Appendix A: Toronto South Detention Centre

A-I. Context and background

In May 2018, the former Minister of Community Safety and Correctional Services (MCSCS), Marie-France Lalonde, announced that she had requested Ontario’s Independent Advisor on Corrections Reform to investigate and provide advice on institutional violence. This request came after the former minister observed a “deeply disturbing trend” emerging from reported statistics on violence in Ontario’s provincial correctional facilities.

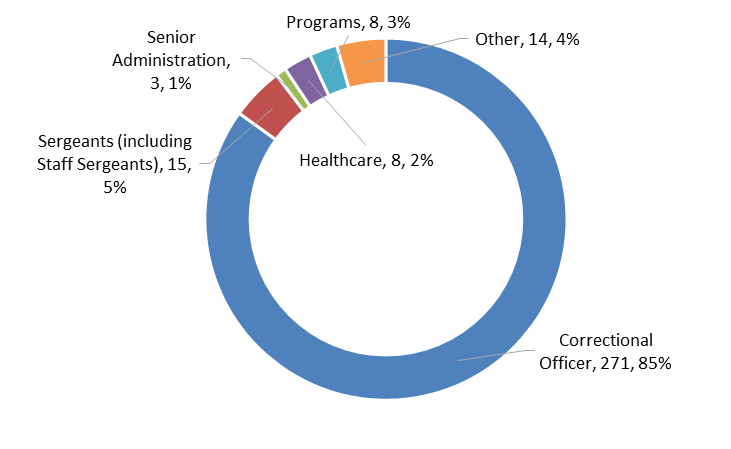

Figure A-1. TSDC respondents to IROC Institutional Violence Survey by job position

TSDC was selected because the Interim Report identified it as an outlier among the rest of Ontario’s provincial correctional facilities; that is, in 2017, TSDC had the highest number of, and greatest rate of increase in, reported incidents of inmate-on-staff violence. The case study explores and evaluates local data as well as policies, practices, and procedures that are believed to impact inmate-on-staff violence at TSDC and informs the Independent Review of Ontario Corrections’ fourth report, Institutional Violence in Ontario: Final Report.

Figure A-2. Exterior TSDC (excluding Toronto Intermittent Centre)

Institutional history

In May 2008, MCSCS announced its plan to construct the Toronto South Detention Centre (TSDC) on the site of the former Mimico Correctional Centre.

Nothing can fix this jail except for shutting it down, transferring inmates out and starting over […] you can also thank the ombudsman for slandering the corrections profession in their many one sided reports #inmatelovers TSDC is a lost cause and too broken, unfortunately no IROC will fix it, thanks for the effort though.

Correctional Officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Since opening in January 2014, TSDC has faced a number of challenges, including considerable negative attention in the media exposing a number of reported incidents of inmate-on-inmate — as well as inmate-on-staff — violence.

Feedback received from institutional employees suggests that TSDC may still be experiencing problems with lockdowns, with one respondent advising the Independent Review Team that, “there are way too many lockdowns. Too many unnecessary imprisonments”. Ministry data reveal that there were 157 partial and 47 full lockdowns at TSDC in 2017 and that around 60%

More recently, TSDC has been subject to criticism after a Nunavut inmate alleged that he had been in segregation for over 21 days and that it was “affecting [his] mental health so bad that [he] couldn’t concentrate anymore”.

Inmate demographics

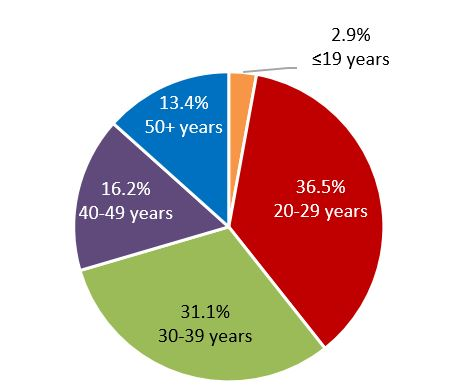

Ministry data report the average inmate population count of TSDC in 2017 as 873 (excluding Toronto Intermittent Centre). The Independent Review Team used monthly snapshot data from TSDC in 2017 to examine demographic characteristics of the inmate population. Approximately 40% of inmates were under the age of 30 years (Figure A-3).

Figure A-3. TSDC average inmates by age, 2017

TSDC is not a rehab facility; we are a remand, which means we are the intake to the Federal Prison system. We house the most violent and amoral offenders on that journey – the ones the Judge won’t grant bail.

Correctional Officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

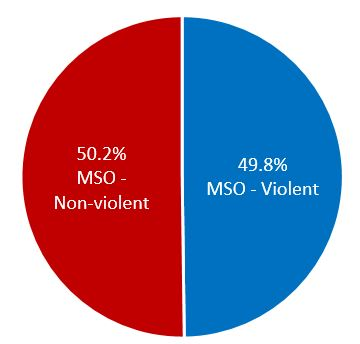

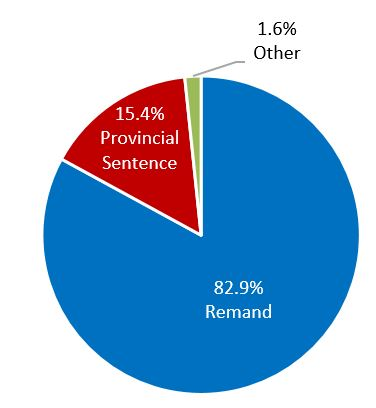

Feedback received from frontline staff revealed that some correctional officers feel that “there is a highly significant amount of the inmate population that are very violent, dangerous, aggressive, and defiant”. Of the average inmate population at TSDC in 2017, approximately half were in custody for a violent offence as their most serious offence (MSO) (Figure A-4), and the vast majority of individuals who were incarcerated at TSDC in 2017 were on remand and, therefore, legally innocent (Figure A-5).

Figure A-4. TSDC average inmates by violent charge for current custody, 2017

Figure A-5. TSDC average inmates by hold status, 2017

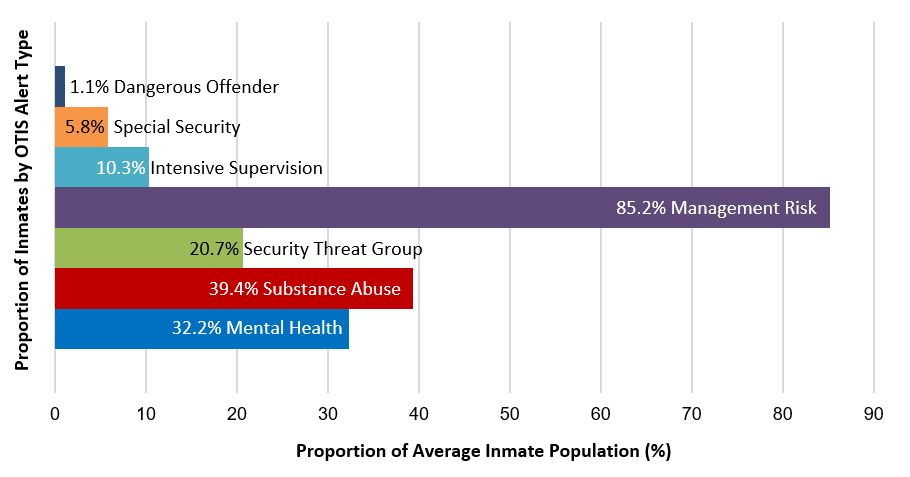

In their feedback, some correctional employees voiced concern regarding the profile of the inmate population and, in particular, many emphasized that there was a “gang problem that is visible” in TSDC. As one senior correctional officer noted, “a portion of the inmate population struggles with drug addiction and mental health but in the TSDC we are overrun with law breaking gang members with zero respect for authority”. Ministry snapshot data show that, in 2017, approximately one-third of the average inmate population had Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS) alerts related to mental health and substance abuse while only 21% had security threat group

Figure A-6. TSDC average inmates by alert type, 2017

Inmate supervision model

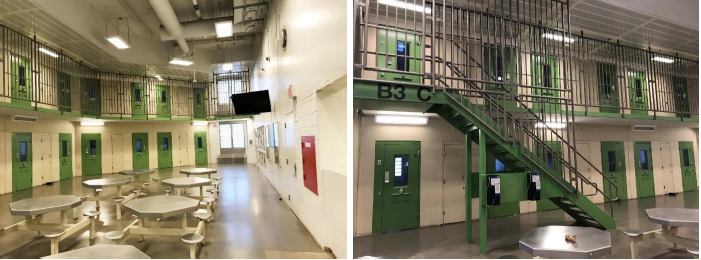

The living units at TSDC were designed and intended to enhance the safety and security of both staff and inmates.

Most units at TSDC are set up to run as direct supervision units (Figure A-7). When the Independent Review Team toured the facility, its members observed that the physical design of the institution was, for the most part, conducive to the direct supervision model.

Figure A-7. Direct Supervision Unit, TSDC

For instance, direct supervision units are open and have a correctional officer desk within the unit, which is monitored by an officer in a subcontrol module who does not have any direct contact with the inmates but can control the unit’s doors, televisions, phones, and water flow remotely (Figure A-8). In direct supervision units, the conditions of confinement are, to a certain extent, normalized by providing soft seating areas to watch television, and permitting inmates to eat meals in the day room with access to hot water for coffee, tea, and dehydrated noodles.

Figure A-8. Subcontrol Module, TSDC

The direct supervision model is premised on the notion that the safety and security of inmates and correctional staff is enhanced when officers are stationed within normalized inmate housing units and establish control and manage inmate behaviour through continuous, personal interaction. TSDC advised that staff interactions with inmates on direct supervision units may be simple verbal communications but could also include facilitating programs or participating in activities, such as card games. Notwithstanding, much of the observed interaction by the Independent Review Team was perfunctory at best.

I feel that building rapport with the inmate population, addressing their needs and normalizing their environment is important.

Senior administrator, Toronto South Detention Centre

TSDC further reported that several of the institution’s operational procedures conform to the principles of direct supervision. For example, the Independent Review Team was advised that unit officers are “seen as the employee in charge of the unit” and have the authority to directly address inmate infractions on direct supervision units through the use of unit sanctions. TSDC indicated that these disciplinary measures are intended to be progressive, tailored to the particular infraction at hand, and may range in severity, such as the assignment of extra cleaning duties, loss of incentives (e.g., recreation), or a cell lockdown. The institution also reported that direct supervision units offer a number of incentives that are used to ensure appropriate inmate behaviour. For example, these units are typically larger, are unlocked between 0800 hours and 2145 hours, and inmates are able to freely access their cells throughout the day. Inmates housed on direct supervision units receive, as an incentive, recreation at least once a week in a large gymnasium off of the unit (Figure A-9) and can participate in various activities on the unit, such as board games, cards, and dominoes. In addition, each direct supervision unit has two televisions with cable packages and a ‘yard’, open during unlock hours, where inmates are able to play basketball and soccer (Figure A-10). Finally, TSDC advised that inmates subject to direct supervision are entitled to four visits per week, one of which can be a face-to-face visit while the other three are via video terminal (Figure A-11).

Figure A-9. Inmate gymnasium, TSDC

Figure A-10. On-unit inmate yard, TSDC

Figure A-11. Video visitation terminals, TSDC

Most respondents indicated in the IROC Institutional Violence Survey that direct supervision was the dominant model at TSDC, although employees varied in the extent to which they felt that it was a meaningful model. Several employees qualified their responses that direct supervision was meaningful with such caveats as “only for a small percentage of the inmate population” or “if used properly […] But not every inmate is [direct supervision] suitable”. One correctional officer indicated that direct supervision “could be meaningful in the right scenario”, while another felt that the meaningfulness of the model was “highly reliant on effective implementation”, and yet another respondent advised that he “believe[s] it will work but [this] requires support from all parties”.

Other respondents were less supportive of direct supervision and did not believe that it was a meaningful model. For instance, one correctional officer with over 20 years of experience working with MCSCS referred to the inmate supervision model at TSDC as “coddling brats”, and that “the model is failed” and is a “useless piece of crap”. Other respondents felt that the direct supervision at TSDC was “garbage”, gave “inmates more opportunity to take advantage of the system”, and was “stressfull [sic] for officers… [and led to] burnout occur[ring] quickly”. Another officer asserted that the direct supervision model “leaves officers to [sic] open to attack” and that “officers have no privacy and no place to privately discipline inmates or even just get info […] A stupid US imported model”.

Respondents’ views also varied considerably on the aspects of the institution that helped the success of the direct supervision model. Although there were some respondents who simply maintained that “nothing” helped and that there was no “success in [direct supervision]… [i]t’s a flawed model that entitles inmates”, the responses provided by other institutional employees were more supportive. For instance, correctional officers advised that “staff supervision, effective communication and monitoring”, along with “building rapport with inmates” “adequate staffing”, “highly trained staff[,] strong staff presence[,] consistency of daily schedule[,] sergeants that allow officers to do the job”, and “dedicated staff” “who buy into the [direct supervision] model” all contribute to the success of the direct supervision model at TSDC. Other respondents highlighted the importance of “step-down units”, “physical structure… and layout of units”, and “access to a variety of programming and activities that are not available in indirect units”.

Frontline employees were equally vocal in their opinions on the aspects of TSDC that hindered the success of the direct supervision model. For instance, correctional officers offered that, “inadequate” or “improper classification of inmates and failure to hold inmates accountable for their actions”, “lack of bed space, lack of management support, officers being blamed for inmate behaviour”, and “not enough programs for the inmates” adversely affect the success of direct supervision at TSDC. In addition, respondents identified the detrimental effect that “lack of cooperation [and] training”, “incompetent Correctional Officers and Management”, “sergeants undermining staff decisions such as sanctions or misconducts”, and “having to [sic] many senior administrators, each with their own views on how things should work, seemingly at odds with each others [sic] vision[,] lack of strong leadership at the top” had on the inmate supervision model.

Some staff are totally opposed to this model and work against it.

Sergeant, Toronto South Detention Centre

Employees occupying various other roles at TSDC, including sergeants, programs and health care staff, and senior administrators also provided feedback regarding hindrances to the success of the direct supervision model. Elements included “too many lockdowns”, “lack of communication, lack of follow-up”, “old ways of thinking”, and “administrators who constantly change the expectations of the model”. In addition, “inexperienced staff”, “sergeants that have no authority over inmates… [and] correctional officers that are scared of inmates and bend rules for them”, and “lack of direct supervision training, poor support and supervision from middle management and a lack of buy in from front-line officers” were all advanced as factors that negatively impacted the success of the direct supervision model at TSDC.

It is telling that only 19%

Staffing numbers

Ministry data revealed that, as of July 31, 2018, TSDC employed a total of 1,197 employees, including 16 senior administrators.

| Job type | Years of service | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job code description | <1 year | 1 to <2 years | 2-5 years | 6-10 years | 11-15 years | 16-20 years | 21-25 years | 26-30 years | 31-35 years | 36 or more years | Total | |

| Correctional Officer 1 | 231 | 11 | 2 | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 245 | |

| Correctional Officer 2 | 4 | 190 | 158 | 85 | 56 | 47 | 17 | 23 | 10 | 1 | 591 | |

| Psychologist 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1 | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | |

| Rehab Officer 2 | n/a | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | n/a | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 8 | |

| Recreational Officer 2 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1 | n/a | n/a | 2 | |

| Social Worker 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | 1 | n/a | n/a | 8 | |

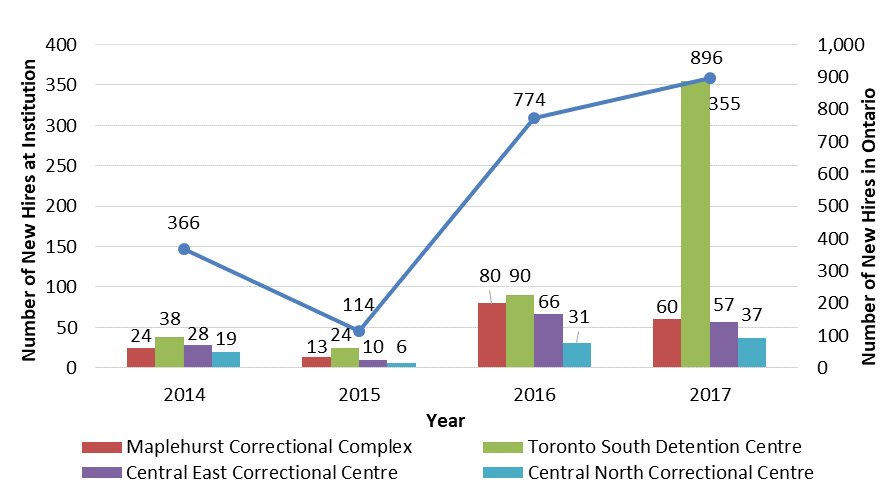

The number of new staff members is a result of the ministry’s commitment, in 2016, to hire 2,000 correctional officers over the following three years after a four-year moratorium on all correctional officer recruitment.

Figure A-12. MCSCS new hires in select Ontario correctional facilities, 2014-2017

The high proportion of relatively new frontline staff may be a contributing factor to the current issues at TSDC which may adversely impact those who live and work within it. As one officer indicated, “I do not feel safe working in direct or indirect units. There are hundreds of new officers who are very young with no experience or proper training”. Another correctional officer, with over a decade of experience working for the ministry, cautioned that “if new staff continue to come, the violence won’t stop. Veteran officers like myself will continue to leave and the institution will be dealing with bigger problems”.

Population ratios

Ministry data

These figures stand in stark contrast to the ratios at Ontario Correctional Institute (OCI), the province’s only medium security treatment centre, which had the lowest number of reported inmate-on-staff incidents among Ontario’s correctional institutions between 2012 and 2017. For social workers/social work managers, the ratio at OCI was one employee per 22 inmates while there was one psychologist/chief psychologist per 34 inmates (Table A-2). Moreover, unlike TSDC, which did not staff the position, there was one psychometrist

While it is necessary for the staffing complement of these two institutions to differ as one is a large remand facility and the other is a smaller correctional treatment centre, it is important to note that research has found that more clinical supports and programming are associated with lower institutional violence.

| Position | Toronto South Detention Centre | Ontario Correctional Institute |

|---|---|---|

| Correctional officer | 1:1 | 1:2 |

| Social worker/social work manager | 1:116 | 1:22 |

| Psychologist/chief psychologist | 1:291 | 1:34 |

| Psychometrist | n/a | 1:109 |

Institutional budget

The total institutional budget for TSDC

| Department | Total |

|---|---|

| Administration | $5,005,887 |

| Correctional | $59,340,097 |

| Food | $1,019,065 |

| Health | $9,888,254 |

| Treatment | $2,044,914 |

| Housekeeping | $2,261,412 |

| Maintenance | $833,986 |

| Academic | $0 |

| Recreation | $539,873 |

| Total | $80,933,488 |

Table A-4 provides a summary of the same figures reported in the 2017/18 fiscal year. Again, salaries and wages accounted for the majority of the total institutional budget, which increased to $108,740,306.

| Department | Total |

|---|---|

| Administration | $5,318,637 |

| Correctional | $63,213,709 |

| Food | $1,063,576 |

| Health | $10,263,756 |

| Treatment | $2,290,245 |

| Housekeeping | $2,284,178 |

| Maintenance | $840,418 |

| Academic | $0 |

| Recreation | $571,826 |

| Total | $85,846,345 |

As these figures demonstrate, correctional staff accounted for approximately 73% of the salaries and wages paid in these two fiscal years while those employed in the treatment and recreation departments accounted, collectively, for under 4%. Furthermore, it is worth noting that TSDC did not staff an academic department in either year.

In the 2016/17 fiscal year, TSDC’s Other Direct Operating Expenditures (ODOE)

| Services | Total |

|---|---|

| Professional services contracts | $780,000 |

| Repairs and maintenance contracts and services | $137,559 |

| Rental and other services | $1,967,928 |

| Additional funds for training | $0 |

| Total | $2,885,487 |

In the 2017/18 fiscal year, the institution’s ODOE budget, again excluding yearly transfer payments, increased to $9,913,189

| Services | Total |

|---|---|

| Professional services contracts | $854,563 |

| Repairs and maintenance contracts and services | $222,661 |

| Rental and other services | $2,433,444 |

| Additional funds for training | $0 |

| Total | $3,510,667 |

A-II. Inmate-on-staff incidents: 2017 in-depth analysis

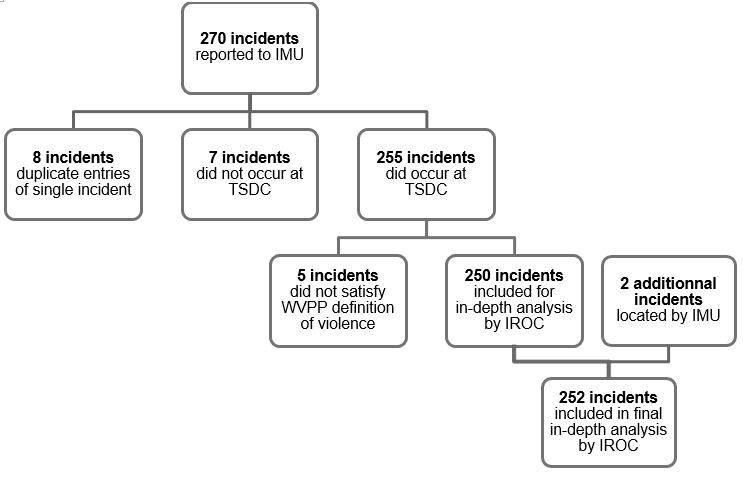

The Independent Review Team obtained copies of the original paper-based Inmate Incident Report (IIR) from the MCSCS’ Information Management Unit (IMU) pertaining to the 270 reported inmate-on-staff incidents in 2017 that were identified to have occurred at TSDC.

- threat

- attempt physical assault

- attempt throw

- throw small item

- throw large item

- throw liquid

- throw bodily fluid/substance

- assault – scratch

- assault – grab

- assault – push

- assault – slap/punch

- assault – bite

- assault – kick

- assault – miscellaneous item

footnote 172 - assault – weapon

- assault – headbutt

- spit or attempt spit

When necessary, additional documents were also requested and reviewed (e.g., Occurrence Reports, Use of Force Occurrence Reports, Misconduct Reports). Following review of the 270 IIRs, a total of 15 incidents were excluded from analysis after the Independent Review Team confirmed that they either occurred elsewhere (e.g., Toronto East Detention Centre, Toronto Intermittent Centre) or were duplicate entries of a single incident. There were 21 inmate-on-staff IIRs that that did not clearly satisfy the Workplace Violence Prevention Program (WVPP) definition of violence,

- The exercise of physical force by a person against a worker, in a workplace, that causes or could cause physical injury to the worker;

- An attempt to exercise physical force against a worker, in a workplace, that could cause physical injury to the worker; or,

- A statement or behaviour that is reasonable for a worker to interpret as a threat to exercise physical force against the worker, in a workplace, that could cause physical injury to the worker.

for which additional documents were requested from TSDC for further analysis. Copies of documents were located and provided for 16 of these incidents, of which five were determined not to satisfy the WVPP definition of violence

Figure A-13. Flow chart of reported inmate-on-staff incidents included for in-depth analysis

Reported incidents of inmate-on-staff violence

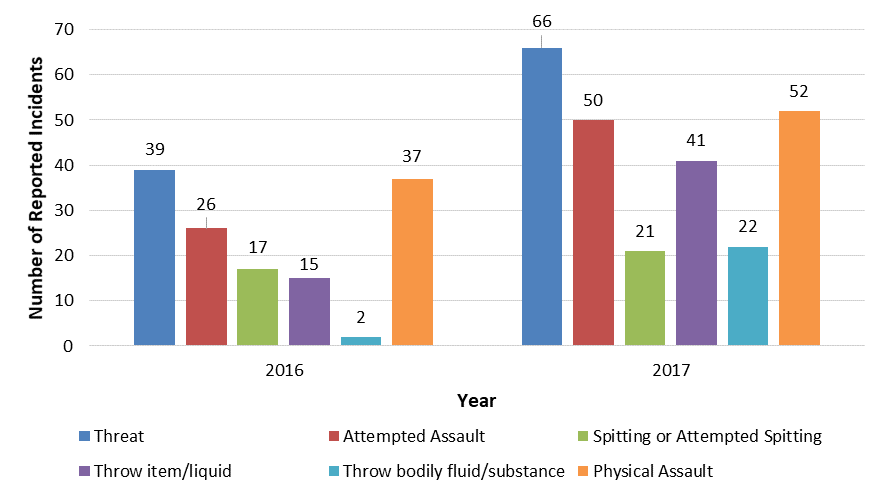

The 252 reported inmate-on-staff incidents of violence included for analysis represent an increase of 85% from the 136 reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC in 2016.

Figure A-14. Reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC, 2016 and 2017 by incident type

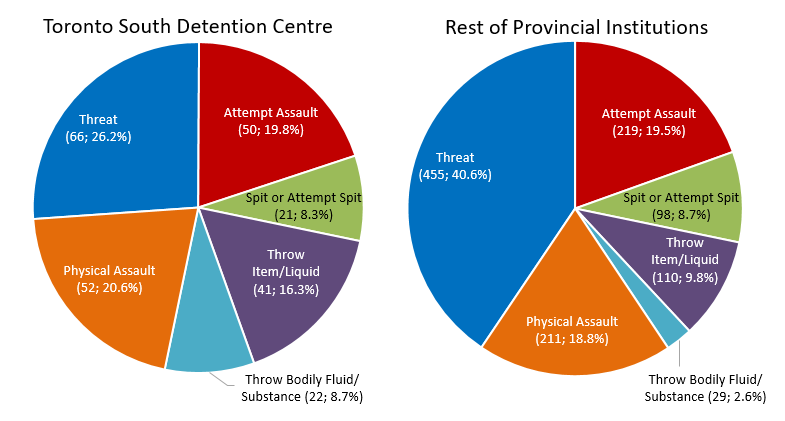

The Independent Review Team compared the incident types at TSDC to the rest of the province as a whole (Figure A-15).

Figure A-15. Reported inmate-on-staff incidents by type, 2017 at TSDC and rest of provincial institutions

Of reported incidents in 2017 in the other 24 provincial institutions, approximately 41% were threats, 20% were attempted assaults, 19% were for physical contact assault, 10% were throwing of items, 9% were spitting-related, and 3% were throwing bodily fluids/substances. TSDC reported a similar proportion of attempted assaults, spitting-related incidents, and physical assaults in 2017 compared to the rest of the province’s correctional institutions. However, a smaller proportion of reported incidents at TSDCwere threats (26%), and larger proportions were throwing of items/liquids (16%) and throwing of bodily fluids/substances (9%).

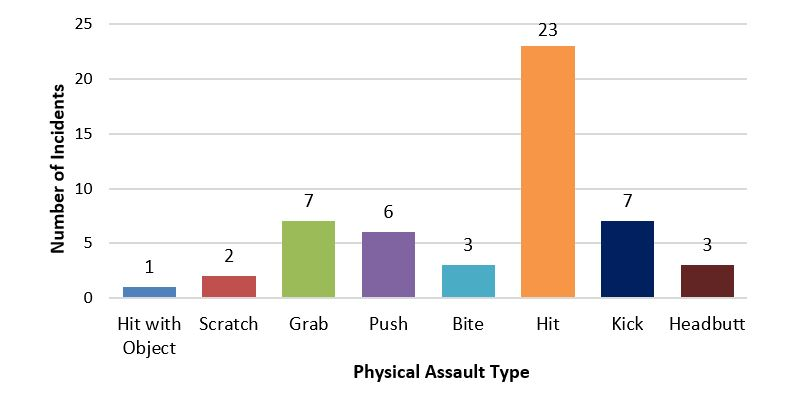

A further breakdown of the reported inmate-on-staff physical assault incidents is displayed in Figure A-16.

Figure A-16. Breakdown of reported inmate-on-staff physical assaults at TSDC, 2017

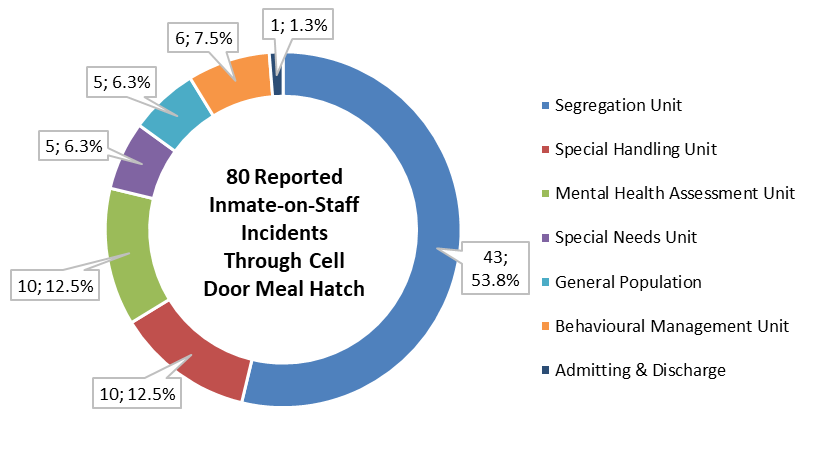

Details in the IIRs indicated that nearly half of the inmate-on-staff attempted or completed assaults (i.e., all categories excluding threats) occurred through the cell door meal hatch (80 of 186 incidents; 43%) while the inmate was confined in a cell (Figure A-17). As expected, the large majority (79%) of all throwing-related incidents (i.e., of items, liquid, or bodily fluids/substances) occurred through the cell door meal hatch. In addition, 14 (28%) of 50 attempted assaults and 10 (19%) of 52 physical assaults occurred through the cell door meal hatch, possibly indicative that the risk of prolonged assault and/or potential severity of injury in these instances was low. The majority of incidents that occurred through the cell door meal hatch also occurred in a Segregation Unit (43 incidents; 54%), with an additional quarter (25%) of incidents having occurred in a Special Handling Unit (10 incidents) or Mental Health Assessment Unit (10 incidents). This data suggests that the cell door meal hatch-related incidents may be restricted to a subgroup of the inmate population that could be appropriately identified and classified so that individualized precautionary measures could be implemented to prevent such incidents from occurring.

Figure A-17. Reported inmate-on-staff incidents through the cell door meal hatch at TSDC in 2017

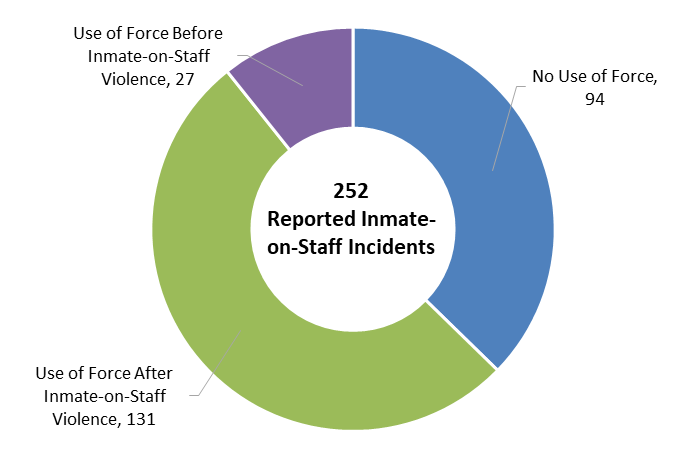

The Independent Review Team was also able, by reading the details of the IIRs, to identify which reported incidents involved correctional employee use of force. The IIRs indicated that force was used in 158 (63%) of the 252 reported inmate-on-staff incidents in 2017 at TSDC. The IIRs and Use of Force Report packages were reviewed to determine the sequence of events involving the use of force; force was used after the inmate-on-staff violence in 131 of the incidents and before the inmate-on-staff violence in 27 instances (Figure A-18).

Figure A-18. Use of force in reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC, 2017

Further analysis of these figures raises questions regarding whether the use of force was avoidable in many of the 158 events. For example, 34 (26%) of the 131 incidents where force was used after the reported inmate-on-staff violent act were in response to a threat. Further, the 27 events where use of force occurred before the reported inmate-on-staff violence may be indicative that correctional employees escalated an interaction with an inmate to the point of violence (see, for example: Textbox 1). This represents around 11% of all reported inmate-on-staff incidents, which may have been avoided with the use of verbal tactics or other de-escalation methods.

Inmates involved in incidents

The Independent Review Team was able to extract inmate information reported on IIRs that is not presently utilized for analysis by the ministry. Each IIR includes the Offender Tracking Information System (OTIS) unique identifying number of the inmate(s) involved in an incident. In the 252 total reported inmate-on-staff incidents in 2017 at TSDC, there were 145 unique individuals implicated, which means that some individuals were involved in multiple incidents (e.g., one inmate was involved in 11 reported incidents while in custody at TSDC in 2017). Table A-7 displays the breakdown of the inmate population involved in reported inmate-on-staff incidents of violence at TSDC in 2017.

| Age group | Number | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| <20 years | 5 | 3.4% | 3.4% |

| 20-29 years | 81 | 55.9% | 59.3% |

| 30-39 years | 34 | 23.4% | 82.8% |

| 40-49 years | 19 | 13.2% | 95.9% |

| 50+ years | 6 | 4.1% | 100% |

| Total | 145 | 100% | n/a |

Note: Age Group based on age on Dec. 31, 2017. Remand holding type includes federally sentenced inmates in Toronto South Detention Centre for remand purposes.

*One inmate who changed holding status (between remand and provincially sentenced) during his time in custody at Toronto South Detention Centre was excluded from analysis. All other inmates only had one holding status even over multiple inmate-on-staff incidents.

| Holding type | Number | Percent | Cumulative percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provincially Sentenced | 20 | 13.9% | 13.9% |

| Remand | 123 | 85.4% | 99.3% |

| Other | 1 | 0.7% | 100% |

| Total | 144* | 100% | n/a |

Some correctional employees suggested that individuals entering Ontario’s correctional facilities are increasingly more violent, and this trend explains the rise in reported inmate-on-staff assaults. The Interim Report highlighted that the majority of inmates in Ontario’s provincial correctional facilities were not in custody for a violent charge as their most serious offence (MSO). In TSDC in 2017, however, those in custody for a violent charge as their MSO made up a greater proportion of the average inmate population (approximately 50%) and of those inmates involved in reported inmate-on-staff incidents of violence (62%; Table A-8).

This data must be interpreted with caution. First, it is expected that at least over 400 inmates on a given day in TSDC

OTIS ranks “homicide and related”, “serious violent”, and “violent sexual” offences as the top three MSO categories. However, “assault and related” offences are ranked lower in MSO severity than other types of non-violent offences, such as importing drugs or fraud-related offences. As a result, an inmate in custody for a serious fraud charge and a minor assault charge would be counted in the non-violent MSO group, even with the presence of a violent charge for the current custody term.

| Most Serious Offence | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Non-violent | 55 | 37.9% |

| Violent | 90 | 62.1% |

| Total | 145 | 100% |

Note: MSO type is for any custody term at TSDC during 2017.

| Any active OTIS alert* in 2017 | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| No | 2 | 1.4% |

| Yes | 143 | 98.6% |

| Total | 145 | 100% |

*Active OTIS Alerts included alerts in any of the following seven selected categories: Mental Health; Substance Abuse; Security Threat Group; Management Risk; Intensive Supervision; Special Security; Dangerous Offender. Inmates could have more than one active OTIS alert at one time.

Table A-9 shows some categories of active alerts in OTIS associated with inmates involved in reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC in 2017. Inmates could have more than one active alert at any given time (e.g., Mental Health alert and Management Risk alert active simultaneously). The Independent Review Team reviewed the OTIS alerts and identified and included for analysis the following alert types as indicative of a possible risk for violent behaviour while in an institution: mental health (e.g., bizarre/abnormal behaviour); substance abuse (e.g., known substance abuse history); member of a security threat group (e.g., gang affiliation); management risk (e.g., disruptive/combative during admission, current or previous violent offence); intensive supervision (e.g., require more than usual community supervision by staff); special security (e.g., known to carry weapon, known to be assaultive to staff); and dangerous offender (e.g., long-term offender).

| Type of alert | Mental health | Substance abuse | Security threat group | Management risk | Intensive supervision | Special security | Dangerous offender |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active alert | 80 (55.2%) | 55 (37.9%) | 36 (24.8%) | 139 (95.9%) | 25 (17.2%) | 22 (15.2%) | 0 (0%) |

| No alert | 65 (44.8%) | 90 (62.1%) | 109 (75.2%) | 6 (4.1%) | 120 (82.8%) | 123 (84.8%) | 145 (100%) |

Alerts can be added to an inmate’s information in OTIS by most frontline correctional employees. Some alerts have automatic expiry dates following release from custody (e.g., suicide risk alert), but other alerts do not (e.g., gang affiliation). It is possible that some alerts remain active if a correctional employee does not remove an alert that is no longer relevant. The efficacy of these alerts is questionable when 85% of the average TSDC population had an active Management Risk alert in OTIS in 2017.

Correctional employees involved in incidents

To ensure transparency and accountability in daily operations, correctional officers are expected to carefully and thoroughly document events in a number of reports. Occurrence Reports, Use of Force Occurrence Reports, and Misconduct Reports require that the correctional employee involved in the incident (i.e., the person completing the report) be identified. The IIR requires identification of the person completing the report (i.e., the sergeant/manager), but does not explicitly require information pertaining to the correctional employee(s) involved in the incident beyond direct victims of reported assaults to be reported on the IIR. As a result, though inmate information can be manually extracted from IIRS and cross-referenced with OTIS for analysis of patterns of involvement, extracting reliable correctional employee information is currently impractical, tedious, and burdensome.

First, IIRs do not necessarily contain identifying information of the correctional employee(s) involved in a reported incident. For example, this information was not provided on IIRs for 112 (44%) of the 252 reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC in 2017. As a result, the Occurrence Report (OR) must be located and reviewed to determine which correctional employee(s) was involved or present during the incident. Even in doing so, there is presently no method by which frequency of employee involvement is tracked for trend analysis. Which staff are involved, in what types of incidents, involving which inmates, and how frequently are all important considerations for an incident of violence. If certain correctional employees are repeatedly involved in inmate-on-staff incidents, this could be a concern for management. A particular employee may be disproportionately exposed to situations of violence due to the assigned post, at heightened risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and require additional workplace and/or mental health supports and enhanced services through the Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) Program.

The Independent Review Team was able to assess Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) claims

As reported in the Interim Report, the Modernization Division of MCSCS is in the process of developing a digital system of reporting incidents. This system is currently undergoing user testing, with plans for a first iteration of the digital platform to be tested in four institutions in late-January 2019. Part of this new reporting platform will include a field for sergeants/managers completing the IIR to indicate the number of staff involved in an incident, and will prompt entry of the involved correctional employee(s) information by linkage to an active directory to avoid text field data entry errors. This new reporting process should allow for future analysis to be efficiently conducted utilizing correctional employee information.

A-III. Incident reporting practices

Inmate-on-staff incidents

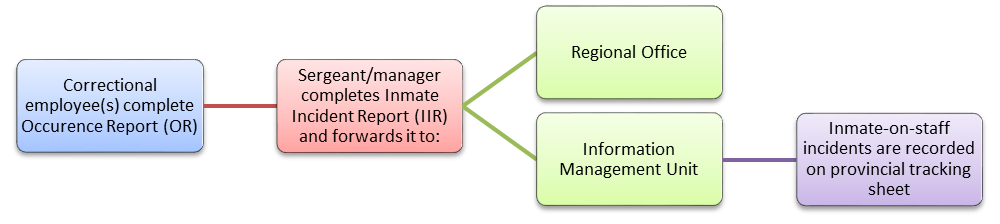

The Interim Report identified the basic reporting procedures following an incident involving an inmate in an Ontario provincial correctional institution. The Independent Review Team confirmed the following incident reporting procedures at TSDC. First, any involved correctional employee(s) will complete an Occurrence Report (OR). The OR is reviewed by the direct manager of the correctional employee submitting the OR. The Inmate Incident Report (IIR), containing a consolidated explanation of the incident, is completed by the sergeant or manager involved in an incident or a sergeant/manager who attends an incident, and is forwarded to the respective regional office and the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services’ (MCSCS) Information Management Unit (IMU).

Paperwork is extremely inefficient and growing more inefficient. Everything should be digitized and on OTIS, or a shared drive, including logbooks. […] It’s also hugely wasteful of officer time and taxpayer money […] From my perspective the Sgt are often hindered by excessively burdensome paperwork.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Figure A-19. MCSCS incident reporting paperwork process

The Independent Review Team randomly selected

Incompetent managers who are afraid of the inmates or too lazy to complete their paperwork makes staffs misconduct reports disappear and there is no consequence for the inmates misbehaviour which creates a viscious [sic] violence cycle of repeated threats, taunts, and physical assaults.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

The Superintendent’s Office at TSDC has a local list of all IIRs, Employee/Other Incident Reports (EOIRs, used for non-inmate related events), and ORs. The Independent Review Team reviewed this list for 2017 incidents at TSDC and identified 167 incidents that appeared to be reported inmate-on-staff violence but that could not be matched to the reported inmate-on-staff incidents recorded by the IMU and utilized by the ministry. The majority (139 of 167; 83%) of these incidents were identified on the TSDC local list as ORs, suggesting that they were never reported on IIRs by sergeants/managers. Again, the Independent Review Team randomly selected

The Independent Review Team also requested copies of documents pertaining to 12 randomly selected

Misconducts

Any inmate who breaches a written rule governing their conduct during incarceration is subject to disciplinary measures under the MCSCS Discipline and Misconduct Policy.

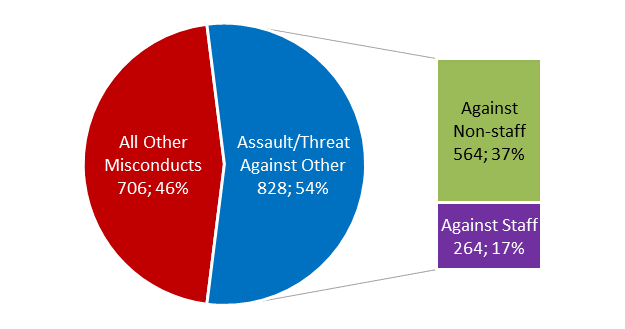

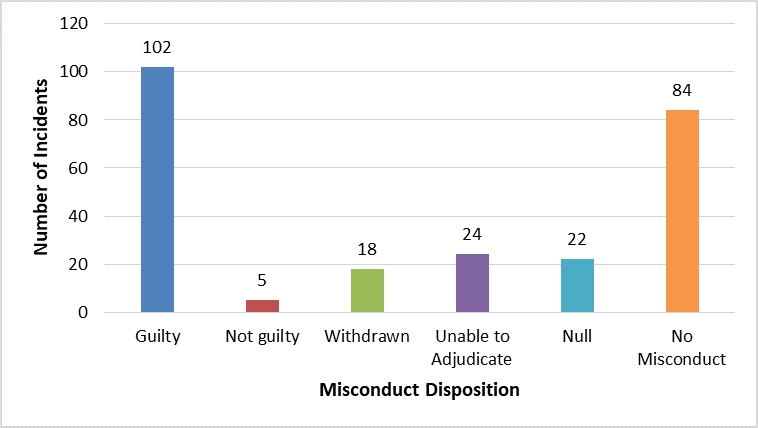

According to OTIS data, there were 1,534 formal misconducts at TSDC in 2017. The majority of these (54%) were violent, i.e., for occurrences of “commits/threatens assault on other” including staff (Figure A-20). The proportion of misconducts that were indicated as “against staff” (17%) was substantially greater than reported across the province as a whole in the Interim Report (6%).

Figure A-20. TSDC misconducts entered into OTIS, 2017

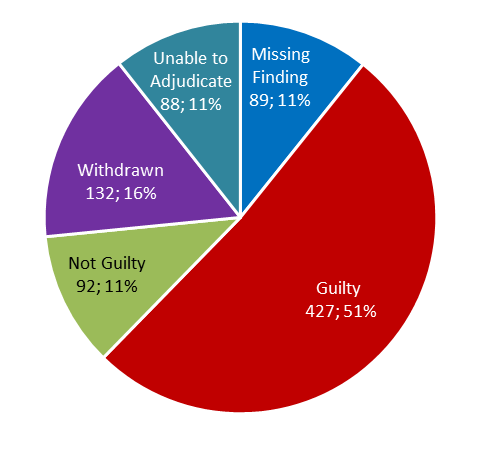

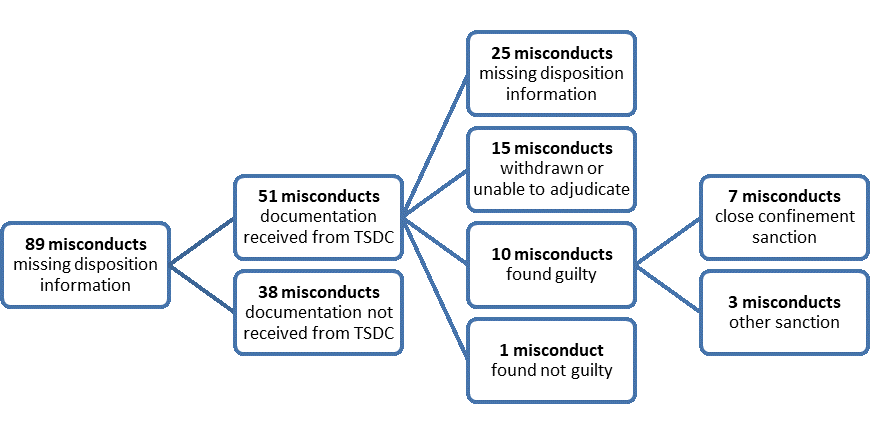

The Interim Report identified a large number of misconducts entered into OTIS that were missing information pertaining to the disposition of the misconduct. Similar to province-wide findings reported in the Interim Report, the majority of violent misconducts at TSDC in 2017 did result in findings of guilt, however, there were 89 misconducts at TSDC specifically for which no disposition information was available in OTIS (Figure A-21). Based only on OTIS information, it was unclear whether this was a data entry error at the OTIS-level, or whether there was no information available on paperwork held at the institution.

Figure A-21. TSDC violent misconducts by finding, 2017

The Independent Review Team requested copies of documentation relating to the 89 violent misconducts (“commits/threatens assault on other”) at TSDC in 2017 that were missing information in OTIS pertaining to the disposition of the misconduct; documentation was located and provided by TSDC for 51 (57%) of the misconducts (Figure A-22).

Figure A-22. Flow chart of TSDC misconducts with missing dispositions, 2017

An additional 15 (29%) of these misconducts were confirmed by documentation to have been withdrawn or unable to adjudicate. Reasons noted on the paperwork included that the inmate was no longer in the facility and/or was released at court, but in many instances there was no reason provided. One misconduct resulted in a finding of not guilty following a review of video footage in the institution.

This incomplete paperwork related to violent misconducts, and unreliable entry of information into OTIS, may exacerbate correctional employee frustrations in the seeming lack of disciplinary measures for inmates following violent behaviour. Further, this might partially explain the feedback received from frontline staff in the IROC Institutional Violence Survey that identified management as disinterested in holding inmates accountable or completing appropriate paperwork. As one officer noted, “the [sergeants] are often hindered by excessively burdensome paperwork”, and another wrote, “incompetent managers who are afraid of the inmates or too lazy to complete their paperwork makes staffs [sic] misconduct reports disappear and there is no consequence for the inmates misbehaviour”.

A-IV. Institutional culture

Institutional culture has the capacity to influence the daily operations of correctional work; it has been linked to conditions of confinement, institutional violence, and outcomes on release.

Employee safety concerns

I can honestly say that I fear for my own safety, and the safety of others everyday [sic] I come into work. What kind of a career is that?

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

In written responses to the Independent Review Team, some TSDC staff expressed concern regarding the safety of their working environment. This sentiment is captured in the feedback received from a correctional officer who wrote, “every day I come to work I have to wonder if me or my partner will end up as a 911 call”. Concern for safety was not unique to officers; for example, one staff member who was not a correctional officer remarked, “I worked for twenty two years at the Don Jail and never during that time did I feel my safety was jeopardized. Since starting at TSDC I have never felt secure. It’s a ticking time bomb”.

Institutional employee safety concerns were also evident in the IROC Institutional Violence Survey. Just under three quarters (71%)

The concerns reported by the staff at TSDC reflect the incomplete operationalization of the building itself. Toronto South Detention Centre is a technologically advanced facility with electronic security features incorporated into the building design, however, some of these tools for correctional employees, such as the Personal Alarm Location system (PAL),

There are definitely services offered to staff but who is proactively ensuring we are ok? For a lot of people they don’t feel comfortable opening up and asking for help. Also, there is a stigma that speaking to mental health professionals hinders chances for promotions in the future.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Concerns with the safety of the correctional working environment may, for some individuals, translate into adverse effects on mental health and mental stress. As one correctional officer divulged, “for a long time I thought I was the only staff member who had anxiety and issues with my job. I started opening up about it and I realized there is [sic] quite a few people with similar issues […] Toronto South is a highly stressful work environment with several moving parts and it is easy to get lost in all of it”. Unfortunately, many institutional employees expressed dissatisfaction with the resources available to assist in coping with the stresses and mental health issues that may result from working at TSDC. For example, only 11% of respondents felt as though the services offered through the Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM) Program were effective in coping with stress after a critical incident (see Appendix B, Table B-9). Similarly, only 15% of institutional employees indicated that the services provided by the Employee and Family Assistance Program (EFAP)

Staff-management relationships

Another theme that emerged in the IROC Institutional Violence Survey, as well as in feedback the Independent Review Team received from correctional employees, was the strained relationship between frontline staff and management at TSDC. This sentiment was reflected in the response of a correctional officer who advised, “the relationship between management and staff is absolutely toxic and it poisons the work environment”. Some frontline staff reported that “management does not seem to care what so ever [sic] regarding staff safety” while others indicated that “there is no trust amongst management and correctional officers” and that “management can not [sic] be trusted due to corruption and incompetence”.

Other survey respondents expressed dissatisfaction with management at TSDC, noting “the leadership… or lack there of [sic] …from the Chain of Command is pathetic”. This sentiment was echoed in the comments of another correctional officer with experience working at another institution who stated:

TSDC is a complete failure on all levels (upper management, middle management and staff)[.] Upper management does not have a clue or understanding what it is like to work the floors each and every single day… [and] is out of touch of whats [sic] going on, on the floors. Middle management (Sgts) are incompetent, not helpful at all and are in competition with each other. They throw staff ‘under the bus’ and are unsupportive. Most are inexperienced.

Several correctional officers indicated that there was “very little”, “no real”, or a total “lack of support” from various levels of management. Indeed, 60% of correctional officer respondents disclosed that they did not feel supported by frontline sergeants while 65% indicated that they did not feel supported in their work by their direct manager (see Appendix B, Table B-10). Most strikingly, 85% of correctional officer respondents felt unsupported in their work by TSDC’s senior administration.

There is such a divide between management and staff that neither side is working to restore relations, rather more head butting is occurring causing more issues. Problems are never resolved democratically. It feels as though management is fighting against staff, including refusing to use the body scanner for searches of known weapons. Management and staff should be working together to prevent staff assaults…

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Some frontline staff provided the Independent Review Team with further details regarding the ways in which they did not feel supported by management. One common complaint in this regard was that “management will often side with inmate instead of sworn correctional officers and often it is the correctional officers who are seen as in the wrong”. This sentiment was echoed in the comments of one frontline officer who indicated that, “when an inmate makes a statement that is false the management takes their side and the first they do is suspend a [correctional officer]. They do everything in their power to please these individuals who have committed haines [sic] crimes against other individuals. When these individuals are not being ‘pleased’ [officers] get in trouble”.

One possible consequence of this lack of support, as well as the “toxic” relationship between frontline staff and management more generally, was articulated by a relatively new officer who stated that TSDC “has so much potential, but staff feel as if they can’t enforce anything without getting in trouble or penalized. This causes staff to hate coming to work. It’s making me hate coming to work”. Similarly, another respondent suggested that TSDC has “the highest staff turnover rate and sick calls because it is such a toxic place to work” and that “management needs to be more concerned with staff issues rather than trying to appease inmates”. While they do not provide an indication of the reason(s) for lost time, ministry data indicate that, in 2017, the total average time lost (credit days)

Everyday [sic] I come to work with a high level of anxiety and am constantly looking for other employment where my skills and abilities are valued.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Some correctional officers advised that, in part due to the lack of support from management, “morale [was] very low for staff within [the] institution” and another cautioned that “adjustments MUST be made or else it will lead to staff having severe burnout […] [which, in turn] will lead to increased usage of sick time and turnover”. Although it does not conclusively establish low morale among institutional employees, it is telling that only slightly more than a third (35%

I feel that this institution is so poorly managed by administration and inexperienced seargents [sic] that the senior officers we have are trying to leave.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Review of written responses to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey makes it apparent that the ‘Us vs. Them’ mentality held by some staff regarding management contributes to cynicism, including suspicion of, and hostility towards, “outsiders”. For instance, one senior officer asserted, “any person from Senior Manager/Bureaucrat to Ombudsman/Politician… who does not work on the front lines for any length of time should not be dictating how the job should be done”. The officer further maintained that:

Politicians and Bureaucrats who told those who do not work in Corrections (Ombudsman-Handwringing do-gooders-Politicians or not…need to grow up. We do not need more ‘Youth Programs’ as most in this Jail CHOOSE to be criminals-they do not want to work for $14.00/hr…they know the Politicians will ensure far from harsh punishments/no, or little, consequences for wrong doing…maybe the Ministry Bosses/Bean Counters could start defending their employees instead of firing/suspending staff who do not ‘kiss the behinds’ of the inmates…cowards.

Punitive views

Another theme that emerged in the data collected by the Independent Review Team was a preoccupation with discipline and an expressed preference for punitive responses. This sentiment is captured in the written submission of one correctional officer who asserted,

the punishment that these criminals get is a joke. They need to be punished harder […] The way things are now they are playing in favour of the inmates and that is the reason why there are so many staff assaults, threats etc. because of lack of punishment for their actions. These individuals need to be punished for their actions and harder penalties […] The way corrections works now is a joke.

I don’t approve of the Mandela Report which you have sanctioned and implemented.

Sergeant, Toronto South Detention Centre

Similarly, another officer stressed that, “inmates should be punished for rude behaviour” while a recent hire submitted that “inmates have to [sic] much autonomy and freedom at the institutions […] There is no reason that inmates should be out of cells from 8am to 945pm. That’s too long and reduces the punitive nature of incarceration”. Finally, another frontline officer indicated that “Ontario Corrections is loosing [sic] its real purpose. The real picture is becoming close to a holiday resort, where inmates are ‘clients’ and officers are expected to behave like customer service! Inmates are given unnecessary luxuries like too many television channels (There is NO NEED for the Movie channel – they are NOT in jail to enjoy movies)”.

Bring back segregation. Jail should be a deterrent and this place is just a nice cushy hotel for very violent offenders who continue their criminal behavior behind these walls with little to no consequences.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

The punitive views of these institutional employees appear to be broadly embraced; indeed, 76% of respondents at TSDC felt that inmates should be under strict discipline (see Appendix B, Table B-11). The preoccupation with discipline and punishment was also apparent in the measures that correctional employees felt would most increase staff safety at TSDC. For instance, a veteran correctional officer with over 20 years’ experience working for the ministry proposed “LETHAL FORCE OPTIONS GET RID OF EXCESSIVE OVERSIGHT MAKE SEG PUNITIVE” as measures to enhance institutional safety, while a number of other respondents advocated for the reinstatement of “loss of all privileges” (LOAP). In addition, despite considerable empirical evidence challenging the effectiveness and utility of mandatory minimum sentences, 82%

Mandatory consecutive sentencing for threats and violence in institutions is an absolute necessity.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Staff-inmate relationships

The Independent Review Team was able to gain some preliminary insight into the way in which institutional employees perceived inmates and their relationships with these individuals. Over one-third (39%) of respondents reported that they had a good relationship with the individuals being housed at TSDC and 67% indicated that they made attempts to build trust with the inmate population (see Appendix B, Table B-11). Moreover, just under half (47%) of TSDC respondents felt that it was important to take an interest in those in custody and their problems. Around one-third (34%) of respondents felt that having a friendly relationship with inmates had the effect of undermining staff authority, and a considerable majority (80%) indicated that inmates take advantage of correctional staff if they are lenient.

A number of frontline staff expressed sentiments that revealed a more negative view regarding inmate care and their perceived role as correctional officers. For instance, a senior correctional officer wrote, “in your survey you mention my ‘relationship’ with inmates. I don’t have ‘relationships’ and I don’t like what that word implies. I am not here to make friends.” Another correctional officer, with over a decade of experience working for the ministry, asserted:

Its [sic] now a circus or [an] adult daycare centre. Who came up with the idea of calling an inmate a “CLIENT”? [...] I fully understand the concept of therapy, social work, mental health and trying to correct inmates to be better people when they get out…some can be helped, but a lot are born, grown and live a lifestyle that won’t change. So at face value we need to try and help those who are in jail with programs and treatment but there comes a point where the powers to be need to realize that inmates are inmates, and forcing us to call them clients infuriates officers […] Inmates can be well behaved inmates, but they are not clients.

A similar view was articulated by a relatively recent hire who, in expressing dissatisfaction with the inmate supervision model at TSDC, asserted, “Its [sic] ridiculous. We work with criminals and not with normal individuals”. Another frontline officer with less than three years’ experience stated, “inmates should have to deal with the repercussions of their own actions i.e. overdosing by contraband, or getting hurt while doing something against the rules”. This comment is particularly troubling given the officer’s apparent lack of compassion and an insensitivity to complex issues, such as addiction, that may be affecting those under the ministry’s care. Moreover, the sentiment is reminiscent of one recently expressed on social media by a correctional officer who wrote “who cares” in response to a news article reporting on the death of an inmate suspected to have overdosed.

A-V. Staff training and mentorship opportunities

As noted earlier (Table A-1), ministry data revealed that over half of senior administrators at TSDC had been in their current position for less than one year as of July 31, 2018, and over half of those employed as correctional officers had under two years of service. As many TSDC staff are relatively limited in their experience working at the institution or in a correctional environment, this highlights the need for training and mentorship programs to ensure that adequate services are being provided.

Correctional officers deployed to TSDC following successful completion of the Correctional Officer Training and Assessment (COTA) program

The Independent Review Team consulted with the institutional training department at TSDC in order to gain a thorough understanding of the breadth of on-site training and mentorship opportunities available to employees. While TSDC offers new employees some institution- specific training, there are significant gaps in what is provided. TSDC reported that the amount of time allocated to the topics covered varied (Table A-10).

With respect to inmate supervision, TSDC reported that training included an overview of the admission and classification process, the graduation of inmates through different levels of supervision, behaviour management tools, and the differences between direct and indirect supervision. At the end of each week, recruits take part in games that test their knowledge of TSDC’s standing orders, although performance on these “tests” is not graded. In addition, all new recruits spend a total of 120 hours (80 hours at TSDC, 40 hours at Toronto Intermittent Centre) in different areas of the facility job shadowing. This serves to expose recruits to some of the typical responsibilities of a correctional officer such as inmate meal service, lock up, cell inspection, logbook entries, and inmate management. TSDC reported that “every officer that the recruit shadows has more experience than the recruit” although, based on staff feedback, it is possible that the individuals shadowed may still be relatively new employees themselves.

Correctional officers who transfer to TSDC from another institution also spend a total of 120 hours job shadowing, although they receive less additional training than new recruits (e.g., two-day orientation, three days of training on direct supervision and SMCS, and an update on any additional training as required).

| TSDC local training topic | Time allocation | Training delivery method |

|---|---|---|

| TSDC standing orders | 5 days | Self-directed; game |

| Direct supervision | 3 days | Lecture; role play; scenarios |

| Security Monitoring & Control System (SMCS) | 3 days | Practical training |

| Defensive tactics | 1 day | Lecture; scenario; videos |

| Restraint chair | 4 hours | Lecture; practical |

| Radio/fleet net radio | 4 hours | Lecture; practical |

| Fire safety | 3 hours | Lecture; scenario; evaluation |

| Safe Smart |

45 minutes | Class video |

| Opioid | 35 minutes | Lecture |

The new staff are training each other.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

All new sergeants at TSDC receive 40 hours of in-class role-specific training that includes the following topics: admitting and discharging procedures, OTIS training, Workplace Discrimination and Harassment Prevention, Health and Safety supervisor responsibilities, fire safety policy, first aid, disability accommodation, water shut off procedures, and Safe Smart for managers. In-class training also includes one day of training on direct supervision for new sergeants, two to four hours (depending on class size) of in-class training on segregation reports and reviews, and two days of training on “Code Blue Packages”, which covers all types of Code Blue incidents, including use of force report writing, as well as incident reports and misconduct packages. New sergeants will also receive 120 hours of job shadowing (80 at TSDC and 40 at Toronto Intermittent Centre).

Sergeants who transfer to TSDC from another institution receive four days of direct supervision training, update any training where required, and similarly spend 120 hours job shadowing. TSDC indicated that sergeants are:

assigned to the areas they need to shadow… and report to the area and make their observations. A certain onus is on them to ask the questions after they [are] successfully selected. Some staff are willing to pass on information to others but not all. Every attempt is made to ensure that the person is paired up with a person who will assist in the training but not always a guarantee. One can’t force someone to train on the job… In short it’s a luck of the draw.

Despite the large number of senior administrators working at TSDC, they receive no formal local training. TSDC advised the Independent Review Team that, in one case, a recent informal effort for job shadowing was initiated.

Noticeably absent from the information on localized training curriculums received from TSDC is any reference to verbal de-escalation techniques, defusion of hostility, or negotiation and communication skills. The lack of training for correctional officers and sergeants is troubling,given the ministry’s emphasis on resolving incidents with verbal intervention and de-escalation and has been recognized as a significant gap in training by some employees. For instance, one correctional officer asserted “negotiation skills and techniques should be taught along side [sic] use of force and re-certification should also be required” while another survey respondent emphasized that “having communication skills” contributes most to staff safety at TSDC and urged that “appropriate communication skills [be taught] to staff and inmates”.

More broadly, the importance of positive inmate-staff interaction to the operational success of the institution was reflected in the IROC Institutional Violence Survey responses, with 25%

Currently, TSDC offers a peer mentorship program and each new recruit is assigned a mentor. There are approximately 35 mentors who have undergone a one-day training session where they were “taught to teach, coach and listen to the assigned mentee” and who are each paired with three to four mentees. The institution further advised that mentor positions are volunteer in nature and that the frequency with which mentors and mentees meet is determined by the pair, who may decide to meet as often or as infrequently as desired. While local training and mentorship opportunities are available year-round, TSDC advised that they “are usually more available in the fall, winter and spring months, as vacation time and [operational] needs are at a peak during the summer months”.

Proper training of all institutional employees is critical for the security of the institution and the safety of inmates, employees, and the public. This is particularly true for those working on the frontline. This view is reflected in the responses from institutional employees to the IROC Institutional Violence Survey. Notably, 34% of TSDC respondents

Correctional Officers at TSDC are the most unprofessional, sleazy, incompetent people I have ever worked with. They have zero regard to safety, security and personal boundaries with inmates. The ministry did mass hiring; they picked bottom of the dumpster. I’ve only come across a few good, hardworking [correctional officers] since being at TSDC. The rest are garbage.

Some respondents offered suggestions geared towards improving the recruitment and training process. For instance, a correctional officer suggested that the recruiting process for Corrections should be changed and it be made harder to get hired, and easier to by removed from COTA if the training staff deems you unsuitable for the job. [Fixed-term] officers first year should be on probation and if the officer is deemed unsatisfactory, the contract is not renewed.

The officer also recommended that there “be a proper training program at OCSC for sergeant and staff sergeants that teaches them how to manage personnel, leadership skills, administrative (paperwork) skills, testing etc. If the Sgt or S/Sgt candidate is deem[ed] unsuitable, they should be removed from training and returned to their institution”.

Equally troubling was the general discontent among TSDC employees with the local training, mentorship programs, and opportunities for professional development provided at the institution. For instance, around 58% and 69% of TSDC respondents

…most of all the newer recruits need proper mentors when starting their career.

Sergeant, Toronto South Detention Centre

This dissatisfaction with local training and mentorship opportunities was glaringly apparent in the feedback the Independent Review Team received from correctional employees. As one correctional officer stated, “I think many Sgts know more inmate names than their staff. That should tell you everything you need to know about how much mentorship is going on”. Other employees echoed this sentiment, including a sergeant with over 20 years of experience working for MCSCS who noted, “these days staff are being hired by the dozens, unfortunately are not getting the one on one assistance from the more experienced staff. Therefore the new staff are training the newer staff”. Similarly, one correctional officer voiced concern with the mentorship program at TSDC and advised that “many of the newer officers are job shadowing officers with a year or less in. The mentorship program needs to work more effectively”. The consequences of a lack of appropriate mentorship opportunities is illustrated in the sentiments of a correctional officer who, prior to being stationed at TSDC, had experience working at two other institutions and advised the Independent Review Team that “training is poor, support is minimal from management, upper management and many other lateral levels. There are many good officers and managers in the building, however, this is the exception. The ability to mentor newer, inexperienced officers is not available which leads to misinterpretation of the policies and best practices”. Similarly, an experienced sergeant advised that, due to a lack of mentorship, “much is lost in why we do things a certain way. New staff are fearful because they haven’t learned how to build a respectful relationship with the clients. Mentorship is important, and communication is essential”.

Staff are not trained enough on how to talk to inmates.

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

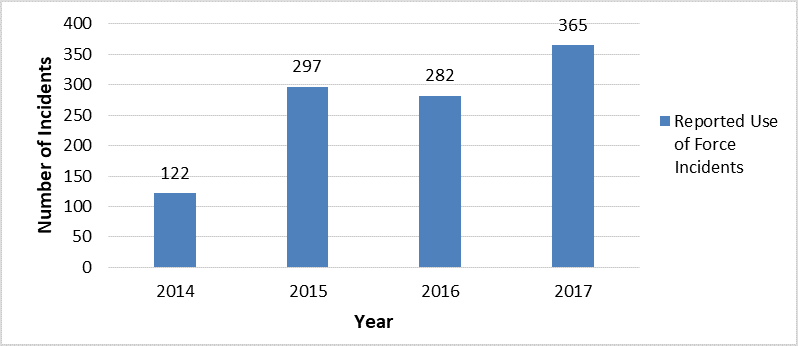

Appropriate communications training, both formally through COTA and informally through local mentorship and job shadowing, has direct implications on operational outcomes including interactions with inmates. The ability to defuse a situation before using physical force is crucial to mitigating institutional violence. When the Independent Review Team examined ministry data, it was found that use of force incidents were essentially a daily occurrence at TSDC in 2017 (Figure A-23), increased from previous years.

Figure A-23. Reported use of force incidents, TSDC

As noted earlier (see Figure A-18), 27 reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC in 2017 involved use of force prior to the reported inmate-on-staff violence. In other words, the reported inmate-on-staff violence occurred after a correctional employee initiated a use of force, i.e., physical contact, on an inmate. In particular, this represents over one-tenth (11%) of all reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC in 2017, and over one-fifth of reported physical assaults (11 of 52; 21%) at the institution. This signals an opportunity for better correctional employee training in de-escalation techniques to avoid such instances where staff actions may have escalated violent interaction with an inmate (see, for example: Textbox 1).

A-VI. Operational practices

Inmate classification

The direct supervision model does not work without proper classification of inmates…

Correctional officer, Toronto South Detention Centre

Proper risk screening and classification of inmates is essential to the security of correctional institutions and to the safety of those living and working within them.

As the first direct supervision facility in Ontario, it was imperative that TSDC develop an internal classification system to determine appropriate housing unit placement (e.g., direct supervision vs. indirect supervision). Currently, TSDC relies upon the Internal Placement Report (IPR) to classify inmates and determine their institutional placement. The TSDC IPR is divided into eight sections that are completed by various institutional employees, including booking officers, health care staff, intake unit officers, and classification officers before the placement decision is ultimately authorized by an intake unit sergeant. The IPR scores inmates on a number of behavioural measures (e.g., whether the inmate follows direction, is cooperative, has positive interactions with authority and other inmates), past and current violent offences, previous dispositions, behaviour management concerns (e.g., previous institutional misconducts, assaults on staff, police, or inmates), and considers any accommodation issues and programming needs.

This tool was developed locally by the TSDC Classification Working Group

Typically, inmates are classified within days of arriving at the facility, although the institution advised the Independent Review Team that “there is not a set timeframe” and the classification process can be lengthy and may be influenced by lockdowns, institutional staffing, safety concerns, as well as an inmate’s court date(s) and other relevant classification factors (such as gang affiliations, non-associations, and ‘keep separates’

Although some staff have expressed concern with the IPR and operational processes used to assess and classify inmates, the Independent Review Team found that fewer incidents of reported inmate-on-staff violence occurred on direct supervision units at TSDC. While about 43% of inmate snapshot of the TSDC 2017 inmate population was housed on a general population direct supervision unit,

Multi-level housing units

It is imperative that inmates be appropriately housed based on their security risk and programming or treatment needs identified as a result of individualized classification. Despite recent efforts by the ministry (see Section 3. Operational Practices and Textbox 6) to standardize various housing units throughout the province,

Several correctional employees indicated that the availability and proper use of alternative housing was integral to the success of institutional operations at TSDC. For example, 22%

The present examination of TSDC revealed that the majority (32) of the inmate living units at TSDC are designed to accommodate the direct supervision inmate management model while the remaining units (11) are indirect supervision units. The units are further divided into several specialty units including intake, segregation, special handling, behavioural management, mental health assessment, special needs, medical, and infirmary.

Special needs unit

Inmates housed in a direct supervision Special Needs Unit (SNU) at TSDC have a history and/or confirmed diagnosis of a severe and/or persistent mental health illness or condition (e.g., schizophrenia, affective disorder, borderline personality disorder, dementia); a developmental disability; a significant physical disability (e.g., restricted mobility, deaf, blind, those requiring palliative care); and/or, Fetal Alcohol Syndrome or Fetal Alcohol Effects.

Admission to the SNU is based on clinical assessment and both of the following two criteria must be met in order for an inmate to be admitted into the SNU at TSDC:

- There is a previous diagnosis of a mental health disorder and/or it is suspected (based on an inmate’s current presentation) that they are currently experiencing:

- major mental disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, delusional disorder)

- anxiety or mood disorder

- trauma related disorder (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder)

- personality disorder

- dual diagnosis

- severe cognitive deficiencies

- sensory impairment

- The inmate is currently not stable to be considered for a regular unit at Toronto South Detention Centre and needs additional support to stabilize, or the inmate was previously on a regular unit where they were not able to function due to their condition.

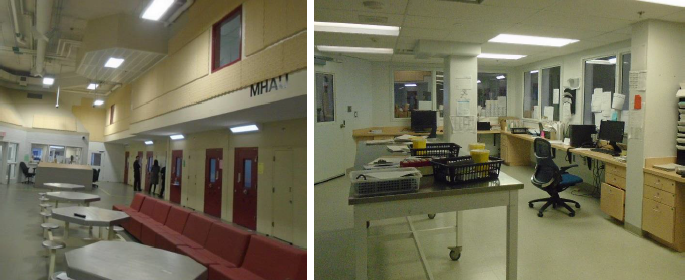

Mental health assessment unit

TSDC operates a direct supervision Mental Health Assessment Unit (MHAU) which houses inmates with identified acute mental health issues. Admission and discharge are completed by clinicians who must identify the following two criteria:

- The inmate is experiencing acute symptoms of specific major mental disorders;

footnote 234 and, - The inmate is currently in crisis and is not stable to be considered for a regular unit or SNU at TSDC and needs additional support to stabilize, or the inmate was previously on a regular unit or SNU where they were not able to function due to their condition.

TSDC indicated that an inmate’s placement in either the SNU or MHAU are reviewed regularly at weekly case management meetings to discuss the inmate’s progress and determine if the case management team believes that the individual can be moved to a regular unit. This weekly inter-disciplinary review and assessment is encouraging as it is a clear demonstration of how individualized case management can be operationalized and made available to both remand and sentenced individuals.

Figure A-24. Mental Health Assessment Unit, TSDC

Behavioural Management Unit and Special Handling Unit

TSDC also operates Behavioural Management Units (BMUs) and Special Handling Units (SHUs) on indirect supervision units. Based on information provided to the Independent Review Team, admission to these specialty units is, to some extent, based on institutional behaviour. Inmates who score high on the IPR are classified to the BMU or SHU for a minimum of 15 days, which serves as an assessment period, and may then be reclassified based on behaviour during that time period. Inmates who disagree with their classification may submit a written inmate statement form noting any concerns and/or submit a request to speak with a classification officer or sergeant.

Figure A-25. Behavioural Management Unit, TSDC

Figure A-26. Special Handling Unit, TSDC

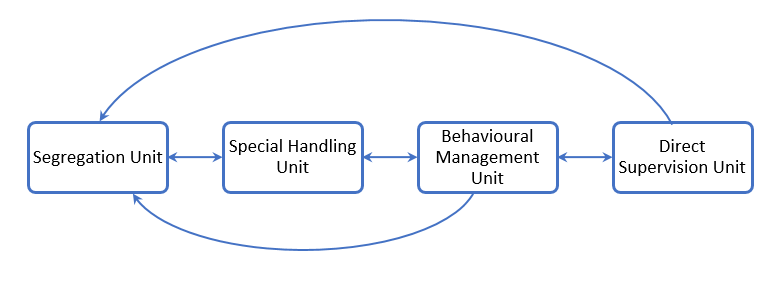

In addition, following negative behaviour in the institution, inmates may be moved to the BMU or SHU even if not initially classified on the IPR to be housed on these units. Senior administrators at TSDC identify that the current ‘ideal’ model of movement between housing units is as outlined in Figure A-27.

Figure A-27. TSDC ‘ideal’ inmate movement between select housing units

As is evident in the figure above, movement between units can flow both ways. This reflects recent changes in institutional operations in late spring 2018 following the re-opening of the facility’s two BMUs, intended to function as an intermediate layer between direct supervision units and SHUs. Again, the creation of these BMUs is not consistent with current ministry policy regarding the placement of special management inmates.

Under this model, TSDC has indicated that the most problematic inmates and those who commit the most serious misconducts are housed in a Segregation Unit or SHU, while the BMU houses inmates who have committed minor misconducts or have received multiple sanctions on direct supervision units. TSDC reports that all

Operationalizing TSDC’s housing units

One major distinction between housing units at TSDC is the number of unlock hours inmates receive per day. Table A-11 outlines the daily hours of unlock in effect as of March 9, 2017, after a memorandum was issued to all staff following senior administrators at TSDC becoming aware of inconsistencies in unit unlock and lockup times.

| Unit | Inmate Supervision Type | Hours of unlock per day | Scheduled unlock hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct supervision (e.g., general population, protective custody, special needs) | Direct | 13 hours | 0800-1300, 1400-2200 hours |

| Intake | Direct or indirect | 7 hours | 0900-1130, 1330-1600, 1700-1900 hours |

| Mental Health Assessment (MHAU) | Direct | Varies | Cell to cell unlock times vary throughout the day based on compatibility and behaviour |

| Overflow | Direct or indirect | 2 hours (minimum) | Cell to cell unlock times vary throughout the day due to a mixing of populations (48hr housing max) |

| Behavioural Management (BMU) | Indirect | 4.5 hours (divided by three groups totaling 1.5 hours per inmate) | Rotating unlock times between 3 groups of inmates from 1000-1130, 1330-1500 and 1500-1630 hours |

| Special Handling (SHU) | Indirect | 6.5 hours | 1000-1200, 1330-1630, 1730-1900 hours |

| Segregation | Indirect | 30 minutes (includes yard and shower programs) | Cell to cell unlock times vary throughout the day |

TSDC further advised the Independent Review Team that, between March 2017 and June 2018, hours of unlock in BMUs and SHUs have changed (Table A-12).

| Unit | Hours of unlock per day (June 2017 – June 2018) |

Hours of unlock per day (June 2018 - present) |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioural Management (BMU) | 2 hours (minimum)* | 5 hours |

| Special Handling (SHU) | 2 hours (minimum) | 3 hours |

*Note: TSDC reports that the BMU was closed for approximately 6-8 months due to construction and re-opened in late spring 2018.

The Independent Review Team canvassed TSDC to determine, for some of the specialized care units, how the current hours of unlock were established and why they were altered from the original design intent. TSDC advised that the implementation of the BMU and the current changes to their operating procedures for the SHU were based on the operating model in place at the South West Detention Centre. While efforts were made to encourage progressive incentives for positive behaviour by altering unit unlock hours, little, if any, research was undertaken to support the operational policies for these specialized care units.

Evidence-based practices

It is difficult to estimate an average count of inmates in TSDC by unit type, due to a number of factors, including closing of units due to construction, transfers of inmates, and frequent changes in use or type of unit during 2017. Although the IIR indicated in which unit the reported incident took place, it was not possible to determine the inmate count of the specified unit on the date of the reported incident. However, using an approximation

| Unit type | Number | Percent of all reported incidents |

|---|---|---|

| Admitting and discharge area | 34 | 13.5% |

| Segregation unit | 71 | 28.2% |

| Special handling unit | 30 | 11.9% |

| Behavioural management unit | 14 | 5.6% |

| Mental health assessment unit | 29 | 11.5% |

| General population direct supervision unit | 26 | 10.3% |

Despite the low number of inmates housed in specialized units, disproportionately large numbers of reported inmate-on-staff incidents occurred in these units (e.g., Segregation Unit, SHU, BMU, MHAU). For example, roughly 3% of the inmate population at TSDC was housed in a Segregation Unit, where inmates received a maximum of 30 minutes of unlock per day. Yet, Segregation Units accounted for the largest number of reported inmate-on-staff incidents (71; 28%) in 2017 at TSDC.

The second largest proportion of reported incidents took place in the Admitting and Discharge Area (34; 14%). As these incidents may involve inmates being admitted to TSDC for the first time or in transit to/from court or between institutions, it was not possible to assess the housing classifications assigned to these inmates.

Similarly, only about 11% of the TSDC inmate population was housed in the SHU or BMU, where they received a maximum of two hours

Furthermore, about 3% of the population at TSDC was housed in the MHAU which is dedicated for individuals with acute mental disorders or symptoms that cannot be managed on a regular or special needs unit. Hours of unlock each day vary depending on the inmates, due to their individualized behavioural concerns. A large number of reported incidents took place in the MHAU (29; 12%).

Although about 43% of the inmate population at TSDC was housed in a direct supervision unit,

Taking inmate population into account, the proportion of reported inmate-on-staff incidents at TSDC in 2017 appeared to increase as conditions of confinement became more restrictive. As previously noted, inmates in specialized units may exhibit the highest needs and therefore benefit the most from programming, treatment, and correctional rehabilitation interventions. Further analysis should be undertaken to understand the resources, programs, and meaningful activities offered to inmates by unit and their corresponding impact on institutional violence.

Figure A-28. Disposition of misconducts matched to TSDC reported inmate-on-staff incidents, 2017

Out of the 252 reported inmate-on-staff incidents, there were 255 potential situations where a formal misconduct could have resulted; three incidents involved more than one inmate. Of these, 171 (67%) could be matched with a misconduct in OTIS, and 84 (33%) could not. Those that could not be matched may be a result of missing information (i.e., not properly entered into OTIS), a different date than the incident date being entered into OTIS, or that a correctional employee resolved the situation informally and decided not to pursue a formal misconduct.

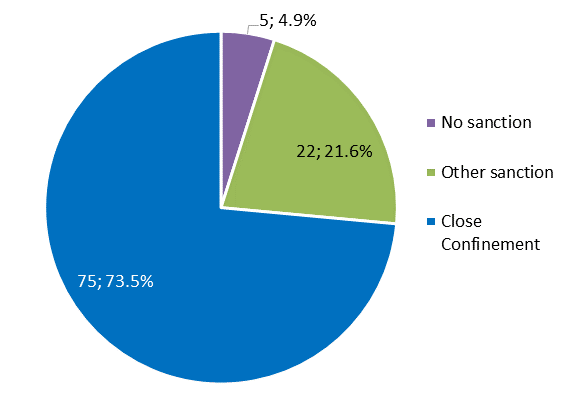

Of the 102 misconducts that resulted in guilty findings, over 95% resulted in sanctions; almost three-quarters (75; 74%) resulted in the use of close confinement (i.e., disciplinary segregation), and a further 22 (22%) resulted in any other sanction (Figure A-29).

Figure A-29. Guilty finding sanctions for misconducts for TSDC reported inmate-on-staff incidents, 2017