2018-2019 Chief Drinking Water Inspector annual report

Learn about the performance of our regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, and enforcement activities and programs.

Message from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector

I am pleased to present my annual report showcasing Ontario’s drinking water protection activities and results from April 1, 2018, to March 31, 2019. I am happy to say that Ontarians continue to enjoy clean and safe drinking water that is among the best protected in the world.

Here is a quick look at the 2018-2019 results:

- 99.9% of the over 522,000 drinking water tests from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario's strict, health-based drinking water standards.

- 99.5% of 659 municipal residential drinking water systems received an inspection rating indicating over 80% compliance with Ontario’s regulations. 72% of systems received a perfect 100% rating. For those that didn’t receive a perfect rating, examples of their non-compliance included having operation and maintenance manuals that did not meet requirements and not ensuring that continuous monitoring equipment performed tests at the required frequency.

- 94.9% of the over 69,000 test results met Ontario’s standard for lead in drinking water at schools, private schools and child care centres, with 97.6% of flushed samples meeting the standard. These lead exceedances typically occurred because lead was present in the facility’s plumbing. For those schools, private schools and child care centres where flushed test results did not meet standards, corrective actions were required, such as rendering the fixture inaccessible to children, replacing the fixture, installing a filter or additional flushing and resampling.

- There were 7,272 certified drinking water operators in Ontario to operate drinking water systems.

- Seven drinking water systems were convicted and fined a total of $80,650 for offences such as owners or operators not collecting enough drinking water samples for testing or owners employing people who did not have the proper training to run the systems.

The Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page of the Open Data Catalogue provides detailed information on the 2018-19 results.

This report demonstrates how the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks and its partners are helping protect Ontario’s drinking water through a framework that consists of strong legislation, stringent health-based standards, regular and reliable testing, highly-trained operators, regular inspections and a source water protection program. Because of the hard work of so many, Ontarians can be confident that their drinking water is safe to drink and that swift action is taken when that safety is at risk.

Ontario already has the most stringent provincial testing regime in Canada when it comes to lead in drinking water and we’ve made significant progress in reducing lead in drinking water.

Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health has not received any reports of lead toxicity in Ontario children that have been linked primarily to drinking water in the last 10 years. Blood lead levels of Canadians have also declined by over 70% in the past 40 years due to ongoing actions to reduce lead exposure from all sources.

Ontario’s drinking water protection framework was developed as a result of the Walkerton inquiry and the subsequent recommendations by Justice O’Connor in 2002. Since that time, we’ve taken numerous steps, including:

- Passing the Safe Drinking Water Act in 2002, which helped to implement Justice O’Connor’s recommendations and form the foundation for a stronger regulatory framework

- Implementing rigorous laboratory licensing requirements in 2003

- Implementing strict drinking water system operator training requirements in 2004

- Founding the Walkerton Clean Water Centre, a key training partner, in 2004

- Implementing stringent requirements on this ministry in 2005, such as the frequency of inspections

- Passing the Clean Water Act in 2006, which requires local areas to develop plans to protect sources of municipal drinking water

- Implementing a regulation in 2007 to protect children in schools, private schools and child care centres from being exposed to lead in drinking water. As a result, every school board in the province has drinking water sample results in the ministry’s drinking water system database dating back to 2008

- Implementing a quality management system in 2009 for the operation of municipal systems

- Developing all source protection plans by 2015 and continuing to carry them out

- Requiring, in 2017, that every drinking water fountain and tap serving drinking water to children in schools, private schools and child care centres be sampled for lead by 2022.

The ministry helps to ensure that safe, clean drinking water is available throughout the province as do our many partners such as water associations, conservation authorities, and the Ministry of Health. Here are a few examples of these collaborative relationships:

- The ministry is working with the Ontario Municipal Water Association on revisions to Ontario's Watermain Disinfection Procedure to clarify compliance requirements for the disinfection of repaired watermains.

- Conservation authorities prepare updates to source protection plans to ensure that new and changing drinking water systems are protected before they go into service.

- Local boards of health, which are overseen by the Ministry of Health, inspect small drinking water systems and consult where needed with local offices of the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks.

I want to thank all our collaborative partners for their hard work and dedication.

I would also like to thank my colleague Dr. David Williams, Chief Medical Officer of Health, for providing updates on the performance of small drinking water systems regulated by the Ministry of Health for this report.

It is a great honour to work with such a talented, dedicated and hardworking team and responsive and proactive partners. Protecting the province’s drinking water and water resources is part of our Made-in-Ontario Environment Plan to keep Ontarians safe and pass on a cleaner environment to future generations.

Melissa Thomson

Chief Drinking Water Inspector

Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks

Introduction

In Ontario, the regulation of drinking water systems is shared by two ministries, the Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks and the Ministry of Health.

The Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks regulates:

- Municipal residential drinking water systems that are owned by municipalities and supply drinking water to homes and businesses.

- Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems that are privately owned and supply drinking water all year round to people’s homes in places such as trailer parks, apartments and condominium building and townhouse developments where there are six or more private residences.

- Systems serving designated facilities that have their own source of water and provide drinking water to facilities such as children’s camps, schools, health care centres and senior care homes.

The Ministry of Health regulates:

- Small drinking water systems that provide drinking water to the public where no municipal drinking water system exists, such as restaurants, bed and breakfasts, campgrounds and other public settings.

Ontario’s drinking water protection framework

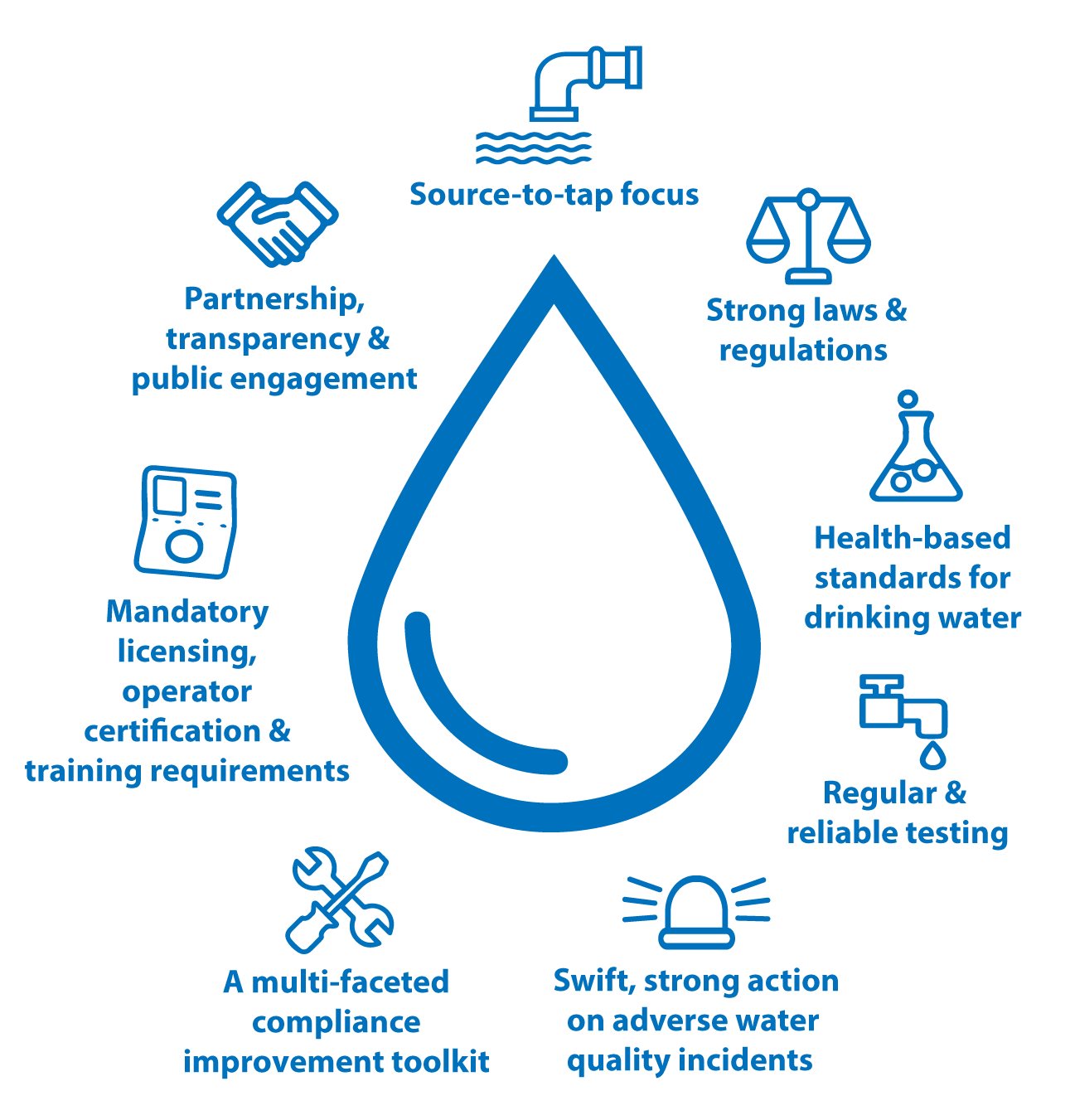

The events of Walkerton in 2000 and the findings of the O’Connor Inquiry called for an important shift in the way Ontario’s drinking water was protected. Based on the lessons learned, the province developed its drinking water protection framework and transformed how our drinking water is safeguarded. The key lesson was that protecting drinking water requires multiple barriers and checks and balances to be in place from the drinking water source through to treatment and distribution. Having this framework helps to provide context and guidance for the development of new policies to protect drinking water.

The framework consists of initiatives that help prevent contamination, detect and address drinking water quality issues and take other actions such as reaching out and educating the regulated community and informing the public, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Drinking water protection framework

The body of this report will follow these headings of the drinking water protection framework.

Source-to-tap focus

Ontario communities rely on safe and clean drinking water that needs to be protected for current and future generations. That’s why the Made-in-Ontario Environment Plan commits to protecting the Great Lakes and inland waters and promoting sustainable water use. The province recognizes that preventing contamination and depletion of our lakes, rivers, and groundwater sources is an important first step in protecting drinking water and is part of Ontario’s protection framework.

Minister-approved source protection plans are in place that cover all 38 watershed-based source protection areas across Ontario. These plans contain locally developed policies that, when implemented, protect existing and future sources of municipal drinking water. Together, these plans protect nearly 440 municipal drinking water systems, over an area where more than 95% of Ontario’s population lives.

Local source protection committees across Ontario continue to engage their local municipalities, First Nations communities and stakeholders to keep source protection plans up to date and support policies that protect drinking water sources from threats.

Source protection authorities report annually on their progress, with results showing:

- 97% of plan threat policies that address significant risks to municipal drinking water sources are being implemented

- 1,636 signs have been installed on municipal and provincial roadways to raise public awareness of source water protection zones

- Provincial ministries have completed 98% of their review of previously issued permits and approvals to conform with source protection plan policies.

In 2018, a new regulation (O. Reg. 205/18 under the Safe Drinking Water Act) came into effect to include new or changing municipal drinking water systems in source protection plans before water is provided to the public. A change to a drinking water system such as adding a new well or increasing the water-taking rate can change the protection zones around that system. The new regulation requires these protection zones to be updated within the source protection plan so that the water source is protected before it is used. As of September 16, 2019, eight of the previously approved source protection plans have been amended to include sources of drinking water for 18 new groundwater wells.

Provincial ministries are undertaking a range of actions to implement the plans and protect drinking water sources. For example, all incoming applications to the Municipal Drinking Water Licensing Program are screened to determine if fuel storage or handling by the system operators would be a significant risk to drinking water sources. Where this is the case, conditions are included in the licence to help make sure the risk is managed.

Meanwhile, the ministry continues to provide the training required by municipally-appointed risk management officials to enable them to locally manage risks to drinking water sources, and to collaboratively develop outreach materials to make it easier for municipalities to educate their residents about drinking water source protection.

Strong laws and regulations

The Safe Drinking Water Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Health Protection and Promotion Act and their regulations are key legal foundations for the drinking water protection framework. These laws establish the rules that must be followed by people who are involved in protecting drinking water.

The Safe Water Drinking Act

The Safe Drinking Water Act and its regulations deal with various matters such as treating and distributing drinking water, setting drinking water quality standards, certifying operators and licensing laboratories. In this section, an update is given on the Compliance and Enforcement regulation and the lead regulations that are associated with this legislation.

Compliance and Enforcement regulation

The Compliance and Enforcement regulation of the Safe Drinking Water Act sets out responsibilities for the government itself to be legally accountable for its oversight role to protect drinking water. The responsibilities include:

- Inspecting all municipal residential drinking water systems annually

- Ensuring at least one out of three inspections of each municipal residential drinking water system is unannounced

- Inspecting all licensed and eligible laboratories a minimum of twice a year and ensuring that at least one inspection is unannounced

- Reporting on any requests from the public asking for an investigation of an alleged contravention of the Safe Drinking Water Act or any of its regulations.

The Compliance and Enforcement regulation requires government to report on whether it met its obligations under the Safe Drinking Water Act. In 2018-19, Ontario met all requirements and no member of the public made an application for an investigation.

Lead reduction strategy

Ontario’s drinking water is tested for lead. Treated water typically meets Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standard for lead, but sometimes older distribution pipes, home service lines and/or plumbing wear away or corrode, which can cause lead to enter the water being distributed to taps.

When lead was found in tap water taken from older homes in London, Ontario, in 2007, the ministry took action. The ministry required municipalities to sample for lead in people’s homes and to prepare corrosion control plans if lead became an ongoing problem.

In 2007, the ministry also implemented a new regulation to protect children from being exposed to lead in drinking water and further strengthened this regulation in 2017. Here are some updates on efforts to address lead in drinking water for 2018-19:

Corrosion control

The ministry has been working with municipalities since 2007 to reduce lead levels where they exceed the provincial standard on an ongoing basis. Since 2010, 20 municipalities were required to prepare strategies to control lead levels, including actions such as:

- Altering water treatment processes and using chemical additives that prevent corrosion of pipes

- Replacing lead service lines

- Upgrading their water treatment plant

- Encouraging homeowners to allow or conduct sampling and testing, and to replace fixtures or plumbing that contain lead.

Currently, 10 municipalities have fully implemented their lead control strategies with 10 others making significant progress.

Each year, the ministry reviews lead sampling results to determine if more municipalities should be required to develop lead control strategies. In 2018-19, no additional municipalities were required to develop a lead control strategy based on the current Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standard of 10 micrograms per litre.

The Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page of the Open Data Catalogue provides additional information on these systems.

Drinking water tap and fountain inventory at schools, private schools and child care centres

A plumbing sample is a drinking water sample taken from a tap and is intended to test the quality of water being consumed. Studies have shown that lead levels in drinking water taken from plumbing can vary substantially between individual taps and fountains. That’s why in 2017, requirements were strengthened to ensure every drinking water fountain and tap serving drinking water to children in schools, private schools and child care centres is sampled for lead by 2022. To check whether each drinking water fixture is tested for lead, the ministry asked schools, private schools and child care centres to submit an inventory detailing the number of drinking water fixtures in their facilities and their progress towards completion.

As of June 12, 2019, of the over 11,000 facilities registered with the ministry, 81% have sent in a drinking water fixture inventory.

An assessment of those inventory lists shows that:

- Over 94,000 individual drinking water fixtures have been identified

- Of those, over 29,000 fixtures have been sampled.

These results indicate good progress is being made to have every drinking water fountain and tap serving drinking water to children in schools, private schools and child care centres sampled for lead by 2022. The ministry will continue to encourage facilities that have yet to submit their fixture inventory to do so and will track the progress of fixture sampling until the 2022 deadline.

The Clean Water Act

The Clean Water Act and its regulations protect existing and future sources of municipal drinking water. It does this by enabling local communities to develop plans to identify and address risks to the water sources for their drinking water systems. Further information on the results of the source protection plans can be found in the section called "Source-to-tap focus".

The Health Protection and Promotion Act

The Health Protection and Promotion Act regulates the provision of safe drinking water by small drinking water systems. It does this by enabling local boards of health to undertake risk-based assessments and produce a customized site-specific plan for each small drinking water system to keep their drinking water safe. Further information on the results of the Small Drinking Water Systems Regulation can be found in the section called "Small Drinking Water Systems Program — Ministry of Health".

Health-based standards for drinking water

Ontario has health-based drinking water quality standards that establish the maximum allowable levels for chemicals, radiological chemicals and microbiological organisms. The protection framework relies on the setting of health-based standards because test results are compared against the standards to determine if the drinking water is safe to drink.

Ontario generally bases its standards on the Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines which are developed by Health Canada through the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water. These guidelines may be adopted by provincial and territorial governments.

With any new or updated federal guideline, Ontario’s Advisory Council on Drinking Water Quality and Testing Standards and the ministry review the implications of adopting the guideline as a standard. Before making any regulatory changes, the ministry consults through the Environmental Registry.

For example:

- The new standard for haloacetic acids, which went through consultation in 2014, will come into effect on January 1, 2020, along with its associated reporting requirements.

- In March 2019, Health Canada revised the guideline for lead in treated drinking water from 10 to 5 micrograms per litre. The Advisory Council and the ministry are currently reviewing the revised guideline and will engage with stakeholders to consider whether to adopt Health Canada’s reduced lead guideline.

Regular and reliable testing

Ontario’s drinking water is carefully monitored through regular testing by certified operators who take thousands of drinking water samples every year which are tested at provincially licensed and eligible laboratories for microbiological organisms and chemical substances. Drinking water quality test results are a good way to demonstrate the quality of drinking water and provide ongoing evidence of a system’s ability to provide safe drinking water. This is why the regular and reliable testing of drinking water is an essential part of the protection framework.

In Ontario, when systems have test results that do not meet standards, this often relates to microbiological and chemical exceedances. Corrective actions can include adjustments to treatment equipment or other operational activities. Successful implementation of these actions is often confirmed by resampling.

The percentage of test results meeting standards for the three system types are given in the following points.

Overall, in 2018-19:

- 99.87% or 522,231 of the 522,921 drinking water test results from 661 municipal residential drinking water systems met the standards. The results identified as not meeting the standards represent 690 test results, of which the majority were microbiological exceedances. Chemical parameter exceedances such as arsenic and fluoride accounted for only 131 exceedances.

- 99.66% or 44,121 of the 44,272 drinking water test results from 445

footnote i of the 458 registered non-municipal year-round residential systems met the standards. The results identified as not meeting the standards represent 151 test results, of which the majority were microbiological exceedances. Chemical parameter exceedances such as nitrate accounted for only 56 exceedances. - 99.61% or 63,075 of the 63,325 drinking water test results from 1,326

footnote ii of the 1,431 registered systems serving designated facilities met the standards. The results identified as not meeting the standards represent 250 test results, of which the majority were microbiological exceedances. Chemical parameter exceedances such as nitrate and fluoride accounted for only 69 exceedances.

To learn more about how exceedances to standards are addressed, see the section on "Swift, strong action on adverse water quality incidents".

Lead test results in plumbing

This section presents summary highlights of test results for lead in plumbing.

Municipal residential and non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

As discussed in the section on "Strong laws and regulations", in 2007 Ontario made it mandatory for municipal residential drinking water systems to test tap water in plumbing for lead. Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems were also required to do the same. The data for both system types is given in Table 1 and, as can be seen, most of the test results met the standard for lead in 2018-19.

| Drinking water facility type | Parameter | Total number of test results | Number of lead exceedances (of total number of test results) | Percentage of test results meeting standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal residential systems | Lead in plumbing |

5,262 | 236 |

95.52 |

| Non-municipal year-round residential systems | Lead in plumbing |

1,371 | 16 |

98.83 |

Schools, private schools and child care centres

Lead in drinking water is a significant health concern especially for children age six and under, as it could negatively impact infant brain and nervous system development. The province requires schools, private schools and child care centres to:

- Flush plumbing, either weekly or daily depending on risk factors. The flushing process gets rid of water that has been sitting in the facility’s plumbing, reducing the potential for any lead to leach into the drinking water from plumbing components that may contain lead.

- Sample for lead in every drinking water fountain and tap serving drinking water to children in child care centres, schools and private schools with a primary division by January 1, 2020 and in all other schools by 2022. At a minimum, on an ongoing basis once all drinking water fixtures have been sampled at least once, take a set of samples from at least one tap or fountain used to provide drinking water or used in food preparation for children and test for lead annually or, under certain conditions, every three years.

- Report lead levels that do not meet the provincial standard to this ministry as well as the local health unit and the Ministry of Education.

- Take corrective actions to address high levels of lead in drinking water. Facilities must take immediate action, at any tap or fountain, where a test result from a flushed sample does not meet the standard by making the tap or fountain inaccessible to children by disconnecting or bagging it until the issue is resolved. Corrective actions could include replacing the fixture, increased flushing, installing a filter or other device that is certified for lead reduction, or taking any other measures as directed by the local medical officer of health.

This ministry checks that corrective actions issued by the local medical officer of health are implemented by school boards and owners/operators of private schools and child care centres.

In 2018-19:

- 94.91% of 69,730 test results met the standard for lead in drinking water from schools, private schools and child care centres. Of these, 97.55% of 34,770 flushed test results and 92.29% of 34,960 standing test results met the standard. School, private school and child care facility operators are required to report every exceedance of the standard to the local public health unit. All flushed exceedances require the facility to ensure the drinking water fixture remains out of use until the issue is resolved. Resolutions can include replacing the fixture, installing a filter, increased flushing or any other actions prescribed by the local public health unit.

The fact that fewer flushed test results than standing test results exceeded the standard is consistent with previous years and demonstrates that flushing is an effective way to temporarily reduce lead levels below the standard for lead. More permanent solutions include replacing the fixture or installing and maintaining a filter.

| Parameter | Total number of results | Number of lead exceedances (of total number of results) | Percentage of test results meeting Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standard for lead |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead - Flushed | 34,770 | 853 | 97.55 |

| Lead - Standing | 34,960 | 2,696 | 92.29 |

| Lead – Total for Standing and/or Flushed | 69,730 | 3,549 | 94.91 |

To find out test results for your local school, private school or child care centre you can contact them or download the file at the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement Catalogue page on the Open Data Catalogue — open the spreadsheet called "Test Data – Raw Data" and search for the name of your school or child care facility.

Highlight: Going beyond requirements

The Greater Essex County District School Board went beyond the basic requirements to track information about when a school’s plumbing is flushed by implementing an electronic system.

The electronic system sends supervisors an immediate notification when custodians have not logged their flushing activities — a mandatory task to be completed prior to the entry of students at the beginning of each school week or day. This allows for the issue to be addressed right away.

The school board began piloting this electronic system in four schools at the end of the 2017-2018 school year and fully implemented it in all of its 70 schools by October 2018.

Swift, strong action on adverse water quality incidents

As part of the protection framework, the government oversees, monitors and acts if an adverse water quality incident such as an adverse test result or operational issue occurs to address any potential threat to the safety of Ontario’s drinking water. Operational issues may include inadequate disinfection or equipment failure.

The report of an adverse water quality incident does not necessarily mean the drinking water from a drinking water system is unsafe. It indicates that a water quality standard was exceeded or that there is an issue within a drinking water system that needs to be addressed.

If an adverse test result is identified at a laboratory, the laboratory must immediately notify the owner or operator of the system, the ministry’s Spills Action Centre, and the local medical officer of health.

The owners or operators of the drinking water system must also immediately notify the ministry’s Spills Action Centre and the local medical officer of health. This duplication of reporting is one of the checks and balances of the drinking water protection framework and helps to ensure all appropriate actions are taken.

Ministry inspectors and local public health units work with affected system owners and operators to resolve the issue. This could include resampling and retesting or fixing the operational issues.

Overall results show that:

- 371 municipal residential drinking water systems reported 1,265 adverse water quality incidents. In addition to test results, incidents include operational events such as watermain breaks, turbidity and chlorine readings. These operational events account for more than half of the adverse water quality incidents reported.

- 181 non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems reported 686 adverse water quality incidents. The number of adverse water quality incidents for non-municipal year-round residential systems has increased significantly from 428 in 2017-18 to 686 in 2018-19. This year-over-year variation can be attributed largely to drinking water systems that reported a large volume of turbidity (i.e. cloudy water) incidents for 2018-19.

- 283 systems serving designated facilities reported 462 adverse water quality incidents. The most common incidents were related to chlorine readings.

For additional information on these results, please visit the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement webpage of the Open Data Catalogue.

Drinking water advisories

Boil water advisories and drinking water advisories are issued by the local medical officer of health if there is a concern that drinking water may not be safe for public consumption. Advisories may be issued due to a known contaminant or as a precaution due to potential or suspected contamination.

A boil water advisory instructs users to boil any water that may be used for purposes such as drinking or cooking. This type of advisory would be used when microbiological contamination has been detected as an adverse water quality incident has occurred, or as a proactive measure where it is suspected. A drinking water advisory is issued when boiling water is ineffective at removing or reducing the risk of a contaminant, such as sodium.

If bacteria, such as E. coli, may have entered the water supply, communities will be advised to boil their water before consuming it. However, if chemical contaminants may be present in the drinking water supply and cannot be removed by boiling or disinfecting the water, a drinking water advisory will be issued. Consumers are advised to use an alternate water supply until further notice. The local medical officer of health will issue advisories to the public through the media, by door-to-door notification or public posting of notices.

Drinking water advisory notices are tools used to protect consumers when the safety of the drinking water may be in question, and as a precautionary measure during times of system maintenance such as watermain repairs. They are issued using a risk-based approach and remain in place until corrective actions have been taken and the health unit is satisfied that the water does not pose a health risk. In most situations, system owners are able to quickly fix the issue, and the advisory is lifted within one to two weeks. In some cases, actions such as designing and installing new treatment are required to resolve the issue and the advisory may remain in effect for longer periods of time.

Any water advisory that remains in place for longer than 12 months is considered a long-term boil water or drinking water advisory. Long-term advisories typically require significant corrective actions, such as the installation or upgrading of the water treatment plant to resolve the issue. A medical officer of health will only lift the advisory once satisfied that all corrective actions have been taken and that the situation has been remedied. In 2018-19, one municipal residential drinking water system continued to have a drinking water advisory in place. For more information on this system, see the section called Highlight: Finding a long-term solution to a drinking water advisory.

Highlight: Finding a long-term solution to a drinking water advisory

The Lynden Drinking Water System has had lead in its distribution system. An advisory was issued to the Lynden Drinking Water System in 2011, and remains in place, due to re-occurring high lead levels in the distribution system. Although most lead sample results have remained below the provincial standard, the advisory will stay in place until lead concentrations are stable. The municipality continues to assess and address the source of lead and to offer residents on-tap filters certified for lead reduction. The municipality has selected a new well that they drilled and plans to add a new treatment facility to that well in the future as a long-term solution to the issue. The ministry continues to work closely with the municipality to make sure it complies with the corrective actions indicated by the public health unit and has approved the design of the new water treatment plant submitted by the municipality.

A multi-faceted compliance improvement toolkit

A critical component of the drinking water protection framework includes a range of activities that the ministry undertakes to improve compliance with regulatory requirements:

- Providing information to increase the regulated community’s understanding of their responsibilities

- Targeted inspections to confirm compliance by the regulated community

- Where necessary, enforcement actions to address significant non-compliance issues

All efforts are based on the level of risk posed by the non-compliant behaviour.

This section highlights the results from inspections and enforcement actions.

The ministry’s comprehensive and routine inspection program help assure the public that owners and operators of drinking water systems and owners of laboratories are fulfilling their legislated obligations.

Municipal residential drinking water systems

All municipal residential drinking water systems are inspected at least once a year. During an inspection, the inspector evaluates requirements such as the operation of the treatment system, policy and procedures, sampling and monitoring, operator certification, reporting and corrective actions. In 2018-19, the ministry inspected all 659

Each system is assigned an inspection rating that reflects how well the system complied with requirements. Of the 659 inspections conducted, 656 or 99.5% received an inspection rating greater than 80%, with 477 or 72% scoring 100%. Non-compliance activities ranged from not maintaining secondary disinfection to exceeding the flow rate specified in the permit and licence.

In cases where the inspection identifies a problem, the inspector can work with the system owner to bring the system into compliance or issue an order that prescribes corrective actions within a certain timeframe. In 2018-19, the ministry issued two orders to two different systems. One order directed the owner to confirm that certified equipment had been installed and the other one directed the owner to modify the system’s sodium sampling for a specified time. Both orders have been complied with.

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

Unlike municipal drinking water systems that supply drinking water to most of Ontario and are inspected annually, non-municipal year-round drinking water systems generally supply water to a very small number of people in a localized area, such as a mobile home park. Given the smaller scope of these systems to impact public health broadly, the ministry developed a risk-evaluation methodology to prioritize when and how often an inspection of a non-municipal year-round drinking water system is needed. This risk evaluation is based on factors such as compliance history, the number and reasons for any adverse water quality incidents and input from local public health units. Each year a risk evaluation is performed with up-to-date information to identify systems with the greatest need for improvement.

The ministry applied the risk-evaluation methodology to all 458 systems registered with the ministry and as a result inspected 110. These 110 inspections were completed, and five orders were issued to five systems in response to non-compliant activities. For example, one order directed the owner to ensure that at least one water sample is taken and tested for chemical parameters at the correct frequency. Of the five orders, one order has been fully complied with and the ministry is working with the remaining owners to address their non-compliance issues.

In between inspections, the ministry developed a strategy to assist non-municipal year-round residential system owners and operators to achieve compliance by providing a consistent understanding of regulatory responsibilities through a range of education and outreach tools and ongoing communication.

Story from the frontline: Making a difference

A ministry inspector made a difference in the lives of about 30 people in eastern Ontario by helping to ensure they have safe water. A mobile home park got its water from a surface water source that was often cloudy. The cloudy water frequently led to the shutdown of the water treatment plant so that repairs could be made. This left the residents of the mobile home park without a dependable source of drinking water. The ministry inspector suggested getting treated water trucked in. In late 2018, the surface water treatment plant was replaced by a storage tank to accept transported water. This change significantly improved the consistency and reliability of the drinking water for the mobile park residents.

Drinking water systems operated by local services boards

These boards are volunteer organizations that are set up in rural areas where there is no municipal structure. They have the authority to deliver services such as water, fire protection and garbage collection. The seven drinking water systems operated by these boards are included in the 458 non-municipal year-round residential systems registered with the ministry in 2018-19.

In 2018-19, the ministry inspected all seven drinking water systems run by these boards and found 45 non-compliance issues that commonly included primary treatment, sampling schedules and reporting. The ministry worked with the owners and operators to resolve any non-compliance issues that were identified. As a result, no orders were issued.

Systems serving designated facilities

As with non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, the ministry used a risk-evaluation methodology to assess all 1,431 systems serving designated facilities and as a result inspected 251. The ministry issued four orders to four systems. For example, one order directed the owner/operator to prepare a written action plan and adequately maintain free chlorine residual in treated water prior to it entering the distribution system. Three orders have been complied with and the ministry is working with the remaining owner to address the non-compliance issue.

For detailed information on these systems, please visit the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement webpage of the Open Data Catalogue.

Story from the frontline: Taking proactive actions

A ministry environmental officer inspected a drinking water system serving a school that was part of a school board in southern Ontario. During the inspection, the officer noticed several problems, such as a failure to collect required samples for testing, issues with operating and maintaining the system and not giving proper notification when an adverse water quality incident occurred.

The officer anticipated that these non-compliant activities were likely to be found at other schools owned by the same school board. To be proactive, the ministry inspected eight other drinking water systems operated by the school board and found similar problems.

Ministry environmental officers collaboratively worked with the school board to bring its drinking water systems into compliance. Follow-up inspections demonstrated successful outcomes of this work because compliance with Safe Drinking Water Act requirements had significantly increased.

Schools, private schools and child care centres required to test for lead

The majority of the over 11,000 schools, private schools and child care centres that are required to test for lead in their plumbing get their drinking water from their local municipality. Treated water from Ontario’s municipalities typically meets Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standard for lead, but often plumbing within a building or drinking water fixtures contains small amounts of lead which can enter the water being consumed. Historically, drinking water test results in most schools, private schools and child care centres have met the standard for lead after flushing, and as such, the ministry takes a much more targeted outreach and compliance approach for these facilities.

The ministry’s water inspectors review all lead exceedances at schools, private schools and child care centres to ensure incidents have been appropriately addressed and that any corrective actions issued by the local medical officer of health have been followed. In 2018-19, inspectors followed up with 1,105 facilities about their 3,549 lead exceedances. For more information on these lead exceedances, see Table 2.

In addition to managing the 3,549 lead exceedances, the ministry conducts inspections of schools, private schools and child care centres. To identify these facilities for inspection, the ministry uses a risk-based approach which involves reviewing factors such as inspection history, submission of an inventory of drinking water fixtures and sampling history. In 2018-19, the ministry’s water inspectors inspected 172 schools, private schools and child care centres to assess compliance with sampling and flushing requirements, along with looking at records and other administrative items. Water inspectors worked with facility owners and operators to resolve any non-compliance issues that were identified. As a result of the inspections, no orders were issued.

The ministry also audits any facility that is asking to move to a less stringent sampling schedule — from taking samples every year to every three years. In these cases, a compliance audit is conducted to ensure that all of the facility’s past test results have been taken according to the rules and that there have been no exceedances for a period of three years. In 2018-19, the ministry conducted 131 compliance audits.

For detailed information on these schools, private schools and child care centres, please visit the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement webpage of the Open Data Catalogue.

Licensed and eligible laboratories

All laboratories permitted to test drinking water are inspected a minimum of two times per year. There are a total of 54 laboratories licensed to performing drinking water testing including one outside of Ontario and in 2018-19, the ministry inspected all of them twice. During an inspection, the inspector evaluates requirements such as policy and procedures, methodology, document and record-keeping practices and reporting. An overall rating of how the laboratory met the requirements during the inspection is then calculated. All inspection ratings were greater than 70%, with 42% receiving a rating of 100%.

For those not receiving 100%, much of the non-compliance was related to the testing methods used for drinking water analysis at licensed laboratories. The testing methods were appropriate for drinking water testing and approved for use by the ministry, however, it was identified that the documentation was not current and reflective of laboratory practices. The non-compliant activities identified with the testing methods did not impact the reliability of the test results and the ministry worked with the laboratories to bring them into compliance.

The ministry issued five orders to five licensed laboratories in 2018-19. For example, these orders directed the laboratories to stop analyzing drinking water samples for chemicals that they are not authorized to test for and to make sure that people on temporary assignment continue to get training. The ministry’s laboratory inspectors issued orders because they observed significant non-compliant activities during their inspections that could affect the reliability of the drinking water testing that the laboratories were performing. As owners, operators and the ministry must rely on drinking water test results to confirm that the drinking water meets standards, it is critical that licensed laboratories comply with all requirements. In all cases, all orders have been complied with.

For detailed information on these laboratories, please visit the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement webpage of the Open Data Catalogue.

Convictions

Ontario has a strict enforcement policy when it comes to upholding the laws that protect drinking water. If those who are responsible for providing safe drinking water engage in significant non-compliant activities, they may face serious consequences. In 2018-19, owners, operators and subcontractors working at seven drinking water systems were convicted and fined a total of $80,650 for violating the requirements of Ontario’s regulations (see Table 3). Many of the offences were related to the owners or operators not collecting enough drinking water samples for testing or owners employing people who did not have the proper training to run the systems.

Further information on these convictions is given on the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page on the Open Data Catalogue.

| Facility Type | Number of facilities | Number of cases with convictions |

Fines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipal Residential Drinking Water Systems |

2 | 2 | $35,000.00 |

| Non-Municipal Year-Round Residential Drinking Water Systems |

3 | 3 | $30,500.00 |

| Systems Serving Designated Facilities |

2 | 2 | $15,150.00 |

| Schools, private schools and child care centres | 0 | 0 | $0 |

| Licensed Laboratories | 0 | 0 | $0 |

| Total | 7 | 7 | $80,650.00 |

Story from the frontline: Strong enforcement for failing to protect drinking water

A successful investigation can have positive effects beyond the conviction. Non-compliance activities were discovered during an inspection of a drinking water system that supplied water to a trailer park, putting up to 500 residents at risk of receiving unsafe drinking water.

The investigator assigned to the case found that the company hired to operate the drinking water system used an operator with an expired certificate, failed to report adverse test results and failed to take required drinking water samples.

The company that operated the system was charged through the courts and fined $20,000.

Through the process of the investigation, the owner of the trailer park came to realize that it is not enough to hire people without overseeing their work. As a result, the owner implemented new checks and balances to oversee the services being provided not only at this trailer park but also at other trailer parks that he owned. For example, the owner established:

- Contact with the area drinking water inspector seeking clear direction on the legal requirements to educate himself

- A clearer, more concise contract with the operating company

- An understanding with the operating company that he was to be copied on all information and issues pertaining to his drinking water systems.

Mandatory licensing, operator certification and training requirements

Licensed municipal drinking water systems, licensed laboratories, and trained and certified drinking water system operators across the province are among the key elements of the protection framework. Operating a drinking water system and testing the water produced by a drinking water system are important responsibilities in any community.

Municipal Drinking Water Licensing Program

In the past, certificates of approval issued by a director at this ministry gave municipalities the authority to establish, replace, alter, use or operate new or existing municipal drinking water systems or parts of their systems. The Municipal Drinking Water Licensing Program, which the ministry implemented in 2009, transformed the approvals framework by extending the focus from the design, construction and operations of the system to the ongoing management of all aspects of the system. The concept of pre-authorizations of future alterations to the system was also introduced with the launch of the licensing program. These pre-authorizations allow an owner to make certain changes to their system without coming to the ministry for approval, which has resulted in significant cost and time savings for municipalities.

The program also requires that the licence be reviewed every five years for each system. The ministry entered a licence renewal cycle in 2019 which will be complete by 2021.

The licensing program mandates that all municipal residential drinking water systems incorporate a quality management system into the operation and management of their systems. The Drinking Water Quality Management Standard provides a framework for operating authorities to develop and document management policies, processes and procedures.

Quality management systems endorse a proactive and preventative approach, which requires the adoption of best practices and continual improvement. The Drinking Water Quality Management Standard encourages a "Plan-Do-Check-Improve" management cycle for systems. All municipal residential drinking water systems have a Quality Management System in place.

Laboratory licensing

Laboratories play an important role in the protection of drinking water because they test drinking water to make sure that it meets Ontario’s drinking water standards. The law requires that laboratories be accredited, meaning they must complete their work diligently and competently as judged by international standards.

The ministry’s laboratory licensing program confirms that laboratories operating within Ontario use approved test methods and have policies and procedures in place to satisfy reporting and record-keeping requirements. Laboratories located outside of Ontario that meet Ontario’s accreditation and inspection requirements can be placed on a list which makes them eligible to test drinking water samples from Ontario. In 2018-19, one such laboratory was granted testing privileges. In all, there are a total of 54 laboratories licensed to perform drinking water testing including the laboratory outside of Ontario.

Operator certification and training

Skilled and competent drinking water system operators are crucial to maintaining safe water quality. They operate disinfection and treatment equipment, respond to equipment alarms and test and treat drinking water to help ensure that it is safe to drink. Ontario helps to ensure that drinking water systems maintain fully qualified and trained staff primarily through the Certification of Drinking Water System Operators and Water Quality Analysts regulation. The regulation provides the framework for the certification of drinking water operators, and the ministry’s Operator Certification Program.

The program establishes professional standards related to education, training, experience and examinations. Certification and training requirements help ensure that operators are aware of emerging technologies and have the required knowledge related to their field. These requirements set the minimum training hours they are required to complete for ongoing learning.

Becoming a drinking water operator and progressing to higher certificate classes

The first step to becoming a certified drinking water operator is to get the drinking water Operator-in-Training certificate. The certificate allows new operators to gain the required one year of experience in order to be eligible for a Class I operator certificate. To achieve a Class I certificate, operators-in-training must also pass an exam and complete the ministry’s Entry-level Course for Drinking Water Operators which is a comprehensive two-week training course developed by the ministry and delivered by the Walkerton Clean Water Centre in different locations throughout the province. The Entry-level Course covers topics such as protecting public health, regulations governing water quality, disinfection and treatment, water distribution and sampling. Ontario also has agreements with 16 colleges with environmental programs that have incorporated the curriculum of the Entry-level Course. This provides another pathway for students wishing to enter the field.

Class I operators may progress to higher class certificates, e.g. Class 2, Class 3 and Class 4, depending on the operational requirements of the subsystem where they work. The more complex a system is, the higher its classification which increases the amount of training that operators must take to renew their certificates. To upgrade to a higher-class certificate, operators must meet continuing education and training requirements, experience requirements and pass an exam.

Annual operator training requirements

Ongoing annual training helps ensure that operators maintain their knowledge and skills and keep up-to-date on advancements in the water sector throughout their careers. Once certified, operators are required to renew their certificates every three years.

To do this, they must take the ministry’s mandatory renewal course offered through the Walkerton Clean Water Centre which covers emerging issues, new regulatory requirements and the latest public health issues. Operators are required to complete between 20-50 hours of training annually depending on the complexity of the system they operate. The total number of training hours includes a combination of structured on-the-job training and continuing education approved by the ministry.

Continuing education training is developed and delivered by external training providers including private businesses, municipalities, First Nation organizations, Ontario colleges and government agencies like the Walkerton Clean Water Centre and the Ontario Clean Water Agency. As of June 2019, there were 1,047 approved courses delivered by 133 training providers.

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre

The Walkerton Clean Water Centre is an agency of the Government of Ontario and an important training and education partner. The Centre delivers the ministry’s mandatory operator certification courses and other drinking water training at its facility and different locations provincewide, including small and remote communities. As of March 31, 2019, there were 84,235 participants who had completed courses provided by the Centre.

Operator certification statistics

Operators may hold multiple certificates if they work in different types of systems. As of March 31, 2019, there were 7,272 certified drinking water operators in Ontario who held a total of 10,040 certificates. Since March 31, 2009, the number of operators has increased by 1,326. This works out to a 22% increase over the last 10 years. This means that today, owners of drinking water systems have a larger pool of trained operators to choose from to run their systems.

Compliance

Operators are expected to act honestly, competently and with integrity to maintain safe drinking water quality. The ministry takes action when operators do not adhere to such standards. In 2018-19, one operator had their certificate revoked because their application contained inaccurate information about their experience.

The Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page on the Open Data Catalogue provides more information on operator certification.

Partnership, transparency and public engagement

To deliver on the protection framework, the ministry works with partners to provide safe drinking water and engages in regular outreach by consulting on policies to protect drinking water and public reporting.

Since 2005, the ministry has met at least once a year with the Ontario Water Works Association, the Ontario Municipal Water Association, and as of 2018, the Water Environment Association of Ontario. These meetings are held to provide a regular forum for stakeholder engagement, provide policy/program updates, and gain feedback from the associations on policy/programs/procedures, and any emerging or potential issues.

In addition, the ministry frequently engages with municipal stakeholders through regular day-to-day business and works in partnership with Ontario’s drinking water sector to explore innovative drinking water solutions and to consult with experts in the field of safe drinking water. For example, the ministry is leading a working group which includes representatives from the Ontario Water Works Association and municipalities, that is advising on revisions to a ministry guidance document. This guidance document provides information on how to manage situations where surface water directly influences the quality of groundwater that supplies water wells. The outcome of this working group and resulting revisions to the guidance document are expected to significantly lower costs for municipalities.

The source protection program is also built on strong local partnerships. The ministry works with conservation authorities to implement the Clean Water Act by enabling them, along with local source protection committees that include municipal, business, environmental, and often First Nations representatives, to identify the risks to their drinking water sources and draft source protection plans to address them. The committees and authorities consult with the public and province at every stage of the process. With the minister-approved plans in place, the Clean Water Act framework continues to leverage the partnerships between conservation authorities, ministries, and municipalities, to gather information on how they are progressing with implementing plan policies and informing the public through annual reports from conservation authorities.

Public reporting is a key aspect of the protection framework because access to information enables Ontarians to see for themselves that Ontario’s drinking water meets standards. Each year, the ministry produces the Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report and the Minister’s Annual Report on Drinking Water. These reports can be found at ontario.ca/drinkingwater. Data, information and test results from drinking water systems and facilities are also made available on Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement data catalogue.

Supporting First Nations communities

Ontario is working collaboratively with First Nations and the federal government to support the resolution of long-term drinking water advisories and to support the long-term sustainability of each community’s water infrastructure.

The province sits on a Trilateral Steering Committee with representatives from Indigenous Services Canada, Chiefs of Ontario, Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation (Chair of the Committee) and representatives from Political Territorial Organizations and Tribal Councils. The Trilateral Steering Committee is implementing a plan to eliminate long-term drinking water advisories at public federally funded systems in First Nations communities by March 2021. As of October 2019, the trilateral action plan is tracking 43 long-term drinking water advisories in 23 First Nations communities.

The ministry, through the Indigenous Drinking Water Projects Office, is providing in-kind technical support to First Nations communities and organizations upon request, including:

- Technical assessments of existing drinking water systems to determine conformance with Ontario’s regulatory requirements

- Technical advice for various stages of projects, from feasibility studies through to design, construction and commissioning

- Water quality sampling to accelerate project milestones

- Support for the development of sustainable operations and maintenance business plans

- Advice on operator training and certification requirements

- Advice and support for source protection and watershed planning

- Support for education and outreach to youth to promote confidence and awareness in drinking water.

As an example of this work, the province has collaborated with Political Territorial Organizations, Tribal Councils and their member communities to assess existing water infrastructure against Ontario standards and support the development of long-term community water infrastructure plans. As of October 2019, a total of 63 water and 17 wastewater assessments have been completed in 59 communities.

In addition to the work of the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, the Ministry of Infrastructure, in partnership with Infrastructure Canada, administers the Clean Water and Wastewater Fund to municipalities and First Nations in Ontario. As of September 2019, 116 First Nations have projects approved under the Fund for a total of $13.5 million in joint federal-provincial funding, $4.5 million provincial and $9.0 million federal, representing funding support for 239 on-reserve projects.

Highlight: Provincial-First Nations partnerships supporting operator certification and training

Many First Nations communities in Ontario have decided to follow provincial training and certification requirements. Of the 7,272 certified drinking water operators in the province, 180 were employed as operators in First Nations systems, holding 262 drinking water operator certificates.

First Nations have identified the need for additional support for their First Nations operators. The province has implemented the following initiatives which are underway.

- Entry-level training for new operators: The Walkerton Clean Water Centre, in partnership with the Ontario First Nations Technical Services Corporation and the Keewaytinook Okimakanak/Northern Chiefs Council, developed the Entry-Level Course for Drinking Water Operators for First Nations, which is tailored to the needs of operators of First Nations systems. The Entry-Level Course is a required qualifying course for operator certification under provincial regulations but is optional for many First Nations operators as drinking water systems on reserves typically fall under federal jurisdiction. This two-week course includes a facilitated self-study first week with face-to-face instructor support, followed by a second week of classroom discussion and practical hands-on training provided by two instructors. As of October 2019, 106 individuals from First Nations communities across the province have successfully completed the course.

- Practical certification examinations: The ministry, in collaboration with the Aboriginal Water and Wastewater Association of Ontario, is offering on-site practical certification examinations for eligible and experienced operators of First Nations drinking water systems. These practical exams, held at the operator’s drinking water system and administered by experienced assessors, allow the operator to demonstrate their knowledge and obtain a provincial certificate.

Small Drinking Water Systems Program — Ministry of Health

Message from the Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ontario's Small Drinking Water Systems Program continues to demonstrate its value in protecting the health of Ontarians with the release of the 2018-2019 program results. With a steady decline in the number of high-risk systems and a downward trend in the number of adverse water quality incidents, the program has demonstrated improvement in the safety of our drinking water. As we reflect on the program’s accomplishments, it is important to recognize that we owe much of its success to the continued collaboration between Ontario’s boards of health, Public Health Ontario Laboratories, the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks, and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. These partners share a commitment to excellence that ensures that the people of Ontario and its visitors continue to benefit from a comprehensive safe drinking water program.

The program continues to uphold Justice O’Connor’s recommendations by adhering to rigorous drinking water quality standards established for the province while enabling reduced regulatory burden on small system operators. Comprehensive inspections and risk-based assessments provided by public health inspectors, employed by the local board of health, produce a customized site-specific plan for owner/operators of small drinking water systems to keep their drinking water safe for the public. These systems often service establishments where people gather, such as community centres and places of worship — places that foster a sense of community, which I strongly feel is essential to health and well-being.

I want to thank the local boards of health and all of our drinking water partners for their hard work and vigilance to ensure the provision of safe drinking water for Ontarians and their families.

David C. Williams, MD, MHSc, FRCPC

Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ministry of Health

2018-19 Highlights of Ontario’s small drinking water system results

Ontario has approximately 10,000 businesses and other community sites that use a small drinking water system to supply drinking water to the public. These systems, which are regulated under the Health Protection and Promotion Act and its regulation, O. Reg. 319/08 (Small Drinking Water Systems), are located across the province in semi-rural to remote communities and provide drinking water in restaurants, places of worship, community centres, resorts, rental cabins, motels, bed and breakfasts, campgrounds and other public settings, where there is not a municipal drinking water supply.

The Small Drinking Water Systems Program is a unique and innovative program overseen by the Ministry of Health and administered by local boards of health. Public health inspectors conduct inspections and risk assessments of all small drinking water systems in Ontario, and provide owner/operators with a tailored, site-specific plan to keep their drinking water safe. This customized approach has reduced unnecessary burden on small drinking water system owner/operators without compromising provincial drinking water standards.

Owners and operators of small drinking water systems are responsible for protecting the drinking water that they provide to the public. They are also responsible for meeting Ontario’s regulatory requirements, including regular drinking water sampling and testing, and maintaining up-to-date records.

2018-19 at a glance:

- Over the past seven years, we have seen progressively positive results including a steady decline in the proportion of high-risk systems (10.3% in 2018-19 down from 16.6% in 2012-13). Risk category is determined based on water source, treatment, and distribution criteria. High-risk small drinking water systems may have a significant level of risk and are routinely inspected every two years. Low and moderate risk small drinking water systems may have negligible to moderate risk and are routinely inspected every four years. Public health inspectors often work with the operator to address potential risks, which, when corrected, may result in a lower assigned category of risk. As of March 31, 2019, over three quarters (77.5%) of small drinking water systems are categorized as low risk.

- 97.8% of almost 100,000 drinking water samples submitted from small drinking water systems during the reporting year have consistently met Ontario drinking water quality standards. The results identified as not meeting the standards represent 2,206 test results, of which 2,019 were microbiological exceedances and 187 were chemical exceedances. Public health inspectors work with the system owners and operators to bring their systems into compliance.

- As of March 31, 2018, 21,965

footnote x risk assessments have been completed for the approximately 10,000 small drinking water systems. - Over 89.7% of systems are categorized as low and moderate risk and subject to regular re-assessment every four years; while the remaining systems, categorized as high risk, are re-assessed every two years.

- Adverse water quality incidents and the number of systems that reported an adverse water quality incident demonstrated a downward trend from 2017-18, with some fluctuations. A decline of 7.6% in total number of adverse water quality incidents was observed between 2017-18 (1,326) and 2018-19 (1,232); and the number of small drinking water systems that reported an adverse water quality incident for the same period also declined by 9.5% from 1,061 in 2017-18 to 969 in 2018-19.

footnote xi

Looking ahead

At the beginning of this report, we recapped how far the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks and its collaborative partners have come to advancing drinking water protection in this province.

Looking ahead, we will remain committed to ensuring that Ontario has among the best protected drinking water in the world. Working with local communities and water professionals across the province, we will continue to look for future opportunities to improve the drinking water protection framework — be it updating our drinking water legislation, regulations and standards to reflect new and emerging information, making our compliance programs more effective and less burdensome, or improving how we use our data to better understand where more protection is needed.

The success of our communities and our health rely on having access to safe drinking water. Ontarians can take pride in knowing that our strong monitoring, reporting and enforcement activities and programs have helped Ontario’s drinking water to remain protected.

Footnotes

- footnote[i] Back to paragraph In 2018-19, there were 458 registered non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, however, only 445 of these systems submitted samples for testing as some ceased to operate and/or data was not provided to the ministry.

- footnote[ii] Back to paragraph The number of systems serving designated facilities that were registered in 2018-19 was more than those that submitted samples for the following reasons: some systems ceased to operate and/or data was not provided to the ministry, while some received drinking water for their cistern from municipal residential drinking water systems which carried out the required sampling on their behalf. Some did not provide samples and posted notices advising people not to drink the water.

- footnote[iii] Back to paragraph Samples are taken after system is flushed.

- footnote[iv] Back to paragraph The 236 lead exceedances occurred at 27 municipal residential drinking water systems.

- footnote[v] Back to paragraph The 16 lead exceedances occurred at six non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems.

- footnote[vi] Back to paragraph In 2018-19, 661 municipal residential drinking water systems were registered with the ministry and 659 systems were inspected. The two lists differ for the following reasons. The Burgoyne Drinking Water System switched categories from non-municipal year-round residential to municipal residential during the year. Prior to that, this system had submitted drinking water samples for testing and was inspected as a non-municipal year-round residential drinking water system. Because it was inspected as a non-municipal year-round residential drinking water system, its inspection rating as a municipal system is not available. The Richmond West Drinking Water System became operational at the end of February 2019. It was not inspected because it can take longer than a single month to fully assess and document a municipal drinking water system inspection. Ministry policy provides that systems that commence operation after Dec. 31 of any given fiscal year will be fully inspected in the following fiscal period to ensure a full and robust examination of all the facets of the drinking water system are appropriately addressed. Therefore, the Richmond West system does not have an inspection rating.

- footnote[vii] Back to paragraph A case may involve one or more charges. The convictions data reflect the year in which the conviction took place and not the year in which the drinking water system committed the offence that led to the conviction.

- footnote[viii] Back to paragraph Includes convictions against corporations and individuals.

- footnote[ix] Back to paragraph One of the cases involved charges against a subcontractor.

- footnote[x] Back to paragraph The reported number of risk assessments will change as new systems come into use/change in use, and routine re-inspections and risk assessments are completed. Risk categories may also fluctuate (e.g. if recommended improvements are taken to reduce the system’s risk). Similarly, a system may require reassessment to determine if the risk level has changed (e.g. if the water source or system integrity is affected by adverse weather events or system modifications).

- footnote[xi] Back to paragraph An adverse test result does not necessarily mean that users are at risk of becoming ill. When an adverse water quality incident is detected, the small drinking water system owner/operator is required to notify the local medical officer of health and to follow up with any action that may be required. The public health unit will perform a risk analysis and determine if the water poses a risk to health if consumed or used and take additional action as required to inform and protect the public. Response to an adverse water quality incident may include issuing a drinking water advisory that will notify potential users whether the water is safe to use and drink or if it requires boiling to render it safe for use. The public health unit may also provide the owners and/or operators of a drinking water system with necessary corrective action(s) to be taken on the affected drinking water system to address the risk.