The content on this page is no longer up to date. It will remain on ontario.ca for a limited time before it moves to the Archives of Ontario.

Chapter 3: Changing pressures and trends

Under our Terms of Reference, the objective of this Review is to improve security and opportunity for those made vulnerable by the structural economic pressures and changes being experienced by Ontarians in 2015.

This requires that we reflect on the pressures and changes that have been and are occurring. Most of the pressures we describe are the subject of extensive literature and analysis by experts. We can do no more here than describe them in the briefest of terms.

Our understanding of the economic pressures, how the workplace has changed in ways relevant to this Review and who are vulnerable workers in need of greater protection, is based on our own reading and on a number of academic papers prepared for us, and especially two background reports prepared for the Review: Morley Gunderson, Changing Pressures Affecting the Workplace, 2015; and, Implications for Employment Standards and Labour Relations Legislation, 2015, from which we have borrowed significantly. However, the views expressed here are our own.

Introduction

This Chapter discusses the inter-related factors that have contributed to the changing workplace.

The starting point is to recognize that the basic structural and conceptual framework for the two Acts (LRA and ESA) we are reviewing was set decades ago. While these Acts have been significantly amended over the years, the basic conceptual frameworks and approach for each of them has remained. Accordingly, we must evaluate how well they are operating to meet the needs of vulnerable workers today, and potentially develop new approaches that may be required in light of workplaces that have changed over a long period and continue to change.

If this Review must re-evaluate the laws and regulations that were designed for an earlier time, it must be recognized that the existing framework of both Acts was designed largely for an economy dominated by large fixed-location worksites, where the work was male-dominated and blue-collar, especially in manufacturing. In that sector, large employers were often protected by tariffs and limited competition, and union coverage was far higher. Today the economic landscape is vastly different for both employers and employees; over many years the manufacturing sector in Ontario has shrunk significantly, while the service sector has grown significantly.

Pressures affecting employers and the demand for labour

Globalization

Markets for products and services are increasingly globalized and are often outsourced to foreign firms. Tariff reductions, free-trade agreements and reductions in transportation and communication costs have encouraged this trend. Companies in some sectors, notably manufacturing, previously protected by tariffs, are now subject to intense international competition, especially from imports from low-wage developing countries.

A related pressure is the trend to offshore outsourcing of business services, which is now made possible by the internet, computer technology, and software for global networking. Businesses can send their requests at the end of their business day to another time zone and have the responses the next day. Within business services, the trend has been to outsourcing increasingly sophisticated services.

In addition to global competitive pressures, Canada has experienced a re-orientation from east-west trade within Canada towards north-south trade between Canada and the United States as well as Mexico, largely as a result of free trade agreements. At the present time, the renegotiation of NAFTA is imminent as a result of the change in administrations in the United States. There is also a possibility of border taxes on goods imported into the United States. These pressures have given rise to significant uncertainty. A new trade agreement with Europe may be put in place and even with the apparent demise of the Trans Pacific Partnership, other agreements in Asia are being explored and are likely, if they come to fruition, to further diminish the importance of internal east-west trade. The reorientation to external trade (much of it north-south) makes it likely that Canadian business will increasingly compete with United States’ businesses, which tend to have fewer labour regulations and restrictions.

With the increasing mobility of capital, some firms may have a credible threat to relocate their plants and investments into jurisdictions that have lower regulatory costs. One significant concern is that such competition for investment will lead to a race to the bottom

or harmonization to the lowest common denominator

in employment and labour relations law, and that this would discourage any efforts to improve conditions for Ontario workers.

The fear of workers, their communities, and policy makers of losing new investments or having plants relocate out of the province is real. The evidence of what actually influences business on this issue, however, tends to be inconclusive and controversial as shown in the research commissioned for this Review America First

policies, and the renegotiation of NAFTA have the potential to cast a strong political dimension onto investment decisions.

Many businesses in Ontario are not affected by these considerations because they are in non-tradable services. Moreover, many employers will not follow a strategy of relocation or investing in the lowest-wage or least-regulated jurisdiction because there are a host of factors that inform these decisions and make Ontario attractive, positive factors such as its educated, skilled and reliable workforce, its corporate tax structure, the exchange rate for the Canadian dollar, the public funding of its health care system, and many others. However, Ontario must consider the effect of its polices on business costs and competitiveness, especially in light of increased competitive global pressures, the north-south re-orientation and the increased mobility of capital. There is a need for smart regulation

that can foster not only equity and fairness, but also conditions that support business.

Technological change

Skill-based technological change and the transformation to the knowledge economy have had profound effects on the kind of workforce that is needed today and have facilitated many other trends, including global networking and trade and offshore outsourcing (including the outsourcing of business services). These changes associated with the computer and the internet are facilitating changes in manufacturing and distribution such as just-in-time-delivery systems, robotics, 3-D manufacturing, movie streaming, and bar-code scanning systems.

The new so called sharing economy

or the GIG economy

manifested by such companies as Uber or Airbnb are becoming increasingly important. They have the capacity to transform some industries and workplaces, as many purport to use independent contractors, and not employees, as the providers of services, making the issue of who is an employee even more important than previously.

The growth of online platforms for the performance of freelance projects, and also for crowd based clickworkers

, have the potential to speed up dramatically the transformation of work and the workplace.foresight

organization within the Government of Canada, the increasing presence of virtual workers in online platforms is a potentially disruptive feature of the digital economy creating a global marketplace for labour and potentially driving down compensation.

One of the more disruptive features of the emerging digital economy is the rise of virtual workers. Online work platforms (e.g. freelancer.com) enable individual workers to advertise their skills and find short-term contracts with employers all over the world, creating a global digital marketplace for labour. An estimated 48 million workers were registered on online work platforms globally in 2013.

The growth of artificial intelligence, the breaking down or unbundling of jobs into constituent tasks, and increased automation and robotization, is expected by many to impact directly on the types and number of jobs, although the pace, extent and consequences are unknown. This can be expected to become a major focus of social policy, as Ontario and Canada seek ways to adjust to these developments.

Changing from manufacturing to services

One of the major consequences of these competitive global pressures, along with the industrial restructuring that has taken place in Ontario, is the shift from manufacturing to services. From 1976 to 2015, for example, manufacturing’s share of total employment fell from 23.2% to 10.8%, a decrease of 12.4 percentage points. Over that same period, the service sector’s share increased from 64.5% to 79.8%, an increase of 15.3 percentage points. The increase in the service sector, however, was polarized, with the largest increases occurring in higher paying professional, scientific, technical and business services combined (from 4.6% to 13.2%) and lower paying accommodation and food services (from 3.9% to 6.4%).

This shift in the labour market has resulted in a hollowing out

or disappearing middle

of the skill and wage distribution, often involving job losses for older workers in relatively well-paid, blue-collar jobs in manufacturing. These displaced workers generally do not have the specific skills to move up to the growing number of higher-end jobs in business, financial and professional services. Their skills are often industry-specific (e.g., steel, auto manufacturing, pulp-and-paper) and not transferable to other industries. Many are middle-aged workers who are often regarded as too old to retrain or relocate, but too young to retire. They often wind up in low-wage, non-union jobs in personal services. The disappearing middle

of the occupational distribution also means that it is more difficult for persons at the bottom of the distribution to train and move up the occupational ladder since those middle steps

are now missing. They are often trapped at the bottom with little or no opportunity for upward occupational mobility.

According to the OECD, the decline in middle-skill employment went hand in hand with a decrease of standard work contracts, and workers taking on low and high-skill jobs were increasingly likely to be self-employed, part-timers, or temporary workers.

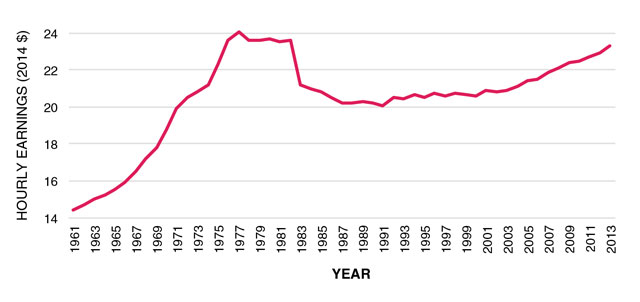

These developments are an obvious source of growing wage and income inequality as well as the stagnation of the growth of real wages as Graph 1 demonstrates.

Real Wage Growth (Average hourly earnings, adjusted)

Changes in business strategy and organization:

fissured workplaces

In an effort to explain how, in the last 20-or-so years, workplaces have fundamentally (in his view) worsened, David Weil described the fissuring

process where lead companies in many industries reduced their own large workforces in favour of a complicated network of smaller employers

In his book, Weil describes how lead companies, through contracting and outsourcing, reduce costs and place themselves in a position where they are not responsible for the indirect employment they create as they shift liability and cost to others. He describes how this shift to smaller companies that provide lead companies with products and services is a deliberate strategy to create intense competition at the level of employers below the lead company, and causes significant downward pressure on compensation while shifting responsibility for working conditions to third parties. Weil shows how this has created increasingly precarious jobs for employees who perform work for contractors and often for many levels of subcontractors.

Fissuring has occurred, in Weil’s view, as a result of operationalizing several distinct business strategies, one focused on revenue, another on costs and a third, which he describes as the glue

which binds these strategies together. On the revenue side, a lead company will focus on building its brand and creating important new and innovative goods and services, while also coordinating the supply chains that make these possible. On the cost side, lead companies contract out or outsource activities that used to be done internally, creating intense competition among potential suppliers and contractors to provide the lead company with products or services.

The critical factor, which allows the revenue and costs strategies to be integrated and which makes the overall business strategy successful is that the lead company can control the product and services provided by the contractors and subcontractors through new information and communication technology. That technology makes possible the creation of detailed complex standards to which contractors must abide, and also makes it possible for the lead companies to control and enforce all the standards on product quality, delivery, and other services that the contractors and subcontractors provide. Thus, contractors of the lead company, often in fierce competition with other similar companies, must comply with the rigorous supervision of the lead company. Under this strategy, the lead company avoids the legal responsibility that goes with directly employing the employees of the contractors and subcontractors, and any statutory or bargaining responsibility that goes with it. The smaller employers are therefore less stable themselves and often have more uncertain relationships with their own workers.

Franchising in some industries is another example of a business strategy where the lead company, as franchisor, avoids liability for the employees involved in the execution of the strategy and direct selling of the product, which is the core of its brand. The franchisor at the top of the supply chain may or may not be removed from the everyday operation of the business where issues of compliance with employment standards arise. However, most franchisors write and enforce detailed contracts, including legally binding manuals for franchisees that are constantly changing and relate to virtually every aspect of the business. Regulating the contractors and small companies that compete in various industries for the work of the lead companies can be difficult. The business model set up by the franchisor may squeeze profit margins, putting pressure on franchisees not to comply with minimum standards. Moreover, unlike larger companies, these smaller businesses generally do not have a sophisticated human resources department that will ensure compliance with the law.

Clearly, the resources of government to monitor compliance are stretched in any event, and stretched even further by the number of small employers, especially if a meaningful number of small employers do not comply with employment standards. The low risk of complaints from employees, particularly from those with little or no bargaining power, combined with the low risk of inspection and low penalties by the government, makes noncompliance for some small employers simply a part of a business strategy.

In any event, fissuring is a worldwide phenomenon, and jurisdictions everywhere are struggling to find mechanisms by which the law can respond effectively and appropriately. Our jurisdiction is no exception.

Changing workplaces as a result of a changing workforce

Changing pressures have also arisen from changing demographics and the changing nature of the workforce. The workforce in Ontario has become much more diverse with more women, visible minorities, new immigrants, Aboriginal persons and people with disabilities. Many workers in these groups are likely to be vulnerable and to live in persistent poverty.

Although it has levelled off in recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in the labour force participation of women (and particularly married women, including those with children). The participation of women in the workforce is now close to that of men. The two-earner family is now the norm and not the exception. There are also many single parents with child-care responsibilities. This has led to very important issues of work-life balance, and has important implications with respect to many workplace issues, including gender inequality in compensation, compensation for part-time work as compared to full-time work, irregular work scheduling, and the right to refuse overtime.

In addition, the workforce in Canada is both ageing and living longer and the trend towards earlier retirement reversed in the later 1990s, especially for males. As larger portions of the workforce will be older, there will be higher age-related costs such as pensions and health-related benefits as well as difficulties in retraining older workers for new jobs if the old jobs become obsolete. Many older workers who retire will later return to the labour force to non-standard jobs. Some will choose do so because they want the flexibility, especially if they already have a pension, but many will do so out of necessity because that is all that is available.

Immigration is especially important to Ontario where the majority of immigrants to Canada settle. Unfortunately, there is difficulty in integrating immigrants into the Canadian labour market in the sense that immigrants are unlikely to catch-up to the earnings of domestic-born workers who otherwise are similarly-situated. The problem is getting more difficult for the more recent cohorts of immigrants who may never expect to fully catch up to the earnings of their comparable Canadian born workers. This has contributed to the increasing poverty rate amongst newly-arrived immigrants.

New immigrants are particularly likely to be vulnerable in the workplace because language barriers may keep them from knowing and exercising their rights. New immigrants may be less likely to complain about employment standards violations because they are economically vulnerable and fear reprisals. They are also less likely to work in unionized industries where the working conditions tend to be better and to be policed.

There continues to be a problem in Canada of students transitioning from school to work. Many students drop out and this often has very negative implications for their employability and earnings. This has been especially true for Aboriginal youth. The problem of youth finding it difficult to successfully transition from school to work is compounded by the fact that the initial negative experience of not being able to get a job when first leaving school can lead to a longer-run legacy of permanent negative scarring

effects which can lead to lower lifetime earnings. Young people may react negatively to a society and labour market that will not accommodate them, and employers react negatively to the prospect of hiring young people who have a large gap in employment between their leaving school and their first job.

The decline of unions in the private sector

Union coverage rates have declined in Ontario from 29.9% in 1997 to 26.8% in 2015 for the public and private sectors combined.

Much of the decline in the private sector is attributed to the movement of jobs away from industries and occupations with high union density (e.g., blue-collar work in manufacturing) to ones of low union density such as white-collar work (e.g., professional, technical and administrative) and service jobs. Some of the other alleged causes of the decline were the subject of many of the submissions to us. Some saw the decline as a result of greater employer resistance to unions, some as the result of specific changes to labour legislation that were detrimental to organizing, some as due to the union movement’s failure to modernize, adapt, and communicate effectively, while many others, especially in the academic community, point to the current law and the industrial relations system itself, which is based essentially on a Wagner Act

model of bargaining and union organization by workplace. This model is criticized as largely irrelevant to the workplaces of the very large number of small employers which makes organizing, bargaining, and administering a collective agreement at the individual employer unit level not only inefficient but virtually impossible to effect.

In 2015, 87% of workplaces (defined as business establishments with employees) in Ontario had fewer than 20 employees and around 30% of all employees worked in such establishments.

The decline in the number of unionized employees, and in the role of unions in the private sector, makes the employment standards regime even more important for the future, as that is the regime that applies minimum standards today to 86% of workers in the private sector. This is even more the case if in the future there is a lack of practical possibility of union representation for many employees.

Conclusions

Clearly there is a wide array of pressures and trends that are affecting the workplace. These were articulated to us in the various hearings and submissions provided across the province and in the research commissioned for this Review.

In many cases these pressures conflict, as when employer needs for flexibility in work scheduling conflicts with employee needs for some certainty in scheduling to facilitate work-life balance. In other cases, the pressures have the potential to benefit both employers and employees, as when some elements of non-standard employment meet the needs of employers for flexibility and the needs of some workers to balance work and other personal or family commitments.

These various trends and pressures on the workplace highlight the need for reform of employment standards and labour relations legislation and especially to provide protection to vulnerable workers and those in precarious work situations. But they also highlight the complex trade-offs that are involved and the difficulties in navigating them.

Footnotes

- footnote[26] Back to paragraph Anil Verma, Labour Regulation and Jurisdictional Competitiveness, Investment, and Business Formation: A Review of the Mechanisms and Evidence (Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Labour, 2016), prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Labour to support the Changing Workplaces Review.

- footnote[27] Back to paragraph A McKinsey & Company survey found that 20-30% of the working age population in Europe and the United States engage in some form of independent work. McKinsey & Company, Independent Work: Choice, Necessity, and the Gig Economy, Working Without A Net, Rethinking Canada’s Social Policy in the New Age of Work by Sunil Johal & Jordann Thirgood, Mowat Centre Research #132, November 22, 2016.

- footnote[28] Back to paragraph Working Without A Net, Rethinking Canada’s Social Policy in the New Age of Work by Sunil Johal & Jordann Thirgood, Mowat Centre Research #132, November 22, 2016.

- footnote[29] Back to paragraph Canada and the Changing Nature of Work, Policy Horizons Canada, May 2016, p. 3.

- footnote[30] Back to paragraph Kuek, S. et al. 2015. “The global opportunity in online outsourcing.” World Bank Group, June 2015.

- footnote[31] Back to paragraph Ibid.

- footnote[32] Back to paragraph Canada and the Changing Nature of Work, op. cit., p.1

- footnote[33] Back to paragraph Ibid.

- footnote[34] Back to paragraph Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 282-0008 – Labour Force Survey Estimates, by North American Industry Classification System, Sex and Age Group (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016). These are calculations made by the Ontario Ministry of Labour based on data from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey.

- footnote[35] Back to paragraph OECD In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All, OECD Publishing, Paris. pp. 29. >

- footnote[36] Back to paragraph Working Without A Net, op. cit., p. 7.

- footnote[37] Back to paragraph Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 380-0063 - Gross domestic product, income-based (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016).

- footnote[38] Back to paragraph David Weil, The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became So Bad for So Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014).

- footnote[39] Back to paragraph Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 279-0025 – Number of Unionized Workers, Employees and Union Density, by Sex and Province (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016); Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 282-0078 – Labour Force Survey Estimates, Employees by Union Coverage, North American Industry Classification System, Sex and Age Group (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016); Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 282-0220 – Labour Force Survey Estimates, Employees by Union Status, Sex and Age Group, Canada and Provinces (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016). These are calculations made by the Ontario Ministry of Labour based on data from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey. Union density refers to the proportion of employed workers who are union members, whereas union coverage includes both employees who are union members and employees who are not members of a union but who are covered by a collective agreement or a union contract. Overall union coverage rates are about two percentage points higher than union density rates.

- footnote[40] Back to paragraph Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 282-0076 – Labour Force Survey Estimates, Employees by Establishment Size, North American Industry Classification System, Sex and Age Group (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016); Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 552-0003 – Canadian Business Counts, Location Counts with Employees, by Employment Size and North American Industry Classification System, Canada and Provinces, December 2015 Semi-Annual (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016). These are calculations made by the Ontario Ministry of Labour based on data from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey. Note that the Statistics Canada Business Counts database does not differentiate between public and private workplaces and includes both sectors.

- footnote[41] Back to paragraph Data on union coverage by establishment size was derived from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey, upon special request by Ontario Ministry of Labour.