Slate Islands Provincial Park Management Plan (2018)

This document provides policy direction for the protection, development and management of Slate Islands Provincial Park and its resources.

Approval statement

May 22, 2018

I am pleased to approve the Slate Islands Provincial Park Management Plan as the official policy for the management and development of this park. The plan reflects the intent of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Ontario Parks to protect the natural values and cultural heritage resources of Slate Islands Provincial Park, and to maintain and develop opportunities for high quality ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation experiences and heritage appreciation for the residents of Ontario and visitors to the province.

This document outlines the site objectives, policies, actions and implementation priorities, related to the park's natural, cultural and recreational values, and summarizes the involvement of Indigenous communities, the public and stakeholders that occurred as part of the planning process.

The plan for Slate Islands Provincial Park will be used to guide the management of the park over the next 20 years. During that time, the management plan may be examined to address changing issues or conditions, and may be adjusted as the need arises.

I wish to extend my sincere thanks to all those who participated in the planning process.

Yours truly,

Bruce Bateman

Director, Ontario Parks

1. Introduction

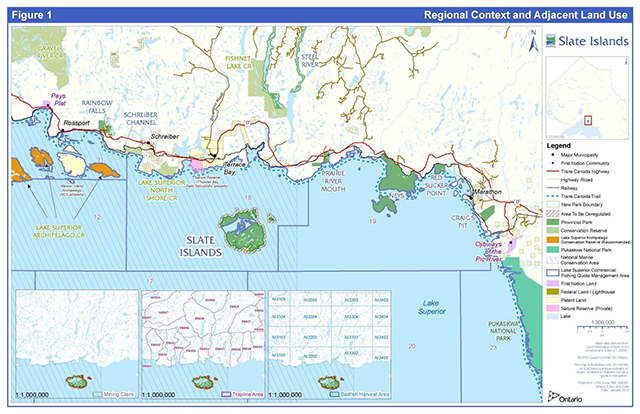

Slate Islands Provincial Park is a 6,570 hectare natural environment class park located in northern Lake Superior, thirteen kilometres southeast of Terrace Bay (Figure 1).

The park protects 15 islands in the Slate Islands Archipelago, which are spread over two groups: the major group consisting of Patterson, Mortimer, McColl, Edmonds, Bowes, Delaute and Dupuis islands; and the smaller Leadman Island group (which includes Leadman, Cape, Spar and Fish Island).

While the islands are inhabited by diverse plant and animal communities, their distance from the mainland and their exposure to the harsh Lake Superior climate have resulted in the development of a relatively unique terrestrial ecosystem. Some of the distinctive life science attributes of the Slates include their status as one of the most important island habitats for arctic-alpine plants in Lake Superior (M. Oldham, pers. comm. 2002 – cited in Shuter et al. 2005) and the presence of a simplified mammal community dominated by herbivores. The park’s most notable natural feature is the existence of a relatively isolated population of forest-dwelling woodland caribou (Carr et al. 2012). The Slate Islands are also recognized for their unique earth science features.

Access to the park is solely by water or air. Public boat launches and charter services are available in Terrace Bay, Rossport and Marathon. The Slate Islands are a recreation destination for boaters and lake trout anglers from local communities such as Terrace Bay, and from regional communities such as Thunder Bay. The park is also a longstanding destination for powerboaters and sailors from Duluth, Minnesota, and Bayfield, Wisconsin. The Slate Islands are becoming increasingly popular as a destination for sea kayakers from Canada, the United States and overseas.

2. Planning context

The Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act (PPCRA) states that management direction must be prepared for each provincial park in Ontario. The initial Slate Islands Provincial Park Management Plan was approved in 1991. The approved plan provided an expression of how the government intended to develop and manage the park over a 20 year time period. The plan was examined in 2007 and it was determined that replacement of the management plan was required in order to address the protection of caribou and management of emerging recreational activities such as sea kayaking, within the context of the heightened profile of the Slates as a destination.

This plan identifies the purpose and vision, objectives and zoning for the park, as well as providing park management policies and implementation priorities. This management plan is written with a 20 year perspective and was developed by a planning team that included representation from the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF)/Ontario Parks, as well as the Township of Terrace Bay, Pays Plat First Nation and Parks Canada (Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area). The planning team began meeting in the autumn of 2011 and continued to meet until 2015 to discuss planning topics and to review drafts of consultation documents. The planning team also visited the Slate Islands in 2012 and Isle Royale National Park in 2013. The planning team also hosted open houses in Terrace Bay and Thunder Bay in December 2013.

The PPCRA has two principles that guide all aspects of planning and management of Ontario’s system of provincial parks and conservation reserves:

- Maintenance of ecological integrity shall be the first priority and the restoration of ecological integrity shall be considered.

- Opportunities for consultation shall be provided.

Other legislation (e.g., Endangered Species Act, 2007), policies, and best practices (e.g., adaptive management) also provide additional direction for protecting Ontario’s biodiversity and contribute to guiding park planning and management.

Ontario Parks is committed to an ecosystem approach to park planning and management. This is accomplished by considering the relationship between the park and the surrounding environment. While the PPCRA pertains only to lands and waters within park boundaries, park managers will consider potential impacts to park values and features from activities occurring on adjacent lands, as well as potential impacts to adjacent lands due to park activities.

This management plan has been prepared consistent with all relevant legislation and provincial policies. The implementation of projects in this provincial park will comply with the requirements of A Class Environmental Assessment for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves (Class EA-PPCR). This may include further opportunities for consultation, as required.

2.1 Ecological integrity

Ecological integrity is a concept that addresses three ecosystem attributes – composition, structure and function. This concept is based on the idea that the composition and structure of living and non-living components in an ecosystem should be characteristic for the natural region, and that the ecosystem’s functions should proceed naturally.

MNRF uses a values and pressures approach to identify and address threats to ecological integrity during park management planning. The Slate Islands park management plan includes policies to manage pressures created by park users on important species at risk values as part of contributing to the maintenance of ecological integrity.

3. Indigenous communities

Indigenous communities in the area include Pays Plat, Red Rock Indian Band (Lake Helen), Biigtigong Nishnaabeg (Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation), and Pic Mobert First Nation. These communities are all within the boundary described by the 1850 Robinson Superior Treaty. Pays Plat, Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, and Pic Mobert have asserted Aboriginal title claim

The Slate Islands archipelago is among many important places in the Northern Superior region which the local First Nations have inhabited and used to engage in traditional activities for generations. The connection to the land that includes the Slate Islands is important to the Anishinaabek traditionally, spiritually and economically.

Pays Plat First Nation is the geographically closest First Nation community to Slate Islands Provincial Park. This proximity has supported their relationship to the islands through their traditional hunting, fishing and other activities. Community members have ancestral connections to the lighthouse keepers of the Slate Islands lighthouse. The community has many stories about their relationship to the Slate Islands and this relationship is reflected in their community identity.

Ontario Parks is aware of the assertions that the Pays Plat First Nation and the Biigtigong Nishnaabeg (Ojibways of the Pic River First Nation) were not signatories to the Robinson Superior Treaty. Ontario Parks is aware that both Pays Plat First Nation and Biigtigong Nishnaabeg assert Aboriginal title and title rights, protected under section 35 of the Constitution Act, and that this management plan encompasses land and water located within the First Nations’ traditional territories.

Slate Islands Provincial Park is located in proximity to one Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) asserted harvesting territory. The closest modern day Community Council that may have an interest is the Superior North Shore Métis Council. Red Sky Métis Independent Nation may also have an interest in this area.

Indigenous communities use the general area for hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering and travel.

Nothing in this document shall be construed so as to derogate or abrogate from any existing Aboriginal, Treaty, constitutional or any other First Nation rights; or the powers or privileges of the Province of Ontario. This includes any rights or freedoms that have been recognized by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763; and any rights or freedoms that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

For greater certainty, nothing in this document shall be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from the protection provided for the existing Aboriginal and Treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada as recognized and affirmed in section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

4. Location and boundary

Slate Islands Provincial Park is located in northern Lake Superior, thirteen kilometres offshore from the town of Terrace Bay (Figure 1). The islands are located within the geographic township of Terrace Bay. The park includes 15 islands in the Slate Islands Archipelago, which are spread over two groups; the smaller Leadman Island group (which includes Leadman, Cape, Spar and Fish Island) is located approximately two kilometres northeast of Patterson Island which, along with Mortimer, McColl, Edmonds, Bowes, Delaute and Dupuis islands, constitutes the major grouping of islands included within the park boundary. The park includes the total land area of the islands and the lakebed between Mortimer and Patterson islands (with the exception of the federally-owned peninsula of Sunday Point, on Patterson Island, where a federal lighthouse complex is located).

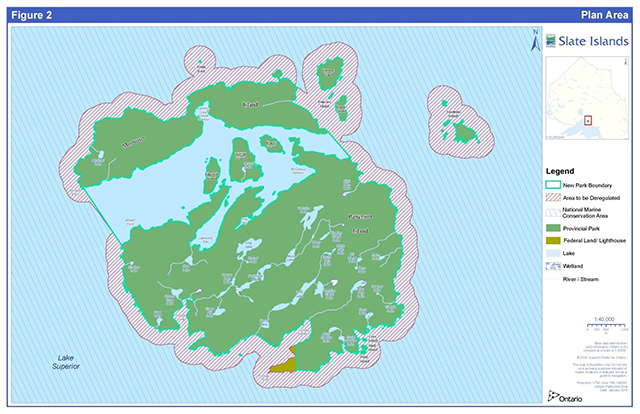

Slate Islands Provincial Park is located within Ecodistrict 3W-5 and the Nipigon Administrative District of the MNRF. The total regulated area encompasses 6,570 hectares that includes a 400 metre buffer surrounding the islands as well as the lakebed between Mortimer and Patterson islands (Figure 2).

In 2009, a process to amend the boundary was initiated to remove the outer waters/lakebed from Slate Islands Provincial Park so that this area can be transferred to Parks Canada for inclusion in the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA). The amendment does not affect the interior channels (i.e., between Mortimer and Patterson islands), but includes the lakebed and waters around the outer shores of Patterson and Mortimer islands, Delaute and Depuis islands, and the Leadman Islands (Figure 2). 1,843 hectares will be deregulated, which represents 28% of the original park area. Following these expected changes Slate Islands Provincial Park will be left with an area of 4,727 hectares.

The lighthouse complex at Sunday Harbour, comprising some 12 hectares, is currently owned by the Government of Canada and is not part of the park. The Federal Department of Fisheries and Oceans is divesting its lighthouse properties, including the Slate Islands property.

The planning area includes the entire regulated area of the park.

5. Provincial park classification

Ontario’s provincial parks are organized into broad categories called classes, each of which has a particular purpose and characteristics which contribute to the overall protected area system. Park classification defines an individual park’s role in providing opportunities for environmental protection, recreation, heritage appreciation and / or scientific research. Classification is a key element in determining the general policy basis for park management, which in turn determines the type and extent of activities that may take place in a park.

Slate Islands Provincial Park is classified as natural environment. Natural environment class parks protect outstanding recreational landscapes, representative ecosystems and provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage. These parks provide high quality recreational and educational experiences. Slate Islands Provincial Park contributes to the fulfilment of the representation target for natural environment class parks in Ecodistrict 3W-5.

6. Purpose and vision statements

6.1 Purpose statement

The purpose of Slate Islands Provincial Park is to permanently protect the ecological integrity of a unique island landscape in Lake Superior including: its geological features, plants, animals, aquatic species and cultural resources, while providing opportunities for compatible, ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation and scientific research.

6.2 Vision statement

Working together in partnership, the planning team has created the following vision statement:

The vision for the Slate Islands Provincial Park is that it will:

- permanently protect the unique Lake Superior wilderness of the Slate Islands by balancing the maintenance of ecological integrity with compatible ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation opportunities, such as angling, boating, kayaking, wildlife viewing and camping;

- provide a refuge for the forest-dwelling woodland caribou and other wildlife species of the park;

- protect and celebrate the globally significant geological features such as the shattercones;

- protect the important arctic disjunct communities and other significant plant species;

- ensure that visitors who travel to the Slate Islands will enjoy its crystal clear waters, its sense of remoteness and isolation, and its ambience of timelessness;

- be a focal point for ongoing scientific research;

- celebrate the cultural stories of the Slate Islands including first peoples, commercial fishing, mineral exploration, logging; and,

- respect Aboriginal and Treaty rights, including traditional Aboriginal uses.

7. Provincial park objectives

There are four objectives for Ontario’s provincial parks that focus on protection, recreation, heritage appreciation and scientific research. Slate Islands Provincial Park makes an important contribution to these objectives.

7.1 Protection

To permanently protect the park’s biodiversity and provincially significant elements of the natural and cultural landscape, and to maintain ecological integrity by controlling development and focusing recreational use.

Ontario’s protected areas play an important role in representing and conserving the diversity of Ontario’s natural features and ecosystems across the broader landscape. Protected areas include representative examples of life and earth science features, and cultural heritage features within ecologically or geologically defined regions. Ontario’s ecological classification system provides the basis for the life science feature assessment, and the geological themes provide the basis for earth science assessment. The protection objective will be accomplished through appropriate park zoning, resource management policies, research, and monitoring. The values and features listed below include those associated with the Slate Islands.

Earth science representation

- an example of a central uplift cone of a meteorite impact crater

- raised cobble beach ridges showing Glacial Lake Nipissing and modern beach levels

- rock platforms, stacks, shorebluffs and other erosional shoreline features of post-glacial times

Life science representation

- a unique faunal assemblage including woodland caribou, beaver and snowshoe hare, which is predator limited to red fox and, occasionally, wolves

- important native lake trout population

- rare arctic disjunct and subalpine plants

- rare treed type: mountain ash (Lake Superior Coastline)

Cultural representation

- the Northern Hunters and Fishers historical theme with theme segments representing the peoples of the Iroquoian and Michigan zones

- early geological exploration and mine development

- the early commercial fishing era

- contemporary role as an important destination for local anglers

- the ‘Forest Industry and Forest Industry Communities’ theme and the ‘North Shore of Lake Superior’ theme segment

7.2 Recreation

To provide visitors with opportunities for ecologically sustainable outdoor recreation, including sailing and powerboating, sport fishing, wildlife viewing, sea kayaking and shoreline camping, and to encourage associated economic benefits.

The park has the potential to contribute to the north shore Lake Superior tourism economy by enabling visitors to enjoy high quality outdoor experiences and learn about important aspects of Ontario’s heritage. The Lake Superior Water Trail is a link in the Trans Canada Trail that passes north of the park along the shore of Lake Superior. The Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area surrounds the park and will also draw new visitors to the Slate Islands.

7.3 Heritage appreciation

To provide visitors with opportunities for heritage appreciation, primarily though unstructured individual exploration of the Slate Islands’ natural and cultural heritage. In addition to its flora and fauna, the Slate Islands have a rich cultural heritage. The park offers insight into prehistoric Indigenous travel and lake faring, early mineral exploration, logging, lighthouses and commercial fishing.

7.4 Scientific research

To facilitate scientific research and to provide reference points to support monitoring of ecological change on the broader landscape.

As a relatively remote and undisturbed ecosystem, the Slate Islands offer opportunities to research aspects of island ecology and biogeography.

8. Provincial park values

8.1 Natural heritage values

8.1.1 Life science

The Slate Islands protect representative landscapes and life science features characteristic of Ecodistrict 3W-5.

The Slate Islands are recognized for their unique terrestrial ecosystems. The islands contain populations of forest-dwelling woodland caribou, beaver and snowshoe hare, which persisted for decades in the absence of substantial predatory pressure. The browsing activities of these herbivore species are also believed to have had considerable impacts on the vegetative communities within the park. Other significant life science features include forests of large American mountain ash, the presence of arctic-alpine disjunct plant species, active shorebird nesting areas on the Leadman Islands and significant lake trout spawning shoals (OMNRF 1986; OMNRF 1987; OMNRF 1991).

Forest-Dwelling Woodland Caribou

Long-term trends of population decline and range retraction amongst the boreal population of forest-dwelling woodland caribou have resulted in their designation as a threatened species at both the national and provincial level (Thomas and Gray 2002; OMNRF 2011). Ontario’s Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan (OMNRF 2009) identifies twelve different caribou ranges within the province. The Slate Islands woodland caribou population falls within the Lake Superior Coastal range, which is separated from the area of continuous caribou distribution to the north by an intervening area over which caribou distribution is relatively discontinuous. The Ontario Government has committed to managing Lake Superior coastal caribou for population security and persistence by focusing on habitat protection and management, and “encourage[ing] connectivity to caribou populations in the north” (OMNRF 2009).

The first definitive contemporary evidence for the presence of woodland caribou on the Slate Islands dates back to the winter of 1907, when tracks (crossing both to and from the mainland) were noted along the surface of the ice that had formed between the islands and the mainland (Middleton 1960 – cited in McGregor 1974). Based on data concerning the regeneration of deciduous browse species and caribou sightings on the islands, as well as historical information on anthropogenic disturbance trends on both the Slates and the mainland, Bergerud (2001) suggested that from 1907 to the mid-1930s, the caribou population was relatively small, with frequent movements of individuals between the islands and the mainland during the occasional winters when an ice bridge formed between them. No definitive evidence for the consistent year-round presence of caribou on the islands exists prior to the 1940s (ibid. 2001). Bergerud (2001) argued that the end of selection logging activities on the islands in approximately 1935, combined with a possible increase in predation pressure on the mainland, caused movement of caribou both to and from the islands to cease and the Slates population to become relatively isolated. Bergerud (2001) suggested that, following this isolation, the population began to increase and eventually entered a “boom and bust” cycle that he believed persisted to the early 2000s, whereby the number of individuals fluctuated between 150 and 450 animals and major “die-offs” were experienced at five year intervals (ibid. 2001).

Ontario Parks Northwest Zone undertook research relating to Slate Islands’ caribou in the 2000s, using several methods to estimate the caribou population, including genetic comparison of caribou throughout the province and a caribou / hare exclosure project, to examine impacts of browsing on plant communities. This work indicated an estimated population of 99 animals in 2009 and also indicated that the boom-bust population cycle was likely no longer occurring.

As well, population viability analysis (PVA) was applied. PVA uses a computer model to indicate the likely probability of persistence of a given population based upon key vital rates including the initial size of the population. The PVA modelling for the Slates’ caribou indicated that the long term probability of persistence was relatively low, although this analysis focussed on data from past boom-bust cycles. The sensitivity analysis indicated the key vital rates are adult female mortality, juvenile female mortality, percentage of successful breeding and initial population size. The carrying capacity regarding forage was also identified as important, as was the vulnerability of a smaller population to extinction from the impacts of random event processes or catastrophic events.

During the winters of 2014 and 2015, ice formed on Lake Superior between Slate Islands and the mainland, allowing wolves to cross to the islands. Ontario Parks, in collaboration with MNRF Science and Research Branch, monitored the wolves through camera traps and a radio collar on one wolf. Through the period from 2014 to 2017, the caribou population on Slate Islands was reduced through wolf predation and caribou leaving the Islands (as reported by local Terrace Bay residents). By December of 2017, MNRF researchers concluded that wolves were no longer present on the Slate Islands.

In January of 2018, MNRF translocated nine caribou (8 cows and 1 bull) from Michipicoten Island Provincial Park to Slate Islands. The caribou translocation was undertaken in order to both augment the caribou population on the Slate Islands, and to ensure persistence of caribou in the Lake Superior Coastal Range while MNRF initiated a broader discussion to seek input into the overall approach for managing the Lake Superior Coastal Range of caribou.

Other significant values

Plants of the arctic-alpine disjunct community have a normal range that includes alpine habitat in British Columbia, the Yukon Territory, or subarctic habitat like that found around Hudson Bay, James Bay and areas south to 53º North. Occurrence of these species in the area is significant due to the distance of these plants from their normal range; this plant community is known as the Great Lakes Arctic-Alpine Basic Open Bedrock Shoreline Type S-3.

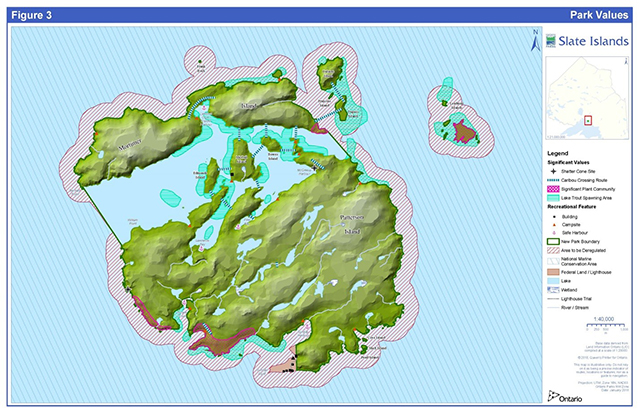

The waters surrounding the Slate Islands serve as habitat for what is considered to be an important population of lake trout; spawning beds located within park boundaries are illustrated in Figure 3.

The Slate Islands provide important habitat for a large number of avian species. For example, the Leadman Islands provide an active nesting area for shorebirds (including herring gull and great blue heron). Other avian species known to use the Slate Islands as nesting habitat include red- breasted merganser, American bittern, grey jay (Dalton 1985), bald eagle (W.J. Dalton pers. comm., 2002) and a variety of warblers (OMNR 1986). The islands also serve as a migratory stopover for several birds, including Canada geese and snow geese (ibid. 1985).

8.1.2 Earth science

According to D. Webster (personal communication, 2014), the Slate Islands are recognized for their unique earth science features, including an impact crater with remarkable shatter cones.

The Slate Islands were formed by a meteorite impact, likely during the Ordovician Period about 450 million years ago (based on recent age determinations of impact-generated rocks). Investigation has also led to estimates that the impact point was in the central to west-central portion of Patterson Island. The impacting body is estimated to have been approximately 1.5 km in diameter.

The sequence of events that led to the creation of the islands is as follows. A meteorite hit the earth’s surface generating hypervelocity shock waves. These shock waves forced the ground below the impact site downwards and outwards creating a steep sided and unstable transient crater. Following this, the rock beneath the crater rebounded upwards into a cone-shaped central peak feature. This rebounding was due to the catastrophic removal of the confining overlying rock as it is pulverized by the meteorite’s impact. The removal of the overlying rock was rapid (it took approximately one minute to complete) and deep (approximately 1.5 km). Because of the instability of the transient crater, it collapsed into the form of the final crater. The time lapse up to this point, from impact to final crater form, was approximately ten minutes. The final crater then began to experience long-term erosion and eventually became the feature we see today.

This catastrophic sequence of events is analogous to a drop of water hitting the surface of a still pond.

Since the early 1990s, a team of research scientists from NASA’s Lunar and Planetary Institute have been studying the islands and have found what are considered to be the world’s largest shatter cones. These shatter cones (also known as mega cones), are located between Fisherman’s Harbour and McGreevy Harbour on Patterson Island. These features are at least 10 metres, and possibly up to 20 metres, in length.

In addition to the ancient shatter cones and brecciated rocks, the Slate Islands contain raised cobble beaches representing more recent glacial lake stages, as well as modern beaches, rock platform stacks, shorebluffs, and other post-glacial erosional features.

8.1.3 Ecological functions/processes

The forest cover of the Slate Islands is dominated by mixedwoods, with “mixed forest – mainly deciduous” and “mixed forest – mainly coniferous” covering the majority of the terrestrial land base (i.e., roughly 48% and 37%, respectively), with some representation of “dense coniferous forest” (i.e., 11%) and minimal (i.e., less than 1.5%) representation of “dense deciduous”, “sparse deciduous” and “sparse coniferous” forests, as well as “bedrock outcrops”.

With the exception of the small but notable contribution made to achieving representation benchmarks for three landform/vegetation types (i.e., “bedrock-mixed forest/mainly coniferous”, “bedrock-mixed forest/mainly deciduous” and “bedrock-dense coniferous forest”), Slate Islands Provincial Park does not play a major role in the achievement of ecodistrict level representation goals. This result is not surprising, considering the relatively small size of the park. Although the representation-related value of the park is not very high, the Slate Islands are an extremely valuable component of Ontario’s network of parks and protected areas from a life science perspective.

As a result of the relative insularity of the Slate Islands and the simplified nature of the faunal community which inhabits them, the park contains a unique ecological system that can serve as a valuable example of the types of species-specific population dynamics, inter-species interactions and community structures that can occur in island systems. Because almost all of the medium to large-sized mammals that consistently inhabit the Slate Islands are herbivorous, the park has provided, and can continue to provide, invaluable opportunities for studying the population dynamics and competitive interactions of prey species in the absence of major predators. It can also provide unique insights into the long-term effects of intense grazing and browsing activities on the diversity and composition of boreal plant communities. From a conservation perspective, the research opportunities associated with the woodland caribou population are particularly significant, as they have the potential to provide greater insight into the factors (i.e., declining quantity and quality of suitable habitat, increased exploitation and predation, greater exposure to disease [Godwin 1990]) believed to be responsible for the local extirpations and population declines that this species at risk has experienced across the southern half of Ontario and throughout Canada’s boreal region (Godwin 1990; COSEWIC 2002).

The park is considered to be one of the most important island habitats for arctic-alpine plants in Lake Superior (M. Oldham, pers. comm. 2002). As such, the islands have high potential research value with respect to gaining a greater understanding of the distribution and status of arctic-alpine disjunct species (ibid. 2002).

The park plays an important ecological role in relation to the greater aquatic and terrestrial landscapes, providing spawning habitat for lake trout (OMNRF 1986) and serving as summer habitat or as a migratory stopover for a variety of bird species.

8.2 Cultural heritage values

Cultural heritage values include any resource or feature of archaeological, historical, cultural, or traditional use significance. This may include archaeological resources, built heritage or cultural heritage landscapes. A Topical Organization of Ontario History (1975) is used to classify representative historical resources in parks and protected areas.

The Slate Islands possess a large number of cultural and historical values and they offer representation of a number of historical themes. Two archaeological sites have been found; both of these sites are small campsites from the Terminal Woodland cultural period and are significant in that they are indicative of the “considerable lake-faring skills of the native inhabitants” (OMNR, 1987). These archaeological sites contained evidence of a link to the People of the Iroquoian and Michigan Zones, thereby representing the ‘Northern Hunters and Fishers’ theme in the Topical Organization of Ontario History.

Logging activities occurred on the Slate Islands in the 1930s. Prior to 1935, timber harvesting was carried out, and camps were established on the islands. After 1935, the islands were used as booming grounds for the shipment of timber to the United States. The campsites, remains of an old barge, coal docks, and old roads, are evidence of this era. These features represent an important part of the history of the park and link to the ‘Forest Industry and Forest Industry Communities’ theme and the ‘North Shore of Lake Superior’ theme segment in the Topical Organization of Ontario History.

A lighthouse was first established on the Slate Islands in 1902. The present location is not part of the park; however it is of interest to park users who visit and hike up to the lighthouse.

The historical sites associated with Slate Islands Provincial Park include:

- remnants of coal docks and coal yard from the 1930s, (McColl Island);

- remains of an old barge and a logging campsite (McGreevy Harbour);

- the remnants of two old logging camps (Logging Camp Lake and Peninsula Lake);

- two mining adits (Patterson and Mortimer Islands); and

- the lighthouse facility at Sunday Harbour (adjacent to the park).

These sites represent Ontario’s history of forestry operations and mining.

No other cultural heritage values are known.

8.3 Outdoor recreation values

The Slate Islands are a popular recreational sail and powerboat destination for both local and regional communities. The park is also a longstanding destination for powerboaters and sailors from the USA. The islands offer a protected harbour which is strategically important to this area of the lake. Boaters heading toward Sault Ste. Marie use the Slate Islands as a staging point while waiting for good weather to safely cross to the Sault. The Slate Islands offer good deep anchorages for boats of all sizes.

The Thunder Bay Yacht Club uses the park as one of their potential destinations in their annual sailing regatta known as the SUNORA, or Superior North Shore Regatta, a one-week race/cruise through the islands of Lake Superior, Thunder Bay and Nipigon Bay, for both power and sailboats.

There are thirteen natural harbours / anchorages provided by the sheltered inner waters and coves of the Slate Islands (Figure 3). The entire interior channel between Mortimer Island and Patterson Island offers a reasonable amount of shelter, while some of the larger coves and bays in this area provide additional protection from the elements. McGreevy Harbour, Lambton Cove, Lawrence Bay and Pike Bay, all within the interior channel, are the most heavily used harbours in the park. Sunday Harbour is also used by boaters.

Sport fishing for lake trout has historically served, and still appears to serve, as a primary recreational activity for visitors to the islands.

The kayaking opportunities at the Slate Islands have become a major draw to the park, and the islands are included in many sea-kayaking guides (1999, 2002, 2008, and 2012) for Lake Superior, as well as in many electronic journal articles and internet blogs. Kayaking parties either completely circumnavigate the islands, or stay in the shelter of the interior channel at one or more base camps and take day trips. There are a number of commercial outfitters who offer kayaking trips to the Slate Islands throughout July and August. These trips are usually between four and seven days in length and either make the crossing from Terrace Bay or use a local charter company to get out to the islands. At least four Ontario outfitters offer trips to the Slate Islands and a number of other eco-tourism companies, from as far away as Edmonton, organize groups and then employ a local outfitter to run the trip. For a number of years, American outfitters have also utilized the Slate Islands.

Five camping areas were identified / designated in the 1991 park management plan, all of which were associated with natural harbours. With the advent of sea kayaking, an additional eight campsites have been developed by kayakers in sheltered coves on the outer peripheries of Mortimer and Patterson islands, without authorization from Ontario Parks (Figure 3). These peripheral campsites are used by parties circumnavigating the main islands. There are no established campsites on the smaller Leadman, Depuis or Delaute Islands.

9. Summary of pressures

In 1986, an estimated 0-5 boats (sail and power) visited the park per day in late May and June, and 5-10 boats visited per day during July and August. During the peak season, 1-4 of these boats entered the McGreevy Harbour/Lawrence Bay area per day. Using the median of the two ranges, these numbers translate into an estimated seasonal total visitation of over 550 boats. The actual number of visitors is probably much higher, since these numbers do not take into account the fall shoulder season (Barry 2002).

The use of the islands by the boating community is believed to have increased significantly since 1986 in light of recent publicity in popular yachting and cruising magazines. The Lake Superior NMCA Human Uses Report (1999), reported the Slate Islands to have a high degree of powerboat use and a moderate degree of use by sailors and yachters. Many sailboats and cruisers were also observed during the 2001 recreation inventory undertaken by Ontario Parks staff, which was conducted on a weekday in the height of the summer season. Similar observations have been made by staff during fieldwork since then.

Known and potential impacts associated with the use of natural harbours include: noise, conflicts with other users that impact the quality of the experience, water and air pollution (fuel spills / leakage), litter/garbage, introduction of alien/invasive species via bilge water, impacts to the fishery, and disturbance of wildlife. Most impacts are limited to the areas around the anchorages used by boaters; however, some impacts may increase in intensity as the Slate Islands become more popular as a boating destination.

Although there are no specific numbers on the amount of sea kayaking at the Slate Islands, there are indications of the popularity and growing importance of this activity. The NMCA Human Uses Report (1999) indicated that kayaking was only moderately popular at the Slates when compared to other areas such as the Rossport Islands. However, paddling to the Rossport Islands is a relatively short day trip while the Slate Islands are one of the most popular multi-day kayaking tours along the north shore. A query was sent out to known outfitters in the summer of 2012; responses indicated that approximately 35 groups are shuttled or toured each season. Park staff also receive between 20 and 30 telephone and email queries annually. A conservative estimate of five people in a party would indicate that there are more than 300 individuals using the Slate Islands for kayaking each year.

Known and potential impacts associated with camping and day use include: conflicts with other users (e.g., boaters); soil compaction; faecal contamination of shoreline and water bodies; damage to vegetation and clearing of woody debris (e.g., tree cutting, trampling); human-caused wild fires; phosphate loading of water (e.g., dish detergent, shampoo, etc.); impacts to wildlife (e.g., feeding, improper storage of food and/or improper waste disposal, creating nuisance situations); and litter/garbage. Most impacts are limited to the camping areas used by sea kayakers and boaters; however, some impacts may increase in intensity as the Slate Islands become more popular as a sea kayaking destination.

Wildlife viewing of woodland caribou, while a popular draw for visitors to the Slate Islands, can lead to harassment of individual animals if, for example, the park visitor pursues an animal through the bush or into the water for the purpose of filming or photography, or if a park visitor allows a dog to chase caribou. Some park visitors are known to feed caribou. Cows with calves are particularly vulnerable to harassment and the resultant stress to the animals may compromise viable reproduction and population stability.

As a destination for scientists and people interested in geology, the Slate Islands are vulnerable to the collection of mineral specimens, and rock samples.

10. Zoning

Lands within Slate Islands Provincial Park are zoned based on the sensitivity of their natural and cultural values and need for protection. Different types of zones provide for varying degrees of development, recreational uses and management practices. These policies are outlined in Section 11.

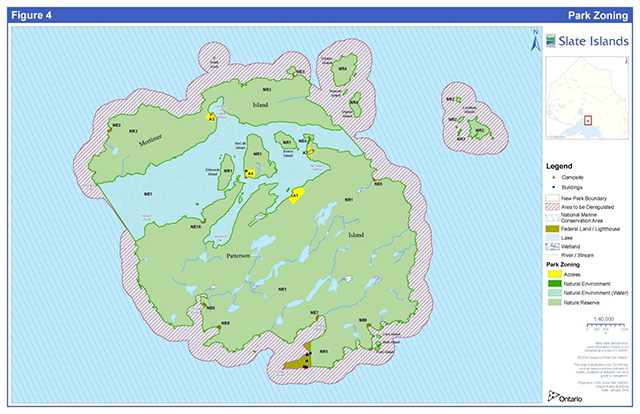

The three categories of zones designated for Slate Islands (natural environment, nature reserve and access) are compatible with natural environment class parks in accordance with the Ontario Provincial Parks: Planning and Management Policies (see Figure 4). In the present zoning configuration, the bulk of both Mortimer and Patterson islands as well as the associated archipelago are zoned as nature reserve, while nine natural environment zones have been designated to enable camping along the periphery of the two larger islands. As such, 78% of the park is included in nature reserve zones, 21% in natural environment zones and less than 1% in the access zones.

10.1 Access zones

A-1 McGreevy Harbour (3 hectares)

A-1 is generally defined as the land area extending 100 metres back from the shore of McGreevy Harbour; this large open area that is heavily browsed has multiple tent sites

A-2 Fisherman’s Harbour (3 hectares)

A-2 is generally defined as the land area extending 30 metres back from the shore of Fisherman's Harbour including the headland: this large flat open area has one campsite with ten tent sites adjacent to the beach. There is a pit privy (installed in 2014).

A-3 Lambton Cove / Copper Harbour (3 hectares)

A-3 is generally defined as the land area extending 100 metres back from the southwest shore of Lambton Cove / Copper harbour; this area has a nice beach framed by bedrock and has one campsite with nine tent sites. The bedrock has large metal eyelets dating back to log booming days; these are now used by boaters to tie up to shore. Lambton Cove / Copper harbour has deep water that provides anchorage for larger boats. There is a pit privy (installed in 2014).

A-4 McColl Island (6 hectares)

A-4 is generally defined as a square set in the southwest corner of McColl Island extending from waters’ edge inland for 100 metres; this area has one campsite with four tent sites. Existing development includes the “Come ‘n rest” cabin with a small bunkie and an outhouse which are in a state of disrepair. There is a pit privy (installed in 2014).

Management Intent

Access Zones (A) serve as staging areas where minimum facilities support the use of nature reserve zones and less developed natural environment zones. Development will be limited to campsite amenities at designated sites such as formal tent pads, picnic tables, privies, fire rings, and park shelters, as well as docks (A-2 and A-4) and mooring balls in the waters adjacent to A-1, A-2 and A-3 zones. Park interpretive, educational, research and management facilities may be developed in the A-4 zone. The remaining cabin, along with the associated Bunkie and outhouse, will be assessed for cultural heritage value and restored/rehabilitated or removed and the sites cleaned up. Roofed accommodation may be considered in all access zones when use levels merit. This may include Adirondack style basic roofed shelters, or in A1 or A2 zones as rustic/remote cabins (Section 11.14). Existing tent sites may be consolidated or rationalized. Composting toilets may be provided at one or more sites when use levels merit.

A-4 will eventually become the registration / staging area for all park visitors. Tourist operators will be encouraged to use the A-4 zone for pick-up and drop-off of their clientele. Charter boats will also be encouraged to use this zone.

10.2 Natural environment zones

NE-1 Lake Superior Natural Environment Zone (2565 hectares to be reduced to 1010 hectares)

This zone includes all of the Lake Superior lakebed within Slate Islands Provincial Park, between Patterson and Mortimer Islands

NE-2: Northwest Mortimer Lagoon Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area set back 100 metres from the beach in the small cove on the west side of Mortimer Island. This zone provides refuge on crossing from the mainland. This zone designates a camp site with nine tent sites.

NE-3: Northeast Mortimer Lagoon Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area set back 100 metres from the beach in the area of the small peninsula on the northeast side of Mortimer Island. This zone provides refuge on crossing from the mainland. This zone designates a camp site with three tent sites.

NE-4: Fisherman’s Cove North Natural Environment Zone (4.0 hectares)

This zone is generally described as the peninsula north of Fisherman’s Harbour on Patterson Island. Although three camping areas are present in this area this zone designates two camp sites on both sides of the cove. The northern (third) campsite will be cleaned up and posted no camping to provide a buffer for the caribou crossing activity in this area. Site 1 has five tent sites set back from the beach. Site 2 has seven tent sites set back from the beach; this site has been developed with multiple tables, benches, and a dock. These improvements will be removed and the site cleaned up.

NE-5: High Dam Lake Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area set back 100 metres from the beach in the small cove on the northeast side of Patterson Island. This zone designates a camp site with seven tent sites, used by parties circumnavigating the island.

NE-6: South Harbour Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area set back 100 metres from the beach in the small cove on the southeast side of Patterson Island. This zone designates a camp site with seven tent sites, used by parties circumnavigating the island.

NE-7: Sunday Harbour Natural Environment Zone (4.0 hectares)

This zone is generally described as the sheltered area southwest of the creek, set back 100 metres from the beach in Sunday Harbour on the south side of Patterson Island. This zone designates a camp site with nine tent sites, used by parties circumnavigating the island.

NE-8: Horace Cove East Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area set back 100 metres from the beach in Horace Cove East on the southwest side of Patterson Island. This zone designates a camp site with eight tent sites, used by parties circumnavigating the island.

NE-9: Horace Cove West Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area in the cove on the east side of Horace Cove, on the south side of Patterson Island, set back 100 metres from the beach. This zone designates a camp site with several tent sites, used by parties circumnavigating the island.

NE-10: Northwest Cove Natural Environment Zone (1.0 hectare)

This zone is generally described as the area set back 100 metres from the beach in the cove northwest side of Patterson Island. This zone designates a camp site with several tent sites, used by parties circumnavigating the island.

Management Intent

Natural environment (NE) zones include natural landscapes, which may permit certain development required to support low intensity recreational activities.

NE-2 through NE-10 provide locations for sea kayakers and boaters to camp overnight while travelling to, or circumnavigating, Mortimer and Patterson Islands. Tent pads, fire rings, picnic tables and pit toilets may be provided as resources permit. Roofed accommodation in the form of Adirondack style shelters may be constructed in the NE-2 through NE-10 zones to provide emergency shelter (Section 11.14). Park interpretive and educational facilities may be developed in these zones. Existing tent sites may be consolidated or rationalized. Existing structures in NE-4, including the dock, will be removed. Mooring balls and floating docks may be provided in NE-1 in Copper Harbour/Lambton Cove, Lawrence Bay and Pike Bay.

Ontario Parks may place temporal restrictions on the use of all or some of these campsites during caribou calving (May to early June) and nursery (June) periods.

10.3 Nature reserve zones

NR-1 Patterson Island Nature Reserve zone (2865.0 hectares)

This zone can be generally described as all of Patterson Island not designated as access or natural environment zone. This zone also includes Edmond, most of McColl, Bowes, Cove, Shell and Pearl islands. NR-1 is designated to protect the park’s natural and cultural values including: arctic-alpine disjunct communities, lichen barrens on raised shorelines, woodland caribou and beaver habitat, and other wildlife habitat. Cultural values include old logging camps, a mining adit, and a coal yard. Geological values include two shatter cone sites, raised cobble beaches that represent glacial Lake Nipissing, and modern beach lines and rock platforms, stacks and shorebluffs, and other post-glacial erosional features.

NR-2 Leadman Islands Nature Reserve zone (26.0 hectares)

This zone can be generally described as all of the Leadman Islands which are located approximately four kilometres east of Mortimer Island and two kilometres east of Patterson Island. NR-2 is designated to protect the park’s natural values including: arctic-alpine disjunct communities, and shorebird nesting habitat. This zone also provides potential woodland caribou, hare and beaver habitat; although as of 2014 there is no sign of these on the islands. There are no campsites established on these islands.

NR-3 Mortimer Island Nature Reserve zone (715.5 hectares)

This zone can be generally described as all of Mortimer Island not designated as access or natural environment zone. This zone also includes Frank Rock. NR-3 is designated to protect the park’s natural and cultural values including: arctic-alpine disjunct communities, woodland caribou and beaver habitat, and other wildlife habitat. Cultural values include a mining adit. Geological values include mafic and felsic volcanics, breccias, and modern beach lines and rock platforms, stacks and shorebluffs, and other post-glacial erosional features.

NR-4 Dupuis/Delaute Islands Nature Reserve zone (55.0 hectares)

This zone can be generally described as all of the Dupuis/Delaute Islands which are located approximately 700 metres east of Mortimer Island. NR-4 is designated to protect the park’s natural values including: arctic-alpine disjunct communities, woodland caribou, hare and beaver habitat, and shorebird nesting habitat. There are no campsites established on these islands.

Management Intent

These nature reserve zones will protect wildlife habitat and ecological processes by limiting recreation activities and development. No new interior trails will be developed in order to minimize disturbance to caribou and other wildlife. Camping is not permitted in nature reserve zones.

11. Policies

Slate Islands Provincial Park will be managed in accordance with the policies for natural environment class parks as per Ontario Provincial Parks: Planning and Management Policies (OMNR 1992), and other applicable park policies. All activities undertaken in the park must comply with the Class EA-PPCR, where applicable.

Maintenance of ecological integrity is the first priority in the planning and management of the park, in accordance with the PPCRA. Management direction is intended to address negative impacts associated with park use on ecological and cultural values, and public safety concerns.

An adaptive management approach will be applied to resource management activities in the park. Adaptive management allows management strategies to be changed as required, in response to monitoring and analysis of past actions and experiences. Management strategies will be assessed and modified if necessary to achieve the desired result.

First Nations having Aboriginal and Treaty Rights will continue to carry out traditional harvesting practices and land use activities within their respective traditional territories. Ontario Parks will consult with, and integrate traditional ecological knowledge from, the local First Nations in the management activities for Slate Islands Provincial Park.

11.1 Industrial

The following uses are not permitted in Slate Islands Provincial Park:

- Commercial timber harvest,

- Extraction of sand, gravel, topsoil or peat

- Generation of electricity (except for in-park use)

- Mining and prospecting, staking mining claims, developing mineral interests

11.2 Fisheries

Fisheries management

As part of MNRF’s Ecological Framework for Fisheries Management, Fisheries Management Zones (FMZs) are the main spatial unit for planning and management of fisheries in Ontario. The Slate Islands are within FMZ 9. MNRF is currently determining how best to undertake fisheries management planning on a landscape/FMZ basis and is working with FMZ Advisory Councils to set objectives and identify strategies for managing fisheries under this model. The FMZ approach to fisheries management planning does not preclude applying different management approaches in provincial parks in order to achieve fisheries and aquatic ecosystem objectives for the planning area and to meet the objectives of the PPCRA.

Fisheries monitoring and management is undertaken on waters adjacent to the Slate Islands by the Upper Great Lakes Management Unit (UGLMU). On the Great Lakes, the fish community objectives are set for the entire lake by multi-agency Lake Committees, organized through the Great Lakes Fishery Commission (GLFC): for Lake Superior, this committee is comprised of representatives from MNRF, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR), Wisconsin DNR, Michigan DNR, Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, US Fish & Wildlife Service, US Geological Survey, and two American Indian Band resource authorities. Because of this structure, the FMZ 9 Advisory Council does not have a mandate for developing an independent set of management objectives for Lake Superior; at some point in the future, the Lake Superior Committee will revisit the fish community objectives, and FMZ 9 will likely be engaged for comment, though they won’t be direct participants in the process

Ontario Parks will work with Pays Plat First Nation, Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, the Anishinabek/Ontario Fisheries Resource Centre (AORFC) and the UGLMU, to provide opportunities to participate in the assessment and monitoring of the Slate Islands fisheries.

Sport fishing

Sport fishing occurs on Lake Superior, in park waters and adjacent to the park. Sport fishing is subject to provincial and federal fisheries regulations.

Commercial fishing (existing and new)

There are currently no conditions which restrict commercial fishing around the Slate Islands. Two commercial fishing licences are issued annually by the UGLMU. Neither of the two licences abutting the Slate Islands have conditions which restrict them from fishing right up to the shore of the islands. These licences have been inactive in recent years. If necessary, Ontario Parks will work with the UGLMU to have conditions added to the licences to restrict commercial fishing activity within the park boundary in areas associated with the spawning shoals.

Commercial bait harvesting (existing and new)

There is no opportunity for commercial bait harvesting associated with Slate Islands Provincial Park.

Stocking

There is no stocking associated with Slate Islands Provincial Park.

Spawn collection

The MNRF uses the Slate Islands’ coastal fisheries as a source of lake trout brood stock. The local genetic strain of lake trout is an important component of the provincial fish culture program. Wild spawn collection from the Slate Islands’ waters enables an infusion of wild genetic material to refresh fish culture brood stock, and is permitted to continue. Ontario Parks will work with MNRF’s fish culture section to support future wild spawn collection as required.

11.3 Wildlife

Sport hunting

Sport hunting is not permitted in Slate Islands Provincial Park.

Commercial fur harvest (existing and new)

The park is not part of any registered traplines. New trapline operations are prohibited.

Wildlife habitat management

Wildlife habitat management will include monitoring for change over time and will be directed toward maintaining the natural population dynamics of native species.

Wildlife habitat management activities may be identified through a vegetation/wildlife management plan.

Wildlife habitat protection shall be a key consideration for any development or new activity proposed in the park. As most of the land in the park is zoned as nature reserve, only minimal development will be permitted in order to avoid negative impacts to wildlife habitat (e.g., backcountry campsites in natural environment zones).

Wildlife population management

The management of wildlife in the park will be directed toward promoting healthy and diverse populations and may be undertaken in conjunction with broader MNRF initiatives such as Ontario’s Woodland Caribou Conservation Plan (MNRF 2009). The park is in Wildlife Management Unit 21A, in the MNRF Nipigon District. It is also located within the Lake Superior Coast Range for Caribou.

Wildlife population(s) may be controlled when human health or safety risks arise, or when the values for which the park has been established are in jeopardy Where control is necessary, techniques that have minimal effects on other components of the park’s ecological integrity will be used. Wildlife population control will be based on future assessments as required; it may be undertaken directly by Ontario Parks, or through partnership with Ontario Parks.

The capture and tagging/collaring of wildlife for research purposes is permitted. Wildlife species may be transferred out of the park for research or restocking purposes. Research, tagging and transferring of wildlife will require necessary permits or approvals from Ontario Parks.

Active wildlife management, if necessary, through the most appropriate means is permitted to protect existing native wildlife populations and to support ecological integrity.

11.4 Vegetation

Vegetation management

Management of vegetation within the park will be directed toward maintaining the natural succession of vegetation. Maintaining or enhancing woodland caribou habitat will also be a key consideration.

Missing native species may be re-established and existing populations replenished, if biologically feasible and acceptable.

Any development that requires the removal of vegetation will be supported by a vegetation inventory, in accordance with approved site plans.

Vegetation management may be carried out to protect or enhance species’ habitat. Techniques used may include suppression or non-suppression of wildfires, prescribed fires or prescribed burning of vegetation.

Areas that are adversely affected by use will be rehabilitated whenever possible using plant species native to the park.

Tree removal

The removal of hazard trees by authorized personnel will be permitted in all zones where safety is a concern (e.g., campsites).

Vegetative insect and disease control (native)

Insects and diseases are a natural component of forest ecosystems. Infestations of forest insects and diseases will be monitored and assessed. Native species may be controlled in the access and natural environment zones where aesthetic, cultural or natural values are threatened. If control measures are undertaken, they will be applied to minimize effects on the park ecosystems or for human health and safety purposes. Biological controls will be used whenever possible.

Vegetative insect and disease control (alien)

Infestations of forest insects and diseases will be monitored and assessed. Non-native insects and diseases may be managed in all zones where aesthetic, cultural or natural values are threatened. If control measures are undertaken, they will be applied to minimize effects on the park ecosystems or for human health and safety purposes. Biological controls will be used whenever possible.

Harvesting

Commercial harvesting of trees and non-timber forest products (e.g., mushrooms, moss and Canada yew) is prohibited.

11.5 Forest fire management

Fire is an important ecological process fundamental to maintaining and restoring ecological integrity within protected areas of the Northwest and Northeast fire regions.

Fire response and suppression

Fires which occur will be assessed and will receive the most appropriate response aimed at limiting losses from fire damage, maximizing resource and ecological benefits and lowering costs, in accordance with the Wildland Fire Management Strategy (2014).

Fire management direction for the Slate Islands is included in The Islands of Lake Superior Fire Response Plan (2009), which guides fire response for the Crown owned islands of Lake Superior until such time as a fire management plan can be developed.

All fires on the islands of Lake Superior will receive a response based on values at risk that also considers resource management objectives, suppression costs, and fire program capacity. The focus will be to monitor fire starts and provide an appropriate response to prevent personal injury, value loss and social disruption that may be associated with forest fires. Fires on the islands of Lake Superior that threaten human life, property or other values will receive a full response. Sustained action, if required, will be guided by an approved Fire Assessment Report.

Fire management will be undertaken in co-operation with Aviation, Forest Fire and Emergency Services (AFFES). AFFES will endeavour to use minimal impact suppression techniques whenever feasible when protecting sensitive features. These “Light on the Land” suppression techniques do not unduly disturb the landscape; examples may include limiting the use of heavy equipment, or limiting the felling of trees during fire response.

Prescribed burning

Prescribed burning may be used to promote natural patterns of forest succession. Prescribed burning may also be used to reduce hazardous conditions, maintain or enhance ecological integrity, or manage habitat of species at risk. Any prescribed burns will be planned and implemented in accordance with MNRF Prescribed Burn Planning Manual and the Class EA-PPCR.

11.6 Species at risk

Given the status of all boreal forest-dwelling woodland caribou populations, the specific commitment of the Ontario Government to maintain existing Lake Superior Coastal caribou populations (OMNR 2009) and the value of the Slates caribou as one of the most unique life science attributes of Slate Islands Provincial Park (OMNR 2005), park planning and management decisions made for the Slate Islands will consider the condition and viability of the Slate Islands caribou population. Management decisions that either promote the long-term persistence of the Slate Islands caribou population or are likely to have little or no negative impact on their persistence will be favoured over those that are likely to compromise the viability of the population.

Caribou cows are especially sensitive to disturbance during the calving and nursery period, which, on the Slate Islands, occurs from May through June. Although the evidence indicates that pregnant females on the Slates preferentially select patches of deciduous-dominated forests for calving, locations vary from year to year, making the protection of specific areas ineffective (OMNR 2005). Ontario Parks may place temporal restrictions on terrestrial recreational activities (e.g., camping, hiking, wildlife viewing) during caribou calving (May to early June) and nursery (June). Domestic pets (dogs) are prohibited throughout the park at all times of the year.

Species at risk will be managed in accordance with the Endangered Species Act, 2007 and other applicable legislation.

Further research on species at risk may be undertaken to assess the need for habitat protection, restoration or recovery planning.

11.7 Alien and invasive species

Alien species are plants, animals and microorganisms introduced by human action outside their natural past or present distribution. These species may originate in other continents or countries, or from other parts of Ontario or Canada.

Invasive species are harmful alien species whose introduction or spread threatens the environment, the economy, or society, including human health.

There are no terrestrial invasive species known in Slate Islands Provincial Park. Sea Lamprey and rainbow smelt are examples of aquatic invasive species present in Lake Superior.

Where possible, actions will be taken to eliminate or reduce the threat of invasive species on the park’s natural biodiversity. Where invasive species are already established and threaten park values, control strategies may be implemented where feasible, following established guidelines.

Visitors may be informed of species that may threaten park ecosystems if introduced.

11.8 Cultural heritage

Cultural heritage resource management

Cultural heritage resources in Slate Islands Provincial Park will be managed to ensure their protection, and to provide opportunities for heritage appreciation and research, where these activities do not harm the resource. This will be achieved through zoning and by controlling any recreational activities, development and research that may occur in these areas.

Ontario Parks will work with Pays Plat First Nation and Biigtigong Nishnaabeg to develop a protocol for use if new cultural artefacts and spiritual sites associated with indigenous culture are found. Ontario Parks will work with these First Nations to develop a monitoring protocol for the protection of existing cultural sites.

Ontario Parks will consult with Pays Plat, Biigtigong Nishnaabeg, other nearby First Nations, and nearby Indigenous communities on matters pertaining to: Indigenous history, any additional archaeological sites found within the park associated with Indigenous culture, interpretation of First Nation’s history, and appropriate treatment of cultural artefacts. The precise location of any of the existing or any newly discovered Indigenous cultural sites, including burial sites, will not be disclosed to the public.

Cultural heritage resources will be protected, maintained, used and disposed of in accordance with existing applicable legislation and policies. If cultural heritage resources are discovered, MNRF will follow requirements as outlined in A Technical Guideline for Cultural Heritage Resources (2006) or other relevant cultural heritage policy. In the event of a discovery of additional archaeological sites, Ontario Parks will work with the appropriate authorities to identify and assess the significance of the site.

Under the PPCRA, it is unlawful to disturb an archaeological site in a park (O Reg. 347/07 2(1)(b) (2)(c)).

Except with written authorization of the park superintendent, the removal of artefacts or destruction of historical features is prohibited by the PPCRA.

11.9 Water management

Surrounding land use does not currently have a direct impact on recreational water quality. Water management activities (on Lake Superior) do not affect the park.

11.10 Land

Management of the park's land base will be directed toward maintaining the natural landscape and ecological integrity of the park.

Private dispositions

There is no authorized private use on the Slate Islands. No land disposition for private use is permitted.

Land securement

Ontario Parks will support, in principle, the acquisition of property for addition to the Slate Islands Provincial Park, if the acquisition will enhance the values or management of the park. Acquisition or securement will be subject to funding and willingness of the owners to sell or lease their properties or enter into a conservation easement. Priority areas for addition to provincial parks are focused on lands adjacent to the provincial park and with similar natural and cultural heritage values. Land securement priorities for the Slate Islands are focused on the adjacent federal lighthouse property at Sunday Point, which is the only land parcel associated with the park that is not regulated under the PPCRA.

Energy transmission and utility corridors (existing)

There is an underwater electrical power cable that ran from the lighthouse complex to the town of Terrace Bay that was installed in 1980; this cable is no longer connected to the mainland.

Dark-Sky Preserve

Ontario Parks may pursue the designation of Dark-Sky Preserve by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada to enhance the protection of the quality of the night sky over Slate Islands Provincial Park by minimizing light pollution. A Dark-Sky Preserve is an area in which no artificial lighting is visible and active measures are in place to educate and promote the reduction of light pollution to the public and nearby municipalities.

11.11 Science and education

Research, inventory and monitoring

Slate Islands Provincial Park provides invaluable opportunities for studying the population dynamics and competitive interactions of prey species in the absence of major predators. It can also provide unique insights into the long-term effects of intense grazing and browsing activities on the diversity and composition of boreal plant communities. From a conservation perspective, the research opportunities associated with the woodland caribou population are particularly significant, as they have the potential to provide greater insight into the factors believed to be responsible for local extirpations and population declines.

The islands have high potential research value with respect to gaining a greater understanding of the distribution and status of arctic-alpine disjunct species.

The park appears to play an important ecological role in relation to the greater aquatic and terrestrial landscapes, providing spawning habitat for lake trout (OMNR 1986) and serving as summer habitat or as a migratory stopover for a variety of bird species. Further research (during breeding and migratory seasons) is needed to obtain a comprehensive picture of the different avian species that utilize the Slates Islands and their relative abundances.

Research may be needed to determine whether recreation use is impacting the values in the park. An extensive inventory of the arctic disjuncts was undertaken in 2014 and ongoing monitoring will occur as needed. Earth and life science inventories should be reviewed and updated on a regular basis to help identify additional areas where significant features overlap with and may be affected by recreational activity. Life science inventories should quantify invasive species and determine if any invasive species are increasing over time. Inventory and assessment of use of smaller islands by nesting waterfowl as well as use as caribou calving and nursery habitat is required.

Ontario Parks encourages scientific research by qualified individuals who can contribute to the knowledge of natural and cultural history and to environmental management in provincial parks. Research activities require authorization issued under the PPCRA, consistent with Research Authorization for Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Policy. Research is subject to park policies unless special permission is given. Research must meet all requirements under applicable provincial and federal legislation, and may require additional permits or approval (e.g., MNRF Wildlife Scientific Collector authorization or Endangered Species Act permits). Temporary facilities in support of approved research and monitoring activities may be considered.

Ontario Parks will work with Pays Plat First Nation and Biigtigong Nishnaabeg as partners to provide opportunities for research projects related, but not limited, to fisheries and medicinal plants. Ontario Parks will provide notification and opportunities for Pays Plat First Nation and Biigtigong Nishnaabeg to partner in cultural resource management and research as it applies to the Slate Islands Provincial Park.

Approved research activities and facilities will be compatible with protection values and/or recreational uses in the park. Sites altered by research activities will be rehabilitated as closely as possible to their previous condition.

Collecting

As a destination for scientists and people interested in geology, the Slate Islands are vulnerable to the collection of mineral specimens, and rock samples. As per PPCRA Ontario Regulation 347/07 no person shall remove, damage or deface any property of the Crown in a provincial park.

Education

Provincial parks have a role in supporting the education objective in the PPCRA. The manner in which that objective is met will vary for each park, and may be adapted based on the park’s resources and the MNRF direction and priorities at the time.

Ontario Parks will work with other organizations (surrounding First Nations, NMCA and Terrace Bay) to develop and deliver educational materials for park visitors relating to species at risk, sensitive features and the cultural values of Slate Islands Provincial Park.

11.12 Commercial tourism operations

Slate Islands Provincial Park is located in the North of Superior Travel Area, which spans northwestern Ontario from Wawa to Upsala, and is contained within the larger northwestern Ontario Tourism Region.

Ontario Parks will continue to support the existing tourism-based economic activity which benefits the local and regional economies. The provision of sea kayaking guiding and outfitting services from bases outside of Slate Islands Provincial Park may occur, consistent with the park goal and objectives.

The establishment and use of commercial outpost camps within the park is prohibited.

The park will not develop infrastructure to accommodate stopover day-visits by large groups such as cruise ships; Ontario Parks staff will direct queries from cruise ship operators and large groups to locations outside of the park with appropriate infrastructure such as docking and washroom facilities.

Aircraft landing (commercial)

Traditionally, commercial and private aircraft have provided minimal access to the Slate Islands for the purposes of sight-seeing, fishing and camping.

All commercial aircraft landing in the park require prior authorization from the park superintendent through a valid aircraft landing permit. Ontario Parks may place temporal restrictions on the use of the use of commercial aircraft to access the Slate Islands during caribou calving (May to early June) and nursery (June).

Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC-AIM, TP 14371), under section 1.14.5 of the Rules of the Air and Air Traffic Services states, “To preserve the natural environment of parks, reserves and refuges and to minimize the disturbance to the natural habitat, overflights should not be conducted below 2,000 feet above ground level.”

Powerboat use (commercial) [includes boat caches]

Local charter boats provide shuttle service to kayakers, as well as access to the Slate Islands for day-use fishing and sightseeing. Commercial shuttle operators will be directed to disembark kayaking parties at the A-4 zone. Ontario Parks may allow outfitters to cache kayaks in the A-4 zone, and will consider establishing kayak storage racks in this zone for their use from June-August.

11.13 Recreation and travel

Only low impact recreational activities which enable visitors to appreciate the park’s natural values in a safe and sustainable manner will be encouraged.

“Leave-no-trace” backcountry ethics and techniques will be promoted to park visitors through information, education and monitoring. Regulations pertaining to litter will be enforced. Unauthorized dumping is prohibited.

Aircraft landing - private

All private aircraft landing in the park require prior authorization from the park superintendent through a valid aircraft landing permit. Ontario Parks may place temporal restrictions on the use of the use of private aircraft to access the Slate Islands during caribou calving (May to early June) and nursery (June).

Powerboating, Sailing and Safe Harbour - private

Navigation is a federal jurisdiction that cannot be affected by provincial regulation and mooring is a right of navigation under both provincial and federal law. The Slate Islands provide safe harbour within park waters offering shelter to any craft from the open waters of Lake Superior. Motorized watercraft and sailboats are permitted and boaters are permitted to moor at any location within the inner waters of the Slate Islands.

All-terrain vehicle (ATV) travel

Recreational motorized vehicle use, including ATVs, is prohibited. No ATV trails will be developed.

Snowmobiling

Recreational use of snowmobiles is not permitted. Ice rarely forms an ice bridge between the mainland and the Slate Islands.

Mountain biking

Mountain biking is prohibited.

Hiking

There are some short informal trails associated with some of the camping areas as well as innumerable wildlife trails created by caribou. There is a trail on federal land at Sunday Point that leads from the old lighthouse keeper’s house to the lighthouse. There are no existing authorized trails. No new interior trails will be developed; bushwhacking/off trail hiking in the interior of Mortimer and Patterson Islands will be discouraged through visitor education about the impacts of this activity to caribou.

Geocaching

Geocaching is an outdoor activity using a global positioning system (GPS) receiver to find a predetermined location or “cache”. Caches are either “physical” or “virtual.” A physical cache is a container holding a log book and small rewards (e.g., key chains, pins, coins, etc.) which is placed at a specified location for the participant to find. A virtual cache relates to an existing object or specific location (e.g., an obvious landmark or structure). The reward for virtual caches is in confirming the location itself.

Physical caches are prohibited. Virtual geocaches may be permitted on a case-by-case basis by the park superintendent subject to Ontario Parks’ policy and procedures.

Rock climbing

Rock climbing is not permitted.

Scuba diving and skin diving