Context and background

Safety, human rights, and dignity. These are cornerstones of the ministry’s framework for modernization. All working people in Ontario have a right to a safe and secure working environment that respects their human rights and dignity; frontline correctional staff and managers are no exception. Individuals on remand, immigration detention hold, and those serving sentences also have a right to a safe and secure space where their human rights are upheld, and where they are treated with dignity while in the care and custody of the province. Violence is an obvious threat to the security of a correctional facility as well as both the physical and mental well-being of those working or living within the institution.

Institutional violence does not just happen. It is the product of complex, multiple, and intersecting variables – inmate crowding and corresponding staff levels, recruitment and hiring, staff-management relationships, institutional security, inmate risk and classification processes, criminal gang activity, mental health and addiction issues, poor infrastructure design and/or construction, lack of official and independent oversight, operational policy gaps, and systemic failures. The Independent Review of Ontario Corrections’ Institutional Violence in Ontario: Interim Report attempted to unpack some of these variables, however, given the 90-day timeframe allotted for the initial review, the scope of that report was limited to presenting findings on available data and reporting on employee feedback. The Institutional Violence in Ontario: Final Report used those findings as the foundation for the in-depth investigation and included additional feedback from institutional employees in order to present recommendations to the MCSCS.

Nobody, not the men and women who are sent by the courts, not the men and women who work in the institutions, nobody goes to a jail to endure violence.

Howard Sapers, Independent Advisor, CBC Radio, May 2018

Findings from the Interim Report

The summarized key findings from the Interim Report are listed below, under the three main themes highlighted in that report. The Final Report is meant to be read in conjunction with the publicly available Interim Report,

Data Collection and Information Reporting

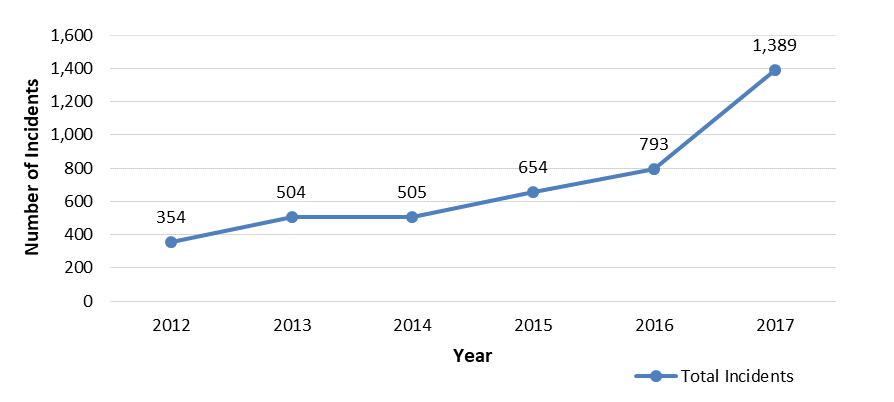

- The total number of reported inmate-on-staff incidents of violence have increased in recent years, with substantial increases observed between 2016 (793 incidents) and 2017 (1,389 incidents) (Figure 1). The largest proportion of reported violent incidents was threats. Based on details available in Inmate Incident Reports, it is possible that some incident types (e.g., threats, spitting-related incidents) are now more frequently reported than in prior years. However, the observed growth in reported physical assaults suggests that increased or better reporting practices do not wholly explain the spike in reported inmate-on-staff violence in recent years.

Figure 1. Reported inmate-on-staff incidents of violence, 2012-2017

Note: These numbers are incidents of inmate-on-staff violence reported by staff in Ontario institutions. There are concerns with subjectivity and consistency of reporting, and data collection and analysis practices at the ministry. These numbers are one indication of the number of inmate-on-staff violent incidents but should not be used as a final tally.

- Comparing institutions of similar size, there are notable variations in reported inmate- on-staff violence both by total number of incidents and by rate of increase over time. In particular, the Toronto South Detention Centre experienced a surge in reported incidents of inmate-on-staff violence between 2016 and 2017.

- There are limitations on the conclusions that can be drawn solely from Inmate Incident Reports and the ministry’s current collection and analysis methods are insufficient for meaningful monitoring of inmate-on-staff violence. Other pertinent information about an incident, such as factors that relate to specific inmate populations, staff members, institutions, or regions of the province, are not in formats that lend themselves readily to analysis. These variables are of interest to explain the nature of institutional violence.

Institutional Culture and Staffing

- Staff reported that they are currently hesitant to use force, and that inmates are aware of this and are empowered to challenge institutional rules. However, in spite of a declining inmate population, staff reports of use of force incidents have nearly doubled since 2013 (from 1,249 reported incidents to 2,490 in 2017). It is possible that this was due to improved reporting.

- The proportion of use of force training provided to correctional staff that is formally dedicated to verbal defusion of hostility techniques is inconsistent with the ministry’s emphasis on resolving incidents with verbal intervention and de-escalation. The ministry has stated that the correctional officer training curriculum will be restructured, but it is unclear what changes will be implemented or when.

- Correctional employees have continued to advocate for mandatory minimum sentences as a response to institutional violence, despite numerous studies that have consistently suggested that they are not effective at deterring crime or violent acts. The Criminal Code does not authorize judges to impose mandatory minimum sentences for the following offences: uttering threats, assault, assault with a weapon or causing bodily harm, aggravated assault, intimidation of a justice system participant, assaulting a peace officer, assaulting a peace officer with a weapon or causing bodily harm, or aggravated assault of a peace officer. Imposing mandatory minimum sentences for the majority of violent incidents that occur within correctional institutions would be contrary to sentencing principles such as proportionality and the need to tailor sanctions to the unique circumstances of the offence and the offender.

- The number and proportion of misconduct dispositions that were unclear due to missing information increased between 2010 (717, or 6%) and 2017 (1,791, or 10%). If this was indicative of misconducts that could have, but did not, result in guilty findings and sanctions due to incomplete reporting or paperwork, it may have been a factor contributing to the frustrations of staff who perceived there to be a lack of disciplinary consequences for disruptive inmates.

- Many correctional employees expressed concern about the recent influx of new employees and felt that recruits lacked adequate training. In 2016 and 2017, there were substantially heightened numbers of new hires in Ontario institutions. However, the link between institutional violence and new correctional officers was unclear due to data limitations such as the inability to identify which employees were involved in reported inmate-on-staff incidents.

- Many staff indicated that they felt as though management failed to support them in daily operations and undermined the legitimacy of frontline staff’s authority. Correctional officers also reported a lack of recognition by management. In a recent study,

footnote 10 staff reported low morale and a general discontent with upper management.

Operational Practices

- Evidence-based research

footnote 11 has consistently found that early interventions, classification, appropriate housing placements, and entry into treatment or programming can reduce institutional violence. Unfortunately, the ministry does not regularly conduct evidence- based classification or risk analyses to determine institutional security risk or placement needs. - Some correctional staff suggested that changes in the inmate population and, more specifically, a rise in the number of those who committed violent offences, may have impacted levels of institutional violence. Based on ministry snapshot data, the number of inmates in custody for a violent charge as their most serious offence was relatively stable between 2010 and 2017, but due to the declining overall inmate population, the proportion of those in custody for a violent charge increased slightly.

- Several staff expressed concern that cell door meal hatches provide an opportunity for inmates to assault staff when they are left open, particularly by means of throwing objects, liquids, or bodily substances. Modifications to the current hatches were proposed by institutional employees but there is scant evidence on the effectiveness of cell door meal hatches with a ‘sally port’ function in curbing institutional violence. In fact, research

footnote 12 suggests that increasing correctional ‘hardware’, in the absence of other measures (e.g., multi-security level units, evidence-based security classification tools, inmate programming, and additional staff training), is ill-advised and, potentially, counter-productive. - Some frontline staff and the Ontario Public Service Employees Union (OPSEU) members of the Provincial Joint Occupational Health and Safety Committee (PJOHSC) have proposed conducted energy weapons (CEWs) as an option to respond to institutional violence. Research conducted by the Independent Review Team revealed that CEWs were rarely used or were discontinued in Canadian jurisdictions where they had been implemented, due to a lack of evidence suggesting that they lessened the risk of institutional violence.

- Feedback from correctional staff indicated that lack of inmate programming may be a possible explanation for institutional violence. Academic literature

footnote 13 suggests that treatment and programs for inmates can be an effective management tool and can lead to decreased institutional violence and misconducts. - The Ontario Correctional Institute, Ontario’s only medium-security treatment centre for sentenced individuals, consistently reported very few (or no) incidents of inmate-on- staff violence between 2012 and 2017. There are several features of this facility that require investigation, such as dorm-style accommodations, a pre-screening before admission, assessment during orientation, and a different cultural dynamic between inmates and staff.

Footnotes

- footnote[9] Back to paragraph Independent Review of Ontario Corrections, Institutional Violence in Ontario: Interim Report (Ottawa: Independent Review of Ontario Corrections, Government of Ontario, August 2018) (hereafter, IROC, Interim Report).

- footnote[10] Back to paragraph Rachelle Larocque, “Penal Practices, Values and Habits: Humanitarian and/or Punitive? A Case Study of Five Ontario Prisons,” (PhD Diss., University of Cambridge, 2014) (hereafter, Larocque, Penal Practices).

- footnote[11] Back to paragraph Sheila A. French and Paul Gendreau, “Reducing Prison Misconducts: What works!” Criminal Justice and Behavior 33, no. 2 (2006) (hereafter, French and Gendreau, Reducing Misconducts); Mary Ann Campbell, Sheila French, and Paul Gendreau, “The Prediction of Violence in Adult Offenders: A Meta-Analytic Comparison of Instruments and Methods of Assessment,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 36, no. 6 (2009): 567-590 (hereafter, Campbell et al., Prediction of Violence); Richard C. McCorkle et al., “The Roots of Prison Violence: A Test of the Deprivation, Management, and “Not-so-Total” Institution Models,” Crime & Delinquency 41, no. 3 (1995) (hereafter, McCorkle et al., Roots of Prison Violence); Beth M. Huebner, “Administrative Determinants of Inmate Violence: A Multilevel Analysis,” Journal of Criminal Justice 31, no. 2 (2003) (hereafter, Huebner, Inmate Violence).

- footnote[12] Back to paragraph Anthony E. Bottoms, “Interpersonal Violence and Social Order in Prisons,” Crime and Justice 26, (1999); Richard McCleery, “Authoritarianism and the Belief System of Incorrigibles,” in Sharon Shalev, Supermax: Controlling Risk Through Isolation (Portland, OR: Willan Publishing, 2009); Marie Garcia et al., “Restrictive Housing in the US: Issues, Challenges, and Future Directions,” (National Institute of Justice, Washington, DC, 2016).

- footnote[13] Back to paragraph French and Gendreau, Reducing Misconducts, supra note 11.