Ontario population projections

Learn about the 2023-2051 population projections for Ontario and its 49 census divisions.

Interim Update: Ministry of Finance Population Projection for Ontario, 2024–2051

Background

Following the release of the federal government’s 2025–2027 Immigration Levels Plan in October 2024, the Ministry of Finance’s population projections have been updated for Ontario.

The new immigration targets are much lower than those of the previous federal immigration plan. Given that immigration is the main driver of population growth in the Ministry of Finance population projections, a new set of projections has been prepared to provide users with the most up-to-date information.

Interim update to Ontario-level population projections

The population projections have been updated and re-based for Ontario only. A complete update of the regional population projections is planned to be released as usual in early summer of 2025. This will include a new report and a fully updated set of tables in the Open Data Catalogue.

The interim update to projections for Ontario uses the new immigration plan targets and takes into account new demographic information released since May 2024, when the assumption for the previous set of projections were set. This includes a new base population (2024), and updated trends for the components of demographic change.

The new federal Immigration Levels Plan included flows of non-permanent residents (NPRs) necessary to reach the goal of 5 per cent NPRs in national population announced in March 2024. The previous set of MOF projections already reflected the federal goal. There are no changes to assumption for non-permanent residents in this interim update.

The following table highlights the main changes in assumptions compared to the previous set of projections that were released on October 1, 2024.

| Item | Previous (Released October 1, 2024) | Interim Update |

|---|---|---|

| Base Population | Statistics Canada population estimates for July 1, 2023 | Statistics Canada population estimates for July 1, 2024 |

| Short-Term Immigration | 2024-26 Immigration Levels Plan Share to Ontario of 43.3% | 2025-27 Immigration Levels Plan Latest share to Ontario (41.7%) |

| Long-Term Immigration | Immigration rate declining from 1.3% in 2027-28 to 1.2% by 2051 | Immigration rate rising from 1.0% in 2027-28 to 1.2% by 2041, stable thereafter. |

| Short-Term Interprovincial Migration | Annual net losses shrinking until 2026 to −5,000 | Annual net losses shrinking until 2027 to −5,000 |

New projection results

The full set of results for the interim update is available in the Open Data Catalogue, including:

- Annual projection of Ontario’s population by age and gender, 2024-2051

- Annual projection of components of demographic change for Ontario, 2024-2051

978-1-4868-8305-9 English HTML - Ontario Population Projections, 2023-2051

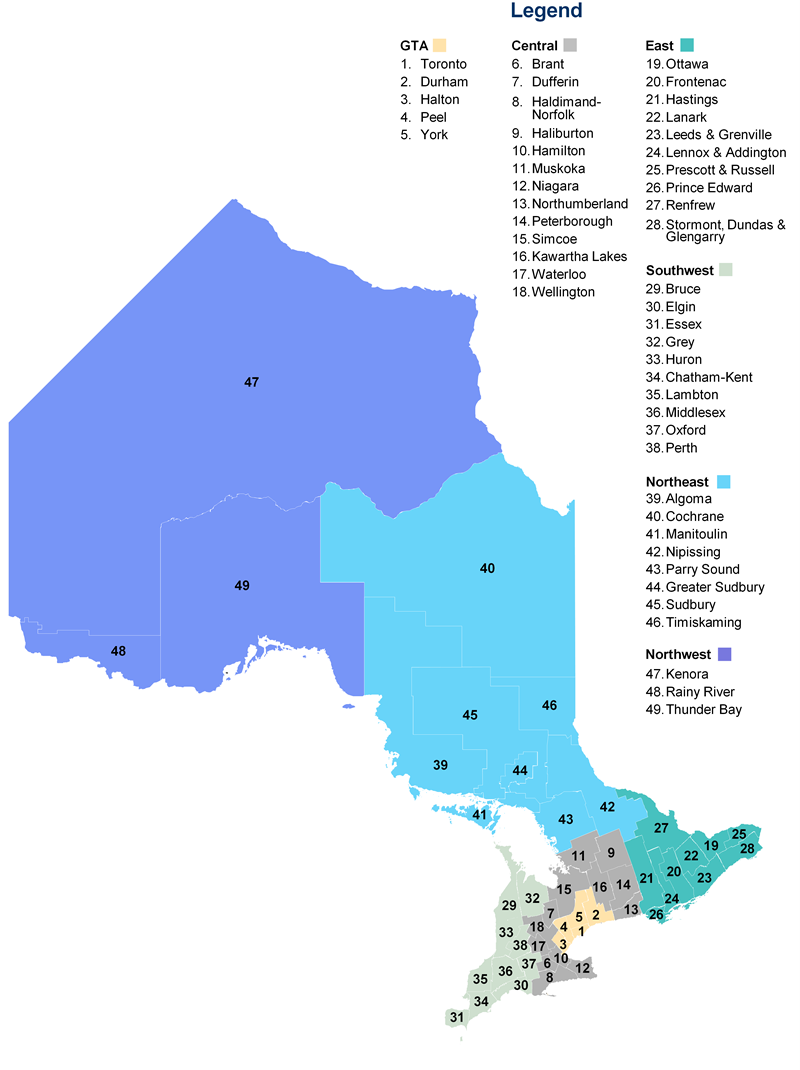

Map of Ontario census divisions

Introduction

This report presents population projections for Ontario and each of its 49 census divisions, by age and gender, from the base year of 2023 to 2051. These projections were published by the Ontario Ministry of Finance in the fall of 2024.

The Ministry of Finance produces an updated set of population projections every year to reflect the most up-to-date trends and historical data. This update uses as a base the 2023 population estimates from Statistics Canada (released in May 2024 and based on the 2021 Census) and includes changes in the projections to reflect the most recent trends in fertility, mortality, and migration.

The new projections include three scenarios for Ontario. The medium, or reference scenario, is considered most likely to occur if recent trends continue. The low- and high-growth scenarios provide a reasonable forecast range based on plausible changes in the components of growth. Projections for each of the 49 census divisions are for the reference scenario only.

The projections do not represent Ontario government policy targets or desired population outcomes, nor do they incorporate explicit economic or planning assumptions. They are developed using a standard demographic methodology in which assumptions for population growth reflect recent trends in all streams of migration and the continuing evolution of long-term fertility and mortality patterns in each census division. Census division projections are summed to obtain the Ontario total.

The report includes a set of detailed statistical tables on the new projections. Key demographic terms are defined in a glossary.

Highlights

Highlights of the new 2023–2051

- Ontario’s population is projected to increase by 41.7 per cent, or over 6.5 million, over the next 28 years, from an estimated 15.6 million on July 1, 2023 to over 22.1 million by July 1, 2051.

- The provincial population is projected to grow rapidly in the short term, increasing at an annual rate of 3.4 per cent in 2023–24 and 1.6 per cent in 2024–25. The rate of growth is then projected to dip to a low of 0.5 per cent by 2027–28, before returning to faster growth of 1.3 per cent by 2029–30. Thereafter, the rate of population growth will ease slowly over time, reaching 1.2 per cent by 2050–51.

- Net migration is projected to account for 97 per cent of all population growth in the province over the 2023–2051 period, with natural increase accounting for the remaining 3 per cent.

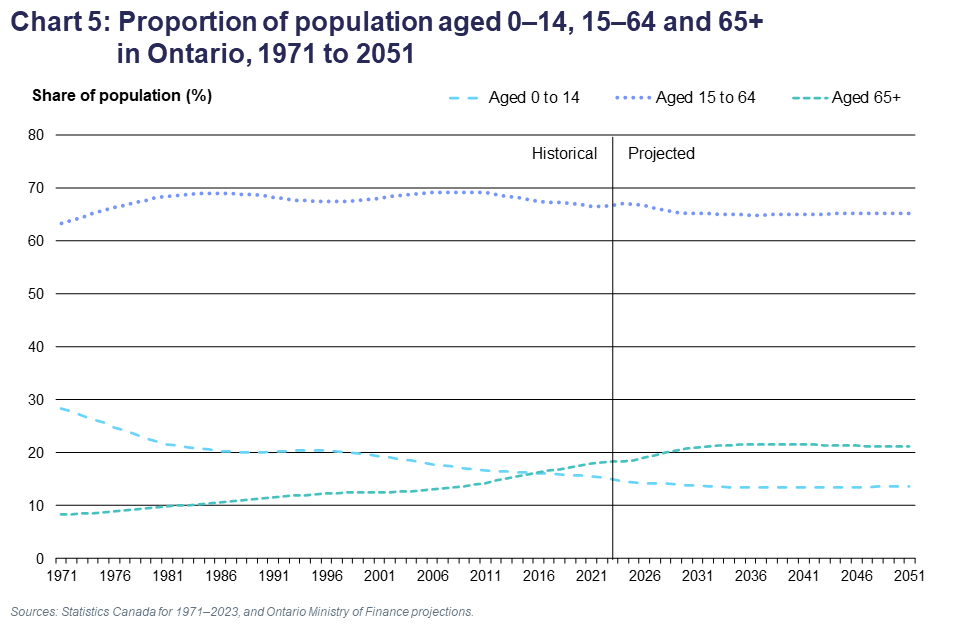

- The number of seniors aged 65 and over is projected to increase significantly, from 2.9 million or 18.3 per cent of population in 2023, to 4.7 million, or 21.3 per cent by 2051. Rapid growth in the share and number of seniors will continue over the 2023–2031 period as the last cohorts of baby boomers turn 65. After 2031, the growth in the number of seniors will slow significantly. Over the projection period, the share of seniors is projected to peak at 21.6 per cent in 2037.

- The number of children aged 0–14 is projected to increase moderately over the projection period, from 2.3 million in 2023 to 3.0 million by 2051. The children’s share of population is projected to decrease from 14.9 per cent in 2023 to 13.4 per cent by 2041, followed by a slow increase to 13.6 per cent by 2051.

- The number of Ontarians aged 15–64 is projected to increase from 10.4 million in 2023 to 14.4 million by 2051. This age group is projected to decline as a share of total population until the mid-2030s, from a peak of 67.1 per cent in 2024 to a low of 64.9 per cent by 2037. Thereafter, this share is projected to remain fairly stable, reaching 65.1 per cent by 2051.

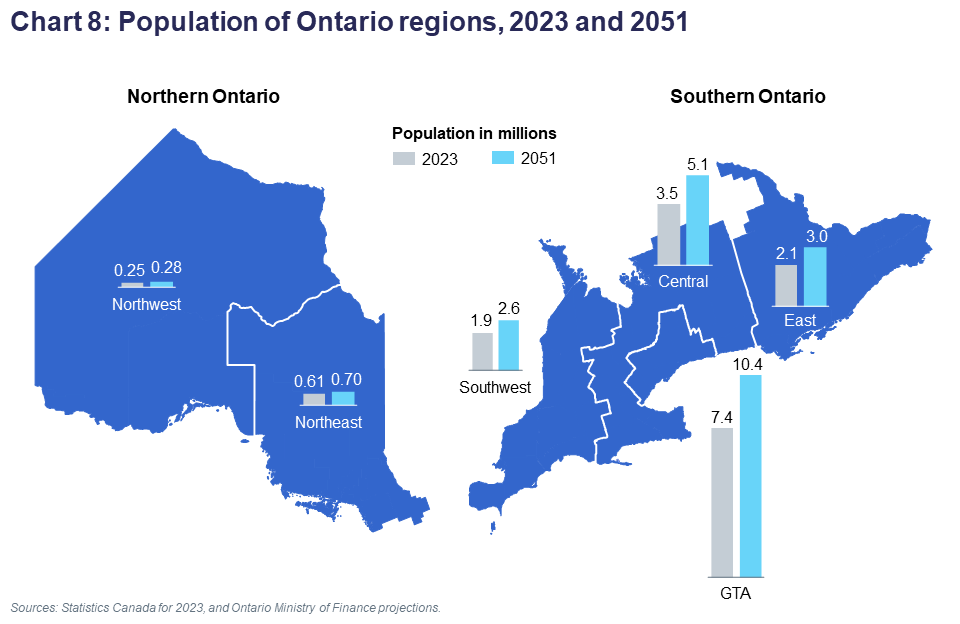

- Each of the six regions of the province are projected to see growing populations over the projection period. Central Ontario is projected to be the fastest growing region, with its population increasing by 1.6 million, or 46.8 per cent, from 3.5 million in 2023 to 5.1 million by 2051. The Greater Toronto Area (GTA) will see the largest increase in population, adding over 3.0 million residents to 2051, with growth of 41.4 per cent, from 7.4 million in 2023 to 10.4 million by 2051. The GTA’s share of provincial population is projected at 47 per cent by 2051, similar to its 2023 share.

- All regions will see a shift to an older age structure. The GTA is expected to remain the region with the youngest age structure as a result of strong international migration and positive natural increase.

Projection Results

Reference, low and high-growth scenarios

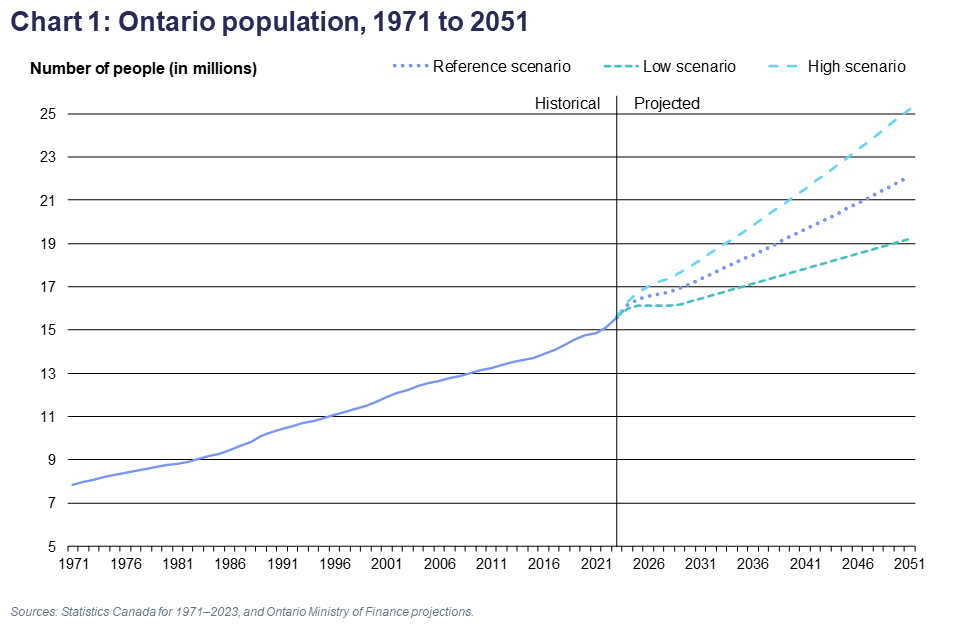

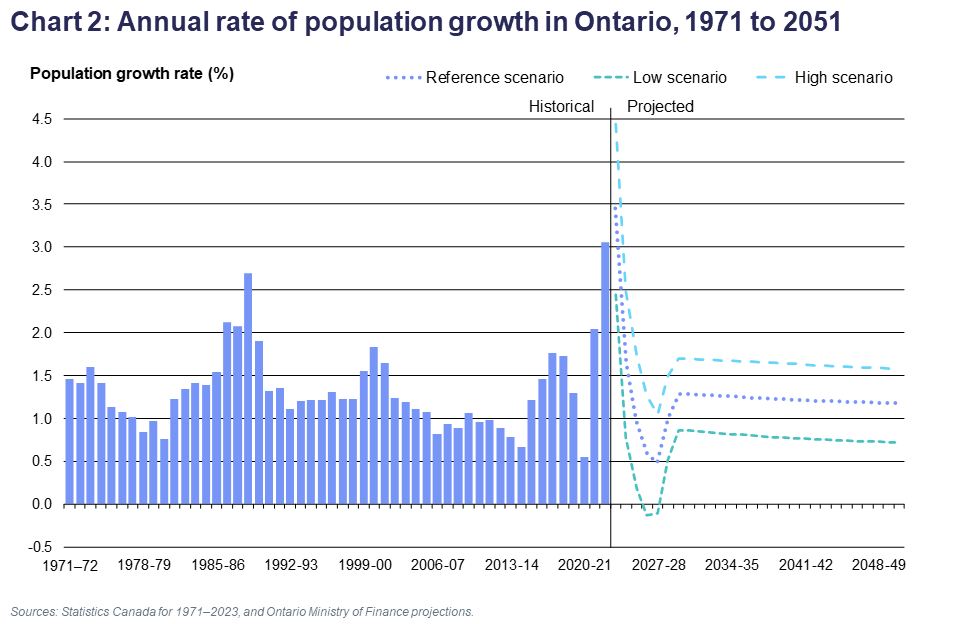

The Ministry of Finance projections provide three growth scenarios for the population of Ontario to 2051. The medium-growth or reference scenario is considered most likely to occur if recent trends continue. The low- and high-growth scenarios provide a forecast range based on plausible changes in the components of growth. Population is projected for each of the 49 census divisions for the reference scenario only. Charts and tables in this report are for the reference scenario, unless otherwise stated.

Under all three scenarios, Ontario’s population is projected to experience growth over the 2023–2051 period. In the reference scenario, population is projected to grow 41.7 per cent, or over 6.5 million, during the next 28 years, from an estimated 15.6 million on July 1, 2023, to over 22.1 million on July 1, 2051.

The provincial population is projected to grow rapidly in the short term, increasing at an annual rate of 3.4 per cent in 2023–24 and 1.6 per cent in 2024–25. The rate of growth is then projected to dip to a low of 0.5 per cent by 2027–28, before returning to faster growth of 1.3 per cent by 2029–30. Thereafter, the rate of population growth will ease slowly over time, reaching 1.2 per cent by 2050–51.

In the low-growth scenario, population increases 23.0 per cent, or 3.6 million, to reach 19.2 million people by 2051. In the high-growth scenario, population grows 61.7 per cent, or 9.6 million, to over 25.2 million people by the end of the projection period.

In the low-growth scenario, the annual rate of population growth is projected to decline rapidly over the first five years of the projections, from 2.4 per cent in 2023–24 to population declines of 0.1 per cent in both 2026–27 and 2027–28. Thereafter, the population will resume growing, reaching a pace of increase of 0.9 per cent in 2029–30, followed by a gradual easing over time to 0.7 per cent by 2050–51. In the high-growth scenario, the annual population growth rate is also projected to fall quickly over the first five projected years, from 4.4 to 1.0 per cent by 2027–28, to return to 1.7 by 2029–30, and then to decline gradually to 1.6 per cent by 2050–51.

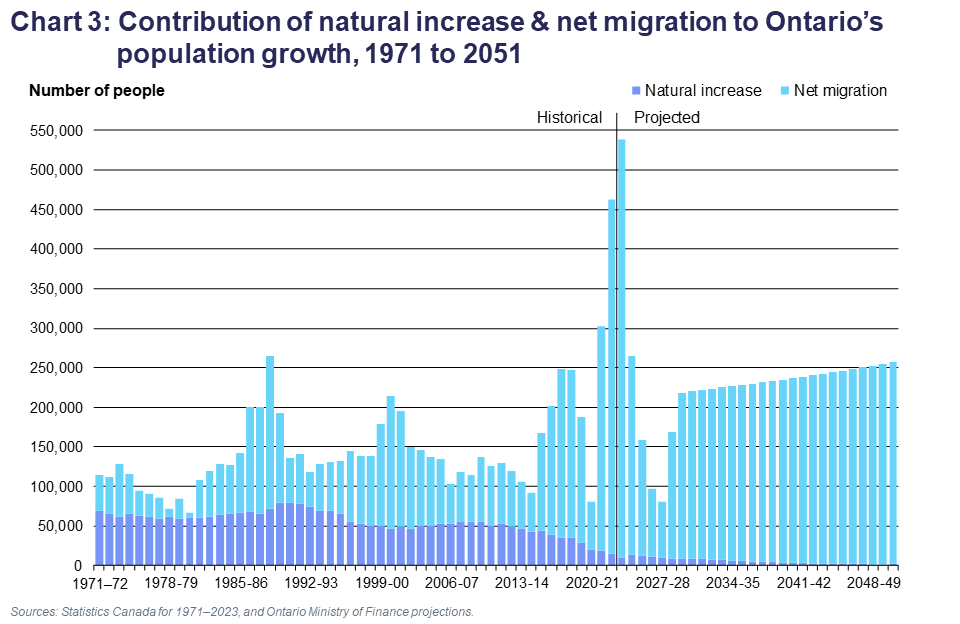

The components of Ontario population change

The contributions of natural increase and net migration to population growth vary from year to year. While natural increase trends evolve slowly, net migration can be more volatile, mostly due to swings in interprovincial migration and variations in international migration. For example, over the past 10 years, the share of population growth coming from net migration has been as low as 53 per cent in 2014–15 and as high as 97 per cent in 2022–23.

Net migration levels to Ontario have averaged about 177,000 per year in the past decade, with a low of 49,000 in 2014–15 and a high of 448,000 in 2022–23. The number of births has been falling slowly, and deaths have been rising more rapidly, resulting in natural increase declining from 46,000 to 15,000 over the last decade.

Recently, net migration was affected by COVID-19 pandemic-related disruptions, slowing from 212,000 in 2018–19 to 60,000 in 2020–21. However, in the past two years net migration to Ontario rebounded to record levels of 283,000 in 2021–22 and 448,000 in 2022–23. While immigration has been rising, the very high net migration levels observed recently have mostly been driven by a rapid increase in the number of non-permanent residents.

In the medium-term, as the net change in non-permanent residents goes from its current elevated levels to annual declines announced by the federal government (more on this topic below), net migration will decline from a projected 528,000 in 2023–24 to 70,000 by 2027–28. Subsequently, net migration is projected to rebound to 209,000 in 2029–30 and increase gradually over the rest of the projection, reaching 255,000 by 2050–51. The share of population growth accounted for by net migration is projected to decline from 98 per cent in 2023–24 to 87 per cent in 2027–28, rebound to 96 per cent in 2029–30, and then slowly rise thereafter to reach over 99 per cent by 2051.

Future levels of natural increase are projected to decrease slowly, from 13,000 in 2024–25 to less than 2,000 by 2050–51. The share of population growth accounted for by natural increase is projected to rise from 2 per cent in 2023–24 to 13 per cent in 2027–28, fall to 4 per cent in 2029–30, and then slowly continue declining thereafter to reach less than 1 per cent by 2051.

The number of deaths is projected to increase over time, as the large cohorts of baby boomers continue to age. By 2031, all baby boomers will be 65 or older. The annual number of deaths is projected to rise from 126,000 in 2023–24 to 192,000 by 2050–51.

Births are also projected to increase over the projection period, but at a slightly slower pace than deaths. The rise in births will be fuelled in the short term by the passage of the baby boom echo (children of baby boomers) through peak fertility years, and subsequently by continued population growth driven by young international migrants. The annual number of births is projected to rise from 137,000 in 2023–24 to 194,000 by 2050–51.

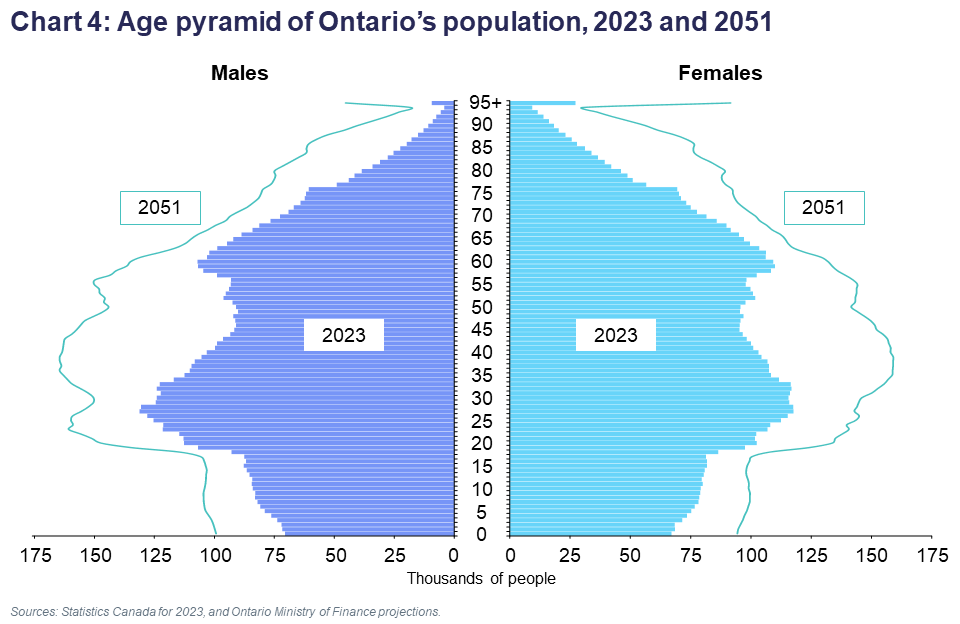

Age structure

By 2051, there will be more people in every single year of age in Ontario compared to 2023, with significantly more older seniors and middle-aged adults. Baby boomers, whose largest cohorts were around age 60 in 2023, will have joined the 80+ age groups. The number of adults aged 35 to 55 will also see a relatively large increase, driven by the continued strong international migration to the province.

The median age of Ontario’s population is projected to continue its current decline in the short term, falling from 40.0 years in 2023 to 39.3 years by 2025. This decline in median age, fuelled by the recent large influx of young international migrants to the province, will be followed by a gradual increase to 42.6 years by 2051. Similarly, the median age for women is projected to fall initially from 41.4 to 40.8 years by 2025, and to rise gradually thereafter to reach 43.7 years by 2051. The median age for men is also projected to decline initially from 38.5 to 37.9 years by 2025, and to increase over the rest of the projections to reach 41.6 years by 2051.

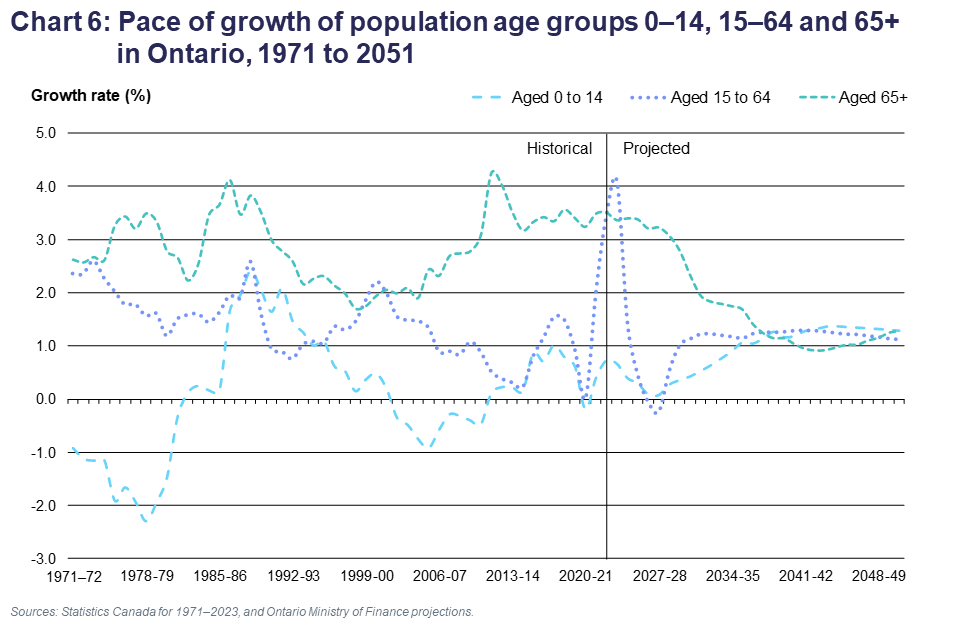

The number of seniors aged 65 and over is projected to increase significantly, from 2.9 million or 18.3 per cent of population in 2023, to 4.7 million, or 21.3 per cent by 2051. In 2016, for the first time, seniors accounted for a larger share of population than children aged 0–14.

By the early 2030s, once all baby boomers have reached age 65, the growth in the number of seniors will slow significantly. Over the projection period, the share of seniors is projected to peak at 21.6 per cent in 2037. The annual growth rate of the senior age group is projected to slow from an average of 3.1 per cent over 2023–31 to 1.3 per cent by the end of the projection period.

The older age groups will experience the fastest growth among seniors. The number of people aged 75 and over is projected to more than double in size, from 1.3 million in 2023 to over 2.7 million by 2051. The number of people in the 90+ group will more than triple, from 143,000 to 495,000.

A substantial imbalance exists in the proportions of women and men in older age groups, as a result of men’s lower life expectancy. The proportion of women among the oldest seniors is projected to remain higher than that of men but will decline slightly as male life expectancy is projected to increase relatively faster. In 2023, there were 31 per cent more women than men in the 75+ age group. By 2051, it is projected that there will be 28 per cent more women than men in the 75+ age group.

The number of children aged 0–14 is projected to increase moderately over the projection period, from 2.3 million in 2023 to 3.0 million by 2051. The children’s share of population is projected to decrease from 14.9 per cent in 2023 to 13.4 per cent by 2041, followed by a slow increase to 13.6 per cent by 2051.

The number of Ontarians aged 15–64 is projected to increase from 10.4 million in 2023 to 14.4 million by 2051. This age group is projected to decline as a share of total population until the mid-2030s, from a peak of 67.1 per cent in 2024 to a low of 64.9 per cent by 2037. Thereafter, this share is projected to remain fairly stable, reaching 65.1 per cent by 2051.

The growth rate of the population aged 15–64 is projected to quickly trend lower initially and see small declines in both 2026–27 and 2027–28 as the number of non-permanent residents in Ontario falls. Thereafter, the pace of annual growth of the 15–64 age group is projected to hover between 1.1 and 1.3 per cent until 2051.

Within the 15–64 age group, the number of youth (those aged 15–24) is projected to increase initially from 2.0 million in 2023 to 2.2 million by 2026. From 2026 to 2028, small annual declines are projected, followed by a return to gradual increases over the rest of the projection horizon to almost 2.6 million. The youth share of total population is projected to increase initially from 12.8 per cent in 2023 to 13.5 per cent by 2025, followed by a gradual decline to 11.5 per cent by 2051.

The number of people aged 25–44 is projected to increase during the projection period, from 4.5 million in 2023 to 6.2 million by 2051, while their share of population is projected to initially increase from 28.7 to 30.0 per cent by 2034, followed by a decline to 28.2 per cent by 2051.

The number of people aged 45–64 is projected to be fairly stable at just under 4.0 million until 2032. Growth of this age group is projected to pick up in the early 2030s and reach 5.6 million by 2051. Its share of population is projected to initially decline from 25.3 in 2023 to 22.5 per cent by 2033, and to resume growing to return to 25.3 per cent by 2051.

Demographic determinants of regional population change

The main demographic determinants of regional population trends are the current age structure of the population, the pace of natural increase, and the migratory movements in and out of each of Ontario’s regions. These determinants vary substantially among the 49 census divisions that comprise the six geographical regions of Ontario and drive significant differences in demographic projections.

The current age structure of each region has a strong influence on projected regional births and deaths. A region with a higher share of its current population in older age groups will likely experience more deaths in the future than a region of comparable size with a younger population. Similarly, a region with a large share of young adults in its population is expected to see more births than a region of similar size with an older age structure. Also, since migration rates vary by age, the age structure of a region or census division will have an impact on the migration of its population.

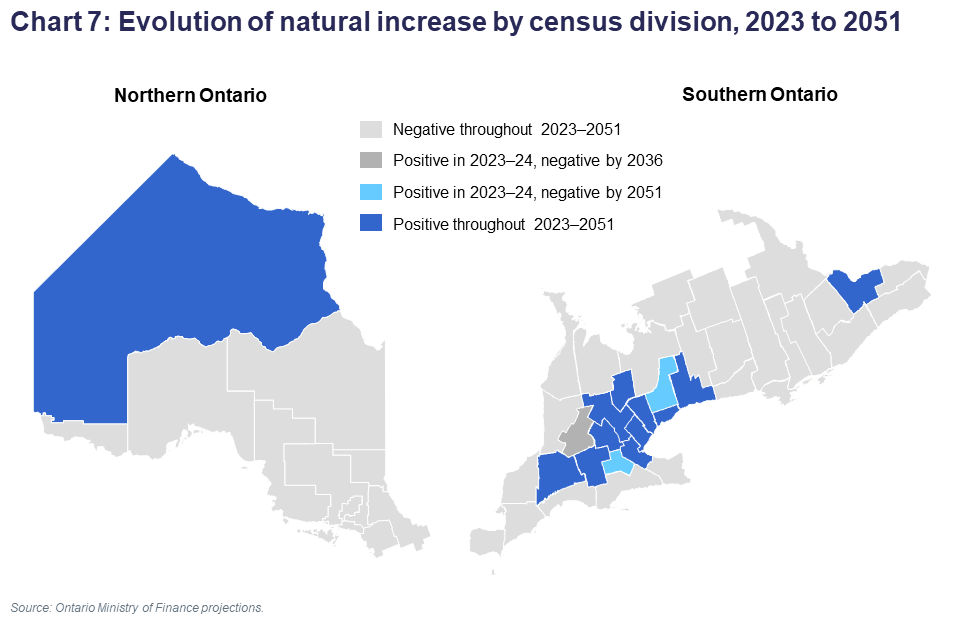

Due to the general aging of the population, most census divisions in Ontario (31 out of 49) were experiencing negative natural increase in 2022–23, where deaths exceeded births. This is projected to continue over the projection period. Although they will continue represent a majority of census divisions, the combined population of the 37 census divisions with negative natural increase by 2051 will account for only 36 per cent of Ontario’s population.

Many census divisions in Ontario where natural increase previously was the main or even sole contributor to population growth have already started to see their population growth slow. This trend is projected to continue as the population ages further.

Migration is the most important factor contributing to population growth for Ontario and for most of its regions. Net migration gains, whether from international sources, other parts of Canada or other regions of Ontario, are projected to continue to be the major source of population growth for almost all census divisions.

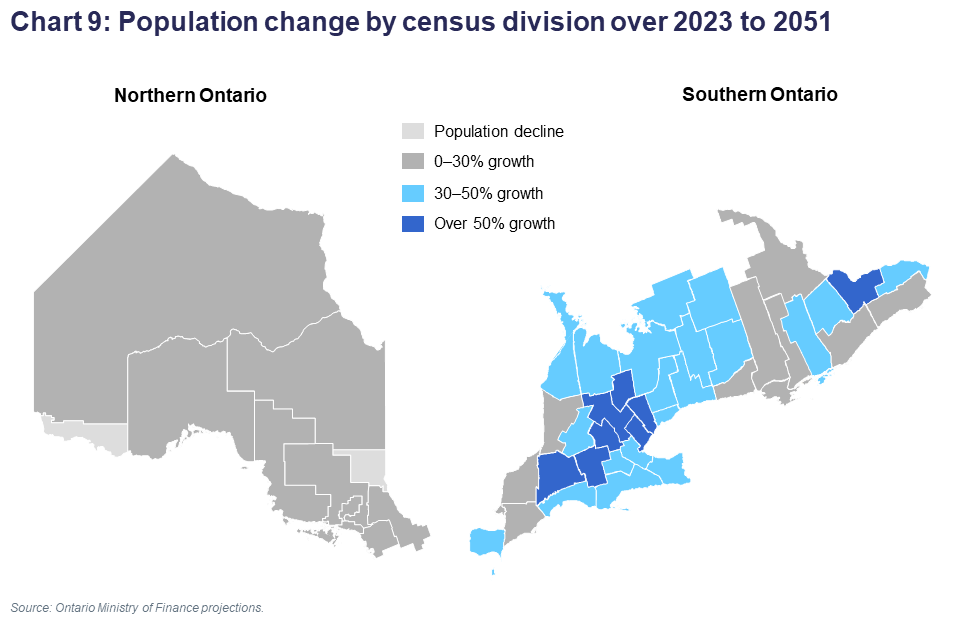

Large urban areas, especially the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), which receive most of the international migration to Ontario, are projected to experience the highest levels of population growth. For other regions such as Central Ontario, the continuation of migration gains from other parts of the province will be a key source of population increase. Some census divisions of Northern Ontario tend to receive only a small share of international migration while experiencing net out-migration, mostly among young adults, which reduces projected population growth.

Regional population growth

The GTA is projected to see the largest increase in population among regions, accounting for 47 per cent of Ontario’s net population growth to 2051. The GTA’s population is projected to increase from 7.4 million in 2023 to over 10.4 million in 2051. The region’s share of total Ontario population is projected to decline initially from 47.0 to 46.5 per cent by 2029, and then rise back up to 47.0 per cent by 2051.

Within the GTA, Toronto’s population is projected to rise from 3.1 million in 2023 to 4.2 million in 2051, adding 1.1 million people, the largest population gain projected among census divisions. Nevertheless, Toronto’s projected population growth rate of 34.7 per cent to 2051 is slower than the provincial rate of 41.7 per cent. The four census divisions of the suburban GTA are projected to add a total of 2 million people over the projection period. Peel (52.8%), Halton (52.5%) and Durham (44.7%) are projected to grow faster than the average for Ontario, while York’s population is projected to grow at a pace (35.9%) slower than the province as a whole.

Central Ontario is projected to be the fastest growing region of the province, adding 1.63 million residents for growth of 46.8 per cent, from 3.47 million in 2023 to 5.10 million in 2051. The region’s share of provincial population is projected to rise slightly from 22.3 to 23.1 per cent during the same period. Many census divisions of Central Ontario are projected to continue experiencing population growth significantly above the provincial average, lead by Waterloo at 59.5 per cent, Dufferin at 54.3 per cent, and Wellington at 52.6 per cent.

The population of Eastern Ontario is projected to grow 45.7 per cent over the projection period, from 2.06 million to 3.00 million. Ottawa, the fastest growing census division in Ontario, is projected to grow by 60.2 per cent, from 1.11 million in 2023 to 1.79 million in 2051. All other Eastern Ontario census divisions are also projected to grow, but below the provincial average, with growth ranging from 18.4 per cent in Prince Edward to 40.2 per cent in Lanark.

The population of Southwestern Ontario is projected to grow from 1.86 million in 2023 to 2.63 million in 2051, an increase of 41.1 per cent. Growth rates within Southwestern Ontario vary, with Middlesex and Oxford growing fastest (56.7 and 51.9 per cent respectively), and Chatham-Kent and Lambton growing at the slowest pace (19.4 and 18.6 per cent respectively).

The population of Northern Ontario is projected to grow slowly over the projection horizon, with an increase of 15.2 per cent, from 854,000 in 2023 to 984,000 by 2051. Within the North, the Northeast is projected to see population growth of 94,000 or 15.6 per cent, from 606,000 to 700,000. The Northwest is projected to experience growth of 35,000 or 14.2 per cent, from 249,000 to 284,000.

Table A: Population Shares of Ontario Regions, 1986 to 2046

| Share of Ontario Population (%) | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | 2021 | 2031 | 2041 | 2051 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTA | 42.0 | 44.5 | 47.2 | 47.2 | 46.7 | 46.7 | 47.0 |

| Central | 22.2 | 22.1 | 21.6 | 21.1 | 22.8 | 23.0 | 23.1 |

| East | 13.9 | 13.5 | 13.2 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 13.6 | 13.6 |

| Southwest | 13.7 | 13.0 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 12.0 | 11.9 |

| Northeast | 5.8 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Northwest | 2.4 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991–2021, and Ontario Ministry of Finance projections.

Regional age structure

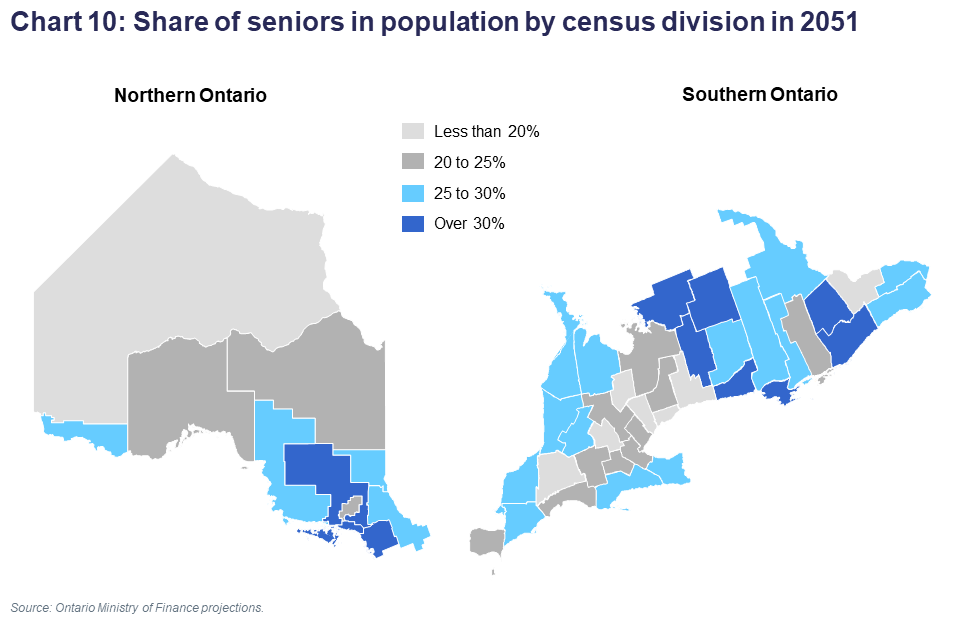

All regions are projected to see a continuing shift to an older age composition of their population. The largest shifts in age structure are projected to take place in census divisions, many in northern and rural areas, where natural increase and net migration are projected to remain or become negative. The GTA is expected to remain the region with the youngest age structure, a result of strong international migration and positive natural increase. The Northeast is projected to remain the region with the oldest age structure.

In 2023, the share of seniors aged 65 and over in regional population ranged from a low of 16.2 per cent in the GTA to a high of 23.1 per cent in the Northeast. Among census divisions, it ranged from 14.5 per cent in Waterloo to 36.4 per cent in Haliburton.

By 2051, the share of seniors in regions is projected to range from 19.4 per cent in the GTA to 25.6 per cent in the Northeast. Among census divisions, it is projected to range from 16.8 per cent in Waterloo to 39.2 per cent in Haliburton.

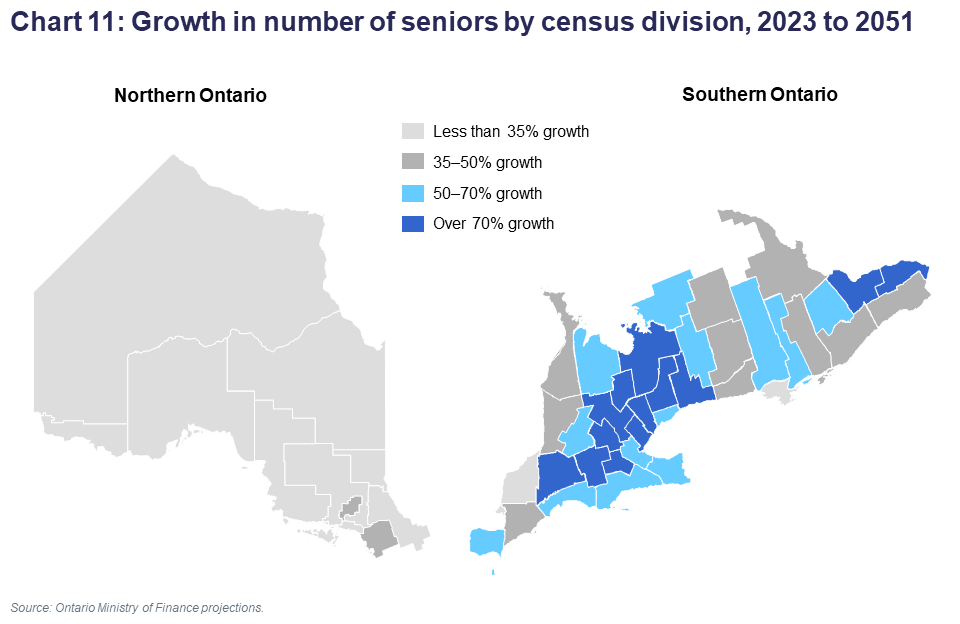

Even as the share of seniors in census divisions located in and around the suburban GTA is projected to remain lower than the provincial average, the increase in the number of seniors will be highest in this area.

The number of seniors is projected grow by 83 per cent in the suburban GTA. Conversely, the number of seniors grows most slowly (less than 10 per cent) in Timiskaming and Rainy River.

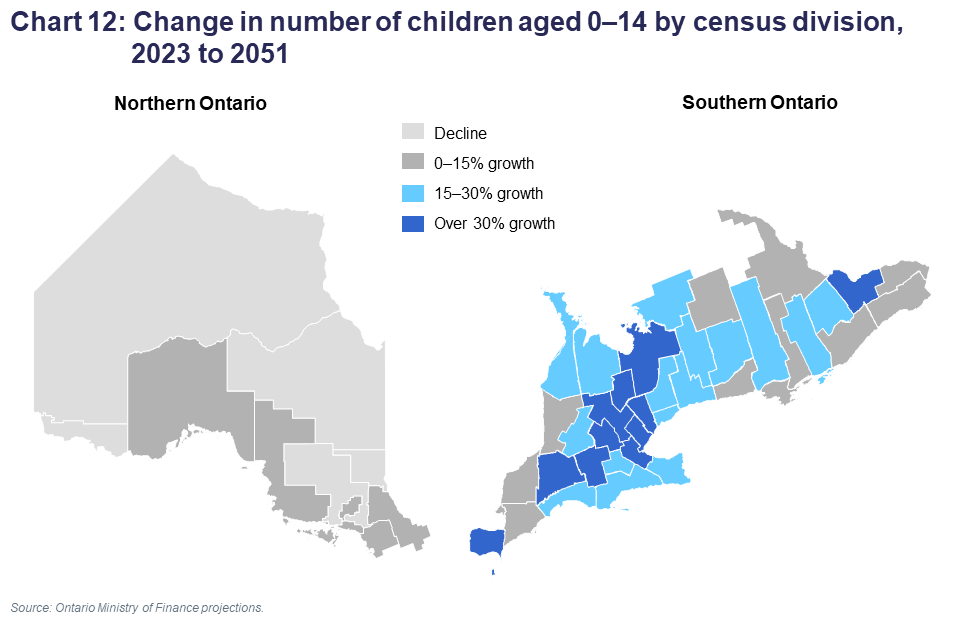

The number of children aged 0–14 is projected to increase in all regions, except the Northwest, over the projection period. However, the share of children in every region is projected to decline slightly throughout the projections. In 2023, the highest share of children among regions was in the Northwest at 16.2 per cent; the Northeast had the lowest share at 14.0 per cent. By 2051, the Northeast is projected to remain the region with the lowest share of children at 13.0 per cent while the highest share is projected to be found in the Southwest at 14.4 per cent.

Waterloo, Peel, and Ottawa are projected to record growth of over 40 per cent in the number of children aged 0–14 over the 2023–2051 period. Conversely, Rainy River, Timiskaming, Cochrane, and Sudbury are projected to see a decline in the number of children aged 0–14 over that period. In 2023, the highest share of children was found in Kenora at 20.4 per cent and the lowest share in Haliburton at 9.6 per cent. By 2051, Kenora is projected to still have the highest share of children at 17.1 per cent, while Haliburton is projected to continue to have the lowest at 8.2 per cent.

The share of population aged 15–64, which ranged from 62.9 per cent in the Northeast to 69.3 per cent in the GTA in 2023, is projected to decline to 2051 in every region, except the Northwest. The share of this age group is projected to range from 61.5 per cent of population in the Northeast to 67.1 per cent in the GTA by 2051.

The number of people aged 15–64 is projected to increase in every census division of the province except for Rainy River, Timiskaming, and Cochrane. The share of population in this age group is projected to decrease in 45 census divisions, while Kenora, Thunder Bay, Bruce and Peterborough will see slightly higher shares by 2051. The highest share of people aged 15–64 in 2023 was in Toronto (71.0 per cent) while the lowest was in Prince Edward (53.9 per cent). By 2051, Toronto is projected to remain the region with the highest share of population in this age group (70.0 per cent), followed by Waterloo, Peel, and Ottawa. Prince Edward (50.9 per cent) and Haliburton (52.6 per cent) are projected to have the lowest shares by 2051.

Methodology and Assumptions

Projections methodology

The methodology used in the Ministry of Finance’s long-term population projections is the cohort-component method, essentially a demographic accounting system. The calculation starts with the base-year population (2023) distributed by age and gender.

A separate analysis and projection of each component of population growth is made for each year, starting with births. Then, projections of deaths and the five migration components (immigration, emigration, net change in non-permanent residents, interprovincial in- and out-migration, and intraprovincial in- and out-migration) are also generated and added to the population cohorts to obtain the population of the subsequent year, by age and gender.

This methodology is followed for each of the 49 census divisions. The Ontario-level population is obtained by summing the projected census division populations.

It should be noted that the population projections are demographic, founded on assumptions about births, deaths and migration over the projection period. Assumptions are based on the analysis of the long-term and the most recent trends of these components, as well as expectations of future direction. For Ontario, the degree of uncertainty inherent in projections is represented by the range between the low- and high-growth scenarios, with the reference scenario representing the most likely outcome.

Base population

This report includes demographic projections released by the Ministry of Finance that use the latest population estimates based on the 2021 Census adjusted for net under-coverage. Specifically, the projections use Statistics Canada’s preliminary postcensal population estimates for July 1, 2023 as a base.

As well as providing a new starting point for total population by age and gender, updating the projections to a new base alters the projected age structure and population growth in each census division. It also has an impact on many components of population growth that are projected by using age-specific rates, such as births, deaths, and several of the migration streams.

Fertility

The projected number of births for any given year is obtained by applying age-specific fertility rates to cohorts of women in the reproductive age group, ages 15 to 49. The projection model relies on four parameters

Assumptions are based on a careful analysis of past age-specific fertility trends in Ontario and a review of fertility trends elsewhere in Canada and in other countries. A general and common trend is that a growing proportion of women are giving birth in their 30s and early 40s. The overall decline in the fertility rate among young women is accompanied by a rise in fertility rates among older women. Over the past 20 years and most recently, teenagers and women in their early 20s have experienced the sharpest declines in fertility rates. Fertility rates of women in their 30s and older, which were rising moderately over the 1990s and more rapidly over most of the 2000s, have shown a slower pace of increase in more recent years. These are the same cohorts of women who postponed births during their 20s and are now having children in their 30s and early 40s.

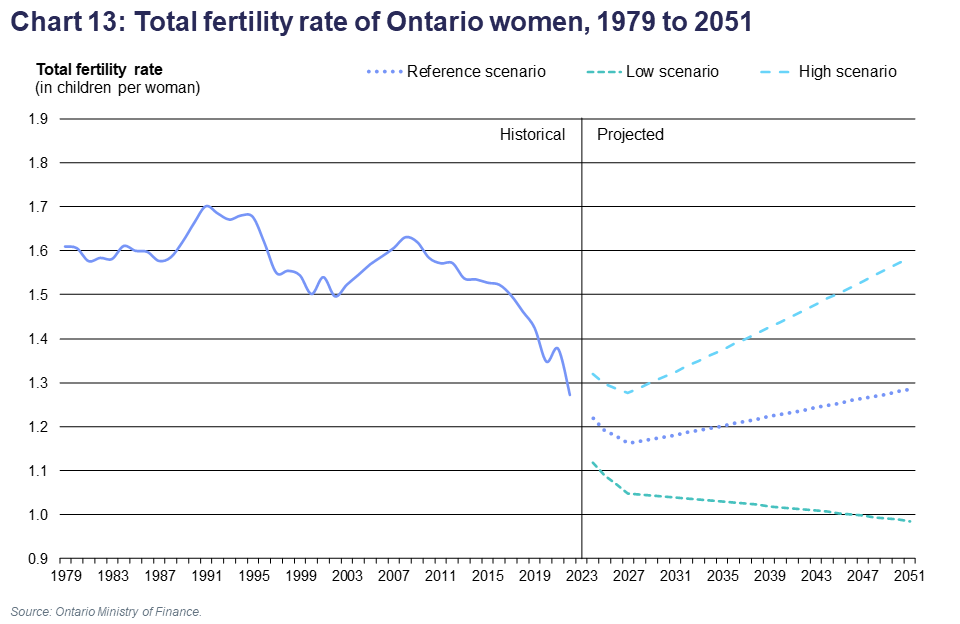

Ontario’s total fertility rate (TFR), which stood at 3.8 children per woman around 1960, fell below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman in 1972. Over the rest of the 1970s, the TFR fell rapidly toward the 1.50 to 1.70 range where it was hovering until recently. It fell below 1.40 for the first time in 2020, and the latest data available for Ontario (2022) shows a TFR of 1.27.

The latest rapid decline in the TFR was driven by younger age groups, which now have fertility rates that are relatively very low compared to similar jurisdictions, as well as from a historical perspective. These declines in fertility for younger women are projected to continue at a slowing pace in the short term, leading to a continued fall in the TFR. However, a projected slow increase in fertility for women aged 35+ is set to drive a subsequent gradual increase in overall fertility in the province to 2051, back to TFR values observed most recently.

In the reference scenario, the TFR is assumed to decline initially from 1.22 in 2023–24 to 1.16 by 2026–27, and to subsequently rise slowly as younger women’s fertility rates stabilize while those of older women continue to gradually increase, returning to 1.28 children per woman by 2051.

In the low- and high-growth scenarios, fertility is assumed to follow a similar pattern of initial decline followed by a slight increase. By 2051, the TFR reaches 0.98 children per woman in the low-growth scenario and 1.58 in the high-growth scenario.

Fertility assumptions at the census division level

The most recent complete data for census divisions (2021) shows that TFRs range from a high of 2.08 in Bruce to a low of 1.09 in Toronto. The projected parameters for fertility at the census division level are modelled to maintain regional differences. The census division-to-province ratio for mean age at fertility in the most recent period is assumed to remain constant. The variance and skewness of fertility distributions for census divisions evolve over the projection period following the same absolute changes of these parameters at the Ontario level.

Mortality

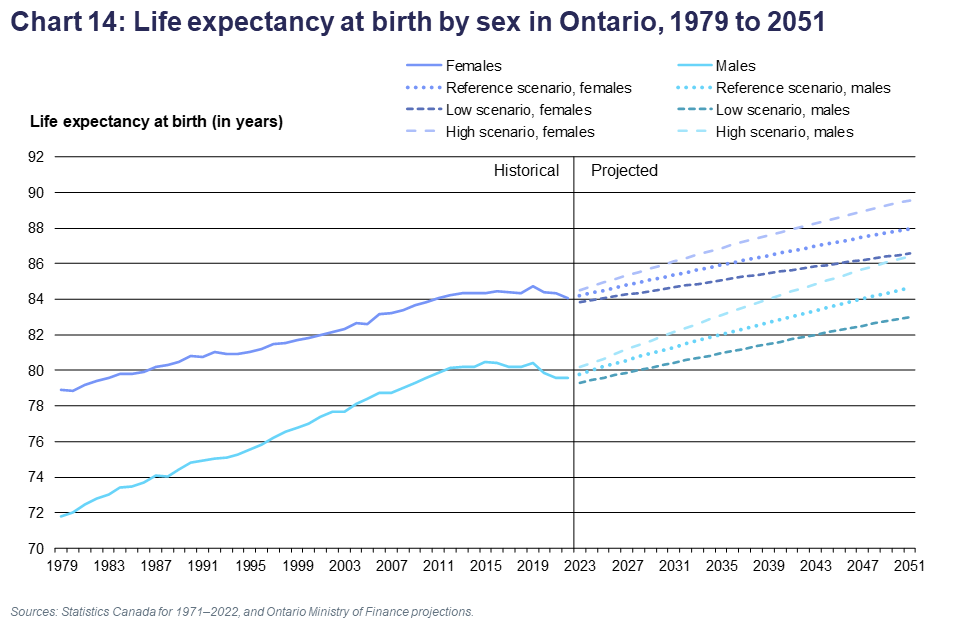

The population of Ontario has one of the highest life expectancies in Canada and the developed world. The latest data shows that life expectancy at birth in Ontario was 84.1 years for females and 79.6 years for males in 2022. Deaths related to opioid overdoses and the COVID-19 pandemic have recently had negative impacts on the pace of life expectancy improvements. However, the generally accepted view is that life expectancy will continue to rise over the long term in Canada and around the world.

Up to the mid-1990s, annual gains in life expectancy were becoming smaller and it was expected that future improvements would continue at this slowing speed. The pace of annual gains in life expectancy then picked up over the next two decades, and the progression of life expectancy became more linear. Until the mid-2010s, average gains in life expectancy were in the order of 0.16 years per year for females and 0.23 years for males. However, in recent years and even before the pandemic, average life expectancy gains slowed in Ontario, partly due to an increase in opioid-related deaths, but mostly as a result of a slowdown in the improvement of survival rates from heart diseases, which was the main driver of increases in life expectancy over the past decades. It is assumed that other factors, such as continued progress in fighting cancer, will drive increases in the average lifespan at a gradual pace over the projection period.

The projected number of deaths each year is obtained by applying projected age-specific mortality rates to population cohorts of corresponding ages. Projections of age-specific death rates are derived

All three projection scenarios for Ontario reflect a continuation of the gains recorded in average life expectancy. Male life expectancy is expected to progress at a faster pace than that of females under the long-term mortality assumptions for each of the three scenarios. This is consistent with recent trends where males have recorded larger gains in life expectancy than females. This has resulted in a shrinking of the gap in life expectancy between males and females, a trend that is projected to continue. Furthermore, reflecting current trends, future gains in life expectancy are modelled to be concentrated at older ages and to be smaller for infants.

In the reference scenario, life expectancy in Ontario is projected to continue increasing, but slower than the average observed before the slowdown started in the middle of the 2010s, with the pace of increase gradually diminishing over the projection period. By 2051, life expectancy is projected to reach 84.6 years for males and 88.0 years for females. This represents total life expectancy gains of 5.1 years for males and 3.9 years for females between 2022 and 2051.

In the low-growth scenario, life expectancy increases at a slower pace, to 83.0 years for males and 86.6 years for females by 2051. In the high-growth scenario, life expectancy reaches 86.4 and 89.6 years in 2051 for males and females respectively.

Table B: Life expectancy in Ontario, 1986 to 2046

| Item | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | 2021 | 2031 | 2041 | 2051 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males at birth | 74.9 | 77.4 | 79.9 | 79.6 | 81.3 | 83.0 | 84.6 |

| Males at age 65 | 15.7 | 17.2 | 19.0 | 19.6 | 20.7 | 21.9 | 23.1 |

| Females at birth | 80.7 | 82.0 | 84.1 | 84.4 | 85.4 | 86.7 | 88.0 |

| Females at age 65 | 19.6 | 20.3 | 22.0 | 22.5 | 23.2 | 24.3 | 25.3 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1991–2021, and Ontario Ministry of Finance projections.

Mortality assumptions at the census division level

At the census division level, the mortality assumptions were developed using a ratio methodology. The Ontario-level mortality structure was applied to each census division’s age structure over the most recent six years of comparable data and the expected number of deaths was computed. This was then compared to the actual annual number of deaths for each census division over this period to create ratios of actual-to-expected number of deaths. These ratios were then multiplied by provincial age-specific death rates to create death rates for each census division. These were then applied to the corresponding census division population to derive the number of deaths for each census division.

The ratio of actual-to-expected deaths for each census division was rather stable over time and did not reveal a consistent pattern of convergence or divergence among regions. For this reason, the most recent ten-year average ratio for each census division was held constant over the projection period.

Components of net migration

The following sections discuss assumptions and methodology for the components of net migration, including immigration, emigration, non-permanent residents, interprovincial migration and intraprovincial migration.

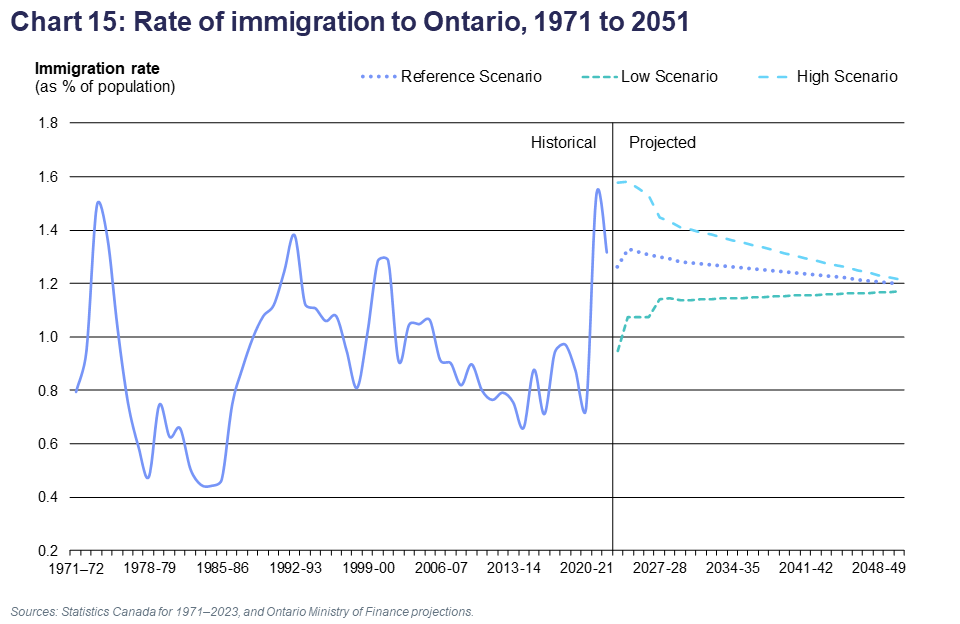

Immigration

Immigration levels in Canada are determined by federal government policy. The federal Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) sets the national target and target range for the level of immigration to be achieved over the following year(s). For calendar year 2024, the target is set at 485,000, with a plan for 500,000 in both 2025 and 2026. These represent a significant increase from the targets set in recent years. The share of immigrants to Canada settling in Ontario increased slightly in calendar year 2023, from 42.3 per cent in 2022 to 43.8 per cent. These latest shares are in line with pre-pandemic trends, above Ontario’s share of the Canadian population (38.9%). This is projected to continue in the projections.

In the reference scenario, annual immigration levels to Canada are projected to remain at 500,000 until 2029–30, corresponding to about 217,000 for Ontario with a provincial immigration rate of 1.28 per cent. Over the rest of the projection period, the number of immigrants increases slowly over time as population grows, such that annual immigration is projected to reach 262,000 by 2050–51. The immigration rate will gradually decline after 2029–30 to reach 1.2 per cent by the end of the projection period.

Immigration levels in the low-growth scenario are set at 85 per cent of reference scenario levels in the long term, resulting in immigration levels rising to 223,000 by 2050–51. In the high-growth scenario, immigration levels are set at 115 per cent of reference scenario levels in the long term, resulting in immigration rising strongly to reach 302,000 by 2050–51.

Immigration assumptions at the census division level

Projected immigration shares for each census division are based on the trends observed in the distribution of immigrants by census division over the recent past. These shares evolve throughout the projection period following established trends. The average age-gender distribution pattern for immigrants observed over the past five years is assumed to remain constant over the entire projection period. Nearly 90 per cent of immigrants coming to Ontario in 2022–23 were aged 0 to 44.

Emigration

Total emigration is defined as the flow of international emigration, minus returning emigrants. The level of total emigration from Ontario was 14,200 in 2022–23, in line with levels observed over the previous five years.

In the reference scenario, the average emigration rates by age and gender for each census division over the 2017 to 2023 period (excluding pandemic year 2020–21) are used to model the projected number of people emigrating annually from each census division. The modelling is dynamic, taking into account the annual changes in age structure within census divisions. For Ontario as a whole, this results in the number of emigrants increasing gradually over the projection period to reach 21,200 by 2050–51.

In the low-growth scenario, emigration rates by age and gender used in the reference scenario are increased by 30 per cent, making them 130 per cent of recently-observed rates. This results in emigration levels reaching 24,600 by 2050–51.

In the high-growth scenario, emigration rates by age and gender used in the reference scenario are reduced by 30 per cent, making them equivalent to 70 per cent of recently-observed rates. This results in the number of emigrants reaching 15,800 by 2050–51.

Non-permanent residents

There were almost one million non-permanent residents (NPRs: e.g., foreign students, temporary foreign workers, refugee claimants) living in Ontario on July 1, 2023. These foreign residents are part of the base population since they are counted in the Census and are included in the components of population change. The year-to-year change in the total number of NPRs is accounted for as a component of population growth in the projections. Establishing assumptions for this component is complicated due to the transient nature of the group and considerable year-to-year fluctuations resulting from changing federal policies.

The increase in the number NPRs in Ontario averaged 71,000 annually over the three years before the pandemic (2016–19), significantly higher that the average of the previous 20 years (11,000). In 2019–20 and 2020–21, travel restrictions and immigration initiatives targeting candidates already in Canada under temporary residence permits slowed the increase in the number of non-permanent residents in Ontario. However, 2021–22 and 2022–23 saw a record increases of 101,000 and 305,000, respectively.

These latest record increases in the population of NPRs led the federal government in March 2024 to start announcing multiple measures aimed at reducing their numbers as a proportion of the Canadian population. The initial announcement was a reduction from 6.2 to 5.0 per cent of the national population over the next three years. However, since the announcement was made, the proportion has kept increasing, reaching 6.8 per cent on April 1, 2024. Therefore, a reduction back to 5.0 per cent would now entail about a one-quarter decrease in the share of NPRs in the national population.

In the reference scenario, the proportion of NPRs in Ontario’s population is projected to decline according to the federal goal, falling by 24 per cent. However, the timeline for the reduction is assumed to be five years (2024 to 2029), instead of the announced goal of three years. Given the continued increases in the share since the announcement was made, and the significant lag expected for the new and yet-to-be-announced policies to take effect, the five-year horizon is thought to be more realistic. Moreover, since the federal government does not fully control the inflow of many rapidly increasing categories of NPRs, such as asylum claimants, the number and share of NPRs in Ontario’s population are projected to keep increasing in the short term.

For 2023–24, the net increase in the number of NPRs in the reference scenario is set at 377,000, which has mostly already taken place according to Statistics Canada’s latest population estimates to April 1, 2024. A significantly smaller net gain of 75,000 is also projected for 2024–25. This is followed by consecutive annual net losses of 42,000, 110,000, 125,000 and 35,000 over the following four years to 2029. Thereafter, a return to small annual net gains is projected, as the number of NPRs in Ontario is assumed to rise by 1.3 per cent yearly, similar to the rate of increase in the total population and roughly maintaining their proportion of the provincial population. The resulting annual net gain in NPRs rises slowly over the rest of the projections, from 15,000 in 2029–30 to 19,000 by 2050–51.

The low- and high-growth scenarios are set as a range of 30 per cent below and above the reference scenario over the long term. By 2050–51, the annual net gain in NPRs reaches 13,000 in the low-growth scenario and 25,000 in the high-growth scenario.

Non-permanent resident assumptions at the census division level

Projected shares of the net change in non-permanent residents for each census division, as well as their distributions by age and gender, are based on the shares observed over the last five years. The distribution pattern is assumed to remain constant over the projection period.

Interprovincial migration

Interprovincial migration is a component of population growth that fluctuates significantly from year to year. Although Ontario remains a major province of attraction for migrants from some other provinces, trend analysis of the last three decades reveals a mixed pattern of several years of gains followed by several years of losses. This pattern is usually closely tied to economic cycles.

Over the past 30 years, net interprovincial migration has not contributed to Ontario’s population growth, with net losses averaging about 4,400 people per year. Between 2015 and 2020, net interprovincial migration to Ontario had been positive. However, the most recent data shows a reversal of this trend, with net losses recorded in the last three years.

In the reference scenario, annual net interprovincial migration to Ontario is set at -30,000 for 2023–24, reflecting the most recent data, followed by net losses of 21,700 in 2024–25, and 13,300 in 2025–26. The long-term assumption of a net annual loss of 5,000 starts in 2026–27, remaining at that level for the rest of the projection period.

The low- and high-growth scenarios are set as a range of 10,000 above and below the reference scenario net loss in 2023–24 and 2024–25. This range is narrowed to 7,500 in 2025–26, and to 5,000 over the rest of the projection period.

The annual in-flows corresponding to the long-term net migration levels in the low-growth, reference and high-growth scenarios are 60,000, 62,500 and 65,000 respectively. The corresponding annual out-flows are 70,000, 67,500 and 65,000.

Interprovincial migration assumptions at the census division level

For each census division, interprovincial migration flows reflect migration rates by age and gender observed during the last five years and vary over the projection period following Ontario-level fluctuations. Each census division’s share of Ontario inflow and outflow of interprovincial migrants over the last five years is applied to projected flows for the province and held constant throughout the projection period.

Intraprovincial migration

At the census division level, intraprovincial migration, or the movement of population from one census division to another within the province, is a significant component of population growth. This component directly affects population growth only at the census division and regional levels.

From 2001 to 2021, the annual number of intraprovincial migrants in Ontario had fluctuated within the 358,000 to 442,000 range. However, the propensity to migrate within Ontario increased as a result of the pandemic, with 568,000 intraprovincial migrants in 2021–22 and 549,000 in 2022–23.

In the short term, the annual number of intraprovincial migrants is projected to return to more normal levels, falling from 526,000 in 2023–24 to 469,000 by 2027–28. Over the rest of the projections, it is projected to increase slowly to reach 514,000 by 2050–51. The resulting rate of intraprovincial migration in Ontario declines from 3.4 per cent in 2023–24 to 2.8 per cent in 2027–28, and 2.4 by 2050–51.

Intraprovincial migration assumptions at the census division level

The projected number of people by age, leaving each census division for each year of the projections, as well as their destination within the province, is modelled using origin-destination migration rates by age and census division over the past five years. Because migration rates are different for each census division and because age groups have different origin-destination behaviours, the methodology provides an approach to project movers based on observed age and origin-destination migration patterns. The modelling is dynamic, taking into account the annual changes in age structure within census divisions.

The evolution of intraprovincial migration patterns in each census division was studied to identify specific trends and the intraprovincial migration rate assumptions were adjusted to account for these trends.

Glossary

- Baby boom generation

- People born during the period following World War II, from 1946 to 1965, marked by a significant increase in fertility rates and in the number of births.

- Baby boom echo

- People born during the period 1972 to 1992. Children of baby boomers.

- Cohort

- Represents a group of persons who have experienced a specific demographic event during a given period, which can be a year. For example, the birth cohort of 1966 consists of the number of persons who were born in 1966.

- GTA

- The Greater Toronto Area, comprised of the census divisions of Toronto, Durham, Halton, Peel and York.

- International migration

- Movement of population between Ontario and a foreign country. International migration includes immigrants, emigrants and non-permanent residents. Net international migration is the difference between the number of people entering and the number of people leaving the province from foreign countries.

- Interprovincial migration

- Movement of population between Ontario and the rest of Canada. Net interprovincial migration is the difference between the number of people entering Ontario from the rest of Canada and the number of people leaving Ontario for elsewhere in Canada.

- Intraprovincial migration

- Movement of population between the 49 census divisions within Ontario. Net intraprovincial migration for a given census division is the difference between the number of people moving from the rest of Ontario to this census division and the number of people leaving it for elsewhere in the province.

- Life expectancy

- A statistical measure reflecting the average number of years of life remaining for members of a particular population at a specific age if they were to experience during their lives the age-specific mortality rates observed in a given year.

- Median age

- The median age is the age at which exactly one half of the population is older, and the other half is younger. This measure is often used to compare age structures between jurisdictions.

- Natural increase

- The number of births minus the number of deaths.

- Net migration

- Difference between the number of people entering and the number of people leaving a given area. This includes all the migration components included in net international migration, net interprovincial migration and net intraprovincial migration (for sub-provincial jurisdictions).

- Non-permanent residents

- Foreign citizens living in Ontario with a valid work, study, or other permit, or who have claimed refugee status (e.g., international students, foreign workers, and refugee claimants).

- Population aging

- An expression used to describe shifts in the age distribution of the population toward more people of older ages. One indicator of population aging is an increasing share of seniors (ages 65+) in the population.

- Population estimates

- Measures of current and historical resident population derived using Census and administrative data.

- Total fertility rate

- The sum of age-specific fertility rates during a given year. Indicates the average number of children that a generation of women would have if, over the course of their reproductive life, they had fertility rates identical to those of the year considered.

Statistical tables

View the related statistical tables at Ontario's Open Data Catalogue

Accessible chart descriptions

Chart 1: Ontario population, 1971 to 2051

This line chart shows the estimated total population of Ontario from 1971 to 2023, and the projection to 2051 for the three scenarios (reference, high and low). Over the historical period, Ontario’s population increased from 7.8 million in 1971 to 15.6 million in 2023. Over the projections period 2023-2051, the three scenarios gradually diverge. In the reference scenario, total population reaches 22.1 million in 2051. Ontario’s population reaches 25.2 million in the high scenario and 19.2 million in the low scenario at the end of the projection period.

Chart 2: Annual rate of population growth in Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This chart shows historical annual growth rates of Ontario’s population as bars from 1971 to 2023, and projected growth rates as lines for the three scenarios (reference, high and low). Over the historical period, annual growth rates start at 1.5% in 1971-72, and then decline to reach 0.8% in 1980-81. This is followed by higher growth rates culminating at 2.7% in 1988-89, with a lower peak of 1.8% in 2000-01, trending lower to 0.7% in 2014-15, and finally reaching 3.1% in 2022-23. The projected annual growth rate of Ontario’s population in the reference scenario is 3.4% in 2023-24, trending down thereafter to reach 1.2% in 2050-51. In the high scenario, annual population growth goes from 4.4% in 2023-24 to 1.6% over the projection period. In the low scenario, population growth goes from 2.4% in 2023-24 to 0.7% in 2050-51.

Chart 3: Contribution of natural increase & net migration to Ontario’s population growth, 1971 to 2051

This area chart shows the annual contribution of natural increase and net migration to Ontario’s population growth from 1971 to 2051. Over the historical period, natural increase was more stable than net migration, starting at about 69,000 in 1971-72, with an intermediate high point of 79,000 in 1990-91, and a declining trend to 15,000 by 2022-23. Over the projection period, natural increase is projected to increase gradually, reaching 2,000 by 2050-51. Net Migration was more volatile over the historical period, starting at about 45,000 in 1971-72, with a low point of 10,000 in 1978-79, peaks of 194,000 in 1988-89, 168,000 in 2000-01, and 448,000 in 2022-23. Annual net migration is projected to decrease initially from 528,000 in 2023-24 to 70,000 in 2027-28 and rise gradually for the rest of the projection period to reach 255,000 by 2050-51.

Chart 4: Age pyramid of Ontario’s population, 2023 and 2051

This population pyramid shows the number of people of each age in Ontario in 2023 and 2051 separately for males and females. In 2023, the pyramid starts at the bottom with about 70,000 each for males and females aged zero, and gradually widens to over 130,000 people per cohort in their late 20s. This is followed by a narrowing of the pyramid to about 90,000 at late 40s ages, and a peak of 107,000 at age 60. The pyramid subsequently narrows to only a few thousand people per cohort at ages 95+. The 2051 line starts at around 100,000 each for both males and females at age zero with steep peak of 162,000 at age 23, followed by a gradual decrease to around 150,000 near age 29, another peak of 139,000 at age 39, and a decline to age 95+.

Chart 5: Proportion of population aged 0–14, 15–64 and 65+ in Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This chart has three lines showing the evolution of the share of Ontario’s population in age groups 0-14, 15-64 and 65+ over the 1971-2051 period. The highest proportion is aged 15-64 and is fairly stable over the historical period between 60% and 70%, with a declining trend starting around 2010. Over the projection period, the share of people aged 15-64 is projected to fall from 66.7% to 65.1%. The share of population aged 0-14 is seen falling gradually from 28.4% in 1971 to 14.9% in 2023, with a further decline to 13.4% by 2041, and an increase to 13.6% by 2051. The share of seniors increased slowly from 8.3% in 1971 to 18.3% in 2023, will keep rising to reach 21.6% in 2037 and subsequently decline to 21.3% by 2051. The share of seniors surpassed that of children in 2016.

Chart 6: Pace of growth of population age groups 0–14, 15–64 and 65+ in Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This line chart shows the pace of annual growth of population age groups 0-14, 15-64 and 65+ in Ontario from 1971 to 2051. The 65+ age group grows faster than the other two groups for most of the historical and the first half of the projection period, with a peak of 4.3% in 2011-12 and a low close to 0.9% in the early 2040s. The annual pace of growth of the 15-64 age group is seen trending gradually lower from 2.4% in 1971-72 to 0.2% in 2014-15, followed by a peak of 4.1% in 2023-24, annual declines in both 2026-27 and 2027-28, then rising above 1.0 per cent from 2029 to 2051. The 0-14 age group recorded declines from 1971 to 1982 with a trough of -2.3% in 1978-79, and then again from 2002 to 2011. Over the projection period, growth in the number of children is projected decline initially from 0.7% in 2023-24 to 0.1% in 2027-28, ending at 1.3% by 2050-51.

Chart 7: Evolution of natural increase by census division, 2023 to 2051

This map shows the evolution of natural increase by census division in Ontario over the projection period 2023-51. The census divisions are split in four categories.

Census divisions where natural increase is projected to be negative throughout 2023-2051 include: Rainy River, Thunder Bay, Cochrane, Algoma, Sudbury, Greater Sudbury, Timiskaming, Manitoulin, Parry Sound, Nipissing, Essex, Lambton, Chatham-Kent, Huron, Elgin, Bruce, Grey, Haldimand-Norfolk, Niagara, Simcoe, Muskoka, Haliburton, Kawartha Lakes, Peterborough, Northumberland, Hastings, Prince Edward, Lennox & Addington, Frontenac, Renfrew, Lanark, Leeds & Grenville, Prescott & Russell, and Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry.

One census division where natural increase is projected to be positive in 2023-24, but negative by 2036: Perth.

Two census division where natural increase is projected to be positive in 2023-24, but negative by 2051: Brant and York.

Census divisions where natural increase is projected to be positive throughout 2023-2051 include: Kenora, Middlesex, Oxford, Waterloo, Wellington, Hamilton, Dufferin, Halton, Peel, Toronto, Durham, Ottawa.

Chart 8: Population of Ontario regions, 2023 and 2051

This chart shows a map of Ontario’s 6 regions with bars showing their total populations in 2023 and 2051.

For 2023, the chart shows total population in millions for each of the regions as:

Northwest 0.25, Northeast 0.61, Southwest 1.9, Central 3.5, GTA 7.4, East 2.1.

For 2051, the chart shows total population in millions for each of the regions as:

Northwest 0.28, Northeast 0.70, Southwest 2.6, Central 5.1, GTA 10.4, East 3.0.

Chart 9: Population change by census division over 2023 to 2051

This map shows the population growth by census division in Ontario over the projection period 2023-51. The census divisions are split in four categories.

Census divisions where population is projection to decline include: Rainy River, Timiskaming.

Census divisions where population is projected to increase between zero and 30% include: Kenora, Thunder Bay, Cochrane, Algoma, Manitoulin, Sudbury, Greater Sudbury, Nipissing, Parry Sound, Lambton, Chatham-Kent, Huron, Northumberland, Hastings, Prince Edward, Renfrew, Lennox & Addington, Leeds & Grenville, Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry.

Census divisions where population is projected to increase between 30% and 50% include: Essex, Elgin, Perth, Bruce, Grey, Haldimand-Norfolk, Niagara, Brant, Hamilton, Toronto, York, Durham, Simcoe, Haliburton, Peterborough, Kawartha Lakes, Muskoka, Frontenac, Lanark, Prescott & Russell.

Census divisions where population is projected to increase by over 50% include: Middlesex, Oxford, Wellington, Dufferin, Waterloo, Halton, Peel, Ottawa.

Chart 10: Share of seniors in population by census division in 2051

This map shows the projected share of seniors in the population of Ontario census divisions in 2051. The census divisions are split in four categories.

Census divisions with less than 20% seniors in 2051 include: Kenora, Middlesex, Waterloo, Dufferin, Peel, Toronto, Durham, Ottawa.

Census divisions with between 20% and 25% seniors in 2051 include: Thunder Bay, Cochrane, Greater Sudbury, Essex, Elgin, Oxford, Brant, Hamilton, Halton, Wellington, Simcoe, York, Frontenac.

Census divisions with between 25% and 30% seniors in 2051 include: Rainy River, Algoma, Timiskaming, Nipissing, Lambton, Chatham-Kent, Perth, Bruce, Huron, Grey, Haldimand-Norfolk, Niagara, Peterborough, Hastings, Renfrew, Lennox & Addington, Prescott & Russell, Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry.

Census divisions with over 30% seniors in 2051 include: Manitoulin, Sudbury, Parry Sound, Muskoka, Haliburton, Kawartha Lakes, Northumberland, Prince Edward, Lanark, Leeds & Grenville.

Chart 11: Growth in number of seniors by census division, 2023 to 2051

This map shows the growth in number of seniors in the population of Ontario census divisions between 2023 and 2051. The census divisions are split in four categories.

Census divisions with less than 35% projected growth in number of seniors over 2023-2051 include: Kenora, Rainy River, Thunder Bay, Cochrane, Timiskaming, Algoma, Manitoulin, Sudbury, Nipissing, Lambton, Prince Edward.

Census divisions with between 35% and 50% projected growth in number of seniors over 2023-2051 include: Greater Sudbury, Parry Sound, Chatham-Kent, Huron, Bruce, Haliburton, Peterborough, Northumberland, Renfrew, Frontenac, Leeds & Grenville, Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry.

Census divisions with between 50% and 70% projected growth in number of seniors over 2023-2051 include: Essex, Elgin, Perth, Haldimand-Norfolk, Hamilton, Niagara, Grey, Toronto, Muskoka, Kawartha Lakes, Hastings, Lennox & Addington, Lanark.

Census divisions with over 70% projected growth in number of seniors over 2023-2051 include: Middlesex, Oxford, Brant, Waterloo, Wellington, Dufferin, Simcoe, Halton, Peel, York, Durham, Ottawa, Prescott & Russell.

Chart 12: Change in number of children aged 0–14 by census division, 2023 to 2051

This map shows the growth in number of children aged 0-14 in the population of Ontario census divisions between 2023 and 2051. The census divisions are split in four categories.

Census divisions with a projected decline in number of children aged 0-14 over 2023-2051 include: Rainy River, Kenora, Cochrane, Timiskaming, Sudbury.

Census divisions with between 0% and 15% projected growth in number of children aged 0-14 over 2023-2051 include: Thunder Bay, Algoma, Manitoulin, Greater Sudbury, Parry Sound, Nipissing, Lambton, Chatham-Kent, Huron, Haliburton, Northumberland, Prince Edward, Renfrew, Lennox & Addington, Leeds & Grenville, Prescott & Russell, Stormont, Dundas & Glengarry.

Census divisions with between 15% and 30% projected growth in number of children aged 0-14 over 2023-2051 include: Elgin, Perth, Bruce, Grey, Brant, Haldimand-Norfolk, Niagara, York, Toronto, Durham, Kawartha Lakes, Peterborough, Hastings, Frontenac, Muskoka, Lanark.

Census divisions with over 30% projected growth in number of children aged 0-14 over 2023-2051 include: Essex, Middlesex, Oxford, Waterloo, Wellington, Hamilton, Halton, Dufferin, Peel, Simcoe, Ottawa.

Chart 13: Total fertility rate of Ontario women, 1979 to 2051

This line chart shows the historical total fertility rate of Ontario women from 1979 to 2022, and projections under the three scenarios for 2023-2051. Over the historical period, the total fertility rate in Ontario was hovering within a narrow range between 1.70 and 1.50 from the late 1970s to about 2017. Then it fell to 1.27 in 2022. The total fertility rate is projected to reach 1.28 in 2050-51 under the reference scenario, 0.98 under the low scenario, and 1.58 under the high scenario.

Chart 14: Life expectancy at birth by sex in Ontario, 1979 to 2051

This line chart shows the historical life expectancy at birth by gender in Ontario from 1979 to 2022, and projections under three scenarios for 2023-2051

For females, life expectancy at birth rose from 78.9 years in 1979 to 84.1 years in 2022. Over the projection period to 2051, life expectancy of females is projected to increase gradually to reach 88.0 years under the reference scenario, 89.6 years under the high scenario, and 86.6 years under the low scenario.

For males, life expectancy at birth rose from 71.8 years in 1979 to 79.6 years in 2022. Over the projection period to 2051, life expectancy of males is projected to increase gradually to reach 84.6 years under the reference scenario, 86.4 years under the high scenario, and 83.0 years under the low scenario.

Chart 15: Rate of immigration to Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This line chart shows the historical immigration rate to Ontario from 1971 to 2023 and projections under three scenarios to 2051. Over the historical period, the immigration rate was very volatile, starting at 0.79% in 1971-72, rising to 1.49% by 1973-74, declining to a low of 0.44% by the mid-1980, rising again to 1.38% by 1992-93, then falling gradually to reach 0.66% in 2014-15, and rebounding 1.32% to in 2022-23.

Over the projections period 2023-2051, the immigration rate to Ontario is initially projected initially at 1.26% in the reference scenario in 2023-24, 1.58% in the high scenario, and 0.95% in the low scenario. This is followed by gradual changes to 2050-51 in all scenarios to reach 1.20% in the reference scenario, 1.21% in the high scenario, and 1.17% in the low scenario.

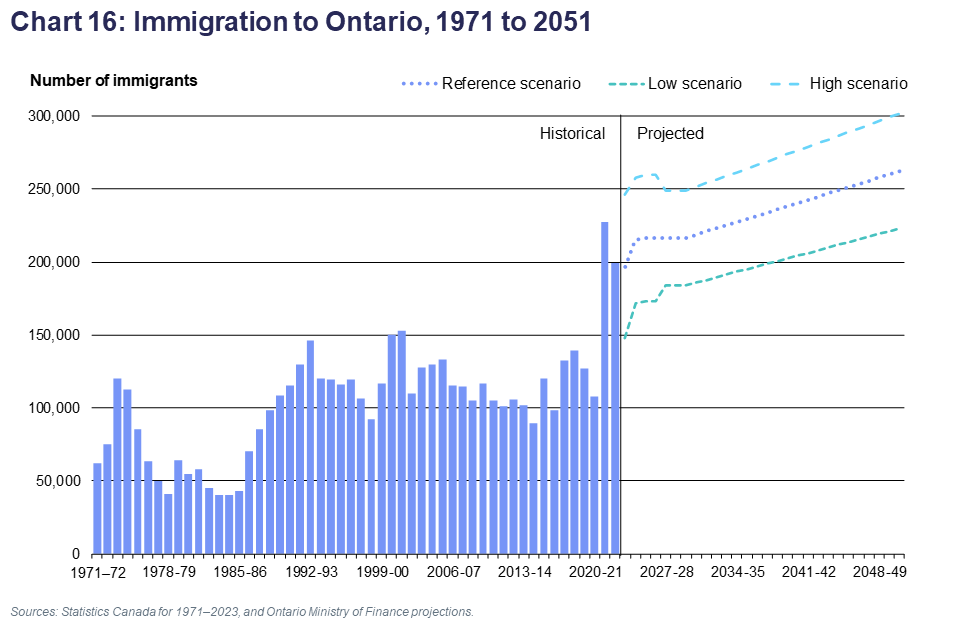

Chart 16: Immigration to Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This chart shows historical annual immigration levels to Ontario from 1971 to 2023 and projections under three scenarios to 2051. Over the historical period, immigration was very volatile, stating at about 62,000 in 1971-72, rising to 120,000 by 1973-74, falling to 40,000 in the mid-1980s, rising to peak at 153,000 in 2001-02, gradually declining thereafter to reach 90,000 in 2014-15, and rebounding to 227,000 in 2021-22.

Immigration to Ontario is projected to increase from 197,000 in 2023-24 to 262,000 in 2050-51 in the reference scenario, from 246,000 to 302,000 in the high-growth scenario, and from 148,000 to 223,000 in the low-growth scenario.

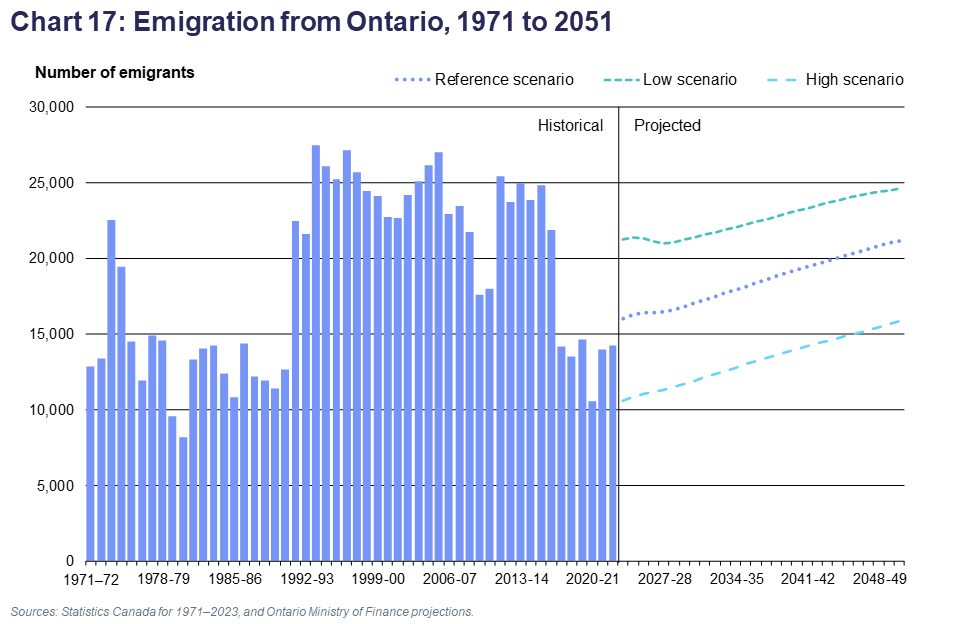

Chart 17: Emigration from Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This chart shows historical annual emigration levels from Ontario from 1971 to 2023, as well as projections of emigration under three scenarios to 2051. Over the historical period, emigration was very volatile, stating at about 13,000 in 1971-72, rising to 22,000 by 1973-74, falling to 8,000 in 1980-81, rising to peak at 27,000 in 1993-94 and hovering around 14,000 since 2017.

Emigration from Ontario is projected to increase from 16,000 in 2023-24 to 21,000 in 2050-51 in the reference scenario, from 11,000 to 16,000 in the high scenario, and from 21,000 to 25,000 in the low scenario.

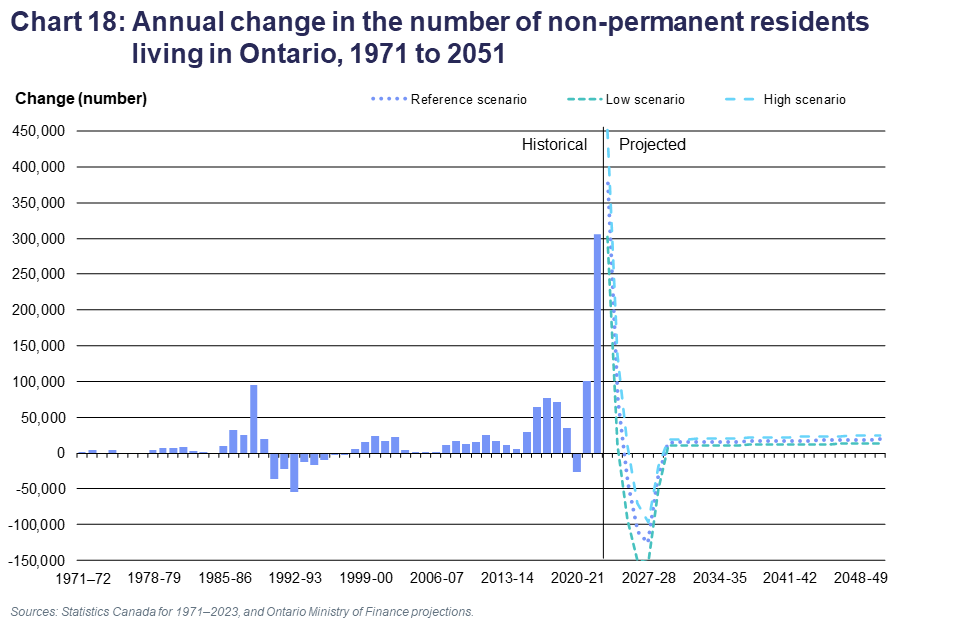

Chart 18: Annual change in the number of non-permanent residents living in Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This chart shows historical annual net gains in non-permanent residents in Ontario from 1971 to 2023 and projections under three scenarios to 2051. Over the historical period, the net gain was very volatile, starting with values close to zero in the early 1970s, with a peak of 95,000 in 1988-89, a deep through of -54,000 in 1992-93, and another high level in 2022-23 at 305,000.

The projected annual net gain of non-permanent residents in Ontario in the reference scenario is projected to fall from 377,000 in 2023-24 to annual declines from 2025 to 2029 and reach a net gain of 19,000 by 2050-51. In the high scenario, the net gain is projected at 540,000 in 2023-24, annual declines from 2026 to 2029, reaching a net gain 25,000 by 2050-51. In the low scenario a net gain of 302,000 is projected for 2023-24, annual declines from 2025 to 2029, reaching a net gain of 13,000 for 2050-51.

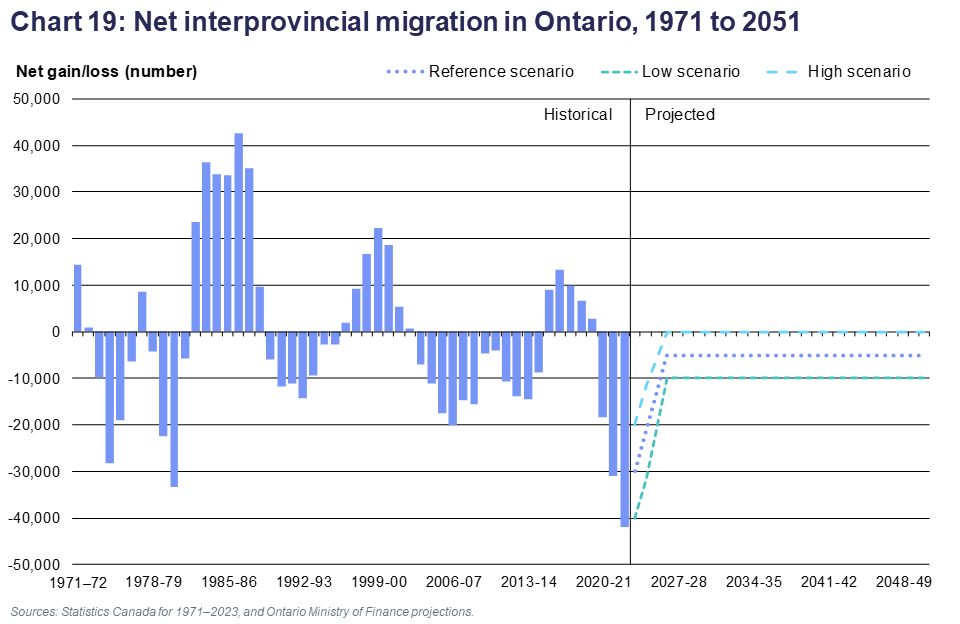

Chart 19: Net interprovincial migration in Ontario, 1971 to 2051

This chart shows the historical net interprovincial migration gain in Ontario from 1971 to 2023 and projections under three scenarios to 2051.

Over the historical period, net interprovincial migration followed cycles of net gains followed by net losses. Net interprovincial migration was generally negative during the 1970s, the late 1980s and early 1990s, and from 2003 to 2015. Positive cycles occurred during the early 1980s, the late 1990s, and from 2015 to 2020. In 2022-23, net interprovincial migration to Ontario was -42,000.

In the reference scenario, annual net interprovincial migration is set at -30,000 for 2023-24, rising to -5,000 by 2026-27, and remaining at -5,000 for the rest of the projections. In the high scenario, a net annual interprovincial migration is set at -20,000 for 2023-24, rising to zero by 2026-27, and remaining at that level for the rest of the projections. In the low scenario, net interprovincial migration is set at -40,000 for 2023-24, rising to -10,000 by 2026-27, and remaining at that level for the rest of the projections.

Map of Ontario census divisions

This map includes the following census divisions:

GTA:

- Toronto

- Durham

- Halton

- Peel

- York

Central:

- Brant

- Dufferin

- Haldimand–Norfolk

- Haliburton

- Hamilton

- Muskoka

- Niagara

- Northumberland

- Peterborough

- Simcoe

- Kawartha Lakes

- Waterloo

- Wellington

East:

- Ottawa

- Frontenac

- Hastings

- Lanark

- Leeds and Grenville

- Lennox and Addington

- Prescott and Russell

- Prince Edward

- Renfrew

- Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry

Southwest:

- Bruce

- Elgin

- Essex

- Grey

- Huron

- Chatham–Kent

- Lambton

- Middlesex

- Oxford

- Perth

Northeast:

- Algoma

- Cochrane

- Manitoulin

- Nippissing

- Parry Sound

- Greater Sudbury

- Sudbury

- Timiskaming

Northwest:

- Kenora

- Rainy River

- Thunder Bay

Return to map of Ontario census divisions

Related

Footnotes

- footnote[1] Back to paragraph Results are presented for Census years, which run from July 1 to June 30.

- footnote[2] Back to paragraph Based on the Pearsonian approach, a parametric model used to distribute estimated fertility rates by age of mothers.

- footnote[3] Back to paragraph Following the Lee-Carter method of mortality projection used to generate annual age-sex specific mortality rates. See Lee, Ronald D., and Carter, Lawrence, 1992. “Modeling and Forecasting the Time Series of U.S. Mortality,” Journal of the American Statistical Association 87, no 419 (September):659-71.