod abundance in deciduous forests. The Lichenologist 42(5): 615-619

*For additional technical lichen term definitions refer to Brodo et al. 2001.