Spotted Wintergreen Recovery Strategy

This document advises the ministry on ways to ensure healthy numbers of the spotted wintergreen, a threatened or endangered species, return to Ontario.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

February 2010

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA, 2007) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA, 2007, a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge onwhat is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA, 2007 outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There is a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA, 2007. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Ursic, K., T. Farrell, M. Ursic and M. Stalker. 2010. Recovery Strategy for the Spotted Wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 28 pp.

Cover illustration: Allen Woodliffe, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2010

ISBN 978-1-4435-2092-8 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Authors

Ken Ursic, Beacon Environmental

Todd Farrell, Nature Conservancy of Canada

Margot Ursic, Beacon Environmental

Margaret Stalker, University of Guelph

Acknowledgments

Members of the recovery team wish to acknowledge André Sabourin, Jacques Labrecque, Bob Bowles, Don Sutherland, Dr. A. Reznicek, and Dr. I. MacDonald for providing population census data and status updates, as well as Dr. E. Haber, Chris Risley, Bill Crins, Rodger Leith, Al Dextrase, Karen Hartley and Roxanne St. Martin for their editorial input. In addition, the Recovery Team would like to thank the many individuals who provided technical expertise to assist the development of the recovery strategy for this species.

Declaration

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has led the development of this recovery strategy for the Spotted Wintergreen in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario

Executive summary

This recovery strategy outlines the objectives and approaches necessary for the protection and recovery of Ontario populations of Spotted Wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata). The strategy is based on a comprehensive review of current and historical population census data and consultations with knowledgeable individuals.

Populations of Spotted Wintergreen occur primarily as distinct colonies composed of few to several individuals. As stems arise from the creeping rhizomes of this plant (Kirk 1987), it is probable that clumps or contiguous groupings of stems actually represent clones or ramets rather than single individuals. In southern Ontario, the plant’s flowers generally open in mid-July and are likely pollinated by Bombus spp. The morphology of the seeds (small, wingless, tailed and ribbed) suggests that seed dispersal is principally by anemochory (i.e., wind dispersal). Spotted Wintergreen has been reported as having mycorrhizal associations, although the type and nature of the association remains unclear.

The long-term recovery goals for Spotted Wintergreen are to protect and enhance all extant populations to ensure that sustainable levels are established or maintained, and to restore historical populations and establish new populations in appropriate habitat, if deemed feasible. The recovery objectives for this species place greatest emphasis on ensuring the protection of extant populations. To that end, several specific objectives have been identified:

- Identify and protect habitat for extant populations;

- Identify and mitigate threats through monitoring and management;

- Monitor populations regularly to determine trends and habitat conditions;

- Develop education and stewardship programs for private landowners;

- Initiate research to fill knowledge gaps;

- Investigate the feasibility of recovery potential of historic sites or other suitable habitat.

Recovery approaches include the protection of habitat, identification and mitigation of threats to populations through continued monitoring and management, conservation of the genetic pool though gene banking, and experimental micro-propagation.

Many of the recovery activities identified in this recovery strategy are contingent on the outcome of future research initiatives, as basic knowledge of the species' habitat requirements, population biology, and propagation requirements is lacking. The recovery strategy outlines and prioritizes research programs necessary to support the implementation of the identified recovery approaches.

It is recommended that the area to be prescribed as Spotted Wintergreen habitat in a habitat regulation include the area occupied by extant populations and the extent of the vegetation community (based on the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) for southern Ontario) in which it occurs at each site. This will allow for future growth, expansion and migration of these populations.

1.0 background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

Common name: Spotted Wintergreen

Scientific name: Chimaphila maculata

SARO List classification: Endangered

SARO List history: Endangered (2008), Endangered – Regulated (2004) COSEWIC Assessment History: Endangered (2000)

SARA Schedule 1: Endangered (June 5, 2003)

Conservation status ranks:

GRANK: G5 NRANK: N1 SRANK: S1

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Spotted Wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata) is a small, rhizomatous evergreen herb or sub-shrub. It is similar to Pipsissewa (Chimaphila umbellata), and the two share the same habitat, but they differ in that Pipsissewa lacks the conspicuous white stripes along the veins on the upper surface of the leaves (Kirk 1987). Although isolated individuals do occur, large colonies of clones (ramets) may be formed by the growth of shallow, horizontally spreading rhizomes that produce erect shoots. The plant can grow to a height of 50 centimetres high (Flora of North America 2009). Each shoot bears several whorls of smooth leaves and a terminal cluster of one to five white or pinkish fragrant flowers (from Standley et al. 1988, Kirk 1987). The fruit is a roundish capsule up to one centimetre across (Flora of North America 2009).

Species biology

Populations of Spotted Wintergreen occur primarily as distinct colonies composed of few to several individuals. As stems arise from the creeping rhizomes of this plant (Kirk 1987), it is probable that clumps or contiguous groupings of stems actually represent clones or ramets rather than single individuals, however no research has been undertaken to test this hypothesis.

The pollination biology of Spotted Wintergreen has been examined in one scientific paper by Standley et al. (1988), who studied sympatric populations of Spotted Wintergreen and Pipsissewa in a Massachusetts deciduous forest. This study found that both species flower for approximately 14 days beginning in early to mid-July and that they are both visited primarily by bumblebees of the genus Bombus. Spotted Wintergreen was visited primarily by Bombus perplexus, whereas Pipsissewa was visited by Bombus bimaculatus, B. vagans and B. perplexus. Knudsen and Oleson (1993) also found that Pipsissewa was visited exclusively by Bombus spp. except that the visitors were exclusively males.

Various field botanists and ecologists have observed that, in southern Ontario, the plant’s flowers generally open in mid-July for approximately 17 days and that plants produce abundant seed (Kirk 1987, K. Ursic pers. comm. 2001). These individuals also noted that fruiting occurs in August with the capsule splitting and releasing its seeds, many of which persist in the capsule into the next spring, and that seeds are small (0.4–0.6 mm long, 0.1–0.2 mm wide), wingless, tailed and ribbed (Kirk 1987). The morphology of the seeds suggests that seed dispersal is principally by anemochory (i.e., wind dispersal).

Spotted Wintergreen has been reported as having endotrophic mycorrhizal associations (i.e., with fungal filaments that may penetrate the plant cells), although the type and nature of the association remains unclear, and the fungal associates remain unknown. Boullard and Ferchau (1962) describe a mycorrhizal association of the ericoid type on root samples of Spotted Wintergreen collected from North Carolina, West Virginia, New York, New Hampshire and interestingly, Ripples, New Brunswick. However, given that Spotted Wintergreen has never been reported in New Brunswick prior or subsequent to Boullard and Ferchau’s (1962) publication, and that this location is outside of the plant’s known range, it places their plant identification(s) into question.

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

Global range

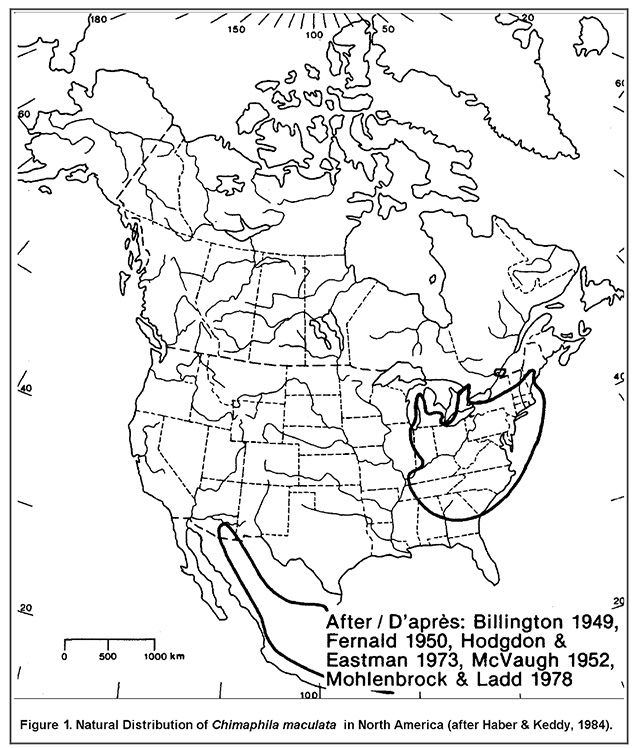

Spotted Wintergreen occurs naturally in eastern North America, Mexico and Central America. Its range in eastern North America is from southern Michigan and Ontario to southern New Hampshire and Maine, south to Mississippi and northern Florida (Figure 1). The western limits appear to be western Kentucky and Tennessee, and eastern Illinoi Its southern range is from Central America, through Mexico to Arizona. However, available information limits a detailed analysis of the global abundance of this species.

The global conservation status rank for Spotted Wintergreen is G5, which is considered secure (NatureServe 2009). NatureServe also applies conservation status ranks at the national (N) and sub-national (S) (i.e., state or provincial) level. In Canada, Spotted Wintergreen is ranked N1 (critically imperilled), and is listed as endangered federally under the Species at Risk Act and provincially on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Spotted Wintergreen is considered secure (S5) in the United States, but within the U.S., Spotted Wintergreen is considered critically imperilled (S1) in Illinois, and imperilled (S2) in Vermont, Maine, and Mississippi (NatureServe 2009). Furthermore, the species is legally protected in Illinois and Maine, where it has been designated as endangered, and in New York, where it is considered exploitably vulnerable (USDA, NRCS 2009).

Figure 1. Distribution of Spotted Wintergreen in North America (after Haber and Keddy, 1984)

Enlarge figure 1. Distribution of Spotted Wintergreen in North America (after Haber and Keddy, 1984)

Canadian range

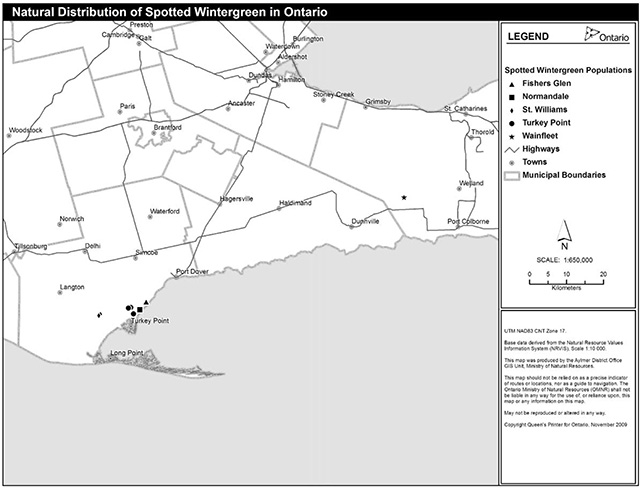

The current extant distribution of Spotted Wintergreen in Canada is restricted to a few locations in Ontario (Figure 2) that support an estimated 2,700 stems. Historically, Spotted Wintergreen was more widely distributed throughout southwestern and south central Ontario; however, it has since been extirpated from Simcoe Kent, Middlesex and York Counties, Hamilton-Wentworth Region and the District of Muskoka. In Quebec, a single population was discovered in 1992 at Parc d'Oka in Deux-Montagnes County in the southwestern part of the province (Jacobs 2001), and is now presumed extirpated there.

Figure 2. Current distribution of Spotted Wintergreen in Ontario

Enlarge figure 2 current distribution of Spotted Wintergreen in Ontario

An estimated 11 populations have been extirpated from a total of 16 known occurrences in Ontario. Populations are considered to be independent if separated by one kilometre or more of inappropriate habitat, and groupings of plants separated by less than one kilometre are considered sub-populations (Natural Heritage Information Centre 2001).

There are insufficient data available on extant populations to estimate long-term trends in population size for this species. Inconsistent methodology in population estimation and delineation of sub-populations as well as a lack of reliable data have made it equally difficult to estimate short-term trends for some extant populations.

Table 1. Estimated abundance of Spotted Wintergreen in Ontario

| County/Region | Population Name | Year of Last Survey | Approximate Number of Stems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norfolk | St. Williams | 2007 | 1923 |

| Norfolk | Turkey Point | 2009 | 591 |

| Norfolk | Normandale | 2005 | 165 |

| Norfolk | Fishers Glen | 2007 | 51 |

| Niagara | Wainfleet | 2007 | 7 |

In recent years, three populations have had notable increases in abundance, one population has had a marginal increase in abundance, and one additional population was recently discovered. In Norfolk County, a sub-population at the St. Williams site increased from 41 stems in 1985 to 1923 stems in 2007; similarly, the Normandale population increased from 10–15 stems in 1996 to 165 stems in 2005; seven new sub- populations have been discovered since 2004 at the Turkey Point site, bringing the estimated population for this site up to 591 in 2009, compared to 61 in 2008. The Fisher’s Glen population increased from 23 stems in 2000 to 51 stems in 2007. A new population was recently discovered in the Township of Wainfleet, Regional Municipality of Niagara.

1.4 Habitat needs

The key habitat attributes for Spotted Wintergreen, detailed below, include:

- association with dry to fresh oak-pine or oak dominated woodlands;

- limited competition with other groundcover species;

- partial shade;

- slightly acidic surface soil conditions (soil pH 4.2 to 6.0);

- well-drained soils (especially sandy soils) and sites;

- nutrient-poor soil conditions;

- moderated climate.

Spotted Wintergreen typically occurs in dry oak-pine mixed forest and dry woodland habitats (M. Gartshore pers. comm. 2001). Recent and available field observations have confirmed that Spotted Wintergreen is a woodland understorey species typically associated with dry–fresh oak and oak–pine mixed forests and woodlands. Ecological Land Classification (ELC) ecosites (Lee et al. 1998) for extant populations are CUP3, FOD1, FOD8, FOD9, or FOM2 (Table 2). These communities typically have semi-closed canopy conditions. The semi-open conditions of the vegetation communities in Ontario are a result of past disturbance, and will likely require further disturbance in the future to maintain suitable conditions for Spotted Wintergreen (A. Woodliffe pers. comm. 2006). The associated communities are characterised by an overstorey of White Pine (Pinus strobus), Red Oak (Quercus rubra), Black Oak (Quercus velutina) and American Beech (Fagus grandifolia), an understorey of Round-leaved Dogwood (Cornus rugosa), Pipsissewa and Witch Hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), and a groundcover layer of False Lily-of-the-Valley (Maianthemum canadense), Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum) and Wild Sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis) (T. Farrell pers. comm. 2001). Table 3 includes a summary of species noted in habitats occupied by Spotted Wintergreen for North America.

Table 2. Ecological Land Classification (ELC) Codes for sites that support extant populations

| Site Name | ELC Community (ELC Code) |

|---|---|

| St. Williams | Red Pine Coniferous Plantation Type (CUP3-1) |

| St. Williams | Fresh – Moist Poplar Deciduous Forest Type (FOD8-1) |

| St. Williams | Fresh – Moist Poplar Deciduous Forest Type (FOD8-1) |

| Turkey Point | White Pine Coniferous Plantation Type (CUP3-2) |

| Turkey Point | Dry – Fresh Black Oak Deciduous Forest Type (FOD1-3) |

| Turkey Point | Red Pine Coniferous Plantation Type (CUP3-1) |

| Turkey Point | White Pine Coniferous Plantation Type (CUP3-2) |

| Turkey Point | Fresh – Moist Poplar Deciduous Forest Type (FOD8-1) |

| Normandale | Dry - Fresh White Pine – Oak Mixed Forest Type (FOM2-1) |

| Fishers Glen | Dry - Fresh White Pine – Oak Mixed Forest Type (FOM2-1) |

| Wainfleet | Fresh – Moist Oak – Maple Deciduous Forest Type (FOD9-2) |

Table 3. Summary of species noted in habitats occupied by Spotted Wintergreen either currently or historically, as described in the available sources for North America

| Site Location | Dominant Overstorey | Dominant Understorey | Noted Groundcover |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Williams, (Kirk 1987) | Black Oak (Quercus velutina), White Oak (Q. alba), Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) | Witch Hazel (Hamamelis virginiana), Maple-leaved Viburnum (Viburnum acerifolium), Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) | Bracken Fern (Pteridium aquilinum), Pennsylvania Sedge (Carex pensylvanica), False Solomon’s Seal (Maianthemum racemosum), Shinleaf (Pyrola elliptica), Indian Pipe (Monotropa uniflora), Pale Blueberry (Vaccinium pallidum), Pipsissewa (C. umbellata) |

| Wasaga Beach, (extirpated) (Kirk 1987) | Large-toothed Aspen (Populus grandidentata), Red Oak (Q. rubra), Eastern White Pine | ||

| Wellesley, Massachusetts (Standley et al. 1988) | Red Oak, White Oak, Pignut Hickory (Carya glabra), Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata), Red Maple (Acer rubrum), Eastern White Pine | Low Sweet Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium), Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia), Sheep Laurel (Kalmia angustifolia), Black Huckleberry (Gaylussacia baccata), Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago), Maple-leaved Viburnum | Bracken Fern, False Lily-of-the- Valley (Maianthemum canadense), Shinleaf, Indian Pipe, Pink Ladyslipper (Cypripedium acaule), Sessile- leaved Bellwort (Uvularia sessilifolia), Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens), Pipsissewa |

| Norridgerock, Maine (Eastman 1976) | Red Oak, Eastern White Pine, American Beech (Fagus grandifolia) | Round-leaved Dogwood (Cornus rugosa) | Running Club-moss (Lycopodium clavatum), Bracken Fern, Pennsylvania Sedge, False Lily-of-the-Valley, Wild Sarsaparilla (Aralia nudicaulis), Green Shin-leaf (Pyrola chlorantha), Pipsissewa, Ram’s Head Lady Slipper (Cypripedium arietinum), Hooker’s Orchid (Plantanthera hookeri), Showy Orchis (Galearis spectabilis) |

| Peaked Mountain, Hiram, Maine (Eastman 1976) | Red Oak, White Birch (Betula papyrifera), American Beech | Witch Hazel, Maple-leaved Viburnum | |

| Lusk Creek, Illinois (Jones and Fralish 1974) | Black Oak, White Oak, Scarlet Oak (Q. coccinea), Hickory (Carya spp.) | False Dandelion (Krigia biflora), Dittany (Cumila origanoides), Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum biflorum), False foxglove (Aureolaria flava), Wild Licorice (Galium circaezans) |

As White (1998) pointed out, all extant sites in Ontario are close to large bodies of water and the moderating effect on the climate may be an important factor. Kirk (1987) provided site-specific information with respect to climate at the St. Williams site, and mentions the moderating effect of Lake Erie and Georgian Bay as a factor at the St. Williams site and (former) Wasaga beach sites respectively.

Information on microsite preferences for Spotted Wintergreen is limited. The plant appears to have a relatively narrow pH range. Standley et al. (1988) recorded soil pH values of 4.2 to 4.6 at a Spotted Wintergreen site in Massachusetts. Other studies report that the species prefers an average soil pH below 7 (Eastman 1976, Kirk 1987), but actual soil sampling at any of the Ontario sites has yet to be conducted. Interestingly, Kirk (1987) noted that based on field observations, Spotted Wintergreen differs from its close relative Pipsissewa in that it is unable to tolerate the higher acidity found in pure pine stands created by dense layers of needle duff, and appears to prefer mixed oak-pine woodlands.

The plant tends to occur on sandy soils that are essentially stone-free with low organic content, having good drainage and nutrient poor status (Kirk 1987). The Ontario populations of Spotted Wintergreen occur on relict sand dunes (A. Woodliffe pers. comm. 2006). Kirk (1987) also noted that the plant appears to prefer insolated sites (i.e., sites with some sun exposure) lacking soil moisture extremes. However, no quantitative assessment of the habitat conditions for this species has been undertaken to date.

1.5 Limiting factors

Reproductive biology

Although aspects of the reproductive biology of Spotted Wintergreen may be limiting factors, there has been far too little study on the subject to draw any definitive conclusions. Standley et al. (1988) point out that having a limited number of shared pollinators, as is the case with Spotted Wintergreen, can reduce aspects of plant fitness (e.g., reduced seed set, production of infertile hybrids, reduced floral visitation). They acknowledge that their results do not allow testing of these hypotheses and that further study is required. Further scientific research is also required to determine whether seed dispersal is a limiting factor.

It is also possible that lack of sexual reproduction of Ontario populations may represent a potential limiting factor for Spotted Wintergreen. Unfortunately, the only scientific reports on this topic for this genus deal with Pipsissewa (Barrett and Helenurm 1988a, b). These studies found that Pipsissewa exhibited mostly clonal growth and, like many boreal forest herbs, was limited in fruit-set production by pollen limitation and predation of developing fruit. However, further research into modes and mechanisms of reproduction in Spotted Wintergreen are required to determine if this holds true for this species as well.

Spotted Wintergreen is capable of reproducing either clonally or by seed (Standley et al. 1988). Clones may consist of few to several hundred stems (ramets), and therefore, a population consisting of several hundred stems may represent only one to several individuals. However, determining the precise number of clones or individuals within a large and/or tightly spaced population requires excavation or genetic analysis that has not been completed for a population of Spotted Wintergreen. Although the Ontario populations do appear to flower and produce seed regularly, it has been hypothesized that low seed viability and dispersal must be limiting intrinsic factors to population growth, given that unoccupied suitable habitats are readily available at most extant sites (Kirk 1987). However, once again, additional scientific research is required to confirm this hypothesis.

Mycorrhizal associations

The mycorrhizal status of Spotted Wintergreen may also present a limiting factor if mycorrhizae are required for survival, and its fungal associates are uncommon. Some studies of the mycorrhizae of Spotted Wintergreen are questionable, as discussed in section 1.2. Nonetheless, it seems likely that Spotted Wintergreen has a mycorrhizal association to some degree, since other species of this genus display various types of mycorrhizal associations (Largent et al. 1980, Boullard and Ferchau 1962, Henderson 1919).

Soil requirements

Spotted Wintergreen occurs on well-drained slightly acidic sandy soils and is typically associated with dry–fresh oak and oak pine forest communities. Research at the Hazelwood Botanical Preserve in Ohio indicated that a soil pH in excess of seven would exclude Spotted Wintergreen. Given the predominance of alkaline soils in southern Ontario, Spotted Wintergreen’s preference for slightly acidic soils may represent another limiting factor for this species, although even on generally basic soils, surface reactions may be acidic. No Spotted Wintergreen sites in Ontario have been tested to determine soil pH; therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the degree to which soil type is limiting.

Population isolation

Habitat for Spotted Wintergreen is fragmented, resulting in isolated populations, restricted gene flow and reduced genetic diversity. Poor genetic exchange within and among populations can reduce overall species fitness. Not enough is known about the population biology of the species to determine the minimum habitat size or number of individuals necessary to support a viable population.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Forest management

Current land uses and activities can potentially conflict with conservation of the species. Such activities could include: a commercial tree nursery, a logging road related to silvicultural operations, use and/or maintenance of an irrigation line, and prescribed burning for management of other species. These activities could result in canopy removal, alteration of species composition of associated plant communities, soil compaction, or could provide a vector for the introduction of invasive species. Habitat changes associated with the conversion of open dunes, savannas and woodlands to pine plantations and increased levels of anthropogenic disturbance may have contributed to the loss of extirpated populations. In a recent survey report of the Wasaga Beach Provincial Park sites by Bowles (2001), Dr. A. Reznicek has remarked on the extent of canopy closure that has occurred in the plantations over the past 25 years due to better fire suppression.

Competition with other plant species

Although Pipsissewa shares Spotted Wintergreen’s range and habitat, even at a microsite level, it is unclear whether it poses any kind of competition threat (Standley et al. 1988). Presumably, invasive species would also be a potential threat, although this threat has not been confirmed at any of the extant sites. Disturbance due to recreational trails and tree harvesting could provide a vector for the introduction of invasive species.

Trampling/soil compaction

Any activity that would result in trampling could potentially harm the species. Spotted Wintergreen prefers undisturbed soils, and any activities that result in soil disturbance or compaction could be detrimental (NatureServe 2009). Kirk (1987) comments that the site of the extirpated population from near the town of Simcoe, Norfolk County, was a small woodlot that had experienced extensive disturbance from all-terrain vehicles (ATVs), possibly contributing to the elimination of the species at that location. Several sites have recreational trails for hiking, walking, snowshoeing, and ATV use, all of which have a potential to result in trampling and soil compaction. The effects of these activities are unknown, but could affect populations by altering habitat conditions or destroying plants.

Waste disposal

Waste disposal is a threat at the Wainfleet site. When the site was surveyed, a few old car parts were found near the site (T. Staton pers. comm. 2009). If additional scrap is accidentally deposited directly on top of the plants, the entire population could be eliminated due to the very limited extent of this site.

Collecting

Although White (1988) reported human threats from collecting on one occasion, the threat is currently considered to be low. Populations are primarily located in moderately low traffic areas and knowledge of the species' whereabouts is limited. No empirical evidence of the above noted threats has been collected to date.

Animal foraging

There are no documented natural browsers for this species, but the Woodland Vole (Pitymys pinetorum), which is a special concern species on the SARO List, has a range, distribution, and habitat similar to Spotted Wintergreen and is suspected to forage on the rhizomes of this species. This constitutes a potential threat, but conversely could benefit Spotted Wintergreen by assisting in its dispersal (M. Gartshore pers. comm. 2001), thus the role of small mammals needs to be clarified through further research.

Foraging activities of Wild Turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) have caused significant forest floor disturbance at the St Williams site, where Wild Turkeys gather in high concentrations, particularly during the winter (Gould 2001). Scratching and uprooting behaviour of turkeys might potentially damage rhizomes of Spotted Wintergreen and create openings in the groundcover where invasive species could colonize. The actual impact of this activity is currently unknown.

Table 4 provides a summary of an evaluation of human threats to individual populations and categorizes the threats based on their source, type, spatial and temporal extent, as well as the certainty that the threat is currently affecting the population. Natural threats (animal foraging and competition) occur at all sites.

Table 4. Evaluation of threats to Spotted Wintergreen

| Population | Source of Threat | Temporal Extent | Certainty |

|---|---|---|---|

| St. Williams | Trampling/Soil Compaction* | Ongoing | probable |

| St. Williams | Forest Management** | Occasional | speculative |

| St. Williams | Collecting | Short-term | confirmed |

| Turkey Point | Trampling/Soil Compaction* | Ongoing | probable |

| Turkey Point | Forest Management** | Occasional | speculative |

| Turkey Point | Collecting | Short-term | speculative |

| Normandale | Forest Management** | Occasional | speculative |

| Normandale | Collecting | Short-term | speculative |

| Fishers Glen | Forest Management** | Occasional | speculative |

| Fishers Glen | Collecting | Short-term | speculative |

| Wainfleet | Trampling/Soil Compaction* | Ongoing | probable |

| Wainfleet | Forest Management** | Occasional | speculative |

| Wainfleet | Waste Disposal | Ongoing | probable |

*Trampling/Soil Compaction includes use of trails for ATV riding, walking, etc.

**Forest management activities include logging, pesticide/herbicide use for silviculture, and maintenance of logging roads.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Based on a review of the literature it is clear that the available information on Spotted Wintergreen is very limited. Additional research is required to obtain knowledge that will contribute to the protection and recovery of this species. Basic research needs for the species are listed below in order of importance:

- Census and verification of all extant populations using standardized, objective and repeatable methods.

- Research into feasibility of gene banking material from vulnerable populations, survey of genotypic diversity, species propagation and translocation.

- Research into the population and reproductive biology of this species.

- Research into the specific habitat requirements of this species.

- Research potential threats to populations of this species.

Survey requirements

Reliable, accurate, and current census information on populations of Spotted Wintergreen in Ontario is incomplete or lacking. Inconsistencies in naming and geographical referencing of populations and sub-populations have prevented detailed comparative analyses of population trends. Information collection needs to be standardized to reflect reliable baseline data, from which future recovery actions will be developed.

Biological / ecological research requirements

At present, the population biology, genetics and ecology of Spotted Wintergreen are not well understood. Information on the genetic variability within and among populations is necessary to assess population viability. A population viability assessment (PVA) is necessary to more precisely define the population and habitat size thresholds necessary to achieve self-sustaining populations of this species. Understanding the minimum viable population is essential in guiding recovery actions.

Aspects of the reproduction of Spotted Wintergreen that remain unclear are: the primary mode of reproduction (whether clonal or sexual), the relative importance of its pollination biology, and the role of pollinators. Furthermore, there has been little research into characterizing habitat conditions and requirements for the species, including the nature of its mycorrhizal associations and soil pH requirements specific to southern Ontario. Additional research is required in all these fields.

Threat clarification research requirements

At present, there is no research that directly examines natural and human threats to this species. Most of the threats to this species are speculative and require further research to ascertain their potential impact. All potential threats to Spotted Wintergreen should be investigated empirically and weighted against limiting factors, such as potentially low seed viability or specific affinities for particular habitats. It is critical to have good empirical data available to guide the development of appropriate threat mitigation activities.

Despite the knowledge gaps, priority recovery approaches that could benefit the species should be implemented immediately.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Recovery actions for Spotted Wintergreen that are complete or currently underway include:

- Population census and habitat monitoring for some sub-populations has been completed up to 2009;

- Ecological Land Classification designations/mapping to support the delineation of the area recommended to be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation has been completed for most sub-populations

- Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program mapping was completed in 2001 for some sub-populations;

- Habitat management on public lands is on-going as necessary (e.g., creation of Species at Risk signage at St. Williams Conservation Reserve, forest management advice);

- Education and stewardship with private landowners is on-going as necessary (e.g., forest management advice).

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources staff last performed a complete census of all Norfolk County populations in April and May of 2005, and only some sub-populations from 2006 and 2008. Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority staff completed a census of the Wainfleet population in 2007. A consultant surveyed some sub-populations at Turkey Point in 2009.

Some of the actions being taken to implement the federal Tallgrass Communities of Southern Ontario Recovery Plan focus on conservation of prairies, savanna and woodland vegetation communities. These actions may also provide habitat for Spotted Wintergreen populations. That recovery plan involves the identification of prairie related sites and a landowner contact program that began in the summer of 2001, and may reveal additional information about Spotted Wintergreen.

2.0 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goals

The long-term recovery goals for Spotted Wintergreen are to protect and enhance all extant populations to ensure that sustainable levels are established or maintained, and to restore historical populations and establish new populations in appropriate habitat, if deemed feasible.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

The recovery objectives for this species place greatest emphasis on ensuring the protection of extant populations. To that end, several specific objectives have been identified (Table 5).

Table 5. Protection and recovery objectives

| No. | Protection or Recovery Objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Identify and protect habitat for extant populations |

| 2 | Identify and mitigate threats through monitoring and management |

| 3 | Monitor populations regularly to determine trends and habitat conditions |

| 4 | Develop education and stewardship programs for private landowners |

| 5 | Initiate research to fill knowledge gaps |

| 6 | Investigate the feasibility of recovery potential of historic sites or other suitable habitat |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

Table 6. Approaches to recovery of the Spotted Wintergreen in Ontario

1. Identification and protection of habitat for extant populations

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection |

1.1 Identify area required to protect extant populations

|

|

| Critical | Short-term | Protection |

1.2 Habitat Protection

|

|

2. Identification and mitigation of threats through monitoring and management

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Protection, Management |

2.1 Management on public lands

|

|

| Critical | Long-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment, Research |

2.2 Threat Clarification, Reduction and Mitigation

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Management, Research |

2.3 Habitat Management

|

|

3. Regular monitoring of population trends and habitat conditions

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | On-going | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

3.1 Population Census

|

|

| Necessary | On-going | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment |

3.2 Habitat Monitoring

|

|

4. Development of supportive education and stewardship programs for private land

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | On-going | Stewardship |

4.1 Education and Stewardship

|

|

5. Initiate research to fill knowledge gaps

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

5.1 Species Ecology and Habitat Research

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

5.2 Population Biology and Genetics Research

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

5.3 Genetic Conservation

|

|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

5.4 Plant Propagation Research

|

|

- Initiate research on species conservation, including recovery potential of historic or other suitable sites

| Relative Priority | Relative Timeframe | Recovery Theme | Approach to Recovery | • Threats or Knowledge Gaps Addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Necessary | Long-term | Research |

6.1 Species Reintroduction and Restoration Research

|

|

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

Recovery efforts require close coordination with recovery actions for other species of concern in the area since the plant shares its habitat with other threatened and/or endangered species. For example, controlled burns are used as a management tool for Virginia Goat’s-rue (Tephrosia virginiana, endangered both provincially and federally) and Bird’s-foot Violet (Viola pedata, endangered provincially and federally), which could have a potential impact on Spotted Wintergreen populations. Consideration should be given to initiating recovery actions that would benefit multiple species, particularly in the Norfolk County area.

Spotted Wintergreen is known to be difficult to propagate artificially and immediate recovery efforts should focus on working with populations in situ before attempting to grow the plant in vitro (Duncan and Kartesz 1981). Cullina (2000) reports complete lack of success in germinating the seed, possibly due to the need for fungal associates; however, Cullina states that Spotted Wintergreen is easily propagated from cuttings taken in midsummer. The Plants for a Future website (2009) suggests using soil from the collection site (because of presumed mycorrhizal associations) and minimizing root disturbance as much as possible during transplantation. They also recommend using a moist sphagnum substrate. The noted sensitivity of the root systems may explain why the plant may be susceptible to anthropogenic disturbances such as trampling or ATV use.

The highest research priority and level of recovery effort should be directed toward the largest populations (St. Williams, Turkey Point, and Normandale), which appear to be viable and expanding. These populations could serve as living laboratories in which to research the population biology, habitat requirements, propagation and gene banking potential for future population augmentation or re-introduction programs.

The population at Fishers Glen is also showing some expansion, but much more slowly. For this smaller population, as well as the newly discovered Wainfleet population, emphasis should be placed on monitoring and assessment of habitat conditions and threats. Based on current limited understanding of the population biology and habitat requirements of this species, it is unlikely that the recommended approaches could be effectively implemented over the short term for these populations. A long-term approach could implement recommendations derived from research on the larger populations, to attempt to improve survival and re-establishment.

2.4 Performance measures

The success of recovery efforts can be measured through ongoing monitoring of populations and threats, assessment of habitat conditions and evaluating the status and progress of the specified research, management, stewardship and education programs (Table 7). Performance measures should be based on the extent to which goals and objectives have been met.

Table 7. Performance measures for the recovery of Spotted Wintergreen

| Objective | Performance Measure |

|---|---|

| 1. Identification and protection of habitat for extant populations |

|

| 2. Identification and mitigation of threats through monitoring and management |

|

| 3. Regular monitoring of population trends and habitat conditions |

|

| 4. Development of supportive education and stewardship programs for private land |

|

| 5. Initiate research to fill knowledge gaps |

|

| 6. Initiate research on species conservation, including recovery potential of historic or other suitable sites |

|

2.5 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA 2007, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the recovery team will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The minimum area that should be prescribed as habitat in a habitat regulation for Spotted Wintergreen should include the area occupied by all extant populations and the surrounding extent of the vegetation community (based on the ELC for Southern Ontario) in which it occurs. Additional setbacks may be required for specific activities to protect against direct or indirect threats. This allows for future growth, expansion and migration of these populations and is consistent with provincial habitat mapping guidelines for the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources 1998). Known Ecological Land Classifications for extant sites are described in section 1.4, Table 2. These boundaries should be refined as more information is gained on the factors that may influence habitat suitability and quality.

In Ontario, the current occupied habitats are restricted to the southwestern part of the province. However, historical records for Ontario indicate that, given the appropriate site conditions, Spotted Wintergreen has established itself throughout southern Ontario and as far north as Muskoka District. Consequently, potential habitats, after further study, may include historical locations within the species' range as well.

Habitat that is not currently occupied by the species, or not currently known to be occupied, may also be required for recovery of the species. Before suitable habitat for reintroduction can be identified (including historic sites), further research is necessary to define optimum habitat attributes. Potential recovery areas would include sites within the species' range that exhibit many of the key habitat attributes listed in section 1.4. Presumably a natural site with these attributes would also support the fungal species that may be required to establish the appropriate mycorrhizal associations with the plant. In addition, given the plant’s potential sensitivity to trampling and ATV use, it would be advisable to select locations where these activities are restricted.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or sub-national (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperiled

2 = imperiled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA 2007): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk to which the SARA provisions apply. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Barrett, S.C.H. and K. Helenurm. 1988a. The reproductive biology of boreal forest herbs: I. Breeding systems and pollination. Canadian Journal of Botany 65(10): 2036-2046.

Barrett, S.C.H. and K. Helenurm. 1988b. The reproductive biology of boreal forest herbs: II. Phenology of flowering and fruiting. Canadian Journal of Botany 65(10): 2047-2056.

Boullard, B. and H. A. Ferchau. 1962. Endotrophic mycorrhizae of plants collected in some eastern American and Canadian white pine communities. Phyton 19: 65-71.

Bowles, B. 2001. Field Survey Report on the Status of Spotted Wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata) at three Wasaga Beach Provincial Park Sites. Bowles Environmental. Produced for Ontario Parks.

Cullina, W. 2000. The New England Wildflower Society Guide to Growing and Propagating Wildflowers of the United States and Canada. Houghton Mifflin, New York. 69-70, 249 pp.

Duncan, W.H., J.T. Kartesz. 1981. Vascular Flora of Georgia. University of Georgia Press. Athens, GA.

Eastman, L.M. 1976. Spotted Wintergreen, Chimaphila maculata (L.) Pursh in Maine and its Relevance to the Critical Areas Program. Planning Report No. 21, State Planning Office, Maine Critical Areas Planning Program, Augusta, Maine.

Farrell, T. 2001. Personal communication.

Flora of North America. 2009. Flora of North America North of Mexico: Volume 8 Magnoliophyta: Paeoniaceae to Ericaceae. Oxford University Press. New York. Gartshore, M. 2001. Personal Communication.

Gould, R. 2001. Spotted Wintergreen (Chimaphila maculata) 2001 Survey Report. Unpublished Report.

Haber, E. and C. J. Keddy. 1984. Chimaphila maculata (L.) Pursh. A page in the Atlas of the Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario, Part 3, Eds. G. W. Argus and C. J. Keddy, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa. 1982-1987 pp.

Henderson, M.W. 1919. A Comparative Study of the Structure and Saprophytism of the Pyrolaceae and Monotropaceae with Reference to their Derivation from the Ericaeae. Ph.D. Disseration, Faculty of Graduate Studies.

Jacobs, D. 2001. Spotted Wintergreen: Chimaphila maculata at Parc D'Oka, Quebec. Unpublished Report.

Jones, S. M. and J. S. Fralish. 1974. A state record for Chimaphila maculata (L.) Pursh. in Illinois. Transactions of the Illinois State Academy of Science 67(4): 441.

Kirk, D. 1987. COSEWIC status report on the Spotted Wintergreen Chimaphila maculata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 36 pp.

Knudsen, J. T. and J. M. Oleson. 1993. Buzz-pollination and patterns in sexual traits in north European Pyroleaceae. American Journal of Botany 80(8): 900-913.

Largent, D. L., N. Sugihara, and C. Wishner. 1980. Occurrence of mycorrhizae on ericaceous and pyrolaceous plants in northern California. Canadian Journal of Botany 58: 2274-2279.

Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J.Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological Land Classification for Southern Ontario: First Approximation and Its Application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, South Central Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch. SCSS Field Guide FG-02.

Natural Heritage Information Centre. 2001. Natural Heritage Information Centre Data Access and Sensitivity Training Manual. NHIC, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Peterborough. 69 pp.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available http://www.natureserve.org/explorer. (Accessed: October 21, 2009).

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 1998. Guidelines for Mapping Endangered Species Habitats under the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program. Peterborough, Ontario.

Plants for a Future. 2009. http://www.pfaf.org/database/plants.php?Chimaphila+maculata

Standley, L. A., S. Kim and I. Hjersted. 1988. Reproductive Biology of Two Sympatric Species of Chimaphila. Rhodora. 90(863): 233-244. Staton, T. 2009. Personal communication.

Ursic, K. 2001. Personal communication.

USDA, NRCS. 2009. The Plants Database. Available at: http://plants.usda.gov (Accessed 21 October 2009). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA.

White, D.J. 1998. Update COSEWIC status report on spotted wintergreen Chimaphila maculata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-6 pp.

Woodliffe, A. 2006. Personal communication.

Recovery team members

Recovery Team Members

| Name | Affiliation and location |

|---|---|

| Ron Gould (Chair) | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aylmer |

| Kate MacIntyre (Co-Chair) | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aylmer |

| Allen Woodliffe | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Chatham |

| Donald Kirk | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Guelph |

| Mary Gartshore | Pterophylla, Walsingham |

Advisors/Associated Specialists

| Name | Affiliation and location |

|---|---|

| Gary Allen | Parks Canada Agency, Ottawa |

| Karine Beriault | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Vineland |

| Melinda Thompson-Black | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Aurora |

| Marilyn Beecroft | Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Wasaga Beach Provincial Park |

| Deb Jacobs | Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Windsor |

| Tom Staton | Niagara Peninsula Conservation Authority, Welland |

| Erich Haber | National Botanical Services, Ottawa |

| Jane Bowles | University of Western Ontario, London |

Appendix 1. Additional resources on Spotted Wintergreen

Anderson, L.C. 1995. Noteworthy Plants from North Florida. VI. SIDA 16(3): 581-587. Argus, G.H and C.J. Keddy (eds.). 1984. Atlas of the rare vascular plants of Ontario, Part 3. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa, Ontario

Argus, G. W., K.M.O Pryer, D. J. White and C. J. Keddy eds. 1982-7. Atlas of the Rare Vascular Plants of Ontario, Parts 1-4, National Museum of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Catalogue No. NM 92-83/1982.

Brooklyn Botanical Gardens. 2009. http://nymf.bbg.org/species/323

Brown, R.G. and M.L. Brown. 1972. Woody plants of Maryland, Port City Press, Inc. Baltimore.

Camp, W.H. 1939. Studies in the Ericales IV. Notes on Chimaphila, Gaultheria and Pernettya in Mexico and adjacent regions. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 66(1): 1-28.

Caughley, G. and A. Gunn. 1996. Conservation Biology in Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press (Don Mills, Ontario).

Center for Field Biology. Miscellaneous Publication No. 13. Austin Peay State University, Clarksville.

Chapman, L. J. and D.F. Putnam. 1984. The physiography of Southern Ontario. 3rd Ed. Ontario Geological Survey.

Chester, E.W, B.E. Wofford, and R. Kral. 1997. Atlas of Tennessee Vascular Plants. Vol. 2.

Crovello, T.J., C.A. Keller, and J.T. Kartesz. 1983. The vascular plants of Indiana: A computer based checklist. University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame. University of Notre Dame Press. Notre Dame.

Dowhan, J.J. 1979. Preliminary Checklist of the Vascular Flora of Connecticut (growing without cultivation). State Geological and Natural History Survey of Connecticut, Natural Resources Center, Department of Environmental Protection. Hartford.

Eastman, L.M. 1978. New Station for Chimaphila maculata (L.) Pursh in Maine. Rhodora 80: 317.

George, G.G. 1992. A Synonymized Checklist of the Plants Found Growing in Rhode Island Rhode Island Wild Plant Society

Haber, E. and J.E. Cruise. 1974. Generic limits in the Pyroloideae (Ericaceae). Canadian Journal of Botany. 52: 877-883.

Harvill, A.M., C.E. Stevens, and D.M.E. Ware. 1977. Atlas of the Virginia Flora, Part I. Petridophytes through Monocotyledons. Virginia Botanical Associates. Farmville.

Hodgdon, A. R. and L. M. Eastman. 1973. Chimaphila maculata (L.) Pursh. In Maine and New Hampshire. Rhodora 75: 162-165.

Kearney, T. and R.H. Peebles. 1951. Arizona Flora. University of California Press. Los Angeles, California.

Kirk, D.A. 1986. Conservation Recommendations for Spotted Wintergreen Chimaphila maculata (L.) Pursh. A Threatened Species in Canada. Submitted to Committee on Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), 20 Feb. 1986.

Macoun, J. 1883-1890. Catalogue of Canadian Plants. Parts 1 to 5. Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa.

Medley, M. E. 1993. An Annotated Catalogue of the Known or Reported Vascular Flora of Kentucky. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Louisville.

Meyer, J. 1990. Chrysler Herbarium Checklist. Manuscript. Mississippi Natural Heritage Program.

Mitchell, R.S (ed.). 1986. A Checklist of New York State Plants. Contributions of a Flora of New York State, Checklist III. New York State Bulletin No. 458. New York State Museum. Albany

Mohlenbrock, R.H. 1986. Guide to the vascular flora of Illinois. Revised edition Southern Illinois University Press.

Mohr, C. 1901. Plant Life of Alabama. Contributions from the US National Herbarium, Vol. VI.

Poole, J. M. 1975. Chimaphila maculata in New Hampshire. Rhodora 77: 436-437. Radford, A.E., H.A. Ahles and C.R. Bell. 1964. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill.

Ralph, R.A. Checklist of the Vascular Plants of the Coastal Plain of Delaware. Unpublished and undated manuscript. University of Delaware Department of Biology.

Richards, C.D., F. Hyland, and L.M. Eastman. 1983. Revised Check-List of the Vascular Plants of Maine. Bulletin of the Josselyn Botanical Society, No. 11.

Scoggan, H.J. 1979. The Flora of Canada - Part 4 Dicotyledoneae to Compositae. National Museum of Natural Sciences. Ottawa.

Segelken, J.G. 1929. The plant ecology of the Hazelwood Botanical Preserve. Ohio Biological Survey Bulletin 21, 4:221-269.

Seymour, F.C. 1969. The flora of New England. Charles E. Tuttle Company. Rutland. Seymour, F.C. 1969. The flora of Vermont. Vermont State Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin No. 660. University of Vermont. Burlington.

Sorrie, B. 1992. County Checklist of Massachusetts Plants. Unpublished manuscript. Strausbaugh, P.D. and E.L. Core. 1977. Flora of West Virginia, 2nd edition. 4 Volumes West Virginia Bul. Morgantown.

Weishaupt, C.G. 1971. Vascular Plants of Ohio. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co. Dubuque. Wherry, T.E., J.M. Fogg and H.A. Wahl. 1979. Atlas of the flora of Pennsylvania. Morris Arboretum. Philadelphia.

Wunderlin, R.P. 1998. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Wunderlin, R.P., B.F. Hansen, and E.L. Bridges. 1996. Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants. Wunderlin, R.P. and B.F. Hansen. 2008. Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants (http://www.plantatlas.usf.edu/). [S. M. Landry and K. N. Campbell (application development), Florida Center for Community Design and Research.] Institute for Systematic Botany, University of South Florida, Tampa.

Voss, E.G. 1996. Michigan Flora. Part III. Dicots (Pyrolaceae-Compositae). Cranbrook Institute of Science Bulletin 61 and University of Michigan Herbarium. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Footnotes

- footnote[*] Back to paragraph For the purposes of this recovery strategy, populations are considered to be independent if separated by one kilometre or more, and that groupings of plants separated by less than one kilometre are considered sub-populations.