Protecting Groundwater to Protect Health

Outlines how groundwater can become contaminated and the effects of treatment.

Contaminated groundwater can be dangerous to health. Human and animal fecal matter can cause serious diseases, poisoning and even death.

Even though your water may appear to be fine, there are many possible contaminants that you can't taste, see, or smell.

Bacteria and other micro-organisms

Drinking water is tested for organisms which are called indicator bacteria. The presence of these bacteria indicates that your well water may have become contaminated with harmful bacterial from sources such as animal or human waste. These indicators act as an early warning signal to let you know that there may be health risks with drinking the water because it is more likely to contain harmful organisms (pathogens).

There are two indicator organisms that labs will test for when you submit a sample. These are E. coli and total coliforms.

E. coli are a group of bacteria that live in the intestines of warm-blooded animals. These bacteria indicate recent fecal contamination from sources such as livestock waste or human sewage. If any E. coli are found in your water sample, it indicates that there is a problem, and that the water is unsafe for drinking without treatment.

Total coliforms are a general family of bacteria that is found in animal wastes, soil, and vegetation. These bacteria indicate possible surface water contamination in your well water, and provide an early warning signal that there may be a problem with using your water supply for drinking purposes.

Chemical contaminants

The most common potentially harmful chemical contaminants in a rural setting are nitrates and nitrites. The presence of nitrates and nitrites in your water can be the result of the use of commercial fertilizers and the presence of discharge from human or animal waste disposal and/or treatment facilities. Infants less than six months old can become sick from drinking formula or eating cereals made with water containing nitrites or high in nitrates, which become converted into nitrites during digestion. Nitrites reduce the amount of oxygen in the blood, which can result in "blue baby syndrome."

How groundwater gets contaminated

Human activities in the area near your well can lead to groundwater contamination:

- Poorly constructed and poorly maintained wells.

- Improperly plugged wells and cross-connections such as back siphoning from spray tanks into wells.

- Over-use of soil treatments such as manure, fertilizers and/or pesticides.

- Leakage from waste facilities such as manure and wastewater storage, septic tanks, municipal sewers and landfills.

- Spills on the ground, e.g. fuel and pesticide spills.

- Plow-down of legume crops.

- Disposal of materials such as industrial solvents, hazardous household or farm wastes, prescription drugs and chemicals to septic system or onto the ground.

- Leakage from underground and aboveground fuel storage tanks.

- Leakage from vehicles, workshops and bulk storage.

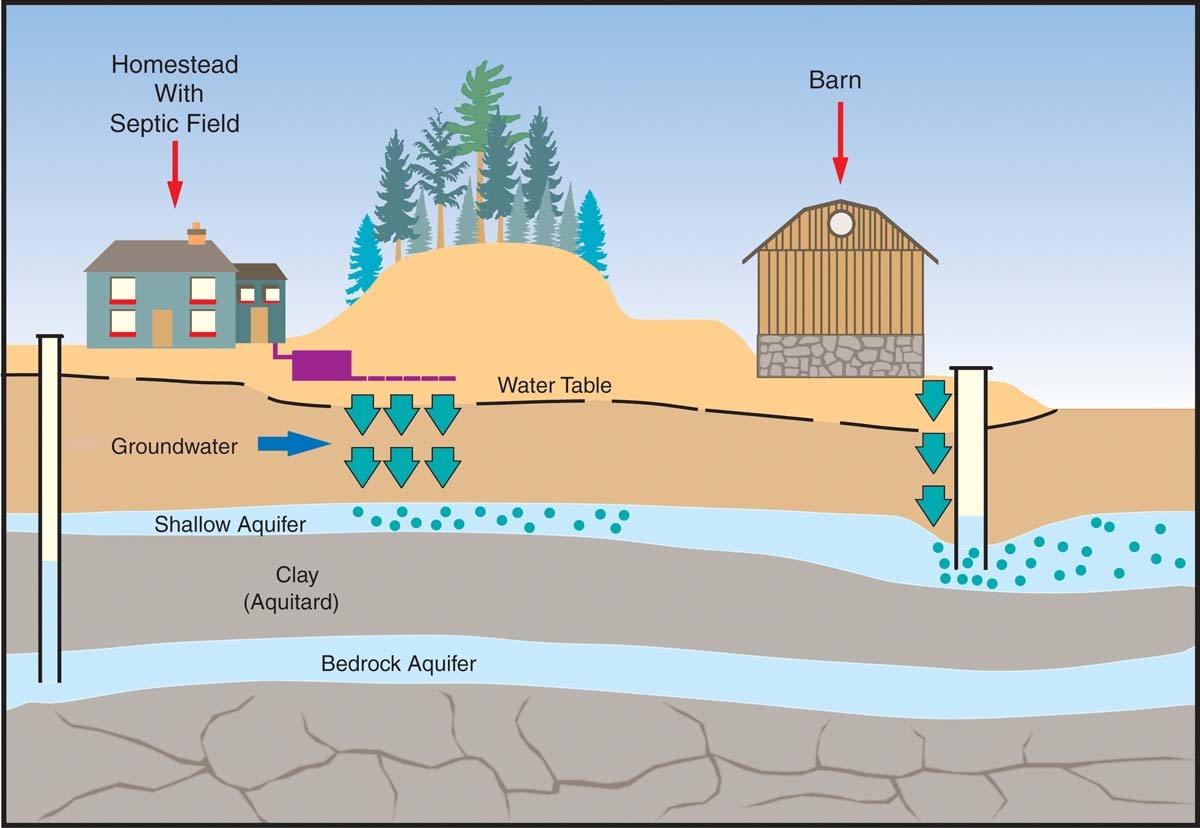

Figure 1 illustrates how human and animal waste can contaminate groundwater. When surface water travels down through soil to ground water, it can take pathogens with it. Fortunately, soils can have a cleansing effect that removes pathogens from the water. But if pathogens are able to bypass soil’s natural cleansing action, they can survive and be introduced into groundwater. The shorter the travel time, the greater the risk of contamination.

Figure 1

Figure 1 Credit: Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs

Weather can also affect the soil’s cleansing action. Very heavy rains or flooding can move contaminants through soil at faster rates than normal or result in the creation of a short-cut channel to the well.

The vulnerability of each aquifer (water-bearing layer of soil or rock) is unique. Factors that determine vulnerability include the type of soil and/or rock in the aquifer, its depth under the surface and whether or not it is protected by an aquitard (an unbroken layer of dense rock or soil, such as clay, that retards free flow of water between aquifers).

Have you built an expressway for pathogens?

Some of the facilities or activities on your property might be providing pathogens with these bypass routes. A well that is poorly constructed or poorly sealed provides one route. An on-site septic system that is improperly or poorly designed, maintained or located provides another route.

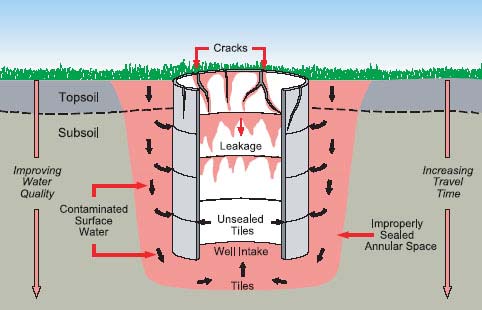

As shown in Figure 2, the arrows show the pathways that pathogens can follow to get into a shallow dug well when it is improperly constructed or deteriorated with age. The red shading indicates the annular space, which is the space outside the well casing that was created when the hole for the well was made. In this well, the annular space is unsealed at the top, and acts as a duct for contaminated surface water to pass down into the well intake at the bottom. To make matters worse, contaminated surface water can also enter the well through unsealed tile joints and cracks. (Note: To improve clarity of the diagram, the necessary aboveground portion of the well is not shown here.)

Figure 2

Figure 2 Credit: Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

How does treatment reduce or eliminate contamination?

Various filtration processes can remove particles that may hide or protect pathogens from the effect of disinfection. Disinfection processes, such as ultraviolet (UV) light and chlorination kill or inactivate harmful organisms. Treatment provides a safeguard from contamination, which is more prevalent when a well is improperly constructed or maintained, or is a shallow, dug well. Different water sources call for different levels and methods of treatment to ensure safe, clean drinking water. The cleaner your source water, the less chance of contamination

The most commonly used form of disinfection for small drinking water systems is UV light disinfection. This is an effective treatment for pathogens. UV disinfection is usually associated with a cartridge filter to remove particles in the source water that may shield harmful organisms from disinfection.

Contact a professional engineer with experience in sanitary engineering for more information about water treatment systems and when selecting, installing and operating a treatment system. All chemicals and materials that come into contact with drinking water should be National Standards Foundation (NSF) certified. Equipment carrying the NSF certified trademark has been thoroughly checked for performance and the manufacturing facility is inspected annually. Check for the appropriate NSF standard number for your treatment needs.

For more information

For more information about drinking water, visit Ontario’s drinking water page or call the ministry’s Public Information Centre at 1-800-565-4923.

PIBS 6969e01