Chief Drinking Water Inspector Annual Report 2015-2016

The Chief Drinking Water Inspector Annual Report provides information on the performance of Ontario’s regulated drinking water systems and laboratories, drinking water test results, and enforcement activities and programs.

Message from the Chief Drinking Water Inspector

I am pleased to present the 2015-2016 annual drinking water report for Ontario and want to acknowledge the contributions of our many partners who work with us to safeguard drinking water in Ontario.

Ontario uses a multi-barrier approach of strong legislation, stringent health-based standards, regular and reliable testing, highly trained operators, regular inspections and a source water protection program to protect the province’s drinking water.

2015-2016 at a glance:

- 99.8% of 527,172 drinking water test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards

- the number of municipal residential drinking water systems that received a 100% inspection rating increased seven percentage points from 67% in 2014-2015 to 74% this year

This year’s report is structured by drinking water system type with new sections on key trends and topical issues. In addition, a number of charts and tables previously in this report can now be found by visiting the Drinking Water Quality page on the province’s Open Data Catalogue.

Dr. David C. Williams, the Chief Medical Officer of Health for Ontario, also provides an update on the performance of the province’s small drinking water systems.

Susan Lo

Chief Drinking Water Inspector

Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change

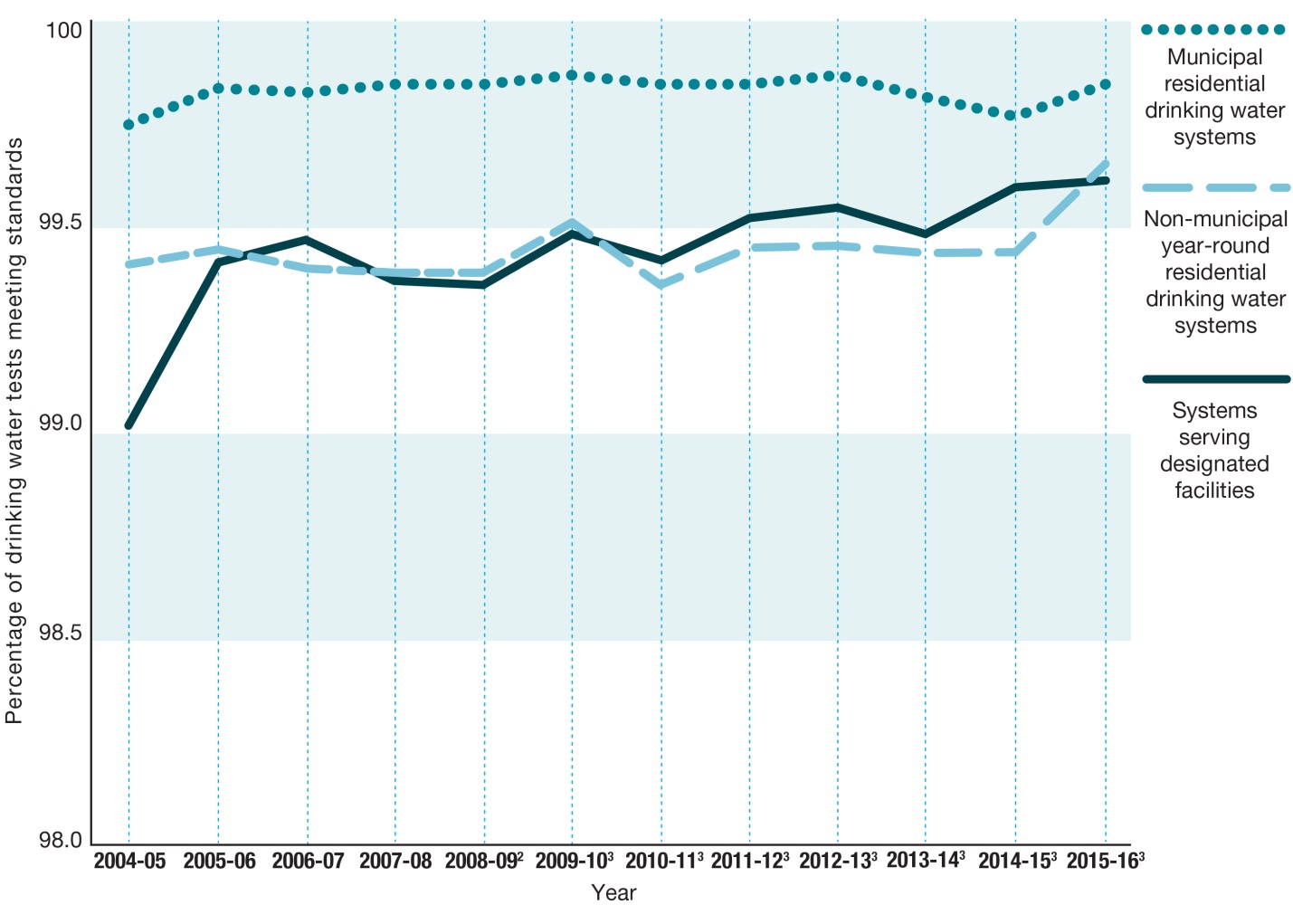

Trends

As illustrated in Figure 1, over the past 12 years, the percentage of drinking water test results meeting microbiological, chemical and radiological standards has remained consistently high.

2015-2016 at a glance:

- 99.8% of 527,172 drinking water test results from municipal residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s strict drinking water quality standards

- the number of municipal residential drinking water systems that received a 100% inspection rating increased seven percentage points from 67% in 2014-2015 to 74% this year

Figure 1: Trends in percentage of drinking water tests meeting Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards, by type of facility1

Notes for Figure 1:

1 There were slight variations in the methods used to tabulate the percentages year-over-year due to regulatory changes and different counting methods.

2 Lead results were not included as they were reported separately.

3 Lead distribution results were included and lead plumbing results were reported separately. The total trihalomethanes running annual average calculation changed part way through fiscal year 2015-16.

In addition, the past decade has seen advancements in technology that have positively impacted not only the quality of Ontario’s drinking water but the methods to measure that quality. Ultraviolet drinking water technology is being used by a growing number of municipal residential drinking water systems for the disinfection of drinking water. Advancements have been made in ozonation for disinfection, taste and odour control as well as improvements in laboratory detection limits for drinking water parameters.

The way some municipalities generate operational data (e.g. chlorine, turbidity, flow) for their drinking water systems has also changed. The ministry is reviewing how it can incorporate these technological advances into the inspection and compliance framework.

Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Ontario has a comprehensive safety net that protects drinking water from source to tap. There are eight elements to the safety net which provide a multi-barrier approach to drinking water protection. These include strong legislation, stringent health-based standards, regular and reliable testing, highly trained operators, regular inspections, and a source water protection program.

Figure 2: Ontario’s drinking water safety net

Topical issues

Climate change has caused an increase in the frequency of algal blooms. Some varieties of algae produce microcystin-LR, a toxin harmful to humans and pets. The Ontario Drinking Water Quality standard for microcystin-LR is 1.5 micrograms per litre. In Ontario, municipal drinking water systems have implemented strategies combining monitoring, sampling, and implementing appropriate treatment to remove algal toxins from the drinking water. These operational strategies have been successful as microcystin-LR has not been detected in treated water. Also, in 2014, Ontario developed a 12 Point Action Plan to prevent and respond to blue-green algal blooms and their impacts.

Ontario’s source water protection plan

Ontario protects its drinking water at many points along the away from its sources to the tap.

Protecting water starts with the natural sources that supply drinking water systems. Local source protection committees in 19 source protection areas or regions developed plans to identify and address existing and potential risks to municipal drinking water in their communities — the result of many years of work and public consultation. All 22 of the source protection plans that were developed have been approved and are in effect.

Drinking water quality standards

Drinking water must meet Ontario’s strict health-based standards for microbiological organisms and chemical substances which are prescribed under the Safe Drinking Water Act.

The ministry regularly reviews and updates drinking water quality standards. In November 2015, it announced the strengthening of the standards for four substances (i.e. arsenic, carbon tetrachloride, benzene and vinyl chloride), introduced new standards for four more substances (i.e. chlorate, chlorite, 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid and haloacetic acids) and clarified testing and sampling requirements for two other substances (i.e. trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids). The changes are being phased in to allow time for implementation.

The following sections show how our regulated drinking water systems are meeting these standards. The sections also provide information on drinking water advisories, adverse water quality incidents, inspection results and orders and convictions. Data associated with these sections can be found by visiting the Drinking Water Quality page on our Open Data Catalogue.

Municipal residential drinking water systems

In 2015-16, 99.84% of 527,172 drinking water tests from 658

For details on municipal systems, please see the Drinking Water Quality page on our Open Data Catalogue.

The majority of test results for lead in plumbing continued to meet the provincial standard with the percentage steadily increasing each year from 92.69% in 2013-14 to 95.59% in 2015-16.

In 2015-16, there were 207 exceedances for lead in plumbing out of 4,697 test results from municipal residential drinking water systems.

When lead levels exceed the criteria outlined in the Drinking Water Systems Regulation (O. Reg. 170/03), owners/operating authorities are required to develop a control strategy to reduce lead levels. As of 2010-11, 20 municipalities were required to prepare strategies to address lead issues. Since that time, no additional municipal residential drinking water systems were identified to prepare lead control strategies. These municipalities are at various stages of completing their work on lead.

Six municipalities have implemented their lead control strategies:

- five municipalities have completed implementing their corrosion control plans

- one municipality replaced its lead service lines

Fourteen municipalities continue to make significant progress in addressing their lead issues:

- two municipalities have completed implementing their corrosion control plans and are replacing lead service lines

- three municipalities are in the process of implementing their corrosion control plans

- two municipalities are in the process of implementing their corrosion control plans and replacing lead service lines

- seven municipalities are replacing lead service lines

Data associated with these lead control strategies can be found by visiting the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page on our Open Data Catalogue.

If a drinking water test result does not meet Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards, an adverse water quality incident has occurred. An operational problem at a system can also result in an adverse water quality incident. An adverse water quality incident does not necessarily mean the drinking water is unsafe; it indicates that an incident has occurred and that corrective action must be taken. Corrective actions may include the issuance of a drinking water advisory by the local health unit if there is concern that the water may not be safe for the public to drink.

In 2015-16, 373 systems reported 1,554 adverse water quality incidents. In 2014-15, 372 systems reported 1,954 incidents. As expected, the number of adverse water quality incidents changed again in 2015-16 to previous 2013-14 levels. The 2014-15 numbers were related to the increased sampling frequency for a specific watermain replacement project.

Drinking water advisories that last for 12 consecutive months are considered to be long-term. In 2015-16, the Lynden Drinking Water System near Hamilton continued to have a long-term drinking water advisory (in place since 2012-13). The advisory was issued to prevent potential long-term exposure to elevated concentrations of lead. The test results are below the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standard but the advisory will remain in place to allow the concentrations in the drinking water supply to stabilize. Mitigation efforts such as identifying the source of lead, continuing to offer residents on-tap filters that are certified to remove lead, and searching for an alternative water source are being made by the municipality.

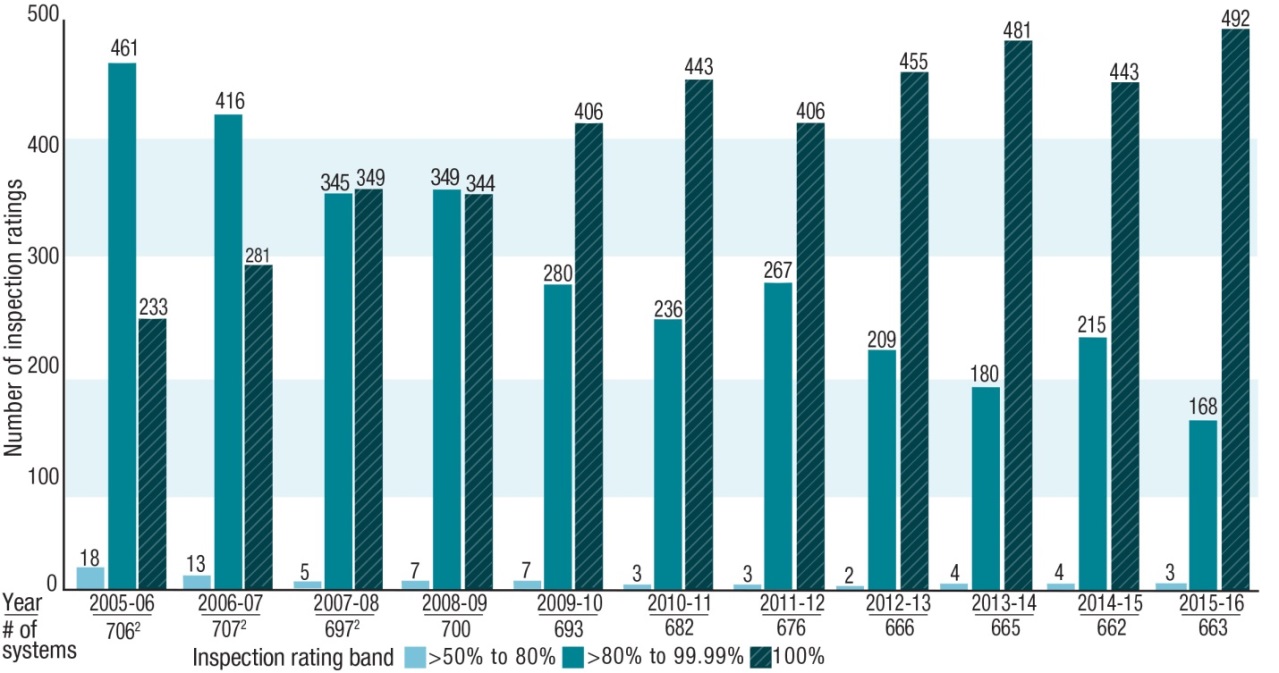

The province inspects municipal residential drinking water systems annually to determine whether they are meeting Ontario’s regulatory requirements. During 2015-16, staff inspected all 663 systems.

Figure 3: Yearly comparison of municipal residential drinking water system inspection ratings1

Notes for Figure 3:

1 The decline in the total number of systems is due to amalgamations of these systems.

2 Between 2005-06 and 2007-08, the ministry completed its planned annual inspection program of all municipal residential drinking water systems in Ontario generating its annual inspection rating for each system. During this period, for a number of reasons some systems were inspected twice, e.g., a water treatment plant and distribution system were registered as two systems but were inspected together as one system and vice versa or to ensure equipment had been properly decommissioned.

Orders can be issued as a result of inspections or incidents occurring outside of the inspection period. In 2015-16, no orders were issued to municipal residential drinking water systems.

Non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems

In 2015-16, 99.67% of 42,760 drinking water test results from 442 non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems met Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards.

These systems include privately owned systems that supply drinking water to residences with six or more units including apartments buildings and mobile home parks.

Lead test results in plumbing from these systems indicate that the vast majority of results continued to meet the provincial standard in drinking water in 2015-16. The percentage of lead test results meeting standards has remained close to 99% since 2013-14.

In 2015-16, there were 18 exceedances for lead in plumbing out of 1,369 test results from non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems.

Adverse water quality incidents for non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems may occur but do not necessarily mean that the drinking water is unsafe. They also have to be addressed with corrective action.

In 2015-16:

- 162 systems reported 385 adverse water quality incidents. This is less than the 427 adverse water quality incidents reported by 181 systems in 2014-15

- the ministry inspected 95 of the 458

footnote 4 registered drinking water systems - 12 contravention and one preventative measures orders were issued to 13 systems

Local services boards

These boards operate drinking water systems in northern communities without municipal government structures.

In 2015-16, all eight systems were inspected and one preventative measures order was issued.

Systems serving designated facilities

In 2015-16, 99.61% of 64,965 drinking water test results from 1,333 systems serving designated facilities met Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards.

These systems are not connected to municipal residential drinking water systems and provide drinking water to designated facilities such as children’s camps, schools, day nurseries

In 2015-16:

- 280 systems reported 427 adverse water quality incidents which is down from 288 systems reporting 450 in 2014-15

- 218 of 1,460

footnote 6 registered systems were inspected and two contravention orders were issued to two systems

Schools and day nurseries

Whether connected to a municipal drinking water system or not, registered schools and day nurseries are subject to the flushing and sampling requirement of the Schools, Private Schools and Day Nurseries Regulation (O. Reg. 243/07) to help reduce the risk of children six and under being exposed to lead in drinking water. The province uses a variety of methods to ensure compliance including inspections, compliance audits and an online reporting program.

Under O. Reg. 243/07, these facilities are required to regularly flush their plumbing. Flushing reduces potential lead levels in drinking water because it prevents water from standing in the plumbing, thereby reducing contact time with the pipes and plumbing. These facilities are required to sample their drinking water before and after they flush their plumbing. Lead test results from these facilities continue to show that flushing significantly reduces lead in drinking water.

Past efforts to minimize exposure to lead in drinking water which include testing, education and outreach and in 2012-13, an extensive reporting initiative, demonstrate that the majority of facilities across Ontario do not have an issue with lead in drinking water.

In 2015-16:

- 6,900 Ontario facilities submitted flushed drinking water samples to licensed and eligible laboratories for testing for lead and the results were reported to the ministry. Over 98% of these facilities met the standard for lead

- the less than two per cent of these facilities that did not meet the lead standard are required to take immediate corrective actions as directed by the local Medical Officer of Health

- the ministry conducted 166 inspections and 113 compliance audits of the 11,171 registered facilities. No orders were issued

236 facilities participated in the reporting program (after 2012-13, reports were sent to newly registered schools and day nurseries and those that did not complete the previous year’s report) and of those, 214 facilities indicated that flushing was performed according to the prescribed procedure.

Licensed and eligible laboratories

Laboratories that test drinking water must be licensed by the province when they are located within Ontario. In addition, there are a few laboratories that are located outside of Ontario that can test Ontario’s drinking water. These laboratories must meet specific ministry requirements and must be added to the ministry’s eligibility list. The out-of-province laboratories that are currently on the eligibility list are affiliated with licensed laboratories within Ontario. These eligible laboratories are able to conduct specialized testing that the Ontario licensed laboratories are not able to perform.

Ontario inspects all laboratories at least twice a year to determine whether they are meeting the regulatory requirements.

In 2015-16, all 52 laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water were inspected twice. Fifty-eight per cent of the inspections resulted in ratings of 100 per cent. The ratings of all inspections were greater than 90 per cent. This is a five percentage point increase from 2014-15 when all inspections received ratings that were higher than 85 per cent.

Two contravention orders were issued to one licensed laboratory. Both orders resulted from non-compliance issues found during routine inspections.

Compliance and Enforcement Regulation requirements

The Compliance and Enforcement Regulation (O. Reg. 242/05) of the Safe Drinking Water Act requires the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change to carry out a number of specific activities such as taking mandatory actions and conducting inspections of municipal residential drinking water systems and laboratories that test Ontario’s drinking water.

Under O. Reg. 242/05, the ministry is required to ensure all municipal residential drinking water systems are inspected annually and that one out of every three inspections is unannounced. In addition, the ministry must inspect all licensed and eligible laboratories at least twice a year ensuring that at least one inspection is unannounced.

In 2015-16 the ministry met all its obligations required under the Compliance and Enforcement Regulation.

Convictions

The government takes action in response to potential violations, as those who are responsible for delivering safe drinking water to the public are legally accountable for their actions.

In 2015-16, two systems serving designated facilities were convicted. There were two cases with convictions involving two systems resulting in fines of $6,000 in total. Conviction data reflects the year in which the conviction took place, not the year when the offence was committed. Data associated with this section can be found by visiting the Drinking Water Quality and Enforcement page on our Open Data Catalogue.

Operator certification and training

Drinking water operators in Ontario must be trained according to the type and class of facility they operate. The more complex a system is (the higher the class of system), the more training an operator must complete. As of March 31, 2016, 6,480 drinking water operators held 9,074 certificates.

One of the ministry’s key training partners is the Walkerton Clean Water Centre. As of March 31, 2016, the centre has trained more than 62,500 new and existing professionals since it opened in 2004. For more information, see the Walkerton Clean Water Centre’s website.

Small Drinking Water Systems Program – Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

Message from the Chief Medical Officer of Health

As Ontario’s Chief Medical Officer of Health, I am pleased to share with you some highlights of Ontario’s 2015-16 drinking water quality results for Small Drinking Water Systems.

Ontario’s drinking water continues to meet our rigorous health-based standards, and the performance of our small drinking water systems is no exception. These achievements emanate from the collective, steadfast work of our many drinking water partners: keen oversight by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; collaboration and technical expertise through the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change; and comprehensive on-the-ground administration of the Small Drinking Water System Program by Ontario’s public health units.

A steady decline in the number of adverse water quality incidents, for these small but important systems, may be attributed to the identification of and corrective action taken to reduce adverse incidents. These results could not be possible without the detailed inspections and risk-based assessments provided by public health inspectors, which produce a customized site-specific plan for owner/operators of small drinking water systems to keep their drinking water safe.

The Small Drinking Water Systems Program demonstrates the Ontario government’s commitment to reduced regulatory burden, increased accountability and public transparency. Together we are upholding Justice O’Connor’s recommendations to ensure that drinking water quality standards established for the province are not compromised, and meeting these standards in a way that supports the needs of small system operators.

I want to take this opportunity to personally thank the local boards of health and our many partners for their leadership in the protection of public health and vigilance in safeguarding drinking water in Ontario.

David C. Williams, MD, MHSc, FRCPC

Chief Medical Officer of Health

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

2015-16 Highlights of Ontario’s Small Drinking Water System Results

Across Ontario, thousands of businesses and other community sites use a small drinking water system to supply drinking water to the public. These communities may not have access to a municipal drinking water supply and are most often located in semi-rural and remote communities.

Many of these systems provide drinking water in restaurants, places of worship and community centres, resorts, rental cabins, motels, lodges, and bed and breakfasts, and campgrounds, among other public settings.

Owners and operators of small drinking water systems are responsible for protecting the drinking water that they provide to the public. They are also responsible for meeting Ontario’s regulatory requirements, including regular drinking water sampling and testing, and maintaining up-to-date records.

Through the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Small Drinking Water Systems Program, regulated under the Health Protection and Promotion Act and its regulations, local boards of health (public health units) help operators keep their water safe by applying a risk-based approach resulting in a customized directive for each system which may include requirements for water sampling, water treatment options, operational checks and operator training.

As of March 31, 2016, 16,804

In 2015-16, we continued to see gradual improvement in overall water sample quality with close to 98 per cent of samples submitted met Ontario’s Drinking Water Quality Standards.

In addition, we saw significant decreases in adverse tests and adverse water quality incidents from the previous year, while the number of samples submitted remained stable:

- 8.78% fewer adverse test results

- 15.97% fewer adverse water quality incidents

footnote 8

An adverse test result does not necessarily mean that users are at risk of becoming ill. In the event of an adverse test result, the laboratory notifies both the owner and/or operator of the small drinking water system and the local public health unit for immediate response.

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Ontario’s drinking water quality standards are listed in the Ontario Drinking Water Quality Standards Regulation (O. Reg. 169/03). The number of parameters has been updated from 158 (as reported in the 2014-2015 Chief Drinking Water Inspector’s Annual Report) to 145 due to the January 1, 2016 revision of O. Reg. 169/03. This update revised standards for 13 pesticides that are no longer in commercial use, have been de-listed from the federal guidelines, and have not been detected in drinking water samples for at least 10 years. The parameters that drinking water systems must test for are given in the Drinking Water Systems Regulation (O. Reg. 170/03). In 2016-17, these parameters will increase with the addition of new substances.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph There were 661 registered municipal residential drinking water systems in 2015-16 and of these 658 submitted samples. Three systems that received their water from another municipal residential drinking water system had their samples represented within the samples collected and submitted by the municipal residential drinking water systems that supplied water to them.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph In 2015-16, there were 661 registered municipal residential drinking water systems, however, 663 systems were inspected. Towards the end of the previous fiscal year (i.e. 2014-15) two municipal residential drinking water systems ceased to operate: Carriage Lane Drinking Water System and Harbour Lights Drinking Water System. The Province inspected both systems in 2015-16 to ensure that the operations were properly shut down.

- footnote[4] Back to paragraph In 2015-16, there were 458 registered non-municipal year-round residential drinking water systems, however, only 442 of these systems submitted samples for testing as some ceased to operate and/or data was not provided to the ministry.

- footnote[5] Back to paragraph The Child Care and Early Years Act replaces the term “day nursery” with “child care centre” after August 31, 2015.

- footnote[6] Back to paragraph The number of systems serving designated facilities that were registered in 2015-16 was more than those that submitted samples for the following reasons: some systems ceased to operate and/or data was not provided to the ministry, while some received drinking water for their cistern from municipal residential drinking water systems which carried out the required sampling on their behalf. Sampling was not required for those systems that posted notices advising people not to drink the water.

- footnote[7] Back to paragraph The reported number of risk assessments will change as new systems come into use/change in use, and routine re-inspections and risk assessments are completed. Risk categories may also fluctuate (e.g., if recommended improvements are taken to reduce the system’s risk). Similarly, a system may require reassessment to determine if the risk level has changed (e.g., if the water source or system integrity is affected by adverse weather events or system modifications).

- footnote[8] Back to paragraph When an AWQI is detected, the small drinking water system owner/operator is required to notify the local medical officer of health and to follow up with any action that may be required. The public health unit will perform a risk analysis and determine if the water poses a risk to health if consumed or used and take additional action as required to inform and protect the public. Response to an AWQI may include issuing a drinking water advisory that will notify potential users whether the water is safe to use and drink or if it requires boiling to render it safe for use. The public health unit may also provide the owners and/or operators of a drinking water system with necessary corrective action(s) to be taken on the affected drinking water system to address the risk.