Slender Bush Clover Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the Slender Bush Clover, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage at: www.ontario.ca/speciesatrisk

Recommended citation

Jones, J. 2013. Recovery Strategy for the Slender Bush-clover ( Lespedeza virginica ) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 26 pp.

Cover illustration: Slender Bush-clover at Ojibway Prairie by Karen Cedar.

This photo may not be reproduced separately from this recovery strategy without permission of the photographer.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2013

ISBN 978-4606-3063-1(PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007, n'est disponible qu'en Anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec Pamela Wesley au ministère des Richesses naturelles au 705-755-5217.

Authors

Judith Jones, Winter Spider Eco-Consulting, Sheguiandah, Ontario

Acknowledgments

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada is thanked for providing information from the 6-month interim 2012 status report. Thanks to Sam Brinker and Mike Oldham for providing additional information on habitat; to P. Allen Woodliffe for the photo in Figure 1 and for information from past field work; to Paul Pratt for providing data from the Ojibway Nature Centre; and to Karen Cedar of the Ojibway Nature Centre for providing the cover photo.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Slender Bush-clover was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

Slender Bush-clover (Lespedeza virginica) is listed as endangered under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007 and on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act . It is a perennial herb in the Pea Family with pink flowers and many narrow leaves crowded on upright stems. The seeds can remain viable for decades and can pass unharmed through the gut of an animal.

In Canada, Slender Bush-clover is present only in Ojibway Park and possibly at Tallgrass Heritage Park and Black Oak Heritage Park, all part of the Ojibway Prairie Complex in the City of Windsor, Ontario. Collectively, these three sites comprise a single population. The species has not been seen at Tallgrass Park since 1997 or at Black Oak Park since 1993. It is unknown whether the seed bank is still viable at these locations. Plants growing above ground were seen at Ojibway Park in 2011.

In Ontario, Slender Bush-clover is extremely limited by a lack of suitable habitat. In this province, the species is restricted to dry-mesic tallgrass prairie relicts with patches of exposed sandy soil. It requires full sun and open ground and does not tolerate dense shade or competition from surrounding vegetation. Some type of disturbance is needed to create open soil. Historically, this was probably fire or periodic drought. Existing habitat is highly fragmented into small patches that are isolated from one another by distances of hundreds of metres or more. Disturbance factors are also needed to disrupt the seed coat to improve germination.

Slender Bush-clover may be limited by some aspects of its reproductive biology. First, the relatively short growing season in Ontario might cause lower seed productivity than is found in populations in the southern part of the species' range. Second, factors responsible for breaking seed dormancy (such as fire, abrasion by sand, ingestion by herbivores) might be lacking at extant sites. Finally, the small, isolated Canadian population of Slender Bush-clover is at risk of being destroyed by a single stochastic event, such as a flood or wind storm.

The most serious threat to Slender Bush-clover is alteration of the natural disturbance regime (e.g., suppression of natural wildfire), which allows natural succession to proceed, resulting in habitat degradation or loss. Invasive species are another threat in need of urgent attention. All-terrain vehicle and dirt bike use are no longer threats.

The recovery goal is to maintain the abundance and distribution of growing plants of Slender Bush-clover at Ojibway Park at current or greater levels by reducing threats, and if the species is extant in the seed bank at the other two subpopulations, to increase the number of growing plants present there to pre-1995 levels. The protection and recovery objectives are to:

- maintain or improve habitat suitability at the three existing sites;

- reduce presence of invasive species at the three existing sites;

- fill knowledge gaps; and

- increase population size and extent if deemed feasible.

It is recommended that a habitat regulation cover all three Windsor sites and that at Ojibway Park the entire opening where the species occurs plus a protective zone of 50 m around the outside of the opening be prescribed. A definition of "opening" is given in the body of the text. At Tallgrass and Black Oak Heritage Parks it is recommended that a 50 m zone around the former area of live plants be prescribed as habitat to protect the seed bank and allow disturbance to occur even though live plants have not been seen in recent years. It is recommended that the Tallgrass and Black Oak sites be prescribed for 50 years unless live, growing plants of Slender Bush-clover re-emerge in which case habitat would remain prescribed beyond this time. It is recommended that restoration populations be regulated if they are planted within the three parks where the species is endangered and in natural vegetation but not in garden beds.

1.0 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Slender Bush-clover

Scientific name: Lespedeza virginica

SARO list classification: Endangered (within Tallgrass Prairie Heritage Park, Ojibway Park and Black Oak Heritage Park in the City of Windsor)

SARO list history: Endangered (2008), Endangered – Regulated (2004)

COSEWIC assessment history: Endangered (2000, 1986)

SARA Schedule 1: Endangered

Conservation status rankings:

GRANK: G5 NRANK: N1 SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above and for other technical terms in this recovery strategy.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Slender Bush-clover (Lespedeza virginica (L.) Britton) is a perennial herb in the Legume or Pea Family (Fabaceae). The upright hairy stems, 30 to 100 cm tall, arise from a woody rhizome and sometimes branch near the top. Numerous narrow, three-parted leaves that are strongly ascending (pointing up) grow from the main stem on short (1 cm) stalks, giving the stem a crowded, spike-like profile In late summer, small, purple to pink pea-like flowers, 4 to 7 mm across, are produced in short clusters in the axils of the leaves (Figure 1). Two types of flowers are produced: those that open and have showy petals, and those that are smaller, remain closed, and are self-fertile. Following pollination, a flat, oval-shaped pod 4-7 mm in diameter containing one seed is produced from both types of flowers (Clewell 1966, Gleason and Cronquist 1991).

Slender Bush-clover may be distinguished from other species of Bush-clover that have upright stems and purple-coloured petals by the following characteristics:

- narrow, strap-shaped leaves (not oval shaped);

- leaves somewhat hairy (but not densely velvety);

- numerous, non-opening flowers present (more than just a few present), and

- flowers with open corollas on short stalks or sitting directly on the stem (not on stalks nearly the length of leaves).

Figure 1. Flowering clusters of Slender Bush-clover showing both the showy and the non-opening flowers. (Photo: P.A. Woodliffe. This photo may not be reproduced separately from this document without permission of the photographer.)

Species biology

Slender Bush-clover is a perennial that comes up each year from underground woody rhizomes. Clewell (1964) counted the annual growth rings on rhizomes of Hairy Bush- clover (L. hirta) and Wand-like Bush-clover (L. intermedia) in southern Indiana and found plants lived up to 13 to 17 years, which may give an indication of the potential life span of the growing plants of Slender Bush-clover as well. Like other plants in the Legume family, Slender Bush-clover has nitrogen-fixing bacteria in nodules on the rhizome (Yao et al. 2002). This symbiotic association enables Slender Bush-clover to grow in nitrogen-poor soils.

In Ontario, Slender Bush-clover flowers in August and September and produces both open (chastogamous) flowers and closed (cleistogamous) flowers that self-pollinate. Both kinds of flowers produce viable seed. The ratio of the different flower types produced may change in response to different environmental conditions or stresses (Clewell 1964, Schutzenhofer 2007). More closed flowers are produced when plants are stressed. These flowers have smaller petals and no nectar and require less energy to produce. Thus, they may be a smaller energy investment that guarantees reproduction when conditions are less than optimal.

The open flowers of Slender Bush-clover are likely pollinated by a variety of insect species, with bees, butterflies, and moths probably being the main pollinators (Pratt 1986). Clewell (1966) observed honeybees and several types of bumblebees on bush- clovers in Indiana. Simpson (1999) removed competing species in plots to see if Slender Bush-clover was limited by pollination. In the first year, she found an increase in insect visits but no increase in seed-set and concluded that pollination was already above a threshold level for seed set. In the second year, she found a stronger correlation between insect visits and amount of seed set because overall visitation was low. This suggests that Slender Bush-clover can be limited by pollination depending on conditions for pollinators in any given year.

Both the showy and non-opening flowers of Slender Bush-clover produce viable seeds. However, seeds of non-opening flowers have slightly lower viability (Schutzenhofer 2007). Schutzenhofer (2007) examined the effects of herbivory on the production of both types of flowers and found that herbivory resulted in an increase in the ratio of non- opening flowers over showy flowers. Since seeds of non-opening flowers have lower viability, this change in ratio may have consequences for overall reproductive success. No significant difference was found in germination rates between seeds produced from showy flowers and those of non-opening flowers, but rates for both types of seeds were low. No analysis has been done that would take into consideration any benefit provided if herbivory results in increased seed dispersal distances or improved seed germination rates. It can be speculated that the amount of herbivory within a patch, as well as the parts of the plant eaten, may make a difference.

The seeds of Slender Bush-clover have a hard, impervious seed coat that permits them to pass unharmed through animal digestive systems and to remain viable in the soil for long periods of time. The seed coat must be scarified or disrupted in some way before germination can occur. Passage through an animal gut may improve germination for seeds of Slender Bush-clover. Blocksome (2006) found improved germination rates for seeds of Chinese Bush-clover (L. juncea var. sericea) after passage through the gut of quail. Clewell (1966) reported a 100% germination rate for seeds of Slender Bush- clover manually scarified with a scalpel versus 0% for seed that was not scarified. As well, Clewell (1966) successfully germinated seeds taken from a 54-year-old herbarium specimen, showing that under some conditions seeds may remain viable for many decades. The actual time that Slender Bush-clover seeds can remain viable outdoors in soil is unknown. If seeds do not pass through an animal gut, some other natural process may be needed to disrupt the seed coat. It can be speculated that fire or possibly abrasion by sand may provide this function.

At the Ontario location for Slender Bush-clover, in the Ojibway Prairie Complex in the City of Windsor, a number of animals and birds are present that may eat the seeds of Slender Bush-clover, including White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), Northern Bobwhite (Colinus virginianus), Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) and Mourning Dove (Zenaida macroura), as well as many small mammals such as mice and rats (Pratt 1986, Blocksome 2006, Ojibway Nature Centre 2012). The seed of Slender Bush- clover may be dispersed by animals if eaten and expelled in feces at another location. It is not known whether animals are the main dispersal vector of Slender Bush-clover, but some other species of bush-clovers are dispersed primarily by animals (Blocksome 2006).

The likelihood of the seed of Slender Bush-clover passing through the gut rather than being broken down during digestion is not known, but it is possible that an animal may be both a seed predator and an occasional dispersal vector. There may be a trade-off between having a seed that is an attractive food source to animal vectors and losing some seed to animal digestion. If not eaten, the fruits of Slender Bush-clover stay on the plant through the fall and winter, eventually falling and opening to release the seed (Clewell 1966).

Several ecological processes must occur for successful germination. These include suitable disturbance to expose mineral soils (ground fires, scraping, etc.) and actions that scarify or disrupt the seed coat (fire, passage through an animal gut, being rubbed by sand, etc.) as well as suitable moisture conditions. In controlled garden trials in Indiana, Clewell (1966) found plants of Hairy and Wand-like Bush-clover were able to reach maturity and bear seed in the first year after germination, but found seedlings in natural populations either didn't flower in the first year or flowered but produced few seeds. It is unknown whether flowering in the first year is possible for Slender Bush- clover in Ontario. The species also is able to spread from short, underground stolons or from fragments of the woody rhizome (Clewell 1964). The presence of underground woody rhizomes, a hard seed coat, and the ability to spread from fragments are adaptations that allow Slender Bush-clover to survive the fire or other disturbance that is required to create and maintain suitable habitat.

Slender Bush-clover appears to be a poor competitor and grows best when not crowded by other vegetation. In a study of several species of bush-clover growing on both eroded and non-eroded soils, Slender Bush-clover grew taller and had increased yield (dried biomass), increased winter survival and greater survival of seedlings in plots that were weeded to reduce competition regardless of soil type (Harris and Drew 1943).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

In Canada, Slender Bush-clover has been documented only in southwestern Ontario (Figure 2). In the United States, Slender Bush-clover is found in 26 states, and in northern Mexico it is present in the state of Nuevo Leon. Table 1 shows the state or provincial conservation rankings (S ranks) for Slender Bush-clover (NatureServe 2012). The species is not considered rare within the core of its Midwestern range but is ranked rare in northern areas. In addition, Slender Bush-clover is legally listed as threatened in New Hampshire and Wisconsin. Globally, the species is considered secure and ranked G5 (NatureServe 2012).

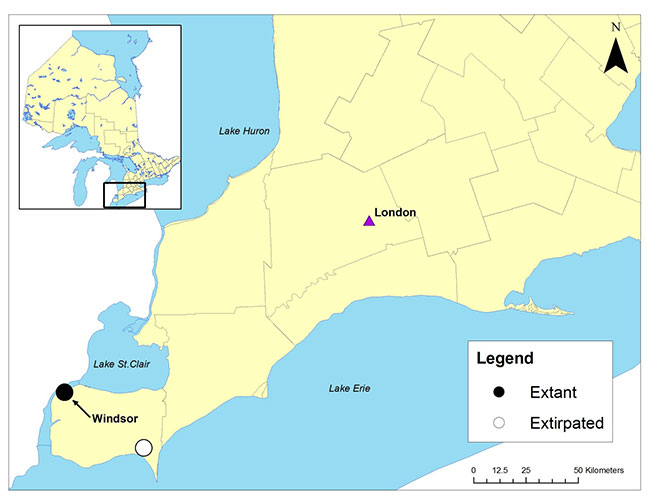

Figure 2. Historical and current distribution of Slender Bush-clover in Ontario

Enlarge Figure 2. Historical and current distribution of Slender Bush-clover in Ontario.

Solid circle: extant population consisting of three subpopulations in the Ojibway Prairie Complex in the City of Windsor. Open circle: historical record from the Leamington area not seen since 1892.

Table 1. Conservation ranking for Slender Bush-clover by state or province (NatureServe 2012)

| State or Provincial Conservation Rank | States with this rank |

|---|---|

| Critically imperilled (S1) | New Hampshire, Ontario |

| Imperilled (S2) | Wisconsin |

| Possibly vulnerable (S3?) | New York |

| Apparently secure (S4) | Iowa, Virginia, West Virginia |

| Secure (S5) | Delaware, Kentucky, New Jersey, North Carolina |

| Not ranked (SNR) | Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas; Mexico: Nuevo Leon |

In Ontario, Slender Bush-clover is present only in the Ojibway Prairie Complex in the City of Windsor. In that area, the species has been documented from three sites, Tallgrass Heritage Park, Black Oak Heritage Park, and Ojibway Park, all of which qualify as subpopulations of a single population or occurrence according to the criteria used by the Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC 2012).

The species was first discovered at Tallgrass Heritage Park in 1977. Plants were observed there in 1978, 1979, 1982, 1984 and 1997 but were not found in 2000 or 2011 (NHIC 2012). Abundance was not documented except in 1984 when approximately 150 plants were reported. In 2000, the site was reported to be too shaded-in and dense with understory vegetation (NHIC 2012), and the loss of the Slender Bush-clover plants at this site has been attributed to natural succession (COSEWIC 2012a).

In 1993, a single Slender Bush-clover plant was observed in Black Oak Heritage Park along a walking trail. The site was visited in 1997 and 2011 but the species was not found and may have been destroyed by all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) (COSEWIC 2000, COSEWIC 2012a).

In 1979, Slender Bush-clover was discovered at Ojibway Park. The plants were not found in 1984 for the first COSEWIC status report (Pratt 1986) but were observed and documented in 1986, 1997, 2000 and 2011 (COSEWIC 2000, NHIC 2012). Abundance of Slender Bush-clover at this site is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Abundance of Slender Bush-clover at the Ojibway Park site (NHIC 2012)

| Date | Abundance | Observers |

|---|---|---|

| 1979 | ~50 plants | P.D. Pratt |

| 1984 | 0 | P.D. Pratt |

| 1986 | "a few" | M.J. Oldham |

| 1997 | 160 | K. Cedar |

| 2000 | >24 | D. Jacobs, P.D. Pratt, P.A. Woodliffe & K. Cedar |

| 2011 | 165 | S.R. Brinker, M.J. Oldham, C.D. Jones |

Due to Slender Bush-clover’s long-lived seed viability, it is possible the species may be extant in the seed bank and could potentially reoccur at any of the three sites in the Ojibway Prairie Complex even though live plants of Slender Bush-clover have only been seen in recent years at the Ojibway Park site. Therefore, all three sites must still be considered extant locations.

Only generalized conclusions can be made about population trends because the populations have not been consistently observed, but overall there appears to be a decline in population size in the last 25 years. The loss of the plants at the Tallgrass Heritage Park site, from 150 plants in 1984 to 8 plants in 1997 to 0 in 2011, likely due to succession (COSEWIC 2000), is certainly a decline. The loss of the plants at Black Oak Heritage Park, probably from ATVs, is another decline. At the Ojibway Park site, the data show many fluctuations and an overall slight increase from the previous high of 160 in 1997 to 165 in 2011 (NHIC 2012). However, generally, the trend in the last 25 years in Ontario appears to be one of decline and possibly the loss of sites.

Historically, Slender Bush-clover was also present in the Leamington area, where it was collected by Macoun in 1892 (NHIC 2012). However, the population there has never been relocated despite many focused searches. The area is now heavily urbanized or converted to agriculture (Pratt 1986). In addition, there is a historical report of Slender Bush-clover from the Niagara Region made by W. Scott in 1896; however, the report is not backed up by a collected specimen and the record is considered likely an error (COSEWIC 2000).

1.4 Habitat needs

In Canada, Slender Bush-clover is restricted to dry-mesic tallgrass prairie relicts with patches of exposed sandy soil. In 2011, the Ontario habitat was reported to be sandy openings in oak woods with Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Crown Vetch (Securigera varia), Black Oak (Quercus velutina), Canadian Tick-Trefoil (Desmodium canadense), Feather Three-awn (Aristida purpurascens), Dense Blazing Star ( Liatris spicata), and Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe) (NHIC 2012). The Ecological Land Classification (Tabb) vegetation type (Lee et al. 1998) of the current Ontario location is described as Dry Black Oak Tallgrass Savannah (TPS1-1) (P.A. Woodliffe, pers. comm. 2012) or possibly Dry Black Oak Tallgrass Woodland (TPW 1-1) at the sites where vegetation cover has increased and closed in most of the open area. As the species occupies the open patches within these vegetation community types, it can be assumed that Dry Tallgrass Prairie (TPO1-1) would also provide suitable habitat. The species requires full sun and open ground for establishment of seedlings and does not appear to be able to grow in dense shade or withstand even moderate levels of competition from surrounding vegetation (Pratt 1986, COSEWIC 2000). The opening at Ojibway Park where the species currently occurs is approximately .33 ha.

The requirement for open soil indicates that some type of disturbance (such as fire, periodic drought or anthropogenic disturbance) is needed for maintenance of suitable habitat conditions. Without it, the open ground would be expected to become covered with thatch from a build-up of leaves and organic materials and to fill in with vegetation from natural succession, becoming unsuitable for Slender Bush-clover.

Historically, bare ground probably resulted from fire but now likely comes mainly from other types of disturbance. Pratt (1986) reports that at the Tallgrass Heritage Park site, Slender Bush- clover plants were located in an area where the ground was scraped. He adds that 1948 air photos show an open trail a few metres east of where the plants were located, so the trail may also have previously provided some disturbance. However, he also reports that spring fires burned through the area in 1978, 1980 and 1983 and occurred within 100 m of the population in 1976, 1977 and 1984, so it is possible that fire helped maintain the openness of the area during the time that the habitat remained suitable.

The frequency at which disturbance is required, or the time period over which the habitat may become too heavily vegetated to be suitable, is unknown. According to Pratt (1986), the scrape at Tallgrass Heritage Park probably dated from around 1958, and was therefore roughly 26 years old in 1986. Between 1975 and 1986, Pratt observed little apparent change in the site, indicating a very slow rate of succession, especially in the centre of the scraped area, during that nine-year period. This was also a period in which fire and human disturbance were occurring sporadically. By 1997, there was almost no open mineral soil present (COSEWIC 2000) and only eight Slender Bush-clover plants were found. Thus, it appears the habitat became significantly degraded in the 13 years between 1984 and 1997. It can be speculated that fire or disturbance may be needed every 3 to 13 years, and probably closer to the more frequent end of that range since plants had nearly disappeared after 13 years.

Optimal habitat for Slender Bush-clover contains a specific association of prairie forbs (Pratt 1986), but species composition in the habitat has probably changed somewhat in the last 25 years, possibly indicating an overall degradation. Pratt (1986) listed 12 species frequently associated with Slender Bush-clover and 12 rare species (based on Argus and White 1977, 1982 and 1983, and Argus and Keddy 1984) that were found within 1 m of Slender Bush-clover. Of these, only two of the former frequent associates and only three of the former rare species were present in 2011 (COSEWIC 2012a). Still, it is possible that some of this difference may be due to the reduction in the number of sites as well. COSEWIC (2012a) listed 34 plant species growing within 1 m of Slender Bush-clover during fieldwork in September of 2011. Most are prairie-obligates or species of old fields. One of these, Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata) is federally and provincially listed as Threatened, and three are listed as rare in Ontario: Arrow Feather Three-awn (Aristida purpurascens – S1), Tall Coreopsis ( Coreopsis tripteris —S2), and Round- fruited Panic Grass (Dicanthelium sphaerocarpon—S3) (COSEWIC 2012b, NHIC 2012).

In Michigan, Slender Bush-clover is found in 17 counties in habitats that include dry open woods (especially oak), prairies, shores, fields, railroad banks and open hills (Voss 1985, Reznicek et al. 2011). It is unknown why the species occurs in more locations and in a wider range of habitats in Michigan than in Ontario. Throughout its global range, the species is not restricted to sandy soils, and in some states the species is found at latitudes more northerly than Windsor.

1.5 Limiting factors

In Ontario, Slender Bush-clover is extremely limited by a lack of suitable habitat. Of the hundreds of square kilometres of tallgrass prairie and savannah documented in early settlement times, only about 2100 ha or 0.5% remains, with the majority lost to agricultural use and residential development (Bakowsky and Riley 1994). Today, apart from the Ojibway Prairie Complex and areas on Walpole Island, most remnant patches are small (less than 2 ha) and isolated. Natural ecological processes, such as the occurrence of wildfire, are severely compromised in such small patches.

Suitable prairie habitat for Slender Bush-clover is highly fragmented into small patches that are isolated from one another by distances of hundreds of metres or more. This probably limits the ability of Slender Bush-clover to expand into new areas (COSEWIC 2000). Mature fruiting plants of Slender Bush-clover produce only a few hundred seeds, which may reduce the reproductive capacity of the species (COSEWIC 2000). In addition, these seeds require scarification before they can germinate and the natural factors which historically may have provided this process (such as fire, specific types of animal vectors, etc.) may now be uncommon or no longer occur. Low reproductive capacity is not an inherent limitation in the genus since some species of bush-clovers, such as Silky Bush-clover (Lespedeza cuneata) are invasive on rangeland (Blocksome 2006).

It is possible that the climate of Ontario, the northern part of the species range, may be a limitation to Slender Bush-clover. The species flowers at the end of the summer and must set seed before the end of the growing season. This time frame is shorter in Ontario than it is in the core of the species' range in the central Midwest, and probably occasionally results in low or lost seed set in years when there is early frost or snowfall. Finally, the population of Slender Bush-clover in Canada is very small and isolated and thus at risk of being destroyed by a single stochastic event, such as a flood or wind storm. A severe storm wiped out a population that had been planted in Lambton County as part of an experimental restoration (R. Ludolph, pers. comm. 2012). A single event could remove the entire population, especially since the live plants currently occupy an area of only 9 by 4 m (COSEWIC 2012a).

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Observed threats

Altered disturbance regime

The most serious current threat to Slender Bush-clover is degradation or loss of habitat from fire suppression or other changes to the natural disturbance regime. Without disturbance of some type, natural succession takes place and open areas fill in with vegetation, covering up the open ground required for germination and growth. Slender Bush-clover does not compete well with surrounding vegetation, so the increased cover of other plants is a serious detriment that can ultimately lead to a complete decline and loss of the population. Degradation of habitat continues to be an active threat despite all three locations for the species being in protected, managed parks. The filling in of vegetation is likely the main factor responsible for the lack of growing plants and possible loss of the Tallgrass Heritage Park population (COSEWIC 2012a).

Periodic burning is conducted within the Ojibway Prairie Complex and all three sites for Slender Bush-clover have been burned occasionally in the past with enough intensity to remove leaf litter and blacken soil. However, the frequency of burns has been low in Ojibway Park and Tallgrass Prairie Heritage Park (P.D. Pratt, pers. comm. 2012). Whether due to low intensity, low frequency or a combination, it appears that the burning done was insufficient to maintain the habitat at the Tallgrass and Black Oak Park sites. Lack of fire or other disturbance contributes to habitat loss by allowing a build-up of leaves and organic materials (dead plants and grass) to cover patches of exposed soil.

Invasive species

Crown Vetch (Securigera varia), Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) and Spotted Knapweed (Centaurea stoebe ssp. micranthos) are present within 1 m of Slender Bush- clover plants (COSEWIC 2012a). These non-native species have the capacity to spread quickly, take over open ground and eliminate most other surrounding plant species. None of these species is mentioned by Pratt (1986) or COSEWIC (2000), indicating that their presence is a recent occurrence.

Crown Vetch forms a low ground cover that carpets open sand. Because it spreads quickly and has tenacious roots, it is frequently planted in highway construction projects to prevent erosion. According to COSEWIC (2012a), in 2011 this species had already succeeded in covering up most of the open sand patches in the small prairie remnant where Slender Bush-clover is found. Spotted Knapweed is known to be highly invasive due to its allelopathic effects (secreting toxins from its roots into the soil). It was listed as rare in the vicinity of the Slender Bush-clover plants. Autumn Olive is a fast-growing woody species that is present in the habitat. It has the capacity to grow tall and shade out shorter plants.

Historical threats

In the past, ATV and dirt bike use occurred near the Canadian Slender Bush-clover subpopulations (Pratt 1986). All-terrain vehicle use can be a threat if it damages or breaks plants and causes rutting and displacement of soil. However, disturbance from ATVs probably also contributed to maintaining the exposed ground the species requires. All terrain vehicles and dirt bikes are no longer permitted in the protected parks where Slender Bush-clover occurs. This has eliminated the threat of damage to Slender Bush-clover plants but it has also removed a factor that helped to maintain suitable habitat in the absence of natural disturbance. Reinstating ATV use is certainly not recommended, but the issue is mentioned here to show that light levels of some types of human disturbance may be beneficial, although striking the correct balance where no harm is done may be difficult.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Whether Slender Bush-clover is still present and viable in the seed bank at Tallgrass and Black Oak Heritage Parks is a knowledge gap that must be filled in order to know if these two sites (where live Slender Bush-clover plants have not been seen recently) still require recovery efforts. In addition, the processes needed to allow Slender Bush- clover plants to be successfully re-established from the seed bank are not known. Research to fill these gaps generally requires taking soil cores and germinating all seeds present in a controlled environment.

Many other knowledge gaps need to be filled to guide recovery for the Ojibway Park occurrence and possibly for the other two sites. These include limited understanding of:

- the viability of the occurrence;

- the frequency and intensity of burning that could be beneficial for habitat maintenance and improvement;

- productivity (i.e., amount of seed set and effects of weather);

- seed viability and germination rates;

- genetic uniqueness and possible effects of inbreeding;

- availability of pollinators and degree of reliance on self-fertilization versus cross- pollination;

- current rates and distances of seed dispersal and availability of animal vectors and

- the severity of the threat from invasive species as well as the mechanism of the threat (e.g., shading, competing for pollinators, allelopathy, etc.).

The location and health of any transplanted occurrences would also be useful to know to assist with potential future restorations.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

All subpopulations of Slender Bush-clover are within parks that are managed by the City of Windsor. No motorized vehicles are allowed, so the threat of damaged or broken plants and habitat degradation from ATVs and dirt bikes has been eliminated. In addition, controlled burning is done in Ojibway Park, Tallgrass Prairie Heritage Park, Ojibway Prairie Provincial Nature Reserve, and Spring Garden Natural Area, although the frequency and intensity of burning in Slender Bush-clover habitat probably needs to be adjusted to ensure burning actually contributes to the on-going maintenance of suitable habitat and possibly provides new areas for colonization. Invasive Crown Vetch and Autumn Olive have been removed periodically by hand at the Ojibway Park Slender Bush-clover site (P.D. Pratt, pers. comm. 2012).

In 2005, the Tallgrass Recovery Team produced the draft National Recovery Strategy for Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario and Associated Species at Risk (Ambrose and Waldron 2005). The overall goal of the plan was to recover, reconstruct, and conserve a representative network of tallgrass communities, along with the full complement of plant and animal species that inhabit these diverse ecological communities. This strategy covered 138 plant species and 45 animal species that are rare or at risk, all of which are restricted to or associated with tallgrass ecosystems. Slender Bush-clover is one of these species. While most recovery efforts have since shifted to working on species individually, this plan brought a lot of attention to the benefits of recovering the ecosystem as a whole in order to improve the situation for many species together. There are still several multi-species recovery plans being developed and implemented from this group of species.

From 1985 to at least the mid-1990s, Slender Bush-clover was grown in gardens at the Ojibway Nature Centre using seeds from the Tallgrass Park site (COSEWIC 2000, R. Ludolph, pers. comm. 2012). The plants were planted out by the Rural Lambton Stewardship Network as part of restoration work in the historical range of tallgrass prairie. However, the main location where plants were successfully growing was destroyed in a storm and information on any other locations has been lost. The species is reportedly easy to grow and is good for attracting wildlife (R. Ludolph, pers. comm. 2012). A few plants still survive in the garden at the nature centre (P.D. Pratt, pers. comm. 2012).

The Ojibway Prairie Complex, which consists of several parks, has been well studied and botanized, so the area is well known and has been searched intensively without finding additional sites for Slender Bush-clover. Furthermore, many other Ontario prairie sites have also been well studied and searched for species at risk, and Slender Bush-clover has not been found. This includes Walpole Island (Walpole Island Heritage Centre 2006). The species also has not been found during new field work in the corridor of the Detroit River International Crossing (Canada-U.S.-Ontario-Michigan Border Transportation Partnership 2009), in which several new populations of other species at risk have been discovered (G.E. Waldron, pers. comm. 2010, P.A. Woodliffe, pers. comm. 2010). Thus, it is rather unlikely that additional populations of Slender Bush-clover will be found.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

The recovery goal is to maintain the abundance and distribution of growing plants of Slender Bush-clover at Ojibway Park at current or greater levels by reducing threats, and if the species is extant in the seed bank at the other two subpopulations, to increase the number of growing plants present there to pre-1995 levels.

Rationale for fecovery goal

First, two of three known subpopulations of Slender Bush-clover appear to have been lost to habitat degradation. Therefore, recovery must focus on maintaining the last remaining location where live, growing plants of the species are present. Second, the known historical distribution of Slender Bush-clover in Canada includes only the

Ojibway Prairie Complex in Windsor and a site near Leamington where the species has not been seen since 1892. Therefore, recovery will focus on maintaining the current distribution in the Ojibway Prairie Complex. Finally, whether there is a viable seed bank of Slender Bush-clover has to be determined before recovery can be considered for Tallgrass and Black Oak Heritage Parks. Given the small population size and extremely limited distribution, it is unlikely that recovery will ever result in downlisting of this species. Still, halting habitat loss may result in stable or even somewhat expanded populations which might require less attention to ensure their persistence.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

To meet the recovery goal, the protection and recovery objectives for Slender Bush- clover are as follows:

Table 3. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Maintain or improve habitat suitability at the three existing sites. |

| 2 | Reduce presence of invasive species at the three existing sites. |

| 3 | Fill knowledge gaps. |

| 4 | Increase population size and extent if deemed feasible. |

Note that the knowledge gap regarding the seed bank must be filled (Objective 3) before it will be known if Objectives 1, 2, and 4 should be applied to the Tallgrass and Black Oak Heritage Park sites.

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 4. Approaches to recovery of the Slender Bush-clover in Ontario

1. Maintain or improve habitat suitability at the three existing sites

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Management and Stewardship | 1.1 Assess type of habitat improvement actions that are needed and appropriate for each of the three sites. These may include burning, cutting back vegetation, scraping, raking or other actions. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Management and Stewardship | 1.2 Assess potential positive or negative impacts on other rare species present in the same habitat from habitat improvement actions for Slender Bush- clover. |

|

| Critical | Ongoing | Management and Stewardship | 1.3 Plan and execute appropriate actions to improve habitat at each site. -- Search for partners and volunteers to help with labour. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring and Assessment | 1.4 Monitor results of 1.3. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Management and stewardship | 1.5 Based on 1.4, plan next actions. Consider frequency and intensity at which action is required. |

|

2. Reduce presence of invasive species at the three existing sites

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Management and Stewardship | 2.1 Assess best method to reduce presence of the invasive species for each of the three sites. Consult current literature for best management practices. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Management and Stewardship | 2.2 Assess potential positive or negative impacts of invasive species removal on other rare species present in the same habitat. |

|

| Critical | Short-term | Management and Stewardship | 2.3 Plan and execute appropriate actions to reduce invasive species presence. -- Search for partners and volunteers to help with labour. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Monitoring and Assessment | 2.4 Monitor effects of 2.3. |

|

| Necessary | Ongoing | Management and Stewardship | 2.5 Based on 2.4, plan next actions. Consider frequency and intensity at which action is required. |

|

3. Fill knowledge gaps

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Ongoing | Research | 3.1 Plan and conduct research on seed bank of Slender Bush-clover. -- Search for partners to conduct research. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Research | 3.2 Plan and conduct research on other knowledge gaps as funding and partners become available. |

|

4. Increase population size and extent if deemed feasible

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Management | 4.1 Establish new populations as feasible to prevent extirpation of the species due to stochastic events and as a precaution in case of failure to manage current threats. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management | 4.2 Pending outcome of 1.4, conduct recovery actions to increase presence of Slender Bush-clover at all three sites. |

|

| Beneficial | Long-term | Management | 4.3 Pending outcome of 3.1, conduct recovery actions to increase presence of Slender Bush-clover from seed bank. |

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

All recovery actions for Slender Bush-clover need to be carefully assessed and planned before being carried out. This is to ensure that actions do not harm the existing small population of Slender Bush-clover or any of the other species at risk or rare species that are present in the same habitat.

However, most other species present would probably benefit from additional clearing and opening up of the habitat (P.D. Pratt, pers. comm. 2012, S.R. Brinker, pers. comm.2012), and staff at Ojibway Prairie are already taking care to protect fire-sensitive species at risk during burning (P.D. Pratt, pers. comm. 2012). However, best management practices (BMPs) for invasive-species control also need to be considered during recovery work to keep invasives from being favoured by habitat clearing. To prevent spreading the invasives, it is likely that several types of recovery actions would need to be done in combination (for example, burning followed by herbicide use, or clipping of shrubs followed by burning).

Although the Canadian population is very small, with recovery actions, the prognosis for Slender Bush-clover could be very positive. In Illinois, efforts to recover a similar species, Prairie Bush-clover (Lespedeza leptostachya —threatened in the U.S.), have included the use of fire, herbicide and grazing by bison to reduce competition from grasses and other plants. Preliminary analyses show these treatments have resulted in an increase in seedling production, an increase in number of individuals overall, and in plants that are more robust (P. Vitt, pers. comm. 2012, Chicago Botanic Garden 2012).

As a precaution, it would be beneficial to establish some plantings of Slender Bush- clover in locations separate from the current patch to ensure that the species is not extirpated in case of an accidental event, such as a storm. The few plants in the garden bed at the Ojibway Nature Centre could be augmented to ensure a stable garden population. Slender Bush-clover is listed on Schedule 1 of the ESA as endangered only within Olibway Park, Black Oak Heritage Park and Tallgrass Heritage Park, so the plants would not have legal protection elsewhere. Therefore, it might be advisable to establish an additional restoration population somewhere within one of these parks to ensure the plants would be protected. Relocation of the restoration sites where the species was planted in Lambton County would also be beneficial to see if any restored populations of Slender Bush-clover have survived.

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

In establishing the area to be prescribed as habitat in a regulation, several considerations need to be mentioned.

First, although seeds of Slender Bush-clover are known to remain viable for decades, it is unknown whether Slender Bush-clover is still viable in the seed bank at the Black Oak and Tallgrass Heritage Park sites. Therefore, it is recommended that all sites where Slender Bush-clover has been observed in the Ojibway Prairie Complex come under a habitat regulation even if no live plants are present, until this knowledge gap is filled or until a 50-year time limitation has passed (see #4 below).

Second, the habitat of Slender Bush-clover must have periodic disturbance in order to remain suitable. This disturbance may come from several different types of activities or processes including some types of human usage. Therefore, it is recommended that legal regulation and protection of habitat should not cause the exclusion of all human activities from the regulated area.

Third, the current habitat of Slender Bush-clover occurs within the recognizable ELC types, Dry Black Oak Tallgrass Savannah or Dry Black Oak Tallgrass Woodland. However, suitable habitat is only some small open patches within the savannah or woodland matrix, so the habitat required is much smaller than the entire ELC vegetation type polygon. Thus, ELC vegetation type is not a precise enough guide to prescribe habitat.

Finally, although dispersal habitat is an important consideration for recovery, for Slender Bush-clover it is not possible to base the size of the habitat to be prescribed on dispersal distances. Dispersal in animal or bird feces is unpredictable, and the distances covered by these vectors may be quite large, even on the order of kilometres.

Therefore, it is recommended that habitat be prescribed as follows:

- At Ojibway Park, where live Slender Bush-clover plants continue to be observed, it is recommended that the regulated habitat include the entire opening in which the plants occur, as well as a protective zone of 50 m around the outside of the open area, including any disturbed, human-made components such as scraped areas since light soil disturbance may be helpful to the species. Should any suitable openings extend beyond the 50 m, it is suggested that all of this open area also be prescribed. For this prescription, "open" or "opening" may be defined as the area in which total tree cover is less than 25 percent, with ground dominated (greater than 50%) by herbaceous plants, shrubs or exposed soil, and not shaded by trees. These criteria are consistent with the ELC characteristics of tallgrass prairie and cultural meadow (Lee et al. 1998). The boundaries of the opening at Ojibway Park would be the point at which tree cover becomes continuous and the ground too shaded. The exact boundary line of the Ojibway Park opening is probably best assessed and mapped in the field.

A distance of 50 m has been shown to provide a minimum critical function zone for the maintenance of microhabitat properties, such as light, temperature, litter moisture, vapor pressure deficit and humidity for rare plants. A study on micro-environmental gradients at habitat edges (Matlack 1993) and a study of forest edge effects (Fraver 1994) found that effects could be detected as far as 50 m into habitat fragments. Forman and Alexander (1998) and Forman et al. (2003) found that most roadside edge effects on plants resulting from construction and repeated traffic have their greatest impact within the first 30 m to 50 m. In addition, in the case of Slender Bush-clover, a 50 m protective zone may also provide additional area for seed dispersal by small animals.

- At the Tallgrass and Black Oak Heritage Park sites where live Slender Bush-clover plants have not been seen for some time, it is still possible that fire or other disturbance could create new habitat and allow new Slender Bush-clover plants to arise from the seed bank. Therefore, it is recommended that habitat be regulated at these sites in order to protect the seed bank and to allow suitable disturbance to occur. However, these sites are currently not open enough to use the characteristics listed in #1 to prescribe habitat, so other criteria are suggested.

At these sites, it is recommended that a zone of 50 m be drawn around the outside of the approximate former location of live Slender Bush-clover plants and that the resulting polygon be prescribed as habitat. The area inside this polygon is similar to the size of the habitat where the current live plants are present, which is the current known minimum patch size for suitable habitat for this species. As well, 50 m is recommended as a protective distance because if Slender Bush-clover is present in the seed bank, it may be important to maintain microhabitat conditions so that some future disturbance may be able to recreate suitable habitat and allow new plants of Slender Bush-clover to emerge.

-

Should any new populations of Slender Bush-clover be discovered or should new live plants emerge at Tallgrass or Black Oak Heritage Parks, it is recommended that the criteria of #1 should be applied to the new site.

-

Due to the long-lived nature of the seed, it is recommended that sites where Slender Bush-clover plants are no longer found be regulated for a period of 50 years unless live plants reappear (in which case habitat would be prescribed as per #1) or it can be shown that there is no viable seed bank. The time that Slender Bush-clover seeds can remain viable in the seed bank is an unknown, as is the natural periodicity of disturbance that would create new habitat, such as a stand-replacing forest fire. Furthermore, the area surrounding Black Oak and Tallgrass Heritage Parks is urban, so the possibility that a major forest fire would be allowed to burn unchecked is highly unlikely. Therefore, after a period of time, it can be assumed that new suitable habitat conditions are not going to be created, regardless of whether or not there is a viable seed bank. The period of 50 years should be given to allow ample time for recovery actions, such as habitat clearing and controlled burning, to be considered and undertaken

- Slender Bush-clover is legally listed as endangered within Ojibway, Tallgrass Heritage and Black Oak Heritage Parks. If any populations of Slender Bush-clover are planted for restoration within the parks where the species is endangered, it is recommended that they be protected by a habitat regulation, according to the criteria in #1 above. It is recommended that restoration populations in these three parks be regulated as long as they are within natural or semi-natural vegetation (e.g., not in garden beds). Populations planted elsewhere would not require regulation unless a change is made to the way the species is listed in ESA 2007.

Glossary

Ascending: Sloping or leading upwards. Describes leaves or other parts that point up.

Axil: The angle where a leaf joins the stem.

Chastogamous flower: A flower that opens to allow pollination by outside agents, such as insects or the wind.

Cleistogamous flower: A self-pollinating flower that sets seed without opening. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community to convey the degree of rarity at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Conservation status is ranked on a scale from 1 to 5 as follows:

- 1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Corolla: The petals of a flower, usually in a whorl around the reproductive organs. Ecological Land Classification: A system for evaluating different types of vegetation, such as Sugar Maple Deciduous Forest, Cattail Mineral Shallow Marsh, etc. The current standard for Ontario is based on the work by Lee et al. 1998.

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Fix nitrogen: To take atmospheric nitrogen and change it into a form that is accessible to living organisms.

Forb: A broad-leaved, herbaceous plant.

Nodule: A swelling on a leguminous root containing symbiotic bacteria.

Prairie obligate: A species that only lives in the prairie ecosystem because it must have prairie conditions to survive.

Rhizome: A horizontal stems that grows along the ground.

Scarification: To make cuts or scratches or to break the surface of something.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

Symbiotic: Interaction between different organisms that usually provides a mutual advantage to both.

References

Ambrose, J. D., and G. E. Waldron. 2005. Draft National Recovery Strategy for Tallgrass Communities of southern Ontario and their associated species at risk. Draft recovery plan prepared for the Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Team. Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW), Ottawa, Ontario.

Argus, G.W. and D.J. White. 1977. The Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario. National Museum of Canada, Ottawa. Syllogeus 14.

Argus, G.W. and D.J. White. 1982. Atlas of Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa.

Argus, G.W. and D.J. White. 1983. Atlas of Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario, Part 2. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa.

Argus, G.W. and C.J. Keddy. 1984. Atlas of Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario, Part 3. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa.

Bakowsky, W.D. and J.L. Riley. 1994. A survey of the prairies and savannas of southern Ontario, in R.G. Wickett, P.D. Lewis, A. Woodliffe, and P. Pratt (eds.) Proceedings of the Thirteenth North America Prairie Conference: pp. 7–16.

Blocksome, C. E. 2006. Sericiea Lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata): seed dispersal, monitoring, and effects on species richness. PhD thesis, Kansas State University. http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/192 Accessed November 11, 2012

Brinker, S.R. 2012. Personal communication to J. Jones by email on November 13, 2012. Project botanist at the Natural Heritage Information Centre of Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario.

Canada-U.S.-Ontario-Michigan Border Transportation Partnership. 2009. Detroit River International Crossing Study, Appendix E: Supplementary Mitigation Approach for Species at Risk CEAA Screening Report CEAR No: 06-01-18170 http://www.partnershipborderstudy.com/reports_canada.asp

Chicago Botanic Garden. 2012. A summary of the projects in plant demography and the research of Pati Vitt. http://www.chicagobotanic.org/research/staff/vitt.php#publications accessed November 12, 2012.

Clewell, A.F. 1964. The biology of the common native Lespedezas in Southern Indiana. Brittonia v. 16, pp. 208–219.

Clewell, A.F. 1966. Native North American species of Lespedeza (Leguminosae) . Rhodora v. 68 pp. 359–405.

COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the slender bush- clover Lespedeza virginica in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 9 pp.

COSEWIC. 2012a. 6-month Interim draft COSEWIC status report for Slender Bush- clover, October 2012. Expected publication date 2013. Used with permission of the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. http://www.cosewic.gc.ca

COSEWIC. 2012b. COSEWIC status information for Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. http://www.cosewic.gc.ca accessed November 15, 2012.

Forman, R.T.T., and L.E. Alexander. 1998. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29: 207–231.

Forman, R.T.T., D. Sperling, J.A. Bissonette, A.P. Clevenger, C.D. Cutshall, V.H. Dale, L. Fahrig, R. France, C.R. Goldman, K. Heanue, J.A. Jones, F.J. Swanson, T. Turrentine, and T.C. Winter. 2003. Road ecology: Science and solutions. Island Press. Covelo CA.

Fraver, S. 1994. Vegetation responses along edge-to-interior gradients in the mixed hardwood forests of the Roanoke River Basin, North Carolina. Conservation Biology 8(3): 822–832.

Gleason, H.A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada , 2nd ed. New York Botanical Garden, 910 pp.

Harris, H. L. and W. B. Drew. 1943. On the establishment and growth of certain legumes on eroded and uneroded sites. Ecology 24(2): 135–148.

Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. OMNR, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide FG-02. 225 pp.

Ludolph, R. 2012. Personal communication to J. Jones by telephone on November 20, Partnership facilitator, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Chatham, and former coordinator for Lambton County Stewardship Network.

Matlack, G.R. 1993. Microenvironment variation within and among forest edge sites in the eastern United States. Biological Conservation 66(3): 185–194.

NatureServe. 2012. Explorer: an online encyclopedia of life. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. Accessed: November 10 and 19, 2012.

Natural Heritage Information Centre (NHIC). 2012. Database information. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, ON. http://nhic.mnr.gov.on.ca/

Ojibway Nature Centre. 2012. Ojibway Bird Checklist.http://www.ojibway.ca/birds.htm Accessed November 12, 2012.

Pratt, P.D. 1986. Status report on Slender Bush-clover Lespedeza virginica (L.) Britt. (Fabaceace). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 23 pp.

Pratt, P.D. 2012. Personal communication to J. Jones by email on November 14, 2012. Naturalist, Ojibway Park Nature Centre, City of Windsor.

Reznicek, A.A., E. G. Voss, and B. S. Walters. 2011. Michigan Flora Online. University of Michigan. http://michiganflora.net/species.aspx?id=1325 accessed November 10, 2012.

Schutzenhofer, M. 2007. The effect of herbivory on the mating system of congeneric native and exotic Lespedeza species. International Journal of Plant Science 168(7):1021–1026.

Simpson, R. A. 1999. The effect of pollination and resources on the reproduction and establishment of Lespedeza virginica (Fabaceae). Doctoral dissertation, University of Michigan.

Vitt, P. 2012. Personal communication to J. Jones by telephone on November 9, 2012. Conservation scientist, Chicago Botanic Garden, and seed bank curator, Dixon National Tallgrass Prairie Seed Bank.

Voss, E. G. 1985. Michigan Flora, Part II. Cranbrook Institute of Science Bulletin 59, University of Michigan Herbarium. Ann Arbor, Michigan. 724 pp.

Waldron, G. 2010. Personal communication to J. Jones by telephone during work on Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata), Colicroot (Aletris farinosa), and Willow-leaf Aster (Symphyotrichum praealtum). Consulting ecologist, Amherstburg, Ontario.

Walpole Island Heritage Centre. 2006. E-niizaanag Wii-Ngoshkaag Maampii Bkejwanong: Species at Risk on the Walpole Island First Nation. Bkejwanong Natural Heritage Program, 130 pp.

Woodliffe, P.A. 2012. Personal communication to J. Jones by email on November 9, District Ecologist (retired), Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aylmer District, Chatham, Ontario.

Woodliffe, P.A. 2010. Personal communication to J. Jones by email on December 1, 2010 during work on Dense Blazing Star (Liatris spicata), Colicroot (Aletris farinosa), and Willow-leaf Aster (Symphyotrichum praealtum). District Ecologist (retired), Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aylmer District, Chatham, Ontario.

Yao, Z.Y., F.L. Kan, E.T. Wang, G.H. Wei, and W.X. Chen. 2002. Characterization of rhizobia that nodulate legume species of the genus Lespedeza and description of Bradyrhizobium yuanmingense sp. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology v. 52, pp. 2219 – 2230. http://ijsb.sgmjournals.org/content/52/6/2219.full.pdf

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph All patches that occur within 1 km of each other are considered to belong to the same population or occurrence. Patches at greater distance may also be included if there is no significant break or change in the habitat. See NHIC (2012) for a detailed definition of occurrence.