Wetland conservation strategy

Learn about the provincial vision, goals and outcomes for Ontario’s wetlands and the actions that we will take until 2030 to improve wetland conservation.

Natural Resources Conservation Policy Branch

2017

ISBN 978-1-4606-9985-0 (Print)

ISBN 978-1-4606-9987-4 (PDF)

ISBN 978-1-4606-9986-7 (HTML)

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2017

How to cite this document:

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2017. A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario 2017–2030. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Toronto, ON.

Message from the Minister

Whether you're an angler or birder who loves marshes and swamps, or a person who would never step foot in a bog, wetlands matter to you. They're vital to the health of our province, giving us clean and abundant water, protecting us from flooding, and reducing the effects of climate change.

However, wetlands are sensitive ecosystems - and they're under pressure from land conversion, invasive species, pollution and climate change. Without action, our wetlands will be severely impacted, with many likely to disappear in the face of these significant threats.

The conservation of wetlands and the biodiversity they support are an important part of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry’s mandate. That’s why Ontario is adopting this new Strategy with ambitious conservation targets to help stop the loss of wetlands and restore wetlands in areas where significant losses have occurred.

This Strategy builds on our government’s strong commitment to wetland conservation and our existing efforts, actions and programs. It sets out the steps government will take to support wetland conservation.

This document has been shaped by many voices, and I want to thank all who contributed their valuable perspectives. Our ongoing collaboration and our important partnerships will be central to the Strategy’s success.

I encourage you to read the Strategy and consider how we can all work together to conserve, protect, and restore our precious wetlands and Ontario’s rich biodiversity.

Hon. Kathryn McGarry

Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry

Executive summary

Wetlands are among the most robust and diverse habitats on Earth and form an important part of Ontario’s landscape. From the swamps and marshes in the southern part of the province to the vast peatlands in the north, wetlands play a vital role in supporting Ontario’s rich biodiversity and providing essential ecosystem services on which Ontarians depend for health and well-being.

Building on over 30 years of positive achievements in conserving Ontario’s wetlands, A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario is a framework to guide the future of wetland conservation across the province. The intent of the Strategy is to establish a common focus to conserve wetlands, so that Ontario can achieve greater success in a more efficient and effective manner.

The Strategy itself includes two sections. The first section covers what wetlands are, the state of wetlands in Ontario, and the variety of legislation, regulations, policies, guidelines, programs and partnerships that support wetland conservation across the province. The second section describes the new wetland conservation strategy, including a clear vision, goals and desired outcomes, and a series of actions the Ontario government will undertake.

This strategy is supported by objectives that are aligned with four strategic directions that reflect critical components required to conserve Ontario’s wetlands. These include awareness, knowledge, partnership and conservation.

A comprehensive suite of actions that the Ontario government is taking, or will take, is a critical part of the Strategy. These actions include improving Ontario’s wetland inventory and mapping, as a cornerstone of our Strategy. Other key actions include developing policies and tools to prevent the loss of Ontario’s wetlands, and improving evaluation of the significance of Ontario’s wetlands.

Finally, the success of the Strategy will be measured through two overarching targets concerning wetland area and functions. These targets will use 2010 as a baseline:

- By 2025, the net loss of wetland area and function is halted where wetland loss has been the greatest.

- By 2030, a net gain in wetland area and function is achieved where wetland loss has been the greatest.

The Ontario government commits to developing performance measures and reporting to the public on progress in implementing the actions as well as progress towards achieving the targets. Progress will be monitored and assessed on a five-year time frame beginning in 2020 to encourage completion of action that will ultimately lead to improved conservation of wetlands across the province.

Introduction

Forming the connection between land and water, wetlands are among the most productive and diverse habitats on Earth. Ontario’s wetlands are biodiversity hotspots, serving as an important habitat to an array of plants, birds, insects, amphibians, fish and other animals, including many species at risk. Wetlands also provide Ontarians with a variety of valuable ecosystem services that create economic benefits and contribute to a high quality of life for people in this province. These include providing clean and abundant water, flood and erosion mitigation, climate moderation, recreational opportunities and other important social, cultural and spiritual benefits.

Building on over 30 years of progressive wetland policy and partnerships, A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario provides a coordinating framework to guide wetland conservation across the province. The intent is to provide both the government and people of Ontario with a common focus to conserve wetlands and a path forward so that we can achieve greater success in a more efficient and effective manner. The Strategy will serve as a launching point for new, innovative conservation commitments and actions that can protect Ontario’s wetlands.

This Strategy includes strategic directions, goals and desired outcomes, and actions the government will undertake by 2030 to improve wetlands in Ontario. This includes increasing knowledge and understanding of wetland ecosystems and raising awareness about the importance of wetlands. It also includes building strong and effective wetland policies, encouraging cooperation at all levels of government and supporting strategic partnerships in a shared responsibility for conserving wetlands. Taken together, these actions will help Ontario to first stop the loss of wetlands and then restore wetlands where they have been lost.

How we got here

In 2014, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) was given a mandate to work with other ministries, municipalities and partners in the review of Ontario’s broad wetland conservation framework and the identification of opportunities to strengthen policies and stop the net loss of wetlands. This mandate was renewed in 2016, when MNRF was asked to create a strategy for Ontario’s wetlands by 2017, with the goal of stopping the net loss of wetlands. To achieve this mandate, the MNRF has developed A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario that will help to improve wetland conservation and achieve a net gain in wetland area and function where wetland loss has been the greatest.

The development of this Strategy mirrors the preparation of similar policy documents across Ontario, Canada and the world, where there has been a realization that investing in wetland conservation is essential to ensuring quality of life for people and resilient habitats for wildlife - now and in the future.

Through a series of engagement opportunities, people across Ontario expressed their concern about wetland loss in the province and loss of the important ecosystem services they provide. Ontarians also discussed the different issues and opportunities for wetland conservation in the different parts of the province, highlighting that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to wetland conservation. Finally, Ontarians expressed strong support for the development of this Strategy, as well as the strategic directions identified.

Ontario’s wetlands

Ontario is fortunate to be home to more than 330,000 square kilometres of wetlands. In fact, Ontario currently accounts for about 25 per cent of all the wetlands in Canada and 6 per cent of all the wetlands in the world. This places Ontario in a unique position and creates a responsibility to protect these wetlands for current and future generations.

Wetlands are lands that are seasonally or permanently covered by shallow water as well as lands where the water table is close to or at the surface. In either case, the presence of abundant water has caused the formation of hydric (waterlogged) soils and has favoured the dominance of either hydrophytic (water-loving) or water-tolerant plants. The four major types of wetlands are swamps, marshes, bogs and fens. They are often transitional habitats, forming a connection between aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems.

Wetlands can range in size from very small, only a few square metres, to exceptionally large, covering hundreds of square kilometres. Wetlands may be isolated, occur along the edges of lakes and rivers, or exist in conjunction with other natural areas such as woodlands, shrublands and native grasslands. Sometimes, closely spaced wetlands related in a functional way can also form what is known as a wetland complex.

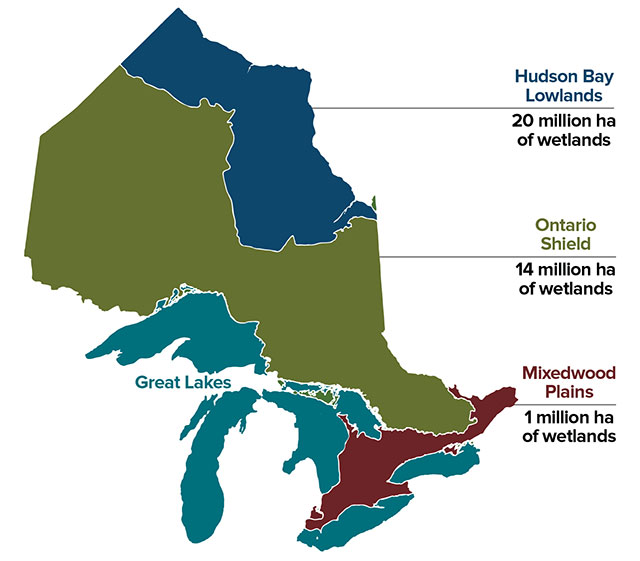

Climate, geology and ecosystems differ throughout the province, as do the number, size, type and distribution of wetlands (figure 1). In Ontario, the majority of wetlands are found in northern Ontario, with the Hudson Bay Lowlands Ecozone accounting for 20,000,000 hectares or about 57 per cent of Ontario’s wetlands (Ontario Biodiversity Council 2015). An estimated 10,000 square kilometers or 1,000,000 hectares of wetlands exist in southern Ontario, with an average size of 25 hectares.

Figure 1: Ontario’s ecozones and associated land cover

Make a custom map of wetlands in your area

Wetlands characterized by accumulations of peat greater than 40 centimetres are also known as peatlands. Peat is formed where dead plant material is conserved over thousands of years due to a combination of permanent water saturation, low oxygen levels and low temperatures. High water levels in peatlands limit peat oxidation, thereby minimizing the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — an important service in mitigating the effects of climate change. In fact, it is estimated that peatlands in the Far North of Ontario annually sequester an amount of carbon equal to about one third of Ontario’s total carbon emissions (the Far North Science Advisory Panel 2010). Changes in water levels from the effects of climate change may alter the ability of Ontario’s peatlands to store and sequester carbon and provide important ecosystem services.

The wetlands of the Hudson Bay Lowlands in the Far North of Ontario are among the most productive subarctic wetland habitats in the world. They support a significant global migratory flyway for waterfowl and shorebirds in addition to being the densest carbon storage and water-retention ecosystems in Ontario.

Ontario is also home to a unique kind of wetland known as a Great Lakes coastal wetland. Great Lakes coastal wetlands are located in close proximity to the Great Lakes coastline and are connected by surface water to a Great Lakes system lake or channel. These wetlands are among the region’s most ecologically valuable and productive habitats, providing a number of essential ecosystem services to Ontarians. This includes improving Great Lakes water quality by filtering pollutants and sediment; storing and cycling nutrients and organic material from land into the aquatic food web; and reducing flooding and erosion during periods of high water. These wetlands also provide an important habitat for wildlife, including a migratory habitat for waterfowl, and breeding/spawning and nursery habitats for many Great Lakes species.

Figure 2: Wetland ecosystem services

-

Water quality improvement

-

Wildlife habitat

-

Fish habitat

-

Flood mitigation

-

Erosion reduction

-

Cultural and spiritual significance

-

Climate change mitigation

-

Groundwater recharge and discharge

-

Recreation and tourism

-

Source of food and medicines

Current status and threats

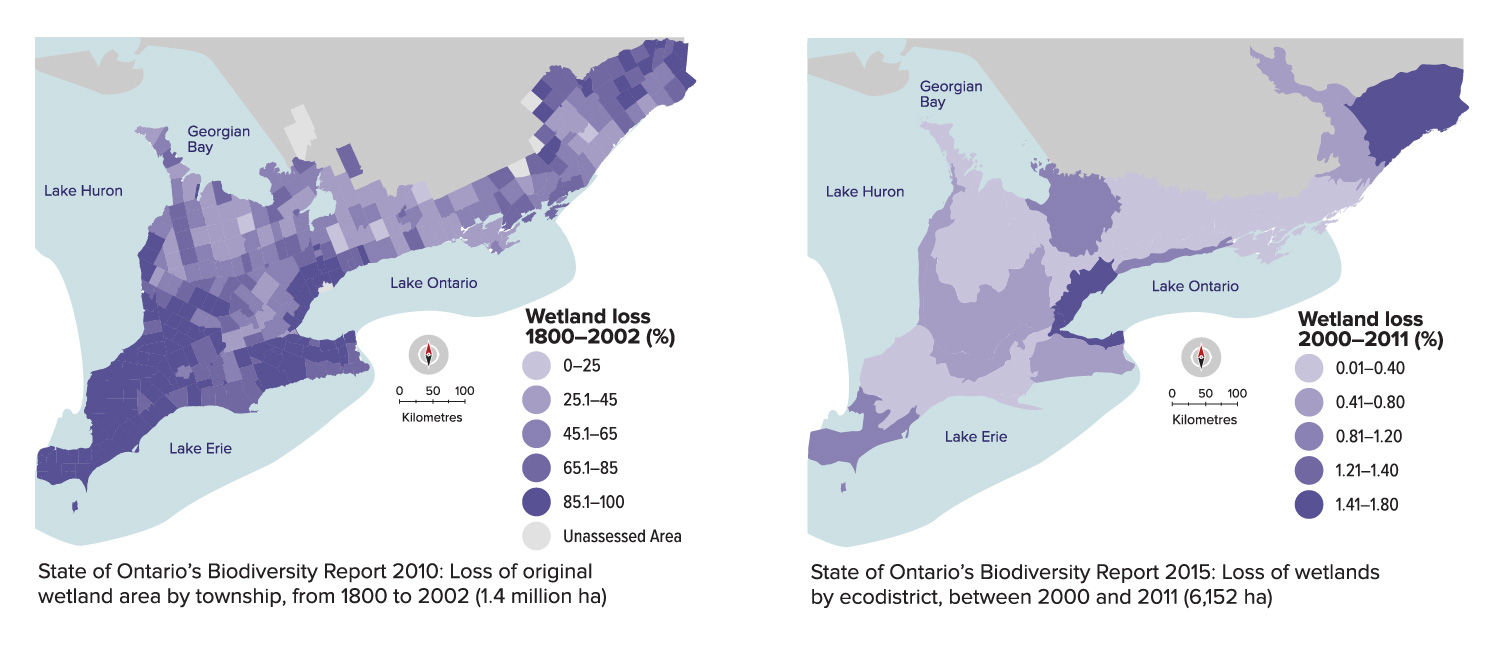

The province of Ontario was once characterized as a vast sea of contiguous forest, lakes, rivers and wetlands with scattered islands of open spaces, grasslands, and prairies. However, since the time of European settlement, the landscape has undergone repeated change in response to various economic and resource-use opportunities. In the southern portion of the province (Mixedwood Plains Ecozone), a thriving economy and fast-growing human population has resulted in many wetlands being drained or filled to accommodate infrastructure and agricultural, industrial and residential land uses. Estimates suggest that 68 per cent of the wetlands originally present in southern Ontario were lost by the early 1980s (OBC 2010). An additional 4 per cent has been lost since this time (OBC 2015) (figure 3); however, a recent assessment has shown that the rate of loss appears to be decreasing (OBC 2015). While land conversion is the primary cause of wetland loss in southern Ontario, pollution, invasive species, alteration to natural water levels and climate change also pose serious threats.

Figure 3. Wetland loss in the Mixedwood Plains Ecozone

Ontario’s Great Lakes coastal wetlands have experienced similar historical losses and degradation over the past 200 years. It is estimated that by 1984, 35 per cent of wetlands along the Canadian shores of Lakes Erie, Ontario, and St. Clair had been lost, with the greatest losses occurring between Toronto and the Niagara River. Loss and degradation continue today, largely resulting from shoreline alteration, water level control, nutrient and sediment loading, invasive species, dredging, and development. Upstream land use practices also have an impact, particularly through runoff from urban and industrial development, agricultural lands and impervious surfaces.

Despite localized loss and degradation, wetlands in the northern part of Ontario (Hudson Bay Lowlands and Ontario Shield ecozones) remain largely intact. Threats to northern Ontario wetlands are quite different from those in southern Ontario. Although urban development and drainage for agriculture are a concern in the more settled regions of northern Ontario, pressures from activities such as mining, hydro-electric and alternative energy development, and transportation infrastructure are more common. Longer-term, climate change is expected to have a significant impact on wetlands in northern Ontario, particularly on peatlands in the Far North. Increases or decreases in water levels as a consequence of climate change may result in changes in the extent and composition of current wetlands and alter the ability of these ecosystems to store and sequester carbon.

It is important to recognize that wetlands are often exposed to multiple threats at the same time, and in many cases, these threats are closely linked. These combined effects from multiple threats have a far greater negative outcome and lead to greater wetland loss or degradation than any single threat on its own. For example, the combined impact of climate change on stream flows, coupled with increased water usage to support population growth, or increased habitat fragmentation in urban areas, will have a greater impact than any of these pressures on their own.

Ontario’s current wetland policies

Ontario’s first public discussions regarding the development of a wetland policy occurred more than 30 years ago, when the government released a discussion paper titled Towards a Wetland Policy for Ontario. The result of that effort was a wetland policy issued by the Ontario government in 1984 titled Guidelines for Wetlands Management in Ontario and later on, the 1992 Wetland Policy Statement — a precursor to what are now the wetland-related natural heritage policies under the Provincial Policy Statement.

Since this time, pressures on Ontario’s wetlands have changed and evolved, and wetland policy has followed suit. Currently, wetlands are managed through a variety of policies that include over 20 different pieces of legislation administered and/or implemented by five provincial ministries, two federal departments, a provincial agency (Niagara Escarpment Commission), 36 conservation authorities and 444 municipalities. Some of these statutes enable aspects of natural resource or natural heritage conservation and management, which can include wetlands, while others explicitly restrict certain land uses or activities within them.

Tables 1A and 1B outline the major legislation and policy instruments currently in place that influence and guide wetland conservation in Ontario. In addition to the legislation and policy described, several other provincial statutes require consideration of wetlands when making decisions (e.g. Aggregate Resources Act) or influence wetlands in some way (e.g. Drainage Act). Others recognize that wetlands are part of recharge and discharge areas, which are also important to protecting sources of drinking water in Ontario (e.g. wetlands mapped in source protection plans, including local assessment reports prepared under the Clean Water Act). Several federal policies and statutes also contribute to wetland conservation in Ontario (e.g. Fisheries Act, Federal Policy on Wetlands).

Table 1A: Provincial instruments that restrict certain activities in wetlands

| Policy Instrument | Link to Wetland Conservation and Management |

|---|---|

| Planning Act, Provincial Policy Statement 2014 | Protects provincially significant wetlands and coastal wetlands from development and site alteration depending on where they are located within the province. Wetlands can also be identified within natural heritage systems, which are networks of core areas and linkages that support biodiversity, and can be identified as part of water resource systems or significant cultural landscapes. |

| Niagara Escarpment Planning and Development Act & Plan | Protects wetlands located within the Niagara Escarpment planning area from development. |

| Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Act, 2001 & Plan | Protects wetlands located within the Oak Ridges Moraine planning area from development. |

| Greenbelt Act, 2005 & Plan | Protects wetlands in the area designated as Protected Countryside within the Greenbelt Plan in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. |

| Places to Grow Act, 2005 & Growth Plan | Protects wetlands located within the Growth Plan planning areas, outside of settlement areas, from development. |

| Lake Simcoe Protection Act, 2008 & Plan | Protects wetlands located in the Lake Simcoe watershed from development. |

| Conservation Authorities Act Regulations | Regulate development in and around wetlands for effects on the control of natural hazards (e.g. flooding) as well as activities that may interfere with a wetland. |

| Renewable Energy Approvals Regulation (under the Environmental Protection Act) | Prohibits most activities associated with renewable energy projects from locating directly within provincially significant wetlands in southern Ontario and significant coastal wetlands, while enabling a risk-based approach to minor encroachments from infrastructure. |

| Crown Forest Sustainability Act, 1994 & Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Scales (2010) | Provides for the long-term health of Crown Forests and for forest sustainability. Forest management guides used during the planning and implementation of operations and construction of roads contain mandatory direction and best management practices designed to protect the integrity of aquatic habitats that include permanent and seasonal wetlands (inclusive of those recognized as provincially significant). |

| Public Lands Act and enabling processes | Guides the administration and disposition of Crown land resources in Ontario and Crown land use planning south of the Far North. Dispositions (sale and issuance of land use occupational authority) and issuing of permits (e.g. work permits for aquatic vegetation removal) are subject to screening under the Class Environmental Assessment for MNR Resource Stewardship and Facility Development Projects. Crown land use planning applies land use designations and develops area-specific land use direction that incorporate key social, economic, cultural and ecological values, including consideration and protection of wetlands. |

| Lakes and Rivers Improvement Act | Requires approval for the construction, alteration and operation of water control structures, some of which may be used to restore or enhance wetland habitat. Potential impacts and associated mitigation measures may be considered as part of the approvals process. |

| Water Resources Act | Prohibits discharge of polluting material that may impair the quality of water, which encompasses impacts on aquatic life, including those within wetlands. |

Table 1B: Provincial instruments that facilitate wetlands conservation

| Policy Instrument | Link to Wetland Conservation and Management |

|---|---|

| Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015 | Enables establishment of wetland targets and supporting plans to prevent net loss of wetlands, as well as regulatory tools and initiatives to support shoreline and coastal protection and restoration. |

| Far North Act, 2010 | Establishes objectives for community based land use planning, including the protection of 225,000 square kilometres of land in the Far North of Ontario, and the maintenance of biological diversity, ecological processes and functions, such as the storage and sequestration of carbon. |

| Endangered Species Act, 2007 | Prohibits the damage and destruction of the habitat of endangered and threatened species, some of which carry out life processes in wetlands. |

| Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act, 2006 | Permanently protects a system of provincial parks and conservation reserves that includes ecosystems representative of all of Ontario’s natural regions and provincially significant elements of Ontario’s natural and cultural heritage, including wetlands. |

| Municipal Act, 2001 | Enables a municipality to pass by-laws to restrict tree cutting (e.g. in swamps), placing or dumping of fill, and removing topsoil (e.g. defined to include peat). |

| Assessment Act | Sets out eligibility criteria for lands that can receive property tax exemptions under the Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program and the Managed Forest Tax Incentive Program — many of these lands contain wetlands. |

| Conservation Land Act | Enables the protection of natural areas, including wetlands, by establishing conservation easements on private land. |

| Environmental Assessment Act | Requires an assessment of any major public sector and some private sector undertakings that may have a significant environmental impact. The process requires public bodies (such as the Ontario Ministry of Transportation) and some private agencies to make design decisions to avoid impacts and to mitigate where avoidance is not possible. |

| Invasive Species Act, 2015 | Establishes an enabling regulatory framework to prevent, detect, control and eradicate invasive species across the province. |

Wetlands and land use planning in Ontario

Wetland conservation in Ontario is largely implemented through land use planning. Whether through development of municipal official plans and municipal decisions on land use plans, community based land use plans or resource management planning for Ontario’s Crown land, conserving Ontario’s wetlands is an important consideration. Wetland conservation should also be integrated into watershed planning, water management and climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Planning Act: The Provincial Policy Statement

The Provincial Policy Statement 2014 (PPS) provides policy direction on matters of provincial interest related to land use planning and development on private lands. The PPS is issued under section 3 of the Planning Act and all decisions affecting land use planning matters "shall be consistent with" the PPS. The PPS applies province-wide, and municipalities rely on the PPS to develop their official plans and to guide and inform decisions on other planning matters.

The PPS prohibits development and site alteration in all provincially significant wetlands (PSWs) throughout much of southern and central Ontario, and provincially significant Great Lakes coastal wetlands anywhere in the province. Development and site alteration is prohibited on lands adjacent to PSWs, in PSWs in northern Ontario, and in non-PSW coastal wetlands in central and southern Ontario, unless it has been demonstrated that there will be no negative impacts on the wetlands or their ecological functions. Wetlands can also be identified within natural heritage systems, which are networks of core areas and linkages that support biodiversity, and as part of water resource systems or significant cultural heritage landscapes.

Ontario’s 36 conservation authorities support municipalities in ensuring that official plans and other planning decisions are consistent with the policy direction contained within the PPS. All conservation authorities review municipal planning policy and applications for consistency with the natural hazard policies of the PPS, and many municipalities rely on conservation authorities to review natural heritage evaluations undertaken in support of Planning Act applications.

In addition to the PPS, there are a number of regional land use plans that contain protections for wetlands, including the Niagara Escarpment Plan, the Oak Ridges Moraine Conservation Plan, the Greenbelt Plan and Growth Plan, some of which go above and beyond the protections afforded under the PPS. The Growth Plan encourages planning authorities to identify natural heritage features and areas, including wetlands, which complement, link, or enhance natural systems. Further, the province is in the process of developing a Natural Heritage System (NHS) for the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) under the Growth Plan, which will include many wetlands. As well, there are enhanced requirements for municipal official plans to identify water resource systems and undertake watershed planning to inform decisions. This will provide for the long-term protection of water quality and quantity.

In addition to land use approvals under the Planning Act, an environmental assessment process may be applied to new infrastructure and modifications to existing infrastructure under applicable legislation. The process requires public bodies and some private agencies to make design decisions to avoid impacts to the environment and to mitigate where avoidance is not possible.

Far North Act: Community based land use planning

In 2008, the Ontario government announced that it would work with First Nations to protect more than half of the Far North Boreal region. Under the Far North Land Use Planning Initiative, Ontario is working with local First Nations to prepare land use plans that clarify where development can occur and where land is dedicated to protection.

The Far North Act, 2010 puts a requirement for First Nations approval of land use plans on public lands into law for the first time in Ontario’s history. The Act sets out a land use planning process in which joint First Nations-Ontario planning teams prepare and approve land use plans to identify lands in the Far North that will be designated as lands that are protected, those that are open for sustainable economic development, and how such land and water will be managed into the future. The Far North Act also provides for a Far North Land Use Strategy which would assist in the preparation of land use plans and guide the integration of matters beyond the scale of individual plans.

As of 2016, five First Nation communities had completed community based land use plans (Pikangikum, Cat Lake, Slate Falls, Pauingassi and Little Grand Rapids) and all but a few of the remaining First Nation communities are engaged with the MNRF in the various stages of preparing a land use plan.

Public Lands Act: Crown land use planning

The MNRF has the lead role for the care and management of Ontario’s Crown land and water covering about 87 per cent of the province. Many of the province’s significant wetlands are located on provincial Crown lands.

South of the Far North, the MNRF's Crown land use planning system is enabled under the Public Lands Act. Through a variety of planning processes undertaken over the past 40 years, land use policy has been developed for Crown lands south of the Far North that provides broad land use direction for resource and management planning as well as establishment of a protected areas system.

Land use planning processes are open and transparent, providing the public, First Nation and Métis Peoples, and stakeholders with the opportunity to participate in and influence land use decisions. Cultural, social, economic and ecological values, including provincially significant wetlands, are considered during Crown land use planning activities.

Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act: Planning and Management of Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves

The MNRF is responsible for the planning and management of provincial parks and conservation reserves, which comprise about 9 per cent of Ontario. These protected areas are identified to protect important natural and cultural features and are planned and managed to maintain their ecological integrity. They also provide opportunities for the public to experience and learn about the values of wetlands, and places for research to improve our knowledge of these critical ecosystems.

Many wetlands have been protected within Ontario’s system of provincial parks and conservation reserves. For example, 6.4 per cent of Great Lakes coastal wetlands in the province are within the boundaries of provincial parks and conservation reserves.

International cooperation for wetland conservation

Wetlands are recognized globally as a resource of great ecological, economic, social, cultural heritage and recreational value. Numerous conventions, agreements and collaborative partnerships have been developed to help ensure that wetlands and the important functions they provide are conserved and sustained for future generations. These initiatives operate at various scales, involve both government and non-government organizations, and often seek to coordinate conservation action across provincial, national and continental boundaries.

Ramsar Convention: In 1971, a multi-national global treaty, called the Ramsar Convention, was adopted in the Iranian city of Ramsar to provide a framework for national action and international cooperation for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources. The treaty was negotiated in the 1960s by countries and non-governmental organizations concerned about increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitats for migratory birds. The Ramsar Convention has long recognized the importance of the cultural significance of wetlands in achieving their conservation and sustainable use. A key commitment of the Ramsar Convention is to identify globally important wetlands on the List of Wetlands of International Importance. There are eight Ramsar Wetlands of International Importance designated in Ontario, including Long Point National Wildlife Area, St. Clair National Wildlife Area, Southern James Bay, Polar Bear Provincial Park, Point Pelee National Park, Mer Bleue Conservation Area, Matchedash Bay Provincial Wildlife Area and Minesing Swamp. Together, these important wetlands cover an area of 56,419 hectares.

Convention on Biological Diversity: Established in 1992, this convention provides a broad framework for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity. Nationally, the Convention on Biological Diversity is supported by the Canadian Biodiversity Strategy and the recently established Canadian 2020 Biodiversity Goals and Targets. On a provincial level, Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy 2011 and Biodiversity: It’s in Our Nature — Ontario Government Plan to Conserve Biodiversity 2012-2020 contribute to Canada’s actions to conserve biodiversity and both include actions to improve wetland conservation.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Established in 1992, The Climate Change Convention aims to address problems resulting from the increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere. Wetlands are likely to be affected by the expected changes in hydrology associated with climate change. For Canada and Ontario, major responses to obligations under the Climate Change Convention are addressed through Canada’s Way Forward on Climate Change and Ontario’s Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan. Wetland conservation is identified as a key action in mitigating carbon emissions and the impacts of changing climatic conditions.

Eastern Habitat Joint Venture (EHJV): This joint venture is a collaborative partnership of government and non-government organizations working together across eastern Canada to conserve continentally significant wetlands and other habitats that are important to migratory birds. Since 1986, the EHJV has helped to implement habitat conservation programs — such as wetland securement, restoration, stewardship and management — that support continental waterfowl objectives identified under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP). The EHJV, one of more than 20 joint ventures in North America, spans the six easternmost Canadian provinces. Each province has established its own provincial partnership to implement activities that support the joint ventures as a whole. In Ontario, this partnership is known as the Ontario EHJV. Ontario EHJV partners include the Government of Canada, the Government of Ontario, Ducks Unlimited Canada, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and Bird Studies Canada.

Conserving wetlands in the Great Lakes basin

It has long been recognized that wetlands play an important role in maintaining the water quality and ecosystem integrity of the Great Lakes basin. Several initiatives have developed over the last 40 years that recognize the important role of wetlands in the Great Lakes, identify the threats that wetlands face in this region, and seek to implement actions to protect and restore wetlands across the basin. Many of these initiatives involve close inter-jurisdictional cooperation and a commitment to work together. These initiatives include:

Canada-U.S. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement (GLWQA):

This bi-national agreement has a vision to restore and maintain the chemical, physical and biological integrity of the waters of the Great Lakes. The amended agreement (2012) includes an objective to support healthy and productive wetlands and other habitats to sustain resilient populations of native species.

Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health, 2014 (COA):

This agreement outlines how the governments of Canada and Ontario will work together to restore, protect and conserve Great Lakes water quality and ecosystem health. The 2014 COA includes a priority focusing on restoring, protecting and conserving wetlands, beaches and other coastal areas of the Great Lakes.

Lakewide Action and Management Plans (LAMPs):

Bi-national action plans created to help restore and protect each Great Lake, LAMPs are used to assess the status of each Great Lake. These action plans also outline how federal, provincial and state agencies are working together to implement management actions that address lake-wide environmental issues, including wetland conservation.

Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy, 2012:

This Strategy provides a roadmap for how Ontario ministries are taking action to protect the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence River basin. Now enshrined as a living document under the Great Lakes Protection Act, 2015, it is designed to focus provincial actions across ministries, and to enhance collaboration and engagement with the broader Great Lakes community. One of the six goals of the Strategy is to improve wetlands, beaches, shorelines and coastal areas.

Great Lakes Wetland Conservation Action Plan (GLWCAP):

Prepared by government and non-government organizations in 1994, this action plan outlines a framework for wetland conservation in the Great Lakes basin through eight implementation strategies. The plan is coordinated by a team of federal, provincial and non-governmental organizations, and actions are updated regularly.

Great Lakes Water Level Management:

Established under the Boundary Waters Treaty in 1909, the International Joint Commission (IJC) is an advisor to the governments of Canada and the U.S. on implementation of the GLWQA and helps to manage Great Lakes waters by regulating boundary water uses, investigating trans-boundary issues and recommending solutions. The Ontario government participates in the IJC's initiatives, including investigating the impacts of water level regulation on Great Lakes coastal wetlands.

Partners in wetland conservation

Wetland conservation efforts can be significantly strengthened through the support of citizens and organizations that can help to monitor, maintain and enhance wetlands across the province. Such efforts are an important contribution to the continual, on-the-ground work of wetland conservation and building awareness and appreciation for these sites among the broader community.

First Nation and Métis Peoples and communities are important partners in wetland management. The Ontario government recognizes that First Nation and Métis communities are involved in managing and using wetlands sustainably, and that local and traditional ecological knowledge can substantially contribute to effective wetland management practices. The livelihoods, food security and cultural heritage of First Nation and Métis Peoples are often connected to wetlands. This unique relationship with the land and its resources pre-dates the existence of the province and continues to be of central importance in First Nation and Métis communities across Ontario today.

Private landowners are important partners in the conservation of wetlands, particularly in southern Ontario, where the majority of wetlands are privately owned. Private landowners can conduct stewardship projects in conjunction with provincial and federal government agencies, municipalities, conservation authorities and environmental organizations.

Municipal governments recognize the importance of wetlands, particularly for the ecosystem services these lands provide to their communities. Municipalities play an important role in wetland conservation, particularly through the development of municipal official plans and bylaws that can protect wetland environments within their jurisdiction.

The agricultural community are significant land owners in Ontario and work to balance the need for sustainable food production with maintaining ecosystem services provided by natural heritage and farmed land. Many farmers are actively engaged in conserving wetlands on their lands.

Conservation authorities (CAs) have a long legacy of wetland conservation and restoration throughout their watersheds. CAs are collectively one of the largest landowners in Ontario providing protection to many wetland areas. CAs also administer regulations related to development in their jurisdiction. This includes regulating development within natural hazard areas such as floodplains, shorelines and wetlands as well as regulating any alterations to a watercourse or interference with a wetland.

Environmental organizations such as Ducks Unlimited Canada, the Nature Conservancy of Canada, and local land trusts (among others) are actively involved in wetland securement and restoration efforts through land acquisition projects, monitoring programs, public outreach, research, education, and more.

Cultural heritage organizations, such as historical societies, community heritage groups, and other non-profit or volunteer groups whose purposes include the identification and protection of cultural heritage resources may play an important role in interpreting and celebrating the cultural heritage value of wetlands.

The Ontario government administers several grant and incentive programs to encourage conservation and stewardship of wetlands and other important habitats. Examples of these programs are found in Appendix 1.

Complementary initiatives

Wetland conservation is an efficient, cost effective solution to several challenges facing Ontario, including a number of provincial priorities. Key provincial priorities that can be addressed through a commitment to wetland conservation include protecting the province’s biodiversity, protecting water quality and water supplies and the Great Lakes, mitigating the impacts of flooding and erosion, addressing growing infrastructure needs, mitigating climate change and helping communities address and build resiliency to climate change. Likewise, a number of initiatives designed to improve natural heritage and biodiversity conservation simultaneously support the goals of A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario. These initiatives include:

- Biodiversity:

- Ontario’s Biodiversity Strategy is the guiding framework for coordinating the conservation of the province’s rich variety of life and ecosystems. Biodiversity: It’s in Our Nature (the government implementation plan for the strategy) provides a broad framework to improve conservation in Ontario through actions that engage people, reduce threats to biodiversity, enhance ecosystem resilience and improve knowledge. Many of the actions and activities outlined in these plans will have both direct and indirect benefits to wetlands.

- Climate change:

- Ontario has made a strong commitment to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Ontario’s Climate Change Strategy, 2015 sets out the transformative change required to reduce greenhouse gas emissions below 1990 levels by 37 per cent by 2030 and by 80 per cent by 2050. The Climate Change Action Plan, 2016–2020 lays out the range of actions Ontario is taking over the next five years to meet its 2020 targets and establishes the framework necessary to achieve the transformative goals of the Strategy. The province is also updating climate change adaptation planning that will build on Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan, 2011-2014 which includes several actions to maintain and restore ecosystem resiliency and wetlands, as well as the proposed Naturally Resilient: MNRF's Natural Resource Climate Adaptation Strategy. One of the priority actions which relates to wetlands is the commitment to invest in traditional and natural infrastructure.

- Invasive Species:

- Ontario’s Invasive Species Strategic Plan (OISSP) aims to reduce the impact of invasive species, prevent new invaders from arriving and surviving and to halt the spread of existing invasive species. The Invasive Species Act, 2015 establishes an enabling regulatory framework that will allow Ontario to better prevent, detect, control and eradicate invasive species across the province. Invasive species represent one of the key threats to wetland ecosystems, and together, the OISSP and the Act will help to prevent, detect, respond to and manage their impacts.

- Pollinator Health Action Plan:

- Ontario’s Pollinator Health Action Plan is designed to improve the health of Ontario’s pollinator populations, to contribute to a sustainable food supply and to support resilient ecosystems and a strong economy. Pollinators play an important role in the maintenance of healthy ecosystems, including wetlands. There are several actions in the Plan aimed at restoring, enhancing and protecting pollinator habitat, which will also benefit wetland conservation in the province.

- Green infrastructure:

- Green infrastructure means natural and human-made elements that provide ecological and hydrological functions and processes (e.g. natural heritage features and systems, vegetation and landscaping, street trees and other urban forest elements, green roofs, etc.). The province of Ontario encourages the use of green infrastructure solutions as a means to better manage stormwater, decrease energy use and increase carbon storage in vegetation. Green infrastructure also plays a role in improving air and water quality, preserving biodiversity and the health of pollinators and reducing flood impacts. The conservation of wetlands — including the creation of wetlands — is an alternative to traditional infrastructure that will help to build resilience to the effects of climate change and improve wetland functions and ecosystem services on the landscape.

Ontario’s Wetland Conservation Strategy

The Ontario government has long understood the importance of wetlands and continues to provide strong leadership to conserve these vital ecosystems. From enacting progressive legislation and policy designed to protect and enhance wetlands, to working with partners in the delivery of innovative programs to encourage stewardship and landscape restoration, the Ontario government is committed to conserving wetlands.

A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario represents a framework to improve the conservation of wetlands across the province. The Strategy provides a vision, goals and outcomes for conserving Ontario’s wetlands as well as a list of actions the Ontario government will undertake to ensure progress. The Strategy operates as an integrated part of the existing legislative, policy and strategic framework for natural resource and biodiversity conservation in the province and seeks opportunities for improvement. It also supports provincial, regional, continental and international objectives for wetland conservation that have been established through a variety of mechanisms (e.g. North American Waterfowl Management Plan, Ontario Eastern Habitat Joint Venture, Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy, etc.). The intent is to provide both the Ontario government and the people of Ontario with a common focus and a path forward, so that we can all achieve greater success in wetland conservation in a more efficient and effective manner.

Wetland conservation, akin to the management of other natural resources, requires an integrated approach. As such, A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario has been shaped through engagement with a variety of industry, academic and non-governmental organizations, stakeholders, First Nation and Métis Peoples and communities, individual Ontarians and federal, provincial and municipal government staff. Of critical importance is the need for all people to support this Strategy as a mechanism to achieve more integrated and collaborative approaches to the protection of wetlands in Ontario.

The successful implementation of A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario will also require the support, involvement, knowledge, innovations and practices of First Nation and Métis Peoples and communities. The Strategy is consistent with the constitutional protection provided for existing Aboriginal and treaty rights and supports the involvement of lndigenous Peoples in wetland conservation in Ontario.

While there are already many important policies and programs in place to protect Ontario’s wetlands, without future action these areas will face increasingly serious threats. The Ontario government and its partners must continue to reach higher and further to ensure that wetlands remain an enduring part of Ontario’s landscape. This Strategy provides that roadmap.

Vision

Ontario’s wetlands and their functions are valued, conserved and restored to sustain biodiversity and to provide ecosystem services for present and future generations.

Our guiding principles

This Strategy is underpinned by seven core principles that establish important concepts, values and approaches that form the basis of effective wetland conservation. These principles are as follows:

- Wetlands are integral components of their watersheds, natural heritage and hydrologic systems, and part of the larger landscape. Wetlands are also important to the global climate system.

- Wetlands and their functions provide important benefits that are vital to the health and well-being of all life in Ontario and improve the province’s resilience to climate change.

- Wetlands should be conserved based on three hierarchical priorities:

- Protection – retain extent and functions of existing wetlands

- Mitigation – minimize further damage to wetlands, and

- Restoration – improve and re-establish wetland extent and function on the landscape.

- Wetlands should be conserved based on a precautionary approach and using the best available science, information and traditional ecological knowledge.

- Conservation of all wetlands and their functions is important, including provincially significant, coastal wetlands and other locally and regionally important wetlands.

- Wetlands should be conserved in a manner that recognizes and is informed by the Aboriginal and treaty rights, as well as the interests of First Nation and Métis communities.

- Wetlands should be conserved in strong partnership with other levels of government, First Nation and Métis communities, local public sector agencies, private landowners, the agricultural community, industry, non-government organizations and others involved in wetland conservation.

Goals and outcomes

A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario is based on four strategic directions that reflect the critical components required to conserve Ontario’s wetlands. These include awareness, knowledge, partnership and conservation. Each of the strategic directions is supported by a long-term goal and desired outcome to focus efforts, provide aspirations for achievement and establish a flexible framework through which to plan and implement actions to benefit the conservation of wetlands and their functions. The four strategic directions, goals and outcomes are outlined in table 2.

Table 2: Strategic directions with associated goals and desired outcomes

| Strategic Direction | Goal | Desired Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Develop and advance public awareness of, appreciation for and connection to Ontario’s wetlands. | People are inspired and empowered to value and conserve Ontario’s wetlands. |

| Knowledge | Increase knowledge about Ontario’s wetlands, including their status, distribution, functions and vulnerability. | Better knowledge is available and used to make decisions to improve wetland conservation. |

| Partnership | Establish and strengthen partnerships to focus and maximize conservation efforts for Ontario’s wetlands. | People, communities and organizations collaborate and work together to improve wetland conservation. |

| Conservation | Develop conservation approaches and improve policy tools to conserve the area and function of Ontario’s wetlands. | Ontario has a strong and effective foundation to conserve and stop the net loss of wetlands. |

Actions

A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario includes a comprehensive suite of actions that the Ontario government is taking or will take, to conserve Ontario’s wetlands. Each action is related to one or more of the goals and desired outcomes and contributes to achieving the Strategy’s overarching vision and targets. Many actions also support or align with other government priorities, such as biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and Great Lakes water quality. Although the Province has committed to implementing the Strategy, many actions will involve collaboration with municipalities, First Nation and Métis communities, conservation authorities, the agricultural community, industry, environmental organizations, and others. Public engagement and the consideration of existing policy and land use planning frameworks in the province will also be important considerations.

It is important to note that as our knowledge and understanding of wetlands and their conservation improves, new issues will emerge and further actions may be considered. Some actions may also be completed more quickly, while others may take longer. As such, the identified actions do not represent an exhaustive list or preclude the identification of new Ontario government initiatives to support wetland conservation in the future.

Targets

By 2025, the new loss of wetland area and function is halted where wetland loss has been the greatest.

By 2030, a net gain in wetland area and function is achieved where wetland loss has been the greatest.

Strategic direction – Awareness

At the most fundamental level, the greatest challenge to wetland conservation in Ontario is the limited value that society, as a whole, places on the functions that wetlands perform and the services and benefits they provide. This is largely due to limited awareness and understanding about the critical roles wetlands play in our province. Additionally, the fact that many wetland functions are 'public goods' whose benefits accrue to the wider community rather than individual landowners also poses a challenge.

The Ontario government recognizes the need for better education, communication and awareness about the importance of wetlands and the essential role they play in maintaining a healthy environment and supporting our quality of life. There is also a need to encourage and support private stewardship of wetlands, so they can continue to supply benefits to the wider community.

Actions under this strategic direction include those related to improving wetland education, better communicating the value of wetlands to the public and encouraging active participation in wetland conservation through volunteerism and stewardship.

Goal: Develop and advance public awareness of, appreciation for and connection to Ontario’s wetlands.

Outcome: People are inspired and empowered to value and conserve Ontario’s wetlands.

Actions:

- Evaluate existing communication materials and outreach initiatives about wetlands to assess gaps.

- Improve understanding of the motivations, values, attitudes and practices of landowners who conserve or do not conserve wetlands, as a guide for promoting stewardship.

- Develop and employ innovative strategies to effectively communicate the value of wetlands and their connections to the landscape and natural systems to the public.

- Develop, implement and promote initiatives that communicate the socio-economic value of wetlands and the ecosystem services they provide.

- Promote existing education programs (e.g. Project Wild, Envirothon, Adopt-a-Pond) and develop new programs to teach the importance of wetlands to youth.

- Continue to support international partnerships that raise awareness of the importance of Ontario’s wetlands in the broader landscape (e.g. Ramsar Convention, North American Waterfowl Management Plan, Eastern Habitat Joint Venture, etc.).

- Work with First Nation and Métis communities and organizations to develop targeted initiatives and materials and to include First Nation and Métis perspectives in wetland awareness initiatives.

- Improve information management and public access to open data, including wetlands inventory and mapping data and results of research on functions, threats, status and trends.

- Continue to support, encourage and promote stewardship of wetlands on private lands (e.g. Canada-Ontario Environmental Farm Plan, Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program, and Species at Risk Stewardship Fund).

- Explore the development of stewardship programs that support First Nation and Métis community studies, restoration and monitoring.

- Analyze and describe practical opportunities for public and private sectors to undertake wetland conservation projects, including development and communication of best management practices.

- Explore the development of multi-ecosystem (e.g. wetland, woodland, grassland) stewardship plans.

Strategic direction – Knowledge

Decades of scientific inquiry have expanded our knowledge of wetlands, their important role on the landscape, and the ecosystem services they provide, but there is still much to learn. For example, there is a need to better understand the relationship between wetlands and uplands and their implications for habitat connectivity, as well as the relationship between wetlands and ground and surface waters, which are important for source water protection. Further, there is a need to better understand what mitigation and restoration techniques are most effective, how traditional knowledge can help us better understand wetlands, and the role wetlands play in ecosystem services related to climate change, such as carbon sequestration and flood attenuation.

Successful wetland management depends on ongoing monitoring and assessment to ensure that conservation activities are tailored to the dynamic nature of the landscape. Implementing robust monitoring and assessment of the condition and functions of Ontario’s wetlands is crucial to ensuring that Ontario’s efforts are making a difference. Actions under this strategic direction include support for ongoing research as well as improvements to monitoring and assessment of the area and quality of Ontario’s wetlands.

Goal: Increase knowledge about Ontario’s wetlands including their status, distribution, functions, and vulnerability.

Outcome: Better knowledge is available and used to make decisions to improve wetland conservation.

Actions:

- Develop criteria and a framework to prioritize areas for improving wetland inventory and knowledge.

- Assess and improve the capability of existing tools and resources for mapping, describing and documenting change in the area, functions and condition of wetlands over time at various scales.

- Update and refine provincial wetland mapping to align with evaluation of policy and planning actions and targets.

- Establish a framework for determining priority areas and focusing efforts for conservation and restoration that considers the broader landscape context and provincial commitments (e.g. wetland loss, habitat connectivity, natural heritage systems, mitigation and adaptation to climate change).

- Support mapping and assessment of ecologically significant groundwater recharge areas and discharge to wetlands to provide information on water balances and sustainability.

- Continue to investigate current and emerging threats to wetlands and develop effective strategies to mitigate impacts on wetland functions.

- Support research into the development of effective prevention, detection, monitoring and control (mechanical, biological and chemical control) of invasive species in wetlands.

- Support research into understanding and quantifying how wetlands are responding to climate change (e.g. changes to their hydrologic functions, changes in their role to act as carbon sinks or sources and in their role to support aquatic and terrestrial habitats).

- Support research into the role of wetlands in adaptation strategies and climate resiliency (e.g. ecosystem services such as flood attenuation).

- Expand programs that assess risk and vulnerability of wetland species and ecosystems to climate change (e.g. Far North permafrost, peatland drying, changes in fire regime, etc.) to inform mitigation and adaptation efforts.

- Explore the feasibility of carbon offsetting protocol for wetlands.

- Support research into developing methods and approaches for cumulative effects assessment on wetlands.

- Support research into the role that wetlands (existing, restored and constructed) can play in improving water quality (including phosphorus reduction capabilities) and managing water quantity for supply and natural hazard management.

- Enhance understanding of the reciprocal relationship between wetlands, ground and surface water features, and hydrologic functions (e.g. quantifying the role of groundwater in maintaining wetland function).

- Support First Nation and Métis communities in collecting, storing and managing local and traditional ecological knowledge related to wetlands.

- Identify and better understand the functions and ecosystem services provided by wetlands as well as their economic value.

- Improve and develop new tools to assess and monitor wetland function within watersheds.

- Develop site-specific tools for assessing wetland function, condition and restoration success.

- Support research into the efficacy of terrestrial and riparian buffers in maintaining wetland conditions and functions.

- Enhance expertise and guidance for restoring wetlands (constructed wetlands and green infrastructure) and thereby the success in restoring wetland functions and benefits.

- Increase capacity, support research and provide advice on the design of monitoring programs to track changes in wetlands and evaluate the outcomes of conservation and mitigation activities.

- Develop and implement a broad-scale monitoring program to assess trends in the quality and function of wetlands.

Strategic direction – Partnership

Across Ontario, many public and private agencies, organizations and institutions are involved in the conservation of wetlands (e.g. governments, First Nation and Métis peoples and communities, conservation authorities, non-government organizations, local community interest groups, etc.). While the overall goals of these groups are often similar, their work is not always coordinated. The conservation of Ontario’s wetlands requires an integrated approach, and encouraging cooperation and supporting partnerships is essential to successful wetland conservation. Actions under this strategic direction include efforts to clarify roles and responsibilities, encourage improved communication, cooperation and coordination and work collaboratively with partners involved in wetland conservation.

Goal: Establish and strengthen partnerships to focus and maximize conservation efforts for Ontario’s wetlands.

Outcome: People, communities and organizations collaborate and work together to improve wetland conservation.

Actions:

- Clarify roles and responsibilities of various agencies involved in wetland conservation to ensure wetland protection.

- Improve inter-agency cooperation and coordination to ensure that wetland programs and policies do not have conflicting objectives.

- Work collaboratively with partners to enhance coordination, leadership, outreach and learning about the importance of wetlands and wetland conservation actions.

- Enhance coordination within government to prioritize wetland conservation projects supported through funding initiatives.

- Support the efforts of land securement agencies in all sectors to protect and enhance wetlands.

- Continue to participate in partnerships such as the Ontario Eastern Habitat Joint Venture and other initiatives that work to promote and conserve Ontario’s wetlands and that are important in a broader landscape context.

- Further develop conservation partnerships between the Ontario government, municipalities, First Nation and Métis communities, conservation authorities, the agricultural community, private landowners, environmental organizations and industry to share information, promote the value of wetlands, encourage conservation, implement best management practices, monitor change in wetland area and function and identify restoration opportunities.

- Continue to work with partners to address threats to wetlands (e.g. detection, monitoring, removal and control of invasive species, pollution control, etc.).

- Continue to work with partners to restore wetlands and their functions to support healthy, resilient ecosystems and communities.

- Build partnerships with the academic community to research effective techniques for wetland restoration and creation, and monitoring.

- Work with partners (e.g. academia, federal government) to monitor and assess carbon emissions and sequestration in wetlands (e.g. through current provincial efforts to develop an Ontario land use carbon inventory), as well as climate change adaptation functions of wetlands.

- Work with local governments, local public sector agencies, stakeholders, First Nation and Métis communities and interest groups to develop and implement regional and landscape level wetland conservation strategies to guide wetland conservation.

Strategic direction – Conservation

Ontario has a broad range of policies and legislation to support wetland conservation. The integration and implementation of these tools remains a priority; however, improvements to Ontario’s current wetland conservation policies and implementation are also required. Improvements will result from reviewing the effectiveness of the provincial laws, regulations and policies to ensure the conservation of wetlands, identifying gaps and proposing improvements as soon as possible. Exploring the development and implementation of new policies to better conserve Ontario’s wetlands will also be important. Actions under this strategic direction include seeking opportunities to improve wetland conservation and enhancing guidance for wetland conservation.

Goal: Develop conservation approaches and improve policy tools to conserve the area and function of Ontario’s wetlands.

Outcome: Ontario has a strong and effective foundation to conserve and stop the net loss of wetlands.

Actions:

- Review provincial laws, regulations and policies, with the goal of strengthening Ontario’s wetland policies.

- Integrate a clear and consistent definition of wetlands across policy.

- Support the development of policy tools to improve the conservation of all wetlands, including provincially significant, coastal wetlands and other locally and regionally important wetlands.

- Develop conservation approaches and policy tools to prevent the net loss of wetlands in Ontario, focusing on areas where wetland loss has been the greatest.

- Review and improve the method by which provincially significant wetlands are identified and continue wetland evaluations across the province.

- Promote and expand opportunities to enhance wetland conservation and restoration through the Drainage Act.

- Strengthen provincial level guidance for integrating wetland values in Environmental Impact Statements.

- Enhance policy and guidance for wetland conservation on Crown land, including resource management, land administration, environmental assessment and the role that can be played by land use planning.

- Develop and ensure that adequate policy guidance is available on incorporating wetland protection strategies in local planning (e.g. natural heritage system planning, consideration of wetlands in the development of land use policies addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation and planning for natural hazard management).

- Ensure that wetland conservation strategies and tools integrate climate change adaptation and mitigation considerations.

- Develop and implement policies and strategies to support climate change mitigation by sequestering and storing carbon in wetlands, consistent with actions in Ontario’s Climate Change Action Plan.

- Continue and enhance protection of wetlands through the provincial Protected Areas System and other effective area-based conservation measures.

- Continue to support and strengthen Great Lakes policies, initiatives and other efforts for wetland conservation aligning with commitments made in domestic and binational agreements (e.g. Great Lakes Protection Act, Canada-Ontario Agreement on Great Lakes Water Quality and Ecosystem Health) and strategies (e.g. Ontario’s Great Lakes Strategy).

- Develop best management practices for activities in proximity to wetlands (e.g. establish limits for surface and groundwater withdrawals, draining or infilling in or near vulnerable wetlands, in order to enhance the resiliency of these wetlands to change) and for wetland creation as part of green infrastructure or alternatives to traditional infrastructure to help build resilience and improve other ecosystem services.

- Support the identification of additional candidate wetlands for international recognition under the Ramsar Convention and/or other national/international programs (e.g. UNESCO Biospheres, Important Bird Areas, Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network, etc.).

- Integrate wetland restoration and planning efforts with other watershed planning efforts.

- Work with First Nation and Métis Peoples and communities to include local and traditional ecological knowledge in wetland conservation strategies and best management practices.

- Explore improvements to policies and approaches to encourage wetland conservation on private land (e.g. tax incentive programs).

- Integrate the economic value and the value of the ecosystem services provided by wetlands into decision-making (e.g. promoting green infrastructure alternatives to traditional infrastructure).

- Develop performance measures and publicly report on progress toward targets and implementing actions.

- Develop an implementation plan to prioritize actions and facilitate a coordinated approach to meeting targets.

Monitoring success

To monitor the success of this Strategy, two overarching targets have been established:

- By 2025, the net loss of wetland area and function is halted where wetland loss has been the greatest.

- By 2030, a net gain in wetland area and function is achieved where wetland loss has been the greatest.

The areas where the targets are intended to apply generally include Southern Ontario where wetland loss has been the greatest, as well as other areas where considerable wetland loss may occur in the future. These areas may be refined as wetland inventory and knowledge is improved.

Baseline data for these targets has been established from the 2010 Southern Ontario Land Resource Information System (SOLRIS) data. The process of determining the area of wetlands in the province involves the analysis of time-series satellite imagery. It takes 5 years to acquire cloud-free imagery for the benchmark year, compile provincial data, and analyze and validate all wetland change events. By 2025 it will be possible to report on the area of wetlands south and east of the Canadian Shield in 2020. Likewise, in 2030, Ontario will be reporting on the area of wetlands in 2025.

Given these broad benchmarks, monitoring and assessment must provide information on the total area, function and condition of wetlands in the province. Tracking this information over time will provide evidence to determine whether or not the Strategy is having the desired effect and indicate if changes are required to the actions, the way they are implemented, or both.

To measure and report on these targets will initially be challenging, particularly in areas where Ontario’s wetland inventory is incomplete or in need of updating. Also, to date there has not been a rigorous, systematic and standardized approach taken to assessing wetland condition or functions. Despite these obstacles, there are several actions outlined in the Strategy that will allow for advancement in these areas in the near future. Together, these actions will lay the groundwork for measuring the success of the Strategy.

As part of monitoring the success of this Strategy, the Ontario government also commits to developing a performance measurement framework and reporting to the public on progress in implementing the actions in this Strategy as well as progress towards achieving the targets. Progress reports will be published every five years, beginning in 2020.

Where we go from here

Ontario’s commitment to wetland conservation is embedded in the actions described in this Strategy. These have been developed over time, in response to the growing pressures facing wetlands, and through an extensive engagement process. Some actions will be simple and straightforward to complete, while others will involve sequential steps, engage a number of partners and take time. Many actions support or align with other government priorities, such as biodiversity conservation and climate change mitigation. Further, as many wetlands are located on provincial Crown lands, the Ontario government has an opportunity to play a leadership role in the conservation of wetlands.

Resulting from shared legislative responsibility, several ministries have a responsibility for, or interest in, wetland management (e.g. Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change, Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Ministry of Northern Development and Mines, Ministry of Transportation). An implementation plan will be developed to prioritize actions, and coordinate an approach to meeting targets.

The areas where the targets are intended to apply generally include Southern Ontario (south of and east of the Shield) where historical loss has been the greatest. However, action will not be limited to areas where targets apply.

Implementation planning will include prioritizing where to improve wetland knowledge and mapping, and what types of action will take place in different parts of the province. Maintaining connectivity and functions will be the focus of work in some parts of the province, but restoration of wetlands and re-establishment of functions will be required where there are few wetlands remaining. Reporting on a 5 year cycle will allow us to adapt implementation planning on a regular basis and refine prioritization through improved wetland inventory mapping of area and function.

Many actions will also involve collaboration with municipalities, First Nation and Métis communities, conservation authorities, the agricultural community, industry, environmental organizations, and others. Continued public engagement, First Nation and Métis involvement, and the consideration of existing policy and land use planning frameworks in the province will also be important.

Following consultation and engagement with a variety of industry, academics, non-governmental organizations, stakeholders, First Nation and Métis Peoples and communities, and individual Ontarians, three actions in this Strategy have been prioritized above all others. Work to advance these actions will begin with the release of the Strategy. These actions represent clear needs for wetland conservation and will help Ontario achieve the goals outlined in the Strategy.

Action 1: Improving Ontario’s wetland inventory and mapping

Ontario’s changing landscape and associated land use practices require updated information about the area, location and quality of existing wetland habitats. This information, coupled with wetland trend analysis and assessments, can help focus government actions and programs. Using updated wetland mapping information can assist in the development and implementation of land use policies and protocols and measure performance of those policies and protocols towards conservation objectives.

The Ontario government currently maintains a wetland inventory for the province that includes best available information about the location, area and significance of wetlands. This includes high-quality information collected through detailed field work as well as mapping based on air photo interpretation and satellite imagery. While this inventory is a good start, more current and detailed mapping and regular updating are required to better conserve wetlands.

Ontario’s wetland inventory could be improved by implementing a series of activities that includes:

- Updating wetland mapping to align with policy and planning targets and enhancing mapping in areas in high growth zones and where wetland mapping is currently limited.

- Standardizing wetland mapping techniques to improve consistency.

- Implementing the latest technologies for improved mapping and remote sensing.

- Continuing to monitor wetland change and improving methods to detect and measure change over time.

- Incorporating climate change considerations.

- Evaluating how to include information collected by citizen scientists to enhance inventory and monitoring programs.

Specific wetland inventory activities include:

- In 2018, prioritize areas under most pressure for refinement of mapping using remote mapping standards and/or wetland evaluations.

- In 2018, collaborate with partners and First Nation and Métis communities in the ongoing maintenance and improvement of wetland mapping and information.

- By 2020, conduct wetland evaluations and remote-mapping in identified priority areas.

- By 2020, complete mapping of all coastal wetlands.

- By 2020, complete updates of the Southern Ontario Land Resource Information System (SOLRIS) to allow reporting in changes on wetland area.

- By 2020, undertake development of a broad-scale monitoring framework for the assessment of trends in the quality and function of wetlands.

Improving Ontario’s wetland inventory is a priority action in A Wetland Conservation Strategy for Ontario and will improve the availability and accessibility of wetlands data to lay the foundation for improved wetland conservation across the province.

Action 2: Creating no net loss policy for Ontario’s wetlands

As Ontario’s population grows and demands for resources increase, natural areas such as wetlands will continue to be threatened where human growth interests intersect with conservation interests. One option to prevent the net loss of wetlands in Ontario is the development of a wetland offsetting policy. As noted below, this will not reduce protection for those wetlands already protected by existing law and policy.