Recovery strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler

Read the recovery strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii), a species of bird at risk in Ontario.

Cover photo by Mike Burrell.

About the Ontario recovery strategy series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What’s next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk webpage.

Recommended citation

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared by the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. v + 5 pp. + Appendices.

© Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2016

ISBN 978-1-4606-8988-2 (HTML)

ISBN 978-1-4606-8992-9 (PDF)

Content (excluding the cover illustration and images in the appended federal documents) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Cette publication hautement spécialisée « Recovery strategies prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 », n'est disponible qu'en anglais en vertu du Règlement 411/97 qui en exempte l'application de la Loi sur les services en français. Pour obtenir de l'aide en français, veuillez communiquer avec recovery.planning@ontario.ca.

Acknowledgments

We thank Chris Risley of Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry for providing information that assisted in the development of this recovery strategy addendum.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Executive summary

Executive summary of Ontario’s recovery strategy

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) is listed as endangered on the SARO List. The species is also listed as endangered under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) in Canada in 2006 to meet its requirements under the SARA. Environment and Climate Change Canada also prepared an Action Plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Canada in 2016. Ontario hereby adopts the following under the ESA: 1) the federal recovery strategy, excluding sections 2.4 to 2.10, and 2) the federal action plan in full. The excluded sections of the federal recovery strategy contain content that is replaced or revised in the more up-to-date federal action plan. With the additions indicated below, these documents meet all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal action plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler published in 2016 provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal action plan be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA.

Since the publication of the federal recovery strategy, a breeding population of Kirtland’s Warbler has been discovered in eastern Ontario and additional observations have been made of the species in central Ontario, pending verification. These new locations should be considered in developing a habitat regulation for the species.

Executive summary of Canada’s recovery strategy

The Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) is designated as Endangered in Canada (COSEWIC 2000). Its global breeding range is confined to the state of Michigan, although a breeding pair was recorded near Barrie, Ontario, in 1945. Since then, nesting has not been confirmed in Canada, although singing males have been observed in suitable habitat during the breeding season. The Michigan population has recently expanded, birds are now also nesting in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and singing males have been located within 25 km of the Canadian border near Sault Ste. Marie, so it is possible that breeding pairs may be detected in Canada in the future.

Kirtland’s Warblers are habitat specialists. They prefer extensive tracts of early successional, densely stocked jack pine (Pinus banksiana). The main threats to Kirtland’s Warbler survival include fire suppression and vegetative succession, insufficient suitable habitat, and brood parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus ater).

The recovery of a viable population of Kirtland’s Warblers in Canada is considered feasible.

Recovery goals are:

- to determine if a breeding population exists in Canada; and

- to manage habitat at selected locations in Canada to encourage recovery of the species.

Numerical population targets will be identified once Kirtland’s Warbler reestablishment has occurred.

Between 2006 and 2011, recovery objectives are to complete surveys to detect the presence of an existing population, increase communication and stakeholder support, and manage habitat for Kirtland’s Warbler conservation. Two additional objectives are outlined if breeding is confirmed. These include identifying and protecting critical habitat and conducting an annual census. A number of recovery activities are outlined to fulfil these objectives, and criteria to evaluate recovery efforts and overall success are defined. Recovery actions that have already been undertaken mainly include survey work, although little surveying has been done in relation to the amount of potential habitat in Canada.

Because there has been no recent evidence of breeding documented in Canada, quantitative recovery goals cannot be set and critical habitat cannot be identified at this time. This strategy contains a brief description of habitat requirements for Kirtland’s Warblers (based on research in Michigan) and a schedule of studies to help identify their critical habitat in Canada.

An action plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler will be completed by November 2010. Critical habitat will be identified following confirmation of a breeding population in Canada, but this may not be possible by 2010.

Executive summary of Canada’s action plan for the species

The Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) is a globally rare songbird, listed as Endangered under Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act and also under the Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007. It breeds mainly in the United States, in the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of Michigan, and was recently discovered in Wisconsin. In Canada, the Kirtland’s Warbler has, in recent years, been confirmed nesting at one location, near Petawawa, Ontario. The Kirtland’s Warbler primarily breeds in large, even-aged stands of young Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana). In Canada, it is threatened by a reduction in habitat quality, and also by habitat loss and fragmentation.

The Recovery Strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii

Critical habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler is partially identified within this action plan. Critical habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler is based upon the recent occurrence of nesting pairs or singing males, as well as a vegetation community typically dominated by open Jack Pine woodland of a specific age, size, density, and cover. Examples of activities that are likely to destroy critical habitat are also described in this action plan. Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is working with the Department of National Defence (DND) at Garrison Petawawa to protect critical habitat, all of which is on federal lands.

Measures to be taken for Kirtland’s Warbler in Canada are divided into four broad categories: protection and management, monitoring and assessment, outreach and communication, and habitat restoration.

The potential socio-economic costs and benefits of implementing this action plan are also evaluated. Because the species is only known to occur on DND lands, the anticipated costs will largely be incurred by DND. Costs will generally be related to operational impacts of avoiding the destruction of critical habitat, and could be significant for both Garrison Petawawa locally and the Canadian Army nationally. Nonetheless, overall at a national scale, the economic and social costs incurred are expected to be moderate. The social and economic benefits of contributing to the successful recovery of one of the world’s rarest birds are difficult to quantify; it is clear, however, that Canada has a conservation responsibility for this species and the benefits of preserving a globally rare species in terms of biodiversity conservation are very high.

Adoption of federal recovery strategy and action plan

The Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA) requires the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry to ensure recovery strategies are prepared for all species listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List. Under the ESA, a recovery strategy may incorporate all or part of an existing plan that relates to the species.

The Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) is listed as endangered on the SARO List. The species is also listed as endangered under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment Canada prepared the Recovery Strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) in Canada in 2006 to meet its requirements under the SARA. Environment and Climate Change Canada also prepared an Action Plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Canada in 2016. Ontario hereby adopts the following under the ESA: 1) the federal recovery strategy, excluding sections 2.4 to 2.10, and 2) the federal action plan in full. The excluded sections of the federal recovery strategy contain content that is replaced or revised in the more up-to-date federal action plan. With the additions indicated below, these documents meet all of the content requirements outlined in the ESA.

Species assessment and classification

Table 1. Species assessment and classification of the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii). The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations within, and for other technical terms in this document.

| Assessment | Status |

|---|---|

| SARO list classification | Endangered |

| SARO list history | Endangered (2008), Endangered – Regulated (1977) |

| COSEWIC assessment history | Endangered (2000), Endangered (1999), Endangered (1979) |

| SARA schedule 1 | Endangered (2008) |

| Conservation status rankings | GRANK: G3G4, NRANK: N1B, SRANK: S1B |

Distribution, abundance and population trends

The federal recovery strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Appendix 1) provides a description of the known population and distribution of the Kirtland’s Warbler in Ontario up to 2006. Although there had been singing males observed in Ontario in the breeding season, minimal observations have been reported since a somewhat ambiguous report from Simcoe County in 1945 reported fledged young (Environment Canada 2006). In 2007 this changed when a Kirtland’s Warbler nest was discovered on Department of National Defence lands in Garrison Petawawa (formerly Canadian Forces Base Petawawa) in Renfrew County (Richard 2008). Since then, additional nests have been found and the population has persisted (Richard 2013a, 2013b, Environment and Climate Change Canada 2016).

Recently, Kirtland’s Warblers have been reported at three locations in central Ontario. A single singing male was detected on an automated recording device in Algoma District in June 2012 (Holmes et al. 2015), a singing male was heard and seen in Georgian Bay Township of Muskoka District in both 2014 and 2015 (Burrell and Charlton 2015) and a pair of Kirtland’s Warblers was observed in Parry Sound District in June 2015 (AECOM 2016).

If these reports are verified and meet the definition of element occurrences for Kirtland’s Warbler, they would be added to Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre database.

Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below will be one of many sources considered by the Minister, including information that may become newly available following completion of the recovery strategy, when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

The Critical Habitat section of the federal action plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler provides an identification of critical habitat (as defined under the SARA) (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2016). Identification of critical habitat is not a component of a recovery strategy prepared under the ESA. However, it is recommended that the approach used to identify critical habitat in the federal action plan be considered when developing a habitat regulation under the ESA. Pending verification, the new locations of Kirtland’s Warbler noted above, beyond what are currently proposed as critical habitat in the federal action plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler in Canada (Environment and Climate Change Canada 2016), should also be considered in developing a habitat regulation for this species.

Glossary

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC): The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO): The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that primarily conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. Ranks are determined by NatureServe and, in the case of Ontario’s S-rank, by Ontario’s Natural Heritage Information Centre. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is designated by a number from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

1 = critically imperilled

2 = imperilled

3 = vulnerable

4 = apparently secure

5 = secure

NR = not yet ranked

Element occurrence: The basic unit of record for documenting and delimiting the presence and extent of a species on the landscape. It is an area of land and/or water where a species is, or was, present, and which has practical conservation value.

Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA): The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

Species at Risk Act (SARA): The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List: The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

AECOM. 2016. Henvey Inlet Wind Energy Centre, Volume A: Environmental Assessment. Final Draft (January 2016). Unpublished report prepared by AECOM, Markham ON. 258 pp. [website accessed January 2016].

Burrell, M.V.A. and B.N. Charlton. 2015. Ontario Bird Records Committee Report for 2014. Ontario Birds 33:50-81.

Environment Canada. 2006. Recovery Strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vi + 23 pp.

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2016. Action Plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Ottawa. v + 20 pp.

Holmes, S.B., K. Tuininga, K.A. McIlwrick, M. Carruthers and E. Cobb. 2015. Using an integrated recording and sound analysis system to search for Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 129:115-120.

Richard, T. 2008. Confirmed occurrence and nesting of the Kirtland’s Warbler at CFB Petawawa: a first for Canada. Ontario Birds 26:2-15.

Richard, T. 2013a. Characterization of Kirtland’s Warbler Habitat on a Canadian Military Installation. Master’s thesis submitted to the Royal Military College of Canada. 116 pp.

Richard, T. 2013b. Kirtland’s Warbler at Garrison Petawawa: 2006-2013. Ontario Birds 31:148-159.

Appendix 1. Recovery strategy for Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) in Canada

Federal cover illustration: L.A. Messick courtesy of USDA Forest Service.

About the Species at Risk Act recovery strategy series

What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)?

SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is "to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity."

What is recovery?

In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species' persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured.

What is a recovery strategy?

A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage.

Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies - Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada - under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARA outline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Depending on the status of the species and when it was assessed, a recovery strategy has to be developed within one to two years after the species is added to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. Three to four years is allowed for those species that were automatically listed when SARA came into force.

What’s next?

In most cases, one or more action plans will be developed to define and guide implementation of the recovery strategy. Nevertheless, directions set in the recovery strategy are sufficient to begin involving communities, land users, and conservationists in recovery implementation. Cost-effective measures to prevent the reduction or loss of the species should not be postponed for lack of full scientific certainty.

The series

This series presents the recovery strategies prepared or adopted by the federal government under SARA. New documents will be added regularly as species get listed and as strategies are updated.

To learn more

To learn more about the Species at Risk Act and recovery initiatives, please consult the SARA Public Registry (http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/) and the Web site of the Recovery Secretariat (http://www.speciesatrisk.gc.ca/recovery/default_e.cfm).

Document information

Recommended citation

Environment Canada. 2006. Recovery Strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vi + 23 pp.

Additional copies

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SARA Public Registry.

Également disponible en français sous le titre « Programme de rétablissement de la Paruline de Kirtland (Dendroica kirtlandii) au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2006. All rights reserved.

ISBN 0-662-44249-0

Cat. no. En3-4/7-2006E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Declaration

This recovery strategy has been prepared in cooperation with the jurisdictions responsible for the Kirtland’s Warbler. Environment Canada has reviewed and accepts this document as its recovery strategy for the Kirtland’s Warbler, as required under the Species at Risk Act. This recovery strategy also constitutes advice to other jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved in recovering the species.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best existing knowledge and are subject to modifications resulting from new findings and revised objectives.

This recovery strategy will be the basis for one or more action plans that will provide details on specific recovery measures to be taken to support conservation and recovery of the species. The Minister of the Environment will report on progress within five years.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada or any other jurisdiction alone. In the spirit of the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, the Minister of the Environment invites all responsible jurisdictions and Canadians to join Environment Canada in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Kirtland’s Warbler and Canadian society as a whole.

Responsible jurisdictions

Environment Canada – Ontario Region

Parks Canada Agency

Government of Ontario

Authors

H.J. Bickerton, Biologist, Ottawa, Ontario

- Tuininga, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region

- Coulson, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Pembroke

- Aird, Faculty of Forestry and Centre for Environment, University of Toronto

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Madeline Austen, Heather Dewar, Paul Aird, Irene Bowman, and Rick Pratt for developing the draft National Recovery Plan for Kirtland’s Warbler, January 20, 2000 on which this recovery strategy was based. The following people provided valuable information on the ecology and conservation of the Kirtland’s Warbler as well as useful comments on earlier drafts of this recovery strategy: Robin Bloom, Mike Cadman, Elaine Carlson, Tracey Casselman, Andre Dupont, Phil Huber, Burke Korol, Jan McDonnell, Chris Risley, Steve Sjogren, Don Sutherland and several anonymous reviewers. Thanks are extended to Paul Aird and Mike Petrucha for providing occurrence data. Thanks also to the US Department of Agriculture, Forestry Service for the cover drawing and the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Division for providing the breeding season distribution map. Christine Vance prepared the Canadian distribution evidence map. Thanks also to Canadian Wildlife Service, Habitat Conservation Section for their advice and Canadian Wildlife Service, Recovery Section for their advice and efforts in preparing this document for posting.

Strategic environmental assessment

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts on non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below.

This recovery strategy will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the recovery of the Kirtland’s Warbler. The potential for the strategy to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered. The SEA concluded that this strategy will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant adverse effects.

Residence

SARA defines residence as: a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar area or place, that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more individuals during all or part of their life cycles, including breeding, rearing, staging, wintering, feeding or hibernating [Subsection 2(1)].

Residence descriptions, or the rationale for why the residence concept does not apply to a given species, are posted on the SARA public registry.

Preface

The Kirtland’s Warbler was listed as endangered under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in June 2003. It is also a migratory bird protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 and is under the management jurisdiction of the federal government. The Species at Risk Act (SARA, Section 37) requires the competent minister to prepare recovery strategies for listed extirpated, endangered or threatened species. Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region, Environment Canada, led the development of this recovery strategy in cooperation with the Province of Ontario. All responsible jurisdictions reviewed and approved the strategy, which covers the five-year period from 2006 to 2011. This strategy meets SARA requirements in terms of content and process (Sections 39–41).

Executive summary

The Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) is designated as Endangered in Canada (COSEWIC 2000). Its global breeding range is confined to the state of Michigan, although a breeding pair was recorded near Barrie, Ontario, in 1945. Since then, nesting has not been confirmed in Canada, although singing males have been observed in suitable habitat during the breeding season. The Michigan population has recently expanded, birds are now also nesting in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and singing males have been located within 25 km of the Canadian border near Sault Ste. Marie, so it is possible that breeding pairs may be detected in Canada in the future.

Kirtland’s Warblers are habitat specialists. They prefer extensive tracts of early successional, densely stocked jack pine (Pinus banksiana). The main threats to Kirtland’s Warbler survival include fire suppression and vegetative succession, insufficient suitable habitat, and brood parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus ater).

The recovery of a viable population of Kirtland’s Warblers in Canada is considered feasible.

Recovery goals are:

- to determine if a breeding population exists in Canada; and

- to manage habitat at selected locations in Canada to encourage recovery of the species.

Numerical population targets will be identified once Kirtland’s Warbler reestablishment has occurred.

Between 2006 and 2011, recovery objectives are to complete surveys to detect the presence of an existing population, increase communication and stakeholder support, and manage habitat for Kirtland’s Warbler conservation. Two additional objectives are outlined if breeding is confirmed. These include identifying and protecting critical habitat and conducting an annual census. A number of recovery activities are outlined to fulfil these objectives, and criteria to evaluate recovery efforts and overall success are defined. Recovery actions that have already been undertaken mainly include survey work, although little surveying has been done in relation to the amount of potential habitat in Canada.

Because there has been no recent evidence of breeding documented in Canada, quantitative recovery goals cannot be set and critical habitat cannot be identified at this time. This strategy contains a brief description of habitat requirements for Kirtland’s Warblers (based on research in Michigan) and a schedule of studies to help identify their critical habitat in Canada.

An action plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler will be completed by November 2010. Critical habitat will be identified following confirmation of a breeding population in Canada, but this may not be possible by 2010.

1. Background

1.1 Species assessment information from COSEWIC

Date of the assessment: May 2000

Common name: Kirtland’s Warbler

Scientific name: Dendroica kirtlandii

COSEWIC status: Endangered

Reason for designation: This is a globally endangered species. There are no recent breeding records in Canada, but singing males are occasionally recorded in suitable breeding habitat in Ontario.

Canadian occurrence: Ontario

COSEWIC status history: Designated Endangered in April 1979. Status re-examined and confirmed in April 1999 and in May 2000. Last assessment based on an existing status report.

1.2 Description

The Kirtland’s Warbler is a medium-sized, omnivorous songbird in the Family Parulidae (North American wood-warblers). The adult male Kirtland’s Warbler has a bluish-grey head and back that is streaked with black, a lemon yellow front, and black streaks or spots on the sides. The eyelids are white, forming an almost complete eye ring, and indistinct whitish wing bars may also be evident. Adult females resemble males, but with duller plumage and paler underparts. Immature females are generally browner overall. Kirtland’s Warblers frequently pump their tails. The song of the male Kirtland’s Warbler is a loud, emphatic series of notes. Illustrations and further descriptions may be found in Mayfield (1992), Walkinshaw (1983), and standard field guides.

1.3 Populations and distribution

The Kirtland’s Warbler is one of the world’s most critically endangered species, with a global rank of G1

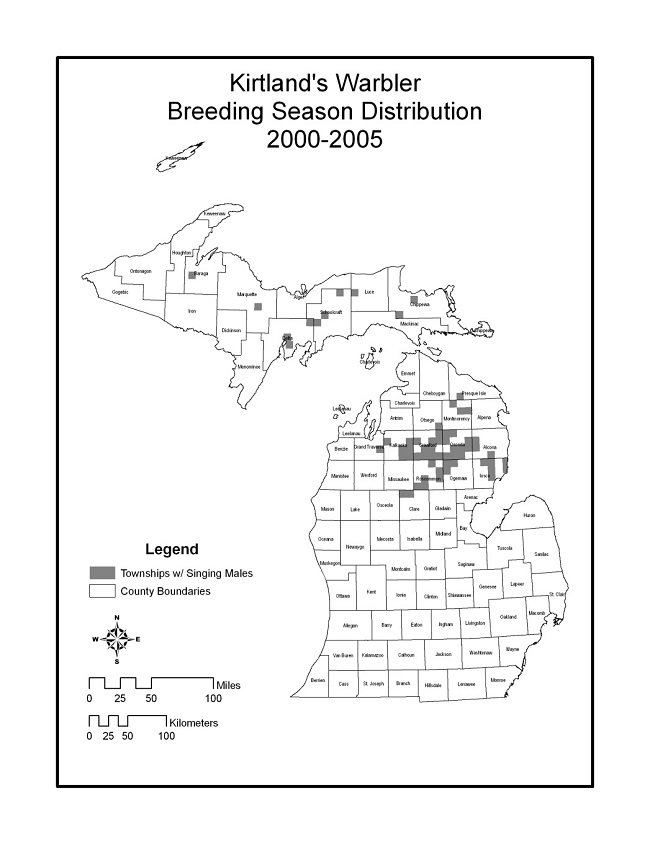

Figure 1. Kirtland’s Warbler breeding season distribution.

Enlarge Figure 1. Kirtland’s Warbler breeding season distribution.

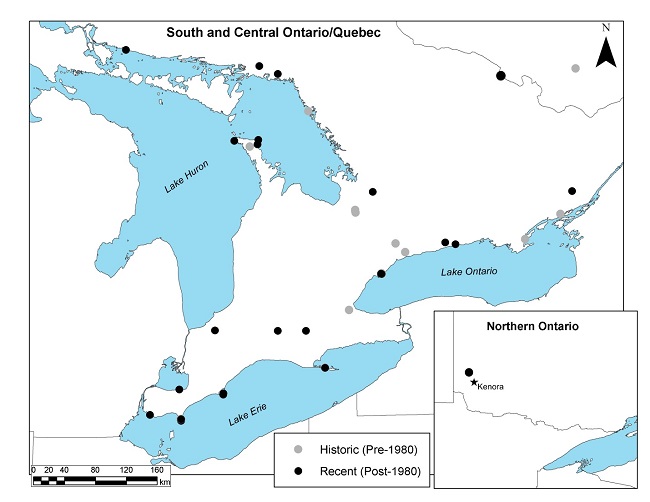

The single breeding record documented for Canada is from the Midhurst (Barrie) area in Ontario in 1945 (Speirs 1984), although there is some ambiguity regarding this record (Natural Heritage Information Centre 2005). Kirtland’s Warblers may have been nesting in the Petawawa area in Ontario in the 1800s and early 1900s, and possibly elsewhere in Canada (Harrington 1939; COSEWIC 2000). One singing male was recorded on the Québec side of the Ottawa River, near Kazabazua, Québec, in 1978 (COSEWIC 2000). Singing males were seen and heard regularly at Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Petawawa, near Petawawa, Ontario, during the summer of 1916, and a male Kirtland’s Warbler was also reported in the same area on June 5, 1939 (Harrington 1939). Singing males have been reported in early successional pine habitat in Ontario on at least eight subsequent occasions, the most recent being the sighting of three individuals at CFB Petawawa in June 2006. However, none of these males was believed to be accompanied by a female. It is possible that birds in larger, less accessible patches in this area have gone undetected (COSEWIC 2000) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Distribution evidence for the Kirtland’s Warbler in Canada.

Enlarge Figure 2. Distribution evidence for the Kirtland’s Warbler in Canada.

Multiple records at the same location are not shown.

Sightings have been reported in Canada from Minaki, Ontario, east to Kazabazua, Québec. The majority of the 76 records for this species in Canada, between 1900 and 2006 and principally in Ontario, are of spring migrants, with some summer reports (June to mid-July) of singing males and some fall migrants (Aird and Pope 1987; COSEWIC 2000; P.Aird pers comm. 2006; Petrucha and Sykes, 2006). Although there has generally been at least one sighting of the Kirtland’s Warbler each year in Ontario since 1990, there is no trend evident in the number of sightings of singing males. Kirtland’s Warblers were not documented as breeding in any region of Ontario during the recent five-year (2001–2005) Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas project (Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas 2005).

The global breeding distribution of the Kirtland’s Warbler is therefore confined to the United States. However, based on the expansion of the Michigan population and increasing numbers of singing males reported in Michigan and Wisconsin, some within 25 km of the Canadian border near Sault Ste. Marie, it is possible that breeding may be reported in Canada in the future.

1.4 Needs of the Kirtland’s Warbler

1.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

The Kirtland’s Warbler is a habitat specialist. In Michigan, essential habitat requirements include even-aged stands of jack pine over 32 ha in size (Mayfield 1953) and created by wildfire or specially designed plantations that mimic wildfires. Jack pine stands larger than 80 ha are optimal breeding habitats, indicated by improved nesting success in these stands. Anderson and Storer (1976) found that 90% of nests that fledged Kirtland’s Warblers were in stands larger than 80 ha. Optimal habitat also consists of dense stands of jack pine (minimum 3500 stems/ha) interspersed with small openings, which produces high foliage volume and 35–65% canopy cover (Probst 1988; Kepler et al. 1996). Studies suggest higher nest success in dense, scattered patches of trees 1.5–5 m tall (or 7–20 years old), which provide adequate branch cover near the ground for nests; dry, well-drained, sandy soils; and ground cover composed of plants such as blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium, V. myrtilloides), bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi), bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), service-berry (Amelanchier spp.), sand cherry (Prunus pumila), sweet fern (Comptonia peregrina), grasses (Andropogon spp.), sedges (Carex spp.), and goldenrods (Solidago spp.).

Plantations of jack pine and, rarely, red pine (Pinus resinosa) also provide suitable habitat for Kirtland’s Warblers on the breeding grounds (Weinrich 1994). In recent years, more than 90% of Kirtland’s Warblers nested in jack pine plantations specifically established for the species (P. Huber, pers. comm., 2006). Birds nesting in plantations can produce numbers of young comparable to those in naturally regenerated burn areas (Bocetti 1994).

With an average territory size estimated at about 15 ha (38 acres) per singing male, successful breeding of only 25 pairs is estimated to require the maintenance of roughly 375 ha (950 acres) of suitable habitat. Recovery efforts in Michigan are designed to provide a minimum of 15 200 ha (38 000 acres) at all times, involving rotational harvest management of approximately 76 000 ha (190 000 acres) of jack pine (Olson 2002).

In spite of the specific requirements listed above, the required amount and quality of available habitat can be difficult to assess accurately. Areas of apparently high-quality habitat may not be occupied, and occupied habitat may not appear to be ideal, even to an experienced observer (Mayfield 1992). Other factors, including microclimate and specific structural features, may be more important than is currently understood. Further details on habitat requirements can be found in the literature (Wood 1904, 1926; Barrows 1921; Leopold 1924; Wing 1933; Mayfield 1953, 1960, 1962; Line 1964; Anderson and Storer 1976; Chamberlain 1978; Buech 1980; Harwood 1981; Ryel 1981; Wright and Bailey 1982; Probst 1986; Probst and Hayes 1987).

A study of the diet of the Kirtland’s Warbler through fecal analysis revealed the major food items as spittlebugs and aphids (Homoptera; in 61% of samples), ants and wasps (Hymenoptera; 45%), blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium; 42%), beetles (Coleoptera; 25%), and moth larvae (Lepidoptera; 22%) (DeLoria-Sheffield et al. 2001). Presumably, sufficient quantities of these foods must be present for habitat to be suitable.

Sites surveyed in Ontario in the 1970s with potentially suitable habitat were not considered to be optimal habitat by Michigan standards: trees were taller than 6 m, and plant associations were different from those found in Michigan (Chamberlain 1978). However, work in 2003 in the Thessalon area in Ontario found plant associations and habitat very similar to those in Michigan’s jack pine barrens, with coarse sandy soils and ground cover dominated by low bush blueberry (V. angustifolium) and various grasses and sedges (Bloom 2003). Still, the actual amount of survey work completed in Ontario in relation to potential suitable habitat available is very small (P. Aird, pers. comm., 2006). In Ontario, singing males have been found in jack pine stands or plantations of more than 20 ha on well-drained sands or on shallow soils covering bedrock (Aird and Pope 1987). Kirtland’s Warblers have also been found in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) plantations on at least one occasion in Simcoe County, Ontario, on May 16–21, 1964 (Devitt 1967).

Kirtland’s Warblers are neotropical migrants that winter in the Bahamas, where they prefer areas of low, sparse vegetation (Mayfield 1972, 1996). Most of the islands are covered with broad-leaved scrub, and the northernmost islands have extensive pinelands. Most records were on islands that support open woodlands of Caribbean pine (Pinus caribaea) (Haney et al. 1998). Periods of degradation and recovery of pine ecosystems in the Bahamas may be related to periods of decline and recovery of Kirtland’s Warbler populations, and it has been suggested that winter habitat should be considered in conservation planning for the species (Haney et al. 1998). However, habitat availability on wintering grounds has not generally been thought to be a limiting factor (Sykes and Clench 1998).

1.4.2 Ecological role

The diet of the Kirtland’s Warbler includes a variety of insects representing a number of different orders (DeLoria-Sheffield et al. 2001), but there has been no research to determine the specific ecological effect of this warbler on populations of individual insect taxonomic groups. Blueberries (V. angustifolium) are also a major component of the Kirtland’s Warbler diet, and it is possible that birds assist in dispersing seeds into suitable habitat.

Documented predators of Kirtland’s Warbler adults, nestlings, and eggs in Michigan include Blue Jay (Cyanocitta cristata), thirteen-lined ground squirrel (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus), raccoon (Procyon lotor), striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis), domestic cat, and garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis)(Walkinshaw 1983). It is also suspected that red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) and crows (Corvus spp.) may predate Kirtland’s Warbler eggs and nestlings in Michigan, but there has been no need to control predators to date (Huber et al. 2001).

1.4.3 Limiting factors

Some characteristics of Kirtland’s Warbler biology noted from Michigan populations that could limit recovery in Canada include:

- an extremely narrow preference for early successional and densely stocked jack pine. Suitable jack pine habitat created by wildfires due to fire suppression necessitates continued management (e.g. specially designed plantations). Suitable early successional habitats are dispersed and are possibly limiting in some parts of Ontario;

- a preference for nesting territories within expansive tracts of suitable habitat;

- temporary occupation of habitat (8–15 years) due to early successional habitat preferences (Probst 1986);

- a high level of susceptibility to parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbirds in nesting areas (Mayfield 1977; Harwood 1981); and

- dispersal characteristics. Young of the year typically disperse widely in search of new territories. Although dispersal may establish birds on new territories, dispersed singing males may have little chance of finding a mate in areas where the density of this species is very low (Mayfield 1983).

1.5 Threats

There are three main threats to the Kirtland’s Warbler. These are all well-demonstrated threats to the Michigan population. Further survey work is necessary to determine the extent to which fire suppression and forest succession and lack of suitable habitat are factors in Ontario. Cowbird parasitism is a significant problem in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, but control has not been necessary in the Upper Peninsula (S. Sjogren, pers. comm., 2006). If a population is detected in Ontario, control may be necessary only in the south, where cowbirds are more common and the habitat is more fragmented.

1.5.1 Fire suppression and forest succession

Jack pine cones normally remain closed until exposed to heat from wildfires, and stand densities are higher following fire than following standard forest harvest practices (Olson 2002). Natural regeneration by wildfire also creates thickets and openings, favoured by breeding female warblers for nest site selection (Bocetti 1994). Optimal habitat was probably most extensive in the late 19th century when forest fires frequently followed extensive logging (Mayfield 1960). Fire suppression in the 20th century has greatly reduced available habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler in both Ontario and Michigan (COSEWIC 2000).

A similar habitat structure can be mimicked by specific rotational harvest prescriptions and natural jack pine regeneration, with or without direct seeding or establishment of jack pine plantations (S. Sjogren, pers. comm., 2006). However, occupation of successional habitat by this species is still limited to 8–15 years (Probst 1986). Rotational harvest of large patches within a very large total area is therefore required to provide long-term occupancy of the Kirtland’s Warbler in an area (see section 1.4.1). A broad and potentially complex ecosystem approach that considers not only forestry practices, but also physical site factors, including microclimate and moisture, will be needed to manage large areas of habitat for the species (Kashian and Barnes 2000).

1.5.2 Lack of suitable habitat

Sufficiently large tracts of high-density, early successional jack pine forest with optimal understorey structure and composition may be limiting the establishment of Kirtland’s Warblers in some parts of Ontario. However, patches of suitable habitat have been documented, and there are large tracts of jack pine habitat across Ontario that need to be surveyed, including,Thessalon, the Petawawa area, the area between Cartier and Lake Wanapitei, the region between Chapleau and Gowganda, Manitoulin Island, and the Bruce Peninsula (Austen et al. 1993; Bloom 2003; P. Aird, pers. comm., 2005). There is now considerable evidence that a lack of suitable habitat was limiting the small but stable Michigan population prior to a vast wildfire in the 1980s (Probst and Weinrich 1993; Kepler et al. 1996). It has also been demonstrated that the pairing success rate of the Kirtland’s Warbler is lower in habitats of marginal quality (Probst and Hayes 1987).

1.5.3 Brood parasitism by Brown-headed Cowbird

Brood parasitism by the Brown-headed Cowbird has been shown to reduce both hatchling and fledgling success in Michigan populations (Kelly and DeCapita 1982; Walkinshaw 1983). Through the 1960s and 1970s, a steep decline in the Kirtland’s Warbler population led to the confirmation that more than 70% of warbler nests were parasitized, reducing the production of young to fewer than one young per pair per year (Ryel 1981). Cowbird control began in 1972 and reduced parasitism to about 3% or negligible levels (Kelly and DeCapita 1982) and increased productivity to an average of nearly three fledged young per pair per year (Kelly and DeCapita 1982; Walkinshaw 1983).

If there is an undetected breeding population of the Kirtland’s Warbler in Canada, it is possible that cowbird parasitism is a threat to nesting success, and an assessment may eventually be needed.

1.5.4 Other

Forest management practices that do not consider the Kirtland’s Warbler’s specialized habitat requirements may inadvertently cause jack pine forests to become unsuitable. Conversion of jack pine to less preferred species, fragmentation of jack pine by harvesting in small blocks when large blocks are available, and planting unsuitable stocking densities may all threaten occupation by the Kirtland’s Warbler.

1.5.5 Actions already completed or under way

A long-term, multiagency recovery program has been extremely successful in Michigan (Solomon 1998). With over 800 published works on the Kirtland’s Warbler, sustained census, management, and research activities have been well documented in the literature (Mayfield 1992). In 2003, a joint recovery meeting was held with members of several U.S. recovery teams and representatives from the Canadian Wildlife Service (CWS). Opportunities for collaboration and joint recovery efforts for the Kirtland’s Warbler were discussed (R. Bloom, pers. comm., 2005).

In Canada, recovery actions have been limited mainly to survey work. There have been several targeted search efforts to detect breeding of the Kirtland’s Warbler in the past decade. In response to a report of a Kirtland’s Warbler sighting on July 4, 1997, in the Thessalon area, a survey for the species was conducted in this vicinity in 1999, but without success (Knudsen 1999).

This general area was later used to develop a site prioritization scheme using spatial data. Areas of suitable jack pine habitat in northern Ontario are potentially very large, and a prioritization method was developed to help focus future survey effort. Spatial information (e.g. pine cover, successional stage, soils) was used to evaluate sites for likelihood of dispersal and to set priorities for monitoring. Sections of this area were then surveyed by air by CWS staff, accompanied by American researchers (Bloom 2003). Although the project was not finalized, the mapping to date could be used to intensify aerial and ground surveys, initiate a monitoring program, or ground-truth sites for habitat suitability using established field methods (e.g. Bocetti 1994).

Targeted search efforts have also been undertaken in the Pembroke area. In 2002 and 2003, staff from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) and CFB Petawawa searched suitable habitat unsuccessfully. Since 2003, survey work has been continued by CFB Petawawa, and OMNR staff have begun to focus search efforts on other areas of suitable habitat in Renfrew County. Suitable habitat on CFB Petawawa was searched as part of a larger inventory of species at risk commissioned by the Base in 2006. Three singing males were located in June 2006 and one was eventually banded and released.

Searches have been undertaken annually in suitable habitat near Orillia, where a singing male was located in 1986, and over the past decade in the Chapleau–Cartier area, on the Bruce Peninsula, and on Manitoulin Island. Still, of the entire range of jack pine across Ontario, only a very small percentage has been surveyed. To date, no breeding pairs have been located (P. Aird, pers. comm., 2005).

Periodic sightings of migrant Kirtland’s Warblers by Ontario birders are generally reported to one or more of the following: the Ontario Field Ornithologists listserv (ontbirds@hwcn.org), Ontario Bird Records Committee, the Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre, Bird Studies Canada, the Kirtland’s Warbler Recovery Team, or the Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas project.

1.5.6 Knowledge gaps

Despite substantial research on this species, several knowledge gaps remain for the global population of the Kirtland’s Warbler. These include population responses to habitat change and foraging ecology, migration routes, winter habitat requirements, and the potential role of global climate warming on jack pine habitats (Woodby et al. 1989; Olson 2002).

The most urgent knowledge gaps in Canada are related mainly to distribution, location, and availability of suitable habitat. If the Kirtland’s Warbler is reconfirmed as breeding in Canada, the following areas will also require research:

- the extent of cowbird parasitism;

- habitat characteristics (including a comparison with habitat in Michigan);

- recruitment levels (nesting and fledging success);

- dispersal tendencies;

- site fidelity;

- competing species and predators; and

- possible management requirements.

2. Recovery

2.1 Rationale for recovery feasibility

Recovery of Kirtland’s Warblers in Canada is considered biologically and technically feasible.

First, an expanding source population exists in nearby Michigan. As the Michigan population is increasing, available territories may be reaching their carrying capacity, and juvenile males may disperse more widely to reach new territories. It is increasingly possible that a nesting pair of Kirtland’s Warblers will become established in Ontario. Breeding was confirmed only through intensive searches in the Michigan Upper Peninsula in 1995 (Probst et al. 2003). Singing males have been documented less than 25 km from the Canadian border near Sault Ste. Marie (S. Sjogren, pers comm., 2006). Dispersal distances of juvenile males of up to 350 km have been reported, and large water bodies do not appear to present a barrier (Probst et al. 2003). The expansion of the Michigan population to the state’s Upper Peninsula provides evidence that the species has the capability to disperse and establish successfully where conditions are favourable.

Second, it is likely that there is sufficient habitat to establish an initial population in Ontario and ample habitat that could be managed to sustain a population over time. In 2005, 90% of Michigan’s Kirtland’s Warblers nested in jack pine plantations established specifically for the species, suggesting that active management can be instrumental in recovery success (P. Huber, pers. comm., 2006).

Third, the U.S. experience has demonstrated that it is possible to reduce threats enough for populations to recover. Evidence suggests that it would be possible, with sufficient resources, to reduce the probable threats in Ontario, mainly through the use of specialized forestry prescriptions, reducing cowbird populations, and limiting site access, if necessary. Finally, these and other successful recovery techniques have been well documented in publications and through contact with the U.S. recovery team and other specialists (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2005).

2.2 Recovery goals

The recovery goals are:

- to determine if a breeding population exists in Canada; and

- to manage habitat at selected locations in Canada to encourage the recovery of the species.

Establishing a numerical population target and specific geographic distribution goal is not currently possible in the absence of confirmed breeding of Kirtland’s Warblers in Canada. If a breeding population is discovered, sufficient monitoring and research should be undertaken in order to determine reasonable population and distribution goals within five years. Although a breeding population has not yet been detected in Canada, breeding was only relatively recently confirmed in the Michigan Upper Peninsula, and the Michigan population reached a record high of 1478 singing males in 2006. For these reasons, habitat should be managed in Ontario to support potential further expansion of the global range of the Kirtland’s Warbler into Canada.

2.3 Recovery objectives

The following recovery objectives will be addressed between 2006 and 2011:

- Identify, survey, and map suitable and potentially suitable habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler.

- Follow up on breeding evidence for the species in Canada, particularly in Ontario.

- Achieve a high degree of interorganizational commitment and sustained cooperative management of the recovery program among responsible and interested agencies and organizations — e.g. CWS, OMNR, the Department of National Defence (DND), forestry companies, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service.

- Encourage the maintenance and/or improvement of large stands of appropriately stocked jack pine in appropriate areas of Ontario through the forest management planning process.

- Ensure that landowners, other affected groups (e.g. resource-use companies), and the general public are aware of and consider the needs of the species.

A breeding population may not be located prior to 2010; therefore, the following objectives may not be addressed before that time:

- Identify and protect critical habitat.

- Conduct an annual census, and collect information on breeding habitat characteristics and threats.

Without a coordinated survey effort, breeding Kirtland’s Warblers are much less likely to be documented in Canada. Targeted surveys to locate and map suitable habitat and breeding populations are critical, because many areas of suitable habitat are difficult to access. Documentation of the population’s expansion into Michigan’s Upper Peninsula and Wisconsin was made possible through intensive annual searches over two decades by staff from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the USDA Forest Service (Probst et al. 2003).

Encouraging early communication between organizations and agencies, including federal and provincial government agencies as well as forest licensees, will help to create support for and awareness of Kirtland’s Warbler conservation requirements. In the event that a population is discovered, preexisting awareness may speed recovery efforts. The importance of cooperation should not be underestimated. A high degree of interagency commitment, early consensus on science-based recovery goals, and sustained cooperative management in Michigan’s Kirtland’s Warbler recovery program are regarded as major reasons for the remarkable recovery of the species in the United States (Solomon 1998).

Following confirmation of breeding, site protection is critical to ensure breeding success. The Kirtland’s Warbler is an extremely rare bird and is likely to generate considerable interest within the Ontario naturalist and birding communities. However, human disturbance needs to be minimized to ensure breeding success. An annual census, threat identification, and habitat research will help to assess recovery targets, threats, and management needs specific to a Canadian population. Communication with landowners, land managers, and other affected groups will encourage recovery success through stewardship.

2.4 Approaches recommended to meet recovery objectives

Strategies will include habitat and population surveys to identify potential breeding habitat and detect breeding birds, communication, and habitat management, as required. If breeding is confirmed, strategies will include habitat protection, monitoring, research, habitat management, communication, and education. Habitat management will utilize techniques and expertise documented in Michigan and developed in Canada. The results of habitat and population surveys will be used to determine the need for and timing of habitat management. Habitat management may be implemented prior to the detection of a Canadian population to encourage the establishment of and to benefit the global population.

2.4.1 Recovery planning table

Table 1. Strategies to effect recovery.

| Priority | Objective No. | Broad Approach/ Strategy | Threat addressed | General steps | Outcomes (measurable targets) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 1, 2 | Survey | N/A |

|

|

| Low | 1 | Research | N/A |

|

|

| Moderate | 3 | Communication | N/A |

|

|

| Upon breeding: High | 6 | Habitat protection | N/A |

|

|

| Upon breeding: High | 6, 7 | Monitoring | N/A |

|

|

| Upon breeding: High | 6, 7 | Research | All |

|

|

| Moderate | 4, 6, 7 | Habitat management | All |

|

|

| Moderate | 5 | Communication | All |

|

|

| Moderate | 5 | Education | All |

|

|

2.5 Critical habitat

2.5.1 Identification of critical habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler

Critical habitat is defined as "the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species" (Species at Risk Act, Statutes of Canada 2002, c. 29, s. 2). Critical habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler in Canada can be fully identified only once evidence of breeding is documented. Once breeding is documented, a method to locate and identify critical habitat characteristics in Ontario will be determined (see section 2.5.2 below).

2.5.2 Schedule of studies

Table 2. Schedule of studies.

| Targeted completion date | Research required | Anticipated benefit |

|---|---|---|

| 2006–2009 | Complete surveys and ground-truthing wherever suitable habitat is found, including Thessalon, Chapleau/Gowganda, Cartier/Lake Wanapitei, Petawawa, Manitoulin Island, the Bruce Peninsula, and Barrie/Orillia | Provide focus for survey and monitoring efforts, coordinate data |

| 2007–2011 | Select high-potential sites and monitor annually | Locate breeding populations |

| 2006–2011 | Continue to undertake surveys and document suitable habitat in other areas of Ontario | Locate breeding populations |

| Within one season of breeding confirmation | Determine a method to locate and identify critical habitat and complete mapping | Map critical habitat for known breeding occurrences |

| Within one season of breeding confirmation | Describe habitat in Canadian breeding locations: vegetation communities, density and cover, other habitat features, etc. | Obtain site-specific habitat information; inform management |

| Annually upon breeding confirmation | Complete annual census of Canadian population | Set population targets for recovery in Canada |

| Upon breeding confirmation | Completely identify potential critical habitat | Critical habitat identified |

2.6 Existing and recommended approaches to habitat protection

Lack of knowledge about the location of any Kirtland’s Warbler habitat precludes any site-specific recommendations for habitat protection. Areas located during surveys that fit the habitat attributes for the Kirtland’s Warbler (or areas that could be managed to fit these attributes) should be considered as a high priority for stewardship. Once breeding evidence is found and critical habitat can be identified (as above), land ownership will be identified and appropriate effective protection methods determined. Development of conservation agreements will be favoured.

2.7 Performance measures

Recovery will be considered successful if a breeding population is discovered in Canada and appears to be increasing in number and/or distribution within the next five years. Clearly, this depends on the arrival or discovery of breeding birds in Canada.

If targeted reconnaissance surveys have been undertaken, incidental reports have been investigated, the Michigan population continues to increase, and no breeding birds have yet been discovered in Canada, a reevaluation of the recovery objectives should be undertaken in five years to determine whether habitat is limiting the establishment of the Kirtland’s Warbler.

If a breeding population has been detected, other indicators of success include:

- success at protecting breeding site(s), as required, through communication, stewardship, and legislative tools available;

- completion of annual census and banding;

- completion of site-based research, especially to determine threats to the Canadian population;

- completion of a management plan for the site(s);

- status of management actions (e.g. rotational harvest, cowbird control); and

- extent of awareness of landowners, managers, and the general public, and their involvement in the recovery process.

2.8 Effects on other species

The recovery activities outlined for the Kirtland’s Warbler (i.e. continued surveys) will enable further information to be gathered on common species associates in migratory or breeding habitats for Kirtland’s Warblers in Ontario. Negative impacts on other non-target species will be limited. If management activities are undertaken, impacts on non-target species will be assessed and mitigating measures considered. If other species at risk are found to be present within an area identified for management, the respective recovery teams will be consulted to determine the probability of impact on the species and, if possible, how to manage activities for the benefit of all species within the ecosystem.

2.9 Recommended approach for recovery implementation

The Kirtland’s Warbler is being considered in a single species recovery strategy because of its specialized habitat and management requirements. However, there is potential to incorporate Kirtland’s Warbler recovery with other conservation efforts. In Michigan, species found in Kirtland’s Warbler habitat include Vesper Sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus), Chipping Sparrow (Spizella passerina), Brown Thrasher (Toxostoma rufum), Nashville Warbler (Vermivora ruficapilla), Yellow-rumped Warbler (Dendroica coronata), Hermit Thrush (Catharus guttatus), Clay-colored Sparrow (Spizella pallida), Black-capped Chickadee (Poecile atricapillus), Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis), Sandhill Crane (Grus canadensis), and Sharp-tailed Grouse (Tympanuchus phasianellus) (Mayfield 1960; anonymous reviewer, pers. comm., 1999; S. Sjogren, pers. comm., 2006). The U.S. Kirtland’s Warbler program, although focused on a single species, incorporates an ecosystem approach to the management of the jack pine community of the dry sand plains in Michigan (Probst and Ennis 1989; Kepler et al. 1996). Because Kirtland’s Warblers benefit from large forest tracts (Anderson and Storer 1976; Mayfield 1993; Sykes 1997), recovery actions may also benefit other species with similar requirements. Members of the U.S. Kirtland’s Warbler Recovery Team provided valuable input to this recovery strategy, and several are also interested in assisting with survey work in Canada. Further and more coordinated cooperation with the U.S. Kirtland’s Warbler Recovery Team should be pursued.

There may be an opportunity to incorporate the Kirtland’s Warbler recovery activities into future species at risk work at CFB Petawawa.

2.10 Statement of when one or more action plans in relation to the recovery strategy will be completed

An action plan will be completed for the Kirtland’s Warbler by November 2010. It is anticipated that the Recovery Team will oversee the recovery strategy and action plan.

3. References

Aird, P. and D. Pope. 1987. Kirtland’s Warbler. Pp. 388–389 in: Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Ontario (M.D. Cadman, P.F.J. Eagles, and F.M. Helleiner, Eds.). University of Waterloo Press, Waterloo, Ontario.

Anderson, W.L. and R.W. Storer. 1976. Factors influencing Kirtland’s Warbler nesting success. Jack-Pine Warbler 54:105–115.

Austen, M. 1993. National Recovery Plan for Kirtland’s Warbler. Draft 2. Report prepared with input from Kirtland’s Warbler Recovery Team for The Endangered Species Recovery Fund, April 8, 1993.

Barrows, W.B. 1921. New nesting areas of Kirtland’s Warbler. Auk 38:116–117.

Bloom, R. 2003. Identification of Potential Kirtland’s Warbler Habitat in Ontario. Unpublished report to Environment Canada, Ontario Region.

Bocetti, C.I. 1994. Density, Demography, and Mating Success of Kirtland’s Warblers in Managed and Natural Habitats. Ph.D. Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio.

Botkin, D.B., D.A. Woodby, and R.A. Nisbet. 1991. Kirtland’s Warbler habitats: a possible early indicator of climate warming. Biological Conservation 56:63–78.

Buech, R.R. 1980. Vegetation of a Kirtland’s Warbler breeding area and 10 nest sites. Jack-Pine Warbler 58(2):58–72.

Byelich, J., W. Irvine, N. Johnson, W. Jones, H. Mayfield, R. Radtke, and W. Shake. 1985. Kirtland’s Warbler Recovery Plan (revised version). Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

Chamberlain, D. 1978. Status Report on Kirtland’s Warbler (Dendroica kirtlandii) in Canada. Prepared for the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), Ottawa, Ontario.

COSEWIC. 2000. COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Kirtland’s Warbler Dendroica kirtlandii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. v + 10 pp.

DeLoria-Sheffield, C.M., K.F. Millenbah, C.I. Bocetti, P.W. Sykes, and C.B. Kepler. 2001. Kirtland’s Warbler diet as determined through fecal analysis. Wilson Bulletin 113(4):384–387.

Devitt, O.E. 1967. Birds of Simcoe County, Ontario. Brereton Field Naturalists, Barrie, Ontario.

Haney, J.C., D.S. Lee, and M. Walsh-McGehee. 1998. A quantitative analysis of winter distribution and habitats of Kirtland’s Warblers in the Bahamas. Condor 100:201–217.

Harrington, P. 1939. Kirtland’s Warbler in Ontario. Jack Pine Warbler 17:96–97.

Harwood, M. 1981. Kirtland’s Warbler - a born loser? Audubon 83(3):99–111.

Huber, P.W., J.A. Weinrich, and E.S. Carlson. 2001. Strategy for Kirtland’s Warbler Habitat Management. Michigan Department of Natural Resources; Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; and Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

Kashian, D.M. and B.V. Barnes. 2000. Landscape influence on the spatial and temporal distribution of the Kirtland’s Warbler at the Bald Hill burn, northern Lower Michigan, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 30:1895–1904.

Kelly, S.T. and M.E. DeCapita. 1982. Cowbird control and its effect on Kirtland’s Warbler reproductive success. Wilson Bulletin 94(3):363–365.

Kepler, C.B., G.W. Irvine, M.E. DeCapita, and J. Weinrich. 1996. The conservation management of Kirtland’s Warbler, Dendroica kirtlandii. Bird Conservation International 6:11–22.

Knudsen, R.L. 1999. Algoma Kirtland’s Warbler Survey — Final Report. Report prepared for the Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region, Environment Canada, Nepean, Ontario. September 7, 1999. 9 pp. + 2 appendices.

Leopold, N.F., Jr. 1924. The Kirtland’s Warbler in its summer home. Auk 41:44–58.

Line, L. 1964. The Jack-Pine Warbler Story. Michigan Audubon Society. Reprinted from Audubon Magazine, November–December 1964.

Mayfield, H.F. 1953. A census of Kirtland’s Warbler. Auk 70:17–20.

Mayfield, H.F. 1960. The Kirtland’s Warbler. Cranbrook Institute of Science, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan.

Mayfield, H.F. 1962. 1961 decennial census of the Kirtland’s Warbler. Auk 79:173–182.

Mayfield, H.F. 1972. Winter habitat of Kirtland’s Warbler. Wilson Bulletin 84(3):347–349.

Mayfield, H.F. 1977. Brood parasitism reducing interactions between Kirtland’s Warblers and Brown-headed Cowbirds. Pp. 85–91 in: Endangered Birds: Management Techniques for Preserving Threatened Species (S.A. Temple, Ed.). University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin. 466 pp.

Mayfield, H.F. 1983. Kirtland’s Warbler, victim of its own rarity? Auk 100:974–976.

Mayfield, H.F. 1992. Kirtland’s Warbler. In: The Birds of North America, No. 19 (A. Poole, P. Stettenheim, and F. Gill, Eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and The American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, D.C.

Mayfield, H.F. 1993. Kirtland’s Warbler benefits from large forest tracts. Wilson Bulletin 94:363–365.

Mayfield, H.F. 1996. Kirtland’s Warbler in winter. Birding 28:34–39.

Michigan Department of Natural Resources. 2005. Michigan’s Kirtland’s Warblers Set New Record-High for Census Count. News release dated July 11, 2005. (accessed November 30, 2005).

Natural Heritage Information Centre. 2005. NHIC Database [web application]. Natural Heritage Information Centre, Peterborough, Ontario. (accessed November 30, 2005; February 2, 2006).

NatureServe. 2005. NatureServe Explorer: An Online Encyclopedia of Life [web application]. Version 4.4. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. (accessed November 29, 2005).

Olson, J.A. 2002. Special Animal Abstract for Dendroica kirtlandii (Kirtland’s warbler). Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Lansing, Michigan.

Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas. 2005. Breeding Bird Atlas Data. (accessed November 25, 2005).

Petrucha, M.E. and P.W. Sykes, Jr. 2006. Unpublished data. Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Lapeer, Michigan and US Geological Survey, Athens, Georgia.

Probst, J.R. 1986. A review of factors limiting the Kirtland’s Warbler on its breeding grounds. American Midland Naturalist 116(1):87–100.

Probst, J.R. 1988. Kirtland’s Warbler breeding biology and habitat management. In: Integrating Forest Management for Wildlife and Fish (J.W. Hoekstra and J. Capp, Compilers). U.S. Department of Agriculture (General Technical Report NC-122).

Probst, J.R. and K.R. Ennis. 1989. Multi-resource value of Kirtland’s Warbler habitat. P. 69 in: At the Crossroads: Extinction or Survival (K.R. Ennis, Ed.). Proceedings of the Kirtland’s Warbler Symposium, February 9–11, 1989, Lansing, Michigan. Huron-Manistee National Forests and Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Probst, J.R. and J.P. Hayes. 1987. Pairing success of Kirtland’s Warbler in marginal versus suitable habitat. Auk 194:234–241.

Probst, J.R. and J. Weinrich. 1993. Relating Kirtland’s Warbler population to changing landscape composition and structure. Landscape Ecology 8(4):257–271.

Probst, J.R. D.M. Donner, C.I. Bocetti, and S. Sjogren. 2003. Population increase in Kirtland’s Warbler and summer range expansion to Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, USA. Oryx 37(3):365–373.

Ryel, L.A. 1981. Population change in the Kirtland’s Warbler. Jack-Pine Warbler 59(3):76–91.

Species at Risk Act, Statutes of Canada 2002, c. 29, s. 2.

Solomon, B.D. 1998. Impending recovery of Kirtland’s Warbler: case study in the effectiveness of the Endangered Species Act. Environmental Management 22(1):9–17.

Speirs, D.H. 1984. The first breeding record of Kirtland’s Warbler in Ontario. Ontario Birds 2(2):80–84.

Sykes, P.W., Jr. 1997. Kirtland’s Warbler: a closer look. Birding 29:220–227.

Sykes, P.W., Jr. and M.H. Clench. 1998. Winter habitat of Kirtland’s Warbler: an endangered nearctic/neotropical migrant. Wilson Bulletin 110(2):244–261.

Walkinshaw, L.H. 1983. Kirtland’s Warbler, the Natural History of an Endangered Species. Cranbrook Institute of Science, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. 207 pp.

Weinrich, J.A. 1994. Personal communication [cited in Sykes 1997].

Wing, L.W. 1933. Summer warblers of the Crawford County, Michigan, uplands. Wilson Bulletin 45:70–76.

Wood, N.A. 1904. Discovery of the breeding area of Kirtland’s Warbler. Bulletin of the Michigan Ornithologists' Club 5:3–13.

Wood, N.A. 1926. In search of new colonies of Kirtland’s Warblers. Wilson Bulletin 38:11–13.

Woodby, D.A., D.B. Botkin, and R.A. Nisbet. 1989. The potential decline of habitat for the Kirtland’s Warbler due to the "greenhouse" effect. P. 94 in: At the Crossroads: Extinction or Survival (K.R. Ennis, Ed.). Proceedings of the Kirtland’s Warbler Symposium, February 9–11, 1989, Lansing, Michigan. Huron-Manistee National Forests and Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Wright, H.A. and A.W. Bailey. 1982. Kirtland’s Warbler. P. 55 in: Fire Ecology: United States and Southern Canada. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Personal communications

Bloom, R., Biologist, Canadian Wildlife Service – Prairie and Northern Region

Huber, P., Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Mio, Michigan

Sjogren, S., Wildlife Biologist, Hiawatha National Forest, St. Ignace, Michigan

4. Contacts

4.1 Responsible jurisdictions

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources

4.2 Recovery team members

Ken Tuininga (Chair)

Senior Species at Risk Biologist

Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region

Environment Canada

4905 Dufferin Street

Toronto, ON

M3H 5T4

Tel.: (416) 739-5895

Fax: (416) 739-4560

Email: ken.tuininga@ec.gc.ca

Members

Paul Aird, Faculty of Forestry and Centre for Environment, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario

Daryl Coulson, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Pembroke, Ontario

Appendix 2. Action plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Canada

Federal action plan cover photo: © Department of National Defence / Daryl Coulson.

Document information

Recommended citation

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2016. Action Plan for the Kirtland’s Warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Action Plan Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada. Ottawa. v + 20 pp.

Additional copies

For copies of the action plan, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, recovery strategies, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Également disponible en français sous le titre « Plan d'action pour la Paruline de Kirtland (Setophaga kirtlandii) au Canada »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change, 2016. All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-100-25736-5

Catalogue no. CW69-21/14-2016E-PDF

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of action plans for species listed as Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened for which recovery has been deemed feasible. They are also required to report on progress within five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry.