Recovery strategy for the Least Bittern

Read the recovery strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis), a species of bird at risk in Ontario.

Cover photo by Mike Burrell.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 5 pp. + Appendix.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016

ISBN 978-1-4606-8989-9 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4606-8993-6 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration and images in the appended federal recovery strategy) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Acknowledgments

We thank Doug Tozer of Bird Studies Canada and Chris Risley of Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, for providing information that assisted in the development of this recovery strategy addendum.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

Executive summary of Ontario’s recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The species is also listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) in Canada in 2014 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Since the publication of the federal recovery strategy, survey efforts have resulted in the submission of new records of Least Bittern to the Natural Heritage and Information Centre (NHIC), some of which may occur outside the designated critical habitat. Pending verification, these new locations, beyond what are currently identified as critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy for the Least Bittern, should also be considered in developing a habitat regulation for the species.

Executive summary of Canada’s recovery strategy

The Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) is North America’s smallest heron. It breeds in freshwater and brackish marshes with tall emergent plants interspersed with open water and occasional clumps of woody vegetation. The species was designated as Threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2001 and 2009, and has been listed with the same status under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) since 2003.

Around 2-3% of the estimated 43,000 North American pairs are found in Canada, where they are distributed throughout southern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and possibly Nova Scotia. Because of the species' secretive habits and the difficulties of surveying its habitat, population size and trend estimates are imprecise.

Wetland loss and degradation as well as impaired water quality are the primary threats to the Least Bittern throughout its range. Other threats include regulated water levels, invasive species, collisions (with cars and man-made structures), recreational activities, and climate change.

There are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Least Bittern. Nevertheless, in keeping with the precautionary principle, a recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible.

The population and distribution objectives for the Least Bittern are to maintain and, where possible, increase the current population size and area of occupancy in Canada. Broad strategies and approaches to achieve these objectives are presented in the Strategic Direction for Recovery section.

Critical habitat is partially identified for the breeding habitat. It corresponds to the suitable habitat within 500 m of records of breeding activity since 2001. A total of 115 critical habitat units are identified, 10 of which are located in Manitoba, 54 in Ontario, 48 in Quebec and 3 in New Brunswick. A schedule of studies outlines key activities to identify additional critical habitat at breeding, foraging, post-breeding dispersal, moulting and migration stopover sites.

One or more action plans will follow this recovery strategy and will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by 2019.

Adoption of federal recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) is listed as threatened on the SARO List. The species is also listed as threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) in Canada in 2014 to meet its requirements under the SARA. This recovery strategy is hereby adopted under the ESA. With the additions indicated below, the enclosed strategy meets all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Table 1. Species assessment and classification of the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis). The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations within, and for other technical terms in this document.

| Assessment | Status |

|---|---|

| SARO list classification | Threatened |

| SARO list history | Threatened (2008), Threatened – Not Regulated (2004) |

| COSEWIC assessment history | Threatened (2009), Special Concern (1988) |

| SARA schedule 1 | Threatened (2009) |

| Conservation status rankings | GRank: G5 NRank: N4B SRank: S4B |

Distribution, abundance and population trends

Section 3.2 of the federal recovery strategy for the Least Bittern (Appendix 1) provides a description of the population and distribution of Least Bittern in Ontario. Since the publication of the federal recovery strategy, many observations of Least Bittern have been reported to Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC) The NHIC has not yet processed these records, but there is a high probability some of them will become element occurrences. The locations on the following list may be outside the designated critical habitat shown in Appendix B of the federal recovery strategy for the Least Bittern (Appendix 1) and should be considered in developing a habitat regulation for this species.

New locations of Least Bittern that have been reported to the NHIC since the federal recovery strategy, and identification of critical habitat, was published are listed below. The following are recent observations that may become new element occurrences:

- Algoma District – Echo Bay Marsh

- Frontenac County – Howe Island, Johnson Bay

- Frontenac County – Wolfe Island, Bayfield Bay

- Halliburton County – Horseshoe Lake

- Kawartha Lakes – Logan Lake

- Kawartha Lakes – Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands Provincial Park

- Lanark County – Appleton Wetland

- Lanark County – McEwan Bay Wetland

- Lanark County – Murphys Point Provincial Park, Black Creek

- Leeds and Grenville – Leeder’s Creek Wetland Complex

- Peel – Heart Lake area

These new locations should be considered when the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry proposes a habitat regulation.

A recent study by Tozer (2016) found a significant decline in occurrence rates for the Least Bittern in Great Lakes Marsh Monitoring Program survey sites over the past two decades. This may or may not be reflective of the population in the Ontario Great Lakes basin.

Habitat needs

Tozer (2016) reported that Least Bitterns are more likely to occupy and colonize larger wetlands compared to smaller ones, and Quesnelle et al. (2013) found that Least Bitterns are more likely to occupy wetlands with a high proportion of wetland cover in the surrounding landscape. Tozer (2016) also noted that high quality Ontario habitat for most declining marsh-dependent breeding birds consists of robust-emergent-dominated but interspersed wetlands free of Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and European Common Reed (Phragmites australis australis), with limited urban land use and a high proportion of wetlands in the surrounding landscape.

Threats to survival and recovery

Tozer (2016) suggests that invasive Purple Loosestrife and European Common Reed are a threat to most of southern Ontario’s declining marsh-dependent breeding bird species. Additional threats include Blue Cattail (Typha × glauca) if it results in a loss of open patches of deep water and interspersion, which are preferred by Least Bittern (Tozer et al. 2010).

Approaches to recovery

New information under the section on Threats To Survival And Recovery above is not discussed in the federal recovery strategy. The federal recovery strategy does not include recovery actions to address these threats. Therefore, consideration should be given to relevant recovery actions that would help to address these new threats when developing recovery initiatives for this species in Ontario.

Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below will be one of many sources considered by the Minister, including information that may become newly available following completion of the recovery strategy, when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal recovery strategy provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA. Pending verification, the new locations noted above, beyond what is currently identified as critical habitat in the federal recovery strategy for the Least Bittern in Canada (Appendix 1), should also be considered in developing a habitat regulation for this species.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

NR = not yet ranked

Element occurrence: The basic unit of record for documenting and delimiting the presence and extent of a species on the landscape. It is an area of land and/or water where a species is, or was, present, and which has practical conservation value.

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Quesnelle, P.E., L. Fahrig, and K.E. Lindsay. 2013. Effects of habitat loss, habitat configuration and matrix composition on declining wetland species. Biological Conservation 160:200-208.

Tozer, D.C. 2016. Marsh bird occupancy dynamics, trends, and conservation in the southern Great Lakes basin: 1996 to 2013. Journal of Great Lakes Research 42:136-145.

Tozer, D.C., E. Nol, and K.F. Abraham. 2010. Effects of local and landscape-scale habitat variables on abundance and reproductive success of wetland birds. Wetlands Ecology and Management 18:679-693.

Appendix 1. Recovery strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) in Canada

Federal cover illustration: © Benoit Jobin, Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Quebec Region.

Document information

Recommended citation

Environment Canada. 2014. Recovery Strategy for the Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp.

Additional copies

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Également disponible en français sous le titre :

« Programme de rétablissement du Petit Blongios (Ixobrychus exilis) au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2014. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-100-19922-1

Catalogue no. En3-4/127-2015E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years.

The Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency are the competent ministers for the recovery of the Least Bittern, a Threatened species listed in Schedule 1 of SARA, and have prepared this recovery strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. It has been prepared in cooperation with the Provinces of Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada, the Parks Canada Agency, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Least Bittern and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada, the Parks Canada Agency, and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species.

Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Acknowledgments

This recovery strategy was prepared by Vincent Carignan and Benoit Jobin ((EC-CWS) - Quebec Region) based on an initial draft by Andrew Horn (Dalhousie University). Earlier drafts were reviewed by members of the National Least Bittern Recovery Team [Vincent Carignan, chair, Ron Bazin (EC-CWS – Prairie & Northern Region), Samara Eaton and Jen Rock (EC-CWS - Atlantic Region), Valerie Blazeski (Parks Canada Agency), Ken DeSmet (Manitoba Conservation), Kari Van Allen and Dave Moore (EC–CWS – Ontario Region), Jon McCracken (Bird Studies Canada), and Eva Katic (National Capital Commission)]; and former members of the recovery team [Laurie Maynard and Barbara Slezak (EC-CWS – Ontario Region), Mark McGarrigle (New Brunswick Department of Natural Resources), Todd Norris (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources), Jennifer Stewart (formerly with EC-CWS – Atlantic Region) and Gershon Rother (formerly with the National Capital Commission)].

Other contributors provided comments on the recovery strategy: Manon Dubé and Ewen Eberhardt (EC-CWS – National Capital Region), Marie-José Ribeyron (formerly with EC-CWS – National Capital Region), Karine Picard, Alain Branchaud and Matthew Wild (EC-CWS – Quebec Region), Diane Amirault-Langlais and Paul Chamberland (formerly with EC-CWS – Atlantic Region), Marie-Claude Archambault, Angela Darwin, Angela McConnell, Krista Holmes, Jeff Robinson and Tania Morais (EC-CWS – Ontario Region), David Bland, Michael Patrikeev and Stephen McCanny (Parks Canada Agency), Corina Brydar and Sandy Dobbyn (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources - Ontario Parks), Jodi Benvenuti, Vivian Brownell, Glenn Desy, Leanne Jennings, Chris Risley, Marie-Andrée Carrière, Shaun Thompson, Don Sutherland, Lauren Trute, Doug Tozer and Allen Woodliffe (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources).

The following individuals provided information on Least Bittern populations and habitat distribution, population trends, life history, survey methods, as well as conservation and management: Nickolas Bartok, Isabelle Beaudoin-Roy, Heidi Bogner, Robert Bowles, Courtney Conway, Glenn Desy, Pierre Fradette, Jonathon French, Christian Friis, Stacey Hay, Gary Huschle, Rudolf Koes, Claudie Latendresse, Soch Lor, Paul Messier, Shawn Meyer, Frank Nelson, Sarah Richer, Dave Roberts, Luc Robillard, Tracy Ruta-Fuchs, François Shaffer, Peter Taylor, Guillaume Tremblay, as well as Breeding Bird Atlas and Marsh Monitoring Program volunteers, and birders in Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and the Maritimes.

Finally, thanks is given to all other parties including Aboriginal organizations and individuals, landowners, citizens, and stakeholders who provided comments on the present document and/or participated in consultation meetings.

Executive summary

The Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) is North America’s smallest heron. It breeds in freshwater and brackish marshes with tall emergent plants interspersed with open water and occasional clumps of woody vegetation. The species was designated as Threatened by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2001 and 2009, and has been listed with the same status under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) since 2003.

Around 2-3% of the estimated 43,000 North American pairs are found in Canada, where they are distributed throughout southern Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and possibly Nova Scotia. Because of the species' secretive habits and the difficulties of surveying its habitat, population size and trend estimates are imprecise.

Wetland loss and degradation as well as impaired water quality are the primary threats to the Least Bittern throughout its range. Other threats include regulated water levels, invasive species, collisions (with cars and man-made structures), recreational activities, and climate change.

There are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Least Bittern. Nevertheless, in keeping with the precautionary principle, a recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible.

The population and distribution objectives for the Least Bittern are to maintain and, where possible, increase the current population size and area of occupancy in Canada. Broad strategies and approaches to achieve these objectives are presented in the Strategic Direction for Recovery section.

Critical habitat is partially identified for the breeding habitat. It corresponds to the suitable habitat within 500 m of records of breeding activity since 2001. A total of 115 critical habitat units are identified, 10 of which are located in Manitoba, 54 in Ontario, 48 in Quebec and 3 in New Brunswick. A schedule of studies outlines key activities to identify additional critical habitat at breeding, foraging, post-breeding dispersal, moulting and migration stopover sites.

One or more action plans will follow this recovery strategy and will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by 2019.

Recovery feasibility summary

In considering the criteria established by the Government of Canada (2009), unknowns remain as to the recovery feasibility of the Least Bittern. Nevertheless, in keeping with the precautionary principle, this recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the unknowns surrounding the feasibility of recovery.

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

Yes. Breeding individuals are currently distributed throughout the Canadian range as well as in the United States.

- Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Yes. Sufficient wetland habitat is available to support the species at its current level. Unoccupied and apparently suitable habitat is also available and additional sites could become suitable after restoration efforts or wetland creation.

- The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Unknown. The main threats to the species and its breeding habitat as well as methods to avoid or mitigate them are known. However, some of these methods need to be refined and tested in Canada. Furthermore, foraging, post-breeding dispersal, moulting and migration stopover sites have yet to be identified and the threats to those sites will need to be specified.

- Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

Unknown. Habitat stewardship, along with wetland management, restoration and creation techniques have proven to be effective for this species although specific management prescriptions need to be developed. Mitigating other threats, such as off-site effects on wetland habitat quality, however, will be a continuing challenge.

1. COSEWIC species assessment information

Date of assessment: April 2009

Common name (population): Least Bittern

Scientific name: Ixobrychus exilis

COSEWIC status: Threatened

Reason for designation: This diminutive member of the heron family has a preference for nesting near pools of open water in relatively large marshes that are dominated by cattail and other robust emergent plants. Its breeding range extends from southeastern Canada through much of the eastern U.S. Information on the population size and exact distribution of this secretive species is somewhat limited. Nevertheless, the best available evidence indicates that the population is small (about 3000 individuals) and declining (> 30% in the last 10 years), largely owing to the loss and degradation of high-quality marsh habitats across its range.

Canadian occurrence: Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia

COSEWIC status history: Designated Special Concern in April 1988. Status re-examined and confirmed in April 1999. Status re-examined and designated Threatened in November 2001 and in April 2009.

2. Species status information

Canada has 2-3% of the Least Bittern reproductive pairs in North America. The species has been listed as Threatened under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) (S.C. 2002, c. 29) since 2003. In Quebec, it has been listed as Vulnerable under the Act respecting threatened or vulnerable species (R.S.Q., c. E-12.01) since 2009. In Ontario, it has been listed as Threatened on the Species at risk in Ontario list since 2004 and regulated under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (S.O. 2007, C. 6) since 2008. As of August 2013, the species had not been listed in Manitoba, New Brunswick or Nova Scotia.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature ranks the global population of the Least Bittern as "Least Concern" (BirdLife International, 2009). NatureServe (2010) conservation ranks for Canada and the United States vary widely as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. NatureServe (2010) Conservation Ranks for the Least Bittern1,2.

| Rank | Jurisdiction rank |

|---|---|

| Global (G) | G5 (Secure) |

| National (N) | Canada: N4B (Apparently Secure) U.S.: N5B, N5N (Secure) |

| Sub-national (S) | Canada: Manitoba (S2S3B) ; Ontario (S4B) ; Quebec (S2S3B); New Brunswick (S1S2B) ; Nova Scotia (SNRB) U.S.: SH (Utah) ; S1 (California, Delaware, District of Columbia, Kentucky, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Oregon, Pennsylvania, West Virginia) ; S2 (Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Vermont) ; S3 (Arizona, Indiana, Iowa, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Virginia, Wisconsin) |

11: Critically Imperiled; 2: Imperiled; 3: Vulnerable; 4: Apparently Secure; 5: Secure; H: possibly extirpated; NR: Not Ranked. B (following a number): Breeding; N (following a number): Non-breeding.

2In most states along the Gulf coast (e.g., Texas, Louisiana, Florida), where it is resident year-round, the species is not listed, and has been recently removed from the federal list of "Species of Management Concern" (USFWS, 2002).

3. Species information

3.1 Species description

Measuring about 30 cm and weighing 80 g, the Least Bittern is North America’s smallest heron (Kushlan and Hancock, 2005). It is brown and buffy overall, with broad buff streaks on its white underside, and a contrasting back and crown that is glossy black in adult males but lighter in females and juveniles. Buff wing patches, which are especially obvious when the bird flushes, distinguish this species from all other marsh birds. When disturbed, the bird uses a rail-like "rick-rick-rick-rick", otherwise its call consists of a repeated "coo-coo-coo" (Sibley, 2000). Further details are provided in the COSEWIC (2009) status report.

3.2 Population and distribution

Global population and distribution

During the nesting season, the Least Bittern can be found from southern Canada to South America, including the Caribbean. There are year-round resident populations in river valleys and coastal areas farther south to northern Argentina and southern Brazil (COSEWIC, 2009; Poole et al., 2009). Isolated migrant populations also breed in Oregon, California, and New Mexico (Figure 1). There are an estimated 43,000 pairs of Least Bitterns in North America (Delany and Scott, 2006).

The migratory routes of the Least Bittern are unknown, but it is presumed that they migrate in a broad front that is locally funneled by north-south oriented peninsulas and coasts such as found in the closely related Little Bittern (Ixobrychus minutus) of Eurasia (Nankinov, 1999). The distribution of the adults during the moulting phase needs further study but the timing of this phase (mid-September to mid-December) suggests it mostly takes place during migration (Poole et al., 2009).

Least Bitterns winter from California to Florida south to Mexico and Latin America. The winter habitat is poorly known, although the species is presumed to occupy brackish and saline swamps and marshes (Poole et al., 2009).

Figure 1. Global distribution of the Least Bittern (from COSEWIC, 2009).

Canadian population and distribution

In Canada, the Least Bittern generally breeds south of the Canadian Shield in Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick and possibly Nova Scotia (COSEWIC, 2009; Figure 2). The species has been reported as a vagrant in other provinces. The Canadian breeding population is estimated at 1,500 pairs (between 1000 and 2800; COSEWIC, 2009; Table 2).

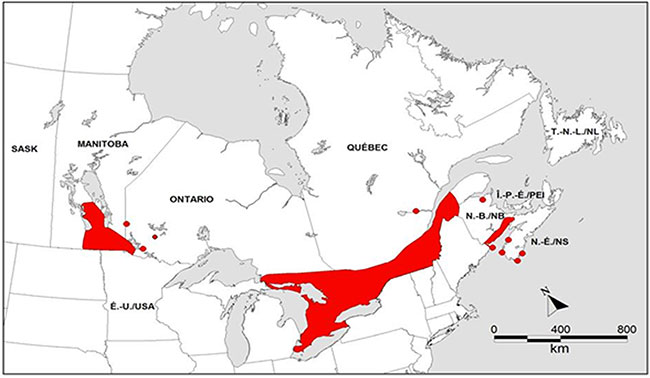

Figure 2. Breeding distribution of the Least Bittern in Canada as of 2012.

Dots indicate locations isolated from the known breeding range, but where birds have been observed during the breeding season (Canadian Wildlife Service, unpublished data). This figure does not take into account immature individuals, sub-adults and non-breeding adults.

Table 2. Estimated numbers of Least Bittern pairs and Breeding Bird Atlas occurrences in Canada.

| Province | Number of breeding pairs (estimated) (COSEWIC, 2009) | Number of atlas blocks (100 km2) in which the species was detected |

|---|---|---|

| Manitoba | ~ 200 | Unavailable |

| Ontario | >500 | 210 (during the 2001-2005 period, 2nd atlas); Cadman et al. (2007) |

| Quebec | 200-300 | 38 (during the 2010-2012 period, 2nd atlas); Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs du Quebec (2012) |

| New Brunswick | unknown | 7 (during the 2005-2010 period, 2nd atlas); Bird Studies Canada (2009, 2010) |

| Nova Scotia | unknown | 0 (during the 2005-2010 period, 2nd atlas); Bird Studies Canada (2009, 2010) |

Despite recent advances in methods to detect the species (Conway, 2009; Johnson et al. 2009, Jobin et al. 2013) which have led to increases in reported numbers of breeding individuals, there is a general consensus that the species has declined (Sandilands and Campbell, 1988; Austen et al., 1994; James, 1999; Environment Canada, 2007; Poole et al., 2009). In Canada, this tendency has been observed in the core of the species' range with an average annual decline of 10.6% (95% CI = -6.9% to -14.3%) in the Great Lakes Basin from 1995 to 2007 (Archer and Jones, 2009). An analysis of the data from the Ontario breeding bird atlases yielded a similar trend (-10%/year, 95% CI = -5% to -16%, 1995-2006; Cadman et al., 2007). Conversely, in the Lake Simcoe-Rideau region (Ontario), there were no significant changes in the probability of observation (Cadman et al., 2007).

3.3 Needs of the Least Bittern

Current understanding of the ecological needs of the Least Bittern may be biased because selection of study sites and associated findings may be influenced by how easily the sites can be accessed and surveyed. Furthermore, the species' apparent habitat needs might be distorted by limitations in what habitat is available now compared to historically.

3.3.1 Habitat and biological needs

Breeding period

In Canada, breeding habitats are occupied from early May to early September (Fragnier, 1995). They consist of freshwater and brackish marshes with dense, tall, robust emergent plants (mainly cattail Typha spp), interspersed with relatively shallow (10-50 cm) open water and occasional clumps of shrubby vegetation (Parsons, 2002; Hay, 2006; Budd, 2007; Jobin et al., 2007; Yocum, 2007; Griffin et al., 2009). Rehm and Baldassarre (2007) refer to these conditions as hemi-marsh.

Water levels approximating those of a natural regime are an important breeding habitat feature as high water levels can flood nests that are constructed just above the water, whereas low levels reduce food availability and facilitate predators' access to nests (Arnold, 2005).

Densities of Least Bitterns appear to be mostly affected by local conditions such as water depth, food abundance, vegetation type and cover availability rather than marsh area or marsh area within the surrounding landscape (Arnold, 2005; Tozer et al. 2010). Indeed, although Least Bitterns usually nest in larger marshes (> 5 ha), territorial individuals have been found in marshes as small as 0.4 ha (Gibbs and Melvin, 1990). The species can also be semi-colonial, particularly in highly productive habitats (Kushlan, 1973; Bogner, 2001; Meyer and Friis, 2008), where they can reach a density of up to five calling birds or nests per hectare (Arnold, 2005; Poole et al., 2009). Although typically territorial, no definitive information exists on territory size and home range for the Least Bittern. Bogner and Baldassarre (2002a) found that breeding individuals moved an average maximum distance of 393 m ± 36 SE between two points while Griffin et al. (2009) found an average maximum distance of more than 2,000 m for breeding individuals in Missouri.

The Least Bittern is a visual predator that forages for prey (e.g., small fish, tadpoles, molluscs, insects) in clear, shallow water near openings in the marsh vegetation, often from platforms it constructs by bending emergent vegetation (Poole et al., 2009). This foraging method probably explains why they prefer marshes interlaced with channels, such as those created by muskrats (Poole et al., 2009).

Non-breeding period

There is little information on ecological needs of Least Bitterns and habitat characteristics in moulting, post-breeding dispersal, migration and wintering sites, although it is presumed that they are similar to those of breeding habitats.

4. Threats

4.1 Threat assessment

Table 3. Threat assessment.

Habitat loss or degradation.

| Threat | Level of concern a | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wetland destruction and degradation | High | Widespread | Current | Recurrent | High | High |

| Impaired water quality | Medium-High | Widespread | Current | Continuous/ Recurrentd | Moderate | Medium |

| Regulated water levels | Medium | Local | Current/ Unknown | Recurrent/ Unknown | High/ Low | Medium |

Exotic, invasive or introduced species or genome.

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invasive species | Medium | Local | Current | Continuous | High/ Moderate | Medium |

Accidental mortality.

| Threat | Level of concern a | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collisions with cars and man-made structures | Low | Local | Current | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

Disturbance or harm.

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recreational activities | Low | Local | Current | Recurrent | Moderate | Medium |

Climate and natural disasters.

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate change | Low | Widespread | Anticipated | Unknown | Moderate/ Unknown | Medium/ Low |

Natural processes or activities.

| Threat | Level of concerna | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severityb | Causal certaintyc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diseases | Low | Widespread | Current | Unknown | High/ Low | Low |

aLevel of Concern: signifies that managing the threat is of (high, medium or low) concern for the recovery of the species, consistent with the population and distribution objectives. This criterion considers the assessment of all the information in the table.

bSeverity: reflects the population-level effect (High: very large population-level effect, Moderate, Low, Unknown).

cCausal certainty: reflects the degree of evidence that is known for the threat (High: available evidence strongly links the threat to stresses on population viability; Medium: there is a correlation between the threat and population viability e.g. expert opinion; Low: the threat is assumed or plausible).

dEach threat is evaluated at the local level (each site) and at the rangewide level. When two items are present in a box, this means that the threat level is not the same for both scales (Local scale / Rangewide scale).

4.2 Description of threats

Threats are listed in order of decreasing level of concern. However, apart from wetland destruction and degradation and impaired water quality, the level of concern is speculative because the prevalence and impact of threats are poorly documented in Canada. Some threats that occur on wintering grounds and along migration routes may have consequences on Least Bitterns that migrate to Canada for breeding. The absence of muskrats (who open corridors in the marsh vegetation) and the reduction of natural disturbances (e.g., fires that prevent shrubs from invading the habitat) are also limiting factors for the species.

Wetland destruction and degradation

Loss of wetland habitat as a result of human activities is thought to have severely reduced Least Bittern numbers across North America. The rate of large-scale wetland loss in southern Canada appears to have slowed in recent years, but wetlands continue to be drained for housing development and/or conversion to agricultural uses (Ducks Unlimited Canada, 2010). In Quebec, 80% of wetlands along the St. Lawrence River have been lost since European settlement (James, 1999; Painchaud and Villeneuve, 2003). Development up to the edge of marshes as well as fragmentation facilitates access to deeper portions of marshes by some mammalian predators

Impaired water quality

Run-off, siltation, acid rain and eutrophication can reduce prey abundance (Weller, 1999) and increase the likelihood of disease and toxicity. Any reduction in water clarity will also likely reduce the foraging success of a visual feeder such as the Least Bittern.

Single source pollution events such as toxic spills are particularly likely in marshes that border the busy shipping lanes of the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes (Chapdelaine and Rail, 2004). The effects of such events on Least Bitterns have not been investigated but could be important since the species is known to bio-accumulate toxins in its eggs and feathers (Causey and Graves, 1969).

Regulated water levels

Since water-level management along the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario was established in the 1950s, the average maximum flow has decreased in summer and the average minimum flow has increased in winter (Morin and Leclerc, 1998). However, deviations from the regulation plan occur regularly and can impact the Least Bittern during crucial periods of reproduction (DesGranges et al., 2006). This situation may also be taking place in other important waterways such as the Ottawa River and even inland. Although Least Bitterns mostly occupy sites where water levels are stable during the breeding season, any dramatic change in water levels during this period is liable to affect the species negatively.

Prolonged periods of high water levels can reduce the extent of cattail marshes, both directly through flooding and indirectly by making conditions more favorable for other species such as Wild Rice (Zizania palustris) that are less suitable for nesting Least Bitterns (Sandilands and Campbell, 1988; Timmermans et al., 2008). Conversely, prolonged periods of relatively stable water levels may increase the density of cattail stands and eliminate open pools required by the species. Jobin et al. (2009) showed that the abundance of a Least Bittern population was reduced rapidly following a pronounced decrease of water depth due to a breach in an impounded wetland during the reproductive season followed by a rapid increase in abundance the following year when water depth returned to previous levels.

Invasive species

Several species of invasive plants and animals are increasing in range and abundance in North American marshes, largely due to human interventions. Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), Reed Canary Grass (Phalaris arundinacea), European Common Reed (Phragmites autralis spp. australis), Flowering Rush (Butomus umbellatus) as well as a hybrid cattail (Typha x glauca) in the Great Lakes region are crowding out native emergent plants (Lavoie et al., 2003; Hudon, 2004; Jobin, 2006; Jobin et al., 2007; Latendresse and Jobin, 2007; Wilcox et al., 2007). While the Least Bittern can breed in a variety of emergent plants, including stands of invasive species, they preferentially breed in cattails (Poole et al., 2009). Floating invasive plants (e.g., European Frog-bit [Hydrocharis morsus-ranae] and Water Chestnut [Trapa natans]), can also alter habitat structure namely by accelerating marsh succession to drier conditions that are suboptimal for feeding and breeding (Blossey et al., 2001).

Populations of invasive animals such as Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) are increasing in wetlands occupied by the Least Bittern, especially in southern Ontario and Quebec. In addition to their deleterious effects on ecosystem function, they may impact the Least Bittern more directly when stirring up sediments as they forage thereby reducing water clarity (Wires et al., 2010).

Collisions with cars and man-made structures

Least Bitterns fly at low levels and migrate at night, two characteristics which make them susceptible to collisions with vehicles, buildings, guy wires, power lines, barbed wire fences, and towers. These collisions may be frequent enough at some sites to threaten local populations (Poole et al., 2009). In one case, 12 Least Bitterns were killed in collisions with vehicles and four died after being impaled on a fence during one weekend on a road that passes through a refuge in Louisiana (Guillory, 1973). Least Bitterns have also been found dead along the Long Point (Ontario) causeway on a few occasions (Ashley and Robinson, 1996; J. McCracken personal communication). These incidents suggest that roads or structures built adjacent to suitable wetlands can cause mortality for birds moving between habitat patches or during migration.

Recreational activities

Although the Least Bittern can tolerate a certain level of human activity near wetlands used for breeding, including the occasional passage of small boats near their foraging areas (Poole et al., 2009), they seem to prefer nesting outside high density urban areas (Smith-Cartwright and Chow-Fraser, unpublished results). However, infrequent and unpredictable disturbance may be as disruptive to the Least Bittern as it is for other species that are intolerant of human activity (Nisbet, 2000). Frequent use of call broadcasts by recreational birders in wetlands where birding pressure is intense may also be disruptive to breeding Least Bitterns although the importance of this threat has not been evaluated. Finally, direct impacts such as waves from motorized watercrafts can erode wetland edges and possibly flood or upset nests.

Climate change

Climate change has the potential of having unpredictable, widespread and severe effects on the Least Bittern and its habitat. Climate change could increase the frequency of events such as floods and storms that can destroy nests and habitat, and may also change the overall hydrological and temperature regimes that account for the Least Bitterns' distribution in Canada. For example, the reduction of water levels caused by elevated temperatures will likely reduce the area of wetlands, and lead to reduced prey abundance (Mortsch et al., 2007; Wires et al., 2010). Alternatively, a potential northward expansion by the species could favor the use of numerous wetlands in the boreal forest although the quality of these habitats for breeding purposes would have to be assessed.

Diseases

The impact of various diseases and parasitism have been poorly studied in Least Bittern populations. Presumably, individuals are susceptible to diseases known to affect other wading birds (Friend and Franson, 1999; Wires et al., 2010). The Least Bittern is also one of 326 bird species in which West Nile Virus has been found (Center for Disease Control, 2009).

5. Population and distribution objectives

The population and distribution objectives for the Least Bittern are to maintain and, where possible, increase the current population size and area of occupancy in Canada. These objectives are considered possible in many parts of the range where adequate, yet currently unoccupied, breeding, foraging, post-breeding dispersal, moulting and migration stopover habitat is available or could be restored. Part of these objectives can only be achieved over the long term (>10 years).

The species' historical abundance and distribution are not well known, and specific habitat needs for different life stages and locations across its Canadian range are not understood well enough at present to set quantitative objectives. This may become possible in subsequent iterations of this recovery strategy as knowledge gaps are filled.

6. Broad strategies and general approaches to meet objectives

6.1 Actions already completed or underway

The following activities have been undertaken or completed in Canada since 2000:

- Literature reviews of all available information on the Least Bittern (McConnell, 2004; Gray Owl Environmental Inc., 2009);

- National Least Bittern survey protocol for the breeding season (Jobin et al., 2011 a,b);

- National protocol for capturing, banding, radio-tagging and tissue sampling Least Bitterns in Canada (MacKenzie and McCracken, 2011);

- Surveys of potential and historical sites have been conducted in southern Manitoba (2003-2008; R. Bazin pers. comm.; Hay, 2006), in Ontario (2001-2012; Bowles, 2002; Desy, 2007; Meyer and Friis, 2008) and in Quebec (2004-2013; Jobin, 2006; Jobin et al., 2007; Latendresse and Jobin, 2007; Jobin and Giguère, 2009);

- Directed surveys in National Wildlife Areas in Ontario and Quebec;

- Masters and PhD theses completed on Least Bittern breeding habitat in Ontario (N. Bartok - University of Western Ontario; P. Quesnelle - Carleton University; D. Tozer – Trent University) and Manitoba (S. Hay - University of Manitoba);

- On-going monitoring programs: Great Lakes Coastal Wetland Monitoring Program (Canadian Wildlife Service-Ontario Region; Meyer et al., 2006); Marsh Monitoring Program in Ontario since 1994 and in Quebec since 2004; Monitoring of Least Bittern presence in several wetlands in southern Quebec as part of the avian species at risk annual breeding sites monitoring (SOS-POP); Prairies and Parkland pilot Marsh Monitoring Program since 2008;

- Creation of the Samuel-de-Champlain biodiversity reserve (Natural heritage conservation Act of Quebec; R.S.Q. c. C-61.01) which will preserve 487 ha of wetlands on the shores of the Richelieu River near the Quebec/USA border. This will include two of the Least Bittern critical habitat units (Baie McGillivray and Rivière Richelieu-Frontière);

- Broad efforts to protect, manage, and restore wetlands in Ontario are ongoing, for example, through the Eastern Habitat Joint Venture of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan and the Great Lakes Sustainability Fund;

- The Walpole Island First Nation is developing an ecosystem protection plan based on the community’s traditional ecological knowledge.

6.2 Strategic direction for recovery

Table 4. Recovery planning for the Least Bittern.

| Threats or limiting factor | Broad strategy to recovery | Priority | General description of research and management approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Stewardship and management of the species and its suitable habitat | High |

|

| Knowledge gaps | Surveys and monitoring | High |

|

| Wetland destruction; Impaired water quality; Regulated water levels; Knowledge gaps | Research | High |

|

| All | Communication and Partnerships | Medium |

|

7. Critical habitat

7.1 Identification of the species' critical habitat

Critical habitat is partially identified for the Least Bittern in this recovery strategy. As there is limited information concerning most foraging, moulting, post-breeding dispersal and migration stopover habitats, critical habitat is only identified for the breeding habitat. A schedule of studies (section 7.2) is proposed to complete the identification of critical habitat.

The identification of critical habitat is based on two aspects: habitat suitability and habitat occupancy.

7.1.1 Habitat suitability

Habitat suitability refers to the attributes of habitats in which individuals may carry out breeding activities (e.g., courtship, territory defense, nesting). The biophysical attributes of suitable Least Bittern breeding habitat include:

- permanent wetlands

footnote ii (marshes and shrubby swamps within the boundaries of the high-water mark), And - tall and robust emergent herbaceous and/or woody vegetation interspersed with areas of open water (hemi-marsh conditions), And

- Water level fluctuations close to those of a natural regime

Based on knowledge related to the average maximum movements during the breeding season (~400 m according to Bogner and Baldassarre, 2002b; 2,000 m according to Griffin et al., 2009), the suitable habitat within a 500 m radius was selected as representative of the area used by a Least Bittern individual or pair.

7.1.2 Habitat occupancy

Habitat occupancy relates to areas of suitable habitat that have documented use for breeding purposes in one or multiple years. Confirmed breeding records (see Appendix A for definitions) constitute the highest indication of habitat occupancy and therefore of the presence of suitable habitat. However, since confirming breeding is difficult for this secretive species (Tozer et al., 2007), records of multiple probable breeders in a single year or probable breeders in multiple years can also be used as indicators of habitat suitability, in particular as a demonstration of fidelity to specific wetlands. The remaining records of breeding activities (e.g., possible breeders) were not considered as sufficient indicators of the suitability of the habitat for reproduction since the Least Bittern may use some wetlands sporadically (e.g., for movements) or for non-reproductive purposes.

Given that wetland habitats are dynamic throughout the Canadian range, recent information may be more reliable for evaluating suitable habitat and Least Bittern occupancy. In light of this, the selection of records dating back a maximum of 10 years from when the recovery strategy was being prepared (i.e. starting in 2001) has been identified as appropriate. Furthermore, 2001 was the first year of data collection for the second Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas, which enabled confirmation of the continued use of individual wetlands (fidelity) at the heart of the species' range in Canada. Records older than 2001 will need to be validated to determine the continued presence of suitable habitat and current occupancy by the Least Bittern (see section 7.2).

7.1.3 Critical habitat identification for the Least Bittern

Critical habitat is identified in this recovery strategy as the suitable habitat within 500 m of coordinates corresponding to the following minimum breeding activity:

- one record of confirmed breeding since 2001; Or

- two records of probable breeding in any single year since 2001; Or

- one record of probable breeding in each of two separate years within a 5-year floating window

footnote iii since 2001

Depending on its area, structure and the nature of observed reproductive activities, a wetland can be identified as a single critical habitat unit or can include multiple units. Overlapping units are merged together to form a single larger unit.

Using these criteria, 115 critical habitat units containing up to 17 102 ha of Least Bittern critical habitat have been identified (see Appendix B), including 10 in Manitoba (1,856 ha), 54 in Ontario (10,740 ha), 48 in Quebec (4,615 ha) and 3 in New Brunswick (137 ha). Within a critical habitat unit, any man-made structure (e.g., roads, wharves, powerline poles) or areas (e.g., ploughed agricultural land, deep open water) that do not possess the biophysical attributes of suitable habitat are not identified as critical habitat.

7.1.4 Non-critical habitats

The Least Bittern may occasionally nest in non-traditional habitats (e.g., roadside ditches, sewage lagoons) that are anthropogenic in nature and not managed for conservation purposes. These habitats do not provide sustained, high quality breeding conditions given that they may be the object of frequent interventions that could negatively affect breeding individuals. Consequently, they are not identified as critical habitat under SARA, even if breeding is confirmed. However, the general prohibitions under SARA and the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 (S.C., 1994, c. 22) protecting the birds and their residences (nests) from damage or destruction remain in effect.

7.2 Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

Table 5. Schedule of studies.

| Description of activity | Rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

Conduct surveys in wetlands where:

|

Additional critical habitat units identified, particularly in more remote areas | 2014-2019 |

| Characterize foraging, post-breeding dispersal, moulting and migration stopover habitats in Canada and survey Least Bitterns within them in the appropriate periods of the year | Additional critical habitat units identified; Needed to conserve the species in throughout its life cycle in Canada | 2014-2019 |

aThe 1991 year has been selected based on the fact that Conservation Data Centres consider records older than 20 years to be historical.

7.3 Activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat was degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species (Government of Canada, 2009). Destruction may result from a single activity or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time. Examples of activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat for the Least Bittern are shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Examples of activities likely to destroy Least Bittern critical habitat.

| Description of the activity a | Description of the effect (biophysical attributes or other) | Scale of activity likely to destroy critical habitat b Site | Scale of activity likely to destroy critical habitatbArea | Scale of activity likely to destroy critical habitatbLandscape | Timing considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infilling, excavation or draining of wetlands (e.g., infrastructure development and construction, superficial mineral extraction; underground mineral/hydrocarbon extraction, dredging and channelization) |

|

X | X | - | Applicable at all times |

| Activities that generate soil run-off and increased water turbidity or nutrient influx (e.g., cultivating the land next to a wetland without proper vegetation buffers) |

|

X | X | - | Applicable at all times |

| Introduction of invasive vegetation, fish and invertebrate species |

|

X | - | - | Applicable at all times |

| Repeated use of vehicles and motor boats within or close to wetlands |

|

X | - | - | Applicable at all times in relation to erosion ; Applicable during the breeding period in relation to the flooding of nest component |

| Prescribed burns or other means of natural vegetation removal within wetland habitats |

|

X | - | - | Can be conducted when individuals have left the habitat (after the fall migration) |

| Deposition of deleterious substances (including snow), either directly (in water) or indirectly (upstream, soil) |

|

X | X | - | Applicable at all times |

| Construction of infrastructures (e.g., roads, houses, boat ramps) which increase the access to critical habitat |

|

X | X | - | Applicable at all times |

| Presence of livestock that removes or tramples the vegetation |

|

X | - | - | Applicable at all times |

aActivities required to manage, inspect and maintain existing infrastructures that are not critical habitat but whose footprints may be within or adjacent to critical habitat units are not examples of activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat provided that they are carried out in a manner consistent with Least Bittern critical habitat conservation. Furthermore, management of wetlands for wildlife conservation purposes does not typically result in destruction of critical habitat if activities take place when the individuals are not present in the habitat (after migration). For additional information, communicate with Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service at : enviroinfo@ec.gc.ca.

bSite: anticipated effect close to 1 x 1 km; Area: 10 x 10 km; Landscape: 100 x 100 km.

8. Measuring progress

The performance indicators presented below provide a way to define and measure progress toward achieving the population and distribution objectives.

- the population size of Least Bittern is maintained and, where possible, increased;

- the area of occupancy is maintained and, where possible, increased.

9. Statement on action plans

One or more action plans associated with the recovery strategy will be elaborated in the coming years. They will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by 2019.

10. References

Archer, R.W. and K.E. Jones. 2009. The Marsh Monitoring Program Annual Report, 1995-2007. Annual indicies and trends in bird abundance and amphibian occurrence in the Great Lakes basin. Report for Environment Canada by Bird Studies Canada, Port Rowan, ON.

Arnold, K.E. 2005. The Breeding Ecology of Least Bitterns (Ixobrychus exilis) at Agassiz and Mingo National Wildlife Refuges. MSc thesis, South Dakota State University, Brookings, South Dakota.

Ashley, E.P. and J.T. Robinson. 1996. Road mortality of amphibians, reptiles and other wildlife on the Long Point causeway, Lake Erie, Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 110: 403-412.

Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs du Quebec. 2012. Données préliminaires gracieusement fournies par le Regroupement QuebecOiseaux, le Service canadien de la faune d'Environnement Canada et Études d'Oiseaux Canada. Quebec, Quebec.

Austen, M.J.W., M.D. Cadman, and R.D. James. 1994. Ontario Birds at Risk: Status and Conservation Needs. Federation of Ontario Naturalists and Long Point Bird Observatory, Toronto and Port Rowan, Ontario.

BirdLife International 2009. Ixobrychus exilis. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.2. (accessed on 8 December 2009).

Bird Studies Canada. 2009. BirdMap Canada. A source of information on bird distribution and movements. [accessed December 2009].

Bird Studies Canada. 2010. Maritimes Breeding Bird Atlas. [accessed July 2010].

Blossey, B., L.C. Skinner, and J. Taylor. 2001. Impact and management of purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) in North America. Biodiversity and Conservation 10: 1787-1807.

Bogner, H.E. 2001. Breeding biology of Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) in western New York. MSc thesis, State University of New York, Syracuse.

Bogner, H.E., and G.A. Baldassarre. 2002a. The effectiveness of call-response surveys for detecting least bitterns. Journal of Wildlife Management 66: 976-984.

Bogner, H. E., and G.A. Baldassarre. 2002b. Home range, movement and nesting of Least Bitterns in western New York. Wilson Bulletin 114: 297-308.

Bowles, R. 2002. Least Bittern surveys in Simcoe County, Ontario. Unpublished manuscript, Canadian Wildlife Service.

Budd, M.J. 2007. Status, distribution, and habitat selection of secretive marsh birds in the delta of Arkansas. M.Sc. thesis, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, Arkansas, USA.

Cadman, M.D., D.A. Sutherland, G.G. Beck, D. Lepage, and A.R. Couturier (eds.). 2007. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Ontario, 2001-2005. Bird Studies Canada, Environment Canada, Ontario Field Ornithologists, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and Ontario Nature, Toronto, xxii + 706 pp.

Causey, M.K., and J.B. Graves. 1969. Insecticide residues in Least Bittern eggs. Wilson Bulletin 81:340-341.

Center for Disease Control. 2009. Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases. West Nile Virus. (accessed: 10 December 2009).

Chapdelaine, G., and J.-F. Rail. 2004. Quebec’s Waterbird Conservation Plan. Migratory Bird Division, Canadian Wildlife Service, Quebec Region, Environment Canada, Sainte-Foy, Quebec. 99 pp.

Conway, C.J. 2009. Standardized North American Marsh Bird Monitoring Protocols. Wildlife Research Report #2008-1. U.S. Geological Survey, Arizona Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Tucson, AZ. 57 pp.

COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 36 pp.

Dahl, T.E. 2006. Status and trends of wetlands in the conterminous United States 1998 to 2004. U.S. Department of the Interior; Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C. 112 pp.

Delany, S., and D. Scott. 2006. Waterbird population estimates. Fourth Edition. Wetlands international, Wageningen, 239 pp.

DesGranges, J.-L., J. Ingram, B. Drolet, J. Morin, C. Savage, and D. Borcard. 2006. Modelling wetland bird response to water level changes in the Lake Ontario-St. Lawrence River hydrosystem. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 113: 329-365.

Desy, G.E. 2007. Summary report for Least Bittern surveys conducted at Long Point and Big Creek National Wildlife Areas, Ontario. Submitted to Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario Region.

Ducks Unlimited Canada. 2010. Southern Ontario Wetland Conversion Analysis. Final Report. Ducks Unlimited Canada-Ontario Office, Barrie, Ontario.

Environment Canada. 2007. Least Bittern Species Profile. Species at Risk Public registry website.

Friend, M., and J. C. Franson. Eds. 1999. Field Manual of Wildlife Diseases: U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resource Division, National Wildlife Health Center, Madison, Wisconsin.

Gibbs, J.P., and S.M. Melvin. 1990. An assessment of wading birds and other wetland avifauna and their habitat in Maine. Final Report, Maine Deptartment of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, Bangor, ME.

Government of Canada. 2009. Species at Risk Act Policies, Overarching Framework [Draft]. Species at Risk Act Policy and Guideline Series. Environment Canada. Ottawa. 38 pp.

Gray Owl Environmental Inc. 2009. Least Bittern literature review and a preliminary survey protocol. Prepared for the Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region. 95 pp.

Griffin, A. D., F. E. Durbian, D. A. Easterla and R. L. Bell. 2009. Spatial ecology of breeding Least Bitterns in northwest Missouri. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 121: 521-527.

Guillory, H.D. 1973. Motor vehicles and barbed wire fences as major mortality factors for the Least Bittern in southwestern Louisiana. Inland Bird Banding News 45: 176-177.

Hay, S. 2006. Distribution and Habitat of the Least Bittern and Other Marsh Bird Species in Southern Manitoba. Masters of Natural Resource Management thesis, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Hudon, C. 2004. Shift in wetland plant composition and biomass following low-level episodes in the St. Lawrence River: Looking into the future. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 61: 603-17.

James, R.D. 1999. Update status report on the Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 12 pp.

Jobin, B. 2006. Inventaire du Petit Blongios dans le parc national de Plaisance, été 2005. Série de rapports techniques No. 457, Service canadien de la faune, région du Quebec, Environnement Canada, Sainte-Foy, 40 pp. et annexes.

Jobin, B., and J. Picman. 1997. Factors affecting predation on artificial nests in marshes. Journal of Wildlife Management 61: 792-800.

Jobin, B., and S. Giguère. 2009. Inventaire du Petit Blongios et de la Tortue des bois à la garnison Farnham du ministère de la Défense nationale, été 2008. Environnement Canada, Service canadien de la faune, région du Quebec. Rapport non publié. 34 p. et annexes.

Jobin, B., C. Latendresse et L. Robillard. 2007. Habitats et inventaires du Petit Blongios sur les terres du ministère de la Défense nationale à Nicolet, Quebec, étés 2004, 2005 et 2006. Série de rapports techniques no 482, Service canadien de la faune, région du Quebec, Environnement Canada, Sainte-Foy, Quebec, 85 pp. et annexes.

Jobin, B., L. Robillard and C. Latendresse. 2009. Response of a Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) population to interannual water level fluctuations. Waterbirds 32: 73-80.

Jobin, B., M.J. Mazerolle, N.D. Bartok and Bazin, R. 2013. Least Bittern occupancy dynamics and detectability in Manitoba, Ontario and Québec. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 125: 62-69.

Jobin, B., R. Bazin, L. Maynard, A. McConnell and J. Stewart. 2011a. National Least Bittern Survey Protocol. Technical Report Series No. 519, Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service, Quebec Region, Quebec. 26 pp.

Jobin, B., R. Bazin, L. Maynard, A. McConnell and J. Stewart. 2011b. Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) survey protocol. Waterbirds 34: 225-233.

Johnson, D.J., J.P. Gibbs, M. Herzog, S. Lor, N.D. Niemuth, C.A. Ribic, M. Seamans, T.L. Schaffer, G. Shriver, S. Stehman, and W.L. Thompson. 2009. A sampling design framework for monitoring secretive marshbirds. Waterbirds 32: 203-215.

Kushlan, J. A. 1973. Least Bittern nesting colonially. Auk 90: 685-686.

Kushlan, J.A., and J.A. Hancock. 2005. Herons. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Latendresse, C., and B. Jobin. 2007. Inventaire du Petit Blongios à la baie McLaurin et au marais aux Massettes, région de l'Outaouais, été 2006. Environnement Canada, Service canadien de la faune, région du Quebec, Sainte-Foy. Rapport inédit. 40 p. et annexes.

Lavoie, C., M. Jean, F. Delisle, and G. Létourneau. 2003. Exotic plant species of the St.Lawrence River wetlands: a spatial and historical analysis. Journal of Biogeography 30: 537-49.

Mackenzie, S.A., and J.D. McCracken. 2011. National protocol for capturing, banding, radio-tagging and tissue sampling Least Bitterns in Canada. Prepared for Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service and the National Least Bittern Recovery Team. Bird Studies Canada, 30 pp.

McConnell, A. 2004. Draft Least Bittern Background Report, Version 1.0. Prepared for the Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Ontario Region.

McKercher, R.B., and B. Wolf. 1986. Understanding Western Canada’s Dominion Land Survey System. Saskatoon: Division of Extension and Community Relations, University of Saskatchewan.

Meyer, S.W. and C.A. Friis. 2008. Occurrence and habitat of breeding Least Bitterns at St. Clair National Wildlife Area. Ontario Birds 26: 146-164.

Meyer, S.W., J.W. Ingram, and G.P. Grabas. 2006. The Marsh Monitoring Program: Evaluating marsh bird survey protocol modifications to assess Lake Ontario coastal wetlands at a site-level. Technical Report Series 465. Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario region, Ontario.

Morin, J. and M. Leclerc. 1998. From pristine to present state: hydrology evolution of Lake Saint-Francois, St. Lawrence River. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 25: 864–879.

Mortsch, L., J. Ingram, A. Hebb, and S. Doka (eds). 2007. Great Lakes Coastal Wetland Communities: Vulnerability to Climate Change and Response to Adaptation Strategies. Final Report.

Nankinov, D.M. 1999. On the question of distribution and migrations of the Little Bittern. Berkut 8:15-20.

NatureServe. 2010. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. (accessed January 26th 2011).

Nisbet, I.C.T. 2000. Disturbance, habituation, and management of waterbird colonies. Waterbirds 23: 312-332.

Painchaud, J., et Villeneuve, S. 2003. Portrait global de l'état du Saint-Laurent-Suivi de l'état du Saint-Laurent. Plan d'action Saint-Laurent Vision 2000. Bibliothèque Nationale du Canada. 18 pp.

Parsons, K.C. 2002. Integrated management of waterbird habitats at impounded wetlands in Delaware Bay, U.S.A. Waterbirds 25: 25-41.

Poole, A.F., P. Lowther, J. P. Gibbs, F. A. Reid and S. M. Melvin. 2009. Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis). The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (accessed March 30th 2011)

Post, W., and C.A. Seals. 2000. Breeding biology of the common moorhen in an impounded cattail marsh. Journal of Field Ornithology 71(3):437-442.

Province of New Brunswick. 2002. New Brunswick Atlas, Second Edition Revised. Nimbus Publishing and Service New Brunswick.

Rehm, E.M. and G.A. Baldassarre. 2007. The influence of interspersion on marsh bird abundance in New York. Wilson Journal of Ornithology 119: 648-654.

Sandilands, A.P., and C.A. Campbell. 1988. Status report on the Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario. 34 pp.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. The Sibley Guide to Birds. Knopf, New York.

Smith-Cartwright, L., et L. Chow-Fraser. Landscape-scale influences on Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis) habitat use in southern Ontario coastal marshes. Unpublished results.

Timmermans, S.T.A., S.S. Badzinski, and J.W. Ingram. 2008. Associations between breeding marsh bird abundances and Great Lakes hydrology. Journal of Great Lakes Research 34:351-364.

Tori, G.M., S. McLoed, K. McKnight, T. Moorman, and F.A. Reid. 2002. Wetland conservation and Ducks Unlimited: Real world approaches to multispecies management. Waterbirds 25: 115-121.

Tozer, D.C., E. Nol, and K.F. Abraham. 2010. Effects of local and landscape-scale habitat variables on abundance and reproductive success of wetland birds. Wetlands Ecology and Management 18: 679–693.

USFWS. 2002. Birds of conservation concern 2002. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Division of Migratory bird Management. Arlington, Virginia.

Weller, M.W. 1999. Wetland Birds: Habitat Resources and Conservation Implications. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 316 pp.

Wilcox, D.A, Thompson, T.A., Booth, R.K., and Nicholas, J.R., 2007, Lake-level variability and water availability in the Great Lakes: U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1311, 25 pp.

Wires, L.R., S.J. Lewis, G.J. Soulliere, S.W. Matteson, D.V. Weseloh, R.P. Russell, and F.J. Cuthbert. 2010. Upper Mississippi Valley / Great Lakes Waterbird Conservation Plan. A plan associated with the Waterbird Conservation for the Americas Initiative. Final Report submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, MN.

Yocum, B.J. 2007. Breeding biology of and nest site selection by Least Bitterns (Ixobrychus exilis) near Saginaw Bay, Michigan. M.Sc. thesis, Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Michigan, USA.

Appendix A: Standard Breeding Bird Atlas codes

| Breeding designation | Atlas codea and description |

|---|---|

| Probable breeding | P: Pair observed in their breeding season in suitable nesting habitat T: Permanent territory presumed through registration of territorial behaviour (song, etc.), or the occurrence of an adult bird, on at least two days, a week or more apart, at the same place, in suitable nesting habitat during the breeding season D: Courtship or display between a male and a female or two males including courtship, feeding or copulation V: Visiting probable nest site A: Agitated behaviour or anxiety calls of an adult indicating nest-site or young in the vicinity B: Brood patch on adult female or cloacal protuberance on adult male |

| Confirmed breeding | NB: Nest building or carrying nest materials DD: Distraction display or injury feigning NU: Used nest or egg shells found (occupied or laid within the period of the survey). Use only for unique and unmistakable nests or shells FY: Recently fledged young or downy young AE: Adults leaving or entering nest sites in circumstances indicating occupied nest (including nests which content cannot be seen) FS: Adult carrying fecal sac CF: Adult carrying food for young during its breeding season NE: Nest containing eggs NY: Nest containing young seen or heard |

aAtlas codes and descriptions can vary slightly from one province to another but convey similar meanings. Atlas codes for possible breeding are not presented here.

Appendix B: Critical habitat for the Least Bittern in Canada

Table B-1. Description of the 10 x 10 km Standardized UTM Grid, Quarter Sections and Critical Habitat Units for the Least Bittern in Manitoba.

| Name of the critical habitat unit | 10 x 10 km UTM grid ID a | UTM grid coordinates b Easting | UTM grid coordinatesbNorthing | Quarter sectionsccontaining critical habitat | Quarter sectionsc containing critical habitat | Critical habitat unit area (ha)d | Description | Land tenuree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brokenhead Swamp | 14PA82 | 680000 | 5520000 | NE-12-10-08-E1 NW-07-10-09-E1 NW-18-10-09-E1 |

SW-18-10-09-E1 SE-13-10-08-E1 NE-13-10-08-E1 |