2. Designating a district

Before designating a heritage conservation district, a municipality’s Official Plan must contain a policy relating to the establishment of HCDs.

The recommended components of an HCD that complies with best practices are:

- sound examination of the rationale for district designation, especially for the delineation of district boundaries

- Historic Context Statement

- active public participation in the designation process

- clear and complete designation bylaw and

- clear and well-publicized HCD plan and policies to manage change in the district to protect and enhance its character

- for HCD by-laws passed on or after January 1, 2023 (where notice of public meeting was not provided before January 1, 2023):

- analysis of the properties in relation to section 3 of Ontario Regulation 9/06 including 25% of the properties within the district meeting two or more of the criteria

The following are the steps in the process to designate an HCD:

- The study phase

- Step 1 – Request to designate

- Step 2 – Consultation with the municipal heritage committee

- Step 3 – The Area Study and Interim Control

- Step 4 – Determination of cultural heritage value or interest and identification of heritage attributes

- Step 5 – Delineation of boundary of an HCD

- Step 6 – Public consultation

- The implementation phase

- Step 1 – Preparation of the HCD plan and guidelines

- Step 2 – Passing the designation bylaw and adoption of the HCD plan

- Step 3 – Registration of bylaw on title

- Step 4 – Identification of necessary amendments to existing bylaws and official plan provisions

- Step 5 – Implementing the HCD plan

2.1. Step 1 – Request to designate

There is no formal process for requesting the designation of an HCD. The initial request usually comes from the municipal heritage committee or a local residents’ or heritage organization. Council can also decide of its own accord to designate an HCD without request from the public. Any individual resident, business or property owner can, however, request that an area be considered for designation. Municipalities will have a defined process for how requests are received and processed. These may be made through the municipal clerk, local councillor, municipal planner or municipal heritage committee member. Following consultation with the municipal heritage committee (where appointed), it is up to council to decide whether to proceed with the designation process of the area as an HCD.

While the act does not require that a study be carried out before the passing of the bylaw to designate any area as an HCD, a study is important for the preparation of an HCD plan which is required for every HCD designated under the Ontario Heritage Act since 2005.

2.2. Step 2 – Consultation with the municipal heritage committee

A municipality does not need a municipal heritage committee (MHC) to designate an HCD. There are, however, advantages in having an MHC in place, to help with the identification of heritage objectives for a district study and to guide the designation and implementation process. Where an MHC exists, and council undertakes the study of an area to consider the designation of an HCD, the Act requires that council consult with the committee about the study.

In areas where there is no appointed MHC or municipal heritage planner, council should seek advice from a local heritage or community organization or a heritage consultant on the suitability of the area being considered, and on boundaries for the study area.

2.3. Step 3 – The area of study and interim control

2.3.1. Scope of study

When a municipality has opted to undertake a Heritage Conservation District study, subsection 40 (2) of the Ontario Heritage Act sets out the scope of the study as follows.

The study shall:

- examine character and appearance of the area including buildings, structures and other property features

- examine and recommend area boundaries

- consider and recommend objectives of designation and content of the HCD plan

- recommend changes to Official Plan and municipal bylaws including zoning bylaws

The character of a candidate HCD is established by its physical features, past or present usages and activities and/or its historical or cultural associations. An area’s buildings and open spaces, their relationship with each other, and the stories that give them meaning are what the designation of a heritage conservation district seeks to protect and enhance. Elements such as the street layout, open spaces and the visual components of the public realm all contribute to a district’s character and appearance.

Together, they provide an overall impression that both residents and visitors appreciate and would want to retain, promote and enhance. Appearance is about the visual elements that define the outward aspect of a place. Those elements may include:

- its profile or skyline

- the arrangement, massing, proportions, and dimensions of its parts

- use of materials, colours, and detailed features

- presence (or absence) of natural elements such as landforms, plants and trees and

- its significant views or vistas (visual links)

2.3.2. Designation of heritage conservation study area

Once council has undertaken a study, council must decide whether to formalize the process passing a bylaw under subsection 40.1 (1) of the Ontario Heritage Act to designate an HCD Study Area. The advantage of this approach is that it alerts all property owners in the study area about the commencement of a study and it provides Council with the ability to prohibit or set limits on alterations of property and the erection, demolition or removal of buildings or structures or classes of buildings and structures within the study area boundaries while it is being studied (see Interim Control, below).

The bylaw is optional and may only designate the area as a heritage conservation study area for a period of up to one year and may be appealed by any person to the Ontario Land Tribunal. Given the authority of the bylaw and its time restriction, municipalities should consider the appropriate stage of the study process where this tool may be used if needed. The bylaw is particularly useful where the threat to the cultural resource(s) within the study area and controls are needed to prevent damage and/or loss to cultural heritage resources within the study area.

Since the bylaw may only designate the study area for up to a one-year period, municipalities may prefer to proceed without this bylaw until the initial research phase has been completed. When there is community interest, and the heritage attributes and potential boundaries for the district are clearer, the study area bylaw can be passed, but is not required for the designation of a district.

2.3.3. Interim control

Subsection 40.1(2) of the OHA provides council with the option to put in place interim control measures within the study area in the bylaw designating an area as a Heritage Conservation District Study Area. The interim control measures may prohibit or set limitations with respect to alterations of property, and the erection, demolition or removal of buildings or structures, or classes of buildings and structures.

The interim controls have the effect of protecting the cultural heritage value or interest of the area while a study is underway. Interim control measures are in effect for a maximum period of one year.

The municipality cannot extend study area interim controls beyond the one-year period. The district study bylaw controls are also subject to appeal to the Ontario Land Tribunal, which can delay the coming into force of the study bylaw and the completion of the study.

Furthermore, council cannot pass another bylaw to designate another study area which includes a previously designated study area for a three-year period after the prior designation ceases to be in effect.

Interim control measures should, therefore, only be considered where there is a clear possibility of adverse impacts from alteration or development activities in the area. The three- year restriction applies following any study area bylaw, whether or not council chooses to include interim control measures in the bylaw.

Council must cause notice of the bylaw to be published in a newspaper having general circulation in the municipality and served on every property owner in the area individually (as well as the Ontario Heritage Trust). If there are objections to the bylaw, it can be appealed by any person to the Ontario Land Tribunal (see 40.1(4) for appeal requirements). With the exception of circumstances allowing for a motion for dismissal without a hearing (see subsections, 40.1(5), 41(8) and (9), the Tribunal will hold a hearing to hear the objections and will decide on the acceptability of the study area bylaw or any interim controls included in the bylaw. The decision made by the Tribunal is binding on the municipality.

2.3.4. Organizing the study

Depending on the size and type of area, it may be convenient to divide the study into several stages.

Typical stages of a study area include:

- Historical and documentary research should be used to understand environmental conditions and human activities that have shaped the area over time. Attention should be paid to design intentions as well as design results, and to the technological, economic, and cultural conditions that have affected the character of the area. Modest vernacular buildings may represent as much of a triumph over circumstance as high-style structures. Gardens and landscape features and agricultural practices may reveal as much about a community as its buildings. Public investments in an area may reflect cultural attitudes and biases as much as private property developments. The presence of institutions may be important in defining the character and appearance of a heritage conservation district.

- Field studies should be carried out to document and study the area and identify key visual elements. Field studies can document the existing physical environment and related patterns of activity. These observations can then be added to the findings of the documentary research. The historical record is thus brought forward into the present.

- Public participation is critical to the designation and implementation of an HCD. People who live in the study area need to express and communicate the value of the area. As residents, they are often best able to identify important landmarks, nodes, boundaries and other elements that define the existing character of a place. They should be appropriately engaged and fully informed in the examination of future options for their area.

The historical and documentary research together with field studies present a composite view of an area. The community’s perspectives add value and meaning to the various elements. As these come together, a district’s potential boundaries and its heritage attributes become clearer.

2.4. Step 4 – Determination of cultural heritage value or interest and identification of heritage attributes

Careful assessment of a district’s cultural heritage value or interest is key to its protection and is critical for an understanding of the distinctiveness of an area within its larger context. Distinctiveness may be attributable not only to natural and built forms, but also to historic interest derived from associations to people, events or themes of cultural significance.

The province has developed criteria for determining cultural heritage value or interest, which are set out in Ontario Regulation 9/06. For by-laws passed on or after January 1, 2023 (where notice of public meeting was not provided before January 1, 2023) these criteria are mandatory for designation of heritage conservation districts under Part V of the Act.

Per O. Reg 9/06, at least 25% of properties located within an HCD must meet two or more of the nine criteria for determining cultural heritage value or interest. How a municipality demonstrates that an HCD has met the 25% threshold will vary depending on the size, context, and boundaries of the HCD. The requirement that at least 25% of properties included in the HCD meet two or more of the criteria represents a minimum threshold. It is possible for all the properties in an HCD to meet two or more criteria.

The examination of a district may require evaluation of each part, or individual property based on:

- Design/Physical Value:

- Buildings or structures within the district may contribute to the study of the architecture or construction of a specific period or area, or the work of an important builder, designer, or architect. Specific architectural considerations should include style, use of materials and details, colours, textures.

- An area where buildings make use of local forms and materials may be important to the community’s heritage.

- Historical/Associative Value:

- The area may have been associated with the life of a historic person or group, or have played some role in an important historical event or episode.

- Contextual Value:

- Where a building or structure is an integral part of a distinctive area of a community, or is considered to be a landmark, its contribution to the neighbourhood character may be of cultural heritage value or interest.

- Other examples of heritage attributes that may have contextual value in an HCD include: lighting, windows, doors, signs, ornaments, that are specific to the area and help to create continuity between neighbouring buildings, structures, or sites.

2.4.1. Ontario Regulation 9/06: Criteria for determining cultural heritage value or interest

For by-laws passed on or after January 1, 2023 (where notice of public meeting was not provided before January 1, 2023), section 3 of Ontario Regulation 9/06 under the Ontario Heritage Act states at least 25% of the properties within the defined boundary of a heritage conservation district must meet two or more of the following criteria:

- The properties have design value or physical value because they are rare, unique, representative or early examples of a style, type, expression, material or construction method.

- The properties have design value or physical value because they display a high degree of craftsmanship or artistic merit.

- The properties have design value or physical value because they demonstrate a high degree of technical or scientific achievement.

- The properties have historical value or associative value because they have a direct association with a theme, event, belief, person, activity, organization or institution that is significant to a community.

- The properties have historical value or associative value because they yield, or have the potential to yield, information that contributes to an understanding of a community or culture.

- The properties have historical value or associative value because they demonstrate or reflect the work or ideas of an architect, artist, builder, designer or theorist who is significant to a community.

- The properties have contextual value because they define, maintain or support the character of the district.

- The properties have contextual value because they are physically, functionally, visually or historically linked to each other.

- The properties have contextual value because they are defined by, planned around or are themselves a landmark.

For more information about the evaluation of cultural heritage resources please see the Ontario Heritage Tool Kit’s Heritage Property Evaluation Guide.

2.4.2. Additional Considerations in an HCD

Assessing the cultural heritage value or interest of a district may also require examination of how the district fits into its broader context, as well as a consideration of the connections between the various sites, buildings, structures, landmarks within the HCD. Understanding a district’s context may include the following considerations:

- Landscapes and public open spaces. The study of a potential district should also include public spaces such as sidewalks, roads and streets, and parks or gardens. These features often play roles as conspicuous as those of buildings in the environment. Open spaces provide settings and places from which to view built forms, and can also be valued landscapes in their own right. Public open spaces are often features of the original plan of a settlement or community and can be focal points for ordering and organizing streets, buildings, and other features within the settlement area.

- Overall spatial pattern. A spatial pattern is a perceived arrangement of things on land (and/or water) and of the spaces in between those objects. A pattern may be recognized because of the layout of its parts, e.g., in a line, or a cluster, or an array when spread out over a wide area. An identified pattern acquires greater meaning if it is shown to have design value, or associative value, or contextual value.

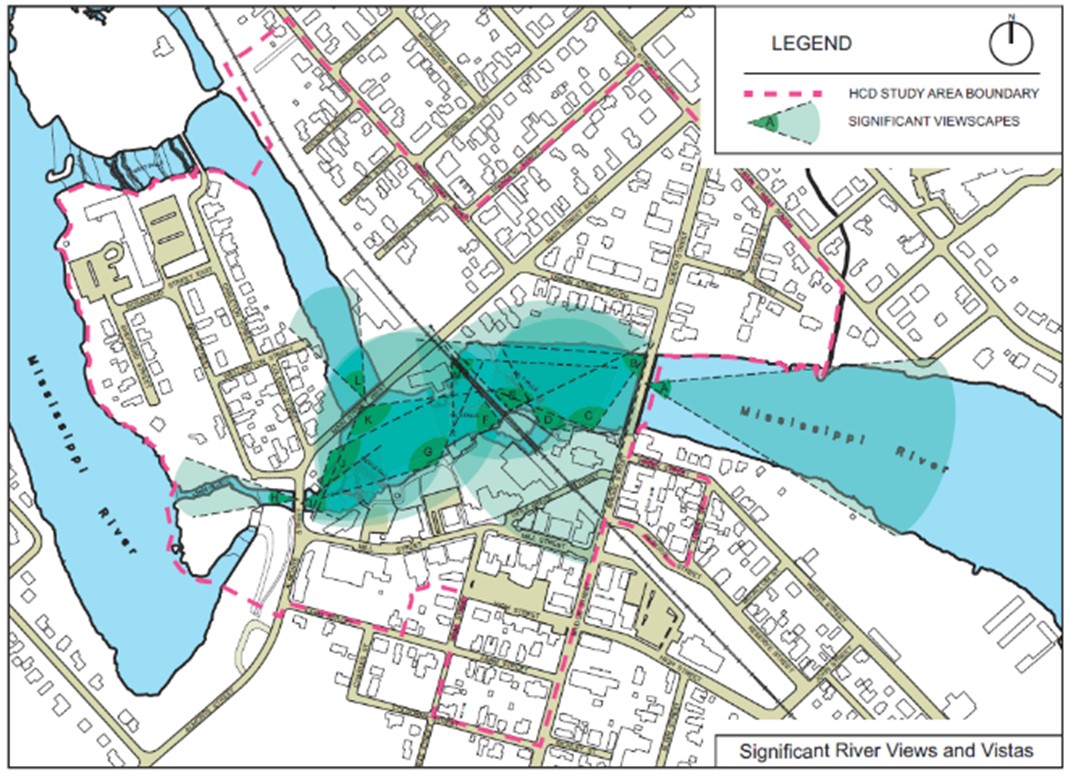

- Views or vistas. Visual settings can be important heritage attributes of a heritage conservation district. Views or vistas can be defined or framed by buildings and other structures, landforms, vegetation patterns or structures. Panoramic views, and particularly ones that the public has been appreciating for many years, can offer a “visual mosaic” of the district, and can help tell the story of past or existing land uses and other activity.

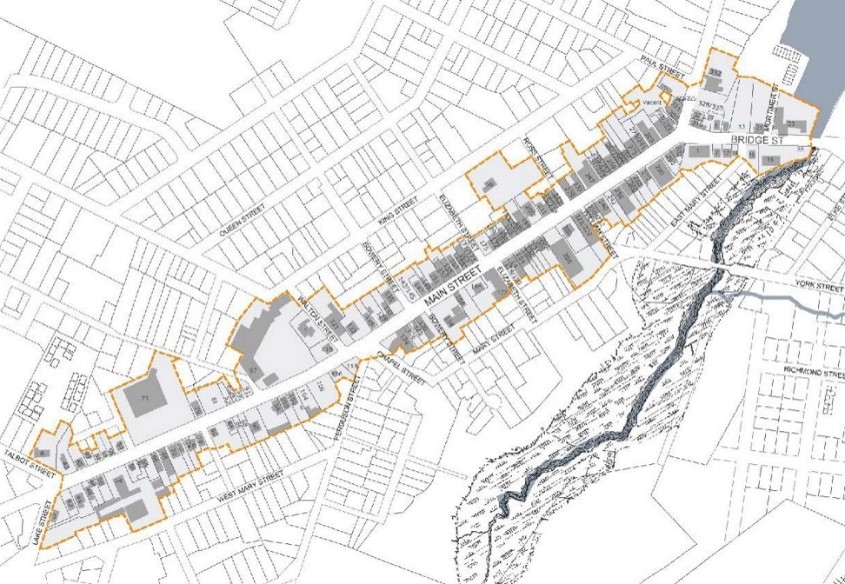

2.5. Step 5 – Delineation of the boundary of an HCD

Boundary delineation is a critical task during the study phase of the district designation process. Some study areas have an obvious character and a clear set of boundaries. Others are more difficult to define. They may include both cultural and natural features. They may cross jurisdictional boundaries. They may have evolved over time. The initial research phase can be used to decide the possible boundaries of a district.

The final definition of boundaries should come from the findings of the research and the community consultation process.

Visual perceptions

- distinctive architecture, design, scale, style, layout, setting, materials, workmanship

- marked change in the arrangement of buildings (massing, height, setback, etc.) distinct changes in topography or landform

- "gateways" (i.e., a primary arrival and departure point, often offering a significant

- view or vista, vantage points, views and vistas to and from an area

Physical situation

- railroads and major highways

- streets, public utilities and rights-of-way

- rivers, shorelines, ravines and other natural features major open spaces

- limits of a settled area

- major changes in land or building use walls, embankments, fences

Historical evolution

- boundaries of an original settlement, site/s of significance to Indigenous community, or early planned settlement concentration of early buildings and sites

- defined areas affected by specific historic events

“Paper” lines and other factors

- property lines

- setbacks set out in the zoning bylaw regulating building form

- boundaries of land use zones in the zoning bylaw or official plan designations

- boundaries of legal jurisdiction (e.g. municipal boundaries)

Boundaries should be drawn to include not only buildings or structures of interest but also the whole property on which they are located. Sites of significance to Indigenous community, vacant land, infill sites, public open space and contemporary buildings may also be included within the district to ensure that their future development is in keeping with the character of the area. Buildings and structures that contribute to the scale or scenic amenity of the area, may also be included.

When setting the extents of a district – in drawing the edges on a two-dimensional map -- always consider how that line will be perceived by residents and different user groups, in three dimensions, over time, when moving through the district. Though a district’s legal implementation depends on the two-dimensional lines, its ultimate effect will be judged by how well it protects and conserves the real, visible, three-dimensional character of the district embraced by those lines.

2.6. Step 6 – Public consultation

Successful implementation of a district will ultimately depend on wide-spread public support for district designation based on a clear understanding of the objectives for designation and appreciation of the proposed HCD plan, policies and guidelines.

Decisions about policies and guidelines should be made in an open forum, where the benefits of designation and the responsibilities that come with it can be clearly communicated. There should be a clear agenda and timetable for proceeding with the district study and well-publicized public meetings at important stages, to allow for comprehensive discussion of the issues with area residents and property owners.

The Ontario Heritage Act only requires one public meeting before passing the bylaw to designate the district. It is recommended that there be three or more well-advertised public meetings before the draft district plan and bylaw are submitted for public comment at the statutory public meeting.

Meetings can be conducted as follows:

- The initial public meeting allows municipal staff and municipal heritage committee members to explain the process for district designation and its potential benefits, and to receive initial comments and views.

- The second meeting allows for consultation and discussion of the proposed boundary and other results of the study.

- The third public meeting provides opportunity for review of the draft plan and guidelines.

Depending on the outcome of the third meeting, further meetings may be required, possibly with smaller groups, to resolve any outstanding issues before the draft district plan is finalized.

It may be advantageous to appoint a local steering or advisory committee with representation from local residents, businesses and other property owners and stakeholders, to oversee the study and to work with the municipal heritage committee (where appointed) in advising council on future heritage permit applications after the district is designated.