Income Security: A Roadmap for Change

Read the report and recommendations submitted to the government by the:

- Income Security Reform Working Group

- First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group

- Urban Indigenous Table on Income Security Reform

Executive Summary

Ontario’s income security system

We have seen the human toll caused by inadequacies in the current system, including the deprivation, despair and lost opportunities for individuals and families living in poverty. Higher health care, social service and justice system costs and lower tax revenues follow as a reminder of the poor outcomes people are experiencing. The bottom line is that poverty is expensive and it costs us all.

Many previous reports have documented the problems in Ontario’s income security system; now it is time for action. That is why three Working Groups

The purpose of this Roadmap is to identify a clear path forward, one that sets out concrete steps over multiple years with the goal being a modern, responsive and effective system.

Income Security: Future State

Figure 1 Social and Economic Inclusion

"All individuals are treated with respect and dignity and are inspired and equipped to reach their full potential. People have equitable access to a comprehensive and accountable system of income and in-kind support that provides an adequate level of financial assistance and promotes economic and social inclusion, with particular attention to the needs and experience of Indigenous peoples."

Overarching Themes

In developing the Roadmap, the Working Groups were compelled by three overarching themes:

- Investing in People – People are Ontario’s most important resource. All elements of the income security system need to work effectively together to meet a diverse range of needs and experiences, in support of better financial stability, health and well-being for all individuals and families. People’s interactions with the income security system are too often focussed on transactional activities and the enforcement of rules, particularly within social assistance. There is a critical need to change the way in which programs are designed, how they intersect, and how they connect people to relevant support from the very first point of contact.

- Addressing Adequacy – It is unacceptable that so many people live in deep poverty and critical need in Ontario. It is vital that the Province establish and commit to a floor below which no one should fall. Success requires that all parts of the income security system, a mix of federal, provincial and municipal income supports and benefits, work together to improve people’s lives. Urgent and immediate action and significant investments are required in the income security system, including social assistance, to make this a reality over the next 10 years.

- Recognizing the Experience of Indigenous Peoples – Income security reform must support the Province’s commitments to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples through its Journey Together framework, and help rebuild relationships with Indigenous peoples. This will require the income security system to actively address and guard against systemic and institutional racism and recognize the profound impact of colonization, residential schools and intergenerational trauma. Reform must respect First Nations’ right to self-governance and respond to the unique needs and perspectives of all Indigenous peoples, including those who are not members of a First Nation. Due to challenges related to data collection both within and outside of First Nations communities, it is difficult to accurately ascertain the number of Indigenous peoples who live in towns and cities across the province. One source is an Ontario Ministry of Finance document, 2011 National Household Survey Highlights: Aboriginal Peoples of Ontario, that uses federal data to cite that about 84%

footnote 3 of Indigenous people live outside of First Nations communities. First Nations note this information is skewed as many First Nations people do not participate in the data collection/survey.

Summary Of Recommendations

Achieving Income Adequacy

Adopt a definition of income adequacy and make a public commitment to achieve that goal over 10 years.

1. Adopt a Minimum Income Standard in Ontario to be achieved over the next 10 years through a combination of supports across the income security system.

- The Province should publicly commit to a Minimum Income Standard that will be achieved over a 10-year period (by 2027–28).

- The Minimum Income Standard should initially be established at the Low- Income Measure (LIM) currently used by Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy (i.e., PRS LIM-50 linked to a base year of 2012), plus an additional 30% for persons with a disability, in recognition of the additional cost of living with a disability. See Appendix B for the PRS LIM levels for different family size.

- Begin work immediately to define a made-in-Ontario Market Basket Measure (MBM) that would include a modern basket of goods, with prices reflecting true costs, and adjusted for all regions in the province, including the remote north. The measure would be used in evaluating progress towards the Minimum Income Standard and potentially revising or replacing the PRS LIM as the measure used to set the standard. The made-in-Ontario Market Basket Measure could also be used to guide and evaluate investment decisions over the long-term.

- Implement the recommendations in the Roadmap to move toward adequacy in the income security system by 2027–28.

Engaging The Whole Income Security System

Leverage the whole income security system, current and future, so that programs work together to help all low-income people achieve social and economic inclusion.

Ontario Housing Benefit

2. Introduce a housing benefit to assist all low-income people with the high cost of housing, whether or not they receive social assistance, so they are not forced to choose between a home and other necessities.

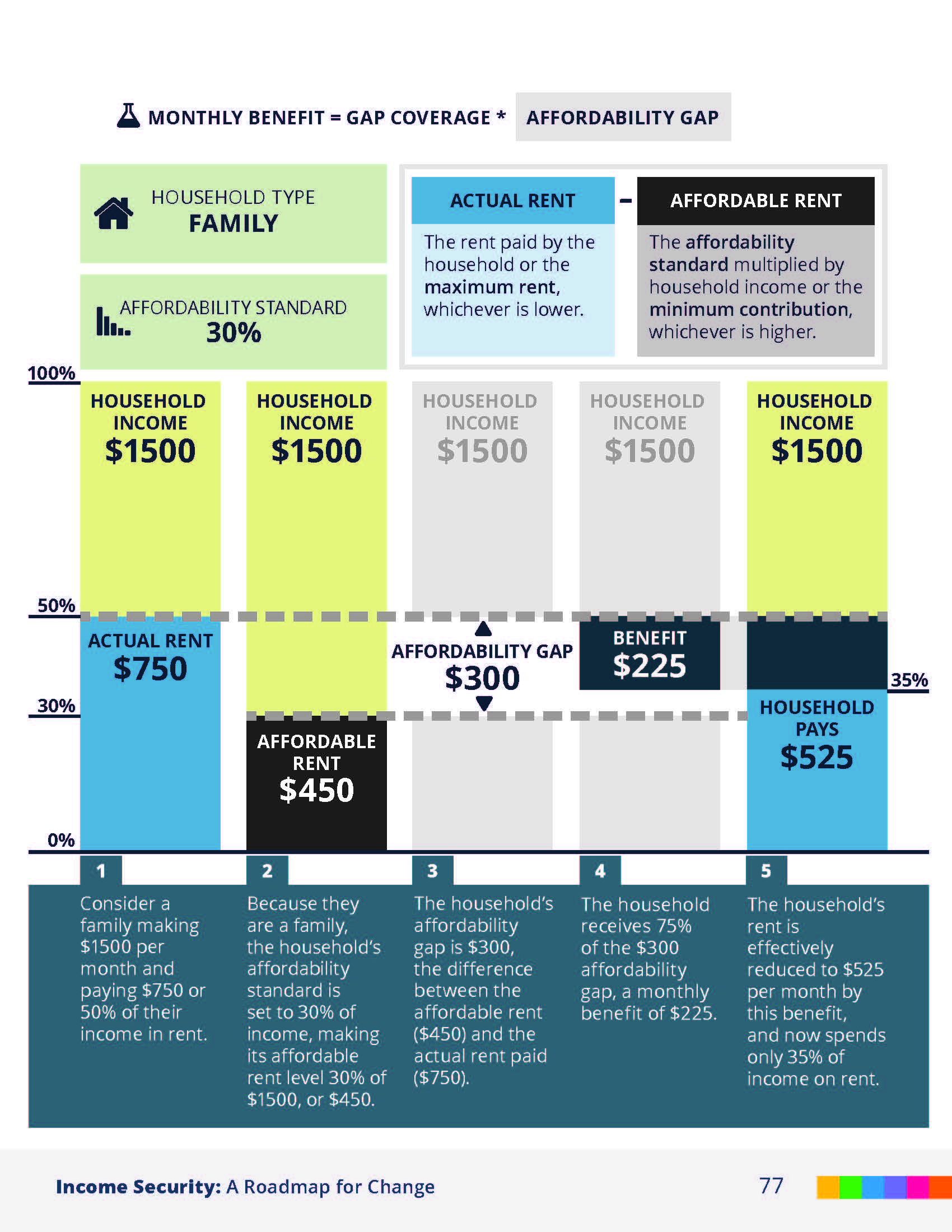

- Confirm the design and implementation details for a universal, income-tested portable housing benefit for people who rent their homes.

- Implement the portable housing benefit in 2019–20 at a modest “gap coverage” of 25% with the gap defined as the difference between the actual cost of housing and a minimum household contribution given household income.

- Increase gap coverage to 35% in 2020–21 and continue to increase gap coverage, reaching 75% by or before 2027–28.

- First Nations need to be meaningfully included in the housing benefit and may need modifications or an alternate benefit to ensure it works in the reserve context.

Income Support For Children

3. Continue to move income support for children outside of social assistance so all low-income families can benefit fully, regardless of income source. Ensure supports are sensitive to the needs of children and youth who are experiencing difficulties in their family life.

- Provide bridging child supplements within social assistance to ensure families are not worse off during the transition, as the social assistance structure is transformed to include flat rates.

- Re-brand the Temporary Care Assistance program to focus on child well being, increase the amount of income support provided to better align with foster care levels, and provide clear flexibility for Ontario Works Administrators to determine where it is best accessed.

- Shift the remaining amounts paid in respect of children’s essential needs in social assistance to the Ontario Child Benefit as a supplement targeted to the lowest-income families.

- Require Children’s Aid Societies to place Children’s Special Allowance payments into a savings program for youth in care 15 years and older so the funds can be disbursed to youth when transitioning from care.

- Provide support to all low-income people, including those living in First Nations communities, to ensure that benefits paid through the tax system are accessed and equitably received.

Working Income Tax Benefit

4. Work with the federal government to enhance the effectiveness of the Working Income Tax Benefit (WITB) so that it plays a greater role in contributing to income adequacy for low-income workers in Ontario.

- The federal government enhance the WITB so that it better reflects the realities faced by low-income workers in Ontario. This should include examining:

- The level of earnings at which an individual begins receiving the WITB and how the WITB is adjusted when earnings increase, including the threshold at which the WITB begins to be reduced

- The overall amount of support provided through the WITB

- The net income at which individuals are no longer eligible to receive the WITB

- Outreach, support and any alternative delivery required to ensure that the WITB is accessible to First Nations individuals

Core Health Benefits

5. Make essential health benefits available to all low-income people, beginning with ensuring those in deepest poverty have access to the services they need.

- Expand access to mandatory core health benefits to all adults receiving Ontario Works and adult children in families receiving ODSP, and add coverage for dentures (including initial and follow-up fittings) for all social assistance recipients.

- Expand existing and introduce new core health benefits for all low-income adults over the next 10 years starting with the expansion of prescription drug coverage to adults 25 to 65, followed by:

- Expanding Healthy Smiles Ontario to adults age 18 to 65 and adding dentures as part of the benefit

- Designing and implementing a new vision and hearing benefit for low-income individuals and families

- Expanding access to medical transportation benefits

- Review the Assistive Devices Program to ensure the program is maximizing its reach to low-income people, both in terms of the list of devices that are covered and the maximum coverage.

Access To Justice

6. Procedural fairness should be embedded in all aspects of the income security system through adequate policies, procedures, practices and timely appeal mechanisms.

- Request a research body such as the Law Commission of Ontario or an academic institution review the existing appeal process for tax-delivered benefits and develop recommendations for enhanced or new mechanisms that support fair, transparent and efficient access to those benefits and appeal processes.

Transforming Social Assistance

Make social assistance simpler and eliminate coercive rules and policies. Create an explicit focus on helping people overcome barriers to moving out of poverty and participating in society.

Legislative Framework

7. Fundamentally change the legislative framework for social assistance programs to set the foundation for a culture of trust, collaboration and problem-solving.

- Develop and introduce new legislation to govern and rebrand the current Ontario Works program. As a starting point for legislative change, draft and publicly consult on a new purpose statement in the first year of reform that explicitly recognizes and supports:

- Individual choice and well-being

- Diverse needs and a goal of social and economic inclusion for all

- Identify and amend regulations under both the Ontario Works Act and the Ontario Disability Support Program Act, before new Ontario Works legislation is introduced, in order to jump-start and reinforce a positive culture of trust, collaboration and problem-solving.

- Provide First Nations with the opportunity to develop and implement their own community-based models of Income Assistance under provincial legislation.

A Culture Of Trust, Collaboration And Problem-Solving

8. Introduce an approach to serving people receiving Ontario Works and ODSP that promotes a culture of trust, collaboration and problem-solving as a priority, and supports good quality of life outcomes for people in all communities, including Indigenous peoples.

- Position front-line workers as case collaborators whose primary role is to act as supportive problem-solvers and human services navigators in a way that allows people to share information without fear of reprisals. This includes working with individuals in both individual and group settings.

- Introduce a comprehensive assessment tool to identify needs for, and barriers to, social and economic inclusion that uses an equity- and trauma-informed approach to connect people to appropriate supports.

- Use pilots to test the comprehensive assessment tool and the collaborator role with an initial focus on people seeking to access ODSP through Ontario Works, long-term social assistance recipients, youth and persons with disabilities.

- Eliminate financial penalties related to employment efforts and rigid reporting requirements to support a new person-centred approach, promote trust and respect between front-line workers and people accessing help, and place a firm emphasis on problem-solving and addressing urgent needs first (e.g., risk of homelessness). This includes revising policies that create barriers to safety and well-being (e.g., fleeing an unsafe home).

- Ensure front-line workers have the necessary skills and knowledge to act as case collaborators through:

- Mandatory professional development and learning, including skills in social work (i.e., anti-racism, contemporary professional development and anti-oppressive practice), and Indigenous cultural safety and awareness training

- Provincially set and governed quality standards and controls tied to staff performance plans

- Regularly situate Ontario Works and ODSP case collaborators in Indigenous service delivery offices to improve cultural awareness and understanding and support better inter-agency relationships.

- Clearly recognize Indigenous peoples’ right to choose service in their preferred location.

- Ensure staffing at all levels reflects the diversity of Ontario, and model truly inclusive offices that are welcoming spaces and reflect the multitude of cultures and communities served across the province, including the diversity within and across Indigenous communities.

- Continuously review and adjust the service approach, professional development, and tools and resources based on feedback from partners and people accessing programs.

- Establish a First Nations–developed and implemented program based on self-identification, self-worth and true reconciliation leading to life stabilization.

- Conduct analyses on current and proposed policies and services to ensure they do not increase vulnerability or undermine safety of those receiving support. This should include a culture- and gender-based analysis to ensure the safety of Indigenous women.

Supporting People With Disabilities

9. Maintain and strengthen ODSP as a distinct program for people with disabilities. Ensure that both ODSP and Ontario Works are well equipped to support people with disabilities with meeting individual goals for social and economic inclusion.

- Recognize the continued need for a distinct income support program for people with disabilities.

- Retain the current ODSP definition of disability.

- Continue work with the Disability Adjudication Working Group to streamline and improve the ODSP application and adjudication process.

- Provide provincial-level assistance and accommodation for people who need help with the ODSP application process, building on lessons learned from community groups.

- Include specific review with First Nations and urban Indigenous service delivery partners to ensure that the assistance and accommodation reflect the unique experience of Indigenous peoples.

- Ensure that both ODSP and Ontario Works accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities as part of the person-centred, collaborative approach to support individual goals and aspirations.

An Assured Income Approach For People With Disabilities

10. Co-design an “assured income” approach for people with disabilities.

- Co-design an assured income mechanism for delivering financial support to people who meet the ODSP definition of disability. Consultation with First Nations people is essential.

- Include the following features in the assured income mechanism:

- Income-tested only (i.e., no asset test)

- Stacking of income benefits to reach adequacy

- Tax-based definition of income (i.e., does not include financial help (gifts) from family or friends)

- Continued responsibility of the provincial government to determine disability, with the right of appeal to the Ontario Social Benefits Tribunal

- Flexibility to adjust to in-year income changes

- Safe to move into employment and back to the program

- Provide an initial assured income at least as high as the ODSP Standard Flat Rate – Disability at the time of transition, and provide continued increases until the Minimum Income Standard is achieved in combination with other income security components.

- Ensure that people receiving the assured income have full access to ODSP caseworker services and support.

- Provide First Nations with the ability to administer and deliver ODSP in their own communities in the same manner as Ontario Works.

A Transformed Social Assistance Structure

11. Redesign the social assistance rate structure so that all adults have access to a consistent level of support regardless of living situation (i.e., rental, ownership, board and lodge, no fixed address, rent-geared-to-income housing, government-funded facility).

- Transform the social assistance rate structure so that:

- Single adults receive a Standard Flat Rate that does not distinguish between basic needs and shelter

- Couples receive a Standard Couple Flat Rate equal to 1.5 of the Standard Flat Rate

- In recognition of the additional cost of living with a disability, single adults with a disability receive a higher Standard Flat Rate – Disability and couples receive a Standard Couple Rate - Disability of 1.5 of the Standard Flat Rate – Disability. Adult children aged 18 to 24 (without a disability) who live with their parent(s) on social assistance receive a Dependent Rate (75% of the Standard Flat Rate for the first dependent and 35% for each subsequent dependent). Adult children over age 24 (without a disability) who live with their parent(s) receive the full Standard Flat Rate. People with disabilities will continue to qualify in their own right for ODSP at the age of 18

- Align the definition of spouse under social assistance with the Family Law Act (i.e., deemed a spouse after three years).

- In moving to a Standard Flat Rate structure, eliminate the rent scales currently used for those receiving social assistance. Require municipal housing services managers to invest the increased revenues resulting from the elimination of rent- geared-to-income rent scales (due to the transformed rate structure) into local housing and homelessness priorities.

12. Improve social assistance rules and redesign benefits to make it easier for people to pursue their employment goals and realize the benefits of working.

- Redesign, using a co-design process, existing employment-related benefits (except the ODSP Work-Related Benefit) into one benefit, with consideration given to whether the new benefit should be mandatory or discretionary, the level of prescription in the activities the benefit can support, and the level of support that is provided to meet a broad range of needs. Test the new benefit before province-wide roll out.

- Reduce the wait period for exempting employment earnings to one month (from three months) in Ontario Works.

- Designate First Nations Ontario Works delivery agents to deliver and administer the Employment Ontario employment assistance program to better assist their community members in becoming employable through the array of programming and benefits that are not available to them for a variety of reasons, including but not limited to vast distances from municipalities or urban centres where Employment Ontario programs are placed, lack of services focussed on developing employability skills available through the Ontario Works program, and the recent removal of assisting programs (e.g., First Nations Job Fund).

- Support case collaboration in both individual and group settings.

13. Modernize income and asset rules so people can maximize the income sources available to them and save for the future.

- Exempt as assets funds held in Tax-Free Savings Accounts and all forms of Registered Retirement Savings Plans so people do not have to deplete resources meant for their senior years.

- Initially exempt 25% of Canada Pension Plan - Disability, Employment Insurance and Workplace Safety and Insurance Board payments from social assistance (i.e., social assistance would be reduced by 75 cents for every dollar of income from these sources rather than dollar for dollar).

- Increase the income exemption for Canada Pension Plan - Disability, Employment Insurance and Workplace Safety and Insurance Board payments to the same level as the existing earnings exemption by 2022–23.

14. Ensure ongoing access to targeted allowances and benefits until such time as adequacy is achieved. Determine which extraordinary costs remain beyond the means of individuals even when adequacy is achieved and maintain those benefits.

- Retain the following special purpose allowances/benefits and review as progress towards adequacy is made and people’s outcomes are better understood:

- Special Diet Allowance

- Mandatory Special Necessities/Medical Transportation

- Pregnancy and Breast-Feeding Nutritional Allowance

- ODSP Work-Related Benefit

- Revise medical transportation rules to include and support improved access to traditional healers.

- Review and introduce expanded eligibility criteria for the Remote Communities Allowance to better address the needs of northern and remote communities.

- Redesign Ontario Works discretionary benefits as other recommendations are implemented (e.g., making core health benefits and help with funeral and burial costs mandatory) and consider making them available to the broader low-income population.

Helping Those In Deepest Poverty

Take early, urgent steps to increase the level of incomed support available to people living in deepest poverty.

15. Help those in deepest poverty by immediately increasing the income support available through social assistance as a readily available means for early and absolutely critical progress towards adequacy.

- Implement changes that make meaningful progress in improving the incomes of those furthest from the Minimum Income Standard through social assistance as the most readily available and easily adjusted means by (in Fall 2018):

- Setting the Standard Flat Rate at $794/month (a 10% increase over Fall 2017 Ontario Works maximum basic needs and shelter rates)

- Setting the Standard Flat Rate – Disability at $1,209/month (a 5% increase over Fall 2017 ODSP maximum basic needs and shelter rates)

- Implement increases to the Standard Flat Rate and Standard Flat Rate – Disability in Fall 2019:

- Increase the Standard Flat Rate to $850/month (7% increase over Year 1)

- Increase the Standard Flat Rate – Disability to $1,270/month (5% increase over Year 1)

- Implement further increases to the Standard Flat Rate and Standard Flat Rate – Disability in Fall 2020:

- Increase the Standard Flat Rate to $893/month (5% increase over Year 2)

- Increase the Standard Flat Rate – Disability to $1,334/month (5% increase over Year 2)

- Continue to raise the level of income support available through a (rebranded) Ontario Works program until the Minimum Income Standard is achieved in combination with other income security components by 2027–28.

Self-Governance And Respect For First Nations Jurisdiction

16. Take steps to ensure that social services are ultimately controlled by, determined by and specific to First Nations.

- Based on First Nations' inherent right, First Nations should have the opportunity to develop and control their own social service programs.

- Recognize First Nations’ authority to create and implement their own model of Income Assistance.

- Engage with federal government and First Nations in a tripartite arrangement to ensure ongoing financial support for the new flexible, responsive approaches.

- Respect First Nations' autonomy and work with First Nations to develop an opt-out clause that explicitly recognizes their right to opt out of provisions in the Ontario Works legislative framework in favour of their own models.

- Establish communication processes for informing First Nations of the opt-out provisions and opportunities for piloting direct program delivery.

- Identify more flexible, responsive service approaches or models that First Nations could adapt, such as:

- Living with Parent rule

- Qualifying period for earnings exemptions

- Non-compliance rules

- Rental Income for Ontario Works recipients

- Spousal definition to be defined under the Family Law Act

- Participation requirements (voluntary)

- Shelter cost maximums, to be based on actuals

- Establish and communicate clear guidelines for provincial staff in accessing First Nations–owned data reflecting the principles of the Ownership, Control, Access and Possession protocol endorsed by the Assembly of First Nations.

- Commit to working with First Nations to design and launch pilots for the direct delivery of programs including the Ontario Disability Support Program, Employment Ontario, Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities and Special Services at Home within their communities, with the long-term goal of First Nations delivery as they choose.

- Support the development of administrative forms and processes and training of First Nations social services staff to support the new flexible, responsive approach.

- Commit to working with First Nations (through Provincial Territorial Organizations (PTOs), Tribal Councils or individual First Nations) to establish an implementation plan for First Nations to accept the responsibility for the design and delivery of the following programs to First Nations communities: Ontario Works, Ontario Disability Support Program, Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities, Special Services at Home, and Temporary Care Assistance.

- Take steps to ensure that First Nations will still be eligible for any new program dollars for any new programs that the Ontario government might develop after a First Nation has taken on self-governance in social assistance.

17. Broaden program outcomes to encompass social inclusion. Simplify processes and provide tools for a more holistic, individualized approach that offers wrap-around services.

- The diverse goals, needs and paths of individuals should be recognized to encourage and promote personal success. This includes broadening program outcomes to include community engagement and social inclusion, as well as supporting individuals in increasing their employability.

- First Nations social service programs should have recognition and support for their ability to provide:

- Income assistance to singles, couples and families

- Pre-employment activities that include but are not limited to literacy, upgrading, employment experience, job-specific skills training, youth- specific initiatives, social enterprise and self-employment resources

- Mental health and addictions referrals and early interventions

- Community-based initiatives specific to language, culture, tradition and the community’s economic and educational context

- All of these services will be delivered in a First Nations holistic approach

- Community and social development training for First Nations staff.

- Healing and wellness, life stabilization, social inclusion, pre-employment activities and developing essential skills should be recognized as significant achievements along the path to success.

- Ontario Works self-employment rules should be aligned with ODSP to include those working part-time and seasonally. Self-employment rules, guidelines and eligibility assessments should be simplified and revised.

- Encourage self-employment and social enterprises as viable options for First Nations peoples and communities.

- Work with First Nations to promote information and create opportunities related to micro-loan availability and small business start-up, as well as federal and provincial programming.

- First Nations Social Service administrators should continue to deliver employment-related services to promote a holistic approach towards supporting community members.

- First Nations Social Service administrators should deliver and oversee Employment Ontario employment services and supports in their communities.

- First Nations youth represent the future of First Nations communities and require access to services and supports earlier in life to achieve success in employment, education and transitioning to adulthood.

- Young people aged 14+ should have access to Ontario Works and ODSP employment supports

- Provision of funding to support programming, social inclusion, cultural learning and knowledge-sharing between Elders and youth

- In recognition that ODSP should be delivered by First Nations, reduce barriers to ODSP by:

- Funding support staff to provide intensive case management and secure assessments to help individuals navigate ODSP

- Supporting better access to health practitioners in First Nations communities to assist with the completion of the Disability Determination Package (DDP) through use of video or telehealth services

- Increasing and expediting help with medical transportation costs

- Ongoing supports for ODSP recipients and benefit units

- Providing a supplementary benefit that is dedicated to individuals with disabilities receiving ODSP

- Providing longer timelines to complete steps in the adjudication process as required

- To support ongoing professional development for First Nations, tools, resources, funding and training should be in place.

- Promote/support healing and wellness among social services staff.

- The capabilities, skills and professional development of First Nations Social Service administrators should be better recognized and celebrated as critical to affecting the lives and outcomes of First Nations individuals receiving social assistance.

Adequate Funding For First Nations

The income security system needs to better respond to the local economic and geographic circumstances of First Nations communities to help ensure people get the help they need to maintain an adequate standard of living and are lifted out of poverty.

- Programs, services and supports provided through social assistance should better reflect the realities of living within First Nations communities.

- Discretionary funding should be based on reimbursement of actual expenditures.

- Rates should reflect the additional costs of living in First Nations communities, including remote and isolated communities (e.g., purchasing nutritious food, transportation costs).

- Address price-setting practices for food, goods and services in northern communities (e.g., Northern Store).

- Expand eligibility criteria for the Remote Communities Allowance to include a wider area.

- Recognize and apply the concept of using a First Nations-developed Remoteness Quotient that reflects the increased cost of living in remote First Nations.

- Develop a Transitional Support Fund (TSF) funding formula that is based on actual expenditures.

- Provide additional funding to support the Cost of Administration (COA), especially for communities with smaller caseloads.

- Develop a supplementary case load tool and technology that accurately captures the actual case load data and is reflected in the COA and discretionary benefits.

- Fund First Nations technology solutions.

Implementing And Measuring Change

18. Income security reform must be accompanied by a robust change management and implementation plan.

Reporting On Progress

Implementation of this Roadmap should be accompanied by a transparent report on associated outcomes and indicators, to be updated annually and made publicly available by the Province.

- Establish an annual, publicly available report that will outline progress on the Roadmap recommendations, including progress against outcomes.

- Establish a third-party body to review and comment on the annual progress report and provide comments to the Cabinet.

- Require that both the annual report and the third-party comments be tabled in the Legislature.

Sequencing Reform

The Roadmap recommends a package of tangible changes and improvements to Ontario’s income security system so that it better supports the diversity of people who use it, and outlines the sequencing of reforms over 10 years.

Items are sequenced over time to allow for critical co-design processes and so that lessons learned earlier in implementation can inform later stages and fiscal realities. Efforts have also been concentrated on key actions in the first three years that are critical to building momentum, targeting those in most urgent need, and establishing important foundations for change. The recommended changes are not stand-alone, nor should they be viewed as a menu of options.

Implementing the Roadmap will require further work to define the details and create plans on how changes are introduced. As noted above, it is important that the Province involve a broad range of voices in a co-design approach for certain critical elements, including people impacted by change, front-line workers, service managers and delivery partners, advocates, Indigenous peoples and organizations, and a range of other experts. It is also important that opportunities to test or pilot change be taken, so that lessons can be learned and adjustments can be made prior to broad implementation. It is critical that pilots are inclusive of the diversity of the community so any differential impact on uptake and outcomes can be evaluated and used to inform the final design and rollout. This means ensuring an intentional diversity of participants, including but not limited to racialized individuals, persons with disabilities, Indigenous people, women, communities negatively impacted by heterosexism, homophobia and transphobia, and newcomers to Canada.

The full participation of the federal government is needed if low-income individuals and families are to achieve their potential and reach an adequate income. The federal government is also called upon to work directly with First Nations in a nation-to-nation capacity to address significant physical and social infrastructure deficits in First Nations communities.

Our Voices – A Word From The Working Groups

Message From The Income Security Reform Working Group

We come from different walks of life, personally and professionally, and we hold shared values and beliefs about the need for fundamental change and investment in the income security system. We believe that the system must do a better job of helping people escape poverty and low income to improve their lives. In that spirit, we worked together over the past year, at the government’s invitation, to develop a 10-year roadmap for income security reform in Ontario.

We realized early on that mere tweaking of the system was not an option. The Roadmap described in this report is intended to be transformational, both inside and outside social assistance. It recognizes the changing world of work and the growing number of people who struggle to make ends meet. It recognizes that people from some groups are more likely to be affected by poverty than others. It recommends ways to more effectively support the people who access the income security system, whether for long or short durations, strategies to achieve income adequacy in the long term, and immediate changes to help people in deepest poverty.

Implementation of the Roadmap on its own will not eradicate poverty in Ontario. But it will improve the lives of low-income people, many of whom wake up every day wondering where their next meal will come from or if they will have a roof over their heads. The transformation we envision can only succeed if government works actively with partners, including those directly affected by the system, to design and implement the key elements of change.

We recommend the Province commit to a Minimum Income Standard and move steadily towards that goal over the next ten years. We have recommended, among other things, the early implementation of changes to address the insufficient levels of support for single individuals receiving Ontario Works and the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP)—people who have fallen far behind over the past 20 years. We struggled with the pace at which government should bring all people out of deepest poverty, since the gap between where they are and where they need to be is so large. The reforms we have recommended in the first few years are what we see as the minimum first steps towards a more adequate system of low-income supports for working-age adults. They also introduce new foundational elements to the broader income security system, such as a portable housing benefit.

The government asked us and two other working groups to create a Roadmap, with support from staff of the Ministry of Community and Social Services. We have done what we were asked to do. In turn, we urge the Province to embrace the vision we have proposed, to dedicate sufficient funding to implement the Roadmap, and to seriously consider moving even more quickly to achieve income adequacy. We also call on all other levels of government to take an active role.

We are proud of the Roadmap that we helped to create. We put it forward in the firm belief that everyone, especially those who have suffered the most from living in poverty, should have the opportunity to live without scarcity and fear, to fulfill their potential, and to contribute to their own growth and the prosperity of all our communities.

Message From The First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group

The First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group has welcomed the opportunity to contribute to the thinking represented in this Roadmap for Change, an opportunity that has been a long time coming for First Nations. In 1991, shortly after the publication of “Transitions,” a late-80s review of the social assistance system, Ontario First Nations passed Resolution 91/34, which set out principles for developing social services determined by, controlled by, and specific to First Nations, as previously recommended in the Transitions report. This recommendation was also recognized in the Brighter Prospects: Transforming Social Assistance in Ontario report (Lankin, Sheikh 2012) and aligns with the 1996 Royal Commission on Aboriginal People Report. Resolution 91/34 highlighted First Nations’ expectation that federal and provincial governments would recognize these principles and support flexible approaches to First Nations self-determined social services through legislative exemptions, alternative financial arrangements and other options.

In the short timeframe of six months, 10 meetings have occurred on the traditional territory of the Mississaugas of the New Credit.

There were few real platforms for First Nations–provincial dialogue on social reform until the 2015 Political Accord signed by the Premier and Ontario First Nations, which committed the Province and First Nations to a formal government to-government relationship framed by the recognition of First Nations Treaties.

2015 also saw a commitment by the federal government to implement the United Nations (UN) Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The UN Declaration sets out individual and collective Indigenous rights such as the right to be actively involved in developing and determining health and social programs and, as far as possible, to administer such programs through Indigenous institutions. The Declaration also recognizes that Indigenous people have the right to free, prior and informed consent before adopting and implementing legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. Following the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation commission, the Ontario government in 2016 announced a formal commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, called The Journey Together.

Within the context of these unique rights and relationships, the First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group has shared insights regarding the impacts of residential schools, the extent of the intergenerational trauma and poverty that exists in First Nations communities, and the need for social assistance programming that develops First Nations’ capacity to overcome these challenges. Within our First Nations, we are aware of the depth of despair, hopelessness and isolation. We or someone we know and love are living everyday with the effects of poverty. Those effects include food insecurity, poor housing conditions, low literacy levels, high drop-out rates in education, over-representation in the justice system, under-representation in programs we qualify for but that are hard to access such as ODSP and Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities (ACSD), high costs of living in isolated and remote areas, losses in control and access to our traditional territories and natural resources, lack of economic development (which has been affected by colonization, including Indian Act policy and its restrictions on reserve land use), lack of infrastructure (including internet services), overcrowding, high unemployment rate, underfunding, low wages and lack of adequate job opportunities.

First Nations community dependence on the social assistance system has become entrenched over generations. First Nations social assistance recipients are among the most vulnerable people in Ontario. They require in-depth supports to build hope and self-esteem and acquire the skills to set goals and overcome barriers related to mental health, addictions and family crisis, which will enable them to become resilient and self-sufficient. First Nations also need support at the whole community level to build opportunities for economic development and education and promote healing. As Ontario contemplates a new direction for income security, First Nations have flagged the key concept of social inclusion given the limited opportunities for employment, education and healing in First Nations communities. Income security reform should ensure that social assistance programming enhances individuals’ and families’ lives along their journey towards employment, or towards social engagement when employment is not realistic.

An effective income security approach in First Nations communities will need to be developed in a way that leaves no one behind. Raising the income levels of those who are on social assistance is only one aspect of eradicating poverty. First Nations communities provide a humanistic and holistic approach to those seeking assistance with the effects of poverty; this can be attributed as a core value of Indigenous peoples and must be promoted if income security reform is to be successful.

While good progress has been made through these discussions towards identifying a realistic Roadmap for reform, the utmost priority for First Nations is to exercise their jurisdiction over social services. As an interim step, Ontario must grant legislative exemption that provides flexibility for First Nations design and control of social assistance. Work towards implementing full recognition of First Nations self-government in this area needs to continue.

As members of the First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group, we acknowledge this first step towards new strategies that will lead us to collaboration and partnership as directed by our leadership. The First Nations caucus of this working group will continue to participate in technical meetings as a way of partnership-building that will be beneficial as First Nations examine their own practices of social services and model development. We extend our gratitude to the provincial representatives who have treated us with the utmost respect and acknowledge them for their hard work and dedication to this process.

Message From The Urban Indigenous Table On Income Security Reform

The Urban Indigenous Table on Income Security Reform has provided input to the Ministry of Community and Social Services to chart a path towards the reform of Ontario’s income security system, to enhance the economic security and overall well-being of Métis and urban Indigenous communities across the province.

It is essential to recognize that up to 84.1 per cent of Indigenous peoples in Ontario live off-reserve and obtain services in cities and towns across the province, and that urban Indigenous communities are among the most at-risk groups in Ontario.

The Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO), the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres (OFIFC), and the Ontario Native Women’s Association (ONWA) have long advocated for an income security system that provides access to meaningful economic opportunity and upholds the dignity of community members who access income assistance services.

The government’s commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous communities, outlined in The Journey Together, is an integral guiding principle of this Roadmap. In considering reconciliation at every juncture of this initiative, including the enhancement of service delivery standards in urban Indigenous communities, we believe that measurable change can be achieved.

As partners, the MNO, the OFIFC and ONWA co-ordinated urban Indigenous discussion sessions in 2014 to identify the gaps and challenges urban Indigenous communities have experienced in the current social assistance system, and propose ways in which the system could be transformed to enhance outcomes, including recommendations beyond social assistance.

Throughout the Roadmap, there are references to “urban Indigenous people and communities”. This is a term inclusive of the diversity of First Nations (status and non-status), Métis and Inuit people who live in urban and rural communities across Ontario and not on-reserve. Geographically, “urban Indigenous” is not exclusive to Indigenous people living in large urban population centres; it also describes Indigenous people and communities comprised of or within smaller urban and rural population centres. Indigenous people historically and to this day continue to migrate within the province, and between provinces and territories, in pursuit of culture, opportunity and improved well-being. Across Ontario there are diverse organizations that support urban Indigenous people who live in towns and cities through the delivery of culture-based programs and services. It is important to note that while the recommendations in the First Nations section of the Roadmap stem from specific discussions and deliberations at the First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group, many of the issues identified and the historic context are shared by Indigenous communities in urban settings, and many of the recommendations would have a positive impact for all Indigenous people regardless of location.

Community members stressed the importance of listening to the voices of urban Indigenous peoples around their specific needs and challenges, as well as gaps in services, and moving forward in acting on the advice that was shared. Among other concerns, we heard that communities found benefit levels to be inadequate and that program administration is particularly challenging to navigate. We also heard that the ongoing impact of colonialism, including systemic discrimination and racism, have contributed to an unsuitable environment in which to access social assistance services.

Colonialism, including the impact of residential schools, systematic racism, and intergenerational trauma, has had many significant and destructive impacts on urban Indigenous communities. In addition, barriers exist to accessing services that are unique to individual lived experience, as the current income security system overlooks the importance of mental health and culture and well-being, and often overlooks the unique needs of Indigenous women, youth, Elders and LGBTQ2S individuals. These factors have shaped an environment in which Indigenous communities continue to experience significant disparities in education, income and health. Urban Indigenous peoples are therefore in need of income security supports that are not based on a one-size-fits-all approach. Diverse Indigenous cultures shape the needs, priorities and conceptions of well being of urban Indigenous communities across the province.

Culture is a crucial element of Indigenous ways of being, and it is key that this is understood by Ontario’s public service and anyone serving Indigenous communities. It is important that this Roadmap respond to the unique history, diversity and cultures of urban Indigenous communities across the province, and continue to build upon principles identified in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) and the Report and Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Building on the government’s commitment to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples in The Journey Together, the Roadmap seeks to close the gap in outcomes for urban Indigenous communities and create transformational change both inside and outside social assistance.

As such, effecting positive change can only happen through honouring the voices of urban Indigenous communities, which continue to call for greater access, equity, transparency and accountability in the income security system. While positive steps have been taken in this Roadmap, ongoing transformational work and many years of action towards systems change are required.

As part of our work, the Urban Indigenous Table on Income Security Reform has utilized best practices, knowledge and experience from each partnering organization to best capture the unique needs of Métis and urban Indigenous peoples across Ontario. Many of our recommendations for reform have focussed on the need to move away from rule-based approaches that focus on surveillance and enforcement to approaches based on positive interactions, social inclusion and helping people to achieve improved outcomes. We have advocated for urban Indigenous communities and highlighted how the impacts of the current system and potential reforms need to be carefully considered. We look forward to continuing our work to implement the transformational change called for in this Roadmap.

Introduction

Purpose

The Income Security Reform Working Group, the First Nations Income Security Reform Working Group and the Urban Indigenous Table on Income Security Reform

While the three groups met independently of one another, they brought common views on the need for change. The recommendations in this Roadmap are not mutually exclusive—for example, many recommendations in the First Nations section would equally apply in the rest of the province.

Why This Matters

Ontario’s income security system affects us all. No matter our background, our successes or our challenges, we all have a shared interest in supporting everyone’s ability to thrive and contribute to the social fabric of our communities and the economic well-being of our province. Almost everyone has at least one family member, friend or neighbour who is grappling with poverty. As you read and reflect on the Roadmap, we encourage you to keep in mind that the line between poverty and just getting by is a thin one, and many people are a missed paycheque or a family emergency away from needing help.

Here are six reasons why income security reform is everybody’s business:

1. People are facing greater labour market instability, less job security, and more non-standard or precarious work, all of which make it harder to achieve an adequate standard of living.

Consider this:

- The number and kinds of jobs available are changing due to factors such as economic growth, technology, demographics and consumer behaviour. Service-sector jobs are more prevalent, while higher-paying manufacturing jobs are less common

footnote 5 . Changes in the labour market are having a significant impact on people’s ability to earn adequate, sustainable income to improve their circumstances.

Income Security Reform in the context of the Basic Income Pilot

The Working Groups acknowledge the three-year Basic Income Pilot that is underway in the province—an important experiment that will test a new way of providing income support. Many of the recommendations in this Roadmap are complementary to the Basic Income Pilot; lessons learned from the Basic Income Pilot and the first three years of this Roadmap will together be informative and provide an opportunity to refine and potentially adjust the Roadmap in the future.

- From 1997 to 2015, non-standard employment grew at an average annual rate of 2.3% per year, nearly twice as fast as standard employment (1.2%)

footnote 6 . - The Report of the Special Advisor for Ontario’s Changing Workplaces Review identifies a broad range of people experiencing precarious work, from new graduates involuntarily working part-time to individuals working multiple jobs to make ends meet

footnote 7 . - Precarious employment can negatively affect a family’s quality of life and increase stress about financial decisions

footnote 8 . - Poverty rates of workers in non-standard employment are two to three times higher than the poverty rates of workers in standard employment

footnote 9 . - The prevalence of non-standard employment is eroding access to employer- provided benefits. In 2011, less than one-quarter of workers in non-standard employment relationships had job benefits such as medical insurance (23.0%) or dental coverage (22.8%). Even fewer were covered by life and/or disability insurance (17.5%) or had an employer pension plan (16.6%)

footnote 10 . - 21.9% of all unemployed individuals in Ontario experienced long-term unemployment in 2014–15; this circumstance was more prevalent among older workers, affecting about one-third (32%) of unemployed individuals age 45 and older

footnote 11 . - In 2016, the unemployment rate of Indigenous people in Ontario living outside of First Nations communities was 48% higher than non-Indigenous Ontarians (8% versus 5.4%).

- In First Nations communities in Ontario, over one-third of adults (38.2%) were looking for work between 2013 and 2015. Less than half (44.7%) were employed, a significant decline from the 55.6% who were employed in 2008 to 2010. Most of the jobs reported in 2013–15 (79.7%) were located in a First Nations community

footnote 12 . - In identifying clients for its Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy, the federal government indicates that Indigenous youth (i.e., those between the ages of 15 and 30) are the fastest-growing demographic in Canada. They are an important population who will be relied upon to replace older workers as they retire

footnote 13 .

2. Essential needs are increasingly out of reach for many people.

Consider this:

- According to the Canadian Rental Housing Index, 42% of renter households in Ontario spent more than 30% of their before-tax income on rent in 2011

footnote 14 . This included 20% of households who were spending more than 50% of their before-tax income on rent. - According to estimates, Ontario is home to more than 595,000 food insecure households

footnote 15 . A recent study has found that health care costs for Ontario households experiencing moderate food insecurity were 32% higher than for food-secure householdsfootnote 16 . - 84% of First Nations adults living in First Nations communities in Ontario reported cutting the size of their meals or skipping meals due to lack of money for food in the past year

footnote 17 . - In Ontario First Nations communities, the number of adults who sometimes or often ran out of food, with no money for more, increased from 41.3% in 2008–10 to 52.9% in 2013–15

footnote 18 . - Over half of adults in Ontario First Nations communities (55.4%) said they had struggled to meet essential needs in the past year. Over a quarter of adults (27.8%) could not afford to pay for their utilities (heat, hydro and water)

footnote 19 . Transportation was also a struggle given rising gas costs and the need to travel to grocery stores and other shops for essential needsfootnote 20 . - Indigenous peoples are eight times more likely than the general population to experience homelessness in major urban settings

footnote 21 . - In 2014, low-income households spent on average 5.9% of pre-tax income on home energy, while the highest-income households spent only 1.7% of their income on home energy

footnote 22 .

3. It’s harder for people to climb out of poverty.

Consider this:

- According to one federal definition of low income (the Low-Income Measure), there were 1.94 million low-income persons in Ontario in 2015 (the most recent data available)

footnote 23 . In the same year there were 943,368 children and adults in Ontario receiving social assistance – either Ontario Works or ODSPfootnote 24 . This means more than half of the people living in poverty were not receiving social assistance and were unable to access the allowances and benefits that are available only through Ontario Works and ODSPfootnote 25 . - Research by the Social Planning and Research Council of Hamilton found that among adults living in poverty in that city, the chance of escaping poverty the following year had decreased from 44% in 1993 to 26% in 2013

footnote 26 . - A 2011 analysis for the Strengthening Rural Canada Initiatives showed that labour participation rates are 14 percentage points lower in remote areas as compared to urban areas

footnote 27 . - People increasingly think that hard work and motivation are not enough to get ahead. In 2015, 72% of survey respondents agreed that in Toronto hard work and determination are no guarantee that a person will succeed. 52% of respondents also felt that in 25 years the next generation will be worse off than their counterparts are today

footnote 28 . - The prevalence of low income for the Indigenous population living outside of First Nations communities in Ontario is 71% higher when compared to the non-Indigenous population (24% vs. 14%)

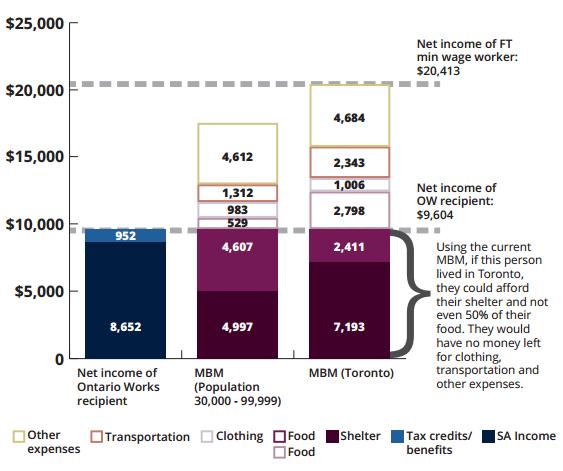

footnote 29 . - Single adults under age 65 have limited income supports available to them, making it difficult to establish themselves with any kind of stability and security and focus on improving their outcomes. Combining maximum social assistance and tax benefits (tax benefits only being available if the individual files taxes):

- Single individuals with no fixed address can access a maximum of $4,677 (81% below the Ontario Poverty Reduction Strategy (PRS) Low-Income Measure (LIM)) if they don’t have a disability, and $8,577 (73% below the PRS LIM plus 30% in recognition of the cost of living with a disability) if they have a disability

- Single individuals who rent accommodation can access a maximum of $9,604 (60% below the PRS LIM) if they don’t have a disability and $14,884 (53% below the PRS LIM plus 30%) if they have a disability

- In First Nations communities in Ontario, 28% of adults reported total annual household income of less than $20,000 in 2008 to 2010. This increased to 35.2% in 2013 to 2015

footnote 30 . - First Nations Administrators have noted that three generations of First Nations people have relied on income assistance.

What is the Low-Income Measure (LIM)?

Based on the after-tax income levels of families, adjusted for household size and composition, the Low-Income Measure identifies the number of families/households whose after-tax income levels are under half (50%) of the median adjusted household income.

In determining the LIM, family income is “adjusted” in the sense that family needs are taken into account. Needs are determined based on the number of people in a household; as you would expect, needs generally increase as the number of household members increase, taking into account certain economies of scale.

The Additional Costs of Disability

The LIM is useful in measuring the prevalence of low-income, but does not account for the added cost of living experienced by those with disabilities. These extra costs vary depending on each person and how disability affects their life. There is no simple and agreed-upon methodology to assess the impact of disability given the vast degree of variation among people’s experiences. A review of literature has shown a range from less than 10% to over 100%

footnote 31 . For this reason, the Roadmap has adopted 30% above the PRS LIM as a global approximation of the additional cost of living with a disability.

There are important considerations to keep in mind when looking at available data about poverty. The Canadian Income Survey (used to derive the percentage of the population below the Low-Income Measure) is not conducted in First Nations communities. In addition, due to historic factors, Indigenous individuals living outside of First Nations communities may not choose to self-identify as Indigenous on federal census and survey forms. The actual poverty rate experienced by Indigenous persons living outside of First Nations communities is likely higher than reported.

4. More people have disabilities and are facing barriers to employment and social inclusion and higher costs of living.

Consider this:

- Right now, almost one in seven Ontarians has a disability. As the proportion of Ontarians age 65 and older increases over the next 20 years, that number is expected to reach one in five

footnote 32 . - There is an increased cost associated with having a disability regardless of an individual’s employment status

footnote 33 . - Autism Ontario estimates one in 94 children have an autism spectrum disorder in Canada and this is expected to increase over time. This is just one example of the increasing prevalence and diagnosis of lifelong disabilities.

- Almost one in two Ontarians who have a developmental disability also have a mental illness

footnote 34 . - In any given week, at least 500,000 employed Canadians are unable to work due to mental health problems. This includes approximately 355,000 disability cases due to mental and/or behavioural disorders and 175,000 full-time workers absent from work due to mental illness

footnote 35 . - Approximately 30% of people in Ontario will experience a mental health and/or substance abuse challenge at some point in their lifetime

footnote 36 . - From 2011 to 2014, the incidence of chronic conditions for First Nations peoples living outside of First Nations communities in Ontario increased drastically: the rate of diabetes increased by 11.2%, arthritis by 15.2%, and high blood pressure by 15.9%

footnote 37 . - The unemployment rate for people with disabilities is about 16%—far higher than the rate for people without disabilities. However this does account for those who have stopped looking for work. Another relevant point is that the participation rate of working-age Ontario adults (aged 16–24) with a disability is only about 52.7%, compared to 79% participation of those who do not have a disability

footnote 38 . This severely limits their contributions to society and the economyfootnote 39 . - There was 3% growth in the 2016–17 ODSP case count as compared to the previous year, greater than the 0.6% growth experienced in Ontario Works cases over the same time period

footnote 40 . As of June 2017, 58% of all social assistance cases were receiving ODSP. - A recent study has shown that there is a nearly 80% higher incidence of arthritis or rheumatism for individuals with the lowest incomes than for those with the highest incomes

footnote 41 . - There is a lack of access to and funding for the high cost of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) testing in municipalities, urban centres and First Nations communities.

5. Poverty and low income negatively impact people’s health and well-being.

Consider this:

- Analysis by Statistics Canada indicates that income inequality is responsible for the premature death of 40,000 Canadians per year. Low-income males and females

footnote 42 have 67% and 52% greater chances respectively of dying each year than their wealthy counterpartsfootnote 43 . - The economic cost of mental illness and addictions in Canada is at least $50 billion per year

footnote 44 . According to a recent study, the burden of mental health and addiction issues on Ontarians is 1.5 times higher than all cancers put together and more than seven times that of all infectious diseasesfootnote 45 . The greatest proportion of these costs derives from:- Health care

- Social services and income support costs

- Lost productivity (from absenteeism and turnover)

- Suicide rates in Canada were found to be almost twice as high in low-income neighbourhoods as in the wealthiest neighbourhoods

footnote 46 . - Studies also show that adult-onset diabetes and heart disease are far more common amongst low-income Canadians

footnote 47 . The poorest one-fifth of Canadians had more than double the rate of diabetes and heart disease when compared to the richest 20%, and a 60% greater rate of two or more chronic health conditionsfootnote 48 . - The percentage of adults reporting that their health is fair or poor declines substantially as you move from low- to high-income earners. For Indigenous adults in Ontario, 34% of low-income earners report fair or poor health compared to 14% of high-income earners

footnote 49 . Social and economic circumstances contribute to 50% of a person’s overall health status with low- income groups showing worse outcomes in 20 of 34 health status indicatorsfootnote 50 . - Today’s jobs require highly literate workers who can read and write and also possess problem-solving, decision-making, critical-thinking and organizational skills. Literacy levels are connected to pressing social and economic issues, including unemployment, poverty, homelessness, poor health, incarceration, social assistance reliance and poor outcomes for children

footnote 51 . - Evidence shows that children in low-income families are 50% less likely to participate in organized sports, arts and cultural activities than children in high-income families. Barriers to participation include user fees, equipment costs, lack of transportation, family support, awareness of opportunities, isolation, inadequate or no facilities in their communities and a lack of safe places to play

footnote 52 . - Many women who have experienced spousal violence also experience higher daily stress levels and related impacts. 53% of women victimized in the preceding 12 months by a spouse stated that most of their days were “quite a bit or extremely stressful”, which is significantly higher than the proportion of women victimized by someone else (41%) and the proportion of women not victimized (23%)

footnote 53 . - The implications of not completing high school in Canada are enormous, with both direct and indirect cost impacts on health, social services, education, employment, criminality and economic productivity

footnote 54 . - 36% of off-reserve Indigenous children under the age of six live in poverty compared to 19 per cent of non-Indigenous children

footnote 55 .

6. Systemic racism and discrimination are contributing to entrenched inequity.

Consider this:

- Indigenous youth from remote northern communities do not have any options but to relocate to a municipality or an urban centre to complete their education. Similarly to the era of residential schools, they are forced to be away from their families for the purpose of learning another way of life. One of the concerns associated with having children move away from their communities is that they will then experience additional racism and discrimination in a situation in which they are isolated and without sufficient supports.

- Indigenous peoples have significant disparities in education, income and health compared with other populations

footnote 56 . In 2016, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal concluded that First Nations have been discriminated against in the provision of Child and Family Services by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada, and ordered that the discriminatory practices must ceasefootnote 57 . - The 2006 Census showed that the overall poverty rate in Canada was 11%, and yet a closer look shows for racialized persons it was 22% compared to 9% for non-racialized persons

footnote 58 .

Newcomers to Ontario are less likely to access social assistance or other programs due to perceived stigma. This reduces their representation in these programs.

- Racialized persons experience disproportionate levels of poverty and barriers accessing employment

footnote 59 . For example, more than 60% of all persons living in poverty in Toronto are racialized and more racialized women live in poverty than racialized menfootnote 60 . - Victims of racial profiling, primarily Black men, experience post-traumatic stress and other stress-related disorders that limit their use of community resources

footnote 61 . - A United Nations working group on issues affecting Black people has signaled an alarm about the poverty, poor health, low educational attainment and overrepresentation of African Canadians in systems such as justice and child welfare

footnote 62 .

Social and economic inclusion cannot be fully achieved until the root causes of systemic racism are addressed.

What does all of this tell us?

Those experiencing poverty are not a homogeneous group and certain populations are at greater risk of living in poverty and may experience vulnerabilities as a result of poverty and low income. A one-size-fits-all approach is not going to achieve the best outcomes. The system needs to be flexible and able to adapt to people’s diverse and changing needs. We must pay particular attention to the cause and depth of poverty among Indigenous, Black and other marginalized populations to ensure interventions are structured to target the barriers they face and track the outcomes to know if the interventions are working.

A Note On Previous Reports

Over the past 30 years, there have been numerous reports on poverty in Ontario and Canada, prepared at all levels of government and by think tanks, academics, advocates and activists. Taken as a whole, there have been thousands of recommendations for reform to the income security system broadly, including the tax system and social services.

Many recommendations have been implemented and inroads have been made over the years resulting in poverty reduction, especially for seniors and children. However, a significant gap remains for working age adults who continue to live in deep poverty. This is because many programs designed to assist working age adults (e.g., Employment Insurance, Workplace Safety and Insurance Board) depend on their level of participation in the workforce. In some instances people contribute to the programs but are not eligible when they need the support. Even when they have a high level of labour force attachment, there are still problems with access. These programs are usually time limited and, in all cases, are inadequate to meet the income security needs of low-income adults. This leaves social assistance to do the "heavy lifting" as it relates to low-income, working-age adults living in poverty.

The Roadmap was produced within this broad context of previous reports. It does not set out to demonstrate that the income security system, including social assistance, is problematic or inadequate; rather it starts with this well- documented assertion:

The current system has failed some people more obviously than others—for example, single people who have little more than a social assistance cheque to rely upon; people who are homeless and often struggling to find safe shelter night by night; newcomers to Canada battling prejudice and a system that seems designed to be against them in many ways; African Canadians who continue to face entrenched anti-Black racism; and Indigenous peoples who have faced prolonged racism, inequity and cultural discrimination.

The Roadmap reflects a holistic plan of action to steer fundamental change over the next 10 years, one that concentrates on the urgent need for immediate action and the subsequent order and timing of the reforms needed to achieve income adequacy.

Ontario’s Income Security System

Overview

Ontario’s income security system provides a range of benefits to individuals and families who have low or no income or who have experienced long-term barriers to full employment. It is a complex system with numerous programs funded, overseen and delivered by municipal, provincial, federal and First Nations governments, as well as the non-governmental sector. The programs vary considerably in their specific form and purpose, target groups, eligibility rules, delivery methods and amounts of support.

These programs can generally be divided between cash and in-kind benefits that are intended to contribute to a set of overarching objectives:

- Making sure people don’t fall below a certain income level.

- Supporting health, well-being and community inclusion.

- Connecting or reconnecting people to jobs.

Income Benefits are monies that are transferred directly to people that generally include:

- Amounts based on paid contributions to replace earnings. For example, Employment Insurance and Canada Pension Plan - Disability or Retirement.

- Amounts provided during periods of very low or no income to help with living costs. For example, social assistance programs (Ontario Works and ODSP) and seniors programs (Old Age Security, Guaranteed Income Supplement, and Guaranteed Annual Income System).

- Amounts that augment other income, sometimes for a specific purpose.

For example, the Canada Child Benefit, Ontario Child Benefit, Assistance for Children with Severe Disabilities, Northern Health Travel Grant and Working Income Tax Benefit.

In-kind benefits provide people with an item or service that is paid for, in part or in full, with the goal of improving standard of living by making the item or service less expensive or free. For example, child-care fee subsidies, Rent-Geared to-Income housing, Ontario Drug Benefit program and Healthy Smiles Ontario.

Ontario also has a suite of employment and training services and income supports to help people achieve their employment goals and be successful in the labour force. These services and supports are primarily provided through Employment Ontario, with a few provided through social assistance as well as federal programs.

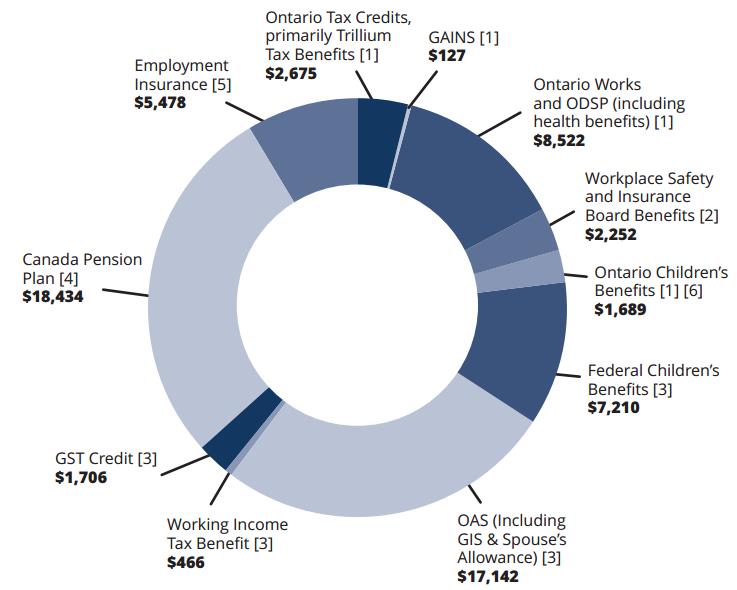

Between the Province and the federal government (and contributory programs such as CPP), approximately $65.7 billion in income security benefits are provided to Ontarians.

Municipalities, First Nations and non-profit organizations also invest in community-based income security programs. While the overall municipal and non-profit investment in income security programs is not available, Ontario municipalities alone had total expenses of over $7 billion after adjustments on social and family services in 2015

Despite significant investment in the broad income security system, it is clear the system is not working well for many people, in large part because it is designed to serve the workforce of the past. Excluding social assistance, most programs including Employment Insurance, Canada Pension Plan (Retirement and Disability) and Workplace Safety and Insurance are based on the assumption that the majority of people have long-term, well paid employment. Stemming from this assumption, these programs pay the highest and longest-duration benefits to people who have enjoyed full-time, well-paying jobs in the recent past. However, these programs primarily work with individuals who are, by definition, ready for work or “employable”. There is a need for programming that focusses on employability-working with individuals on life skills and personal development to help them become employable rather than setting them up for failure.

There is a different reality for the many people who face long-standing barriers to employment or who now toil in a world of work that is low paying, part-time and of limited duration. From their perspective, the range and complexity of the income security system means it can be difficult and confusing to navigate, making it harder to access programs. For each program they have to figure out where to go, how to apply and what information is required. Often, the rules that are in place mean low-income workers cannot qualify for programs such as Employment Insurance in the first place and when people do access benefits, the time limits are arbitrarily short and the benefits inadequate.

The system can also seem inequitable because programs provide varying levels of support to people. For example, a single person working full time at minimum wage could qualify for Employment Insurance (EI) benefits equivalent to $478.50 every two weeks (or $957 per four weeks). A person who falls short of the required hours or who has been unable to find a job at all can receive $721 per month through Ontario Works—that’s 25% less over roughly four weeks than EI benefits for a minimum-wage worker. As minimum wage increases, the gap between EI benefits and Ontario Works will only grow, if equivalent increases to Ontario Works are not made.

Moreover, the rules between programs do not always work well. For example, a person receiving ODSP and living in subsidized housing is generally thought of as being in a good position relative to others receiving social assistance. Yet, if that person finds a job they may see their ODSP support reduced at the same time as their rent increases, making it difficult to get further ahead.