Using sheep behaviour to your advantage when designing handling facilities

Learn how you can use sheep behaviour to improve the design of facilities for transporting, handling or catching sheep. This technical information is for Ontario commercial sheep producers.

ISSN 1198-712x, Published September 2014

Introduction

Producers who understand sheep behaviour can use this knowledge to their advantage in all aspects of sheep production and management. Whether setting up and using handling and shearing facilities, moving the flock to a new pasture or catching an individual sheep, taking their behaviour into account ensures the job is completed in an efficient, low-stress manner.

When moving or handling sheep, keep the following aspects of their behaviour in mind:

- sheep do not like to be enclosed in a tight environment and will move into larger areas when possible

- sheep move toward other sheep willingly

- sheep move away from workers and dogs

- sheep have relatively good long-term memories, especially with respect to unpleasant experiences

- if given a choice, sheep prefer to move over flat areas rather than up an incline, and up an incline rather than down an incline

- sheep prefer to move from a darkened area towards a lighter area, but they avoid contrasts in lighting if the change is too dramatic

- sheep flow better through facilities if the same paths and flow directions are used every time

- stationary sheep are motivated to move by the sight of other sheep running away

- sheep will balk or stop moving forward when they see other sheep moving in the opposite direction

- sheep will move faster through a long, narrow pen or area than through a square pen

- sheep move better through the handling chute (race) if they cannot see the operator

- sheep will more willingly move toward an open area than toward what they perceive as a dead end

- very young lambs that become separated from their dams will want to return to the area where they first became separated

- like all livestock, sheep react negatively to loud noises, yelling and barking

- young sheep move through facilities more easily when their first move through is with well-trained older sheep

These observations of sheep behaviour have been established by people who have worked with sheep for many years under a wide range of conditions. Because these behaviours are very predictable, they can be used to the producer's advantage in all aspects of sheep management.

Taking sheep behaviour into account when managing your flock creates positive results:

- greater ease of moving groups

- greater willingness of sheep to enter and be processed in handling facilities

- fewer stress indicators in the animals and handlers

Planning your sheep handling facility

Sheep handling in "make-do" pens is not only hard, difficult work, it is outright unpleasant. As a result, important jobs like vaccinating and deworming are often delayed or not done at all.

Well-designed sheep handling facilities are essential to a successful sheep production operation. Few other investments will create such labour efficiencies and savings. Most producers will only build, or purchase, one handling facility in their lifetime, so planning is essential.

Incorporate existing paddocks, laneways and barnyards into the handling system to allow for ample space when the flock is held in the yards for long periods of time. Sheep need to move smoothly between these areas with a minimum of fuss. To achieve this, a producer needs to understand how good design encourages the sheep and lambs to move ahead through the system without balking, thereby keeping problems for workers to a minimum.

Well-designed facilities are easy to operate, reducing stress, labour and their associated costs.

Operations and factors checklist

To ensure that the handling facility will accommodate all the required jobs, make a complete list of the operations that will be carried out, and plan how these jobs will be done.

A useful checklist includes:

- shearing

- crutching

- sorting

- deworming

- vaccination

- body condition scoring

- pregnancy scanning

- foot trimming

- foot bathing

- weighing

- loading

- sale of sheep

Factors to be taken into consideration include:

- the best location for the facilities

- how large a group the facility will need to handle

- how much labour is available to work in the facility

- whether to modify existing facilities, build new facilities or purchase portable yards

- the costs involved

Facilities design

In simple terms, handling facilities consist of:

- low-density holding areas

- high-density holding areas

- a forcing (or crowding) area

- a drafting (sorting) race

- a handling (working) race

Low-density holding areas

Most producers can use nearby pastures and laneways as their low-density holding areas. These areas need to be secure enough to prevent sheep (particularly lambs) escaping from one area to the next. Consider using net wire fencing with openings no larger than 15 cm by 15 cm, secured to closely spaced posts.

High-density holding areas

High-density holding areas need to be built with medium-to-strong fencing materials. Make the area big enough to hold two sheep in full fleece per square metre. This creates enough room to drive the group into the yards, while leaving space for gates to swing and dogs to work (if dogs are used). It is important to make these areas long and narrow so that it is easy to control groups while they are driven into the forcing (crowding) area. According to recommendations from Australia and New Zealand, these high-density holding areas should be no wider than 10 m. If greater capacity is needed, it is better to lengthen them, rather than making them wider

Forcing (crowding) areas

A combined lead-up race and forcing pen that is 3 m wide has proven very effective in many handling facilities, particularly for large flocks. It allows large groups to be broken down into smaller groups for ease of handling. The drafting and working races will lead off from this area.

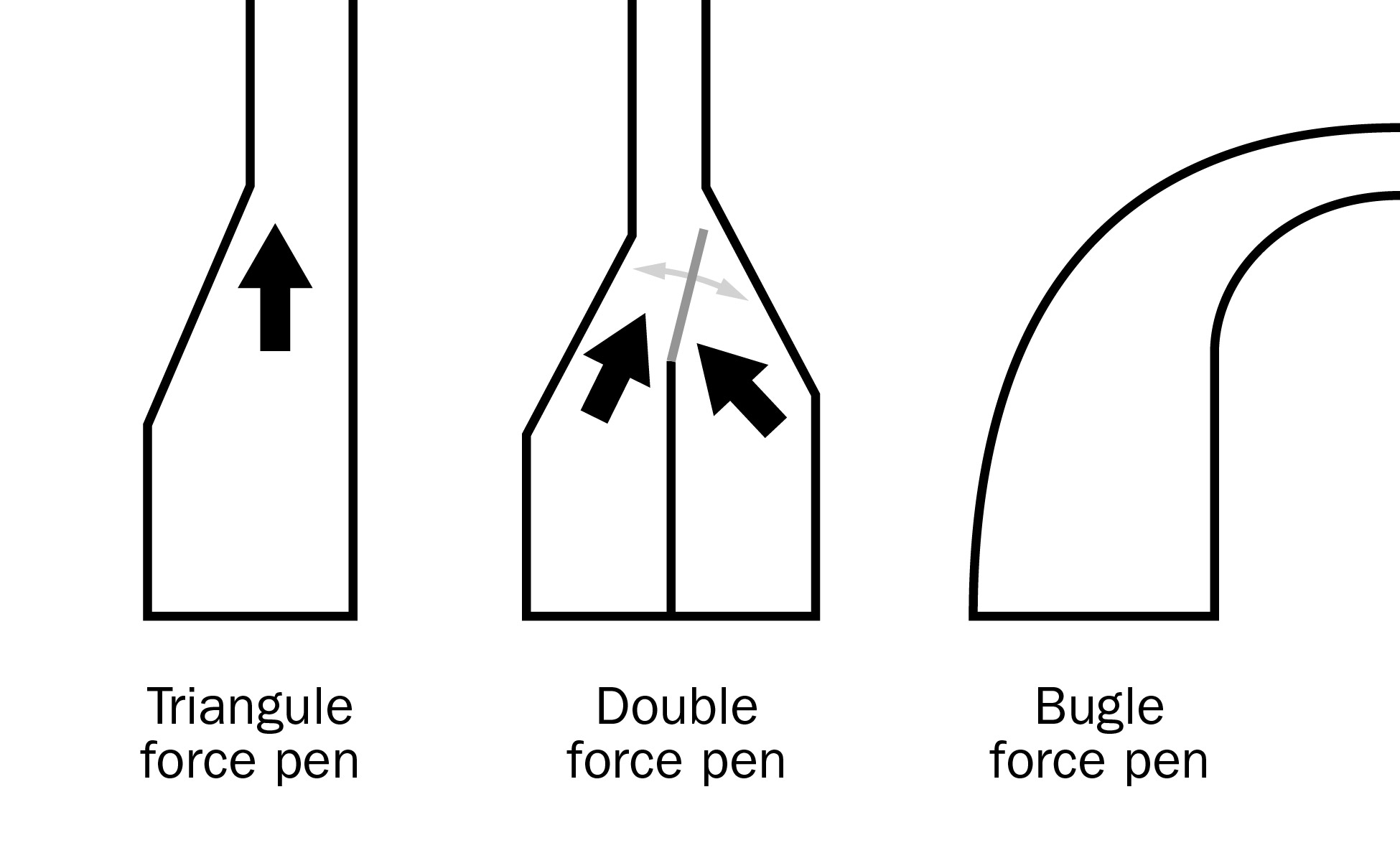

Triangular force pens (sometimes referred to as "V" force pens) are usually used in rectangular facilities and can be built in single or double forms (see Figure 1). In the single-triangular force pen, one side is an extension of the race fence, while the other side flares out at a 30-40 degree angle. The double force pen has two "wing" fences that flare out at similar angles and a central fence with a flip-flop gate at the race entrance to allow sheep to enter from either side.

Figure 1. Examples of successful force pen shapes. Adapted from H.M. Hamilton, 1990 and A. Barber & R. Freeman, 1993.

Curved force pens (bugle) were thought to take advantage of sheep's inclination to follow flock mates that "disappear" around a curve and enable one person to efficiently process the sheep alone. However, more recent research has shown that in 1.5 m wide races, sheep move better through straight races than through curved races. Curved races are only superior when sheep move in single file

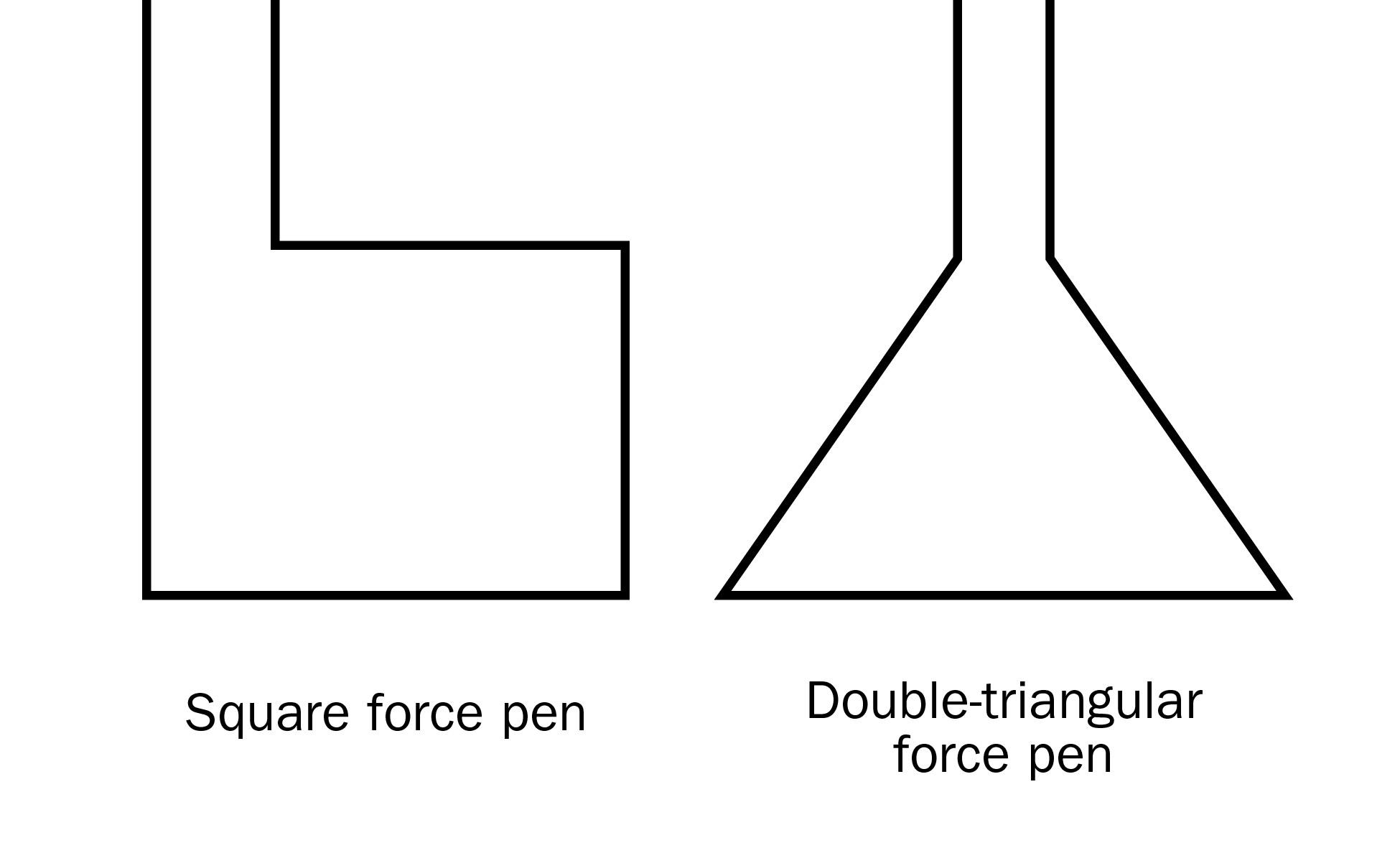

Some force pen designs do not work efficiently and should be avoided. These include square-shaped pens and the double-triangular force pens without a central fence (see Figure 2). The major problem with both of these designs is that sheep can easily avoid entering the race by turning suddenly (ringing) at the race entrance

Sorting/drafting race

For efficient drafting (sorting), the operator needs to be able to easily identify and draft the sheep he or she wishes to separate with a minimum of errors. To do this accurately requires an even flow of sheep. For small flocks, a two-way sort is satisfactory, but in larger-scale sheep operations, a three-way sort, using two gates, may be necessary.

Make the sorting race at least 3 m long, with the exit point showing a clear escape route for the sheep. The race walls need to have solid sides to prevent sheep from being distracted by those on the opposite side and disrupting the continuous flow of sheep. If the race is also used for drenching and vaccinations, consider a slightly wider race or one with adjustable sides.

Figure 2. Examples of unsuccessful force pen shapes. Adapted from H.M. Hamilton, 1990.

The draft gate needs to be at least 1 m long to allow sheep to exit the race easily. Draft gates shorter than this cause sheep (particularly heavy-wooled and pregnant ewes) to jam against the edge of the race when exiting, slowing the flow significantly. There is some debate as to whether the draft gate should be made of solid sheeting or panels that sheep can see through. In Design of Sheep Yards and Sheds, Barber and Freeman

- The oncoming sheep can see the previous sheep moving away from the draft and are more inclined to follow.

- The gates are lighter and therefore quicker and easier to use.

- The gates are less affected by winds blowing across the drafting race.

On the other hand, they also list reasons for using solid draft gates:

- such gates act as a continuation of the drafting race wall, thus directing the sheep into the exit pen

- solid gates prevent horns or legs from getting caught

Handling race

Sheep yards need a multipurpose handling race for drenching, vaccinating and other activities. Most producers in Ontario will opt for this type of race rather than separate handling races and drafting races.

Several different types of handling races can be built:

- a single race 52–64 cm wide where the worker is outside the race

- a single race 70–80 cm wide where the worker is inside the race

- an adjustable-sided race in which the width can be varied between 45 and 80 cm

A suitable handling race is 6–15 m long with sides 85 cm high.

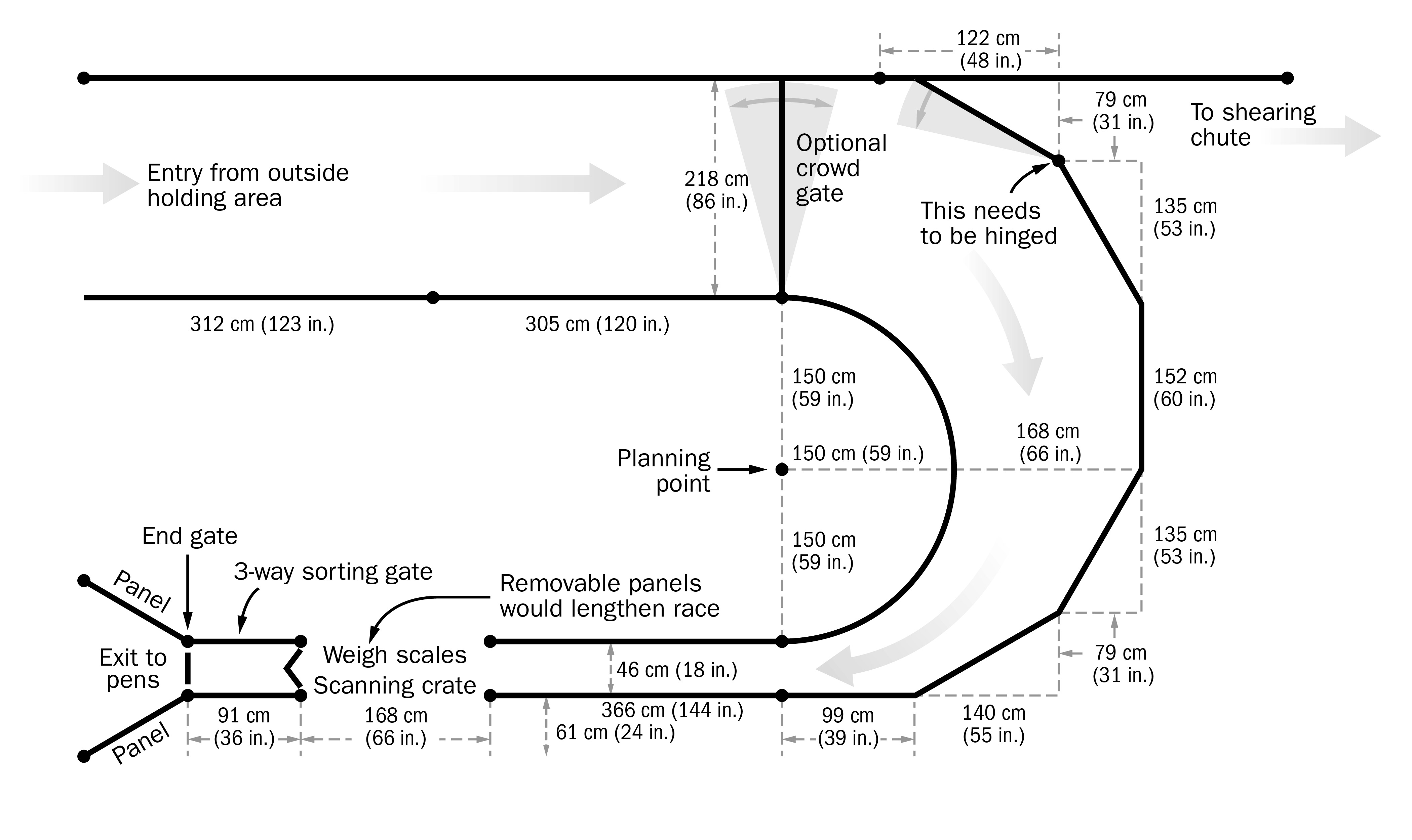

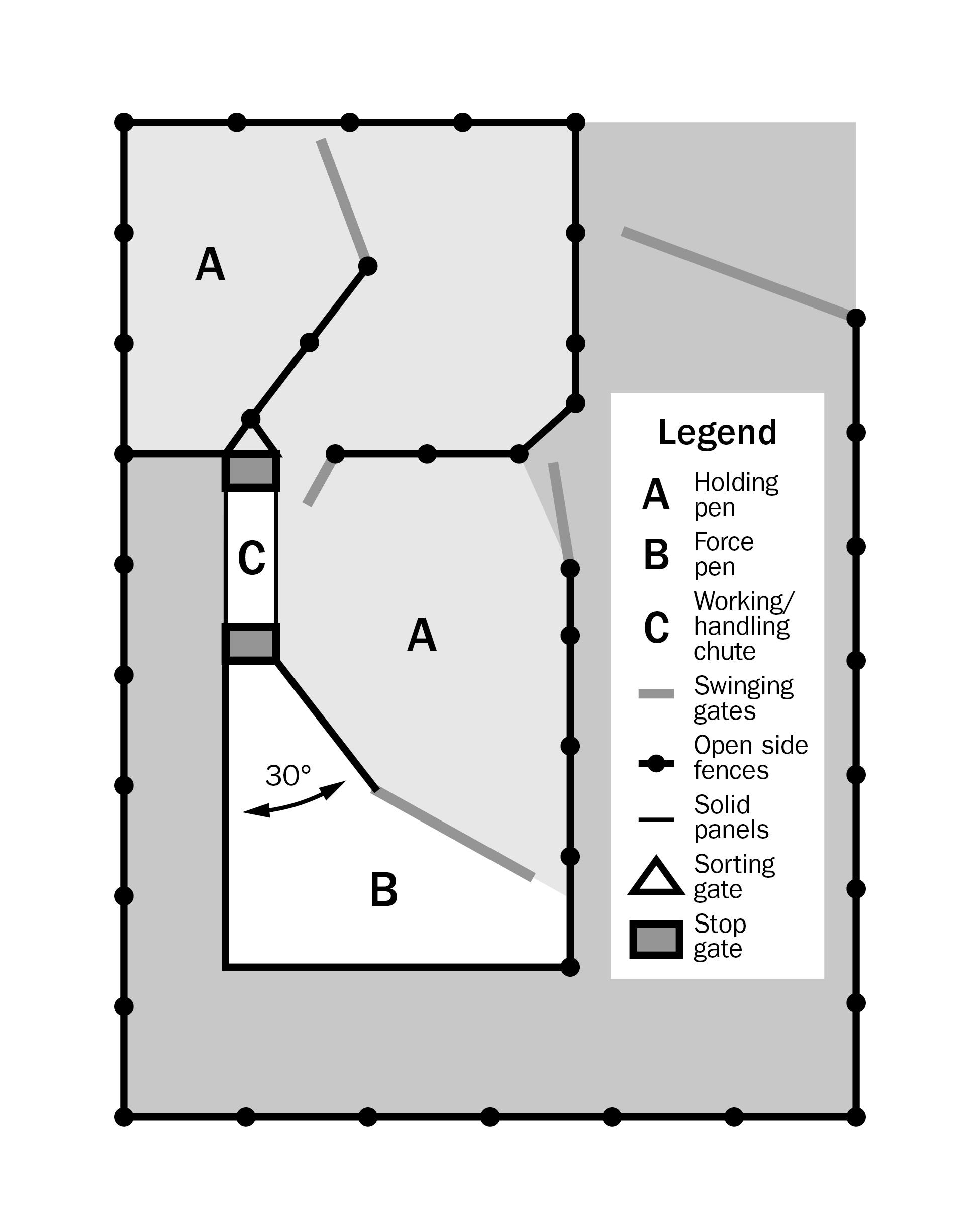

Figures 3 and 4 show basic handling facility layouts for sheep flocks with the key components identified, which can be constructed on farm from common materials. Table 1 provides dimensions for the various components of handling facilities.

Figure 3. A floor plan to construct a bugle. Note the "planning point" from which all measurements start, which should be a survey stake or similar marker that remains in place throughout construction.

Figure 4. Basic handling facility layout for sheep flocks.

Table 1. Yard dimensions in centimetres (100 centimetres = 1 metre)

| Facility | Range (cm) |

|---|---|

| Length | 600–1,200 cm |

| Width (fixed sides) | 60–75 cm |

| Width (adjustable sides) | 45–80 cm |

| Height | 82–90 cm |

| End gate height | 110 cm |

Working race comments:

- Open (see-through) or closed-in (solid) sides

- Keep low if sheep are worked from outside the race

- Sheep usually jump gates rather than sides

| Facility | Range (cm) |

|---|---|

| Length | 300–350 cm |

| Width | 42–48 cm |

| Height | 85–100 cm |

Drafting race comments:

- Closed-in (solid) sides

- Can be tapered at the bottom or of variable width

| Facility | Range (cm) |

|---|---|

| Perimeter fence | 95–110 cm |

| Internal fence | 90–105 cm |

| Facility | Range (cm) |

|---|---|

| Perimeter | 300–400 cm |

| Internal | 200–300 cm |

| Draft | 120–150 cm |

Gates comments:

- Open (see-through) sides

| Facility | Range (cm) |

|---|---|

| Width | 70–100 cm |

| Length | 300–500 cm |

| Height (fixed) | 120 cm |

| Height (variable) | 70–120 cm |

Loading ramp to truck comments:

- Slope not steeper than 1:3

Adapted from Sheepyard and Shearing Shed Design, F. Conroy & P. Hanrahan, 1994.

Labour efficiency of handling facilities

Few sheep producers have adequate handling facilities. Many use the excuse that they are too expensive to purchase or their flock is not big enough to justify the cost of buying or building them. Ask any producer who has a handling facility and their response is they would not raise sheep without one. Why the differing views? The answer is in the savings in labour and associated costs to justify investing in handling facilities.

A survey of Irish sheep farmers showed that those with good handling facilities spent 5.1 hours per livestock unit less across livestock species than those with poor handling facilities (L. Connolly, Irish Farmers' Journal). At six sheep per livestock unit, that equates to savings of 51 minutes per ewe or 85 hours per 100 ewes each year.

For a flock of 1,000 ewes, that is an extra 84.2 days that could be spent doing other things. If you value your time at $15 per hour, a handling facility will easily pay for itself in less than three years. Table 2 offers labour saving dollar values as a function of two flock sizes and different wages to demonstrate this point.

Table 2. Dollar value of labour savings in commercial flocks of varying sizes using differing wage rates and the time saving of labour. Adapted from L. Connolly, Irish Farmers' Journal.

| Labour cost per hour | Labour savings per 100 ewes (85 hr) | Labour savings per 500 ewes (425 hr) |

|---|---|---|

| $10/hr | $850 | $4,250 |

| $15/hr | $1,275 | $6,375 |

| $20/hr | $1,700 | $8,500 |

| $25/hr | $2,125 | $10,625 |

Just as important as the labour savings is the fact that all of those important handling jobs, like vaccination and deworming, get done when they should be done. Sorting for breeding, lambing, weaning and shearing takes very little time with a basic handling facility. In a basic setup, it is not uncommon for a single handler to be able to deworm or vaccinate 150 to 200 ewes per hour and sort 250 to 350 ewes per hour.

In summary, handling facilities:

- save labour

- reduce stress for sheep and handlers

- ensure the jobs get done when they are supposed to be

If you currently do not have a handling facility and plan to continue raising sheep, you need to seriously question why you have not invested in one. Handling facilities are essential if producers expect to find any savings in labour and efficiencies in the management of their sheep.

Conclusion

Handling facilities that are designed and constructed to take advantage of sheep behaviour significantly reduce the stress of handling for the sheep and, just as importantly, for the handler. Sheep move willingly through such facilities, and handlers no longer dread those jobs that previously required brute strength to tackle, catch and move individual sheep.

This fact sheet was originally written by Anita O'Brien, sheep and goat specialist, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA), Kemptville, and updated by Christoph Wand, livestock sustainability specialist, OMAFRA, Guelph.

References

- Barber, A. and R.B. Freeman. 1993. "Design of Sheep Yards and Shearing Sheds." In T. Grandin, ed., Livestock Handling and Transport. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, pp. 147-157.

- Conroy, F. and P. Hanrahan, 1994. Sheepyard and Shearing Shed Design. East Melbourne: Agmedia.

- Hamilton, H.M. 1990. "Yards 'n' Yakka - A summary." In M.F. Casey and G.R. Hamilton, eds, Yards 'n' Yakka: The Sheep Yard and Handling Systems Manual. Perth: Kondinin Group, pp 5-9.

- MidWest Plan Service. 1994. Sheep Housing and Equipment Handbook, 4th ed. Ames, Iowa: MidWest Plan Service.

- Ransom, K. and P. Hanrahan. 1990. "Thorough planning for new yards." In M.F. Casey and G.R. Hamilton, eds, Yards 'n' Yakka: The Sheep Yard and Handling Systems Manual. Perth: Kondinin Group, pp. 10-12.

Accessible image descriptions

Figure 1. Examples of successful force pen shapes.

Diagram showing three shapes for penning that will move sheep from a large opening to a smaller opening. Arrows show the direction of movement from the large area to the smaller area. The single-triangular force pen design is on the left. One side is of this force pen is straight, while the other flares out at an angle. The double-triangular force pen is in the middle. Both sides of this force pen flare out, while a central gate divides the pen in half. The bugle force pen is on the right. Both sides of this pen curve to the right.

Figure 2. Examples of unsuccessful force pen shapes.

Diagram of unsuccessful force pen shapes. A square force pen design is on the left. It is a large square with a small opening at the top left. The double triangle force pen is drawn on the right. It is a very large triangle with a small opening at the top of the triangle.

Figure 3. A floor plan to construct a bugle. Note the "planning point" from which all measurements start, which should be a survey stake or similar marker that remains in place throughout construction.

Diagram of a bugle handling facility. The facility is shaped like a U on its side, with the open part of the U facing the left hand side. The top right portion of the U is wide and the bottom part is small. The animals move from the wide to the narrow part following the sideways U shape.

Figure 4. Basic handling facility layout for sheep flocks.

Diagram of a basic sheep handling facility for sheep flocks. It is an upside down L-shape. Moveable gates allow the holding pens to be divided into small sections to create holding pens and force pens. The animals move from the top of the upside down L, along the side, to the bottom of the upside down L. At the bottom, the animals can then be forced into a smaller area along the side of the L for handling.

Footnotes

- footnote[i] Back to paragraph Conroy, F. and P. Hanrahan, 1994. Sheepyard and Shearing Shed Design. East Melbourne: Agmedia.

- footnote[ii] Back to paragraph Ransom, K. and P. Hanrahan. 1990. "Thorough planning for new yards." In M.F. Casey and G.R. Hamilton, eds, Yards 'n' Yakka: The Sheep Yard and Handling Systems Manual. Perth: Kondinin Group, pp. 10-12.

- footnote[iii] Back to paragraph Hamilton, H.M. 1990. "Yards 'n' Yakka - A summary." In M.F. Casey and G.R. Hamilton, eds, Yards 'n' Yakka: The Sheep Yard and Handling Systems Manual. Perth: Kondinin Group, pp 5-9.

- footnote[iv] Back to paragraph Barber, A. and R.B. Freeman. 1993. "Design of Sheep Yards and Shearing Sheds." In T. Grandin, ed., Livestock Handling and Transport. Wallingford, UK: CAB International, pp. 147-157.