Final report and recommendations of the Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee

In 2015, we launched a public consultation to gather feedback on what you think is causing the gender wage gap and what should be done to close it. The feedback received during the consultation was considered by the Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee as it prepared a report for the government.

This is the committee’s final report and recommendations to the government on how to close Ontario’s gender wage.

Letter from the committee

The Honourable Kevin Flynn

400 University Avenue

Toronto, Ontario M7A 1T7

and

The Honourable Tracy MacCharles

Minister Responsible for Women’s Issues

14th Floor, 56 Wellesley Street West

Toronto, Ontario M5S 2S3

Dear Ministers Flynn and MacCharles,

As members appointed to the Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee, we are pleased to submit our final report and recommendations for a strategy to close the gender wage gap in Ontario.

We were honoured to be selected to undertake this valuable work. Our mandate was wide in scope, given the complexity of the issue and the long-lasting history of the gap.

There are many government initiatives that directly impact different aspects of this issue. This project addresses the gender wage gap in a coordinated way. As we developed these recommendations, we considered the progress made to date and looked to jurisdictions that are leading the way in developing modern strategies to address the gap.

We attempted to reach as wide an audience as possible and to engage the people of Ontario in a meaningful and informative discussion to understand the impact of the wage gap on women, their families, our communities and our workplaces.

We have many people to thank. First, we acknowledge the many individuals and organizations that participated in the public consultations as well as those who helped us organize regional meetings. The valuable contributions of all who participated are reflected in our report.

Additional heartfelt thanks go to all the staff who helped on the project for their policy research, financial statistics, analysis and support. They cleared paths by coordinating consultations and facilitating administrative and technical needs so that we could focus on the issues. It has been a pleasure working with such dedicated people. We also thank the many staff in other ministries that provided information and support as needed.

It is unacceptable that the gender wage gap still exists. Progress on closing the gender wage gap has been slow and has stalled in recent years. From the consultations, it is clear that people in Ontario are ready for action. Given Ontario’s changing demographics and the need to attract and retain the most talented workforce, closing the gap makes good economic sense.

It will take commitment and action from everyone to meet the challenges before us in reducing and eliminating the gap. We hope that this report provides all Ontarians with a better understanding of this complex issue. Taken together, we believe that the recommendations can form the basis of a government strategy that, when implemented, will contribute to building stronger, fairer and more prosperous communities for everyone in Ontario.

Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee

Nancy Austin

Linda Davis

Emanuela Heyninck

Parbudyal Singh

Executive summary

In the Minister of Labour’s 2014 Mandate Letter, the Premier charged the Minister of Labour with “leading the development of a wage strategy”. This includes working with the Minister Responsible for Women’s Issues and other ministers to develop a wage gap strategy that will close the gap between women and men in the context of the 21st century economy.

The four members of the Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee (the “Committee”) were appointed on April 20, 2015. The committee is made up of two volunteer external members, an Executive Lead from the Ministry of Labour (MOL) and the Pay Equity Commissioner.

With a few exceptions, we met weekly from the time of our appointments. As requested, we were successful in achieving consensus in our recommendations to close the gender wage gap, with the goal of improving the economic and social outlook of Ontario women and families, as well as the province as a whole.

We retained a consulting firm to estimate the potential benefits for the province’s economy from closing the gap. In the course of our considerations, we examined academic and inter-jurisdictional research, solicited feedback from stakeholders and led public consultations with Ontarians.

All of us attended the public consultation sessions held in 14 locations across the province between October 2015 and February 2016. A consultation summary was published April 19, 2016. Other ministries were consulted to help identify current government activities, and to provide information about the possible impacts of actions under consideration.

Our Background Paper provides a detailed discussion of factors of the gender wage gap that reflects research and inter-jurisdictional perspectives. This report focuses on the following areas:

- there are insufficient options for child care and elder care, resulting in women doing more unpaid caregiving and having less time for paid work.

- the sectors and jobs where women and men work are differently valued, with work done by women being undervalued; and,

- there is gender bias and discrimination (intentional or unintentional) in business practices that can prevent women from achieving their full economic potential.

Government, businesses, and other organizations may already have initiatives underway to help them understand and address gender wage gaps. These activities should continue. However, there is an urgent need for further action through an integrated strategy that addresses the key barriers to women’s full participation at work and in the economy.

The recommendations in this report are grouped into five parts:

- Balancing work and caregiving

- Valuing work

- Workplace practices

- Challenging gender stereotypes

- Other ways government can close the gender wage gap.

Key recommendations in part 1 include the need for investments in child and elder care, and development of a parental shared leave policy to help “share the care”.

In part 2, recommendations are aimed at simplifying the pay equity law, in order to support the valuation of work.

Part 3 is focused on workplace practices, and calls for greater pay transparency, gender workplace analysis, and an increase in the number of women on boards.

Challenging gender stereotypes is the theme of part 4, which would raise social awareness generally, as well as in our schools and skills training systems.

Part 5 concludes with recommendations on other ways government can close the gender wage gap, such as performing gender-based analysis, making use of its procurement policies, and helping people access their rights under anti-discrimination legislation.

The report ends with a call to action, noting that there is a role for everyone in helping to close the gender wage gap.

List of recommendations

Recommendation 1:

The government should immediately commit to developing an early child care system within a defined timeframe. The system should provide care that is: high quality, affordable, accessible, publicly funded and geared to income, with sufficient spaces to meet the needs of Ontario families.

Recommendation 2:

To alleviate current stresses and address the gaps in the current child care system, the government, working with municipalities as appropriate, should immediately:

- review access and eligibility for child care fee subsidy programs and make changes to effectively support women, giving priority to those who are trying to improve their job prospects or earning potential and those who are overcoming abusive relationships

- ensure effective use of sliding fee scales and special subsidies

- increase spaces in schools or community hubs based on regional need

- study whether a subsidy can follow the child across geographic boundaries

- consider provincial options to provide incentives for businesses to become partners in the funding or delivery of child care

- take steps to develop a child care program to meet the need for services on a flexible basis, including temporary, short-term or emergency care, as well as the regular need for service outside of ordinary business hours.

Recommendation 3:

The government should alleviate pressures on working families by ensuring there is sufficient capacity in the long-term care system, together with sufficient availability of home and community care services for Ontarians who require assistance to remain at home.

Recommendation 4:

The government should combine the job-protected pregnancy and parental leave provisions in the Employment Standards Act, 2000 to establish a Parental Shared Leave.

Recommendation 5:

To encourage the use of the Parental Shared Leave by both parents, the provincial government should ask the federal government to coordinate Employment Insurance benefits with the Parental Shared Leave and to increase the amount payable.

Recommendation 6:

The government should address barriers to compliance and support employers in ongoing obligations by amending the Pay Equity Act.

Recommendation 7:

The government should assess the state of proxy pay equity and examine ways to coordinate achievement of pay equity with wage enhancement programs in the Broader Public Sector (BPS).

Recommendation 8:

The government should consult with relevant workplace parties on how to value work in female-dominant sectors using pay equity or other means.

Recommendation 9:

The government should:

- encourage the BPS, Ontario businesses and other organizations to develop pay transparency policies and to share organizational pay information with their employees

- develop and adopt pay transparency policies for the Ontario Public Service (OPS)

- set an example by publicizing information or data on the Ontario Public Service’s compensation or salary ranges by gender

- consider legislation to include protection against reprisal for employees sharing their personal pay information.

Recommendation 10:

To help employers identify and take corrective actions to close gender wage gaps in their organizations, the government should immediately consult on and develop a gender workplace analysis tool. It should be simple to use and readily accessible.

Recommendation 11:

The government should require publicly traded companies to ensure diverse representation of women on boards to a minimum of 30%, with appropriate penalties for non-compliance.

Recommendation 12:

The government should examine and report on the gender balance of its appointments to provincial agencies, boards and commissions.

Recommendation 13:

The government should develop a prolonged and sustained social awareness strategy to:

- help people understand the impact of gender bias

- promote gender equality at home, at work and in the community

- increase the public’s understanding of the causes of the gender wage gap and why it is important to close the gap

Recommendation 14:

The government should ensure that all aspects of the education system are free of gender bias.

Recommendation 15:

The government should develop an action plan to support employment and skills training and help increase women’s participation in male-dominant skilled trades and men’s participation in female-dominant ones.

Recommendation 16:

The government should ensure that employment and skills training programs help women succeed in getting and keeping jobs they are trained for.

Recommendation 17:

The government should require all ministries to apply gender-based analysis to the design, development, implementation, and evaluation of all government policies and programs.

Recommendation 18:

The government should perform gender responsive budgeting to account for gender effects of public spending and revenues and to redress gender inequalities through the allocation of public investments and resources.

Recommendation 19:

The government should develop procurement policies that require vendors and suppliers to provide information showing there are no unresolved orders or decisions against them under anti-discrimination laws.

Recommendation 20:

To help people resolve gender workplace issues involving employment, compensation, or discrimination, the government should consider how to ensure employees understand their rights and obligations, and how to access justice.

Introduction

Direction

In the Minister of Labour’s 2014 Mandate Letter, the Premier charged the Minister of Labour with “leading the development of a wage strategy”. The Premier stated:

"Women make up an integral part of our economy and society, but on average still do not earn as much as men. You will work with the Minister Responsible for Women’s Issues and other ministers to develop a wage gap strategy that will close the gap between women and men in the context of the 21st century economy."

Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee

The four members of the Gender Wage Gap Strategy Steering Committee (the “Committee”) were appointed on April 20, 2015. The committee is made up of two volunteer external members, an Executive Lead from the Ministry of Labour (MOL) and the Pay Equity Commissioner (see Appendix 1).

Mandate and scope

The Committee was appointed to examine academic and inter-jurisdictional research, solicit feedback from stakeholders and lead public consultations with Ontarians to:

- examine how the roles of women at work, in their families, and in their communities are affected by the gender wage gap

- understand how the gender wage gap specifically affects women in the workforce, across the economic spectrum

- assess ways in which government, business, labour, other organizations, and individual leaders can work together to address the conditions and the systemic barriers that contribute to the wage gap

- understand other factors that intersect with gender to compound the wage gap, and determine how those factors should be addressed

- consider whether Ontario’s existing laws sufficiently address some of the factors leading to the gender wage gap.

MOL’s Executive Lead consulted other ministries to help identify current government activities and to provide information to the Committee about the possible impacts of actions under consideration.

As a Committee, we were asked to arrive at a consensus in making recommendations to close the gender wage gap, with the goal of improving the economic and social outlook of Ontario women and families, as well as the province as a whole.

With a few exceptions, we met weekly from the time of our appointments. We also communicated regularly through email and teleconferencing. All of us attended the public consultation sessions held in 14 locations across the province.

Considerations guiding the recommendations

In arriving at consensus, we took into account the:

- Need to seek many diverse views: During the consultations we met with workers, representatives of organizations, employers, unions and advocacy groups from both private and public sectors

- Impact on government and business, including current economic pressures

- Importance of the human rights aspect of this problem, including international and federal commitments

- Need for a range of policy and program options, because closing the gender wage gap will involve identifying and linking many issues and finding multiple solutions, often over time

- Importance of using research and evidence to add context to the experiences shared by participants

- Effect of gender stereotyping and biases at the individual, organizational and societal levels, as we learned from consultations and through research

- Impact of gender wage gaps for people who have historically experienced multiple disadvantages, including women with disabilities, Aboriginal and racialized women, who face additional barriers in getting and keeping work

- Other strategies the government is pursuing that may impact aspects of the gender wage gap. These strategies need to work together.

Sharing Experiences

We started the conversation with the release of a background document and two consultation papers. During the consultations, we discussed the work-life cycle as a framework for people to think about the ongoing economic impact of the gap, as well as the effect that social norms and biases have at different points in their lives. Ontarians shared how important it is to close the gender wage gap, to them and to their families.

From October 8, 2015 to February 22, 2016, public town hall sessions and meetings were held with a broad cross-section of people, including representatives from local businesses, advocacy groups, communities, plus women and men across the province.

The consultations gave Ontarians the chance to discuss work-life and pay issues, as well as causes and solutions for closing the gender wage gap. Individuals and organizations could also share their feedback by sending written responses to questions posed in the consultation papers or by completing an online survey.

We met with over 170 stakeholders, representing thousands of Ontarians, and received 75 written submissions and 1,430 online survey responses. Five hundred and thirty people attended the public town hall sessions.

The Consultation Summary was released April 19, 2016. We appreciate everyone’s contributions and the time people took to get involved and share their experiences. Our recommendations reflect what we heard, read, and studied.

Work-Life Cycle

- Role modelling

- Entry into the workforce

- Mid-career

- Re-entry into a career

- Heading to retirement

- Being a retiree

Background

Opportunities in the 21st century economy

Ontario’s economy is changing. We heard first-hand about the impact of some of these changes on working women and men, such as the:

- increase in non-standard working relationships – temporary jobs, involuntary part-time work self-employment, and shift-work

footnote 1 - decline in traditional collective representation and bargaining and

- growing importance of caregiving professions to look after people from cradle to grave

Other changes are also being felt in the economy as a whole. These include:

- globalization – the interaction and integration of people and organizations across countries

- technological changes – to production and to learning; impacting both goods and services

- a move towards knowledge-based enterprises – such as information communication technology and life sciences

- new forms of work organization – from mass, large scale, standardized production with hierarchies to smaller scale, flexible, flatter organizations

- the rise of the sharing economy

footnote 2 – new models of consuming and accessing goods and services.

Supporting women, as well as men, to earn to their potential can give Ontario businesses an advantage in a highly competitive global economy. Given the province’s changing demographics,

Economic case for closing the gender wage gap

By addressing the barriers that limit women’s full contribution to the economy, society benefits by: increases in consumer spending and tax revenue, decreases in social spending and health care costs, and getting a better return on investments in education. Not taking action has been, and will continue to be costly for all Ontarians.

We retained a consulting firm to estimate the potential impact on the province’s economy from closing the gap. According to Deloitte LLP (Deloitte), a qualified working woman who has same socio-economic and demographic characteristics (e.g., education level, age, marital status), and experience in the workplace (e.g., job status, occupation, and sector) as a man, on average receives $7,200 less pay per year.

Closing the gender wage gap would also have implications for Ontario’s government revenue. Deloitte estimated that revenues from personal and sales tax could increase by $2.6 billion. They also estimated that government spending on social assistance, tax credits, and child benefits could decrease by $103 million, due to the projected increase in families’ income.

Addressing gender inequality

While the economic case is compelling, so is the human rights case for addressing gender inequality. Canada has signed several international human rights conventions to address gender inequality and eliminate gender discrimination (see Appendix 6). Where these conventions contain provisions that fall under provincial or territorial jurisdiction, the Government of Canada consults and seeks the support of provincial and territorial governments before signature, and looks to the provinces to then support the terms of these conventions in areas of provincial control.

Over the years, Ontario has taken steps to support Canada’s international obligations by introducing and implementing the:

- Ontario Human Rights Code

- Equal Pay for Equal Work provisions of the Employment Standards Act, 2000

- Workplace Violence and Harassment provisions of the Occupational Health and Safety Act

- Pay Equity Act and

- Accessibility for Ontarian’s with Disabilities Act

Measuring the gender wage gap in Ontario

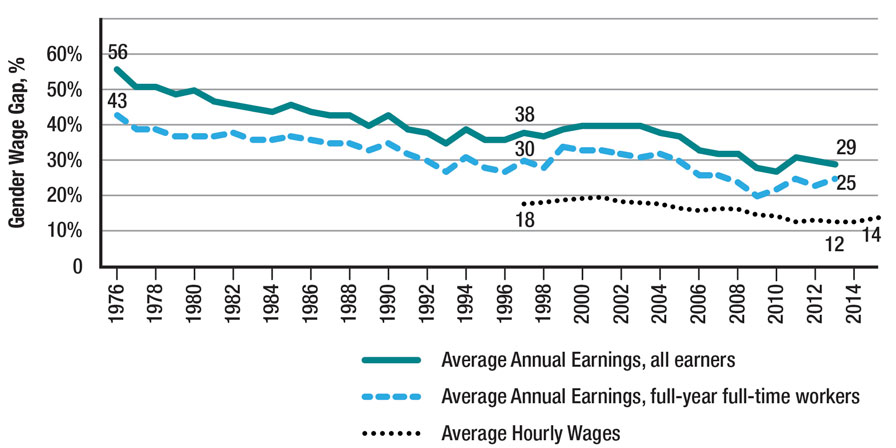

The gender wage gap is a number that is used to show the estimated difference between women’s and men’s pay. It is often expressed as a percentage. Numbers never tell the whole story, but they are useful in understanding the impact of the gap.

The gender wage gap can be measured in different ways.

- 14% (average hourly wages)

footnote 8 - 25% (average annual earnings, full-time, full-year workers)

footnote 9 - 29% (average annual earnings for all earners including: full-time, full-year, seasonal and part-time workers)

footnote 10

When presented with this range of measurements, people may ask “Which is the real gap”? The fact is they all illustrate the gap.

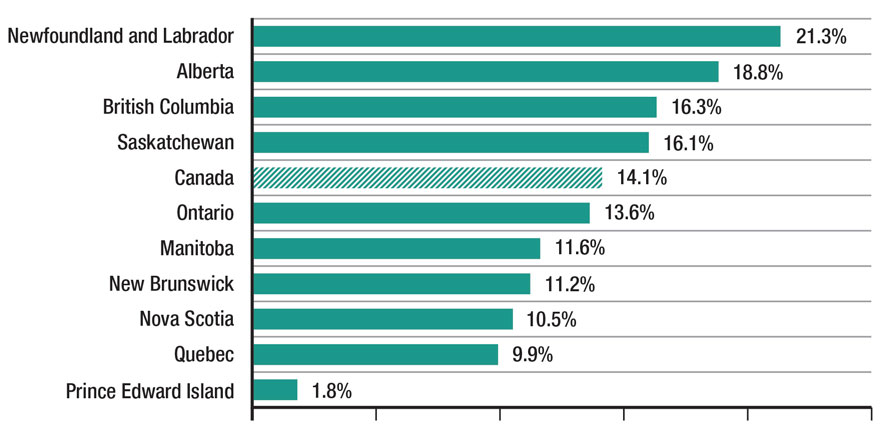

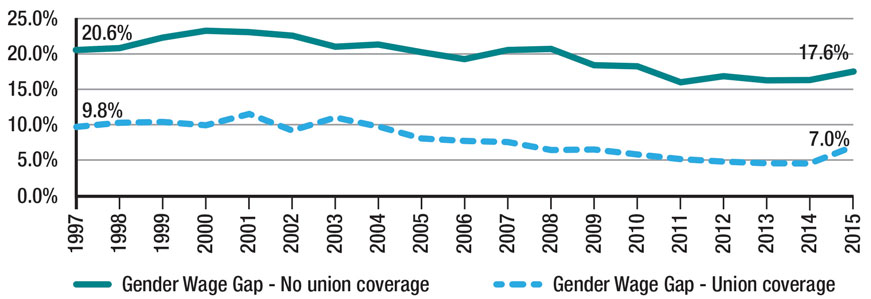

In addition, the gender wage gap is different depending on the group of workers. For example, the gender wage gap is (see Appendix 3):

- smaller for unionized workers compared to non-unionized workers

footnote 11 - zero between women and men who earn minimum wage on an hourly basis: but more women than men hold minimum wage jobs

footnote 12 - larger between women and men from groups who have historically experienced employment disadvantage, such as racialized and Aboriginal people and people with disabilities (i.e., intersectionality)

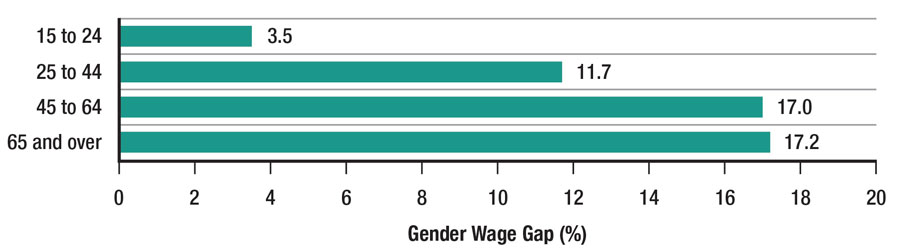

footnote 13 - smaller for youth than for older workers.

footnote 14

Although smaller for youth, studies show that there is still a gender wage gap among younger, more educated generations. For example, a recent study at one Ontario university showed that there are significant gender differences in the earning patterns of university graduates, with male graduates earning $10,000 more than females in the first year after graduation. Thirteen years after graduation, the gender earnings gap grew to around $20,000, regardless of the discipline studied.

We also know that the gender wage gap can accumulate in impact over time. As women earn on average less than men through their working lives, the differences in their employment incomes will increase through the years. Since retirement income mainly flows from employment earnings, this leads to a gender pension gap and can put women at greater risk of poverty when they retire.

A recent International Labour Organization report estimated that the worldwide gender wage gap would take 70 years to close at the current rate.

Causes of the gender wage gap

Researchers take into account various factors that may affect the gender wage gap.

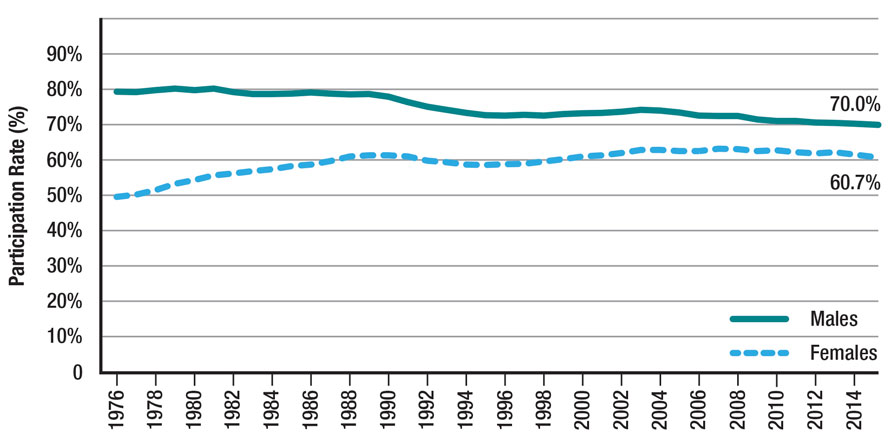

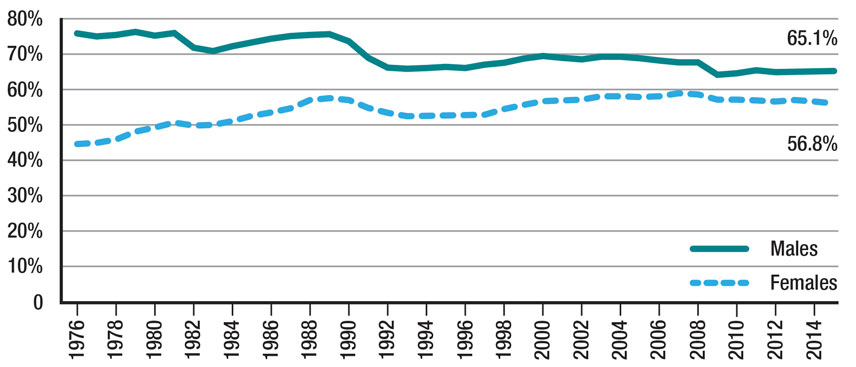

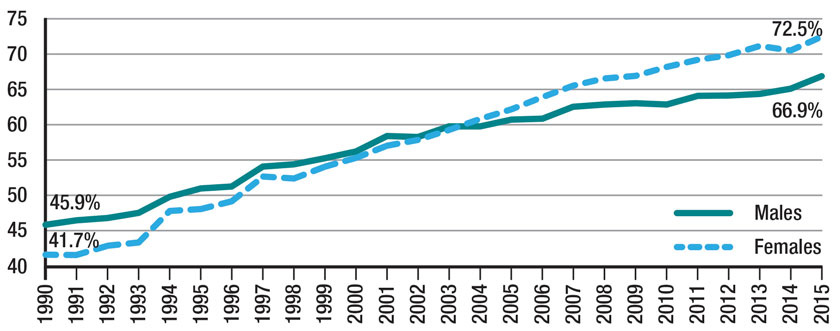

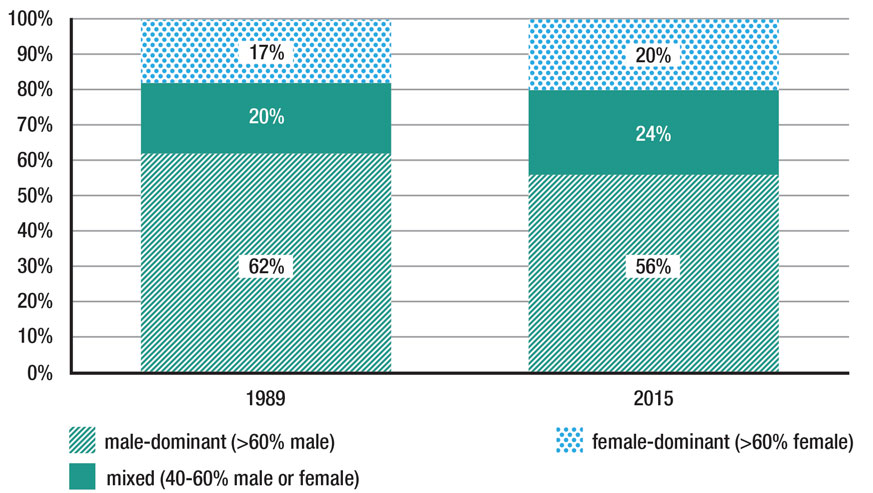

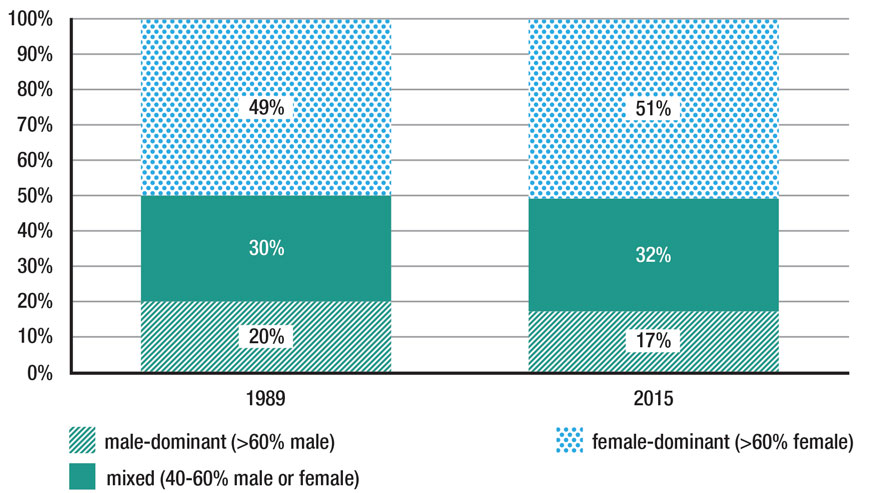

More recently, however, there have been significant increases in women’s levels of education and participation in the labour market (see Appendix 4). That this has not significantly affected the gender wage gap means that there are other factors involved. These include the effects of gender stereotyping, conscious or unconscious bias and discrimination in other areas of life and work.

We learned that when more women enter male-dominant fields, the pay decreases.

Our Background Paper provides a detailed discussion of factors of the gender wage gap that reflects research and inter-jurisdictional perspectives. We have focused on the following key causes based on what we heard in the consultations and read in our research. In Ontario:

- there are insufficient options for child care and elder care resulting in women doing more unpaid caregiving and having less time for paid work

- the sectors and jobs where women and men work are differently valued, with work done by women being undervalued

- there is gender bias and discrimination (intentional or unintentional) in business practices that can prevent women from achieving their full economic potential.

The gender wag gap is not only a problem in Ontario or Canada. Every country has a gender wage gap. Some countries have smaller gaps than others.

Recommendations

Through our research and consultations we identified a number of barriers that prevent women, and therefore everyone in Ontario, from reaching their full economic potential. Our recommendations cover many settings, from homes, to schools, to workplaces, and provide a range of ideas to help identify and change historical stereotypes and social norms that result in the gender wage gap. Some of them may be relatively quick to implement, but others are aimed at changing attitudes, values and beliefs over time.

Government, businesses, and other organizations may already have initiatives underway to help them understand and to address gender wage gaps. These activities should continue. However, there is an urgent need for further action through an integrated strategy that addresses the key barriers to women’s full participation at work.

The recommendations which follow are grouped into five parts:

- balancing work and caregiving

- valuing work

- workplace practices

- challenging gender stereotypes

- other ways government can close the gender wage gap

Change will require sustained political will, commitment, and resources from everyone.

Part 1: Balancing work and caregiving

Many stakeholders shared stories that reflect the need for better options to care for their families. This ranged from access to quality, affordable child and elder care, to the reluctance to make use of parental leaves due to a lack of workplace support.

"…you can’t close the gender wage gap until you have better childcare" *all quotes from consultation participants

Ontario’s current care structure, for children, elders, and others relies on unpaid caregiving, the majority of which is done by women. Caregiving affects women’s employment more than it does for men. Research shows that women are more likely to miss days at work, retire earlier, quit or lose their job, or turn down job offers due to unpaid care activities.

During our consultation process we heard about cases where jobs were not offered, career advancement was stalled, or raises were denied following parental leave. Women and men told us that even though they have the right to take the leave, they did not feel supported when they did. Some felt stigmatized or were threatened with dismissal.

Researchers from the United States have found that the motherhood wage penalty of 4% per child cannot be explained by skills and experience, family structure, family-friendly job characteristics, or other differences among women.

Ontario’s family and employment patterns show a continuing shift towards dual-income families. The majority of women are employed. Many more women return to work after starting a family. The proportion of families where both parents are working is increasing. The number of dual income families in Ontario grew from 42% in 1976 to 68 % in 2014.

More men are beginning to “share the care”, but women are still more likely to provide unpaid caregiving and spend more time doing it.

Share the care

Our recommendations under “share the care” aim to support all types of families in balancing caregiving and work. “Share the care” is meant broadly: sharing between women and men, within and across households; sharing through the public provision of child care; having employers, unions and employees recognize that business models should take into account the family lives of employees.

Working families need family-work policies and programs that reflect the current realities of the “sandwich” generation who may be juggling both child and elder care.

A. Invest in child care

During the consultations, we heard about the need for child care from every community. People clearly said they needed available, accessible and high quality child care. Research shows that high quality child care is good for the economy and for working families, especially mothers.

"…if Québec can have an affordable childcare program that is safe and accessible, so can Ontario”

Many nations and regions now view child care as necessary to strengthen economic prosperity. It encourages high levels of employment by helping families combine work and family responsibilities. Research indicates that where affordable, quality child care is available, women are more likely to work, stay employed and hold better jobs,

Some jurisdictions have come to consider child care as an essential social infrastructure for economic growth and fund it accordingly.

During our consultations, participants referred to Québec’s universal, government-subsidized system. It is currently being revised to first address low income earners’ accessibility to the program and cost-sustainability. Québec’s program is linked to increases in mothers’ labour market participation and employment (especially in single-parent families), increased tax revenues, and cost savings from reduced numbers of people receiving social assistance and other benefits.

We have two recommendations with respect to child care. The first is aimed at developing a system to meet the needs of working women who are trying to get, keep, or extend their hours of work, or advance in their jobs and careers. The second addresses immediate pressures and gaps in the current system that have been identified.

Recommendation 1:

The government should immediately commit to developing an early child care system within a defined timeframe. The system should provide care that is: high quality, affordable, accessible, publicly funded and geared to income, with sufficient spaces to meet the needs of Ontario families.

- The system should be for those who are working, or in education or skills training

- In the first year, the government should present a plan on how and when it will achieve the system

- At the same time, the government should encourage the federal government to proceed with and fund a national child care strategy

- The government should report on its progress annually

Investments must begin immediately. There is a benchmark for funding that we have found useful: Twenty years ago, the European Commission Network on Childcare proposed that public expenditure on child care should be no less than 1% of GDP as a financial target.

“I had to find a job while pregnant, had to negotiate a shortened maternity leave …. – the biggest issue is childcare - the biggest problem is finding childcare for more irregular hours – what about respite care?”

Although Ontario has doubled funding for early childhood education and care to $1 billion annually, spending still amounts to only 0.6% of GDP. In comparison, Québec spent 1.2%.

Investments in child care contribute towards identified economic benefits such as increased taxes paid by working parents and reduced social service costs.

While the government is developing a child care system to support Ontario’s 21st century economy, immediate improvements can be made to its existing program. Some steps have already been taken

However, despite recent program enhancements, in 2014-2015, only 20% of Ontario children up to 12 years old were in licenced childcare programs.

Recommendation 2:

To alleviate current stresses and address the gaps in the current child care system, the government, working with municipalities as appropriate, should immediately:

- review access and eligibility for child care fee subsidy programs and make changes to effectively support women, giving priority to those who are trying to improve their job prospects or earning potential and those who are overcoming abusive relationships

- ensure effective use of sliding fee scales and special subsidies

- increase spaces in schools or community hubs based on regional need

- study whether a subsidy can follow the child across geographic boundaries

- consider provincial options to provide incentives for businesses to become partners in the funding or delivery of child care

- take steps to develop a child care program to meet the need for services on a flexible basis, including temporary, short-term or emergency care, as well as the regular need for service outside of ordinary business hours.

“…women are still doing the caregiving roles – we haven’t made the shift to share the responsibility [between] men and women"

B. Support for elder care

The number of seniors in Ontario is expected to double to more than four million by 2041, which means there will be an increased need for elder care.

In Ontario, about 1.8 million women were unpaid caregivers in 2012.

Research has shown that family caregiving can result in loss in employment income, exits from the labour market, risk of financial insecurity,

There are potential consequences for employers who cannot provide flexibility to help employees juggle family care with work. Productivity may be affected, as employees may be absent, distracted or burnt out.

The government has a number of initiatives already underway to transform the health care system.

While a comprehensive costing of options is beyond the scope of this project, the research does suggest key health system challenges can be addressed with increased investment and delivery of home and community care services for older people so that they can remain at home longer.

Recommendation 3:

The government should alleviate pressures on working families by ensuring there is sufficient capacity in the long-term care system, together with sufficient availability of home and community care services for Ontarians who require assistance to remain at home.

C. Parental shared leave policy

Job protected leave policies allow parents to remain connected to their workplaces. While parental leave in Ontario is available to women and men, women are more likely than men to take it.

Currently, Québec is the only province in Canada that offers targeted paternity leave—providing five weeks only to fathers,

Job-protected leaves in other jurisdictions vary considerably in terms of the level of financial support as well as the factors that encourage partners to take the leave. Three Nordic countries—Finland, Norway and Sweden—stand out with policies that promote gender equality.

After the introduction of father portions in Norway, the number of fathers taking leave increased from 4% to 89% in 10 years and in Sweden, 75% of fathers took parental leave in 2011.

Under Ontario’s Employment Standards Act, 2000 (ESA), eligible employees have the right to take job-protected unpaid pregnancy leave of up to 17 weeks. Both new parents have the right to take unpaid parental leave of up to 35 (birth mother) or 37 weeks (for all other new parents). The leaves are coordinated with the federal Employment Insurance Act, which provides maternity and parental benefits payable to the eligible employee in the amount of 55% of average weekly earnings during the period the individual is off work on an ESA pregnancy or parental leave (to maximum of 52 weeks).

Table A: job-protected pregnancy and parental leave policies in Ontario, Employment Standard Act, 2000

| Reason for leave | Eligibility for leaves | Maximum number of weeks of leave |

|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy (exclusively for the woman who gave birth) | Due date is at least 13 weeks after starting employment | 17 |

| Parental | Employed by the employer for 13 weeks | 37 weeks (Birth mothers who take pregnancy leave are entitled to up to 35 weeks) |

Table B: maternity and parental benefits in Ontario Federal Employment Insurance Act

| Reason for benefit | Eligibility for benefits | Maximum number of weeks of benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Maternity (exclusively for the woman who gave birth) | Employees who have accumulated at least 600 hours of insurable employment during the qualifying period | 15 |

| Parental | Employees who have accumulated at least 600 hours of insurable employment during the qualifying period | 35 weeks can be shared by parents |

We learned that Ontarians support the use of parental leaves to help with family-work life balance and caregiving. Participants also said there needed to be more flexibility in leave policies so that parents would not have to take their leaves all at once. Shared parental leave, with reserved portions for each parent, aims to make it normal in workplaces to have both parents take time off to raise their children.

Job protected leaves with a “use it or lose it” feature may provide incentives to workers to return to their previous jobs, and save employers hiring and training costs. If shared equally between the parents, the new leave provision may help promote retention of skills, due to earlier return to work for both parents.

Recommendation 4:

The government should combine the job-protected pregnancy and parental leave provisions in the Employment Standards Act, 2000 to establish a Parental Shared Leave.

The leave should have:

- designated pregnancy, first parent and second parent allocations; reserving time specifically for each parent on a “use it or lose it” basis, and

- options for flexible use to facilitate ease of re-entry into employment

Recommendation 5:

To encourage the use of the Parental Shared Leave by both parents, the provincial government should ask the federal government to coordinate Employment Insurance benefits with the Parental Shared Leave and to increase the amount payable.

If coordinated federal benefits are not available to support the Parental Shared Leave, then the provincial government should explore options for a provincial insurance benefit plan with flexible options to top up current EI rates, or explore other options to fund leaves such as a registered leave savings plan, modelled after the Registered Education Savings Plan.

Part 2: Valuing work

Work performed or dominated by women has historically been, and continues to be, undervalued. This is a major contributor to the gender wage gap. There are two main methods for ensuring that women are compensated for the value of their work: equal pay for equal work and pay equity (equal pay for work of equal value). Both pay equity and equal pay for equal work have been identified as a human right by Canada, federally, and by the United Nations.

In Ontario, equal pay for equal work and pay equity are found in two pieces of legislation, described below. They are enforced by separate bodies, using different mechanisms and criteria.

The Employment Standards Act, 2000 covers equal pay for equal work

This provision requires women and men to receive equal pay when they do the same or substantially the same job in the same establishment.

The Pay Equity Act covers equal pay for work of equal value (or pay equity)

Pay equity requires employers to pay female jobs at least the same as male jobs if they are of comparable value, based on skill, effort, responsibility and working conditions.

Equal pay for equal work

During our consultations, many women told us they are not paid equally when performing the same work as their male colleagues. We heard that it is hard to understand the difference between the concepts of “equal pay for equal work” and “pay equity”, and how each applies. Many American states are legislating “pay equity” laws: closer analysis shows that these are addressing equal pay for equal work. This may add to the confusion in the public’s mind.

Pay equity

Pay equity has been a legal requirement in Ontario since 1987 under the Pay Equity Act (PEA), enforced by the Pay Equity Commission. It applies to all public sector employers and to all private sector employers with 10 or more employees. The pay equity process is meant to uncover gender bias in compensation systems that may favour work historically done by men, over work historically done by women, using recognized compensation comparison techniques.

Québec also has a stand-alone pay equity law with an independent enforcement agency

The Québec legislation addresses the issue of escalating liabilities for non-compliance by including requirements for employers to file reports on pay equity implementation and maintenance, and setting a maximum period for calculating pay equity adjustments.

At the federal level, the 2004 Task Force on Pay Equity recommended a proactive pay equity law and an independent pay equity agency to enforce it. The current federal government has recently struck a legislative task force by adopting a motion that “calls on the government to implement the recommendations of the 2004 Pay Equity Task Force Report”.

A. Simplifying pay equity laws

During our consultations we heard strong support for the continuance of the Ontario Pay Equity Act as currently administered, with a call for increased resources and better, more robust enforcement.

We also heard that that the Act needs to be simplified, so that it can:

- clearly state how pay equity, once achieved, can be maintained in workplaces that need to make changes to their compensation systems or add new job classes, for example

- make sure that all employers, especially new ones, are aware of their pay equity obligations. By the time it is realized, significant liability can be attached to failure to comply, and this in turn becomes another barrier to compliance. It may also mean that employees in female-dominant jobs are not getting the pay adjustments to which they are entitled

- re-examine the role of workplace parties and the interaction between collective bargaining and pay equity

- consider who needs to be covered by pay equity, in light of the changing nature of workplace relationships.

Recommendation 6:

The government should address barriers to compliance and support employers in ongoing obligations by amending the Pay Equity Act.

After appropriate consultations, government should consider:

- setting a defined time period to bring forward current complaints for non-compliance and retroactive payments

- setting regular intervals for employers to report on changes to their compensation practices and the impact on pay equity

- limiting retroactive payments to claims that arise within the reporting period

- defining the employer-employee relationship to better reflect 21st century workplace relationships

- transferring the equal pay for equal work provision from the Employment Standards Act to the Pay Equity Act

- clarifying the role of unions and employees

- clarifying the requirement to maintain pay equity

In addition, the government should ensure the enforcement agency for the Act has sufficient capacity to support its role.

B. Female-dominant sectors and pay equity

Female-dominant jobs can be undervalued within organizations and by sector. The majority of female-dominant work is found in caring professions in the public sector, including home care, community living, child care, and domestic violence. Women in female-dominant sectors could not access pay equity remedies until 1993, when the proxy method was added to the Act.

The proxy method allows certain public sector employers with only female job classes to borrow job descriptions and salary information from another public sector employer (the proxy employer) with similar female job classes, to make comparisons and establish pay equity job rates. The Act requires employers to apply 1% of payroll each year to increase wages and thus achieve pay equity over time.

Québec’s Pay Equity Act has regulations that establish male comparators in female-dominant sectors in both the public and private sectors. New Brunswick achieves pay equity in its Broader Public Sector by negotiating standardized job descriptions and establishing male comparators, sector by sector, with the relevant unions and then also applying the rates to non-unionized environments.

During our consultations, we heard from stakeholders about the complications of Ontario’s proxy method:

- proxy is available only as a point-in-time solution and only covers eligible organizations that existed in 1993

- the information from the employers used as a comparator may result in a wide variation in pay equity job rates within the same sector

- the minimum requirement to apply 1% of the organization’s previous year’s payroll to achieve pay equity job rates, together with inconsistencies in dedicated pay equity funding, means that some organizations are still trying to achieve pay equity job rates set in 1994

footnote 64 - the lack of clarity around how to maintain pay equity when using the proxy method is the subject of ongoing litigation

footnote 65 - in many cases, payment of wage increases, without addressing outstanding pay equity obligations, has delayed the achievement of pay equity

More recently, the province has implemented wage enhancement programs in an attempt to raise the wage floors of child care and personal support workers. We heard that these programs, while welcome, have had serious impacts on those employers who are still attempting to achieve pay equity using the proxy method. For example, if the wages of some female jobs are raised through a wage enhancement program, the organization may be required to raise the wages of other female jobs, without the help of a wage enhancement, in order to ensure pay equity requirements are met.

Recommendation 7:

The government should assess the state of proxy pay equity and examine ways to coordinate achievement of pay equity with wage enhancement programs in the Broader Public Sector (BPS).

This may include:

- asking government ministries to work with their transfer payment agencies to assess how much and how long it may take to reach pay equity job rates

- looking at how wage enhancements affect employers who are in the process of achieving pay equity using the proxy method

- exploring whether wage increases should be applied to first achieve pay equity job rates

Even though the proxy method extended pay equity into sectors that were, and continue to be female-dominant, not all employees in female-dominant sectors in or outside the BPS are covered by proxy. For those workers, wages continue to be low despite the fact that their work may require educational and professional qualifications (e.g., for personal support workers, developmental services workers, early childhood educators) and they have challenging working conditions because of the populations they serve.

In the child care sector, we also heard that increasing numbers of students are choosing not to continue their work after initial training because of low wages and limited job opportunities, and current workers are leaving to pursue other career options. As a result, education and training investments are lost. Raising wages, benefits and improving working conditions in these sectors may attract and retain employees, improve the quality of care, and increase the way society values caregiving and other (female-dominant) work.

Recommendation 8:

The government should consult with relevant workplace parties on how to value work in female-dominant sectors using pay equity or other means.

These methods should include:

- selecting appropriate comparators for establishments in female-dominant sectors

- determining ways to raise wage rates to reflect the value of the work performed

- improving the working conditions for female-dominant occupations and consider making binding standards for a given sector

Part 3: Workplace practices

While many workplaces may be progressive in their outlook on gender and supportive of women workers, we heard about experiences where women felt they were being overlooked for promotions, did not receive credit for teamwork with men, or were assigned projects that did not make good use of their skills. Over time, these practices may result in a gender wage gap within an organization.

Many companies and business executives have begun to realize the benefits of openly promoting gender diversity and equality goals.

There are a range of business practices, human resources and compensation policies and systems that may contribute to an organization’s gender wage gap. Some organizations may have sufficient resources or knowledge about these human resource practices. Others may have already introduced measures to address gender wage inequalities. Some may not be aware of the issue. We heard that pay transparency and an analysis of how gender bias may affect women and men are good places to start.

A. Need for pay transparency

Transparency in pay causes institutions and organisations to examine their practices,

“The majority of talent recruitment, development, and management systems aren’t designed to correct wage inequities, nor will ‘giving it time’ even the playing field for women and men. Only intentional actions will close these gaps.”

In the U.S., President Obama issued an executive order

During consultations we heard that some form of pay transparency is necessary. Exactly what and how pay is made transparent can range from employers providing information on pay setting philosophy, policies or procedures, market studies of wage rates, or aggregated pay rates or ranges. Pay transparency is an excellent first step to identifying and correcting other practices that may have an impact on the gender wage gap.

"....mandate employers to collect and share employee data .... gender, employment status (temporary, part time, contract, full-time) and rank. Without this data it is difficult to assess the causes and identify measures that could help mitigate the continuing pay gap.”

"Transparency would be huge. Recent hires are making $5 per hour more than me"

Recommendation 9:

The government should:

- encourage the BPS, Ontario businesses and other organizations to develop pay transparency policies and to share organizational pay information with their employees

- develop and adopt pay transparency policies for the Ontario Public Service (OPS)

- set an example by publicizing information or data on the Ontario Public Service’s compensation or salary ranges by gender

- consider legislation to include protection against reprisal for employees sharing their personal pay information

B. Gender workplace analysis

We heard that many employers do not really know if they have systemic issues related to gender in their organization. Moving beyond pay transparency, many jurisdictions are using gender analytic programs that require businesses to examine their workforce profile, and human resources and employment policies and practices for any unintentional gender biases in:

- hiring and setting starting salaries

- compensation, including bonus-setting

- access to training and promotion opportunities

- participation in decision-making roles

- how employees who take parental and other caregiving leaves are treated

Collecting and analyzing gender-specific statistics are essential to bring awareness to disparities in the workplace. A standardized approach to gender data production, collection and assessment needs to be developed and applied. A gender perspective needs to be incorporated into all aspects of data production, including the forming of gender-relevant variables, collection methods, presentation and distribution.

Once workplace data has been collected, employers and employees can diagnose if there are barriers that are preventing women from fully engaging in the workplace. Employers can then make the necessary changes to remove these barriers.

A range of initiatives has been used: a regulatory approach is used in Australia (Workplace Gender Equality Act, 2012); Switzerland has promoted the use of a self-assessment pay calculator (Logib) and developed an “Equal-salary” public recognition award program. The United Kingdom is moving beyond their voluntary framework (“Think, Act, Report”) to considering a mandatory model requiring the publishing of gender pay gap information.

In Ontario, the Pay Equity Office Wage Gap Pilot project may be instructive, as it dealt broadly with a simple gender workforce analysis.

Recommendation 10:

To help employers identify and take corrective actions to close gender wage gaps in their organizations, the government should immediately consult on and develop a gender workplace analysis tool. It should be simple to use and readily accessible.

- The diagnostic tool should enable employers to collect relevant wage and policy information to examine: gender and diversity recruitment and hiring, starting salaries, family-friendly environments including top-ups for leaves, or flex-time policies, fair promotion processes and bonuses, access to training and leadership opportunities through sponsors or mentors, and gender-balance on boards and at the executive level.

The government should:

- develop resources or guides that define the data to be collected, establish indicators, and assist in tracking and reporting

- implement the tool in the following phases:

- the Ontario Public Service and its agencies, boards and commissions

- The Broader Public Sector

- Distribute the tool to businesses and encourage them to use it.

- conduct a 3-year assessment of its usage and effectiveness at closing organizational gender wage gaps

- based on the 3-year assessment, determine next steps toward achieving gender equality in workplaces including, if necessary, mandatory reporting and action plans.

“Bold, courageous, innovative approaches that challenge, confront and transform systemic practices of discrimination are needed to ensure that women and girls finally share fully and equally in the economic and social wealth of our communities.”

The government should consider:

- building collaborative partnerships with champions of gender workplace diversity and equity and other corporate leaders, municipal partners and key human resource professionals (e.g., Human Resources Professional Association, Ontario Chamber of Commerce) to encourage the use of the tool

- developing a voluntary pledge, public recognition or accreditation program aimed at recognizing employers for applying the tool and making their results public.

“…we often say that things are going to change …if we don’t monitor what is going on, it will fall through the cracks”

C. Women on boards

Women, as leaders, become role models and that may help shift cultural and organizational norms. Currently, women are still under-represented in leadership positions.

Research has found that gender diversity in corporate leadership is linked to improved governance and stronger performance in both financial and non-financial measures. Studies indicate that a critical mass of 30% of women is needed.

Jurisdictions such as Australia, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, Norway, Québec, and Spain have plans or legislation that set targets or quotas for women in leadership.

In Ontario, companies listed on the TSX are now required to report publicly on their efforts to increase the number of women on their boards and in executive officer positions. The “comply or explain” regulation, which came into effect December 2014, resulted in only 15 % of companies adding one or more women to its board in the first year.

Recommendation 11:

The government should require publicly traded companies to ensure diverse representation of women on boards to a minimum of 30%, with appropriate penalties for non-compliance.

Recommendation 12:

The government should examine and report on the gender balance of its appointments to provincial agencies, boards and commissions.

Part 4: Challenging gender stereotypes

It was apparent, during our consultation process, that there was confusion about the gender wage gap. We used the consultation process as an opportunity to make people more aware about the scope of the problem. With a better understanding, participants were able to explore how we could address the many factors that cause the gender wage gap. Stakeholders said public education campaigns are needed to encourage gender equality at home, work, and play.

We also heard that the influence of gender stereotypes starts early in life, at home and at school. Research

A. Raising social awareness

We heard that the province’s recent campaign for “It’s Never Okay: An Action Plan to Stop Sexual Violence and Harassment”

Recommendation 13:

The government should develop a prolonged and sustained social awareness strategy to:

- help people understand the impact of gender bias

- promote gender equality at home, at work and in the community

- increase the public’s understanding of the causes of the gender wage gap and why it is important to close the gap

The government should:

- identify what individuals, business, labour and organizations could do to be a part of the solution

- develop a series of well-targeted messages, informed by current research on gender perceptions and norms

- promote positive images and stories of women and men in a variety of occupations

- look to partner with organizations to develop and deliver a wide range of awareness materials, through appropriate and innovative channels

- evaluate the campaign’s reach and effectiveness

"We live in a time where people recognize unconscious bias - but don’t voice what they see. That has to change so we can turn the culture around.”

B. Education and career development

Education

Schools are an important place for raising awareness about societal issues. Many schools are working to help students understand the importance of accepting differences. Having school teachers and staff reflect the diversity of the school community sends an important equity message to students and parents.

There are many opportunities to teach how gender stereotyping leads to bias, and how bias can affect a lifetime of confidence, attitudes and potential, at home, at school and at work. This anti-bias message can evolve each year, to complement the curriculum of each grade level.

Career development and assessment

We heard that more must be done to ensure young women and men have information about all possible careers as they begin to make choices. Career education and guidance programs can promote well-informed decisions about post-secondary education, skills training or labour markets.

While teachers can influence educational and career choices for young women and men, educators do not regularly do career counselling. Except for co-op teachers, educators are not likely to have strong links to employers. While many guidance counsellors have knowledge of career options, they are more often counselling students on a wide range of issues ranging from course selection to mental health issues.

Therefore, the educational system should involve other partners in the design and delivery of programs on gender equality, career and labour market options.

Recommendation 14:

The government should ensure that all aspects of the education system are free of gender bias.

The government should:

- Work with universities, colleges, teachers’ associations, professional regulatory bodies, school boards and administrators to ensure:

- the primary and secondary school curricula include content on gender bias awareness

- teachers have appropriate resources and training to deliver the content in a gender neutral way

- faculties of education, pre-service teacher training and teachers’ professional development incorporate gender bias awareness into career education programs

- Work with school boards to provide young women and men with career development and experiential learning opportunities in historically male- or female-dominant careers

- Lead the development of partnerships with key local stakeholders such as Parent Involvement Committees or School Councils, local employers or Chambers of Commerce, municipal and regional business and economic development departments, Junior Achievement or other youth organizations to support career education and development

- Assess the degree to which the education system’s workforce reflects the gender and diversity of the community being served; identify and address any barriers in admissions to teacher education programs or in schools’ employment policies and practices.

“If you want women to go into non- traditional roles, men have to [welcome] them.”

C. Expanding skills training opportunities

The occupations and industries where men and women work are still influenced by social norms. As such, gender stereotypes are challenged when women enter into a male-dominant sector or men enter into a female-dominant sector. There appear to be barriers to training for work in occupations historically dominant by either women or men. We heard about lack of information about the variety of jobs available, and active discouragement or harassment. By expanding skills training opportunities, and ensuring they are supportive, more women and men may enter into different sectors, breaking down gender stereotypes that contribute to the gender wage gap.

Recommendation 15:

The government should develop an action plan to support employment and skills training and help increase women’s participation in male-dominant skilled trades and men’s participation in female-dominant ones.

In support of an action plan government could:

- identify opportunities to meet the needs of women and men in employment training services and programs, including pre-apprenticeship training, in historically female or male-dominant sectors

- ensure women are supported by their employers when entering non-traditional fields.

Access to skills training also matters because research has shown a link between highly skilled male-dominant sectors and earnings.

We heard that some graduates from training programs end up in workplaces where they are not welcomed. It appears that in these workplaces, sexism is accepted, or ignored. To support women’s long-term employment, training programs and workplaces must be free of gender-based harassment, discrimination, and bullying.

Recommendation 16:

The government should ensure that employment and skills training programs help women succeed in getting and keeping jobs they are trained for.

This may include:

- providing supports during and after training to assist women if they encounter unwelcoming workplace environments

- working with municipalities and community groups to develop outreach plans to attract women, including women from disadvantaged communities, from the earliest age possible

- continuing bridging programs or other initiatives to assist foreign-trained women professionals become accredited and help them finds jobs in their fields

- measuring the success of program graduates in the workplace, over several years after placement.

Part 5: Other ways government can close the gender wage gap

People told us that leadership from government is vital to closing the gender wage gap. Through its various roles as a direct service provider, law- and public policy-maker, designer and funder of programs and services, and purchaser of goods and services, it can use its authority to show leadership on closing the gender wage gap in the following ways:

A. Perform Gender-Based Analysis

Gender-Based Analysis (GBA) is a tool used to help advance women’s equality in economic, social and civic life by assessing the potential impacts of policies, programs, services, and other initiatives on women and men, taking into account gender as well as other identity factors.

A cross-jurisdictional scan shows that the federal government, all other provinces and the Yukon have published materials or have training on GBA.

However, concerns were raised that GBA is not being conducted in a formal, complete and outcomes-based way. It was not clear that GBA is being applied at the outset of programs or policy development processes when it is important to uncover and correct any hidden gender biases or assumptions. Adding GBA after the fact is often too late to make a difference.

GBA should ideally be applied to all policy, programs and services. When GBA is applied in policies or programs that may appear gender-neutral, such as budgets

To illustrate: Investments in “physical” infrastructure projects support job creation, which is a worthwhile goal. However, most of the direct job creation occurs in industries and jobs that primarily employ men and where wages are higher—e.g., construction, and business, building and other support services.

In contrast, spending restraints in health or social infrastructures can mean fewer jobs or wage freezes for workers in these sectors, the majority of whom are women, and whose work is already known to be undervalued. If these women need to pay for care for a child or an aging relative, they may find themselves without an adequate income to do so. This may compel them to provide unpaid care, at the expense of paid (but undervalued) employment. Without the insights of a GBA on budgets, government decisions to prioritize investments in one area over the other could effectively worsen the gender wage gap.

Stakeholders have called for gender-based analysis across government programs and services, and gender budgeting to help close the gender wage gap. Our recommendation calls for a more consistent and strengthened application of GBA, including its use on key government initiatives already underway.

Recommendation 17:

The government should require all ministries to apply gender-based analysis to the design, development, implementation, and evaluation of all government policies and programs.

This recommendation requires:

- the creation of a tool for all ministries to use, which will ensure GBA is applied from the beginning of any program or policy design process

- an update or development of training workshops, guides and other appropriate tools for staff analysts and other staff

- staff to complete mandatory training

- a way for ministries to assess the impact of using GBA on the success of programs and policies

- the available and consistent collection of data for women and men in all program areas

Recommendation 18:

The government should perform gender responsive budgeting to account for gender effects of public spending and revenues and to redress gender inequalities through the allocation of public investments and resources.

This should involve:

- the development and implementation of gender responsive budgeting tools in internal and external budget processes, to track progress on, and demonstrate the impact of public investments on women and men

- gender-based analysis of taxation policy, including tax cuts, tax expenditures, the use of joint tax or benefit units, and the mix of tax revenue tools, to determine the degree to which they reduce or reinforce gender inequalities through disincentives to work

B. Government contracts and procurement

As a buyer of goods and services, the Ontario government does business with more than 55,000 vendors. Currently, the government’s procurement policy is based on principles of transparency and fairness, geographic neutrality, value for money and responsible management.

The use of procurement policies and contract agreements to meet public policy goals is not new. For example, government’s procurement directive requires contracts and procurements to meet government policies such as having Ontario tax obligations in good standing, and meeting EcoLogo standards and other environmental considerations. The federal government’s Contractors Program ensures that contractors who do business with the Government of Canada achieve and maintain a workforce that is representative of the Canadian workforce.

Several organizations have recommended that the government give priority to companies and organizations that indicate a commitment and actions towards closing the gender wage gap and compliance with human rights obligations, including pay equity, in their organizations.

Recommendation 19:

The government should develop procurement policies that require vendors and suppliers to provide information showing there are no unresolved orders or decisions against them under anti-discrimination laws.

C. Help people access employment standards, pay equity and anti-discrimination laws

There are many laws that affect the workplace (see Appendix 5). We found that workers do not know which law applies to their situation, how to access the complaint process or how to address their issues. We know that workers in precarious employment situations, where many women are found, are afraid of losing their jobs if they make a complaint, even though it is against the law to retaliate against people for exercising their rights. When laws are inaccessible, or are not understood, justice may be denied. We also heard that employers, especially smaller companies, may simply not be aware of their obligations under these laws, or do not know where to seek information so that they can comply.

Recommendation 20:

To help people resolve gender workplace issues involving employment, compensation, or discrimination, the government should consider how to ensure employees understand their rights and obligations, and how to access justice.

Some suggestions include:

- developing easily available educational materials for employees and ensuring they receive the information

- providing employers with an integrated package of training materials on anti-discrimination legislation

- providing assistance during the complaint process, or making appropriate referrals

Challenges and next steps

As the causes of the gender wage gap are complex, so too are its solutions. Our recommendations tackle as many of the key issues as possible, given the time and resources available. This report notes many of the activities undertaken by government and organizations over the years, to address various aspects of this issue.

This section identifies some of the challenges we encountered, and points to further opportunities for consultation and analysis. It also provides an overview of important issues we heard about in the consultation, but which were outside our mandate, or being addressed through other forums.

Data availability

In our consultations, we found that many organizations, public and private, could not provide gender-based data. We were told that this is because it is not required, as data for other intersectionalities, such as age, race or disability may be. This lack of data affects our ability to have informed discussions about the extent of the gap. It is difficult to assess how the gender wage gap may be affected by regional economies or in different sectors, for example. That is why the collection of data is seen as crucial in this report, and there are recommendations to address it.

Collecting and analyzing gender-specific statistics is essential to bring awareness to disparities. Gender-specific data would also enable comparisons of experiences across workplaces, programs or jurisdictions. A standardized approach, aligned with a global statistical system, needs to be developed and applied. This approach should inform all aspects of gender data production, collection and assessment, including data on a range of gender identities, gender-relevant variables, and how to present and distribute the data.

We also heard about the importance of employment equity. That feedback is reflected in our recommendations about pay transparency and gender workplace analysis, as employment equity can be assisted by these tools.

Intersectionalities

Many of our recommendations, if implemented, address issues of concern to almost everyone: the provision of child and elder care, addressing gender bias at school and work, and raising social awareness. However, women with disabilities, Aboriginal and racialized women are more likely to face compounding employment disadvantage and wage inequality.

Closing the gender wage gap for specific groups, including these, will require further investigation, focused strategies and culturally appropriate measures and tools. Aboriginal women experience a gender wage gap that is larger than the provincial average (see Appendix 3). Aboriginal Peoples also face significant education and employment gaps.

The City for All Women Initiative has created Advancing Equity and Inclusion: A Guide for Municipalities. This document is a useful tool as it recognizes that women and girls face specific inequities, and have important contributions to make to city life, especially if they are racialized, Aboriginal, LGBTQ, newcomers, older adults, young, living with a disability, or living in poverty.

Other government initiatives

Aspects of a gender wage gap strategy are also within the scope of other ongoing government reviews. The Changing Workplaces Review, for example, is considering such key issues as:

- paid personal leaves;

- pay parity among workers, whether part-time, full-time, temporary or permanent;

- workers’ scheduling;

- unionization; and,

- broader based sectoral bargaining.

These issues were identified by many participants as important to address barriers facing women at work, especially for unrepresented women who do not exercise workplace rights for fear of job loss or other reprisal and have less ability to organize, unionize or negotiate workplace standards.

Similarly, under the Poverty Reduction Strategy, the design and implementation of a basic income pilot

- enable women and men’s economic autonomy,

- meet the needs of children and give women and men more options to better balance work and caregiving demands.

We encourage the government to continue to consider how these reviews work together, and to assess how best to develop strategies and implement recommendations. We recommend that any action arising from other strategies that affect the gender wage gap be examined to ensure that they do not contribute to widening the gap. Above all, we would like to see progress on closing the gender wage gap. Coordination and alignment is necessary to achieve that.

Other issues raised

During the consultations, we also heard about the importance of issues that relate more broadly to women and work, including minimum or living wage, and card-based certification. We also heard from two professional groups, midwives and principals, who have specific issues related to the valuation of their work. They raised valuable concepts that have resonated in this report; however, their specific issues may more properly be addressed through other means.

We also heard from many women who said they were the targets of unacceptable behaviours at work. We acknowledge that Ontario has recently introduced changes to address issues of sexual violence and harassment in the workplace.

Conclusion

This report is a call to action.

The Ontario government tasked the Steering Committee with developing recommendations for a wage gap strategy to close the gap between women and men in the context of the 21st century economy. The economic imperative has been central to the discussion and analysis. We consulted extensively on a wide range of issues affecting employment, earnings and economic outcomes in Ontario. Research on women, families, work and organizations in other provincial and international jurisdictions also supported our deliberations.

In this report, we assess ways in which all levels of government, business, labour, other organizations, and individual leaders can work together to address the conditions and the systemic barriers that contribute to the wage gap. It was an honour to serve on this project. In turning our findings over to government to develop Ontario’s first coordinated gender wage gap strategy, we note the following:

Of necessity, government will have to lead many of these recommendations, but this is not a strategy that can be accomplished by government alone.

There is much that employers can do immediately:

- Publicly commit to:

- close gender wage gaps in their organizations, and begin to take corrective action

- create respectful workplaces, free of violence and harassment and

- show leadership in promoting pay transparency

Business and Professional Associations can assist their members to find ways to address gender bias by sharing best practices, encouraging compliance with relevant laws and publicly recognizing “good actors.”

Sectoral Associations can use their resources to collect and disseminate information about male and female participation and wage distribution within the sector, broken down by gender.