Lakeshore Capacity Assessment Handbook: Protecting Water Quality in Inland Lakes

This document was developed to provide guidance to municipalities and other stakeholders responsible for the management of development along the shorelines of Ontario’s inland lakes within the Precambrian Shield.

Preface

This Lakeshore Capacity Assessment Handbook has been prepared by the Ministry of the Environment in partnership with the ministries of Natural Resources and Municipal Affairs and Housing. It was developed to provide guidance to municipalities and other stakeholders responsible for the management of development along the shorelines of Ontario’s inland lakes within the Precambrian Shield. While municipalities are not required to carry out lakeshore capacity assessment, this planning tool is strongly recommended by the Ontario government as an effective means of being consistent with the Planning Act, the Provincial Policy Statement (2005), the Ontario Water Resources Act and the federal Fisheries Act.

This document is based on the scientific understanding and the government policies in place at the time of publication. Questions about planning issues should be directed to the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Scientific or technical questions dealing with water quality should be directed to the Ministry of the Environment. Questions concerning fisheries should be directed to the Ministry of Natural Resources.

Acknowledgements

This handbook is the outcome of more than three decades of scientific research and policy development. Lakeshore capacity assessment in Canada began in the 1970s with research conducted by Peter Dillon and F.H. Rigler. Researchers who contributed to the subsequent refinement of lakeshore capacity assessment and the development of the Lakeshore Capacity Model include B.J. Clark, P.J. Dillon, H.E. Evans, M.N. Futter, N.J. Hutchinson, D.S. Jeffries, R.B. Mills, L. Molot, B.P. Neary, A.M. Paterson, R.A. Reid and W.A. Scheider.

The preparation of the handbook was overseen by an inter-ministerial steering committee which included:

Ministry of the Environment: Victor Castro, Peter Dillon, Les Fitz, Fred Granek, Ron Hall, Bruce Hawkins, Heather LeBlanc, Gary Martin, Wolfgang Scheider (Chair), Doug Spry, Shiv Sud (past Chair);

Ministry of Natural Resources: John Allin, John Connolly, David Evans, Gareth Goodchild, Fred Johnson;

Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing: Kevin Lee

Many other provincial staff, too numerous to name individually, contributed to the development of this handbook. Technical writing assistance for the handbook was provided by Joanna Kidd from Lura Consulting and editorial assistance was provided by Carol Crittenden from Editorial Offload.

This version of the Handbook has been revised to reflect comments received during its posting on Ontario’s Environmental Registry in 2008. Thanks also go to the municipal staff and the members of organizations who assisted in the review of the handbook and provided many comments on its scope and contents. Their participation helped greatly to improve the document. These reviewers included:

- Judi Brouse – District Municipality of Muskoka

- Peter Bullock – City of North Bay

- Cliff Craig – Rideau Valley Conservation Authority

- Randy French – French Planning Services Inc.

- Roger Hogan – Former Township of Cardiff

(amalgamated into the Municipality of Highlands East) - Gerry Hunnius – Federation of Ontario Cottagers: Associations

- Neil Hutchinson – Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd.

- Alex Manefski – Urban Development Institute

- Pat Martin – Municipality of Dysart et al

- Patrick Moyle – Association of Municipalities of Ontario

- Ron Reid – Federation of Ontario Naturalists

- Lorne Sculthorp – District Municipality of Muskoka

Executive summary

Purpose

This handbook has been prepared by the Ministry of the Environment in partnership with the Ministries of Natural Resources and Municipal Affairs and Housing to guide municipalities carrying out lakeshore capacity assessment of inland lakes on Ontario’s Precambrian Shield.

About lakeshore capacity assessment

Lakeshore capacity assessment (a generic term, but herein used to describe the Province’s recommended approach) is a planning tool that can be used to control the amount of one key pollutant — phosphorus — entering inland lakes on the Precambrian Shield by controlling shoreline development. High levels of phosphorus in lake water will promote eutrophication — excessive plant and algae growth, resulting in a loss of water clarity, depletion of dissolved oxygen and a loss of habitat for species of coldwater fish such as lake trout. While shoreline clearing, fertilizer use, erosion and overland runoff can all contribute phosphorus to an inland lake, the primary human sources of phosphorus are septic systems — from cottages, year- round residences, camps and other shoreline facilities. Lakeshore capacity assessment can be used to predict the level of development that can be sustained along the shoreline of an inland lake on the Precambrian Shield without exhibiting any adverse effects related to high phosphorus levels.

It should be emphasized that lakeshore capacity assessment addresses only some aspects of water quality — phosphorus, dissolved oxygen and lake trout habitat. Municipalities and lake planners also need to consider other pollutants (such as mercury, bacteria and petroleum products) and other sources of pollution (including industries, agriculture and boats). It must also be emphasized that water quality isn't the only important factor that should be considered in determining the development capacity of lakes. Factors such as soils, topography, hazard lands, crowding and boating limits may be as or more important than water quality. Finally, it’s important to emphasize that, to be effective, the technical process of carrying out lakeshore capacity assessment must be followed by implementation — in other words, the information obtained must be incorporated into municipal official plans and policies.

Benefits of lakeshore capacity assessment

Use of lakeshore capacity assessment by municipalities (along with proactive land-use controls) and enforcement of water-related regulations and bylaws will help to ensure that the quality of water in Ontario’s inland lakes is preserved. The protection of water quality will also protect environmental, recreational, economic and property values.

Lakeshore capacity assessment enhances the effectiveness of the land-use development process in many ways:

- It incorporates the concept of ecosystem sustainability in the planning process

- It is consistent with watershed planning

- It promotes land-use decisions that are based on sound planning principles

- It addresses many relevant aspects of the Provincial Policy Statement (2005), which came into effect on March 1, 2005. The Provincial Policy Statement is issued under section 3 of the Planning Act.

- It encourages land-use decisions that maintain or enhance water quality

- It encourages a clear, coordinated and scientifically sound approach that should reduce conflict among stakeholder groups

- It encourages a consistent approach to lakeshore capacity assessment across the province

- It is cost effective

The net effect of lakeshore capacity assessment will likely be to shift development from lakes that are already well developed to those that are less developed.

Carrying out lakeshore capacity assessment

A lake’s capacity for development is assessed with the Lakeshore Capacity Model. The model, first developed in 1975, quantifies linkages between natural sources of phosphorus to a lake, human contributions of phosphorus from shoreline development, water balance, the size and shape of a lake and the resultant phosphorus concentrations. The model uses a number of assumptions about phosphorus loading, phosphorus retention and usage figures.

The model allows the user to calculate how the quality of water in a lake will change in response to the addition or removal of shoreline development such as cottages, permanent homes and resorts. It predicts an important indicator of water quality: the total phosphorus concentration.

The model can be used to calculate undeveloped conditions of a lake, how much development can be added (in terms of the number of dwelling units) without altering water quality beyond a given endpoint, and the difference between current conditions and that endpoint.

Land use planning application and best management practices

Best management practices (BMPs) are planning, design and operational procedures that reduce the migration of phosphorus to water bodies, thereby reducing the effects of development on water quality. These BMPs apply to all lots, vacant or developed.

The maintenance of shoreline vegetation, installing vegetative buffers and minimizing the amount of exposed soil helps to reduce phosphorus loading - that is, the amount of phosphorus entering a body of water. Use of a siphon or pump to distribute septic tank effluents to the tile bed can also reduce phosphorus loading. Moreover, phosphorus loadings from septic systems can be reduced by avoiding the use of septic starters, ensuring that all sewage waste goes into the septic tank, pumping the tank out every three to five years and reducing water use.

Monitoring water quality

The predictions made by the Lakeshore Capacity Model should be validated by monitoring the quality of water in a lake. Water quality measurements should include total phosphorus, water clarity, and measurements at discrete depths of water temperature and dissolved oxygen concentrations at the end of summer. The Ministry of the Environment’s Lake Partner Program can help municipalities fulfill their monitoring requirements. Through partnerships with other agencies and a network of volunteers, the program currently collects water quality samples from more than 1,000 locations across the province.

Introduction to lakeshore capacity assessment (1.0)

Purpose of the handbook (1.1)

For many people, the image of Ontario is synonymous with the image of our northern lakes. When they think of our province, they think of anglers casting for walleye in the early morning mist, children leaping from docks into clear, sparkling waters and the rugged, tree-lined shores made famous by the Group of Seven. There are more than 250,000 inland lakes that dot Ontario’s Precambrian Shield and these are an invaluable legacy for the residents of the province. Some people experience their beauty year round as residents. Others return every summer — some of them travelling great distances — for canoe tripping, fishing, cottaging, or to experience the solitude and the spiritual renewal that can be realized in these spectacular natural settings.

This handbook has been prepared as a tool to help protect the water quality of Ontario’s Precambrian Shield lakes by preventing excessive development along their shores. It has been developed by the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) in partnership with the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) and the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (MMAH), with input from a diverse group of stakeholders. The advice in this handbook is intended for municipalities on the Precambrian Shield that have inland lakes within their boundaries. As such, it will be most useful to municipal planners, technical staff and consultants working on water quality in inland lakes. Nevertheless, cottagers' associations, residents living on lakes, conservation authorities and proponents of development should also find it informative.

The Lakeshore Capacity Assessment Handbook is a guide and resource for municipalities. Lakeshore capacity assessment will help municipalities meet their obligation under the Planning Act to be consistent with the Provincial Policy Statement (2005).

This handbook also incorporates a revised provincial water quality objective for phosphorus, and references a dissolved oxygen criterion developed by the Ministry of Natural Resources to protect lake trout habitat in inland lakes on the Precambrian Shield.

The handbook will become the basis for training resource managers in municipalities, the private sector and within MOE, MNR and MMAH. This will help to ensure consistent use and interpretation of lakeshore capacity assessment policies, the Lakeshore Capacity Model and its assumptions.

Outline of the handbook

The Lakeshore Capacity Assessment Handbook is organized so that more general material is presented at the beginning of the handbook and an increasing level of detail is found as one proceeds through it. The early sections are therefore suitable for general audiences, while the later chapters are targeted at more technical audiences. The greatest level of detail is found in the appendices.

Section 1.0: Provides an introduction to lakeshore capacity assessment and outlines why it is needed, what it will achieve, and what effect it will have on future lake development in the province.

Section 2.0: Examines the relationship between phosphorus, dissolved oxygen and water quality. It outlines the rationale for and approach used in the revised provincial water quality objective for phosphorus and contains a brief description of the dissolved oxygen criterion for the protection of lake trout habitat.

Section 3.0: Presents the basics of lakeshore capacity assessment. This includes a discussion on where it may be applicable, when it should be considered, what it will tell the user and what is needed to carry it out.

Section 4.0: Presents more detail on lakeshore capacity assessment and outlines how to apply the Lakeshore Capacity Model, the recommended provincial assessment tool for lakeshore capacity planning. It also addresses the updated and standardized technical assumptions used in the model, the steps involved in running it and the expected results.

Section 5.0: Provides a brief overview of land use planning application and best management practices, what they can achieve and why they are useful to municipalities (or residents and cottagers' associations) for protecting lake water quality. It also briefly addresses phosphorus abatement technologies.

Section 6.0: Focuses on monitoring water quality: why it is important, what to monitor and how to do it. It also provides an overview of MOE's Lake Partner Program.

Section 7.0: A brief conclusion.

The appendices to the handbook contain the rationale for a revised provincial water quality objective for phosphorus for Ontario’s inland lakes on the Precambrian Shield, a list of resources, and MOE technical bulletins on water quality monitoring.

What is lakeshore capacity assessment? (1.2)

At its simplest, lakeshore capacity assessment is a planning tool that is used to predict how much development can take place along the shorelines of inland lakes on the Precambrian Shield (Figure 1) without impairing water quality (i.e., by affecting levels of phosphorus and dissolved oxygen).

Development is defined herein as any activity which, through the creation of additional lots or units or through changes in land and water use, has the potential to adversely affect water quality and aquatic habitat. Development includes the addition of permanent residences, seasonal or extended seasonal use cottages, resorts, trailer parks, campgrounds and camps, and the conversion of forests to agricultural or urban land.

Figure 1. Ontario’s Precambrian Shield (shaded area)

Lakeshore capacity assessment can be used in two major ways:

- To determine the maximum allowable development (in terms of number of dwelling units) that can occur on a lake without degrading water quality past a defined point.

- To predict the expected effect of future development.

The goals of lakeshore capacity assessment are to help maintain the quality of water in recreational inland lakes and to protect coldwater fish habitat by keeping changes in the nutrient status of inland lakes within acceptable limits. Lakeshore capacity assessment can be carried out on any inland lake on the Precambrian Shield, although its accuracy may decrease for lakes that don't stratify during the summer months (i.e., shallow lakes), or for lakes that fall beyond the calibration range of the model (see Section 4.3 for further details).

The goals of lakeshore capacity assessment are to help maintain the quality of water in recreational inland lakes and to protect coldwater fish habitat by keeping changes in the nutrient status of inland lakes within acceptable limits.

Lakeshore capacity assessment is based on controlling the amount of one key pollutant — phosphorus — entering a lake by controlling shoreline development. Phosphorus is a nutrient that affects the growth of algae and aquatic plants. Excessive phosphorus can lead to excessive algal and plant growth, which in turn leads to unsightly algal blooms, the depletion of dissolved oxygen and the loss of habitat for coldwater fish such as lake trout — a process known as eutrophication.

As outlined in Section 2.0, phosphorus comes both from natural and human sources. In the absence of significant agricultural or urban drainage, or point sources such as sewage treatment plants, the primary human sources of phosphorus to Ontario’s Precambrian Shield lakes are sewage systems from houses and cottages. Shoreline clearing, fertilizer use, erosion and overland runoff can also be important sources of phosphorus to inland lakes. Lakeshore capacity assessment helps planners understand what level of shoreline development can take place on an inland lake without appreciably altering water quality (i.e., beyond water quality guidelines or objectives for levels of phosphorus and dissolved oxygen).

MOE's mandate to protect water quality allows it to establish maximum phosphorus concentrations for individual lakes and to express these limits in terms of an allowable phosphorus load from shoreline development. Nutrient (phosphorus) enrichment may also reduce the amount of cold, well-oxygenated water available for fish requiring high levels of dissolved oxygen, such as lake trout. Development planning must protect fish habitat in accordance with the requirements of the federal Fisheries Act and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans policy for the management of fish habitat1, and the Provincial Policy Statement.

Lakeshore capacity assessment is a planning tool that will help municipalities achieve a consistent approach to shoreline development on inland lakes across the province. As noted previously, MOE recommends that municipalities use lakeshore capacity assessment to ensure sustainable development of the inland lakes in their region.

Lakeshore capacity assessment alone won't guarantee good water quality and healthy fish populations

There are many other pollutants — such as mercury, fuel, and wastewater from pleasure boats, which includes dish/shower/laundry water (grey water) and sewage (black water) — and other land uses — such as industrial use, urbanization, and intensive timber harvesting and agriculture — that can degrade water quality. To protect water quality, municipalities and lake users need to have regard for federal, provincial and municipal water-related laws, bylaws and policies. Municipalities also need to develop proactive land-use controls.

Handbook users should remember that lakeshore capacity assessment, while effective at protecting some aspects of water quality, is by no means a panacea for all water quality problems in inland lakes.

Water quality is only one of many factors that influence the development capacity of inland lakes

In some cases, water quality may not be the most critical factor in determining whether a lake has reached its development capacity. The development capacity of a lake is also influenced by fish and wildlife habitat, the presence of hazard lands, vegetation, soils, topography and land capability (the suitability of land for use without permanent damage). Other factors that influence development capacity include existing development and land-use patterns, as well as social factors such as crowding, the number and type of boats in use, compatibility with surrounding land-use patterns, recreational use and aesthetics. Lakeshore capacity assessment does not address these other factors.

The technical process of carrying out lakeshore capacity assessment will not, in and of itself, protect water quality — implementation is required

The information obtained from lakeshore capacity assessment — for example, the maximum number of lots or dwelling units permitted on a lake or the names of lakes that have been determined to be at development capacity — needs to be incorporated into the policies of a municipality’s official plan. The implementation of lakeshore capacity assessment is addressed in Section 3.4.

Lakeshore Capacity Assessment and Drinking Water

The outcome of the lakeshore capacity assessment will confer benefits on water quality that may, if a lake or watershed provides drinking water, also limit inputs of chemicals and pathogens to this drinking water source. A comprehensive strategy for the protection of drinking water supplies is under development. The Clean Water Act, passed into law in October 2006, takes a science and watershed-based approach to drinking water source protection as part of the Ontario government’s Source-to-Tap framework.

Why we need lakeshore capacity assessment (1.3)

The inland lakes on Ontario’s Precambrian Shield are a major environmental, recreational and economic resource for the province. We need lakeshore capacity assessment as a tool for at least three reasons:

- To help protect environmental resources

- To help protect recreational and economic resources

- To help municipal planning authorities meet their obligations under the Planning Act

Protecting environmental resources

Like other ecosystems, freshwater lakes are dynamic systems with an inherent resilience to stress — that is, they possess the ability to self-regulate and repair themselves. But, again like other ecosystems, inland lakes have a carrying capacity (limit) to the amount of stress they can tolerate. The near collapse of the Lake Erie ecosystem in the 1960s due to excessive phosphorus levels is one such example: a coordinated, basin-wide strategy was needed to reduce phosphorus levels and begin restoring the lake’s health.

An important water quality concern related to development on Ontario’s Precambrian Shield is eutrophication, which is caused by a high amount of phosphorus entering a lake. Unlike most pollutants, phosphorus isn't toxic to aquatic life. In fact, it is an essential nutrient that is supplied to the aquatic system from natural sources such as rainfall and runoff from the watershed.

However, when the amount of phosphorus entering a water body is excessive, it sets off a chain reaction. First, algae proliferate causing a loss in water clarity — the lake user may see this as greener or more turbid water, which is less aesthetically-appealing. In some cases, algal growth is dense and localized — this is called a bloom. Next, the algae die off and settle to the bottom of the lake, where bacteria begin the process of decomposition. This process consumes oxygen which, in turn, reduces the level of dissolved oxygen in the bottom waters and reduces the amount of habitat available for sensitive aquatic life such as lake trout. Lakes undergoing eutrophication may lose populations of lake trout and experience shifts in fish populations to more pollution-tolerant species.

Lakeshore capacity planning has been practiced for about 30 years in Ontario. During this time, MOE regional staff have modeled or accumulated files on more than 1,000 inland lakes. About 45 per cent of the lakes that have been determined to be at capacity to date are lake trout lakes in which a cold, well-oxygenated fish habitat is threatened by further shoreline development.

Lakeshore capacity assessment will help municipalities protect lakes that are at capacity against a further deterioration in water quality. It will also help to protect the water quality of lakes that have remaining development capacity, and help lakes to sustain healthy fisheries.

Protecting recreational and economic resources

Lakeshore capacity assessment will help to protect the significant economic values that are associated with Ontario’s inland lakes:

- Ontario residents own approximately 1.2 million recreational boats.2

- Anglers spend approximately $1.7 billion annually in Ontario on a range of goods and services related to recreational fishing.3

- Ontario’s Great Lakes and inland lakes support one of the largest commercial fisheries in the world, with a landed value of more than $40 million annually.4

- Crown lands and waters encompass approximately 87 per cent of Ontario’s land mass. Many visitors engage in resource-based tourism activities on these lands including, for 1999, more than 5.6 million Canadian, American and overseas visitors. These resource-based visitors spent almost $1.1 billion in Ontario.5

- Of the 5.6 million resource-based trips in Ontario in 1999, 4.8 million (86 per cent) were overnight trips. Many of these visitors were engaged in water-related activities: 50 per cent participated in water sports (including swimming); 39 per cent went hunting or fishing.6

The Planning Act and the Provincial Policy Statement

Protection of matters of provincial interest is now a responsibility that is shared between the Ontario government and municipalities. MOE and other Ontario government agencies no longer assess all development applications. As a result, municipalities need better tools to meet their obligations under the Provincial Policy Statement (PPS) to protect water quality and fish habitat and to evaluate the effect of developments on the local environment. Lakeshore capacity assessment is one such tool that will help municipalities meet these obligations. Under the 2004 amendments to the Planning Act all planning approval authority decisions made "shall be consistent with" the PPS, which came into effect on March 1, 2005 following an extensive consultation and review. This replaced the previous wording of the Planning Act which stated that approval authorities, when making decisions "shall have regard to" the PPS. Copies of the PPS (2005) are readily available online and directly from the Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing.

It is always important to remember that the PPS (2005) must be read in its entirety. With that in mind, land-use planners must consider many matters to reach a decision that is consistent with the PPS (2005). For lake trout lakes or any other water bodies, decisions shall be consistent with, among other PPS (2005) policies, its water quality policies and fish habitat policies, including any definitions where they apply.

What lakeshore capacity assessment will achieve (1.4)

Lakeshore capacity assessment is a useful planning tool that will enhance the effectiveness of the land-use planning and development process in a number of ways. It incorporates the concept of ecosystem sustainability into the planning process.

Lakeshore capacity assessment is built upon the knowledge that inland lakes have a finite and measurable capacity for development. Central to the province’s ecosystem approach to land- use planning is the concept that "everything is connected to everything else". Degradation of one element of an ecosystem (in this case, degradation of water quality) will ultimately affect other elements of the same ecosystem. Lakeshore capacity assessment is one tool that can assist in protecting the quality of water in inland lakes in the future. Protecting the quality of water in a lake will also help to protect its aquatic communities, coldwater fish habitat and the quality of water in downstream systems.

Lakeshore capacity assessment is consistent with watershed planning

The Ontario government recommends watershed planning as the preferred approach to water resource planning. Watershed planning takes a broad, holistic view of water resources and considers many factors including water quality, terrestrial and aquatic habitat, groundwater, hydrology and stream morphology (form and structure). Although lakeshore capacity assessment is more narrow in focus (as it considers only water quality), it is consistent with watershed management in that it considers upstream sources and downstream receptors when assessing the development capacity of a lake (e.g., PPS policy 2.2.1. a) which directs that planning authorities shall protect, improve or restore the quality and quantity of water by using the watershed at the ecologically meaningful scale for planning). It is a tool that will enable municipalities sharing a watershed to work together to protect the resource.

Lakeshore capacity assessment is consistent with the strategic shifts outlined in the report, Managing the Environment: A Review of Best Practices7

Lakeshore capacity assessment fits well with the strategic shifts outlined in the Managing the Environment report, commissioned by the Ontario government and issued in January 2001. Specifically, lakeshore capacity assessment reflects the shift towards:

- Place-based management using boundaries that make ecological sense

- Use of a flexible set of regulatory and non-regulatory tools

- A shared approach to environmental protection that includes the regulated community, non-governmental organizations, the public and the scientific/technical community

Lakeshore capacity assessment promotes land-use decisions that are based on sound planning principles and helps to address many relevant aspects of the Provincial Policy Statement (2005)

The implementation of lakeshore capacity assessment, together with the implementation of best management practices, will demonstrate sound planning principles at the municipal level by reflecting the land-use policies in a municipality’s official plan. As outlined in Section 1.3, lakeshore capacity assessment supports the protection of provincial interests identified in the Planning Act and the Provincial Policy Statement (2005). This includes protecting water quality, natural heritage features and communities.

Lakeshore capacity assessment encourages land-use decisions that maintain or enhance water quality

While the Ontario government maintains jurisdiction and legislative authority for water quality and quantity under the Ontario Water Resources Act and the Environmental Protection Act, municipalities are strongly encouraged to consider more restrictive procedures and practices to safeguard water resources. Lakeshore capacity assessment is a proactive method by which municipalities can determine the sustainability of shoreline development on inland lakes with respect to water quality. It will help protect or enhance water quality so that permanent and seasonal residents can continue to enjoy good water clarity. It will also help to protect fish habitat and fisheries.

Lakeshore capacity assessment encourages a clear, coordinated and scientifically sound approach that will be beneficial to stakeholder groups and may avoid or reduce land use conflicts

Lakeshore capacity assessment is grounded in science that has been used for many years. It was developed by the Ontario government to guide municipalities with their planning responsibilities. It will help municipalities determine their lakeshore development capacity as they develop or update their official plans. Municipalities will then be able to set long-term planning policies before development expectations are generated and investments are made in property acquisition and subdivision design.

Lakeshore capacity assessment encourages a consistent approach across the province

The Ontario government is promoting the use of this handbook and the Lakeshore Capacity Model to encourage a consistent approach across the province.

Lakeshore capacity assessment is cost effective

Duplication of effort is avoided when municipalities carry out lakeshore capacity assessment and then develop general policies that are expressed in official plans and zoning bylaws. This is also the case when a development proposal requires a proponent to deal with more than one municipality.

What the effect will be on future lake development (1.5)

There are currently more than 220,000 residential and cottage properties on Ontario’s inland lakes.8 Cottage development is sporadic and therefore difficult to predict. Annual demand for new lakeshore properties may increase somewhat in the future, but isn't expected to reach the high levels encountered in the late 1980s because of changes in disposable income and growing interest in recreational and retirement properties in warmer climates9.

Municipal use of lakeshore capacity assessment — in conjunction with the revised provincial water quality objective for phosphorus for inland lakes on the Precambrian Shield — may allow for fewer new residential and cottage lots on some lakes and more on others, as compared to the existing assessment procedure. The net effect is likely to be a redirection of development from lakes that are already well developed to lakes that are less developed.

Phosphorus, dissolved oxygen and water quality (2.0)

Link between phosphorus and water quality (2.1)

Phosphorus is an essential nutrient that is supplied to aquatic systems from natural sources such as rainfall and overland runoff, as well as human sources. Unlike most aquatic pollutants, phosphorus isn't toxic to aquatic life. High levels of phosphorus, however, can set off a chain of events that can have serious repercussions on the aesthetics of recreational waters and the health of coldwater fisheries.

The phosphorus concentration of a lake is one measure of the desirable attributes we wish to protect as the lake’s shoreline is developed. These attributes include clear water for recreation and a well-oxygenated habitat for coldwater fish.

For Ontario’s inland lakes on the Precambrian Shield, trophic (nutrient) status is determined by the level of phosphorus in the water (Table 1). Most lakes in the province of Ontario can be broadly characterized as being oligotrophic (low in nutrients) or mesotrophic (moderately nutrient-enriched), and most can accommodate small increases in phosphorus levels. However, all lakes have a finite capacity for nutrient assimilation, beyond which water quality is impaired. Excessive phosphorus loadings to a lake promote the growth of algae, sometimes leading to algal blooms on or beneath the lake’s surface. The proliferation of algae reduces water clarity, which lessens a lake’s aesthetic appeal. More serious effects may occur after the algae die and settle to the bottom. When this takes place, bacteria levels increase to decompose the algae and collectively their respiration consumes more oxygen in the water column. This means a loss of the cold, well-oxygenated habitat that is crucial to the survival of coldwater species such as lake trout. The ultimate outcome can be extirpation (local extinction) of the species.

The main human sources of phosphorus to many of Ontario’s recreational inland lakes are sewage systems from houses and cottages. Clearing the shoreline of native vegetation, use of fertilizers, stormwater runoff and increased soil erosion also can contribute significant amounts of phosphorus to a lake.

| Trophic status | Total phosphorus range (µg/L) |

|---|---|

| Oligotrophic | <10 |

| Mesotrophic | 10-20 |

| Eutrophic | >20 |

MOE's mandate for protection of water quality allows it to establish maximum phosphorus concentrations for individual lakes and express these limits in terms of the allowable phosphorus load from shoreline development. Since nutrient enrichment can also reduce the amount of cold, well-oxygenated water used by fish such as lake trout, MNR has developed a new criterion for dissolved oxygen to protect lake trout habitat.

Development planning must protect fish habitat in accordance with the requirements of the federal Fisheries Act and Fisheries and Oceans Canada policy for the management of fish habitat10. Projects that may alter fish habitat fall under the jurisdiction of Fisheries and Oceans Canada for review under section 35 of the Fisheries Act. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has negotiated agreements with some conservation authorities to carry out these reviews at varying levels, depending on the capability of the conservation authority. Fisheries and Oceans Canada has a similar agreement with Parks Canada to carry out section 35 reviews for projects in national parks, marine conservation areas, historic canals and historic sites.

Provincial water quality objective for phosphorus (2.2)

This section of the handbook provides an overview of the relationship between phosphorus and water quality and outlines the rationale for and approach used for the development of a revised provincial water quality objective for phosphorus. More detail is found in Appendix A, Rationale for a revised phosphorus criterion for Precambrian Shield lakes in Ontario.

Existing approach

The Ontario government’s goal for surface water management is Ato ensure that the surface waters of the province are of a quality which is satisfactory for aquatic life and recreation".11 The existing PWQO for total phosphorus was developed by MOE in 1979.12

It was founded on the trophic status classification scheme of Dillon and Rigler13, and was designed to protect against aesthetic deterioration and nuisance concentrations of algae in lakes, and excessive plant growth in rivers and streams.

Interim Provincial Water Quality Objective for total phosphorus (1979)

Current scientific evidence is insufficient to develop a firm objective at this time [i.e., 1979]. Accordingly, the following phosphorus concentrations should be considered as general guidelines which should be supplemented by site-specific studies:

- To avoid nuisance concentrations of algae in lakes, average total phosphorus concentrations for the ice-free period should not exceed 20 µg/L.

- A high level of protection against aesthetic deterioration will be provided by a total phosphorus concentration for the ice-free period of 10 µg/L or less. This should apply to all lakes naturally below this value.

- Excessive plant growth in rivers and streams should be eliminated at a total phosphorus concentration below 30 µg/L.

In 1992, the PWQO for total phosphorus was given interim status. This reflected both the uncertainty about the effects of phosphorus, and the fact that phosphorus isn't toxic to aquatic life. The interim PWQO doesn't explicitly distinguish between lakes in different regions of Ontario (i.e., Precambrian Shield versus southern Ontario). Instead, it sets different targets for lakes depending on whether they have naturally low productivity (total phosphorus less than 10 µg/L) or naturally moderate productivity (total phosphorus greater than 10 µg/L) (see sidebar).

In summary, the intent of the interim PWQO for total phosphorus in lakes is to:

- Protect the aesthetics of recreational waters by preventing losses in water clarity

- Prevent nuisance blooms of surface-dwelling algae

- Provide indirect protection against oxygen depletion

Need for a revised approach

The need to revise the approach for managing phosphorus stems from an improved understanding of the relationship between phosphorus concentrations in water and the resulting plant and algal growth in lakes and rivers. It also reflects an improved understanding of watershed processes, biodiversity and the assessment of cumulative effects. A revised approach would ensure adoption of these considerations in the water management process.

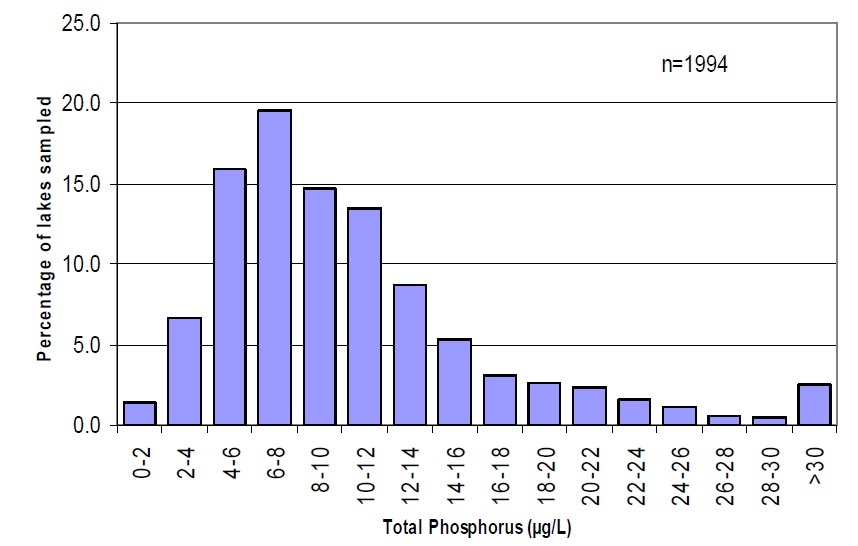

Although the existing, two-tiered guideline for total phosphorus in lakes has performed well for more than 30 years, it fails to protect against the effects of cumulative development. Further, it doesn't protect the province’s current diversity in lake water quality and its associated biodiversity. As illustrated in Figure 2, there is a wide range of nutrient levels in Ontario’s inland lakes, with a prevalence of oligotrophic lakes.

Figure 2. Distribution of total phosphorus concentrations in sampled Ontario lakes

(source: MOE Inland Lakes database, March 2004)

The logical outcome of the application of the Ontario government’s two-tiered 1979 phosphorus objective is that, over time, the quality of water in recreational lakes will converge on each of the two water quality objectives. This will produce a cluster of lakes slightly below 10 µg/L, and another slightly below 20 µg/L, thus reducing the diversity of water quality among lakes and, with it, the diversity of the associated aquatic communities.

Revised approach

The revised PWQO for lakes on the Precambrian Shield allows a 50 per cent increase in phosphorus concentration from a modeled baseline of water quality in the absence of human influence.

The revised approach has the following advantages:

- Each water body would have its own water quality objective, described with one number (i.e., 'undeveloped' or 'background' plus 50 per cent)

- Development capacity would be proportional to a lake’s original trophic status

- Each lake would remain closer to its original trophic status classification. A lake with a predevelopment phosphorus level of 10 µg/L could be developed to 15 µg/L, maintain its mesotrophic classification, and development would not be unnecessarily constrained to 10 µg/L

- The existing diversity of trophic status in Ontario would be maintained in perpetuity

Phosphorus and dissolved oxygen (2.3)

The lake trout, Salvelinus namaycush, is found in about 2,200 lakes in Ontario, most of which are on or near the Precambrian Shield. These lakes are noted for their relatively pristine water quality: they generally have high clarity, low levels of dissolved solids, organic carbon and phosphorus, high concentrations of dissolved oxygen, cool temperatures in bottom waters year round and relatively stable water levels. Self-sustaining populations of lake trout are found in these lakes because they provide the specific, narrow environmental conditions required by this species.

Ontario’s lakes were re-colonized by lake trout 10,000 years ago after the glaciers of the last Wisconsin Ice Age retreated. Populations have been largely isolated from one another since that time and adaptation to local conditions has led to genetically distinct, locally adapted stocks. The preservation of genetic diversity of the species requires conservation of individual populations through the protection of the habitat and water quality in the lakes in which they occur.

Lake trout are long-lived and late maturing, with females first spawning at six to ten years of age. This late maturation, combined with modest egg production and low recruitment rates, makes lake trout vulnerable to external factors that increase mortality. These factors include over-fishing and degradation or loss of spawning and summer habitat.

Loss of late summer habitat is influenced by phosphorus loading. In the southern part of their range, lake trout live in the hypolimnion during the summer. The hypolimnion is isolated from the atmospheric and photosynthetic supply of oxygen from the time when the lakes become thermally stratified during spring overturn until recirculation or turnover takes place in the fall. To sustain lake trout over the summer, the hypolimnion must contain enough dissolved oxygen.

When nutrient enrichment takes place as a result of shoreline development, the algae production-decomposition cycle depletes the oxygen in the deep waters of the hypolimnion.

Low concentrations of dissolved oxygen in bottom waters impair the lake trout’s respiration, and therefore its metabolism, which compromises its ability to swim, feed, grow and avoid predators. Studies have shown that juvenile lake trout need at least 7 milligrams (mg) of dissolved oxygen per litre (L) of water. Measured as a mean, volume-weighted, hypolimnetic dissolved oxygen concentration (MVWHDO), this level is also sufficient to make sure that natural recruitment takes place. The Ministry of Natural Resources has thus developed a criterion of 7 mg of dissolved oxygen/L (measured as MVWHDO) for the protection of lake trout habitat (references in Appendix B). The provincial water quality objective for dissolved oxygen allows for the establishment of more stringent, site-specific criteria for the protection of sensitive biological communities.14

The Province recommends that generally there will be no new municipal land use planning approvals for new or more intense residential, commercial or industrial development within 300 metres of lake trout lakes where the MVWHDO concentration has been measured to be at or below 7 mg/L. This recommendation also applies to lakes where water quality modelling has determined that the development of existing vacant lots, with development approvals, would reduce the MVWHDO to 7 mg/L or less. Preservation of an average of at least 7 mg of dissolved oxygen/L in the hypolimnion of Ontario’s lake trout lakes will help to sustain the province’s lake trout resources. For more information on sampling oxygen and calculating the MVWHDO concentration, please see the Technical Bulletin in Appendix C.

1 Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 1986. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans policy for the management of fish habitat. Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Ottawa. 28 p.

2 Great Lakes Regional Waterways Management Forum. 1999. The Great Lakes: A waterways management challenge. Harbor House Publishers, Inc. Michigan.

3 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 2003. 2003 Recreational Fishing Regulations Summary. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

4 Office of the Provincial Auditor of Ontario. 1999. 1998 Annual Report. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

5 Ontario Ministry of Tourism and Recreation. 2002. An Economic Profile of Resource-Based Tourism in Ontario, 1999. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

6 Ontario Ministry of Tourism and Recreation. 2002. An Economic Profile of Resource-Based Tourism in Ontario, 1999. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

7Executive Resource Group. 2001. Managing the Environment: A Review of Best Practices, Volume 1.

8 Cottage Life Magazine. 2004. Cottage Life Advertising Brochure.

9 Ontario Ministry of the Environment (Economic Services Branch). 1997. Economic Analysis of the Proposed Lakeshore Development Policy: Socio-economic value of water in Ontario. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

10 Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 1986. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans policy for the management of fish habitat. Department of Fisheries and Oceans. Ottawa.

11 Ontario Ministry of Environment and Energy. 1994. Water management: Policies, guidelines, Provincial Water Quality Objectives of the Ministry of Environment and Energy. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

12 Ontario Ministry of Environment and Energy. 1979. Rationale for the establishment of Ontario’s Provincial Water Quality Objectives. Queen’s Printer for Ontario.

13 Dillon, P.J. and F.H. Rigler 1975. A simple method for predicting the capacity of a lake for development based on lake trophic status. J. Fish. Res. Bd. Can. 32: 1519-1531.

14 Ontario Ministry of Environment and Energy. 1994. Water management: Policies, guidelines, Provincial