Farm drainage systems and tree roots

Learn about farm drainage systems. This technical information is for Ontario producers.

ISSN 1198-712X, published September 2021.

Trees grown on agricultural land can be both profitable and useful, whether in fruit and nut orchards, plantations and woodlots, as windbreaks, fence rows, stream buffers, shelter for pastures and farm buildings, or reforested land.

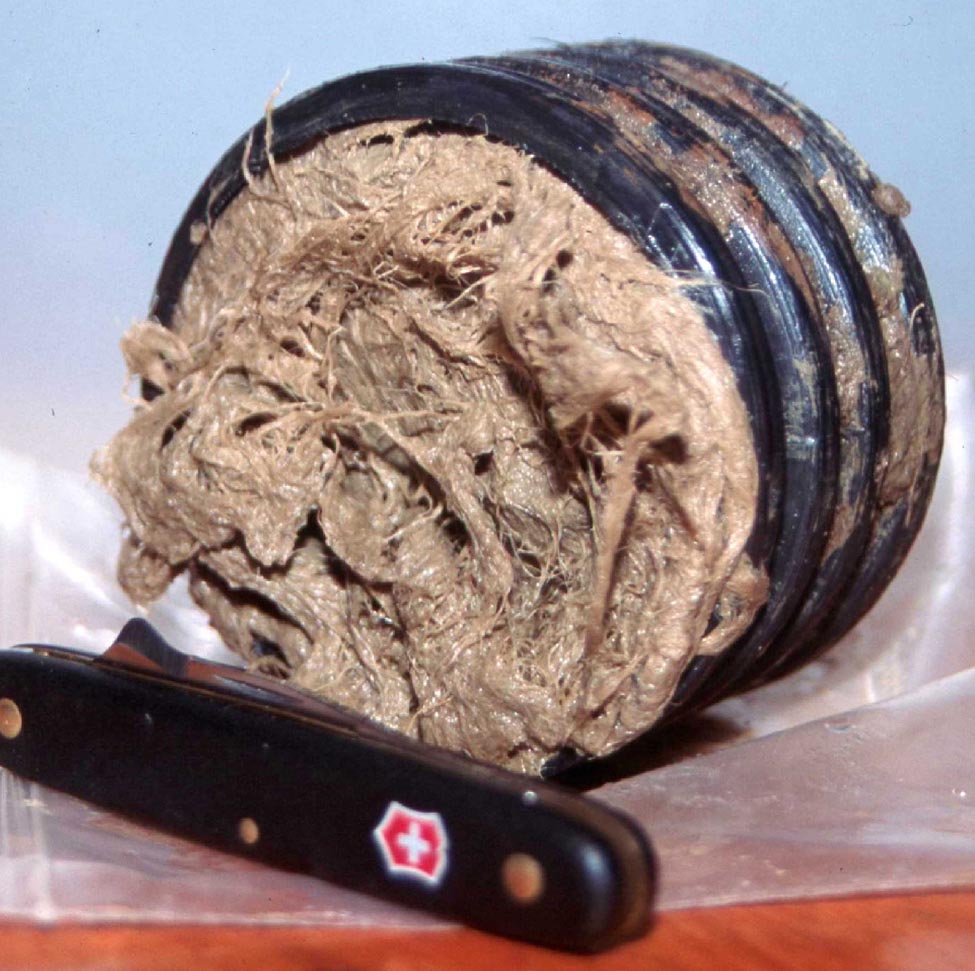

When planting trees on farms with subsurface drainage systems, remember that tree roots can plug drain pipes (Figures 1 and 2). Design your planting to sustain the use of farm drains without blocking them.

Farm subsurface drainage systems

Drainage systems are important for crop production. A properly designed subsurface drainage system should remove excess moisture from the soil profile, providing suitable growing conditions for crop production. Drainage can occur any time of the year but is most common from late winter to early spring, late summer to early winter and sporadically during the growing season due to heavy or prolonged rains. The need for field drainage can vary from growing season to growing season.

Farm drainage systems that have remained fairly dry for several years may run water frequently or constantly if water tables become high. Some subsurface drains can run water constantly.

Drainage lines blocked by tree roots will disrupt proper water drainage and can cause issues throughout the year:

- Winter melt water and spring rains may not drain enough to allow early tilling and seeding, especially on heavy soils.

- Cooler, wet soils can reduce yield by delaying crop germination and growth.

- Summer flooding can remain pooled too long in low spots.

- In late summer and fall, soil may be too soft to permit heavy harvest equipment onto the land.

- Locating and replacing a plugged pipe costs time and money.

Farm drainage systems are a major production investment. Tree plantings added to farmland can also be designed as production investments. The Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA) has several available resources that include recommendations on how to install drainage systems without risking plugging them with tree or shrub roots, and how to maintain drainage systems that may be impacted by tree roots. These recommendations have been established through field experience and are recognized by drainage contractors. If any questions arise, consult with your drainage contractor or the OMAFRA Drainage Program Coordinator.

These resources include:

- Maintenance of a subsurface drainage system

- Considerations when planning to drain land

- Publication 29: Drainage Guide for Ontario

How tree roots grow in the soil

Nutrient uptake, water absorption and anchorage are key functions of roots. Roots grow to new areas of soil to increase the root surface area. Roots grow proportionately with the above-ground tree and maintain a specific root-to-shoot ratio.

The roots of many species of trees, some weeds, and several shrub and crop species can grow close to and into drain pipes as they expand. Roots have easy access to drain pipes if the soil over them has been back-filled and loosened by drainage installation equipment (Figure 3).

Roots do not actively search the soil for moisture and nutrients but grow more vigorously as they randomly encounter more favourable growing conditions, such as increased moisture and nutrient levels. Growth can improve until moisture becomes excessive or nutrients reach toxic levels, at which point root growth declines.

Roots may also develop more vigorously towards an increasing humidity and/or moisture gradient. Soil becomes more pliable with increasing amounts of water, making it easier for roots to push their way through.

Other soil factors, such as oxygen concentrations and soil particle size, also contribute to ease of root growth.

The ideal amount of nutrient or soil moisture is entirely dependent upon the tree species.

How tree roots plug drainage pipes

Roots can plug drainage pipes that are perforated (plastic), have gaps (clay) or are damaged by cracks. Non-perforated pipe cannot be plugged by roots as there are no entry points.

Roots are more likely to be found in pipe after rain following a prolonged dry period, as root systems expand downward to increase water absorption.

A root that enters a dry pipe will likely stop growing but can remain alive. Once running or standing water becomes available inside a pipe, roots may grow to plug the drain. The root will likely not grow if it does not encounter a water source.

The root’s rate of growth and its ability to plug are dependent on the tree species. Roots will also plug pipe more slowly if other sources of water are available outside the pipe during the same period of time.

Conditions that can cause plugging

Roots are drawn to pipes that run water constantly or for an extended duration into the growing season. This water flow can usually be observed at the outlet.

Depth to the water table can vary from one season to the next and depends on seasonal rainfall patterns. Drain pipes that are dry during average growing seasons may have a late flow of water during wet seasons.

A wet spot in a field will be a risky area to establish any tree species, since plugging by roots may eventually occur. Water may run through sections of field drainage later into the growing season without the farmer realizing. Pipes can drain water from an up-slope, wet area or from a spring. However, as the water makes its way down the pipe to drier areas, it can exit the pipe and re-enter the soil through perforations before reaching the drain outlet. In these situations, and unknown to a farmer, trees planted close by could cause root-plugging problems.

At a low field elevation, roots plugging a drain may encourage the proliferation of roots of other trees upstream in the line, since water remains in the pipe upstream of the plug.

Identifying plugged drainage pipes

Drainage problems are first noticeable by the farmer as a wet spot in a field that does not drain as fast as it did in previous seasons or as an area of unhealthy crop. Inspection of outlets may reveal water running later in the spring and early summer. If there have been no recent rains, the water may still be running due to a slow leak in the plug itself — water backed up in the drainage system may simply be taking a much longer time to drain.

The plug may have developed over several seasons. The root growth that created the plug could have continued growing from the previous season in early autumn until as late as December.

An old drainage system may be losing the ability to effectively drain the land due to the accumulations of sediment or to pipe collapse. Plugged sections of pipe must be located and cut out, and a new section spliced into the drain (Figure 4).

Root masses that form within the pipe can occasionally break free from the parent plant and travel downstream, eventually blocking water flow at a different location. These shifting plugs have been found blocking drains of interconnected neighbouring farms, causing crop damage. Determining the origins of the root mass can sometimes be difficult.

Avoiding plugged drainage pipes

Trees

Drains that are within 15 m of trees and that carry water for prolonged periods during the growing season may become plugged with tree roots. If possible, remove all water-loving trees (for example, willow, soft maple, elm and poplar) within 30 m of the drain. Give other trees a clearance of 15 m. If it is not possible to remove the tree or reroute the drain, use continuous non-perforated pipe for a distance of 15 m on either side of the tree.

Install a header drain at the higher end of an orchard to intercept seepage water that might cause prolonged flow in lateral drains.

Stream (riparian) buffers

Stream or riparian buffers are trees, shrubs and weeds associated with wet soils that are established or that grow naturally along a watercourse. The perforated pipe that passes under the buffer to an outlet can quickly become plugged by roots. Install a section of non-perforated pipe for areas that drain into buffered streams, intermittent watercourses or ditches. The non-perforated section of pipe should extend from the outlet, pass under the vegetated buffer and continue for at least 15 m into the cultivated field where it can then connect to standard perforated pipe. Roots will not penetrate non-perforated pipe. This solution provides both worry-free drainage of field water and the added benefits of buffered vegetated watercourses.

Trees that can plug farm drains

Tree species that naturally grow in wet or flooded conditions and are shallow- to intermediate-rooted can proliferate and plug wet drainage pipes. Plugging may occur quickly or may require several seasons of repeated wet conditions.

Shallow-rooted trees have roots that grow laterally for long distances (30 m or more have been observed) and develop primarily within 1 m of the soil surface. They have many fibrous roots that can form very dense root systems, causing thick blockage of drainage pipes.

Most roots of intermediate-rooted trees have uniform thickness and grow outwards and downwards from the tree in a semi-circular pattern. They have some deeper lateral roots but are fairly wide-spreading in growth. They can completely block field drains with many small-diameter roots.

Deep-rooted trees usually consist of one or more deep taproots that extend straight down deep into the soil for many metres with a portion of shallow roots that take up nutrients near the soil surface. The taproots do not tend to spread out laterally and are least likely to plug wet drain pipes unless planted within 1 or 2 m of the underlying drain.

The following tree species can tolerate and grow in saturated soil or free water and should not be planted near perforated field drains:

Shallow-rooted trees

Poplar

- Balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera)

- Eastern cottonwood (Populus deltoides)

- Trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides)

- Largetooth aspen (Populus grandidentata)

- Carolina or hybrid poplar (Populus nigra x Populus deltoides)

Willow

- Golden weeping willow (Salix alba)

- Black willow (Salix nigra)

- Peachleaf willow (Salix amygdaloides)

- Bebb willow (Salix bebbiana)

- Pussy willow (Salix discolor)

- Balsam willow (Salix pyrifolia)

- All other willows

Other

- Speckled alder, grey alder (Alnus incanarugosa)

- European black alder (Alnus glutinosa)

- Flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)

- Black maple (Acer nigrum)

- Manitoba maple (Acer negundo)

- Red maple (Acer rubrum)

- Silver maple (Acer saccharinum)

- Eastern larch, tamarack (Larix laricina)

- Eastern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis)

- Black spruce (Picea mariana)

Intermediate-rooted trees

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

- Black ash (Fraxinus nigra)

- Green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- White ash (Fraxinus americana)

- Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

- Pin oak, swamp oak (Quercus palustris)

- Swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor)

- Sycamore, American plane-tree (Platanus occidentalis)

- Red mulberry (Morus rubra)

- White mulberry (Morus alba)

Deep-rooted trees

- Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa)

- English oak (Quercus robur)

- Black walnut (Juglans nigra)

- Black walnut rootstock (Juglans nigra) with Persian walnut grafts (Juglans regia)

- Common hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

- Bitternut hickory, swamp hickory (Carya cordiformis)

- Shellbark hickory (Carya laciniosa)

Other plants that can plug farm drains

Field horsetail (Equisetum arvense) is a common weed that can plug perforated drainage pipe. Rhizome roots of horsetail can penetrate to more than 1 m below ground, forming thick mats of root.

Other species reported to have plugged farm field drains include:

- brambles

- buttercup

- canola

- dandelion

- dock

- fleabane

- hawthorn

- kale

- meadow grass

- nettles

- rushes

- sugar beet

- watercress

Trees that rarely plug farm drains

Roots of tree species that prefer dry or well-drained soil are least likely to plug farm drains, especially when grown on fast-draining soils. Conditions within the drain may be too wet for the roots to survive.

It is important to know that drain plugging by dry-site trees is rare but can still occur, depending on the situation. For example, roots of peach and black locust have been observed plugging farm drains, and both are dry-site species (Figure 5). The following tree species do not tolerate wet soils for extended periods of time and are least likely to plug farm field drains:

Shallow-rooted trees

- American beech (Fagus grandifolia)

- European beech (Fagus sylvatica)

- Black cherry (Prunus serotina)

- Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)

- European white birch, weeping or silver birch (Betula pendula)

- Paper birch (Betula papyrifera)

- Norway maple (Acer platanoides)

- Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina)

- Eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

- Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus)

- Jack pine (Pinus banksiana)

- Red pine (Pinus resinosa)

- Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris)

- Norway spruce (Picea abies)

- White spruce (Picea glauca)

- Colorado spruce (Picea pungens)

Intermediate-rooted trees

- Apple (Malus sylvestris)

- Sweet cherry (Prunus avium)

- Sour cherry (Prunus cerasus)

- Peach (Prunus persica)

- Pear (Pyrus)

- Plum (Prunus americana)

- Grape, wine and fresh (Vitis labrusca and Vitis vinifera)

- American chestnut (Castanea dentata)

- Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima)

- Sugar maple (Acer saccharum)

Deep-rooted trees

- Red oak (Quercus rubra)

- White oak (Quercus alba)

- Butternut (Juglans cinerea)

- Heartnut (Juglans ailantifoliacordiformis)

- Northern pecan (Carya illinoensis)

- Shagbark hickory (Carya ovata)

- Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera)

This fact sheet was originally authored by Todd Leuty, agroforestry specialist, OMAFRA. It was updated by Tim Brook, drainage program coordinator, OMAFRA, and Jenny Liu, maple, tree nut and agroforestry specialist, OMAFRA.