Drainage legislation and common law in Ontario

Learn about drainage legislation and common law as it relates to different types of drains in rural areas. This technical information is for Ontario producers and rural landowners.

ISSN 1198-712X, Published December 2024

Introduction

Drainage is essential in Ontario due to the variable climate and the excess precipitation at certain times of the year. The precipitation patterns, freezing cycles and severe weather make proper drainage critical for agriculture, roads, residential, commercial and industrial properties in both rural and urban settings.

Drainage infrastructure consists of a combination of private and communal drainage systems that provide an outlet to natural watercourses. Ensuring proper drainage is a complex task that balances drainage needs, environmental and societal interests, and regulatory and legal requirements.

Common law, also known as case law, is a set of rules, principles and customs established by the courts based on specific past cases. It originated in England and is applied across Canada including Ontario, with the exception of Quebec. It is the foundation, unless modified (or built upon) by statute law, which is enacted by the legislature. Examples of statute law include the Drainage Act, 1990 Conservation Authorities Act, 1990 and the Fisheries Act, 1985.

Statute law

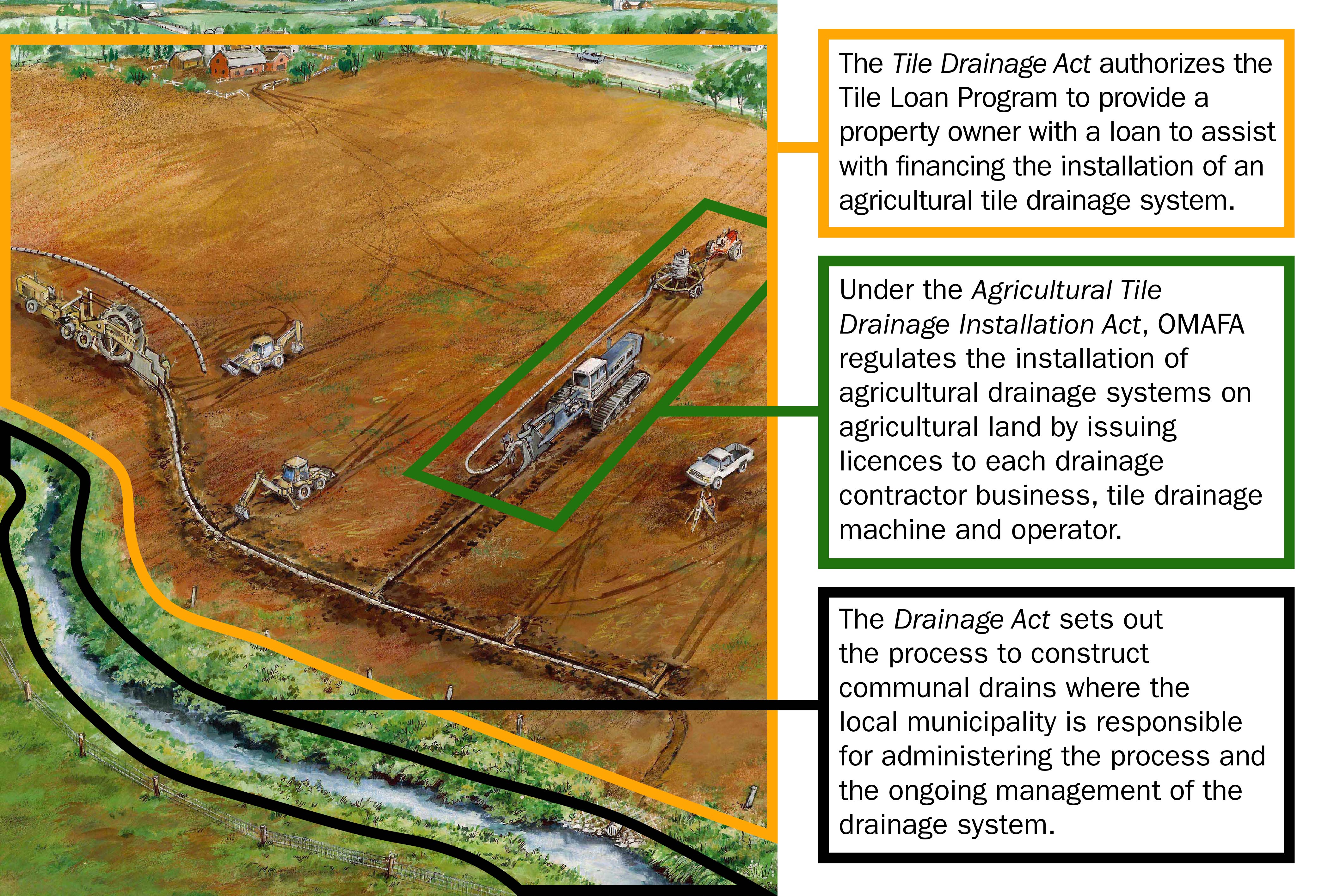

The Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness (OMAFA) administers 3 acts regarding drainage (Figure 1):

Accessible description for Figure 1

Agricultural Tile Drainage Installation Act

The Agricultural Tile Drainage Installation Act, 1990 (ATDIA), and the associated O. Reg. 18 regulate all businesses, machines and machine operators involved in the installation of an agricultural drainage system in Ontario.

Anyone who installs tile drainage on someone else’s agricultural land, using a tile drainage machine, must be licensed under the ATDIA. Usually, the Act does not apply to contractors working under the Drainage Act, 1990, nor to individuals installing drains on their own property.

Refer to Agricultural Tile Drain Installation Licensing Program for information on licensing.

Tile Drainage Act

The Tile Drainage Act, 1990, establishes regulations and procedures for municipalities and the province to provide financing for the installation of agricultural tile drainage in Ontario through a loan program. The Act provides the ability for loans to be provided in partnership with local municipalities, where they exist, or directly from the province in areas without municipal organization.

Refer to the OMAFA fact sheet, Tile Loan Program, for information on the program.

Drainage Act

The Drainage Act, 1990, provides a legal framework for the planning, construction and maintenance of communal drainage systems. This Act outlines the process that a municipality may, with a valid petition from landowners in the “area requiring drainage,” provide a legal outlet for surface and subsurface waters not attainable under common law.

Private drainage systems (such as tile drainage systems, agricultural ditches, roadside drainage ditches) must be discharged into a legal and sufficient outlet. To reach a sufficient outlet, a private drainage system may have to cross at least 1 other property. Property owners in Ontario have 2 options to get access to a legal and sufficient outlet located on another property under the Drainage Act, 1990, including:

- construct a mutual agreement drain (Section 2)

- petition the local municipality for a drain (also known as a municipal drain) (Section 4)

Mutual agreement drains

Mutual agreement drains are private drainage systems that are authorized, constructed, improved, financed (owned) and maintained through an agreement between two or more property owners under Section 2 of the Drainage Act, 1990. They are usually based on a written agreement that may or may not be registered on property title.

Two or more property owners may enter into a written agreement to construct or improve a drain on their land. The agreement should describe the land affected, the location of the drainage system and the proportion of the work each person is expected to pay for and maintain in the future. When the agreement is drawn up, it can be registered against the land for the protection of all owners.

The Drainage Act, 1990, gives mutual agreement drains formal status, and, if registered against the land, makes the agreement binding on future owners.

Mutual agreement drains are different from municipal drains, which are constructed, owned and maintained by the local municipality. Any enforcement of the agreement must be made through court action.

Refer to the OMAFA fact sheet, Mutual agreement drains for additional information.

Petition drains (also known as municipal drains)

The Drainage Act, 1990, defines a process that property owners (and others) can use to manage water on their lands so that legal responsibility is shared and the potential for damage is limited. This process is initiated when a petition for drainage works is signed and filed with the clerk of the municipality.

The authority for the petition is identified in Section 4(1). For petitions to be valid when initiated by property owners, the petition must be signed by at least one of the following:

- the majority (50% or more) in number of property owners (including roads) in the area requiring drainage, or

- the property owner(s) representing at least 60% of the area of land requiring drainage

- the road authority, where a road requires drainage

The petition is a legal document and the signature(s) on the petition must legally represent the properties listed on the petition. The submission of the petition initiates a process that must be followed by the municipality.

Drainage Act forms are found in the Central Forms Repository.

Petition for Drainage Works by Owners – Form 1

Petition for Drainage Works by Road Authority – Form 2

For additional details on the petition drain process, refer to Part A, Section 2.3 Construction of New Drainage Works by Petition in OMAFA’s Publication 859: A Guide for Drainage Superintendents Working under the Drainage Act in Ontario.

Awards drains

Award drains (Section 3) were created under the Ditches and Water Courses Act and were named because the construction work was “awarded” to persons along the drain. Award drains were constructed for nearly a century under this Act before it was repealed on June 1, 1963.

There are still a number of award drains in Ontario, and they must be maintained in accordance with the award of the engineer until the ditch is made into a petition drain under Section 4 of the Drainage Act.

Find more information on Award drains.

Agricultural Drainage Infrastructure Program

Sections 85 to 90 of the Drainage Act, 1990, allow the Minister of Agriculture, Food and Agribusiness to provide grants for various activities conducted under the Act. These grants are paid towards the assessments on agricultural land for the cost of municipal drain construction, improvement, maintenance, repair and operations to encourage the development of agricultural land in an environmentally responsible manner.

The grant program for activities under the Drainage Act is called the Agricultural Drainage Infrastructure Program (ADIP). OMAFA has developed the ADIP administrative polices to supplement the requirements already specified in the Act and to ensure public funds are used effectively.

Common law

It has been said that good drainage makes for good neighbours. Unfortunately, drainage of water is one of the most common areas of dispute between neighbours. Drainage disputes generally fall into the realm of common law, which always applies unless it is specifically altered by statute law. Common law disputes are disagreements between property owners over legal rights or responsibilities. If disputes cannot be mutually resolved between the property owners, final solutions can be determined by the courts.

Previous court decisions related to drainage are found at the Canadian Legal Information Institute. These drainage cases establish precedents and can assist with understanding the legal rights and responsibilities under common law and help when negotiating resolution of drainage issues between property owners.

Property owners are equal under common law, whether they are private citizens, companies, road authorities, municipalities, provincial or federal governments. If you get advice on common law drainage problems from a drainage contractor, a drainage engineer, a lawyer, a conservation authority or a government agency, remember, it is not their responsibility to solve the problem. No agency is assigned responsibility to resolve drainage issues. Only the courts can make the final decision in the dispute. To obtain a ruling by a court, a civil action must be initiated by the damaged party.

Even though the courts have the ultimate decision on drainage disputes, neighbours should try to reach some common ground and solve the problem in a cooperative way without going to court. Court rulings in common law may not make either side happy. It is the intent of this factsheet to help rural neighbours come to their own solutions and to avoid taking legal action against each other.

Previous common law court decisions have established precedents in drainage disputes, and from these precedents, a set of rules or principles have been developed that apply to water rights. These rules under common law can change as customs change and as new precedents are set. Also, the rules differ significantly between natural watercourses and surface water.

Natural watercourses

A natural watercourse is founded on the maxim principle of the common law; water flows naturally and should be permitted to do so.

A natural watercourse is generally defined as a stream of water that flows along a defined channel, with bed and banks, for a sufficient time to give it substantial existence. The flow of water does not need to be constant, but the channel definition, or characteristics, must be a permanent feature on the landscape. The watercourse may also spread over a level area without defined banks for a distance, before flowing again in a defined channel. This may also include streams that dry up periodically.

Farmers, and others, often have their own ideas about what is or isn’t a natural watercourse. Obvious examples of natural watercourses in Ontario include the:

- St. Lawrence River

- Niagara River

- Grand River

Many creeks and streams are considered to be natural watercourses. However, private ditches and channels across low areas on one’s own property are not usually considered to be natural watercourses (Figure 2). Regardless of anyone else’s opinion, it is up to the courts to determine whether a channel is a natural watercourse or surface water. Everyone else can only offer an opinion.

Riparian owners who are owners of property bordering a natural watercourse have several rights and responsibilities under common law, including:

- the right of drainage

- the right to use water for domestic or natural purposes

- the responsibility or liability for any impacts if they modify/interfere/dam a natural watercourse

- the responsibility to accept the water, even if flooding occurs

Surface water

Surface water has no defined course (Figure 3). It is “the water that falls as precipitation, but which finds its way to a natural watercourse by percolation or flow.” Surface water includes both collected and uncollected water. Common law can be confusing when it comes to surface water because, under most circumstances, it has no right of drainage, and the law appears to deny the right of water to flow downhill.

Under common law, surface water:

- has no right of drainage

- is not typically grounds for a lawsuit if it is uncollected and allowed to flow naturally; it does not have to be accepted by a lower property owner; they can protect their property (for example, with berms or dykes)

- must not be collected and diverted to land that would not naturally receive it

- if collected/discharged, can form the basis for a lawsuit, and the courts can order damages to be paid

Right of drainage

Collected surface water has no right of drainage and a property owner can be held liable for damages for directing collected surface water onto a neighbouring property. However, if a landowner collects and directs surface water on lower land continuously, openly, peacefully, without being contested and without permission for 20 years, the higher property owner may have acquired a right to drain the water onto the lower property (referred to as a prescriptive right). The prescriptive right continues despite any changes in the ownership of any of the properties. The time period to establish the right has been specified by the Real Property Limitations Act, 1990. While a person can claim a right of drainage, that right does not exist until legal action is taken and the courts have ruled the prescriptive right of drainage exists.

Once a property owner obtains a prescriptive right, they cannot alter the drainage conditions by increasing the amount of water flowing through to the neighbouring property or increase the boundaries of the area being drained. If the conditions are altered, the right of drainage may be lost.

For example, a road crossing has drained onto the adjoining property for over 20 years and a right of drainage could be claimed. Recently, 2 new lanes were added to the road and now an increased quantity of water flows through the culvert onto the adjoining land. If the road had a prescriptive right from a court decision, the right of drainage may now have been lost due to the modifications to the road that resulted in an increase to the amount of water.

Drainage issues under common law

There are many possible drainage issues that fall under common law. The following are a few of the most common issues and some discussion on options to resolve them. For additional scenarios refer to Part A, Section 1.2.4, Private “Common Law” in Publication 859: A Guide for Drainage Superintendents Working under the Drainage Act in Ontario.

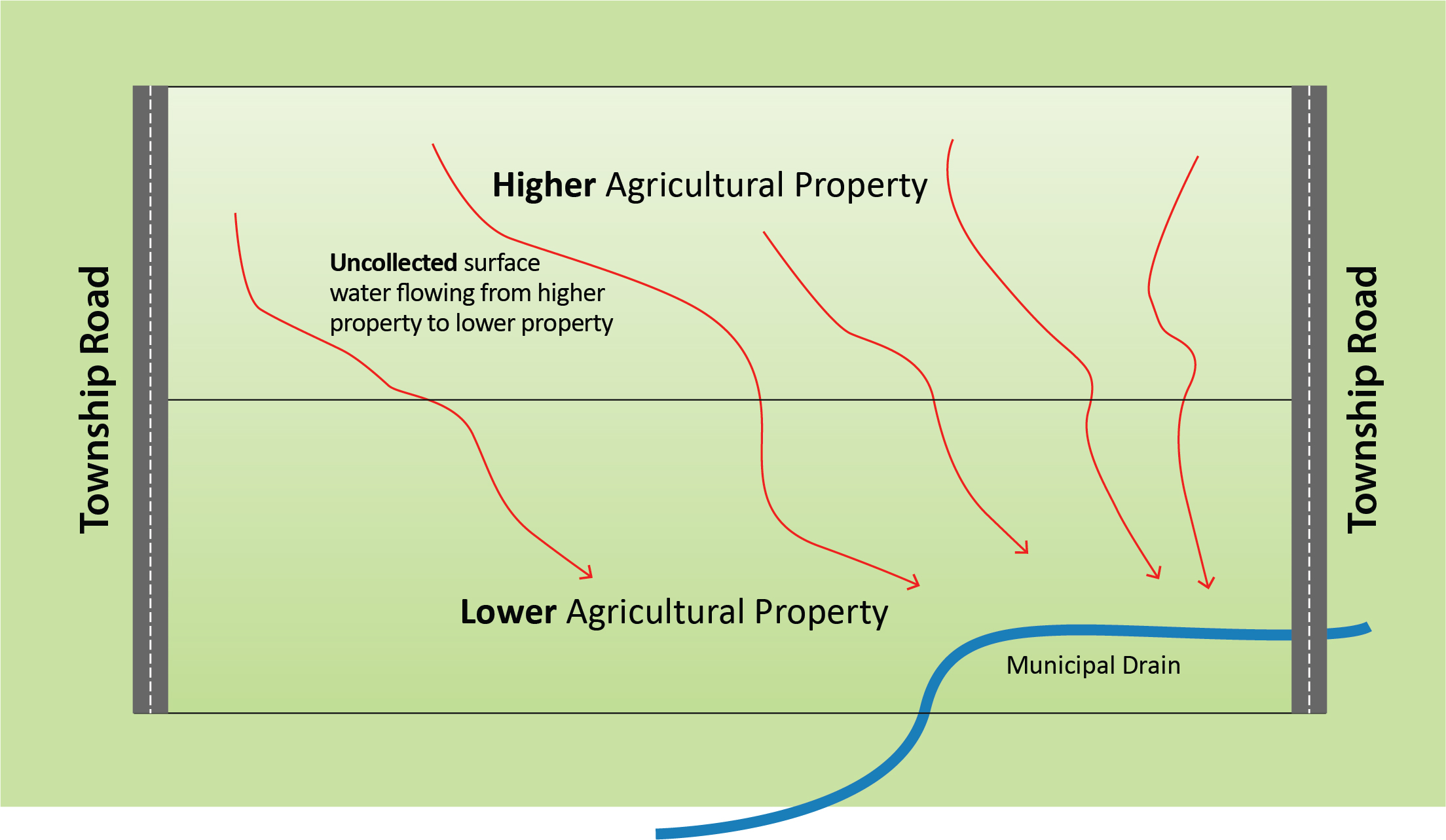

Lower property owner receiving uncollected water from a higher property owner

If the water, as shown in Figure 4, is surface water, then it has no right of drainage. The higher property owner can either choose to keep their water on their property or allow it to pass along onto property at a lower elevation. Similarly, the property owner at a lower elevation can either accept the water from higher property or reject it. However, once the water reaches a natural watercourse or a municipal drain, it must be allowed to continue to flow through all properties.

Accessible description for Figure 4

Obviously, precipitation that falls on the higher property will flow towards the lower property. If the lower property owner objects to the flow of the surface water onto his lands, and the higher property owner has done nothing to collect or concentrate the flow of water from his land, the courts are unlikely to rule against the higher property, since they recognize that water flows downhill naturally.

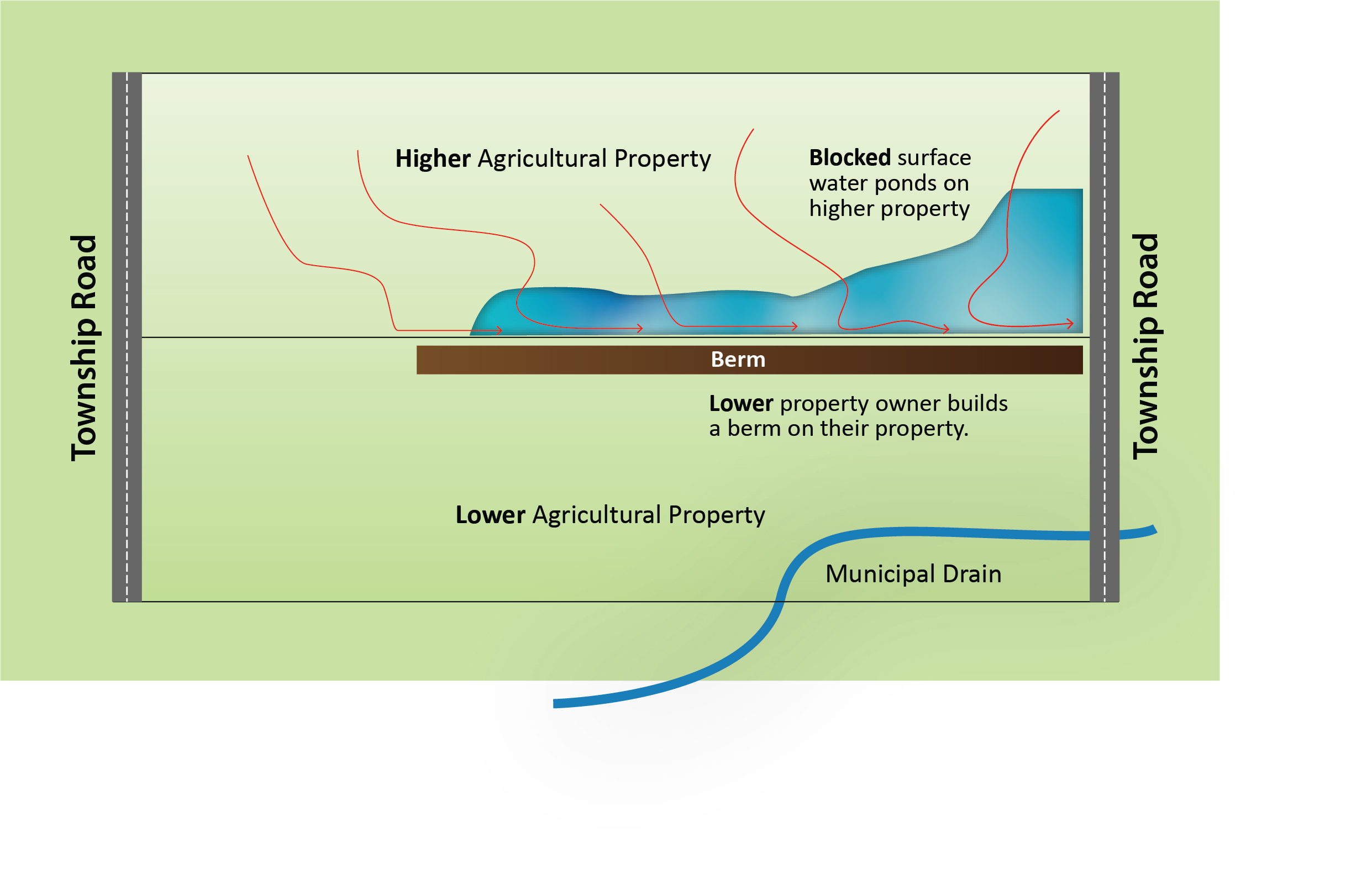

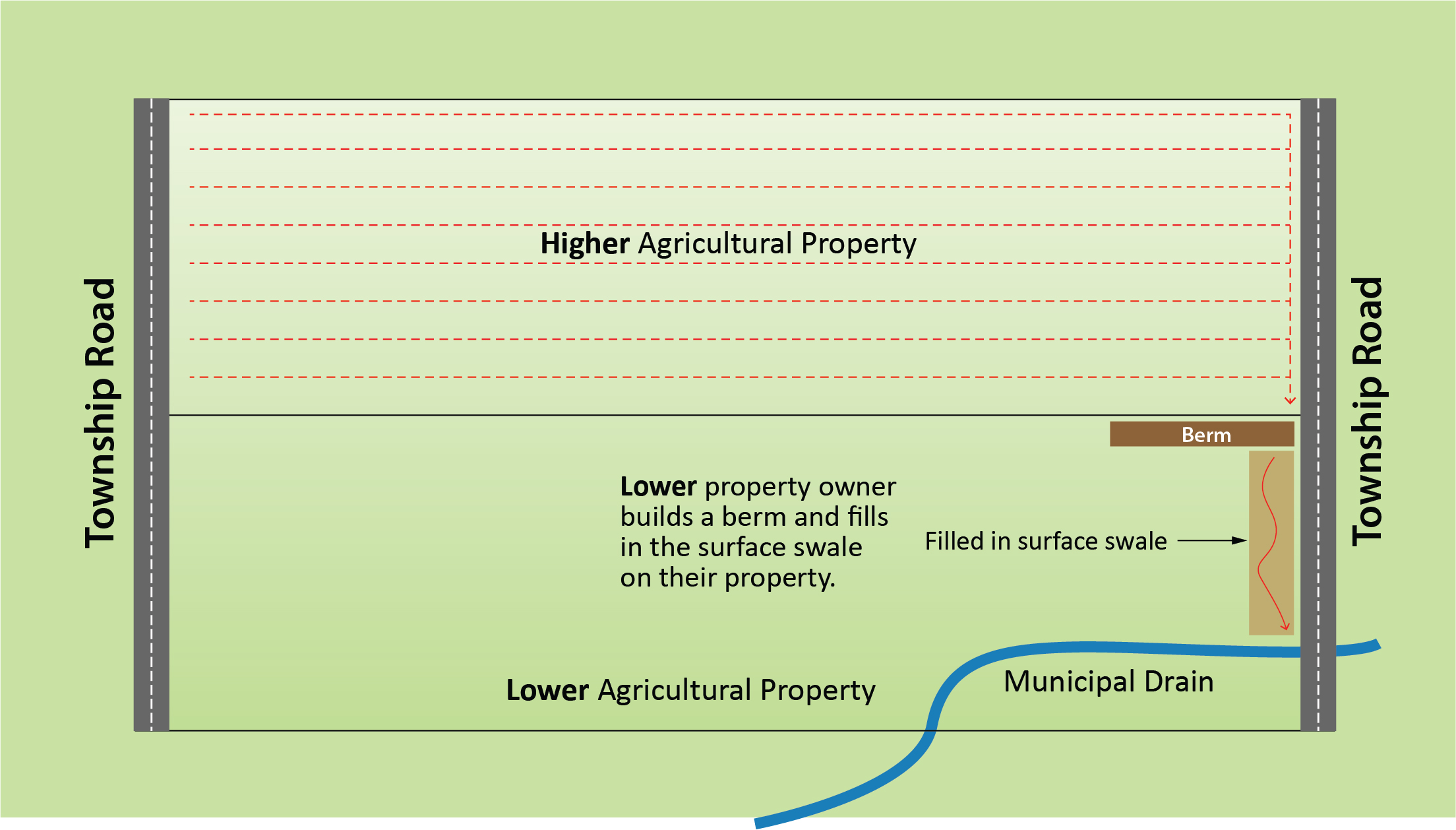

However, if the lower property owner does not want the water, the water can be rejected by building an impervious wall, berm or dyke along the boundary of his property. This will in effect dam the water back upon the higher property (Figure 5). Even though this may cause damage to the higher property, the lower property would not likely be liable, since surface water has no right of drainage. Note that other permits and approvals may be required to import soil onto the property.

Accessible description for Figure 5

The lower property may even raise their property until it exceeds the height of the higher property. This apparent contradictory circumstance would not resolve the issue and would cause hard feelings between the neighbours.

Other options for this situation include negotiating a solution or resolving it using the Drainage Act, 1990, (mutual agreement drain or petition drain).

Lower property owner receiving collected water from a higher property owner

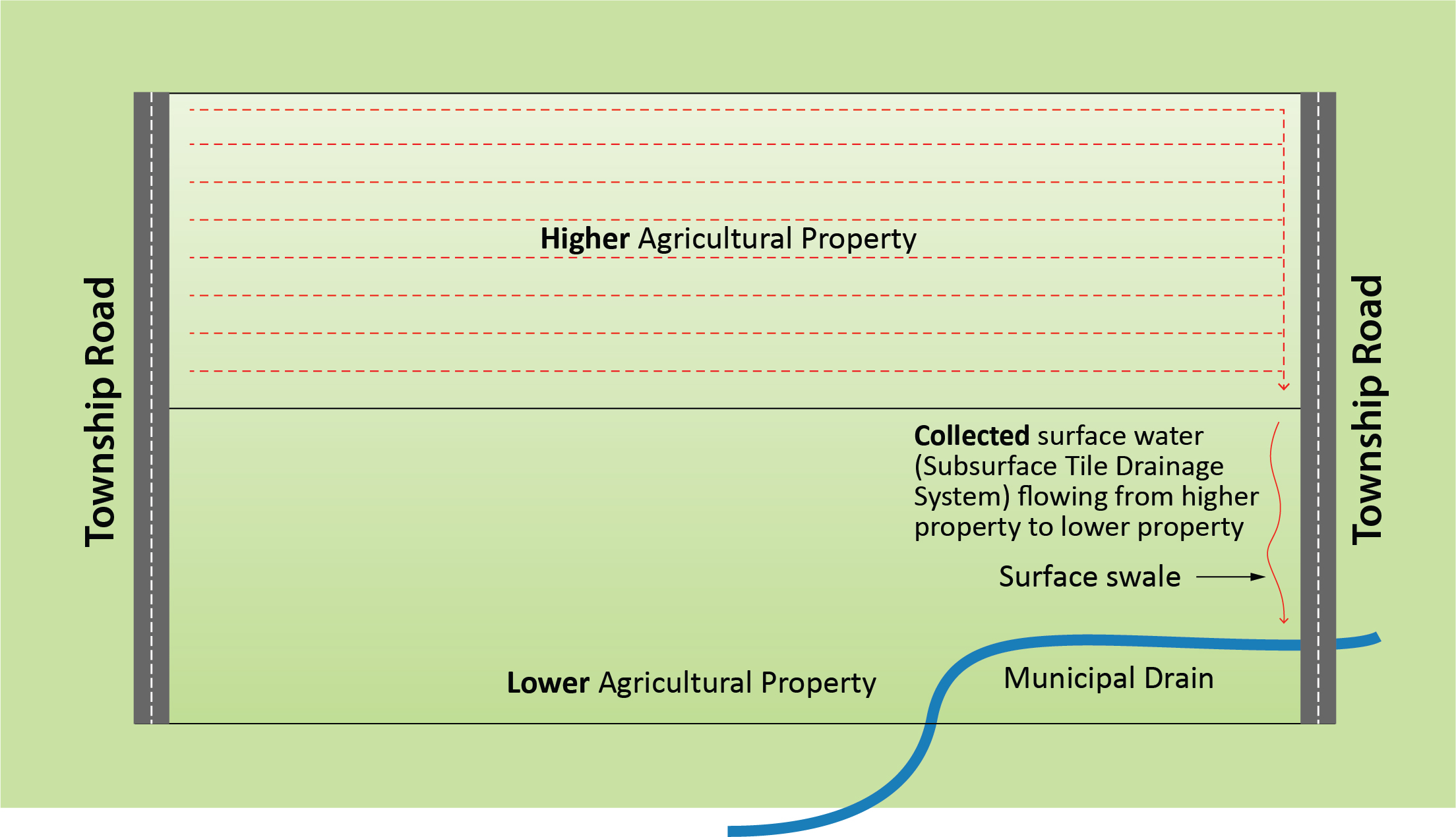

Water from a tile drainage system is considered to be surface water, so it has no right of drainage. Therefore, the situation shown in Figure 6 where the higher property is discharging the tile drain water at the property line is similar to the previous one.

Accessible description for Figure 6

The owner of the lower property could dam the water at the property line (Figure 7) to protect his property. However, since water is being collected and discharged onto the lower property, they could also take legal action against the owner of the higher property. The lower property owner would have to prove the higher property owner is collecting water, discharging it on the lower property and causing damage that can be assessed a dollar value.

Accessible description for Figure 7

When installing tile drains, property owners are obliged to ensure the collected water is taken to a legal and sufficient outlet. Before completing the work, it is necessary to first find a sufficient outlet. They should follow the path the discharged tile water is following and determine if the water would not cause any harm to land or roads. If that is the case, it is probably a sufficient outlet and many potential disputes can be avoided.

However, if there is a private ditch (not constructed under legislation such as the Drainage Act, 1990) on someone’s property, there is no obligation to allow a connection or clean it out for the benefit of a neighbouring property (for example, to accommodate the neighbour’s tile drains). Also, a neighbour is not permitted to trespass on another property to clean a private ditch out, or to dig a new ditch without the owner’s permission, unless there was some previously arranged, written mutual agreement drain document.

Water collected off a roof into an eavestrough is also considered to be surface water and has no right of drainage. This includes water collected from greenhouses and barn roofs, and it must also be taken to a legal and sufficient outlet. The greenhouse owner or farmer could be liable for the damage that this water causes on any downstream properties. Other examples where the collection of surface water can result in liability include:

- private ditches that are not natural watercourses

- swimming pool water

- road ditches

- culverts (not on a natural watercourse or under the Drainage Act) that pass water from one side of a road to the other side

- irrigation water

- water collected in catch basins

- runoff from parking lots and yard areas

Sometimes a new property owner finds a tile draining out onto their property or into their private ditch from a higher neighbouring property after they take possession of the property. Normally, this would not be permitted under common law since the tile water is considered surface water. However, there may be an exception, if the tile outlet has existed for more than 20 years, the drainage has not been changed in that time period and it was not disputed by the previous property owners. In this case, the higher property may acquire the right to drain onto the lower property or into the private ditch through the courts based on prescriptive rights.

Even if the lower property owner has the right to block the water or plug the tile outlet, it would not make for good neighbourly relations. The best option is to discuss the matter with the owner of the tile system and come to an agreement on how to proceed.

If the water is blocked or the tile outlet is plugged, the higher property owner may wish to pursue the following options:

- negotiate a solution

- determine if there is a prescriptive right through the Real Property Limitations Act, 1990

- if prescriptive right is established, seek a potential solution under the Drainage Act, 1990 (such as a mutual agreement drain or petition drain) or take legal action through civil courts after seeking legal advice

- if no prescriptive right is established, seek a potential solution under the Drainage Act, 1990 (such as a mutual agreement drain or petition drain)

Requests to accommodate water from a neighbour’s tile drainage system

An owner of a neighbouring higher property may ask permission to outlet their tile drainage system into your tile drainage system. Tile drainage systems are privately owned, and landowners are under no obligation to let a neighbour connect to it, as long as the tile is not part of a drain under the Drainage Act, 1990. However, it would be neighbourly to come to an agreement on how to collectively manage the water. An owner of a higher property might pay for the privilege of using someone else’s drainage system to reach an outlet, install a second drain beside the existing main drain or upsize the main drain for mutual benefit.

Property owners should be careful they do not put their own tiled land at jeopardy. Water from properties at higher elevations will always drain out first, while land at the lower elevation will drain more slowly if the main drains are already full. Once a connection is made at the property line, it is very difficult for the lower property owner to know what other connections are being made further upstream for other properties. Ensure the main drain is properly designed with sufficient capacity to handle the extra water that will enter the system.

Similarly, there is no requirement for a neighbour of a lower property to let the owner of a higher property run a tile across their property to reach a sufficient outlet. However, it would be neighbourly to come to an agreement that benefits both parties.

If an agreement is reached

If an agreement is reached to let the neighbour run a tile across their farm, the lower property owner is under no obligation to contribute towards the cost of the system. However, if they receive some benefit from the tile, it may be neighbourly to help share the costs.

It is strongly recommended that a written mutual agreement drain document is created to clearly specify what each property owner is expecting of the agreement. Ideally, the agreement should be registered on title of both properties to protect all parties in the case of future sale of either property. Unfortunately, property owners and their lawyers are often reluctant to register mutual agreement drain documents on title because it can make a future property sale less attractive to buyers.

Refer to the OMAFA fact sheet, Mutual agreement drains, for additional information.

If it is not possible to reach an agreement

If it is not possible to reach an agreement, the owner of the higher property could petition the local municipality for a drain across the lower land under the Drainage Act, 1990. If the petition is successful, all neighbours would be forced to pay for their fair share of the costs based on how much water they contribute into the watershed and how much benefit they receive from the drain. In most cases, the petition process of the Drainage Act, 1990, would cost everyone more money than developing a mutual agreement.

There are situations where a petition drain under the Drainage Act, 1990, does not flow through a specific property even though the property paid toward its cost. Contributing toward the cost of a petition drain under the Drainage Act, 1990, does not give a property owner the right to cross someone else’s property with a tile or ditch to gain access to the petition drain. The property has acquired the right to outlet its tile drainage system into the petition drain, but the property must still acquire the right to cross someone else’s private property. This is done either by developing an agreement with the neighbouring property or petitioning the local municipality under the Drainage Act, 1990, for the creation of a branch petition drain that would extend from the main petition drain to the property requiring outlet.

Discharging private tile drainage systems into the roadside ditch

The road department is not required to dig roadside ditches (Figure 8) deep enough to provide outlet for private tile drainage systems, even though they may seem to be conveniently located and a natural choice to discharge to. Road ditches are just another form of private ditch, and the road authorities are only obligated to design the ditch to handle the surface water off the roads. They are not even required to take surface water from surrounding land. Get permission from the road authority in order to discharge private tile drainage systems into them. The only exception is if the ditch along the edge of the road is a drain under the Drainage Act and access for adjacent properties for tile drains is permitted.

Trees and other obstructions on adjacent properties

Trees growing on neighbouring properties may grow close to the shared property lines and can plug tile lines. Property owners cannot force their neighbours to take down their trees to resolve the issue. If approached in a respectful manner, they may agree to remove them for your benefit. It may be possible to prune the tree roots on your side of the property line. However, this may negatively affect the health of your neighbours’ trees. Another option is to replace any perforated tile with solid pipe along the edge of the property.

Proper design of the tile drainage system is essential since some tree roots are known to travel more than 30 m (100 ft). Unless absolutely necessary, do not plant trees too close to property lines, especially water-loving varieties such as willows and poplars. Conversely, do not install tile drains, and especially main collector tiles, too close to property lines that are already treed or are likely to be treed in the future. Refer to OMAFA fact sheet, Farm drainage systems and tree roots for additional details.

Logs and other debris in a natural watercourse adjacent to or downstream of your property cannot necessarily be removed. Anyone who interferes with the channel of a natural watercourse is liable for the damages that result from their actions. Before removing the obstructions, estimate the flow and volume of water being stored to see if the channel downstream can accommodate the sudden increase in flow without damage. Permits may be required from the local conservation authority and Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Disclaimer

This fact sheet serves as a guide. For more detailed information, consult the Agricultural Tile Drainage Installation Act, 1990, the Tile Drainage Act, 1990, Drainage Act, 1990, and associated regulations. If a discrepancy arises between this document and the legislation, the latter prevails. Since the application of the law usually depends upon the circumstances of each case, and as laws may be interpreted differently or changed by court decisions or legislation, this factsheet should not be used by persons with drainage or water problems as a substitute for competent legal advice. This fact sheet does not contain the entire law on the subject of drainage, and there are some portions of the law that may affect the individual which are not dealt with herein or are only briefly touched upon. Individuals should consider obtaining legal counsel for any drainage conflicts/problems that may arise between neighbouring property owners.

Author credit

This fact sheet was written by Tim Brook, P. Eng., drainage program coordinator, OMAFA, and reviewed by James Mitchell, manager, OMAFA, and Andy Kester, drainage inspector/analyst, OMAFA. The authors are indebted to Ross Irwin, P. Eng., John Johnston, P. Eng., Sid Vander Veen, P. Eng., and Hugh Fraser, P. Eng., whose previous work in interpreting the common law aspects of drainage was very helpful in the preparation of this fact sheet.

Accessible image descriptions

Figure 1. OMAFA drainage legislation.

An illustration of an agricultural field with equipment (such as a pickup truck, excavator, tile drainage machine) installing a tile drainage system. At the bottom-left corner of the image is a green vegetated buffer with a municipal drain running across the bottom. The tile drainage system outlets to the drain.

The agricultural field is surrounded by an orange box and the corresponding text box tells the reader that the Tile Drainage Act authorizes the Tile Loan Program to provide a property owner with a loan to assist with financing the installation of an agricultural tile drainage system. The tile drainage equipment is surrounded by a green box and the corresponding green text box tells the reader that under the Agricultural Drainage Installation Act, OMAFA regulates the installation of agricultural drainage systems on agricultural land by issuing licences to each drainage contractor business, tile drainage machine and operator. The river is surrounded by a black line and the corresponding black text box tells the reader that the Drainage Act sets out the process to construct communal drains where the local municipality is responsible for administering the process and the ongoing management of the drainage system.

Figure 4. Lower property owner receiving uncollected surface water from higher property.

A drawing showing 2 agricultural properties with one at the top of the drawing and the other at the bottom. The properties are bordered on the sides by township roads. The bottom property has a municipal drain running along the bottom right side of the drawing. There are a series of lines denoting the flow of surface water from the top property to the lower property.

Figure 5. Higher property owner’s surface water (not collected) is blocked by lower property owner.

A drawing showing 2 agricultural properties with one at the top of the drawing and the other at the bottom. The properties are bordered on the sides by township roads. The bottom property has a municipal drain running along the bottom right side of the illustration. There are a series of lines denoting the flow of surface water from the top property to the lower property. However, there is a berm constructed on the right side of the drawing that stops the flow of surface water from flowing onto the lower property. The water is ponded on the top property as it can not flow to the drain.

Figure 6. Lower property owner receiving collected surface water from higher property owner.

A drawing showing 2 agricultural properties with one at the top of the drawing and the other at the bottom. The properties are bordered on the sides by township roads. The bottom property has a municipal drain running along the bottom right side of the illustration. There are a series of dashed lines on the top property that denotes a tile drainage system that is discharging at the property line of the 2 properties in the middle right side of the illustration. A meandering line denotes that the water discharged from the drainage system flows across the lower property to the drain.

Figure 7. Higher property owner’s collected surface water is blocked by lower property owner.

A drawing showing 2 agricultural properties with one at the top of the drawing and the other at the bottom. The properties are bordered on the sides by township roads. The bottom property has a municipal drain running along the bottom right side of the illustration. There are a series of dashed lines on the top property that denotes a tile drainage system that is discharging at the property line of the 2 properties in the middle right side of the illustration. There is a berm constructed on the right side of the drawing that stops the flow of surface water from flowing onto the lower property and the drain. A swale is also filled in on the lower property that used to flow from the top property to the drain.